Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.24 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/7723

THEMED SECTION 2

ARTICLE

Towards Decolonising Poetry in Education: The ZAPP Project

Denise NewfieldI; Deirdre C. ByrneII

IUniversity of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. newfield@iafrica.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7248-6025

IIUniversity of South Africa. byrnedc@unisa.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4436-6632

ABSTRACT

This article concerns ZAPP (the South African Poetry Project), which is a community of poets, scholars (including the authors), teachers and students, established in 2013 to promote, in educational systems, the work of contemporary South African poets. For the past three years (2017-2019), we have attempted through outreach and research to contribute to decolonising South African education by paying attention to indigenous poetic traditions and practices. Our research has focused on content, pedagogy and institutional practice. The article outlines and attempts to assess three interrelated components of ZAPP's research into the decolonisation of poetry and education: our research into the transformation of teaching and learning in EFAL (English First Additional Language) poetry classrooms, our ongoing research into what constitutes indigenous South African poetry today, and our research into institutional practices concerning the production and dissemination of knowledge about poetry. We draw on various conceptual frameworks to explore ZAPP's research, namely, South African poetry scholarship, decolonial theory, theories of indigeneity, theories of multimodality, posthumanism and new materialisms. The article shows both the achievements and challenges of our research efforts in the three areas of content, pedagogy and institutional practice. Its final claim is that these three areas are crucial sites of intervention in attempts at decolonising poetry in existing disciplines in research and education.

Keywords: South African poetry; ZAPP; decoloniality; education; knowledge production; indigenous knowledge systems; indigeneity; multimodality; new materialism; posthumanism

Introduction

This article reports on the work of ZAPP (the South African Poetry Project), a collaboration among scholars (including the authors), poets, teachers and postgraduate students interested in poetry education. It is both an activist and a research project. ZAPP responds to the urgent call in South Africa, from 2015 onwards, to decolonise education by researching and promoting the work of South African poets in a variety of educational and public contexts. For us, as for Tuck and Yang (2012), "decolonisation is not a metaphor"; rather, ZAPP has attempted to decolonise poetry in education as a material practice of transformation, that is, through practical interventions. During 2017-2019, under the auspices of an NRF-funded project titled "Reconceptualising Poetry Education for South African Classrooms through Infusing Indigenous Texts and Practices", ZAPP undertook three research activities. The first concerns the teaching and learning of English poetry in secondary school English First Additional Language (EFAL) classrooms, where most learners are not first-language English speakers, but speak a number of African languages. Here we attempted to establish whether it was possible to infuse indigenous texts and practices into curricula and pedagogy. The second is more theoretical and concerns the question of indigeneity itself: what is indigeneity in relation to contemporary South African poetry in English? The third activity concerns the production and dissemination of knowledge about South African poetry within the academy.

Our approach-and our theoretical framework in this article-draws diffractively on scholarship in the fields of decoloniality (Grosfoguel 2007; Jansen 2017; Maldonado-Torres 2007; Mignolo 2007; Santos 2016; Tuck and Yang 2012), indigeneity (Fataar 2018; Msila and Gumbo 2017; Nyamnjoh 2012; Smith 2012), multimodality (Jewitt 2014; Kress 1997; 2010; Newfield and Maungedzo 2006; Stein 2008), posthumanism and new materialisms1 (Barad 2007; Braidotti 2013; Manning 2019; Taylor 2019). The term "diffraction" has been adapted from physics to refer to a research methodology and a way of reading. Diffraction is "a critical practice for making a difference in the world" (Barad 2007, 90). It does not set up "one approach/text/discipline against another" but rather invites a reading of the ideas of one framework or text through others (Bozalek and Zembylas 2018, 51). We diffract the above frameworks for the purposes of thicker understandings of complex phenomena, which cross the domains of literature, education, culture and politics.

The article begins by briefly discussing our chosen theoretical frameworks. After this, we outline our three research activities: in secondary schools, on the current poetry scene and the question of indigeneity, and concerning institutional processes of knowledge production and dissemination. In the first part, we narrate our unfolding relationship with a particular school as a case study of our research in schools. In the second, an ongoing project, we explain our methods of researching indigeneity in relation to contemporary South African poetry. In the third, we explore a particular instance of decolonising the production and dissemination of knowledge about poetry, namely, the colloquium. In conclusion, we sum up the achievements, challenges and failures of the project.

Theoretical Frameworks

The ZAPP project is an application to the field of education of common goals and principles of a group of studies that share an urgency to reconfigure ideas about political existence and about education, as mentioned above-decoloniality, indigeneity, multimodality, posthumanism and new materialisms. Our article draws on intersections across these fields, since, although they have different emphases and foci, they share a discontent with the status quo of knowledge production within and outside the academy. They all attempt to redress historical injustices, inequalities and marginalisations-political, cultural, social and economic.

