Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Education as Change

versão On-line ISSN 1947-9417

versão impressa ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.26 no.1 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/11270

ARTICLE

Implementing Multilingual Teacher Education: Reflections on the University of Fort Hare's Bi/Multilingual Bachelor of Education Degree Programme

Brian Ramadiro

University of Fort Hare, South Africa. bramadiro@ufh.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5273-360X

ABSTRACT

A central aim of this article is to reflect on the design and implementation of a bi/multilingual Bachelor of Education foundation phase programme offered at the University of Fort Hare from 2018. It reviews three major perspectives on bi/multilingualism: mother tongue-based bi/multilingual education, language and decoloniality, and translanguaging perspectives. It then proceeds to use these perspectives to discuss and illuminate various aspects of implementation, including the genesis of the programme, challenges of implementation, and decisions about curriculum, language use and assessment. It concludes with a brief discussion of lessons learnt for design of bi/multilingual education programmes in higher education.

Keywords: bi/multilingualism; bi/multilingual education; mother tongue-based bilingual education; translanguaging

Introduction

The main aim of this article is to reflect on the implementation of an isiXhosa, Afrikaans, and English bi/multilingual foundation phase initial teacher preparation Bachelor of Education (BEd) degree programme offered at the University of Fort Hare (UFH). In May 2022 the first cohort of 83 students graduated from this programme. The degree is among the first to respond to the problem that African language-speaking primary school teachers and foundation phase teachers in particular were being taught in English or Afrikaans, although policy required them to teach in the home language of the child. The mismatch between languages of teacher candidates and their prospective learners and those used by teacher education institutions is a major reason why the system is not making as much progress as it ought to. According to Van der Berg and Gustafsson (2019), while the South African schooling system is showing signs of improvement in educational outcomes, it is still plagued by deep and widespread educational failure, underachievement and inequality. This is partly because language is the primary tool through which knowledge is accessed, shared, negotiated, elaborated and displayed in learning, particularly in formal learning (Mercer 1995). The article sets out to describe and analyse the experience of implementing a bi/multilingual degree, drawing on three influential perspectives to multilingualism: mother tongue-based bi/multilingual education (MTBBE), language and decoloniality, and translanguaging. It then proceeds to use these perspectives to discuss and illuminate various aspects of implementation, including the genesis of the programme, challenges of implementation, and decisions about curriculum, language use and assessment. It concludes with a brief discussion of lessons learnt for designing bi/multilingual education programmes in higher education. I reflect on these aspects of implementation from the perspective of one who has been centrally involved in the design of the programme, materials development, and in teaching and programme coordination of the degree.

Perspectives on Multilingualism

This section reviews three major perspectives on bi/multilingualism: mother tongue-based bi/multilingual education (MTBBE), language and decoloniality, and translanguaging perspectives. Whatever the strengths or weaknesses of these perspectives, in the final analysis, their usefulness and longevity will be judged by the insights they provide and how well they withstand the rigours of theory development, policy analysis and practice. The article draws on all three perspectives of bi/multilingualism and bi/multilingual education to deepen analysis of the University of Fort Hare's bi/multilingual BEd degree, without glossing over actual differences between them.

Mother Tongue-Based Bi/Multilingual Education (MTBBE)

Mother tongue-based bi/multilingual education (MTBBE) is a perspective that is associated with the Project for Alternative Education in South Africa (PRAESA) and with the late Neville Alexander. His perspective on multilingualism essentially regards language as a "resource" (Van der Walt 2013). The most distinctive feature of Alexander's approach is that it is grounded in class analysis. He argues that language is a class issue in unequal societies, such as South Africa, and that inequality is expressed in both material wealth as well as in unequal access to "symbolic capital" (Bourdieu 1991), especially to high status and powerful languages such as English. Part of making society more equal requires ensuring that at the minimum, everybody has access to the key high-status language and, much more importantly, that people are enabled to use languages that they know best for self-empowerment, including to learn from preschool to higher education, to work and to take part in community and civic life. For the vast majority of people in South Africa, these are African languages. In order for these languages to work for people in this way, deliberate policy interventions and investments are needed to raise their status and to introduce and expand their use in various disciplines and domains of life. Failure to intervene positively to support African languages is in fact to reinforce the dominance of English and Afrikaans and of those who are proficient in these languages. Alexander dismisses the idea that there is something inherently sinister about language planning/management, arguing that (Alexander 2013, 93-4):

It is not true that languages simply develop "naturally", as it were. They are formed and manipulated within definite limits to suit the interests of different groups of people. This is very clear in the case of so-called standard languages, as opposed to non-standard varieties (dialects, sociolects). The former are invariably the preferred varieties of the ruling class or ruling strata in any given society. They prevail as the norm because of the economic, political-military or cultural-symbolic power of the rulers, not because they are "natural" in any meaning of the term.

He argues that language is a "dual phenomenon", meaning that under certain circumstances languages are lived as sets of "activities" (verbs) and, in others, as "things" (nouns) (Alexander 2014, 296). In the context of education, a teacher may recognise that a learner who is classified as speaking Sesotho as a "mother tongue" or "home language", for example, may in fact be speaking a variety of urban Sesotho that is mixed in complex and fluid ways with Setswana, isiZulu and English. A knowledgeable teacher may encourage the child to write an essay in their variety of Sesotho, thereby affirming their speech and identity. This would be an example of an act that recognises language as a set of idiosyncratic but legitimate communicative activities. On the other hand, when a teacher, for much of classroom time, taps into the unique language variety of the child (the known) to teach a standard or written variety of Sesotho (the relatively unknown) by, for example, setting the child a task to translate an essay the child has initially written in their specific variety of Sesotho to a standard variety, the teacher is now treating language as a temporarily stable and bounded entity that can be normed, taught and assessed. Good contemporary language teaching methodologies attempt to work precisely with this duality of language (studies reviewed in Lin 2013; Martin-Jones 1995, 2000). Thibault (2011, 212-19) makes a distinction between "first-order languaging" and "second-order language", a conception of language that has many similarities with Alexander's. First-order languaging refers to when people draw on all semiotic systems and linguistic repertoires available to them, including multiple languages, to express and make meaning in moment-to-moment interaction, while second-order language refers to those processes of language that operate on a longer and slower time and cultural scale and which language users experience as guides, norms or even constraints on language use, including on what is appropriate accent, lexicon and grammar in a range of situations.

