Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.22 n.1 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/2146

ARTICLES

Mapping social justice perspectives and their relationship with curricular and schools' evaluation practices: Looking at scientific publications

Marta SampaioI; Carlinda LeiteII

ICentre for Research and Intervention in Education (CIIE), University of Porto, Portugal. msampaio@fpce.up.pt. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6848-377X

IICentre for Research and Intervention in Education (CIIE), University of Porto, Portugal. carlinda@fpce.up.pt. http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9960-2519

ABSTRACT

The main aim of this article is to give an overview of how the concept of social justice- as linked to curricular and evaluation practices-has been developed in scientific publications over the years. To achieve this goal, a mapping study was carried out by collecting scientific publications from the Web of Science Core Collection. The analysis focused on 217 articles from 50 scientific journals. Each one of the 217 articles was analysed through the process of content analysis. From this analysis, it was possible to conclude that the concept of social justice has been developed, in the main, from a broad view of equity in which inclusion and democracy are central. However, the political agenda, externally imposed and guided by accountability and effectiveness processes, frames all actions relating to social justice issues especially in schools. Accountability and effectiveness processes shape the way that social justice is perceived by policymakers and, consequently, how the processes to achieve them are considered and implemented.

Keywords: curriculum; equity; school evaluation; school improvement; social justice

Introduction

The achievement of social justice is essential for building a more democratic, fair and successful school (Apple 2013; Apple and Beane 1995; Leite 2002). The concept of social justice points to inclusive education and embraces a broad view of equity, opportunity and democratic issues (Ball in Mainardes and Marcondes 2009). For Vincent (2003), the concept provides a space for dialogue in which different areas of interest (e.g. education, sexuality, sociology, etc.) can be brought together, offering teachers and students a common space for research and critical reflection.

In this sense, if schools are to play a fundamental role in building an ideal of social justice, it is necessary to take into account different students' experiences (Apple, Ball, and Gandin 2013 ; Apple and Beane 1995; Connell 2012) when thinking about curriculum development. Similarly, for education to be able to respond to the diversity that exists among the school population, it is necessary to find different educational answers that view students and teachers as "co-responsible for a broader socio-political intervention project to build a more humane, fair and democratic world" (Santomé 2013, 9). Rawls (2003) and Connell (2012) have both suggested that the curriculum is a historical construction, framed by the most radical debate about social justice and the strategy or strategies to achieve it. Therefore, it can be accepted that the curriculum precedes understanding social justice and as per the authors' perspectives, a curriculum should be counter-hegemonic1 in order to contemplate the interests of the less favoured and achieve equity. According to Dubet (2004), the justice, integration and equity that schools ought to provide do not really exist, because societies have become more disaggregated as a result especially of capitalism and accountability issues. According to this author, equity, as well as equality, is just a necessary fiction and, at the same time, as defended by Zizek (1989; 1994), an ideological mode of function promoting false ideas to be maintained at any price. Dominant systems, such as capitalism, are constantly changing something and implementing new policies and reforms so that nothing really changes (Zizek 1991). In other words, it is a fiction because it is unlikely to be fully implemented, but it is not possible to educate without believing in it (Dubet 2004).

Nonetheless, if schools have a fundamental role in building an ideal of social justice, some authors believe that self-evaluation processes could be a way for them to extend their autonomy and make curricular decisions that are better able to respond to the problems and needs of school populations (Leite and Fernandes 2010, 59). Schools' evaluation practices can be a way to better understand how their actions can lead to the implementation of social justice. Several authors (Greene 2005; House 1990; MacDonald 1976) argue that evaluation practices are a mechanism to engage in school diversity and equity. By giving schools articulate and rich data, evaluation practices can stimulate the development and awareness of the importance of social justice actions in schools and, at the same time, increase the knowledge of the decision-makers and experts serving the interests of the schools' actors.

Taking these ideas into account, the main aim of this article is to give an overview of how the concept of social justice-as linked to curricular and school evaluation practices-has been developed in scientific publications. For this purpose, a mapping study was conducted. According to Kitchenham, Budgen, and Brereton (2010), mapping studies can be used to identify discussions taking place in the literature about a certain issue. In other words, they can be used to identify, evaluate and interpret the research available about a particular subject (Kitchenham, Budgen, and Brereton 2010). Mapping studies are based on the notion that published articles represent not only the findings themselves but also the activity related to those findings, at the same time indicating where the research took place and in what journal it was published (Cooper 2016). Systematic mapping studies are similar to systematic reviews, except that the former consider different inclusion criteria and are intended to map out topics and trends rather than synthesise study results, thereby providing a categorical structure for classifying published research reports and results (Dicheva et al. 2015). For Petersen, Vakkalanka and Kuzniarz (2015), a systematic mapping study is a secondary study that reviews articles about a specific research topic, with the main aim of giving an overview of a research area through classification and counting contributions relating to the categories of that classification. For these reasons, the study was conducted using a systematic mapping design.

The main goals of this systematic mapping study can be summarised in one research question: How is the concept of social justice in scientific publications related to curricular and school evaluation practices? To answer this question, the article follows a structure in which first the methodological procedures are described, namely, the different phases of the mapping study. Then, the main findings of the study are presented and discussed, as are some specificities about the study. Finally, the conclusions contain reflections on the findings and the answer to the research question above.

