Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Education as Change

versión On-line ISSN 1947-9417

versión impresa ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.21 no.3 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/2091

ARTICLE

Social networks among land reform beneficiaries and their use in supporting satellite schools in Zimbabwe: A case study of a satellite school

Kudzayi Savious TarisayiI; Sadhana ManikII

IUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa kudzayit@gmail.com

IIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Manik@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article examines the ways in which land reform beneficiaries in a selected community use their social networks to support a satellite school. Contemporary literature on the implications of land reform in Zimbabwe revealed a number of perspectives, which include the political, human rights, livelihoods, and agricultural productivity perspectives. However, a social capital perspective interrogating the educational benefits of land reform was absent. This paper reports on a study, guided by the social capital theoretical frameworks espoused by Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman and Robert Putnam, to unpack the influences that land reform beneficiaries have on a selected satellite school in Zimbabwe. This was principally a qualitative study with a case-study design. The data was generated through semi-structured interviews with one satellite school head, two village heads and three land reform beneficiaries as well as a focus group discussion with three land reform beneficiaries in Masvingo district. The study revealed social and educational benefits of the land reform beneficiaries for one selected community in Zimbabwe. Land reform beneficiaries used their social networks to voluntarily mobilise resources and share information, which facilitated the construction of a satellite school. The study further revealed that resource mobilisation and information sharing were important in the construction and infrastructural development of a satellite school in the aftermath of land reform in Zimbabwe.

Keywords: land reform; satellite schools; social capital; social networks; Zimbabwe

INTRODUCTION

While there is a plethora of literature on land reform and its benefit to livelihoods in Zimbabwe, including from a human rights perspective (Mabhena 2010; Mamdani 2008; Southall 2011), such scholarship is silent on the significance of social capital benefits of land reform for education. There is further negation of the contribution of the social networks of land reform beneficiaries to education through the construction of satellite schools. Thus, it can therefore be surmised that the social capital perspective of land reform in Zimbabwe has largely been overlooked. Thus, this article examines the educational benefits of the social networks of land reform beneficiaries to education in a selected community in Zimbabwe.

Community engagement in schools has been the subject of numerous studies around the world for some time (Chindanya 2011; Colletta and Perkins 1995; Desforges and Abouchaar 2003; Houtenville and Conway 2008; Kambuga 2013; Siririka 2007). In fact, community engagement in schools can be traced to Article 7 of the World Declaration on Education, which called for the strengthening of partnerships between government and communities in education provision that was adopted at the World Conference on Education held in Jomtien, Thailand in 1990 (Mupa 2012). Kambuga (2013) established from a study in Tanzania that community engagement in the construction of secondary schools consisted of either a cash contribution or a labour contribution. In another study in Zimbabwe, Chindanya (2011) states that community engagement included the provision of labour for the construction or renovation of school buildings. Thus, we (the authors) argue that community engagement in education is important as revealed by the literature reviewed and our findings in this study. However, these studies above are confined to community engagement in schools without necessarily interrogating the role of social networks as proffered by this present study (and this paper).

Interestingly, Bourdieu (1986, 244) argues "it is in fact impossible to account for the structure and functioning of the social world unless one reintroduces capital in all its forms." Therefore, the study from which this paper derives is an attempt to introduce the social capital perspective on land reform in Zimbabwe through an analysis of the social and educational benefits that accrue to satellite schools as a result of the land reform policies in Zimbabwe. Furthermore, the significance of social capital is elucidated by Grootaert (1997, 01) as "the missing link in development."

LAND REFORM AND EDUCATION IN ZIMBABWE

A recent compelling thread in the land reform discourse has sought to unravel the nexus between land reform and education in Zimbabwe. Scholars pursuing this thread contend that land reform in Zimbabwe led to an economic crisis which in turn adversely impacted education (Hlupo and Tsikira 2012; Shizha and Kariwo 2011). Thus, the standard of education in Zimbabwe fell due to the economic decay that accompanied the land reform. Within this thread of the literature on the relationship between land reform and education, a new phenomenon of satellite schools emerged in the year 2000 (Kabayanjiri 2012; Mutema 2012; Tarisayi 2015). Satellite schools were established during the course of land reform in Zimbabwe as a stopgap measure to secure education for communities in need post colonisation, but they have become a permanent feature in the education sector. Satellite schools are unregistered schools, which are attached to established schools for administrative purposes. Teachers at the satellite school are captured on the pay sheet of the established school, which is termed the mother school. Despite this linkage with the mother school, satellite schools have to autonomously mobilise for their own resources. Statistics reveal that there are 803 satellite secondary schools as well as 993 primary satellite schools in Zimbabwe (MoPSE 2015). Thus, it can be argued that land reform has inadvertently led to the establishment of satellite schools.

