Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.24 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/7819

THEMED SECTION 2

ARTICLE

Reflections on Decoloniality from a South African Indian Perspective: Conceptual Metaphors in Vivekananda's Poem "My Play Is Done"

Suren Naicker

University of South Africa. naicks@unisa.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8680-930X

ABSTRACT

Swami Vivekananda was an influential Indian saint, poet, philosopher and political revolutionary. His work can be seen as a conduit for South African Hindus who are part of the Indian diaspora, allowing them to connect with their historical, cultural and spiritual roots in the religious and conceptual world of India. The first step to decolonising those who have been subjected to colonial hegemony is to (re)connect them with their intellectual and spiritual roots, and it is argued here that this is precisely the zeitgeist behind Vivekananda's life and mission in general. His poetry is particularly valuable because he wrote in English, instead of his native Bengali, and was thereby able to reach English-speaking Hindus all over the world. In 1936 Indians in South Africa decided to adopt English as a lingua franca, both as a language of teaching and learning, and as a home language. This article focuses on one of these poems, "My Play Is Done", which Vivekananda composed in 1895 in New York. The poem presents the human condition from a Hindu perspective, which differs substantially from the Western way of thinking. This article explores these concepts within the framework of conceptual metaphor theory. With reference to metaphors used in the poem, various aspects of Hindu philosophical thought will be explored, showing how Oriental conceptual reality differs from Western thought. This provides a link to an ancient precolonial way of thinking, accessible to diasporas around the world.

Keywords: decolonisation; conceptual metaphor theory; indigenous knowledge; cognitive linguistics; Vivekananda; Hinduism; global South

Introduction

"Decolonisation" is a buzzword in both South African politics and academia. This is a layered concept, which encompasses finding one's roots, allowing one to get in touch and reconnect with a rich cultural history that has been lost as a result of being systematically marginalised and denigrated both politically and culturally. The current generation of South African Indians (including myself) are a case in point, having accommodated and assimilated into the Western/Eurocentric linguistic and cultural norms of South African society. This process has happened systematically during the country's chequered colonial history, along religious, cultural and linguistic parameters. Colonisation gradually entrenches the belief that one's culture and beliefs are inadequate or lacking in some way (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2012, 4). Hence, the first step in reclaiming one's cultural history with unapologetic pride is getting in touch with that cultural history, which has been eroded.

The current generation of Indians in South Africa are essentially monolingual speakers of English, though most are multidialectal, or bidialectal at least (Naicker 2019a). Hence, a body of work such as Vivekananda's Complete Works, written mostly in English (very small sections have been translated), is the perfect segue for culturally disenfranchised persons in the Indian diaspora to take the first step into an ocean of wisdom that they have lost touch with. In this regard, Delgado et al. (2000, 8) mention cultures being more or less relevant to other cultures. In South Africa, Indian and Hindu culture was "less relevant" within the colonial context, but Vivekananda's teachings and writings managed to achieve relevance to colonial society and uplift the Indian diaspora. Likewise, Coolsaet (2016, 166) writes of a "hierarchization of cultural values" that precludes some groups from "participating in social interaction on equal footing with others". In this context, Vivekananda and others of his ilk elevate and instil a sense of pride in a marginalised minority group. Quijano (2007, 176) explains the colonial mindset when he argues it is not surprising that

history was conceived as an evolutionary continuum from the primitive to the civilized; from the traditional to the modern; from the savage to the rational; from pro-capitalism to capitalism, etc. And Europe thought of itself as the mirror of the future of all the other societies and cultures; as the advanced form of the history of the entire species.

Coolsaet (2016, 166) draws on the notion of "cognitive justice", explaining that it is a "a concept originating in decolonial thought" that "encompasses not only the right of different practices to co-exist, but entails an active engagement across their knowledgesystems". By bringing Hindu Indian ideas to the West, and giving the Indian diasporas around the world access to their indigenous knowledge systems, Vivekananda makes a move towards a form of cognitive justice.

In relation to decolonial thought, it is an interesting irony that Vivekananda taught and wrote almost exclusively in English. Delgado et al. (2000, 12) point out in this regard that "the most obvious [example of colonial hegemony], of course, is the reproduction of the nineteenth-century nationalist ideology: one territory, one language, one culture and the consequences it has for the post-enlightenment concept of 'foreigner' and 'citizens'". Vivekananda uses this fact to his advantage, and by using English as his medium was able to reach a far wider audience. The Indian community in South Africa adopted English as a first language, so his work is accessible to them; he took this "tool of colonisation" and used it to decolonialise.

My article is structured as follows: a brief overview of key exponents within the field of decolonial studies is discussed in the first section on "Decoloniality in the Contemporary Global South with Reference to Swami Vivekananda". Here I argue that their overall philosophy is in keeping with the crux of Vivekananda's thinking, and some comparisons are drawn. The "Background" section provides a brief overview of Swami Vivekananda's life and teachings. Thereafter, the "Theoretical Framework" section outlines the basic tenets of conceptual metaphor theory, which is a theory within the cognitive linguistics school of thought, and purports that metaphors pertain to any cross-domain mapping at the linguistic level, the conceptual level or both. After clarifying the basic assumptions of the theory, the "Analysis" section provides a brief analysis of three salient metaphors from Vivekananda's poem, "My Play Is Done". These metaphors draw on the domains of JOURNEY and HOMECOMING.1 Various other conceptual metaphors can be found in the poem, but these are merely mentioned here, as even a superficial analysis would require at least a separate article.

My article, then, focuses on a well-known poem in the Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. This influential corpus of text comprises nine volumes, and serves as the foundation of modern-day Hinduism.