Many decolonial thinkers aim to promote the decentring of colonial education-its epistemic and institutional structures-in order to complete the project of decolonising society (Kelley 2000, 27). Decolonial theorists such as Maldonado-Torres (2007), Mignolo (2007), Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2015) and Santos (2016) point to the epistemological effect of colonisation, which violently imposed European ways of knowing and thinking upon colonised people, resulting in "epistemicide" (the destruction of their own knowledge and cultures, Santos 2016). Accordingly, decolonisation entails delinking from Westernised epistemologies. Studies in indigenising education aim to decolonise curricula and practices by recentring the histories and ways of knowing of formerly colonised peoples, which have been erased, hidden or marginalised. Indigenisation works to restore cultural pride in indigenous ways of knowing (Gray and Coates 2010; Iseger-Pilkington 2011). The term "indigenous", nevertheless, is problematic. In our project, we consider it as necessarily plural, since there is a plurality of indigenous cultures in South Africa. Some scholars of previously colonised societies resent the trace of its disparaging usage in colonial discourse that it still carries (Barnard 2006; Smith 2012). Jansen considers the concept of "decolonisation" to have become a political slogan (adopted twenty years into South Africa's democratic transition by activist students who feel excluded from and alienated at universities) and requiring to be subjected to "critical review" by social scientists. Furthermore, the "retreat into indigenisation" indicates the "absence of vibrant, original and creative knowledge production systems in [South] Africa" and could suggest "a narrow Africanism" rather than an expansion of appropriate intellectual pursuits (Jansen 2019, 50-74). Likewise, Kalua (2019) stresses the debt that decoloniality owes to postcolonial theory, arguing that this means decoloniality is less original than is often claimed.

We acknowledge the contradiction in the attempt to decolonise English as a discipline, given its provenance in colonial education, as Ngügï argued powerfully at the Makerere Conference of 1962 (Ngügï 1986, 5-7). English, having been imposed by the colonial regime on education, administration and commerce, and having given way to Afrikaans during apartheid, has regained dominance in the post-apartheid era. While acknowledging the merit of objections such as these, ZAPP situates itself within the project of decolonisation as a necessary attempt at redress and transformation. Its research investigates whether, to what extent and how decolonisation may be achieved through indigenisation of a particular curriculum and its concomitant practices.

Multimodal approaches aim to promote scholarly and educational attention to the full range of representational resources and platforms, in line with the changing communicational landscape, which has decentred language. Thinking and knowing are held to occur in a range of modes, including the visual, bodily, sonic and spatial, in addition to language. In particular, they emphasise the way many modes are orchestrated in complex multimodal representations and communications, as in the diverse forms in which South African poetry is materialised (Newfield and d'Abdon 2015). Studies applying multimodal pedagogies in EFAL contexts have shown the positive results of broadening the repertoire for teaching and learning (Newfield and Maungedzo 2006; Stein 2008). The question of orality is crucial in South African narrative and poetic traditions (Gunner 2004; Finnegan 2013; Kaschula 2012; Scheub 1998), which are retrieved and reconfigured in the present South African poetry scene. We consider much current poetry to have its origins in orality, for example, in its izibongo, izithakazelo and amaculo, praise poems and songs, which are hybridised today with popular global cultural forms, such as hip hop and rap, and South African urban forms, such as kwaito (see Newfield and d'Abdon 2015).

Posthumanist and new materialist approaches reject humanism's claim that humans are the measure of all things; they reject human exceptionalism and individualism (Barad 2007; Braidotti 2013; Bozalek et al. 2019). Instead they assume the relationality of all matter and a flattened ontology-human, non-human, animal, material-in the past, present and future, as well as in different geographical contexts, a relationality demonstrated by the 2020 coronavirus phenomenon. Relationality entails "intra-action", which is preferred to "interaction" in order to highlight the inseparability of people, objects, events, actions, "doings" and "becomings"-all are entangled (Barad 2007). These approaches take account of ethics and ontology as well as epistemology, and are responsible and "response-able" (Barad 2007; Bozalek et al. 2019; Haraway 2012) to the inequalities in society. Haraway reconfigures the usual concept of "responsibility" as "response-ability", which is "a praxis of care and response ... in ongoing multispecies worlding on a wounded terra" (2012, 302).

Affect, a concept that derives from Spinoza, is central to ZAPP's research framework, and is implied in the above studies. It is a critical notion in decolonising pedagogies, which value the "warm current" of desire, "indignation and the will to resist" (Santos 2016, 26). Referring to a non-personal, non-cerebral energy or force that can bring about change, affect is linked to the "non-cognitive and non-volitional expressions of life, including feeling, animation, tactility and habituation" (Roelvink and Zolkos 2015 in Kuby et al. 2019, 185). A form of productive power or "potentia" (Braidotti 2013, 136), a capacity to act or be acted upon (Braidotti 2013, 55-57, 166-7; Kuby et al. 2019, 1856; Massumi 2015), affect is manifest in education (Sousa 2016). It animates classrooms and may be evidenced in individual or group motivation or engagement, or lack of them, with concomitant results for learning or lack of it.

Together, studies in these areas make a strong case for reconfiguring education in an ethical and situated manner, being open to new ideas and response-able to the other, whether that other be conceptualised from a human, cultural, epistemological, semiotic, material or planetary perspective. In addition, they privilege an approach to education that is not only cognitive, but holistic, conceiving of teachers and learners as "intra-acting"2 in multidimensional, complex, entangled relationships, contexts and histories.

Research in Schools: A Case Study

This section reports on our investigation into whether, and to what extent, it is possible to decolonise the curricula and pedagogies involved in teaching and learning poetry in EFAL classrooms. We chose six secondary schools in Gauteng and the Western Cape as our research sites. Space does not permit us to embark on a full discussion of our activities at all six schools, so one school is presented here as a case study. We use our chosen theoretical frameworks to shed light on the impact of our developing relationship with the school. Theories of decoloniality and indigeneity illuminate features of educational practice that need to change in order to bring about social justice. In particular, they draw our attention to elements of curricula and pedagogies that carry traces of colonial investments. Our decolonising agenda motivated us to strive to subvert these through infusing elements of indigenous material and pedagogical practices into the school. Our multimodal framework points to the fact that poetry occurs in multiple modes (such as graphic, oral, performative, and digital) and not only through the written word. In this way, it highlights the single, narrow approach to the way poetry is taught in formal classrooms. Our posthumanist and new materialist theoretical affiliation specifies that the school's geographical location, material and educational resources and its community of teachers and learners are not mere background information, but are, instead, components of the complex intra-actions that co-constitute the enterprise of teaching and learning, where material-discursive3 phenomena are entangled. Applying these frameworks diffractively directs us to attend to many features of the school's situation and teaching practices that are crucially pertinent to the teaching and learning of poetry.

