Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.21 n.1 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/861

ARTICLES

Changing educational traditions with the change laboratory

Louis Royce Botha

University of South Africa - Medical Research Council. louis.botha2@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This paper outlines the use of a form of research intervention known as the Change laboratory to illustrate how the processes of organisational change initiated at a secondary school can be applied to develop tools and practices to analyse and potentially re-make educational traditions in a bottom-up manner. In this regard it is shown how a cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) perspective can be combined with a relational approach to generate the theoretical and practical tools for managing change at a school. Referring to an ongoing research project at a school, the paper describes how teachers and management there, with the aid of the researcher, attempt to re-configure their educational praxis by drawing on past, present and future scenarios from their schooling activity. These are correlated with similarly historically evolving theoretical models and recorded empirical data using the Vygotskyian method of double stimulation employed by the Change laboratory. A relational conceptualisation of the school's epistemological, pedagogical and organisational traditions is used to map out the connections between various actors, resources, roles and divisions of labour at the school. In this way the research intervention proposes a model of educational change that graphically represents it as a network of mediated relationships so that its artefacts, practices and traditions can be clearly understood and effectively manipulated according to the shared objectives of the teachers and school management. Such a relationally-oriented activity theory approach has significant implications in terms of challenging conventional processes of educational transformation as well as hegemonic knowledge-making traditions themselves.

Keywords: Change Laboratory; educational traditions; mapping; mediation; cultural- historical activity theory

INTRODUCTION

This article draws from research in progress in which the Change Laboratory is used to examine processes of change within an educational context. Tracing the deployment of this form of research intervention, the article describes the theoretical framework on which the Change Laboratory is based, and relates this to its practical application in a school setting. Thus, it looks at the ways in which the staff at a secondary school in Cape Town make use of the specific setup of the Change Laboratory to engage with each other in order to develop tools to modify, and hopefully improve, their work activity and the school as an organisation. The research takes place with the teachers and management of Cape Flats High School1 which is situated in a working-class area of the Cape Flats. The school can be described as under-resourced in that, according to the staff, many of the basic requirements for an engaging learning and teaching environment, including teachers, equipment and infrastructure, are lacking. It also faces a number of challenges related to the fact that the students come from economically poor black2 townships where basic amenities and services such as public transport, electricity, public libraries, recreation facilities and so forth are deficient or completely absent, and unemployment is high. According to the Western Cape Provincial Economic Review and Outlook (PERO):

Almost half of the unemployed in the Western Cape (50.9 per cent) are Coloured, while unemployed Africans represent 44.3 per cent. Approximately one in 20 unemployed individuals in 2013 was White. (PERO 2013, 119)

In addition to socio-economic challenges, the learners have to deal with difficulties related to travelling long distances to school, which in turn impact upon the school's ability to interact with parents, compounding problems of absenteeism, discipline and academic performance. These issues were reflected in the mid-year results which showed that the number of Grade 8 to 12 learners who achieved a passing grade of above 40 per cent were, respectively, 2 out of 87, 8 out of 155, 28 out of 139, 26 out of 83, and 13 out of 64.

On a positive note, several initiatives have been undertaken by students, researchers, volunteers and staff at the school in order to provide academic support as well as extracurricular activities for the pupils. Thus, projects such as a maths resource centre, a library, a marimba band, a choir, a garden, a chess club, soccer and table-tennis are being attempted at the school and have shown some success. Few of the staff at Cape Flats High School, however, seem to participate in these activities despite the high levels of frustration as well as of hope for greater student commitment and achievement that they expressed during interviews and observations. The initial interviews also indicate that there may be several reasons for the limited exploitation of additional and extracurricular activities. These include financial reasons such as a lack of funding for equipment, logistical reasons such as the difficulty in providing transport to and from venues, and issues of safety brought about by, for example, pupils' affiliation with gangs. However, it may also be because of teachers' reluctance to spend time on these activities, or because of a general lack of cooperation or collaboration among staff. It is this latter aspect which will be elaborated upon here as one of the major themes of a research intervention that examines meditational relationships as a means by which the educational environment and practices at the school may be modified.

Despite its micro perspective, the intervention remains grounded within the broader national context of educational change in which the school's activity must be understood. Samoff (2008), for example, identifies some of the systemic and ideological aspects of the recent changes within South Africa's education sector. These include, firstly, the reformist as opposed to transformative approach to education post-1994 that focused primarily on access to schooling through desegregating schools and increasing their number. He notes, however:

With few exceptions, schools remained hierarchical, authoritarian, and teacher-centred... Critical reasoning, self-reliant learning, cooperative approaches, community responsiveness, environmental awareness, self-confident assumption of responsibility, political consciousness, engaged citizenship, and more were marginalized. (Samoff 2008, x)

He goes on to argue that the conciliatory stance of the post-1994 leaders meant that the activism that characterised black people's participation in the education sector was replaced by a moderate stance "favouring management and incremental change over leadership and bold initiatives" (Samoff 2008, xi). Thirdly, Samoff, like Goodson (2003), questions the way in which teachers are cast as "technicians of education, expected to implement education reforms in a setting of contradictory incentives and rewards" (Samoff 2008, xii). While conceding that some teachers may have reacted to this top-down imposition of new rules, regulations and practices in a positive and creative way, many, he claims,

have become alienated and dispirited, unenthusiastically presenting a minimal curriculum and teaching to national examinations, with little effective accountability. Few are excited and activist champions of change. (ibid)

Although a mixed blessing (Soudien 2007), it appears that some educational change is necessary, especially in light of the dismal performances of South African pupils and the limitations these impose upon them, as Spaull (2013) makes clear in his report on the crisis in South African education. He points out that:

76 per cent of South African Grade Nine pupils did not reach the low international benchmark in TIMSS 2011. These pupils could not do basic computations or match tables to bar graphs or read a simple line graph. They had not acquired a basic understanding about whole numbers, decimals, operations or basic graphs.. .SACMEQ III (2007) showed that 27 per cent of Grade Six pupils were functionally illiterate since they could not go beyond decoding text and matching words to pictures, i.e. they could not interpret meaning in a short and simple text. (Spaull 2013, 39)

He also makes several recommendations of which two are directly relevant for the discussion here, namely: "Improve the management of the education system: ...provide intervention tools that do not require high levels of capacity" (Spaull 2013, 11), and:

Improve teacher performance and accountability: various proposals which cover training, remuneration, incentives, time on task, performance measurement, content and pedagogical support and teacher professionalism. (ibid)

On the other hand, Mausethagen (2013, 18) argues that, often during processes of educational reform, "conditions of trust, discretion, and competence, which are regarded as necessary for professional practice, are, to a greater extent, being challenged and regulated by new governance and control systems". Added to these tensions are South African teachers' long history of conflict and resistance to educational authorities (Chisholm and Chilisa 2012), and the tendency for research to emphasise the poor knowledge and skills of management and teachers (see, for example, Bush, Jobert, Kiggundu and van Rooyen 2010; Pretorius 2014).