This paper commenced with a background to land reform in Zimbabwe from an array of perspectives and then argued for a social capital perspective to land reform in respect of the construction of a satellite school. The social capital theoretical frameworks from Bourdieu, Coleman and Putnam are examined below for their value to this study. This is followed by the methodology used to generate data and a presentation and discussion of the key findings. We argue that social capital has positive and negative aspects attached to it as is revealed in the land reform beneficiaries' interactions with the satellite school. We maintain however that the positives outweigh the negatives.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Social capital frameworks propounded by Pierre Bourdieu (1986), James Coleman (1988) and Robert Putnam (2000) guided the study (and this paper). Bourdieu views social capital from an individual level whereby benefits of social networks accrue to individuals, whereas Putnam and Coleman theorise the concept of social capital from a communitarian perspective, which states that benefits of social networks accrue to both individuals and communities. In addition, Bourdieu contends that the social world is bigger and thus it should not be limited to economic theory (Bourdieu 1986). According to Bourdieu, social phenomena should not only be analysed and conceptualised using economic theories and principles but social aspects should also be considered. Social capital has been interrogated in numerous disciplines: sociology, political science, economics and education among others, leading to a multiplicity of definitions (Narayan and Pritchett 1997; Robinson et al. 2002). Bourdieu (1986, 248) avers that social capital is "the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition." However, Putnam (2000, 67) opines social capital as "features of social organisation such as networks, norms and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation of mutual benefit." In addition, Woolcock (2001, 2) refers to social capital as "the norms and networks that facilitate collective action." Thus, the social capital framework entails resources that can be accessed by individuals as well as communities from social networks. Networks can be between individuals within the same communities and they are conceptualised as bonding social capital (Putnam 2000). Networks between individuals in different communities or across communities are conceptualised as bridging social capital. Therefore, this study views the social networks of land reform beneficiaries as a form of social capital, which facilitates combined action in the construction of the satellite school in Zimbabwe.

METHODOLOGY

The study is located within the interpretivist paradigm. A qualitative case-study research design was adopted. Qualitative research is viewed by White (2005, 127) as "more concerned with understanding social phenomena from the perspectives of the participant." Hence, the authors opted for qualitative research as they sought to understand how land reform beneficiaries use their social networks to interact with satellite schools. The case study was utilised because the authors' critical question used the question "how" and Yin (2003, 01) opines, "in general, case studies are the preferred strategy when 'how' or 'why' questions are being posed, when the investigator has little control over events and when the focus is a contemporary phenomenon within some real-life context."

Purposive sampling was used in this study to select participants in the community. The unit of analysis in this study was the social networks (of the land reform beneficiaries). The selected community for this study is in Masvingo Province. Masvingo Province is a dry area found in South-Central Zimbabwe (Kamanga, Shamudzarira, and Vaughan 2003). The study area has a unimodal rainfall pattern (Kamanga et al. 2003). Unimodal entails that there is only one rainfall season in the area. The authors sought to understand the influences of social networks of the land reform beneficiaries in their interactions with a satellite school.

Johnson and Christensen (2004, 175) aver, "purposive sampling constitutes the selection of information-rich cases." This study was conducted within one purposively selected district in Masvingo Province and within this district one community was purposively selected on the basis of their willingness to participate in the study. The study utilised nine participants, six farmers, two village heads and one satellite school head. An intensive literature review on land reform, social capital and satellite schools preceded data generation in the field. The literature review enabled the authors to expose gaps in the literature which could be addressed by this study. The data was generated using semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions. Six semi-structured interviews were carried out. In the selected community that participated in this study, three farmers, two village heads as well as a satellite school head were interviewed. In addition, one focus group discussion was conducted with three land reform beneficiaries. The researchers utilised the local vernacular for semi-structured interviews as well as focus group discussions as recommended by Nienaber (2010) in that participants should use their preferred home language when data is being generated. The researchers enlisted the help of two research colleagues at a local academic institution to validate the translations of each other thus minimising data that could have been lost in translation. The authors maintained "conceptual equivalence" in this study (Beck, Bernal, and Froman 2003).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the University of KwaZulu-Natal (Protocol reference number: HSS/1221/015D).

