Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 n.3 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/1533

ARTICLES

Teachers as agents of change: promoting peacebuilding and social cohesion in schools in Rwanda

Jolly RubagizaI; Jane UmutoniII; Ali KaleebaIII

IUniversity of Rwanda Email: rubagiza@yahoo.com

IIUniversity of Rwanda Email: jumutoni2001@yahoo.com

IIIUniversity of Rwanda Email: kaleebaa@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Education is seen to play a crucial role in the reconstruction of post-conflict countries, particularly in transforming people's mindsets and rebuilding social relations. In this regard, teachers are often perceived as key agents to bring about this transformative change through their role as agents of peace. This paper seeks to understand how teachers are positioned to promote peacebuilding and social cohesion in Rwandan schools in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. The paper draws on data collected for an on-going broader study researching the role of teachers in peacebuilding in post-conflict contexts of Rwanda and South Africa. The methods used for data collection were semi-structured interviews, focus-group discussions, questionnaires and classroom observations. Theoretically the paper is informed by the broader research framework on sustainable peacebuilding in post-conflict situations, using the four dimensions of recognition, redistribution, representation and reconciliation (4Rs). The findings show that the policy environment is conducive to peacebuilding and recognises the important role of teachers and education in general, in the social, political and economic reconstruction of post-genocide Rwanda. However, there are a number of interrelated factors that pertain to teachers' professional development, teacher management and the school environment that pose challenges to sustainable peacebuilding and social cohesion.

Keywords: teachers; Rwanda; peacebuilding; social cohesion

INTRODUCTION

Education is generally considered to play a critical role in the reconstruction of post-conflict countries, especially in transforming people's mindsets and rebuilding social relations. Efforts to increase access to education are sometimes a crucial feature of post-conflict recovery, not only in restoring a sense of normality, but also at times to act as a deterrent approach to address inequalities that may aggravate conflicts among people in that society. Education therefore serves as an avenue for inculcating values and attitudes in students, teachers and community members to promote reconciliation and social cohesion (UNICEF 2011).

Along with education come teachers, who worldwide are conceptualised in various ways and thus expected to play multiple roles to address different social problems. Often teachers are perceived as agents of transformative change, including being agents of peace. In societies that have been affected by conflict, teachers are seen to play a key role in nation building, identity construction and peace and reconciliation (Durrani & Dunne 2010; Smith et al. 2011). As agents of peace, teachers are expected to impart values that espouse peace including tolerance, recognition and respect, and a range of skills such as critical thinking, negotiation, compromise and collaboration as well as model interpersonal relationships among learners (Horner et al. 2015). In the same vein, Barrett (2007) posits that what teachers do with the available learning resources shape what young people learn, influence their identities, and provide them with skills for employment and peacebuilding. According to Dladla and Moon (2013) teacher training is seen as a fundamental component of post-conflict reconstruction, but they also assert that at times there are doubts about both the relevance and effectiveness of the training offered. However, Gardinier (2012) argues that most times, no effort is made to understand how teachers are able to navigate and respond to the competing pressures around them and the complexity of their relationship with various actors including students, parents and administrators.

This article seeks to understand how teachers are positioned to promote peacebuilding and social cohesion in Rwandan schools in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. Below we start by providing a brief context.

POST-CONFLICT EDUCATION IN THE RWANDAN CONTEXT

Rwanda is a country whose people have experienced a painful past that came as a result of ethnic divisions and discrimination that culminated in the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. This tragedy virtually left all institutions destroyed and the education sector was no exception. The country found itself faced with enormous challenges on how to rebuild the material, moral and social fabric of the society. The government committed to key strategic goals in an effort to reconstruct the country, which included national unity and reconciliation, economic growth and poverty reduction. Education was seen as a key driver for national development in pursuit of these three goals (Ministry of Education 2003). 'The government believes that education should be aimed at recreating in young people the values which have been eroded in the course of the country's recent history' (ibid, 4). It was imperative therefore that all human potential be mobilised in an effort to reconstruct the country. In this regard, the teacher's role was seen as crucial in moulding the young people into responsible citizens with employable skills for the labour market (Republic of Rwanda 2000).

Education in Rwanda in the past was characterised by injustices based on ethnicity, regionalism, gender, and religious discrimination, all of which could have contributed to the 1994 genocide (Rutayisire et al. 2004). As a way to address this, equality and nondiscrimination in education have been given particular emphasis. This is reflected within the general objectives of education as stated in the Education Sector Policy (ESP), in particular the general objective that seeks 'to eliminate all the causes and obstacles which can lead to disparity in education be it by gender, disability, geographical or social group' (Ministry of Education 2003, 17). The post-genocide education policy has prioritised national unity, reconciliation, and equal access and has encouraged a culture of inclusion and mutual respect. The first major change made in this regard was outlawing the institutionalisation of ethnic classification and the quota system (Iringaniza), which was the basis for student recruitment into secondary and higher education (Rutayisire et al. 2004). Most people saw this policy that defined quotas for different regions, ethnic groups and gender for transition from primary to secondary school as a systematic way for the education system to discriminate against certain groups of people (ibid).

To address inequalities cited within education in the past, an effort has been made to expand access to education at all levels, and in particular to basic education, as reflected in programmes such as the Nine Years Basic Education Programme and most recently the Twelve Years Basic Education Programme. For example, net enrolment rates at primary level stood at 96.3 per cent for boys and 97.4 per cent for girls in 2015 (Ministry of Education 2015). However, expanded access to education has not come without challenges: teachers contend with large classrooms with an average of 60 students per class at primary level (Ministry of Education n.d.), with most schools still practising double shifting in levels P1-P3. Shifting means that the large classes at this level are divided into two - one group attends in the morning and the other in the afternoon with the same teacher. This creates an extra burden on the teacher. In the same vein, teaching and learning resources are limited, especially in rural schools. This largely affects teacher motivation and morale and has an impact on the quality of education offered.

Apart from expanding access to education for all, and at all levels, deliberate effort has been made to address the inequalities of the past through the recognition of specific groups. For instance the 'Girls Education Policy' (2008) was put in place to promote education for women and girls. Accordingly, various forms of affirmative action to increase girls' access to and participation in secondary and higher education and in non-traditional fields of study, particularly science, mathematics and technology have been implemented with tangible results. However, gender gaps remain in higher education, especially in public higher institutions of learning, where enrolment rates for female students stood at 31.9 per cent in 2015 (MINEDUC 2015).

