Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.27 n.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/13316

ARTICLE

Theory of Change and Theory of Education: Pedagogic and Curriculum Defects in Early Grade Reading Interventions in South Africa

Brahm Fleisch

University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa brahm.fleisch@wits.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9952-1209

ABSTRACT

Much of the field of educational change has focused on better understanding the theory of change, that is, what knowledge is needed to make substantial educational change, particularly improvement to learning outcomes at scale. This article suggests that the South African early grade reading study community may have been looking in the wrong place. The search for the optimal theory of change or theory of action is obviously very important, but could it not be that a key part of the problem is defects in our theory of education? It is argued that there may be something educationally unsound in certain aspects of the official pedagogy and curriculum. As such, the South African education system is unlikely to make much progress towards the goal of getting children to read for meaning by the time they are 10 years old if these defects are not addressed. To illustrate this argument, the article points to data from two examples in South African education policies on pedagogy and curriculum: the first relates to the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) Foundation Phase document's under-specification and weak guidance with reference to the teaching of phonics with linked decodable texts; the second concerns the CAPS document's privileging of an unworkable reading teaching methodology called Group Guided Reading. The article concludes that to achieve real knowledge breakthroughs, university academics working alongside researchers in government need to develop rigorous research programmes aimed at improving foundational learning outcomes.

Keywords: theory of change; early grade reading; decodable text; group guided reading

Introduction

Michael Fullan (1999) made the distinction between a theory of change and a theory of education. Much of the field of educational change has focused on better understanding the former, that is, what knowledge is needed to make substantial educational change, particularly improvement to learning outcomes at scale. In the original formulations, Fullan suggested that the cornerstone of change is the application of the correctly calibrated combination of capacity building (support) with accountability (pressure). Since then, the knowledge base of educational change derived from the theory of action has become far more sophisticated, with extensive and deeper insights into change at the instructional core, structural levers, authentic cooperative professional learning, differentiated change journeys and when and how to use accountability measures in progressive ways (Fleisch 2018; Hargreaves and Shirley 2020; Harris and Jones 2017; Hubers 2020; Mourshed, Chijioke, and Barber 2011).

In the South African context, much of the research on educational change has concentrated on investigating which approaches, and within those which combination of components elevate various learning outcomes (Ardington and Meiring 2020; Cilliers et al. 2022; Fleisch et al. 2016; Kotze, Fleisch, and Taylor 2019; NORC 2019; Zenex Foundation 2019). Using randomised control trials, these studies aimed to investigate questions such as: Do parent intervention models work better than structured pedagogic programme models? And within these, how important are the lesson plan and coaching components, and can virtual coaching replace onsite coaching? All these intervention studies, however, took as "given" the official curriculum and the theories of education, instructional methodologies and approaches embedded in the government documents.

My own work over the past 10 years has focused exclusively on using impact evaluation to build a robust knowledge base on how an aligned and coherent set of components, that is, lesson plans, learning materials and training/onsite coaching, would predictably leverage gains in early grade learning (Fleisch 2018). Although often diluted, much of the focus of the work of the field has concentrated on applying various theories of action in externally led and funded interventions designed to help teachers teach better. The mechanisms associated with these interventions generally assume that teachers would take up the new models in their daily routines and that these routines would improve teachers' use of time, space and resources, which in turn would lift learning achievement system-wide or at least in the schools in the interventions.

Although there were significant gains between 2006 and 2016 in the Progress in International Literacy Reading Study (PIRLS) results in South Africa, the proportion of learners achieving the minimum proficiency levels remained extremely low. The PIRLS 2021 results showed that the Covid epidemic had a devastating effect on children learning in the nine official African languages (Mullis et al. 2023). Notwithstanding some of the challenges with PIRLS as a measure of early grade literacy, if the pre-Covid October 2019 evaluation in the Early Grade Reading Study (EGRS) II is a valid and reliable measure of early grade reading levels, then even if the early period of improvement had taken place, the level of early grade learning remains very low for poor and rural children (similar results are reported in Spaull, Pretorius, and Mohohlwane 2020). In the Home Language component of that reading assessment (EGRS II), 18% of all sampled children who had progressed to Grade 3 could not read a single word in their home language, and two thirds could not read sufficiently fluently (35 words or more a minute read correctly) to make sense of a simple paragraph.1

