Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.24 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/8155

THEMED SECTION 2

ARTICLE

Mapping Pathways for an Indigenous Poetry Pedagogy: Performance, Emergence and Decolonisation

Grace MavhizaI; Maria ProzeskyII

ISTADIO, Faculty of Education, South Africa. gracem@stadio.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1304-4788

IIUniversity of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. Maria.Prozesky@wits.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9747-037X

ABSTRACT

Poetry is notoriously unpopular in high school English classrooms all over the world, and English FAL (First Additional Language) classrooms in South Africa are no exception. We report on a pedagogical intervention with Grade 11 learners in a township school in Johannesburg, where the classroom was opened to indigenous poetry and identities by allowing learners to write and perform their own poetry in any language and on any topic. Rejecting essentialist notions of indigeneity as defined by bloodline or "race", we work with a notion of indigenous identity as fluid and performative, and as inescapably entwined with coloniality. We argue that indigenous poetry, meanings and identities were emergent in the open space created by the intervention. To further explore this emergence, we discuss pedagogy itself as performative, an interaction between teacher and learners in which knowledge is built, stories told and identities sedimented. We focus on what can be learned about possible pedagogical pathways for an indigenous poetry pedagogy from the learners' performances. We identify the constraints and potentialities for a decolonial pedagogy that arise when the classroom is opened to indigenous poetry, and ideas for what such a decolonial pedagogy would look like. The findings suggest that new ways of thinking about the ethics and politics of poetry in the classroom are required, some general to all indigenous pedagogies, and some specific to local South African traditions of praise poetry.

Keywords: indigenous poetry; decolonisation; pedagogy; performance; South African education

Introduction

The study of poetry has been shown to promote language learning among English FAL (First Additional Language) learners, as well as to encourage learners' awareness of and confidence in their cultural identity (Farber 2015; Harris 2018; Xerri 2018). Yet poetry is notoriously unpopular in high school English classrooms all over the world, and English FAL classrooms in South Africa are no exception. The reasons for this situation are manifold. First, the poems prescribed are often foreign to the lifeworlds of learners, containing literary and historical references that limit understanding greatly for non-native speakers of English (Brindley 1980 in Finch 2003, 3), such as South African FAL learners. Poetic traditions that are more familiar to many learners are often not acknowledged explicitly in policy documents. In the South African context, these traditions include praise poetry and music genres such as hip hop and rap. Second, teachers are afraid of working with poetry, often because they feel they lack the necessary knowledge and skills, and when they do teach it they do so poorly, focusing on the technical aspects rather than the meaning of poetry (Benton 1999; Calway 2008; Jocson 2005; Riley 2012). Third, learners come to share the negative attitude of their teachers, believing that studying poetry is dull and pointless (Hanauer and Liao 2016; OFSTED 2007). Finally, in South Africa specifically, the National Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) is highly prescriptive and assessment-driven; poetry is assessed in national written examinations by means of short questions that focus on mastery of figures of speech, diction and imagery (Department of Education [DoE] 2011). This means of assessing poetry helps shape the way it is taught and reinforces the negative perceptions of it among teachers and learners.

This article reports on a pedagogical intervention that aimed to address this negative perception of poetry in a Grade 11 classroom of English FAL learners in Johannesburg, Gauteng. Grace Mavhiza, as the teacher of this class, implemented the intervention, while Maria Prozesky supported the development of the necessary pedagogy. The article hopes to contribute to a small but growing body of research on alternative pedagogies for poetry in the context of the South African public education system. Previous work has explored the effect of drawing on learners' multiliteracies (Newfield 2009; Newfield and D'Abdon 2015; Newfield and Maungedzo 2006), and of focusing on spoken-word poetry (D'Abdon 2016). These studies share the conviction that privileging the learners' own funds of knowledge is vital in promoting equity of access and social justice in education. Continuing along this trajectory, this study discusses the use of performance as a pedagogy, explicit discussion in the classroom of local lived traditions of oral poetry as poetry, and the introduction of learners' own writing of poetry in the classroom. We also explore how these tap into indigenous poetic elements and ongoing indigenous poetic traditions. As we discuss below, we understand the meaning of "indigenous", when applied to literature, as more complex than simply "originating or occurring naturally in a particular place" (Lexico 2020). In the pedagogical intervention we describe below, Grade 11 learners in a township school in Johannesburg performed poems they had written or selected, in any language/s they wished, on any topic of their choice, with explicit encouragement from the teacher to draw on izibongo and other forms of traditional poetry with which they were familiar. In striking contrast to the text-focused, close-reading poetry lesson so common in South African classrooms, these lessons were lively and unstructured, and produced real change in the learners' behaviour in their English classes. Our focus in this article is on the "pedagogical pathways" (Madden 2015, 2) revealed during the intervention: that is, the constraints and potentialities for a decolonial pedagogy that arise when the classroom is opened to indigenous poetry, and ideas for what such a decolonial pedagogy would look like.

The question of which poetry can be called "indigenous" is not simple, and the answers depend on how the term "indigenous" is understood. The relationship between indigeneity and decolonisation is also complex. We begin, therefore, with a discussion of indigenous poetry and how it can be defined in the educational context. Rejecting essentialist notions of indigeneity as defined by bloodline or "race", we work with a notion of indigenous identity as fluid and performative, and as inescapably entwined with coloniality. Such a definition allows us to understand what happened in the classroom, where, we argue, indigenous practices and identities emerged from the learners' performances. To further explore this emergence, we draw on understandings of all pedagogy as performative, since, in the interactions in the classroom, knowledge is built, stories told and identities sedimented. With this analytic framework established, we then briefly describe the intervention, and discuss the findings of our analysis of the poems the learners produced and performed. We discern a decentring of traditional classroom roles and practices, and a rethinking of the ethical role of the teacher in a decolonial pedagogy that seeks to bring to the fore indigenous poetry and identities.