The Education Sector Strategic Plan (2013-2017) affirms the right to education for vulnerable children, including adolescent girls, children with disabilities, children living with HIV and children from poorer backgrounds (MINEDUC 2013). It is as well emphasised in the Rwandan Constitution that every Rwandan has the right to education and the state has the duty to take special measures to facilitate the education of disabled people (GoR 2003). Consequently, the Special Needs Education Policy (2007b) stresses the establishment of education programmes that promote the inclusion of minorities and people with disabilities in mainstream education. Nonetheless, the implementation of these policies still poses challenges, largely due to limited funds compared to the large numbers of vulnerable children.

As a way to address the injustices of the past and to develop new relationships and trust among Rwandans, the government of Rwanda chose the path of unity and reconciliation. This was seen as a means through which peace, safety, and respect of human rights and in particular the right to life could be restored in Rwanda (Rutayisire et al. 2004). The creation of the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) early on in 1999 was seen as an important step to end the legacy of discrimination based on ethnicity, religion, gender and regionalism, and to ensure both the transition out of violence and hatred among Rwandans, and the consolidation of peace (ibid, 350).

The NURC is an autonomous body and works with all sector ministries, in particular the Ministry of Education. Through its department of Civic Education, the commission works closely with the Ministry of Education to promote civic values, unity and reconciliation within the school system through participating in curriculum development and teacher training. Apart from the NURC other institutions, like the National Itorero Commission (NIC) and the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide (CNLG), also work closely with the Ministry of Education to impart Rwandan values that promote peace and social cohesion, and fight against the genocide ideology among teachers and students.

There have been debates and criticism about promoting national unity that embraces being 'Rwandan' as opposed to ethnic difference. Perhaps it is important to note that Rwanda's cultural setting is far removed from that in most neighbouring countries, composed of many ethnic groups with diverse languages and cultures. Language is known to be a key unifying factor in any cultural setting. Rwandans speak one common language known as 'Kinyarwanda' and share the same culture and customs regardless of their ethnicity. As Ponorac (2010) observes, 'language is culture and culture is language'. There have even been debates on whether the categories Hutu, Tutsi and Twa in Rwanda should be seen as ethnic groups or social groups since these categories were not fixed in the past (Kanimba & Mesas cited in Buckley-Zistel 2009; Rutayisire et al. 2004). Fixed ethnicity was introduced in National Identification Cards by Belgians during years of colonisation in order socially to construct two separate Rwandan races, which thus imposed conflicting fixed identities (Nardone 2010, 6). Since then, although Rwandans were viewed and viewed themselves with an ethnic lens, today most (95.6%) take pride in their national identity, according to a study carried out by the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission in 2015.

METHODOLOGY

As highlighted before, this article seeks to understand how teachers are positioned to promote peacebuilding and social cohesion in Rwandan schools in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. The article draws from a broader study - a research project funded by the ESRC/DFID Joint Fund for Poverty Alleviation to research the role of teachers in peacebuilding in post-conflict contexts in Rwanda and South Africa. However, this article specifically draws from field data gathered from teachers in fourteen case study schools and teacher training institutions (ITEs) where the project operated; these include primary and secondary schools and also teacher training colleges (TTCs). Among these are private, semi-private and public schools, and ITEs from the five regions in Rwanda (northern, southern, eastern, western and Kigali City). Data were collected through the use of semi-structured interviews, focus-group discussions, teacher questionnaires and classroom observations. The teachers interviewed were those teaching Social Studies, English language, History and Citizenship, and General Paper, and teaching at Primary Four and Five, Senior Two, Senior Four or Senior Five. This was in line with the subjects and class levels sampled for the larger research project. This article also draws from individual interviews carried out with policymakers and other stakeholders in education.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

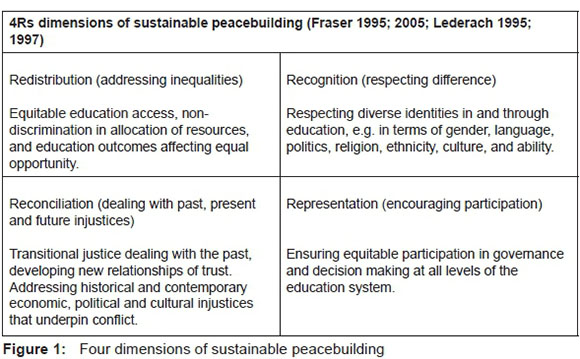

Theoretically this article is informed by the framework adopted by the broader research project to explore sustainable peacebuilding in post-conflict education environments. The four dimensions of Recognition, Redistribution, Representation and Reconciliation (4Rs), linking the work of Nancy Fraser (1995; 2005) on social justice and the peacebuilding and reconciliation work of Galtung (1995) and Lederach (1995; 1997), are employed.

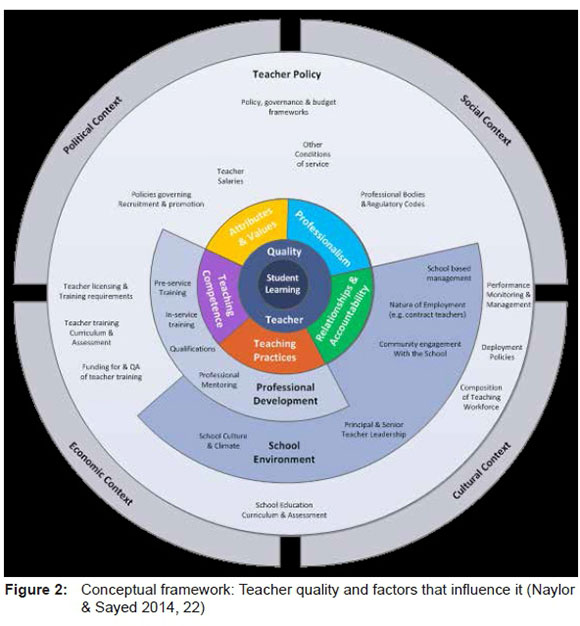

Figure 1 above explains the 4Rs and how they will be used in this article. More specifically the conceptual framework on teacher quality of Naylor and Sayed (2014), below, is used to understand how various elements influence teacher quality; different factors such as the government teacher policy framework (teacher governance, recruitment and deployment, teacher remuneration), teacher professional development (pre-service and in-service/CPD), school environment (school physical facilities, teaching and learning resources, teacher workload) and others are interrelated and influence teacher quality in a given context. Consequently, this impacts the teacher's role in promoting peacebuilding and social cohesion.