Research in initial reading in transparent languages such as Welsh, German and Turkish (Öney and Durgunoglu 1997; Spencer and Hanley 2004; Wimmer and Hummer 1990) suggests that most children should be able to learn to read fluently after a year of systematic instruction. Notwithstanding the challenges of shifting teaching cultures system-wide, the fact that such a large proportion of learners fail to learn to read for meaning despite the more than 500 lessons they would have attended in the first three years of schooling begs the question, Why is our education system failing to teach children to read in their home languages?

This article suggests that in part the Early Grade Research Study may have been looking in the wrong place. The search for the optimal theory of change or theory of action is obviously very important, but could it not be that a key part of the problem is flaws in the prevailing approaches to teaching reading embedded in South Africa's government curriculum (CAPS) and the types of reading resources associated with it? To illustrate this, this article provides a provisional analysis of two examples of the first reading texts and an analysis of the core reading methodology recommended in the CAPS curriculum.

Phonics and Decodable Texts

It is often assumed that the core problem in reading is comprehension. This assumes that children can decode but lack the ability to link the words they decode to the meaning in the text. What the EGRS II, the earlier Reading Catch-Up Programme (RCUP) research (Fleisch, Pather, and Motilal 2017) and Spaull, Pretorius and Mohohlwane (2020) have shown is that children may be "barking at text", that is, communally chorusing texts selected by the teacher, but that they are not only having difficulty with comprehension, but are struggling to link the graphemes (the smallest meaningful contrastive units in a writing system) to the phonemes (distinct sound units). Children learning to read in township and rural schools struggle to convert written letters and letter clusters into corresponding sounds. Children learning to read in African languages are having difficulty with basic reading skills such as segmenting and blending large letter units such as prefixes, suffixes, and root words, making morphological reading strategies difficult. Although the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: Foundation Phase (CAPS) makes clear that 75 minutes per week is to be devoted to the teaching of phonological awareness and phonics, the curriculum policy document provides only very broad guidelines. For example, in the English Home Language curriculum, it recommends that Grade 1 Term 1 teachers should teach letter-sound relationships of single letters (at least 2 vowels and 6 consonants). In the absence of a strong scaffolded and sequenced phonics programme (like those that exist in English such as Letterland and Jolly Phonics), teachers teaching in one of the nine African languages would have little guidance on the structure, sequencing and pacing of daily phonics routines. Resources such as the Department of Basic Education's (DBE) Rainbow Workbooks and policy documents such as the Department of Education's (2008) Teaching Reading in the Early Grades: A Teacher's Handbook would not be of much help. In the latter, the only guidance provided is the following piece of information:

In the indigenous African languages, as well as Afrikaans, there is a nearly direct correspondence between the alphabet letters and the sounds they represent. The names and the sounds of the letters are generally the same, and letter sounds do not vary depending on what other letters are near it. Therefore, it is easier to teach phonemic awareness and phonics in these languages than it is in the English Language. (DoE 2008, 13)

What is critical, however, is not just the development of automaticity of going from phonemes to graphemes, segmenting and blending, but the extent to which this core bottom-up literacy skill gets linked to reading sentences and longer connected text with decodable words (words that are phonically regular, e.g., umama or cat). The tighter this link, the more likely that the bottom-up phonic and decoding skills would help young schoolchildren develop fluency and confidence.2