Methodological Procedures

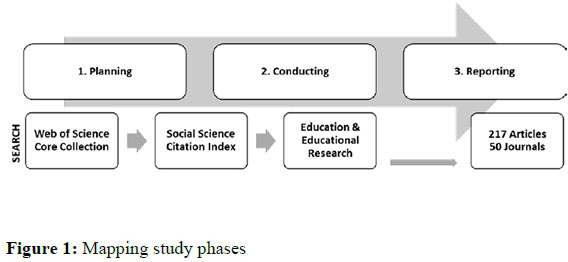

In accordance with recommendations by Petersen et al. (2008) and Elberzhager, Münchb, and Nha (2012) on conducting mapping studies, the study was carried out over three phases, namely planning, conducting and reporting. In the planning phase, a mapping protocol was drawn up that specified the following: the research questions, in order to define the review scope; the database, i.e. where the search for the articles would be carried out; the search string that was to be applied in order to check the aim of the articles; and the inclusion and exclusion criteria (derived from the research question). In the conducting phase, all activities were performed according to the mapping protocol design, including searching, screening and extracting data from the articles. Finally, in the reporting phase, using the findings of the systematic mapping study the research question was answered. Figure 1 shows the different phases of this process.

In order to achieve the research objectives, in the planning phase the study focused on articles published in the Web of Science Core Collection. This database consists of nine indexes containing information gathered from thousands of scholarly journals, books, book series, reports, conferences, etc. It covers over 12,000 highly acclaimed impact journals in full, from all over the world.2 Within this core collection, the Social Science Citation Index was chosen because it is a multidisciplinary index for the journal literature of the social sciences. It covers over 2,900 journals across 50 social science disciplines. It also indexes individually selected, relevant items from over 3,500 of the world's leading scientific and technical journals.3 Within the Social Science Citation Index, a search was then made of the category "Education and Educational Research"4 because, within the 57 categories inside this index, it was considered the one best suited as it was the most focused on the aims of the study. This category contains 233 acclaimed, high-impact scientific journals. After reading the aim and scope of each one and completing the first phase by searching for "social justice" as a keyword, 183 j ournals were excluded, leaving a total of 50.

At this point, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. The criteria for inclusion included: (1) all articles focusing on social justice issues in the educational field; (2) all articles related to the study's research interests, namely, curriculum, evaluation, equity and inclusion; and (3) articles published in any year. The exclusion criteria included: (1) all book reviews, reports and conference papers; and (2) papers with restricted access or which had to be paid for in order to be read.

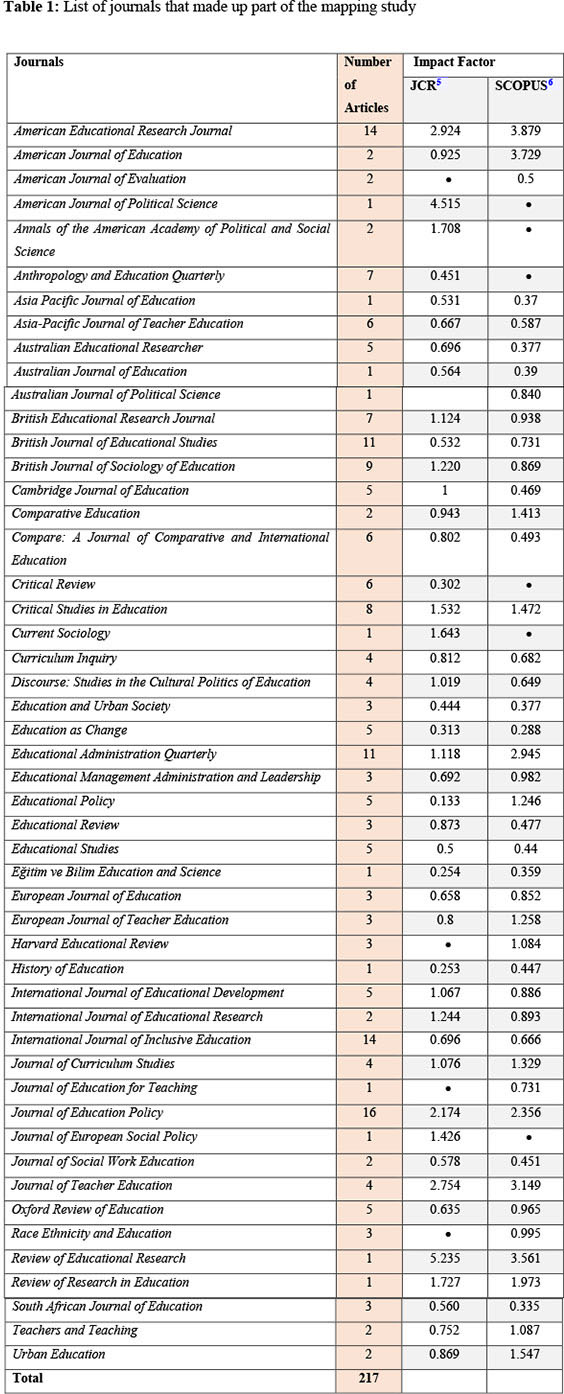

As a consequence of this process, the analysis focused on 217 articles from 50 scientific journals as shown in Table 1.

