Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAIEE Africa Research Journal

On-line version ISSN 1991-1696

Print version ISSN 0038-2221

SAIEE ARJ vol.108 n.2 Observatory, Johannesburg Jun. 2017

Personal information and regulatory requirements for direct marketing: a South African insurance industry experiment

A. da VeigaI; P. SwartzII

IUniversity of South Africa (Unisa), School of Computing, College of Science, Engineering and Technology, South Africa E-mail: dveiga@unisa.ac.za

IIUniversity of South Africa (Unisa), School of Computing, College of Science, Engineering and Technology, South Africa E-mail: paulus.swartz@absa.co.za

ABSTRACT

The processing of personal information by companies should be in line with ethical and regulatory requirements. Whilst respecting the right to privacy, personal information can be used to create value in the economy as well as on an individual level by tailoring and targeting services. However, personal information should not be processed under false pretences for the purposes of direct marketing. Data protection regulations, such as the Protection of Personal Information Act (PoPI) 2013, regulate the processing of personal information. Accordingly, companies domiciled in South Africa have to comply with the conditions of PoPI and must process personal information in line with the agreed purpose. PoPI will have an impact on direct marketing and certain conditions will apply to protect individuals' personal information, as well as how and by whom it is used.

This research sets out to investigate whether companies in the insurance industry are complying with the direct marketing conditions of PoPI pertaining to opt in and opt out preferences as well as a few other aspects. An experiment was conducted in South Africa whereby two new cellphone numbers and six new e-mail addresses were deposited in the economy by requesting online insurance quotes from twenty different insurance companies. For half of the online insurance quotes the researchers elected to opt in for direct marketing and for the other half to opt out. Any communication received on the cellphone numbers or e-mail addresses was recorded and analysed to establish if the preferences expressed were being complied with.

The results indicate that data was shared and possibly leaked; this finding was based on the number of contacts received from companies that were not part of the sample. It was found that opt out preferences for direct marketing were not honoured by some companies. Other aspects, such as the availability of the option to opt in or opt out for direct marketing when depositing personal information on websites, secure processing of personal information and the use of privacy disclaimers, were also found to be lacking in some instances.

This indicates that the insurance industry in South Africa might not yet be fully compliant with the requirements for direct marking, as required by PoPI and the Consumer Protection Act (CPA). The results of the research can be used to improve direct marketing interactions with consumers, helping to ensure not only compliance with PoPI, but also the maintenance of a trusting relationship by respecting privacy.

Keywords: Protection of Personal Information Act; PoPI; direct marketing; opt in; opt out; personal information; privacy.

1. INTRODUCTION

"Everyone has the right to privacy", is enshrined in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996) [17, 59] and similar rights are regulated by means of privacy and data protection regulations in over a hundred countries [11]. Privacy is the right of the individual to be free from secret observation and to determine with whom, how and whether or not to share personal information [1]. For most people "privacy" is a meaningful and valuable "commodity", but the term has different meanings in different contexts [2]. Privacy is an essential component of individual freedom, civil liberty, autonomy and dignity [3, 4]. The right to privacy is the right to an individual's autonomy and personality, which is an individual's general right [3].

Consumers' privacy should be respected and balanced with societal and regulatory requirements and the value provided by companies when consumers share their personal information [58]. In terms of privacy, individuals have a reasonable expectation that companies such as cellphone and internet providers, banks, government institutions, medical practitioners, and retail and insurance organisations will secure their personal information [3]. However, the right to privacy in the digital world is under attack as tracking surveillance is increasing and individuals' personal records are becoming more vulnerable while being stored digitally [3]. Contextual integrity is destroyed when digital information is sold or reused; even if users give their consent, they are not always aware of the purpose for which their information will later be used [5]. Moreover, the mismanagement of personal information when processing, storing, using, collecting or exchanging such information could violate human rights. It could also result in people losing trust in companies, especially if the information is not secured and processed in accordance with regulatory requirements and what the individual consented to [6]. While consumer data can be misused, it can also be used to the benefit of the individual and the future knowledge economy by extracting value from it. Better use of data through data value chains could benefit various industries, improve research and innovation and increase productivity [28]. Companies could use personal information to add value by directing specific services to consumers based on their profile and identified need, thereby enabling better strategic and operational decisions [44, 51].

Privacy and data protection legislation provides that the collection of personal information should be lawful and fair and that it should not be carried out under false pretences. This means that personal information collected from consumers for a specific service or product cannot be used for telemarketing or advertising without the consumer's permission [52]. This condition imposed on the processing of personal information is encapsulated in international frameworks such as the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Privacy Framework [52], the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [53], regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation of Europe [14] and international standards such as the British Standard BS 10012:2009, Data protection - Specification for a personal information management system [54] and ISO IEC 29100.2 Information technology - Security techniques - Privacy framework [55].

In South Africa, the Protection of Personal Information Act (PoPI) (2013) was promulgated in November 2013 [7, 8, 17]. This Act regulates the processing of personal information by public and private organisations domiciled in South Africa. PoPI includes a condition relating to unsolicited marketing, namely, that consent is required in certain circumstances when existing or new customers are contacted. Companies must comply with the conditions of PoPI and may contact individuals in line with those conditions. Similarly, the Consumer Protection Act (CPA) of 2010 [23] gives consumers the right to restrict unwanted direct marketing targeted at them through media such as Short Message Service (SMS), email or cellphone calls.

This research paper discusses research carried out to determine whether consumers' opt in and opt out preferences are honoured in the flow of personal information in the insurance industry, as mandated by privacy legislation and, specifically, PoPI. The research results can provide the insurance industry with insight into possible gaps in compliance with PoPI when processing personal information of their customers or potential customers for marketing purposes. This research project forms part of a larger research project undertaken by honours students from the School of Computing at the University of South Africa (Unisa) as part of a BSc or BCom Honours degree [51].

The remainder of the research paper is structured as follows: section 2 gives an overview of international privacy legislation and is followed by an overview of PoPI. Section 3 discusses direct marketing with the possible implications of PoPI in section 4. The insurance industry is discussed in section 5. Section 6 presents the research questions followed by the research methodology in section 7 and the results of the experiment in section 8. A discussion of the findings, recommendations and limitations is presented in section 9, followed by the conclusion in section 10.