The school is a well-functioning peri-urban school in the township of Soshanguve. Both teachers and learners are proud of its historical legacy; they also express satisfaction at the school's excellent pass rate in the National Senior Certificate (NSC) examinations (92% in 2018). South African schools are assessed and ranked on this statistic, which is a performative marker of the matriculation phenomenon. Education in the South African schooling system is an example of the sedimentation and performativity of relations of power and knowledge. Teachers hold knowledge, while learners do not. The type of knowledge held by teachers is premised on political interests, as may be discerned in the curriculum and in classroom pedagogies; apartheid interests still remain evident in the unequal distribution of material-discursive resources among schools. The school where we carried out our research possesses resources, such as classrooms, teachers, blackboards, desks and chairs, but is not as well-supplied with textbooks as it might be: there is, for example, only one copy of the prescribed poetry textbook in the school. The single textbook is a material object, but its scarcity results in practices such as copying and distributing copies of poems, and increases its value. In a better-resourced school in a more affluent area, every learner would receive a textbook and would thus become acquainted with the resources they need to pursue intra-actions associated with learning.

The school is located in an area of the township that is characterised by brick-and-mortar housing and tarred roads. Nevertheless, its reputation for high academic standards attracts learners from less well-resourced communities. Many of these learners arrive at school without having had breakfast, and without food, because of poverty. Hunger disables learning, creating an affective current of deprivation. The school's social justice mandate to redress inequalities and enable the learners to learn has led the management to enter into a contract with a local catering company to bring cooked food to the school daily.

We had two aims in our work at the school. First, we intended to explore the culture of teaching and learning poetry. Our second aim, which we thought far more important and time-consuming, was to decolonise the school's poetry curriculum and pedagogies through infusing indigenous texts and practices into the teaching and learning of poetry. In this way, we intended to assist in "[living] the African ideals by (among others) reflecting the indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) in education" (Msila and Gumbo 2016, iv). As the existing lists of prescribed poems for Grade 10 and 11 are out of date in relation to the current poetry scene,4 we intended to demonstrate practically that contemporary South African poems would prove more relatable for learners and would evoke better responses in written and oral work. We also intended, in line with decolonial pedagogies that build on a Freirean "pedagogy of the oppressed" (1968), to subvert the established hierarchy of power relations in classrooms through encouraging teachers to use learner-centred pedagogies, which are "linked to wider social movements promoting social reform and egalitarianism" (Schweisfurth 2013, 9).

With this in mind, we observed what happens in classrooms when poetry is taught. Most lessons unfolded with the teacher reading the poems aloud to the learners and then telling the class about the texts. Questions posed to learners tended to be closed, allowing learners only the option of answering "yes/no" or completing the teacher's sentences. The intra-actions in the classroom were very formal. They positioned one agent (the teacher) as firmly in charge of knowledge, while all the rest were positioned as passive receivers. The dominant modes in the classrooms were oral and written. Poems were taught mainly as texts on pages. They could be read aloud, but not performed: the oral was subsumed into the written. The classes did not provide space for multimodal understandings of poetry, or for learners to express creative responses to the poems. Under apartheid, education typically did not require sophisticated thinking from black learners; they were only required to memorise content. There has been a shift in contemporary South African secondary school education in the post-apartheid era, where slightly more analytical questions are asked in examinations, but a pass mark still depends more on memory of content than on critical thinking.

Figures of speech, where language functions at the slippery edges of meaning, combining, weaving and entangling sense, affect and paradox, were presented as technical aspects of poetry, which have a regular structure and use in poems. This is in contradistinction to Liz Gunner's account of the way figurative language in praise poetry functions to encode ambiguity and hybridity (2004). In order to understand figures of speech in poetry classrooms at our research site, learners only needed to memorise the technical aspects of their construction and apply these to particular cases. They were neither required nor encouraged to engage with the indefinable and polysemous aspects of language, which are the special qualities of poetry. If this were encouraged in the classroom, the humble metaphor or simile could become a vehicle for learners to take charge of their own learning and begin to decolonise the dominant pedagogies at the school.

The rigid teacher- and content-centred approach that dominates pedagogies of teaching and learning poetry is materialised in the CAPS (Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement) document, issued by the Gauteng Department of Education. CAPS instructs teachers about what they should teach in each section of the curriculum. It divides the curriculum into weekly sections, with instructions about what skills the learners should practise and how they should be assessed in each section. CAPS has material-discursive effects, producing oral and written intra-actions in classrooms that model its authoritarian approach. Teachers' intra-action with prescribed poems varies depending on their level of interest in the genre, which itself is circumscribed by their experiences at tertiary education level where the goal of teacher training is to instil a colonial model of "analysis" in the teachers so that they can pass it on to their learners. "Analysis" is a rigid and predetermined form of intra-action with a text, derived from British critics such as F.R. Leavis (1948) and I.A. Richards (1924). It is designed to elicit repeatable responses from learners that can be assessed unambiguously. The school's success rate in the NSC determines how desirable the school is to new learners. Teachers benefit, therefore, from teaching learners to answer questions in assessments and examinations "correctly".

