Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.21 n.3 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/1374

ARTICLE

School leadership and accountability in managerialist times: Implications for South African public schools

Jabulani E. MpungoseI; Thengani H. NgwenyaII

IQwenguhaya (Pty) Ltd Consulting, South Africa jabulani.mpungose@gmail.com

IIDurban university of Technology, South Africa Ngwenyat@dut.ac.za

ABSTRACT

While it is argued in the paper that the New Public Management theory and practice has been applied much more in education than in any other area in the public sector, literature on education leadership and management still reveals a startling degree of confusion among education authorities, managers and leaders over what strategies to apply in order to bring out commitment, positive results and accountability among the school leaders. The authors argue that the confusion is caused by the fact that there has been a dramatic change in education policymaking that has adopted a more market-oriented approach and underplayed the conception of "education as a public good." The authors conclude that this change has led to the obsession of educational authorities with quantifiable outcomes which have an adverse effect on the standard and quality of education in South Africa.

Keywords: accountability; education policymaking; learner performance; market-oriented; new public management; performance-based; performativity; self-managing school

INTRODUCTION

This exploratory paper examines the application and practical consequences of New Public Management (NPM) principles in public education in South African (SA) public schools. The paper focuses primarily on the issue of accountability of school leadership for educational outcomes in national assessments. It argues that the obsession of educational authorities with quantifiable outcomes not only detracts from the purpose of government-funded education as a public good with humanistic goals but also significantly undermines the quality of education by unnecessarily foregrounding results and narrowly defined performance at the expense of processes. In addition, it is argued that the concept of "outcomes" should not be confined to those that are quantifiable but should include attributes that high school graduates should exemplify, such as critical citizenship and critical self-awareness.

The paper seeks to demonstrate in a discursive and argumentative manner that NPM is not clearly distinguishable from the notion of performativity as defined by Stephen Ball (2003, 1) below:

Performativity ... is a new mode of state regulation which makes it possible to govern in an "advanced liberal" way. It requires individual practitioners to organise themselves as a response to targets, indicators, and evaluations. To set aside personal beliefs and commitments and live an existence of calculation.

In an incisive analysis of educator post provisioning, Naicker (2005, 95) drawing on Mok (1999) makes illuminating remarks about the global pervasiveness of managerialism and its impact on South African schools:

In search for better performance in the public sector, Mok (1999: 2) notes that some fashionable terms such as "excellence," "increasing competitiveness," "efficiency," "accountability," "devolution" and "self-managing schools" have been introduced in order to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of public services.

The paper draws from the increasing concern among the education officials at national and provincial levels and parents about the poor teacher and learner performance in public schools, especially the under-resourced black schools since the beginning of the democratic South African education system. The poor performance of teachers is always identified during the performance appraisal exercise, and from the learners' examination results, especially the National Senior Certificate (NSC) results. Poor examination results are always blamed on poor teaching practice, which itself is blamed on poor leadership by the principal. Unfortunately, the focus tends to be primarily on the outcomes of the system rather than the process of learning, teaching, strategic leadership and good governance of schools. This is directly traceable to NPM which foregrounds outcomes (often in the form of productivity and profits) in private sector organisations. In education, there is therefore a sense in which the NSC results in schools are seen as equivalent to the notion of "profit" in private sector organisations. This is hardly surprising as the ideology underpinning NPM has been borrowed from the private sector. As Thabang Motsohi (2017) points out, the unwarranted over-emphasis on the pass rates per school detracts from viewing the schooling system holistically:

An education system has different components and dimensions. No single performance metric will be able to provide a comprehensive understanding of how the system works and where the fault lines are. A critical understanding of the efficiency of any system involves measuring changes that occur to any inputs while in the system, and the quality of the outcomes.

South African scholars have also commented on the ideological underpinnings of the country's secondary education system. For example, Hein Marais (2011, 330) comments as follows on the outcomes of "outcomes-based education," the effects of which still linger on in the policy and regulatory framework:

A key feature was the design of mechanistic performance statements against which education would be measured. Linked to the approach were performance-based accountability systems, which bristled with testing and surveillance measures. What was meant to facilitate a more organic and eclectic learning process became highly regimented and highly supervised.

