Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.23 n.1 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/5037

ARTICLE

Reflexive Encountering and Postgraduate Research Training in South Africa

Gretchen Erika du Plessis

University of South Africa gretmar@mweb.co.za. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8213-8614

ABSTRACT

This article, based on theoretical reflections and empirical examples, outlines dilemmas in the social positioning of postgraduate research when students are challenged with their locations as insiders and outsiders in terms of the issues they investigate in Development Studies. Encountering the "other" and oneself in, against and beyond the scholarship-activism binary offers fertile ground for engaged research yet is entangled with configurations of power and regulation in academia. This argument is developed by drawing on three recent examples of postgraduate research production and a quantitative rapid appraisal of postgraduate production at a tertiary institution. The analysis of quantitative data and case studies evinces particular issues in outsourcing of knowledge production, researcher reflexivity, possibilities for co-production and tenacious anticipatory-procedural ethics as embedded in institutional practices and orthodoxies that direct, enable and constrain such matters. The author questions the normalisation of knowledge-production power when the imperative to mutual, inclusive learning, coupled with critical self-reflection by researchers in Development Studies is thwarted. Possibilities to overcome these dilemmas in Mode three institutions are suggested.

Keywords: insider-outsider binary; anticipatory ethics; relational ethics; reflexivity in postgraduate research; participatory research

Introduction

In the current intellectual climate, social researchers are required to be more reflective of their positionalities as insiders and outsiders in research (Dawson and Sinwell 2012; Dean 2017; Geleta 2014; González-López 2011; Keane, Khupe, and Muza 2016; Pearson and Paige 2012; Thompson 2018). Beyond the dilemmas of truly participatory research and dialogic co-inquiry, this obvious problem can be difficult to overcome in the contexts of colonial histories and politics (Bell and Pahl 2018; Faria and Mollett 2016; Giwa 2015). For example, researchers might find that their attempts at resisting an ascribed positionality can reinforce the very colonial identities of power they want to problematise in their research.

This article, firmly embedded in an empirical analysis of lived teaching practice, stems from the researcher's1 own concerns about her reflective positionality as it regulates her guidance for postgraduate research, especially in instances where the outsourcing of an integral part of knowledge production or collaboration with vulnerable groups is indicated. Reflective positionality is required in research in Development Studies as suggested by Scheyvens (2014, 4): "There is considerable merit in research which crosses the bounds of one's own culture, sex, class, age and other categories of social positioning, and due to the need to work across the North, South, East and West to find solutions to pervasive issues of poverty and inequality." Assuming the historical presence of slow violence in this stance, a question arises over the role played by the outsourcing of data-gathering and the avoidance of assumed harm to the vulnerable in academic practice. What kind of knowledge is produced remotely, away from the unpredictable, complex and changing context in which research collaborators and participants live, act and interact? How is this problem best addressed and afforded the ethical imperative it deserves without adding to an already over-regulated system of compliance and endless paperwork?

Binary insider-outsider roles prohibit an espousal of the complex fluidity in researcher identities labelled as native, foreign, embedded, public, and activist-researcher. In addition, internalisation of knowledge-production hierarchies occurs when outsourcing parts of research becomes simplified, pragmatic functionality without an imperative to mutual, inclusive learning (Cornwall 2003).

Objectives of the Study

The primary research objective is to reveal the dilemma of fostering research in Development Studies that aspires to qualitative, rich description and understanding unfettered by pre-emptive ethical reviews and "objective" approaches. To this end, the researcher undertook the analysis of three case studies supplemented by a rapid assessment of quantitative data obtained from a repository on postgraduate research production. The secondary objectives were to:

• provide a theoretical background to encountering the other in research

• demonstrate the practices of power dynamics in knowledge creation using three case studies and a quantitative rapid assessment of postgraduate research production in Development Studies

• offer guidelines to overcome these issues that may inform ethics policies, training and collaborations.

Theoretical Point of Departure: Encountering the "Other" in Research

Theoretically, the article draws on Foucault's understanding that an instrumentalised, value-free notion of research reifies problematic power relationships because "disciplines constitute a system of control in the production of discourse" (Foucault 1972, 224). From this, it can be argued that research traditions followed in higher education institutions become entrenched in safe zones of accreditation and incentivisation, where outputs are published, passed in performance audits for promotions, judged as befitting a highly abstracted model of scientific research and passed by ethical review committees (ERCs). Dawson and Sinwell (2012, 178) refer to this as ensconcing "slothful, meretricious, even cynical intellectual habits." Babb, Birk, and Carfagna (2017), Baloy, Sabari, and Glass (2016), and Schneider (2015) conclude that research endeavours that create anxieties about legal risks to the institution are blocked by institutional ERCs. In addition, ERCs are often made up of volunteers posing as bureaucrats applying erratic, excessive, and paternalistic rules to standardise and regulate the research process. Nevertheless, the same molar2 regulatory, indemnifying process remains silent on the questionable ethics of claiming authority as experts in research based on the knowledge labour of those who remain marginal.

Most research methodology training programmes present these dilemmas to students under the rubric of the politics of research. From this, students cognitively encounter the notion that their self-identification would shape the rationale, process, and outcomes of their methodological choices. Students are taught the mechanics of reflexivity and research ethics, yet fostering their critical attitudes about what the research is used for is not met with the same enthusiasm. This could-in part-be explained by the regulatory frameworks that would anathematise researchers wishing to embrace participatory, ethnographic or emancipatory frames as posing risks to themselves, their research participants and their institutions. The research gaze is narrowed due to fears inherent to a risk society and an institutional context of heightened individual accountability, external scrutiny, audit-obsession, risk aversion, and internal control amidst financial austerity and institutional collapse. The resultant "ethical imperialism" (Van den Hoonaard 2011) or even "epistemological nihilation" (Baloy, Sabati, and Glass 2016) undermines, excludes, and delegitimises certain methodologies and dehumanises particular minoritised groups as far too vulnerable to be exposed to the assumed research predations of the powerful.