In order to encourage a decolonised, indigenised and multimodal approach to teaching and learning poetry, the research team conducted workshops with teachers after school. In one particular workshop, we demonstrated that poems could be explored, dramatised, represented visually, transliterated into emojis or understood as calls to action. The teachers listened politely and found these approaches to their prescribed poetry creative, but clearly not a substitute for analysis. Our attempt at decolonising the curriculum through two approaches-introducing more contemporary South African poetry that draws on indigenous traditions and shifting the power balance in classrooms to make teaching more learner-centred-was unsuccessful. This was due to the pressure on teachers to get through the curriculum and produce assessments in which learners demonstrate their mastery of "correct" answers to the kinds of questions asked in examinations.

Learners did not respond enthusiastically to the pedagogical approaches used in most poetry lessons at the school. They understood that the teachers were under pressure to teach and train them to do well in examinations, but they found this approach "boring". A strikingly different affect was apparent in the school's vibrant Poetry Club. This meets once a week after school and is "coached" by the head of the English Department. She is no longer a "teacher"-where her role is that of a gatekeeping authority-but a "coach" who works with the learners to co-create themselves as poets. The Club is led and run by learners, who have, in this way, decolonised the space so that it is conducive to self-directed learning. Meetings are devoid of the formality that pervades classroom teaching; yet, there is respectful turn-taking and members' contributions are met with appreciation. Poetry is experienced as praxis, not as curriculum; to be done, not to be trained in. Finally, in the Poetry Club, poetry is indigenous-written by and for learners-and multimodal, being performed in gestures, vocal intonations and in collaboration with the audience.

On one occasion, the school attempted to participate in a national inter-school poetry competition supported by ZAPP (Poetry for Life), where learners were required to memorise and recite two poems from the online competition list: one from the European list and one from the list of contemporary South African poems selected by ZAPP researchers. The participants from the school willingly memorised a poem from the European list, but, against the rules of the competition, they recited poems they had written instead of prescribed South African poems. Such was the enthusiasm for creativity generated in the Poetry Club.

Unfortunately, our project to decolonise and indigenise poetry curricula and practices in secondary school EFAL classrooms was hamstrung by structural intra-actions of unequal power. "Authorities", whether at provincial or national administrative levels, or in classrooms, prescribe not only what shall be studied but how it is to be studied. The curriculum places teachers under so much pressure to complete tasks and assessments that there is little opportunity for learners to exercise either critical thinking or holistic learning choices. While this may lead one to conclude that we are back in the Foucauldian world of producing "docile bodies" (Foucault 1975, 136), this would not account for the material-discursive aspect of classroom practice, where the entanglement of educational policy, material resources, bodies that are not provided with the requirements to flourish, and a narrow view of poetry as "text" all co-contribute to an overly cerebral experience of poems as arcane, difficult and (preferably) to be avoided.5 This is an unfortunate legacy of colonial understandings of school education, which may take longer to undo than ZAPP's three years of engagement. Opportunities for learners to take control of their own learning do exist, nevertheless, and are taken up by learners outside classrooms, in corridors and in the Poetry Club.

The Contemporary Poetry Scene and the Question of Indigeneity

The second component of ZAPP's activity, which is still in process, concerns contemporary South African poetry and the question of indigeneity. Our research, as previously mentioned, is limited to poetry in English, or predominantly in English, in alignment with the terms of the research project. ZAPP probes the question of indigeneity in three ways: using extant scholarship in the fields of poetry and indigeneity, doing fieldwork research though attendance at spoken word gigs, festivals, poetry launches, broadcasts and other events to familiarise ourselves with the field of poetry as social praxis and as text, and conducting interviews with knowledge holders and practitioners6 in the field of poetry.

Scholarship on indigeneity and indigenisation informs our consideration of whether South African poetry in English can be considered indigenous or not, and, if so, to what extent, given the paradoxical position of English in relation to indigeneity (see, for example, Brand 2004; Fataar 2018; Msila and Gumbo 2017; Ngügï 1986; Nyamnjoh 2012). The question of indigeneity at the present time remains open, raising more questions than it answers. Does "indigenous" imply African? If so, is only poetry composed by black Africans "indigenous" or can the category be expanded to include poetry focused on Africa, African themes and cosmologies? Is poetry produced by politically subjugated groups, such as South African Indians (the descendants of indentured labourers brought to the colony by the British under false pretences between 1860 and 1911) indigenous, as Govender asks (2019)?

Motivated by a new materialist emphasis on doing, on praxis, rather than on interpretations-following Deleuze and Guattari's injunction not to ask what something means but what it does (Alaimo and Hekman 2008, 3; Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 4)-ZAPP has researched the field of performance. Some of its questions are: What role does poetry play here? Whom does it serve? What does it do? What are poetry collectives and why are they popular?7 What are the platforms for poetry? ZAPP has attended many live poetry performances, including poetry and jazz sessions at the now-defunct Orbit Jazz Club in Johannesburg (curated by Myesha Jenkins and Natalia Molebatsi), various iterations of the annual Word N Sound spoken word competition, poetry slam competitions hosted by Current State of Poetry, launches of poetry collections by Busisiwe Mahlangu, Gabeba Baderoon, Phillippa Yaa de Villiers, Makhosazana Xaba, Vangi Gantsho, Danai Mupotsa, Arja Salafranca, Raphael d'Abdon and others, poetry performances by Malika Ndlovu, Toni Stuart and the InZync Poetry collective at the Open Book Festival in Cape Town, and numerous other events. The enthusiastic reception of these events testifies to the affective and political power of poetry: "Writing and sharing poetry shows us that we are not alone in our experiences of the world and opens us up to experience the world of another. In doing so, it helps us to develop compassion" (Stuart in Xaba 2019, 156).