Decoloniality in the Contemporary Global South with Reference to Swami Vivekananda

Like the term "Third World", the phrase "global South" has come to refer to a section of the world that has hitherto been disenfranchised, marginalised and denigrated by those imposing their political, linguistic and cultural hegemony on them. While the phrase "Third World" should not connote inferiority, it does allude to a hierarchy, since it refers to countries that, during the Cold War, were neither aligned with the Anglo-American side (aka the "First World") nor the Soviet Union (the "Second World"). The "global South" does not necessarily imply geographical location, since New Zealand and Australia are not included in this group, despite being in the southern hemisphere, while Kashmir is included, despite being in the northern hemisphere. I believe, therefore, that this is nothing but a euphemism for poorer countries, most of which happen to be in the southern hemisphere. I concur with Maldonado-Torres (2004, 29) in this regard, who points out that for "too long the discipline of philosophy proceeded as if geopolitical location and ideas about space were only contingent features of philosophical reasoning". This is a recurring theme in Maldonado-Torres (2004, 2931), though it raises an interesting point regarding the quandary faced by Indians in modern-day South Africa. Indians in South Africa are displaced, but have had to make several decisions regarding the degree to which they assimilate to Anglocentric norms, knowing that there is an inversely proportional relationship with regard to maintaining one's own culture and the degree of assimilation into the host nation (see Naicker 2012 and 2019a, where I argue that the point of assimilating was economic viability, since failure to inculcate indigenous knowledges into the mainstream Eurocentric culture might entail further cultural and economic marginalisation).

Maldonado-Torres (2004, 30) warns of the dangers of premising one's political and epistemological ideals on a shift from a colonial identity to "the idea of a neutral epistemic subject whose reflections only respond to the strictures of the spaceless realm of the universal". Scholars such as Quijano (2007, 168) point out that such efforts ironically lead to political strife among poor countries, leading to instability, whereby the global Western elite "are still the principal beneficiaries". Quijano (2007, 177) further argues that "it is not necessary to reject the whole idea of totality in order to divest oneself of the ideas and images with which it was elaborated within European colonial/modernity", because instead of throwing the baby out with the bath water, it is more pragmatic to make changes from the bottom up. In this regard, Vivekananda calls for a more subtle approach, using the metaphor of dew, saying that one's actions should be slow "and silent, as the gentle dew that falls in the morning, unseen and unheard yet producing a most tremendous result", adding that much of what has been accomplished in India "has been the work of the calm, patient, all-suffering spiritual race upon the world of thought" (CW-3, 61).2 Speaking in the context of religion (although, in Eastern thinking, there is no separation between the religious, the practical and the political), he points out the following:

[H]ow foolish it was for an exponent of one religion to declare that another man's belief was wrong. It was as reasonable as a man from Asia coming to America and after viewing the course of the Mississippi to say to it: "You are running entirely wrong. You will have to go back to the starting place and commence it all over again." It would be just as foolish for a man in America to visit the Alps and after following the course of a river to the German Sea to inform it that its course was too tortuous and that the only remedy would be to flow as directed. (CW-3, 284)

Bolstering Vivekananda's point, for Maldonado-Torres (2004, 29), "philosophers and teachers of philosophy tend to affirm their roots in a spiritual region always described in geographical terms", though he cites Europe as being at the epicentre. Vivekananda also asserts the roots of Hinduism in India, but there is a rationale behind it: to get the message across. Hinduism adapted to the region in which it was placed, wherever that was: in the same way as the panentheistic conception of "God" in the tradition, the axiology of the religion as a whole can be seen in a similar light. It is adaptable to a particular geo-political region, yet it holds on to the fundamental tenets upon which it is premised. Regarding the issue of spiritual roots, Maldonado-Torres (2004, 31) raises the contentious issue of "authochtony [sic]", which again raises interesting questions for those comprising diasporas around the world, since they have been displaced, and had to invent new identities. Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2009) raises this very question and tackles the issue of what it means to be a native, though he relies on binary oppositions, which in effect exclude marginalised groups such as the Coloured and Indian communities in South Africa. Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2015, 485) points out that "the deepening and widening of decolonization movements in those spaces that experienced the slave trade, imperialism, colonialism, apartheid, neocolonialism, and underdevelopment" expand the debate to include a variety of contexts, including the Indian diasporas around the world; he further mentions India in the broader context later on, but not the South African Indian situation specifically. Here Vivekananda's role in general is to ground culturally displaced Indians, despite their being away from their Motherland. Quijano (2007) ends his article with a call to allow all to choose between various languages, cultural identities and appurtenances without fear, but this would be an oversimplification, since, for example, Indian people in South Africa can wear Western dress without being accused of "cultural appropriation", whereas a White person wearing Indian dress would run the risk of being accused of such. In a different but related example, Delgado et al. (2000, 8) cite Mignolo as pointing out the lack of commensurability regarding the German-Bolivian cultural situation: there is a German channel in Bolivia that gives German news and weather, but one never finds a Bolivian channel in Germany. Again, this raises interesting questions about who is "allowed" to do what, and not, and why, but this is beyond the scope of this article. It is evident, though, that this issue is far beyond a simplistic view of colonial powers as having carte blanche to do as they wish in contemporary society.

In the South African Indian context, two things are worth noting. First, a unique dialect of English has evolved within the South African Indian community. It is unique in the sense that most of the current generation speak it as their mother tongue, yet it is uniquely identifiable as Indian, or as South African Indian. There is considerable scholarship on South African Indian English, and for an overview the interested reader is referred to such works as Barnes (1992; 1993), Naicker (2012; 2019a), and Mesthrie (1991; 1992). The existence of this language variety bespeaks an unapologetic pride within an otherwise marginalised minority in South Africa. Regarding the political and social history of the Indian community in South Africa, this has been recorded by scholars such as Dhupelia-Mesthrie (2000) and Desai and Vahed (2010), to which the reader is referred. The nuances of the community (to which I belong), together with its statistical demographics, religious and linguistic varieties, both inter- and intra-linguistic, and other aspects, are very complex. There is a lot more work to be done in this area.

