Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Education as Change

versión On-line ISSN 1947-9417

versión impresa ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.24 no.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/7975

THEMED SECTION 2

ARTICLE

"Moments That Glow": WhatsApp as a Decolonising Tool in EFAL Poetry Teaching and Learning

Katharine NaiduI; Denise NewfieldII

IUniversity of South Africa, South Africa. naiduk1@unisa.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5932-3520

IIUniversity of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. newfield@iafrica.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7248-6025

ABSTRACT

This article, based on a research project with learners in a township school in South Africa, seeks to discuss whether WhatsApp was able to transform the space of the poetry classroom in positive and productive ways. The project was designed in response to research in EFAL (English First Additional Language) classrooms that revealed the marginalisation of poetry as a component in the English classroom, a lack of enthusiasm for it on the part of teachers, and a lack of engagement and energy on the part of learners-all of whom seemed to find poetry remote, irrelevant, unengaging and difficult. The shift to a WhatsApp chatroom, after school hours and outside the classroom, revealed encouraging results. The article seeks to explore the transformative effects of that move, how the chatroom gave learners a creative space in which to express themselves, to speak with their own voice, in their own tongue and to take control of their learning-which seem to us to be decolonising effects. We use Maggie MacLure's idea of selecting "moments that glow" from the text message conversations and the subsequent focus group discussions and questionnaires to show moments of pedagogic decolonisation.

Keywords: moments that glow; EFAL teaching and learning; pedagogy; poetry; agency; decolonising pedagogy; WhatsApp

it was easier to type than to say it with my mouth

(chatroom participant)

Contextualisation

This article is based on a four-week pedagogic project that forms part of a larger empirical research study undertaken by Katharine Naidu into the teaching and learning of poetry in secondary school EFAL (English First Additional Language) classrooms. She set up and conducted a WhatsApp poetry project in one of her research schools in order to determine whether WhatsApp could be a viable option for poetry teaching and learning. The project was undertaken with the consent of the teacher, the Head of the English Department, the Principal, the School Governing Body and participating learners and their parents/guardians; institutional ethical clearance was sought and granted. Denise Newfield's role is that of co-author of the article. The research school followed the EFAL curriculum: that is, the English curriculum for speakers taking English as a first additional language,1 not as a first language or mother tongue; English was their second or in some cases their third, fourth, of fifth language. Twenty-six years into South Africa's democracy, and despite a series of committed attempts at educational reform through policy and curricular revisions, the legacies of Bantu Education have not been entirely erased. The previous structural inequalities in training, staffing, material resources and the infrastructure of apartheid education, a separatist educational system that discriminated against black children, have not yet been rectified.

This article was written during COVID-19 lockdown, when schools around the world were closed, and privileged children in South Africa, as elsewhere, were getting their lessons online, by means of expertly produced videos or classes on Zoom led by their teachers. However, ongoing inequalities have created a situation where the majority of schools in South Africa have not been able to shift to online learning because of inadequate computer devices and connectivity to the internet (Fataar 2020; Van der Berg and Spaull 2020). The classroom research on which this article is based took place in the years just prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, when many schools had not contemplated moving to digital forms of teaching and learning. Poetry lessons in the research school took place in classrooms, and the emphasis tended to be on line-by-line explanation of the poem by the teacher. Some South African schools still have no electricity, although the government is trying to remedy this. Poetry, formerly a compulsory component of subject "English", has become optional in secondary school EFAL classrooms in post-1994 curricula. It is considered difficult, problematic and alienating. There are anxieties about its difficult language as well as its cultural remoteness (Andrews 1991; Leshaoi 1982; Newfield and Maungedzo 2006). Furthermore, paradoxically, another reason could be its imaginative evocativeness and openness to differing interpretations for teachers who seek a single answer; or, perhaps, because it seems out of step with today's fast and action-packed versions of popular culture; and, finally, perhaps because of inappropriate pedagogy and forms of assessment.

Although poetry was taught at the research school, it was not studied with great enthusiasm, as Katharine observed in lessons on the set poems. Poems were "translated" line by line, with the meanings of unfamiliar words glossed; tests focused on poetic techniques and figures of speech, which learners found difficult. Although Grade 10 teachers in some South African secondary schools would choose the poems to study- if they chose to include poetry-this school provided a set list of poems to its English teachers. The list included a poem by British colonial poet, Stephen Spender, about his genteel childhood in England, "My Parents Kept Me from Children Who Were Rough" (Spender 1955). However, Spender, a bookish child who had been sent by his parents to elite primary and secondary schools and then to Oxford University, came to support the rights of all human beings to live decently, earn what their labour deserved, in a society free of prejudice, as can be seen in the narrator's response to his parents' views. The poem may be said to express two conflicting attitudes towards social class, the snobbish, class-based views of the parents who wished to keep their son from "children who were rough" and the son's empathy for, and indeed envy of, those children. It is difficult to decide whether the poem's theme is appropriate or inappropriate to a decolonising effort. However, the issue we primarily seek to discuss in this article concerns the decolonisation of pedagogy rather than of text selection. Can a WhatsApp chatroom provide conditions conducive to the decolonising of poetry teaching and learning, even where the prescribed poem is culturally remote and belongs to the colonial tradition of English poetry?