TEACHERS AS AGENTS OF TRANSFORMATIVE CHANGE

In examining the role ofteachers as agents ofchange, whether in promoting peacebuilding, social cohesion, or any other area, it is important to recognise that in any education system, teachers' capacities to effect change are both strengthened and limited by the prevailing structural conditions (Naylor & Sayed 2014). Consequently, in exploring the relationship between teachers and peacebuilding in this article, we take into account the wide range of factors relevant to teaching - the social, cultural, economic and political context in which they operate as construed from the conceptual framework (Naylor & Sayed 2014) described above.

Teacher policy context

Teacher education policies in Rwanda, like most policies, are informed by the national development plans and strategies, such as Vision 2020, the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategies EDPRS 1&2, the Education Sector Strategic Plans and others. Vision 2020, the key policy-guiding document for Rwanda's development recognises the important role of the teacher in shaping young Rwandans into responsible citizens and in equipping them with employable skills required for the labour market. It also acknowledges that the decline in the quality of education is largely due to the low calibre of teaching staff, and therefore the policy commits the government to offer intensive teacher training programmes (Republic of Rwanda 2000).

In the same vein, the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS 2 2013-18) acknowledges that the knowledge-based economy that Rwanda wishes to build requires a highly knowledgeable and skilled workforce. And such a workforce can only be produced by a quality education system, run by well qualified, motivated, competent and professional teachers (Republic of Rwanda 2013). Furthermore, the Teacher Development and Management Policy (2008) posits that 'the quality and utility value of education depends on the quality and competence of the teaching staff' (Ministry of Education 2007a, 4). In this regard, the teacher is seen as the main instrument for bringing about the desired improvement in learning both in school and in the wider society. The policy commits to strengthen institutional and structural capacities for improving teacher quality in Rwanda.

The Education Sector Strategic Plan, ESSP (2013/14-17/18) will, among other things, prioritise the preparation and recruitment of highly skilled teachers to be able to meet the targeted reductions in teacher-pupil ratios for both primary and secondary school. It is envisaged that targeting both in-service training and professional development, and strengthening the pre-service system will help produce and build a skilled and well-qualified teaching force. In addition to the above, the use of more effective teacher development and management information systems were among the strategies taken to motivate the teaching workforce and to support more efficient teacher recruitment, deployment, promotion and in-service training mechanisms (ESSP 2013/14-17/18). The school-based mentoring programme, however, is one of the sector's innovative approaches to improve the skills of teachers. It focuses on improving both English language proficiency and teaching methodology.

The Rwanda teacher policy framework contains positive commitments to support teachers; stakeholders in education agree that there is a strong link between the motivation of teachers and their performance as can be seen above. Yet as the VSO report on Teachers' Voice in Rwanda (2004) states policies are not a problem, often the problem lies in implementation, particularly where policies are not implemented as they were set out or implemented in a timely manner.

Furthermore there was a general feeling among participants in this study that teachers' participation in educational policymaking is minimal, notwithstanding the crucial role that they play within the education system. It was acknowledged though that teachers predominantly partake in areas like curriculum development, textbook selection and student placement, but hardly get involved in governance and other key decision making areas of the education sector.

We always say for that. .that teachers wish to be involved in education policy making in Rwanda wherever they are based. Sometimes REB organizes meetings at district level, but of course I cannot confirm that teachers at the grassroots get a chance to have their say. But what we request is to push for more teachers' involvement in decision making, changing policy, changing the curriculum; teachers should be asked their thoughts about this. They should be informed. (Teacher representative at the Rwanda Teachers Union)

As Gardinier (2012) observes, for teachers to become agents of transformational change, they need to become active citizens in the new democracy that seeks to address the injustices of the past. Teacher participation in decision making and preparation to reach these transformative goals is therefore crucial.

Teacher professional development

A number of studies have highlighted the importance of initial teacher preparation for any education system to thrive (Barrett et al. 2007; World Bank 2012). Moreover, teacher preparation and certification is seen as the most important factor for students' learning, especially for low performing students (Darling-Hammond 2000 cited in Naylor & Sayed 2014). Hargreaves and Fullan (1992) concur that teacher professional development involves the formal and informal experiences throughout the teacher's career; all these activities enhance their professional development. As such, trained teachers are vital for quality education. Thus, it is anticipated that teachers who have acquired the knowledge and practical skills, and have the expertise and self-confidence are able to carry out their duties in demanding and complex situations, and also to earn the trust of the stakeholders, their clients and colleagues (Bonnet 2008 ).

According to UNESCO (2011), pre-service teacher training enables future teachers to comprehend educational theories, philosophy, teaching methodologies and educational ethics, whilst gaining social skills, knowledge and competences in different subjects, so as to start a successful teaching career. On the other hand, in-service training is given to teachers who are already working. The aim of in-service teacher training is to improve the quality of teaching among teachers, as well as accustoming new teachers for them to carry out effective teaching and learning. Without the in-service training, teachers' knowledge would become outdated, and they would not be able to cope well with changes and would therefore lose their ability to work effectively and efficiently (ibid). Most of the time, in-service training is offered through short courses, seminars, workshops, meetings and other special training. In-service training is an important factor in supporting teachers to excel in the classroom and to commit to the profession, especially in countries with varied recruitment and initial training policies (Kent 2005 cited in Campbell & Kent 2010).

In Rwanda, primary school teachers are trained in Teacher Training Colleges (TTCs). There are 16 of these TTCs in the country, and all are public or government subsidised schools. The minimum entry requirement is a Secondary School Ordinary (O-Level) certificate and students follow the programme for three years. As such the students are trained to teach either at pre-primary or primary school level upon graduation from the TTCs. However, it has been observed that students who choose the TTC option are those who have not obtained higher grades to be admitted to subject streams that are in highest demand. The same was reported for those who go on to higher education where most enlist for education degrees as a second choice, having failed to qualify for other preferred courses (Bennell & Ntagaramba 2008). Tutors who teach in the TTCs are mainly trained by the University of Rwanda - College of Education (UR-CE) and are required therefore to have a degree in education. The UR-CE is also the main trainer of secondary school teachers in Rwanda. Established in 1999 as the Kigali Institute of Education, the institute was intended to address the shortage of qualified teaching staff at secondary level. At that time up to 65 per cent of secondary school teachers in Rwanda were found to be under-qualified (Ministry of Education 1999). There has been tremendous improvement since then, with the number of qualified teachers at secondary level rising to 69.30 per cent in 2013. Teachers trained at the UR-CE and affiliate colleges offer A1 (Diploma Level) for lower secondary teaching and a Bachelor's Degree for advanced secondary level teaching. The degree is either in arts or science. However there has been some concern that pre-service teacher education in Rwanda remains too academic and theoretical, with most of the lecturers having little or no direct experience of the day-to-day challenges of classroom teaching (Bennell & Ntagaramba 2008).

