Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.21 n.1 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/490

ARTICLES

The meritocratic ideal in education systems: the mechanisms of academic distinction in the international context

Leonor Lima TorresI; Maria Luisa QuaresmaII

IUniversidade do Minho. leonort@ie.uminho.pt

IIUniversidad Autónoma de Chile. quaresma.ml@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The state school lives immersed in the tension between democratic purposes and the ideals of merit and selectivity. In this context, state schools establish instruments of public praise for students who stand out academically or in other dimensions. we propose to map the rituals of academic distinction in Portuguese state schools and to discuss the widespread adoption of these mechanisms by secondary schools. However, neither their configuration nor the selection criteria are homogeneous, which points to the existence of distinct conceptualisations of excellence and margins of freedom for each school to define their own criteria for success.

Keywords: excellence; academic distinction; state school

INTRODUCTION

As the advancement of neoliberal policies in education intensifies on a global scale, we are witnessing the reappearance of a debate concerning the mission of the state school. Although historically this concern constitutes a political regularity, in recent years the debate of the role of the school and the nature of its strategic objectives has intensified. Several research groups, especially European and American, have been focusing on a dilemma that prioritises democratic and meritocratic mandates in the state school. Although the configuration of these mandates is the result of the specificity of national contexts and their broader historical and political traditions, it becomes possible to identify certain common features that regulate education systems. The increasing pressure for the production of results stands out visibly as a dominant idea in the varied studies regarding the subject, although with distinct manifestations in different social contexts.

In the specific case of Portugal, school organisations experience a double constraint: on the one hand, conditioned by educational policies of a managerial inspiration and, on the other hand, pressured by families and local communities to promote educational success. This simultaneous and convergent movement (top-down and down-top) has been gradually reconfiguring the priorities of the school, pushing them towards the increasingly assumed appreciation of values such as efficiency, excellence and performativity, and leaving its inclusive and democratic mission in the shadows. The clearest expression that we are facing a "radicalisation of the neo-meritocratic mandate" (Afonso 2013) is the extended adoption in several schools of the practice of distinguishing the best students - a foretaste that "on est ainsi entré dans une culture anxieuse du résultaf [we are, therefore, entering a culture eager for results] (Baudelot and Establet 2009, 9).

Integrated into a broader research project,1 this article aims to highlight the amplitude and degrees of the practices of academic distinction in schools and school groups of secondary education. A phenomenon so recent it tends to be overlooked, the rituals of academic distinction display multiple manifestations imbued with symbolic value in the process of socialising young generations in a strongly performative culture. Based on the assumption that the academic distinction rituals and practices constitute a mechanism of organisational management endorsed by logics of meritocratic nature, we will analyse, in the first section of this article, some theoretic-conceptual perspectives that explore the tense relationship between democratisation, meritocracy and educational success.

In the second section of the article we present an overview of international approaches with the aim of mapping some practices implemented in countries whose educational policies, due to the degree to which they have been absorbed by the accountability system, are essentially centred on the performances of schools and students, and influence school systems, as is the case with Portuguese schools. The United States of America is relevant because of its centrality in the international scene, as a result of the preponderance of its accountability model in educational policies of democratic and republican governments (Figlio and Loeb 2011), and due to its strong meritocratic tradition. The United Kingdom, "a social laboratory of experimentation and reforms" (Ball 2013, 1), is also relevant because of the centrality assumed by the neoliberal principles of mercantilism, management and performativity. Finally, France is an important case of analysis because its cultural and institutional tradition is closer to the Portuguese one. Moreover, due to the effect of a strong centralised power, France has also supported the accountability processes in a more moderated manner than other countries with higher levels of decentralisation, of which England is a paradigm (Broadfoot 2000).

In the third section, we will focus the analysis on the context of the Portuguese reality, showing the range, extension and specificities of these ceremonials as fostering mechanisms of school merit. This paper primarily explores approaches to the phenomenon and, consequently and essentially, an exploratory and descriptive register will be adopted.

The data concerning the international context was gathered from research in the educational and sociological fields of the three chosen countries (United States, United Kingdom and France). It was also compiled through the analysis of information that was obtained directly from primary sources: on a macro-level, such as governmental reports and relevant news in social communication media, and on the meso organisational level, such as educative projects in schools with prominent recognition practices. The data regarding the Portuguese reality is based on the content analysis of structuring documents of schools with secondary education, complemented with the observation of their webpages and the analysis of news published by the media. The analysis of a total of 490 institutions with secondary education resulted in the consultation of approximately 1500 documents, with the aim of identifying the type of academic distinction prevailing in the Portuguese state school.

DEMOCRATISATION, MERITOCRACY AND SUCCESS

In recent years, school excellence has been the imperative in public policies regarding education, especially in education systems that are strongly concerned with qualities, competence and merit and the efficacy of the education system. In Europe, the priority is the development of competence in the education system, regulated by the interests and needs of the labour market, and by efficient and performative government methods (Ball 2002). The emphasis on the production of school results involved the reconfiguration of the mission of state schools, so that they were progressively more dependent on students' academic performance and accountability (meritocratic mandate) and less implicated in the consolidation of democratisation in school processes (democratic mandate). As some countries have been fighting school failure and dropout, the "qualities of success" are intensified, in a clear apology to the cult of meritocracy (Dench 2006; Duru-Bellat 2009; McNamee and Miller 2004).

