Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.22 n.2 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/3582

ARTICLES

We shall fight, we shall win: An activist history of mass education in India

Nisha Thapliyal

University of Newcastle, Australia nisha.thapliyal@newcastle.edu.au. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3081-6310

ABSTRACT

Social movements for public education challenge neoliberal claims that there is no alternative to the market-to the inevitability of the privatisation of education. This article analyses the ways in which education activists in India deploy critical histories in their struggles for a public and common school system. It is empirically grounded in a critical analysis of a 2016 activist documentary film called We Shall Fight, We Shall Win. The film was produced by a grassroots activist coalition called the All India Forum for the Right to Education (AIFRTE) as part of their ongoing struggles against the commercialisation and communalisation of education. The film provides a rare opportunity to explore different kinds of historical knowledge produced in collective struggles for equity and social justice in India. In particular, this analysis examines the ways in which activists link the past and the present to challenge and decentre privatised narratives of education and development. In doing so, this research offers situated insights into the critical histories that inspire, sustain and co-construct one site of ongoing collective struggle for public education in India.

Keywords: critical history; social movements; activist knowledge; public education; India

If a room in your house is on fire, can you sleep in the next room? If there is a dead body in one room of your house, can you sing songs in the next room? If yes, then I have nothing to say to you. (Sarveshwar Dayal Saxena, poet 1)

Introduction

The 2009 Right to Free and Compulsory Education Act (hereafter referred to as the RTE Act) came into effect 60 years after India gained independence from British colonial rule. During this time, the Indian state had failed to create the conditions for universal, equitable, and meaningful schooling for all children. Furthermore, educational discrimination, inequality and exclusion were disproportionately experienced by social groups historically excluded from education. Disaggregated statistics reveal that the historically marginalised groups of Scheduled Castes (SCs, hereafter referred to as Dalits) and Scheduled Tribes (STs, hereafter referred to as Adivasis), who together comprise a quarter of the country's population, have the worst income-poverty and human development indicators of the entire population (PROBE, 1999; PROBE 2006). Children from these groups along with Muslims and poor girls across caste, religion, and rural-urban categories remain significantly less likely to complete five years of primary education, let alone access any kind of tertiary education (see e.g. Chopra and Jeffery 2005; Matin et al. 2013; Saxena 2012). The struggle for the right to education has now lasted close to two centuries and has become intrinsic to the work of imagining a postfeudal, postcolonial and postneoliberal India.

This article provides a critical qualitative analysis of a 2016 activist documentary film called We Shall Fight, We Shall Win made by a coalition of grassroots activists, the All India Forum for the Right to Education (AIFRTE). It draws on critical, postcolonial and social movement scholarship on education and activist media to explore the ways in which progressive activists construct an alternative history of mass education in India through the silenced and marginalised perspectives of public intellectuals and subaltern groups.

This article is part of a broader ongoing research project on social movements for public education in the global South which includes a qualitative case study of the AIFRTE. The analysis in this article is empirically based on the 56-minute documentary film, interviews with 10 AIFRTE national and regional activists, as well as print and online newsletters, news articles and opinion pieces, and other documents and media produced by the AIFRTE since its inception in 2009. In the next two sections, I provide a conceptual framework for activist histories and a brief historical overview of mass education in India. Next, I discuss the critical and loosely chronological historical narrative which is constructed through multiple perspectives and mediums over approximately 40 minutes of the film. The paper concludes with a reflection on the implications of activist knowledge production for ongoing educational struggles and the democratisation of knowledge.

A History of Education and Inequality in India

The distribution of high quality education in India can be imagined as an inverted, multi-tiered pyramid topped by a small group of elite schools made up of government schools that serve the children of civil servants and similarly highly selective private schools (Thapliyal 2016).2This small group of elite schools protect "avenues of sponsored mobility" to exclusive higher education institutions and elite jobs (Kumar 1992, 52). As I have argued elsewhere, the vast majority of poor, Muslim and Dalit/SC Indian children face a choiceless choice between barely functioning government schools, unregulated budget private schools, and non-formal education (Thapliyal 2016). I will provide a brief historical overview of the factors and forces that contributed to the creation and maintenance of this deeply unequal educational system, the passage of the RTE Act and the emergence of the AIFRTE coalition.

A History of Unequal Education

The scholarship on colonial and postcolonial schooling has underlined that the establishment of the Indian mass education system reproduced hierarchical constructions of social difference and legitimised deeply stratified and oppressive social arrangements. The introduction of the British colonial class-based system of education, with a few exceptions,3 did little to interrupt historical forms of structural oppression constituted by caste, gender, poverty, indigeneity and disability. Kumar (1992) notes the symbiotic interaction between colonial utilitarian thinking and efforts by Indian aristocrats, landed/propertied and professional classes to protect their privileged caste and class-based positions in the established social structure. This group of elites actively thwarted efforts to expand schooling on the grounds that the best education for poor children was to work, earn and learn a trade (Balagopalan 2014; Rao 2013).

Thus, "quality for a few" dominated the logic of educational expansion in independent India (Saxena 2012). Despite a plethora of alternatives for anti-colonial, anti-capitalist and anti-casteist education constructed by eminent indigenous thinkers such as Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, Sri Aurobindo, and Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, the elite-ruled Indian state adopted a human capital approach to mass schooling (Kumar 2006). Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru's visions of a scientific, liberal, and socialist India were quickly sacrificed to the political demands of the ruling landed and industrialist classes for economic growth and trickle-down development (Kumar 2006). After Nehru's death, the rhetoric of socialism and state-driven equity policies faded rapidly from the vocabulary of leaders across the political spectrum.

In the nineties, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, grandson of Jawaharlal Nehru, implemented structural adjustment and liberalisation of the economy under the guidance of the World Bank. During his tenure, the 1986 National Plan of Education introduced and institutionalised another tier in the education system under the rhetoric of public-private partnerships (PPPs). The World Bank-inspired District Primary Education Programme (DPEP) established a parallel system of low quality, non-formal education for so-called hard-to-reach children, which was delivered by untrained and paraprofessional teachers and the non-governmental sector (Kumar, Priyam, and Saxena 2001).4 Other "targeted" initiatives such as selective government schools for meritorious students from disadvantaged groups (primarily girls and SC/ST) (the Navodaya or Model Schools) and hostels (residential schools) introduced new tiers of inequality (Saxena 2012).

Access to high quality education delivered predominantly by fee-charging private schools continues to be predicated on social and economic privilege (Nambissan 2010). The current demographic makeup of consumers of private (primary and higher) education reflects small and situated shifts in social hierarchies such as the ascendance of some lower caste but traditionally landholding groups (e.g. in south India) as well as the increasing political power of educated urban middle classes (Chopra and Jeffery 2005; Fernandes 2006).

The steady withdrawal of the state from public education since the 1980s has accelerated educational privatisation. By the late 1990s, a shadow education system comprised mainly of individual private tutors (working and retired school teachers) had expanded into big brand, highly organised and profitable coaching and tutoring centres across India (Majumdar 2012).

