Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.21 n.2 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/2009

ARTICLE

The slightest gesture: deligny, the ritornello and subjectivity in socially just pedagogical praxis

Chantelle Gray van Heerden

University of South Africa. gray.chantelle@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Positing existence in terms of difference and becoming as substantive, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari are interested in ways of thinking and being that lie outside of institutionalised knowledge and the semiotic chains and regimes of power that sustain it. Although this line of thinking is not applied to pedagogy itself in a sustained manner in their work, their consideration of milieu and cartography, as related to subjectivity, can make an invaluable contribution to pedagogical praxis. In this paper, I diffractively read Deleuze and Guattari's thoughts on subjectivity through the writings and practices of Fernand Deligny. Like Deleuze and Guattari, Deligny was known for rejecting standardised forms of knowledge, instruction, and living, placing instead an emphasis on modes of being that lie outside the preexisting norms of the Symbolic Order and the dominance of language. It is, in part, from Deligny's practices that Deleuze and Guattari derived their method of cartography which can map subjectivity as "wander lines" and gestures within a social milieu. Together with territory, rhythm and the refrain (ritournelle), I think here about wander lines, gestures and milieu as part of a philosophical approach for effectuating socially just pedagogies in higher education, particularly in the context of the recent Fallist movement in South Africa.

Keywords: Deleuze and Guattari; Deligny; mapping; milieu; rhythm; ritornello; socially just pedagogies; subjectivity; territory

A TENTATIVE: THE ANARCHIST WINTER SCHOOL, MAY - JULY 2015, CAPE TOWN

Working with autistic children and grappling with how subjectivities are shaped and dichotomised as either normal or marginal ("abnormal"), pedagogue, filmmaker, and author, Fernand Deligny, piloted a series of residential programmes in the early 1950s "for children and adolescents with autism and other disabilities who would have otherwise spent their lives institutionalised in state-run psychiatric asylums" (Hilton 2015). These programmes were called "attempts" (tentatives) and involved an improvisational process without a history; a process "situated within the space of now, now being a historical moment" (Deligny 2015, 151). Similarly, anarchist (free) schools are based on models of experimentation. Two well-known examples of free schools are the Anarchist Free University in Toronto (AFU) and the Nottingham Free School in the UK. Importantly, these schools should be viewed as examples rather than models as anarchist pedagogies may, and do, take many forms, in the same way as Deligny's tentatives did. Based on prototypes experimented with in existing anarchist communities and popularised by Francisco Ferrer, such schools encourage independent and critical thinking, personal and collective development, participatory involvement, consensual practices, heterogeneity, creativity, and "the limiting of stratifications based on expertise or experience" (Shantz 2012, 132). They are thus founded on: 1) principles of free collaboration which allow for wide accessibility and non-authoritarianism, and 2) collaborative curriculum development so that knowledge is viewed as collectively produced and power does not become associated with certain forms of knowledge. Moreover, these schools are anti-State, counter-cultural, reliant on mutual aid and mutual sharing, and often constitute collaborative efforts between grassroots movements and other individuals. Anarchist free schools and free universities are, therefore, experiments in pedagogy which have decentralised structures and where educators with a range of expertise typically come together to share their knowledge freely with others in an attempt to collectively produce new knowledge/s.

With these idea(l)s in mind, three members (including myself) of the Cape Town based anarchist collective, bolo'bolo, came together in December 2014 to think about ways in which to experiment with a free school. For a number of reasons, including human capacity at that time, the Cape Town free school differed slightly from typical anarchist free schools, such as the AFU which offers a range of subjects, as our focus was exclusively on anarchist history, political theories, philosophy, practices and strands (for the invitation, see http://www.bolobolo.co.za/events.html; posters were also made and distributed). The course ran for eight weeks on Saturday afternoons from 14:00 - 17:00 (the invitation says 16:00 but, after the first session, participants felt that the classes had to be one hour longer) and the curriculum was collectively developed during the first meeting. Around 20 participants from diverse backgrounds came and took part on a donation basis to cover printing costs and the renting of a room at the Observatory Community Hall, although it was made clear that donations were not mandatory so that anyone who wanted to would be able to attend. The choice of venue was also decided on because of its easy access via train lines and taxi routes.

Each session had a slightly different structure, according to what the content lent itself to, but all sessions included work in smaller groups and then a final round with the entire group. Each session was evaluated to take into account the needs of participants and any desired changes for the following class. For example, one participant struggled with ADHD and talked about this to the group after the third session. To accommodate this, we divided the sessions into different kinds of activities and included footage from other anarchists around the world in order to break the monotony of one kind of activity but, also, to show what different anarchists around the world do and think. As the weeks continued, the participants became more and more involved in the process and I was overwhelmed by the way in which the teaching/learning dichotomy gradually became eliminated. Subsequently, I began to think about how to transfer the principles exercised at the Anarchist Winter School to higher education. Currently at a distance university, I found this quite difficult at first but, inspired by the experience of the Winter School, I began to think about the process philosophically and then, increasingly, found ways in which to apply these philosophies and principles to my teaching practices and curriculum design. In particular, I am trying to challenge existing ways of knowing and the power attached to certain forms of knowledge through collective knowledge production. Thus, in my Gender Theory course, I now include a component of what Donna Haraway (1988) refers to as "situated knowledges" so that each assignment is viewed as an attempt aimed at collaborative learning, knowledge production and experimentation. Instead of only asking students to answer questions on gender theory (which includes both African and "Western" theorists), they are also asked to talk about their personal experiences of gender. For example, they are asked to think about how they feel about their own gender (affective responses), what internal and external pressures they perceive and how these inform their actions and emotions, how their gender is related to cultural and social norms and the tensions between these (or not), and so on. In this way, the personal stories of the students are viewed as part of knowledge production and their positioning as students with less authority than lecturers is challenged. As Donna Haraway (1988, 586-87) states: "The knowing self is partial in all its guises, never finished, whole, simply there and original; it is always constructed and stitched together imperfectly, and therefore able to join with another, to see together without claiming to be another."