Within this macro-structural context, the Portuguese school system has been developed under the fundamental dilemma induced by this agenda: on the one hand, the preservation of the democratic values of the public education system (equality, inclusion and citizenship) and, on the other hand, the endorsement of multiple devices of control, of result monitoring and the rationalisation of resources. Although still far from consolidating its democratising function, the public school struggles with the implementation of school management inspired by the principles of the new public management. In addition, education systems implement other political measures, which are exemplified in the introduction of national examinations at the end of every cycle, the curricular reformation in basic education, the separation of grades according to academic performance, the institutionalisation of internal and external assessment processes of schools, the publication of academic results under ranking systems and the stimulus of school selection freedom. Instead of the achievement of academic success in a multidimensional manner, the achievement sought is academic results of excellence.

At the centre of the scientific debate, we can find different approaches regarding the objectives of the public education system: those that seek to explore the potentialities of a school organisation focused on the values of efficiency, excellence and competence; those that question the meritocratic postulates which only stimulate academic achievements; and, finally, those that defend a reconciliation between the democratising dimensions and the meritocratic principles.

Inspired by the effective school movement (Brookover, Bready, Flood, Schweitzer and Wisenbanker 1979; Rutter, Maughan, Mortimer, Ouston and Smith 1979) and the thesis regarding the school effect and the establishment effect, some theoretical perspectives analyse the importance of organisational factors (weather, culture, leadership, pedagogic organisation) in the production of academic results in different spheres: academic (success), professional (teachers' pedagogic performance), organisational (school management), and cultural (school identity). The diversity of research developed in this field of analysis is not just a reflection of the influence of the predominant political agenda, but its results have been reflected in the expansion and legitimisation of education policies directed towards academic achievements.

On the other hand, as meritocratic ideals have acquired centrality in the different countries of Western Europe, several studies have questioned the apparent consensus generated by this educational agenda, emphasising the "disillusionment of meritocracy" (Duru-Bellat 2006), "merit versus justice" (Duru-Bellat 2009), or the meanings of the meritocratic equality of opportunities (Dubet 2004, 2010, 2014). The studies conclude that there is a narrowing of the mission of the public school, acting at the level of the reproduction of (new) social inequalities.

In America, the work Equity and Excellence in Education: Towards Maximal Learning Opportunities for All Students (Van den Branden, Van Avermaet and Van Houtte 2011) compiles several studies that seek to delve into the current position of education systems regarding their double mission of promoting inclusion and, at the same time, excellence. This line of research seeks to show the advantages of the reconciliation of democratic and meritocratic mandates.

Having these three axes of research as reference, we aim to analyse, in the following sections, the manner in which rituals of academic distinction are put into practice in different national contexts and how they articulate meritocratic dimensions; in other words, if these rituals privilege exclusively performative practices (distinction based on results), if they predominantly value the civic and democratic dimensions (distinction based on values), or if they combine the social dimensions and academic performance (mixed distinction). We propose to inquire into whether rituals of distinction are restricted to a single conceptualisation of achievement (academic success), or if they encompass a broader conceptualisation, based on social, cultural and civic dimensions (educational success).

PRACTICES OF DISTINCTION IN THE INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT

United Kingdom

One of the instruments of encouragement of academic distinction established in the English education system is the "Future Scholar Awards", also known as the "Dux Award Scheme". This award, which in 2013 involved nearly 800 schools, has as its target the students who attend the equivalent of the ninth grade (at the age of 14) and who stand out because of their academic results, their ability to improve, their resilience to adversity and their potential to apply for higher education. The selection of the "Dux" (champion in Latin) of each school is conducted by the teachers, and the prize consists of a visit to the premises of the most prestigious universities in England which, in synergy with the British Ministry of Education, promote a kind of open day aimed at raising the expectations of these students and encouraging them to invest in a successful path at the best universities of the country.

The "London Schools Excellence Fund" is another example of a project aimed at supporting initiatives that promote academic excellence. Jointly funded by the central and local governments, this project provides funds so that the schools with the best results can "share their knowledge and expertise with other schools, in order to raise expectations, promote academic rigour and improve the performance of most students" (Greater London Authority 2013) whose efforts and performances should be encouraged and rewarded.

This policy of motivation and reward seems to be part of the ethos of English schools, which, as early as in kindergarten, reward good performance in dimensions as diverse as behaviour, performance, attendance, effort, involvement in extracurricular activities, or civic participation. The students that stand out can be distinguished on a daily basis in a number of ways. Some schools award "merit stickers" - types of stickers that schools can choose from catalogues made available by specialised companies, as is the case with "School Merit Stickers" - others choose to award "stars" (golden stars, platinum stars, etc.) that, when a certain number is earned, grant certificates of merit ("Behaviour Discipline and Rewards Policy" - Chafyn Grove School), while others adopt a point allocation system, which grants "bronze postcards", "silver postcards" or "platinum postcards" when a certain number of points is earned ("Rewards and Sanctions" - Hornsey School for Girls) (Hornsey 2013). There is also the allocation of "letters of praise" and awards at festive events, such as the annual "celebration evenings" (Ringwood 2014). In fact, the academic merit distinction system seems to have a large adherence in British schools, judging by the resulting commodification phenomenon reflected in the emergence of private companies - some with suggestive names, such as the "Carrot Rewards" - that centre on the release and sale of online systems of school awards and incentives to educational establishments: systems "more in the 21st century", according to one of the participating schools ("Vivo Miles at Easingwold School. A Student Guide"), and much more exciting for the students, because of the interactivity they allow compared to traditional procedures. "Vivo Miles", for example, released a product that, although involved in strong controversy, has been adopted by several hundreds of secondary schools (Paton 2013). The system allows students to manage their "meritocratic career" by checking their online profile, where teachers award "points" (Vivos) to reward behaviour. Through the use of their personal electronic card, students can access their accounts. In this way, they can manage the points earned, which can be exchanged for products (iPads, movie tickets, beauty products, etc.) that are available in the company's catalogue, or can be chosen by the respective schools (iPads, sports equipment), or can be accumulated to spend later or to donate to schools in developing countries.