From Classroom to Chatroom: Disrupting the Norm

Our article describes what happened when Spender's poem was studied in a WhatsApp chatroom. The idea of using WhatsApp as a tool for teaching the poem was inspired by a focus group discussion that was conducted with learners to understand their experiences and challenges with poetry lessons in the English classroom. In response to a question concerning the use of the English language in the learners' everyday lives, these non-mother-tongue English speakers said that the only time they used English exclusively to communicate with each other was when they texted. In all other forms of communication, they used the vernacular. Learners said that they found it easier to write in English and speak in the vernacular. In response to a question concerning mobile phone usage, learners expressed interest and excitement. This discussion gave birth to the idea of using mobile phones for teaching the poem. Since mobile phones were not used in classrooms because they were considered unfit for proper teaching and learning, using WhatsApp would need to be done extra-curricularly and after school hours. Arrangements had to be made: the researcher needed to ensure that mobile phones and data would be available to all participants. The group needed to settle upon a time suitable for the poetry WhatsApp chat, considering learners' cleaning, cooking and homework responsibilities. One of the classes chose the 7:00 to 8:30 pm slot while the other class chose the 8:30 to 10:00 pm slot. It was agreed that each class would meet between three and four times per week for the four weeks' duration of the project.

The reluctance of teachers to use cell phones for English teaching was tied, among other reasons, to cell phones' specific form of textual discourse: an abbreviated, colloquial, slang, often ungrammatical form of Americanese that combines numbers and letters in non-standard ways, suited to speed and to being written while standing up, travelling on a taxi, walking along the road, or lying in bed. A key goal of subject "English" remains the acquisition and use of correct standard written English, as teachers across the globe still generally agree. John Quagie, writing in Ghana, says: "One cannot deny the fact that there is the need for teachers to teach and insist that students use the Standard form of English". He stresses that "the many Englishes which students speak and write these days should not be allowed to invade the formal spaces of education" (Kwagie 2009, 9), a view that is shared by many South African English teachers. In answer to the question, "Do EFAL teachers subtract marks for learners' spelling and grammar mistakes in tests and exams?", a well-known Gauteng Head of Department recently answered: "Marks are subtracted in Paper 3, Creative Writing, based on the rubric we use. In Paper 1, we do not award a mark when the spelling is incorrect. In Paper 2, Literature, there are no marks deducted for spelling" (personal communication to researchers, 18 June 2020).

The WhatsApp texts of our research group are rife with examples of non-standard forms such as "ola", "I", "wanna", "pple", "bcs", "it will depend on hw mny I gv u", as well as the use of the ubiquitous emojis. However, since Katharine was concerned with engagement and communication rather than the grammatical correctness or use of standard English, she did not stop to correct errors or interrupt learners when they used instances of "SMS discourse".2 At no time did she wish to constrain their writing. She wanted the chatroom to be a comfortable space for learners, where they would not be afraid to give the wrong answer but, in contrast, would feel free to express themselves without embarrassment. This is not to suggest that she would not teach standard English usage, were she a teacher at the school; on the contrary, she would encourage learners to be proficient in a repertoire of different registers, and to understand their appropriateness to different contexts, such as formal education, work, family and recreation.

Some teachers consider WhatsApp to inhibit careful thought and grammatically correct sentences, and therefore to be unfit for education. However, Katharine was interested in how the affordances of WhatsApp might play out in the teaching of the poem. "Affordances" (Kress 2010, 186-88) refer to the potentials for communication, representation and expression of devices and their applications. WhatsApp encourages quick thinking, brief, rapid articulations and responses; a WhatsApp chatroom enables group interaction. For these reasons, Katharine made a conscious decision to allow learners to lead the discussion as much as possible.