What I offer here, then, is a theoretical contribution towards a more nuanced understanding of socially just pedagogies in higher education. Motivated by the Anarchist Winter School, as well as the method of cartography developed by Deligny and Deleuze and Guattari's thoughts on territory, rhythm and the refrain (ritournelle), I think about ways in which we might reimagine the ethical, ontological and epistemological assumptions of subjectivity. This, for me, is especially important in light of the recent student-led Fallist movement in South Africa which has pointed so clearly to a major crisis in subjectivity in higher education.

A QUESTION OF SUBJECTIVITY

Although Deligny is well known and regarded by many French educators and alternative psychiatrists, his work has only recently received attention in Anglo-Saxon academia, despite his influence on Deleuze and Guattari's philosophy (Wiame 2016, 38). This is due mainly to the fact that his work has only recently been translated into English, with The Arachnean and Other Texts published in 2015, though it may also be because his writings are, at times, quite difficult to follow and without a clear structure, more like sketches or wandering lines. However, this wandering method is a clear demonstration of Deligny's continual resistance to the primacy of language and identity and the power apparatuses by which they are informed and sustained. In his words, "[t]he human-that-we-are is the product of a long process of domestication," or, put differently, "humans surrender to the forces that have led them to where they are" (Deligny 2015, 76). Troubled by the dichotomisation of subjectivities as normal/abnormal, Deligny conducted a series of residential programmes for children and adolescents with autism which he called "attempts" (tentatives), as I mentioned before. These attempts were "in search of a mode of being that allowed them [the participants] to exist" without taking "into account any particular conceptions of mankind" (Deligny 2015, 79) so that no subjectivity was subject to another, more dominant or normalised, one. These attempts were held at La Grande Cordée (meaning "the great cord") which was founded by Deligny, funded by the educational theorist Henri Wallon, and run as a collective. In 1953 "La Grande Cordée lost its state funding and Deligny was forced to give up his headquarters" (Hilton 2015). Destitute and nomadic, Deligny, a number of his companions, and "Yves, the autistic boy of the film The Slightest Gesture" (Dosse 2010, 72), arrived in search of refuge at La Borde, an experimental psychiatric institution established by Jean Oury.1 This was also the clinic where Guattari had been working since the mid-1950s. "Deligny was immediately given a drawing workshop to oversee, and his whole group took up residence at La Borde, where he treated psychotics but primarily autistic patients" (Dosse 2010, 72).

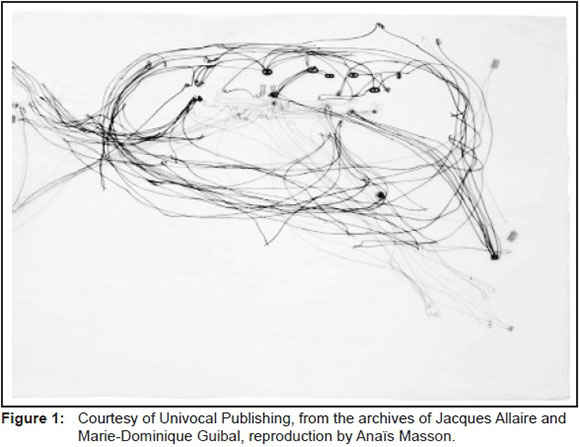

Soon, even La Borde became stifling for Deligny and, in 1967, he moved to the Cévennes Mountains where he lived until his death on 18 September 1996. It was here that Deligny explored in full his longstanding preoccupation with cartography, undertaken by him, his colleagues and the autistic patients he lived with. The method was simple, yet profound. At first, "they trace a basic map of the living-place, organised around points of reference from everyday life" (Wiame 2016, 44), such as the kitchen, the bathroom, bedrooms, the water-well, and so on. Next, "they put a tracing sheet on the map" and use it "to describe the movements performed in the territory" during the day (44). Thus, whereas the first map marks points, the second tracing consists of lines mapping the movements of those known as "close presences," indicating actions such as cooking or drawing water from the well. These lines are generally straight and of a practical nature. But there are also other lines which are "curved, repetitive, going nowhere" in particular. These lines trace the journeys of the autistic children and "Deligny calls these nonutilitarian lines lignes d'erre (wander lines)-a concept that will catch Deleuze's and Guattari's attention" (44), particularly for the way in which rhythm emerges from them, as a diffractive reading reveals.2 The result looks something like this:

What we have here, then, is a method that considers subjectivity not only in terms of subjects but, also, in terms of milieu, thus rejecting the primacy of language for the formation and legitimacy of subjectivity. Deligny, who worked with many mute autistic patients, rejected reductive psychoanalytic interpretations of autism, as well as Lacan's model which posits that linguistic structure and its reliance on the symbolic renders subjects the necessary product of signification (as a result of identification with a "master signifier"), and "language the sine qua non condition without which there would supposedly be nothing to think" (Ogilvie 2011, 82 quoted in Wiame 2016, 48). Instead, Deligny emphasises the arachnoid network which favours the rhythmic impermanence of minor movements over molar modes of social organisation, and fixed notions and representations of personhood. As Anne Sauvagnargues (2016, 164) explains, this kind of spidery web-weaving accentuates "collective production," as well as "incomplete lines that are contingent," immanent and emergent. Importantly, though, despite the fact that the network introduces a sense of play through the emerging rhythms, it is immediately political, an infinite experiment that "must necessarily fail" (Sauvagnargues 2016, 164). Thus, unlike the then dominant psychoanalytic conception of subjectivity which "establishes a profound link between the unconscious and memory," so that it is "a memorial, commemorative or monumental conception that pertains to persons or objects" and renders milieus "nothing more than terrains capable of conserving, identifying or authenticating" these memories (Deleuze 1997, 63), Deligny's cartographic method does something altogether different. As Deleuze (1997, 63) observes:

