Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.24 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/7994

ARTICLE

School Governance and Social Justice in South Africa: A Review of Research from 1996 to 2016

Pontso MoorosiI; Itumeleng MolaleII; Bongani BantwiniIII; Nolutho DikoIV

IUniversity of Warwick, United Kingdom, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. p.c.moorosi@warwick.ac.uk; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4447-4684

IINorth-West University, South Africa. Itumeleng.Molale@nwu.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3596-7425

IIIWalter Sisulu University, South Africa. bongani.bantwini@gmail.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4053-3453

IVWalter Sisulu University, South Africa. nndiko@gmail.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3105-8630

ABSTRACT

In this article, we conduct a systematic review of school governance literature in order to examine the influence of the social justice agenda in South Africa between 1996 and 2016. The review explores the nature and scope of school governance research, the methodologies used as well as the theoretical constructs underpinning the research in the identified period. We used search words related to school governance to identify electronically published academic material. By way of analysis, we employed a combination of descriptive quantitative and qualitative forms of systematic review. The findings reveal a relatively small body of research spread across local and international journals that mostly investigates issues around democratic participation and representation. Although redressing the education system was viewed as one of the major catalysts in restoring the values necessary for a socially just and democratic society, school governance research is not underpinned by the analysis of social justice. We conclude by reflecting on limitations and making suggestions for future research.

Keywords: school; governance; research; governing bodies; social justice

Introduction

We1 provide a systematic review of literature on school governance examining the extent to which this literature has been influenced by the social justice framework from 1996 to 2016. Traditionally, school governance operates as a subtopic within the broader field of educational management, administration, leadership (and governance) literature. Consequently, a great deal of school governance research goes unnoticed, hidden under the banner of the broader field, while the work of school governing bodies is overlooked (Balarin et al. 2008). In South Africa, school governance research gained researchers' significant attention after the establishment of post-apartheid legislation, the South African Schools Act (SASA), Act No. 84 of 1996, which mandated democratic participation of stakeholder groups in local decision-making (RSA 1996a). However, the extent of this research and the degree to which it has been influenced by social justice are not known. A concerted effort to consolidate knowledge in school governance research was deemed a necessity, so that research can address existing theoretical gaps.

Our conceptualisation of school governance is informed by existing research that includes school governing bodies and the work they do as school governors as mandated by school governance policy (SASA) in the South African context. Kooiman (2003) argues that conceptual clarity between "governance" and "governing" should be provided. He defined governing as a "totality of interactions in which public as well as private actors participate, aimed at solving societal problems or creating societal opportunities" (RSA 1996a, 4), while governance is the "totality of theoretical conceptions of governing". Influenced by Kooiman (2003), it perhaps follows that James, Brammer, and Fertig (2011) made a distinction between school governing and school governance, arguing that "school governance" is a broader concept involving several non-government actors who have "shared interests in public policymaking and implementation" (2011, 394) within the education system. In this conceptualisation, school governing is but one component of school governance, which is usually performed by "first order"2 school governors, whose "responsibility is to deal with the day-to-day affairs of school governance" (James, Brammer, and Fertig 2011, 394). We understand school governing as a subset of school governance, and we use school governance to accommodate all aspects that concern governors and governing within the schooling system.

This review is framed within the first two decades of democratic rule that saw the unification of the South African education sector under one system. Prior to this, the apartheid dispensation had divided education along racial, ethnic and regional lines (Motala and Pampallis 2005) and into different departments whose unequal funding left lasting inequalities between blacks and whites. In its response to address the inequalities created by the apartheid system, the democratic government ushered in a series of policies that were focused primarily on "redress, equity, quality and democratic participation" (Motala and Pampallis 2005, 23). Of direct significance and relevance to this review, the South African Schools Act of 1996 (RSA 1996a) provided for democratic governance of schools and targeted redress to bridge the inequalities. The Act of 1996 was intended to provide a "uniform system for the organisation, governance and funding of schools; to amend and repeal certain laws relating to schools; and to provide for matters connected therewith" (RSA 1996a, 1). In view of the inundation of policies brought about by the new dispensation and the ensuing influx of research on educational policy since 1994, we assumed that there would be a significant corpus of research on school governance that would be ready for review (Hallinger 2018). We wanted to examine the kinds of issues that have been pursued in school governance research, how they have been pursued and the extent to which this research is informed by the social justice agenda.

To guide our investigation and develop a systematic discussion, we drew from previous reviews (e.g. Bush and Glover 2016; Hallinger 2014; 2018; Hallinger and Chen 2015) and identified a set of questions. We found Hallinger's (2014) framework for conducting reviews, which suggests a set of questions to guide the review, particularly useful. Our overarching question was: "What is the nature and scope of school governance research published between 1996 and 2016 in South Africa and to what extent is this body of research influenced by the social justice agenda?" To develop a discussion for this review, we identified the following specific questions that guided our analysis:

• What are the volume and distribution of published school governance research?

• What key topics and theoretical constructs underpinned this research?

• What methodological preferences influenced this research?

• To what extent is this body of research influenced by the social justice agenda?

This analysis is expected to make contributions to the literature in three ways: first, by bringing to the fore some key issues that have received research attention and those that have not, we would be highlighting areas in which more knowledge is needed for the benefit of further research. Hallinger (2014) posits that research reviews are critical in providing an understanding of theoretical advances within a particular field while laying a foundation for future knowledge production. Research reviews, thus, "map trends in theory development, methodological applications, and substantive findings to identify productive directions for future research" (Hallinger 2014, 540). Second, we believe that by investigating predominantly used methodologies and theoretical topics covered in school governance research thus far, thereby indirectly exposing the neglected areas, we are facilitating future empirical research. In this regard, we borrow and draw support from Hallinger and Chen (2015) who state that research reviews "provide a signpost on the path of intellectual development" (2015, 6). Third, by using a framework for school governance research underpinned by principles of social justice, we are advocating a research agenda that provides a useful lens to analysing research in school governance, thereby highlighting the social and structural forces perpetuating inequality in social systems and in social relationships. Collectively, these three ways contribute to the use of different frameworks and methods for analyses in school governance research and in the broader field.