2. AN OVERVIEW OF PRIVACY LEGISLATION

2.1. International privacy legislation

The objective of privacy legislation is to enable the individual to (i) manage or control the flow of personal information and (ii) to give the individual autonomous space [12]. The growth of modern computing has resulted in data protection laws being implemented in many countries. In 1974 the United States of America drafted its privacy legislation. Germany followed in 1977 and France in 1978 [12]. Data protection laws have been adopted by over 100 countries [8, 11, 47]. India, as well as a number of countries in Africa and South America, is currently in the process of enacting privacy laws [47].

In the United States, the processing of personal information is regulated through a sectorial approach whereby privacy laws address a specific industry. Such laws include the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act (FACTA) of 2003 [56], which focuses on the financial industry, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 [57], which focuses on health data. Studies indicate that Americans are mainly concerned about solicitation, government monitoring and the commercial use of personal data, whereas European citizens are found to be concerned about the collection and sharing of their personal information [46, 58].

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [14], which replaced the European Union's (EU) Data Directive 95/48/EC [12, 13], addresses new technological developments and harmonises national data protection laws across the European Union member states [15]. In addition, the EU-US Privacy Shield was implemented in 2016 to regulate the processing and flow of EU citizen data by US companies [45].

Most privacy or data protection laws are based on the Code of Fair Information Practices (FIP) [60], the OECD Privacy Guidelines [53] and APEC Privacy Principles [52]. PoPI in South Africa mirrors these international privacy principles.

2.2. Protection of Personal Information Act (PoPI), 2013

The purpose of PoPI is to provide a constitutional right to privacy by protecting the individual's personal information when this is processed by a responsible party. In this context, the individual is referred to as a "data subject"; this is the "person to whom personal information relates" and who is an identifiable, living, natural or juristic person [17]. The responsible party is the "public or private body or any other person which, alone or in conjunction with others, determines the purpose of and means for processing personal information" [17].

"Personal information" is information relating to the data subject, such as biographical information (e.g. race, gender, marital status, disability or religion), education, medical or financial information, e-mail and physical addresses, biometric information, and even information about personal opinions and views, including correspondence [17].

PoPI regulates the manner in which personal information may be processed, in line with international standards and established conditions, and according to the prescription of the minimum threshold requirements for the lawful processing of personal information. The term "processing" means any action that is performed on the information throughout its life cycle, including "the collection, receipt, recording, organisation, collation, storage, updating or modification, retrieval, alteration, consultation or use; or dissemination by means of transmission, distribution or making available in any other form; or merging, linking, as well as restriction, degradation, erasure or destruction of information" [27].

PoPI also provides for the rights of data subjects, and the remedies available to them, to protect their personal information from processing that is not in accordance with the Act. PoPI provides for the establishment of an information regulatory body with certain duties and powers in line with the conditions of PoPI and the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA), 2000 [18]. The chairperson and members of the Information Regulator have been appointed as of December 2016 [19].

South African citizens' personal information is also processed outside South Africa by multinational organisations and through the internet, which renders the information vulnerable [6]. The sensitivity of personal information changes as it flows through the economy, therefore the security and privacy requirements are dynamic [16] and should at all times be processed in line with the regulatory requirements of the relevant jurisdictions.

PoPI has a significant impact on an organisation's policies, employees, information technology infrastructure, third-party service providers and procedures if the organisation aims to comply with the provisions of the Act [20]. Accordingly, the Act affects responsible parties that collect, process and store the personal information of customers, employees and third parties as part of their operational activities [7].

3. USE OF PERSONAL INFORMATION FOR MARKETING PURPOSES

In direct marketing, the marketer communicates directly with a customer or client in the hope that the customer will respond positively to the marketer's request [29]. Any type of electronic communication - such as an SMS to a cellphone, e-mails, mobile device application advertising and social media marketing - serves as a tool used by the marketer to advertise services or products. In a study conducted by Microsoft it was found that consumers are willing to share their personal information if they are explicitly asked for permission and if there is clear benefit in return [49]. According to the parliamentary text of the GDPR, consent must be explicit, indicate affirmative agreement from the data subject, and is valid as long as the personal information is processed for the purpose it has been collected for. Ethical considerations emanate when personal information, which has been collected for a specific purpose to which the consumer agreed, is used for another purpose without consent [48].

According to section 69 of PoPI, the customer must grant permission for the processing of personal information and must also have the option to cease any communications [17]. The consent option for processing personal information is referred to as "opt in", and the rejection of future communications from the marketer is referred to as the "opt out" option.

Consumers are sometimes misled about their choice to opt in or opt out on companies' websites or application forms. For example, the default setting on most websites is set to opt out, or the questions that are asked ("Please send me newsletters" or "Please do not send me newsletters") are trivial and might influence consumer decisions [31]. Because of inattention, and cognitive and physical laziness, default answers are given. If the opt in option is given it is often ticked by default if marketers need the consumers to opt in for the processing of personal information [32]. As such, compliance with PoPI could impact negatively on companies' freedom to use marketing and communication initiatives.

Section 11 of the CPA [23] stipulates that every person has the right to privacy and to refuse unwanted SMS's cellphone calls, letter or "spam" e-mails. This gives consumers the right to "opt out" of direct marketing communications, where after companies or suppliers may not continue to contact the consumer. In support of this, the CPA provides for the establishment of a "do-not-contact registry" whereby consumers can register to opt out of all unsolicited marketing. This has however, not been implemented as yet. The Direct Marketing Association of South Africa (DMA) currently maintains a register of consumers who do not want to be contacted for direct marketing, but this will only apply to opt out of direct marketing for organisations that are registered with the DMA [62]. This includes approximately 373 companies including the major banks in South Africa, as listed on the DMA website.

The CPA has a consumer protection focus and does not focus on the security of personal information or the lawful requirements for usage of personal information. PoPI addresses these limitations and also focuses on unsolicited marketing, but from an opt in and opt out perspective. According to section 69 of PoPI, the processing of personal information for the purpose of direct marketing is prohibited, unless the marketer has the consent of the data subject, the data subject is a customer of the responsible party, the responsible party has the customer's contact details and they market similar products or services to the data subject. Responsible parties may contact new customers only once for direct marketing, whereafter the consumer must opt-in to receive further marketing communication. In addition PoPI requires responsible parties to inform data subjects of the source from which they collected their personal information in support of openness and transparency (PoPI s18(1), [17]).