Maps, on the contrary, are superimposed in such a way that each map finds itself modified in the following map, rather than finding its origin in the preceding one: from one map to the next, it is not a matter of searching for an origin, but of evaluating displacements. Every map is a redistribution of impasses and breakthroughs, of thresholds and enclosures, which necessarily go from bottom to top. There is not only a reversal of directions, but also a difference in nature: the unconscious no longer deals with persons and objects, but with trajectories and becomings; it is no longer an unconscious of commemoration but one of mobilisation, an unconscious whose objects take flight rather than remaining buried in the ground.3

Drawing on Deligny's wander lines, Deleuze and Guattari highlight (at least) five aspects of these lines as they relate to the two primary considerations of subjectivity, namely subjects and milieu. Specifically, I would like to think about these five aspects in terms of socially just pedagogies, a phrase applied "to a wide range of concerns and phenomena," such as learning processes, outcomes, "the conditions for learning" and teaching, critiques of "the injustices of the past and present," methods of "de-schooling" and "unlearning," and envisioning and enacting "socially just futures in an affirmative manner" (Leibowitz 2016, 219). The five aspects can be summed up as follows: 1) it "is an affair of cartography; 2) it has "nothing to do with language"; 3) it has "nothing to do with a signifier"; 4) it has "nothing to do with a structure"; and 5) the "lines are inscribed on a Body without Organs, upon which everything is drawn and flees, which is itself an abstract line with neither imaginary figures nor symbolic functions: the real of the BwO" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 203).4

Besides the concerns and phenomena of socially just pedagogies mentioned above, I would argue that we can also think about wander lines in terms of subjectivity-as Deligny does-and how subjectivities are shaped and reproduced in higher education, both in terms of subjects (including, but not limited to, identity) and milieu. The recent student-led Fallist movement in South Africa has very clearly illustrated the current crisis in subjectivity in higher education. The movement was initiated on 9 March 2015 when Chumani Maxwele covered a bronze statue of colonialist Cecil John Rhodes, located on the main campus of the most prestigious university in South Africa-the University of Cape Town (UCT)-with human faeces. Initially directed at the removal of the statue and institutional racism (and known as #Rhodesmustfall), the movement soon developed into more comprehensive discussions about decolonisation and white supremacy. Similar concerns have been voiced throughout the world in recent history. We may think here, for example, of the Black Lives Matter movement which originated in the African-American community in the US, the racially motivated violence against Indian students in Australia and the ensuing protests in 2009 (Verghis 2009), and the Dutch student protests in 2015 in which the neoliberalisation of higher education institutions was opposed (Gray 2015). These protests have marked a significant turn in history, both locally and abroad. As Nombuso Mathibela and Simamkele Dlakavu (2016) write:

When Fallists wrote the phrase "Biko Lives", they were citing his work as part of the theoretical framework informing their actions in redefining blackness in post-apartheid South Africa. And when they sang the words "Biko Lives", they were reclaiming their subjectivity and expressing their political ideals.

It is through chants such as these and protests such as the ones I mentioned that students have, notably, pierced the global social imaginary by drawing attention to the continuing structural injustices stemming from the colonial era in general and, in South Africa, from the apartheid era in particular. But while such actions allow for new subjectivities to emerge, there has been an observable emphasis on identity politics, of which race and gender are central. Race theorist, Adolph Reed (2013, 49), explains race and other identity categories as based on ideologies "of ascriptive difference [which] help to stabilise a social order by legitimising its hierarchies of wealth, power, and privilege, including its social division of labour, as the natural order of things." He goes on to argue that the capitalist recuperation of struggles for racial and gender equality has led to a situation where "versions of racial and gender equality are now also incorporated into the normative and programmatic structure of 'left' neoliberalism" (Reed 2013, 53). In other words, identity categories, such as race, and everything that goes with it, such as racism, racial exclusion and racial violence (although these can easily be thought of in terms of other identity categories, such as gender, ableism, and so on), have "been fully legitimised within the rubric of 'diversity'" (53). This is not to say that identity politics is entirely without merit, as it does in fact modify the collective desire investment of a society by rupturing and deterritorialising central conceptions and formations of identity. However, identity politics or, rather, the neoliberal recuperation of identity struggles, also reifies identity and representations of identity, often reproducing binaries based on sameness and gradations of deviation. As Deleuze and Guattari (1987, 178) note:

From the viewpoint of racism, there is no exterior, there are no people on the outside. There are only people who should be like us and whose crime it is not to be. The dividing line is not between inside and outside but rather is internal to simultaneous signifying chains and successive subjective choices. Racism never detects the particles of the other; it propagates waves of sameness until those who resist identification have been wiped out (or those who only allow themselves to be identified at a given degree of divergence). Its cruelty is equaled only by its incompetence and naïveté.5

In order to think about subjectivity beyond identity and its representations in and through language-that is, in terms of difference and becoming as substantive or constitutive-I want to investigate subjectivity here not only in terms of subjects and identity but, also, in terms of milieu and as the inscription of lines on the Body without Organs. Deligny's mapping of the milieu inspired Deleuze and Guattari's conception of the rhizome-principally the idea of moving from the middle (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 21)-although they also speak of milieu in terms of multiplicity, the stratum, sources of energy, the Body without Organs (and the distribution of intensities as exemplified by the Dogon egg), the constitution of a landscape (faciality and landscapification), becoming, the ritornello, smooth space, and so on (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 31, 48, 51, 164, 181, 262, 313, 379). As Brain Massumi, the translator of A Thousand Plateaus (from now on ATP) notes, the French term milieu refers to "surroundings," or the environment or ecosystem; the "middle," thus not binary relations or clear points; and "medium," as it is used in science to refer to a substance that has the capacity to transfer energy from one place or source to another and, as such, denotes movement (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, xvii). In thinking about milieu, all of these connotations should be combined. Furthermore, Deleuze and Guattari (1987, 504) write that the "territory is more than the organism and the milieu, and the relation between the two; that is why the assemblage goes beyond mere 'behaviour' (hence the importance of the relative distinction between territorial animals and milieu animals)." Here we see an important distinction: the milieu is not the territory (the map, as I will discuss later, is also not the territory). Particular attention is paid to this distinction in the eleventh chapter of ATP, entitled "1837: Of the Refrain." In this chapter, Deleuze and Guattari think about the constitution of a refrain (which I will, from now on, refer to as ritornello) in terms of milieu and rhythm.6They apply these thoughts to three opening vignettes and then, most consistently, to birdsong and bird behaviour, although they also cite the three (non-discreet) eras in Western music, namely Classicism, Romanticism and Modernism which correspond to three aspects of the ritornello, namely Chaos (milieu), Earth (the natal or territoriality) and Cosmos (or the opening to the destratified, deterritorialised, non-subjective outside or cosmic). Although Deleuze and Guattari (1987, 325; translation modified) state that "the sound component 'ritornello' has a stronger valence than the gestural component 'grass stem'" in the composition of new assemblages, they do also state that the gestural "grass stem is a deterritorialised component, or one en route to deterritorialisation." As such, it is "neither an archaism nor a transitional or partobject" but, rather, "an operator, a vector," "an assemblage converter" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 324-25). I will explain this more in a later section.7 Suffice it to say that in thinking about socially just pedagogies, I consider especially these gestures-even the slightest gesture, as Deligny would have it-within a milieu and as a ritornello to rethink and reimagine the ethical, ontological and epistemological assumptions of subjectivity so that they are grounded in difference (rather than diversity) and becoming (rather than identity).