Nonetheless during an interview with the Principal of the College of Education, it was observed that the college is on the right track as a number of changes are being instituted to make programmes more relevant and practical. For example, the Internship Programme where students now spend a whole year in schools came to replace the two months of Teaching Practice. Furthermore, academic programmes at UR-CE are being adapted to the New Competence Based Curriculum (CBC) that has been rolled out in schools in February 2016. Moreover, it was indicated that the College of Education is the primary avenue for developing a culture of peace. The principal highlighted that one of the modules, called the 'Life Skills in Education' module, incorporates a unit on peace education, to equip students with peace and conflict transformation skills, and to address social and interpersonal conflict in non-violent ways. However, he observed that there are still challenges in getting everyone involved in addressing issues of peacebuilding in their subject areas.

I would say that one of the challenges on the topic of peace building or peace education is to have everyone take responsibility - even if we were to come here (CE), there is the module on life skills education which incorporates peace education. So sometimes the question is this - do we actually see the module team as the only team whose business is peace education? Are we teaching it? So it is the translation of the curriculum into action - in whatever we do. So as much as it (peace education) should have a home, one of the challenges is actually seeing everybody as involved - for example - whether you are talking about mathematics, what is the role of mathematics in peace building, what about physics. (Principal UR-CE, 2016)

The in-service training (INSET) on the other hand remains with the Rwanda Education Board (REB) and involves mainly school-based and off-site training programmes, many of which take place during holiday periods. It offers teachers opportunities for continued professional development. The main INSET programmes at present provide English language training for all primary and secondary school teachers, mathematics and science training for secondary school teachers of these subjects, and learner-centred pedagogy and school management training for head teachers. Instructors are usually REB Teacher Development and Management (TDM) personnel, School-Based Mentors (SBM) and development partners and civil society organisations.

There was a general agreement among most informants that teachers receive training on different aspects but not necessarily on fostering peacebuilding and social cohesion.1 The education officials interviewed pointed out that peace-values education is among the cross-cutting issues that were subsumed in the new Competence Based Curriculum (CBC), but most teachers have not yet been trained on this. Those who have a notion of peacebuilding and social cohesion were probably trained by some NGOs such as the Aegis trust and others.

Indeed during interviews with teachers who participated in this study, most of them decried the lack of continued professional development in general. With regard to peace education, some teachers mentioned that they had received training through the Aegis Trust's Rwanda Peace Education Programme. Incidentally those who said they had been trained were either teaching Social Studies or History and Citizenship, and some of these had received more than one training through the same programme, implying that some teachers may receive multiple trainings under the same programme, while others receive none. In fact, this appeared to raise concern among some teachers who indicated that they did not know what criteria are used to select people for training. Below are some responses from teachers about training received on peace education:

There is a programme here where I am the pioneer. I am the one who was first trained in peacebuilding. The training was conducted by Rwanda Peace Education Programme (RPEP) - it is done through REB and Aegis Trust - I was trained three times by them. (Male teacher at GSM2, 2016)

We don't get any training here. When there is a problem you manage it as an adult. There are no trainings here. No, it (training) doesn't reach all teachers, I don't know why. Sometimes they select a few of them or just one. Those who go for training are supposed to come back and training others, but this does not happen. (Female teacher at GSM2, 2016)

Training has helped me to improve my skills in my teaching activities, in the peace club and in my classes and it has created in me a greater need to build peace even with my fellow teachers and students. (Male teacher at GSM1, 2016)

To me self-esteem and humility are most important. Besides we do not get promoted or get salary increments because of attending training, but I feel confident when I am teaching and even training my colleagues. (Male teacher at WPS, 2016)

From the above responses, it may be deduced that the teachers value in-service training and professional development, even with no salary increment or promotion as an incentive attached to it. According to the VSO (2004) study on teachers' voices in Rwanda, training opportunities were identified as one of the non-salaried incentives, after healthcare, transport and accommodation, that would motivate teachers. However it appears the in-service teacher training at the moment is less systematically organised and more demand driven, once off and offers little reinforcement. Moreover, as it has been reported in the past the teachers were not seen as active participants in their own professional growth (Rutayisire 2008 cited in Bennell & Ntagaramba 2008) since they indicated that they are never consulted on what areas they would like to receive training in. Yet, teacher participation in decisions that affect their profession and lives in general is very crucial in order to avoid teacher apathy and any other forms of injustice; it underpins the tenet of representation in sustainable peacebuilding.

Thus, although in Rwanda teacher professional development is an integral part of the education system, there remain challenges to overcome. Moreover peacebuilding and social cohesion themes seem to be given less attention, although this could improve with the rolled out new CBC. Horner et al. (2015) argue that in post-conflict contexts, it is important to integrate peacebuilding and social cohesion in the continued professional development programmes. Through CPD, teachers can acquire knowledge and skills of fostering social cohesion in their classrooms and across the curriculum. Continued professional development can also empower teachers to ably facilitate the development of peacebuilding and social cohesion skills such as negotiation, problem solving, collaboration, and critical thinking as well as attitudes like, empathy, tolerance and compassion among students (ibid).

Teacher deployment, recruitment and remuneration

In order effectively to foster peacebuilding and social cohesion, it is important to have an equitable education system with minimal teaching staff disparities between and within regions, and also to fairly remunerate teachers.

As has been noted, the government has invested heavily in improving access to basic education, and therefore acknowledges the increased demand of high-quality teachers to deliver quality education. However, due to severe budgetary constraints, the government remains pressured to seek effective and efficient approaches to recruiting and equitably deploying qualified primary and secondary school teachers across the country.