Each article was analysed through the process of content analysis (Bardin 2011; Krippendorff 2004) supported by NVivo software. All the articles were related to social justice, and after reading them several categories emerged. The texts from the articles were then codified and categorised. The unit senses/references were sentences, although in some circumstances entire paragraphs were also considered. In the coding process, the rule of mutual exclusivity of categories was not followed (L'Écuyer 1990). As a result, the analysis was based on 10 categories, with indicators outlined for each one as follows:

(1) School Evaluation includes all sentences/paragraphs focusing on a school's evaluation (internal and external), self-evaluation processes and learning assessment;

(2) Curriculum contains all sentences/paragraphs related to curriculum implementation, curriculum development, curriculum autonomy, curriculum policies and curricular justice;

(3) Democracy covers all sentences/paragraphs focusing on issues related to democracy in schools and democratic policies;

(4) Human Rights encompasses all sentences/paragraphs linked to the achievement of human rights, particularly in schools;

(5) Diversity/Multiculturalism includes all sentences/paragraphs focusing on diversity in schools and the development of multicultural projects and practices;

(6) Equity contains all sentences/paragraphs related to the implementation of equity policies, equity practices in schools and equity achievement;

(7) Inclusion covers all sentences/paragraphs regarding actions or changes implemented to make schools more inclusive, and inclusion policies;

(8) School Leadership covers all sentences/paragraphs associated with different types of school leadership and its influence on schools' and students' performance;

(9) Education Policies includes all sentences/paragraphs related to education policies in education focused on school improvement, students' success and the achievement of social justice;

(10) Teachers' Professional Practices contains all sentences/paragraphs concerning the influence of teachers' professional practices on students' success, and the influence of policies on teachers' work.

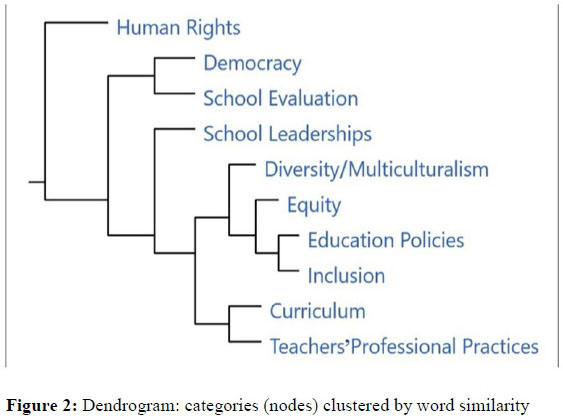

To better understand the relationship between these different categories, a cluster analysis of similar words was performed using the similarity metric Pearson correlation coefficient (=p). In other words, the cluster analysis generated a diagram clustering the categories (nodes) together where they shared many words in common. The Pearson correlation coefficient specifies whether the relationship between categories is strong or weak, in this case measuring word similarity correlation for each node compared with the other nodes. Looking at Figure 2, it is possible to see from this tree-structured graph which categories had more words in common and which groups of categories were created.

Pearson's correlation coefficient for word similarity identified the category "Human Rights" as an outliner, being an isolated branch and not coupled with any other category. The categories "Democracy" and "School Evaluation" (p = 0.713) were coupled together on the same branch, while "School Leadership" was coupled with all the remaining categories, though with different proximity values. "Curriculum" and "Teachers' Professional Practices" (p = 0.811) were strongly correlated, although the categories more strongly correlated were "Diversity/Multiculturalism" and "Equity" (p = 0.884), "Education Policies" and "Equity" (p = 0.932) and "Education Policies" and "Inclusion" (p = 0.952).

Given that this article is concerned with the concept of social justice and how curricular and evaluation practices are related to it, the above clustering shows this relationship more clearly, guiding the reading of the texts and informing discussion of the findings.

Findings and Discussion

By following the steps described above, this analysis of articles has allowed different dimensions to perspectives on social justice in its relationship with curriculum and school evaluation to be identified. The findings of the mapping performed are presented and discussed below.

Mapping Study Specifics

Before moving on to the main findings of this mapping study, it is worth noting that all the journals considered were written in English and that most came from the United States or the United Kingdom. There is a huge difference in the number of citations of English-language publications compared with non-English publications (Liang, Rousseau, and Zhong 2011). The Science Citation Index also covers non-English language journals, but papers in these journals have considerably lower impact than those in English-language journals. Another aspect to consider is that the United States and the United Kingdom have barely any publications in non-English-language journals (Van Leeuwen et al. 2001). Therefore, language and country biases play an important role in the comparison and evaluation of national science systems, which justifies the contextualisation of the findings and taking into account the tendencies that shape academic publications, i.e. a Western and Euro-centric perspective, since all articles analysed are written and published in English. Nevertheless, it is impossible to ignore the fact that these journals have a high impact factor, which means that they have more citations compared to other journals. Consequently, much of the knowledge disseminated about a specific issue is done considering the content of the articles published in these journals.

Bearing in mind this publication bias limitation, of the 217 articles analysed 123 came from journals from the United Kingdom, 66 from the United States, 19 from Australia, eight from South Africa and one from Turkey. Although many of the articles were from the United Kingdom, a higher number of them were written by authors affiliated to the United States.

There were 16 affiliated author countries, namely Australia, Canada, China, Cyprus, Denmark, Ireland, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, South Africa, Sweden, Turkey, the UK and the USA.

The oldest article analysed dated from 1990, the most recent from 2016. The majority were from 2012 (27) and 2010 (18). In relation to article distribution by category, most focused on issues relating to "Education Policies." With regard to the central themes of this paper, curriculum issues were present in 55 articles, school evaluation issues in 29 (in total 84 articles, 34% of the total). Since the United States and the United Kingdom had the highest number of articles, all the categories were represented in these countries' articles; however, the categories with the largest number of contributions were "Education Policies," "Inclusion," "Equity" and "Curriculum." For the Australian journals, the focus was the same. The Turkish article was about "School Leadership" and "Teachers' Professional Practices"; the latter category was present in all the journals except the South African ones.