The MTBBE perspective recognises that what is referred to as a "mother tongue", or "home language" or "first language" in education refers to any language(s) that the child is most familiar with when they begin formal schooling and is closest to a language used in formal schooling (Obanya 2004). From the conception of language as a dual phenomenon point of view, it is controversial or even "inconceivable" to assert that in complex African multilingual societies in which "overlaps, creativity, and crossovers between languages" are valued that somehow one can speak of a "mother tongue" or "first language" (Makalela 2019, 240). That language can be the father's or grandmother's language or, indeed, it can be more than one familiar language. In the case of children who move from one part of the country to another, for instance, a mother tongue, defined as the most familiar language, is a language widely spoken in the new community and to which the learner has access and that is offered in school. This would apply both to South African and non-South African nationals. Because a mother tongue-based bi/multilingual education system is intended to enable students to succeed in South African schooling, higher education, informal and formal work environments and broader multilingual society, it vertically and horizontally integrates the mother tongue with English (where it is not the mother tongue), and with the learning of other provincially and nationally important languages (Alexander 2006). MTBBE has the following core features and emphasises good teaching of:

• the mother tongue or primary language of the child as a subject in school from Grade R to Grade 12;

• content subjects in the mother tongue at least for the first six to eight years of schooling, depending on the sociolinguistic context and the needs of the child;

• a high status and powerful additional/second language beginning in the early grades (usually English);

• (South African) African languages to those who do not speak any, and teaching of additional African languages to those who do, in order to promote wider and multilayered communication, cross-cultural understanding, and contribute towards social cohesion; and,

• wherever possible, good teaching of content subjects bilingually in the mother tongue and a high-status additional language (English, in the vast majority of cases) from Grade 8 right into higher education.

Language and Decoloniality

A strand in this perspective focuses on addressing the legacy of colonialism and how to overcome it by "delinking" from it (e.g., Abdulatief, Guzula, and McKinney 2021). Much of this work received a shot in the arm during and in the aftermath of student protests for free higher education and a decolonised curriculum during 2015-2017. With regard to what McKinney and Christie call the "coloniality of language", they challenge Anglonormativity (McKinney 2016), the idea that there is one kind of English; that this English is white and middle class; and that the knowledge, experience, values and behaviours that are valuable and (universally) valid are those that occur and are inscribed in English and constituted in an English milieu. And more generally, where other knowledges are acknowledged to exist, they are regarded as local, particular, or marked, and, in contrast, Eurocentric knowledges are deemed to be universally valid, normative or unmarked (Menezes de Souza 2021). The critique is salient because, to this day, teaching of literacy in African languages, for example, and of phonics in particular, is predominantly described through sound-grapheme structures of and to the standard of English. From this perspective, curriculum seeks to provide knowledge of and enable students to discover the intricate relationships in which African languages are entangled and the "epistemic violence" visited on African subjectivities. Through what students are assigned to read and write inside and outside the classroom, and through the creation of "collaborative or collective [language and literacy] third space[s]" in which students and lecturers share, produce and transform knowledge using multimodal and bi/multilingual strategies of learning and communicating (McKinney and Christie 2022, 12), African languages are and can be resourced and repurposed for cognitive development.

A different strand of the decolonial perspective is that associated with Makoni and Pennycook (2007) and Makoni and Mashiri (2007). This strand seeks to "disinvent" and reconstitute languages, African languages in particular, freeing them from a European colonial linguistic and sociological imagination. It draws attention to the fact that the historical record, by and large, shows that, in most cases, standard African languages are an "invention" that often went with the creation of tribes to correspond to these languages. As an example, Makoni and Mashiri (2007) make the case that "Shona" the language and "Shona" the people are a colonial invention, and that standard Shona has played a crucial role in the formation of the social group. Like the translanguaging perspective discussed next, Makoni and Pennycook (2007, 2) seek not only to "acknowledge boundaries between languages", but to break them down and overturn the very idea that language exists at all as an "object". They regard as questionable notions such as "indigenous languages", "additive bilingualism" and "multilingualism"-notions that define MTBBE. Even so, they admit that although languages are social and cultural inventions, they have material effects in the world because they "constitute forms of 'social action and can function as agents of social and political power'" (Jaffe 1999, 15 cited in Makoni and Pennycook 2007, 2). The main problem with this perspective is that, while it is clear on the question of delinking from colonial knowledges and the need to link up with pre- and post-colonial knowledges, it is underspecified in relation to how to address colonial knowledge. The tradition of our own South African struggle did not seek simply to "cancel" colonial culture or knowledge systems, but to interrogate them and where desirable, transform, subsume and normalise aspects of them in our own intellectual traditions and historical ambience. In this sense, knowledge belongs to the whole of humanity. Such an interpretation of decoloniality takes for granted that intellectual progress builds upon what has gone before and incorporates experiences and insights from different geographies, periods and cultures making up today's cutting-edge ideas that, in principle, belong to the whole of humanity. It is in this sense that the idea of "universal knowledge" is defensible. An important goal of education is to support students to discover for themselves what is historically contingent, ideological, partial, and, indeed, valuable in "universal" knowledge and simultaneously to access and (re)construct) other, "pluriversal" knowledge systems (Mignolo 2013).