According to the information gathered on the deployment and remuneration of teachers, some key informants revealed that the education system is now decentralised in such a way that the placement of teachers in public schools is supply-based and done at the district level. Teachers and other education personnel are recruited and deployed through a participatory and transparent process. The Director of Education formerly known as the District Education Officer (DEO) and Sector Education Officer (SEO) in collaboration with the head teachers are the ones who recruit teachers based on criteria that include: teacher qualifications and experience, availability of positions, and recognising the possibility for internal re-deployment. Recruitment should be non-discriminatory and based on the results of written and oral exams.

Before decentralization, the Ministry of Education was in charge of recruiting teachers, appointing them, paid them and did the inspection, which I think was impossible to achieve effectively. Because for example, if a teacher in Rusizi (the furthest district from Kigali city) had a problem of payment, he/she would come to Kigali. Today, the district is responsible for everything: recruitment of teachers, appointment, payment of teachers' salaries and others. The central government is basically responsible for disbursement of funds to districts. The district monitors, inspect schools and have the prerogative to dismiss teachers and punish teachers and/ or headteachers. Today a teacher who needs a transfer, e.g. a married female teaching staff at Nyagatare, will request for a transfer from the Director of Education in that area, then he/she sends it to the Mayor to sign and a copy is sent the Ministry of Education. Teachers don't need to go to the ministry to request for transfer. The same applies to the students. A student who wants to move to another school goes to the district and it is done there. (Rwanda Education Board official, 2016)

However, it was observed that although teacher recruitment is done at district level, a number of ministries are directly or indirectly concerned with recruitment due to a stake they have in this, these include the Ministry of Education (the parent ministry for REB), the Ministry of Public Service, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Local Government. Moreover, it was revealed that due to budget constraints, many times REB will impose certain quotas that districts will not go beyond, implying that new teachers are recruited depending on the available budget. As a result, some public schools recruit unqualified teachers who work on short-term contracts and with different working terms, often at substantially less remuneration. This does not only compromise the quality of education, but impinges on the peacebuilding and social cohesion process since such teachers may feel that they are a temporary fix to fill a gap and may eventually be eliminated. Furthermore, we may begin to see more unemployed qualified teachers, even when the government has spent substantially on training them. The quotes below illustrate this point further:

You may find a graduate teacher being sacrificed at the expense of a less qualified teacher because the pay of a graduated teacher is actually almost 3 times that of A2 teachers...And when they want to increase the numbers, you find districts recruiting less qualified teachers, just to fill the gaps with the quotas that are provided. (REB-TDM official 2, 2016)

First of all it has a quality issue. Poor recruitment means poor performance. When you recruit a poor qualified teacher, that's in contradiction against the issue of quality and also the issue of peace. And when we recruit people who are less qualified at the expense of those who are qualified, we are creating a group of unemployed professionals. (REB-TDM official 1, 2016)

Nonetheless the use of unqualified contractual teachers is sometimes seen in a positive light, since they may be more accountable and therefore more effective than the more regular and permanent teachers, especially as a way to sustain their jobs (Kingdon et al. 2014 cited in Horner et al. 2015). Furthermore, it is indicated that the locally contracted teachers have a positive effect on student outcomes not because of their contracts but because they have more local knowledge and are also more accountable to the local community to which they belong (Naylor & Sayed 2014).

However, it was pointed out that although the recruitment process is participatory and transparent, it is not sensitive to gender inequalities and teaching staff discrepancies between rural and urban areas, and this may impact on social cohesion. Bennell and Ntagaramba (2008) observe that 'despite the small geographical size of Rwanda, the spatial distribution of teachers across the country with respect to key characteristics (such as qualifications, experience and gender) is markedly uneven'. The main reason cited for this was the unattractive working and living conditions in many rural schools (ibid, 7).

Some of the participants interviewed were also of the view that the majority of teachers preferred working in Kigali City where they could easily access services. According to them, the further one moves away from Kigali, the poorer the quality gets. It was observed that although some teachers may prefer to work in their districts of origin, after some months they have a tendency to request for transfers to schools in Kigali or in nearby towns. Unfortunately, Kigali City does not have many schools to accommodate all these teachers.

Each and every teacher wants to be a teacher in Kigali city yet Kigali is rated as one of the provinces with very few public schools as well as other schools that operate in partnership with the government. You understand that not all can be in Kigali. So the further you move away from Kigali, the poor the quality of teachers you get. (REB-TDM official 2, 2016)

We would encourage people to go wherever they want to go - of course, very many people want to remain in Kigali - but you see the schools cannot afford to have them. (Principal URCE, 2016)

It was indicated that teachers in urban areas can easily access teaching and learning material like internet facilities and books, and in addition to government remuneration they receive 'top up' from the parents' funds, not to mention access to social amenities like electricity, clean water and others. This scenario shows that there is need for redistribution of resources (both material and human) between the rural and urban areas for there to be equity in access and education outcomes for all Rwandans.

Horner et al. (2015) concur that the issue of the distribution of teachers between urban and rural areas in most countries does not only reflect disparities in total numbers, but also shows that female teachers and more experienced teachers are unevenly distributed between rural and urban areas (ibid, 36).

In this regard it is important to note that although teachers in Rwanda are recruited on merit, implying that gender difference is not considered as a factor, there are discernible gender disparities in the way female and male teachers are represented not only within some geographical locations but also at different levels of education. For instance, in 2014 the proportions of female and male teachers at primary school level were 53.5 per cent and 46.5 per cent respectively while at secondary school level it was 70.1 per cent (males) and 29.9 per cent (females). For the administrative staff, the proportion of females heading schools was less than one third at both levels (MINEDUC 2015). This suggests that the government policy of at least 30 per cent female representation in management positions is not effectively implemented within education. Moreover, the disparity between male and female teachers, particularly at secondary school level, is attributed to the low enrolment of female students at higher institutions of learning that train teachers. For example, the percentage of female students at the University of Rwanda, College of Education for 2015-16 was only 30.6 per cent.

Therefore, low numbers of female teachers at secondary school level have implications not only in terms of their misrepresentation and lack of recognition, but also in terms of a lack of role models for girls, especially those in rural communities where their presence may encourage parents to send their daughters to school (UNESCO 2006).With regard to remuneration, in general teachers in public schools get lower salaries compared to private schools. The pay difference between a graduate teacher (AO) is about three times more than that of a S6 graduate (A2). As Bennell and Ntagaramba (2008) point out, there is no pay progression within each of the three main qualification groups for teachers, and the only way for a teacher at A1 or A2 to increase their pay significantly is to upgrade their qualification to diploma and education degree respectively.

