Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.21 n.2 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/1960

ARTICLE

Are you happy now? A fictional narrative exploration of educator experiences in higher education during the time of #FeesMustFall

Marguerite Müller

University of the Free State. mullerm@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In this performative text a narrative arts-based approach is used to explore the connections between educator identity and the current issues arising in the broader South African higher education landscape. Written as a Actional narrative it is an exploration of some of my experiences at the University of the Free State between 2014 and 2016. The post-qualitative, arts-based narrative serves to connect research practice with educator experience in higher education. As the traditional, patriarchal and colonial nature of institutions of higher education is being questioned by student movements like #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall, we have to ask how our research practices are responding to these movements. The idea of knowledge as a process is an important aspect that arts-based research illuminates in relation to social change. In this article I connect the idea of knowledge as process to the idea of pedagogy as a process which ties in with our lived experiences and interactions. As such, this text uses art as a way to illustrate the continual journey and process of moving towards socially just pedagogies. The "Actional" narrative is used as a creative exploration of innovative methodologies in trying to find a way forward into messy and uncertain spaces that characterise the complexity of the current higher education landscape in South Africa.

Keywords: arts-based research; fiction; narrative; social justice; socially just pedagogies; performative text; post-qualitative research

THE WHY

Another site of decolonization is the university classroom. We cannot keep teaching in the way we have always taught. (Mbembe 2015, 6)

Higher education in South Africa has become a site of resistance and questioning the status quo, and as educators working within this space we have an obligation to try and make sense of what is happening around us. I am writing from this volatile and uncertain space where we are urged to re-think the ways in which we teach, and by extension the ways in which we do research. As part of the broader project of decolonisation we need to consider how our research practices connect to spaces of resistance and questioning, and to pedagogy. Zembylas (2007) approaches pedagogy as relational encounters between people that make possibilities for growth possible. In line with this approach I do not view pedagogy as necessarily that which happens in the classroom (although it is also that), but as engagements, encounters and relationships between people that are linked to education and as such narrowly intertwined with educator identity and experience. Pedagogy as such cannot be viewed as a stable entity, but as something that continually evolves through the social practices in relational encounters and the meanings individuals construct from those practices (Van Manen 1991). The performative narrative is thus an attempt to help me make connections between my educator identity and the unpredictable and rapidly changing landscape of higher education in South Africa. In doing this, I am looking to that which Patti Lather and Elizabeth St. Pierre (2013) have called the "post-qualitative" movement, where researchers attempt to "imagine and accomplish an inquiry that might produce different knowledge and produce knowledge differently" (Honan and Bright 2016, 731). This speaks to our current situation in which the traditional patriarchal and colonial nature of academia and institutions of higher education is being questioned by student movements like #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall. In response to this we have to ask how our research practices are aligned to the need for decolonisation in higher education in South Africa. As such, I present this article as a fictional narrative exploration of some of my experiences at the University of the Free State (UFS) between 2014 and 2016. In writing this "story" I followed an arts-based post-qualitative approach which is informed by arts-based, collaborative, self-study, and narrative research methods. The following question guided my writing: How can innovative methodologies (e.g. postqualitative research methodologies) be used to study the various complexities emerging in designing and enacting socially just pedagogies, as well as their implications for higher education? This text should thus be read as a creative exploration of innovative methodologies as we search for a way forward into these messy and uncertain spaces that characterise the complex higher education landscape. The text is not intended to provide any definite answers, but rather aims to open up dialogue and conversation around issues of decolonisation and its entanglement with educator identity and research methodologies.

THE HOW

I purposefully wrote this piece as a "performative text." According to de Oliveira Andreotti (2016, 80),

"performative" texts are very different from texts that claim to represent something literally. As an expression of an aesthetic force the text has a life of its own and is out of my control-in the artistic sense, I cannot claim responsibility for what it does or even where it comes from. My experience with this force is that it intends to "touch" each reader differently, in order to bring forward something needing to surface and to become visible.

In this performative piece I use an arts-based narrative approach to explore the connections between educator identity and the issues arising in the broader South African higher education landscape. The sometimes "fictional" narrative is intended as a "window" into a complex space in which complex beings deal with complex issues. The narrative is partially woven out of the research material that I gathered for my PhD thesis around issues of change and transformation at the UFS. While working with narrative and arts-based methodologies I became interested in the use of fiction writing in/as research (Clough 2002, 1999; Leavy 2013). As such, I developed a character called Daisy as a research tool to explore the current higher education landscape. I use "her" to write myself into new research spaces where I can explore new ways of knowing ... and becoming different (Kumashiro 2002; Lather and St. Pierre 2013; Richardson and St. Pierre 2005). I also make use of the character called Daisy to position myself as an embodied academic as I feel my way through the current challenges and tensions in higher education. While the story is told from Daisy's perspective, she is constantly informed and influenced by other characters. As such, her identity sometimes moves beyond the sum of her identity "categories" to become more fluid in her interactions with others, while at other times she is limited by her social identity to a certain understanding or viewpoint. In this way, the narrative explores the very real tension that academics might feel between their social identity and professional identity in the higher education context. The tension is illustrated by Daisy's interactions with other characters who were "born" from a collaborative methodology that I followed for my PhD. In this collaborative research method I encouraged research participants to create their own characters whose stories then merged with that of Daisy to make a co-created composite narrative. The characters in this narrative were therefore sculpted from the contributions of research participants who shared their own stories using character portraits. The use of an arts-based methodology is thus purposefully connected to a theme of anti-oppressive change as it engages not only with different ways of being, but also different ways of learning and knowing. The work is situated in a poststructuralist framework in which oppression is read as intersectional, situated and multiple (Kumashiro 2000). According to Kumashiro (2000), critical theory is useful to name oppression and to become critically conscious, however we "need to make more use of poststructural perspectives in order to address the multiplicity and situatedness of oppression and the complexities of teaching and learning" (Kumashiro 2000, 25). In being critical of critical pedagogy Kumashiro moves to a poststructuralist conceptualisation of oppression that centres on notions of discourse and citation so that oppression can be understood as "the citing of harmful discourses and the repetition of harmful histories" (Kumashiro 2000, 40). Oppression can thus be challenged through disrupting, reworking and supplementation, rather than repetition. We might desire learning only that which reveals we are good but we must overcome this desire to achieve change and difference. As educators we work in in-between spaces of uncertainty, discomfort and self-doubt, and our experiences are often disruptive, interrupted, and messy. In this article, I purposefully avoid any prescriptive recipes for socially just practice by looking at creative avenues of exploring the messy and uncertain avenues of identity in order to become different.