There was an explosion of virtually unregulated English-medium "budget" or low-cost forprofit private schools in urban and rural areas (extensively documented by Prachi Srivastava). As a direct consequence of these market-oriented reforms, government schools, particularly in rural areas, emptied out of all students except children without purchasing power (PROBE 2006).

In 2009, the government sent a loud and clear signal to the global privatisation lobby through the passage of the RTE Act. In contravention of the Indian Constitution, mandates from the Supreme Court of India, and the international human rights framework, the RTE Act adopted a diluted conception of the right to education. Instead of universal access, the practical effect of this historical legislation was to promote privatisation through a de facto voucher system and to institutionalise segregated and unequal education. It disregarded core principles of children's rights and rights in education and paid lip service to the concept of child-centred education (for an in-depth analysis, see Thapliyal 2012). Furthermore, as an unfunded mandate, the few progressive provisions lack the power to disrupt a dominant discourse of schooling (public and private) which continues to place the responsibility for success and failure on children and their social backgrounds (most recently, see e.g. Morrow 2013) and teachers (see e.g. Batra 2012). Today India is a key hunting ground for education entrepreneurs, venture capitalists and philanthrocapitalists including the Teach for All network, the Pearson Affordable Learning Fund, the International Finance Corporation and the Gates Foundation (Kamat, Spreen, and Jonnalagadda 2016; Nambissan and Ball 2010; Vivanki 2014).

AIFRTE, RTE and the Struggle for Public Education

The AIFRTE was officially established in 2009 in response to the passage of the 2009 Right to Free and Compulsory Education Act. The coalition includes community-based organisations, university student and teacher unions, social movements as well as individual educators, public intellectuals, parents, students and concerned citizens. The majority of these activist organisations have spent decades in collective struggles for human rights, social justice, and democracy-for Dalits, Adivasis, women, farmers, and people with disabilities. They are currently located in 20 out of 29 Indian states.5 In order to maintain autonomy, AIFRTE does not accept funding from corporate or development agency sources. Since inception, the AIFRTE has opposed the ongoing commercialisation, commodification, and desecularisation of public education. Its goals are captured in one of its favoured slogans: "Education is not for sale, it is a people's right."

Their educational vision is centred on a fully free and state-funded Common Education System based on Constitutional values of democracy, egalitarianism, socialism, and secularism (Thapliyal 2014). In addition, the coalition has advocated for schooling that is responsive to the linguistic and cultural diversity that makes up Indian society. This vision is located in alternative conceptions of development that are "pro-people" rather than pro-market (AIFRTE 2010). Its organisational structure as described on the AIFRTE website strives not to be "rigid, specific and demanding" in order to be responsive to the diversity that characterises the coalition's membership. A common platform was developed in 2012 called the Chennai Declaration which sets out the broad vision and common goals for the coalition while allowing for state-specific priorities and strategies (AIFRTE 2012).6

In 2014, AIFRTE decided to organise a National March for Education (Shiksha Sangarsh Yatra). Activists would travel-by road-from all over the country to the central Indian city of Bhopal, the site of one of the world's worst industrial disasters-the deadly Union Carbide gas leak in 1984. During their journey, activists would seek to raise awareness and stimulate public debate about key challenges facing the Indian public education system, including privatisation and the growing right-wing assault on cultural diversity and secularism. The march was also held in solidarity with two other ongoing people's struggles: the three decadeslong struggle for justice and compensation for the people of Bhopal, and north-eastern movements to repeal the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) that gives security forces unrestrained powers for search, arrest, and the use of deadly force against persons suspected of acting against the Indian state. The march was launched on November 2, 2014 from five points that represented the size and diversity of the Indian subcontinent including Jammu in the North, Mhapsa in the west, Kanyakumari in the south, Bhubhaneshwar in the east, and Malom in the northeast. One month later, approximately 2000 activists arrived in Bhopal for three days of public meetings and cultural performances.

One of the goals of We Shall Fight, We Shall Win was to document the National March and highlight the coalition's scope and internal diversity. A related goal was to connect the current struggle to historical movements "[as] a way of recovering 100 years of protest in our own Yatra (march)" (Madhu Prasad, personal interview, 2016).

The film was made by Avakash Nirmitti, a not-for-profit group of independent documentary film-makers under the guidance of a committee comprising three members from the AIFRTE presidium, secretariat, and national executive, including Professor Madhu Prashad, Lokesh Malti Prakash (journalist) and Professor Harjinder Singh respectively. None of the committee members had prior experience with making a documentary film. However, all three were prolific writers and speakers on educational and social inequality in India in English and Hindi. Professor Madhu Prashad provided the background narration. The film merged footage taken during the march of interviews with activists and public meetings as well as other AIFRTE public meetings, posters, pamphlets, and cartoons and headlines from English and regional news media. The film cost approximately Rs. 3 lakh (US$ 5000) to make-an amount which went mainly towards paying the film-makers a nominal fee and the cost of renting a high quality camera for filming. Dissemination of English and Hindi versions of the film began in early 2016 through DVDs, community screenings and the AIFRTE YouTube channel.

What makes the film unique is the effort to represent the full linguistic and cultural diversity of India (Laltu, personal interview, 2016). In addition to including activist speakers from different regions of the country, film-makers also privileged the voices of Dalit and Adivasi members of the coalition. These voices speak through cultural performances featuring a vast repository of protest poetry and music called jangeet. Jangeet represents a powerful media of "critique" because it draws on historical and contemporary oral traditions of storytelling and performance situated in local languages/dialects, and cultural traditions, including humour and satire. 7 Another defining feature of the film is the commitment to foregrounding voices from campus-based student movements that have courageously resisted the renewed assault on progressive university campuses by combined forces of neoliberal and neoconservative political groups that enjoy the protection and support of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Inspired by a diverse group of left-leaning ideologies, these student organisations have redoubled their efforts to resist and transform oppressive caste, class, and gender relationships embedded in higher education institutions as well as across Indian society (see also AICSS/AIFRTE 2017).

The history of Indian mass education narrated in this film and the multiple historical knowledges that shape this narrative tend to be rarely acknowledged in mainstream education and development discourse in India (Kumar 2005). However, this is a history that has inspired and sustained current struggles of Dalits, Adivasis, and poor women, farmers, workers, to name just a few groups that remain systematically excluded from the project of capitalist development. Since its formation, AIFRTE has framed the struggle to protect public education as part of broader struggles to reclaim and expand conceptions of what constitutes the public in Indian political discourse. The diversity within the coalition has contributed to the production of an increasingly complex and in this sense intersectional educational discourse that seeks to interweave Marxist/class analysis with educational visions shaped by Mahatma Gandhi, historical and contemporary Dalit thinkers such as Ambedkar and Periyar, disability activists and so forth (see for example the collection of essays in Kumar 2014). I will now discuss these multiple and historical knowledges as represented in the film.