United States of America

The system of incentives and rewards has been implemented in several districts of the United States of America, where schools began to stimulate and reward the good performance of students. Rewards of a varied nature - money, mp3s and even, for younger students, Happy Meals sponsored by a fast food chain (Elliot 2007) - are given to students who are distinguished by good academic results, good behaviour or attendance (Raymond 2008). But it is at the charter schools that the system of incentives/rewards has a longer tradition, as Raymond (2008) states in a study that explores how it is applied in these schools. Based on a survey of 250 schools in 17 states in the United States, he concluded that 57 per cent of the 186 participants adopt this type of programme. About 40 per cent use a system of points that can be converted into prizes, and about 25 per cent use "negative incentives" (2008, 6) by removing points from the total accumulated. Almost all of these schools (93%) reward the academic performance (fulfilling school tasks, grades, attendance, etc.), and the conduct of the students (behaviour in the classroom, relationship with adults, citizenship, relationship with colleagues, effort, etc.), which is under constant evaluation in approximately half of the schools (44.15%). The number of schools that only value the academic dimension (4 schools) or only the behavioural dimension (3 schools) is residual. The most frequent prizes awarded include participation in activities, offered by 82.1 per cent of the schools surveyed, granting certificates of merit (63.2%) and providing stationery items, such as pens and diaries (53.8%). Monetary rewards (8.5%) are rarer, due to the financial constraints of schools (Raymond 2008). Although controversial, these programmes have attracted the attention of some researchers, such as Fryer (2011), whose conclusions on their impact on the performance of students require, however, a more in-depth investigation (Center on Education Policy 2012).

In addition to these school initiatives, since 1983 the US Education Department also promotes incentive programmes for academic distinction and school merit, which include, among other awards, certificates and letters of praise signed by the highest figure of the American State. Such is the case with the "President's Education Awards Program", designed to distinguish, by proposal of the school directors, the students in the elementary, middle, and high school who stand out because of their school performance, and the "President's Award for Educational Achievement" for those students who "show outstanding educational growth, improvement, commitment or intellectual development in their academic subjects but do not meet the criteria for the President's Award for Educational Excellence" (US Department of Education 2015).

France

France has not escaped the social pressure regarding the academic performance and efficiency of the education system to produce results, and it was during the presidency of Sarkozy that the concerns involving academic excellence obtained prominence. During his term, the internats d'excellence were created, schools under boarding school regime that aim to give opportunities to "meritorious" students from working-class backgrounds (Rayou and Glasman 2012) through the opportunity of attending a school that guarantees the ideal conditions to develop their academic potential. Noting the recurrence of expressions such as "merit" and "potential" in the official documents regarding the internats d'excellence, Rochex (2011) relates the existence of a supremacy involving "the logic of individualizing and maximizing the opportunities of self-realization" (2001, 880) that is detrimental to a collective logic of fighting against inequality. From a strictly psychological angle, this perspective centres on individual factors of excellence, such as the "gift", the "talent" and the "effort", which illustrate the meritocratic nature of French education.

The implementation, in 2013, of a "National Day of Academic Success" and the establishment of an "Observatory for Academic Success" destined to promote the exchange and cooperative work between all participants involved in the construction of success, are equally representative of the importance given by ministry policies to the matter of academic qualities, recognised as a "great national cause" by the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, which justify wide mobilisation.

France's Ministry of Education's webpage displays, effectively, that the internal regulations of schools consider rewarding those students who stand out because of the quality of their developed school work or even because of their demonstrated effort.

According to this source, the rewards are registered in a dossier for each student, and may assume different configurations: to "encourage", "congratulate" or even to be distinguished in the "Honour Roll". A non-exhaustive search in the regulations of some French schools and an enquiry into some Chartes des conseils de classe show the Honour Roll has a minor presence relative to the other countries. Schools and academies seem to have margins of autonomy in this area. Thus, some establishments specify the general averages required to receive some distinctions, such as in the case of College Noël de Montville, but this is not the case in other schools. Additionally, in some establishments, such as College Max-Dussuchal, the celebration of merit is transformed into a public ceremony where every member of the educational community and even the press are invited.

It is noteworthy that the local press attributes great relevance to these moments that recognise excellence: "The school retakes traditions and rituals", or "Wittmer school - the school celebrates success", are some of the examples of news headlines, always accompanied by photographs depicting the events.