THE WHO

I recently went to a photographic exhibition by Abrie Fourie (28 October - 4 November 2016) entitled "Oblique: The So-Called Fruits of Lives" at the Johannes Stegmann Gallery. The artist explores the relationship between narrative and photographs and how images have the potential to unlock memories. Upon entering the exhibition space, I was met by the following quote:

Is it fair to weave fictions out of the lives of real people? How else are fictions made? All fiction is the factual refracted. Is the degree of refraction, that is, the extent to which the factual is distorted, the mark of accomplishment? (Ivan Vladislavic 2011)

I stopped, read, and re-read this quote, asking myself if I have been weaving fictions out of the lives of real people. I think the answer is yes; this is exactly what I have been doing. Perhaps all fictional characters are created in this way. Pablo Picasso (who was a real person but has been fictionalised in many ways) is quoted as saying that "[w]e all know that Art is not the truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies" (Chipp 1968, 246). Talking about the genre of children's literature Barnett (2014) observes that "[y]ou've got truth and lies and then the space in the middle-that's art. You can call that space art, or fiction or wonder." Barnett (2014) points to the fact that we can have real feelings about fictional characters, and that art is a secret door that can take us into a fictional world. He argues that it is possible for fiction to escape into reality, and to become "real." Consider for example that people will journey to visit the house of Sherlock Holmes at 221B Baker Street even though they know he is a fictional character. Leavy (2009, 48) also explores the blurred lines between fact and fiction in academic research and states that:

Historically, both academic research and public perception have been informed by the fiction-nonfiction dualism that inherently legitimizes the notion of a discernible "truth" while implying fiction to be its polar opposite; however, it is now widely accepted in academia that there are "truths" to be found in fiction, and nonfiction also draws on aspects of fiction in its rendering of social reality. In other words, the polarization of "fiction" and "nonfiction" is misleading and qualitative social science research is moving beyond this false dichotomy.

In the narrative I present the characters are purely fictional, yet some of the dialogue between them are based on real conversations, real interviews and real experiences. I brought them into existence with the specific purpose of creating a performative text, which speaks to some of my personal experiences in the higher education landscape at the UFS. For example, Daisy's experiences are based on my own and she functions as self-portrait or alter-ego. I use her to write myself into new research spaces where I can explore new ways of knowing and becoming. But she is not alone, her thoughts and actions are shaped by the other characters in this story. Below I have allowed the characters to briefly introduce themselves:

Daisy: I live and work on the UFS Bloemfontein campus and my story is woven out of the experiences I have in this space. I am a white South African woman and old enough to have seen the transition from apartheid to democracy. I have celebrated the rainbow nation and had to come to terms with the reality of how that rainbow was never real. Now I am living, teaching and mostly trying to make sense of my own identity in a very complex space.

Alice: I was one of the first Indian people to be employed by this university in an academic capacity. And at the time Bloemfontein was a very difficult place, because I think I could count the number of Indian people in Bloemfontein on one hand. The first thing people would ask me was: are you Muslim? I'd hear these silly questions and stuff like that we eat with our fingers. That we eat curry for breakfast, lunch and supper ... I mean really! My first experiences were very difficult, but eventually when the colleagues and the students came to know me, you know as a person, rather than as "this lecturer," then they approached me differently.

Mick: I am a lecturer at UFS. I am a young black man, and sometimes I am so conscious of my identity in this space. I think my social identity is connected to my work in so many ways. My research and teaching is mostly around issues of social justice. My goal in life is to work towards a society which is equal, and fair, so transformation is part of that huge agenda. I'm trying to make society a place where there's equality and there's less pain and there's less hurt and there's less discrimination. But it is heavily emotionally taxing.

Celine: I have a good job at the university. I support my extended family on the salary that I earn. They call it "black tax." I don't mind it though as I know the sacrifices my mother had to make to get me through university. She was a single mom and had to give everything to help me get a degree, which I did against all odds. In all of my family I am the only one with a degree, with a car, and with a permanent job. I have worked very hard to get where I am, but I also know my family made big sacrifices to get me here.

TJ: I am an activist and leader in the student community. My parents were both actively involved in the struggle against apartheid. They both passed away when I was in high school. My older brother has been helping me financially to make my way through university. That was until he got retrenched last year. I am almost done with my Law degree, but unsure where I will get the finances to pay the outstanding debt I have accumulated. I feel angry and cheated. That which my parents fought for is still beyond our reach.

Tumi: I am an education student. I hope to teach high school mathematics one day. I love mathematics, because it is something I can control and understand. My parents are both teachers. We are four children in the house and currently three of us are at university. This is putting enormous financial strain on my parents. I guess you could say I come from the "missing middle" class. As my parents have work I do not qualify for NSFAS, but at the same time they do not really have the finances to pay for my education. Every year we scrape by with loans and odd jobs, but sometimes I just don't have any money left to buy food, and I feel bad to ask my parents for more money, as I know they are also struggling.