The Question of Pedagogic Decolonisation

We now turn to the question of decolonisation. Decolonisation is a hotly debated topic, campaigned for by South African university students,3 acceded to in principle by educational hierarchies in secondary as well as tertiary institutions.4 In a recent book on decolonisation and curriculum (Jansen 2019), Sayed, de Kock and Motala advocate the inclusion of schooling and teacher education in the decolonial project, but lament that there is "a remarkable silence about pedagogy and the practice of teaching" (2019, 165). This silence indicates that the decolonisation of pedagogy is not easily achievable; rather, it is a complex and ongoing challenge, a "process of becoming" that can only proceed "step by step", as Freire notes ([1970] 1987, 72). In order to define key aspects of what might constitute pedagogic decolonisation, we draw primarily on the work of three iconic scholars, two foundational and one of current importance. They have made an impact in, and continue to be relevant to, the field of educational decolonisation in South Africa. They are South African black consciousness advocate Steven Bantu Biko, Latin American educator Paolo Freire, and Cameroonian-born philosopher Achille Mbembe, who has made his home in South Africa. Mbembe has written about the complexities of the postcolony (2015) and continues to concern himself with the residues of colonial violence in the twenty-first century (Mbembe 2017; 2019). These scholars provide not only a critical commentary on the impact of colonialism on the colonised, but also inspiration for escaping its shackles.

As is well known, Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1987) critiqued the "banking system" of education in favour of one that would provide men and women with epistemological tools for asserting themselves as agents of their own histories and would transform society as well as education (Freire and Macedo 1998, 37). His goal was emancipation, and his educational strategies were based on dialogue and critique of the world through the word (Freire 1987, 75-77; Freire and Macedo 1998, 8). Biko's I Write What I Like (1978) concerned the need for black South Africans to liberate themselves from the "spiritual poverty" engendered by 400 years of colonialism through developing a "black consciousness" that would "make a black man [sic] tick ... pump life back into his empty shell" (28-29). For Mbembe, "[w]e must escape the status of victimhood" and "break with the denial of responsibility" (2017, 178), although present forms of inequality undermine the capacity of many to be masters (sic) of their own lives. He says that teaching and learning, including "the old teacher-learner relationship", should be recalibrated in relation to the new digital environments (2019, 241-3). He considers artistic production to be part of decolonisation, since it can be used as a "defence against dehumanisation", as a means of maintaining hope, and as a liberation of "forgotten energies" (2019, 173). These three writers emphasise the collective over Western individualism. As Biko put it, "[t]he oneness of community ... is at the heart of our culture" (1979, 30). Pedagogic decolonisation is political, stemming from colonial histories of subjugation and demanding emancipation from educational forms of prescription, discrimination, imposition and subjection. Decolonising pedagogies cannot be equated with learner-centred or "progressive" pedagogies, in spite of some overlap in pedagogic goals, such as the promotion of student agency and voice. Putting the learner, rather than the teacher, centre stage may be based on a neoliberal promotion of individualism rather than on empowerment of the collective.

Pedagogic transformation was the conscious aim of Katharine's project. Taking into account apartheid and post-liberation South African educational and socioeconomic inequalities, we shall explore whether decolonising aspects exist in the data, and if so, where, by "diffracting"5 the data through the ideas of these scholars, both past and present. In this way, we hope to contribute to the discussion of decolonisation as a pedagogic practice, even in a small way, and to highlight pedagogic aspects that could be useful to teachers and practitioners who wish to take a decolonising orientation in their work.

Methodology: The Wonder of Data and Moments That Glow

A popular method of data analysis in qualitative research is thematic content analysis. As researchers, if we applied a thematic content analysis to our WhatsApp data on teaching the poem, "My Parents Kept Me from Children Who Were Rough", we would have looked for recurring themes. Some of these recurring themes might have focused on the learner's interpretation of the poem, the ways in which learners engaged with figurative language, and how the teacher scaffolded the poem for the learners. This approach privileges sameness in the data so that it can be coded as a theme; however, it may fail to notice the unusual elements, which the researcher may not even have imagined. In contrast to thematic content analysis, Maggie MacLure's approach to data analysis focuses on "moments that glow" (MacLure 2013a; 2013b; 2013c). These are moments of "wonder": a quality that resides in and radiates from the data as a result of "the entangled relation of data-and-researcher" (MacLure 2013a, 228). They are moments of affect and intensity that make an impression on the researcher: "We are no longer autonomous agents, choosing and disposing. Rather, we are obliged to acknowledge that data have their ways of making themselves intelligible to us". "On those occasions" it feels "as if we have chosen something that has chosen us" (MacLure 2013b, 661).

According to MacLure, researchers should be open to what is in the data, so that they can "recognise" (Archer and Newfield 2014; Taylor 1992) signs of interest and significance, whether of positive or negative import, and especially if provocative, puzzling or problematic, points that would not have emerged in a traditional thematic analysis. According to MacLure, these moments have an "untapped potential in qualitative research" (MacLure 2013a). We decided to experiment with this approach to data analysis using the data set from the WhatsApp conversations, focus group discussions and questionnaires. The moments illuminate for us what happened in the chatroom (the classic ethnographic question): how learners acted in that space, how they reacted to and interpreted the poem, and what arose from their encounter with WhatsApp for learning purposes. We now present and comment on a selection of moments that glowed in the sequence that they occurred.