This introduction is followed by a historical overview of school governance in South Africa, after which we outline the methodology adopted in this review. We then present and discuss the findings of the review, its limitations and offer a conclusion.

The History of School Governance Policy and Research in South Africa

In this section we provide an overview of school governance policy and research in South Africa. We map and contextualise this within the international landscape, highlighting the different historical moments of school governance policy in other contexts as they influenced trends in school governance research globally.

In terms of the UNESCO (2009) agenda of school governance reform, the South African model has been heralded as one of the most radically reformed (Crouch and Winkler 2008). An extensive account of the history of school governance policy in South Africa is provided in detail in the research of, for example, Motala and Pampallis (2005), Dieltiens (2005) and Sayed and Ahmed (2008), and will not be fully reproduced here. However, it is essential in setting the scene for this review to note that since 1994 in South Africa, school governance has been central to the broader education agenda of open access, equity, democracy and redress, and particularly the transformation of the education system (Motala and Pampallis 2005). As a school governance reform initiative, and of particular relevance to this review, the SASA of 1996 makes provision for the devolution of power from the central to the local (school) level, giving school governing bodies (SGBs) considerable powers on local policy oversight in improving the quality of education. In particular, the SASA promulgates the establishment of school governing bodies whose role includes budgeting, maintenance, application of policy and power over employment of teaching and non-teaching staff. It is in addressing these aspects of school governing that the first governing bodies were elected in 1997, with subsequent elections held every three years since.

It is well known that school governance policy as a reform initiative in South Africa has been driven by the SASA of 1996, under the broader political agenda of transformation and redress driven by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996b). In this context, the political motive for democratic governance of schools was initiated by the need to provide broad-based participation at the local level, which was deemed essential for the process of transformation (Dieltiens 2005). This broad-based participation was in line with the UNESCO agenda of school governance reform. Naidoo (2005) argues that the post-apartheid legislation envisioned particular notions of participation and democratisation to inform processes of decentralisation and local school governance. In this sense, decentralisation was associated with greater participation of stakeholders (parents, teachers, school-based staff and learners) in local governance in schools that would promote greater democracy, citizenship, equity and quality in education (Motala and Pampallis 2005; Naidoo 2005). While giving people a voice in the democratic structures might suggest empowerment, we are quite aware that policy does not mandate what matters most, because what happens in schools is less related to the intentions of policy makers than to the knowledge, beliefs, resources, leadership and motivations that operate in local contexts (Darling-Hammond 1998). This implies that the democratisation of the school system does not necessarily correlate with the effectiveness of a policy or programme. As Naidoo (2005) argues, such policy ideals are often sabotaged by, among others, contextual realities, as schools are distinctive and are placed in different geographical locations faced with a barrage of different challenges and characteristics. Hence, implementation rarely happens as planned. Indeed, as Naidoo (2005) further points out, although the common driving agenda for school governance policy was transformation, the apartheid legacy of racial inequality was bound to have a significant influence on the implementation of policy, in view of its inherent inequalities. Hence, the necessity for a socially just reform.

Since the SASA's inception, and the election of the first school governing bodies in 1997, studies have been conducted on the roles, functions and effectiveness of these (Bayat, Louw, and Rena 2014; Clase, Kok, and Van Der Merwe 2007; Mncube and Naicker 2011; Nwosu and Chukwuere 2017). A decade after the inception of the SASA, Motala and Pampallis's (2005) review of literature on aspects of governance including democratic governance and equity suggested a paucity of school governance research. Most recently, a review of the literature on educational leadership and management was conducted to commemorate the 20-year anniversary of the democratic dispensation (Bush and Glover 2016), and to assess the nature of research on school leadership and management. Notably, Bush and Glover's (2016) review of research on school leadership and management addresses school governance as an aspect of school leadership and management, and reveals a trend in the uneasy relationships between school governing bodies and school principals. Perhaps the uneasy relationship is caused by the knowledge gap between the two organs, the management of resources at school level and the fact that the most radical school governance reform policy has been placed in the hands of school governing bodies "as an important part of grassroots democracy" (Bush and Glover 2016, 217). However, in appreciating the importance of grassroots democracy it is critical to note that democracy cannot be easily nurtured and developed without relevant and appropriate education.

A gap exists in the knowledge generated by school governance research. In a recent review of leadership and management literature in Africa, Hallinger (2018) found that school governance research accounted for only 11% of the overall published literature of more than 500 articles. Encouragingly, Hallinger identified changes in school governance as an area ripe enough to warrant a systematic review. In a previous review, Hallinger and Chen (2015) found that school governance research accounted for 36% of the leadership and management literature in Asia. Hence, we believed that reviewing a body of research on school governance in South Africa would help illuminate theoretical gaps that might provide useful knowledge for the improvement of policy and practice.

School Governance and Social Justice

In view of the injustices of the apartheid past and the continuing inequalities in South African education, a social justice lens was necessary in conducting this review. We acknowledge that social justice may not have a universally accepted definition due to its complexity (Connell 2012). Our understanding of social justice is informed by works of Cochran-Smith (2004) and Carlisle, Jackson, and George (2006) whose framing of social justice suggests a process of understanding how social forces, structures and institutions support equity across different social identity groups. This includes how policy, practice and research can be used to liberate and provide equity-informed solutions and how social forces promote equal social relationships (Carlisle, Jackson, and George 2006; Cochran-Smith 2004). Social justice is a preferred framework for understanding the South African context because of its broad sense in dealing with injustices. Cochran-Smith's (2004) work is based on teacher education for social justice, but it helps us in understanding the significance of community-wide inquiry that facilitates the unlearning of problematic discourses of racism, sexism and other forms of prejudice.

Carlisle, Jackson and George (2006) identified principles that we found useful in making sense of the social justice agenda in school governance research in South Africa. These principles include equity and inclusion, relationships to wider community as well as efforts to provide high quality education for students of all backgrounds. These principles are broad and are seen in line with the framework that drives transformation and redress in post-apartheid South Africa. They align with the broader distributional and relational dimensions of social justice, as Connell (2012) confirmed that social justice in education concerns equality in the distribution of educational services as well as the nature of the service itself "and its consequences for society through time" (681). Central to the distribution of educational services is the role of school governance with its responsibility for democratic participation and representation. Nandy (2012) suggests that a socially just education system recognises "that what happens outside the classroom matters as much as what happens in it" (2012, 678).