We Shall Fight, We Shall Win: Documentary and Intersectional Histories of Mass Education

The poem that calls people to action at the beginning of the film and this article is quickly followed by a reminder that free mass education was a reality in colonial India in princely states such as Kashmir (in the north) and Bhopal (in central India). Viewers are presented with a black and white photograph of the five begums, female Muslim rulers of Bhopal who opened schools for girls almost 200 years ago.

Popular Resistance in Medieval India

The narrative continues with a brief recounting of medieval, precolonial religious and cultural movements for social reform that were critical of the modes of domination embedded in the Hindu caste system, which privileged the priestly caste Brahmins and sanctioned the abuse and exploitation of lower castes and those considered entirely outside the caste system. These were the so-called untouchable castes who call themselves Dalits today and the indigenous or First Nations peoples who call themselves Adivasis. Civil rights activist and academic Dr Haragopal traces the roots of scientific and secular education in India to reformist traditions such as Buddhism (2nd century BC) and Bhakti traditions (8th-17th century AD).

A female community organiser from Karnataka, Mallige, talks about the male and female poets of the 12th-century Vachana movement whose poems about the evils of caste and superstition continue to inspire Kannada poets today. The Vachana poets adopted the language of the people-Kannada-to promote an understanding of religious conduct based on values of equality, nonviolence and justice. The speakers do not elaborate on these traditions and a detailed overview is beyond the scope of this article. However, it is important to point out that none of these social reform movements were monocultural or monolithic in nature. For instance, Bhakti poets8 flourished in north, central and south India and Dalit women poets within the 12th-century Vachana movement (located in modern-day Karnataka) had to struggle against gender and caste domination. Relatedly, the development of Buddhist thought was largely restricted to a small region of north India during the lifetime of Gautama Buddha and was subsequently pushed out of the subcontinent (to present day regions of Tibet, Vietnam, China, Korea and so forth) due to sustained persecution from Hindus and Muslims. It is also necessary to emphasise the divergent ways in which these histories were interpreted and deployed in 19th-century politics not only by upper-caste colonial reformers such as Bankim Chandra, but also nationalist leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, founder of the Dalit movement, Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar and Lala Lajpat Rai (see e.g. Guha 1998; Kumar 2005; Wankhede 2008). The debate on education between Gandhi and Ambedkar continues to be a point of fracture for activists on the Indian Left.

What is important in these representations of precolonial histories of resistance here is the depth of historical roots claimed by AIFRTE activists. Although brief, these historical references immediately establish a link to the distant past which also suffered from erasure in the colonial education enterprise. These historical figures have been partially reclaimed in small parts of official school curriculum (mainly vernacular language not history) but remain vibrant in Hindu folk and vernacular histories as iconic spiritual and social reformers. Their poems and songs have survived for centuries and continue to influence contemporary discourses of spirituality, philosophy, literature and other spaces of indigenous knowledge production. In doing so, the film constructs an indigenous or local historical legacy for the contemporary demands for universal education.

Anti-Colonial Struggles

The narrative then moves on to the vision and achievements of 19th-century colonial reformers and freedom fighters. This segment of the narrative features archival film footage of seminal moments in the concluding years of the freedom struggle, including photos of nationalist leaders and scenes from the Satyagraha ("Truth Force") movement led by Mahatma Gandhi.

Dr Haragopal traces the beginning of a social "experiment" to the husband-and-wife couple of Savitribai and Jyotirao Phule who championed education for women and Dalits. In doing so, they challenged Hindu orthodoxy and law as encapsulated in ancient Sanskrit texts known as the Laws of Manu,9 which date back approximately to the 2nd century BC. In so doing, the Phules laid the foundation for the concept of universal education.10 This vision of education for all then became a part of the freedom struggle.

Narrator Madhu Prashad then briefly recounts the emergence and framing of the demand for free and compulsory education for every Indian child which was first voiced by Dadabhai Naoroji. Anti-casteism activist Jyotirao Phule was next to criticise the British for designing an education system only for the rich and the Brahmins.11 In 1921, Gopal Rao Gokhale's bill12 to increase public education funding was defeated at a time when only 11 per cent of the Indian population is known to have been literate.13 She goes on to name the 1919 Jalianwala Bagh massacre14 in Amritsar (Punjab) as a key influence in the radicalisation of the freedom movement. The public outrage that followed emboldened nationalist leaders to call on students to leave colonial institutions of higher education, j oin the freedom struggle and build nationalist institutions. She names Bhagat Singh and his fellow youthful revolutionaries as "legendary icons of this period" whose socialist and secular ideal of equality and rallying cry of Inquilab Jindabad ("Long Live the Revolution") continue to inspire social movements today.

Three additional historical milestones in the development of a vision of universal and free mass education are also named, beginning with the Wardha Conference on Gandhi's proposal for basic education called Nai Talim or the "New Way." This meeting was followed by the 1938 resolution at the Haripura Session of the Congress to build national education on a new foundation. A third moment of historical significance named by the narrator is the call to "Educate, Agitate, Organise" by Dr Ambedkar.15

As British rule drew to an end, the Sargent Commission prepared and submitted a report in 1944 to the Central Advisory Board for Education (CABE). The report recommended that the government of independent India make education free and compulsory so that all children were prepared to be citizens. Subsequently, the Kher committee demanded that this goal of universal education should be realised within 10 years of Independence. In recognition of but not compliance with these demands, the writers of the Indian Constitution included the right to education as a Directive Principle.

This history of the freedom struggle is narrated in a factual manner and focuses on key events and nationalist leaders who also figure prominently in official history. It is assumed that viewers will recognise and understand the significance of names, dates, places and images. The representation of educational debates within the nationalist movement privileges Mahatma Gandhi's thoughts on education. However, educational discourse produced in other AIFRTE sites and spaces (e.g. public speeches, newsletters, publications) recognises multiple visions for education in free India by Ambedkar, Rabindranath Tagore16 and other progressive thinkers of the time (see essays in Kumar 2014; AICSS/AIFRTE 2017).

Bhagat Singh stands out in this part of the historical narrative as the only historical figure whose memory has been preserved in vernacular songs and poems, visual cultures, and popular histories neglected by nationalist academics and official histories (MacLean 2012; MacLean and Elam 2013). Singh was executed at the age of 23 by the British in 1932 for his role in the Lahore Conspiracy Case which centred on the murder of a British police officer in 1928. He joined the nationalist struggle as a teenager and became a compelling and eloquent voice for an independent, socialist India. Notwithstanding his left-leaning though eclectic political ideology, Bhagat Singh is now a polysemic symbol for activism-as a revolutionary nationalist icon who transcends linguistic and political divides of left and right. In this film, his name figures in every utterance by a youth activist and the film ends with a song tribute to Singh entitled with the refrain "You are alive in every drop of our blood" by the Dalit/Ambedkarite Left cultural organisation Kabir Kala Manch.