Given the finding that curriculum and school evaluation made up 34 per cent of all the articles about social justice in these journals, these themes occupy considerable space in the published scientific literature on social justice issues. Still, the question remains: How has the concept of social justice been conceptualised and developed over the years in scientific publications related to curricular and school evaluation practices? After analysing the data-and given the complexity of the relationship between social justice, curriculum and school evaluation-is it possible to conclude if a reflection about school evaluation and curriculum practices, associated with social justice perspectives, is essential in order to understand their relationship?

Mapping Social Justice Perspectives: The Place of Curriculum and School Evaluation

From the analysis of the articles in this mapping study, it was possible to identify meanings and perspectives concerning the curriculum-social justice-school evaluation triad. These are described below.

Content analysis of the articles shows a focus on accountability and effectiveness in reflections on the relationship of social justice with curricular and school evaluation practices, albeit from different perspectives.

Back in the 1990s, when reflecting on the power of the economy and the influence of economic interests in the educational field, several authors (Epstein 1993; Gillborn 1997; Slee 1998) began to consider a process that emerged from this mutual influence, namely, accountability. It emerged because comparison had become a central mode of national and global governance (Nóvoa and Yariv-Mashal 2003), resulting in increasing pressure to follow new public management principles and new forms of network governance (Ball and Junemann 2012; Lingard, Sellar, and Savage 2014). In other words, comparing institutions through external evaluation processes became the basis of accountability processes in the educational field, especially with regard to schools, because accountability implies responsibility associated with judging performance (Frymier 1996).

Another relevant aspect of this analysis is that, for some authors, the external evaluation of schools is important because schools' actors inevitably have their blind spots (Lingard, Sellar, and Savage 2014) and therefore need external elements to help them reflect on their context and ways to improve. Other authors support the argument that the best way to improve a school is grounded in self-evaluation (MacBeath 1999; Swaffield and MacBeath 2005), because through it schools can know themselves and "reflect on the quality of the work they do, to decide on the evidence needed to make judgements on the activities and performance of the school, and to identify areas and strategies for improvement" (de Clercq 2007, 101). Nonetheless, and according to MacBeath (1999) self-evaluation may be insufficient on its own because schools can become complacent in their comfort zones and minimise their most difficult challenges. For these reasons, "external evaluators are often brought in to verify a school's self-evaluation process and write their own evaluation report with improvement recommendations. Such a step is supposed to help schools in the identification of their priorities and the development of improvement plans" (de Clercq 2007, 101). This kind of process is often associated with the primary aim of ensuring that schools function adequately, implying observation of schools' organisational and instructional processes, so that the appropriateness of their inputs, processes and outcomes can be established externally. Ideally, this external evaluation should not be imposed or based only on bureaucratic issues but, on the contrary, should instigate collaborative work among school actors. In this sense, it is important to clarify what notions of accountability support quality-improving processes for schooling for all (de Clercq 2007), particularly in their intrinsic relationship with school evaluation processes and social justice.

Accountability processes can be used as a way of performing standardised actions in order to achieve what is externally imposed, without taking into account issues linked to social justice in daily school life. An excessive focus on results can undermine students' success and educational improvement if the only focus of a school's actions is evaluation by testing. Furthermore, the pursuit of a re-articulation of social justice as equity through test-based accountabilities is linked to performance actions (Lyotard 1984) and new forms of governance in education (Ball 2013). In other words, this can happen because political discourses put decision-making on social justice issues by governing bodies to the back of their agenda; hence, different ways of understanding the concept of accountability have emerged as a way of giving attention to other crucial dimensions in the educational field and particularly school life (Epstein 1993). To overcome the logic of policy that accompanies evaluation by testing (Salinas and Reidel 2007)-"accountability through testing"-alternative ways of conceptualising accountability are needed, particularly those that include multiple performance indicators and focus on a more local and democratic form of evaluation (Salinas and Reidel 2007). So, to overcome the bureaucratic accountability (de Clercq 2007) process-i.e. one focused simply on achieving results-democratic accountability (Epstein 1993) or horizontal accountability (de Clercq 2007) may be the answer. The defence of these two forms of accountability, linked to a social justice perspective, values a negotiation between teachers and other school elements, especially students. This democratisation process should involve processes for the recognition of differences and provide opportunities for dialogue between those with opposing views, expressing commitment to anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive education (Epstein 1993).