As Ferlie, Ashburner, Fitzgerald and Pettigrew (2006, 9-10) have argued in their seminal book The New Public Management in Action, "the new public management movement [could be seen] as an ideological thought system, characterized by the importation of ideas generated in private sector settings within public sector organisations." According to Ha-Joon Chang (2010, xiii) "the free-market ideology has ruled the world since the 1980s." He goes on to make the following observations about what could be described as the neo-liberal ideology which regards "the invisible hand of the market" as the key determinant of all public policies including those governing public education:

We have been told that, if left alone, markets will produce the most efficient and just outcome. Efficient, because individuals know best how to utilize the resources they command, and just, because the competitive market process ensures that individuals are rewarded according to their productivity.

Taking its cue from the critique of NPM presented above, the paper examines the way in which the New Public Management principles play themselves out in the way the government deals with the NSC results and the unintended consequences of the role of government interventions in schools that are deemed to be underperforming. The sole criterion in judging performance is often the pass rate in NSC examinations. As mentioned above, this obsession with outcomes has had an adverse effect on the standard and quality of secondary school education in SA public schools. Like private sector organisations, schools are judged on the narrowly defined criterion of "results" and the complex contextual factors which impede the attainment of sound educational goals are often ignored or underplayed.

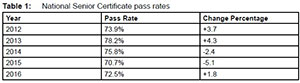

Evidence which backs the authors' claims in this paper is found in the Basic Education Minister's end-of-academic year speeches which are centred around the NSC results, when she constantly refers to numbers in the form of percentages which do not indicate the number of failures resulting from negative factors such as a shortage of qualified science and maths teachers experienced especially by under-resourced black schools. In January 2016, she said that "the basic education sector is about excellence and perpetual acts of performing good habits," which clearly says that the focus in the NSC is on producing excellent results in order to maintain good performance standards (Motshekga 2016). Table 1 below shows the NSC pass rates that were presented by the Minister from 2012 to 2016:

As reflected in Table 1, for the past five years the NSC pass rate has ranged between 70.7 per cent and 78.2 per cent. In fact, there has been a significant decline from 2014 to 2016. What is worth pointing out, however, is that the figures do not tell us much about the contextual factors that have a direct bearing on the learners' academic performance. These factors include the quality of school management and teaching, the availability of resources, the "quality" of the NSC passes (the quality in this context refers to knowledge, skills and competences that are ostensibly denoted by symbols or marks obtained by the students in the NSC examinations), etc.

Walton (2017) is also not convinced that "this annual obsession with matric results is productive." She goes on to say,

The national pass rate is a very blunt instrument with which to dissect South Africa's very complex educational problems. The national pass rate obscures important differences in provincial achievements, the urban/rural divide and the unequal outcomes for pupils in poorer schools.

Table 2 below show the provincial pass rates for 2014 that were presented by the Minister on January 6, 2015:

The NSC provincial results in 2014 also indicate a drop in the learners' performance from a good performance in 2013. In her speech in January 2015, the Minister did not give a reason for the decline but simply said that her department "need[s] to look seriously into the factors affecting the performance" (Motshekga 2015).

Very often the parents and local community members have expressed concerns about the poor leadership of the principals of these schools, which they sometimes say lacks vision and commitment. Sometimes the negative "blame the boss" spin (Hambleton 2003) is used to benefit teachers who are not doing their work well and thus manage and succeed in covering their ineffectiveness in class. However, if the plea for positive leadership is genuine, the blame should be shared among the school management team who should work together towards a clear vision and performance standards for the organisation to inspire collective commitment among the teachers. However, the principal as a leader has a key role to play in satisfying the "clients" by producing good results and being accountable for teachers' and leaners' performances.

Research in the fields of educational leadership (Oldroyd 2003), educational management and governance (Fusarelli and Johnson 2004; O'Hara, McNamara, Boyle, and Sullivan 2007) has revealed a startling degree of confusion among education authorities, managers and leaders over what strategies to apply in order to produce effective and successful leadership that promotes commitment, positive results and accountability. As a result, education policymaking has changed in the past two decades with the incorporation of outcomes-based accountability, performance standards and measurement, and flexibility (Fusarelli and Johnson 2004; Pfiffner 2004). These reforms are located within some of the South African education policies, such as the South African Schools Act (SASA) and the Integrated Quality Management System (IQMS).