The above-mentioned challenges together with the systemic tensions involved in introducing new forms of activity or resources, are studied at the school level from a cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) approach which views them as contradictions within an activity system. This is done through a project for which the data collection and analysis are operationalised through the Change Laboratory, an interventionist method of research derived from the CHAT approach. Essentially the Change Laboratory is a series of workshops held in a room specifically set up for the purpose where the workers at an organisation, in this case the teachers of Cape Flats High School, and the researcher-interventionist (myself) collaboratively address problematic areas of the organisation's work practices. Before detailing the theory and practice of this method, the main questions guiding the study will be briefly outlined.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The study upon which this article is based has the dual purpose of both implementing the Change Laboratory as a research intervention at a school, as well as evaluating this process, although the latter aspect is not elaborated upon here. It broadly posits the question of how the Change Laboratory may be used to investigate and manage the implementation of educational change within a school setting. This question reflects the project's interventionist orientation from within an activity theory framework and implies an investigation into the opportunities for generating change at the school, and hence the possibility for employing the Change Laboratory as a research intervention. It forms the basis of the more narrowly focused sub-questions, which are provisional given that the research follows the principles of formative research interventions as suggested by Engeström (2011). One of these principles advocates for the research participants themselves to identify the questions which will guide the study. Following this principle, I started off by conducting observations and an initial set of interviews at the school for a period of two weeks in order to establish what the staff's concerns were, and in this way determine the starting point for the intervention. The interviews were analysed and the main concerns presented in the first Change Laboratory session where the participants identified the areas of change which they wished to address.

Through this participatory process the main research question was developed to reflect the participants' concerns in terms of the analytical framework, resulting in the question: How can collaborative educational traditions be developed in a school activity system in which there is limited coordination between various elements like its tools, subjects, rules, community, and division of labour?

That this focus differed significantly from my own interests for the project is testimony to the philosophy of embracing "resistance and subversion" (Engeström 2011, 603) which characterises these formative interventions. My hope had been to introduce relational tools that could encourage the acknowledgement of indigenous knowledges and facilitate their use and prominence within a school that is predominantly attended by black learners but draws on cultural capital that is white middle class, as is typical for most South African schools. Instead the participants took the research focus, or object, in another direction. By following their lead, the research demonstrates the power of the DWR principle which challenges conventional research power relations that are typical for educational research where researchers often enter schools and dictate or impose agendas.

Nevertheless, while I have tried not to prescribe the focus of the intervention, it cannot be denied that those theoretical and ideological perspectives which I favour are strongly present in the conceptual framework of the intervention. As a result, the intervention is significantly guided by perspectives such as those expressed by Breidlid (2013), which challenge dominating epistemological traditions, although these are more implicitly, as opposed to explicitly pursued. This agenda of challenging dominant and dominating traditions can be evidenced in the promotion of relational processes of knowledge making and teacher professional engagement espoused by the research. As will be argued below, the project's attempts to foster a relationally-based epistemology, for instance, counters conventional "Western" ideas about and criteria for knowledge which centre around debates on "justified true belief (Gettier 1963), in favour of indigenous epistemologies and axiologies which foreground relationships (Carroll 2014). The research therefore attempts to demonstrate that shifting to a relational concept of knowledge may have profound effects in terms of power relations in a school context as well as more broadly for marginalised knowledge communities. However, the small scope of the intervention as a school-based project, as well as the tensions inherent within the Marxist roots of the development work research (DWR) methodology may limit the kind of radical systemic change aimed at here. Some of these limitations are outlined below, as is the contention that the nature of the reforms achieved by this intervention, and their potential for instigating fundamental change, should not be underestimated.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) can very broadly be described as a theoretical approach that understands human beings and social entities in terms of their activities (Kaptelinin and Nardi 2006). Thus, learning is viewed as a culturally mediated activity that has to be considered from an individual, inter-personal and systemic perspective. It views the dialectic between mind and culture as mediated within an activity system composed of tools, rules, multiple actors and a division of labour, all of which have to be considered in their entirety and historicised so as to understand their development over time.

From this perspective it is clear that there is a close correlation between learning and tradition, given that both examine the dynamics of change in terms of their cultural, normative, agential, mediated and temporal elements. This is evident when one considers Ratele's definition of tradition:

tradition is understood as a self-reflexive symbolic resource revolving around beliefs, practices, statements, customs, rituals, etc., which individuals as members of groups employ or engage in as part of "speaking" to their pasts (and others' pasts) in the present. Tradition is that space where the present consciously encounters the past. (Ratele 2014, 31)

In fact, in bringing the two concepts together in their discussion of tradition in education, Halpin, Moore, Edwards, George and Jones (2000) identify epistemological, organisational, pedagogical and curricular traditions. They define epistemological traditions as

constituted by the practices of different disciplines of knowledge, many of which are represented in the school curriculum.. .Such traditions include cultural selections of knowledge, texts and styles of representation. (Halpin et al. 2000, 137)

In this regard it is pertinent to note Reagan's (2004) warning of the danger of epistemological ethnocentrism which may severely limit our scope of what constitutes educational traditions. Organisational traditions, on the other hand, can be more deliberately selective in their focus upon schooling and would in that case reflect the values according to which a school offers its service, such as the inclusivity or exclusivity of public and private schools, respectively. Pedagogical traditions are concerned with the philosophies and practices around teaching and learning in the learning situation (ibid). The authors note that these particular forms of knowledge, texts, institutional structures, norms and practices

are routinely drawn upon by teachers in the course of constructing their professional identities and by schools as they develop their particular market identities. (Halpin et al. 2000, 138)