OF THE RITORNELLO: MILIEU, RHYTHM (DIFFERENCE) AND (DE)TERRITORIALISATION

In the plateau on the refrain, Deleuze and Guattari discuss the tendencies of the ritornello. The Oxford Companion to Music defines a ritornello as referring to "anything 'returned to' in music" (Scholes 1970, 883); for example "the return to the full orchestra [a tutti passage or movement] after a solo passage." We can infer from this explanation that the ritornello is marked not only be a returning to but, also, by a contrasting passage or movement-what Deleuze and Guattari call motifs (rhythm) and counterpoints (melody) respectively. Importantly, the point of the discussion on the ritornello in ATP is not merely to describe the three main eras of Western music, nor to give an explanation of territoriality (the three vignettes) or nature (birdsong and associated behaviour) in terms of the ritornello, although they also do this. Rather, Deleuze and Guattari set out to give a generalised account of the ritornello in order to address the philosophical problem of consistency (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 323). They do this by explicitly linking the notion of the ritornello (of which the basic elements are rhythm and milieu) with the ways in which territories are inhabited, governed and deterritorialised. In other words, it is "the respective play of territorialities, reterritorializations and movements of deterritorialization" (Deleuze and Parnet 2007, 99). In philosophy, the problem of consistency goes back as far as Plato who proposed a theory of Forms or Ideas as a solution. Thus, Plato posits that Being has certain ideal Forms (or Ideas). These are ontological properties that are abstract, eternal, changeless and independent of ordinary entities or objects. These properties are often formulated as Beauty, Goodness and Truth and can be said to be transcendent or metaphysical in nature. In contrast to this eternal world of Ideas, Plato postulates that there is also an intelligible world of relative forms that are transient so that consistency is viewed as reliant on discontinuity. Thus, whereas the relative form of beauty, for example, changes over time and even fades away (and is thus inconsistent and discontinuous), the ideal form of Beauty (which informs the relative form) remains consistent. For Deleuze and Guattari, however, consistency-and also metaphysics-is not a transcendent problem, but one which is immanent, emergent and contingent. In other words, consistency is derived from continuity (the return to; the ritornello) rather than discontinuity and inconsistency. To clarify this position, the chapter opens with three vignettes (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 311):

I. A child in the dark, gripped with fear, comforts himself by singing under his breath. ... The song is like a rough sketch of a calming and stabilising, calm and stable, centre in the heart of chaos. ... II. Now we are at home. But home does not preexist: it was necessary to draw a circle around that uncertain and fragile center, to organise a limited space. . The forces of chaos are kept outside as much as possible, and the interior space protects the germinal forces of a task to fulfill or a deed to do. ... A child hums to summon the strength for the schoolwork she has to hand in. A housewife sings to herself, or listens to the radio, as she marshals the antichaos forces of her work. . A mistake in speed, rhythm, or harmony would be catastrophic because it would bring back the forces of chaos, destroying both creator and creation. III. Finally, one opens the circle a crack, opens it all the way, lets someone in, calls someone, or else goes out oneself, launches forth. ... This time, it is in order to join with the forces of the future, cosmic forces.

These three vignettes, Deleuze and Guattari tell us, are not successive progressions but three simultaneous aspects or tendencies of the ritornello: Chaos (milieu and rhythm), Earth (territory), and Cosmos (the eternal return, a concept they borrow from Nietzsche). From chaos, milieus and rhythms are born so that every milieu or "block of spacetime" is coded "by a periodic repetition" or rhythm (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 313). Two things are important about chaos: 1) it can never be fully tamed and thus always threatens interference, enervation and collapse (we remember here Deligny's networks that must necessarily fail); and 2) this chaos indicates the immanent and emergent and, as such, underscores Deleuze and Guattari's univocal ontology which, unlike Plato's, is not reliant on an a priori "form or correct structure imposed from without or above" but is, instead, "an articulation from within, as if oscillating molecules, oscillators, passed from one heterogeneous centre to another" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 328). This we see also in Deligny's maps: rhythms emerging from the chaos around a fragile centre; a marking of home and territory, although home does not preexist; an opening to the outside, to wander lines and chance encounters, so unlike the Platonic model. This Platonic idea of Forms, I want to suggest here, is one of the greatest pedagogical impediments of our time as it proposes a model, a cartography in fact, where the Idea always comes before and the structure is thus necessarily imposed from without or above. As Jason J. Wallin (2014, 117) says, the "school [or any form of institutional education] not only anticipates the kind of people it will produce, but enjoins such production to an a priori image of life to which students are interminably submitted." As a result, identity (the unified, stable essence of being; the "I") and representation (which relies on drawing analogies between stable subjects) become primary so that, for example, diversity is substituted for difference and subjectivity is reliant on hierarchical conceptions ofthe subject without taking milieu into consideration. Pedagogy, according to this cartographic method, becomes a "closed and self-referential educational territory of standardisation" (Wallin 2014, 118)-what Ted T. Aoki (1993, 255-68) calls the planned curriculum as opposed to the lived curriculum-that can only ever allow for diversity and not for difference.