Defining Indigenous Poetry

"Indigenous" is a contested term that cannot be reduced to the dictionary meaning of originating or occurring naturally in a particular place. The history of indigeneity as a concept is intertwined with that of coloniality and decoloniality. As Linda Tuhiwai Smith argues, colonisation is central to defining indigeneity:

[T]he world's indigenous populations belong to a network of peoples. They share experiences as peoples who have been subjected to the colonization of their lands and cultures, and the denial of their sovereignty, by a colonizing society that has come to dominate and determine the shape and quality of their lives, even after it has formally pulled out. (1999, 7)

She is sceptical of the arguments mounted by the descendants of colonisers, who claim indigeneity by right of birth but whose "linguistic and cultural homeland is somewhere else, [whose] cultural loyalty is to some other place" (1997, 7). Her argument, taken simplistically, would bar poetry written by South Africans of settler heritage from counting as indigenous. Such a view can seem to embrace an essentialist definition of indigeneity, reducing it to biology. In fact, by making the experience of coloniality an inextricable part of contemporary indigeneity, Tuhiwai Smith moves indigeneity onto what Nakata et al. call the cultural interface (2012, 130) and what Mignolo calls the border spaces (2000, 455). Nakata et al. see this interface as a space of contact between ongoing indigenous knowledge systems on the one hand, and, on the other, the multifarious forms of "Western knowledge presence" that reach every part of our globalised world. In this space, characterised by "the presence of both systems of thought and their history of entanglement and (con)fused practice", "contemporary Indigenous lifeworlds can now be understood and brought forward for analysis and innovative engagement and production" (Nakata et al. 2012, 26). Rather than an embodied essence, indigeneity then becomes a site of memory and of struggle, an ongoing commitment, a fluid performative identity under continual negotiation. Menezez de Sousa suggests thinking of this negotiation as happening at the level of "intra" (intra-national, intra-linguistic, and intra-cultural) rather than "inter" (international, inter-linguistic, inter-cultural) (2005, 75). In this understanding, "indigenous" poetry would include both traditional local forms and the products of ongoing creative engagement with local settler traditions and global influences. Working with this construction of indigeneity, what would matter in the poetry classroom then would be always choosing the preferential option for the indigenous, prioritising what Nakata et al. call "bringing forward" indigenous voices and viewpoints (2012, 26). This choice is an ongoing attitude that assumes different forms, depending on the positionality of the individual teacher and pupils, but which is always aware of the loci of enunciation (Mignolo 1999, 236) both in text and utterance. To speak of indigenous poetry in the classroom, therefore, is to speak of text and pedagogy as interlinked and inseparable, and always in the service of decolonisation. As Tuck and Yang starkly remind us, "decolonisation is not a metaphor": it means giving back the land, by which they mean submitting to, being beholden to the epistemology and cosmology of the first peoples (2012, 6). Ultimately, then, an indigenous pedagogy will need to be embodied in curricula through the choice of set works as well as the types of pedagogy and assessment prescribed.

Our definition of indigenous is not without problems, because what counts as indigenous and who has the right to police it are tricky questions, which we address in part in our discussion below. The definition does, however, imply a parallel definition of pedagogy that sees the classroom as a third space, to which learners and teachers alike bring their funds of knowledge (Moje et al. 2004).

Poetry in CAPS

In South Africa's CAPS, the teaching of poetry is addressed in terms that do not support indigenous poetry as we define it. On the one hand, the introductory section on "Approaches to teaching literature" does state that the personal response and interpretations of learners are absolutely necessary for studying literature, and that "[p]oetry should be taught, not poems" (DoE 2011, 12; italics in original), which could suggest drawing on learners' various poetic heritages in poetry teaching. The policy also states that "[c]reative writing should be closely attached to the study of any literary text", and urges teachers to "ensure that learners write poems as well" as reading them (2011, 12), which is the pedagogy used in our intervention. These points, which suggest openness to poetry as embedded in the lives and varied heritages of the learners, are, however, contradicted by the overall framing of poetry and poetry pedagogy in the curriculum statement. The introductory statement of the "Approaches" section reads:

The main reason for reading literature in the classroom is to develop in learners a sensitivity to a special use of language that is more refined, literary, figurative, symbolic, and deeply meaningful than much of what else they may read. (DoE 2011, 12)

This statement, which articulates only a partial truth about literature, talks of "a special use of language" in the singular, and so implies that literary language is unchanging across stylistic traditions, and cultural and linguistic contexts. The section on poetry is even more explicit about presenting poems as linguistic puzzles, meanings wrapped up in complicated language, saying "There are essentially only two questions a learner needs to ask of a poem: What is being said? How do I know?" The list of basic poetic techniques to be studied (DoE 2011, 23) is useful and not over-technical, but these devices are presented as "aspects" that will "enhance an understanding of the intended message" of the poem, again emphasising the poem as something dead on the page and to be dissected. At no point is poetry presented critically as embedded in cultural and literary traditions and entangled in real-world power imbalances. It is no wonder that many teachers fall back on a teacher-centred, line-by-line method of teaching and concentrate on set poems only, as Grace has found in her individual experience. In addition, as much as CAPS stipulates that there should be creativity in the literature classroom, the structure of the Annual Teaching Plan (ATP) makes such creativity almost impossible; the teacher is compelled to emphasise assessment, as this is the tool used by school management and subject facilitators to determine the work done in the classroom. Many teachers keep to a teacher-centred drilling of learners so that they fare well in the examinations.

Performance and Pedagogy

We draw here on Dimitriadis's notion of pedagogy as performance (2006). Dimitriadis looks to the "performative turn" in the social sciences, in which meaning is seen as contextualised performance, existing in the interactions between people and their social, material and cultural contexts (2006, 297). This "interactionist epistemology" leads to a specific understanding of pedagogy that decentres authoritative, static texts such as the curriculum and set works as guarantors of truth, and the privileged, delimited role of the teacher. In this view, "educators and students engage not in the 'pursuit of truths,' but in collaborative fictions-perpetually making and remaking world views and their tenuous positions within them" (Pineau 1994, 10 in Dimitriadis 2006, 305). When this "making and remaking" occurs in awareness of the cultural interface, and so brings forward indigenous knowledge and experience, it performs and sustains indigenous identities, and unbalances established colonial dynamics of power in the classroom.

The intervention we discuss in this article was an instance of this performative pedagogy. The teacher, working from her traditional privileged position and within the constraints of the highly prescriptive CAPS curriculum, defined the parameters of the group work project, so that the learners had freedom in creating and presenting their poems. The learners, working within these parameters, brought their varied knowledges and experiences to the task. At the intersection between these structures, the learners performed what Pineau calls "collaborative fictions", their lived understanding at that moment, as members of that classroom community, of what poetry is and who they are as poets. Herein lies the pedagogical opportunity for the teacher to witness indigenous identities being negotiated, to map the cultural interface on which these negotiations take place, and also to forward and sustain indigenous identities, poetry and practices. The teacher's own negotiations of indigeneity, whether from within indigenous heritage/s or from outside looking in, are included in this process.