In an attempt to understand how they draw on these resources, the research at Cape Flats High maps out the artefacts, spaces, people and practices that the staff employ in shaping the above-mentioned traditions at their school. It uses a similar strategy to that of Reeves who notes:

Mapping networks provides a visual means of tracking the various pathways by which organisations and people are connected and hence of evidencing of lines of influence. (Reeves 2010, 27)

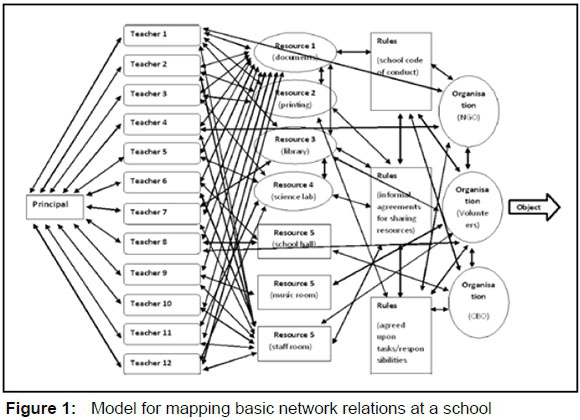

Figure 1, below, provides a rudimentary example of the kind of visual representation that the research attempts to make of the connections between actors and available resources. This type of representation is not unlike Borgatti and Foster's description of a network as "a set of actors connected by a set of ties. The actors (often called 'nodes') can be persons, teams, organizations, concepts, etc" (2003, 992). The alignment with a network approach allows for the possibility of using its concepts and analyses to elicit an understanding of the structural properties of the network and explain the nature and function of its ties in greater depth. At this point, however, the graphic representation of connections mainly focuses upon linkages and possible areas of tension between the various elements of the activity systems so as to facilitate the use of a relational model of the educational activity at the school.

The relational approach to learning situations used here is based upon Reeves's (2010) study of professional development, of which she states:

These teachers did not consider their learning as the simple acquisition and application of knowledge and skills, but as a far more complex process embedded in changes to their relationships with people and things, their professional identities, their knowledge and their capacity for action...In other words, they represented their learning as a complex interactional and relational process that was contextually grounded. (2010, 2)

Like cultural-historical activity theorists, she is concerned with identifying change and the agency behind it within collective processes of knowledge making. However, her criticism of activity theory is that its failure to effectively represent time and space weakens its ability to account for the complexity of the subject. To address this criticism the research with Cape Flats High School maps out CHAT relations in the form of a network and emphasises the importance of mediation in accounting for spacio-temporal change. The notion of mediation is complex, but can basically be understood as a process of constructing abstract and material realities by humans using physical or symbolic tools to act on an object (Prenkert 2010). As Hermansen and Nerland explain:

When we make sense of or interact with our environment, we do so by way of resources such as language, concepts, and material devices. These resources are historically developed, incorporate established ideas and collective knowledge, and carry suggestions for how they can be utilised. (2014, 191)

It is therefore argued here that change over time is located in the evolution of these resources, tools, or culturally developed artefacts, and the relationships that actors have with them, so that plotting these artefacts and relationships as nodes and linkages allows for the representation of the interactions and experiences that the actors have within the systems being represented. After all, as Kaptelinin and Nardi (2006, 71) point out, culturally developed artefacts are considered to be "fundamental mediators of purposeful human actions that relate human beings to the immediately present objective world and to human culture and history".

In this sense changes are not measured so much in time as they are tracked in the development and use of artefacts. The concept of social space as "something made in performance" (Reeves 2010, 26) then becomes relevant because it is in these spaces where people and things come together to give identity and meaning to each other and the space as well.

These spaces are embodied and material in that they are both "peopled" and "thinged" since they involve the use of linguistic and other, more obviously material, tools. (Reeves 2010, 26)

The classroom, with its teachers, students, seating arrangements, chalk board and other technologies, is a clear example of this dialectic. Reeves's understanding of social spaces is therefore not unlike that of an activity system, albeit with a different focus on time, in that the activity of a certain place occurs over a period of time, thereby also producing detectable outcomes such as behavioural patterns, identities, artefacts and so on. This temporal or historical character also resonates with the dynamic of tradition-making as "processes involving selective acceptance, partial rejection, and varying degrees of appropriation and synthesis" (Halpin et al. 2000, 142), and the focus on its materialisation in the form of artefacts, spaces and rules is evident from Figure 1. From the way in which the actors connect to some artefacts more than others, the figure is intended to illustrate patterns or even traditions of educational practice at a school where teachers are relying primarily upon documents such as the curriculum to guide their professional practice, while less conventional avenues geared around the use of music, recreational spaces, or even the library do not feature strongly in their pedagogy. (For an interesting discussion on why teachers may do this, see Moore, Edwards, Halpin and George 2002). By combining CHAT and relational approaches the research intervention would attempt to reconfigure the nature of the activity of the system through the introduction of new elements or nodes, and/or strengthening existing connections.

Hence the intention is no less than to reconfigure the nature of the educational activity system by developing (radically) different relationships through the introduction of mediating artefacts. Consider, for example, how the introduction or strengthening of relationships with religious texts would influence notions of truth, the teaching of science, who the experts are, and so forth, or, as indicated below, how an appropriately resourced conducive space may facilitate dialogue and collaborative forms of leadership.

Two other important aspects of the CHAT approach are the concept of the object of the investigated activity systems, and the role of contradictions within them. The object is the constantly shifting motive that orients the activity of the system.

The idea of an object motive is a useful one because it asks us to recognise that the way we interpret a task or problem will shape the way we respond to it, and that our interpretations are shaped by the social practices of the situations in which objects of activity are located. (Edwards 2011, 18)

In terms of the research at the school, the object of creating a more productive school environment has translated into a project of developing relationships that push the activity toward this object. This is similar to what Edwards calls "relational agency", which is "a capacity to work with others to expand the object that one is working on and trying to transform by recognising and accessing the resources that others bring to bear as they interpret and respond to the object" (2005, 172). The research intervention maps these efforts to engage the various elements in the system, thereby creating a diagramme of the network of relations from which the purpose and direction of the teachers' activity can also be assessed in terms of the collective object. Viewing the network of relations in this way, one could gauge, for example, the extent to which activities or social spaces such as those involving music or sport are engaged with the object.