The next section discusses Vivekananda's role as an influential personality both within and outside India. It will also explain how he paved the way for a new India, and brought about renewed pride in the Indian tradition, especially for the Indian diasporas worldwide.

Background

Swami Vivekananda was a Hindu monk, an influential poet, saint, intellectual and political revolutionary, though none of these roles can do justice to the various domains upon which he had an influence. His spiritual mentor was a Bengali mystic who went by the name of Ramakrishna. Ramakrishna never initiated anyone, but his first twelve monastic disciples founded their own order, and with Swami Vivekananda as their head, founded the "Ramakrishna Order of Monks". Vivekananda and the "brother-disciples" initiated themselves, using the mantras that Kali, who was soon to become Swami Abedhananda, took down "from a monk of the dashanami order" (Abedhananda 1970, 121). This was Vivekananda's idea, and it was here that "Naren3 took the name 'Vividishananda'" (Abedhananda 1970, 121). Thereafter, while wandering around India as an itinerant monk, "he was living as a wandering monk under the name ' Saccidananda'" (Abedhananda 1970, 175-76). He chose the name "Vivekananda" only prior to his first departure to the United States of America (USA). The name "Vivekananda" was chosen for him by one of the local princes who befriended the swami, and suggested the name based on a story that is to be found in the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (Gupta 1974), which documents real-time conversations between Ramakrishna and some of his disciples.

There is a vast body of literature in the Hindu canon that contains detailed analyses of Vivekananda's influence, both internationally and in India. The field of influence and impact he has had on visionaries and exponents from various sectors include science, industry, academia, religious thought and politics, as detailed by authors such as Chaudhuri (2005), Burke (2000), Satprakashananda (1978), Tapasyananda (2011), Bodhasarananda (2008), Mumukshananda (2003), and Dhar (1976). Obviously, this is not an exhaustive list of references, but these sources cover the main aspects of Vivekananda's influence in different domains.

The organisation that Vivekananda started is known as the Ramakrishna Math and Mission; its headquarters is known as Belur Math, north of Kolkata, and the South African branch is in Glen Anil, Durban. To date, this is arguably one of the biggest global neo-Hindu organisations, with branches all over the world. Delgado et al. (2000, 11) point out that "we cannot go back to other 'original' thinking traditions"; but Vivekananda's influence, not only within Indian communities, but also within the Western world, challenges this view. One could even argue that his work is a unique example of original thinking traditions being reintroduced to communities who had lost their connection to them; the Ramakrishna Math and Mission in South Africa is a testimony to this.

Hinduism is said to be "the oldest of the world's living religions", and has "no founder" (Sarma 1996, 3). Other idiosyncrasies, such as its not being a "book-based" religion, make it rather "difficult to distinguish between its essentials and nonessentials" (Sarma 1996, 3). Even so, broadly speaking, Hindu philosophy can be divided into two main branches, each comprising six sub-schools, which are further divided into various schools. Vivekananda repeatedly made claims such as the "latest discoveries of science seem like echoes" of Vedanta philosophy (CW-1, 3, 8). He believed that the Vedanta (being one of the six orthodox schools of Hindu thought) should form the basis of the reformed version of Hinduism that he advocated, and felt that an in-depth study of the Vedanta is all that is required to know the Hindu philosophy, adding: "I think that it is Vedanta, and Vedanta alone, that can become the universal religion of man" (CW-3, 103). Interestingly, influential scholars in the field of decolonial scholarship, such as Quijano (2007, 177), point out that "[o]utside the 'West', virtually in all known cultures, every cosmic vision, every image, all systematic production of knowledge is associated with a perspective of totality". Maldonado-Torres's thesis, which speaks of the rebellion against (Western) ontological separation, is commensurable with this point.4

Regarding the notion of "totality", the non-dualistic school of Vedanta, known as Advaita-Vedanta, postulates that the external material universe is only an apparition, and that people need to realise this truth, instead of mistaking the mundane objects of sense-perception as reality. There are twelve different schools of Hindu philosophico-religious thought, six of which are deemed authentic as they are premised on the Vedic texts (cf. Harshananda 2011 for a detailed exposition). In-depth knowledge is not necessary for my analysis: the important point is that the basic premises of Indian philosophical thought are the foundation of Vivekananda's thinking at the time.

The poem "My Play Is Done" was written in 1895 while the poet was in New York City, and he seemed to have become more and more aware of the fact that his mission on earth was coming to an end. In the poem he supplicates the "Divine Mother" to allow him to return "home", which for Vivekananda would be a blissful state of ananda beyond the polarities of joy and suffering. The theoretical framework and my underlying assumptions are outlined in the next section.

Theoretical Framework

Cognitive poetics is a fledgling field that aims to apply the findings of conceptual metaphor theory (CMT) to the domain of poetry. Works by authors such as Lakoff and Turner (1989) serve as key foundations for this idea, and the reader is referred to them for a more detailed outline. Lakoff and Johnson (1989) popularised the notion of metaphor as a fundamental feature of the human conceptual system. Lakoff (2014) provides a historical overview of developments in the field. The basic tenets that are relevant to the current study will be outlined below, with the caveat that this is a streamlined version of the theory as it applies to the current study.