Moments That Glow

Moment 1: "Eish just try being proffesionals"

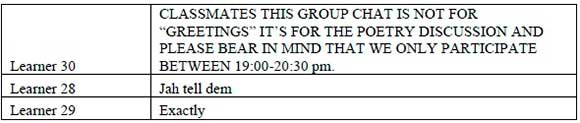

A few hours before the time set for the first chat, in the afternoon, learners began texting one another. They could not wait to fill the empty WhatsApp slots in front of them; the empty slots called to them. The notion of machinic agency and of human-machinic interfaces has been asserted by a range of scholars, including media theorist, Marshall McLuhan (1964) and feminist scholar and historian of technology, Donna Haraway (1985). Although the poetry chatroom had not yet officially opened, some learners could not resist typing letters, numbers, and symbols into it, their thumbs nimbly tapping on the machine, which they held easily without stress, like an "extension" of their bodies (McLuhan 1964, 156-57). They greeted one another with enthusiasm and anticipation to make their presence felt in the chatroom. However, knowing that the evening was the allocated time for the chat, and not the afternoon, a few learners took it upon themselves to remind the others of this.

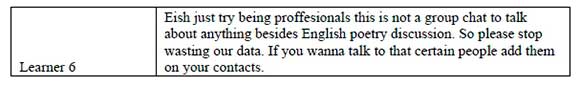

Learner 30 expressed her irritation by texting in upper case to learners who disrespected the pre-negotiated time of the chat, and she was supported by other learners. This immediate display of responsibility and respect in relation to the purpose of the chatroom and the available data was echoed by other learners, for example, Learner 6:

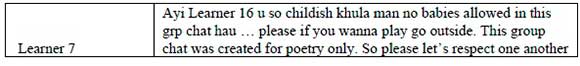

When Learner 16 sent an audio message on the chat, Learner 7 scolded:

By consensus, learners themselves, rather than the teacher, began to establish a chatroom culture from the start; this included respect for the task at hand and a modus operandi that included sociality, decorum and warmth.

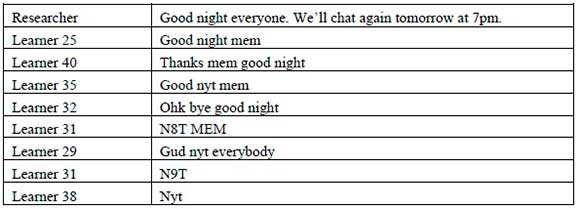

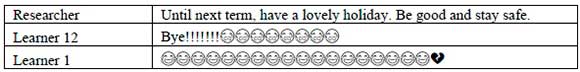

The learners were building a poetry chatroom community. They greeted one another with politeness and affection at the beginning and end of every lesson, as the fragment below shows.

At the end of the term when the chatroom project was to end, Learner 12 responded with one word and eight emojis showing a crying face, and Learner 1 responded with 18 sad, crying face emojis and one broken heart, indicating their regret at the end of the chatroom as a community.

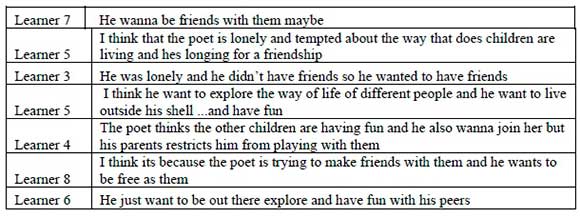

Moment 2: "You might end up doing flabbergasted things that can also affect you in future"

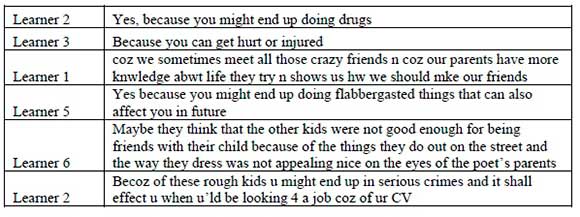

As mentioned previously, the prescribed poem for Grade 10 learners that was to be discussed in the WhatsApp chatroom was "My Parents Kept Me from Children Who Were Rough", written by English poet Stephen Spender nearly a century ago, about a world that is very different from the learners' context. The next fragment gives an idea of the way learners engaged with the poem. They did not do a line-by-line analysis, but rather were interested in connecting the poem to their own lives. In answer to the teacher's question, "Do you think that your parents should protect you from the 'rough' children that the poet talks about? Tell me why?", the learners answered:

The learners identified with the protective, middle-class values of Spender's parents. They agreed that their parents should protect them from "rough" children, those who might engage in dangerous behaviour on the streets. A sense of future aspiration inheres in this moment where the learners see the behaviour of the rough boys of the poem as delinquent behaviour-"doing drugs" and ending up in "serious crimes"-from which they distance themselves.