SOCIAL NETWORKS AND INFORMATION SHARING

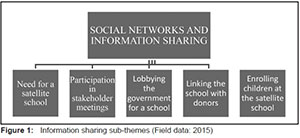

The sub-themes that emerged from the study are presented in Figure 1 below. The study established that the main theme was social networks and information sharing according to the participants in this study, as shown in Figure 1. The study revealed that the satellite school was influenced by the social networks of land reform beneficiaries through information sharing. The sub-themes which emerged are the need for a satellite school, participation in stakeholder meetings, lobbying government for a school, linking the school with donors and encouraging community members to enrol their children at the satellite school. This study supports the observations by Bardhan (1996) that social capital provides an informal structure to organise information sharing. Figure 1 shows the information sharing theme as well as its sub-themes. These sub-themes are outlined and discussed in the following section.

The Need for a Satellite School

The study established that prior to the construction of the satellite school by the land reform beneficiaries there was no school within their community. One participant revealed, "The government gave us land in an area without schools. The former owners of the land sent their children to boarding schools or schools in town." In addition, another participant stated, "There were no schools in the commercial farms when the land was redistributed to land reform beneficiaries. Thus, the children of land reform beneficiaries were forced to walk long distances to schools in other communities. During the rainy season the children had to cross a flooded river." It is evident that children in the community traversed lengthy distances to get to school and when it rained, the local river became a hazard to the school children. This finding concurs with Mutema (2012, 102) who revealed, "previously there were no schools around commercial farms as white farmers had very small families and they either drove their children to schools far away from their farms or sent them to boarding schools." Hence, it can be argued that there was a need for a school in the community that was selected for this study. In addition, it can also be revealed that the satellite school was a product of the land reform as the demand for a school was due to the resettlement of land reform beneficiaries in an area without the much-needed school.

Lobbying the Government for a School

The study further established that through their social networks land reform beneficiaries were instrumental in lobbying the government for a school. After realising that there were no schools in their community the land reform beneficiaries were able to come together and participate in stakeholder meetings. One land reform beneficiary revealed, "For our satellite school to be located here we sat down as neighbours, then as villages and lobbied the local leadership for a school. We approached the responsible authorities to give us a school." This contention was also supported by another participant who stated how strong their particular needs were for a satellite school in their community:

After realising that our children walked long distances to school and they had to cross a river during the rainy season, a meeting was called by the local leadership. At the meeting someone suggested that we liaise with the chief in lobbying for a school. We had to compete with a neighbouring community for the school but eventually we won the school.

It is evident that lobbying the government for a satellite school was done collectively and not as individual land reform beneficiaries. In addition, the study also established that traditional leadership was engaged to support lobbying the government for a school. Hence, it can be argued that traditional leadership was included in the social networks of land reform beneficiaries in their lobbying for a school. Thus, this study reveals that through their social networks land reform beneficiaries managed to successfully lobby the government for a school to cater for the community's immediate needs. Hence the researchers' argument is that to a large extent the satellite school was a product of the social networks of land reform beneficiaries.

Participation in Stakeholder Meetings

The need for a school in the community was initially agreed upon through stakeholder meetings, which were convened among the land reform beneficiaries (as discussed above). One participant revealed, "The need for a school was discussed at a stakeholder meeting and there was an agreement. Decision on the establishment of a satellite school was unanimous. It was also agreed to lobby the government for a school." Thus, the participants in this study revealed that their participation in stakeholder meetings was due to their social networks. The land reform beneficiaries used their social networks to facilitate information sharing which was instrumental in the mobilisation of community members to attend and participate as stakeholders. This is aptly revealed by another participant, who stated,

Our major participation in our school should be coming for meetings. We convene meetings very often to check on the progress of our school. The school normally sends a message to the village heads and the message is spread through the community from one farmer to the other. We encourage each other to come and share ideas on the development of our school and community. Other community announcements are also made at these school meetings, so you don't want to be left out.