We propose that the poems the learners produced, drawing on all the various genres with which they are familiar, are a type of personal narrative or "autoperformance": that is, a telling about and presenting of oneself. As Langellier and Peterson put it, this kind of narrative is "an elemental, ubiquitous and consequential part of daily life" (2006, 151), and it is more than just telling a story. As Bruner explains,

eventually the culturally shaped cognitive and linguistic processes that guide the self-telling of life narratives achieve the power to structure perceptual experience, to organize memory, to segment and purpose-build the very "events" of a life. In the end, we become the autobiographical narratives by which we "tell about" our lives. (2004, 694)

Because poetry mediates thought and experience into language in creative ways, it has an affinity for this kind of narrative (Wissman and Wiseman 2011). During the intervention, because the learners were given freedom to produce and perform their own original poems for their classmates and their teacher, we suggest they were given a particular kind of power, the "performative power ... to select or suppress certain aspects of human experiences, to prefer or downplay certain meanings, to give voice and body to certain identities" (Langellier and Peterson 2006, 152). These meanings included the learners' lived understandings of what poetry is and what it is for, as well as the identities of poet and performer, within the learners' embodied experience. The performance of the poems in this way is a site of interpersonal contact, where indigenous identities and meanings as we have defined them can appear and develop.

In any performance, a personal narrative is shaped by context, the material, social and cultural structures of meaning-including age, gender, class, "race", ethnicity, religion, and so on. These discourses provide both the raw materials for the performance, and the constraints within which it can function (Dimitriadis 2006; Langellier and Peterson 2006). In the poetry intervention, as will be discussed in more detail below, the learners drew on a wide range of cultural texts. The learners' performative power manifested in how they position themselves and others in terms of available discourses. In some instances, a telling can be conservative, re-presenting forms and conventions so as to stabilise social norms. In other instances, a performance is transgressive, defying cultural norms as unheard stories are told and domination resisted. This phenomenon is known as emergence, in which something that was unseen before comes into being (Conquergood 1998). This emergent potential means that performance can be political in the sense that it "ground\s] possibilities for action, agency, and resistance in the liminality of performance as it suspends, questions, plays with, and transforms social and cultural norms" (Langellier and Peterson 2006, 155). Our particular interest, in this article, is the decolonial potential of the intervention as it was performed by the teacher and learners, in the context of the poetry pedagogies that are overwhelmingly common in the South African public education system. By inviting the learners to bring their own compositions into the classroom, Grace opened the kind of liminal space that Langellier and Peterson describe. By explicitly addressing their preconception that "poetry" is only the written poetry prescribed at school, as we discuss further below, she opened the space to the indigenous, in the sense we defined earlier. In this space, the privileged status of written poetic texts in the Western tradition, and the "close-reading" style of analysis, can be destabilised, allowing the option of the indigenous as a real choice for both learners and teacher. The use the learners made of this space forms the findings section of this article.

Before the learners' poems can be examined, the context of their performances and the poetic repertoires at their disposal must be discussed. In keeping with our definition of indigenous, we begin with the local traditions of oral poetry. As Mignolo (2000) points out, historically under colonisation the coevalness of knowledge traditions (their equal ancientness and sophistication) was denied, and colonial regimes of knowledge and utterance were institutionalised through school curricula and practices. The teaching of indigenous voices in the South African poetry classroom begins with local oral traditions of poetry spoken or sung as part of the everyday life of indigenous peoples.

Traditions of Oral Poetry in South Africa

The poetic traditions of precolonial southern Africa, often referred to using the umbrella term "praise poetry", persist into the present in many diverging hybrid forms. As Groenewald puts it, "[i]f the praise poem is Africa's most characteristic form, it has gained this reputation by the sheer diversity of performance situations in which it occurs and its host of diverse types" (2001, 31). Praises can be spoken by men or women (Somniso 2008, 140), at occasions ranging from public gatherings (such as political rallies) and ritual events (such as weddings or initiation ceremonies), to private sexual encounters (Guma 2001, 275; Groenewald 2001, 31-32). They can praise chiefs (in IsiZulu, izibongozamaKhosi), private individuals (such as the dithoko recited by a young Basotho man after his initiation), animals or objects (as when a farmer praises his herd), young people (a mother's praises of her young children, izangelo in IsiZulu) or old ones (Gunner 1979; Gunner and Gwala 1991, 67, 79; Mtshali 1976, 200). In terms of form, all poetry distinguishes itself from other utterances by using language features that are accepted as poetic in a particular community. The features that mark praise poetry are not the rhyme and regular metrical structure that are often synonymous with Western poetry. Praise poetry is highly formulaic, and features repetition, parallelism, and highly figurative language, often with archaic vocabulary or words used only in poetry; as in poetry in other traditions, indirection rather than explicit statement of meaning is highly prized (Gunner 1979, 195; Kaschula 1995, 106). Gesture is important in the poetry's meaning (Gunner 1979, 239). In fact, praises are closely related to song, chant and dance (Gunner and Gwala 1991, 1; Mtshali 1976, 203). It is the function of praise poetry that distinguishes it most clearly from Western poetic traditions. The social practice of praising serves to mediate a person's individual and societal identities and define the individual in relation to the group or the community (McGiffin 2018). Praises in all their varied forms and occasions worked "to individualize, that is, to set the individual apart from all others, to build and maintain his or her austere character and position" (Groenewald 2001, 36), within the shared set of cultural meanings (Mulaudzi 2014, 91). An example of this mediation of the personal and the social is the chief s praise singer, who had a real political role in presenting and enhancing the chief s political image to the people (Groenewald 2001, 38), but also conveyed critique of the chief s actions back to him in a critically important form of "ritual license" to speak back to power. Kai Kresse writes: "Criticizing, as well as praising, is always linked to specific currently valid criteria which are rooted in social knowledge, marking what is laudable and what should be condemned" (1998, 172). The mediating function of praising is broad and complex.

These traditional functions of praise singing have shifted as the social contexts of performers and audiences have changed. Some practices survive in forms similar to precolonial tradition, as when children are taught their clan praises (izithakazelo in IsiZulu) as a form of social and cultural orientation (McGiffin 2018). Praises are also performed at functions such as weddings, funerals and presidential inaugurations, where their function can be mediatory in the traditional sense, but also purely "ceremonial", representing traditional culture as cultural capital and so marking the occasion as significant (Groenewald 2001, 38). Non-traditional forms of praise poetry, such as "worker poetry" performed at trade union gatherings, arose in the twentieth century (Kaschula 1995). Praise poetry certainly fed into the struggle poetry of the apartheid era, in English and other languages; as Kashula argues, the praise poet's role of criticising those in power made protest poetry a familiar genre (1995, 92). Struggle poets often collaborated with or were musicians themselves.