The need to implement accountability processes is intrinsically linked to the pursuit of effectiveness in the educational field. On the one hand, effectiveness processes provide more information for parents and the community about students' performance in terms of detailed school examination results. On the other, it defines the content and the structure for how the curriculum should be organised and developed, which can put pressure on schools and increase the gap between specific student needs and a curriculum not adapted to them. Thus, educational change has been driven by effectiveness (Wrigley 2003) in that it shapes a school's public image and reduces educational processes to the need to achieve higher test scores; it therefore becomes attractive to politicians and governments prioritising a particular set of outcomes that schools are supposed to achieve. Wrigley (2003) shows that an anti-democratic tendency of school effectiveness is the construction of a framework that combines a research model, policy and discourses. For this author, the pursuit of school effectiveness is anti-democratic because it creates the idea that it can be achieved through education, equity and equality. This idea can trivialise learning, making it difficult to understand the forces that structure our lives by penalising those who are teaching and learning in marginalised and vulnerable communities. Therefore, this conception reduces reflection on education and its goals, thereby limiting teachers' pedagogical practices, particularly in terms of curriculum contextualisation and the search for equitable processes, which in turn increases the asymmetry in communication between teachers and students. An accountability system assumes that schools achieve equity through excellence in the results they achieve, and consequently equity discourses become obscured by discourses centred on excellence (Salinas and Reidel 2007). In other words, "in rating 'excellence' and not 'equity,' the State avoids genuine discussions and, thus, actions regarding school resources, quality teaching and wise assessment practices-essential components in achieving an equitable educational system" (Salinas and Reidel 2007, 52). That is why education policymakers in several countries "have struggled to marry their measures of effectiveness with the aspiration to provide equity in schooling outcomes" (Kelly 2012, 977), because for them the link between accountability, public examination success and equity is sound. However, "it is not clear what the targets should be, how they should be measured or how they should be spread across the range of prior attainment" (Kelly 2012, 978), implying continuing inequities in this process (Lingard, Sellar, and Savage 2014). In the same vein, it is not clear in what way curriculum and school evaluation are positively affected in order to contribute to equity and social justice implementation in schools.

Thinking about equity as the process by which students can access quality educational environments in which their different learning rhythms are considered, social justice as equity has been redefined in terms of comparative scores on national and international examinations and testing. Consequently, social justice as equity is shaped by economic rationalities and discourse (Lingard, Sellar, and Savage 2014) that greatly affect curriculum development. In this way, "the effectiveness movement is unnecessarily restricting the curriculum, narrowing the teaching approach to direct instruction and controlling teachers by judging them 'on task'" (Glickman 1987, 624) only when they teach to specific aims that are externally defined (Karikan and Ramsuran 2006). For this reason, the equity and social justice agenda is subjugated to the imperative of league tables documenting "high standards" in narrow curriculum areas (Hall et al. 2004).

Therefore, the curriculum can be seen as the battleground in which the theories and politics of knowledge meet classroom practice in complex and turbulent ways (Connell 1995; Smyth 2004); for this reason, it is necessary to replace the existing mainstream, "hegemonic" curriculum with one based on social justice (Au 2007; Clark 2006; Hatcher 1998). School effectiveness considers "outcomes" to be those by which effectiveness can be quantified, distorting the curriculum by prioritising what is easily measured (Wrigley 2003) and thus primarily focusing on results and numbers. In this sense, instead of pursuing the creation of a relationship between school effectiveness and school improvement, it is important to pursue models of educational development that involve discussion and value the processes and not just the numbers. From Apple's (2013) point of view, current educational policy, including curriculum development, results from an alliance between neoliberalism and neoconservativism. Thus, it should be recognised that "curriculum is centrally imposed, learning policed by 'high-stakes testing', and that teaching is regulated by inspection and performance pay" (Wrigley 2003, 96), where bureaucratic accountability frames curriculum development and schools' evaluation processes are subject to external demands.

Throughout this landscape, according to Slee (1998), the linking of teacher-training funding to inspection performance is sufficient inducement to conformity. Inadequately trained teachers (Hartwig 2013) are a way of increasing popular, top-down approaches to curricular content (McGregor 2009). For this reason, it is crucial to engage teachers in inclusive pedagogies that lead them to share "responsibility for the outcomes of all learners, plan strategies to address students' exclusion and underachievement, and work with other professionals" (Pantic 2015, 340), communities and families (Ainscow 2005; Edwards 2007). This is not easy to accomplish; thus, agency for social justice involves efforts to transform structures and school cultures (Pantic 2015). In other words, teachers' contribution to social justice requires their understanding how powerful social forces can influence exclusion and disadvantage (Slee 1998) and how they, as professionals, can individually and collectively affect the conditions for schooling and learning for all (Liston and Zeichner 1990; Pantic 2015). According to these ideas, it is fundamental that the organisation of teacher training programmes aims at closing the achievement gap between students (Miller and Martin 2015). Social justice as equity "requires an ongoing process of changing the pedagogical contexts in which teaching and learning occur" (Nagda, Gurin, and Lopez 2003, 167), and that is why agency for socialjustice is so important (Freedman 2007; McInerney 2003; Pantic 2015).

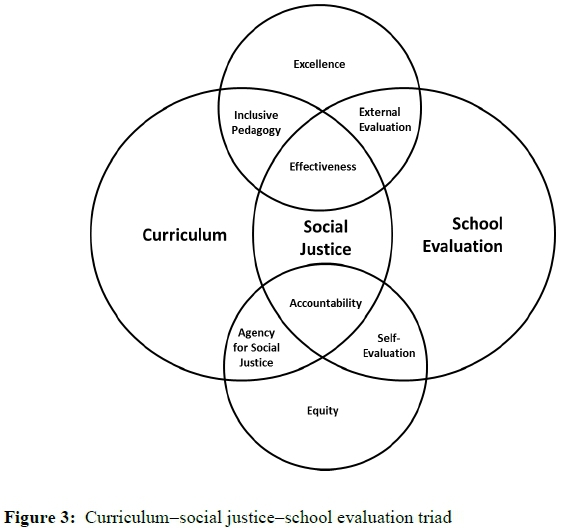

The relationship between all these issues is very complex and should be considered in the context of the evolution of societies and the educational policy measures implemented over the years. Figure 3 shows how these different concepts are interconnected and the meanings of the curriculum-social justice-school evaluation triad, taking into account the articles analysed in this mapping study.