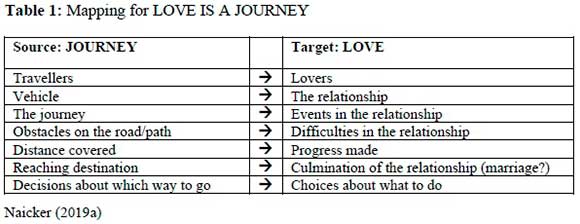

Lakoff and Turner (1989), exploring mostly poetic metaphors from modern English literature, showed that there are superordinate metaphors, under which subordinate metaphors are subsumed; for example, the LOVE IS A JOURNEY metaphor encompasses the LOVERS ARE TRAVELLERS metaphor. Examples are to be found in Lakoff and Johnson (1980) and later works by McEnery and Hardie (2012, 186). There are well-established instances of conceptual metaphors, which speakers of a given language take for granted. The article follows a convention used by Kövecses (2010, 910), where the source domain and target domain are illustrated in tabular form, and relevant aspects of the former are indicated with arrows as transferring onto the analogue in the target domain; this allows the metaphor to be parsed, resulting in a particular conception (or perhaps reconceptualisation) of the target domain. Examples used in everyday English to describe relationships include: "We are at a crossroads in this relationship"; "This is a very bumpy road"; "We're spinning our wheels"; "This is not going anywhere", and so on. These are understood as surface linguistic manifestations of an underlying conceptual metaphor, namely LOVE IS A JOURNEY, and this can be mapped in the following way:

Mapping is a process where selected elements from the source domain (aka the vehicle) are transferred to the target domain (aka the tenor), resulting in the target domain being conceptualised in a particular manner (cf. Chapter 5 in Pinker 2007). In the cited case, relevant aspects from the JOURNEY frame are mapped onto the LOVE frame, and in this context a discussion around common goals would make sense: reaching the destination would map onto some kind of culmination of the relationship, perhaps a matrimonial ceremony.

Of course, LOVE need not exclusively be seen from this perspective, so eliciting this particular source domain creates a certain perception of the target domain, which says a lot about the way this experience speaks to the lived experience of the interlocutors. Once a source domain has been chosen to illustrate a particular concept, certain aspects of the source domain need to be blocked, whereas other aspects need to be mapped. This is known as the invariance principle, initially put forth by Lakoff (1990, 54), and explained critically in more detail by Turner (1990) and Naicker (2019b). Various arguments have been proffered for why the mapping process is unidirectional (so that selected aspects from the source domain are mapped onto the target domain), but it is generally accepted that metaphors are mapped this way, notwithstanding the critiques. This is explained clearly by Evans (2014, 183), who points out that the mapping "goes in one direction". In light of this, the article will explore some of the key conceptual metaphors used by Vivekananda in one of the last poems he wrote, titled "My Play Is Done".

Analysis

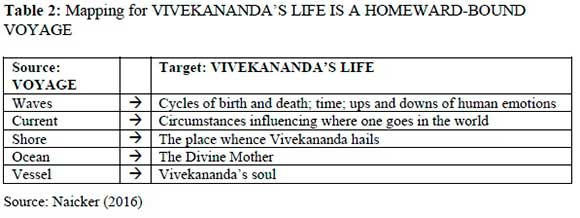

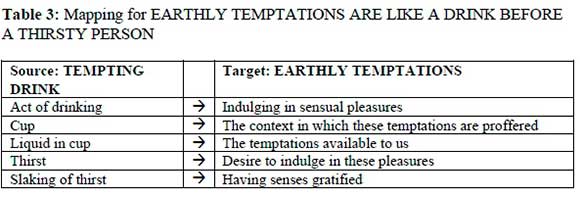

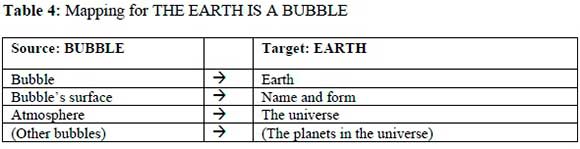

For this purpose, the poem is cited below in its entirety; a sample of the linguistic manifestations of the relevant underlying conceptual metaphors are indicated, followed by a table illustrating the mapping between the source and target domains. Thereafter, the import of the respective metaphors will be discussed. Three metaphors are chosen for particular focus, as they all draw on WATER as a source domain; these include VIVEKANANDA'S LIFE IS A HOMEWARD-BOUND VOYAGE, EARTHLY TEMPTATIONS ARE LIKE A DRINK BEFORE A THIRSTY PERSON, and THE EARTH IS A BUBBLE. Other conceptual metaphors will be mentioned in passing, since they are not the focus of the article.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2015, 490) argues that the philosophies and knowledge of colonised people undergo a process of colonialism. Vivekananda's poems in general are based on concepts and knowledge that characterise Hinduism, and these are expressed using metaphors that derive from the Hindu religion and philosophy. Interacting with his work, internalising these metaphors, can be said to be a kind of epistemological decolonisation.

The poem is taken from CW-6 (102). The lines are numbered for ease of reference:

My Play Is Done

1 Ever rising, ever falling with the waves of time,

2 still rolling on I go

3 From fleeting scene to scene ephemeral,

4 with life' s currents' ebb and flow.

5 Oh! I am sick of this unending force;

6 these shows they please no more.

7 This ever running, never reaching,

8 nor e' en a distant glimpse of shore!

9 From life to life I' m waiting at the gates,

10 alas, they open not.

11 Dim are my eyes with vain attempt

12 to catch one ray long sought.

13 On little life' s high, narrow bridge

14 I stand and see below

15 The struggling, crying, laughing throng.

16 For what? No one can know.

17 In front yon gates stand frowning dark,

18 and say: "No farther way,

19 This is the limit; tempt not Fate,

20 bear it as best you may;

21 Go, mix with them and drink this cup

22 and be as mad as they.