Celeste: I am an accounting student. My parents are both civil servants. I grew up in a very protected and privileged environment. I am the only daughter and my parents have very high expectations of me. I feel a lot of pressure to prove myself and live up to their expectations.

Emilia: I am Polish, currently living and working in South Africa. People make a lot of assumptions about me because I am European, but I often realise they know very little about Poland. I hope to go back home soon, but I am struggling to get work in higher education in Poland.

School girl: I play a minor role in this story. I am a white girl in South Africa. I go to a good school. I have questions, but sometimes I feel a little shy or scared to ask them. I often feel awkward in new situations. I do not have a sense of belonging. I mostly feel alienated. But I try to do my school work as best I can, and I get good marks.

PAST: I am the personification of Daisy's memory. I appear as a rat who lives on the UFS campus. I like to remind her of things that have happened that are somehow connected or relevant to her story.

FUTURE: I am a bird who flies in and out of this story. I speak of possibilities and realities as I flutter between past, present and future. I prefer to speak in verse, and song.

THE WHERE

The setting of the story is the UFS Bloemfontein campus. The space must be understood as dynamic and changing as the #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall movements play out on campus. The narrative unfolds over a period of one year from around September 2015 to October 2016. Most of the images that are intertwined with the story are photographs I took between September 2015 and October 2016 on the campus. Some of the images are borrowed from other sources and used to visually enhance the storyline.

THE WHAT

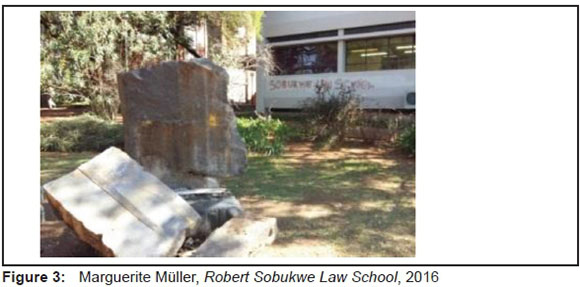

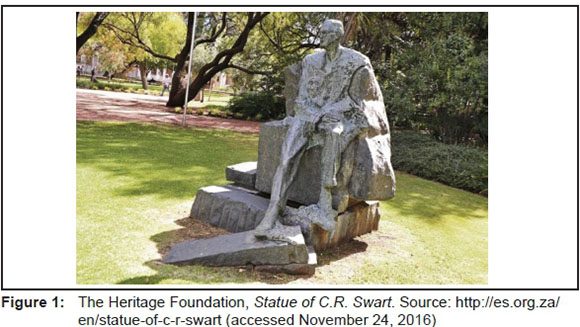

Daisy is walking along her usual route on the Bloemfontein campus of the University of the Free State. This is where she works and lives. At the monumental stone figure of C. R. Swart she stops to rest. She is four months pregnant, and gets out of breath easily. As she catches her breath she looks up at Swart, but he is staring off coldly into the distance (Figure 1).

PAST: Do you remember the time when the statue of Swart was wrapped in pink plastic? It was part of the art project called "Plastic Histories" (Figure 2). The intention was to get the public to evaluate public monuments in their historical context and revalue them from alternative perspectives and furthermore, to acknowledge the contribution of women from all races, communities and sexual orientations to the grand narrative of a post-apartheid South Africa.

Daisy remembers it well. It was perhaps the first time she even noticed the Swart statue. Now everyone is watching him, wondering about his future. Just yesterday Rhodes was taken down at UCT. Rhodes did fall, but will Swart fall too? Her thoughts are interrupted by a youthful voice behind her.

School girl: Excuse me Miss, can I ask your opinion? I am doing a school project about the vandalising of statues and I was hoping you would give me your opinion ...

She looks around to see a girl of around fourteen in school uniform. She is armed with a clipboard and friendly smile. As Daisy tries to answer the girl's question she notices a group of black female UFS students who have gathered around the Swart statue. They take out their smartphones and start taking selfies with the solid block of the Swart statue. One student is sitting on his lap, kissing his cheek, and putting her arms around his neck, while others snap away, pulling faces and laughing. They are obviously mocking Swart.

Daisy: Maybe you should ask the students' opinion rather than mine.

The girl looks uncertain, her big eyes a little fearful. She turns and walks away from Daisy and the students. Her ponytail swinging cheerfully behind her.

*

It is towards the end of 2015 and the #FeesMustFall movement is sweeping through the South African higher education landscape. Daisy is having a cup of coffee with Alice, Mick, and Celine.

Daisy: How was your class?

Alice: Mostly the students just wanted to talk about this #FeesMustFall thing.

Daisy: I can imagine. What are they saying? And what do you think about everything that's been happening?

Alice: Look I do agree with the whole thing about the fees, because I do believe higher education should be accessible to students who have the potential . because there are many students out there who might not have ... who can't come because they can't afford it, they don't have access to this space, but I also think that I was disappointed with the whole thing . it became like a black people's fight and students' fight ... like people were saying "these students shouldn't be ..." You know? And not realising that it in fact influences every one of us ...

Daisy: You mean white people were saying that ... ?

Alice: Ja, and like my tutor saying she thinks it's quite pathetic and I said to her well it's easy to speak if you come from this position of privilege and it's a bit more difficult for somebody who doesn't-and have to try and get into this space ... I mean we can't deny the fact that even though democracy is here it doesn't necessarily mean that racism has gone, and how we see and engage with one another . uhm, but I must say even when the students were talking about, you know with the #FeesMustFall thing, and the students were talking and they were saying that-the black students in particular were saying-that the lecturers were not there, they were not visible really I mean ... I mean I went on the Thursday afternoon and then I went on Friday and there was nothing happening, it was over, but we should have been there from the beginning to show that this is also our concern.