Learner 5's "Yes, because you might end up doing flabbergasted things that can also affect you in future" is not simply a moment that glows, but one that ignites, where grammar gives way to poetic creativity. The transfer of the epithet "flabbergasted" from the human feeling of exasperation, of being stunned, dumbfounded, thunderstruck by an unexpected statement or incident, to teenage behaviour that evokes such feelings and negatively impacts on the teenager's future, is a powerful example of linguistic inventiveness, entirely apt in a poetry lesson. It is a sign of learners engaging with the poem in terms of their own lives, making it their own by translating both its content and language into their own environment.

Moment 3: "They said i will duplicate my life like a nuclear bomb that has fallen at Dubai"

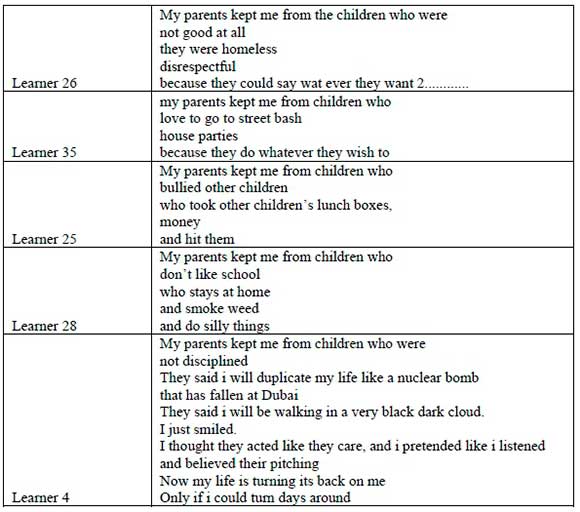

During one poetry chatroom discussion, learners were asked by the teacher to write their own four-line poem based on their understanding of the Spender poem, and beginning with the words: My parents kept me from children who were ... . Although they were asked to plan and draft it, most of the learners submitted their poems without any planning, probably because WhatsApp affords and encourages spontaneity. These were some of their responses:

As South Africa's late Poet Laureate, Keorapetse Kgositsile, says, "lived experience" is the bedrock of his poetry:

In writing, I let my imagination reach into the depths of my feeling to bring out what I am most responsive to at the moment of playing my solo with language through the texture of lived experience. (Kgositsile 2018, 15)

These short verses come directly from learners' lived experiences or their hopes and aspirations. The parents of Learner 25 kept her from "children who bullied other children/ who took other children's lunchboxes/ money/ and hit them", while Learner 28 was kept from those "who smoke weed/ and do silly things". Learner 4's parents voiced their fears for contamination of their child by ill-disciplined others in unforgettably vivid township lingo: "They said I will duplicate my life like a nuclear bomb/ that has fallen at Dubai/ They said I will be walking in a very dark black cloud". Here is another moment that ignites, that explodes in its discordant meaning and rhythm. As poet Toni Stuart says, poetry has the "ability to draw out voices that have been silenced" (2020, 132). "Duplicate my life" is a terse phrase conveying a sense of rapid and dangerous copying. When metaphorised as "a nuclear bomb/that has fallen on Dubai" the line shocks. No nuclear bomb has ever fallen on Dubai, as far as we are aware, but Dubai stands today for a thriving, wealthy city, where rich South Africans travel to do their shopping. The line's cadence concludes with a jolt at "Dubai", a phrase written "with "the musicality of [the learner's] own flesh" (Mbembe 2017, xiii). It seems that Learner 4 did not heed the warning that if not careful, he would be walking in the "very dark black cloud" of nuclear fallout, because he says that now his "life is turning its back" on him. The final line of Learner 4's poem reads like a cry from the heart, "only if I could turn days around".

Moment 4: "Do you also forgive people who provoke or bully you and why do you do that?"