Betrayal by the State

The next segment about the expansion of mass education in independent India focuses on the ways in which structural adjustment and market reforms have exacerbated educational inequality and exclusion. Madhuri, a female activist affiliated with Adivasi and Dalit movements in Central India, states, "previously we had inequality by land, now it is by education." Then an activist from Kerala provides another reminder of a state which achieved 100 per cent literacy through universal education. He states, "education is the most significant factor to attain human dignity for common people." Kerala has been under the governance of primarily left-leaning coalitions since Independence (including the Communist Party of India).

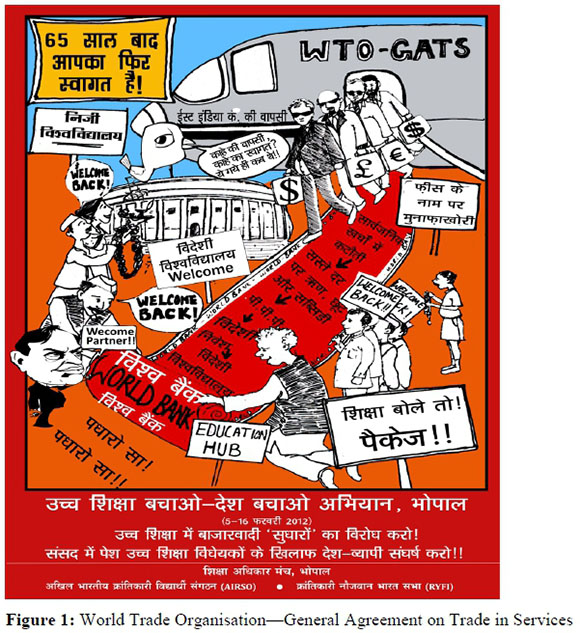

The remainder of this segment is constructed primarily from excerpts from a public address by Dr Anil Sadgopal interspersed with other speakers and images of political posters about the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. The AIFRTE poster in Figure 1 likens the adoption of pro-market policies of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to the recolonisation of India 65 years after achieving independence.

Dr Anil Sadgopal has occupied the role of public intellectual for several decades. He is also a US-educated biochemist, founder of the seminal Hoshangabad Science Teaching Programme,17 former dean of Delhi University, and a founding member of AIFRTE. Over the last six decades, Dr Sadgopal has contributed to several national committees on education policy and contributed to an earlier draft bill for the RTE Act.18

Given his prominent role in the film, I present here a translated and edited transcript of the history narrated by Dr Sadgopal in Hindi, which begins with the DPEP educational reform and culminates in the RTE Act:

For the first time since Independence, the government announced that we [India] are unable to teach every child in school. ... that school is not a place for everyone. A country whose Constitution ... Clause 1 Article 15 states that the state shall not discriminate in any way between citizens. With liberalisation of the economy ... our country's doors were opened once again for unregulated plunder and exploitation by corporate capital. When the government spread out its hands before the World Bank for a loan. The Indian government was told that loans would depend on expenses being reduced. The government said we can only cut expenses gradually. We have eight to 10 lakh schools-how can we do it quickly? The WB said we will show you how to bring expenditure down quickly. This strategy was called the DPEP. As soon as it started, the question was raised that our education policy approved by Parliament required every school to have at least three rooms and three teachers. The WB asked if it was necessary to have three rooms and three teachers for a school with five classes. Could we not manage with two rooms and two teachers? After one or two years the WB asked why can't you do with one room and one teacher? Our leaders said-we don't get it-how can one teacher teach five classes at the same time? The WB said we will show you this miracle. The miracle was called multi-grade teaching. This has happened in Gujarat and 18 other states. Hundreds of millions of teachers have been spent to train teachers how to do this. But this is not free-it is all a loan that you and your children will pay.

This dramatised retelling of the negotiations between the Indian government and the WB is replete with sarcasm and ironic humour. One of the focal points is the Indian Constitution which is used throughout the film to link the past and the present, to remind viewers of the dream of an India free from British rule as well as social discrimination. The dominant message is that of betrayal of the Indian Constitution and people by the state. This telling highlights the World Bank's ideological commitment to undermining the public sector by slashing public expenditure on education, health and other social sectors, etc. It paints a powerful picture of the adverse impact of efficiency-driven education policies on conditions for teaching and learning in government schools. It also reminds viewers that the Bank is a financial not a philanthropic institution, which means that all "assistance" comes in the form of a loan or public debt (see also Sadgopal 2003).

Other speakers emphasise the World Bank's role in undermining the democratic and public spirit of the freedom struggle and the Constitution in contravention of democratic policymaking. One of the most powerful testimonies comes from Nasribai, an Adivasi activist and mother from the impoverished, central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh:

We have no facilities of health and education at our homes. We do not have money. The government does not care . they are just selling health and education. We have schools but they do not have teachers. When teachers come, they only come for one hour. Children do not get midday meals. They do not have exams from class one to class eight. They just roam around the jungle. The government is snatching our right to water-forest-land. They build dams on our lands but there is no compensation. They produce electricity from the dams. But we do not get it.

Nasribai provides a history from below by speaking to the cost of the dominant project of development and education from the vantage point of indigenous peoples. Her testimony documents a virtually uninterrupted history of exploitation-of her people as well as traditional lands. The scars of the profit-driven developmentalist project of the Indian nation-state are engraved most visibly on the bodies and lives of the Adivasi people.

Privatised Rights

The narrative then moves to the historical judgement by the Supreme Court of India which held that the right to education was a judicially enforceable right, and set in motion the formal political process to develop a national law to guarantee and implement this right (see e.g. Combat Law 2009; Kumar 2006). This process would take another 17 years and deliver the RTE Act-an undemocratic and diluted legislation which limited education rights to children aged 6 to 14 years.

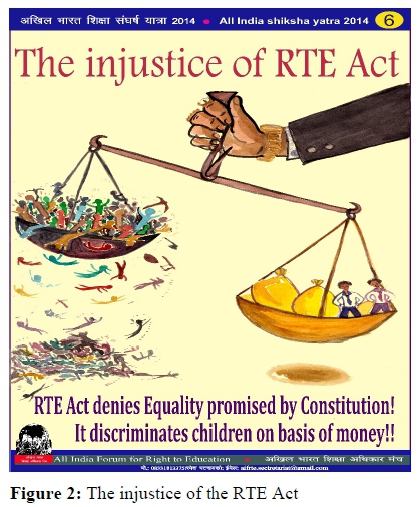

At this point, the previously discussed AIFRTE critique of the RTE Act is communicated mainly through visuals including posters and AIFRTE publications about the RTE Act. The poster in Figure 2 entitled "The injustice of the RTE Act" uses the metaphor of an unbalanced weighing scale to convey the multiple forms of inequality exacerbated by the RTE Act. The text at the bottom states "RTE denies equality promised by Constitution! It discriminates children on basis of money." The poster highlights the fact that the Act contravenes the Constitutional obligation placed on the government to provide universal and free education and further exacerbates educational inequality in a deeply stratified society. The failure to improve public education ensures that families must purchase schooling for their children, if they are able to do so.