Whereas the author concurs with Baloy, Sabati, and Glass (2016, 13) that "to enter into research is to enter sites of trauma" and that this potentially makes research an "ongoing form of coloniality" the kind of reflexivity advocated here demands responsibility in the discipline to disrupt and break with self-imposed constraints. Institutionally imposed categories of assumed vulnerabilities of risk groups are akin to Spivak's (1988) ventriloquism, because they have paternalistic social eviction possibilities for the choices of research problems, sites, methodologies, and co-researchers. This may well lead to an erroneous and harmful assumption that researchers who avoid direct human research or participatory work are more "ethical" than others. Instead, this article advocates in favour of a relational ethics as articulated in the deliberative stance of Tavernaro-Haidarian (2018a; 2018b).

The Relevance of Relational Ethics for Research Practice

Relational ethics in research training is particularly relevant in the era of so-called Mode 3 tertiary institutions. Mode 33 universities attempt to transcend the traditional, linear knowledge-production emphasis of Mode 1, and the purely socially driven scholarly agenda of Mode 2. Mode 3 strives to combine the two preceding modes through collaboration, partnerships, and engaged, impactful, innovative research (Campbell and Carayannis 2016). Moreover, Mode 3 research training is directed at building leadership capacity to deal with complex or wicked problems (Ramaley 2016, 12). In addition, collaborative partnering in research that focuses on transformation, impact, and implementation, calls for ethics of and in practice. Deliberative ethics in practice denotes an adaptive orientation to mutual learning and respectful negotiations with a range of stakeholders in fluid, evolving engagements prior, during, and after data generation (Carter and Williams 2019; Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018a).

Researching complex problems implies the involvement of different stakeholders with their own agendas and claims to power and knowledge (Carter and Williams 2019). Complex problems have interacting networks of factors that change even amidst the implementation of possible solutions (Ramaley 2016). Research on complex problems, and importantly, postgraduate research training for such work, invite openness to multiple views on wicked problems and their possible solutions (Lample 2015, 157).

May and Perry (2011, 125) refer to such openness as "epistemic permeability," which should occupy a central place in reflexive, engaged research.

Two interrelated issues mitigate against reflexive encountering. Firstly, rigid institutional ethical clearance practices instil mechanical, ritualistic box-ticking according to set templates. Secondly, separating the role of researcher and that of activist-practitioner normalises closed learning systems unable to respond to the need for an ethics in practice.

When researchers fail to be adequately reflexive, they become complicit in marginalisation (Marshall and Rossman 2006). Researchers working in participatory, emancipatory, and transformative paradigms deliberately push against marginalisation. Notwithstanding, many of these researchers find that resisting an ascribed positionality, in other words, becoming an insider in respect of their study site and participants, is exceptionally difficult. In reaction, they might outsource some parts of the research encounter to intermediaries.

Relying on locally recruited, researcher-trained, itinerant interlocutors to undertake data extraction seems antithetical to engaged, reflexive research. In many cases, the interlocutors belong to, and never transcend, subordinate positionalities in the knowledge-production process. They are hardly acknowledged as co-creators of knowledge with autonomous epistemic agency. In addition, they might position themselves closer to the orientation of the researcher than that of the researched (Caretta 2015, 490). Moreover, they are often selected for their ability to enter encapsulated physical or social spaces, because they speak the local languages, or to ensure the physical safety of the researcher. Yet their participation in research as connective agents may alter the presupposition of a relationship of trust. Often, their credibility and rapport with the intended research participants are assumed, but insufficiently established, problematised, or analysed. Commenting on this, Giwa (2015, 319) refers to an essentialising of interlocuter identities. In addition, these intermediaries might possess valuable information that is not shared in the final research product, or beyond. Often, the works produced with the assistance of this situated (yet silent) labour do not divulge how these individuals were selected or what their unique cultural and social repertoires entail.

In this article, outsourcing in data generation is cast against the wider canvas of research collaboration and partnering with different stakeholders. As is demonstrated in three examples discussed later, researchers using engaged, reflexive and participatory approaches draw in different actors throughout their fieldwork encounters and beyond. Inclusivity of this nature, however, clashes with risk-averting institutional ethical clearance guidance and practices. In order to safeguard reflexive engagement against the encroachment by institutional practices, it is important to understand why reflexive engagement is needed.

Applying Theory to Practice

Oswald (2016) posits the reasons for engaged, reflexive research as having pragmatic, normative, and epistemological considerations. Pragmatically, engaged reflexivity, by focusing on the problems of representation, and by foregrounding partnerships between researchers and communities, is likely to have a greater impact in terms of policy- or practice-oriented research (Carter and Williams 2019; Jensen and Glasmeier 2010). In particular, the stance problematises the way in which the knowledge-policy process unfolds to render some people as experts, and others as research subjects, programme beneficiaries, or participants. Encountering the other through engaged reflexivity implies that researcher-researched dichotomies are challenged as false, flexible, and changing (Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018a). Further, academic-community partnering as reflexive encountering means that once-off, short-term data extraction is regarded as unacceptable voyeurism, that, according to Cooper and Orrell (2016, 117), would teach students "about institutional exploitation rather than deliberately working on solutions."

Normatively, engaged reflexivity is directed at transformation, emancipation, a commitment to discursive deconstruction, and social critique (Mejia 2015). Issues such as cognitive justice, mutual collaboration, and knowledge democracy are foregrounded to render the research process a meaningful, inclusive, mutually learning endeavour able to generate equitable outcomes (Mejia 2015). As explained above, these are the hallmarks of Mode 3 institutions.

Epistemologically, engaged reflexivity demands multiperspectival, situated, multivocal, intersubjective, and multidimensional views on a topic (Lample 2015). Reflexivity includes introspective, self-reflective efforts on the part of embedded researchers to continually question their own assumptions, orientations, and worldviews (Corlett and Mavin 2018). Pragmatic, normative, and epistemological considerations for reflexive engagement, however, must act in tandem to avoid the researchers merely doing a brief, autobiographical account of their own positionality. Taken together, these reasons resonate with the call to decolonise academe by considering whose knowledge counts (Connell et al. 2017; Tavernaro-Haidarian 2018b; Weston and Imas 2018).

Given these substantiations, what are the possibilities for reflexive encountering in postgraduate research? The temporal criticality of research production at universities (for example, pushing students through a proposal in a year, with completion of the research to follow soon after), can easily erode the kind of slow scholarship that reflexive encountering requires. Carter and Williams (2019) note that compliance with regulatory ethics enforces adherence to fixed timeframes for approvals, which in turn undermines adaptive studies of complex development problems and even stakeholders' commitment to collaboration.