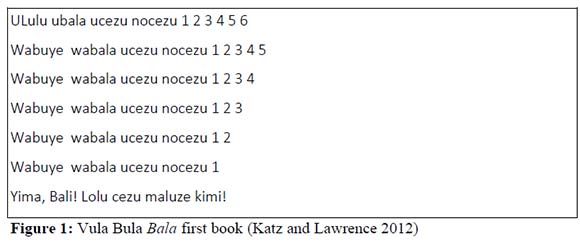

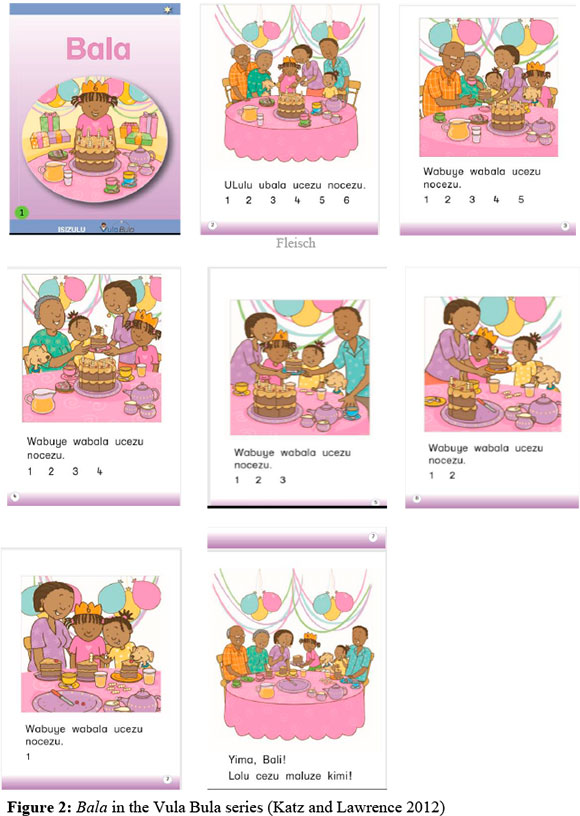

A simple comparison between two current Foundation Phase reading texts illustrates this point. The Vula Bula books are widely used in many early grade interventions and are designed with meaning making as a key pedagogic element. In the first book in the series, Bala, the authors use a repeated sentence combined with numbers and interesting pictures to set up a story with which the child can identify. Lulu has a birthday cake, and her mom gives each member of the family a piece of the cake. Lulu is seen in the pictures getting increasingly worried that there will not be a piece left for her. The story is genuinely engaging, and the repeated sentences allow for consolidation. The use of the name Lulu and the word ubala employs simple early phonic blends.

In terms of the three-cueing system of word identification (Goodman and Goodman 1977), this passage relies on pictorial and semantic cues and to a lesser extent on grapho-phonetic cues. In general, while the first semantic and syntactical cueing systems become increasingly central to word identification as children's reading improves and becomes more sophisticated, it could be argued that grapho-phonetics should be privileged if children are to decode words in very early stages of reading text.

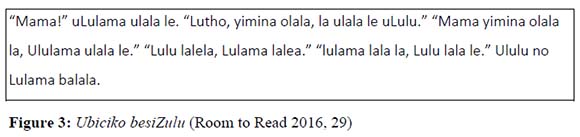

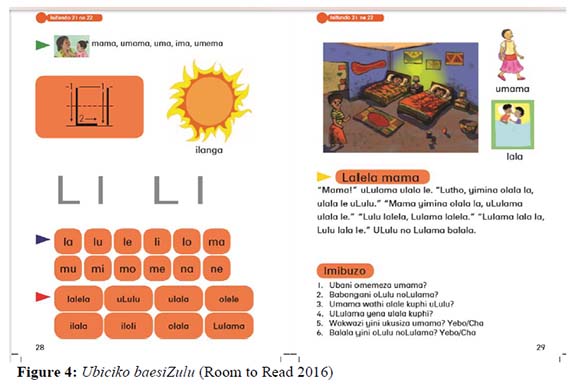

In contrast, the Room to Read reader Ubiciko baesiZulu stresses the grapho-phonetic cues and directly links the letters (graphemes) to sounds, focusing on the simplest single graphemes in the words in the first reading passage. The lesson immediately prior to the decodable text reading lesson would involve drills with the blends ma, mu, me etc. and the words associated with the first blends, for example, mama, umama, uma, ima, and umema. The new content in the new lesson focuses on teaching the letter L and a series of L syllables, such as la, lu, le, li, lo and the related words lalela, uLulu, ulala, olele, ilala, iloli, Olalalala, and Lulama. This is then followed by the passage, which clearly prioritises the grapho-phonetic cueing to help children decode the words. While the pictures in the text do help with semantic cueing, the priority is definitely given to the bottom-up assembly of the words using the smaller sound-letter cluster component parts. For more about the approach, see Kazungu (2023).