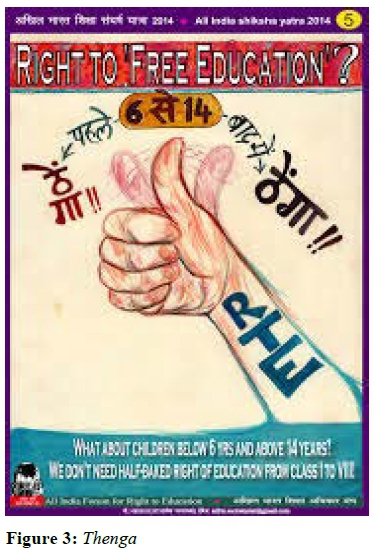

Another poster (see Figure 3) is captioned with the question, "Right to 'Free Education?'". The visual consists of a hand arranged in a thumbs-up gesture where the thumb is being shaken from side to side. One of the meanings of this gesture-referred to as thenga in Hindi-is negating or negative. It is customarily used by children to tease and provoke their playmates by communicating messages such as "you have nothing," "you have lost," "you can't catch me," and so forth. This gesture may also be interpreted as a marker of an illiterate person who is unable to write their name and therefore must use a thumb stamp instead. Text around the upraised thumb from left to right reads as follows: "thenga," "before," "6 to 14 (years)," "after," "thenga." The text at the bottom of the poster reads as follows: "What about children below 6 year and above 14 years? We don't need half-baked right to education from Class 1 to 8."

The message conveyed by this poster is that the RTE Act does not comply with the idea of the right to education because it excludes preschool and secondary education. Without free and universal access to both these levels of education, the legislation will not remedy the entrenched inequality that characterises Indian education.

Learning from History

Woven into this chronological historical narrative are three crosscutting themes: the failure of private education for the poor, the pervasive absence of meaningful and culturally responsive education, and the communalisation of education.

First, the film argues that low-fee English-medium private schools have excluded and failed the poor. The film highlights the choiceless choice faced by poor and working-class parents who know that English continues to function as the language of access and opportunity in postcolonial India.19 While the majority remain excluded from educational opportunity altogether, a few manage to purchase private schooling-but only for the child who is deemed to show academic promise. However, after almost a decade of the experiment, budget or low-cost schools for the poor have failed to deliver on their promises of quality education and social mobility (see e.g. Srivastava and Noronha 2014). The film includes a satirical skit performed in Hindi by teenage Adivasi school boys from Madhya Pradesh which aims to explode the myth that private schools are better than public schools. The skit challenges the pervasive belief that English-language instruction is necessary to secure further educational and economic opportunity. Instead, the skit captures the reality of most English-medium private schools for the poor where teaching consists entirely of rote learning and strict discipline, and success or failure is attributed to individual students and their families. Most of these students do not have access to any other educational resources, unlike their wealthier peers in elite private schools.

Next, activists highlight the pervasive absence of meaningful and relevant education-across the public and private sector. Lokesh, a male activist, states that the current education system does not "develop critical faculties," which ensures that "the young should remain unaware of the faults of the [social] system." Another example is drawn from the state-facilitated expansion of high-fee-charging private higher education-mainly in the areas of business management, medicine and engineering, which has only increased opportunities for profit for education entrepreneurs. Dr Haragopal eloquently states the case:

Those who study medicine in a private college instead of turning out a good doctor will turn out as a businessman. It's basically an investment and you want returns. That kind of education does more harm to even the rich and the affluent than the poor people. Therefore, to humanise and socialise the individual-one has to have education in the public domain.

Mandeep Singh, a male student activist from Punjab, provides the most eloquent testimony to the real crisis in higher education. He talks about the high rates of unemployment, suicide and drug abuse amongst affluent, Punjabi college-educated youth. He says, "instead of providing inspiration, education is making youth restless and directionless ... they cannot see a future for themselves."

Last but not least, the film highlights the deep linkages between neoliberal and neoconservative forces. Historian Zoya Hasan (2016) has underlined the ways in which Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP have moved India's political discourse towards individual responsibilities and away from rights and entitlements.

The film highlights the nexus between neoliberal and neoconservative education reformers which has strengthened initiatives to "saffronise" or "communalise" Indian education by the ruling right-wing, Hindu fundamentalist party-the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). In the Indian context, the terms "saffronisation" and "communalisation" are used to refer to organised political efforts to transform secular India into a nation governed by Hindutva ideology based on essentialised conceptions of precolonial Hindu society. Academic Madhu Prasad describes the Hindutva project for education as follows:

What they mean by Indianising education is to introduce a process of Sanskritisation which lionises upper caste thinking-and to develop the idea that all other religions that are part of the history of this subcontinent are somehow foreign and not part of our ... national life.

Laltu, another academic, reminds viewers of the systematic infiltration of right-wing cadre into higher education and their efforts to reframe history, science, social relations, and the relationship between human beings and nature. This has also been achieved through the rewriting of school and higher education curricula, curtailing academic freedom, and film censorship regulations-all designed to foreground patriarchal, upper-caste and upper-class Hindu worldviews and values (see e.g. Bénéï 2008; Chopra and Jeffery 2005; Manjrekar 2012; Nambissan and Rao 2013). This part of the narration is supplemented with visuals including posters, news headlines, and cartoons that are critical of Hindutva and its proponents.

Discussion

Knowledge struggles are intrinsic to struggles against colonialism, neoliberalism and other forms of structural oppression that privilege particular ways of knowing over others-for instance hegemonic discourses of Western conceptions of objectivity, rationality, science, and so forth (de Sousa Santos, Nunes, and Meneses 2007). Even where historical barriers to access and participation are removed, groups that do not communicate through these dominant rationalities continue to experience silencing and misrepresentation (Mohanty 2003). In India certainly, the social revolution did not keep pace with the anti-colonial struggle and historical hierarchies around caste, class, gender and religion endure (Omvedt 1971).

Some strands of social movement scholarship have underlined the important role played by critical historians in building oppositional identities, strategic repertoires and resilience to mobilise and sustain subaltern struggles. Choudry and Vally (2018, x) write that "radical histories can disrupt inevitabilities, excavate lost alternatives and widen the horizons of empathy." Activist history telling is intrinsic to the process of transforming the "personal subject" into the "historical subject" because the work of constructing and reconstructing history is essentially the work of remaking the social relations and cultural practices that shape identity and agency (Touraine 1988). Thus, the work of constructing activist histories is intrinsically concerned with changing identities and subjectivities in relation to perceptions of past and present realities. This scholarship also recognises multiple forms of historical knowledge that are present in sites of collective struggle, including oral, written, academic, popular, folk and vernacular (Chatterjee 2012; Deshpande 2017), as well as the role of the arts in constructing and communicating these diverse forms of activist knowledge (Choudry 2015).