In addition, ZAPP has embarked on a series of in-depth interviews with indigenous knowledge holders and practitioners in the South African poetry community. These aim to elicit their views on indigeneity in their own poetry and in the contemporary poetry scene more broadly. A preliminary analysis reveals that the poets hold widely divergent views. For some, indigeneity involves tapping into knowledge and practices that are embedded in cultures in multimodal and multi-sensory ways. Poets such as Pitika Ntuli, Vangi Gantsho and Phillippa Yaa de Villiers derive strength for their creative endeavours from their relationship with ancestors, including poetic foremothers and forefathers. Other poets regard indigeneity as referring, instead, to specific geographical locations, such as the Cape Flats or Soweto. The interviews still need to be completed and fully analysed.

Decolonising Institutional Practice: The Case of the Colloquium

As previously stated, our project's aim is to contribute to the national project of decolonising texts and practices in disciplines and institutions, working through praxis. Disruption and transformation rather than the overthrow of established curricula, pedagogies and institutional practices pertaining to the study of English has been the goal. Zembylas (2018) speaks of "twisting" the practices deriving from Eurocentrism and Eurocentric forms of knowledge, and this is an apt term to describe our actions. We have tried to decolonise the list of poems studied in EFAL classrooms through expansion and indigenisation, as outlined in an earlier section of this article. This section discusses our attempt to "twist" a specific institutional practice concerned with the dissemination of poetry knowledge, namely, holding a colloquium. To exemplify this, we use "Decoloniality and Indigeneity in Poetry and Education", organised by ZAPP at the University of the Witwatersrand in July 2019.

A colloquium is an academic gathering at which leading scholars read papers on a particular theme or topic, which are then opened up for discussion and critique. It is a standard Western event of high status in educational institutions. Distinguished experts in a field are invited to read scholarly papers to a group of fellow experts, who may be members of a particular interest group. The Rousseau Colloquium held at Trinity College, Cambridge, UK, in 2010 serves as a representative example. The Colloquium proceedings read: "A dozen specialists were invited to read papers to an audience of about a hundred other scholars interested either particularly in Rousseau or in the 18th century in general, who discussed the papers with their authors" (Leigh 2010). This approach is followed by most Westernised institutions in the world today, including in Africa, although a loosening up of restrictions and movement to digital platforms have recently been evident. Modifications to the strict, standardised features of the traditional colloquium by the colloquium on "Decoloniality and Indigeneity in Poetry and Education" will be examined below through the lenses used in ZAPP as a whole.

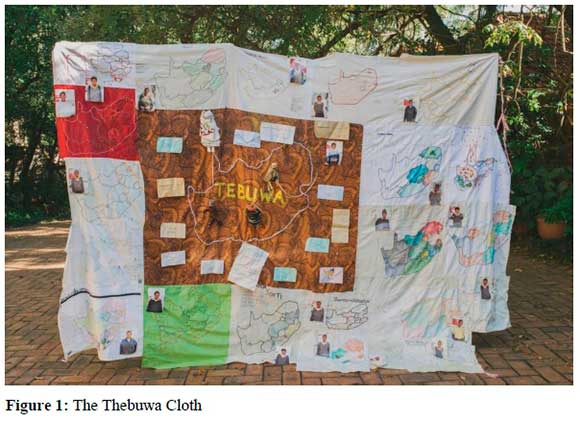

The Colloquium demonstrated ZAPP's aim to reconfigure ways of knowing through a reclamation of hidden or marginalised forms and structures. This aim is implied in the design of its programme cover, which features the Thebuwa Cloth, a three-metre multimodal wall hanging produced by South African learners in a township school (Figure 1).

Utilising language and other representational modes, the cloth integrates contemporary poems in English and traditional poems in African languages with other cultural practices such as cloth-making, embroidery, photography and cartography (see Newfield 2014; Newfield and Maungedzo 2006). The Colloquium programme included 25 presentations by a diverse range of speakers from all over South Africa, in line with ZAPP's aim of bridging divisions, dismantling unequal colonial power relations, acknowledging and overturning historical privileges enacted in the academy: in short, advancing democratic education. The Colloquium sought to close gaps between the haves and have-nots and to remove white supremacy; it sought to recognise, listen, apologise, develop capacity, repair, heal and celebrate across racial, gender, class and cultural divisions.

How was this done? And what made one of the delegates exclaim during the final discussion, "This was a decolonised colloquium"?8 The outline below explores features that may have given rise to this evaluation.

The first feature is an inclusive, polyphonic space, which brought out from the shadows what might be called indigenous knowledge and its practices through placing on the platform not only illustrious professors, but also poetry practitioners and holders, who did not necessarily hold postgraduate degrees from or prominent posts at universities.

The first of the three main addresses was given by poet Malika Ndlovu, who performed a 40-minute suite of poems about identity, power, oppression, pain and trauma in South Africa in an alternative, poetic way of presenting knowledge. The second was Pitika Ntuli, the patron of ZAPP, a poet who writes in five of South Africa's 11 official languages. He demonstrated the poetic nature of language through improvising a series of multilingual jazz riffs on key phrases given to him by the audience. The third was Leketi Makalela, a distinguished professor of language, who provided us with a scholarly exposition of decolonising principles and pedagogies for multilingual classrooms, which included, importantly, "translanguaging".9 In addition to recognised poetry and education scholars, the Colloquium presenters included teachers and other educators, emergent researchers, postgraduate students, poets and youth. All were acknowledged as valid knowledge holders, given space to disseminate their views and responded to as respected contributors to the Colloquium. In this way, the usual, ring-fencing conventions were abandoned and hierarchical power relations in the holding of knowledge were unmoored.