4. PRACTICAL IMPICATIONS OF POPI

PoPI will have a positive impact from an organisational and data subject perspective as discussed below.

Preventive measures: Responsible parties who collect personal information must be accountable and transparent, and should safeguard personal information according to condition 7 of PoPI [34]. According to De Bruyn [7], companies are now implementing proactive technical and organisational measures in the hope that these will prevent the leaking of personal information. These measures should ensure that companies' databases are secure in order to prevent data leakage and to protect their investments.

Transparency: Another advantage, according to De Bruyn [7], is that companies will be more transparent in terms of how, what and where personal information is stored within the company. Companies must notify data subjects when personal information is processed, (s 18, [17]), and data subjects have the right to opt in or out, free of charge, in respect of receiving marketing communication (s 69, [17]). Consent must be given before personal information is shared with third parties for marketing purpose (ss 11 and 20, [17]), therefore data subjects should not under normal circumstances receive unsolicited SMS's, phone calls or e-mails [7]. All businesses or parties responsible for big data and the analysis of an individual's habits, purchase behaviours or health status must be transparent in their use of the personal information, ultimately protecting the right of the individual while abiding by ethical principles [21].

Individuals ' rights: If data are inaccurate, misleading, excessive or incomplete, or if data have been obtained unlawfully, data subjects can rightfully request an update, deletion or correction of their personal information according to section 16 of PoPI [17, 22]. Wilson [21] argues that the laws protecting the privacy of personal data give individuals the rights to all their data, irrespective of the source. PoPI also enables individuals to institute civil proceedings under certain circumstances if there has been interference with the protection of their personal information (ss 5 and 99, [17]).

Whilst there are benefits attached to protecting the privacy of consumers, many companies believe that PoPI will have a negative effect on them as explained below.

Marketing costs: The CPA [23] only allows for an opt out mechanism. Section 11(5) of the Act states that if a consumer opts out of receiving direct marketing, they cannot be charged a fee for doing so. PoPI stipulates that affirmative consent is required, which means that individuals have to opt in to receive direct marketing messages (s 69, [17]). PoPI also requires that the customer be given reasonable time to object, at no cost to the data subject, which means that the business is responsible for all costs if the customer opts out at a later stage [24]. Companies must update their IT systems to flag the option to opt in or opt out of direct marketing (s 11, [17]). Company processes for responsible parties and third parties must also be updated according to section 13 of PoPI, with the provision that personal information can be shared only if the purpose is specific, the quality of information is assured (s 16, [17]) and the information is safeguarded (s 19, [17]). This has an impact on IT system designs, administration and governance processes, and contractual processes with third parties.

Operational costs to companies: Critics have warned that the PoPI regulatory scheme will discourage economic activity and place undue burdens on businesses, because many businesses will have to make supplementary investments in information technology systems or use third-party vendors in order to comply with PoPI [25].

Compliance time frames: To be compliant within one year is impracticable, as shown by a survey conducted in South African businesses in 2013, and it could take up to three years to become fully compliant [10]. Companies have to overcome huge challenges to become compliant and need to start before the implementation of PoPI. Moreover, companies that are already implementing measures to comply with PoPI requirements are concerned that they will not be compliant in time [10]. A study conducted by Cibecs in 2012 shows that 26% of South African companies are in the process of complying with the requirements of PoPI [37]. They found that as many as 38% of the companies surveyed still have outdated security measures in place. It therefore seems as though company efforts to comply with PoPI are still in progress [2, 37].

5. USE OF PERSONAL INFORMATION BY THE INSURANCE INDUSTRY

The insurance industry processes large quantities of personal information for the purposes of underwriting [63]. To be competitive in the insurance industry, companies have to market their products. One marketing method used by insurance companies is cold-calling. According to Millard [33], although the Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FIAS) 37 of 2002 [34] and the CPA [23] address this issue, PoPI will eliminate the cold-calling sales technique altogether. Section 69 of PoPI prohibits unsolicited marketing unless the customer (data subject) consents to it [17].

According to a global study done in the health services, 6% of data breaches are committed by insurance companies, the third highest out of 17 industries [35]. Cybersecurity insurance is expanding rapidly in the insurance market, with forecast annual sales of $7.5 billion globally by 2020 by the global cyber insurance market [36, 37]. If an insurance company wants to expand its products and provide cybersecurity insurance in South Africa, it must set an example and comply fully with the requirements of PoPI, especially if it plans to use direct marketing to create awareness about its cybersecurity insurance products.

Many companies in South Africa believe that it will require significant effort to become PoPI compliant, with some estimating that it could take in excess of 9 000 hours [10]. While some companies have started with the implementation process, research indicates that it could take more than a year to become fully compliant, while many companies believe that it could take up to three to five to achieve this [10, 30]. Although it is thought that companies have started the process of implementing the conditions of PoPI, many might not yet have done so. Once the provisions of PoPI come into effect, companies will have one year to comply with the Act.

6. RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The following main research question has therefore been formulated:

- Do South African insurance companies only contact customers if they have opted-in for marketing and communication purposes as required by PoPI?

The answer to this research question could indicate to insurance companies whether they are ready to comply with certain conditions for marketing in PoPI. While establishing the answer for the research question the experiment also allows the following sub research questions to be answered:

a. Do all companies in the sample include an opt in or opt out preference for direct marketing on their websites when collecting personal information of data subjects for the purpose of an online insurance quote?

b. Did companies that were not part of the sample contact the data subject?

c. Do all companies in the sample have a privacy disclaimer or policy on their website?

d. Did all SMS's received include an opt out preference, free of charge to the data subject?

e. Do all companies in the sample use a secure method to process the data subject's personal information when collecting their personal information via an online insurance quote?

7. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The research methodology used is based on an experimental design. The researchers made use of two new cellphone numbers with related e-mail accounts that were created for the purpose of the experiment. These were used as contact information when requesting online quotes from 20 insurance companies. For the one cellphone number the researchers aimed to opt in and for the other to opt out for direct marketing communication. The researchers then monitored communication received on the cellphone numbers and related e-mail accounts to establish if the opt in and opt out preferences were honoured as well as to examine a few other aspects which were considered as part of the experiment.

The next section provides a detailed overview of the research methodology.

7.1 Research paradigm

A positivist paradigm applies to this research. A positivist paradigm is based on realist ontology beliefs, where there is an objective reality according to representational epistemology in terms of which symbols are used to explain and describe the objective reality accurately [38, 39]. Cohen and Crabtree [39] state that positivism can reveal the causal relationship that exists in social life, such as the flow and use of personal information in the economy.

7.2 Research design

De Villiers [50] explains that a positivist paradigm is one where knowledge is created through the application of mainly empirical methods that could include experiments whereby reliable, consistent and unbiased data are obtained. An experimental design was used for this research project. Experiments are defined by Payne as, "ways of assessing causal relationships, by randomly allocating 'subjects' to two groups and then comparing one (the 'control group') in which no changes are made, with the other (the 'test group') who are subjected to some manipulation or stimulus" [64]. This design allowed the researchers to have control over the experiment which also strengthens the internal validity [40]. Miller and Brewer [41] suggest that if the experiment is carried out correctly, the testing effect, mortality, history and maturation, as possible pitfalls of internal validity, will not have an effect on the research outcome from an internal validity perspective.

Two groups were involved in the research, namely, the experimental and the control group; a stimulus was applied to the experimental group and no stimulus was applied to the control group [41].

7.3 Control group

In this research, the control group comprised four new SIM cards that were purchased, one from each of the major cellphone providers in South Africa, referred to as cellphone provider I, II, III and IV. The associated cellphone numbers were not deposited in the economy and were not used to obtain any online insurance quotes or to make any phone calls. For the purpose of this experiment the lecturers involved in the project were responsible for monitoring the control group.

7.4 Experimental group

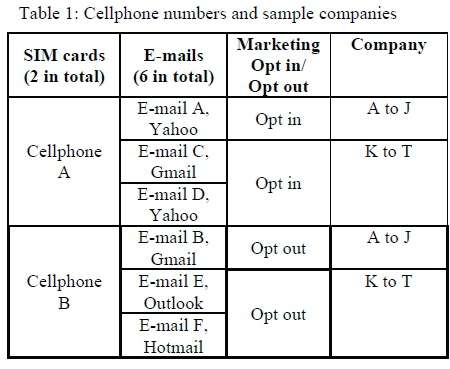

To conduct the experiment, two new cellphone numbers (cellphone A and B) and six new e-mail addresses (emails A, B, C, D, E and F) were utilised, which allowed the researchers to supply personal information when requesting online quotations from the sample of insurance companies. Cellphones A and B were obtained from the same cellphone provider, referred to as cellphone provider IV. In this group project twenty students participated, each obtaining two new cellphone numbers from the various cellphone providers to conduct the experiment. The scope in this paper is however limited to only one instance of the experiment and thus only the experimental results of this specific insurance industry experiment is reported on.

In the case of the experimental group, the newly purchased cellphone numbers were deposited in the economy. External validity could affect the experiment where the experimental and control groups are not identical to start with [41]. Some factors that could affect the external validity are the processes followed by the various retail outlets where the cellphone numbers were obtained, which could lead to data leakage or sharing. In addition, some cellphone numbers might relate to numbers that are reused by the cellphone providers, which could affect the results as the previous owner would have already shared the cellphone number with organisations that might conduct direct marketing. These factors were considered by the researchers.

7.5 Sample

This research focused on the insurance industry in South Africa. The insurance industry collects personal information from online applications, telephonic marketing and hard-copy applications, as well as their claim processes.

The geographical area was limited to South Africa. The head offices of the insurance companies included in the sample are mainly located in the metropolitan areas of each province.

Twenty insurance companies were identified and included in the sample. The sampling method used for this research project was a convenience sample [36]. A prerequisite for inclusion in the sampling was that the insurance company had a website where online insurance quotes could be requested as part of the experiment. This experiment was conducted from a consumer perspective and hence, to protect the confidentiality of the companies in the sample, the company names are withheld.

7.6 Experiment Preparation

Table 1 shows the two new cellphone numbers, Cellphone A and Cellphone B, which were purchased in March 2015 for the purpose of this research. These cellphone numbers were purchased under the personal information of one of the researchers. For the remainder of the discussion this profile will be referred to as the "data subject". The researchers used the same profile in the dealings with all the insurance companies selected for the research. When the researchers purchased the SIM cards from the service providers, personal information was verified in line with the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-Related Information Act (RICA), 2002 [43].

The six e-mail addresses were created in April 2015, each using a different internet service provider. Two of the six e-mail addresses were linked to the cellphone numbers A and B, see Table 1.

Cellphone numbers A and B and the related e-mail addresses A and B were deposited at the first 10 insurance companies, A to J.

The remaining four e-mail addresses (e-mails C, D, E, and F) were included in the personal information supplied to the next ten insurance companies (K to T) in the sample. The researchers set out to use these e-mail addresses for opt in and opt out preferences without any cellphone numbers being linked to the e-mail addresses. However, it was found that no information could be submitted (no online insurance quote could be obtained) without providing a cellphone number. Cellphone A was therefore also submitted with e-mail addresses C and D, and cellphone B was submitted with e-mail addresses E and F.

7.7 Conducting the Experiment

Personal information was deposited in the insurance market in May 2015. The method used to deposit personal information was to request life insurance or short-term policy quotations from insurance companies using the online application process on the companies' websites. For the duration of this research project, the cellphone numbers and e-mail accounts were not used for any other purpose.

Figure 1 shows the personal information fields that the insurance companies requested in order to process the insurance quotes. All 20 companies required a name and surname followed by the date of birth. Less than half required the personal identification number and some required the data subject's occupation and income. These fields of personal information were therefore included in the customer records in the companies' databases. In this way the personal information of the profile used was deposited in the economy, and the researchers were able to monitor the flow of the personal information through the communications received on the new cellphone numbers and e-mail addresses.