Another mechanism of distinction, with a long tradition in France, is related to the prestigious Concours Général des Lycées et des Métiers. Founded in the eighteenth century, this academic competition endorses rewarding and praising the best students from the last two years of humanist, technical and professional schools who, after being selected by their teachers according to academic merit, display excellent performance in high demanding national tests. The presence of the Secretary of Education in the awards ceremony that recognises excellence confers higher solemnity to this prestigious event.

POLICIES AND MECHANISMS OF ACADEMIC DISTINCTION IN THE PORTUGUESE CONTEXT

The Portuguese educational reality was not immune to the logic of competitiveness and performativity that became a priority during the 1980s on the international educational agenda and that highlighted the concerns regarding excellence, merit, school results and assessment (Palhares and Torres 2011). The creation of Honour Boards of Excellence and Value (Quadros de Excelência e de Valor), by the Legislative Order no. 102/90 is an important example of this ministerial approach to the issues of excellence and school merit. Two decades later, these devices are established as "student rights" in the Statute of the Student and School Ethics (Estatuto do Aluno e Ética Escolar) (Law no. 51/2012, of the 5th of September).

At a time when the Portuguese school had not yet fully satisfied the democratic mandate that it set out, the theme of academic excellence entered the agenda, with the Honour Boards of Excellence and Value being created and regulated by the Ministry of Education - the first intended to recognise students who "show excellent results at school and produce academic work or carry out activities of excellent quality, both in the curricular domain and the curricular supplements domain" (Chapter I, Article 3), and the second intended to recognise those who "show great skills or exemplary attitudes in overcoming difficulties or that develop initiatives or actions, also exemplary, with a clear social or community benefit or of expression of solidarity, in school or out of it" (Article 2). At the same time that it regulates these Honour Boards, this Order serves the purpose of establishing the promotion of merit and encouraging schools of different cycles and also the Regional and General Education Directions to promote this type of instrument of academic distinction, which can, as the law provides, take the form of Honour Boards of Excellence and Value at a school, at regional or national level.

At national level, we saw the creation of Honour Boards to reward students who figured in the respective regional Honour Boards in the third cycle of basic education and cumulatively in secondary education. The prizes, the responsibility of the promoting entities, should be chosen by taking into consideration their "eminently educational function" and their goal to "encourage the continuation of school commitment, the overcoming of difficulties and the spirit of service" (paragraph 2, Article 8, Chapter III).

At the regional level, the possibility of also creating Honour Boards of Excellence and Value is open to the education directors, being determined by the Order that these are intended to reward students who, at the end of each study cycle, over several years of the schooling cycle, remained within the Honour Boards of Excellence or Value of the respective school.

In the educational establishments, the drawing up of the respective regulations is assigned to the Pedagogic Councils,2 also responsible for choosing those responsible for the application proposals and the respective evaluations, which, in the case of the Honour Boards for Excellence, must comply with a minimum requirement that the Order makes a point to establish: an average grade of five in the subjects or subject areas of basic education, weighted by the weekly workload, or an average grade of 16, also weighted, in the case of secondary education.3

The context is therefore one of increasing focus on the performance results (Afonso 2009), transformed in the alpha and the omega of national concerns. At the centre of attention is, from the outset, the performance of students, in the crosshairs of both those nostalgic for the "school of excellence" of the past, who cry out against the alleged lower academic level, and the political decision-makers, who over the years abuse the "diversity (sometimes ephemeral and inconsistent) of public policies for the promotion of school inclusion" (Quaresma 2011, 200) of the new audiences brought to the school by the democratisation of education. But at the centre of attention is also the performance of teachers and schools.

Alongside this focus on results emerges what Afonso (2009) considers to be fragmented forms of accountability, requested not only from the students but also from the teachers and the school organisations themselves. The Portuguese public educational policies are shaped by this logic of accountability. According to Afonso (2009), it is visible, for example, in the submission of students to standardised tests (national and international), the evaluation of teachers and educational institutions - both depending on the belief of the "teacher effect" and "school effect" on the improvement of learning - or even in the regime of autonomy and school management, which is described in the legal norms as a synonym for "greater responsibility, regular accountability and assessment of performance and results" (Portugal 2005, 44). The autonomy of the schools, which begins by being inscribed in a logic of democratisation to ensure "the power, the resources and capacity of collective decision necessary to the democratic functioning" (Barroso 2004, 74), will eventually become captive of the pressures for efficiency, particularly in terms of the improvement of academic results, which international studies, such as the Pisa 2010, positively correlate with school decentralisation.

METHODOLOGICAL DESIGN

With the purpose of identifying the types of academic distinction, formally provided for in the universe of Portuguese schools, a methodological design was defined, anchored in two strategies: the first, more descriptive, focused on a survey of the state schools with secondary education (n = 490); the second strategy, essentially interpretative, focused on the collection and analysis of structuring documents produced by schools (n = 1500), complemented with the observation of their webpages and the analysis of the news published by the media. In addition, the guiding documents - educational projects, annual plans of activities, internal regulations and intervention plans from the Director - and the reports of external evaluation and the 2012 and 2013 rankings of all secondary schools, prepared and published by the media, were also analysed. The corpus of information was the object of the content analysis operationalised from a registration grid in Excel format and, subsequently, transposed into the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software.