Celine: ... I think they want things for free, they are not willing to work hard. I am not against, you know, free education, because I saw how my own mother struggled, based on my fees, but I think there should be ... also be a sense of accountability. 'Cause when they wanted to strike here I said to them, before anything I am an employee of the university . my opinion at this point does not count, because the university pays me . and then you know I was seen as a traitor, like "You should be supporting us," and I said "Who said I am not supporting you? It is just that my first and foremost obligation is to the university and what I think of what you are doing is irrelevant." You know? ... For me it is also the group that came here to strike, some of them are just in it for their own egos ... like one guy I know him, he did not pass his first semester and he had a bursary and he lost that bursary. So why didn't he study to keep that bursary? And now here he is striking for free education?!

Mick: Hhm, but I think you must see the bigger picture here, look past the individual students ... first we had #RhodesMustFall ... and then #FeesMustFall ... I was excited for #FeesMustFall, I was, I was really ... and I was there protesting with the students 'cause I felt that students were standing up for an injustice and I knew so many students who started with me and just did one year and then could never finish ... I was also slightly worried or disturbed at the fact that what I saw from our university there was very little support of #FeesMustFall from white Afrikaans students . and then it went to social media and some people were very vocal about it must stop . these "hooligans" must stop . and so it brought out a whole lot of this .

Daisy: Why do you think the white students were absent from that space?

Mick: I think one of the reasons is possibly because some of them they are not affected by it because the parents can be able to afford fees . the other one is . uhm . protesting is something that is seen probably as disruptive ... hooliganish . and so it is portrayed in that sense and it is probably something people want to distance themselves from . but I think most of it is being sheltered so much that you just can't identify with other people, 'cause I think if they truly did understand the pain and the suffering that goes on . I think those students were the ones who did support, because if you can't identify with what the struggle is you can't be there in solidarity.

*

FUTURE:

Outsourcing must end Violent clash at Shimla Park Campus shutdown Anger boiling over

Spilling onto the green lawn

Racial tension

Sticks

Spray paint

Running

Fear

Police! Police! Police!

...

Early morning quiet autunm air

strolling past the same spot Daisy stops

where CR Swart is lying

motionless in the pond

Staring up at the crisp Bloemfontein blue

Dry leaves rustle in the trees

Shhhh

The stone slab where he used to rest

Still erect

like a grave stone

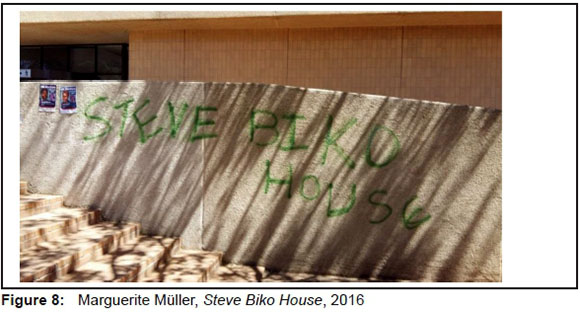

Someone is painting over the fresh graffiti on a nearby wall SOBUKWE LAW

SCHOOL is slowly disappearing

Under a new coat of paint

Renaming

Erasing

Claiming

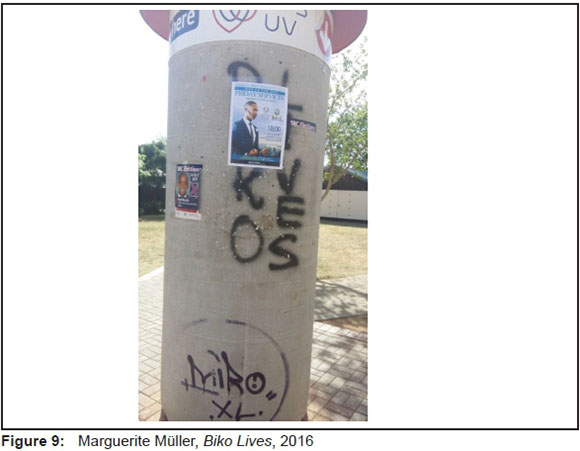

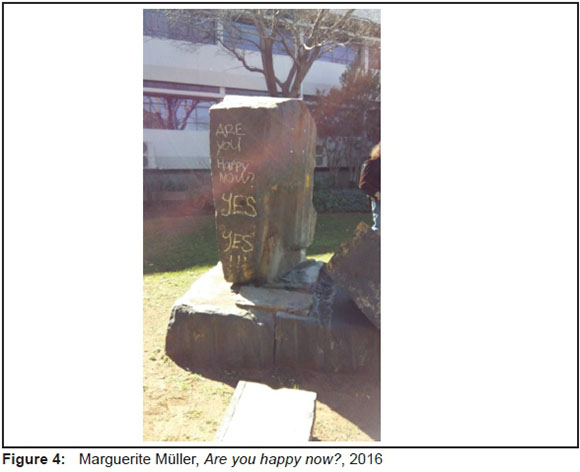

April 2016 Daisy strolls past the place where Swart used to be. "Are you happy now?" (Figure 4) is chalked out in white on the stone where Swart used to rest. And the answer comes in a sunny yellow: "Yes Yes!!!" Her little baby girl is asleep against her chest and Daisy can feel the small heartbeat against her own. She is thinking about the space, and how it has changed since last year. Thinking of the conversations in chalk. She walks on. Names are imprinted on the Plane trees, on the walls, on the concrete path ... Biko, Sobukwe ... (Figures 5 and 6) The campus is suddenly "tattooed" with these names. Names that were once absent and silent. But never forgotten. Now calling loudly from beyond the grave.