The researchers aimed to opt in for direct marketing for cellphone A and to opt out for cellphone B. However, opt in and opt out preferences were provided on only six of the insurance company websites. Where the opt in or opt out preferences were not provided on the websites, the researchers still requested online insurance quotes.

The researchers activated the control group cellphone numbers on the network by sending at least one SMS to another number. No stimuli were applied to these numbers, meaning that the researchers did not deposit the cellphone numbers with any company nor did they use the associated cellphones for phone calls or text messaging. This would eliminate any biased results during the experiment because the cellphone numbers were not subjected to any experimental treatment.

7.8 Data Collection

Data were collected by means of cellphone calls, SMS's and e-mail messages received from companies that contacted the data subject on either of the two cellphone numbers or any of the six e-mail addresses created for this experiment. The cellphone calls were answered by the researchers and were received from just after eight in the morning until four in the afternoon. Information about each cellphone call and SMS was recorded daily on a spreadsheet, and information about e-mail messages received was recorded twice a week.

The time frame for collection was from May to October 2015. During this time, the researchers recorded certain aspects, such as the origin of contact details; whether the data subject opted in for the communication; whether there was an option to opt out of any future communication; whether the company was one of the companies in the sample; whether the data subject was liable for any cost when opting out; and whether the data subject was contacted by an automated calling machine.

8. RESULTS

8.1. Overall contacts received

In total, the data subject was contacted 84 times during the data collection period on either the cellphone numbers or e-mail addresses created for the experiment. Fifty-five per cent of all communications were received via SMS. Twenty-eight per cent were received via e-mail messages when quotations had been requested from insurance companies. Cellphone calls accounted for only 17% of the contacts with the companies (see figure 2). These calls were received from the insurance companies that called about the quotations requested.

Only 22% (10 out of 46) of the SMS's were sent by those insurance companies that had the personal information of the data subject, whereas eight of the 46 SMS's were sent by the cellphone service provider. The remaining 28 of the 46 SMS's received came from entities that were not part of the sample and hence had no permission to contact the data subject nor did they have any information about the data subject.

8.2. Contacts received from companies in the sample and not in the sample

Forty-eight of all the contacts were linked to companies included in the sample and eight contacts were received from the service providers.

Twenty-eight contacts (excluding the service provider contacts) - thus 33% - were from companies that were not part of the 20 companies in the sample. These contacts represented 18 different companies. This indicates that the information could have been shared with third parties who used it to contact the data subject, as these companies did not have permission to contact the data subject for marketing purposes via the cellphone numbers or e-mail addresses used in the research. Most of these companies contacted the data subject only once, but two companies contacted the data subject at least eight times each during the experiment to offer financial services or to give the notification that they (data subject) had won a competition.

8.3. Contacts received for opt in and opt out preferences

• Opt in group contacts received

The data subject received 28 contacts in the opt in group. This excludes contacts from the cellphone service provider and companies not in the sample. These were from a total of 14 companies. Of these 14, only two companies provided the option for the data subject to actually opt in on their website when requesting the online quote, namely company O which contacted the data subject in seven instances and company F which contacted the researcher on one occasion. The 12 companies that did not provide for an opt in option still contacted the data subject. This is not a concern if data subject planned to opt in, but it is a concern if data subject planned to opt out. It indicates compliance with the CPA where the opt out is included, but not with the requirements of PoPI that require opt in.

• Opt out group contact received

The opt out group received a total of 20 contacts emanating from seven different companies. This excludes contacts from the cellphone service provider and companies not in the sample. Of these seven companies, only two provided the option on their website to opt out. However, these two companies, namely company C and O, still contacted the data subject for direct marketing. The other five companies, A, D, E, K and P, contacted the researcher without having given the option to opt out on their website when requesting the online insurance quote. This is a concern if the data subject planned to opt out as the option was not provided and the companies still contacted the researcher. Three of these companies, namely companies A, K and P, though, had the opt-out preference in the SMS's they sent, which indicates that they comply with the CPA.

Table 3 provides a summary per company of the number of times the data subject was contacted, by e-mail, SMS or cellphone calls. This table includes all contacts for websites, whether the opt in and opt out preference was available or not.

The results indicate that almost half of the contacts made by Company O were permitted and used e-mail address C or D. There was no consent for the other half of the communications received from Company O, as the data subject had opted out when using e-mail addresses E and F. There was no consent for 90% (8 out of 9) of contacts made by Company K, but there was a privacy disclaimer on the website regarding the protection of personal information that said that customers would be contacted only about a requested quotation.

Company A contacted the data subject four times. This company also had a privacy disclaimer on its website, indicating that it would protect the data subject's personal information and would contact the client only about the quotation being requested. The data subject elected to opt out of communication from Company A, but no option was provided to opt out during the application process. The websites of Company A and Company K did not offer opt in or opt out options on their application/quotation systems, but they did include privacy disclaimers that promised to protect the customer's personal information.

Thirty-eight per cent of all the companies that contacted the data subject did not have the data subject's personal details, and it was unknown how the contact details had been obtained for 35% of the communications received.

Only 43% of the SMS's received included the option to opt out of communications. Most of the 43% of the SMS's that included the option to opt out indicated that standard rates would apply to opt out. None of the phone calls received were from an automated calling machine.

Table 4 gives a summary of all the contacts received for cellphones A and B per month without distinguishing between the companies that provided the option to opt in or opt out on their websites. Most of the opt in group contacts were received in the first month for cellphone A. The data indicate that both cellphone numbers received communications.

The control group received a total of 70 communications, nine missed calls and 61 SMS's. This was almost as much as the experimental group, however, 55 of the contacts were from the cellphone service providers. Three of the cellphone numbers (Cellphone Provider I; Cellphone Provider II; and Cellphone Provider III) did not receive any communication from other companies. The cellphone number from Cellphone Provider IV accounted for nine missed calls, of which six were from different numbers, as well as six SMS's from other companies. These SMS's were messages from financial service providers or a message that the data subject had won a competition.

This cellphone number might have been owned and used by another individual in the past, which could explain the contacts from other organisations. Alternatively, it could indicate that the data subject's information was leaked at the cellphone provider or retail store where the sim was purchased and not necessarily by the insurance companies. This could be further investigated in future research by increasing the sample of the control and experimental groups to determine the source of contacts and whether the cellphone numbers are linked to a marketing database.