Sensitivity to how intermediaries (commonly referred to as community gatekeepers4), interpreters, enumerators, fieldworkers, note-takers, interviewees and interviewers are positioned in research encounters and related meaning-making activities seldom constitutes part of tertiary research training. On the one hand, participatory approaches and feminist research orientations familiarise students with alternative ways of encountering. On the other hand, extensive ethical clearance processes, proposal adjudications and thesis examinations are focused on protecting institutions against the most obvious grievances. Important silences exist when it comes to individuals who are indirect sources of information or expedient conduits to such sources in the research process. The use of intermediaries to recruit research participants, negotiate access or to gather information might become first choices for students, supervisors and clearance committees who want to avoid any accusations of coercion, outsider interference or maleficence. Procedural, expectational ethics are championed above an embedded, emergent one based on an ongoing relationship with all research stakeholders.

Some researchers might find it wholly impossible to overcome the limitations that are imposed by their ascribed identities and reinforced by review committees who overestimate the vulnerability of certain groups and spaces. As a result, reflective, interacting activist-scholar voices become muted. Because "unsettling" methodologies are presented (and taught) as deeply risky, students and their advisers may self-regulate and self-discipline to suit the whims of an approval apparatus that seemingly favours hegemonic, clinical detachment of the researcher (Boden, Epstein, and Latimer 2009, 743).

Using Oswald's (2016) framework of reasons for engaged reflexivity, the first part of the practice-based methodology followed in this article analyses three recent postgraduate research encounters. In particular, the researcher maps out how each of these cases:

• Was able to bring together academic and practitioner perspectives (pragmatic considerations)

• Could engender engagements with others that extended beyond the primary research encounter (normative considerations)

• Was situated in and shaped by local communities and actors (epistemological considerations).

All researchers in the examples discussed below regarded their research engagements as continuous loops of building relationships, negotiating access, learning, generating data, making meaning, analysing, and feeding back insights through conversations to identify further themes to be explored. Some institutional constraints shaped their actions so that their work approximated the hybrid-liminal location of the engagement spectrum as identified by Weston and Imas (2018), as opposed to full indigenous research. The state and the economy formed part of the narrations in all three examples.

Reflexive Encountering in the Assessment of Early Childhood Development Centres

Sonnenberg (2018) analysed the problems faced by unregistered early childhood development centres (ECDCs) in poor neighbourhoods in Cape Town as part of a project about the role of ECDCs in efforts to build safer and more coherent communities. At the proposal phase of her study, she received urgent warnings from various well-intended individuals that research with children below the age of consent would never pass institutional review. This is despite the possibility of assent negotiation in the guiding policies, which state that children and other so-called vulnerable populations have the inalienable right to participate in research, and that Sonnenberg (2018) never intended to interview or observe children at the ECDCs. Institutional actors' exaggerated concerns about informed consent and assent exceeded the remit of policies and procedures. It shaped Sonnenberg's (2018) approach in limiting her ethnography to adult stakeholders, yet she remained vigilant in her efforts to capture lived experiences.

In her research journaling, which was not included in her dissertation but used as a contextual, reflexive guide, she notes her awareness of documenting lives very different from her own. Sonnenberg's (2018) embeddedness in and history with the communities in her study site shaped her careful approach to include the managers of the ECDCs as practitioners throughout her research. She conducted several focus group discussions with caregivers/parents of the children in the sampled centres and face-to-face interviews with the centre managers. Together, the researcher and the research participants uncovered important shortcomings in the policies guiding the registration of and support for ECDCs. Her research intervention encouraged greater collaboration between the caregivers/parents and the centre managers regarding registration applications, efforts to keep the children and the facilities safe, and ways to enrich the learning experience. The relationships she forged in the field endured beyond the research project.

Sonnenberg (2018) did not outsource any of her research activities. In her research, she regarded the staff and caregivers/parents at the selected ECDCs as co-creators of the data. Her report to the centre owners included visual ethnographic data, which was unfortunately disallowed for inclusion in her dissertation.

The state and the economy shaped the mundanity of childcare in the communities included in Sonnenberg's study sites. Protracted poverty, unemployment, and violence in these areas undermined the notion of community. Nevertheless, for the stakeholders, the centres symbolised safe havens. By documenting the mundane details of care centres as providing custodial care, safety, and meals for young children, the work demonstrates how macro- and micro-dynamics interact.

Reflexive Encountering with Women with Disabilities in Rural Zimbabwe

Dziva (2018) used face-to-face interviews with women living with disabilities (WWD), augmented by key informant interviews with special needs teachers, disability activists and government officials to analyse problems faced by WWD in rural Zimbabwe. One adjudicator of Dziva's (2018) work insisted that the researcher anonymise the true identities of key experts. These experts were interviewed about the implementation of policies for young women with disabilities and consented to have their real names included to lend further credibility to the study. This stance demonstrates the erroneous view that the anonymisation of participants is a universal, innate, and irrefutable good.

Dziva (2018) requested permission from his key informants to disguise their true identities to comply with this request. This created some tensions, and finally the adjudicator had to be convinced that the key informant identities were sufficiently and accurately secured. Dziva's (2018) skill in forging strong relationships with all stakeholders was duly tested. These relationships, along with extensive feedback workshops, ensured that he could blend the insights from practitioners, policy-implementors, activists, and the lived experiences of WWD into a compelling narrative.

A further ethical constraint was that the inclusion of WWD with mental disabilities (and therefore unable to grant individual research consent) was discouraged. So too was the inclusion of hearing-impaired WWD, as some reviewers were concerned that the researcher would not be proficient in sign language. Undaunted by these challenges, Dziva (2018) adjusted his inclusion criteria to capture the voices of WWD with visual, motor, and other disabilities residing in rural Zimbabwe.

No outsourcing took place, but Dziva (2018) included all research stakeholders as locally relevant commentators throughout his research, and in engagements beyond it. He developed, tested, and administered the interview schedules in Shona. Thematic analysis was undertaken on the Shona transcripted data and only translated into English later.