The SASA gives school managers and governors a direct mandate on the provision of quality education, and a fair and just education system that ensures equity and inclusion for all children from different backgrounds. This makes social justice particularly complex in the South African context, given the old race-based forms of inequity of the apartheid era that are being perpetuated through the new class-based forms of inequity of the post-apartheid dispensation. Indeed, Connell (2012) acknowledges that the mechanisms of inequality change over time, which explains why racial exclusions of the colonial era have been replaced by class privileges and inequalities of the post-colonial regime. The dimension of social justice relevant in this analysis is a holistic one that takes into consideration all forms of inequality and recognises principles of democratic participation, representation, inclusion and equity. These principles are espoused in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa and inform school governance policy. Indeed, Griffiths (2012) contends that if schools are to be "good places to live" (2012, 233), social justice is not a choice those in education can afford not to make, whether they describe what they do in terms of social justice or not. We were interested in examining the extent to which school governance research has thus far been used to challenge the patterns of social exclusion and oppression, and how it encourages a dialogue that nurtures a socially just education system.

Methodology

The article employs a systematic review of existing academic literature on school governance in South Africa published in the country and internationally between 1996 and 2016. Hallinger (2014) argues that there is no single correct approach to determining the suitability of the period of review. However, for us, the chosen period has political significance in that it signalled 20 years of democratic rule and 20 years of school governance policy (RSA 1996a), providing a legitimate rationale for this review. Our search procedure was "bounded" within the identified time frame as well as by other delimitations that are explicitly identified in this review. Hallinger (2014) identifies three types of search procedure: "selective", "bounded" and "exhaustive" (546). We could not possibly claim an exhaustive search due to our delimitation criteria that focused on electronically available material, while the same criteria and the effort put into the search ruled out a selective search. Our search fits the description of a bounded review as it "answers a defined research question by collecting and summarising all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria" (Hallinger 2014, 546), thereby making our criteria explicit and defensible. Hallinger (2014, 542) outlines at least three ways in which a systematic review differs from a traditional literature review:

• it uses explicit and transparent methods

• it follows a standard set of stages and these are

• accountable, replicable and updateable

Accordingly, we limited the research to articles in peer-reviewed academic journals published after the establishment of the South African Schools Act of 1996 (RSA 1996a). We explicitly identified electronic material to be analysed using an initial search through Google Scholar and the library database. As part of our delimitation criteria, we wanted to focus on material that has been subjected to the scrutiny of peer-review that could be accessed electronically. We excluded theses and dissertations, books and book chapters, as well as government and other research reports not published in peer-reviewed journals. Search words and phrases such as school governance, school governing bodies, governors, educator governors, learner representative councils, democratisation in schools, representation and participation were used. Narrowing the search down to just school governance literature published in peer-reviewed academic journals from 1996 to 2016 gave us a total of 56 articles. We were disappointed with the outcome, as we had expected more. However, it is worth mentioning that some South African journals were not yet available electronically at the time. Although we were disappointed by this outcome, previous reviews (e.g. Hallinger 2014; Leithwood and Jantzi 2005; Leithwood and Sun 2012) suggest that this was a reasonable number of articles for a systematic review. Hallinger (2014) reviewed 38 exemplary review articles; Leithwood and Sun (2012) conducted a meta-analysis of 79 unpublished studies while Leithwood and Jantzi (2005) reviewed 32 articles on transformational leadership. All these reviews, and many more, constitute exemplary reviews that were all published in reputable journals and have been cited repeatedly.

Data Analysis

By way of data analysis, we scanned and extracted from each of the 56 articles specific data on the authors, year of publication, journal, the title and focus of the article, methods employed, main findings and summary of conclusions. In performing this data extraction, we were informed by previous research reviews and, in particular, Hallinger and Chen (2015) and Hallinger (2014) who explain clear processes of data extraction and analysis for systematic research reviews. A clear data extraction and data treatment procedure is a hallmark of a systematic review (Hallinger 2014). We then entered these data into an Excel spreadsheet from which we further generated tables and graphs that we used to represent data quantitatively. Descriptive statistical analysis was used to analyse the data quantitatively to determine frequencies and distribution of publications. The results were represented using tables and graphs that illustrate trends and foci over time.

Results

In this section we present the results of our analysis. We do this around the broad questions guiding this review, using them as subheadings and tackling each question in turn. We follow Hallinger (2014) in treating the questions guiding this analysis as part of the conceptual framework around which the key ideas or findings are organised.

What Are the Volume and Distribution of School Governance Research?

In answering the broader question on the nature and extent of publications, we started by examining the rate as well as pattern of publications on school governance. By rate of research, we mean the volume of articles published within the identified period and how this changed over the years. Patterns of publication revealed where the articles were published, whether in local or international journals as well as which journals published the biggest volume of school governance articles. Hallinger (2014) suggests that reviews of research are always undertaken in response to a perceived problem. In our case, our analysis was based on the assumption that there was a huge body of research on school governance that needed acknowledging and examining so that gaps could be identified for further and more informed research. This section presents findings on the rate and patterns of publication of research on school governance.

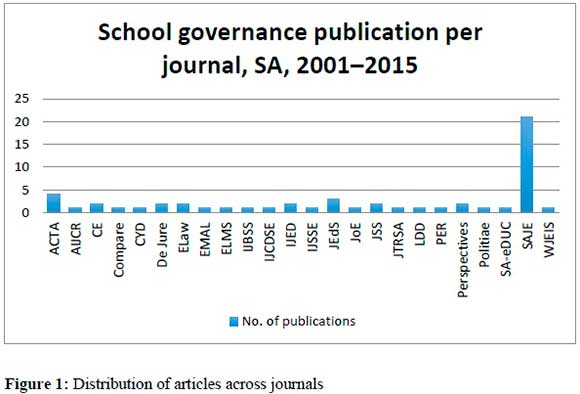

Publications by Journals

As already suggested, our analysis was limited to academic articles published in peer-reviewed journals. We found 56 journal articles that fit our selection criteria published between 2000 and 2016, which we regarded as a very small number of articles in school governance research. Although the review itself aimed to find articles published from 1996, we found no publications (within our selection criteria) between 1996 and 2000, except for some research reports, dissertations and theses, which did not form part of the analysis. We found that 46 (83%) of the articles were published in national journals and 10 (17%) were published internationally. The diagram below (Figure 1) illustrates the distribution of articles across the journals. Of the 46 locally published articles, 21 (45.6%) of them were published in one journal-the South African Journal of Education (SAJE). The rest of the articles were spread across the different journals, which published between one and four articles in the case of Acta Academia.