9. DISCUSSION

The data subject received contacts from companies where the opt out preference was applied as well as contacts from companies that did not give the data subject the option to opt in or opt out when requesting an online insurance quote. This answers the main research question, namely, "Do South African insurance companies only contact customers if they have opted-in for marketing and communication purposes as required by PoPI?", showing that consumers are contacted even if they have opted out of direct marketing. Section 69(1) of PoPI stipulates that data subjects must give their consent to the responsible party to process their personal information and must opt in for marketing purposes.

At the time when the data was submitted via the insurance companies' websites, only six of the 20 companies made provision for consumers to opt in or opt out for any marketing communications. This answers sub research question a, "Do all companies in the sample include an opt in or opt out preference for direct marketing on their websites when collecting personal information of data subjects for the purpose of an online insurance quote?" In future, companies will have to give new customers the option to opt in for marketing and communication, and allow existing customers to opt out at any time for such purposes, as per section 69 of PoPI [17].

An additional 18 companies that were not part of the sample also contacted the data subject, which answers the sub research question, b aiming to establish if companies that were not part of the sample might contact the data subject for direct marketing. Direct marketing from the companies that were not part of the sample are not in compliance with the requirements of PoPI, as these companies contacted the data subject via SMS for marketing purposes without having consent to do so.

Only two companies included a privacy disclaimer on their website, stating that they valued personal information, would protect it and would contact customers only about the product or service they were interested in. The remainder of the companies did not comply with section 18 of PoPI, which requires that the data subject must be aware of the purpose of information collection and other aspects of processing in terms of transparency and openness requirements [17]. Research question c, intended to establish if privacy disclaimers or policies were available on the sample company websites, has thus been answered.

According to section 69(4b) of PoPI, the responsible party or third parties responsible for direct marketing must supply their address or contact details to enable recipients to opt out of any future communication [17]. The 43% of companies that sent SMS's without an opt out option therefore did not comply with PoPI or the CPA. In addition the data subject had to pay standard SMS rates to opt out for the other SMS's. This answers

sub research question d, which aimed to establish if all SMS's received included an opt out preference, free of charge of the data subject. Data subjects must be given the option to opt out of or withdraw their consent for the processing of information and future marketing communications from third parties as per section 69(4b) of PoPI [17].

Because SMS's were received from unknown senders as well as companies that were not included in the sample, it was difficult to establish the origin of all messages, or the ways in which personal information was leaked or shared to these entities, because the researchers were in no position to confirm how the entity got the information to make the contact. However, these messages indicated that data, specifically personal information, were shared in the economy with third parties as the cellphone numbers and e-mail addresses were used only when submitting the information on the websites of insurance companies included in the sample.

The last sub research question, e, aimed to establish if all companies in the sample used a secure method to process the data subject's personal information when they request an online insurance quote. Thirty five per cent of the companies did not use a secure website when processing personal information when the online insurance quotes were obtained. Responsible parties are required, according to section 19 of PoPI, to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of personal information which they process [17]. This is a vulnerability that could result in unauthorised access to confidential information, such as income or health status, of the data subject.

9.1 Summary of the research findings

Table 5 gives a summary of the findings in the experiment, highlighting the aspects found that were not in compliance with PoPI based on the research scope as well as high level recommendations.

9.2 Limitations

For the purpose of the experiment it was assumed that companies were in the process of becoming compliant with PoPI as, to date, PoPI has been promulgated for three years and companies will have only one year to become compliant once it is in effect. A limitation was that the conditions of PoPI, apart from those relating to the establishment of the Information Regulator, were not yet effective, which means that companies do not have to be compliant as yet unless they are a multinational organisation operating in other jurisdictions with data protection laws. This could be the reason why the results of the research indicated non-compliance for certain sections and conditions of PoPI. Taking into consideration that it could take between three and five years to become compliant, it is anticipated that companies should have started to implement measures to prepare for compliance.

Another limitation of the research project was the limited time frame available to monitor communication received on the cellphones and e-mail addresses. This limitation arose due to the project timeline being in line with university year module timelines. A longer time period could be valuable in determining if all companies that were not part of the sample would continue to contact the data subject without an opt out preference.

A further limitation was that some of the cellphone numbers used could have previously belonged to other people, therefore some of the communications received via SMS during the research might have been meant for the previous owner of a cellphone number. Not all communications were therefore necessarily applicable to the research.

Another limitation to consider in the research project is that there was no control over the information processed in line with the RICA Act of 2002 [43] by the store and the service provider from whom the SIM cards were purchased. Personal information could also have been leaked during this process.

A larger sample across the cellphone service providers is required so as to include all cellphone service providers in the experiment and thus allow further investigation into where the information is shared. Additional control groups - such as a control group for the internet service providers - could also be valuable to establish any data leakage from the creation of the e-mail addresses. A relationship between the e-mail addresses and the contacts received was not conducted in this study and further research could investigate any potential correlation with the communications received.

A further factor to consider is phishing attempts that could have been used to obtain personal information for malicious purposes [61] especially in the instances where the data subject was contacted in respect of competition prizes that they had supposedly won. However, the data subject did not respond to any of the SMS's or e-mails received.

10. CONCLUSION

The objective of this research was to establish whether certain conditions of PoPI were complied with from a direct marketing perspective. The insurance industry of South Africa formed the sample population and an experimental design was used. Compliance was investigated by establishing whether the consumer (data subject) was contacted by the companies in the selected sample if they had not opted in for any communication and direct marketing.

The results indicated that a number of companies in the sample (excluding the cellphone service providers) that contacted the data subject did not have the data subject's consent for direct marketing. Some of the companies that contacted the data subject were not even part of the original sample where the cellphone and e-mail addresses had been deposited, indicating that data could have been shared or leaked. In addition, almost half of the SMS's received did not include the option to opt out, the majority of the insurance company websites did not have a privacy disclaimer or the option the opt in or opt out when requesting an online insurance quote.

Future research using a longer time frame, inclusion of all cellphone providers and additional control groups would be necessary to monitor the flow of personal information and compliance with the direct marketing requirements of PoPI in the insurance industry, and in other industries, in South Africa. Additional value will be added if the experiment is repeated once PoPI is in effect.