Subaltern social movements in India have long worked to reappropriate silenced and subjugated histories to create new meanings, symbols and languages to interrogate structures of domination and contribute to material, political and cultural transformations (see e.g. Kapoor 2013; Nilsen and Roy 2015; Scandrett, Mukherjee, and the Bhopal Research Team 2011). This article has explored history-retelling by Indian education activists to challenge dominant economic, cultural and political discourses that normalise and legitimise a deeply segregated and unequal education system. More specifically, the film sets out to recentre educational discourse around an expansive notion of the public by disrupting dominant discourse about the superiority and inevitability of privatised education.

The film presents a critical analysis of the historical modes and systems of domination that have worked to undermine universal and free public education in India and created conditions for the privatisation and commercialisation of a fundamental human right. It also presents what might be viewed as an intersectional history that seeks to connect educational injustices to other historical and systemic forms of oppression configured around the privatisation and commodification of natural resources-hence the slogan shikhsha-jal-jangal-zameen ("education-water-forest-land").

This critique is constructed through excavating sidelined and silenced discourses of popular resistance which were integral to the establishment of an independent, democratic and secular India. The foregrounding of subjugated voices and lived experiences contributes to complex understandings not only about the nature of structural educational inequality but also about the kinds of systemic and cultural transformations required to remedy these inequalities. It also encourages us to understand activist narratives about history as cultural work, intrinsically connected to forgetting, remembering and retelling-to constructing counter-histories which trouble ahistorical and depoliticised claims to individual and social progress. I have shown how this is accomplished in the film by weaving together different kinds of historical knowledge and histories from multiple vantage points-oral and written, histories of great men and great events, histories of subaltern struggles and everyday resistance, academic as well as folk and popular history.

Relatedly, this analysis has highlighted the artistic (visual, musical, performance) vocabulary of activists and the significance of cultural work in sites of collective struggle. The diversity of political art and cultural performances underlines the ways in which artwork, words and music that emerge from people's struggles help to tell the stories of the struggle, affirm experiences and inspire people to stay strong (Choudry 2015). Thus, this film demonstrates how activists- as cultural workers (historians, artists, educators)-can be transmitters of ideas across space and time (Choudry 2015; Freire 1998).

The historical retelling in this film stands in stark contrast to what Aziz Choudry (2015, 78) refers to as the "fantasy histories" produced by nongovernmental and entrepreneurial social welfare organisations that legitimise compartmentalised, "single-issue" interventions for education. These fantasy histories are power-blind histories that mask hierarchies of knowledge and social privilege-because they restrict understandings and enactments of agency and participation to the marketplace. This kind of selective and ahistorical knowledge production has been a defining feature of capitalism and continues to remain essential to both projects of neoliberalism and neoconservatism.

In contrast, this historical retelling by AIFRTE is intended to mobilise people for struggle and maintain resilience in the struggle. The film was made to support ongoing AIFRTE initiatives for popular education and movement-building, which till now have largely been restricted to print media (see AIFRTE website) and public lectures. Although the film focuses on messages of critique (of educational privatisation) and collective struggle to protect public education, AIFRTE discourse as a whole also engages with the question of how we can reimagine education for an egalitarian, secular and democratic India. Not only does the film valorise bottom-up historical narratives that support the democratisation of education-it makes the case for the right to do so through precolonial and anti-colonial histories of resistance, not through the international human rights framework.

In all of these ways, the film provides situated insights into activist knowledge production within this particular site of collective struggle (Cox and Fominaya 2009; Foley 1999). It exemplifies the ways in which activist knowledge production-in this case historical-is place-based and situated in lived realities of oppression, inequality and exclusion (Choudry 2015; Choudry and Kapoor 2010).

At the same time, this analysis views activist knowledge construction as inherently political and embedded within hierarchies of power produced by sociohistorical locations, identities, and subjectivities (Freire 1970; Kane 2001; Walter and Manicom 1996). The ways in which activists reclaim and reconstruct history are always mediated by cultural context; any claims about the power of counter-story telling must be contextualised rather than naturalised as inherently subversive (Polletta 1998; 2006). The goal of this film is to provide an alternative narrative for Indian education and build support for the struggle for public education. Towards this goal, the film presents a unified or unifying narrative and does not engage with ongoing debates and contestations within the movement. However, AIFRTE discourse beyond this film consciously strives to dialogue with and be responsive to the cultural and ideological diversity which characterises the Indian Left. In this regard, it can be noted that the coalition has stronger relationships with Dalit groups than with Adivasi groups.

Conclusion

Ravi Kumar (2006, 31) writes, "the transplantation of welfare state principles in a neoliberal state is an impossibility, but, then, that does not mean that we stop fighting for the spaces that develop criticality." He goes on to argue that what is needed is a larger political perspective- one that is powerful enough to compel the Indian state to halt rather than promote the limitless expansion of private capital.

In the absence of histories that document radical struggles "from below," it becomes possible to make ahistorical assertions about the extent to which we have progressed towards societies based on rights, social justice and sustainability. The historical discourses in this film speak back to a cultural and political milieu increasingly characterised by a politics of narrow self-interest, greed and hate.

The historical narrative presented in the film shows that neoliberal globalisation is neither new nor inevitable but a systematic process of domination protected and imposed by a transnational network of economic and political elites, including international financial institutions such as the World Bank and multinational corporations such as the Birlas and Ambanis. More significantly, by linking the past and the present in so many ways, the film documents that popular resistance to colonialism and capitalism has not ended (Choudry 2015).

In We Shall Fight We Shall Win, education activists issue a call for collective action at a time when social wellbeing has been sacrificed in the Indian development project in the interests of local propertied interests and global capital. The struggle for public education is not only a struggle against class, caste and gender inequality, but a struggle for the creation of a different social imagination, where individual self-interest and group loyalty are replaced by collective wellbeing, and where the commercial benefits of the private are replaced by an intrinsic value for the public.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank comrade Lokesh Malti Prakash and the reviewers for reading and providing feedback on multiple drafts of the manuscript. This research was funded by the Faculty of Education and Arts, University of Newcastle, Australia.

References

AICSS (All India Convention of Students Struggles) and AIFRTE (All India Forum for the Right to Education). 2017. Student Movements in India: Stories of Resistance from Indian Campuses. Bengaluru: AIFRTE. [ Links ]

AIFRTE (All India Forum for the Right to Education). 2010. Neoliberal Assault on Higher Education: An Agenda for Putting India on Sale. Bengaluru: AIFRTE. [ Links ]

AIFRTE (All India Forum for the Right to Education). 2012. Chennai Declaration. Accessed July 12, 2018. http://aifrte.in/chennai-declaration.