Translanguaging

The dominant stream of the translanguaging perspective seeks to break down artificial and ideological divides between languages. Its primary focus is not "language" but "languaging", a "move away from language as a noun or something that has been accomplished to language as a verb and an ongoing process" (Li 2011, 1224). In other words, this perspective is congruent with only one part of MTBBE's dual conception of language. Rather than focusing on named languages, translanguaging focuses on the "momentariness, instaneity and the transient nature of human communication" (Li and Lin 2019, 211). According to Li and Lin (2019, 210-11), the term "translanguaging" can be understood in at least three different ways. First, it refers to language practices that go between and beyond languages, working across spaces, and facilitating use of all semiotic resources available to an individual to make meaning. Second, it refers to language practices that challenge and transform established ways of thinking, "transforming not only subjectivities, but also cognitive and social structures" (211). Third, translaguaging is not just a tool for analysing language or education but also aims to provide insights into "human sociality, cognition and learning, social relations and social structures" (211). It can be observed that in order to go between and across languages presupposes the existence of "language" in some form and a set of social practices that both speakers and hearers in interaction recognise.

Makalela (2019, 238) has applied and developed the translanguaging perspective in the South African context in the following way. He acknowledges first that a translanguaging perspective needs to recognise and accommodate the tension between named and socially constructed languages such as isiXhosa or English, on the one hand, and the unique and transient ways in which individual speakers actually use their "communicative resources", which go beyond named languages, for meaning-making. Second, like Li and Lin (2019) above, he is not merely concerned about how each of the languages used by a speaker contributes to making meaning, but especially about those moments in communication when linguistic resources are "fluidly crossed over and disrupted" (Makalela 2019, 238). In the third place he makes an important analytical distinction between a hearer-centred versus a speaker-centred perspective on language. In this conception, the former is the linguist's or external view of language, which may be unrecognisable to the speaker, and the latter is a view internal to the speaker. A crucial and nuanced implication of this is that this duality calls for close theoretical analysis and empirical evidence to "guide programmatic scaling of practices" (Makalela 2019, 238). I argue that the hearer and speaker perspectives would have to be reconciled in certain social contexts and temporal scales in a similar way to how Alexander reconciles the "verb" and "noun" moments of languaging. Makalela's distinctive contribution to translanguaging is the formulation of ubuntu translanguaging, at the core of which is the claim that in multilingual communities a language is never complete without the other languages with which it coexists, and, therefore, without other people and communities with which it interacts in complex and multidirectional relations of interdependence. Translanguaging is not just "bilingualism" because students use their entire language repertoire to "engage cognitively and expand not only their language practices to encompass differences, but also take up socially relevant practices, including standard language practices for academic purposes" (Garcia and Li 2014, 71; my emphasis). In other words, the recognition that language is a social practice partly implies that within certain contexts and for specific purposes language can be "objectified" and can become an object of acquisition, teaching and learning, and assessment. In a recent qualitative meta-synthesis of the concept translanguaging and its applications, Bonacina-Pugh, Da Costa Cabral and Huang (2021) make a debatable distinction between studies that adopt a "fixed language approach" and those that adopt a "fluid languaging approach". Even if such a distinction was a real one, from the MTBBE perspective proposed, the so-called different "approaches" might best be regarded as working heuristics that researchers and scholars draw on as needed and therefore their value and appropriateness of each one ought to be judged in relation to insights they provide in specific, concrete projects.

A fundamental and legitimate criticism of the translanguaging perspective is that some of those who use this approach in the context of post-colonial (and post-apartheid) societies need to concede that translanguaging in the way in which it is used by Garcia and Li, in contrast to Cen Williams (see Baker 2003), is grounded in experiences in the United Kingdom and the United States in which minority speakers of non-English languages live in an English-dominant community and that what this approach tries to do is to make visible and include minority languages and groups in the majority culture and language (Heugh 2021). All the while the approach assumes that minority students, in the course of their daily lives, have adequate access to the language of power, English in this case, in the playground, preschool, primary and secondary schooling, and vertical access to the language is assured. In contrast, in post-colonial societies such as South Africa where standard varieties of the high-status ex-colonial language, in particular, are not widely available in the daily activities of most children, deliberate efforts are required to teach and learn home languages and additional languages of power in order for students to succeed in formal schooling. In summary, in this context it is vitally important to be mindful and deliberate in carefully calibrating and mixing vertical and hierarchical (noun-like) and horizontal and fluid (verb-like) dimensions of multilingualism to respond to the specificities of our sociolinguistic environment and pedagogic goals.

Translaguaging perspectives reviewed here focus on practices that go beyond named languages and seek to foster languaging practices that go beyond conventionalised languages; however, it is unclear whether in addition they value the development of language competences in named languages. To be sure, there are other perspectives to translanguaging that take seriously mastery of conventions and values of standard or written languages, for instance, while at the same time creating spaces for students to incorporate into the standard their own "codes" and "values" (e.g., Canagarajah 2011, 23). By implication such approaches work with some notion of language, even if only as a temporarily stable category, along the lines argued by MTBBE.

While there are differences between the perspectives, I believe there is a broad area of overlap, if not actual consensus. All the perspectives regard language as a social rather than a natural construct, even if an "invented" social construct. Because language is socially constructed, languages are shaped and fought over to suit the interests of specific groups and therefore are shot through with ideology. Named languages such as "English" or "Sesotho" do not exist in some absolute way but in this socially constructed and contested way. In the course of everyday communication, multilingual language users often do separate their languages but also use them together in complex and interdependent ways. However, for purposes of formal teaching and learning it is necessary in some contexts and activities to keep languages separate. Named and standard written languages are often very different from how many people who identify as users of those languages actually use language in their daily lives. As a result, it is necessary to decolonise the concept of language as well as colonial forms of knowledge so that both are inclusive and reflective of users. For purposes of formal learning and teaching, it is necessary to work with some notion of a "standard variety"-a flexible, changing, and changeable notion of a standard that recognises and includes rather than eradicating, stigmatising and marginalising other non-dominant rural or urban varieties.