The confrontation between the formal-legal plan and the established practices required, at a later point in time, the definition of a sample consisting of 335 schools (corresponding to 68% of the school universe), encompassing the regions of the country with the highest number of schools providing secondary education. At this stage, we aimed to obtain empirical evidence to establish the type of practices of academic distinction which were effectively put into place in the school organisations. The primary focus of the analysis was on the various forms of exposure of the academic distinction rituals, on the projection which these practices had in the media and on how they have been highlighted in the external evaluation reports.

The compilation of a wide variety of information regarding the universe of the organisations under study allowed for the identification of general trends and the recognition of specificities regarding the impact of educational guidance of meritocratic tendencies.

THE PRACTICES OF ACADEMIC DISTINCTION PLANNED IN THE PORTUGUESE SCHOOL ORGANISATIONS

The study performed in the context of the Portuguese reality points towards a significant adherence of school institutions to the adoption of practices of academic distinction of their best students. Even though these devices are regulated since 1990, it has been found that not all schools (5.9%) contemplate these practices in their guiding documents. Furthermore, we point out the presence of this ritual in the overwhelming majority of schools (91.7%), although in different formats and different forms of operationalisation.

From the analysis performed on the extensive corpus of information, it was possible to identify three types of academic distinction focused on different dimensions of learning: a) in the academic results, b) in the values and behaviours, and (c) in the results and in the values and behaviours (mixed academic distinction). Table 1 shows a clear trend for the increase of mixed academic distinction, with around 70 per cent of the schools placing it formally in their strategic action. Although only 16.5 per cent of schools formally provide a kind of academic distinction exclusively focused on results, in reality, when we contrasted the formal-legal plan with the practices effectively imposed, this value increased exponentially (see Torres, Palhares and Borges 2014). As we will see, a closer analysis of the introduced and advertised practices reveals the presence of a meritocratic ideology in the process of school socialisation.

Within the framework of these three forms of performance rewarding, schools make use of different mechanisms of academic distinction, in some cases reproducing what is laid down in the legislation, in other cases, introducing other ways, perhaps more adjusted to the educational purposes of the institution. Table 2 shows the variety of the mechanisms existing in schools according to the type of planned academic distinction. We see a preference for the implementation of the Honour Boards of excellence (focused on the weighted average of the internal grades obtained in the various subjects) combined with the Honour Boards of value (focused on behaviours and attitudes), thereby obtaining the status of mixed academic distinction. It should be noted that the most common criterion for the integration of students in the Honour Boards of excellence consists in obtaining internal grades exceeding 17.5, although, from the formal-legal point of view, the minimum condition for application is set at 16 (Legislative Order No. 102/90, Article 5, paragraph 5).

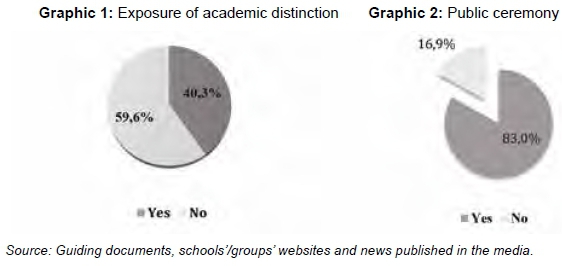

The analysis of the information contained in the electronic portals of the schools helped to understand the institutional importance given to the practices of academic distinction, deduced from their presence and prominence in terms of public exposure. Thus, from the total number of schools that formally joined this practice, approximately 40.3 per cent depicted it in their portal, in many cases in a prominent position and it remained for a long time in the "news" section. It is known that the advertising of the institutions works as a device of trust (Queré 2005) which, in this case, means transmitting to the parents the message that the school is committed to the values of meritocracy and excellence. Through this strategy, schools attract students of those socio-economic, academic and motivational profiles that can help the school to attain a good positioning in the school rankings.

The vast majority of schools that implement practices of academic distinction hold a public ceremony to present the awards and diplomas (83%), with the presence of students, parents and guardians, representatives from the local community and, in many cases, the media. In spite of the compliance with this ritual, as a general rule, the format and the symbolic charge conferred by the school community to this moment is different, as it can be held at the end of a school day, or be strategically performed during an entire day, framed by various initiatives and events and culminating with the ceremony of delivering awards or diplomas to the best students.

Although preliminary, these initial findings stress the importance that the mechanisms for the praise of merit and civic behaviours have been gaining in the most varied school contexts, as well as the diversity of devices put into action to achieve the recognition of excellence. It is important, now, to assess the extent of this (neo)meritocratic orientation at the level of the Portuguese school system.

THE PRACTICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE RITUAL

In order to understand the practices of academic distinction effectively imposed in the schools, we moved, in a second part of the study, to a comparison of the formal provisions contained in guiding documents with their actual implementation in school contexts. This comparison of the planned and the practised confirmed a clear preference for academic distinction that focuses on academic results and the devaluation of the mixed academic distinction category. In a sample consisting of 335 schools, the following trends were identified: a) 39.4 per cent of the schools/groups effectively implement a mixed academic distinction (substantially less than what was identified in the formal plan, 73.4%); b) 48.1 per cent distinguish students exclusively based on their academic results, a percentage substantially different from the 18.2 per cent that stated it in their guiding documents; c) 2.4 per cent do not implement any type of academic distinction; d) only 1.2 per cent implement an academic distinction focused exclusively on the values/ behaviours of the students. The discrepancy between the high percentage of schools that uniquely distinguish the academic dimension - almost half of the sample - and the small percentage (1.2%) that uniquely distinguish the values/behaviours, reveals that the schools subordinate key areas for the integral training of students (Tedesco 2007) in comparison with the production of academic results, in a logic of instrumentality driven by the "competitive interdependencies between schools" (Maroy 2007, 89).