Balagopalan, S. 2003. "Understanding Educational Innovation in India: The Case of Eklavya: Interviews with Staff and Teachers." Contemporary Education Dialogue 1 (1): 97-121. https://doi.org/10.1177/097318490300100105. [ Links ]

Balagopalan, S. 2014. Inhabiting "Childhood": Children, Labour and Schooling in Postcolonial India. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Bénéï, V. 2008. Schooling Passions. Nation, History, and Language in Contemporary Western India. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Batra, P. 2012. "Positioning Teachers in the Emerging Education Landscape of Contemporary India." In India Infrastructure Report 2012: Private Sector in Education, 219-231. IDFC Foundation. New Delhi: Routledge. Accessed July 13, 2018. http://www.idfc com/pdf/report/IIR-2012.pdf. [ Links ]

Chatterjee, P. 2012. "After Subaltern Studies." Economic and Political Weekly 47 (35): 44-9. Accessed July 12, 2018. http://www.epw.in.ezproxy.newcastle.edu.au/journal/2012/35/perspectives/after-subaltern-studies.html. [ Links ]

Chopra, R., and P. Jeffery, eds. 2005. Educational Regimes in Contemporary India. New Delhi: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Choudry, A. 2015. Learning Activism: The Intellectual Life of Contemporary Social Movements. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Choudry, A., and D. Kapoor. 2010. Learning from the Ground Up: Global Perspectives on Social Movements and Knowledge Production. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230112650. [ Links ]

Choudry, A., and S. Vally, eds. 2018. Reflections on Knowledge, Learning and Social Movements: History's Schools. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Combat Law. 2009. Right to Education Bill: Special Issue. Combat Law: The Human Rights and Law Bimonthly 8 (3 and 4): 1-84. [ Links ]

Cox, L., and C. F. Fominaya. 2009. "Movement Knowledge: What Do We Know, How Do We Create Knowledge, and What Do We Do With It?" Interface: A Journal for and about Social Movements 1 (1): 1-20. [ Links ]

Deshpande, A. 2017. "Past, Present and Oral History." Economic and Political Weekly 52 (29): 3843. [ Links ]

de Sousa Santos, B., J. A. Nunes, and M. P. Meneses. 2007. "Opening up the Canon of Knowledge and Recognition of Difference." In Another Knowledge Is Possible: Beyond Northern Epistemologies, edited by B. de Sousa Santos, 10-62. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Dhuru, S. 2014. "Education as a Human Right: From Philosophy to Practice." Unpublished paper.

Fernandes, L. 2006. India's New Middle Class: Democratic Politics in an Era of Economic Reform. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 1998. Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to Those Who Dare Teach. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Foley, G. 1999. Learning in Social Action: A Contribution to Understanding Informal Education. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Guha, R. 1998. Dominance without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India. Delhi: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Hasan, Z. 2016. "Democracy and Growing Inequalities in India." Social Change 46 (2): 290-301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049085716635432. [ Links ]

Kapoor, D. 2013. "Anticolonial Subaltern Social Movement (SSM) Learning and Development Dispossession in India." In Learning with Adults: International Issues in Adult Education, edited by P. Mayo, 131-50. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-335-5_10. [ Links ]

Kamat, S., C. A. Spreen, and I. Jonnalagadda. 2016. Profiting from the Poor: The Emergence of Multinational Edu-Businesses in Hyderabad, India. A report for Education International. Accessed December 28, 2017. https://download.ei-ie.org/Docs/WebDepot/ei-ie_edu_privatisation_final_corrected.pdf.

Kane, L. 2001. Popular Education and Social Change in Latin America. Nottingham: Russell Press. [ Links ]

Kumar, K. 2005. Political Agenda of Education: A Study of Colonialist and Nationalist Ideas. 2nd ed. New Delhi: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Kumar, K. 1992. What Is Worth Teaching? New Delhi: Orient Longman. [ Links ]

Kumar, K, M. Priyam, and S. Saxena. 2001. "Looking beyond the Smokescreen: DPEP and Primary Education in India." Economic and Political Weekly 37 (7): 560-68. [ Links ]

Kumar, R. 2006. "When Gandhi's Talisman No Longer Guides Policy Considerations: Market, Deprivation and Education in the Age of Globalisation." Social Change 36 (3): 1-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/004908570603600301. [ Links ]

Kumar, R., ed. 2014. Education, State, and Market: Anatomy of Neoliberal Impact. New Delhi: Aakar Publications. [ Links ]

Laltu, H. S. 2014. "The Language Question: The Battle to Take Back the Imagination." In Education, State, and Market: Anatomy of Neoliberal Impact, edited by R. Kumar, 139-61 New Delhi: Aakar Publications. [ Links ]

MacLean, K. 2012. 'The History of a Legend: Accounting for Popular Histories of Revolutionary Nationalisms in India." Modern Asian Studies 46 (6): 1540-571. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X12000042. [ Links ]

MacLean, K., and J. D. Elam. 2013. "Reading Revolutionaries: Texts, Acts and Afterlives of Political Action in Late Colonial South Asia." Postcolonial Studies 16 (2): 113-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2013.823259. [ Links ]

Majumdar, M. 2012. "The Shadow School System and New Class Divisions in India." TRG Poverty and Education Working Paper Series. Max Weber Stiftung.

Manjrekar, N. 2011. "Ideals of Hindu Girlhood: Reading Vidya Bharati's Balika Shikshan." Childhood 18 (3): 350-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568211406454. [ Links ]

Matin, A., F. Siddiqui, K. M. Ziyauddin, A. N. Rao, M. A. Khan, P. H. Mohammad, and S. A. Thaha., eds. 2013. Muslims of India: Exclusionary Processes and Inclusionary Measures. New Delhi: Manak Publications. [ Links ]

Mohanty, C. T. 2003. Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822384649. [ Links ]

Morrow, V. 2013. "Whose Values? Young People's Aspirations and Experiences of Schooling in Andhra Pradesh, India." Children and Society 27 (4): 258-69. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12036. [ Links ]

Nambissan, G. B. 2010. "The Indian Middle Classes and Educational Advantage: Family Strategies and Practices." In The Routledge International Handbook of the Sociology of Education, edited by M. Apple, S. Ball and L. A. Gandin, 285-95. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Nambissan, G. B., and S. J. Ball. 2010. "Advocacy Networks, Choice and Private Schooling of the Poor in India." Global Networks: A Journal of Transnational Affairs 10 (3): 324-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2010.00291.x. [ Links ]

Nambissan, G. B., and S. Rao, eds. 2013. Sociology of Education in India: Changing Contours and Emerging Concerns. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Nilsen, A. G., and S. Roy, eds. 2015. New Subaltern Politics: Reconceptualizing Hegemony and Resistance in Contemporary India. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199457557.001.0001. [ Links ]

Omvedt, G. 1971. "Jotirao Phule and the Ideology of Social Revolution in India." Economic and Political Weekly 6 (37): 1969-79. Accessed July 12, 2018. http://www.epw.in/journal/1971/37/special-articles/jotirao-phule-and-ideology-social-revolution-india.html. [ Links ]

Patwardhan, A., dir. 2011. Jai Bhim Comrade. Motion film. India.