Given that language is a social construct as discussed, it is expected that reasonable people would disagree about whether or not to use and the meanings of terms such as "language planning/management", "mother tongue", "additional/second language", "language transfer", "language proficiency/competence" or "additive bi/multilingualism". However, having reasonable discussion and disagreement about such matters at the minimum requires conceding that language is a dual phenomenon and then specifying and elaborating this duality and its implications in the context of concrete research, policy or practical pedagogical interventions.

The Bi/Multilingual Degree Programme

Genesis

In spite of significant, but inadequate, investments into initial and in-service teacher education over the past two decades, the combined network of public and private providers have not been able, on a mass scale, to produce the kind of teachers with the requisite (English-medium) content and pedagogical knowledge, skills, and attitudes essential to teach for deep learning in the socio-pedagogic context of the vast majority of schools, that is, poor urban and rural schools. The genesis of the bi/multilingual degree programme is a two-pronged critique of the teacher education system and the knowledge project underneath it, summarised in Ramadiro and Porteus (2017, 24-5), as follows:

The first element focuses on the linguistic resources of teachers and learners. The critique is that the knowledge project implicitly works from an English speaking normative social universe and starting points, and does not field test or generate enough research placing African language speaking children and teachers at the centre. As such, our ideas about literacy and mathematics do not build on the language resources of African language speaking children and teachers. The second focuses on social class and its relation to education. The critique is that the knowledge project implicitly works from a more middle-class school context, underestimating the exigencies of the poor and working class, deeply rooted in historic neglect and the marginalisation of communities and schools.

Everything in education cannot be reduced to language, but without language there is no education. The first aspect of the critique claims that the quality of classroom teacher talk and of teacher-led teaching and learning processes is contingent on both mastery of content and proficiency in the language through which the content is encoded. In our education system, many teachers lack both (English-medium) content knowledge and English-language proficiency, which combine to (re)produce classroom cultures of "safe-talk" (Chick 1996; Hornberger and Chick 2001). Safe-talk is characterised by teacher volubility, learner taciturnity, and teaching and learning processes oriented to relatively easier aspects of content, low-order questioning, and face-saving but superficial pedagogical exchanges between teachers and learners. This is a common and normalised phenomenon in poor urban and rural classrooms that conduct teaching and learning in an unfamiliar ex-colonial language (e.g., for South Africa and Tanzania see Desai, Qorro and Brock-Utne [2010], and for Mozambique see Chimbutane [2011]). The default and failed response has been to invest in efforts to improve the English proficiency of teachers and learners in the hope that this would result in better acquisition of English-medium content (Alexander 1999). Given the central role that English plays in our education system and the formal economy, it is important to ensure that everyone has access to good quality English language teaching, but doing so by marginalising or going around African languages is both unnecessary and self-defeating for English-language learning. This is in part because when a learner has learnt to read for meaning in an African language, for example, they do not have to relearn much of the knowledge and skills involved in reading comprehension in English, but can transfer and adapt them to the latter. In the interim, I concur with Joseph and Ramani (2014, 141) that within a framework of a bi/multilingual curriculum

epistemic access to dominant knowledges and dominant languages (such as English) [is] the right of African [language-speaking] students, even at the risk of further entrenching the hegemony of English.

In order to build on the language resources of learners and teachers, the degree programme focused on teaching methods modules in the foundation phase, namely, life skills, mathematics, and home languages, and sought to support trainee teachers to:

• Acquire concepts and discourses used in foundation phase school subjects through the relevant language of teaching and learning (isiXhosa, English or Afrikaans). This is crucial because in the case of African languages such as isiXhosa, when teachers are not formally exposed to and supported to acquire standardised terminology in mathematics, literacy or life skills, each teacher coins their own terminology, which may not be accurate, and precisely because terminology is created on-the-spot, the same teacher or different teachers use different terms for the same concept, resulting in inconsistencies and learner confusion. In turn this inhibits smooth and rapid learner concept development and consolidation within and across grades.

• Be fluent isiXhosa-English or Afrikaans-English bilingual users of concepts and discourses used in foundation phase school subjects. While it might be obvious that trainee teachers in the foundation phase should conduct their teaching practice in the language of teaching and learning, an African language, for instance, prior to the bi/multilingual degree programme, it was common for students to teach in English only in order to accommodate the lecturer's lack of competence in isiXhosa or Afrikaans. I come back to this point later on.

• Take part in efforts to create a variety of quality narrative and informational learner reading materials in isiXhosa. It is not only important to use the language that teachers and leaners are proficient in but also to ensure that African languages are resourced so that they can be effective tools for teaching and learning. It is common knowledge that there is a dearth of learner reading materials in African languages. Especially lacking are non-fiction materials about social sciences, natural science and technology concepts covered in the life skills curriculum. A lack of these materials often means many of these concepts are not taught in African-language foundation phase classrooms, with the consequence that these children enter Grade 4 with enormous knowledge gaps.

The bi/multilingual BEd degree offered at Fort Hare was directly inspired by a pioneering sePedi (or, alternatively, Sesotho sa Leboa) and English dual-medium Bachelor of Arts in Contemporary English and Multilingual Studies degree (BA CEMS) founded by Esther Ramani and Michael Joseph at the University of Limpopo in 2003 (Ramadiro and Sotuku 2011). There were at the time other initiatives where African languages were used as languages of teaching, learning and assessment in one or two modules, but for more than a decade BA CEMS was the only comprehensive response to the call to decolonise the curriculum, intellectualise African languages and use them as languages of teaching, learning and assessment for at least 50% of modules in an accredited undergraduate degree programme.