The multiplication of the rituals of academic distinction and their progressive anchoring in academic results indicate a shift in the direction of the sense of purpose of state schools, now furthest away from the democratising project (Duru-Bellat 2009; Laval 2004; Magalhães and Stoer 2002). In an increasingly performative society, the production of results tends to be a strong mechanism for regulating the education system and, in particular, a strategic priority of a large portion of schools/groups. The analysis of the educational projects and contingency plans of the directors evidences, unequivocally, the incorporation of the meritocratic agenda. Illustrative of this trend is the use of a diversified lexicon to designate the mechanisms of academic distinction established in these organisations. Among the dozens of expressions recorded in the documents analysed, the concept of merit appears with great emphasis, revealing in many cases that the priority of the school is effectively focused on the promotion of results of excellence, making use of various mechanisms of academic distinction: grants, diplomas, endorsements, titles, certificates, praises. In fact, the idea of Ball (2002, 15) is strengthened when he states that "the requirements of performativity dramatically prevent the 'metaphysical discourses', the relationship of the practice with philosophical principles, such as social justice and equity". Against this background, the right of the student to get recognition for the "commitment in praiseworthy actions, in particular the voluntary work in favour of the community in which he/she is inserted, or the society in general, practiced at school or outside of it, and be encouraged in that sense" (Law no. 51, 2012), is challenged by a competitive performativity that hovers over the educational field.

By multiplying the strategies to encourage the promotion of academic excellence and the objective of developing talents, skills and performative knowledge, the school exerts a powerful effect as a context of socialisation for young students, as recent studies have demonstrated (see Daverne and Duterq 2013; Tenret 2011). The processes of ritualisation and praise of merit - ever more common and immersed in symbolism -constitute one additional regulating pillar of the school with obvious repercussions for the development of the performative obligations of students.

CONCLUSIONS

The initiatives to promote school excellence and the academic distinction of the best students seem to establish themselves as an integral part of the international educational reality. As has been demonstrated through the compilation - non-exhaustively, however - of data stemming from multiple information sources at the macro level, such as the ministries of education, and at mid-level, such as educational projects from schools, countries like the United States of America, the United Kingdom and France - in other words, countries whose educational systems have influenced the structuring of the Portuguese system - have adopted diverse strategies and mechanisms of distinction to reward the best students. Thus, the countries heavily marked by the accountability system, which has extensively influenced the organisation of the educational system in a global manner, such as the United States of America and the United Kingdom, rely on the involvement of schools and even the national and local authorities to distinguish students of excellence through awards such as access to the "open days" of some of the most prestigious universities in the country, diplomas of merit, or mere Happy Meals. The appearance of numerous private companies in the English market that promote and target schools' systems of prizes and merit incentives in a manner that is "more in the 21st century", is proof of the vitality of these practices of academic distinction, which have found in the "online world" an added factor of attractiveness and stimulation for the new generations.

In those countries with less centralised education systems that are less marked by privatisation and the principles of accountability, such as France and Portugal, the mechanisms of distinction and appraisal of merit are visible, although not presenting, as in the case of English-speaking countries, a commercial side.

According to the obtained results regarding the Portuguese context, the overwhelming majority of schools and schools' groups of secondary education distinguish the best students in different ways. From the point of view of formal guidance, it is apparent that most schools adhere to academic distinction of a mixed type. By rewarding academic results and the values and behaviours of students, the mixed type academic distinctions suggest that a holistic conceptualisation of education (at a rhetorical level) is currently widespread in most state schools. This has been identified in several studies as an identity trace from the elites and their educational institutions (Mension-Rigau 2007; Pinçon and Pinçon-Charlot 2007), which has however moved beyond these social and school areas, partly due to the demands of society, where the family has lost its socialising role, and the demands of the economy, whose production models require, in order to be competitive, professionals with profiles of "complete individuals" (Tedesco 2007).

Regarding the mechanisms of academic distinction, the Honour Boards of Excellence and the Honour Boards of Value prevail in Portuguese schools. With the objective of rewarding, respectively, the academic dimension and the values and behaviours dimension, these are, after all, the result of the democratic reformulation of the traditional honour boards of the high schools from before the revolution of 25 April 1974, which brings bad memories to many Portuguese people by evoking a link between schools and fascism and, according to Cunha (1997), by identifying schools as an instrument "reductionist in its objectives, ideological in its requirements, elitist in its results" (1997, 103).

However, the confrontation between the rhetorical level and the effective practices opened up new interpretative challenges by confirming the preference for academic distinction focused on academic results and, consequently, the devaluation of the social, behavioural and attitudinal merit evidenced by students. In a clear impoverishment of its mission, the school neither pursues the wider goals of education, nor meets the broad needs of the society (Boyle and Charles 2011; West and Ylönen 2010).

It should also be noted, in the majority of schools, the ceremonies to present these prizes and awards to the best students are moments of state praise of merit, whose symbolic meaning is strengthened by the presence of the entire educational community, the families and also the representatives of local government and, in many cases, the press.