CHAT furthermore illuminates the mechanisms of these processes by identifying contradictions that operate at various levels of the activity systems. Contradictions are the "historically accumulating structural tensions within and between activity systems" (Engeström 2011, 609) and should not be equated to paradoxes, tensions, or conflicts which are merely their manifestations (Engeström and Sannino 2011). Some of these contradictions are alluded to above, such as when reforms of governance and control compromise the professionalism of teachers. Moreover,

Primary contradictions are those found within a component of the activity (i.e., in the rules, norms, object, etc.) and secondary contradictions are those that occur between constituents of the activity (for instance, between the community and the tool). (Allen, Brown, Karanasios and Norman 2013, 840)

CHAT analysts consider these contradictions to be so fundamental that the disruptions which they cause provide the driving force for the system's development. In the case of Cape Flats High where the object is to improve the overall school environment by developing and connecting appropriate spaces and resources, the contradictions involved in bringing together an array of diverse actors, knowledges and practices tend to disrupt existing epistemological, pedagogical and organisational traditions to such an extent that new, often creative forms of activity become necessary. Very often, however, teachers are expected to accommodate the resulting practices, procedures and projects rather than initiate and drive them. In an attempt to turn this situation around, and draw on the agency of teachers as resourceful practitioners, the research makes use of the Change Laboratory.

METHODOLOGY

As indicated by the research questions and above theoretical framework, the intention of the research was to demonstrate the use of a participatory form of research intervention at a secondary school in the Cape. The school was conveniently selected after informal discussions with the principal indicated that the school would be a good candidate for the type of research intervention I had in mind. I therefore started out by meeting with the school principal and explaining the intended design and purpose of my research. He in turn described the school in terms of its demographic, ethos, academic performance, organisation, day-to-day running and specific challenges. Following this interview I drew up a brochure in which the broad research aims and methodology were outlined. At my next visit to the school I was introduced to the staff and the brochure was circulated among them. Over the course of the next two weeks I spent five or six days sitting in the staff room fielding questions about my research and getting to know some of the teachers. I gradually started to familiarise myself with the school and eventually proceeded with doing unstructured observations in the staff room, hallways and open spaces of the school. On several occasions the principal allowed me to observe and shadow him in daily interactions with parents, learners, staff, department officials, and community organisations. Gradually I became familiar with some of the projects, challenges, history, politics, and individual staff members at the school. In turn, I tried to be open about my own history, politics, hopes and aspirations - regarding the research and education more generally. Eventually some of the teachers took an interest in my research and agreed to be interviewed. These initial interviews elicited information on the teachers' experience and general approach to education, as well as their knowledge, experience and opinions about teaching at Cape Flats High. During this first phase of the research, nine initial interviews were conducted. These were transcribed and the main themes were analysed to identify the primary areas of concern for the staff. A Change Laboratory session was then set up, as described below. During the session, the research methodology was explained to the participants and the emerging areas of concern were also presented and discussed.

A Change Laboratory is a form of research intervention based on CHAT principles, some of which were outlined above. Kerosuo, Engeström and Kajamaa (2010) define it as "a research-assisted environment of change in which participants can re-design their work activity and organisation by creating new models, tools, and practices with the aid of researcher-interventionists" (2010, 112). In practical terms it is organised as a specially prepared room where the practitioners - in this case the teachers and management - and researchers gather in order to collaboratively model new tools and practices that could improve their organisation, the school, and their experience of work. As can be seen from Figure 2, they do this by tracing, over time, the development of theoretical models, emerging ideas and ethnographic data using three wall boards or flipcharts that are set up in the room.

Thus, viewed from left to right in the figure, the first wall board is for the theoretical models that will be used for analysing information. These are generally offered by the researcher and include CHAT activity systems and expansive learning cycles, among others. The second board is for new ideas and tools that the participants come up with, such as work schedules, protocols, fora, and so forth. The third surface, the mirror, is used to show information that has been gathered about the organisation, such as video material, interviews, statistics, and so forth.

The Change Laboratory, then, is a research intervention in which a very specific type of research environment is set up to offer a range of abstract and concrete tools with which the participants can engage with each other and the challenges and innovations they face in their work activity and/or organisation. Through a collective cycle of expansive learning the participants critique existing aspects of their activity system, model and restructure them and then experiment with and reflect upon the new practices or tools, instigating further cycles of revision and innovation as required. In the case of this research it is the staff at Cape Flats High School who examine and respond to the tensions generated by changes within the school and attempts to transform educational traditions there. This is achieved through several Change Laboratory sessions of between one to three hours each which are then video recorded, transcribed, and analysed by the researcher, and re-presented to the staff in the sessions which follow.

Since the research also involves evaluating the efficacy of this form of research in a school setting, the theoretical and practical emphases advocated by Engeström's (2011) interpretation are somewhat uncritically adopted and applied. Thus, for example, the research aligns itself with the principles proposed for formative interventions, such as a focus on process rather than final outcomes or solutions, the use of Vygotsky's method of double stimulation, and the generation of the entire research, including its aims, from the bottom up by its participants (Engeström 2011). Following these principles, the initial observations and interviews were used to identify the starting point for the intervention as indicated by the participants. That is, the observation and interview material was analysed to identify which areas of change the participants wished to tackle in the Change Laboratory sessions. Samples from this process, which were also shown to the participants in the first Change Laboratory session, are presented in the findings section below. Change Laboratory sessions were video recorded so that, in subsequent sessions, selected video clips and transcriptions from previous Change Laboratory sessions could be presented to the participants. At the same time relevant models and concepts, also applied in this article, were offered as analytical tools to the participants in the Cape Flats High School intervention. The concurrent presentation of empirical and theoretical sources is based upon Vygotsky's method of double stimulation.

Critical incidents, troubles, and problems in the work practice are recorded and brought into Change Laboratory sessions to serve as first stimuli. This "mirror material" is used to stimulate involvement, analysis, and collaborative design efforts among the participants. (Engeström 2011, 612)

The conceptual tools constitute the second stimulus, and while they are usually introduced by the researcher-interventionist, the Cape Flats High School staff may come up with their own mediating conceptualisations (Sannino 2010). In this research, for instance, staff offered their interpretations of professionalism and this was further developed by myself as the researcher. However, as Sutter (2011) points out, even these roles and processes should be subject to critical examination and redevelopment, although this research did not mature enough for such processes of going "beyond interventionism" to occur.