In sum, accountability and the search for school effectiveness are two processes that strongly affect how curriculum and school evaluation are developed. On the one hand, they shape the way that social justice issues are considered by policymakers and, consequently, how the processes to achieve them are developed and implemented. The fact that the pursuit of excellence restricts reflection on equity is, in itself, revealing of the power of the economic agenda in the educational field. On the other hand, if there are some positive aspects about the actions of external elements in schools-namely through the process of external evaluation- the way schools develop their critical reflections is seen as one of the best routes to actual improvement. Therefore, education for social justice could be developed on the basis of self-evaluation processes and investment in teachers' professional actions-through agency for social justice-as the main path to achieving an inclusive pedagogy that could in turn be the basis for actions that are more social justice-oriented and sufficiently strong to face external pressures.

Conclusions

As mentioned above, this mapping study focused on a single, main question, namely, how is the concept of social justice in scientific publications related to curricular and school evaluation practices?

First of all, the concept of social justice has been developed, in the main, with a focus on equity issues. It embraces a broad view of equity, in which inclusion and democracy are central. Social justice seems to be recognised as a way to respond to multiculturalism and diversity. However, the political agenda, externally imposed, shapes all actions regarding social justice issues, especially in schools. Policy statements acknowledge that all students should be able to achieve their full potential and have the necessary support to do so. Nevertheless, the complex ways in which justice expresses itself through its "implementation will determine whether it is possible to base education on social justice principles" (Karikan and Ramsuran 2006, 14). If schools do in fact play a fundamental role in building an ideal of social justice, it is essential to pay attention to how school experiences are mediated by politics, power and ideology (Applebaum 2008), as well as to the contradictions among them.

In terms of the relationship of social justice with curriculum and school evaluation, from this mapping study it is possible to conclude that accountability and effectiveness have a strong influence on how these processes are developed. On the one hand, accountability is associated with responsibility, which leads to a perspective of judgment by evaluation. This focus on accountability is justified, in the articles analysed, by the premise that accountability systems assume schools to achieve equity through excellence; consequently, equity is obscured by discourses centred on excellence. This pursuit of excellence is cloaked in an excessive focus on final numbers and bureaucratic processes. Thus, equity is reconceived as a measure of the strength of correlation between student background and test performance (Lingard, Sellar, and Savage 2014). On the other hand, the need to achieve effectiveness shapes a school's public image and puts much pressure on both the results that school evaluation processes present and the way the curriculum is developed. In a world that values "numerocracy" above everything else, numbers overshadow any attempt at a more qualitative approach to accountability and school effectiveness reduces all educational processes to the need to achieve higher test scores. Both have considerable impact in terms of social justice and equity, because they increase the disadvantages of some social groups and limit teachers' practices in terms of curriculum contextualisation. This effectiveness movement restricts curriculum development, narrowing the teaching approach to instruction, and controls teachers by making them teach according to specific aims that are externally defined and often not sufficient in the real context.

In sum, the social justice agenda is subjugated to an economic imperative focused only on accountability and effectiveness processes. How, then, is it possible to fight this agenda and put greater value on processes based on social justice issues? A possible way forward is to substitute bureaucratic accountability processes with democratic and/or horizontal accountability processes, since the latter imply negotiation among all the actors involved in schools. In other words, we need to consider accountability and effectiveness in a more democratic way and, consequently, invest in a social justice orientation for evaluation (Kushner 2009; Thomas and Madison 2010) and pedagogical processes (Applebaum 2008). In addition, since evaluation practices have been linked to the curriculum as a possible way to better understand how schools' actions can lead to social justice implementation, self-evaluation is therefore the best way to improve a school because it gives rise to internal and joint reflection about a school's actions and what best fits students' needs.

References

Ainscow, M. 2005. "Developing Inclusive Education Systems: What Are the Levers for Change?" Journal of Educational Change 6 (2): 109-24.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-005-1298-4. [ Links ]

Apple, M. 2013. Can Education Change Society? New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Apple, M. W., S. Ball, and L. A. Gandin, eds. 2013. Sociologia da Educação: Análise Internacional. Porto Alegre: Penso Editora. [ Links ]

Apple, M. W., and J. A. Beane. 1995. Democratic Schools. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [ Links ]

Applebaum, B. 2008. "'Doesn't My Experience Count?' White Students, the Authority of Experience and Social Justice Pedagogy." Race, Ethnicity and Education 11 (4): 405-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320802478945. [ Links ]

Au, W. 2007. "High-Stakes Testing and Curricular Control: A Qualitative Metasynthesis." Educational Researcher 36 (5): 258-67. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X07306523. [ Links ]

Ball, S. J. 2013. The Education Debate. 2nd ed. Bristol: Policy Press. [ Links ]

Ball, S. J., and C. Junemann. 2012. Networks, New Governance and Education. Bristol: The Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781847429803.001.0001. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. 2011. Content Analysis. Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Clark, J. A. 2006. "Social Justice, Education and Schooling: Some Philosophical Issues." British Journal of Educational Studies 54 (3): 272-87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00352.x. [ Links ]

Connell, R. W. 1995. "Justiça, Conhecimento e Currículo na Educação Contemporânea." In Reestruturação Curricular, Teoria e Prática no Cotidiano da Escola, edited by L. H. Silva and J. C. Azevedo, 11-35. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes. [ Links ]

