Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.24 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/5974

ARTICLE

Legitimation of Poverty in School Economics Textbooks in South Africa

Jugathambal RamdhaniI; Suriamurthee MaistryII

IUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Ramdhanij@ukzn.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1401-6463

IIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Maistrys@ukzn.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9623-0078

ABSTRACT

In South Africa, the school textbook remains a powerful source of content knowledge to both teachers and learners. Such knowledge is often engaged uncritically by textbook users. As such, the worldviews and value systems in the knowledge selected for consumption remain embedded and are likely to do powerful ideological work. In this article, we present an account of the ideological orientations of knowledge in a corpus of school economics textbooks. We engage the tenets of critical discourse analysis to examine the representations of the construct "poverty" as a taught topic in the Further Education and Training Economics curriculum. Using Thompson's legitimation as a strategy and form-function analysis as specific analytical tools, we unearth the subtext of curriculum content in a selection of Grade 12 Economics textbooks. The study reveals how power and domination are normalised through a strategy of economic legitimation, thereby offering a "legitimate" rationale for the existence of poverty in the world. The article concludes with implications for curriculum and a humanising pedagogy, and a call for embracing critical knowledge on poverty in the South African curriculum.

Keywords: poverty; critical discourse analysis; ideology; legitimation; textbooks

Introduction

The South African school curriculum is based on the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), a policy framework that prescribes key content and skills that all South African learners should acquire before exiting the schooling system. A key challenge though is the bifurcated nature of the schooling system, with two distinct sectors: one, a small but well-functioning middle-class sector comprising well-resourced, functional schools with qualified personnel, and the other, a large dysfunctional schooling sector that services poor and working-class children (Spaull 2013). In both contexts, the school textbook (derived from the CAPS framework) continues to be an indispensable source of content knowledge. This article examines the worldviews on the content topic "poverty" that are transmitted to South African high school learners (both affluent and indigent) through the subject of Economics. In other words, it considers what legitimisations of "poverty" as studied conceptual knowledge manifest overtly, what subtexts they convey, and how critical discourse analysis (CDA) might unearth ideological persuasions not readily discernible to the untrained eye. As a point of entry into this article, a brief discussion of the state of global and South African poverty is offered with a view to contextualising this investigative focus.

The state of poverty in the world is such that half the global population is still mired in severe poverty and has access to less than 2% of the world's wealth. Because of this extreme inequality, one third of our world's population dies prematurely due to severe poverty (Pogge 2010). When an economy experiences prosperity, people who have material wealth generally do not concern themselves with those who are less prosperous. The theory of warm-glow philanthropy appears to explain the dominant motivation for why the rich disburse funds to the poor (Andreoni 2006). In such times, people also find it easy to accept the neoliberal belief that an economy adopting a market-driven approach and a social welfare system, together with a strict work ethic, can make an individual more prosperous (Lucio, Jefferson, and Peck 2016). While Erler (2012) asserts that the discourse on the plight of poor people draws on narratives that emphasise structural and contextual elements more than psychological and moral ones, neoliberal discourses foreground the individual as primarily responsible for her plight (Harvey 2007).

A prominent manner in which poverty is constructed and argued for is through the use of an economic discourse (see Avalos 1992; Bedard 1989; Bundy 2016; Minujin and Nandy 2012). This may refer to how economic systems create barriers for the poor to access institutions in society that offer, among others, employment, schooling, shelter, healthcare and security. Barriers to "gain economic power to achieve change" (Bradshaw 2007, 11) prevent economic advancement that could otherwise occur through "redevelopment, business attraction or enterprise zones" (Bradshaw 2007, 8) and entrepreneurship. It might also include "structural failings" (Bradshaw 2007, 12) of economic systems as well as constraints that prevent individuals from "making choices and investments" (Bradshaw 2007, 12) to maximise their well-being. Arguments against social welfare to assist the poor, systems that limit opportunities and resources to gain income and economic security, and capitalism or free enterprise that encourages unemployment and low wages through segregation of the poor also form part of economic discourses that posit a particular understanding of poverty (Bradshaw 2007, 12). The legitimisation of poverty using economic discourses is evident in the reliance on factors such as individual responsibility, structural limitations, discriminations within the economic system, and social welfare and globalisation. These economic discourses might stem from a neoliberal rationale that encourages individuals to become active players in the market, satisfying their own needs and accepting responsibility for their own economic problems (Lucio, Jefferson, and Peck, 2016).

Arguments that move beyond the individual point to structural limitations as preventing the poor from gaining access to the world of work and economic emancipation (Albrecht and Albrecht 2000). The economic system is designed to make it difficult for the poor to achieve economic independence (Bradshaw 2007). Economic-related reasons for poverty are attributed to the limitations caused by discrimination on the grounds of "race" and gender, and the segregation that resulted from economic changes after World War II (Albrecht and Albrecht 2000). The cyclical nature of poverty also suggests that patterns of inequality tend to repeat themselves over time (Pacheco and Pultzer 2008). Despite these repeated patterns, Pogge reminds us that the international response has not been successful in disrupting this persistent repetition (Pogge 2010). He is critical of institutional reports on poverty, suggesting that the report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, which declares that over one billion people are chronically undernourished, is not treated with the gravity it deserves, especially when the World Bank asserts that its progress in eradicating poverty is "impressive" (Pogge 2010, 4). The world will not make real progress against poverty unless powerful advocates commit themselves to eradicating it (Pogge and Sengupta 2014).