Most of the interviewees agreed that secondary and primary school teachers earned very little. A qualified primary school teacher earns about Rwf. 45,000. That is less than $60 dollars a month, which is less than $2 per day. Someone who has a diploma earns Rwf. 98,000, which is over $100. A new graduate earns Rwf. 120,000, which is over $150. They reiterated that teachers may lack peace of mind due to their economic status. This in the long run impacts negatively on those under their care - the learners. Other respondents put it in the following words:

In Kinyarwanda rather we say that 'umuntu atangicyafite' (you can only give what you have). The employed angry, frustrated people cannot be very good contributors to peace. They can only contribute what they have. (REB-TDM official 1, 2016)

As they say: 'a hungry man is an angry man'. Poverty is one of the points. And so as far as teachers are concerned, they earn little money. (REB-TDM official 1, 2016)

You cannot give what you do not have. We need to feel peace so that we can help our students for social cohesion. I think you understand what I mean. With this meagre salary, do you think that we are at peace? (Male teacher, GSS, 2016)

It was further revealed that there are some teachers with Master's level qualifications teaching in secondary schools who cannot be paid based on the qualifications since the payment scale ends at Bachelor's level.

We have not reached the level of paying the teachers at the master's level. That's why those who have such qualifications end up moving to other sectors. (REB-TDM official 2, 2016)

To supplement the meagre earnings of the teachers a number of support initiatives were mentioned to have been put in place. These include the establishment of Umwalimu SACCO in 2007, a savings and credit cooperative organisation where teachers can easily access loans at a relatively low interest. Each member is allowed to borrow up to five times their savings. Other incentives include one teachers' house with eight rooms per district where any teacher with accommodation problems can request to stay. These usually accommodate single teachers but it was mentioned that there are plans to upgrade them to be able to accommodate families. There is also the One Cow per Family (Girinka) programme, where teachers are given cows and another programme where teachers are given laptops.

We have also provided laptops. That may not sound an incentive but considering that laptop cost a teacher's net pay of almost a year, that's a big deal. But we still need to do more to make sure that our teachers have basics for survival. (REB-TDM official 1, 2016)

The incentives have been useful particularly to rural teachers where we have given them cows and you know that Rwandans really look at cows as useful domestic animals economically and culturally. (REB-TDM official 1, 2016)

Another incentive mentioned in this regard that has just been passed and is yet to be implemented is the horizontal promotion based on performance evaluation. This earns the teachers a bonus as they move from one level to another. Previously, this kind of promotion was not applicable to public teaching staff but only to administrative positions, as an official at REB-TDM observed.

School environment and teacher working conditions

The school environment and teacher working conditions can critically motivate or demotivate teachers. Lee et al. (2012) observe that the school context directly impacts teachers' classroom practices and therefore has a bearing on student outcomes. Heavy teaching workloads can be one of the disincentives that will affect teacher motivation. In Rwanda teaching loads are high; teachers are in class from 07:30 to 16:30, with an hour and a half lunch break. The workload norm for teachers in secondary schools is 30 periods a week, whereas for primary school teachers it is 40 periods a week. However, rural schools tend to have higher teaching loads, combined with lower pay since they are likely not to have parental motivation contribution (prime), and opportunities to earn a secondary income are considerably less (Bennell & Ntagaramba 2008).

Other than heavy teaching loads, poor physical environments, a lack of teaching and learning materials and poor student discipline were cited as disincentives to teacher morale in peacebuilding and social cohesion. For example, most teachers highlighted the lack of textbooks and teaching aids aligned with the new CBC:

You see the new curriculum is there but there are no textbooks yet for it, we are still using old textbooks which actually do not correspond well with the CBC. This is a challenge - there is a new curriculum, but there are no books to go with it. We read the curriculum and we try to look for topics in old textbooks that may correspond with it. (Female teacher, GSK)

We have been trained on the new curriculum but the problem is lack of textbooks it is still a problem. During training we were told that peace values and social cohesion are crosscutting in each and every subject. However since textbooks are not available, some teachers say that what is not written is not their business. (Female teacher, GSK)

These teachers would however observe that despite the lack of textbooks, most individual teachers that they know continue to improvise and teach their classes with whatever resources they can find. This reflects teacher agency, especially the idea of the teacher as a technocrat charged with the responsibility of ensuring students' learning (Horner et al. 2014).

Nonetheless, teachers of subjects other than History and Social Studies observed that they lacked guidance on how to integrate matters related to peacebuilding and social cohesion into other subjects deemed 'unrelated' to these issues. However, even among the teachers meant to teach these topics, some indicated that there are some areas pertaining to the history of Rwanda that they find sensitive to handle:

Teaching sensitive issues like the genocide is challenging. This issue may hold conflicting and opposing points of view. It is an emotional issue and the curriculum does not say much on how we can approach it. However I think that we as teachers should have the confidence to engage our students in exploring these issues. But we definitely need more knowledge and methodologies on how to teach such topics. (Female teacher, GSS)

Another teacher observed that when it comes to sensitive topics some teachers superficially teach such topics (babinyurahejuru). Those who do not fear to talk about them (sensitive topics) are very few, simply because students may go beyond borders (kurenga umupaka). It is important to note that teachers in Rwanda, like all other people in the country, have been affected by the genocide in one way or another, and are either seen to be on the side of the victims or perpetrators. Teachers therefore need support to confront their personal emotions for them to be able to help their students, restore trust and promote reconciliation.

A Director at Aegis Trust, the lead organisation of the Rwanda Peace Education Programme, admitted that it may be challenging for teachers to address the sensitive issues given the history of Rwanda, but that is the essence of their programme. He pointed out that the teachers they have trained so far can comfortably address such issues because of the methodology that they use.