The design of the physical space and forms of delivery were multimodal and indigenous. They served to decentre written language, not overthrow it, since written language remains a central communicative format for poetry along with spoken word. They also orchestrated language with other modal forms to create an expanded sensory experience. The visual dominance of the Thebuwa Cloth, displayed on a metal frame, was complemented by specially commissioned sketches of South African poets on the walls.10 Being attentive to the politics of space, we sought to arrange the seating differently from that in university auditoria where formal rows of fixed seats face a podium. Inspired by the Kgotla,11 we arranged the chairs in a U-shape to facilitate discussion.

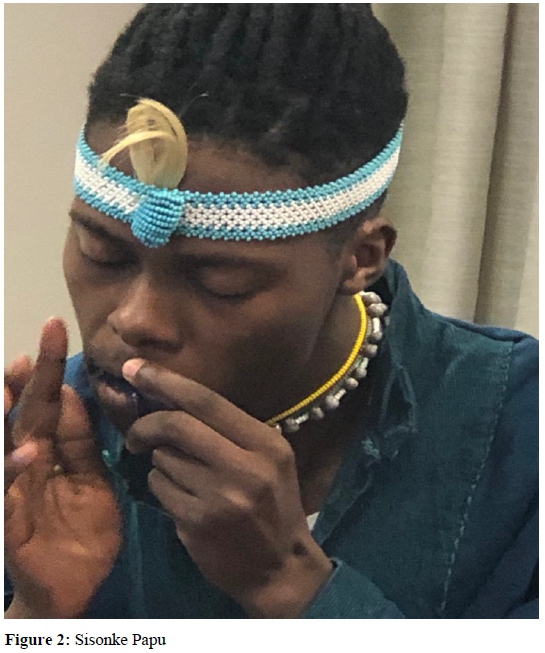

The format of the papers varied from papers and panels to poems accompanied by music, and from read papers to live performance. Thus, the theme of decolonising poetry education was not debated in a purely rational and cerebral way, but drew on African traditions of orality and of multimodal cultural production. The Colloquium thus acknowledged different ways of knowing and different ways of disseminating knowledge, apart from the conventional and cerebral ways of the Westernised academy. The Colloquium was a pluricultural event, representing a range of different forms of cultural production and knowledge dissemination in South Africa's different communities. Indigenisation was signified by the spatial arrangement of the venue, as well as by dress and stance (Hebdige 1979). One presentation opened with the burning of impepho as an injunction for healing, and later included the plucking of an isitolotolo (a form of Jew's harp) as part of a suite of poems (Figure 2).

The style of engagement was another decolonising feature. Eurocentric formality, conventionally associated with power and status, and manifested in self-promoting forms of linguistic sophistication, can have an intimidatory and exclusionary effect on audiences. The organisational style of the Colloquium was inclusive, warmly welcoming rather than coldly formal and distant, non-hierarchical. Chaired with a light hand, rather than presented in the carefully circumscribed ways of the white male expert, the Colloquium invited the participation of all attendees. Lively discussion was generated through affective and emotional as well as intellectual input and output.

The vexed and much-debated question of language in decolonising multilingual countries such as South Africa hung over the Colloquium. If removing English as the medium of dissemination of knowledge is required for decolonisation, this did not happen, because the ZAPP project locates itself within the discipline of English. English therefore remained in its pole position, functioning as a lingua franca, in spite of differing mother tongues for the presenters and delegates. However, the multilingual character of the South African nation was evident throughout both the formal presentations and the discussions through vibrant threads of African language usage and themes.

In this section we have highlighted the features that intra-acted (Barad 2007, 33) and sparked a decolonising circuit of affect in the Colloquium. Affect, which played a key role, was a transforming force, propelling and propelled by the above features. It was a kind of electrical circuit of motivation and energy, felt in the Colloquium as a whole, reconfiguring it. Affect activated and was activated by the intra-action of all the components constituting the Colloquium assemblage12-human, technological, discursive, epistemological, cultural, historical and social. Affect enabled the flow of connections between the ideas, experiences, emotions, memories and modes of delivery of presenters and delegates. In its context of de-hierarchised interaction, affect bonded the participants into a community. It also moved them forward in their different journeys of scholarly "becoming" as poets, speakers, researchers, performers, educators and theorists. The Colloquium was a "doing" (Barad 2007, 135, 178), a dynamic process of knowing and becoming, of empowerment, in contra-distinction to the disempowerment that can occur in the face of arrogant performances by competitive and individualistic speakers.