UNDERSTANDING LEADERSHIP

Generally, leadership in the public sector is an important component of good management and good public-sector management in particular. It can lead "to a superior management level and higher organisational performance which also integrates efficient human resources management and establishes public services ethics" (Çetin 2012, 76). Prindle (2012, 9) refers to leadership as a "critical component of an agency's organizational context [that] has an important influence on an organizational change strategy and how it impacts the organization." In contemporary discourses on leadership (Phaneuf 2007, 1), the term leadership, refers to

a person who holds a dominant position and it is often used to describe people who exercise a certain influence, either because of their professional role or their personal charisma. Today we also use the term leader to refer to any manager or person in a position of responsibility.

Contemporary leadership researchers (Kan and Parry 2004, 468) maintain that "leadership is a dynamic, situation-based social process that is contingent upon culture and context." The notion of leadership as a process supports the idea that leaders of organisations exist within groups of followers with whom they interact, communicate and grapple with issues of organisational structure and policies. This is the time during which leaders need to be effective by leading their followers to attain positive outcomes for their organisations and clients.

In this paper, leadership is regarded as a concept that subsumes the technical and procedural activities commonly known as management. Leadership is essentially about values, vision, strategy execution and ethics. A good leader has the capability to persuade his or her followers to share his or her values and vision, and to inculcate ethical behaviour among them to strengthen effectiveness and efficiency in the organisation. Leadership is not entirely quantifiable or measurable but is more than anything else about the complex interplay between biography and context. Because leadership is an inherently elusive concept, it is rarely used in the empiricist and positivistic discourse of managerialism, the preferred term of which is management. Real leadership promotes a desire to articulate a clear vision for the organisation that can shape clear standards for performance and inspire commitment to shared values and aspirations (Hambleton 2003).

The concept of leadership has been defined and discussed in different contexts for many decades and there has been agreement that there is not one definition of leadership, but many. Hambleton (2003) and Çetin (2012) seem to agree that there have been dramatic changes from traditional leadership practices to contemporary leadership practices.

In this paper, literature on theories and concepts relating to educational leadership is examined and an attempt is made to understand the changing context of school leadership by analysing the progressive humanistic leadership in relation to the "ideology" of the "new public management" and the "resistance leadership" approaches. Furthermore, questions are raised about the role of the principal within the context of management which has increasingly become managerialist in orientation.

The progressive humanistic leadership is associated with the policy and leadership practices that were in place in the South African education system up to the early 21st century when quality management policies were introduced.

Progressive humanistic leadership favours a "holistic, child-centred approach to leadership in which school leaders adopt a proactive, empowering and participative approach based on humane values of personal and organisational learning" (Oldroyd 2003, 49). Progressive humanist leadership seeks to empower teachers and learners based on principles of humanism. "Humanism is a philosophy that recognizes the dignity and worth of each and every human on the planet" (Hancock 2011a, 1). A humanistic leader treats people with respect, is ethical, responsible and compassionate. They are "dedicated to make the best most ethical decisions they can make and strive to use logic, critical thinking, reason and reality when making such decisions" (Hancock 2011b).

In progressive humanistic leadership, the key elements that are emphasised are developing the human potential of both learners and teachers, encouraging the participation of all stakeholders in decision-making and problem solving, and promoting professional learning communities that produce empowered and resourceful citizens who can deal with any challenges. Perruci and Schwartz (2002) maintain that progressive humanistic leadership combines utilitarian and communitarian approaches to leadership because it promotes both individual and community needs.

The school leader's main responsibility, in the progressive humanistic leadership, is to take care of the interests of the "whole child" and to develop capacity among teachers for self-determination and continuous improvement (Oldroyd 2003). What is important about this leadership is that teaching and learning are not for commercial or market purposes but for professional empowerment and life-long learning. While the manager is "influencing the actions, beliefs and values of teachers, learners and parents, he is also building good interpersonal relationships based on trust" (Phaneuf 2007).

Over and above building interpersonal relations, the humanistic leader should be capable of giving moral support when problems arise. This role can call for important skills like being able to reflect on and analyse information, combine theory and practice and be in a position to solve problems. The decisions that the leader takes should be based on knowledge and not just assumption. "Knowledge cannot be divorced from action, and action should be grounded in one's moral ethics" (Perruci and Schwartz 2002). Finally, the humanistic leader should live a life that is infused "with meaning and purpose, giving back to society and making the world a better place" (Hancock 2011b).

Oldroyd (2003) traces the changes from traditional policy and leadership practices which he terms "progressive humanistic leadership" to current policy and leadership practices called the "new public management."