Praise poetry is only one type of poetry with which young people in today's Gauteng classrooms are familiar, to varying degrees. Another important form is found in popular culture, which in South Africa is highly influenced by American and, to a lesser degree, by European trends. In today's globalised world, TV and the Web give South African urban youth access to both whitestream colonial cultures and to what Nopece calls "[W]estern resistance identities and subcultures such as hip hop culture and music" (2018, 210). The learners' negotiations around whether and how they resist both global and local colonial culture are sites where indigenous identities and meanings, particularly in terms of poetry, are performed. The intervention classes taught by Grace aimed to open a space where these negotiations could become visible, and so the pedagogical pathways around indigenous poetry were also discernible.

The Intervention

This intervention is part of a larger study that explores the impact of including indigenous poetry in the English FAL classroom at Grade 11 level. Grace played a dual role, being simultaneously the teacher of the Grade 11 class chosen for the study and the lead researcher. Forty-three (45) learners in a single Grade 11 class participated in the study; they were aged between 16 and 19 years at the time the research was carried out. Their school is situated in Johannesburg South, Gauteng, and draws its 1 200 learners from the multilingual and multicultural township in which it is situated. Most (if not all) of the 11 official languages of South Africa are spoken in this community, but the school only offers three of them at home language level. These are IsiZulu, IsiXhosa and Sesotho for the Grade 11 class selected for this study. The learners take English as FAL (First Additional Language). Poetry is optional for Grade 11 according to CAPS, but the school selects this option. Once the school has opted to teach poetry, they use the poetry anthology that is prescribed by the Gauteng Department of Education, from which a selection of the poems is made by government course curriculum planners and passed on to the school.

The pedagogical intervention took place over five lessons in total, spread over several months. During the intervention, Grace took field notes of her observations. The intervention had three stages:

Orientation

The learners were given an overview of the intervention and assured that the tasks involved were not summative assessments. Grace then led the learners through an introductory exercise, in which they had to think about their poetry experiences outside school and share their ideas and experiences. The learners at first did not classify izibongo as poetry; they believed that the term applies only to the prescribed poetry they studied in their English classes. They called praise singing "entertainment", explaining that at home it is tradition that at family gatherings someone who is good at clan praises will entertain everyone by performing. When Grace pressed them to explain more about why izibongo are entertaining, the learners cited the performers' use of gestures, which make the performance lively, and the proximity of the izibongo to their lives, their daily successes and challenges. The class consisted of 43 learners from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, and Grace allowed them to work individually or in small groups as they chose.

First Round of Presentations: Personal Poetry

Learners then worked independently in their groups, at home or another chosen out-of-school space, to write or select a poem and prepare to present it for the class using the mode/s of their choice (an illustrated text, digital presentation, or live performance with optional artefacts). The learners were also told that they were free to use any language with which they felt comfortable. This freedom given to the learners was intended to support effective teaching and learning by building a culturally supported, learner-centred context, whereby the strengths students bring to school are identified, nurtured, and utilised to promote student achievement (Richards, Brown, and Forde 2007). The learners had four weeks to prepare their presentations. Over the course of two lessons, the groups presented their poems; all the groups, without exception, chose live performance as their mode of presentation. There were no set criteria for the order of presentation.

Second Round of Presentations: Prescribed Poetry

The learners worked in groups (6 groups of 6 learners and one group of 7) and Grace assigned each group one of two poems selected from the prescribed poems. One Western poem and one South African poem were chosen: "Composed upon Westminster Bridge" by William Wordsworth and "The Call" by Gabeba Baderoon. Three groups worked with the Wordsworth sonnet, while four groups worked with the Baderoon poem. The learners had to prepare a multimodal presentation as homework, and then present it as before, over the course of two lessons.

Findings

The texts produced by the learners and Grace's field notes and photographs were analysed, focusing on the indigenous poetic forms and practices, and wider constructions of indigenous identity, as performed by the learners. These are the landmarks of future pedagogical pathways that privilege indigenous tradition and expression and thus serve to decolonise classrooms.

Indigenous as Negotiated Performance

The learners' performances were sites of social interaction, in which the learners situated themselves as speakers relative to their immediate audience (teacher and classmates) and to wider implied audiences. The performances give insight into the identities from which and the communities to whom the learners are speaking, that is, the selves they are performing. We argue that the poems reveal some of the negotiations at what De Sousa (2005) calls the "intra" level of culture in terms of indigenous identity and experience.

As will also be discussed in the next section, the praise poetry tradition is present in the learners' repertoire. One boy who performed solo recited a long poem about his grandmother:

Grandmother

She wakes up early in the morning

Before the sun rise[s] to shine to work.

Work that she hates. But does she

Have a choice? No.

She does it for us

To sleep warm, full stomach.

But what do we do?

We don't appreciate.

The saddest part is when

She lost her eyesight.

After school I had to look after her

While other children are playing soccer

The thing I like. But did I

Have a choice? No.

For my grandmother to be happy

And to be taken care of.

I had to focus on my studies

And look after her. Nothing else.

I had to expect more

Than to rest.

One day she told me that

I will be rich

Because I suffered a lot

In my childhood.

The poem is in English, yet is reminiscent of praise poetry in its recounting of the subject's deeds, and its use of parallelism ("But does she / Have a choice? No" and then "But did I / Have a choice? No"). The poem also performs the traditional function of mediating social and individual identity, as the speaker works through his struggle to reconcile his duty to his family and his individual desires.

The boy's poem is a negotiation of indigenous poetic tradition through the lenses of colonial language and contemporary experience of home life in the township. A teacher needs intimate knowledge of such ongoing, daily negotiations, if s/he is to privilege indigenous knowledge and identities in the classroom. Other poetic traditions are clearly evident in the class's performances also. Two groups wrote poems with the simple diction, stanza structure and rhyme characteristic of pop song lyrics. Both these poems expressed motivational messages, with lines such as "Before you see the rainbow / Reach your goals" (group 4) and "Life is an opportunity, benefit from it" (group 6). These poems suggest the strong presence of Western popular culture in the learners' imaginations and identities, contributing both conventional, even trite, imagery and poetic form. Group 6's song is titled "Life", which it describes using highly conventional terms such as "dream", "struggle", and "adventure", but also in places manages to convey a young person's difficulty with understanding the world in language that is simultaneously evocative and inarticulate: "Let yourself be drowned by the strange / Be able to put up with the pain / Push harder than yesterday."

Several individual performances (by 3 boys and 1 girl, respectively) were love poems. This is not surprising, since the participants are at an age to be interested in romantic relationships. The girl who performed a love poem brought as her artefact a bracelet of Zulu beadwork (see Figure 1). Such beads were traditionally used to craft love letters that a young woman would give to a young man if she liked him. Traditionally it was seen as indecent for a young woman to speak her feelings towards a young man, a belief that is still widely held. If the young man returned her feelings, he would ask the young woman what the design with its various shapes and colours meant. In most cases the meaning would be shared only between the two people in the courtship relationship or marriage.