Conclusion

This article has outlined three components of ZAPP's research into the decolonising of poetry education. Its research into curricula and pedagogies relating to poetry in EFAL classrooms has shown the immense difficulty of infusing indigenous texts and practices into South African EFAL classrooms. The pressures of an overstuffed curriculum and of the need for success in the final matriculation examination-from heads of departments in the schools, line managers, including local and national Departments of Education-thwarted our attempt to make decolonising inroads into formal classrooms. On the other hand, spaces outside classrooms, such as the Poetry Club, were hives of poetic creativity and learning, thoroughly enjoyed by all. ZAPP's ongoing research into the nature of indigeneity in South African poetry today reinforces the fact that decolonisation and indigenisation of poetry are happening outside formal environments. The actions of poets on stages, no less than on pages, storm the bastions of what counts as "poetry", reconfiguring it as a dynamic, multimodal phenomenon with many dimensions. We celebrate the actions of poets in reconstituting and practising poetry in ways that serve them. The Colloquium unsettled the colonial certainties of what counts as knowledge, what can contribute to knowledge and how that knowledge is disseminated. It troubled what it means to be an expert and in whom expertise is constituted, twisting colonial relations of "race", privilege and power. It had a strong ethical dimension, ethics understood not in the abstract but as an embodied practice, a materialisation of a commitment to social justice.

The ZAPP project as a whole is motivated by "an ethical call to shift modes of being, doing and thinking" (Taylor 2018, 95) as redress for past wrongs, erasures and marginalisations. It speaks from the corners, the edges and thresholds of experience and the academy. It attempts to be life-giving to teachers, learners, and students, and to promote the work of contemporary South African poets. This has been a daunting and at times insurmountable challenge. On the other hand, in its diffraction of activism and research, ZAPP may be seen as a practical endeavour to decolonise and indigenise pedagogic and institutional practice. Along with the difficulties, it has opened up a range of possibilities for EFAL classrooms. It has also fostered mutually enriching collaborations between the academy and the outside world.

In the words of Lebohang "Nova" Masango:

Africa

Never again will I throw your name around

Like an old excuse

I vow to reclaim all that honours

The origin of we without fear

Bloodied but never broken

We are still here

(Masango, "To Do List for Africa", 2019)

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Research Foundation for their support of this project, Grant 105159. We also thank our wonderful ZAPP team with whom we have enjoyed stimulating and pleasurable times.

References

Alaimo, Stacy, and Susan Hekman. 2008. Material Feminisms. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Baderoon, Gabeba. 2019. "Introduction". In Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets 2000-2018, edited by Makhosazana Xaba, 1-9. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822388128. [ Links ]

Barber, Karin. 1997. "Views of the Field". In Readings in African Popular Culture, edited by Karin Barber, 1 -11. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Barnard, Alan. 2006. "Kalahari Revisionism, Vienna and the 'Indigenous Peoples' Debate". Social Anthropology 14 (1): 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2006.tb00020.x. [ Links ]

Bozalek, Vivienne, Tamara Shefer, and Michalinos Zembylas. 2018. "Introduction". In Socially Just Pedagogies: Posthumanist, Feminist and Materialist Perspectives in Higher Education, edited by Vivienne Bozalek, Rosi Braidotti, Tamara Shefer and Michalinos Zembylas, 1-9. London: Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350032910.0006.

Bozalek, Vivienne, and Michalinos Zembylas. 2018. "Practising Reflection or Diffraction? Implications for Research Methodologies in Education". In Socially Just Pedagogies: Posthumanist, Feminist and Materialist Perspectives in Higher Education, edited by Vivienne Bozalek, Rosi Braidotti, Tamara Shefer and Michalinos Zembylas, 47-58. London: Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350032910.0006.

Brand, G. v. W. 2004. "'English Only'? Creating Linguistic Space for African Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Higher Education." South African Journal of Higher Education 18 (3): 27-39. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v18i3.25478. [ Links ]

Braidotti, Rosi. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Cambridge Polity Press. [ Links ]

Govender, Arushani. 2019. "Exploring a South African Woman Poet and her Poetry from an Indigenous Perspective: Interviews with Francine Simon and Readings of Selected Poems from Thungachi". MA diss., University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Gray, Mel, and John Coates. 2010. "'Indigenization' and Knowledge Development: Extending the Debate". International Social Work 53 (5): 613-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872810372160. [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, Ramon. 2007. "The Epistemic Decolonial Turn: Beyond Political-Economy Paradigms." Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 211-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162514. [ Links ]

Hebdige, Dick. 1979. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Iseger-Pilkington, Glenn. 2011. "Branded: The Indigenous Aesthetic". Artlink 31 (2): 39-41. [ Links ]

Jansen, Jonathan, ed. 2019. Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.18772/22019083351. [ Links ]

Jewitt, Carey, ed. 2014. The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kalua, Fetson. 2019. "The Resonant Asset: Exploring the Productive Investments of Postcolonial Theory in the Face of Decolonial Turns". English Academy Review 36 (2): 49-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10131752.2019.1665256. [ Links ]

Kaschula, Russell. 2012. "Towards an Integrated Model for the Teaching of Oral Poetry". South African Journal for Folklore Studies 22 (1): 29-47. [ Links ]

Kelley, Robin D. G. 2000. "A Politics of Anticolonialism". In A Discourse on Colonialism, by Aimé Césaire, translated by Joan Pinkham, 7-28. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

Kress, Gunther. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203970034. [ Links ]

Kuby, Candace R., Karen Spector, and Jaye Johnson Thiel, eds. 2019. Posthumanism and Literacy Education: Knowing/Becoming/Doing Literacies. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315106083. [ Links ]

Leavis, F. R. (1948) 2015. The Great Tradition. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. [ Links ]

Leigh, R.A., ed. 2010. Rousseau after 200 Years: Proceedings of the Cambridge Bicentennial Colloquium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Makalela, Leketi. 2016. "Ubuntu Translanguaging: An Alternative Framework for Complex Multilingual Encounters". Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 34 (3): 187-96. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2016.1250350. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. 2007. "On the Coloniality of Being". Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 240-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162548. [ Links ]

Manning, Erin. 2018. "Me Lo Dijo Un Parajito-Neurodiversity, Black Life and the University as We Know It". In Socially Just Pedagogies: Posthumanist, Feminist and Materialist Perspectives in Higher Education, edited by Vivienne Bozalek, Rosi Braidotti, Tamara Shefer and Michalinos Zembylas, 97-113. London: Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350032910.ch-007.