Posthuman and new materialist approaches to pedagogy have done much in terms of undoing this Platonic ontology by questioning the primacy of human subjectivity and conceiving of agency in ways that are not solely "tied to human action," thus "shifting the focus for social inquiry from an approach predicated upon humans and their bodies" to methods which examine, instead, "relational networks or assemblages" (Fox and Alldred 2015, 399)-an idea that is pivotal to Deligny's praxis as well. However, even though ontologies have been troubled, the ontological positionings of students and lecturers have, for example, remained largely unchanged in (South African) higher education, with teaching and learning viewed as the passing of knowledge from those with more authority to those with less. As Donna Haraway (1988, 581) explains, such practices "distance the knowing subject from everybody and everything in the interests of unfettered power." For Deleuze and Guattari difference and multiplicity are understood as substantive, and it is through becomings that we can disrupt practices which afford primacy to identity and representation-practices which distance the knowing subject from the less knowing subject. This notion of difference as constitutive is most fully developed by Deleuze in Difference and Repetition (1994), though we find a condensed version of part of his argument in his and Guattari's exposition of milieus and rhythm, or the ritornello, which diffracts quite powerfully with Deligny's praxis, as I have begun to show.

MILIEU AND RHYTHM, DIFFERENCE AND REPETITION

To begin with, there is chaos, as Deleuze and Guattari state in the first vignette: chaos, not structure. So structure-milieu and rhythm-is immanent, emergent and contingent (rather than imposed from above or outside), although this does not mean that chaos is "the opposite of rhythm." Rather, chaos is the "milieu of all milieus" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 313) while rhythm is that which codes the chaos in each of the milieus through transcoding and transduction, "the manner in which one milieu serves as the basis for another, or conversely is established atop another milieu, dissipates in it or is constituted in it" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 313). Milieus, which are not to be confused with territories, thus provide a certain amount of safeguarding against chaos, although they have not as yet reached consistency. As Guattari (2011, 107) puts it, a child sings at night because s/he "is afraid of the dark" and "seeks to regain control of events that deterritorialised too quickly," proliferating "on the side of the cosmos and the Imaginary." Thus, the singing, or rather, the returning to singing (the ritornello or eternal return) allows for a milieu to emerge from the chaos for the child. This milieu emerges through rhythm; a milieu therefore exists only "by virtue of a periodic repetition, but one whose only effect is to produce a difference by which the milieu passes into another milieu" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 314). To put it differently, it is not the repetition that produces difference through rhythm, as that would imply an a priori structure.

Rather, it is difference (or the chaos) that is rhythmic, so that difference is substantive rather than a product. To restate it once more: difference is constitutive which means that milieu and rhythm emerge from difference rather than difference being produced by the interaction between milieu and rhythm. As we see from Guattari's account of the child singing in the dark, milieus have three aspects: 1) external milieus which rely on exterior material elements (chaos or difference), 2) internal milieus which structure the external elements to provide some sense of unity and coherence (even though consistency has not as yet been attained), and 3) associated milieus which allow for the passing of elements between the external and internal milieus. In other words, although milieus provide some unity and coherence, the third aspect ensures an openness to the outside- an "element of chance and contingency" (Kleinherenbrink 2015, 213), like Deligny's wander lines. This ontological premise of difference, in conjunction with Deleuze and Guattari's conception of subjectivity which takes milieu into consideration, has major implications for pedagogy as "subjectivity is understood as simultaneously material (though not essentialist) and constructed (materially, socially, and in other ways) and thus subject to change" (Hroch 2014, 59). This makes me think again about what Deleuze and Guattari say about Deligny's wander lines: that it is an affair of cartography which has nothing to do with an imposing structure; that the lines are neither symbolic nor imaginary, but real and inscribed on the Body without Organs.

I want to linger here on Deligny, to think diffractively about his method of cartography in terms of milieu and rhythm and how we might apply his principles to socially just pedagogies, to subjectivity in the consideration of socially just pedagogies. A cartography is suggested by Deligny, writes Deleuze, "when he follows the course of autistic children: the lines of custom, and also the supple lines where the child produces a loop, finds something, claps his hands, hums a ritornello, retraces his steps, and then the 'lines of wandering' mixed up in the two others" (Deleuze and Parnet 2007, 12728). These lines are addressed and developed theoretically by Deleuze and Guattari in the ninth chapter of ATP, entitled "1933: Micropolitics and Segmentarity," although segmentarity is first addressed in an earlier plateau, "1874: Three Novellas, or 'What Happened?'" In these chapters, Deleuze and Guattari propose that life be understood in terms of three kinds of organising lines and segments, as we also find in Deligny's tracings and mappings: 1) "the first line, the molar or rigid line of segmentarity," 2) the second line which "is a line of molecular or supple segmentation" and is recognised by its tendency towards deterritorialisation, and 3) the "line of flight" which is unsegmented and characterised by the fact that it "has attained a kind of absolute deterritorialisation" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 195-97). These lines, like the aspects of milieus (external, internal, associated), or even of the ritornello (chaos, territory, cosmos), co-occur but, whereas the molar indicates the major components of our lives and typically contributes to what we perceive of as our identity, e.g. race, sex and gender, profession, nationality and so on, the molecular is more imperceptible, "traveling at speeds beyond the ordinary thresholds of perception" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 196) and thus denotes lines of deterritorialisation which may produce variations in the lattice of molar organisation.