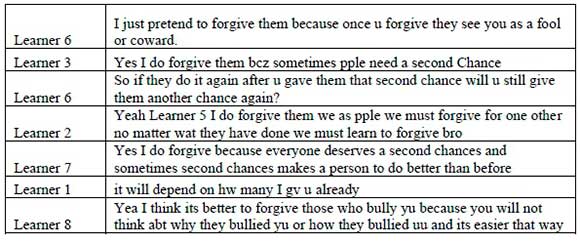

The next fragment spotlights learner confidence and agency. Katharine's classroom observation had revealed that learners rarely asked their teachers a question, even when they seemed to be concentrating on the lesson. Learner 5's question related to the paradoxical final stanza of the poem, where the narrator of the poem, recalling his boyhood feelings, says, "They threw mud/ And I looked the other way, pretending to smile,/ I longed to forgive them". "Guys," asked Learner 5, "Do you also forgive people who provoke or bully you and why do you do that?" His classmates responded enthusiastically:

Although the term "bullying" was not used in the poem, the learner found it himself and used it as a gloss for one of the themes of the poem. Bullying is a common phenomenon in many schools today (Pijoos 2020). Learners are particularly sensitive about it, and the class responded enthusiastically. Most of them were willing to forgive bullies provided that they did not engage in repeated bullying. The phrasing of the responses of Learners 2, 7 and 8 evokes the sense of "forgiveness" embedded in the Christian faith of many of the learners, which probably informed their interpretation of Spender's final line, "I longed to forgive them, yet they never smiled."

The poem does not explicitly state why the speaker wanted to forgive the "rough" children who treated him so badly. Learners used clues from the poem as well as their experience of bullying to interpret this:

Moment 5: TAG (The Amazing Group) and boyz n bucks

The final glowing moment in the chatroom occurred when it was time to say goodbye and leave the group. Learners were adamant that they did not want to leave. When asked why, one learner said: "It's fun and we get to express our feelings and we get to be us". Learners decided to keep the chatroom group going as they "needed each other". They negotiated a new name for it: TAG (The Amazing Group); they used the image below (Figure 1) as their group profile picture and continued communicating about other school-related matters until the academic year was over. A year later, the learners formed a new group for the discussion of social and teenage issues. They called it "boyz n bucks".

Moment 6: "it was easier to type than to say it with my mouth"

In the questionnaire, one learner took on the role of policymaker: "If I was in charge of basic education every child in Southern Africa would be taught via WhatsApp". WhatsApp, the class said, was "practical", as one can text from "anywhere" at "anytime". It gave them a sense of control over their own learning. Learners also pointed to the power of the device: simply holding the phone made them feel good; touching it and typing words on it that would be read and "heard" by all their classmates was exhilarating. The chatroom space, bringing together learners, their cell phones, the poem and the teacher in a specific "entanglement" and set of "intra-actions"6 (Barad 2007, 33, 170, 175-76, 206-7), became a new force for learning and empowerment.

Many of the learners felt that the chat space was "safe": "In a classroom your classmates laugh at you or your comments but on the chat, you feel free commenting." Because they do not speak English as their home language, they mispronounce words and their classmates laugh at them. They also enjoyed the invisibility of the chat: "Learners couldn't see me so if I answered a question badly or funnily and they laughed, I would not see them so my heart would not be broken." The chat was not anonymous because learners' names appeared above their message, but they were not visible, which afforded them a sense of protection. The final point made by learners was about literacy itself rather than psychological or emotional wellbeing. It took us by surprise in relation to the view commonly held by teachers and scholars that the major literacy problem concerns writing, that learners can express themselves orally but fail to do so effectively in writing (Kress 1982; Tonfoni 1994):

Considering how painlessly children learn to talk, the difficulties they face in learning to write are quite pronounced. Indeed, some children never learn to write at all, and many fall far short of full proficiency in the skills of writing. (Kress 1982, ix)

Stein asserts that her student's move from telling a story to writing about it involved "a profound loss" (Stein 2008, 62). Turning these views upside down, Learner 40 put forward a powerfully visceral claim about the difficulty of forming foreign sounds with the tongue and lips, and which points to an affordance of WhatsApp: "I enjoyed the WhatsApp poetry lesson because it was easier to type than to say it with my mouth". This viewpoint may hold implications for learning to write and for writing development in a future of blended, online or WhatsApp learning.

Discussion: WhatsApp as a Decolonising Tool

What role did WhatsApp play? Although not easy to set up for reasons of technology and difficulties of access, once this was accomplished, learners worked with and benefitted from the affordances of WhatsApp: its potential for instantaneous messaging through brief, rapid responses in colloquial SMS registers and emojis. The affordance of the chatroom for multiple members to be part of a group and to interact easily, taking turns, also played a central role. Learners were able to think together, to be privy to one another's thoughts and opinions. WhatsApp enabled collaborative learning. However, since a range of entangled phenomena are involved in any teaching and learning situation, other factors must be acknowledged as having played a role too. One of these is the element of novelty and the excitement that can accompany novelty, since learners had never before used WhatsApp for school-related activities. WhatsApp functioned as a kind of "activation device" (Springgay and Truman 2018, 135), altering familiar procedures, and unlocking and mobilising affective, creative and cognitive intensities.