The learner's choice to bring beads to support her performance of a love poem suggests that among some Zulu people the practice is still meaningful. She was able to use an indigenous literacy practice, which employs a traditional multimodal textual form, the beads, to express hidden emotions. In this way, the intervention created an opportunity for indigenous literacies to enter the classroom space as valued knowledge. Yet the meaning and function of these literacies have changed, since the girl presents her beaded bracelet but then also recites a poem in a verbal expression of love that would be unacceptable from a girl in strict tradition. This is an example of the "intra-cultural" negotiations that Menenez de Souza describes.

Another love poem, recited by a boy, provides a further example of these intra-cultural negotiations. His poem depends more obviously on Western popular culture than on traditional practices. It features strong parallelism as is characteristic of izibongo, although also found in Western poetic tradition. The poem reads like the lyrics of a song:

I just close my eyes

Because I might see

Your beautiful face.

I just close my mouth

Because I might talk about you

I close my ear

Because I might hear your beautiful voice

But I can't close my heart

Because I love you.

The speaker is clearly in love, but seems uncertain as to whether his feelings are reciprocated. He wishes to keep his love secret to avoid embarrassment if the beloved does not love him in return. Though the poetic means on which he draws are in the linguistic mode and more clearly influenced by global popular culture, and so are different to the material and visual modes used by the girl with the beads, the social and personal experience they are negotiating, informed by cultural norms, is the same. Such intra-cultural negotiations, which the learners are making unconsciously every day, provide an opportunity for the teacher to guide the class in discussing the value and relevance of indigenous cultural knowledge. Such discussions, although they are a necessary component of any decolonial pedagogy, will not be simple or easy, because they raise the questions of what counts as indigenous and who can decide this. Involving elder members of the local indigenous communities who are indigenous knowledge holders and practitioners is probably necessary, for example in poetry workshops at school and ultimately in developing teaching materials and curriculum policy, to supply the depth of memory the young learners may lack. A decolonial pedagogy can at least ensure that learners engage in their fluid negotiation of indigenous meanings on the cultural interface with some critical awareness.

Indigenous as Political

The freedom the intervention created allowed the learners to move away from the constraints of the prescribed curriculum, and perhaps even ideas of what counts as "poetry". As discussed above, when the liminality of performance comes to the forefront, a personal narrative becomes a "political act" (Langellier and Peterson 2006, 155) in which the speaker tells him/herself as an agent who is capable of action. Several groups of learners, in their performances, situated themselves as active commentators on the difficult conditions of their lives as they play with the poetic discourses available to them. The first group to perform their own poem is an example. This was a group of boys who sang a song of their own composition in two lines:

Ubani onendaba ukhuti kwakusihlwa i phutu noshukela, (Who cares even if we eat thick porridge and sugar for dinner,)

Sivala iminyango nama fasitela akeko umuntu uzosibona ukuthi siyahlupheka. (We close our doors and windows so that no one sees that we are struggling.)

The boys accompanied their singing with a soft beat on a traditional drum (Figure 2) and danced as they sang, moving slowly and coordinating their hand gestures with the rhythm of the song. They composed the song themselves and called it "rap music". Rap is popular with the learners in the school and in the surrounding community, and this song shares the commitment to social commentary that is central to the genre. The boys defiantly name the reality of poverty, which shapes the experience of so many in their community, through a complex tapestry of elements drawn from different poetic traditions. The first line evokes poverty indirectly in the image of an evening meal of maize porridge with sugar or salt in the absence of any meat or relish. The second line of the poem is rooted in local discourses around reputation and shame, since it is an African custom to conceal it when there is trouble in the house. A complex social reality is expressed metaphorically in the image of closing the doors and windows of the home. The boys' use of a drum references the ubiquitous presence of this instrument in traditions across Africa as a means of communication, part of religious and ritual ceremonies and festivities, and as accompaniment to izibongo. The boys drew no specific attention to the drum: it simply meshed with their performance of themselves as makers of song and poetry, while at the same time they obviously did not see any incongruity in simultaneously claiming the identity of "rappers". In their confident mixing of local and global, the boys claim their right to tell of their lives on the cultural interface.

Other groups' performances were more normative in their treatment of political figures, and they also performed their understandings of what poetry is. Three separate groups produced what could be called contemporary izibongozamaKhosi in poems praising former South African president Nelson Mandela. The community around the school was the site of violent anti-government protests during apartheid and, in Grace's experience, the elders of the community still talk about how Mandela personally intervened to restore peace in 1993 when local resident and struggle hero Chris Hani was assassinated. A trio of boys performed their poem in English, using "The Shield", a metaphorical praise name for Mandela, as the title. The two other groups were all female, one of two girls and the other a larger group of eight. Like the first group discussed above, these groups' performances embodied the close relationship between poetry, dance and song in local oral tradition. The larger group first sang a song from the musical Sarafina and then one participant recited their poem while the others hummed in the background. Both groups used movements and gestures as they performed, notably lifting clenched fists in the black power salute that is familiar in South Africa's political history. The girls in the larger group drew a picture of Mandela in which he also raises his fist in the salute. Written above his head is the traditional call Amandla (Power); with the gesture both in the image and in the performed poem, this call immediately evokes the traditional response, Ngawethu (It is ours), and so casts the viewer of the girls' multimedia performance in the role of co-performer.

These poems, in their subject matter, form, and the gestures accompanying them, draw in more straightforwardly recognisable ways on praise-poetry traditions of political commentary and identity building. Both these praise poems and the "rap" song that preceded them, however, demonstrate an indigenous identity that is concerned with the power dynamics that define indigenous lifeworlds in South Africa: one speaks against the unequal socio-economic structures inherited from colonisation and apartheid, and the others perform the memory of a moment when unequal power structures seemed to shift. A concern with the political is a necessary element of any indigenous pedagogy, since in the logic of our understanding of indigeneity, such a pedagogy is always also committed to decolonisation. This political engagement is easier in South African classes such as Grace's, since such engagement is already integral to the praise-poetry tradition, on which teacher and learners can build together.

Indigenous as Embodied

All the poems, without exception, used a direct voice rather than creating a persona or telling a story. Langellier and Peterson emphasise that performance implies embodiment, in that the learners reproduce in their embodied performances, and on their own terms, the other genres and poetry texts they have heard (2006). This embodiment, in which the learners' voice sounds freely in the classroom, is in striking contrast with the kinds of poetry classes often observed in South African classrooms, where the written text of a canonical poem remains an inert object to be parsed by the teacher while the learners, taking notes, remain silent and invisible. After the first two intervention lessons, there were already some noticeable changes in the way learners received poetry. They started reciting poems daily before the beginning of a lesson. This joy was definitely emergent from the performative nature of the intervention classes. The prescribed poems, which were authoritative because they are required in the curriculum and because of their importance in the final assessments, were pushed aside for the moment. As Dimitriadis says, "decentering texts through the performative became a key way to open up new spaces for interrogating their roles and functions" (2006, 301). This decentering is an opportunity, again, for critical decolonial pedagogy.