The New Pubic Management (NPM) "is driven by results and demands for accountability. The drive is led by politicians for higher, measurable and visible standards of effectiveness and efficiency, and equity to meet the challenges of global competition in a rapidly changing world" (Oldroyd 2003, 49). Advocates of the New Public Management refer to it as "a paradigm shift from the traditional model" (O'Flynn 2007, 353) of public administration to a more market-oriented approach to management. "It can be defined as a new approach to public administration that borrows knowledge and experiences from the private sector," specifically from business management, "to improve efficiency, effectiveness, and general performance of public services" (Verger and Curran 2014, 1).

The New Public Management is concerned with the commercialisation of the government's role in providing services to the people and of the government's relationship with the people. Johannesson, Lindblad and Simola (2002) argue that the marketisation of every sphere of public life represents a radical move away from the concerns around compassion, empowerment and human development that dominated public policy discourse in the progressive humanistic approach. In this study, we witness a state that has become increasingly regulatory by imposing its policies on schools and has concomitantly become increasingly evaluative. This new management practice is "a convergence of the business and public sector codes" (Oldroyd 2003, 50) characterised by concepts such as accountability, goal setting, quality, competence, empowerment, choice, transparency, managerialism and privatisation (O'Hara et al. 2007). Managerialism refers to the style of management normally associated with the private sector where the central focus of all organisational activities is on productivity and profit.

Education was one of the public services that was greatly influenced by the New Public Management. As new changes were introduced, new policies needed to be formulated and implemented, and existing ones needed to be amended in order to address the business proponents' remark that the "New Public Management theory and practice has been applied in education much more than in any other area" in the public sector (O'Hara et al. 2007, 76).

The introduction of the New Public Management in education meant "the promotion of school autonomy and a managerialist approach to school organization" (Verger and Curran 2014, 4). Autonomy meant that schools were given powers to manage their own affairs, "including budgeting, resource allocation, hiring of staff, role of stakeholders- especially parents given status statutory powers" (Kolwalczyk and Jakubczak 2014). The market-driven competition that began to exist between schools changed the traditional collegiality pattern of behaviour in the education system to a performance-based approach (Verger and Curran 2014). "As a result, schools were subjected to government regulation and scrutiny by means of setting and monitoring of performance targets and standards through performance evaluation or assessment" (O'Hara et al. 2007, 77).

The autonomy of schools also meant that the roles of principals should change. They were given more power and added responsibilities to make decisions, independently manage the schools' economic and human resources, and manage change. "The roles of the principals became corporate, imitating the way Chief Executive Officers (CEO) of private or business enterprises use profitability to account for performance" (Oldroyd 2003, 52).

The changes and the new and amended policies that were introduced in education by the post-1994 governments were in most cases met with resistance by the staff and parents at schools. Van der Westhuizen and Theron believe that resistance will arise when change is implemented. They go on to say that resistance can be avoided if school leaders "who are responsible for the implementation of any form of change, recognize the factors that cause resistance to change, and know how to manage resistance to change on their level of authority" (1996, 1).

Resistance leadership is a process where a leader transforms the energy of the challenges they encounter into sources of creating opportunities. In this process, the leader engages productively with resistance in the context of a relationship within which skills matter and in which practice improves performance (Wasserman, Gallegos, and Ferdman 2008, 177). Resistance leadership focuses on what an effective leader does- that is, listening to the story and reasons behind resistance and engaging with it instead of arguing about it-rather than who the leader is (Prindle 2012). Resistance in this paper is viewed in a managerial context as an expression, something to be engaged with and as a form of data to be understood to provide important information for fostering shared meaning (Wasserman et al. 2008).

Resistance to change in education is seen "as a struggle against the change of existing policies, practices and customs" (Dalin 1978, 23). It can also be viewed as a force that slows or stops the implementation of new policies, new practices and processes of professional development for teachers. Maurer (1996) does not regard resistance to change as a negative force, but rather as an integral part of a change process that "can be positively applied to the advantage of a school or organisation" (Van der Westhuizen and Theron 1996, 3). This statement does not imply that school leaders should not take resistance action by their staff as a threat to the stability and harmony in the organisation.