In South Africa, poverty levels increased from 2011 to 2015 (Lehohla 2017). Since 2011, poverty levels have risen from 53.2% to 55.5% in 2015, which amounts to a staggering 30.4 million people who are deemed poor. While documented statistics on poverty are available in various forms and several theories and explanations are proffered, there is little research on how poverty is constructed in school textbooks used to teach economics to South African learners. It is concerning that Streib, Ayala, and Wixted (2017) have found that poverty and social class inequality are portrayed in the media as "legitimate" and as "appropriate and fair" (2016, 1). They assert that the media portrays poverty and class inequality, particularly in children's movies, as "benign" (16). Poverty is framed as non-threatening. Such portrayals are problematic because they mask the realities people are exposed to in their lives (Streib, Ayala, and Wixted 2017). The extant field of poverty theory is expansive. For a critical discussion of contemporary theories, see Ramdhani (2018), and David Brady's (2019) very recent synthesis of the key causes of poverty in which he classifies theories of poverty into three main categories, namely, behavioural, structural and political.

Research Problem

While statistical data on poverty are available, the extent to which poverty is understood and how it is interpreted, as well as the specific definitions presented for public consumption, are still uncertain in the South African context. Poverty as a content topic features in the subject Economics in the Further Education and Training Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS). CAPS offers a skeletal description of key topics and sub-topics to be taught. The textbook serves as an important source of disciplinary knowledge on topics such as poverty. In this article, we report on a study that examined portrayals of poverty in contemporary school economics textbooks in South Africa.

The Department of Basic Education (DBE) recognises the textbook as an effective resource for ensuring uniformity in content coverage. In the Action Plan to 2014: Towards the Realisation of Schooling 2025, the DBE (2011) emphasised the importance of ensuring that every learner has access to textbooks and that teachers are required to use textbooks in the teaching process. However, this emphasis on the textbook policy pays minimum attention to the ideological messages embedded in textbooks' content. Although textbooks play an important role in schools, they are not impartial resources (Apple and Christian-Smith 1991; Williams 1989). The concept of a "selective tradition" is used to describe how compilers of textbooks decide to include certain meanings and to omit others (Williams 1989). The content selected is then passed off as "the tradition [or] the significant past", thereby retaining the dominance of a specific set of power relations both in the economy and in the political institutions of society (Apple and Christian-Smith 1991, 3). Studies on ideological underpinnings in economics textbooks have been rare. Early research focused on the readability of economics textbooks (Gallagher and Thompson 1981; McConnell 1982). A study of introductory economics textbooks over a 10-year period (1974-1984) by Feiner and Morgan (1987) revealed the under-representation of women and minorities in the textbooks, a phenomenon also confirmed by Robson (2001). Some later research on economics textbooks focused on how specific topics such as economic dumping (Rieber 2010) and entrepreneurship (Phipps, Strom, and Baumol 2012) were framed as content to be studied.

In the only study that dealt specifically with depictions of poverty, Clawson indicates that the portrayal of poverty in economics textbooks was dominated by depictions of poverty among black people (Clawson 2002). The gap that this article wishes to address relates to the rationales for the existence of poverty that are presented in South African school textbooks, teaching artefacts that are derived from prescriptions in the South African school curriculum.

As a political institution of society, the South African Ministry of Education views education as a means to eradicate poverty, as can be seen in the rhetoric used to state the goals of the National Development Plan (DBE 2016). The ministry contends that the eradication of poverty is inhibited by economic constraints (DBE 2016). The education sector notes severe poverty among children and declares a commitment to addressing this poverty within schools. Severe poverty, however, persists, especially in the African community. A dualistic schooling system still exists within the education sector (Spaull 2013). One caters for the wealthy that is functional, while the other is for the poor and, in many instances, is dysfunctional (Spaull 2013, 14). That schoolchildren (including millions who are poor) are the recipients of state-sanctioned knowledge (via textbooks) on poverty presents a complex and compelling problematic, namely, discerning specifically what ideological legitimisations of poverty are packaged for consumption by South African learners.

In essence, the research problem that this article attempts to address arises from the multiplicity of possible explanations of poverty that prevail, the fact that this topic/concept is taught to a large section of South African learners who are in fact victims of poverty, and that there is limited knowledge of what strains of poverty theory permeate the programmatic curriculum (school textbooks) for South African learners. While we note that concepts such as economic development or inequality could well have been the research focus, these appear as broader, overarching, meta topic areas in the school economics curriculum, whereas "poverty" is foregrounded as a key economic phenomenon signalled for mandatory in-depth study.

A Brief Methodological Note

This study drew on the tenets of critical discourse analysis (CDA), which, according to McGregor (2003), has its roots in Habermas's (1973) Critical Theory. It allows us to understand the issues that plague societies dominated by mainstream ideology and power relationships. Conventional ideology and power relationships are preserved and maintained by the words and language in texts (McGregor 2003). For the purposes of this article, we adopted the perspective of ideology as described by Thompson (1990, 58), who explains that meaning underpinned by "symbolic forms serves to establish and sustain relations of domination". This article recognises that symbolic forms encompass a wide array of "actions and utterances, images and texts, which are produced by subjects and recognized by them and others as meaningful constructs" (59). The linguistic utterances and expressions written, in this regard, in the textbooks mask the representations of power, hegemony and the social construction of poverty. We extracted the meaning behind these utterances using "form-function analysis", "language in context analysis" and "situated meaning analysis" (Gee 2005, 54-55). The intention of CDA is to reveal the socio-political assumptions embedded in the language found in text and oral speech (for a detailed account of CDA tools of analysis of language, see McGregor 2003).

CDA is a theoretical tool used to "make sense of the ways in which people make meaning in educational contexts" and to "answer questions about the relationships between language and society" (Rogers et al. 2005, 373). Because "language is a social practice", and because not all habits, customs, or traditions in society are treated equally, it is imperative that we investigate how language is used to construct certain realities (Rogers et al. 2005, 367). The tools adopted in language can be located "everywhere" and are always "political" (Gee 2005, 1). The word "political" refers to "how social goods are thought about, argued over and distributed in society" (Gee 2005, 2). Our world "is constantly and actively being constructed and reconstructed" (Gee 2011, 29). The term "politics" is used to explain the distribution of social goods to certain people, groups and institutions at the expense of others (Gee 2011, 31). It is important to note that CDA is not without its critics. It is often criticised for being too exploratory, interpretive and politically motivated and lacking the rigour that quantitative protocols for empirical research offer (Flick 2009).