The examples from Vula Bula and Room to Read materials illustrate two different entry points into the learning-to-read journey. Vula Bula began with an emphasis on semantic meaning making very early in the first lessons. Room to Read materials make use of a substantially different approach in which priority is given to grapho-phonetics, segmentation and blending. Given the transparent nature of the language and the familiarity that teachers have with the ma, mu, me approach, it is likely that a systematic and structured version of the latter that builds up to decodable stories is more likely to help the majority of teachers help the majority of learners move towards easier word identification and ultimately decoding simple texts at the beginning stages of the learning-to-read journey. This simple comparative analysis of these two early grade reading texts illustrates both the educational defects in current approved materials and practices and what is needed to correct them. The absence of systematic phonics programmes with closely aligned decodable texts is a major gap in our approach to improving early grade reading system-wide.

Notwithstanding this critique, Bala type books have a fundamental role in the learning-to-read journey. Without extensive opportunity to read books that are fun and trigger children's pleasure in reading, reading fluency is unlikely to be developed rapidly.

CAPS on Group Guided Reading

The Department of Basic Education has issued a curriculum policy that directs teachers' teaching of reading in the Foundation Phase (DBE 2011). With reference to the national policy on approaches to the teaching of reading, the policy documents deal with teaching reading in each of the 11 official languages in separate documents, although each of the separate language documents appears to be translations rather than versions of the base English version.3

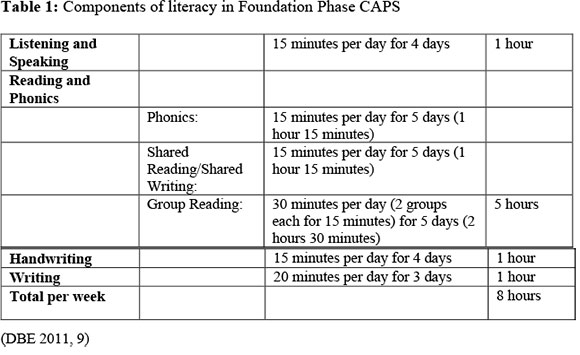

According to the policy, the subject of Home Language Literacy is to occupy teachers and learners for eight hours of the teaching week in Grade 1. These eight hours are to be divided between four distinct literacy components: listening and speaking; reading and phonics; handwriting; and writing. Reading and phonics is further subdivided into three subcomponents: phonics, shared reading/shared writing; and Group Guided Reading. Of the eight hours per week to be allocated to Home Language Literacy, two and a half hours are specifically to be devoted to group reading. Among all the components and subcomponents, this is the largest single allocation of time, and it is consistently the same proportion of time across the three grades. The various methodologies for teaching reading, that is shared reading, paired reading, and group guided reading and independently reading, while not explicitly stated as such, are likely informed by the gradual release of responsibility model (Pearson and Gallagher 1983). The assumption in the various methodologies is that the teacher would help the learners move from teacher modelling (shared reading) to joint responsibility (paired reading and group guided reading) to independent reading.

What exactly is to be done in the subcomponent, Group Guided Reading? The first guidance provided by the curriculum policy document is that during group guided teaching, teachers need to teach learners in ability groups. Each of these ability groups would consist of between six and 10 learners. The policy further requires the teacher to spend between 10 and 15 minutes per group and to work with and between one and two groups per day.

Within these 10-15-minute small group teaching sessions, the teacher would work with the six to 10 learners (who are more or less at the same reading level) with a text. The first task required by CAPS is for the teacher to form the ability groups. According to the policy, the easiest way of establishing the groups is to observe children reading a text and then allocate them to levels. Based on the reading levels, the teacher would assign the learners to specific reading groups.

The second task is the matching of learners to texts. The policy recommends that the texts that are selected follow the following requirements, that is, that learners are able to recognise and quickly decode 90-95% of words in the book. The text should be of interest to the learners and the learners should be able to read the text silently without finger pointing. The assumption that is made is that these specialised texts are to be selected from the classroom book collection of "graded readers".

The policy specifies the four steps in the Group Guided Reading session. The steps include an:

(1) introduction (2-3 minutes);

(2) picture talk or browsing;

(3) first reading; and

(4) discussion.