Masango, Lebohang "Nova". 2019. "To Do List for Africa". Accessed November 30, 2020. http://www.poetryforlife.co.za/index.php/anthology/south-african-poems/78-to-do-list-for-africa.

Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822383574. [ Links ]

Mignolo, Walter. 2007. "Introduction: Coloniality of Power and Colonial Thinking". Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 155-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162498. [ Links ]

Msila, Vuyisile, and Mishack T. Gumbo, eds. 2016. Africanising the Curriculum: Indigenous Perspectives and Theories. Stellenbosch: Sun Press. https://doi.org/10.18820/9780992236083. [ Links ]

Moumakwa, Piwane C. 2010. "The Botswana Kgotla System: A Mechanism for Traditional Conflict Resolution in Modern Botswana. Case Study of the Kanye Kgotla." MA diss., in Philosophy of Peace and Conflict Transformation: University of Tromse. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo. 2015. "Decoloniality as the Future of Africa". History Compass 13 (10): 485-96. https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12264. [ Links ]

Newfield, Denise. 2014. "Transformation, Transduction and the Transmodal Moment". In The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis, 2nd ed., edited by Carey Jewitt, 100-14. London: Routledge.

Newfield, Denise, and Robert Maungedzo. 2006. "Mobilising and Modalising Poetry in a Soweto Classroom". English Studies in Africa 49 (1): 71-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00138390608691344. [ Links ]

Newfield, Denise, and Raphael d'Abdon. 2015. "Reconceptualising Poetry as a Multimodal Genre". TESOL Quarterly 49 (3): 510-32. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.239. [ Links ]

Ngügï wa Thiong'o. 1986. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. London: James Currey and Heinemann. [ Links ]

Njamnjoh, Francis B. 2020. "'Potted Plants in Greenhouses': A Critical Reflection on the Resilience of Colonial Education in Africa". Journal of Asian and African Studies 42 (2): 129-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909611417240. [ Links ]

Richards, I. A. (1924) 1960. Principles of Practical Criticism. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203278901. [ Links ]

Santos, Boaventura Sousa. 2016 "Epistemologies of the South and Future". From the European South 1: 17-29. [ Links ]

Schweisfurth, Michele. 2013. Learner-Centred Education in International Perspective: Whose Pedagogy for Whose Development? London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 2012. Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Stein, Pippa. 2008. Multimodal Pedagogies in Diverse Classrooms: Representation, Rights and Resources. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203935804. [ Links ]

Taylor, Carol A. 2018. "Each Intra-action Matters: Towards a Posthuman Ethics for Enlarging Response-ability in Higher Education Pedagogic Practice-ings". In Socially Just Pedagogies: Posthumanist, Feminist and Materialist Perspectives in Higher Education, edited by Vivienne Bozalek, Rosi Braidotti, Tamara Shefer and Michalinos Zembylas, 8196. London: Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350032910.ch-005.

Xaba, Makhosazana, ed. 2019. Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets 2000-2018. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

1 Posthumanism and new materialisms are two interlinked areas of theoretical engagement, which we draw on in this article.

2 A neologism used by Karen Barad to signify "the mutual constitution of entangled agencies" (2007, 33), in contrast to the more common "interaction".

3 The term "material-discursive", used in new materialism, does not point to the fact that "there are important material factors in addition to discursive ones" but to "the conjoined material-discursive nature of constraints, conditions, and practices" (Barad 2007, 152). For example, the kinds of resources allocated to a particular school may be material things such as desks, books and chairs, but these are the effects of political ideas, agendas and policies that are discoverable only in discursive manifestations.

4 As an example, although four of the seven Grade 11 prescribed poems are South African, these are drawn from canonical works published in the previous century.

5 This is borne out by the fact that the school has elected not to study poetry for the NSC examinations for fear of decreasing their pass rate.

6 These terms refer to South Africa's drive to reclaim indigenous knowledge. The National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa established a domain of Indigenous Knowledge Systems. In our project, elders, who receive and transmit indigenous knowledge, are seen as knowledge holders. Younger poets, who draw on these traditions, are seen as knowledge practitioners.

7 The past half-century has seen the rise of numerous poetry collectives, including WEAVE, Feela Sista!, the Botsotso Jesters, InZync Poetry, the Current State of Poetry, Lingua Franca and the Mzansi Poetry Academy.

8 Horwitz, Allan Kolski, Johannesburg poet and publisher.

9 Translanguaging is a feature of language use in multilingual contexts; it is also a pedagogy that contests monolingual bias in literacy teaching and learning, and instead valorises alternation within and between languages by teachers and learners (see Makalela 2016).

10 These were commissioned from portrait artist Marco Bucceri.

11 The traditional Kgotla is a community gathering where Batswana chiefs and headmen discuss legal cases and matters of public interest, and where all are allowed an equal chance to speak. "The seating arrangement signifies the equality in the Kgotla" (Moumakwa 2010, 53).

12 "Assemblage" is a translation of the French agencement, a collection of things which have been assembled, arranged or laid out. For Deleuze and Guattari (1987), who popularised the term, the component parts of an assemblage are not fixed and stable but can be displaced and replaced. Our use of the term implies a collection of different components that interact, intra-act and connect in fluid and shifting ways.