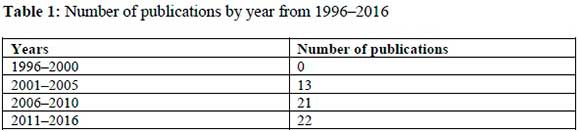

Publications by Year

We were also keen to examine the growth pattern of publications by year. Table 1 below illustrates the number of publications by year group. We note that there was a steady increase of publications in the SAJE between 2003 and 2010 and a decline after that, with only one publication in 2011, one in 2012 and one in 2016. This is an interesting pattern given that there was a general increase of publications (in other journals) after 2011, with the period between 2011 to 2016 having the highest number of publications. The period between 2011 and 2016 saw the highest volume of publications: 22 publications and a total of nine in 2011 alone and seven in 2013. However, the other years saw fewer publications, with one publication in 2012, 2014 and 2016 and three in 2015. A breakdown between the two decades shows the highest volume of publications was in the second decade, with a total of 43 between 2006 and 2016.

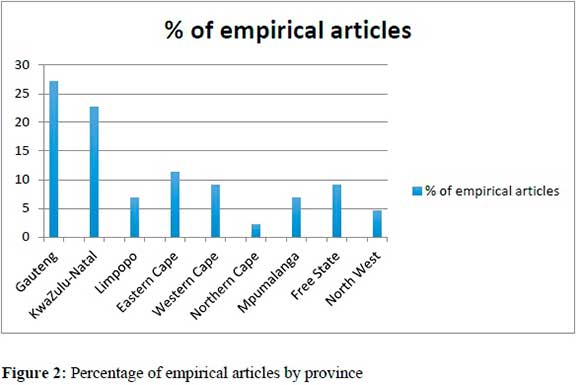

Publications by Province

We were also interested in knowing how research was spread across the provinces and there were some interesting patterns of knowledge production by province, as shown in Figure 2 below. Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal provinces had the highest number of publications at 27.2% and 22.7% respectively, collectively accounting for 50% of all empirical publications. They were followed by the Eastern Cape at 11%, with the Free State and Western Cape sharing fourth place at 9.09%. Given that there are more universities, and therefore more researchers, in Gauteng than in any other province, we were not surprised by the Gauteng province accounting for most of the publications based on empirical research. We also noticed that two of the biggest provinces in terms of number of schools and learners (KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape) were in the top group of provinces accounting for a higher concentration of publications, which could suggest more research activity in these provinces. The Northern Cape had the least number of publications, which could also be attributable to the absence of a university in the province until 2014; it is also the smallest province by population. However, it was a sign of encouragement that there was some scale of knowledge production on school governance in all provinces, albeit to varying degrees.

Although in the same category as the Northern Cape in terms of universities, Mpumalanga had a higher volume of publications, which could be attributable to the association of the provincial Department of Basic Education with a few Gauteng-based universities. While this analysis gave an indication of provinces where school governance research is being conducted, it inadvertently revealed universities that have more research capacity in the school governance area. It also became apparent that the most productive provinces were associated with more traditional universities, rather than the new universities of technology. This unevenness across the provinces suggests knowledge is being produced in some provinces while very little is produced in others, which could lead to different policy foci or less well-informed foci between provinces.

Distribution of Authorship

Another notable pattern was that authorship emerged to be located in the hands of the same scholars. Provinces that have a higher concentration of publications appear to be dominated by the same authors. For example, in KwaZulu-Natal, the majority of the publications are between two authors, Mncube (5) and Duma (3). Gauteng had a much more diverse group of contributors, but knowledge still appeared concentrated in the hands of a few authors who had more than one article spread over the years (e.g. Heystek 5; Mestry 3) as opposed to once-off publications. Again, given the nature of academic work, we did not find it surprising that the "locus of authorship" (Hallinger 2014, 563) was concentrated in a few authors based within traditional universities. We evidenced a reasonable degree of co-authorship among established and emerging scholars and less between two or more established scholars (e.g. Bush and Heystek). Although we did not analyse this in detail to examine who the authors were and how far they were in their academic careers, we deemed it was a positive indicator of a possible mentoring relationship emerging between established scholars and their research students or younger colleagues. This could suggest the continuance of school governance research beyond the current "gurus", but clearly we would need more data to ascertain the claim. There was also, albeit on a smaller scale, an observable pattern of collaboration between local and international researchers, resulting in some international publications. In his review of research reviews in educational leadership and management, Hallinger (2014) also found a small set of scholars engaging in co-authorship. Thus, although not as widespread as we had anticipated, we found it encouraging that the majority of knowledge producers were researchers based in local South African universities. Collaborations and co-authorships, particularly between established and emerging researchers, ensure that important problems receive sustained focus over a period of time.

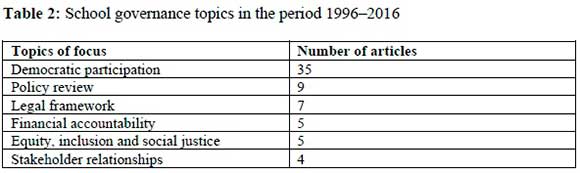

What Topics and Theoretical Constructs Underpinned This Research?