.that's actually what we help teachers with. Ways of dealing with sensitive issues, talking about ethnicities, Hutu, Tutsi in schools, genocide in classrooms. Because when you talk with teachers who have received our training, they would tell you that before receiving our training, they would skip such sensitive issues or topics on the program. They would just skip and tell students: go and ask parents or relatives, but don't ask me such things. And now we train them about a way of tackling those issues. And the beauty of the story telling is that you don't tell the story yourself as a teacher. You give them tools, testimonies, stories from either survivors or rescuers or even perpetrators who repented and acknowledge what they did. So they use those stories from the very people who went through the experience. They don't have to say anything. Then they engage students in activities. So it is easier tackling the topics that way. (Director at Aegis, 2016)

The schools covered by the Aegis Trust for the above mentioned in-service training of teachers are however limited compared to the teacher population in schools. Moreover, after the genocide, from 1995, there was a moratorium placed on the teaching of some parts of Rwandan history (Gasanabo et al. 2016). Freedman et al. (2004) posit that there were divergent opinions over the precise history of what had occurred. Thus designing a History curriculum soon after the genocide required careful management of the situation (Gasanabo et al. 2016). They observe that the History curriculum has been updated a number of times, in 1996, 2008, 2010 and with the new Competence Based Curriculum in 2016 (ibid). Yet, despite the frequent updates on the curriculum, many teachers do not get the opportunity to benefit from in-service training on the issue. Consequently many teachers may still feel uncomfortable to tackle contentious topics in the subject and skip them. This would be a lost opportunity in dealing with past events, and developing new relationships of trust that pave the way to more long-term reconciliation.

Another concern among teachers in some of the schools visited was the poor student discipline and the lack of parental support; this they mentioned as an area of frustration that they have to contend with in their work. They observed that it is very difficult to have some parents cooperate with the school on their children's behaviour; apparently most parents are too busy to follow-up on their children or even respond to summons from the school head teacher or the teachers.

There is also the problem of parents who are not there for their children. It is like when they send their children to school, it is over. They do not follow up on the students to see if they have done their homework or if they have attended school - they leave all that to the teachers. (Deputy Head teacher GSM2, 2016)

This is a town and most parents struggle to supply for their families every day. Sometimes you call a parent when there is a student with bad manners but then the parent never comes. Then you stop sending the student for the parents because you realize that if you keep sending them out they miss classes. So you try to be close to the student because we are like their parents. (Female teacher GSM2, 2016)

Indeed teachers have devised several ways to address student indiscipline, and some even resort to corporal punishment in the form of beatings, even if this has been outlawed in schools. In one of the schools visited, severe caning was openly used on the students since this was seen as the only way to deal with students' indiscipline in that particular school. Yet, teachers also admitted that in general, most learners come from poor families and this has an impact on children's welfare and learning. The teachers mentioned that some students spend a full day at school with no lunch because parents are not able to pay for meals. As a result, such students are likely to miss classes or lack concentration in class because they are hungry.

Literature shows (Dunne 2007 cited in Horner et al. 2014; Harber 2004 cited in Horner et al. 2014) that corporal punishment in school can be unfair and excessive and may have negative consequences on children learning. 'Corporal punishment has consequences of deterring learners from school and increasing truancy rates, particularly among young men who tend to be the recipients of punishment' (Dunne 2007 cited in Horner et al. 2014). Moreover, it would be contradictory to expect teachers and schools for that matter to foster peacebuilding and social cohesion or teach non-violent ways to resolve conflicts among students when they themselves do not apply this.

Other forms of violence, such as student violence against teachers, were seen as a very rare occurrence among the schools visited. This could be attributed to the student-teacher relationship in the context of Rwanda, where teachers are still very much seen as figures of authority, and are therefore rarely challenged by their students. Moreover, acts of physical violence are rare in public spaces including schools. Nonetheless, other forms of violence like peer bullying and verbal and physical fights among students were reported and seen to occur within the school vicinity or when students are on their way to or from school.

CONCLUSION

This article set out to understand how teachers are situated in the process of peacebuilding and fostering social cohesion in schools in Rwanda after the genocide of the Tutsi in 1994. It reveals that education in general has been envisaged to play a crucial role in the reconstruction of the country, economically, socially and even emotionally. The educational policy context in Rwanda has indeed been favourable and a lot has been practically achieved to this end, especially in expanding access to education, building the infrastructure, developing pre-service training and the management of teachers. This to some extent speaks to issues of recognition of teachers as a key component of the education system, the redistribution of resources for teacher development (both material and human), and representation as a prerequisite for teacher participation and reconciliation to address the injustices of the past.

Yet, this article has shown that for teachers to play a role in sustainable peace and social cohesion largely depends on a number of interrelated factors - the economic, social, cultural and political contexts in which teachers operate. The findings of this study reveal that although most teachers show agency and have a sense of responsibility towards promoting peacebuilding and social cohesion, they still face major challenges in their everyday practice and social life that will not put them at peace. As most of them often observed during this study 'one cannot give what they do not have'. This is to indicate that a teacher, who is poorly remunerated, with no continued professional development, who operates in a poor environment and suffers from low self-esteem, may not be in a position to nurture sustainable peace within and outside of school.

However the issues may not only be confined to physical challenges. Indeed, most of the teachers interviewed spoke with a sense of pride and passion about their work, and therefore deserve recognition for their experience and professional judgement, and the valid contribution they bring to educational debate and policy formulation (Horner et al. 2015), both as a group, but also as individuals. This article also raises issues of the non-equitable redistribution of the teaching staff from both a rural/urban perspective, as well as a gender perspective. The issue of limited access for female students joining higher education institutions for teacher training like UR-CE requires attention. At the same time there is a need to identify concrete interventions aimed at fair distribution of qualified teachers across the country, including hard-to-reach areas. As we have seen, reconciliation is a process that is crucial for post-conflict societies to address past injustice as a way to prevent a relapse into conflict. This however requires teacher management structures and education processes that support teachers on how to respond appropriately to the needs of their students and how to develop caring and trusting relations (Horner et al. 2015).

There is a need therefore for more recognition of the value of teachers as a key component of the education system, a need to enhance their involvement and representation in decision making, a need to redistribute resources for teacher professional development, and other areas of teacher wellbeing, for them to be fully immersed in the process of reconciliation and sustainable peacebuilding.

REFERENCES

Barrett, A.M. 2007. Beyond the polarization of pedagogy: Models of classroom practice in Tanzanian primary schools. Comparative Education 43(2): 273-294. [ Links ]

Barrett, A.M., S. Ali, J. Clegg, J. Hinostroza, J. Lowe, J. Nikel, M. Novelli, G. Oduro, M. Pillay, L. Tikly and G. Yu. 2007. Initiatives to improve the quality of teaching and learning: A review of recent literature. Background paper prepared for the Global Monitoring Report 2008. EdQual-UNESCO.