In this article the mode of analysis employed attempts to ascertain the legitimation strategies (Ferguson et al. 2009; Thompson 1990) used by textbook writers to legitimate poverty in the selected textbooks. Legitimation is the act of making something lawful and authorial, and illustrates how certain worldviews become considered "right and proper" (Tyler 2006, 376). Three techniques are typically used to legitimate preferred positions. The first, rationalisation, is where power relations are justified because reasonable explanation/s can be provided (Ferguson et al. 2009, 897; Thompson 1990, 62). The second strategy is that of "universalisation" (Ferguson et al. 2009, 897; Thompson 1990, 62). Here, the interests of a few are projected as the interests of all. The concept of legitimacy is built on the conviction of a "common interest" that goes beyond private and partial benefits (Easton 1965, 312-19; Gilley 2006, 502). The third strategy is that is of "narrativisation", in which past "traditions and stories" are offered as treasures to be cherished. These three strategies work in concert to legitimise certain value positions.

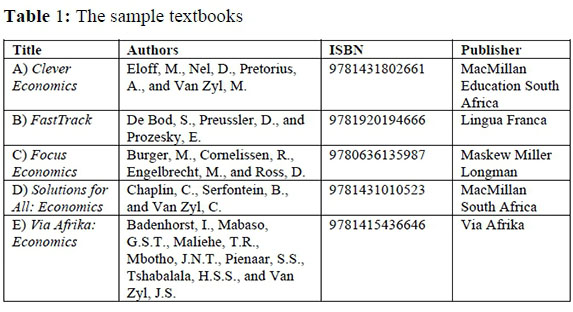

The table below shows the textbooks sampled for this study. These Grade 11 Economics textbooks were in use at the time the study was conducted and were sanctioned by the DBE.

With regard to ethical issues related to this study, due University of KwaZulu-Natal ethical clearance protocol was followed. As the textbooks are in the public domain, there was no necessity for gatekeeper permission that might apply to other empirical studies.

In the section that follows, we present one aspect of the findings of the larger study, namely that of economic legitimation as it relates to the manifestation of poverty as a concept. This brief methodology section describes the methodological approach from a meta-level. It must be noted that a systematic sorting and coding of data from the corpus of five textbooks was undertaken. For explicit details of the research protocol followed for the entire study, see Ramdhani (2018). For the purpose of this article, sample data that are germane to the argument we make have been selected and presented.

In the section that follows, legitimation strategies used by the selected economics textbooks are presented.

Economic Legitimation of Poverty through the Strategy of Rationalisation

In the five economics textbooks, the theme of rationalisation emerges through various themes and sub-themes. These include the following: discrimination in the economic and social systems, structural limitations, individuals bring on their own problems (deficit of need for achievement, genetically poor intelligence, laziness and irresponsibility), the effects of globalisation, access and proximity to resources, capitalism and low wages, prices of goods and a lack of infrastructure.

Discrimination in Economic and Social Systems to Rationalise Economic Legitimation of Poverty

The findings reveal that the economic system provided the foundation for discrimination (see sample data of independent and dependent clauses below). This is evident in Book A, Book B, Book C, Book D, and Book E. Below are extracts from the texts with form-function analysis:

Despite all efforts, income distribution is still not equitable [independent].

A mixed economy still faces problems of unemployment, inflation and business cycles.

Workers are still exploited in the private sector [independent]. This contributes to income inequality, increased poverty and human rights abuses.

Because the government controls the legislative process, there is a risk that it could provide excessive social and welfare services with excessive taxation of the private sector [independent]. These taxes, together with increased public sector enterprises, may reduce the private sector contribution and lead to decreased economic growth and job creation. (Book A, 58-59)

In South Africa discrimination [independent] played a great part in creating poverty [dependent] among certain groups. During apartheid [independent] the government discriminated [dependent] on the basis of race, ethnic group and gender. Few opportunities were given to some groups to obtain well-paid jobs, adequate housing, a good education or health care [independent]. (Book B, 189)

The free market [independent] is possibly the best way of solving the problem of unequal distribution [dependent] whereby new businesses create new jobs for previously disadvantaged people. However, markets take time to equalize wealth and income even after democracy has had a chance to improve matters by reducing discrimination [independent]. In such instances, the government [independent] is often called upon to the tackle the problem [dependent] head on. In South Africa economic redress is applied to improve the standard of living of all people. This is done by improving everyone's access to economic resources through equal opportunity [independent]. (Book C, 164)

To address the issue of unequal distribution of wealth and income, and poor productivity rates [dependent], we need more [independent] than just anti-discriminatory regulations. Participation and access by marginalized groups need to be increased at all levels of the economy in South Africa [independent] to redress the imbalances in the ownership and control of South Africa's resources [dependent]. (Book D, 24)

Disadvantages of a market economy.

The distribution of income is unfair, the rich become richer and the poor may be poorer. (Book E, 48)

The economic practice of discrimination is an apparent rational explanation for poverty. The theme is prevalent in the texts and can be seen through the use of words in independent and dependent clauses such as "discrimination" (Book B, 188; Book C, 164; Book D, 24; Book E, 48) and "not equitable" (Book A, 58-59). Discrimination is present in the disparity in income in the mixed economic system. The disparity is presented through the clauses, the context, and the justification for poverty. The following phrases taken from independent and dependent clauses show disparity in the distribution of income and make explicit references to poverty in South Africa: "disadvantages of mixed economies" (Book A, 58-59), "In South Africa discrimination" (Book B, 188), "The free market is possibly the best way of solving" (Book C, 164), "more than just anti-discriminatory regulations" (Book D, 24) and "distribution of income is unfair" (Book E, 48). The importance of privatisation is affirmed through the insinuation that the free market surpasses the current mixed economies of private and public (Books A, B, D and E) and all other economic systems as well.