Apart from learning from the BA CEMS, in 2012 the late Namhla Sotuku and I set up a small network of practitioners and scholars with experience in isiXhosa-English bilingualism and/or bilingual education around the UFH degree programme to support development of the initial curriculum framework and materials for the programme, and much later on some of the members acted as lecturers and guest lecturers, moderators and external examiners for the programme. The network comprised specialists in literacy, isiXhosa and English education, bilingualism, isiXhosa-English bilingual mathematics and science, and a mathematics specialist. This network is remarkable because it is not common in higher education for people from different institutions and organisations to work together to develop a degree programme to be offered at one university. The network comprised Xolisa Guzula (at the time of Nal'ibali and now University of Cape Town, a literacy and bi/multilingual education specialist); Zola Wababa (at the time of the isiXhosa National Lexicography Unit based at the University of Fort Hare and now Eastern Cape Department of Education, an isiXhosa-English bilingual mathematics and science specialist); Sebolelo Mokapela (at the time an isiXhosa language specialist at the National Assembly and now University of the Western Cape); Xolisa Tshongolo (at the time an isiXhosa language specialist at the Western Cape Department of Cultural Affairs and Sports and now the Eastern Cape Pan South African Language Board); the late Chris Giwu (an isiXhosa-English science education specialist at PRAESA and, at the time, a doctoral candidate at the University of the Western Cape); and colleagues from the University of Fort Hare, Namhla Sotuku (a foundation phase and literacy specialist), Noludwe Bambiso (a mathematician and mathematics education specialist) and me (a literacy and bi/multilingual education specialist). This network around bi/multilingualism and others like it, especially bua-lit (bua-lit.org.za) and the Home Language Literacy and Biliteracy Whatsapp group, hosted by Xolisa Guzula, have been an important source of encouragement and support for those of us working in institutions where acceptance and support for bi/multilingual education programmes ebb and flow with changes in faculty and university leadership and where the full ramifications of such programmes are not well-understood, especially with regard to staffing. Under such conditions it is difficult to consolidate gains made, and the gains are in constant danger of reversal or even complete loss.

Curriculum and Language Use

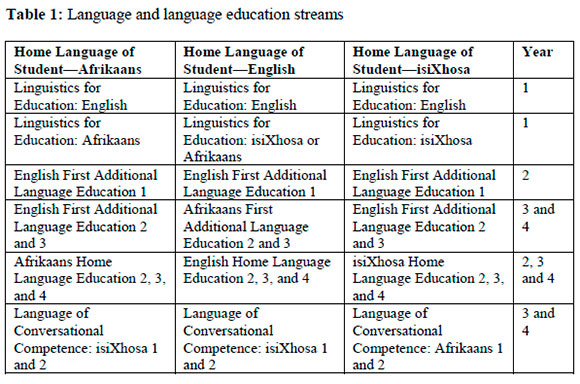

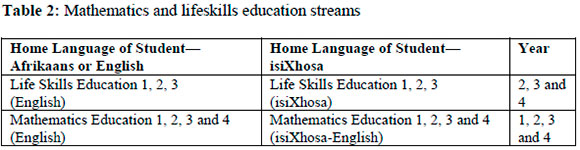

From a curriculum point of view, the degree has five aims: To prepare teacher candidates who can teach a home language, a first additional language, mathematics and life skills content through the home language of the child and who have the ability to use both languages simultaneously when it is needed, not merely in a self-facilitative way, but in a learner-oriented way in order to facilitate deep learning; and, finally, to prepare teachers who value their and others' individual multilingualism and who can communicate in a third language, in addition to their home and first additional languages. See Table 1 and Table 2 for language, life skills and mathematics streams offered in the programme.

It is no occasion to assess the extent to which the curriculum aims were achieved. We can, however, briefly discuss the language ideologies and pedagogic goals apparent in and implied by the aims. These include that there are such things as "standard" (written) languages and that it is important to learn about aspects such as their sociolinguistic dimensions, literatures, and the linguistic principles undergirding them. And while it can be shown that, in some respects, differences between language categories such as "home languages", "additional languages" and "languages of conversational competence" are artificial or arbitrary, overall, these categories do in fact refer to significantly different types of language competences required in school with respect to speaking and listening, and reading and writing. This is partly because many students first encounter, use, and formally learn these languages under different sociolinguistic conditions, and the languages may be significantly linguistically or structurally different, requiring of students different kinds of effort to be considered competent and of lecturers different methodologies to teach them.

The aims of the curriculum might give the impression that language use in teaching and assessment in the programme adhered to strict monolingual norms, but nothing can be further from the truth. In reflecting on the languages of teaching and assessment, I draw on Hornberger's (2003) continua of biliteracy to discuss the multidimensional and multidirectional interrelationships between languages and literacies in the degree. With regard to classroom interaction (the oral language used by students and lecturers in the lecture hall and in online platforms) in the isiXhosa, Afrikaans or English language modules, for instance, interaction would be conducted in the language of learning and teaching (LOLT) on most occasions, and in others, and especially when addressing linguistic and literacy concepts-such as theoretical aspects of phonics-teaching would be conducted simultaneously in isiXhosa and English, or Afrikaans and English. Because much of the theoretical literature on language and literacy is in English, conducting classroom discussion in both isiXhosa and English or Afrikaans and English enabled students to translate and transfer knowledge from one language to another and back, that is, to "translanguage" and "transknowledge" (Heugh 2021), thereby deepening their learning. The language practices described here encompass aspects of perspectives associated with MTBBE (Alexander 2006), decoloniality and teacher education (Abdulatief, Guzula, and McKinney 2021), and translanguaging (Makalela 2019). With respect to isiXhosa, for example, the kind of isiXhosa used in lectures, tutorials and presentations approximates languaging practices that can be described as translanguaging, with students and lecturers spontaneously making and sharing meaning in their own "vernacular" or varieties of isiXhosa such as isiMpondo and isiBhaca.