23 Who dares to know but comes to grief;

24 stop then, and with them stay."

25 Alas for me. I cannot rest.

26 This floating bubble, earth-

27 Its hollow form, its hollow name,

28 its hollow death and birth-

29 For me is nothing. How I long

30 to get beyond the crust

31 Of name and form! Ah! ope the gates;

32 to me they open must.

33 Open the gates of light, O Mother, to me Thy tired son.

34 I long, oh, long to return home!

35 Mother, my play is done.

36 You sent me out in the dark to play,

37 and wore a frightful mask;

38 Then hope departed, terror came,

39 and play became a task.

40 Tossed to and fro, from wave to wave

41 in this seething, surging sea

42 Of passions strong and sorrows deep,

43 grief is, and joy to be,

44 Where life is living death, alas! and death-

45 who knows but ' tis

46 Another start, another round of this old wheel

47 of grief and bliss?

48 Where children dream bright, golden dreams,

49 too soon to find them dust,

50 And aye look back to hope long lost

51 and life a mass of rust!

52 Too late, the knowledge age cloth gain;

53 scarce from the wheel we're gone

54 When fresh, young lives put their strength

55 to the wheel, which thus goes on

56 From day to day and year to year.

57 'Tis but delusion's toy,

58 False hope its motor; desire, nave;

59 its spokes are grief and joy.

60 I go adrift and know not whither.

61 Save me from this fire!

62 Rescue me, merciful Mother, from floating with desire!

63 Turn not to me Thy awful face,

64 ' tis more than I can bear.

65 Be merciful and kind to me,

66 to chide my faults forbear.

67 Take me, O Mother, to those shores

68 where strifes for ever cease;

69 Beyond all sorrows, beyond tears,

70 beyond e' en earthly bliss;

71 Whose glory neither sun, nor moon,

72 nor stars that twinkle bright,

73 Nor flash of lightning can express.

74 They but reflect its light.

75 Let never more delusive dreams

76 veil off Thy face from me.

77 My play is done, O Mother,

78 break my chains and make me free!

Conceptual Metaphor 1: VIVEKANANDA'S LIFE IS A HOMEWARD-BOUND VOYAGE

Examples:5

Line 1: Ever rising, ever falling with the waves of time

Line 4: life's currents' ebb and flow

Lines 33-34: Open the gates of light, O Mother, to me Thy tired son. / I long, oh, long to return home! / Mother, my play is done

Line 67: Take me, O Mother, to those shores

Import of Metaphor

In this poem Vivekananda appeals to God, conceptualised as the Divine Mother, to free him from his worldly sojourn and take him back to a place where he can be at peace after a period of strife and hard work. Though rich in symbolism, the voyage metaphor takes the form of a conceit in this particular poem, since the same metaphor is carried through from beginning to end, with various metaphors interspersed in between.

Vivekananda explains his experience through the lens of a Vedantic mindset. In the cycle of joy and sorrow, love and hate and other emotions, each experience is always paired with its counterpart, always playing on the psyche like waves and troughs, going up and down ostensibly without end. He expresses his frustration at this process, and says that he is tired of it and wants it to stop. He wants to return to the shore whence he came, which can be interpreted in various ways. Vivekananda often conceptualised his life and mission as a voyage to unknown lands, and metaphorically spoke about "launching his boat into the sea", for example (CW-8, 179). Aside from an explicit desire to return to his origin, he also calls on the Divine Mother, who is possibly the goddess Kali, to hear his plea and guide him "home". This will release him from his mission, which he feels he has now fulfilled. Further frustration is expressed at his inability to please the waves of time and life, which lead to more and more misery, and he could not stand watching people constantly being caught up in it, despite his warnings.

There are only two options: one must either forget philosophising about the world and spiritual life, and adopt a hedonistic attitude of enjoying the world and all its ostensible pleasures, notwithstanding the fact that this will be evanescent and fraught with all sorts of misery, or one can follow Vivekananda's advice and teachings in an attempt to escape from this world of misery. The poem implies that he had chosen the latter, and more and more he had come to realise that the world is like a floating bubble, and everything associated with it is empty and ephemeral.

The poem creates a sense of frustration and despair, and that, since all this seemingly endless suffering is ineffable, the "ebb and flow" of life is a "current" pulling him in different directions. Vivekananda implores the Divine Mother to provide him with solace by freeing him from the chains of the world so that he can return "home" to the shore; he says that he thinks his mission has been accomplished (his "play is done"), and that he should be allowed to return home. He says that although this is his earnest wish, he feels somewhat lost at the moment, and needs some guidance in getting his "vessel" safely back to the "shore".

Though obviously not intended, one can draw a poignant analogy between the poem and the Indian indentured labourers who were inveigled to come to South Africa, only to find themselves within the shackles of veritable slavery under the British. They arrived on ships, and many died en route. For the descendants of these labourers, reading Vivekananda's poem could take them from those harrowing voyages to South Africa (which started in 1860) to a spiritual voyage back "home".6

Conceptual Metaphor 2: EARTHLY TEMPTATIONS ARE LIKE A DRINK BEFORE A THIRSTY PERSON

Examples:

Line 21: Go, mix with them and drink this cup / and be as mad as they

Import of Metaphor

Vivekananda wishes to illustrate the difficulties involved in overcoming one's desires by drawing the analogy above. The metaphor of drinking can also be used for healthy experiences, as when he requests his fellow monks to pass "the Cup that has satisfied your thirst" (CW-5, 36), since here he is referring to spreading the teachings of Ramakrishna based on his philosophy of Bhakti, which is defined as "devotion; love (of God)", according to Sivananda (2015, 40)7.