The meritocratic ideal finds this ritualisation of academic distinction to be a valuable ally for its dissemination and internalisation, as well as for the promotion of the social image of the school, each time more concerned with academic success and each time more distant from educational success.

REFERENCES

Afonso, A. 2009. "Nem Tudo o que Conta em Educação É Mensurável ou Comparável. Crítica à Accountability Baseada em Testes Estandardizados e Rankings Escolares." Revista Lusófona de Educação 13: 13-29. [ Links ]

Afonso, A. 2013. "Estratégias e Percursos Educacionais: das Explicações às Novas Vantagens Competitivas da Classe Média." InXplica internacional. Panorâmica Sobre o Mercado das Explicações, edited by J. A. Costa, A. Neto-Mendes and A. Ventura, 167-88. Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro. [ Links ]

Ball, S. 2002. "Reformar Escolas/Reformar Professores e os Terrores da Performatividade." Revista Portuguesa de Educação 15 (2): 3-23. http://josenorberto.com.br/BALL.%2037415201.pdf (accessed April 10, 2014). [ Links ]

Ball, S. 2013. The Education Debate. 2nd ed. Bristol: The Policy Press. [ Links ]

Barroso, J. 2004. "A Autonomia das Escolas: Uma Ficção Necessária." Revista Portuguesa de Educação 17 (2): 49-83. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37417203 (accessed March 25, 2013). [ Links ]

Baudelot, C., and R. Establet. 2009. L'Élitisme Républicain: L'École Française à l'Épreuve des Comparaisons Internationales. Paris: Editions du Seuil. [ Links ]

Boyle, B., and M. Charles. 2011. "Education in a Multicultural Environment: Equity Issues in Teaching and Learning in the School System in England." International Studies in Sociology of Education 21 (4): 299-314. doi: 10.1080/09620214.2011.638539 [ Links ]

Broadfoot, P. 2000. "Un Nouveau Mode de Regulation Dans un Systeme Décentralisé: L'État Évaluateur." Revue Française depédagogie 130 (1): 43-55. [ Links ]

Brookover, W., C. Beady, P. Flood, J. Schweitzer, and J. Wisenbaker. 1979. School Social Systems and Student Achievement: Schools Can Make a Difference. New York: Praeger. [ Links ]

Center on Education Policy. 2012. Can Money or Other Rewards Motivate Students? Washington: The George Washington University. [ Links ]

Cunha, P. O. 1997. "Excelência e Qualidade em Educação." In Educação em Debate, edited by P. O. Cunha (coord.), 83-11. Lisboa: Universidade Católica Editora. [ Links ]

Daverne, C., and Y. Duterq. 2013. Les Bons Élèves: Experiences et Cadres de Formation. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Dench, G., ed. 2006. The Rise and Rise of Meritocracy. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Department of Education. 2015. President's Education Awards Program: U.S. Department of Education. http://www2.ed.gov/programs/presedaward/applicant.html (accessed January 20, 2016).

Dubet, F. 2004. L'École des Chances. Qu'est-ce qu'UneÉcole Juste? Paris: Editions du Seuil. [ Links ]

Dubet, F. 2010. Les Places et les Chances : Repenser la Justice Sociale. Paris: Editions du Seuil. [ Links ]

Dubet, F. 2014. La Préférence pour L'Inégalité. Comprendre la Crise des Solidarités. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. [ Links ]

Duru-Bellat, M. 2006. L'Inflation Scolaire : LesDésillusions de laMéritocratie. Paris: Editions du Seuil. [ Links ]

Duru-Bellat, M. 2009. Le Mérite Contre la Justice. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po. [ Links ]

Elliot, S. 2007. "Straight A's, With a Burger as a Prize." The New York Times, December 6. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/06/business/media/06adco.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1& (accessed January 20, 2016).

Figlio, D., and S. Loeb. 2011. "School Accountability." In Handbook of Economics of Education. Vol. 3, edited by E. Hanushek, S. Machin and L. Woessmann, 383-121. The Netherlands: North-Holland. [ Links ]

Fryer, R. 2011. "Financial Incentives and Student Achievement: Evidence from Randomized Trials." Quarterly Journal of Economics 126 (4): 1755-798. http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/fryer/files/financial_incentives_and_student_achievement _evidence_from_randomized_trials.pdf (accessed April 30, 2014). [ Links ]

Greater London Authority. 2013. "Mayor Unveils Multi-Million Pound Investment to Drive Up Teaching Standards." https://www.london.gov.uk/media/mayor-press-releases/2013/10/mayor-unveils-multi-million-pound-investment-to-drive-up (accessed June 13, 2015).

Hornsey School for Girls. 2013. "Reward Points and Sanctions." http://www.hsg.haringey.sch.uk/about-us/school-expectations/reward-points-and-sanctions/ (accessed June 13, 2015).