The ability of students to work across languages is valued and promoted in the programme. However, the primary goal of the programme is not translanguaging per se, but high levels of competence in standard varieties of isiXhosa, Afrikaans and English and in academic content mediated through these varieties, high levels of competence in additional languages and basic communication skills in another language. Students are required to make oral and written presentations and materials predominantly in standard varieties and, on planned occasions, in their own local variety of a given standard variety, and in some cases, to produce materials bi/multilingually in the language repertoires available to them. All of this reflects language ideologies informing the programme, the current language requirements of teacher education programmes in the country, as well the competencies of students and teaching staff. Many of the language practices described here may well fall in the "fixed language approach" category proposed by Bonacina-Pugh, da Costa Cabral and Huang (2021), but some of them can best be described as examples of the "flexible languaging approach". In the specific case of this programme, the two "approaches" coexist, albeit in an uneven combination.

Stubborn Challenges to Implementing Bi/Multilingual Education

The bi/multilingual BEd degree faces many challenges and many of them are not unique to it but in fact echo challenges faced by the BA CEMS degree offered at the University of Limpopo. This suggests that the dynamics behind these challenges are structural and reflective of the power matrix in which African languages are embedded and which enable and disable them. Nearly 20 years ago, Ramani and Joseph (2006, 15) identified the following set of challenges hindering the sustainability of the BA CEMS degree programme, which also resonate with my own experience:

• Shortage of materials

• Staffing

• Territorialism

• Resistance of historically black universities to African languages

High quality materials development is expensive. It requires collaboration between specialists in the relevant academic content, language specialists, editors and lay-out professionals. Poorer universities often do not have the funds to support this work. The three languages used in the programme were not equally affected by this challenge. The English home language stream in particular and Afrikaans drew, to a great extent, on longer traditions of using these languages in teacher education. In relation to using isiXhosa to teach language and literacy, much progress was made. For example, we were fortunate to receive external funding to develop materials prior to commencement of the programme (such as a European Union and Department of Higher Education and Training grant to develop a widely circulated isiXhosa-English bilingual language and literacy glossary) (Ramadiro 2016), and once the programme started, the isiXhosa language and literacy stream received support from the intervention-research work of the Nelson Mandela Institute for Education and Rural Development based at the University of Fort Hare (such as a detailed isiXhosa-English bilingual phonics teacher guide that is based on the orthography of isiXhosa) (Ramadiro 2018). Materials development for mathematics and life skills education proceeded at a much slower pace, undermining the stated goal to undergird the acquisition of discipline-specific concepts, registers, discourses, knowledge and skills through isiXhosa.

There are recent efforts by the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) to strengthen African language departments and faculties of education to teach effectively literacy in African languages, for example, by supporting programme development and recruitment and funding of postgraduate studies for prospective junior staff to teach and research African languages (DHET 2020). Notwithstanding this, the overall number of African language specialists in higher education remains low, and there are even fewer people who have the knowledge, skills and experience to work at the interface of African languages, multilingualism, literacy and pedagogy.

The traditional disciplinary organisation of universities, while useful, can also exacerbate "territorialism", the sense that others are trampling on one's "own" turf, leading to reluctance to collaborate and unhealthy competition within and across faculties. Multilingual education by definition requires bringing together knowledge and skills cutting across intra- and trans-faculty specialisms. This is essential for success, but it is difficult in practice to establish cultures of collaboration within and across faculties in universities where academics do not have the time, mental space and energy to cooperate because of understaffing and large teaching loads. Collaboration requires a shared vision; a shared vision requires a shared language to talk about it, which in turn requires mutual trust, all of which need a great deal of time and patience to nurture and grow.

"Resistance" to African languages is not isolated, of course, to historically black universities. It is remarkable and paradoxical, however, that there should be significant resistance to African languages in these institutions because the (reasonable) expectation is that they ought to be the natural homes for the promotion and intellectualisation of African languages, especially given that the maj ority of the student body is made up of African language-speaking students. I have witnessed different forms of aversion to using African languages as LOLTs at the university on a continuum from ignorance to actual resistance. There are colleagues in faculties of education around the country who simply do not make the connection between language proficiency and the ability to learn. Although they are probably a diminishing minority, they do exist. To them language is invisible or at best they take it for granted that students have an equal opportunity to acquire English and especially high levels of academic literacy in this language, and that when a student is not proficient, this is regarded largely as an individual failing, relegated to be addressed through language and academic literacy remediation. The result is that English monolingual dominance as a LOLT after Grade 3 is left unchecked.

On the next point on the continuum of resistance are probably the vast majority of colleagues who are aware of the potential benefits of using African languages as LOLTs, either on their own or along with English or Afrikaans, but who are concerned about possible but unintended social and political repercussions of doing so. The principal objections associated with this position are that use of African languages may reinforce apartheid-era language-based "tribal" identities and thereby weaken solidarity among African or black people more generally. Another objection, often raised as a question is: "Doesn't use of African languages complicate student learning, requiring them to work across two or more languages simultaneously?" An implied query is: "Isn't it just easier to work with English only?" The short answer is that is exactly what we have been trying to do as a country for decades and we are failing at it. Alexander's (1999) conclusion that an English-only education system in South Africa, while it may be "unassailable" on paper, is in practice "unattainable" is valid even today. Our country has not been and is not able to train, at scale, English-proficient teachers who can teach to a high level African language-speaking primary and secondary school children, and it has not created a post-schooling system in which the vast majority of African language-speaking students can succeed through an English-only LOLT.