There are different types of scenarios that are prevalent in many schools because of many change requirements and instructions from the central authorities. Among some there is a scenario where teachers resist being team players and sharing responsibility. They refuse to commit because "where teams operate the principal cannot be blamed since the team works together to solve problems" (Steyn 2002, 251). Another scenario is when the school leaders and teachers do not agree on the system of staff appraisal and the approach to teacher professional development. Lastly is when the principal and teachers resist sharing decision-making powers with the parents who are members of the School Governing Body (SGB).

In their efforts to implement the elements of accountability and outcomes-based performance management in the South African public schools, the school leaders should try to know and understand their teachers' past experiences of change. They should however, also guard against succumbing to their own poor and ineffective leadership skills, characterised by uncertainty, a lack of trust and commitment, poor decision-making and blaming teachers for resisting change (Wasserman et al. 2008; Zimmerman 2006).

NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN CONTEXT

Policy makers in South Africa are engaged in what could be best conceptualised as a balancing act as they grapple with the pressure for economic efficiency on the one hand, and the need for the equitable distribution of resources on the other hand. They have to strike a balance between the conflicting demands for global competitiveness and being responsive to the needs of the majority of South Africans who belong to what has been accurately described as the second economy by former President Thabo Mbeki. Oldroyd (2003, 52) refers to this as striking "a balance between contrasting managerialist and progressive values." The pressure of global forces on South African policy formation was nowhere better dramatised than in dumping what was called the Reconstruction and Development Policy (RDP) in favour of a policy that suited international multinational corporations called GEAR. GEAR and subsequent economic policies have had a direct impact on education as they are all premised on quantifiable results. The former foregrounds equity and redistribution while the latter sees everything as dependent on market forces. Not surprisingly, this balancing act is also playing itself out in education policies. Student performance is still directly traceable to the availability of both material and human resources as well as above-average standards of leadership and management.

In its quest for international acceptance the South African government adopted styles of public service management which are hardly distinguishable from those used in the private sector. In this mode of public management, no distinction is made between education as a public good and education as a service or even a commodity to be sold to clients or consumers. In the literature on school management we have witnessed the emergence of the notion of a self-reliant or self-managing school which can also be referred to as an autonomous, self-sufficient entity that is managed like a private sector organisation. Caldwell (2013, 2) defines a self-managing school as

One for which there has been significant and consistent decentralization to the school level of authority to make decisions related to the allocation of resources within a centrally-determined framework of goals, policies, curriculum, standards and accountabilities. Resources are defined broadly to include staff, services and infrastructure, each of which will typically entail the allocation of funds to reflect local priorities.

A self-reliant or self-managing school is managed by a principal who is expected to play a role similar to that of a CEO of a private company and who:

• competes aggressively with neighbouring schools for good students;

• markets his/her school aggressively;

• raises funds for the school in conventional and unconventional ways and does not rely on government funding to run the school;

• is an astute financial manager who has learned to do more with less; and

• is results oriented.

A self-reliant or self-managing school is managed in accordance with the key principles of New Public Management (NPM), the key features of which are:

• an emphasis on hands-on professional management skills for active, visible, discretionary control of organisations (freedom to manage);

• explicit standards and measures of performance through the clarification of goals, targets, and indicators of success;

• a shift from the use of input controls and bureaucratic procedures to rules relying on output controls measured by quantitative performance indicators;

• a shift from unified management systems to disaggregation or the decentralisation of units in the public sector;

• an introduction of greater competition in the public sector so as to lower costs and achieve higher standards through term contracts, etc.;

• a stress on private-sector style management practices, such as the use of short-term labour contracts, the development of corporate plans, performance agreements, and mission statements; and

• a stress on cost-cutting, efficiency, parsimony in resource use, and "doing more with less."

Education policies including the South African Schools Act (SASA) and the Integrated Quality Management System (IQMS) reflect the drive by policy makers to make South African public schools self-sufficient and relatively independent. This is particularly evident in the sphere of school governance which has been given to School Governing Bodies (SGBs) and to the communities in which the schools are located. School Governing Bodies, which are composed of teachers, parents and local authorities who are involved in the schools' existence, ensure that all local stakeholders participate in a consultative or decision-making role. While this strategy would work fairly well in a first world economy and in middle-class suburbs it cannot be implemented without major problems in working-class residential areas such as townships and informal settlements where the majority of South Africans live. In simple terms, this law cannot function in an uneven playing field, meaning that the socio-economic conditions in the working-class communities are poor and the SGBs can therefore not function effectively and efficiently. It is therefore not surprising that it is affluent communities who would like to see SGBs given total authority to govern schools and poor communities who wish to see the government playing a central role in key governance functions such as the appointment of educators. This, however, does not mean that these communities cannot make decisions on what they believe can improve the culture of teaching and learning in their schools.