As the son of a WWD, Dziva (2018) reflected on how disability cannot be fully understood away from its context and that the power asymmetry in the research could never be fully resolved. This resulted in engaged research that evinces a commitment to impact, mutuality, reflexivity, and practice.

The state and the economy loomed large in the context. Despite Zimbabwe having progressive legislation for people with disabilities, the WWD in Dziva's (2018) study grappled with inaccessible public transport and buildings. Ethnographic notes and interviews tell of their daily struggles to obtain grants, land, farming knowledge, funding for trade, water, and toilet facilities. Contextual, socio-economic, historic, and gendered power relations intersect to heavily limit the functioning of these women. None of the WWD embraced victimhood, but instead resisted pity. Their push-back against abjection took various forms, such as attempting to earn an income, achieving reproductive aspirations, or working the land. Such actions, however, were often met with negative perceptions that equate their disability with inability. Through respectful encountering, Dziva (2018) was able to recommend locally informed changes for improved financing of important support structures for rural WWD in his study sites.

Reflexive Encountering with Families Receiving Social Grants in South Africa

Kiabilua (2018) researched the complex interaction between social grants and household livelihoods in two urban informal settlements in Gauteng. As a foreign South African, he was advised to have a local social worker present at each of his interviews, because of the vulnerability of the research participants and his obvious outsider status. Kiabilua (2018), having resided in the country for many years and attained citizenship, found the inclusion of a social worker (an important functionary in securing social grants for these research participants) highly problematic.

In his research journaling, Kiabilua (2018) problematised the institutional insistence that research participants must keep copies of signed informed consent sheets safe and confidential, when in reality their extreme poverty rendered such security difficult. In addition, he noted how such paperwork resembled official, coercive scrutiny of social grant recipients and initially created barriers. He resolved the matter by involving a social worker in access negotiation and as custodian of the forms. He obtained permissions directly from the government, although this involved a bewildering journey of serial submissions to various institutions with delays affecting data-gathering in a dynamic, ever-changing field of investigation. In each submission, the kind of inductive shift in data-generation strategies typical of ethnographic or qualitative work was denied as all possible steps, intended number of interviewees, and data-generation instruments had to be declared beforehand.

Kiabilua (2018) immersed himself in the two settlements, assisting affected households to apply with the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA). He often offered transport and helped with securing essential staples for needy families. Establishing lasting relationships with SASSA officials and the social worker as a research assistant enriched his data. Information from state officials were regularly fed back to the communities. The assumed language barriers never presented themselves in the field. As a foreign South African, he reflected on stark similarities and contrasts between his and his research stakeholders' experiences of marginalisation. The data offered policy-related suggestions to counter intergenerational dependence on social assistance.

These three recent examples of postgraduate research underscore the contention that institutional regulatory systems shape postgraduate research. In each of the three examples, the institutional impulse was to uphold prescriptive preferences for detached knowledge production. It took considerable effort for all three researchers to operate within such restrictions and to persist in engaged, community-based research. Respectful encountering meant that they had to negotiate complex interpersonal relationships both in the field and within academe.

In all three examples the researchers left themselves open to be changed by mutual, immanent relationships that developed at various moments in their research encounters and beyond. In addition, they interpreted reflexivity as embodied encountering in the field. They entered the field as embodied persons confronted by concretely lived experiences, such as being lifted into a train by a stranger (Dziva 2018), sending a grandchild to a care centre chiefly due to food insecurity (Sonnenberg 2018), or struggling through a job application without a secondary school education (Kiabilua 2018). Witnessing and sharing such tacit examples of strategic actions became deeply meaningful ways to better understand the participants and the issues they were researching. All three these researchers took time and effort to build trusting relationships in the field and beyond.

From these examples in practice, it can be argued that participatory knowledge tools in Development Studies are taught, yet not always fully practised at the postgraduate levels. They thus become methodologies that privilege autonomy and accept the reflexive, inductive project only in the abstract. Although focusing on the problems of translating information into English, Dar's (2018, 4) observations are apt here- explaining how oversights regarding truly transformative practices can create "development subjects" that are rendered "(un)knowable and (un)recognizable," yet, when for example assisting in report writing for projects "dehumanize and un-culture their experiences of working in the field."

Dawson and Sinwell (2012, 179 and 186) mention two related problems that stem from such neglect of true participatory methods in academe. The first is that communities are easily targeted as sources of research information, but just as easily dismissed as evaluators and co-producers of research. The author contends that this extends to exaggerated categories of externally imposed vulnerability in research (as illustrated in the three critical incidents mentioned above) that cause postgraduate scholarship to retract from this forbidden terrain. Ironically, the exaggerated notion of vulnerability would render many potential topics and research participants off limits in Development Studies. The second is that a false binary is upheld between academic scholarship and activism, with the latter misrecognised as a form of knowledge in its own right. Lewis (2012, 229) adds, "We must have a commitment to others we research with, as well as a commitment to act against oppression and domination and for social change." As illustrated in the above examples, this trend makes it difficult to teach students public, organic or embedded intellectual practice. Moreover, "mission creep" (Babb, Birk, and Carfagna 2017, 100) in what ERCs advise can capture specific topics and methods for Development Studies research whilst rendering others inaccessible in an imposed, exaggerated "vulnerability" category.

Rapid Quantitative Assessment of Postgraduate Research Production: Materials and Results

Beyond the three examples, a rapid quantitative assessment was undertaken. The material for the rapid assessment was sourced from an online repository of master' s dissertations and doctoral theses in the discipline of Development Studies produced between 2013 and 2017 (see Figure 1). Methodologically speaking, this is the quantitative analysis of existing data (or secondary analysis of data following Bryman 2012, 310-328; Connell et al. 2017, 28) used to augment the above practice-based analysis of three examples.

The limitations of the database used for the quantitative rapid assessment include incomplete records due to administrative shortages and backlogs (for example, no 2018 documentation existed), slight differences between date of completion and date of upload and some records not submitted.

Figure 1 shows that of the 64 postgraduate outputs listed on the repository, 41 (64.1%) were master's dissertations and 23 (35.9%) were doctoral theses. There was a bumper crop of 20 dissertations delivered in 2014, and no doctoral thesis listed on the repository for 2017. This should not be equated with degrees successfully completed, due to the limitations in the repository as explained earlier. In order to show general trends, the outputs for 2013 to 2014 and for 2015 to 2017 are grouped in Table 1 by topic, country of investigation and research design.