We now turn to the question of decolonisation. In what ways, if any, do these moments point to elements of pedagogic decolonisation? Learners established a chatroom culture based on respect and care for one another, adherence to chatroom etiquette, accountability to the educational purpose of the chatroom and to responsible use of data. The space of the chatroom became one of community and belonging. Power relations shifted; learners and the teacher shared the space equally in a dynamic dialogue that probed the poem's meaning and related it to local circumstances. The chatroom became a lively space of negotiation, of "intra-action". Learners grew in confidence; they initiated discussions and asked meaningful questions. Learner 5 initiated an in-depth discussion while another learner took on the role of policymaker for his group of classmates-a generation having to confront the complexities and changes of a rapidly digitising world-by proposing new methods based on the affordances of WhatsApp as a pedagogic tool.

"Agency" is a key concept in educational and theoretical approaches (Archer and Newfield 2014; Barad 2007; Francis and le Roux 2012; Jansen 2019), as well as in the decolonising approaches of Freire, Biko and Mbembe, although these scholars do not use the term centrally in their theorising. Agency is a power to act, to think and to feel, a "doing" (Barad 2007; Jansen 2019, 115-80). From a perspective of decolonising pedagogy, the action would be against the strictures of oppressive systems and in relation to personal and group liberation and cognitive development, standing up and walking with their own feet, as Mbembe writes (2017, 162).

Learners spoke in their own voice, not in a generalised way, but as a localised engagement (Appadurai 2004, 66) with the issues of the poem in relation to their own lives. They were agentive in their use of the English language, creatively and innovatively manipulating it in the colloquial ways afforded by WhatsApp. "Forgotten energies" (Mbembe 2019, 173) were awakened as the learners captured their experience in poetic lines. This opened up possibilities towards becoming "makers of culture" (Freire and Macedo 1998, 7; emphasis added) rather than mere receivers of culture, artistic creation and knowledge.

A sense of futurity permeated the chatroom discussions: dangers, temptations and hopes for the future were prompted by engagement with the poem. The learners' dialogues, conversations and actions were infused with "hope" and with "aspirations" (Appadurai 2004, 59-84) for "the transformation of reality" (Freire 1987, 81), as was seen in the final glowing moment.

Conclusion

We have used this story of moments that glow to show how the move from classroom to chatroom temporarily shifted the negative attitudes to poetry that had been manifest before. MacLure's analytical methodology highlighted for us the way the chatroom facilitated learner agency in knowledge construction and imaginative language usage. The study of a poem was enlivened; learners shifted from apathy to enthusiastic engagement; they built the chatroom community responsibly and with respect, and participated actively in their poetry learning from their own perspectives. But there is a cautionary note. It would not be wise to regard WhatsApp as a panacea. We are not suggesting that this single instance-a limited case study-can be generalised to all others, but rather offering it as a potential alternative or supplement to more traditional face-to-face classroom teaching. We are suggesting that this story of moments that glow can be seen as a small step on the long road towards the decolonisation of pedagogy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the teachers and learners of the school for allowing us to conduct this research, and the editors of Education as Change and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We also acknowledge the generous support of the National Research Foundation, Grant No. 105159.

References

Andrews, R. 1991. The Problem with Poetry. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Appadurai, A. 2004. "The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition". In Culture and Public Action, edited by V. Rao and M. Walton, 59-84. Stanford, CA: Stanford Social Sciences.

Archer, A., and D. Newfield. 2014. "Challenges and Opportunities of Multimodal Approaches to Education in South Africa". In Multimodal Approaches to Research and Pedagogy: Recognition, Resources, and Access, edited by A. Archer and D. Newfield, 1-18. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315879475.

Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822388128. [ Links ]

Barad, K. 2012. What Is the Measure of Nothingness: Infinity, Virtuality, Nothingness. Documenta Series: 100 Notes, 100 Thoughts. Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

Biko, S. 1978. I Write What I Like. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Fataar, A. 2020. "A Pedagogy of Care: Teachers Rise to the Challenge of the 'New Normal'". Daily Maverick, June 22. Accessed October 16, 2020. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-06-22-a-pedagogy-of-care-teachers-rise-to-the-challenge-of-the-new-normal/.

Francis, D., and A. Le Roux. 2012. "The Intersection between Identity, Agency and Social Justice Education: Implications for Teacher Education". In Research-Led Teacher Education, edited by R. Osman and H. Venkat, 49-68. Cape Town: Pearson.