The above articulation reveals that in addition to discussions on the development of the school, stakeholder meetings are valuable in sharing community announcements for the farmers. These stakeholder meetings were pivotal in the satellite school decision-making. The satellite school head revealed, "My relationship with the community is enhanced by regular meetings. The meetings allow us to clarify any issues coming from the farmers. This is helping a lot in maintaining very cordial relations between the school and the parents." The satellite school head further narrated how unfounded allegations against the satellite school were revealed through the stakeholder meetings (this is expanded upon in a later section below). Therefore, participation in stakeholder meetings by the land reform beneficiaries was essential in maintaining good relations between the head and the community where discussions unfolded and misunderstandings were revealed followed by the head providing explanations.

In addition, the stakeholder meetings were important for the mobilisation of resources for the construction of the satellite school as discussed. Resultantly, it can be argued that the social networks of the land reform beneficiaries enhanced their participation in stakeholder meetings, which can be viewed as their political participation in the governance of their community. Hence, the social networks of land reform beneficiaries facilitated the convening of stakeholder meetings, which were essential not only for the establishment and construction of the satellite school but also for engendering community governance. This finding was previously revealed by Krishna (2002, 5) who elaborated that "high social capital villages also tend to have significantly higher levels of political participation."

Linking the School with Donors

Land reform beneficiaries linked the school with donors in order to mobilise resources. The study exposed that land reform beneficiaries through their social networks were actively linking the satellite school with donors, both individual donors and nongovernmental organisations. A land reform beneficiary explained how a relative who had emigrated heard about their activities towards building a school and his remittances contributed to the building of the school. The satellite school head also explained

The farming community has taken it upon itself to share the plight of the school with their working children and relatives in towns and in the diaspora, churches and political parties. As a result, the school is getting donations from quite a number of individuals. For example, the farmers linked the school to churches and this resulted in the school receiving a substantial donation. So I can also add that the farmers are participating through connecting us with donors.

The land reform beneficiaries used their social networks to share information which facilitated linkages with donors. Gomez-Limon et al. (2012) and Nardone et al. (2010) concur that rural communities gifted with a rich stock of social capital are in a stronger position to share beneficial information and implement development projects.

Enrolling Children at the Satellite School

Another equally significant sub-theme that emerged from this study pertains to enrolling children at the satellite school. Land reform beneficiaries through their social networks encouraged each other to enrol their children at the satellite school despite the challenges they were going to face in the establishment of a new school. One village head revealed,

We are participating, although not directly, but I think giving the school our children (as learners) is the greatest support we are giving to the school. When the school started our children had to learn under trees but still we insisted that they go to our school and today we don't have any regrets.

In addition, one satellite school head revealed, "As you can see from our enrolment statistics we have an impressive enrolment. In fact, our school is now competing with well-established schools in terms of enrolment. The farmers are definitely giving us support through enrolling their children at our school." Land reform beneficiaries in the selected community supported the satellite school by enrolling their children despite challenges at satellite schools as revealed by Tarisayi (2015). Tarisayi (2015) avers that children in satellite schools face challenges such as a lack of resources, poor infrastructure, poor water and sanitation facilities among others. However, despite these numerous challenges at satellite schools, the land reform beneficiaries supported the school by showing their commitment in sending their children to the satellite school and in working towards overcoming the challenges.

Spreading Detrimental and Negative Information

The study also revealed that the social networks of the land reform beneficiaries had negative effects. The study established that some of the social networks of the land reform beneficiaries yielded negative dynamics in their interaction with the satellite school. The head of the satellite school bemoaned the negative repercussions of social capital emanating from the land reform beneficiaries. The school head revealed:

My predecessor fell victim to the rumours that were spread by the detractors within the community. He clashed with one member of staff who in turn engaged the local traditional leadership to have him expelled. Allegations of financial mismanagement were circulated and this led to Mr Makandaenzou [pseudonym] leaving. These allegations were later proved untrue by the district audit team.