During the introduction, the teacher introduces the book or chapter and the topic and connects the topic to children's life experiences. This is followed by a more focused conversation called "picture talk" or a time of browsing. For younger children, specifically for Grade 1s, the picture talk step involves talking about illustrations and talking about what the children see. For older children, the two to three minutes after the introduction is "text talking" about features of the text such as captions and chapter headings. After between four and six minutes, the teacher begins to work with the children on the first reading. In the first reading, children read the text individually. Younger children (Grade 1s) read it in a whisper; older children read it silently. The teacher goes around from child to child to listen to each read a section of the text aloud. After hearing them, the teacher would ask the children questions such as: "What do you expect to read in this book?", and "Does that make sense to you?". The final step in the Group Guided Reading methodology is the discussion. During the Group Guided Reading discussion, the teacher returns to questions that came up during "text talk". The emphasis across the first and last steps is on comprehension. In subsequent Group Guided Reading sessions, the learners would return to the same text for re-reading to enhance fluency, grammar, and comprehension.

This curriculum policy makes four key assumptions. First, it assumes that teachers have the tools and expertise to accurately assess learners' reading levels as a precondition to allocate them to the correct level guided reading groups. Second, it is assumed that classrooms have graded readers in the right quantity at the right levels to meet the 9095% decoding accuracy rule. Third, the policy assumes that teachers have sufficient time and expertise in the "first reading" step to listen to each learner read aloud individually and have a meaningful exchange that would help the learner find solutions to reading challenges they encounter. Fourth, it assumes the Group Guided Reading time would be sufficient to allow children to develop fluency and comprehension skills.

This description of the CAPS policy makes it clear that the methodology is highly complex, with multiple layers of steps each requiring high levels of expertise. Group Guided Reading, as described in the policy, requires classrooms to have extensive reading material collections with multiple copies of each title. And it assumes that the eight to 12 minutes per week that children actually read in groups (much of the Group Guided Reading sessions is taken up with prediction and discussion of the text) is sufficient for children to practise reading to gain fluency and for the teachers to identify specific word attack skill problems.

Given the high levels of complexity associated with the methodology, the sophistication of the knowledge about how to address individualised reading challenges, and the range and quantity of resources required to make it work, it is highly unlikely that teachers would make effective use of it. The published case study research confirms this (Kruizinga and Nathanson 2010; Makumbila and Roland 2016).

This suggests that Group Guided Reading as a core methodology for the teaching of reading may be unworkable. What, if any, are the alternatives? Researchers need to better understand how whole-class paired-reading teaching, for example, would be more effective in large classes. There is certainly precedent that this would work both in the Tusome innovation in Kenya and the current approaches used by Room to Read.

Conclusion

Significant progress has been made in advancing the knowledge of system-wide change models aimed at improving early grade learning in South African schools. These advances have been made possible by the combined work of multiple interdisciplinary teams of university and government researchers undertaking robust randomised control trials, in-depth qualitative case studies and engaging with international literature. The local and international research community has consistently funded this research over the past decade or more.

That said, the purpose of this article is to signal that our current research programme is an important component of knowledge we need to improve learning at scale, but it is not sufficient to ensure policy makers offer teaching and learning that can work for teachers particularly in schools in poorer communities. To drive improved teaching and learning in the early grades, policy makers and programme designers need not only advances in the theory of change, but knowledge of what works at scale in curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment.

The analysis of the very early grade reading texts and policy on Group Guided Reading should not be misconstrued. The analysis should not be mistaken for policy recommendations. Rather, the purpose of their inclusion is to illustrate the need for more comprehensive and systematic research on early grade reading and mathematics curriculum and pedagogy in South Africa. Some of this work is currently underway. For example, the Department of Basic Education is completing an important education contribution by establishing early Foundation Phase reading benchmarks in South African languages.