The dependent clauses in Book A (58-59) above state the following: "Despite all efforts, income distribution is still not equitable", "still faces problems of unemployment, inflation and business cycles", and "excessive social and welfare services". The independent clauses assert the authority of the system and the regulations of the system. These assertions are linguistic illustrations of legitimate reasons for the existence of increased poverty.

The argument presented is that the mixed economy apparently encourages disparity in the distribution of income, which should be accepted as normal. What is noteworthy is the contradiction introduced with the use of the word "despite". The word "despite" (Book A, 58-59) apparently shifts attention away from the "efforts" that have been made to distribute income equitably, but it is not clear from the text what efforts have been made and which group is served by these efforts. In contrast, the word "still" (Book A, 58-59) emphasises the persistence of the problems of gaining employment in the market under a mixed system. The repetition of the word "still" (Book A, 58-59) appears to reinforce the system that legitimates private business mistreatment of the workers, and explains the increase in poverty. Book A (58-59) seems to validate this rationale by explaining that the mixed economic system contributes to poor "efficiency" and does not "reduce poverty speedily". Invariably, this subscribes to the thinking that there is unfairness and discrimination inherent in the mixed economic system.

Poverty is rationalised by presenting the disadvantages of a mixed economic system and it is apparent that a free market is favoured in Book C (164). This text states that the situation of poor people is possibly due to discrimination arising from not having access to "equal opportunities" to wealth and income. The words "the free market is possibly the best way" (Book C, 164) influence the reader's acceptance of the discrimination inherent in the choice of an economic system. Book D (24) is in agreement with this way of explaining the lack of "access by marginalized groups" due to inequity in the "distribution of wealth and income" arising from a lack of "participation" in the economy.

Poverty is explained using the rationalisation of prejudice, as indicated by the word "discrimination" in Book B (189). The findings demonstrate that prejudice was practised using racial, cultural and gender categorisations. The implication is that the marginalised groups did not get access to jobs that paid well, decent homes and respectable education and health care. In Book B (188), with respect to the distribution of "opportunities" in terms of access to "well-paid jobs, adequate housing, a good education or health care", discrimination and unfairness seem to be the basis of the explanation. The phrases "distribution of income is unfair" (Book E, 48) and "the poor may be poorer" (Book E, 48) appear to support the theme of discrimination being used to explain and rationalise the existence of situations of unequal access, and hence the prevalence of poverty in South Africa.

In Book E (48), the discussion is about the "disadvantages of a market economy", but the use of the word "may" in this discussion creates uncertainty for the reader. This apparent uncertainty is evident in the boldness of the title, which can be seen as a strategy of "topicalisation" (McGregor 2003, 5). Topicalisation places a particular sentence or words in a topic spot, and thus influences the reader to think in a particular way. In this instance, the reader is being manipulated to think of the free market as the market of choice. However, ambiguity is introduced with the use of the word "may", which creates uncertainty that discrimination in the free market is responsible for the fact that "the rich become richer and the poor may be poorer" (Book E, 48). The ambiguity creates uncertainty about whether the free market situation could worsen poverty. There is an implicit favouring of the free market as the system of choice. The implication is that in Books A, B, C, D and E, the economic practice of discrimination is used to explain poverty in the texts. Discrimination against the poor within the free market system (capitalism) is promoted through unethical behaviour.

The recurring theme of the segregation of marginalised people is observed in clauses in Book A (58-59), B (188), C (164), D (24) and E (48). The solution to inequality is the free market system, according to the texts. This proposition may influence the reader's acceptance of the discrimination in the choice of an economic system.

Structural Limitations Used to Rationalise the Legitimation of Poverty

Structural factors limit the opportunities for employment and provide a reasonable explanation for the poverty that exists in South Africa. These structural factors were listed with groups of words in the independent clauses in Books A, B, C, D and E. A list of potential structural explanations was identified in the texts. These were used to explain the economic structures that are given prominence and placed in independent clauses, such as "income inequality" (Book A, 158), "economic growth" (Book B, 190), "[c]ertain structures which exist in the economy such as access to markets" (Book C, 26), "economically marginalized" and "excluded from the decision-making processes in the economy" (Book D, 24), and "production in Africa" (Book E, 240).

While both Book A (158) and Book B (190) cite the issue of "unemployment" as a dependent clause, Book A offers the explanation that this results from the widening of the "rich-poor gap", whereas Book B (190) explains that "reducing unemployment can alleviate poverty". The explanation in Book B goes further by naming the policies of the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) and the Growth, Employment and Redistribution Act (GEAR) used by the government to reduce unemployment. Book A (158) and Book C (26) both list the subject of unequal access to the market through resources. Book A (158) and Book D (24) list the matter of probable gender discrimination against women as another explanation. Book A, while it has structural factors in common with Books B, C and D as discussed in the previous sentence, also deviates from them by including "education", "family size", "cultural and personal preference", "inheritance" and "globalization" (158) with the structural factors. Book E (48), while displaying an understanding of probable structural factors and providing a very brief explanation for poverty, cites the matter of "production in Africa is so low" as a reason for the persistence of poverty.

The structural limitations present in the texts are as follows: Book A (158) cites the issues of a shortage of skills and education and gender discrimination with regard to access to the labour market. These are the underlying reasons for income disparity between the affluent and the poor. Book D is similar to Book A in naming discrimination against women. Book D posits the exclusion of women's voices from the "decision-making processes in the economy" (Book D, 24) as an explanation for their non-participation in the economy. Book B (190) uses policies such as the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) and the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) to justify the current situation regarding the position of the poor. In other words, the explanation provided is that although these policies have been implemented, a disparity in income still exists. Book C (26) gives details relating to "access to the markets" and the existence of "monopolies" as structural factors that explain the marginalisation of the poor. Book E (240) puts forth the slump in "production in Africa" as a structural factor that can be used to explain the difficulty in "finding solutions to high levels of poverty". The context of feasible structural limitations contained in the discourse of Books A to E is given as the reason for poverty.