Thus, from the contribution of the school head it can be revealed that the social networks of land reform beneficiaries did not only contribute positively but it also had negative effects. If the staff at the satellite school engaged with the community in spreading false information, this works contrary to the existing achievements of the community. The data did reveal that the land reform beneficiaries managed to overcome the detrimental negative dynamics through their enduring social networks. The negative effects of detrimental information were addressed by the land reform beneficiaries through stakeholder meetings. The satellite school managed to thrive despite temporary setbacks. Land reform beneficiaries revealed that one example of a temporary setback due to some of their social networks was the unjustified and unfounded allegations of financial mismanagement which forced one satellite school head to transfer. The fact that social capital has negative implications and externalities is underscored by Portes (1998). Portes (1998, 18) argues "sociability cuts both ways ... it can also lead to public bads." Hence, this study also established that the social capital of land reform beneficiaries caused "public bads" which involved the spreading of negative and detrimental information.

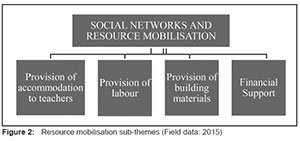

SOCIAL NETWORKS AND RESOURCE MOBILISATION

The social networks and resource mobilisation sub-themes that emerged from this study are the provision of accommodation to teachers, the provision of labour, and the provision of building materials and financial support. Figure 2 below shows the sub-themes of the social networks and resource mobilisation which emerged in this study.

The Provision of Building Materials

The study established that the land reform beneficiaries were able to share information to mobilise resources for the satellite school. The social networks of land reform beneficiaries were pivotal in harnessing building materials towards the construction of a satellite school in Zimbabwe. The participants in this study revealed that building materials such as river sand, pit sand, water and quarry stones, which are available in the school's environment, were donated by land reform beneficiaries. One participant revealed, "As farmers in this community we have provided our school with a lot. The classroom blocks that you see here, are products of the river and pit sand, bricks and stones that we provided as households."

In addition, another participant revealed,

We sat down as village heads and farmers and it was agreed that each household contribute sand, stones and water towards the construction of our first classroom block. Each household was tasked to deliver a certain amount of sand and stones. We were actually surprised by the overwhelming response we got from our community.

Another land reform beneficiary stated, "It is not possible to say how many wheelbarrows or scotch carts of sand and stones we contributed in the construction of our school. Whenever there was a need we were called upon to deliver more building material and we were always ready to help." Thus, the study established that through the social networks of land reform beneficiaries, the satellite school obtained building materials. The participants also revealed that it was difficult to ascertain the quantity of the building materials contributed by land reform beneficiaries to the satellite school. Moreover, this finding buttresses Fukuyama's (2002, 26) contention that, "social capital is what permits individuals to band together to defend their interests and organize to support collective needs." In addition, the provision of building materials revealed by this study concretises Pierre Bourdieu's view that social capital is the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network." (Bourdieu 1986, 248). The study further revealed that land reform beneficiaries willingly and voluntarily participated in resource mobilisation.

THE PROVISION OF LABOUR

Land reform beneficiaries were able to mobilise through their social networks in order to provide labour on a volunteer basis to build the satellite school. The researchers noted that satellite schools, being a "stopgap" measure by government, were heavily curtailed by resource constraints. Resultantly, satellite schools had to lean heavily on the social networks of land reform beneficiaries for labour if they were to be successful in their construction. The satellite school head elaborated that

The construction of our satellite school relied heavily on the voluntary participation of the farmers. The farmers provided labour starting from the clearing of the land. As a school we did not have money for most of the construction work, ferrying of sand and stones among others, so we called upon the community to assist and they did this through their networks.

Furthermore, another participant in this study explained, "Village heads organised our households to come and provide labour at our school. We worked at the school for at least three hours per week. Due to our large numbers this meant that we could do a lot of work every time we were called to assist." Hence, this study confirms the findings by Kambuga (2013) and Chindanya (2011) on the provision of labour by the community in the construction of schools. In addition, the provision of labour resonates with the argument that social networks expedite harmonising and collaborating for community benefit (Putnam 1995) as well as facilitating collective action (Woolcock 2001) for a community good.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The participants (school head, village heads and land reform beneficiaries) further revealed that the satellite school accrued financial support through the social networks of land reform beneficiaries. A traditional leader explained, "As farmers we have made financial contributions to our school. Those two classroom blocks over there, were roofed by us farmers. We shared the cost among ourselves. We told the school head that this is our school and we are prepared to make financial sacrifices for it."