At an extreme end of the continuum are colleagues who completely object to the use of African languages as LOLTs. Since Ramani and Joseph's (2006) article, this group has probably become quite small and less vocal, certainly in my institution. This is mainly because public and governmental attitudes to the use of African languages beyond the early grades of schooling have changed, and this is partly expressed in the promulgation of a series of policies aimed at guiding language use and in particular supporting the use of African languages in higher education (DHET 2015, 2020; MoE 2002). The use of African languages in higher education, although quite limited at the moment, is beginning to have the intended backwash effect on lower levels of the education system, with graduating high school students, for example, specifically wanting to enrol for their BEd degree in foundation phase teaching at the University of Fort Hare precisely because it is offered bi/multilingually with an African language at the core. Many objections of this group are similar to those made by the other groups, and in addition, this group stresses two points: first, that English is the dominant language of science and scholarship and all students should be supported to be proficient in this language; and second, that the costs of using all African languages are too prohibitive and, in any case, unnecessary, and the whole enterprise is probably doomed because government is unlikely to make the investments needed to use African languages as LOLTs at a significant scale. The upshot is the dominance of English, the reproduction of language-based educational inequality and solidifying "elite closure" (reinforcing the power and privileges of elites through language choices that serve them) (Myers-Scotton 1993).

Conclusion

In light of the experience of the bi/multilingual degree, I summarise key lessons for implementing bi/multilingual education in which an African language plays a major role in the post-schooling and training sector in the hope that practice clarifies and informs theory. First, "cross-institutional" and "trans-institutional" collaboration (DHET 2015) is essential because it is unlikely that one institution can have all the knowledge, skills and experience needed to implement African language-based bi/multilingual programmes. Second, and just as important, but much more difficult to achieve, is "intra-institutional" collaboration. Both the BA CEMS and BEd degree experience testifies to this. This makes trans-institutional collaborations even more important. Third, it is important to keep in mind that it is not necessary to take a maximalist position to the use of African languages. While using these language as full LOLTs is at one end of a continuum, a range of other practices are possible that can both affirm learner identities as well as enable deep learning, including encouraging students to use African languages for discussions and oral presentations in tutorials and lectures, for their own note-taking, and translating between languages as a learning strategy. In other words, students should be encouraged and supported to use all their linguistic repertoires to learn even when the teacher or lecturer does not have or only has partial access to their repertoires. Fourth, there is increasing support for bi/multilingualism and use of African languages in higher education. A recent example is the Department of Higher Education and Training and European Union programme funding the creation of centres for teaching of African languages in faculties of education. However, the field remains grossly underfunded and under-capacitated and therefore the stated policy goals of raising the status of and intellectualising African languages and providing epistemic access for all students (Pluddemann, Nomlomo, and Jabe 2010) remain out of reach. Finally, even though there is clear policy framework promoting bi/multilingualism and the use of African languages in post-schooling, the ideological and pedagogical project underneath it is not well-understood inside higher education, and it is fragile. This is not in the least helped by African language purists who, as the Nguni linguist Themba Msimang (1998, 168) observed, you can always bet on to kill the language. In that situation there is a need to conduct constant advocacy for African languages and multilingualism, and to link up with and forge collaborative networks inside and outside institutions of higher learning.

References

Abdulatief, S., X. Guzula, and C. McKinney. 2021. "Delinking from Colonial Language Ideologies: Creating Third Spaces in Teacher Education". In Language andDecoloniality in Higher Education: Reclaiming Voices from the South, edited by Z. Bock and C. Stroud, 135-58. London: Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350049109.ch-007. [ Links ]

Alexander, N. 1999. "English Unassailable But Unattainable: The Dilemma of Language Policy in Education in South Africa". PRAESA Occasional Papers, No. 3. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.marxists.org/archive/alexander/1999-english-unassailable.pdf. [ Links ]

Alexander, N. 2006. "The Experience of Mother Tongue-Based Education in Post-Colonial Africa, with Special Reference to South Africa". Input Memo prepared for the Language Colloquium, National Department of Education, Cullinan Hotel, Cape Town, July 31, 2006.

Alexander, N. 2013. Thoughts on the New South Africa. Johannesburg: Jacana. [ Links ]

Alexander, N. 2014. Interviews with Neville Alexander: The Power of Languages against the Language of Power. Edited by B. Busch, L. Busch, and K. Press. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

Baker, C. 2003. "Biliteracy and Transliteracy in Wales: Language Planning and the Welsh National Curriculum". In Continua of Biliteracy: An Ecological Framework for Educational Policy, Research and Practice in Multilingual Settings, edited by N. H. Hornberger, 71-90. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853596568-007. [ Links ]

Bonacina-Pugh, F., I. da Costa Cabral, and J. Huang. 2021. "Translanguaging in Education". Language Teaching 54 (4): 439-71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444821000173. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Canagarajah, S. 2011. "Translanguaging in the Classroom: Emerging Issues for Research and Pedagogy". Applied Linguistics Review 2: 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1515/978311023933L1. [ Links ]

Chick, J. K. 1996. "Safetalk: Collusion in Apartheid Education". In Society and the Language Classroom, edited by H. Coleman, 21-39. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Chimbutane, F. 2011. Rethinking Bilingual Education in Postcolonial Contexts. Bristol: Multingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847693655. [ Links ]

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2015. Report on the Use of African Languages as Mediums of Instruction in Higher Education. Pretoria: Government Printers. Accessed September 20, 2022. https://www.dhet.gov.za/Policy%20and%20Development%20Support/African%20Langauges%20report_2015.pdf. [ Links ]

DHET (Department of Higher Education and Training). 2020. Language Policy Framework for Public Higher Education Institutions. Pretoria: Government Printers. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202011/43860gon1160.pdf. [ Links ]

Desai, Z., M. Qorro, and B. Brock-Utne, eds. 2010. Education Challenges in Multilingual Societies: LOITASA Phase Two Research. Cape Town: AfricanMinds. [ Links ]

Garcia, O., and W. Li. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Heugh, K. 2021. "Southern Multilingualisms, Translanguaging and Transknowledging in Inclusive and Sustainable Education". In Language and the Sustainable Development Goals, edited by P. Harding-Esch with H. Coleman, 37-47. London: British Council. [ Links ]

Hornberger, N. H. 2003. "Continua of Biliteracy". In Continua of Biliteracy: An Ecological Framework for Educational Policy, Research and Practice in Multilingual Settings, edited by N. H. Hornberger, 1 -34. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853596568. [ Links ]