Connell, R. 2012. "Just Education." Journal of Education Policy 27 (5): 681-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.710022. [ Links ]

Cooper, D. 2016. "What Is a 'Mapping Study?'" Journal of the Medical Library Association 104 (1): 76-8. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.L013. [ Links ]

de Clercq, F. 2007. "School Monitoring and Change: A Critical Examination of Whole School-Evaluation." Education as Change 11 (2): 97-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/16823200709487168. [ Links ]

Dicheva, D., C. Dichev, G. Agre, and G. Angelova. 2015. "Gamification in Education: A Systematic Mapping Study." Educational Technology and Society 18 (3): 75-88. [ Links ]

Dubet, F. 2004. L'école des Chances: Qu'est-ce qu'une École Juste? Paris: Editions du Seuil. [ Links ]

Edwards, A. 2007. "Relational Agency in Professional Practice: A CHAT Analysis." Actio: An International Journal of Human Activity, no. 1, 1-17. [ Links ]

Elberzhager, F., J. Münchb, and V. T. N. Nha. 2012. "A Systematic Mapping Study on the Combination of Static and Dynamic Quality Assurance Techniques." Information and Software Technology 54 (1): 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2011.06.003. [ Links ]

Epstein, D. 1993. "Defining Accountability in Education." British Educational Research Journal 19 (3): 243-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192930190303. [ Links ]

Freedman, E. 2007. "Is Teaching for Social Justice Undemocratic?" Harvard Educational Review 77 (4): 442-73. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.77.4.hm13020523406485. [ Links ]

Frymier, J. 1996. Accountability in Education: Still an Evolving Concept. Bloomington: Phi. Delta Kappa Educational Foundation. [ Links ]

Gillborn, D. 1997. "Ethnicity and Educational Performance in the United Kingdom: Racism, Ethnicity, and Variability in Achievement." Anthropology and Education Quarterly 28 (3): 375-93. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.1997.28.3.375. [ Links ]

Glickman, C. 1987. "Good and/or Effective Schools: What Do We Want." Phi Delta Kappan 68 (8): 622-24. [ Links ]

Greene, J. 2005. "Evaluators as Stewards of the Public Good." In The Role of Cultural and Cultural Context: A Mandate for Inclusion, the Discovery of Truth, and Understanding in Evaluative Theory and Practice, edited by S. Hood, R. Hopson, and H. Frierson, 7-20. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Hall, K., J. Collins, S. Benjamin, M. Nind, and K. Sheehy. 2004. "Saturated Models of Pupildom: Assessment and Inclusion/Exclusion." British Educational Research Journal 30 (6): 801-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000279512. [ Links ]

Hartwig, K. A. 2013. "Using a Social Justice Framework to Assess Educational Quality in Tanzanian Schools." International Journal of Educational Development 33 (5): 487-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/iiiedudev.2012.05.006. [ Links ]

Hatcher, R. 1998. "Labour, Official School Improvement and Equality." Journal of Education Policy 13 (4): 485- 99. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093980130403. [ Links ]

House, E. 1990. "Methodology and Justice." In "Evaluation and Social Justice: Issues in Public Education," edited by K. A. Sirotnik, special issue, New Directions for Evaluation, no. 45, 23-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1539.

Karikan, K. M., and A. Ramsuran. 2006. "Is It Possible to Base Systemic Curriculum Reform on Principles of Social Justice?" Education as Change 10 (2): 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/16823200609487136. [ Links ]

Kelly, A. 2012. "Measuring 'Equity' and 'Equitability' in School Effectiveness Research." British Educational Research Journal 38 (6): 977-1002. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.605874. [ Links ]

Kitchenham B. A., D. Budgen, and O. P. Brereton. 2010. "The Value of Mapping Studies: A Participant-Observer Case Study." In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering: 25-33. Swindon: BCS Learning and Development. [ Links ]

Krippendorff, K. 2004. Content Analysis. An Introduction to Its Methodology. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Kushner, S. 2009. "Own Goals: Democracy, Evaluation, and Rights in Millennium Projects." In The SAGE International Handbook of Educational Evaluation, edited by K. E. Ryan and J. B. Cousins, 413-28. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226606.n23. [ Links ]

Laclau, E., and C. Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. London: Verso. [ Links ]

L'Écuyer, R. 1990. Methodologie De L 'analyse Développementale De Contenu. Quebec: Presses De l'Úniversité du Quebec. [ Links ]

Leite, C. 2002. O Currículo e o Multiculturalismo no Sistema Educativo Português. Coimbra: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [ Links ]

Leite, C., and P. Fernandes. 2010. "Desafios aos Professores na Construção de Mudanças Educacionais e Curriculares: que Possibilidades e que Constrangimentos." Revista Educação 33 (3): 198-204. [ Links ]

Liang, L. M., R. Rousseau, and Z. Zhong. 2011. "Non-English Journals and Papers in Physics: Bias in Citations?" In Proceedings of the ISSI2011 Conference, edited by E. Noyons, P. Ngulube, J. Leta, 463-73. ISSI: Leiden University and University of Zululand. Accessed 19 March 2018. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.459.9525&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Lingard, B., S. Sellar, and G. C. Savage. 2014. "Re-Articulating Social Justice as Equity in Schooling Policy: The Effects of Testing and Data Infrastructures." British Journal of Sociology of Education 35 (5): 710-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.919846. [ Links ]