We were also interested in exploring general trends of topics covered in school governance research. We asked this question to understand aspects of school governance that attract research interest and what knowledge trends emerge from them. Leithwood and Menzies (1998a) have analysed trends in topic coverage in reviewing the literature on the implementation of site-based management at different times within the evolution of the field. Other reviews on the broader subject of leadership and management have also conducted an analysis of topics studied. Interestingly, school governance has been a topic in some of these previous reviews (e.g. Bush and Glover 2016; Hallinger and Chen 2015), yet we could only identify two reviews that were dedicated to aspects of school governance. Our analysis in this review showed that research has been underpinned by several features that explain the governing body's role, functions and behaviours (such as financial accountability, policy making and legal framework) as well as those that have been influenced by principles of social justice (democratic participation, decentralisation and equity). We grouped different topics into broad classifications whose frequency is illustrated in Table 2 below. The subsections that follow unpack the key themes addressing the above question. It is to be noted that some topics overlap, with some articles addressing several issues that cut across more than one grouping. Hence, the total number of articles does not add up to the total of 56.

Democratic Participation

The table above shows that democratic participation was the most common topic with the highest number of articles (35), making up 62.5% of all articles. In our classification, we used democratic participation as a broader term encompassing democratic participation, representation, decentralisation and devolution. Unpacking this broader classification revealed that many articles tended to address these concepts together and used a combination of these concepts, hence this classification. We used democratic participation as we felt it represents both the policy standpoint as well as the practical implementation. There is an observable pattern in the earlier articles published between 2001 and 2005 exploring the notion of learner representative councils and the extent of their actual participation in governing bodies. This is perhaps unsurprising given that the SASA (1996) was the first piece of legislation mandating learners' participation in the governance of schools and would have caught researchers' attention. The second pattern we observed in this regard concerns the extent of parental participation given low levels of literacy amongst parents, particularly in rural, informal and some township communities. We noted, however, that the notion of learner and parent participation and/or representation was present in the articles throughout the period of review, with research raising similar issues around the lack of meaningful participation driven mostly by a lack of capacity and illiteracy. However, these analyses hardly moved beyond surface issues and into deeper social justice analysis, suggesting a lack of progress in this area of research.

We observed that issues around decentralisation as a concept were addressed through conceptual studies published mostly in the first decade of the research period that problematised participation and attempted to provide a theoretical explanation. Beckman (2002) and Lewis and Naidoo (2004; 2006) produced conceptual articles providing a critical engagement with decentralisation and devolution of power. It is noticeable that the use of decentralisation as a concept is not as frequent in this body of research, which is surprising given its implications for local decision-making and its dominance in international school governance literature. However, we discern that this is probably indicative of the nature of the problems South Africa is dealing with in school governance. The SASA outlines the roles and functions of school governing bodies underpinned by principles of democratic participation and decentralisation. Yet, research focuses more on participation and/or representation that is harmed by a lack of clear understanding of the governance role and parents' illiteracy, particularly in rural areas (see Bantwini, Moorosi, and Diko 2017). The dominance of school principals in the governing bodies and the illiteracy of parents (mostly in rural areas) prevent the latter's full participation, leading to tensions between governors and principals (Bush and Glover 2016). This issue has had permanent presence in the articles both conceptually and empirically, arguably due to contextual challenges that individual schools, and to some extent districts and provinces, are facing. We engage this aspect a little further in the discussion below.

Equity, Exclusion and Social Justice

The findings from Table 2 above show that there were five articles that directly addressed issues related to social justice, making up only 8.9% of the overall sample. These articles were published between 2008 and 2015. There was at least one article addressing gender and two addressing social justice directly and noticeably written by one person (Mncube 2008; Mncube, Harber, and Du Plessis 2011). Although at least one article made specific reference to black parents, it was a form of categorisation and not a race issue. None of the articles addressed racial issues explicitly or even under the banner of diversity. We found this surprising given the racial tension in many of the schools, particularly the relative under-representation of African parents in former model C schools and in some cases former Indian and Coloured schools. This observation is particularly striking as black parents are highly under-represented in some of the former model C schools, despite the reports that suggest that the African learner population has increased. Two other articles in this category were about inclusion and equity. We revisit this issue again in one of the sections below.

Financial Accountability

Financial accountability is another topic that received significant attention during this period, and this topic was addressed in 8.9% of publications. Mestry (2004; 2006) explores the role of the governing body in managing the school's finances and shows how the school principals end up taking charge, perhaps due to lack of clarity of policy and parents' inability to understand finances. Indeed, one of the significant challenges experienced by governing bodies revolves around financial management, which ironically brings the issue of representation and participation back through the back door. Fundraising is a key function of the SGB stipulated by the SASA, which in the reality of most contexts suggests parents' inability to carry out such functions. Several other studies were conducted on aspects of governance, including the assessment of the implementation of the SASA, which we see largely through conceptual papers that were part of this review. Bush and Glover's (2016) review found an uneasy relationship between principals and governing bodies as one of the features of research on educational leadership and management in South Africa. Although school governance was not their exclusive focus, their finding is important as it characterises school governance research thus far.

Legal Framework and Policy Making

We combine legal framework and policy making as we find them related. Collectively, articles under this category represent a total of 28.5%. Many of the legal framework articles raise important questions about the application and interpretation of legislation that have implications for the implementation of policy on the local school level. This is a significant part of the literature that examines policy reviews and analyses (e.g. Serfontein 2010; Squelch 2001) as well as some legal implications. For example, Serfontein (2010) and Beckman and Prinsloo (2009) analyse cases where the governing bodies were taken to court because of the misapplication of the law. We found these findings particularly interesting given the foundation of the South African Constitution that underpins most legal frameworks including the SASA.

What Methodological Preferences Have Influenced the Research on School Governance?