Hornberger, N., and J. K. Chick. 2001. "Co-Constructing School Safetime: Safetalk Practices in Peruvian and South African Classrooms". In Voices of Authority: Education and Linguistic Difference, edited by M. Heller and M. Martin-Jones, 31-55. London: Ablex Publishing. [ Links ]

Joseph, M., and E. Ramani. 2014. "Marginalised Knowledges and Marginalised Languages for Epistemic Access to Piaget and Vygotsky's Theories". In Educating for Language and Literacy Diversity, edited by M. Prinsloo and C. Stroud, 137-52. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/97811373098607. [ Links ]

Li, W. 2011. "Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain". Journal of Pragmatics 43 (5): 122235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035. [ Links ]

Li, W., and A. M. Y. Lin. 2019. "Translanguaging Classroom Discourse: Pushing Limits, Breaking Boundaries". In "Translanguaging Classroom Discourse", edited by W. Li and A. M. Y. Lin, special issue, Classroom Discourse 10 (3-4): 209-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2019.1635032. [ Links ]

Lin, A. 2013. "Classroom Code-Switching: Three Decades of Research". Applied Linguistics Review 4 (1): 195-218. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2013-0009. [ Links ]

Makalela, L. 2019. "Uncovering the Universals of Ubuntu Translanguaging in Classroom Discourse". In "Translanguaging Classroom Discourse", edited by W. Li and A. M. Y Lin, special issue, Classroom Discourse 10: (3-4): 237-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2019.1631198. [ Links ]

Makoni, S., and P. Mashiri. 2007. "Critical Historiography: Does Language Planning in Africa Need a Construct of Language as Part of Its Theoretical Apparatus?" In Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages, edited by S. Makoni and A. Pennycook, 62-89. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853599255-005. [ Links ]

Makoni, S., and A. Pennycook. 2007. "Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages". In Disinveting and Reconstituting Languages, edited by S. Makoni and A. Pennycook, 1 -41. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853599255-003. [ Links ]

Martin-Jones, M. 1995. "Codeswitching in the Classroom: Two Decades of Research". In One Speaker, Two Languages: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Code-Switching, edited by L. Milroy and P. Muysken, 90-111. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511620867.005. [ Links ]

Martin-Jones, M. 2000. "Bilingual Classroom Interaction: A Review of Recent Research". Language Teaching 33 (1): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800015123. [ Links ]

McKinney, C. 2016. Language and Power in Post-Colonial Schooling: Ideologies in Practice. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315730646. [ Links ]

McKinney, C., and P. Christie. 2022. "Introduction: Conversations with Teacher Educators in Coloniality". In Decoloniality, Language and Literacy, edited by C. McKinney and P. Christie, 1-20. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929257-004. [ Links ]

Menezes de Souza, L. M. T. 2021. Foreword to Language and Decoloniality in Higher Education: Reclaiming Voices from the South, edited by Z. Bock and C. Stroud, ix-xix. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [ Links ]

Mercer, N. 1995. The Guided Construction of Knowledge: Talk amongst Teachers and Learners. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Mignolo, W. 2013. "On Pluriversality". Accessed August 5, 2022. http://waltermignolo.com/on-pluriversality/.

MoE (Ministry of Education). 2002. Language Policy for Higher Education. Pretoria: Government Printer. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/langpolicy0.pdf. [ Links ]

Msimang, T. 1998. "The Nature and History of Harmonisation of South African Languages". In Between Distinction and Extinction: The Harmonisation and Standardisation of African Languages, edited by K. Prah, 165-72. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand Press. [ Links ]

Myers-Scotton, C. 1993. "Elite Closure as a Powerful Language Strategy: The African Case". International Journal of the Sociology of Language 103: 149-63. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.1993.103.149. [ Links ]

Obanya, P. 2004. "Learning in, with and from the First Language". PRAESA Occasional Papers No. 19. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. Accessed September 6, 2022. http://www.praesa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Paper19.pdf. [ Links ]

Pluddemann, P., V. Nomlomo, and N. Jabe. 2010. "Using African Languages for Teaching Education". Alternation 17 (1): 72-91. [ Links ]

Ramadiro, B. 2016. IsiXhosa English Language and Literacy Glossary. East London: Magic Classroom Collective Press. [ Links ]

Ramadiro, B. 2018. IsiXhosa Phonics Teacher Guide. East London: Magic Classroom Collective Press. [ Links ]

Ramadiro, B., and K. Porteus. 2017. Foundation Phase Matters: Language and Learning in South African Rural Classrooms. East London: Magic Classroom Collective Press. [ Links ]

Ramadiro, B., and N. Sotuku. 2011. "Lessons from the University of Limpopo' s Dual Medium Degree". Bilingual B.Ed Project Bulletin No. 1, June 2011. East London: University of Fort Hare. [ Links ]

Ramani, E., and M. Joseph. 2006. "The Dual-Medium BA Degree in English and Sesotho sa Leboa at the University of Limpopo: Success and Challenges". In Focus on Fresh Data on the Language of Instruction Debate in Tanzania and South Africa, edited by B. Brock-Utne, Z. Desai and M. Qorro, 4-18. Cape Town: Creative Minds. [ Links ]

Thibault, P. J. 2011. "First-Order Languaging Dynamics and Second-Order Language: The Distributed Language View". Ecological Psychology 23 (3): 210-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10407413.2011.591274. [ Links ]

Van der Berg, S., and M. Gustafsson. 2019. "Educational Outcomes in Post-Apartheid South Africa: Signs of Progress Despite Great Inequality". In South African Schooling: The Enigma of Inequality, edited by N. Spaull and J. D. Jansen, 25-45. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18811-5_2. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, C. 2013. Multilingual Higher Education: Beyond English Medium Orientations. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847699206. [ Links ]