11. REFERENCES

[1] L.F Chen. and R. Ismail, "Information Technology program students' awareness and perceptions towards personal data protection and privacy", Proceedings: 3rd International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems, ICRIIS, pp. 434-438, 2013.

[2] C. Doyle and M. Bagaric, "The right to privacy: appealing, but flawed", The International Journal of Human Rights, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 3-36, 2005 [ Links ]

[3] V. Hiranandani, "Privacy and security in the digital age: contemporary challenges and future directions", The International Journal of Human Rights, Vol. 15 No. 7, pp. 1091-1106, 2011. [ Links ]

[4] B. Van der Sloot, "Do privacy and data protection rules apply to legal persons and should they? A proposal for a two-tiered system", Computer Law & Security Review, Vol. 31 No. 1, pp. 26-45, 2015. [ Links ]

[5] E. Goodman, "Design and ethics in the era of big data", Interactions, Vol. 21 No. 3, pp. 22-24, 2014. [ Links ]

[6] B. Borena, F. Belanger and D. Ejigu, "Information Privacy Protection Practices in Africa: A Review Through the Lens of Critical Social Theory", Proceedings: 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences Information, pp. 3490-3497, 2015.

[7] M. De Bruyn, "The Protection of Personal Information Act and Its Impact on Freedom of Information", International Business & Economics Research Journal, Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 1315-1340, 2014. [ Links ]

[8] D. Milo and O. Ampofo-anti, "A not so private world", Without Prejudice, Vol. 14 No. 09, pp. 30-32, 2013. [ Links ]

[9] P. Prinsloo, E. Archer, G. Barnes, Y. Chetty and D. van Zyl, "Big(ger) data as better data in open distance learning", International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 284-306, 2015. [ Links ]

[10] PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), "The protection of personal information bill: The journey to implementation", [Online]. Available: https://www.pwc.co.za/en/assets/pdf/popi-white-paper-2011.pdf (Accessed 24 February 2016), 2011.

[11] G. Greenleaf, "Sheherezade and the 101 Data Privacy Laws: Origins, Significance and Global Trajectories", Journal of Law, Information & Science, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 1-18, 2014.

[12] H.N. Olinger, J.J. Britz, and M.S. Olivier, "Western privacy and/or Ubuntu? Some critical comments on the influences in the forthcoming data privacy bill in South Africa", International Information and Library Review, Vol. 39 No. 1, pp. 31-43, 2007.

[13] Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 1995. [Online]. Available: http://ec.europa.eu/justice/policies/privacy/docs/95-46-ce/dir1995-46_part1_en.pdf, 1995.

[14] General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of 2012. [Online]. Available: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX: 52012PC0011&from=EN, 2012.

[15] Hunton and Williams, "The proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation: A guide for in-house lawyers", [Online]. Available: https://www.huntonregulationtracker.com/files/Uploads/Documents/EU%20Data%20Prote ction%20Reg%20Tracker/Hunton_Guide_to_the_EU_General_Data_Protection_Regulation.pdf , 2015.

[16] Y. Diaz-Tellez, E.L. Bodanese, S.K. Nair and T. Dimitrakos, "An architecture for the enforcement of privacy and security requirements in internet-centric services", Proceedings: 11th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications, TrustCom-2012 - 11th IEEE International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Communications (IUCC-2012), pp. 1024-1031, 2012.

[17] Protection of Personal Information Act (PoPI) 4 of 2013, Vol. 581, No. 37067, Act No. 4 of 2013. Cape Town, South Africa, [Online]. Available:http://www.acts.co.za/consumer-protection-act-2008/index.html, 2013.

[18] Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) 2 of 2000, South African Government, [Online]. Available: http://www.acts.co.za/promotion-of-access-to-information-act-2000/index.html, 2000.

[19] The Presidency, President Zuma appoints Chairperson and members of the Information Regulator, [Online]. Available: http://www.thepresidency gov.za/pebble.asp?relid=22940, 2016.

[20] L. Pillay, "The partial commencement of the Protection of Personal Information Act , 2013", Without Prejudice, Vol. 14 No. 8, p. 54, 2014.

[21] S. Wilson, "Big data held to privacy laws, too", Correspondence, Macmillan Publishers Limited., Vol. 519, p. 414, 2015.

[22] B.N. Magolego, "Personal data on the Internet - can POPI protect you?", De Rebus, No. 548, pp. 20-22, 2014.

[23] Consumers Protection Act (CPA), 68 of 2008. South African Government, [Online]. Available: http://www.acts.co.za/consumer-protection-act-2008/, 2015.

[24] M. Calaguas, "South African Parliament Enacts Comprehensive Data Protection Law: An Overview of the Protection of Personal Information Bill", Africa Law Today, No. 3, pp. 1-6, 2013.

[25] I.P. Swart, M.M. Grobler, and B. Irwin: "Visualization of a data leak", Proceedings: 21st Conference on the Domestic Use of Energy, pp. 1-8, 2013.

[26] J.G. Botha, M.M. Eloff and I. Swart, "The effects of the PoPI Act on small and medium enterprises in South Africa", Proceedings: Information Security for South Africa (ISSA2015), pp. 1-8, 2015.

[27] H.G. Miller and P. Mork, "From data to decisions: a value chain for big data", IT Professional, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp.57-59, 2013.

[28] European Commission, A European strategy on the data value chain. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/en/news/elements-data-value-chain-strategy, 2013.

[29] B. Hamann and S. Papadopoulos, "Direct marketing and spam via electronic communications: An analysis of the regulatory framework in South Africa", De Jure, Vol. 47 No. 1, pp. 42-62, 2013.

[30] S. Dolnicar and Y. Jordaan, "A Market-Oriented Approach to Responsibly Managing Information Privacy Concerns in Direct Marketing", Journal of Advertising, Vol. 36 No. 2, pp. 123-149, 2007.

[31] Y.L. Lai and K.L. Hui, "Internet Opt-In and Opt-Out: Investigating the Roles of Frames, Defaults and Privacy Concerns", Proceedings: 2006 ACM SIGMIS CPR Conference on Computer Personnel Research, pp. 253-263, 2006.