This metaphor refers to people who do not heed the warning to refrain from indulging in worldly pleasures; even though Vivekananda understands that it may be the conventional thing to do, he points out that he cannot do more than he has already done in terms of warning them of the dangers and consequences of doing so. From a Vedantic perspective, worldly pleasures lead to suffering born of attachment, and the purpose of human life is to transcend the temptations of the senses and the attachment to the world, thereby reclaiming our oneness with the Divine Consciousness, from which we are temporarily separated.

Though Vivekananda is an avid exponent of Vedanta philosophy, he certainly does not claim that the other schools of thought are to be ignored. In this regard, he sometimes puts forth the Yoga system of Patanjali as the "how" of Hindu spiritual life, the Sankhya system as the "why", and the Vedanta as the "end". In this way, we can understand these as three complementary approaches (see Naicker [2016, 76] for more information regarding this claim). People should follow these three approaches to save themselves from the endless cycle of misery: but if they choose not to heed his call, they must accept the consequences of that and "be as mad" as the rest of the world, chasing pointlessly after worldly pleasures.

Conceptual Metaphor 3: THE EARTH IS A BUBBLE

Examples:

Line 3: scene to scene ephemeral

Lines 26-28: This floating bubble, earth / Its hollow form, its hollow name / its hollow death and birth / For me is nothing

Import of Metaphor

Just as everything has a temporary existence, so too does the earth, and here Vivekananda makes the point that he has done his job in the world, which will also only be here for a limited time, so he is ready to leave.

The title of the poem is a reference to the LIFE IS A PLAY metaphor, and, in realising that his mission is nearly accomplished, he says that his "play" is coming to a close. As part of this realisation, he points out that the entire world is but a temporary structure created out of our spatio-temporal perception. The moment we realise that the world of space and time is like a dream, and we reach a higher awareness that is no longer constrained by the limitations of the senses, the world will "pop" like a bubble, and we will realise that we are nothing but pure spirit, one with the Universal Spirit we call God. Vivekananda's point is that he has done his job reminding people of this fact, and so he now wishes to return home and implores the Divine Being, conceptualised here as the Divine Mother, who is working "through him", to hear his plea.

Having looked at the import of three metaphors from the poem "My Play Is Done"- VIVEKANANDA'S LIFE IS A HOMEWARD-BOUND VOYAGE, EARTHLY TEMPTATIONS ARE LIKE A DRINK BEFORE A THIRSTY PERSON and THE EARTH IS A BUBBLE-it should be noted that there many other conceptual metaphors in the poem as well, which touch on various themes. These include:8

• GOD IS A MOTHER (lines 33, 35, 62, 63, 67, 77);

• LIFE IS A PLAY (lines 35, 36, 37);

• SEEING IS KNOWING (lines 75, 76, 11, 36);

• LIFE IS A CYCLE (line 1);

• LIFE IS A DREAM (lines 48-49, 75);

• LIFE IS BONDAGE (line 78).

Regarding the metaphor GOD IS A MOTHER, it is no secret to those within the Hindu tradition that Divinity is often represented in terms of the feminine. For Vivekananda to do this is especially significant in his own life because, for a long time, he resisted the notion that God can be seen in terms of the feminine. His spiritual development is traced in various works by Nivedita (1910), Dhar (1976), Gupta (1974) and Nikhilananda (2010), which show him as an obstinate youth who was as a member of the Brahmo Samaj, a group that advocated that God is a nameless and formless entity, beyond description and transcendent. Vivekananda gradually accepted the notion that God can be present via the guru, via various avatars, and even as part and parcel of the material world, from a panentheistic perspective. This culminated in the notion that the Divine can also be experienced via various forms of the goddess in the Hindu pantheon, which Vivekananda came to accept after a long spiritual journey, as is outlined in the aforementioned sources. Perhaps drawing on the well-known Shakespearean trope, the LIFE IS A PLAY metaphor illustrates the illusory nature of one's role and identity in life, and if one maps the entailments of the source domain, insofar as one's theatrical role as an actor is temporary, and something put on for a limited time, it seems clear that the "real person" is someone (something) beyond the confines of this earthly life, when the "play is done" (assuming that Vivekananda is not being exclusive in saying that his play is done). He draws on this source domain in several contexts, pointing out, for example, that "the world is a play", and that all "are His playmates" (CW-1, 249). The SEEING IS KNOWING metaphor is quite commonplace, as evidenced by statements such as "I see what you mean", "Your argument is not really clear to me", "I understand the main idea, but I'm a bit blurry on the details", etc. Vivekananda often uses this source domain as well in contexts other than the poem under discussion, including the reference to foresight, pointing out that the majority of people "cannot see beyond a few years" (CW-1, 23). The cyclical nature of life is also fairly well known, with phrases such as "What goes around comes around" making their way into everyday parlance. The word "cycle" is used 71 times in Vivekananda's Complete Works; most uses are metaphorical and draw on various domains. The use of "cyclical" in this manner shows that the notion is not premised on the manifestation of the lexical item in this poem alone. The phrase "is a dream" appears eight times in Vivekananda's Complete Works, and is used metaphorically each time (CW-1, 163; CW-6, 36; CW-7, 52; CW-8, 204; CW-9, 22, 46, 73, 154). With the exception of one (CW-9, 154, where the phrase is used metaphorically to refer to ambition/desire), all these uses conceptualise material life/existence as an ephemeral experience that is not actually "real", premised on the non-dualistic Vedantic idea that for a phenomenon to be real, it must possess immutable consistency; without this criterion, the mere transience of phenomena precludes them from being truly "real". Any primer on Hindu philosophy would explain this idea in more detail, and for such insights the reader is referred to thinkers such as Chatterjee (1996) and Harshananda (2011). The source domain of BONDAGE appears 48 times, and 5.4% of the metaphors used in a sample from the Complete Works pertain to the notion that people are bound to this earthly life as if they are prisoners who are chained by their desires, according to a study by Naicker (2019c) on this topic.