When thinking about pedagogy, we can recognise the molar, planned curriculum, as well as the minor, lived curriculum, of which socially just pedagogies form part (though even socially just pedagogies have both currents, as well as the capacity for lines of flight, simultaneously). In other words, while there is the molar current, with its propensity to territorialise and reterritorialise (Deligny's first tracing or basic map of the living-place, organised around daily points of reference), which typically indicates relations that shape and govern the identity of subjects, there is a concurrent flow, the molecular, which is more transitory and tends towards deterritorialisation (like Deligny's second map which traces movement rather than objects or reference points).8 We can also think of these lines in terms of Chaos and Earth, or milieu, rhythm and territory. Finally, we have the third kind of line: lines resembling Deligny's wander lines which curve and meander so that they become amenable to variation and modification (the Cosmos), turning into lines of flight. This, for me, is one of the most important things about Deligny's maps: that they disrupt normative power relations rather than produce and reproduce them (see footnote 3) and, accordingly, allow for the creation-or emergence-of the genuinely new. So how can we think of subjectivities in higher education in this way? In terms of difference rather than diversity?

Deleuze and Guattari address this problem when they link the ritornello (rhythm and milieu) to the ways in which territories are inhabited, governed and deterritorialised. This coupling of the territory and the ritornello can be said to "provide a method to analyse, on a case-by-case basis, how living beings as a subset among assemblages, are situated in and dependent on the machinic patchwork of reality" (Kleinherenbrink 2015, 210). Instead of imposing a structure (the ideal Form) from above or outside, this method allows for a nomadic ethics to emerge, for the immanent structure or rhythm to emerge from the chaos, where difference is substantive. As a result, this method provides a radically different approach: to identity and subjectivity, to pedagogy, to epistemology and the ways in which knowledge is produced, to cartography, to being. In particular, the notion of territory as territorialisation and deterritorialisation allows us to think about the creation or production of the new and it is, then, in terms of (de)territorialisation that I diffract Deligny's maps with Deleuze and Guattari's idea of the gestural component or "grass stem." To put it differently, I think about the gestural grass stem, the "deterritorialised component, or one en route to deterritorialisation," also referred to as "an assemblage converter" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 324-25) in terms of socially just pedagogies-that is, socially just pedagogies as an assemblage converter.

Deleuze and Guattari explain the passage from one assemblage to another (or from one vignette to another) as the movement from function to expression. Moving away from the vignettes, they draw on the grass stem behaviour of Australian grass finches to explicate their position. During courtship, they explain, the male bird does not actually make a nest but, instead, "confines himself to transporting materials or mimicking the construction of a nest" and then courting the female by "holding a piece of stubble in his beak (genus Bathilda)," or using the grass stem only during "the initial stages of courtship or even beforehand (genera Aidemosyne and Lonchura)," or by merely pecking "at the grass without offering it (genus Emblema)" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 324). The grass stem, in other words, is no longer used for its function, namely nest building (a territorialising function), but has deterritorialised and become an element of courtship. Accordingly, the grass stem is an assemblage converter because "it is a component of passage from one assemblage to another" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 325), from function to expression. Thinking about the relations between milieus, or in terms of chaos, territory and cosmos, we could say that there is an increase in the autonomy of expression from Chaos to Earth, and then from Earth to Cosmos, so that expression operates progressively independent of its function, intensifying its deterritorialising capacities. The child sings in the dark; the housewife sings to herself in the home; the home is opened up or even left to go outside. We see the same in Deligny's maps: the tracing of familiar points of reference and objects, the tracing of the movement of close presences, the tracing of journeys and the production of wandering lines. In other words, movement is needed to go from function to expression, from territorialisation to deterritorialisation-movement, or, as Deligny might say, the slightest gesture. Pecking at the grass without offering it is an instance of the slightest gesture, of an assemblage converter. And when pedagogy breaks away from its function, even in the slightest manner, to become expressive, it acts as an assemblage converter, it moves towards being socially just.

The same is true for subjectivity, where subjectivity is not meant dualistically to describe its opposite, namely objectivity, but to map experimentations with ritornellos-events which are productive so that "what has been silenced or derided finds its own voice, produces its own standpoint, its own means of resisting a moral consensus, or a settled definition of what must be taken into account, or for granted" (Stengers 2008, 39). Thinking again about the recent student protests, we can see that what may be taking place are experiments with the ritornello. Students moving in and out of universities, softly humming to themselves to keep the chaos at bay, marking reference points. Perhaps these reference points at first provide comfort as they follow the movements of those around them: other students, staff, their own thoughts. Perhaps they notice the reference points were never theirs to begin with. The door is opened, the wandering lines produced. An eruption occurs, a deterritorialising movement brought about by the protests and debates around decolonisation and white supremacy. Climax is reached when the statue is removed and the fee increases are suspended. A resting period follows, a movement towards reterritorialisation, where new rhythms and milieus emerge. Then, another eruption, the ritornello again, as #Feesmustfall resurges. For many, very complicated reasons, justifiable reasons even, the student protests turn violent. For many similarly complicated reasons, it becomes difficult to talk about the import of US identity politics, to critique the neoliberal recuperation of identity when these subjectivities are so newly felt, so newly experimented with. However, as Isabelle Stengers (2008, 44) writes, if "subjectivity is to escape the critical clutches that signal the modern territory, immanent critique must present itself as an ingredient of the assemblage, not as critically examining/dismembering the assemblage itself." In other words, three new questions arise. The first is, how do we learn to know what this new situation may require, demand even, without resorting to call-out politics, turning instead to a feminist ethics of care, a socially just understanding of waiting in discomfort, together, while producing wandering lines and experimenting with the ritornello, mapping out real practices on the BwO and allowing for immanent critique (the emergence of milieus and rhythms)? The second question is, how do we sustain the energy of the climax so that we might begin to produce plateaus instead of wildly changing climaxes and rest periods? Apexes and respites are not necessarily unfitting and may, sometimes, be exactly what is required in a specific context. However, for Deleuze and Guattari (1987, xiv), the plateau is a term adopted from Balinese libidinal praxis as described by Gregory Bateson and "is reached when circumstances combine to bring an activity to a pitch of intensity that is not automatically dissipated in a climax." It thus indicates a kind of tantric practice during which the energies of the climax are first tempered and then prolonged and enhanced so as to repurpose it for other activities, turning it into an assemblage converter. Finally, taking all of this into consideration, how can we think of socially just pedagogies as the movement from function to expression and from expression to intensity where intensity is difference, not diversity?