SOME INITIAL FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

As mentioned above, teaching, management and administrative staff were interviewed to ascertain broadly what some of their main areas of concern were regarding learning and teaching at the school. These concerns served as a starting point for the Change Laboratory sessions in which they, together with the researcher-interventionist, attempt to address challenges facing the school. Thus, for example, during these initial interviews several participants raised the issue of discord among the staff as a factor that severely compromised the school's ability to function optimally. The sentiment was vividly captured by Mr Jay:

Another angle which bothers me is when there is discontent at the school, but none are willing to say anything. They tend to keep quiet. And it kills the school; it destroys the school slowly but surely. It's like you've got a cancer but you don't know you've got the cancer. The cancer is spreading slowly.

This perception was borne out by observations and further interviews that indicated that teachers tended to keep to themselves, preferring to stay in their classrooms during breaks, and keep interactions friendly but superficial. Their reluctance to collaborate seemed to limit the possibilities for developing the projects mentioned earlier, or addressing teachers' concerns, or tackling problematic areas such as students' poor academic performance, discipline and attendance. Instead, school-based initiatives were generally taken up by visiting university students as part of their exchange programme, and operated under the minimal (if any) supervision of one staff member; teachers' concerns were often discussed with a sense of conspiracy; and students' academic performance and behaviour were largely negotiated on a teacher by teacher basis. During another of the initial interviews Ms Kay summed up the situation as follows:

we need to do some staff development - to work around all the changes that have happened at the school; to work around the academics; but mainly to just get some staff unity. We don't have to be friends, but we need to be working together...Since he [the principal] is here there have been little groups at the school and we need to fix that. I think when we can fix that we will be able to move in much bigger strides than we are at the moment.

The above quotations are illustrative of one of the dominant themes arising from the analysis of the initial interviews, namely, that the school environment and ethos were characterised by poor interpersonal and professional relationships among the staff. At this stage the exact nature and reasons for this were not clear, nevertheless, the opinions, emotions and accounts expressed by some of those interviewed established staff relations as a major challenge for the school. The above quotes were therefore presented as part of the mirror material, or first stimulus, in the first Change Laboratory session.

The discussions generated by these selections of interview material were subsequently analysed and the issues which emerged were streamlined into two main areas, namely, leadership and professionalism. A fragment of dialogue is presented below to offer a glimpse into the two hour long session and the analytical process that followed.

Mr Ell: The comment that I am making does not necessarily relate back here, but I know that, from my experience at other schools, sometimes, when the things are implemented, there may not be.. .people may not feel that they are part of that decision. You know, when something gets implemented people may feel (shrugs).. .there isn't that buy in, as it were. Because there was no opportunity to take ownership of it. But if people are talking about things, and taking decisions, then it's our decision and it's easier to.. .But I don't think I've been here long enough to say if that is true here.

Ms Emm: ConsultationL.No it's just that.. .I always heard that (unclear) many years ago. "You didn't consult us. We weren't consulted." So it goes right over the years.

Mr Jay: Like for example.. .if you talk about consulting the colleagues...when.. .for example in the school there is a particular day when there is a meeting. As you said there are different types of leadership. Whether you lead from within, you don't lead outside the group, when you lead outside the group, you give instructions: "This must be done! That must be done! That must be done!" You see? Then that creates that crack with the leadership style and the colleagues. And now.meetings are a big part as a source of debate. You suggest this thing, and then you debate, and then we come to the conclusion. Right? But if there is a lacking in meetings, or (the meetings) tend to be 10 minutes or 5 minutes, then you rush...to get to the decision, and then that also creates that division and that discontent between the management and the staff. So, as you said, if there's a platform...if a platform has not been created, there will be that...er... contradiction...that will lead to the disjointment of the staff...because that one versus that one. So if we create those platforms you are referring to, that's where we can - in those platforms -that's where we debate.

The above excerpts show how the participants quickly assimilated the empirical and theoretical information presented at the session and thereby identified the challenge as a structural problem, that is, that the existing forum for addressing school-related issues is inadequate. As Mr Kay contends, the absence of staff meetings, or the way in which they are carried out means that the platform for dialogue between teachers and management, or staff generally, is ineffective. Lasky (2005, 902) alludes to some socio-cultural perspectives on these concerns:

To be able to work together effectively, however, necessitates having shared understandings, values, and goals. These are developed through sustained contact in which individuals participate in joint-productive (Vygotsky, 1962) or co-joint (Dewey, 1938) activities. Doing things together over time creates the conditions for people to develop shared meaning, norms, values, goals (Cole, 1985; Rogoff, 1990; Tharp & Gallimore, 1988), emotional understanding, and emotional intersubjectivity (Denzin, 1984). It is in day-to-day routines and structures that a shared sense of culture and community develops in schools, especially within secondary school departmental units (Siskin, 1994).

It therefore seems apparent that collaborative relationships do not simply offer the added advantage of creating a pleasant work environment. Rather, in schools they are key to shaping the normative and practical aspects behind the institutions' traditions and so too their successful functioning. About this Mausethagen is clear: "Relational trust within the school community is considered highly important for advancing organizational change and, thereby, contributing to student learning" (2013, 18). As indicated by the findings, some of which are presented here, the teachers recognised that establishing and strengthening collaborative relationships was key to a successful reform process at the school, which is why, in the first Change Laboratory session they called for building stronger networks among themselves and developing an appropriate forum for engaging as colleagues. The symbolic and material tools for realising these emerging ideas were mobilised through the Change Laboratory process. The theoretical modelling involved elaborating the concepts of professionalism and connectivity which had emerged from the Change Laboratory discussions and aligning them with Reeves's (2010) notion of professional learning as relational. In particular, the ideas of social spaces and networks were adapted to accommodate the emphasis on mediation as advocated by cultural-historical activity theory. From this perspective, the platform or meeting space proposed by the teachers constitutes a mediational tool that could facilitate cooperative engagement among staff.