The IQMS provides another striking example of managerialism in education. "It is a performance measurement strategy designed to enhance the quality of education in our schools, but it is framed by the discourses of the private sector: accountability, performance measurement, performance criteria, financial rewards, incentives" (Rabichund and Steyn 2014, 349). Due to its unabashedly managerialist orientation this policy is likely to have the unintended effect of colonising school cultures and encouraging the development of a culture of compliance, rather than a culture of continuous improvement. Thus, instead of genuinely improving their professional activities, teachers will develop strategies of "beating the system" by conforming in a perfunctory and unreflective manner to its requirements.

The authors support intervention in the form of financial and human resources from the central authorities for under-resourced schools for change to occur and succeed in them. We however believe that the need for whole school improvement should originate from the school communities themselves and not from externally imposed school improvement initiatives such as the IQMS for the desired effect of improving the quality of education for all to be attained. These school communities, no matter how poor they are, know very well what they need and what would work for their children's education to improve.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL PRINCIPALS

The introduction of new policies which are aligned to the New Public Management in the South African education system meant that there was a need to move from the traditional and progressive methods of operation to the new or modern models which allow more creativity and flexibility. The new policies brought change to the nature of tasks that are performed by principals and forced a change within the desired skills of school principals in that they should be more creative, innovative, responsive and flexible. The functions and roles of the principal have been transformed to include those of both a leader and a manager. Verger and Curran (2014) believe that the adoption of New Public Management reforms in public schools means a promotion of a managerialist approach to school organisation which implies the concentration of responsibilities in the school principal, thus professionalising and strengthening his or her role. Oldroyd (2003) supports this idea when he says that management and leadership have become synonymous, where management is a subset of leadership.

Nowadays the term leader is also used to refer to any manager because it is difficult to distinguish between the two as they are both appointed to positions of running organisations. To some, school leadership has come to mean that all responsibilities fall on the principal while others see management as having many responsibilities that are distributed to different people forming the school management team (SMT) (Verger and Curran 2014). According to Phaneuf (2007, 3) "a manager is a 'left brain' that uses logic and numbers while the leader who is more sensitive to intuition, more inclined towards innovation and action, is the 'right brain.'"

The New Public Management reforms such as outcomes-based accountability, performance measurement and reporting, school choice, higher standards, and measurement of results have changed the purpose of schooling to focus on tactical learning or teaching for the purpose of producing favourable student achievements (Fusarelli and Johnson 2004, 121). Principals and teachers of public schools are under pressure to acquire new sets of skills and knowledge, and activities associated with the business or corporate world to account for their performance. "They are today working in conditions characterised by increased public scrutiny, more sophisticated techniques ensuring accountability and many strategies measuring learner achievements" (O'Hara et al. 2007, 77). Oldroyd (2003, 63) outlines three types of accountability that are expected from a school leader:

• Administrative accountability-compliance with laws, regulations and mandatory reforms;

• Market accountability-ensuring that the school maintains its results and reputation in order to satisfy its "customers" and to recruit sufficient students; and

• Democratic accountability-responding to the specific needs of the parents and pupils, the local community and to the needs of the state for the next generation of democratic citizens.

Performance reporting in the form of school results that are published in the newspapers and compared with other schools has led to teachers, and sometimes principals, playing dirty when provincial and national standardised tests or examinations are written in order to raise leaners' scores. Schools with good results are known as the "best schools in a competitive consumer market of schooling" (Oldroyd 2003, 52). A best school will always be a first choice for parents who wish for their children to get quality education; it will always have a high learner enrolment, and the teachers will never be threatened with retrenchment.

At the beginning of every year the education district offices take stock of Grade 12 examination results in order "to identify low-performing schools and develop comprehensive school improvement plans" (Fusarelli and Johnson 2004, 121). There is also a feeling that the purpose of identifying under-performing schools and teachers is to "name and shame" them (O'Hara et al. 2007). Principals of such schools have to account for the poor performance and this may affect his or her status of employment. The consequence of the poor performance has been "that parents whose children are attending these low-performing and low quality schools will remove their children" and these schools will lose teachers and the principals may be demoted to a lower level or the school may be placed under direct supervision of a circuit manager (Fusarelli and Johnson 2004, 121).