Table 1 shows that these outputs spanned a range of topics, with community development, the role of civil society or non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in development and state-civil society partnerships accounting for just more than a quarter (29.7%) of the outputs. Although topics intersect and wax and wane in popularity, the focus on participatory development as an area of interest stands out. Moreover, most of the topics denote students' interests in and proclivities to work with so-called vulnerable areas, groups, people or sectors. In the last five years, graduates were delivered with proven interest and skills in this important area of Development Studies. However, should the "mission creep" of ERCs increase as discussed above, this area stands to lose the most.

South Africa (31.2%), Ethiopia (17.2%), and Zimbabwe (15.6%) accounted for 64% of the investigations, with three outputs attempting comparisons of data generated in more than one country. Because of this situatedness of postgraduate research production in the continent and the above-mentioned popularity of participatory gazes, the time is rife for a discipline-specific guidance in emergent ethics and activist-scholarship research able to command its own place and recognition. Moreover, the cultural and political logic related to the space from where the research is produced needs to be acknowledged.

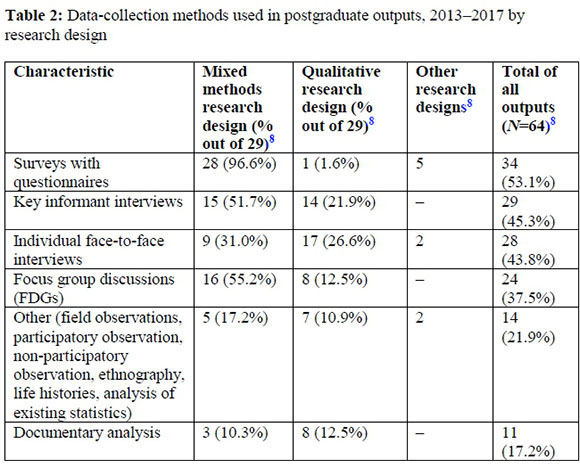

The most popular choice of approach was mixed methods design (45.3%) followed by qualitative designs (45.3%), with PAR and quantitative designs rarely opted for. Both mixed methods and qualitative approaches favour researcher reflectivity, emergent strategies and flexible, open orientations in the data collection, analysis and dissemination strategies. Preserving and strengthening these central orientations in the discipline are thus crucially important. Read in conjunction with the types of topics selected, it can be concluded that the methodological impulses of these students lean towards historical-hermeneutic and critical stances that tend to reject value-free, objective and disinterested inquiry. In Table 2 below, the analysis of the outputs is presented by design.

Table 2 shows the creative mix of data-collection methods. Postgraduate students combined sample surveys (used in 53.1% of all outputs) with focus group discussions (employed in 43.8% of all outputs), key informant interviews (used in 45.3% of all outputs), individual, face-to-face interviews (used in 43.8% of all outputs) and other methods (see Table 2) to gather data. Out of all the outputs, documentary analysis was used in 17.2% of the cases. Finer-grained analysis is not shown in Table 2 but encompasses how surveys were structured (administered as self-completion, e-mailed or enumerator-administered tools) and constituted the quantitative element in all but one of the mixed methods studies. Only one qualitative study relied on a semi-structured, emailed survey questionnaire strategy to collect data. These scholars thus demonstrated skills in using a range of sources to represent complex topics comprehensively.

For the most part, the qualitative researchers opted for individual face-to-face interviews (26.6% of all qualitative research designs) and key informant interviews (21.9% of all qualitative research designs). The popularity of FGDs in both mixed methods and qualitative research designs demonstrates an embrace of communal knowledge co-creation and collaborative meaning-making, yet the findings below regarding acknowledgement of this sentiment through extensive reporting on co-workers' and own positionalities reveal that much still needs to be done to foster research grounded in full reciprocity.

Table 3 shows that the majority of outputs (82.8%) was based on data collection done in a language (or in some cases various languages) other than English. In all instances, the researcher had an English reference questionnaire for proposal and ethical clearance purposes and then a translated version for the data collection. A fair amount of translation from vernacular data to English therefore takes place. The practice is fairly routinised and shows a propensity to value local forms of knowledge expressed in people's own languages. Lumadi (2008, 28), in his extensive investigation of postgraduate supervisionary practices, notes "students who conduct research in English as their second language experience problems in writing up their research dissertations and theses in English." Nevertheless, few of the dissertations and theses dwelled much on this issue of translation and the problems it might pose for accurate and respectful representation. Moreover, it shows a lack of skilling students to write about the inherent problems when interpretive authority (Pickering and Kara 2017) is located chiefly (or solely) in the researcher. When particular knowledge creation and ethical practices are institutionalised without a critical examination of their claims to immersion in the lives of those outside the institution, it may stifle progress in advancing claims to participatory methods.

Table 3 further shows that co-workers are mentioned in 42.2% of the outputs. The possibility that the other studies fail to acknowledge the use of co-workers should be considered. Different labels were used to describe such intellectual labourers, such as research assistants, enumerators or note-takers. They were used to negotiate access to the research site or to recruit participants, for their ability to speak the local languages, because of their social standing in the community or chosen research site, because they were women (in one case), as implementers of data-collection instruments designed by the researcher or to take notes during FGDs. In terms of finer-grained analysis (not shown in Table 3), co-workers were most often mentioned in studies that relied on larger samples, simultaneous collection of data through numerous methods, or where multi-site data collection was required. The largest number of such co-workers employed were 10 enumerators for one study, but more often two to four assistants were used. Few studies gave full details about the selection, identities, social characteristics or post-data collection involvement of these co-workers. While a few mentioned that they "trained" the recruited co-worker(s), none gave details on any form of remuneration. They were often consigned to the acknowledgements section where their names were set adrift among those of friends, family members, people from the research site, students or other co-workers.