Individual Deficits Used to Rationalise and Legitimate Poverty

The findings from Book A, B, C, D and E reveal that the strategy of legitimation is based on individual problems. Each of these books use individual factors as independent clauses to emphasise this, thereby justifying the existence of poverty.

In this paragraph, we look at the words and groups of words from independent clauses in each of the texts. Book A includes a discourse relating to "diseases" (206), indicating that the condition of poverty may be attributed to the ill health of individuals, which "decrease[s] the amount of work" (206) a person is able to perform. The text rationalises poor health, and specifically HIV and AIDs, as the likely cause of "reducing their income and driving them deeper into poverty" (206). It is also seen as a factor "which can cut off a main source of income for the family" (206). Book B's rationalisation for poverty is that "individuals may become discouraged by poverty, and they lose their self-esteem and confidence, because they cannot provide for themselves and their families" (188). This discourse may well be ambiguous. On the one hand, the implication is individuals are not encouraged to find ways to elevate their status in life. On the other hand, the discourse begins by contending that "the main impact of poverty is personal, because the most affected is the one who is poor" (188). Such ambiguity may confuse the reader insofar as it attributes poverty to individual apathy. Book B goes on to explain that this apathy could continue if the social grant is "too high" (188).

Book C, like Books A and B, looks to the individual to explain poverty. The findings in Book C claim that "endless opportunities exist for anyone to become rich, yet so few people seem able to do so-while the rich get richer, the poor get poorer" (Book C, 157). The use of the word "yet" (157) implies that even though economic opportunities exist, the poor have low achievement levels and this is the reason for their poverty. The reader is being channelled to think in this way and this is clear from the instruction that follows: "[w]ith this in mind, attempt to answer the following questions" (157). This logic is reinforced by the further reasoning that if "three million black middle class adults" (157) could take advantage of the economic opportunities, why is it the poor are not able to do this? This is clear from question two of the activities, which requires answers to the following question: "What factors are hampering poor people from obtaining their share of South Africa's wealth?" (157).

Similar attitudes are evident in Book D (121) where it is argued that the "government spends about 6% of GDP on education and South Africa's teachers are among the highest paid in the world (in purchasing power parity terms) but, despite this, quality of education remains a problem. Literacy and numeracy tests scores are low by African and global standards." The use of the words "despite this" may influence the reader into thinking that the problem of poverty should not be blamed on the government but rather on the individuals' lack of initiative to increase their proficiency in language and mathematics. This rationale is carried forward in Book E, where individuals are held responsible for their poor economic position "because they do not have the appropriate skills" (37-38), and further that "even if you do give them the skills, it will take ten to twenty years for them to find jobs" (37-38). The words "yet" (Book C, 157), "but" (Book D, 121), "they" and "even if" (Book E, 37-38) insinuate that poverty is due to individuals not taking advantage of opportunities, and suggest an unwillingness on the part of the poor to relinquish their status. The discourse in Books A, B, C, D and E relies on the agency of the individual, and not the socio-economic context, to explain poverty.

The Effects of Globalisation Used to Rationalise the Legitimacy of Poverty

The strategy of using controversies surrounding globalisation as independent clauses and as institutional factors that explain poverty is prevalent in Books A, B, C, D and E. The justification is explicit in some cases and indirect in others. The negative effects of globalisation as a probable cause of poverty is advocated very strongly in Book A. On page 208, the discourse manipulates the reader to accept that poverty exists because of "lack of education, malnutrition, violence inside and outside their homes, child labour and diseases". This situation is apparently due to "the global financial crisis ... a global problem from which we in South Africa cannot escape" and which "has a huge effect on child poverty". The reasoning is that poverty is a result of global challenges that exist throughout the world, and not only in South Africa. This manipulation in Book A is also evident in Book B. Book B's (222) position is that through the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD), Africa is being marginalised in the globalisation process. The apparent argument is that Africa should pursue "its full and beneficial integration into the global economy". The text bullets one of the chief objects of NEPAD as eliminating poverty (222), but offers no explanations or details, which may suggest that NEPAD will not be able to eradicate poverty. However, the linking of the three objectives of NEPAD may imply that through growth and development, as well as increased participation in the global arena, NEPAD may eradicate poverty in Africa.

We also uncovered an incidental reference to globalisation in Book C (26), which occurs in a discussion that compares the "development and standard of living" of countries within Africa. This text does not use the words global or globalisation but the use of the words "African countries" suggests a comparative African approach. It also suggests that a low economic growth rate and increased populations appear to be the reason for the poverty crisis in African countries.

Book D uses an ambiguous discussion of globalisation to validate potentially the existence of poverty. On the one hand, the position is that "the natural resources of poor countries are often exploited by richer countries" (225). On the other hand, Book D asserts that the "fight against poverty can only be won if it is a global effort, with the richer countries supporting the poor countries in their fight against poverty" (225). The implication is that poor countries are dependent on affluent nations to solve their poverty predicament. Book E (251) uses a straightforward approach to vindicate and support globalisation as being "able to reduce the poverty level by a large margin".

Access and Proximity to Resources Used to Rationalise Poverty

A strategy of legitimation used to rationalise poverty, which Books A, B, C, D and E share to a greater or lesser extent, relates to access to, and the proximity of, resources. Book A emphasises the "lack of productive resources" (206) by placing the writing in bold and also by crafting the words "in poor countries, there are not enough productive resources" (206) as an independent clause. This topicalising and inclusion as an independent clause are intended to rationalise the reality of poverty. The text positions poor countries' lack of access to resources that can increase production as a possible reason for poverty. These resources include the following: first, human resources are insufficient due to impoverishment, health issues and low education levels; second, poor maintenance of natural resources; third, a lack of infrastructure in "poor rural villages" as a result of short-term economic decisions that do not favour saving; and finally, "[e]ntrepreneurship is non-existent, because of a lack of education and skills development" (206).