The material facet of the tools, as suggested by the researcher-interventionist, would involve practical measures such as, redesigning the staff room to include a tea-station with cups, crockery and cutlery, seating arrangements that encourage interaction, a large notice board to publicise and spread information and a resource cabinet with documents, booklets, pamphlets, video and other materials relating to teachers' professional practice. The intention behind these "things" is to populate the social space of the staff room in such a way as to establish or recreate connections to a variety of resources that will enable the staff to develop new modes of activity in the meeting space. In light of the observations that meetings are not usually an engaging affair, the suggested introduction of the above-mentioned artefacts is intended to afford a more attractive space for formal and informal exchanges. Additionally, developing protocols such as having specifically allocated time slots for meetings, with sufficient time, an accepted format that allows for constructive debate, a record of the discussions, etcetera, would not only create a professional environment, but also, as Mr Jay suggests, minimise the potential for misunderstandings, divisions and uncooperativeness among staff. An appropriately structured space may therefore encourage new forms of engagement among subject teachers, heads of departments, the disciplinary committee, and so forth, or facilitate access to information and resources from the education department, non-governmental organisations, or the community.

Organisationally, the new tools, both theoretical and material, carry with them the intention of producing an environment that encourages staff interaction and perhaps also an alternative approach to management and leadership through the use of "soft power". Wang and Lu (2008, 425) describe soft power as "the ability to shape what others want by being attractive. This attractiveness rests on intangible resources, such as culture, ideology, and institutions". Thus, rather than overtly imposing its authority, the school leadership could employ strategies of positioning that "operate to channel relations among people as well as relations among ideas in ways that encourage the appropriation of institutional motives" (Eddy Spicer 2013, 8). This move constitutes a shift from a culture of bureaucracy to an appeal to professionalism which additionally draws together the issues of leadership and professionalism under a relational conceptualisation of power, as is clear from the following:

Collective meaning making through soft power operates through networks of social and epistemic relations that reflect a wide variety of strategies of control, manifested in interaction by the range of patterns of positioning available to participants. (Eddy Spicer 2013, 8)

The concept of soft power thus augments the existing tools developed by the Change Laboratory leading to the further evolution of the theoretical and practical aspects of the intervention.

The seemingly simple changes to the way that social spaces are modelled, as well as how they are "peopled" and "thinged" (Reeves 2010) has the potential to radically alter teachers' and management's relationships with each other and with the school's resources, and in so doing, ultimately change educational traditions at the school as well. The idea is that the transformation of these traditions can be effected through the evolution of the group's meditational tools:

tools usually reflect the experience of other people who tried to solve similar problems earlier and invented or modified the tool to make it more efficient or effective. Their experience is accumulated in the structural properties of tools, such as their shape or material, as well as in the knowledge of how the tool should be used. Tools are created and transformed during the development of the activity itself and carry with them a particular culture - the historical evidence of their development. (Kaptelinin and Nardi 2006, 70)

The contention is therefore that changing educational traditions involves a process of enculturation that inscribes new and/or different relationships between people and "things". Sellman's research with peer mediated conflict resolution in schools seems to support this view when it claims that

the frequent shortcomings of peer empowerment programmes such as peer mediation can be explained by a school's failure to modify traditional activities to incorporate the new rules, means of dividing labour and mediational artefacts/tools produced. (Sellman 2011, 58)

It is therefore postulated here that, should significant educational change be desired, it can best be achieved by understanding and addressing the activity system's network of historically and materially situated resources and connections. For instance, in their research with teacher clusters, Jita and Mokhele (2014) report a number of benefits arising from the creation of such collaboratively structured spaces for teachers' professional development. They conclude that building networks among teachers showed both product benefits such as enhanced content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge, as well as process-oriented benefits such as developing longer term cooperation, local capacity for curriculum guidance and more opportunities for teacher leadership. De Villiers and Pretorius (2011) also agree that collaborative relations empower educators and strengthen their development as a community. In terms of the research at Cape Flats High School these findings suggest that developing networks in such a manner, and the benefits that it accrues, constitute a change in tradition for most teachers and schools where "isolation and 'closing the classroom door' are often the norm" (Jita and Mokhele 2014, 8). Moreover, promoting the primacy of relationships in knowledge-making processes challenge conventional hegemonic ideas of individually situated, cognitive notions of knowledge making and affirms marginalised and alternative epistemologies that are generally more relational (Botha 2014).

Contradictions and challenges should also be expected from the creation of these new modes of activity, as the study by Edwards, Lundt and Stamou (2010) shows. Their examination of interprofessional collaboration between educational and welfare practitioners found that the spaces which emerged for these engagements tended to accentuate boundaries on the basis of varying roles and expertise, and operating within them often required rule-bending and the introduction of new, boundary-crossing actors. Their conclusion therefore resonates with the emerging findings from the Cape Flats High School which emphasise the importance of change through meditational means, while also cautioning that the relational aspect of a school's development should be viewed "as an additional layer of expertise; by that we meant that the know-who aspects of relational agency cannot replace a know-what, why and-how knowledge base" (Edwards et al. 2010, 42).

Overall, then, it is argued here that the more subtle approach of focusing on relationships and the manipulation of symbolic and material artefacts may be more effective in engaging the agency of teachers in educational change. Such an approach involves connecting teachers with spaces, tools and colleagues that afford the desired change in practices and behaviour at schools, rather than bombarding them with reforms from above. In this way, both the initiative for change as well as opportunities for decision-making and collaborative leadership at the school are enabled by a network of artefact-mediated relationships that redistribute power in less hierarchical ways.

CONCLUSION

The research described above is situated in an approach to learning that views formal education as complicit in the reproduction of social inequalities, especially in a context like South Africa where authorities are not innovative about addressing the limitations and potentials of its economically poor, linguistically diverse and epistemologically non-Western citizens. It therefore agrees with Spaull when he states: "Until such a time as the DBE and the ruling administration are willing to seriously address the underlying issues in South African education, at whatever political or economic cost, the existing patterns of underperformance and inequality will remain unabated" (2013, 9). Yet, as demonstrated by the staff of Cape Flats High School, while they are aware of the challenges pertaining to their profession, teachers are also frustrated with the constant reforms (Pretorius 2014).

The Change Laboratory, however, is intended to offer a means of developing conceptual and practical responses to systemic problems through an appropriately informed intervention that partners the capacities of both the practitioners and researchers in a field. Moreover, a more substantial impact can be made to an activity system like a school and beyond by reconfiguring tools and relationships in the way that the intervention does. From a relational perspective, teachers' ability to utilise, adapt or create objects, spaces and connections with people and other elements of their activity system positions them as powerful keepers and constructors of educational traditions. Thus, while it may seem that the crisis in South African education, as reflected by schools such as Cape Flats High, is one deeply rooted in social, economic and epistemological inequalities that are beyond the scope of the kind of intervention demonstrated by this research, it is not the case. Despite its small scale, the Change Laboratory is compatible with, and offers several strategic advantages for, an agenda of radical educational transformation. Firstly, it avoids the difficulties associated with a sudden restructuring of the system because it progressively alters the participants' relationships to existing actors and artefacts within the system by expansively developing concepts and modes of activity that are practically and theoretically able to embrace the envisioned goals for change.