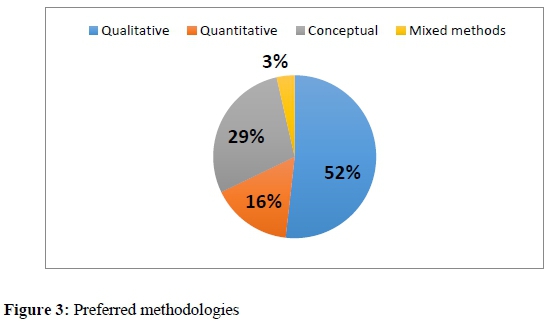

In asking this question, we were interested in methodological patterns of published school governance research over the years. Our analysis revealed a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, with the scale tilting in favour of qualitative case studies. From the 56 articles analysed, 29 of them used qualitative methods while nine employed quantitative methods and a total of 16 were conceptual studies not based on primary data. Only two of these studies used mixed methods, which we found surprising given the surge in the use of mixed methods in recent years. The following diagram (Figure 3) illustrates this representation in percentages:

A preference for qualitative methods was also identified by Hallinger and Chen (2015) and Hallinger (2018) in their reviews of literature on educational leadership and management in Asia and Africa, respectively. We found that within the qualitative articles, there was considerable reliance on snapshot case studies using interviews and observations. We recognise the value of such studies as they are based on real life settings and offer a direct understanding of issues that affect the quality of learning. For example, studies by Lewis and Naidoo (2006), Heystek and Nyambi (2007) and Mncube, Harber, and Du Plessis (2011) are qualitative case studies that help illuminate the power relations inherent in the functioning of school governing bodies. While most of these studies lack generalisability, studies that report primarily on qualitative case studies are helpful as they tend to report on a wider range of school conditions. We acknowledge their worth and value in research, but we also note the absence of longitudinal studies that would perhaps provide a deeper understanding of the governing body functioning over a full three-year term.

With regard to the quantitative studies, we found that despite being quantitative in nature, these studies usually had quite a small sample base. The largest quantitative survey had a sample of just over 1000 participants and involved several groups of participants. Although this was large enough to enable some level of generalisability, it was an anomaly in our review sample as the average sample comprised 200 participants. Moreover, these surveys also usually focused on perceptions of educators on some issues concerning the governing bodies and hardly on observation of governance or governing. Perhaps this should not be surprising given that educators can be accessed in higher numbers than the governing body members within any one school. In terms of analysis of data, we found that statistical analysis was mostly limited to descriptive statistics and there was no higher level of analysis that enabled correlations and or other forms of comparative analysis.

Conceptual articles comprised policy analyses, literature reviews and other non-empirical analyses. Out of a total of 16 articles in this category, at least one article was based on a review of literature on school governance (Joubert 2009) and the majority were policy analyses. We also note that Joubert's review was a commissioned response as part of a larger scale project and so more of a comprehensive literature review than systematic review of research. Within the policy analysis articles there was an observable focus on the legal framework and analysis of the law and its implications for the functioning of school governing bodies. We were not surprised by the overwhelming focus on policy analysis given the policy emphasis in South Africa since the beginning of the new dispensation and its policy change. We were surprised, however, by the high proportion of conceptual articles, albeit at a lower frequency than empirically based articles, which is consistent with Hallinger's (2014) and Hallinger and Chen's (2015) observation.

Overall, while it was encouraging to find more studies based on empirical primary data, case studies and small-scale quantitative studies do not always provide a good basis for policy implications. Hallinger (2018) argues that a "continued reliance on relatively 'weak quantitative methods' will inhibit the development of a robust African knowledge base" (2018, 78). Notably, there were no studies conducted on a longitudinal basis, which could suggest trends within, for example, a three-year term of an elected governing body. Hallinger (2014) also argues that the density and scope of empirical research literature in any case must reach a critical mass before it can be ready for systematic review. Perhaps this explains the presence of only one research review paper in the identified period, and that even on a global scale we could identify no more than two reviews of literature on the school governance aspect alone, both by the same authors (Leithwood and Menzies 1998a; 1998b). However, it is notable that one of the reviews based on the South African literature (Bush and Glover 2016) addressed school governance as a subtopic and a more recent review by Hallinger (2018), on the African continent, marked school governance as an area developed enough to warrant a systematic review.

To What Extent Does the Social Justice Agenda Influence School Governance Research?

The direct classification of equity, exclusion and social justice received the least attention (8.9%). However, if we take the broader social justice definition in the South African context collectively to include equity, democratic participation and representation, 71.4% of the reviewed material on the surface appears to be addressing some elements of social justice. However, the explicit engagement with social justice as a framework including mention of the social justice construct was evident in only two of the reviewed articles, notably by the same author. Thus, we observe a gap in the use of social justice analysis in school governance research despite the overwhelming focus on democratic participation. This is evidently a gap that needs attention from researchers in this area and we want to take this opportunity to call for more research that asks high impact questions on social justice. In view of the inherent inequalities in South Africa, research that is underpinned by social justice principles should challenge oppressive assumptions, attitudes and behaviours rather than just explain the cause of problems. Carlisle, Jackson, and George (2006, 57) contend that "schools promote equity and inclusion within the schools and the larger community by addressing all forms of social oppression". In the South African context, Mncube (2008) and Heystek (2011) help us acknowledge that by focusing on democratic participation and representation school governance is already underpinned by principles of social justice. However, if we are to argue for quality education that caters for the needs of the diverse South African society, we need to look beyond democratic representation and ask more directed questions into the different ways in which inequalities and inequities are reproduced within the education system. We argue that school governance is one such area where post-colonial and post-apartheid power imbalances reside, exerting control through hegemonic cultures and class privileged forms of governing. What we need is direct application of social justice theory in conducting school governance research so that we can begin to ask important questions that interrupt rather than maintain the social order. As Connell (2012) suggests, we all need to take responsibility in creating a socially just education system.

It should be borne in mind that the review focused only on the topics and abstracts and not the details of content. Thus, the extent to which school governance research promotes equity either within governance structures themselves or in the provision of education in general would be worth exploring in greater depth in existing research and through new empirical research. Previous international research has problematised the participation and representation of governors on the governing bodies (Brehony 1992; Deem, Brehony, and Heath 1995), with Brehony (1992) highlighting the material and cultural inequalities that prevent equal decision-making in schools. Deem, Brehony, and Heath (1995) argue that the centrality of power relations in school governing body practices make it impossible for governors to act as "critical citizens". These issues are relevant to the South African context and resonate with some of the local literature in existence. This makes school governance a fertile space for social justice work, which should be carried out more explicitly.