As shown in Table 3, only about a third (32.8%) of the outputs included a reflective account by the researcher with about two thirds of all the qualitative research designs (62.1% out of 29) including no reflective account whatsoever. It would seem that this important part of the knowledge-production process is neglected in postgraduate production. The relational embeddedness of Development Studies means that researchers' own positionalities, self-awareness and self-disclosure should not be downplayed. In qualitative research renderings, claims to narrative, collaborative and relational knowing through in-depth interviews and FGDs should be substantiated with researcher reflective accounts. Below, some proposals to address this deficit are offered.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The article outlined the case for an urgent switch from anticipatory, contractual ethics and regulatory systems to relational, iterative, liberatory, mindful and affirming praxis in research guidance and training. Three recent examples from own practice and a rapid quantitative assessment of data from postgraduate production underscore the contention that steps should be taken to avoid impoverishment of the discipline through regulatory systems that might deprive all knowledge workers of the possibility of respectful, collaborative encountering. The slow "mission creep" of regulatory systems has been demonstrated as an integral part of the political economy of knowledge production. In each of the three critical incidents, the institutional impulse was to uphold prescriptive preferences for detached knowledge production and to foreclose attempts to question these. The rapid assessment data from successful dissertations and theses confirmed how students learn to master these codes of power by maintaining researcher-led interpretive and translative authority and undervaluing reflections on their own positionalities.

Researchers in and teachers of Development Studies can shape the standards to which the work is held. Subject associations are best placed to advocate for trans-institutional review boards that resist regulatory impulses that stifle alternative methodologies. This would require careful checks and balances against the restrictive practices implied by overzealous review committees, the fetishisation of approaches and the impulse to turn knowledge production into profit. Allowing these practices to spread means that students are taught to capitalise on their (and their supervisors') intellectual property so that scarce research funds circulate inside institutions, but hardly reach outside it. In this regard, Woods (2009, 230) suggests that "universities can create multiple spaces (i.e., in community presentations, videos, or newsletters, and academic journals) for the lived experience of all partners to be heard and valued" and urges us to "explore the subterranean caverns that shelter the wellsprings of dreams during the seasons when hope can't be found."

This imperative to tear down insider-outsider polarities is crucial for research in Development Studies, particularly for two important reasons. Firstly, because an outsider status is inevitable for those working in particular geographic and socioeconomic localities characterised by specific cultural traits and linguistic repertoires (Scheyvens 2014, 2). However, researcher-researched-activist-scholar positionalities are not fixed, but fluid and subject to change at multiple instances over the course of dynamic, contingent, creative and spontaneous knowledge production and sharing processes (Faria and Mollett 2016; Razon and Ross 2012). Secondly, because the discipline concerns itself with the notions of impact and accountability in terms of informing policy, practice and transformatory action (Sumner and Tribe 2008, 761-62).

In this regard, the four dimensions of social justice research as articulated by Pham and Jones (2005, 2-3 and 5) are relevant, namely for researchers to be self-reflexive in the knowledge-production process, to ensure equal dialogue with all research stakeholders, to reveal marginalised knowledges and to reconceptualise what validity means.

Vigilance is needed to nurture engaged work that is less corrosive of community engagement than those based on extraction from a distance (be that with or without the help of interlocuters). Researchers and postgraduate supervisors in the social sciences shape the standards to which the work is held. Their tasks extend to resisting restrictions imposed on engaged, reflexive work by overzealous review committees, the fetishisation of approaches and the impulse to turn knowledge production into profit. Beyond incentivised academic journals, universities should create multiple platforms for sharing research such as community presentations, videos, and newsletters. Crabtree (2019) and Lample (2015) document how their reflexive encountering included observance of institutional ethics whilst being deeply respectful of local customs and adopting the former in situ to ensure respectful engagement.

Mode 3 institutions measure research impact in terms of its ability to inform policy, practice, partnerships, and transformatory action towards social justice. Barnes (2019, 307) aptly notes that participatory methodologies do not automatically translate into social justice. Instead, Barnes (2019) contends that the way in which engaged research is conducted can enable transformative resource distribution for the sake of distributive justice, changes to social policy as part of procedural justice, and can bestow dignity on the marginalised to result in interactional justice. Sonnenberg (2018), Dziva (2018), and Kiabilua (2018) worked towards all three dimensions of social justice in their postgraduate research. Although outsourcing large parts of their extensive fieldwork was tempting, none of the three researchers opted for this. They encountered institutional obstacles and engaged reflexively with their own positionalities and those of their knowledge co-workers who acted as gatekeepers, interviewees, key informants, and state actors.

Importantly, in all three cases, the researchers resisted the finalising, stigmatising, or pathologising definitions of their research participants as WWD embracing victimhood (Dziva 2018), unregistered ECDCs managers as defiantly neglectful (Sonnenberg 2018), or social grant recipients as draining state resources (Kiabilua 2018). In each case, research participants were conscientised to understand their own potential as social actors able to shape and resist such definitions. Service providers, in turn, were conscientised to see their clients or service recipients in a different light. Engaged reflexivity enabled all three these researchers to speak of, speak with and speak for so-called vulnerable groups.

Interventions to secure the future of reflexive encountering in postgraduate research in Development Studies would require four related interventions. Firstly, recruiting, retaining, and acknowledging activist-scholars in institutions and as serving members of ERCs can establish models for engaged knowledge co-creation. Campbell and Carayannis (2016), in this regard, encourage cross-career, multi-employment, or multiple-agency staffing to ensure a smooth movement between academe and practice. Another important consideration is to develop students' skills for ethics in practice by inviting practitioners into co-supervision mentorship roles in situated research-partnering networks.

Secondly, transformation in academic culture is needed so that creative improvisation in research and in university-community partnerships can persist and evolve. In this regard, institutional incentivisation of so-called community engagement projects that must produce revenue-bestowing output reifies the "otherness" of communities. Transformation of this kind in Mode 3 universities offers invigorating possibilities for hope, recovery, mobilisation, transformation, restoration, and healing.

Thirdly, Mode 3 universities should guard against overly legalistic, paternalistic, risk-averse practices in institutional ERCs. Research as empowerment cannot flourish in a risk-management system that disempowers. Communities should be included as research collaborators instead of seen as mere victims-in-waiting (Conner, Copland, and Owen 2018, 400-401).

Fourthly, curriculum changes in favour of accredited community volunteering for social scientists is required. This must be backed by fostering integrity-with-humility in researchers-in-training and those who regulate and adjudicate their work. The latter extends to training students on managing relationships in the situatedness of research practice to value the labour of all involved.