It is October 2016 and Daisy is on her way to a reading group that meets once every two weeks at the university coffee shop. Their reading for that week is Achille Mbembe's "Decolonising Knowledge and the Question of the Archive." As she walks along she downloads the PDF on her phone and starts reading: "Twenty years after freedom, we have now fully entered what looks like a negative moment. This is a moment most African postcolonial societies have experienced. Like theirs in the late 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, ours is gray and almost murky. It lacks clarity" (Mbembe 2015, 1). ... Negative moment ... grey and murky ... lacks clarity? Her thoughts are suddenly interrupted by a voice just behind her.

TJ: Hey ma'am, how are you?

Daisy: I'm alright. Just wondering what is going to happen next. Minister Blade is making his announcement about fee increments today. Are you guys planning to strike?

TJ: You must understand we do not want to strike. But if it is anything more than 0% we will strike. You must understand, it is not what we want, it is hard work to strike. But this is our generation's struggle ... we have to get free education. We have to.

Daisy: I understand that, but surely ... where will the money come from? The university cannot give what you ask for . will the government?

TJ: Frankly that is not our problem ... where they find the money ... but this is our task. Daisy: Are we looking at a peaceful protest?

TJ: Fanon says that "Decolonisation is always a violent phenomenon ... the replacing of a certain species of men by another species of men" (Fanon 1965, 35).

Daisy: Men?

But she has lost TJ's attention. He is waving goodbye to her as he walks on to join some friends up ahead. Daisy returns her focus to Mbembe: "A negative moment is a moment when new antagonisms emerge while old ones remain unresolved" (Mbembe 2015, 2). And further: "In order to set our institutions firmly on the path of future knowledges, we need to reinvent a classroom without walls in which we are all co-learners" (Mbembe 2015, 6). She looks up from her reading. A bird is singing somewhere in a nearby tree. It is the song of FUTURE.

FUTURE:

Sobukwe is spelled out in green

Here in the graveyard of broken dreams

Revolutionary hopes

dusty disappointments

here in the cemetery of the remembrance

The past is etched out on every possible surface

The winds of change

blowing through the lane

of outlandish Plane Trees

Biko, Biko, B I K O

Biko lives

She takes pictures on her smartphone as she walks along. PAST is running after her.

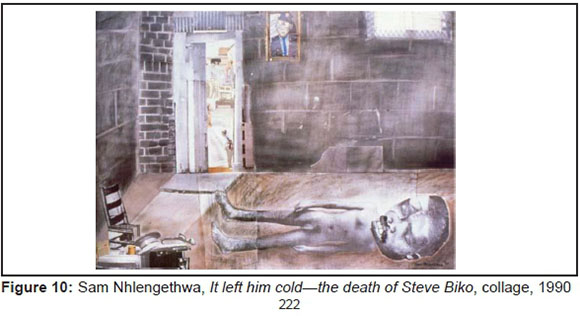

PAST: Do you remember that time you were teaching the Grade 11 Art Class about South African resistance art? You were discussing a collage about the death of Steve Biko.

Daisy's memory drifts back to where she is standing in a high school classroom. Her memory smells of pencil shavings and cleaning detergent. "I hate white people! I hate white people!" a student named Veronica is shouting as she storms out of the classroom. Daisy is left with a group of wide-eyed Grade 11 learners-and a very uncomfortable silence. She feels ... lost, frustrated, blamed, guilty, angry, defeated ... tired.

*

Daisy arrives at the reading group. She is eager to contribute today. Eager to voice some of her thoughts-to write it with spray-paint on a wall or shout it through a megaphone. She feels like a pot about to boil over.

Daisy: In this article Mbembe speaks of the classroom without walls . the interesting thing is that the campus is becoming like that now. On my way here I was confronted by the names of Biko, Sobukwe and others ... I was forced to contemplate the empty space where C. R. Swart used to sit ... his absence makes him more "present" in a way. Before I could ignore him, but now I have to think about him and what he did, the choices he made, the role he played . in a way the tables are turned . the students are teaching us-look at what we have to say . here it is in your face ... we will spray-paint-spell it out for you ... BIKO, SOBUKWE ... only now do I wonder ... who was Robert Sobukwe anyway? ... Oh ... and how did he feel all those years in solitary confinement? It is like we are swimming in this sea now ... this sea of uncertainty ... re-learning . unlearning . we cannot take things for granted anymore.

Alice: We cannot do things the way we used to . We cannot teach in the ways we used to teach. We are really forced out of our comfort zones and confronted with our own complacency . our mini Oxford or Cambridge coming apart at the seams . and something else is born . but what? What next? That is what we are all trying to understand.

Mick: Mbembe says: "The university as we knew it is dead" (Mbembe 2015, 20).

Daisy: "Dead?"

The SILENCE is broken by the beep beep beep as a WhatsApp message comes through. It is a picture shared by a colleague from Rhodes University:

FUTURE:

What is born from the ashes of these flames?

From this rage?

Who will turn the page?

Celine takes Daisy's phone to look at the image of ashes and flames. She scrolls down to look at some of the other images preceding that one of a burnt down building.

Celine: You know Daisy, it's kind of funny that you only have pictures of babies and protests on your phone.

She gets to her on-campus apartment. Her little baby girl reaches out her arms to be picked up. With the baby on the hip she stands by her window. TJ and Tumi walk past. One with a megaphone and one with a sjambok.

FUTURE:

A strike is coming

That night filled with singing

Protest songs

She doesn't understand the words

But the message is clear:

Come out, come out, join our cause

In the morning WhatsApp messages come in one after the other. She is trying to feed the baby with one hand as she opens the messages. Mashed sweet potato flies everywhere. She wipes the screen of the phone to read.

There is dust in the air. No rain. Just dust and wind.