In addition, the satellite school head explained the process of pooling together and collectively raising financial support for the school:

Parents in this community have been very supportive of developments at our school. Besides paying levies for their children they have made substantial financial contributions to the school.

The money for the roofing of two of our classroom blocks came from the farmers. The school could not raise the money from the levies collected, so the farmers chipped in with the help from the local leadership, they collected quotations and the cost was shared per household.

Therefore, the study established that the social networks of land reform beneficiaries were activated and they were converted to financial capital. Bourdieu (1986), Collier (1998) and Manik (2005) concur with this finding that social capital can be converted into financial capital. Manik (2005, 26) aptly reveals, "a particular trait of social capital is its convertibility most often to money." Therefore, it can be argued from this selected community that the social capital of the farmers was converted into money in support of the construction of the satellite school.

THE PROVISION OF ACCOMMODATION TO TEACHERS

The provision of accommodation to teachers is the other sub-theme that emerged from this study under resource mobilisation. Satellite schools were established in communities that had just undergone land reform in Zimbabwe. There were neither buildings nor structures to provide accommodation for teachers. Thus, through their social networks, land reform beneficiaries arranged interim accommodation for teachers at the satellite school. A village head who participated in this study revealed, "when the government gave us children to come and educate our community we welcomed them with open arms. We gave them places to stay amongst ourselves. As community leaders we asked farmers with good houses to accommodate our teachers while we were building houses at our school." Furthermore, another farmer stated, "The head of the satellite school stayed in my house while other teachers stayed with other farmers when our school was started. The teachers only came with their bags but there were no houses at the school site. We volunteered to accommodate them." Thus, this reveals that an accommodation deficit for teachers at the satellite school was obviated using the social networks of land reform beneficiaries who decided amongst themselves who had the better homes that could accommodate the arriving teachers whilst their facilities were under construction. The land reform beneficiaries, village heads and school heads who participated in this study were unanimous on the role of land reform beneficiaries' social networks in resource mobilisation for a satellite school. This finding on the resource mobilisation influence of land reform beneficiaries supports Muller's observation that, "social capital is also an important element of community capacity, and it is a resource on which community development work can build" (Muller 2010, 117).

CONCLUSIONS

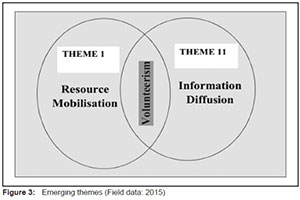

It was evident that resource mobilisation and information diffusion were critical components of the social networks of land reform beneficiaries.

Figure 3 above shows the major themes that emerged in the study and their relationship to each other. The figure further reveals that volunteerism permeated the two major themes and is thus a cross-cutting theme. The importance of volunteerism, in the social networks of the land reform beneficiaries, is aptly captured by a farmer who participated in this study: "The work we do here at our school and the contributions we make are all for free. It's all voluntary, from our hearts as parents and we don't expect the head or school to pay us. This is our school, no outsider can come and build the school for us." The ownership displayed by the farmer towards the school in the community is evident in his use of the pronouns "our" and "we" which explains why he (and his neighbours) volunteered. Therefore, the study established that land reform beneficiaries utilised their social networks for voluntary information sharing and resource mobilisation for the satellite school.

The study focused on the ways in which land reform beneficiaries used their social networks to support the establishment and building of a satellite school. The networks of land reform beneficiaries are viewed in this paper as enabling the farmers to reap benefits individually as well as to accrue benefits communally as aptly revealed by the construction of the satellite school. The findings suggest that the farmers used their social networks for information sharing and resource mobilisation. Land reform beneficiaries in the community that participated in this study used their social networks to establish that there was a need for a school, to participate in stakeholder meetings, to lobby the government for a school, to link the school with donors and to mobilise the community to enrol their children at the school. The social networks of the land reform beneficiaries in the selected community facilitated educating children through constructing a school. Most significantly, they have linked the school to donors to ensure the sustainability of the school. It can be concluded that land reform beneficiaries deepened the social networks amongst themselves by promoting regular engagement with each other to undertake tasks and to work with the school management towards achieving certain targets.