Furthermore, given its contextualisation within a historicised process of change, the Change Laboratory presents a practical, bottom up, means of understanding and influencing educational traditions. As a future-oriented project situated in past and present realities, it seeks to change the activity of learning through a conversation that brings together often contradictory elements of the system. As Engeström and Sannino (2010) show, the expansive processes of change that drive the Change Laboratory trace their theoretical roots to Marxist dialectics, suggesting that the changes it seeks to introduce are more than adaptations in response to narrowly conceived problems. Rather, the Change Laboratory exploits systemic contradictions to produce an empowering tool that simultaneously embraces individual and collective agency so that even as it orients itself toward systemic change, it does so through the relations developed by people and their cultural artefacts. Simply put, while the changes initiated at the Cape Flats school may appear to be about furniture in the staff room, the process and effects of the changes are in fact aimed at instituting new forms of mediated activity, not only for the school, but at the level of epistemology as well.

In summary, we see how power relations could be reconfigured in several of the interrelated arenas encompassed by the project. Firstly, typical researcher-researched relations were disrupted by the methodology. Secondly, alternative, counterhegemonic epistemological principles were promoted by the artefact-mediated relational model which foregrounds relationships in the knowledge-making processes of the school activity system. A third arena of change was that of management, in which synergistic forms of engagement and leadership were forwarded in an effort to restructure top-down leadership processes. These changes have the potential to reconstruct the school in fundamental ways with teachers having the opportunity to plug into the above-mentioned arenas and drive the professional project from a resourced, informed and differently empowered position. It is therefore not unforeseeable that, given the opportunity, the research interventions at the school would eventually direct themselves more explicitly toward larger social challenges faced by schools such as Cape Flats High and consequently also broader educational contexts within South Africa.

That is not to say that the Change Laboratory and DWR in general are without their limitations and criticisms. These are too complex and extensive to elaborate here, though, hence I will refer to Kontinen (2013, 107) who summarises some of the literature on them as follows:

the use of the concept of contradiction (Langemeyer 2006), the insufficient analysis of power relations (Blackler 2009; Kontinen 2004; Silvonen 2005), the undialectical misconceptions of societal practice in terms of local activity systems and missing the complexity of human practice (Langemeyer and Roth 2006), as well as the overall observation of developmental work research being a managerial technique of improving work processes to best serve the interests of capital, rather than a transformative practice (Avis 2009; Daniels and Warmington 2007). Moreover, losing the link between Marx's Capital and the analysis of concrete work activities is said to bring "bourgeois sociology to Marx" (Jones 2009, 50).

Kontinen further suggests several of Antonio Gramsci's concepts as having the potential to address these shortcomings with respect to DWR's capacity for accommodating societal complexities and for broadening the socioeconomic location of its interventions. One such notion, that of dialectical pedagogy, entails the dialogical development of "common sense" experiential knowledge with the theoretically informed knowledge of traditional intellectuals, to produce workers (in this case, teachers) as organic intellectuals, as well as new processes and relations of research (Kontinen 2013). I believe this resonates with what I have suggested here, which is that, through the concepts of "relational agency" (Edwards 2005), mediation (Kaptelinin and Nardi 2006) and the reconfiguration of social spaces (Reeves 2010), among others, the Change Laboratory can challenge current hegemonic traditions that structure how knowledge and organisational power are distributed within the schools. It does so by introducing meditational tools that emphasise and reconfigure the relationships that teachers have with each other, knowledge-producing artefacts, organisational tools, decision-making procedures, and so forth.

Finally, if serious changes are to be made in our schools and to our education systems, then perhaps they should start with our traditions of research. Instead of treating teachers and other practitioners in our educational institutions as the problems and targets for research and reforms, we could be forging new sets of relationships between them and the research community - the kind that offer a wider range of tools to both communities.

In the context of a global knowledge-based economy, where the nature of knowledge and work is rapidly changing, appropriately connected teachers and researchers could make up a formidable team as some of the society's most significant producers and reproducers of knowledge. Together with a network perspective, the Change Laboratory therefore offers these knowledge-makers the opportunity to position themselves as the shapers of our epistemological traditions.

REFERENCES

Allen, D. K., A. Brown, S. Karanasios, and A. Norman. 2013. "How Should Technology-Mediated Organizational Change Be Explained? A Comparison of the Contributions of Critical Realism and Activity Theory." MIS Quarterly 37 (3): 835-54. [ Links ]

Borgatti, S. P., and P. C. Foster. 2003. "The Network Paradigm in Organizational Research: A Review and Typology." Journal of Management 29 (6): 991-1013. [ Links ]

Botha, L. R. 2014. "Liberating Education: A Dialectical Approach to Knowledge Diversification." Sosiologisk Årbok 1: 131-57. [ Links ]

Breidlid, A. 2013. Education, Indigenous Knowledges, and Development in the Global South: Contesting Knowledges for a Sustainable Future. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bush, T., R. Joubert, E. Kiggundu, and J. Van Rooyen. 2010. "Managing Teaching and Learning in South African Schools." International Journal of Educational Development 30 (2): 162-68. [ Links ]

Carroll, K. K. 2014. "An Introduction to African-Centered Sociology: Worldview, Epistemology, and Social Theory." Critical Sociology 40 (2): 257-70. [ Links ]

Chisholm, L., and B. Chilisa. 2012. "Contexts of Educational Policy Change in Botswana and South Africa." Prospects 42 (4): 371-88. [ Links ]

De Villiers, E. D., and S. G. Pretorius. 2011. "Democracy in Schools: Are Educators Ready for Teacher Leadership?" South African Journal of Education 31 (4): 574-89. [ Links ]

De Witte, H., S. Rothmann, and L. Jackson. 2012. "The Psychological Consequences of Unemployment in South Africa." South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 15 (3): 235-52. [ Links ]