FUTURE:

Elsewhere ...

I think I want to be

Should I get out of here?

And go . where?

The campus has become a waiting place. Management is meeting with the students. Beebeebeebeebeep ... Another message, and another and another ...

She is reading the last of the messages when there is a knock on her door. A few students are gathered in her doorway, framed by the dim morning light.

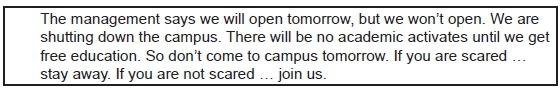

Celeste: Is this true? Will all UFS campuses be closed until after the semester? Do you know if it's true? I think this is a fake message.

Daisy: The university's official communication says we are open tomorrow.

Celeste: Yes, we thought so-look "will" is spelled wrong in that message-the university won't spell "will" wrong, would they? But will the university be open tomorrow? I got a voice message that is being circulated-listen to this:

Celeste: So the message might be true?

Daisy: I really don't know.

FUTURE:

But who is writing the truth now?

Who is creating a new truth?

Our augmented reality

The "fake" message becomes TRUE

As the university will not open again until after the semester break

*

While the October 2016 protests are on-going Alice, Mick and Celine meet in Daisy's apartment for a cup of tea.

Daisy: I am struggling to sleep, because at night the students are singing outside-struggle songs I think.

Celine: Why these songs?

Daisy: And why always the men leading the song?

Mick: Go read ... educate yourself ... lyoooooooooh Solomon, commemorates the life of Solomon Mahlangu, an MK militant who died at the hands of the apartheid government at the age of 22 ... he said: "Tell my people that I love them and they must continue the fight, my blood will nourish the tree that will bear the fruits of freedom, aluta continua." This song gives courage to each comrade in the struggle (Mati 2016) ... so it is perhaps not surprising that the men lead this song.

Alice: Remember our reading by Mbembe? He said that "[a]s Fanon intimated, they see no contradiction between wanting to topple white supremacy and being anti-racist while succumbing to the sirens of isolationism and national-chauvinism" (Mbembe 2015, 1).

Celine: And yet we are seeing a female presence in the leadership of these protests . on the news anyway. Here on campus I'm not so sure, it seems to be mostly guys leading.

Daisy: We have a lot to think about. I am learning a lot. In a way it is a very educational experience for us, but also for the students. It is interesting to see how the students are organising themselves. Taking charge, writing arguments, and counter arguments .

There is a sudden noise outside. Students running and screaming. Police running after them, catching them, arresting them. Students retaliate-throwing stones and bottles at the massive police vehicles, hippos and water cannon. She closes the door-trying to escape this battlefield. As she does this she sees Tumi and TJ run past and overhears the tail-end of a hurried conversation between them.

Tumi: This is getting serious. Are you done now?

TJ: We will never be done.

She closes the door.

Celine: What is going on outside?

Daisy: Students and police playing cat and mouse.

Mick: Why don't you go out and see for yourself Celine, come out of your splendid isolation.

Alice: Don't be ridiculous Mick, she might get a rock to the head, or she might be arrested. She looks like a student and she is black. You know they only arrest black students.

*

The next day the campus is eerily quiet and no one seems to go outside much. She sees a lone protester of small built walking with a stick. All on his own . Did he lose the group? Is he coming for a bathroom break? He looks so vulnerable. So far removed from the images playing out on her television screen, and in the newspapers. She goes off campus to Pick & Pay to do her groceries. In the que at the checkout she stands behind a middle-aged woman holding up the local Afrikaans newspaper. The front page is covered with photos of student protests sweeping the country. "These students are crazy, hey? They don't want to study. Everything is burnt down now ... I hope they are happy. What a mess!" The women is saying this out loud, sort of in her direction as if she is looking for agreement. But Daisy is looking down at the patterns on the floor.

FUTURE:

Feeling unsettled

The campus like a graveyard.

The usual cheerful sounds of students

Are gone

No one is jogging

No one is playing a friendly game of soccer No one is flirting Or laughing

Or sitting around in the sun

Everyone is inside

Posting

Checking

Fretting

Stressing

What's next?

The waiting place ...

Students marching in the night

Sometimes silent

Sometimes singing

Hear our voices

Hear our plea

In the morning she is woken by the sound of helicopters circling Students running

Police is coming

Grabbing

Catching

Arresting

In the van they go

Hearts pounding

Are these criminals?

Are they children?

Hear our voices ...

*

They are almost alone inside the campus coffee shop. Alice's friend, Emelia, is joining them today.

Daisy: No I cannot take this anymore. I am finding a new job.

Alice: Shall we just go work for private institutions? Will that make us sell-outs?

Celine: What if we don't get a pay raise? If we don't have a job in one year's time?

Mick: There is no revolution without sacrifice. You are all just thinking of yourselves.

Celine: But it is so difficult to see where this is all going. Like, what role must we play?

Emelia: In Poland we have free education. I would never have been able to study if we didn't, my parents simply didn't have such money. But free education doesn't mean you will get a job. You might have a PhD and still be serving coffee in a café, because that is all there is to do.

Daisy: In his latest article Mbembe warns about the effect that the shutdown of public universities will have on the poor. If universities become increasingly virtual, will it not disadvantage students with no internet access, or if private universities start moving in to scoop up the academics and students who can afford to pay ... "If we keep subscribing to their [public universities] repeated shutdown many will start wondering whether they are really that important. Many will realise that we can indeed close them, and nothing apparently happens. Things do not fall apart. People simply move on" (Mbembe 2015).

Alice: So I suppose the question is when it is our time to move on?

*

Leaving the coffee shop Daisy is feeling depressed. She runs into Tumi and TJ on their way back from Steers.

TJ: This campus is getting empty. Everyone is going home.