Our analysis reveals a significant presence of school governance research, even though we had expected more. It also reveals a gap with regard to longitudinal research that could offer informed insights on the operations of school governing bodies. Heystek (2011) argues that while the three-year term of a school governing body does not give the elected body enough time to master their roles, it does send a "strong representative and democratic message" (2011, 465). We would like to reiterate the call for more nuanced engagement with school governance research that not only helps us understand the functioning of the school governance system, as Motala and Pampallis (2005) suggest, but also helps us improve the field and make it more equity driven and socially just.

Limitations

In the context of the broad findings presented above, we wish to revisit and highlight a few important limitations inherent in our approach to this review. The first limitation concerns the nature of the database we used in the review and the underwhelming volume of reviewed articles compared with the possible existing corpus. We used one main database, Google Scholar, and relied only on material that is electronically available. Methodologically, this is adequate as it indicates a scientific approach to data collection. However, while this may have worked for the purposes we wanted to achieve, we do realise that a whole range of relevant literature available in print journals, research reports, books and book chapters as well as theses and dissertations has been left out of this review. We have reason to believe that, while inclusion of such material would have increased the volume (scope) of review material, it may not have added a different dimension to the patterns in the nature of research published on school governance. Notwithstanding, this review serves as an important starting point for the identification of gaps.

Second, a further delimitation involved the use of search words and phrases. The search phrase was limited to articles containing "school governance" or "school governing bodies in South Africa" or other descriptors that suggested the functioning, role, behaviour or school governors such as "educator governors", "learner representative councils", and "democratisation in schools" within the title. This facilitated a systematic search of electronic educational journals in South Africa and every other journal where at least one article on school governance in South Africa was found, finally leading to a systematic identification of the articles that constituted a corpus for this review. We acknowledge that our search criteria, and particularly the use of certain phrases and exclusive focus on digitised and electronically available material, omitted other potentially relevant publications; it was, however, the most efficient way to ensure consistency, systematicity and manageability of the review material.

Third, we recognise that school governance is hardly a standalone field, but a subfield or an aspect of the broader leadership and management literature. A significant body of knowledge on school governance could be embedded in the broader literature, since we did not conduct a thorough search of all educational journals in South Africa and all educational leadership and management journals globally. Our search led us to 24 journals out of a much wider range of journals to which South African researchers have access for publication. A search by findings, rather than certain words and phrases in the title as we did, could have possibly elicited more available research material. We would encourage future researchers and reviewers to consider more carefully the findings reported in the studies as some knowledge on school governance may be implicit within the broader field.

Lastly, we limited our search to articles published in the English language. South Africa has 11 official languages and, while it is improbable that material could be published in all of them, there were articles published in Afrikaans that we deliberately excluded from the review for consistency. We acknowledge that this review examined only a portion of a possible corpus of existing research and would like to encourage further reviews to take that body of knowledge into consideration.

Conclusion

All the above notwithstanding, the review was a necessary and useful exercise in identifying patterns of local knowledge on school governance. Although we assumed that the body of research would be large, contrary to what we found, we wanted to synthesise the results that could help examine the nature and extent of published school governance research. Taking stock of published research on school governance seemed appropriate and timely; we want to encourage more reviews and sustained conversations on important aspects of school governance, conversations that are informed by evidence that is collected in methods befitting the twenty-first century.

References

Balarin, M., S. Brammer, C. James, and M. McCormack. 2008. The School Governance Study. London: Business in the Community. [ Links ]

Bantwini, B. D., P. Moorosi, and N. Diko. 2017. "Governing and Managing for Education Transformation in the Eastern Cape". In Reimagining Basic Education in South Africa: Lessons from the Eastern Cape Province, edited by MISTRA, 145-69. Johannesburg: Real African Publishers.

Bayat, A., W. Louw, and R. Rena. 2014. "The Role of School Governing Bodies in Underperforming Schools of Western Cape: A Field Based Study". Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5 (27): 353-63. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p353. [ Links ]

Beckman, J. 2002. "The Emergence of Self-Managing Schools in South Africa: Devolution of Authority or Disguised Centralism?" Education and the Law 14 (3): 153-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/0953996022000027835. [ Links ]

Beckman, J., and I. Prinsloo. 2009. "Legislation on School Governors' Power to Appoint Educators: Friend or Foe?" South African Journal of Education 29: 179-84. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v29n2a257. [ Links ]

Bush, T., and D. Glover. 2016. "School Leadership and Management in South Africa: Findings from a Systematic Literature Review". International Journal of Education Management 30 (2): 211-31. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2014-0101. [ Links ]

Brehony, K. J. 1992. "'Active Citizens': The Case of School Governors". International Studies in Sociology of Education 2 (2): 199-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/0962021920020206. [ Links ]

Carlisle, L. R., B. W. Jackson, and A. George. 2006. "Principles of Social Justice Education: The Social Justice Education in Schools Project". Equity and Excellence in Education 39 (1): 55-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680500478809. [ Links ]

Clase, P., J. Kok, and M. Van Der Merwe. 2007. "Tension between School Governing Bodies and Education Authorities in South Africa and Proposed Resolutions Thereof. South African Journal of Education 27 (2): 243-63. [ Links ]

Cochran-Smith, M. 2004. Walking the Road: Race, Diversity and Social Justice in Teacher Education. New York, NY: Teachers' College Press. [ Links ]

Connell, R. 2012. "Just Education". Journal of Education Policy 27 (5): 681-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.710022. [ Links ]

Crouch, L., and D. Winkler. 2008. "Governance, Management and Financing of Education for All: Basic Frameworks and Case Studies". Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2009. Overcoming Inequality: Why Governance Matters. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2009/ED/EFA/MRT/PI/04. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000178719.

Darling-Hammond, L. 1998. "Teachers and Teaching: Testing Policy Hypothesis from a National Commission Report". Educational Researcher 27 (1): 5-15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X027001005. [ Links ]

Deem, R., K. J. Brehony, and S. Heath. 1995. Active Citizenship and the Governing of Schools. Buckingham: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Dieltiens, V. 2005. Transformation of the South African Schooling System: The Fault-Lines in South African School Governance: Policy or People? Johannesburg: Centre for Education Policy Development. [ Links ]

Griffiths, M. 2012. "Social Justice in Education: Joy in Education and Education for Joy". In International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Social (In)Justice, edited by I. Bogotch and C. M. Shields, 233-51. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6555-914.