While the aspects of New Public Management such as teacher appraisal, merit pay, performance outputs and bonuses, promotion or career ladders have raised the level of competition among teachers and schools, the level of leadership and management has been challenged among the principals as they have to deal with teachers who would do anything to get high scores during performance assessment and to improve learner achievement (O'Hara et al. 2007; Oldroyd 2003). On one hand, the principal should be seen applying and complying with the education laws and regulations to prevent any wrongdoing during the processes of teacher performance assessment and learner academic assessment; on the other hand, he or she should steer the school, and support the teachers towards excellence in order to respond to the expectations of the parents and the state and maintain high standards and good results. This calls for the ability and capacity of the school leader to interpret and implement the new policies correctly and to make decisions that will benefit all the stakeholders. As stated in the resistance leadership discussion, the school leader should earn the teachers' trust by involving them in decision-making, develop a supportive culture by promoting professional development and enhance their sense of efficacy (Zimmerman 2006).

CONCLUSION

It is apparent, from the research and literature on school management in South Africa, that besides the quest for international acceptance, the government embraces the New Public Management principles to promote self-managing schools that can take care of their development. However, instead of passing legislation that purports to have general applicability the government should acknowledge the obvious fact that school governance and leadership are context-driven processes.

In fairness to South African public policy makers it must be acknowledged that most of the principles and assumptions underpinning NPM are inherently ambiguous as they do not make a clear distinction between the state as a driver of educational and other social policies on the one hand and the "invisible hand" of the market on the other hand. The latter has been shown globally to be primarily and exclusively concerned with quantifiable outcomes at the expense of inherently values-based and developmental organisational processes.

We all want well-managed and successful schools. But this can only happen in a country where the citizens enjoy a similar socio-economic status. This alerts us to one of the important qualities of policy formulation-that policies tend to favour the interests of the rich and powerful. It is the duty of key government officials such as principals to challenge policies which seem to favour particular social classes. This paper highlights the unintended consequences of the role of a "regulatory state" or an "evaluative state." One of these is the deliberate foregrounding of "results" in the educational system and the related neglect of "processes" and developmental issues.

REFERENCES

Ball, S. J. 2003. "The Teacher's Soul and the Terrors of Performativity." Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 215-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065 [ Links ]

Caldwell, B. J. 2013. "Leadership and Governance in the Self-Transforming School." Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Council of Educational Leaders, Canberra, October 4.

Çetin, S. 2012. "Leadership in Public Sector: A Brief Appraisal." DPUJSS 32 (2): 75-85. [ Links ]

Chang, H. 2010. 23 Things They Don't Tell You about Capitalism. New York: Bloomsbury Press. [ Links ]

Dalin, P. 1978. Limits to Educational Change. London: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ferlie, E., L. Ashburner, L. Fitzgerald, and A. Pettigrew. 2006. The New Public Management in Action. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Fusarelli, L. D., and B. Johnson. 2004. "Educational Governance and the New Public." Public Administration and Management: An Interactive Journal 9 (2): 118-27. [ Links ]

Hambleton, R. 2003. "City Leadership and the New Public Management-A Cross National Analysis." Paper presented to the National Public Management Research Conference, Georgetown University, Washington DC.

Hancock, J. 2011a. "Humanistic Leadership." Accessed June 5, 2015. http://humanisticleadership.com/leadership.html

Hancock, J. 2011b. "Jen Hancock's Handy Humanism Handbook." Accessed June 5, 2015. http://www.jenhancock.com/handyhumanism/

Johannesson, I. A., S. Lindblad, and H. Simola. 2002. "An Inevitable Progress? Educational Restructuring in Finland, Iceland and Sweden at the Turn of the Millennium." Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 46 (3): 325-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383022000005706 [ Links ]

Kan, M. M., and K. W. Parry. 2004. "Identifying Paradox: A Grounded Theory of Leadership in Overcoming Resistance to Change." The Leadership Quarterly, no. 15, 467-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.05.003 [ Links ]

Kowalczyk, P., and J. Jakubczak. 2014. "New Public Management in Education: From School Governance to School Management." Paper presented at the Human Capital without Borders: Knowledge and Learning for Quality of Life; Management, Knowledge and Learning International Conference, Portorož, Slovenia.