Laval, C. 2004. L'école n'est pas une entreprise. Le néo-libéralisme à l'assaut de l'enseignement public. Paris: Éditions La Découverte Poche/Essais. [ Links ]

Magalhães, A. M., and S. R. Stoer. 2002. A Escola Para Todos e a Excelência Acadêmica. Porto: Profedições. [ Links ]

Maroy, C. 2007. "Les Modes de Regulation de L'École. Une Comparaison Européenne." Revue Internationale d'Education de Sèvres 46 : 87-98. [ Links ]

McNamee, S., and R. Miller Jr. 2004. The Meritocracy Myth. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Mension-Rigau, E. 2007. Aristocrates et Grands Bourgeois. Paris: Perrin. Editions Plon. [ Links ]

Ministére de l'Éducation Nationale. 2013. "Observatoire de la Réussite." Dossier de Presse. http://cache.media.education.gouv.fr/file/07_Juillet/66/8/Mise-en-place-Observatoire-de-la-reussite- educative_262668.pdf (accessed June 13, 2015).

Palliares, J. A., and L. L. Torres. 2011. "Governação da Escola e Excelência Acadêmica: As Representações dos Alunos Distinguidos Num Quadro de Excelência." Sociologia da Educação - Revista Luso- Brasileira 2 (4): 54-75. [ Links ]

Paton, G. 2013. "Reward Scheme for Schoolchildren 'Encouraged Gambling'." The Telegraph, January 4. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews/9781316/Reward-scheme-for-schoolchildren-encouraged-gambling.html (accessed June 13, 2015).

Pinçon, M., and M. Pinçon-Charlot. 2007. Sociologie de la Bourgeoisie. 3rd ed. Paris: La Découverte. [ Links ]

Portugal. 2005. Programa doXVIIGoverno Constitucional (2005-2009). Lisbon: Presidência do Conselho de Ministros. http://www.portugal.gov.pt/pt.aspx (accessed February 10, 2013).

Quaresma, M. L. 2011. "Democratização da Escola: Perspectiva Diacrônica Sobre os Mandatos Escolares." In Democratização e Educação Pública: Sendas e Veredas, edited by F. Lima and others, 190-216. San Luis: EDUFMA. [ Links ]

Queré, L. 2005. "Les 'Dispositifs de Confiance' dans L'Espace Public." Réseaux 132 (4): 189-217. doi: 10.3917/res.132.0185 [ Links ]

Raymond, M. 2008. Paying for A 's: An Early Exploration of Student Reward and Incentive Programs in Charter Schools. http://credo.stanford.edu/downloads/paying_for_a.pdf (accessed June 13, 2015).

Rayou, P., and D. Glasman. 2012. Les Internats D'Excellence: Un Nouveau Défi Éducatif? http://centre-alain-savary.ens-lyon.fr/CAS/internats/rapport-sur-les-internats-dexcellence-octobre-2012 (accessed March 25, 2014).

Ringwood. 2014. "Ringwood School Behaviour Policy." http://www.ringwood.hants.sch.uk/resources/Behaviour-policy-September-2013.pdf (accessed April 30, 2015).

Rochex, J.-Y. 2011. "As Três Idades das Políticas de Educação Prioritária." Educação e Pesquisa 37 (4): 871-81. [ Links ]

Rutter, M., B. Maughan, P. Mortimer, J. Ouston, and A. Smith. 1979. Fifteen Thousands Hours: Secondary Schools and Their Effects on Children. London: Open Books. [ Links ]

Tedesco, J. C. 2007. El Nuevo Pacto Educativo: Educación, Competitividady Ciudadanía. Buenos Aires : Ed. Santillana. [ Links ]

Tenret, É. 2011. L'École et la Méritocratie: Representations Sociales et Socialization Scolaire. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Torres, L. L., J. A. Palhares, and G. Borges. 2014. "Roteiro da Excelência na Escola Pública Portuguesa: Tendências Normativas e Conceções Dominantes." In Atas do- Espaços de Investigação, Reflexão e Ação Interdisciplinar, edited by M. J. Carvalho, A. Loureiro and C. A. Ferreira, 480-94. http://xiicongressospce2014.utad.pt/ (accessed December 10, 2015).

Van den Branden, K., P. Van Avermaet, and M. Van Houtte, eds. 2011. Equity and Excellence, Towards Maximal Learning: Opportunities for All Students. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

West, A., and A. Ylönen. 2010. "Market-Oriented School Reform in England and Finland: School Choice, Finance and Governance." Educational Studies 36 (1): 1-12. doi: 10.1080/03055690902880307 [ Links ]

1 This work is financed by National Funds through the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Foundation for Science and Technology) within the framework of the project PTDC/IVC-PEC/4942/2012 of the Centre for Research in Education of the University of Minho (CIEd), entitled Entre Mais e Melhor escola: A excelência acadêmica na escola pública portuguesa (Between More and Better School: Academic Excellence in the Portuguese State School)

2 The Pedagogical Council is responsible for the pedagogical coordination and supervision, as well as the educational guidance, of the school group or school not pertaining to a group, in particular in the pedagogical-didactic domains, the guidance and monitoring of students and the initial and continuous training of the teaching and non-teaching staff. The Pedagogical Council meets ordinarily once a month and extraordinarily whenever convened by the respective president, on his/her own initiative, at the request of one third of its members in effectiveness of functions or when a request for an opinion of the general council or the director is justified. The composition of the Pedagogical Council is established by the school group or school not pertaining to a group in accordance with the respective rules of internal procedure, and shall not exceed the maximum of 17 members (see Articles 31, 32, 33 and 34 of the Decree-Law no. 75/2008, of the 22nd of April).

3 In basic education, the grades are distributed on a scale of 1 to 5, and in secondary education from 1 to 20.