Tumi: It's getting lonely here. Almost all of our friends have gone. No one seems to think there will be classes again this year ... maybe exams ... I just hope we can finish the year.

Daisy: Where is Celeste? I haven't seen her for a few weeks now. Did she also go home?

Tumi: She left. But because of the other reason, not the protest.

Daisy: What other reason?

Tumi: She has a little package on the way.

Daisy: She is pregnant?

Tumi: Yes. Her family is very disappointed. I don't know what she was thinking ... anyway I'm just going home now, I need time to think. I've been protesting and I got so involved in that . Now I need time to think . I must go home.

TJ: I'm staying. If the university opens we will just shut it down ... Even if we have to shut it for three years; until we have free education ... If we need to implode the economy ...

With TJ's words still ringing in her ears she walks past a tree with "Mugabe" (Figure 13) written on it:

PAST: Remember the time when you were teaching an academic literacy class and you asked the students to give examples of people they regard as being intelligent and to explain why they thought so. One student gave Robert Mugabe as an example, explaining that he (Mugabe) succeeded in chasing white people from his country. Remember that?

You felt confused. Worried? Threatened? Afraid?

*

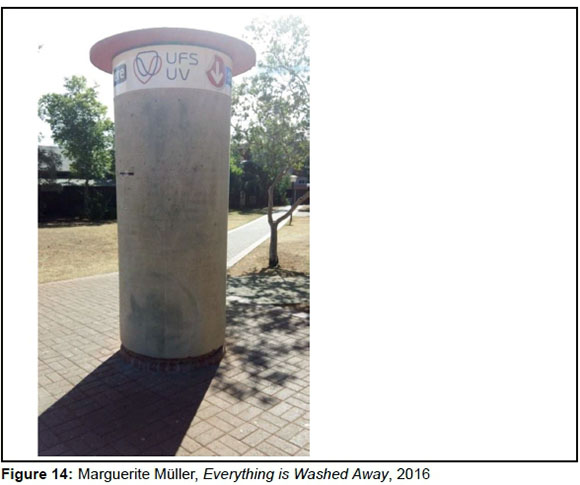

The campus is dead. There won't be classes again this year. There are no students. Only a few police officers sitting around. Looking bored. Their riot gear stacked against a nearby tree. The graffiti is being washed away, and painted over, leaving bare, scrubbed surfaces (Figure 14) like unhealed wounds all over campus.

FUTURE:

Empty spaces

Neutral spaces

Quiet spaces

Waiting spaces

*

On Facebook an old friend asks Daisy's opinion about what is going on with the fees protests. She writes:

My take on what is happening is that we are now at a point where all of us who work in higher education are forced to rethink and re-evaluate the very core of our calling. On a daily basis we are forced into more honest and open engagement with our students, our own identity in this space, and the urgent need for change which we must help establish. The unsettled and uncomfortable landscape in which we now find ourselves might be the catalyst for new and creative approaches to higher education that we so desperately need.

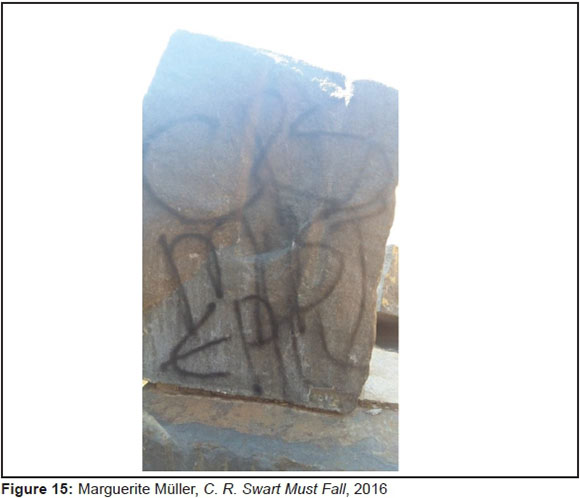

This is her public answer. She really believes it to be true, yet inside she feels less optimistic. She is uncertain and scared. She goes back to the spot where the story began. There is a new message now (Figure 15).

FUTURE:

CR Swart Must Fall

Didn't he fall already?

Guess not

Are you happy now?

Is washed away By rain

or human hands

Who knows?

Are we happy now?

Are we?

Are we? Daisy wonders, as she walks away over the early green summer grass, under blue Bloemfontein skies.

THE SO WHAT?

The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear. (Gramsci cited in Cohen 2013, 1)

This story exists in an in-between space. A waiting space. Something is dead and something is yet to be born. The text is therefore sculpted from feeling and emotion and serves as an expression of experiences and observations. I purposefully approached this text as a work of art in response to the current "crises" in higher education in South Africa. I am writing from a context where there is a strong call for decolonisation, which underscores a need for academic texts that break away from post-positivist conventions. The text is influenced by feminist and queer theory, experientially and emotionally informed, and the choice of an arts-based methodology is purposeful in order to make it accessible to a non-academic audience. It is therefore underscored by a move towards a more feminine approach to writing that does not undermine scientific rigour, but at the same time does not try to emulate a masculine, objective approach to research. As such, the story engages with intersecting issues in higher education in which the traditional patriarchal and colonial nature of academia and institutions of higher education is being questioned by student movements like #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall. The story is not about gender specifically or exclusively, and yet gender cannot be separated from socially just pedagogies. The bodily and cognitive experiences of womanhood and motherhood have an influence on some of the characters including the author. When there are protests on campus, we do not suddenly stop being mothers or being pregnant. As such, I use idea of "pregnancy" to comment on an institutional culture which works to privilege male bodies. Pregnancy serves to illustrate a female embodiment in a traditionally male space. From a metaphorical point of view the idea of "birth" also ties in with what is happening in higher education at the moment where there is a call for renewal and "rebirth."