Hallinger, P. 2014. "Reviewing Reviews of Research in Educational Leadership: An Empirical Assessment". Educational Administration Quarterly 50 (4): 539-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X13506594. [ Links ]

Hallinger, P. 2018. "Surfacing a Hidden Literature: Systematic Research on Educational Leadership and Management in Africa". Educational Management Administration and Leadership 46 (3): 362-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217694895. [ Links ]

Hallinger, P., and J. Chen. 2015. "Review of Research on Educational Leadership and Management in Asia: A Comparative Analysis of Research Topics and Methods, 19952012". Educational Management Administration and Leadership 43 (1): 5-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214535744. [ Links ]

Heystek, J. 2011. "School Governing Bodies in South African Schools: Under Pressure to Enhance Democratization and Improve Quality". Educational Management Administration and Leadership 39 (4): 455-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143211406149. [ Links ]

Heystek, J., and M. Nyambi. 2007. "Section Twenty-One Status and School Governing Bodies in Rural Schools". Acta Academia 39 (1): 226-57. [ Links ]

James, C., S. Brammer, and M. Fertig. 2011. "International Perspectives on School Governing Under Pressure". Educational Management Administration and Leadership 39 (4): 39497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143211404953. [ Links ]

Joubert, R. 2009. "Policy-Making by Public School Governing Bodies: Law and Practice in Gauteng". Acta Academia 41 (12): 223-55. [ Links ]

Kooiman, J. 2003. Governing as Governance. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Kooiman, J., and S. Jentoft. 2009. "Meta-Governance: Values, Norms and Principles, and the Making of Hard Choices". Public Administration 87 (4): 818-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01780.x. [ Links ]

Leithwood, K., and D. Jantzi. 2005. "A Review of Transformational School Leadership Research 1996-2005". Leadership and Policy in Schools 4 (3): 177-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760500244769. [ Links ]

Leithwood, K., and T. Menzies. 1998a. "A Review of Research Concerning the Implementation of Site-Based Management". School Effectiveness and School Improvement 9 (3): 233-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/0924345980090301. [ Links ]

Leithwood, K., and T. Menzies. 1998b. "Forms and Effects of School-Based Management: A Review". Educational Policy 12 (3): 325-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904898012003006. [ Links ]

Leithwood, K., and J. Sun. 2012. "The Nature and Effects of Transformational School Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Review of Unpublished Research". Educational Administration Quarterly 48 (3): 387-423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X11436268. [ Links ]

Lewis S. G., and J. Naidoo. 2004. "Whose Theory of Participation? School Governance Policy and Practice in South Africa". Current Issues in Comparative Education 6 (2): 100-12. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ853842.pdf. [ Links ]

Lewis, S. G., and J. Naidoo. 2006. "School Governance and the Pursuit of Democratic Participation: Lessons from South Africa". International Journal of Educational Development 26 (4): 415-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijedudev.2005.09.003. [ Links ]

Mestry, R. 2004. "Financial Accountability: The Principal or the School Governing Body?" South African Journal of Education 24 (2): 126-32. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/saje/article/view/24977. [ Links ]

Mestry, R. 2006. "The Functions of School Governing Bodies in Managing School Finance". South African Journal of Education 26 (1): 27-38. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1150360.pdf. [ Links ]

Mncube, V. 2008. "Democratisation of Education in South Africa: Issues of Social Justice and the Voice of Learners?" South African Journal of Education 28 (1): 77-90. [ Links ]

Mncube, V., C. Harber, and P. Du Plessis. 2011. "Effective School Governing Bodies: Parental Involvement". Acta Academia 43 (3): 210-42. [ Links ]

Mncube, V., and I. Naicker. 2011. "School Governing Bodies and the Promotion of Democracy: A Reality or a Pipe-Dream?" Journal of Educational Studies 10 (1): 142-61. [ Links ]

Motala, S., and J. Pampallis. 2005. Governance and Finance in the South African Schooling System: The First Decade of Democracy. Johannesburg: Centre for Education Policy Development and Education Policy Unit. [ Links ]

Naidoo, J. P. 2005. Educational Decentralisation and School Governance in South Africa: From Policy to Practice. Paris: UNESCO. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED499627.pdf. [ Links ]

Nandy, L. 2012. "What Would a Socially Just Education System Look Like?" Journal of Education Policy 27 (5): 677-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.710021. [ Links ]

Nwosu, L. I., and J. E. Chukwuere. 2017. "The Roles and Challenges Confronting the School Governing Body in Representing Schools in the Digital Age". Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research 18 (2): 1 -24. [ Links ]

RSA (Republic of South Africa). 1996a. South Africa Schools Act, 1996. Government Gazette Vol. 377, No. 17579. Cape Town: Government Printers. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act84of1996.pdf.

RSA (The Republic of South Africa). 1996b. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, No. 108 of1996. Pretoria: Government Printers. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/images/a108-96.pdf.

Sayed, Y., and R. Ahmed. 2008. "Education Decentralisation in South Africa: Equity and Participation in the Governance of Schools". Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2009. Overcoming Inequality: Why Governance Matters. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2009/ED/EFA/MRT/PI/30. Accessed October 23, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000178722?posInSet=1&queryId=5fd2c341-7529-4f2a-8636-1295aa6d9c27.

Serfontein, E. 2010. "Liability of School Governing Bodies: A Legislative and Case Law Analysis". The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 6 (1): 93-112. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v6i1.119. [ Links ]

Squelch, J. 2001. "Do School Governing Bodies Have a Duty to Create Safe Schools? An Education Law Perspective". Perspectives in Education 19 (4): 137-50. [ Links ]

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). 2009. Overcoming Inequality: Why Governance Matters; EFA Global Monitoring Report. Paris: UNESCO. Accessed October 23, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000177683. [ Links ]

1 Dr Itumeleng Molale passed away on 9 August 2020 while this manuscript was in review.

2 Kooiman (2003) provided first order, second order and third order locations of actors in governance, which Kooiman and Jentoft (2009) further elaborated on.