[32] S. Bellman, E.J. Johnson and G.L. Lohse, "On site: to opt-in or opt-out? It depends on the question", Communications of the ACM, Vol. 44 No. 2, pp. 25-27, 2001.

[33] D. Millard, "Hello, POPI? On cold calling, financial intermediaries and advisors and the Protection of Personal Information Bill", Journal of Contemporary Roman-Dutch Law, Vol. 76, pp. 604-622, 2013.

[34] Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services (FIAS) Act, 2002 (Act No. 37 of 2002). [Online]. Available: http://www.acts.co.za/financial-advisory-and-intermediary-services-act-2002/, 2002.

[35] S. Widup, G. Bassett, D. Hylender, B. Rudis, M. Spitler, "2015 Protected Health Information Data Breach Report", [Online]. Available: http://www.verizonenterprise.com/resources/reports/rp_2015protected-health-information-data-breach- report_en_xg.pdf, 2015.

[36] PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), "Turnaround and transformation in cybersecurity", [Online]. Available: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/consulting- services/information-security-survey/assets/pwc-gsiss-2016-financial-services.pdf, 2015.

[37] CIBECS, "2012 State of business data protection in South Africa", [Online]. Available: http://offers.cibecs.com/state-of-business-data-protection-in-sa, pp.14, 2012.

[38] J.D. Brewer, "The A-Z of Social Research Positivism", SAGE Research Methods, pp. 236-238, 2015.

[39] D. Cohen and B. Crabtree, The Positivist Paradigm, [Online]. Available: http://www.qualres.org/HomePosi-3515.html, 2008.

[40] K. Staller, "Encyclopedia of Research Design", Encyclopedia of Research Design: Qualitative Research, pp. 1159-1164, 2010.

[41] R.L. Miller and J.D. Brewer, "The A-Z of Social Research Research design", SAGE Research Methods, pp. 263-269, 2003.

[42] H.J. Seltman, "Experimental Design and Analysis", p. 35., 2013.

[43] Regulation of Interception of Communication and Provision of Communication-related Information Act (RICA), Act 70 of 2002, South African Government, [Online]. Available: http://www.acts.co.za/regulation-of-interception-of-communications-and-provision-of-communication-related-information-act-2002/, 2002.

[44] P. Prinsloo, E. Archer, G. Barnes, Y. Chetty and D. Van Zyl, "Big(ger) data as better data in open distance learning", International Review of Research in Open and Distance, Learning, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 284-306, 2015.

[45] Europa, Factsheet EU-US Privacy Shield, [Online]. Available : http://ec.europa.eu/j ustice/data-protection/files/factsheets/factsheet_eu-us_privacy_shield_en.pdf.

[46] M. Madden and L. Rainie, Internet Science and Technology Research, Pew Research Centre 204, Privacy Perceptions, [Online]. Available: http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/11/12/privacy-perceptions/, 2014.

[47] D. Banister, Social Science Research Network, National Comprehensive Data Protection/Privacy Laws and Bills 2016 Map, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1951416, (Accessed 4 October 2016), 2016.

[48] U. Akpojivi and A. Bevan-Dye, "Mobile advertisement and information privacy perception amongst South African generation Y students", Telematics and Informatics, Vol. 32 No 2015, pp. 1-10, 2015.

[49] G. Sterling, Survey: 99 percent of consumers will share personal info for reward, but want brans to ask permission - Global Microsoft survey offers findings about attitudes towards data sharing, Marketing Land, [Online]. Available: http://marketingland.com/survey-99-percent-of-consumers-will-share-personal-info-for-rewards-also-want-brands-to-ask-permission-130786, 2015.

[50] M.R. De Villiers, "Models for interpretive information systems research, part 1: IS research, action research, grounded theory - a meta - study and examples," in Research Methodologies, Innovations and Philosophies in Software Systems Engineering and Information Systems, M. Mora, O. Gelman, A. Steenkamp, and M. S. Raisinghani, Eds. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 222-237, 2012.

[51] N. Nadasen, C. Pilkington, and A. Da Veiga, "Personal information value chains in the South African insurance industry - an experiment", Proceedings: CONF-IRM 2016 Proceedings International Conference on Information Resources Management (CONF-IRM), paper 28, May 2016.

[52] APEC, Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation. Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) privacy framework, [Online]. Available: http://publications.apec.org/publication-detail.php?pub_id=390,2005.

[53] Organisation of Economic Organisation and Development (OECD), OECD privacy principles, [Online]. Available: https://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/oecd_privacy_framework.pdf, 2013.

[54] British Standard BS 10012:2009, Data protection - Specification for a personal information management system, BSI, [Online]. Available: http://shop.bsigroup.com/ProductDetail/?pid=000000000030175849, 2009.

[55] ISO IEC 29100.2011 Information technology -Security techniques - Privacy framework, [Online]. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=45123, 2011.

[56] Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act (FACTA), Public Law 108-159-DEC.4, [Online]. Available: https://www.congress.gov/108/plaws/publ159/PLAW-108publ159.pdf, 2003.

[57] Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), Public Law 104-191, [Online]. Available: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-104publ191/pdf/PLAW- 104publ 191.pdf, 1996.

[58] Y. Jordaan, "Information privacy concerns of different South African socio-demographic groups", Southern African Business Review, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 19-38, 2007.

[59] Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, [Online]. Available: http://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/constitution-republic-south-africa-1996-1, 1996.

[60] Fair Information Practice Principles, IT Law Wikia, [Online]. Available: http://itlaw.wikia.com/wiki/Fair_Information_Practice_Principles

[61] C.P. Pfleeger, S.L. Pfleeger and J. Margulies, Security in Computing, Prentice-Hall Inc., USA, fifth edition, chapter 4, pp.274, 2015.

[62] Direct Marketing Association of SA, [Online]. Available: https://www.nationaloptout.co.za/, 2016

[63] Norton Rose Fulbright, PoPI and Insurance, [Online]. Available: http://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/knowledge/publications/74156/popi-and-insurance, 2013.

[64] G. Payne and J Payne, "Key concepts in social research", Experiments, Sage Publications, pp 85-88, 2016.