The context of postgraduate research guidance and production is fragmented and fast-paced, meaning that those who want to work within the engaged, reflexive ethos must create collective spaces for innovative work. Students must be adequately trained and skilled for research partnership brokering to address complex problems related to human flourishing. Greater effort is needed to secure and nurture engaged reflexivity in postgraduate training and beyond.

There is no better time than the present to effect these changes. Calls by the youth for education that expands their capacities to impact the world they inhabit signals a powerful groundswell against academic practices that "reproduce themselves through a parasitical relationship with the collective labour of communities" (Bell and Pahl 2018, 110).

References

Babb, S., L. Birk, and L. Carfagna. 2017. "Standard Bearers: Qualitative Sociologists' Experiences with IRB Regulation." The American Sociologist 48 (1): 86-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-016-9331-z. [ Links ]

Baloy, N. J. K., S. Sabati, and R. D. Glass, eds. 2016. Unsettling Research Ethics: A Collaborative Conference Report. Santa Cruz, CA: UC Centre for Collaborative Research for an Equitable California. [ Links ]

Barnes, B. R. 2019. "Transformative Mixed Methods Research in South Africa: Contributions to Social Justice." In Transforming Research Methods in The Social Sciences: Case Studies from South Africa, edited by S. Laher, A. Fynn, and S. Kramer, 303-16. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. https://doi.org/10.18772/22019032750.24. [ Links ]

Bell, D. M., and K. Pahl. 2018. "Co-Production: Towards a Utopian Approach." International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21 (1): 105-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1348581. [ Links ]

Boden, R., D. Epstein, and J. Latimer. 2009. "Accounting for Ethics or Programmes for Conduct? The Brave New World of Research Ethics Committees." The Sociological Review 57 (4): 727-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954x.2009.01869.x. [ Links ]

Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Campbell, D. F. J., and E. G. Carayannis. 2016. "Epistemic Governance and Epistemic Innovation Policy in Higher Education." Technology, Innovation, and Education 2 (2): 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40660-016-0008-2. [ Links ]

Caretta, M. A. 2015. "Situated Knowledge in Cross-Cultural, Cross-Language Research: A Collaborative Reflexive Analysis of Researcher, Assistant and Participant Subjectivities." Qualitative Research 15 (4): 489-505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794114543404. [ Links ]

Carter, L., and L. Williams. 2019. "Ethics to Match Complexity in Agricultural Research for Development." Development in Practice 29 (7): 912-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1606159. [ Links ]

Connell, R., F. Collyer, J. Maia, and R. Morrell. 2017. "Toward A Global Sociology of Knowledge: Post-Colonial Realities and Intellectual Practices." International Sociology 32 (1): 21-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580916676913. [ Links ]

Conner, J., S. Copland, and J. Owen. 2018. "The Infantilized Researcher and Research Subject: Ethics, Consent and Risk." Qualitative Research 18 (4): 400-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117730686. [ Links ]

Cooper, L., and J. Orrell. 2016. "University and Community Engagement: Towards a Partnership Based on Deliberate Reciprocity." In Educating the Deliberate Professional: Preparing for Future Practices, Professional and Practice-Based Learning, Vol. 17, edited by F. Trede, and C. McEwen, 107-23. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32958-18. [ Links ]

Corlett, S., and S. Mavin. 2018. "Reflexivity and Researcher Positionality." In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: History and Traditions, edited by C. Cassell, A. L. Cunliffe and G. Grandy, 377-98. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526430212.n23. [ Links ]

Cornwall, A. 2003. "Whose Voices? Whose Choices? Reflections on Gender and Participatory Development." World Development 31 (8): 1325-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0305-750x(03)00086-x. [ Links ]

Crabtree, S. M. 2019. "Reflecting on Reflexivity in Development Studies Research." Development in Practice 29 (7): 927-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2019.1593319. [ Links ]

Dar, S. 2018. "De-Colonizing the Boundary-Object." Organization Studies 39 (4): 565-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840617708003. [ Links ]

Dawson, M. C., and L. Sinwell. 2012. "Ethical and Political Challenges of Participatory Action Research in the Academy: Reflections on Social Movements and Knowledge Production in South Africa." Social Movement Studies 11 (2): 177-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2012.664900. [ Links ]

Dean, J. 2017. Doing Reflexivity: An Introduction. Bristol: Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t89347. [ Links ]

Dziva, C. 2018. "Advancing the Rights of Rural Women with Disabilities in Zimbabwe: Challenges and Opportunities for the Twenty First Century." PhD diss., University of South Africa. Accessed November 21, 2019. http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/24931/thesis_cowen_d.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [ Links ]

Faria, C., and S. Mollett. 2016. "Critical Feminist Reflexivity and the Politics of Whiteness in the 'Field'." Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 23 (1): 79-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2014.958065. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. [ Links ]

Geleta, E. B. 2014. "The Politics of Identity and Methodology in African Development Ethnography." Qualitative Research 14 (1): 131-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468469. [ Links ]

Giwa, A. 2015. "Insider/Outsider Issues for Development Researchers from the Global South." Geography Compass 9 (6): 316-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12219. [ Links ]

González-López, G. 2011. "Mindful Ethics: Comments on Informant-Centered Practices in Sociological Research." Qualitative Sociology 34: 447-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-011-9199-8. [ Links ]

Hountondji, P. J. 2009. "Knowledge of Africa, Knowledge by Africans: Two Perspectives on African Studies." Revista Critica de Ciências Sociais Annual Review 1: 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4000/rccsar.174. [ Links ]

Jensen, K. B., and A. K. Glasmeier. 2010. "Policy, Research Design and the Socially Situated Researcher." In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Geography, edited by D. DeLyser, S. Herbert, S. Aitken, M. Crang, and L. McDowell, 82-93. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857021090.n6. [ Links ]

Keane, M., C. Khupe, and B. Muza. 2016. "It Matters Who You Are: Indigenous Knowledge Research and Researchers." Education as Change 20 (2): 163-83. https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/913. [ Links ]

Kiabilua, P. N. 2018. "The Impact of Social Assistance on Human Capacity Development: A Study Amongst Households Affected by HIV and AIDS in South Africa." PhD diss., University of South Africa. http://hdl.handle.net/10500/25360. [ Links ]