To achieve real knowledge breakthroughs, university academics working alongside researchers in government need to develop clear and focused research programmes that undertake basic and applied research on topics central to improving foundational learning outcomes. This would involve collecting and interpreting representative samples of classroom teaching practices, measuring and analysing system-wide learning outcomes from both government and international sources, piloting cost-effective innovations in pedagogy and assessment, trialing promising approaches at scale, and analysing policy, implementation and take-up. As a research community, we need to publish findings in peer-reviewed journals, including both successful and unsuccessful findings. As important as the primary research is, the local research community also needs to regularly review and synthesise the research to assess its ongoing usefulness to policy makers and teachers in the profession.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Stephen Taylor, Yael Shalem, Vanessa Francis, Nick Taylor, Martin Gustafson, and Francine de Clercq for helpful comments on earlier drafts. That said, the author takes sole responsibility for the views expressed here. A version of this paper was presented at the Comparative and International Education Society Meeting, Washington DC, in February 2023.

References

Ardington, C., and T. Meiring. 2020. Midline 1: Impact Evaluation of the Funda Wande Coaching Intervention Midline Findings. Cape Town: Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit. [ Links ]

Castles, A., K. Rastle, and K. Nation. 2018. "Ending the Reading Wars: Reading Acquisition from Novice to Expert". Psychological Science in the Public Interest 19 (1): 5-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618772271. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J., B. Fleisch, J. Kotze, N. Mohohlwane, S. Taylor, and T. Thulare. 2022. "Can Virtual Replace In-Person Coaching? Experimental Evidence on Teacher Professional Development and Student Learning". Journal of Development Economics 155: 102815. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjdeveco.2021.102815. [ Links ]

DBE (Department of Basic Education). 2011. Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement: Foundation Phase Grades R-3; English Home Language. Pretoria: DBE. [ Links ]

DoE (Department of Education). 2008. Teaching Reading in the Early Grades: A Teacher's Handbook. Pretoria: DoE. [ Links ]

Fleisch, B. 2018. The Education Triple Cocktail: System-Wide Instructional Reform in South Africa. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press/Juta. https://doi.org/10.58331/UCTPRESS.50. [ Links ]

Fleisch, B., V. Schöer, G. Roberts, and A. Thornton. 2016. "System-Wide Improvement of Early-Grade Mathematics: New Evidence from the Gauteng Primary Language and Mathematics Strategy". International Journal of Educational Development 49: 157-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijedudev.2016.02.006 [ Links ]

Fleisch, B., K. Pather, and G. Motilal. 2017. "The Patterns and Prevalence of Monosyllabic Three-Letter-Word Spelling Errors Made by South African English First Additional Language Learners". South African Journal of Childhood Education 7 (1): 1 -10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v7i1.481. [ Links ]

Fullan, M. G. 1999. Change Forces-The Sequel. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203976708. [ Links ]

Goodman, K., and Y. Goodman. 1977. "Learning about Psycholinguistic Processes by Analyzing Oral Reading". Harvard Educational Review 47 (3): 317-33. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.47.3.528434xv67l534x8. [ Links ]

Hargreaves, A., and D. Shirley. 2020. "Leading from the Middle: Its Nature, Origins and Importance". Journal of Professional Capital and Community 5 (1): 92-114. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-06-2019-0013. [ Links ]

Harris, A., and M. Jones. 2017. "Leading Educational Change and Improvement at Scale: Some Inconvenient Truths about System Performance". International Journal of Leadership in Education 20 (5): 632-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2016.1274786. [ Links ]

Hatcher, P. J., C. Hulme, and A. W. Ellis. 1994. "Ameliorating Early Reading Failure by Integrating the Teaching of Reading and Phonological Skills: The Phonological Linkage Hypothesis". Child Development 65 (1): 41-57. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2307/1131364. [ Links ]

Hubers, M. D. 2020. "Paving the Way for Sustainable Educational Change: Reconceptualizing What It Means to Make Educational Changes That Last". Teaching and Teacher Education 93: 103083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103083. [ Links ]

Katz, J., and M. Lawrence. 2012. Bala. Johannesburg: Molteno. [ Links ]

Kazungu, T. 2023. "Decodable Texts in African Languages: Early Grade Reading Teachers' Views from South Africa 2023". Paper presented at the Comparative and International Education Society (CIES) Meeting, Washington DC.