Polletta, F. 1998. "Contending Stories: Narrative in Social Movements." Qualitative Sociology 21 (4): 419-46. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023332410633. [ Links ]

Polletta, F. 2006. It Was Like a Fever: Storytelling in Protest and Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226673776.001.0001. [ Links ]

PROBE Team and Centre for Development Economics. 1999. A Report on Elementary Education in India. Oxford University Press: New Delhi.

PROBE Team. 2006. PROBE Revisited: A Report on Elementary Education in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rao, P. V. 2013. "'Promiscuous Crowd of English Smatterers': The 'Poor' in the Colonial and Nationalist Discourse on Education in India, 1835-1912." Contemporary Education Dialogue 10 (2): 223-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973184913485013. [ Links ]

Sadgopal, A. 2003. "Education for Too Few." Frontline 20 (24). Accessed July 17, 2018. https://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2024/stories/20031205002890700.htm. [ Links ]

Saxena, S. 2012. "Is Equality an Outdated Concern in Education?" Economic and Political Weekly 47 (49): 61-8. [ Links ]

Scandrett, E., S. Mukherjee, and the Bhopal Research Team. 2011. "'We Are Flames Not Flowers': A Gendered Reading of the Social Movement for Justice in Bhopal." Interface: A Journal for and about Social Movements 3 (2): 100-22. [ Links ]

Srivastava, P., and C. Noronha. 2014. "Institutional Framing of Right to Education Act: Contestation, Controversies, and Concessions." Economic and Political Weekly 49 (18): 51-8. [ Links ]

Teltumbde, A. 2014. Education for Dalits or the Return of Manu. Hyderabad: AIFRTE. [ Links ]

Thapliyal, N. 2012. "Unacknowledged Rights and Unmet Obligations: An Analysis of the 2009 Indian Right to Education Act." Asia-Pacific Journal of Human Rights and the Law 13 (1): 65-90. https://doi.org/10.1163/138819012X13323234709820. [ Links ]

Thapliyal, N. 2014. "The Struggle for Public Education: Activist Narratives from India." Postcolonial Directions in Education 3 (1): 122-59. Accessed July 12, 2018. http://www.um.edu.mt/pde/index.php/pde1/index. [ Links ]

Thapliyal, N. 2016. "Privatized Rights, Segregated Childhoods: A Critical Analysis of Neoliberal Education Policy in India." In Politics, Citizenship and Rights, edited by K. P. Kallio, S. Mills and T. Skelton, 21-37. Geographies of Children and Young People, Vol 7. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4585-57-6_14. [ Links ]

Touraine, A. 1988. Return of the Actor: Social Theory in Postindustrial Society. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Vivanki, V. 2014. "Teach for India and Education Reform: Some Preliminary Reflections." Contemporary Education Dialogue 11 (1): 137-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973184913509759. [ Links ]

Wankhede, H. S. 2008. "The Political and the Social in the Dalit Movement Today." Economic and Political Weekly 43 (6): 49-57. [ Links ]

1 Saxena's (1927-1983) poem is recited at the beginning of the film. He was a Hindi-language poet, writer, playwright and political satirist.

2 This group includes high-cost, for-profit institutions as well as relatively lower cost, not-for-profit private institutions, many of which were established by colonial missionaries in urban and semi-urban areas.

3 See e.g. Rao (2014) on colonial schools that provided access to Dalit/untouchable families.

4 After the pilot project, DPEP was renamed SSA (Education for All) and "scaled up" to the entire country. Despite research that demonstrates a wide variation in education quality and outcomes, the Indian government continues to borrow money from the World Bank (in exchange for structural adjustment conditionalities) to pay for SSA. The programme also receives funds from other international development agencies and a two per cent cess (tax).

5 A current and complete list of member organisations is available on the AIFRTE website and at the end of the film. See www.aifrte.com.in.

6 These include expansion of public provision of quality basic education for early childhood and secondary education, significant and progressive increase in spending on public education, and opposition to the privatisation of education (AIFRTE 2012).

7 Indian documentary film-maker Anand Patwardhan (2011) has paid particular attention to the diverse forms of art that emerge from popular movements in India; see e.g. Jai Bhim Comrade.

8 Bhakti movements refer to religious traditions that emphasised loving devotion to the worshipper's god or goddess regardless of gender and caste. In contrast to Hindu orthodoxy, Bhakti poets argued that personal devotion and faith mattered more than priestly instruction or social status.

9 These texts justified Brahmin-dominated hierarchies of caste and gender but were actually only codified into law during British colonial rule.

10 They viewed the building blocks of Western science-objectivity, rationality, empirical knowledge-as powerful allies in their struggle against Brahminical control over access to and production of knowledge.

11 Phule presented his charter of demands at the 1882 Hunter Commission where he chided the British for using resources generated from the labour of the underprivileged to subsidise education of the privileged castes.

12 Gokhale tabled his Elementary Education Bill at the 1911 Imperial Assembly and argued for adequate allocation of public funding to education, particularly elementary education. The Bill was rejected by the Assembly which was dominated by the previously discussed Indian landed elite. He famously pointed out that compared to the American government that spent 16 shillings per head, the Swiss which spent nearly 14, the Australian which spent over 11, and the English government which spent 10, the British government of India spent only one penny per head for primary education (Dhuru 2014).

13 Uncited statistic.

14 A British police officer, Colonel Reginald Dyer, ordered his troops to fire machine guns into a crowd of unarmed men, women and children who had defied the imposition of martial law to celebrate the spring festival and protest against the arrest and deportation of two nationalist leaders. According to different reports, between 400 and a 1000 people died in the firing.

15 His call "Educate Organise Agitate" was also used to launch the English-language AIFRTE newsletter "Rethinking Education" in December 2011. At the same time, the editorial (p. 2) emphasised the "need to transcend Ambedkar" and struggle to "reclaim knowledge, reconstruct education" in order to make it a truly liberatory force.

16 Tagore envisioned an education for decolonisation premised on educational practice that valued indigenous knowledge and work done by ordinary people.

17 A three decades-long school-level innovation which transformed science education for 1000 government schools in 15 districts of one of India's poorest states-Madhya Pradesh (see e.g. Balagopalan 2003).

18 He was also a key participant in the Independent People's Tribunal on the World Bank's adverse influence on education reform in India-for analysis see www.worldbanktribunal.org.

19 One of the AIFRTE's goals is to reinstate instruction in vernacular languages or the mother tongue in the earliest stages of education to facilitate authentic learning and protect cultural diversity. For a nuanced discussion on AIFRTE perspectives on the "language question," particularly in relation to multilingual education and demands by some Dalit groups to be taught English as the language of power, see Laltu (2014) and Teltumbde (2014).