Liston, D. P., and K. M. Zeichner. 1990. "Reflective Teaching and Action Research in Preservice Teacher Education." Journal of Education for Teaching 16 (3): 235-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260747900160304. [ Links ]

Lyotard, J. 1984. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Macbeath, J. 1999. Schools Must Speak for Themselves: The Case for School Self-Evaluation. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Macdonald, B. 1976. "Evaluation and the Control of Education." In Curriculum Evaluation Today: Trends and Implications, edited by D. Tawney, 125-36. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Mainardes, J., and M. I. Marcondes. 2009. "Entrevista com Stephen J. Ball: Um Diálogo Sobre Justiça Social, Pesquisa e Política Educacional." Educação & Sociedade 30 (106): 303-18. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302009000100015. [ Links ]

Mcgregor, G. 2009. "Educating for (Whose) Success? Schooling in an Age of Neo-Liberalism." British Journal of Sociology of Education 30 (3): 345-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690902812620. [ Links ]

McInerney, P. 2003. "Renegotiating Schooling for Social Justice in an Age of Marketisation." Australian Journal of Education 47 (3): 251-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494410304700305. [ Links ]

Miller, C. M., and B. N. Martin. 2015. "Principal Preparedness for Leading in Demographically Changing Schools: Where Is the Social Justice Training?" Educational Management Administration and Leadership 43 (1): 129-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213513185. [ Links ]

Nagda, B. A., P. Gurin, and G. E. Lopez. 2003. "Transformative Pedagogy for Democracy and Social Justice." Race, Ethnicity and Education 6 (2): 165-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320308199. [ Links ]

Nóvoa, A., and T. Yariv-Mashal. 2003. "Comparative Research in Education: A Mode of Governance or a Historical Journey?" Comparative Education 39 (4): 423-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006032000162002. [ Links ]

Ozga, J. 2009. "Governing Education through Data in England: From Regulation to Self-Evaluation." Journal of Education Policy 24 (2): 149-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930902733121. [ Links ]

Pantic, N. 2015. "A Model for Study of Teacher Agency for Social Justice." Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 21 (6): 759-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044332. [ Links ]

Petersen, K., R. Feldt, S. Mujtaba, and M. Mattson. 2008. "Systematic Mapping Studies in Software Engineering." In EASE'08 Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering: 68-77. Swinton: British Computer Society. Accessed March 10, 2018. http://www.robertfeldt.net/publications/petersenease08sysmapstudiesinse.pdf. [ Links ]

Petersen K., S. Vakkalanka, and L. Kuzniarz. 2015. "Guidelines for Conducting Systematic Mapping Studies in Software Engineering: An Update." Information and Software Technology 64 (8): 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/i.infsof.2015.03.007. [ Links ]

Rawls, J. 2003. Justiça como Equidade: Uma Reformulação. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Salinas, C. S., and M. Reidel. 2007. "The Cultural Politics of the Texas Educational Reform Agenda: Examining Who Gets What, When, and How." Anthropology and Education Quarterly 38 (1): 42-56. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2007.38.L42. [ Links ]

Santomé, J. T. 2013. La Justicia Curricular: el Caballo de Troya de la Cultura Escolar. Porto Alegre: Penso. [ Links ]

Slee, R. 1998. "Inclusive Education? This Must Signify 'New Times' in Educational Research." British Journal of Educational Studies 46 (4): 440-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/14678527.00095. [ Links ]

Smyth, J. 2004. "Social Capital and the 'Socially Just School.'" British Journal of Sociology of Education 25 (1): 19-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569032000155917. [ Links ]

Swaffield, S., and J. MacBeath. 2005. "School Self-Evaluation and the Role of a Critical Friend." Cambridge Journal of Education 35 (2): 239-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640500147037. [ Links ]

Thomas, V. G., and A. Madison. 2010. "Integration of Social Justice into the Teaching of Evaluation." American Journal of Evaluation 31 (4): 570-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214010368426. [ Links ]

Van Leeuwen, T., H. F. Moed, R. J. W. Tijssen, M. S. Visser, and A. F. J. Van Raan. 2001. "Language Biases in the Coverage of the Science Citation Index and Its Consequences for International Comparisons of National Research Performance." Scientometrics 51 (1): 33546. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010549719484. [ Links ]

Vincent, C. 2003. Social Justice, Education and Identity. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wrigley, T. 2003. "Is 'School Effectiveness' Anti-Democratic?" British Journal of Educational Studies 51 (2): 89-112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.t01-4-00228. [ Links ]

Zizek, S. 1989. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Zizek, S. 1991. For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Zizek, S. 1994. "The Spectre of Ideology." In Mapping Ideology, edited by S. Zizek, 1-34. London: Verso. [ Links ]

1 For Laclau and Mouffe (1985), a hegemonic force represents a certain view of totality or a certain sense of "truth." When thinking about curricula, Connell (1995; 2012) asserts that this hegemonic force makes the selection of knowledge unneutral because it is intimately related to the structure of society. That is why it is important to implement a curriculum based on diversity and equity principles.

2 Retrieved from http://wokinfo. com/products tools/multidisciplinary/webofscience/.

3 Retrieved from http://ip-science.thomsonreuters.com/cgi-bin/irnlst/iloptions.cgi?PC=SS.

4 Retrieved from http://ip-science.thomsonreuters.com/cgi-bin/irnlst/ilsubcatg.cgi?PC=SS.

5 Thomson Reuters' Journal Citation Reports.

6 SCOPUS SCImago Journal Rank.