The positioning of access to resources to rationalise poverty also materialises in Book C and Book E. On page seven, Book C uses the following words as a heading: "Accessibility of the Economically Marginalised Groups". Book E includes the issue of access to resources by subscribing to the following definition of poverty: "Poverty can be defined as a condition in which a person or a family does not have the resources to satisfy basic needs such as food, shelter, transport and clothing" (175). Book B asserts that the government may be able to provide better access to resources and, therefore, reduce poverty by giving consent for "projects to be started and that as soon as these projects become economically viable, they can be privatized" (56-57). Book D relies on the issue of development to explain the "access to basic needs" (175) by the poor. The implication is that not having access to and not being within the vicinity of resources is a justification for poverty.

Using Capitalism to Rationalise Poverty

Capitalism is also used as a strategy to legitimate poverty. Book A (52) states that one of the disadvantages of a free market system is that "the distribution of income is not equitable". Wealth that is created apparently goes to those with capital. Hence, the rich become richer and the poor become poorer. The unemployed, sick, and homeless suffer. To convince the reader, a detailed explanation is provided to illustrate the disadvantages of capitalism, and this is presented using bullets. These include the following: first, "[r]esources are often under-utilised or not efficiently utilised". Second, "the distribution of income is not equitable". Third, "the freedom of choice does not apply to the poor". Fourth, "the profit motive can lead to the exploitation of workers". Fifth, "the use of technology and capital leads to increased unemployment levels and poverty". Sixth, "freedom of enterprise can lead to under-provision of merit goods" and "the market economy has no mechanism for reducing the equalities between the rich and the poor" (Book A, 52). These independent clauses emphasise the reasons for poverty under capitalism.

Book B discusses the problems of capitalism and the need for the involvement of the government. The discussion ends with the following quiet insertion: "As soon as these projects become economically viable, they can be privatized" (Book B, 56-57). This style of writing paradoxically both blames capitalism for poverty and vindicates it as a means of ending poverty. Books B, C, D and E all argue in this paradoxical manner, with the likely intention to confuse the reader into believing that poverty exists because of capitalism, but capitalism is required to end it. This is evident in the activity given in Book D, with two questions on capitalism and one question concerning the command system and the poor. The context of capitalism as a discourse is applied as a potential explanation for the situation of the poor. The apparent presentation of the definition of capital as neutral may be misleading. The reader may be led to a false understanding that capitalism's only role is to obtain and utilise capital to enable financial and economic operations. However, the apparent social power of wealth distribution and its accompanying effects that exploit the poor are masked.

Low Wages, Prices of Goods and Poor Infrastructure to Rationalise the Legitimacy of Poverty

The findings show Books A, B, C, D and E use low wages, the prices of goods, and poor infrastructure as a strategy to rationalise poverty. These texts prioritise certain economic instruments to explain the possible poverty of people relative to low wages and consumption. The following quotations from independent clauses are used in the texts: "A country's income distribution" (Book A, 157) and "the standard of living in developing countries is generally low-mostly due to low income" (Book E, 159). These clauses explain the disparity in spending between the rich and the poor. The discourse in both texts (A and E) comments on the disparity in spending between the rich and the poor, with the poor having difficulty in purchasing basic or essential items of food. We believe it is reasonable to assume that this disparity in spending is attributed to the differences in income between the rich and the poor, with the poor having a very low income. The rich have access to a variety of products and choices. The poor are denied access to goods and services as well as infrastructure. These patterns of denial are carried through in the following discourse contained in Books B, C, and D. Book B (11) contains the following quotations from independent clauses: "[g]ood jobs, earnings, and allowances", "[r]ecent economic growth", "[a] lack of economic opportunity", and "[t]he informal sector". These clauses are used to explain the inability of the poor to take advantage of the products and services in the manufacturing sector. These independent clauses reveal the following:

• First, an apparent acknowledgement of the importance of having a decent income for the poor;

• Second, that this denial of access to a decent income probably fuels labour unrest;

• Third, that the challenges in the labour market are recognised as a "development issue" (11) for South Africa that has been topical for the past 20 years;

• Fourth, that the informal and formal sector roles may have an impact, with the informal sector playing a significant role in creating income for "70-90%" (11) of the people.

"Marginalized groups" (Book C, 26), "example" and "income elasticity" (Book D, 109) are used to explain the expenditure of the poor on essential goods. The implication is that this is due to low wages or a lack of wages. Book D speaks of "economically marginalized" (Book D, 109) people. Here, the example of a candle is used, an essential item that is required by marginalised people who do not have access to electricity. The change in demand for such an essential item is affected by changes in the income of the poor. In Book E (159), the standard of living of marginalised people is captured as "low income that results in poverty" and "people who struggle to meet their basic needs". The implication of the discourse on low wages, the price of goods, and the lack of infrastructure is that these present presumed reasons for poverty.

Discussion

Although Brady categorises poverty theories into three distinct groupings (behavioural, structural and political), he laments the somewhat insular manner in which researchers in these sub-fields work to negate or nullify one another's hypotheses (Brady 2019). He argues instead for integration and greater interdisciplinarity as scholars of poverty. It must be noted that writers of school economics textbooks (usually experienced school teachers and economics curriculum specialists/advisors in South Africa) may not be poverty specialists. As such, the causes of poverty and the theoretical bases for such causes are not comprehensively articulated nor effectively categorised. It is also important to recognise that poverty is only one of an array of topics that feature in the school curriculum. It might thus be unfair to expect nuanced/sophisticated explanations of poverty that might be found in a textbook exclusively on poverty. Textbook authors appropriate existing theories of poverty deemed to be constructively aligned to the content specifications of the CAPS, the national policy statement that spells out the state's ideological orientation. This "worthy" and "valued" knowledge is selected and programmed for study by school learners. The Department of Basic Education sets up content vetting committees to assess the validity and relevance of textbook content, a screening process that attends to issues of content accuracy and unwarranted bias and prejudice as it relates to race and gender in particular. This latter emphasis is particularly salient in the South African context given the country's history of racial prejudice and contemporary gender discrimination. While these appear as commendable objectives of such screening committees, the data and the analysis presented above suggest that less overt bias as it relates to the subliminal messages embedded in state-sanctioned content goes completely undetected. Textbook publishers, in their quest to remain on preferred, officially sanctioned and recommended catalogues, adhere tightly to CAPS prescriptions and proceed to compile their texts accordingly. It is in essence a strategic compliance so as to be favourably positioned in the lucrative school textbook market.