I do not have answers to all of these questions and I open them up as further exploration of what socially just subjectivities might look like and how they might be produced. I do think, though, that it requires us to think carefully about the neoliberal recuperation of identity and the effects of call-out culture which rely on diversity and not, in fact, on difference (I say this even though I realise that identity is a very thorny issue and even though I understand that this is probably the most difficult aspect to deal with when thinking about subjectivity, especially in light of the recent student movements). As Deleuze (1994, 222) writes:

Difference is not diversity. Diversity is given, but difference is that by which the given is given, that by which the given is given as diverse. Difference is not phenomenon but the noumenon closest to the phenomenon. ... Every phenomenon refers to an inequality by which it is conditioned. Every diversity and every change refers to a difference which is its sufficient reason. Everything which happens and everything which appears is correlated with orders of differences: differences of level, temperature, pressure, tension, potential, difference of intensity.

CONCLUSION

As a philosophy, but also a practice, and philosophy-as-practice (theory-as-practice), I consider in this paper subjectivity and what it means to think about subjectivity from a socially just perspective, especially in light of the recent #Rhodesmustfall and #Feesmustfall protests in South Africa. Grappling with subjectivity as the outcome of processes of domestication, based on the Platonic theory of Ideas, I diffractively read Deleuze and Guattari's concept of the ritornello through Deligny's praxis of cartography as a method-an attempt or tentative-an experiment in subjectivity which takes into consideration both subjects and milieu. These spidery web-maps accentuate collective production, as well as the contingent, immanent and emergent. Accordingly, failure too is seen as a necessary condition which does not imply a miscarriage of an experiment but, rather, an immanent criterion. Thinking about Deligny's maps and Deleuze and Guattari's concept of the ritornello, I propose that we move away from subjectivity as grounded in diversity and identity and begin to think of it, instead, in terms of milieu, rhythm, and territory, in terms of difference and becoming. I do not think I have all the answers; instead I offer more questions, though I do suggest that Deligny's method of cartography and Deleuze and Guattari's philosophical practice of the ritornello provide us with a map that can aid us in thinking about subjectivity in higher education from a socially just perspective. In particular, I contend that socially just pedagogies can act as the slightest gesture, as the grass stem, the assemblage converter-a deterritorialising movement that allows for passage from function to expression, but also for passage from climaxes to plateaus, from diversity to difference and from identity to becoming.

REFERENCES

Aoki, T. T. 1993. "Legitimating Lived Curriculum: Towards a Curricular Landscape of Multiplicity." Journal of Curriculum and Supervision 8 (3): 255-68. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. 1994. Difference and Repetition. Translated by P. Patton. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. 1997. Essays Critical and Clinical. Translated by D. W. Smith and M. A. Greco. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by B. Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G., and C. Parnet. 2007. Dialogues II. Translated by H. Tomlinson and B. Habberjam. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Deligny, F. 2015. The Arachnean and Other Texts. Translated by D. S. Burk and C. Porter. Minneapolis: Univocal. [ Links ]

Dolphijn, R., and I. van der Tuin. 2012. New Materialism: Interviews and Cartographies. Michigan: Open Humanities Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/ohp.11515701.0001.001 [ Links ]

Dosse, F. 2010. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari: Intersecting Lives.Translated by D. Glassman. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Fox, N. J., and P. Alldred. 2015. "New Materialist Social Inquiry: Designs, Methods and the Research- Assemblage." International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18 (4): 399-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2014.921458 [ Links ]

Gray, J. 2015. "Dutch Student Protests Ignite Movement Against Management of Universities." The Guardian, March 17. https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/2015/mar/17/dutch-student-protests-ignite-movement-against-management-of-universities (accessed November 11, 2016).

Guattari, F. 2011. The Machinic Unconscious: Essays in Schizoanalysis. Translated by T. Adkins. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e). [ Links ]

Haraway, D. 1988. "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective." Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575-99. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066 [ Links ]

Harley, J. B. 1988. "Maps, Knowledge and Power." In The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environments, edited by D. Cosgrove and S. Daniels, 277-312. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press. [ Links ]

Hilton, L. 2015. "Mapping the Wander Lines: The Quiet Revelations of Fernand Deligny." Los Angeles Review of Books, July 2. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/mapping-the-wander-lines-the-quiet-revelations-of-fernand-deligny/ (accessed November 11, 2016).

Hroch, P. 2014. "Deleuze, Guattari, and Environmental Pedagogy and Politics: Ritournelles for a Planet- Yet-To-Come." In Deleuze and Guattari, Politics and Education: For A-People-Yet-To-Come, edited by M. Carlin and J. Wallin, 49-76. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Kleinherenbrink, A. 2015. "Territory and Ritornello: Deleuze and Guattari on Thinking Living Beings." Deleuze Studies 9 (2): 208-30. https://doi.org/10.3366/dls.2015.0183 [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. 2011. L 'Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze (Gilles Deleuze from A-Z) (film). With C. Parnet, directed by P.-A. Boutang, translated by C. J. Stivale. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Deligny, F. 1971. Le Moindre Geste (The Slightest Gesture) (film). Directed by J.-P. Daniel, F. Deligny and J. Manenti. Cannes: Cannes Film Festival. [ Links ]

Liebowitz, B. 2016. "In Pursuit of Socially Just Pedagogies in Differently Positioned South African Higher Education Institutions." South African Journal of Higher Education 30 (3): 219-34. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-3-646 [ Links ]

Mathibela, N., and S. Dlakavu. 2016. "Biko Lives in Fallism." News24, September 11. http://www.news24.com/Opinions/biko-lives-in-fallism-20160909 (accessed November 2, 2016).

Puar, J. 2011. "'I Would Rather Be a Cyborg than a Goddess': Intersectionality, Assemblage, and Affective Politics." Transversal Texts, January. http://eipcp.net/transversal/0811/puar/en/ (accessed December 1, 2016).