In addition, it is significant to note that the social networks of land reform beneficiaries are a double-edged resource: it can positively lead to the construction of satellite schools and also negatively impact on the professional lives of the staff. The study adds a new dimension to the view of social capital as a resource (Bourdieu 1986). Land reform beneficiaries relied on their social networks to mobilise resources. In addition, the study established that the social networks of land reform beneficiaries were a robust resource through its varied dimensions in the provision of building materials, labour and accommodation for teachers. Furthermore, land reform beneficiaries' social networks made the community both "efficient and cohesive" (Putnam 2000) and allowed them to engage with school challenges and overcome these. The land reform beneficiaries were also able to tap distant resources which are outside their community due to their social networks. The ability to access external resources from outside the community and country as established in this study concur with Putnam's (2000) observation. It was also noted from this study that the land reform beneficiaries are investing in education and their community through the construction of a satellite school. Thus, it follows from the social capital perspective pursued in this study that land reform in Zimbabwe was successful in as far as the establishment of a satellite school and the building of a strong community spirit and drive to achieve are concerned. From a social capital perspective, the land reform beneficiaries managed to mobilise an array of resources through their social networks to support a satellite school, but the journey was fraught with challenges that required the continued commitment of the satellite school and the community to overcome as a collective.

REFERENCES

Bardhan, P. 1996. "Research on Poverty and Development Twenty Years after Redistribution with Growth." In Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics 1995, edited by M. Bruno and B. Pleskovic, 59-72. Washington, DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

Beck, C. T., H. Bernal, and R. D. Froman. 2003. "Methods to Document Semantic Equivalence of a Translated Scale." Research in Nursing and Health 26 (1): 64-73. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10066 [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. 1986. "The Forms of Capital." In Handbook of Theory and Research in the Sociology of Education, edited by J. G. Richardson, 241-58. New York: Greenwald Press. [ Links ]

Chindanya, A. 2011. "Parental Involvement in Primary Schools: A Case Study of Zaka District of Zimbabwe." PhD dissertation, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Coleman, J. S. 1988. "Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital." The American Journal ofSociology, no. 94, 95-120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943 [ Links ]

Colletta, N. J., and G. Perkins. 1995. "Participation in Education." Environment Department Papers. Paper No.001. Participation Series. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Collier, P. 1998. "Social Capital and Poverty." Social Capital Initiative Working Paper 4. Washington DC: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Desforges, C., and A. Abouchaar. 2003. The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievement and Adjustment: A Literature Review. London: Department of Education and Skills. [ Links ]

Fukuyama, F. 2002. "Social Capital and Development: The Coming Agenda." SAIS Review 22 (1): 23-37. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2002.0009 [ Links ]

Gomez-Limon, J. A., E. Vera-Toscano, and F. E. Garrido-Fernandez. 2012. "Farmers' Contribution to Agricultural Social Capital: Evidence from Southern Spain." Instituto de Sociales Avanzados Working Paper series. Accessed November 6, 2017. http://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/58463/1/Farmers%20contribution%20to%20agricultural%20social%20capital-Working%20Paper-2012.pdf

Grootaert, C. 1997. "Social Capital: The Missing Link?" Social Capital Initiative Working Paper No. 3. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Hammer, A., B. Raftopoulos, and S. Jensen. 2003. Zimbabwe's Unfinished Business: Rethinking Land, State and Nation. Harare: Weaver Press. [ Links ]

Hlupo, T., and J. Tsikira. 2012. "A Comparative Analysis of Performance of Satellite Primary Schools and Their Mother Schools in Masvingo Province, Zimbabwe." Journal ofEmerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies 3 (5): 604-10. [ Links ]

Houtenville, A. J., and K. S. Conway. 2008. "Parental Effort, School Resources, and Student Achievement." The Journal ofHuman Resources 13 (2): 437-53. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2008.0027 [ Links ]

Johnson, B., and L. B. Christensen. 2004. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Approaches. Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

Kabayanjiri, K. 2012. "Overview of Satellite Schools in Resettled Areas." Accessed May 21, 2015. http://www.parlzim.gov.zw/attachments/article/35/20/

Kamanga, B. C. G., Z. Shamudzarira, and C. Vaughan. 2003. "On-Farm Legume Experimentation to Improve Soil Fertility in the Zimuto Communal Area Zimbabwe: Farmer Perceptions and Feedback." Risk Management Working Paper Series 03-02. Harare, Zimbabwe: CIMMYT. [ Links ]