So, while textbook content selection is presented as transparent and state-approved, there is much to be concerned about in terms of what is projected as truths in disciplinary subject fields where there are stark theoretical contestations. It may be reasonable to argue that school textbook publishers (and their commissioned writers) may not be consciously culpable and that there may have been no malicious intent at the time of writing. It does, however, raise concern, given that particular distortions (of truths) are in fact prevalent in the selection of school textbooks under study, that similar patterns might be at work in other school subjects. Of importance are the implications that these findings have for the various stakeholders in the textbook production and consumption enterprise.

Through an intense and rigorous CDA protocol, this study was able to discern that poverty is legitimated using the legitimating strategies described above and that the causes of poverty are presented to the potential reader in a somewhat random fashion. In essence then, while the various articulations of the causes of poverty might well fall into any of Brady's three sub-categories (behavioural, structural or political), these explanations live at a somewhat superficial level. This study revealed how particular legitimating strategies work as convincing mechanisms or techniques to position particular truths. In this instance, it becomes clear that through distinctive linguistic sequencing and discourse appropriations, the concept of poverty is packaged and dispensed for consumption by the users of such textbooks. The purpose of the study was to expose what explanations of poverty prevail and what biases may be prevalent. The notion of a truthful representation is relative and possibly even elusive. What the article argues for is that textbooks should attempt to provide a balanced perspective on why poverty exists in society. This raises the issue of what this might imply for curriculum and pedagogy.

How might schoolteachers, subject advisors, examiners, or teacher educators, for example, detect and respond to ideological biases and distorted worldviews that may be evident in South African school textbooks? A somewhat "sinister" sub-plot as revealed by the focus of this study is that the poor (learners) are taught particular accounts of why poverty exists, some of which indict them for their current condition. Given that almost 65% of South Africans live below the poverty line (Lehohla 2017), classrooms are inhabited by children from varying socio-economic backgrounds, including children who hail from indigent families. It thus becomes necessary for teachers to develop high levels of sensitivity about whom their learners are. Importantly, it might well mean that teachers have to develop particular pedagogic practices that respond to their learners in a manner that is inclusive and ensures that the dignity of all children is preserved as economics is taught as a school subject. A humanising pedagogy, one that recognises and values learners as human beings and is critical of the subtext of content being dispensed, is vital (Khene 2014).

The findings of this study also have implications for teacher education. While the focus was exclusively on economics textbooks, it is reasonable to expect that the content of other school subjects (History, Geography, Business Studies) might also present controversial subtext. Teacher education needs to take cognisance of critical textbook usage as teacher preparation programmes are designed for and taught to preservice teachers. It becomes clear that teacher education must move beyond developing technical competences of teacher trainees. The issue of what to teach and how to teach (especially contentious subject material) must also receive due attention. These insights are also applicable to in-service teacher education programmes (continuing professional development) that are offered by subject advisors. Similarly, the school textbook publishing industry whose content selections determine the type of knowledge to be studied by school learners needs to be sensitive to the socio-economic contexts in which their products are used.

Conclusion

In this article we reported on a study that examined the legitimisations of poverty in school economics textbooks. We revealed how linguistic techniques and discourses work to legitimise particular worldviews. We exposed how ideological content might be presented as neutral and drew attention to the need for the various users of school textbooks to be vigilant of the subtext of what is presented as harmless knowledge. This study has implications for future research into, for example, how competencies to discern ideological bias might be inculcated in the South African schooling sector, which is hugely dependent on textbooks. A particularly disturbing revelation in this study was the subliminal messages about poverty that might be projected to the marginalised poor.

References

Albrecht, D. E., and S. L. Albrecht. 2000. "Poverty in Nonmetropolitan America: Impacts of Industrial, Employment, and Family Structure Variables". Rural Sociology 65 (1): 87-103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2000.tb00344.x. [ Links ]

Andreoni, J. 2006. "Philanthropy". In Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity, edited by S.-C. Kolm and J. M. Ythier, 1201-269. Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0714(06)02018-5. [ Links ]

Apple, M., and L. Christian-Smith. 1991. "The Politics of the Textbook". In The Politics of the Textbook, edited by M. Apple and L. Christian-Smith, 1-22. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Avalos, B. 1992. "Education for the Poor: Quality or Relevance?" British Journal of Sociology of Education 13 (4): 419-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569920130402. [ Links ]

Bradshaw, T. K. 2007. "Theories of Poverty and Anti-Poverty Programs in Community Development". Community Development 38 (1): 7-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330709490182. [ Links ]

Brady, D. 2019. "Theories of the Causes of Poverty". Annual Review of Sociology 45 (1): 15575. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022550. [ Links ]

Clawson, R. A. 2002. "Poor People, Black Faces: The Portrayal of Poverty in Economics Textbooks". Journal of Black Studies 32 (3): 352-61. https://doi.org/10.1177/002193470203200305. [ Links ]

DBE (Department of Basic Education). 2011. Action Plan to 2014: Towards the Realisation of Schooling 2025. Pretoria: DBE. Accessed September 8, 2020. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/Action%20Plan%20to%202014%20(Full).pdf?ver=2012-10-12-141840-000. [ Links ]

DBE (Department of Basic Education). 2016. Annual Performance Plan 2016/17. Pretoria: DBE. Accessed September 8, 2020. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/Annual%20Performance%20Plan%202016_17.pdf?ver=2016-03-31-122302-020. [ Links ]