Reed, A. Jr. 2013. "Marx, Race and Neoliberalism." New Labor Forum 22 (1): 49-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1095796012471637 [ Links ]

Sauvagnargues, A. 2016. Artmachines: Deleuze, Guattari, Simondon. Translated by S. Verderber and E. W. Holland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Scholes, P. A. 1970. The Oxford Companion to Music. 10th ed. London: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Shantz, J. 2012. "Spaces of Learning: The Anarchist Free School." In Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education, edited by R. H. Haworth, 124-44. Oakland: PM Press. [ Links ]

Stengers, I. 2008. "Experimenting with Refrains: Subjectivity and the Challenge of Escaping Modern Dualism." Subjectivity 22 (1): 38-59. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2008.6 [ Links ]

Verghis, S. 2009. "Australia: Attacks on Indian Students Raise Racism Cries." Time, September 10. http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1921482,00.html (accessed November 11, 2016).

Wallin, J. J. 2014. "Education Needs to Get a Grip on Life." In Deleuze and Guattari, Politics and Education: For A-People-Yet-To-Come, edited by M. Carlin and J. Wallin, 117-40. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Wiame, A. 2016. "Reading Deleuze and Guattari through Deligny's Theatres of Subjectivity: Mapping, Thinking, Performing." Subjectivity 9 (1): 38-58. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2015.18 [ Links ]

1 Le moindre geste (The Slightest Gesture) is the title of a 1971 film, directed by Jean-Pierre Daniel, Fernand Deligny and Josée Manenti. The film narrates the story of two teenage escapees on the run from an asylum (starring the autist Yves Guignard and Annie as themselves). Taking refuge in the mountains of Cévennes, Deligny follows these "unmanageables" and experiments with the relational distance between the camera and human subjects, while posing important questions about subjectivity and, in particular, about the Radical Other.

2 Karen Barad (in Dolphijn and Van der Tuin 2012, 49-50) reminds us that diffractive readings entail "respectful, detailed, ethical engagements" which perturb or interfere-diffract-rather than merely critique which, all too often, results in a "destructive practice meant to dismiss, to turn aside, to put someone or something down." Deligny's work perturbed Deleuze and Guattari's own thoughts and practices from the beginning, especially their thoughts on cartography. And while Deleuze and Guattari do not relate Deligny's work directly to their thoughts on the ritornello as I do, reading their philosophy on the ritornello diffractively through Deligny allows for the emergence of new "patterns of differences that make a difference" (Dolphijn and Van der Tuin 2012, 49), particularly for thinking about socially just pedagogies.

3 John Brian Harley (1988, 278-79) observes that maps are not solely related to geographical information, but are deeply rooted in political power and could thus be viewed as "refracted images contributing to dialogue in a socially constructed world." As such, cartography is "a form of knowledge and a form of power." Deligny's method of cartography does the opposite, however, allowing for an equal distribution of power between himself, his colleagues and the autistic children.

4 The Body without Organs (BwO) is a term that Deleuze and Guattari borrow from Antonin Artaud's radio play, To Have Done with the Judgment of God (1947). In A Thousand Plateaus, they explain the BwO in terms of a forming egg which can be seen as an "intensity map" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 164) consisting of a distribution of densities, intensities and thresholds. These densities, intensities and thresholds have certain tendencies and capacities which are not yet fully formed or pre-structured. The BwO is thus about how we can create a map of intensities in our lives and about ways in which these intensities circulate and remain open to change, to chance encounters or, alternatively, shut down movement and become closed-in systems.

5 I am not in any way diminishing the struggles around identity. In fact, I fully support these. I am, however, critical of the neoliberal recuperation of identity, particularly the "call-out" culture (the public naming of instances of oppressive behaviour and/or language use) that has emerged from it. What concerns me is that this is a practice grounded not in an ethics of care, but in a moralistic code which often involves public shaming. Jasbir Puar's 2011 article, "'I Would Rather Be a Cyborg than a Goddess': Intersectionality, Assemblage, and Affective Politics" offers a very thoughtful response to identity politics and a list of articles dealing with different aspects of identity politics can be found here: https://fullopinionism.wordpress.com/.

6 The French word, ritournelle, has been translated in ATP as "refrain." However, in Dialogues II, the translators, Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam, explain that Deleuze preferred the English "ritornello" as the term denotes both "the musical sense" and "the repeated theme of a bird's song" (Deleuze and Parnet 2007, xiii), both of which I discuss in this paper. In L 'Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze (Gilles Deleuze from A-Z), a French television series consisting of eight hours of recorded conversation between Deleuze and Claire Parnet which was later released on DVD (2011), Deleuze says that "With Félix, I feel like we did some good work here, because I could say if necessary, if someone asked me, 'What philosophical concept have you produced since you are always talking about creating concepts?' We at least created a very important philosophical concept, the concept of the ritornello [...which directly relates] to the problem of the territory and of exiting or entering the territory, that is, to the problem of deterritorialisation." The ritornello is, thus, a central concept but, as Deleuze says, one that has to be understood in its "essential relation" to territory, a point also emphasised by Arjen Kleinherenbrink (2015, 209). For all of these reasons, I have chosen to use the term ritornello rather than refrain in this paper. Thus, when quoting from ATP, "1987: Of the Refrain," I replace all instances of the word "refrain" with "ritornello."

7 Briefly, this "grass stem" refers to the behaviour of Australian grass finches who mimic nest making so that the grass stem is not used for its function (i.e. to build a nest), but for the purposes of courting, and has thus become expressive.

8 Interestingly, Deleuze and Guattari draw a distinction between points and lines and this, in fact, links to what I was saying earlier about Deligny's method of cartography and how it disrupts the memorial or commemorative conception of milieus we find in psychology. "The line-system (or block-system) of becoming," they write, "is opposed to the point-system of memory. Becoming is the movement by which the line frees itself from the point, and renders points indiscernible ... Becoming is an antimemory" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 294).