Kambuga, Y. 2013. "The Role of Community Participation in the Ongoing Construction of Ward Based Secondary Schools: Lessons of Tanzania." International Journal of Education and Research 1 (7). [ Links ]

Krishna, A. 2002. "Enhancing Political Participation in Democracies: What Is the Role of Social Capital?" Comparative Political Studies 35 (4): 437-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414002035004003 [ Links ]

Mabhena, C. 2010. "'Visible Hectares, Vanishing Livelihoods': A Case of the Fast Track Land Reform and Resettlement Programme in Southern Matabeleland-Zimbabwe." PhD dissertation, University of Fort Hare. [ Links ]

Mamdani, M. 2008. "Lessons of Zimbabwe." London Review of Books 30 (23): 17-21. [ Links ]

Manik, S. 2005. "Trials, Tribulations and Triumphs of Transnational Teachers: Teacher Migration between South Africa and the United Kingdom." PhD dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Mapuva, J., and L. Muyengwa-Mapuva. 2014. "The Troubled Electoral Contestation in Zimbabwe." International Journal of Political Science and Development 2 (2): 15-22. [ Links ]

MoPSE (Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education). 2015. Curriculum Framework for Primary and Secondary Education (2015-2022). Harare: Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education. [ Links ]

Muller, J. 2010. "Operationalising Social Capital in Developing Political Economies-A Comparative Assessment and Analysis." PhD dissertation, University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Mupa, P. 2012. "Quality Assurance in the Teaching and Learning of HIV and AIDS in Primary Schools in Zimbabwe." PhD dissertation, Zimbabwe Open University. [ Links ]

Mutema, E. P. 2012. "The Fast Track Land Reform Programme: Reflecting on the Challenges and Opportunities for Resettled Former Farm Workers at Fairfield Farm in Gweru District, Zimbabwe." Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 14 (5): 96-106. [ Links ]

Narayan, D., and L. Pritchett. 1997. "Cents and Sociability: Household Income and Social Capital in Rural Tanzania." Social Capital Initiative Working Paper No. 17. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Nardone, G., R. Sisto, and A. Lopolito. 2010. "Social Capital in the Leader Initiative: A Methodological Approach." Journal of Rural Studies 26 (1): 63-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjrurstud.2009.09.001 [ Links ]

Nienaber, A. 2010. "The Regulation of Informed Consent to Participation of Clinical Research by Mentally Ill Persons in South Africa: An Overview." South African Journal of Psychiatry 16 (4): 118-24. [ Links ]

Portes, A. 1998. "Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology." Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1): 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.L1 [ Links ]

Putnam, R. D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. https://doi.org/10.1145/358916.361990 [ Links ]

Robinson, L. J., A. A. Schmid, and M. E. Siles. 2002. "Is Social Capital Really Capital?" Review of Social Economy 60 (1): 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760110127074 [ Links ]

Sachikonye, L. M. 2003. "The Situation of Commercial Farm Workers after Land Reform in Zimbabwe: A Report Prepared for the Farm Community Trust of Zimbabwe." Accessed November 3, 2017. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.590.2155&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Shizha, E., and M. T. Kariwo. 2011. Education and Development in Zimbabwe: A Social, Political and Economic Analysis. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-606-9 [ Links ]

Siririka, G. 2007. "An Investigation of Parental Involvement in the Development of Their Children's Literacy in a Rural Namibian School." MEd dissertation, Rhodes University. [ Links ]

Southall, R. 2011. "Too Soon to Tell? Land Reform in Zimbabwe." Africa Spectrum 46 (3): 83-97. [ Links ]

Tarisayi, K. S. 2014. "Land Reform: An Analysis of Definitions, Types and Approaches." Asian Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development 4 (3): 195-99. [ Links ]

Tarisayi, K. S. 2015. "An Exploration of the Challenges Encountered by Satellite Schools in Masvingo District, Zimbabwe." Journal for Studies in Management and Planning 1 (9): 304-8. [ Links ]

White, C. J. 2005. Research: A Practical Guide. Pretoria: Ithutuko Investments. [ Links ]

Woolcock, M. 2001. "The Place of Social Capital in Understanding Social and Economic Outcomes." Canadian Journal of Policy Research 2 (1): 11-7. [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]