Kotze, J., B. Fleisch, and S. Taylor. 2019. "Alternative Forms of Early Grade Instructional Coaching: Emerging Evidence from Field Experiments in South Africa". International Journal of Educational Development 66: 203-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijedudev.2018.09.004. [ Links ]

Kruizinga, A., and R. Nathanson. 2010. "An Evaluation of Guided Reading in Three Primary Schools in the Western Cape". Per Linguam: A Journal of Language Learning 26 (2): 67-76. https://doi.org/10.5785/26-2-22. [ Links ]

Makumbila, M. P., and C. B. Rowland. 2016. "Improving South African Third Graders' Reading Skills: Lessons Learnt from the Use of Guided Reading Approach". South African Journal of Childhood Education 6 (1): a367. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v6i1.367. [ Links ]

Mourshed, M., C. Chijioke, and M. Barber. 2011. "How the World's Most Improved School Systems Keep Getting Better". Voprosy Obrazovaniya/Educational Studies Moscow 1: 7-25. [ Links ]

Mullis, I. V. S., M. von Davier, P. Foy, B. Fishbein, K. A. Reynolds, and E. Wry. 2023. PIRLS 2021 International Results in Reading. Chestnut Hill, MA: Boston College, TIMSS and PIRLS International Study Center. https://doi.org/10.6017/lse.tpisc.tr2103.kb5342. [ Links ]

NORC (National Opinion Research Center). 2019. Story Powered Schools Impact Evaluation. PowerPoint presentation provided by Director of Research.

Öney, B., and A. Y. Durgunoğlu. 1997. "Beginning to Read in Turkish: A Phonologically Transparent Orthography". Applied Psycholinguistics 18 (1): 1 -15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S014271640000984X. [ Links ]

Pearson, P. D., and M. C. Gallagher. 1983. "The Instruction of Reading Comprehension". Contemporary Educational Psychology 8 (3): 317-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(83)90019-X. [ Links ]

Rigole, A., and P. Cooper. 2017. Literacy Program: South Africa (Sepedi): 2016 Midline Evaluation Report. Room to Read. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.roomtoread.org/media/4r1fglfx/2016-midline-end-of-grade-1-students-in-program-and-control-schools.pdf.

Spaull, N., E. Pretorius, and N. Mohohlwane. 2020. "Investigating the Comprehension Iceberg: Developing Empirical Benchmarks for Early-Grade Reading in Agglutinating African Languages". South African Journal of Childhood Education 10 (1): a773. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v10i1.773. [ Links ]

Spencer, L. H., and J. R. Hanley. 2004. "Learning a Transparent Orthography at Five Years Old: Reading Development of Children during Their First Year of Formal Reading Instruction in Wales". Journal of Research in Reading 27 (1): 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2004.00210.x. [ Links ]

Wimmer, H., and P. Hummer. 1990. "How German Speaking First Graders Read and Spell: Doubts on the Importance of the Logographic Stage". Applied Psycholinguistics 11 (4): 349-68. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716400009620. [ Links ]

Zenex Foundation. 2019. "NECT Early Grade Learning Programme Evaluation". Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.zenexfoundation.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/NECT-Learning-Brief.pdf.

1 In private correspondence, Dr Gustafson indicated that in the Grade 4 PIRLS, only 7% of learners in 2016 did not get a single constructed response answer right. As such, more research is needed to more accurately gauge the proportion of children in Grades 3 and 4 who are not making any progress in reading.

2 The following passage from Castle, Rastle, and Nation (2018, 16) provides a good insight into current thinking about the centrality of decodable text:

These kinds of books provide children with an opportunity to practice what they have been taught explicitly in the classroom and to allow them to experience success in reading independently very early in reading instruction, albeit with a rather restricted word set. These books also allow teachers to effectively structure and sequence children's exposure to grapheme-phoneme correspondences in text. Evidence suggests that phonics teaching is more effective when children are given immediate opportunities to apply what they have learned to their reading (Hatcher, Hulme, & Ellis, 1994); so, for these reasons, we believe that there is a good argument for using decodable readers in the very early stages of reading instruction.

3 We compared the isiZulu and Afrikaans versions and found them identical to the English version. This is despite very different language structures for the African languages and Afrikaans.