At first, the uncertainty and messiness of arts-based research might be uncomfortable for those of us who were educated in a post-positivist tradition and probably "prefer our knowledge solid and our data hard. It makes for a firm foundation, a secure place on which to stand. Knowledge as a process, a temporary state, is scary to many" (Eisner 1997, 7). This article is an approach to socially just pedagogy as a process (both inside and outside the classroom) which informs our actions (both inside and outside the classroom). The narrative thus shows the journey (or process) of various role-players in the space as they engage with contextual issues in the current South African higher education landscape. The multiple characters I use are based on "real" interviews with "real" people and reworked into a fictional narrative to illustrate the complexity and messiness of the space through the "noise" of multiple voices. Each character brings a different story with them, and the stories all collide as they meet in the same space. This "collision" creates new interpretations or possibilities. The story does not pretend to be neutral or objective in any way but rather functions as a "performance" or "text" with which we can engage when discussing socially just pedagogy as a (often flawed) process. For example, when talking about the #FeesMustFall of 2015, Alice says "but we should have been there from the beginning to show that this is also our concern." Alice's words illustrate the us/them binary tension between us (academics) and them (students), which also comes out in some of the other comments made by characters in the story. It serves to illustrate the tension that might exist between the students and the academics in trying to negotiate our ever-changing roles and power relations in the higher education landscape. Consequently, the story aims to provide a text for the reader to engage with and "questions" the "flaws," "uncertainties" and the sometimes problematic reasoning of the characters in the story. In this way the article aims to show how innovative methodologies (e.g. post-qualitative research methodologies) can be used to study the various complexities emerging in designing and enacting socially just pedagogies, as well as their implications for higher education.

The idea of pedagogy as a process also ties in with knowledge as a process, which is an important aspect that arts-based research illuminates in relation to social change. As such, this text uses art as a way to illustrate the continual journey and process of moving towards socially just pedagogies. It is presented as an exploration of how innovative methodologies can be used to study the various complexities emerging in designing and enacting socially just pedagogies. The "performative" text must be understood as organic; it has a life of its own. The so what? will therefore be different for each reader. The artistic force "intends to 'touch' each reader differently, in order to bring forward something needing to surface and to become visible" (de Oliveira Andreotti 2016, 80). Thus, my aim with this fictional narrative is to explore how we build knowledge in the current higher education context in South Africa through our experiences, as well as our creative engagement with these experiences.

REFERENCES

Barnett, M. 2014. "Why a Good Book Is a Secret Door." TED video, 16:59. https://www.ted.com/talks/mac_barnett_why_a_good_book_is_a_secret_ door?language=en (accessed December 1, 2016).

Chipp, H. B. 1968. The Theories of Modern Art. A Source Book by Artists and Critics. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Clough, P. 1999. "Crises of Schooling and the 'Crisis of Representation': The Story of Rob." Qualitative Inquiry 5 (3): 428-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049900500308 [ Links ]

Clough, P. 2002. Narratives and Fictions in Educational Research. Philadelphia: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Cohen, R. 2013. "A Dangerous Interregnum." The New York Times, November 18. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/19/opinion/cohen-a-dangerous-interregnum.html (accessed November 20, 2016).

De Oliveira Andreotti, V. 2016. "(Re)Imagining Education as an Un-Coercive Re-Arrangement of Desires." Other Education: The Journal of Educational Alternatives 5 (1): 79-88. [ Links ]

Eisner, E. W. 1997. "The Promise and Perils of Alternative Forms of Data Representation." Educational Researcher 26 (6): 4-10. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X026006004 [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 1965. The Wretched of the Earth. London: MacGibbon and Kee. [ Links ]

Honan, E., and D. Bright. 2016. "Writing a Thesis Differently." International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 29 (5): 731-13. [ Links ]

Kumashiro, K. K. 2000. "Toward a Theory of Anti-Oppressive Education." Review ofEducational Research 70 (1): 25-53. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070001025 [ Links ]

Kumashiro, K. K. 2002. Troubling Education: Queer Activism and Antioppressive Pedagogy. New York: Routledge Falmer. [ Links ]

Lather, P., and E. A. St. Pierre. 2013. "Post-Qualitative Research." International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (6): 629-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788752 [ Links ]

Leavy, P. 2009. Method Meets Art. Arts-Based Research Practice. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Leavy, P. 2013. Fiction as Research Practice. Short Stories, Novellas and Novels. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [ Links ]

Mati, T. 2016. "Understanding the Struggle Songs of Fees Must Fall." Media for Justice, February 2. https://www.mediaforjustice.net/understanding-the-struggle-songs-of-fees-must-fall/ (accessed April 4, 2017).

Mbembe, A. 2015. "Decolonizing Knowledge and the Question of the Archive." Lecture presented at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WISER). http://wiser.wits.ac.za/content/achille-mbembe-decolonizing-knowledge-and-question-archive-12054 (accessed November 1, 2016).

Nhlengethwa, S. 1990. It Left Him Cold-The Death of Steve Biko. Collage, pencil and charcoal. http://artthrob.co.za/03oct/artbio.html (accessed April 7, 2017).

Richardson, L., and E. A. St. Pierre. 2005. "Writing: A Method of Inquiry." In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed., edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, 959-78. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Van Manen, M. 1991. The Tact ofTeaching: The Meaning of Pedagogical Thoughtfulness. New York: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Vladislavic, I. 2011. The Loss Library. Cape Town: Random House Struik. [ Links ]

Zembylas, M. 2007. "Risks and Pleasures: A Deleuzo-Guattarian Pedagogy of Desire in Education." British Educational Research Journal 33 (3): 331-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701243602 [ Links ]