Conclusion

This article has explored three conceptual metaphors pertaining to a metaphorical journey that Vivekananda conceptualises, but the theme of HOMECOMING especially stands out, as he asks his metaphorical "Mother" to open the gates and allow him back home. This metaphorical conceit is poignant and relatable if one extends the concept beyond Vivekananda's life. Many people were inveigled by offers of lucrative work in the various colonies, such as the indenture of Indians in South Africa and the West Indies-this was not unlike the slavery of (mostly) West African people who were taken to the USA between 1700 and 1808. These people know they do not really belong in the country into which they were born, but suffer from a perennial identity crisis: are they Indian, South African Indian, Black, American, or African-American? Myesha Jenkins, a well-known poet and anti-apartheid activist,9 American by birth and Black, moved to Johannesburg, South Africa in 1993, and says that "all these labels are vacuous" and that she "rejects them all". Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2015, 485) argues that this "is because the domains of culture, the psyche, mind, language, aesthetics, religion, and many others have remained colonized": therefore, the situation of having been colonised is very complex. Vivekananda's works offer a way to decolonise various facets of Indian diasporan identity, showing synchronicity with his thinking and other influential scholars from the global South. South African Indians who visit India often have to explain that they are not Indian, yet will happily self-identify as Indian in South Africa. This point is important because if not for Vivekananda (and other visionaries, such as Aurobindo, Yogananda and the like, though arguably also heavily influenced by Vivekananda), the Indian diaspora in South Africa would be completely disconnected from their rich cultural history. Since most South African Indians speak English as their primary means of communication, Vivekananda's works allow a disenfranchised minority group in South Africa to connect with their spiritual, intellectual and cultural roots. Perhaps Vivekananda was a visionary and knew this, or his global reach was serendipitous: he did point out on several occasions though that his teachings will one day be known "all over the world" (CW-1, 126). Through his organisation, the Ramakrishna Math and Mission, Hindu/Indian diasporas all over the world can benefit from his work.

This article has presented a glimpse into an indigenous knowledge system that Vivekananda helped re-conceptualise. This was done by way of looking at three of his conceptual metaphors:

• VIVEKANANDA' S LIFE IS A HOMEWARD-BOUND VOYAGE;

• EARTHLY TEMPTATIONS ARE LIKE A DRINK BEFORE A THIRSTY PERSON;

• THE EARTH IS A BUBBLE.

Each conceptual metaphor was introduced with at least one linguistic manifestation of it, followed by a table illustrating how the metaphor could be mapped, which in turn was expounded upon in light of Vivekananda's philosophy. Other interesting metaphors also emerge from this poem, which were explained in passing: each could be the subject of a complete study. This is fertile ground for future research, not only for themes/metaphors from this particular poem, but from Vivekananda's other poems and from the Complete Works as a whole, which is a gold mine of information for academics, researchers, spiritual seekers, philosophers and others. Through my application of conceptual metaphor theory to Vivekananda's poem, I have demonstrated that it is a viable tool, allowing the researcher to look "beneath" the surface language and explore its conceptual foundations, so it is suitable for all domains where there is a mapping across two mental spaces.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank his colleague, Jolene Raison, for her insightful comments, critiques and assistance on this project.

References

Abhedananda, S. 1970. My Life Story. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math. [ Links ]

Bodhasarananda, S., ed. 2008. Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda-His Eastern and Western Admirers. Kolkata: Advaita Ashram Publication Department. [ Links ]

Barnes, L. A. 1992. Review of A Dictionary of South African English. English Usage in Southern Africa 23 (1): 145-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228195.1992.9971057. [ Links ]

Barnes, L. A. 1993. Review of A Lexicon of South African Indian English. Language Matters 24 (1): 212-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228199308566077. [ Links ]

Burke, M. L. 2000. Swami Vivekananda-Prophet of the Modern Age. Kolkata: Rama Art Press. [ Links ]

Chatterjee, S. C. 1996. "Hindu Religious Thought". In The Religion of the Hindus, edited by K. Morgan, 206-65. New Delhi: Shri Jainendra Press.

Chaudhuri, A., ed. 2005. Swami Vivekananda in Chicago-New Findings. Kolkata: Advaita Ashram. [ Links ]

Coolsaet, B. 2016. "Towards an Agroecology of Knowledges: Recognition, Cognitive Justice and Farmers' Autonomy in France". Journal of Rural Studies 47 (Part A): 165-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.07.012. [ Links ]

Dasgupta, S. 1991. The Prophet ofHuman Emancipation-A Study in the Social Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda. Kolkata: Bijaya Press. [ Links ]

Delgado, L. E., R. J. Romero, and W. Mignolo. 2000. "Local Histories and Global Designs: An Interview with Walter Mignolo". Discourse 22 (3): 7-33. https://doi.org/10.1353/dis.2000.0004. [ Links ]

Dhar, S. N. 1976. A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda: Volumes 1 and 2. Madras: Jupiter Press. [ Links ]

Desai, A., and G. Vahed. 2010. Inside Indian Indenture: A South African Story, 1860-1914. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Dhupelia-Mesthrie, U. 2000. From Cane Fields to Freedom. Cape Town: Kwela Books. [ Links ]

Evans, V. 2014. The Language Myth: Why Language Is Not an Instinct. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107358300. [ Links ]

Gupta, M. 1974. The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. 6th ed. Translated by S. Nikhilananda. Madras: Jupiter Press.