Easton, D. 1965. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Erler, H. A. 2012. "A New Face of Poverty? Economic Crises and Poverty Discourses". Poverty and Public Policy: A Global Journal of Social Security, Income, Aid, and Welfare 4 (4): 183-204. https://doi.org/10.1002/pop4.13. [ Links ]

Feiner, S. F., and B. A. Morgan. 1987. "Women and Minorities in Introductory Economics Textbooks: 1974 to 1984". The Journal of Economic Education 18 (4): 376-92. https://doi:10.2307/1182119. [ Links ]

Ferguson, J., D. Collison, D. Power, and L. Stevenson. 2009. "Constructing Meaning in the Service of Power: An Analysis of the Typical Modes of Ideology in Accounting Textbooks". Critical Perspectives on Accounting 20 (8): 896-909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2009.02.002. [ Links ]

Flick, U. 2009. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Gallagher, D. J., and R. Thompson. 1981. "A Readability Analysis of Selected Introductory Economics Textbooks". The Journal of Economic Education 12 (2): 60-63. https://doi:10.2307/1182235. [ Links ]

Gee, J. P. 2005. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gee, J. P. 2011. How To Do Discourse Analysis: A Toolkit. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203850992. [ Links ]

Gilley, B. 2006. "The Meaning and Measure of State Legitimacy: Results for 72 Countries". European Journal of Political Research 45 (3): 499-525. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00307.x. [ Links ]

Habermas, J. 1973. Theory and Practice. Translated by J. Viertel. Boston, MA: Beacon. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Khene, C. 2014. "Supporting a Humanizing Pedagogy in the Supervision Relationship and Process: A Reflection in a Developing Country". International Journal of Doctoral Studies 9: 73-83. https://doi.org/10.28945/2027. [ Links ]

Lucio, J., A. Jefferson, and L. Peck. 2016. "Dreaming the Impossible Dream: Low-Income Families and Their Hopes for the Future". Journal of Poverty 20 (4): 359-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2015.1094772. [ Links ]

McConnell, R. C. 1982. "Readability Formulas as Applied to College Economics Textbooks". Journal of Reading 26 (1): 14-17. [ Links ]

McGregor, S. L. T. 2003. "Critical Discourse Analysis-A Primer". Kappa Omicron Nu 15 (1). Accessed September 8, 2020. http://www.kon.org/archives/forum/15-1/mcgregor_print. [ Links ]

Minujin, A., and S. Nandy, eds. 2012. Global Child Poverty and Well-Being: Measurement, Concepts, Policy and Action. Bristol: The Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781847424822.001.0001. [ Links ]

Pacheco, J. S., and E. Plutzer. 2008. "Political Participation and Cumulative Disadvantage: The Impact of Economic and Social Hardship on Young Citizens". Journal of Social Issues 64 (3): 571-93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00578.x. [ Links ]

Phipps, B. J., R. J. Strom, and W. J. Baumol. 2012. "Principles of Economics without the Prince of Denmark". The Journal of Economic Education 43 (1): 58-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2012.636711. [ Links ]

Pogge, T. W. 2010. Politics as Usual: What Lies Behind the Pro-Poor Rhetoric. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Pogge, T. W., and M. Sengupta. 2014. "Rethinking the Post-2015 Development Agenda: Eight Ways to End Poverty Now". Global Justice: Theory Practice Rhetoric 7: 4-9. https://www.theglobaljusticenetwork.org/index.php/gjn/article/view/43. [ Links ]

Rieber, W. J. 2010. "A Note on the Teaching of Dumping in International Economics Textbooks". The American Economist 55 (2): 170-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/056943451005500218. [ Links ]

Robson, D. 2001. "Women and Minorites in Economics Textbooks: Are They Being Adequately Represented?" The Journal of Economic Education 32 (2): 186-91. https://doi.org/10.2307/1183494. [ Links ]

Ramdhani, J. 2018. "A Critical Analysis of Representations of Poverty in School Economics Textbooks". PhD diss., University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Rogers, R., E. Malancharuvil-Berkes, M. Mosley, D. Hui, and G. O'Garro Joseph. 2005. "Critical Discourse Analysis in Education: A Review of the Literature". Review of Educational Research 75 (3): 365-416. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003365. [ Links ]

Seekings, J., and N. Nattrass. 2016. Poverty, Politics and Policy in South Africa: Why Has Poverty Persisted After Apartheid? Johannesburg: Jacana Media. [ Links ]

Smith, M. N. 2017. Review of Poverty, Politics and Policy in South Africa: Why Has Poverty Persisted After Apartheid? by Jeremy Seekings and Nicoli Nattrass. New Agenda: South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy 66: 47-48. [ Links ]

Spaull, N. 2013. "Poverty and Privilege: Primary School Inequality in South Africa". International Journal of Educational Development 33 (5): 436-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijedudev.2012.09.009. [ Links ]

Lehohla, P. 2017. Poverty Trends in South Africa: An Examination of Absolute Poverty Between 2006 and 2015. Report No. 03-10-06 Pretoria: Stats SA. Accessed September 10, 2020. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-06/Report-03-10-062015.pdf. [ Links ]

Streib, J., M. Ayala, and C. Wixted. 2017. "Benign Inequality: Frames of Poverty and Social Class Inequality in Children's Movies". Journal of Poverty 21 (1): 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2015.1112870. [ Links ]

Thompson, J. B. 1990. Ideology and Modern Culture: Critical Social Theory in the Era of Mass Communication. Oxford: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Tyler, T. R. 2006. "Psychological Perspectives on Legitimacy and Legitimation". Annual Review of Psychology 57: 375-400. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.PSYCH.57.102904.190038. [ Links ]

Williams, R. 1989. "Hegemony and the Selective Tradition". In Language, Authority and Criticism: Readings on the School Textbook, edited by S. De Castell, A. Luke and C. Luke, 56-59. London: The Falmer Press. [ Links ]