It is a truism that learners respond better to poems that reflect lifeworlds with which they are familiar. Understanding the dynamics of the engagement, so that it can be more actively fostered and guided towards the indigenous, is more difficult. The second stage of the intervention, in which learners chose how to present a prescribed poem, suggests some answers. Once again, all the groups chose performance as their mode of presentation. The poem "The Call" (Baderoon 2005) addresses migration, a reality with which the learners are familiar. The speaker describes receiving a phone call from her mother far away in her home country. The learners responded to this poem in performances that depended on embodiment in different ways. First, one group dramatised the poem. Three group members took the parts of the mother, the daughter and the flatmate, and the three others acted as spectators. The actors used gestures and facial expressions with great intensity to convey the fraught emotional situation and the words remaining unsaid between mother and daughter. One of the girls presented with tears rolling down her cheeks. The rest of the class watched in a silence that spoke eloquently of the emotion raised by the performance. This reverberates with Lazar's assertion (1993) that poetry can stimulate the imagination of learners and increase their emotional awareness. By embodying the poem, drawing the gestures and looks needed to bring the words to life in the classroom, the learners translated the poem into meanings drawn from the repertoire of their lifeworlds. In this way they took a poem in English and found its resonance with their local, indigenous experience.

Another group did this transculturation even more richly. They began their presentation by singing a well-known song that mixes languages, titled "Here Come Our Mothers". The song was originally sung by Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and has also been widely publicised by the world music artist Daria. The presenters danced excitedly while chanting "Ngcibo" in IsiZulu: a nonce phrase that intensifies the meaning of surrounding words:

Here come our mothers bringing us presents

Ngcibo! Ngcibo! Nampayanomame! / (Sesotho: Nice treats/small gifts from mommy)

We can see apples, we can see bananas

Ngcibo! Ngcibo! Nampayanomame!

We can see cookies, we can see sweet things

Ngcibo! Ngcibo! Nampayanomame!

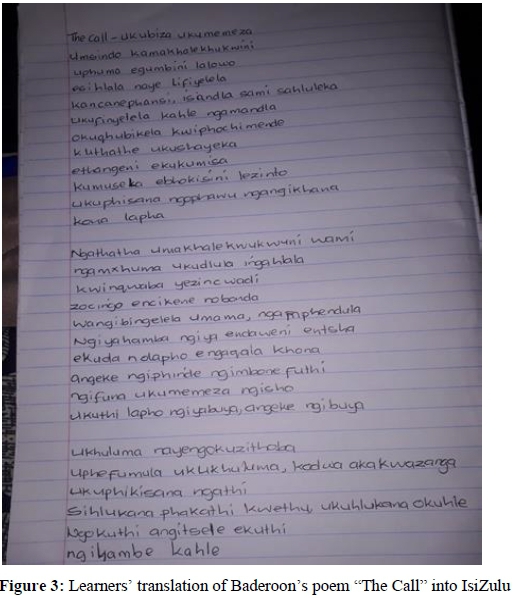

The whole class joined in the singing. After the song, two group members recited "The Call", while the others hummed in the background. The song about mothers, a familiar text, acted as a bridge to the prescribed poem. The learners created a genre somewhere between poetry and song and opened a shared space that was both intertextual and intermodal, in which they and their classmates could explore the meaning of the poem empathetically. The group then presented the poem translated into IsiZulu (see Figure 3).

This is an example of translanguaging, which Canagarajah (2011) and Makalela (2015) define as a shuttling between languages with learners using their home languages to understand the additional language content. Learners became innovative and extra careful, as they had to come up with words that could help them not to distort the original meaning of the poem. Their linguistic competence in their home language became a resource to help them in their creative decisions in crafting their translations. Grace's acceptance of multilingualism in the English FAL classroom enabled learners to realise that English is just a language like any of the languages they speak, which is the beginning of a freedom to critique linguistic coloniality.

Though the learners did show some enthusiasm for "The Call", they were not as free as when they presented their own poems, and this restriction was even more apparent with Wordsworth's "Composed upon Westminster Bridge". As had been the case with "The Call", the learners depended strongly on information discussed by Grace in class before preparing their performances. One group brought pictures of the real bridge that they showed the class, and this seemed to help the class, who all nodded their heads to show some understanding of the poem. Then the group played a video they had found on YouTube of the poem set to music and accompanied by visuals (Darling 2016). The whole class was excited and started dancing to the song, although it was not clear whether they were enjoying the poem or the music. The use of multiple modes, which the learners accessed on the internet using their phones, did seem to help them make meaning without the teacher's interference. But at the end of the presentations, the whole class started singing "Here Come Our Mothers" again; they seemed eager to return to familiar forms of poetry. Learners interacted with the two prescribed poems in different ways from the way they performed their own poems. With the prescribed poems, learners were trying to be more formal and conservative, but with their own poems, they were innovative and showed that they were in control of the information.

The contrast with the effortlessness of the learners' engagement with multimodal, embodied poetry, whether performing or interpreting it, suggests what Tuck and Yang (2012) call the incommensurability of decolonisation and the Western liberal tradition. When the learners' experience of poetry at school and their assessment depend on poems that are so foreign, as revealed in their struggle to perform them, they have to try to speak in a voice that is not theirs, that is colonial. There is a fundamental discord between the body speaking and the voice it is trying to speak in. A pedagogy that brings forward the indigenous should ultimately strive towards decolonising the curriculum, as well as classroom practice.

Indigenous as "Africanness"

The learners seemed aware of indigenous identity as rooted in the land. Two of the learners' poems were concerned with negotiating their identities as "African" and "South African". One group of boys presented a call and response poem titled "Africa", and as their artefact the participants had the South African flag (see Figure 4).

The text of the poem allows insight into these learners' sense of a communal identity, which lies somewhere between an indigenous rootedness to the land and a sense of Westernised national identity:

Africa you are so beautiful

You even have a flag

That represent[s]you, in my own understanding ...

Red stands for landmarks

Black stands for buildings

Blue stands for water

White stands for purity

Green stands for green plants and ...