Lample, E. 2015. "Watering the Tree of Science: Science Education, Local Knowledge, and Agency in Zambia's PSA Program." PhD diss., Vanderbilt University. [ Links ]

Lewis, A. G. 2012. "Ethics, Activism and the Anti-Colonial: Social Movement Research as Resistance." Social Movement Studies 11 (2): 227-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2012.664903. [ Links ]

Lumadi, W. M. 2008. "The Pedagogy of Postgraduate Research Supervision and Its Complexities." College Teaching Methods and Styles Journal 4 (11): 25-32. https://doi.org/10.19030/ctms.v4i11.5577. [ Links ]

Marshall, C., and G. B. Rossman. 2006. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

May, T., and B. Perry. 2011. "The Political Economy of Knowledge: Relevance, Excellence and Reflexivity." In Social Research and Reflexivity: Content, Consequences and Context, edited by T. May, and B. Perry, 125-52. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Mejia, A. P. 2015. "You Better Check Your Method Before You Wreck Your Method: Challenging and Transforming Photovoice." In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research, edited by H. Bradbury, 665-72. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473921290.n69. [ Links ]

Oswald, K. 2016. Interrogating an Engaged Excellence Approach to Research. Brighton: Institute for Development Studies. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/12685. [ Links ]

Pearson, A. L., and S. B. Paige. 2012. "Experiences and Ethics of Mindful Reciprocity while Conducting Research in Sub-Saharan Africa." African Geographical Review 31 (1): 7275. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2012.679464. [ Links ]

Pham, T. L., and N. Jones. 2005. "The Ethics of Research Reciprocity: Making Children's Voices Heard in Poverty Reduction Policy Making in Vietnam." Young Lives Working Paper No. 25. London: Save the Children UK. [ Links ]

Pickering, L., and H. Kara. 2017. "Presenting and Reporting Others: Towards an Ethics of Engagement." In "New Directions in Qualitative Research Ethics," edited by H. Kara and L. Pickering, special issue, International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20 (3): 299-309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1287875. [ Links ]

Ramaley, J. A. 2016. "Collaboration in An Era of Change: New Forms of Community Problem-Solving." Metropolitan Universities 27 (1): 3-24. [ Links ]

Razon, N., and K. Ross. 2012. "Negotiating Fluid Identities: Alliance-Building in Qualitative Interviews." Qualitative Inquiry 18 (6): 494-503. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800412442816. [ Links ]

Scheyvens, R. 2014. Development Fieldwork: A Practical Guide. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473921801. [ Links ]

Schneider, C. E. 2015. The Censor's Hand: The Misregulation of Human-Subject Research. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262028912.001.0001. [ Links ]

Sonnenberg, E. S. 2018. "Social Context, Social Cohesion and Interventions: An Assessment of Early Childhood Development (ECD) Programmes in Selected Communities in the Cape Flats." MA diss., University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Spivak, G. C. 1988. "Can the Subaltern Speak?" In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by C. Nelson and L. Grossberg, 271-313. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-19059-1_20. [ Links ]

Sumner, A., and M. Tribe. 2008. "What Could Development Studies Be?" Development in Practice 18 (6): 755-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520802386603. [ Links ]

Tavernaro-Haidarian, L. 2018a. "Deliberative Epistemology: Towards an Ubuntu-Based Epistemology That Accounts for a Priori Knowledge and Objective Truth." South African Journal of Philosophy 37 (2): 229-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/02580136.2018.1470374. [ Links ]

Tavernaro-Haidarian, L. 2018b. "Why Efforts to Decolonise Can Deepen Coloniality and What Ubuntu Can Do to Help." Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies 32 (5-6): 104-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2018.1560341. [ Links ]

Thompson, J. 2018. "'Shared Intelligibility' and Two Reflexive Strategies as Methods of Supporting 'Responsible Decisions' in a Hermeneutic Phenomenological Study." International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21 (5): 575-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1454641. [ Links ]

Van den Hoonaard, W. C. 2011. The Seduction of Ethics: Transforming the Social Sciences. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Weston, A., and J. M. Imas. 2018. "Resisting Colonization in Business and Management Studies: From Postcolonialism to Decolonization." In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: History and Traditions, edited by C. Cassell, A. L. Cunliffe, and G. Grandy, 119-35. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526430212.n8. [ Links ]

Woods, C. 2009. "Katrina's World: Blues, Bourbon, and the Return to the Source." American Quarterly 61 (3): 427-53. [ Links ]

1 This convention, to refer to oneself in the third person, is a result of conservative repetition of prescripts to social researchers in South Africa. Although the researcher would have preferred the I-voice, bending to this prescript perversely underscores the very argument about control over knowledge work (or "extraversion" following Hountondji [2009]) that this article makes.

2 Molar power is referenced here as a force that codes and categorises in order to control.

3 May and Perry (2011) only distinguish Mode 1 and Mode 2 universities, with the latter characterised by transdisciplinary, context-driven, socially accountable research foci. Mode 3 as envisaged by Campbell and Carayannis (2016) finds articulation in May and Perry's (2011) notion of excellent relevance.

4 Gatekeepers can, of course, also include adult parents or legal guardians who are requested to provide consent for research participation as a prerequisite to the assent of the legal minor who is the intended research participant. This is an example of an intermediary in research constructed wholly by the requirements set by procedural ethical consent in research participation.

5 Not all per cent distributions summate to 100.0, due to rounding errors.

6 Topics were coded from the titles and the keywords indicated in the abstracts of the outputs. In all cases, the particular study held additional time, spatial, theoretical or philosophical parameters that made it wider than these categories may reflect. In many instances, the output covered a range of objectives pertinent to the discipline.

7 This is based on the individual researcher's own categorisation of their research designs. In a post-positivist era, the distinctions between quantitative and qualitative approaches have been blurred and in most of these outputs, both qualitative and quantitative elements can be noticed, although in all cases the researchers argue in favour of their chosen design's emphasis.

8 Here the percentage exceeds 100.0 as students combined methods. The "other" research design entries are not calculated as percentages due to the small number of cases (N=6).

9 Not all per cent distributions summate to 100.0, due to rounding errors.