Marais, H. 2011. South Africa Pushed to the Limit: The Political Economy of Change. Claremont: University of Cape Town Press. [ Links ]

Maurer, R. 1996. Beyond the Wall of Resistance: Unconventional Strategies that Build Support for Change. Austin: Bard Books. [ Links ]

Mok, K. H. 1999. "The Cost of Managerialism: The Implications for the 'MacDonaldisation' of Higher Education in Hong Kong." Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 21 (1): 117-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080990210109 [ Links ]

Motshekga, A. 2015. "Full Speech by Minister Angie Motshekga on the 2014 Matric Results." SA Breaking News, January 6. Accessed April, 19 2016. http://www.sabreakingnews.co.za/2015/01/06/full-speech-by-minister-angie-motshekga-on-the-2014-matric-results/

Motshekga, A. 2016. "Announcement of the 2015 NSC Examinations Results." South African Government, January 5. Accessed November 12, 2017. https://www.gov.za/speeches/minister-angie-motshekga-announcement-2015-nsc-examinations-results-5-jan-2016-0000

Motsohi, T. 2017. "What Happens before Grade 12 Is Critical to Success." The Mercury, January 10.

Naicker, I. 2005. "A Critical Appraisal of Policy on Educator Post Provisioning in Public Schools with Particular Reference to Secondary Schools in KwaZulu-Natal." PhD dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

O'Flynn, J. 2007. "From New Public Management to Public Value: Paradigmatic Change and Managerial Implications." The Australian Journal of Public Administration 66 (3): 353-66. [ Links ]

O'Hara, J., G. McNamara, R. Boyle, and C. Sullivan. 2007. "Context and Constraints: An Analysis of the Evolution of Evaluation in Ireland with Particular Reference to the Education System." Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Evaluation 4 (7): 75-83. [ Links ]

Oldroyd, D. 2003. "Educational Leadership for Results or for Learning? Contrasting Directions in Times of Transition." Managing Global Transitions: International Research Journal 1 (1): 49-67. [ Links ]

Perruci, G., and S. W. Schwartz. 2002. "Leadership for What? A Humanistic Approach to Leadership Development." Paper presented at the Art of Management and Organisation Conference, King's College, London, September 2-5.

Pfiffner, J. P. 2004. "Traditional Public Administration versus the New Public Management: Accountability versus Efficiency." In Institutionenbildung in Regierung und Verwaltung: Festschriftfur Klaus Konig, edited by A. Benz, H. Siedentopf and K. P. Sommermann, 443-54. Berlin: Duncker & Humbolt. [ Links ]

Phaneuf, M. 2007. "Leadership: Between Humanism and Pragmatism." Accessed April 21, 2015. http://www.infiressources.ca/fer/Depotdocument_anglais/Leadership_Between_Humanism_and_Pragmatism.pdf

Prindle, R. 2012. "Purposeful Resistance Leadership Theory." International Journal of Business and Social Science 3 (15): 9-12. [ Links ]

Rabichund, S., and G. M. Steyn. 2014. "The Contribution of the Integrated Quality Management System to Whole School Development." Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5 (4): 348-58. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n4p348 [ Links ]

Steyn, G. M. 2002. "The Changing Principalship in South African Schools." Accessed March 23, 2017. http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle

Van der Westhuizen, P.C., and A. M. C. Theron. 1996. "Resistance to Change in Educational Organisations." Paper presented at the fifth Quadrennial Research Conference of the British Educational Management and Administration Society, Cambridge University, Cambridge, March 22-27.

Verger, A., and M. Curran. 2014. New Public Management as a Global Education Policy: Its Adoption and Re-Contextualization in a Southern European Setting. London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Walton, E. 2017. "Why Caution Is Called for When Analysing South Africa's Matric Results." The Conversation, January 5. Accessed April 10, 2017. https://theconversation.com/why-caution-is-called-for-when-analysing-south-africas-matric-results-70853\

Wasserman, I. C., P. V. Gallegos, and B. M. Ferdman. 2008. "Dancing with Resistance: Leadership Challenges in Fostering a Culture of Inclusion." In Diversity Resistance in Organizations, edited by K. M. Thomas, 175-202. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Zimmerman, J. 2006. "Why Some Teachers Resist Change and What Principals Can Do About It." NASSP Bulletin 90 (3): 238-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636506291521 [ Links ]