Eddy Spicer, D. H. 2013. "'Soft Power' and the Negotiation of Legitimacy: Collective Meaning Making in a Teacher Team." Mind, Culture, and Activity 20 (2): 150-69. [ Links ]

Edwards, A. 2005. "Relational Agency: Learning To Be a Resourceful Practitioner." International Journal of Educational Research 43 (3): 168-82. [ Links ]

Edwards, A. 2011. "Learning How To Know Who: Professional Learning for Expansive Practice between Organizations." In Learning across Sites. New Tools, Infrastructures and Practices, edited by S. Ludvigsen, A. Lund, I. Rasmussen and R. Säljö, 17-32. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Edwards, A., I. Lunt, and E. Stamou. 2010. "Inter-Professional Work and Expertise: New Roles at the Boundaries of Schools." British Educational Research Journal 36 (1): 27-15. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y. 2011. "From Design Experiments to Formative Interventions." Theory and Psychology 21 (5): 598-628. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y., and A. Sannino. 2010. "Studies of Expansive Learning: Foundations, Findings and Future Challenges." Educational Research Review 5 (1): 1-24. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y., and A. Sannino. 2011. "Discursive Manifestations of Contradictions in Organizational Change Efforts: A Methodological Framework." Journal of Organizational Change Management 24 (3): 368-87. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y., J. Virkkunen, M. Helle, J. Pihlaja, and R. Poikela. 1996. "The Change Laboratory as a Tool for Transforming Work." Lifelong Learning in Europe 1 (2): 10-7. [ Links ]

Gettier, E. 1963. "Is Knowledge Justified True Belief?" Analysis 23 (6): 121-23. [ Links ]

Goodson, I. 2003. Professional Knowledge, Professional Lives: Studies in Education and Change. Philadelphia: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Guest, A., and B. Schneider. 2003. "Adolescents' Extracurricular Participation in Context: The Mediating Effects of Schools, Communities, and Identity." Sociology of Education 76 (2): 89-109. [ Links ]

Halpin, D., A. Moore, G. Edwards, R. George, and C. Jones. 2000. "Maintaining, Reconstructing and Creating Tradition in Education." Oxford Review of Education 26 (2): 133-14. [ Links ]

Hermansen, H., and M. Nerland. 2014. "Reworking Practice through an AfL project: An Analysis of Teachers' Collaborative Engagement with New Assessment Guidelines." British Educational Research Journal 40 (1): 187-206. [ Links ]

Jita, L. C., and M. L. Mokhele. 2014. "When Teacher Clusters Work: Selected Experiences of South African Teachers with the Cluster Approach to Professional Development." South African Journal of Education 34 (2): 1-15. [ Links ]

Kaptelinin, V., and B. A. Nardi. 2006. "Activity Theory in a Nutshell." In Acting with Technology: Activity Theory and Interaction Design, edited by V. Kaptelinin and B. Nardi, 29-72. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Kerosuo, H., Y. Engeström, and A. Kajamaa. 2010. "Promoting Innovation and Learning through Change Laboratory: An Example from Finnish Health Care." Central European Journal of Public Policy 1: 110-31. [ Links ]

Kontinen, T. 2013. "A Gramscian Perspective on Developmental Work Research: Contradictions, Power and the Role of Researchers Reconsidered." Outlines. Critical Practice Studies 14 (2): 106-29. [ Links ]

Lasky, S. 2005. "A Sociocultural Approach to Understanding Teacher Identity, Agency and Professional Vulnerability in a Context of Secondary School Reform." Teaching and Teacher Education 21 (8): 899-916. [ Links ]

Mausethagen, S. 2013. "A Research Review of the Impact of Accountability Policies on Teachers' Workplace Relations." Educational Research Review 9: 16-33. [ Links ]

Moore, A., G. Edwards, D. Halpin, and R. George. 2002. "Compliance, Resistance and Pragmatism: The (Re)Construction of Schoolteacher Identities in a Period of Intensive Educational Reform." British Educational Research Journal 28 (4): 551-65. [ Links ]

National Committee for Research Ethics in Science and Technology (NENT). 2008. Guidelines for Research Ethics in Science and Technology. http://www.etikkom.no/English/Publications/NENTguidelines (accessed March 6, 2014).

Prenkert, F. 2010. "Tracing the Roots of Activity Systems Theory: An Analysis of the Concept of Mediation." Theory and Psychology 20 (5): 641-65. [ Links ]

Pretorius, S. G. 2014. "An Education System's Perspective on Turning Around South Africa's Dysfunctional Schools." Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5 (15): 348-58. [ Links ]

Provincial Economic Review and Outlook (PERO). 2013. Cape Town: Western Cape Government Provincial Treasury.

Ratele, K. 2014. "Currents against Gender Transformation of South African Men: Relocating Marginality to the Centre of Research and Theory of Masculinities." NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 9 (1): 30-44. [ Links ]

Reagan, T. G. 2004. Non-Western Educational Traditions: Indigenous Approaches to Educational Thought and Practice. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Reeves, J. 2010. Professional Learning as Relational Practice. London: Springer. [ Links ]

Samoff, J. 2008. "Bantu Education, People's Education, Outcomes-Based Education: Whither Education in South Africa." In Educational Change in South Africa. Reflections on Local Realities, Practices, and Reforms, edited by E. Weber, ix-xvi. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Sannino, A. 2010. "Teachers' Talk of Experiencing: Conflict, Resistance and Agency." Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (4): 838-44. [ Links ]

Sellman, E. 2011. "Peer Mediation Services for Conflict Resolution in Schools: What Transformations in Activity Characterise Successful Implementation?" British Educational Research Journal 37 (1): 45-60. [ Links ]

Soudien, C. 2007. "The 'A' Factor: Coming to Terms with the Question of Legacy in South African Education." International Journal of Educational Development 27 (2): 182-93. [ Links ]

Spaull, N. 2013. South Africa's Education Crisis: The Quality of Education in South Africa 1994-2011. Johannesburg: Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE). [ Links ]

Sutter, B. 2011. "How To Analyse and Promote Developmental Activity Research?" Theory and Psychology 21 (5): 715-23. [ Links ]

Wang, H., and Y. C. Lu. 2008. "The Conception of Soft Power and Its Policy Implications: A Comparative Study of China and Taiwan." Journal of Contemporary China 17 (56): 425-47. [ Links ]

1 Not the actual name of the school.

2 In apartheid terms, "African" and "coloured".