Yellow stands for sunrise

The colours of the flag represent the logos of the three major political groups (the African National Congress, Inkatha Freedom Party and National Party) who came together to form the Government of National Unity in 1994. The participants reinterpret the flag, rooting their sense of South Africanness in the physical and natural world. Their creative freedom suggests a sense of identity that is more amorphous than allegiance to a particular party, or even a particular country, since they conflate Africa and South Africa in their poem. They invoke the land, but in terms that do not bring out any characteristic features that make the South African landscape unique. Many precolonial indigenous knowledge systems are relational in the sense that they emphasise "relationships between all life forms that exist within the natural world" (Kovach 2009, 34), and perhaps the boys' poem suggests a network of relationships that include history (the troubled "red" of the "landmarks"), the human world ("buildings") and nature (the "yellow" and "green"). The place of human beings in this network is not clear, however, and the speakers do not claim indigenous ownership of land, and all that implies in Tuck and Yang's sense. Their conception of indigeneity in these terms remains vestigial.

The second poem, titled "I Am an African", was performed by two girls, who sat cross-legged on a traditional reed mat (see Figure 5). Across southern Africa, mats often function as sitting places, especially for women and children in the home, and used to be used as beds. Izangoma (traditional healers) often sit on such mats during consultations.

This group' s multimodal performance using the mat suggests a more active negotiation of indigenous identity than the previous example, as they claim and embody an "African" identity characterised by objects and practices drawn from precolonial tradition. They claim this identity joyfully, ending their poem with the line "I am proud to say I am an African". The girls seem to be purposefully situating themselves as indigenous in the sense developed by Tuhiwai Smith, since their artefact is deliberately non-Western. Like the boys' group who performed before them, these learners seem aware of widely prevalent Pan-African discourses, which locate a "consciousness of belonging to Africa" in "collective historical experiences and memories of marginalization and socio-cultural and racial affinities" (Adogamhe 2008, 10). How the claims of different indigenous epistemologies and cosmologies on the vast African continent can be reconciled with such discourses is not clear, and would have to be negotiated in any indigenous pedagogy.

The Ethics of Pedagogy on the Cultural Interface

A performance pedagogy places the teacher, whether of indigenous or settler heritage/s, in a risky space, imbued with more fluidity than they may be accustomed to. In a classroom, the teacher is conventionally seen as more knowledgeable and has authority to guide the lessons. However, in Grace's classroom, she opened the classroom to learners' knowledge and experiences: in other words, she destabilised the traditional role of the teacher (Dimitriadis 2006) and took a risk that opened the Western, colonial curriculum and classroom dynamics to decolonial knowledge-making. This risk-taking had a complex effect on Grace as a teacher. First, her experience of the intervention highlighted the stress caused by the incommensurability of the poetry curriculum and the learners' lifeworlds. During the intervention, she found classroom management much easier, as the learners' motivation was high because they loved what they were doing. As a teacher in a highly stressful environment in the public education system, Grace found these poetry classes profoundly refreshing. The learners also experienced the curriculum as constraining; after the intervention, they insisted on performing at least one poem at the beginning of every English FAL lesson, which meant Grace had to sacrifice other classroom activities while still following the Annual Teaching Plan to ensure that learners were well-prepared for assessments.

Second, privileging the indigenous requires personal decolonial work for the teacher, whose positionality becomes significant: as a teacher of Zimbabwean Shona heritage, Grace became more aware of her cultural and linguistic repertoire and her own negotiations as an indigenous person. Occupying the role of adult and teacher in a class of young learners, she could not avoid having power over their performances, her ability to meet their poems with a "so what?" (Langellier and Peterson 2006, 159). Any indigenous pedagogy requires that the teacher be extremely aware of his/her power to decide what counts as indigenous in the classroom, which is a great ethical responsibility. All too often, in English classes in South African schools, the learners have experienced the epistemic violence of their indigenous cultures being silenced. If the teacher does not recognise or validate their stories, this can lead to further trauma and further silencing of the learners (Wissman and Wiseman 2011). The teacher's role is to accompany and guide the class as they make the negotiations between ongoing precolonial heritage on the one hand and global Westernised culture on the other: the teacher must maintain his/her self-awareness as s/he continually makes these negotiations.

Conclusion

Growing into an indigenous poetry pedagogy, which is necessarily a decolonial pedagogy, is an ongoing process for any teacher. It is also a pathway that is not clearly marked, because indigenous meanings and identities are under continual evolution. Our findings suggest the continued resilience of the praise poetry tradition in the learners' poetic repertoires, but also the strong presence of popular culture, and a way has to be plotted between them if ongoing indigenous poetic traditions are to survive. The first salient landmark on the pathway is the paradoxical role of the teacher, whose ethical commitment to bringing forward indigenous poetry, practices and identities cannot flag, even while his/her authoritative role must be abandoned to allow the learners' indigeneity its ongoing emergence in the classroom. At the same time, the learners' increased engagement and joy in poetry classes can support and rejuvenate the teacher's efforts. Going forward, the teacher could use similarities between izibongo and some forms in prescribed Western poems to help learners understand what other poets are doing when they write. The second guiding landmark is the decolonial political commitment that goes with any effort to bring forward the indigenous. Valuing and promoting indigenous poetry in the classroom must be accompanied by critique of the ongoing inequalities caused by coloniality, whether in the English FAL curriculum, the education system or the country more broadly.

References

Adogamhe, P. G. 2008. "Pan-Africanism Revisited: Vision and Reality of African Unity and Development". African Review of Integration 2 (2): 1-34. [ Links ]

Benton, P. 1999. "Unweaving the Rainbow: Poetry Teaching in the Secondary School". Oxford Review of Education 25 (4): 521-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/030549899103964. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. 2004. "Life as Narrative". Social Research 71 (3): 691-710. [ Links ]

Calway, G. 2008. "Don't Be Afraid: Poetry in the Classroom". NATE Classroom 4: 60-62. [ Links ]

Canagarajah, S. 2011. "Codemeshing in Academic Writing: Identifying Teachable Strategies of Translanguaging". The Modern Language Journal 95 (3): 401-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x. [ Links ]

Conquergood, D. 1998. "Beyond the Text: Toward a Performative Cultural Politics". In The Future of Performance Studies: Visions and Revisions, edited by S. J. Dailey, 25-36. Annandale, VA: National Communication Association.

D'Abdon, Raphael. 2016. "Teaching Spoken Word Poetry as a Tool for Decolonizing and Africanizing the South African Curricula and Implementing 'Literocracy'". Scrutiny 2: Issues in English Studies in Southern Africa 21 (2): 44-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/18125441.2016.1192676. [ Links ]

Dimitriadis, G. 2005. "Pedagogy on the Move: New Intersections in (between) the Educative and the Performative". In The SA GE Handbook of Performance Studies, edited by D. Soyini Madison and J. Hamera, 296-308. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976145.n16.