Freire, P. (1970) 1987. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum. [ Links ]

Freire, A., and D. Macedo, eds. 1998. The Paolo Freire Reader. New York, NY: Continuum. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. 1985. "A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s". Socialist Review 80: 65-108. [ Links ]

Jansen, J., ed. 2019. Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.18772/22019083351. [ Links ]

Kress, G. 1982. Learning to Write. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kress, G. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203970034. [ Links ]

Kgositsile, K. 2018. Homesoil in My Blood: A Trilogy. Midrand: Xarra Books. [ Links ]

Leshoai, B. 1982. "Traditional African Poets as Historians". In Soweto Poetry, edited by M. Chapman, 56-61. Johannesburg: McGraw-Hill.

MacLure, M. 2013a. "The Wonder of Data". Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies 13 (4): 228-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708613487863. [ Links ]

MacLure, M. 2013b. "Researching without Representation? Language and Materiality in Post-Qualitative Methodology". International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (6): 658-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788755. [ Links ]

MacLure, M. 2013 c. "Classification or Wonder? Coding as an Analytic Practice in Qualitative Research". In Deleuze and Research Methodologies, edited by B. Coleman and J. Ringrose, 164-83. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Manemela, B. 2018. "Decolonising Knowledge, Teaching and Learning in Higher Education". Address by Deputy Minister Buti Manamela at the UNISA Conference on Decolonising Knowledge, Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, University of South Africa, Pretoria, October 15, 2018. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.gov.za/speeches/deputy-minister-buti-manamela-decolonising-knowledge-teaching-and-learning-higher-education.

McLuhan, M. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York, NY: Mentor Books. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. 2015. On the Postcolony. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. 2017. Critique of Black Reason. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822373230. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. 2019. "Future Knowledges and the Implications for the Decolonising Project". In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge, edited by J. Jansen, 239-54. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.18772/22019083351.17.

Newfield, D., and R. Maungedzo. 2006. "Mobilising and Modalising Poetry in a Soweto Classroom". English Studies in Africa 49 (1): 71-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00138390608691344. [ Links ]

Pijoos, I. 2020. "#Crimestats | School Bullying Sees Murders, Hundreds of Serious Assaults". Times Live, July 31. Accessed October 16, 2020. https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2020-07-31-crimestats-school-bullying-sees-murders-hundreds-of-serious-assaults/.

Sayed, Y., T. de Kock and S. Motala. 2019. "Between Higher and Basic Education in South Africa: What Does Decolonisation Mean for Teacher Education?" In Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge, edited by J. Jansen, 155-80. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.18772/22019083351.13.

Spender, S. 1955. Collected Poems 1928-1985. London: Faber and Faber. [ Links ]

Springgay, S., and S. Truman. 2018. "A Walking-Writing Practice: Queering the Trail". In Walking Methodologies in a More-Than-Human World: Walking Lab, by S. Springgay and S. E. Truman, 130-42. London: Routledge.

Stuart, T. 2020. "Voices in the Mirror: Poetry as a Tool for Social Change". In Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets 2000-2018, edited by M. Xaba, 151-64. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Taylor, C. 1992. Multiculturalism and the Politics of Recognition: An Essay. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Tonfoni, G. 1994. Writing as a Visual Art. Oxford: Intellect Books. [ Links ]

Van der Berg, S., and N. Spaull. 2020. "Counting the Cost: COVID-19 School Closures in South Africa and Its Impacts on Children". Research on Socioeconomic Policy (RESEP). Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Van-der-Berg-Spaull-2020-Counting-the-Cost-COVID-19-Children-and-Schooling-15-June-2020-1.pdf.

1 In South Africa, English language studies at secondary school level are divided into Home Language (HL), First Additional Language (FAL) and Second Additional Language (SAL).

2 SMS discourse came into existence because SMS (the Short Messaging System) only allowed 40 characters.

3 In 2015 and 2016 the #FeesMustFall protests in various universities in South Africa demanded free education, decolonisation of the education system, transformation of universities and the insourcing of general workers.

4 The Deputy Minister of Higher Education and Training in South Africa, Buti Manemela, stated, "[i]n the context of South African higher education, decolonisation is the comprehensive transformation or change of the curriculum and institutional cultures to primarily reflect and promote African context" (2018).

5 We use the term "diffraction" in a Baradian sense. For Karen Barad (2007), a diffractive analysis refers to reading one's data in and through theory in an affirmative way that leads to new insights. In this article we diffract the glowing moments through decolonial and pedagogic theory.

6 Barad's neologism "intra-action" is distinguished from "interaction" by the emphasis on the inseparable relationality of the participants (human and non-human) in the encounter. "Intra-action" affects participants in dynamic ontological ways.