Harshananda, S. 2011. The Six Systems of Hindu Philosophy: A Primer. Chennai: Sri Ramakrishna Math Printing Press. [ Links ]

Kövecses, Z. 2010. Metaphor: A Practical Introduction. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G. 1990. "The Invariance Hypothesis: Is Abstract Reason Based on Image-Schemas?" Cognitive Linguistics 1 (1): 39-74. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.1990.L1.39. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G. 2014. "Mapping the Brain's Metaphor Circuitry: Metaphorical Thought in Everyday Reason". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8: a958. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00958. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G., and M. Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G., and M. Turner. 1989. More Than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226470986.001.0001. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, N. 2004. "The Topology of Being and the Geopolitics of Knowledge". City 8 (1): 29-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360481042000199787. [ Links ]

McEnery, T., and A. Hardie. 2012. Corpus Linguistics: Method, Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511981395. [ Links ]

Mesthrie, R. 1991. Language in Indenture: A Sociolinguistic History of Bhojpuri-Hindi in South Africa. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. [ Links ]

Mesthrie, R. 1992. English in Language Shift: The History, Structure and Sociolinguistics of South African Indian English. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511597893. [ Links ]

Mumukshananda, S. 2003. Monastic Disciples of Swami Vivekananda: Inspiring Life Stories of Some Principal Disciples. Kolkata: Advaita Ashram Publication Department. [ Links ]

Naicker, S. 2012. Review of A Dictionary of South African Indian English. Language Matters 43 (1): 117-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228195.2012.682261. [ Links ]

Naicker, S. 2016. A Cognitive Linguistic Analysis of Conceptual Metaphors in Hindu Religious Discourse with Reference to Swami Vivekananda's Complete Works. PhD diss., University of South Africa. http://hdl.handle.net/10500/22281. [ Links ]

Naicker, S. 2019a. "A Study of Metaphorical Idioms in South African Indian English". Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus 56 (1): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.5842/56-0-784. [ Links ]

Naicker, S. 2019b. "An Analysis of Northern Sotho Idioms with Reference to Conceptual Metaphor Theory in Light of the Invariance Principle". Language Matters 50 (1): 115-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228195.2018.1539118. [ Links ]

Naicker, S. 2019c. "On the Neo-Vedanta as Reconceptualised in Contemporary Hinduism: A Cognitive Linguistic Analysis in Light of Conceptual Metaphor Theory". Literator 40 (1): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4102/lit.v40i1.1528. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2009. "Africa for Africans or Africa for 'Natives' Only? 'New Nationalism' and Nativism in Zimbabwe and South Africa". Africa Spectrum 44 (1): 6178. https://doi.org/10.1177/000203970904400105. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2012. "Coloniality of Power in Development Studies and the Impact of Global Imperial Designs on Africa". Inaugural lecture delivered on 16 October. Accessed September 24, 2020. http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/8548/Inugural%20lecture-16%20October%202012.pdf.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2015. "Decoloniality as the Future of Africa". History Compass 13 (10): 485-96. https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12264. [ Links ]

Nikhilananda, S. 2010. Swami Vivekananda: A Biography. 24th ed. Mayavati: Advaita Ashram. [ Links ]

Nivedita, S. 1910. The Master as I Saw Him. London: Longmans, Green and Co. [ Links ]

Pinker, S. 2007. The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature. New York, NY: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Quijano, A. 2007. "Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality". Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 168-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353. [ Links ]

Sarma, D. S. 1996. "The Nature and History of Hinduism". In The Religion of the Hindus, edited by K. Morgan, 3-48. New Delhi: Shri Jainendra Press.

Satprakashananda, S. 1978. Vivekananda: His Contribution to the Modern Age. Kolkata: Advaita Ashrama Publication Department. [ Links ]

Sivananda, S. 2015. Glossary of Sanskrit Terms. Rishikesh: Divine Life Society Press. [ Links ]

Tapasyananda, S. 2011. Swami Vivekananda: His Life and Legacy. Chennai: Sri Ramakrishna Math Printing Press. [ Links ]

Turner, M. 1990. "Aspects of the Invariance Hypothesis". Cognitive Linguistics 1 (1): 247-55. [ Links ]

Vivekananda, S. 1977. The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Volumes 1-9. Kolkata: Mayavati Press. [ Links ]

1 As is convention in the field of cognitive semantics, conceptual metaphors and domains are written in UPPER CASE.

2 For ease of reference, "CW-3, 61"' will refer to volume 3, page 61 of Vivekananda's Complete Works (1997).

3 Swami Vivekananda's pre-monastic name.

4 https://fondation-frantzfanon.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/maldonado-torres_outline_of_ten_theses-10.23.16.pdf

5 Each metaphor is illustrated by means of a few examples from the poem (or only one if that suffices to make the point); the reader is therefore invited to look at the poem more closely for other examples, since saturation point was reached with regard to justifying the postulation about the conceptual metaphors under discussion. The word(s) that activate the relevant domain is/are written in bold underline, not as in the original.

6 For more details of the process of indentured Indian labourers being brought to South Africa, see Dhupelia-Mesthrie (2000).

7 Also cf. Vivekananda (CW-5, 201), where he explains the link between this concept and the Vedanta philosophy.

8 These are the salient metaphors for my argument here. A treasure trove of other metaphors would emerge from a more in-depth analysis of the other domains, but this article focuses only on one aspect of metaphors from the domain of the JOURNEY.

9 Interview with Myesha Jenkins on 24 August 2019.