DoE (Department of Education). 2011. The South African National Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Farber, J. 2015. "On Not Betraying Poetry". Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition and Culture 15 (2): 215-32. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-2844985. [ Links ]

Finch, A. 2003. "Using Poems to Teach English". English Language Teaching 15 (2): 29-45. [ Links ]

Groenewald, H. C. 2001. "I Control the Idioms: Creativity in Ndebele Praise Poetry". Oral Tradition 16 (1): 29-57. [ Links ]

Guma, M. 2001. "The Cultural Meaning of Names among the Basotho of Southern Africa: A Historical and Linguistic Analysis". Nordic Journal of African Studies 10 (3): 265-79. [ Links ]

Gunner, E. 1979. "Songs of Innocence and Experience: Women as Composers and Performers of 'Izibongo', Zulu Praise Poetry". Research in African Literatures 10 (2): 239-67. [ Links ]

Gunner, E., and M. Gwala, eds. 1991. Musho! Zulu Popular Praises. Translated by E. Gunner and M. Gwala. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

Hanauer, D. I., and F. Liao. 2016. "ESL Students' Perception of Creative and Academic Writing". In Scientific Approach to Literature and Learning Environment, edited by M. F. Burke, 213-26. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamin. https://doi.org/10.1075/lal.24.11han.

Harris, K. 2018. "The Practice of Exemplary Teachers of Poetry in the Secondary English-Language Arts Classroom". PhD diss., Boston University. https://hdl.handle.net/2144/32689. [ Links ]

Jocson, K. M. 2005. "'Taking It to the Mic': Pedagogy of June Jordan's Poetry for the People and Partnership with an Urban High School". English Education 37 (2): 132-48. [ Links ]

Kaschula, R. H. 1995. "Mandela Comes Home: The Poets' Perspective". Oral Tradition 10 (1): 91-110. [ Links ]

Kresse, K. 1998. "Izibongo-The Political Art of Praising: Poetical Socio-Regulative Discourse in Zulu Society". Journal of African Cultural Studies 11 (2): 171-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696819808717833. [ Links ]

Kovach, M. 2009. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Langellier, K. M., and E. E. Peterson. 2006. "Shifting Contexts in Personal Narrative Performance". In The SAGE Handbook of Performance Studies, edited by D. Soyini Madison and J. Hamera, 151-68. London: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976145.n9.

Lazar, G. 1993. Literature and Language Teaching: A Guide for Teachers and Trainers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511733048. [ Links ]

Madden, B. 2015. "Pedagogical Pathways for Indigenous Education with/in Teacher Education". Teaching and Teacher Education 51: 1 -15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.05.005. [ Links ]

Makalela, L. 2015. "Translanguaging as a Vehicle of Epistemic Access: Cases for Reading Comprehension and Multilingual Interactions". Per Linguam 31 (1): 15-29. https://doi.org/10.5785/31-1-628. [ Links ]

McGiffin, E. 2018. "The Power of Poetry in South African Culture". Culturally Modified, January 7. Accessed January 7, 2018. https://culturallymodified.org/poetry-and-power-shaping-culture-in-south-africa/.

Menezez de Souza, L. M. 2005. "The Ecology of Writing among the Kashinawá: Indigenous Multimodality in Brazil". In Reclaiming the Local in Language Policy and Practice, edited by A. S. Canagarajah, 73-95. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Mignolo, W. D. 1999. "I Am Where I Think: Epistemology and the Colonial Difference". Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 8 (2): 235-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569329909361962. [ Links ]

Moje, E. B., M. Ciechanowski, K. Kramer, L. Ellis, R. Carillo, and T. Collazo. 2004. "Working toward Third Space in Content Area Literacy: An Examination of Everyday Funds of Knowledge and Discourse. Reading Research Quarterly 39 (1): 38-70. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.39.L4. [ Links ]

Mtshali, O. 1976. "Black Poetry in South Africa: Its Origin and Dimension". The Iowa Review 7 (2): 199-205. https://doi.org/10.17077/0021-065X.2083. [ Links ]

Mulaudzi, P. A. 2014. "The Communication from Within: The Role of Indigenous Songs among Some Southern African Communities". Muziki 11 (1): 90-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/18125980.2014.893100. [ Links ]

Nakata, M. N., V. Nakata, S. Keech, and R. Bolt. 2012. "Decolonial Goals and Pedagogies for Indigenous Studies". Decolonisation, Indigeneity, Education and Society 1 (1): 120-40. [ Links ]

Newfield, D. 2009. "Transmodal Semiosis in Classrooms: Case Studies from South Africa". PhD diss., University of London. [ Links ]

Newfield, D., and R. Maungedzo. 2006. "Mobilising and Modalising Poetry in a Soweto Classroom". English Studies in Africa 49 (1): 71 -93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00138390608691344. [ Links ]

Newfield, D., and R. d'Abdon. 2015. "Reconceptualising Poetry as a Multimodal Genre". TESOL Quarterly 49 (3): 510-32. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.239. [ Links ]

Nopece, U. 2018. "Linguistic (and Non-linguistic) Influences on Urban Performance Poetry in South African Contemporary Youth Culture". In African Youth Languages: New Media, Performing Arts and Sociolinguistic Development, edited by E. Hurst-Harosh and F. K. Erastus, 205-26. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64562-910.

OFTSED. 2007. Poetry in Schools: A Survey of Practice. London: HMI. [ Links ]

Riley, K. 2015. "Enacting Critical Literacy in English Classrooms". Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 58 (5): 417-25. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.371. [ Links ]

Richards, H. V., A. F. Brown, and T. B. Forde. 2007. "Addressing Diversity in Schools: Culturally Responsive Pedagogy". Teaching Exceptional Children 39 (3): 64-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990703900310. [ Links ]

Somniso, M. 2008. "Intertextuality Shapes the Poetry of Xhosa Poets". Literator 29 (3): 13955. https://doi.org/10.4102/lit.v29i3.129. [ Links ]

Tuck, E., and K. W. Yang. 2012. "Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor". Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society 1 (1): 1-40. [ Links ]

Tuhiwai Smith, L. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Wissman, K. K., and A. M. Wiseman. 2011. "' That's My Worst Nightmare': Poetry and Trauma in the Middle School Classroom". Pedagogies 6 (3): 234-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2011.579051. [ Links ]

Xerri, D. 2018. "Poetry Teaching in Malta: The Interplay between Teacher's Beliefs and Practice". In International Perspectives on the Teaching of Literature in Schools: Global Principles and Practices, edited by D. L. Goodwyn, 133-41. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315396460-13.