Bennell, P. and J. Ntagaramba. 2008. Teacher motivation and incentives in Rwanda: A situational analysis and recommended priority actions. Kigali: Rwanda Education NGO Cooperation Platform. [ Links ]

Bonnet, G. 2008. Do teachers' knowledge and behavior reflect their qualifications and training? Evidence from PASEQ and SACMEQ country studies. Prospects 38(3): 325-344. [ Links ]

Buckley-Zistel, S. 2009. Nation, narration, unification? The politics of history teaching after the Rwandan genocide. Journal of Genocide Research 11(1): 31-53. [ Links ]

Campbell. C. and P. Kent. 2010. Using interactive white boards in preservice teacher education: Examples from two Australian universities. Australian Journal of Educational Technology 26(4): 447-463. [ Links ]

Dladla, N. and B. Moon. 2013. Teachers and the development agenda. An introduction. In Teacher education and the challenge of development: A global analysis. Edited by B. Moon, 5-18. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Durrani, N. and M. Dunne. 2010. Curriculum and national identity: Exploring the links between religion and nation in Pakistan. Journal of Curriculum Studies 42(2): 215-240. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. 2005. Reconceptualisation of justice in a globalized world. New Left Review 36: 79-88. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. 1995. From redistribution to recognition? Dilemmas of justice in a 'post-socialist' age. New Left Review 1(212): 68-93. [ Links ]

Freedman, S.W., D. Kambanda, B.L. Samuelson, I. Mugisha, I. Mukashema, E. Mukama, J. Mutabaruka, H.M. Weinstein and T. Longman. 2004. Confronting the past in Rwandan schools. In My neighbor, my enemy: Justice and community in the aftermath of mass atrocity. Edited by E. Stover and H.M. Weinstein, 248-265. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Fullan, M. and A. Hargreaves. 1992. Teacher development and educational change. In Teacher development and educational change. Edited by M. Fullan and A. Hargreaves, 1-9. London: Falmer. [ Links ]

Galtung, J. 1995. Three approaches to peace: Peacekeeping, peacemaking and peacebuilding. In Peace, War and Defence: Essays in peace research. Vol. 2. Edited by J. Galtung, 282-304. Copenhagen: Christian Ejlers. [ Links ]

Gardinier, M.P. 2012. Agents of change and continuity: The pivotal role of teachers in Albanian educational reform and democratization. Comparative Education Review 56(4): 659-683. [ Links ]

Gasanabo, J., F. Mutanguha and A. Mpayimana. 2016. Teaching about the holocaust and genocide in Rwanda. Contemporary Review of the Middle East 3(3) 329-345. Retrieved from: cme.sagepub.com/content/3/3/329.full.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2017). [ Links ]

Gaziel, H. 2009. Teachers' empowerment and commitment at school-based and non-school-based sites. In Decentralisation, school-based management, and quality. Edited by J. Zajda and D.T. Gamage, 216-229. New York: Springer. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-90-4812703-0_12 (accessed 13 August 2016). [ Links ]

Government of Rwanda (GoR). 2003. The Constitution of the Republic of Rwanda. Kigali: Republic of Rwanda. [ Links ]

Horner, L., L. Kadiwal, Y. Sayed, A. Barrett, N. Durrani and M. Novelli. 2015. Literature review: The role of teachers in peace building. Retrieved from: http://learningforpeace.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/The-Role-of-Teachers-in-Peacebuilding-Executive-Summary-Sept15.pdf (accessed 15 May 2016).

Lee, H., G. Kersaint, S. Harper, S. Driskell and K. Leatham. 2012. Teachers' statistical problem solving with dynamic technology: Research results across multiple institutions. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 12(3): 286-307. [ Links ]

Lederach, J.P. 1995. Preparing for peace: Conflict transformation across cultures. Syracuse: In Syracuse University Press. [ Links ]

Lederach, J.P. 1997. Building peace: Sustainable reconciliation in divided societies. Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace Press. [ Links ]

Nardone, J. 2010. Intolerably inferior identity: How the construction of race erased a Rwandan population. Peace and Conflict Monitor. Retrieved from: http://www.monitor.upeace.org/innerpg.cfm?id_article=707 (accessed 4 November 2016).

Ponorac, T. 2010. Culture and language. Defendology Center for Security, Sociological and Criminological Research Banjaluka. Retrieved from: http://www.sputtr.com/ponorac (accessed 8 November 2016).

National Unity and Reconciliation Commission. 2015. Rwanda reconciliation barometer. Kigali: NURC. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 1999. A survey on the secondary school teachers 'profile. Kigali: Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Scientific Research. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 2003. Education sector policy. Kigali: MINEDUC. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 2007a. Teacher development and management policy in Rwanda. Kigali: MINEDUC. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 2007b. Special needs education policy. Kigali: MINEDUC. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 2013. Education sector strategic plan 2013-2017. Kigali: MINEDUC. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. n.d. Education sector strategic plan 2010-2015: Draft 2. Kigali: MINEDUC. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 2015. Education statistical yearbook. Kigali: MINEDUC. [ Links ]

Naylor, R. and Y. Sayed. 2014. Teacher quality: Evidence review. Office of Development Effectiveness: Commonwealth of Australia.

Republic of Rwanda. 2000. Rwanda Vision 2020. Kigali: MINECOFIN. [ Links ]

Republic of Rwanda. 2013. Economic development and poverty reduction strategy II2013-18. Kigali: MINECOFIN. Retrieved from: http://www.rdb.rw/uploads/tx_sbdownloader/EDPRS_2_Main_Document.pdf (accessed 10 September 2014). [ Links ]

Rutayisire, J., J. Kabano and J. Rubagiza. 2004. Redefining Rwanda's future: The role of curriculum in social reconstruction. In Education, conflict and social cohesion. Edited by S. Tawil and A. Harley, 315-376. Geneva: UNESCO/IBE. [ Links ]

Smith, A., E. McCandless, J. Paulson and W. Wheaton. 2011. Education and peacebuilding in post- conflict contexts. A literature review. New York: UNICEF. [ Links ]

UNESCO. 2006. The impact of women teachers on girls' education. An advocacy brief. Bangkok: UNESCO. [ Links ]

UNICEF. 2011. The role of education in peace building. Literature Review. Retrieved from: http://www.unicef.org/education/files/EEPCT_Peacebuilding_LiteratureReview.pdf (accessed 20 June 2015).

VSO. 2004. Seen but not heard: Teachers' voices in Rwanda. A policy research report on teacher morale and motivation in Rwanda. London: VSO. [ Links ]

World Bank. 2012. What matters most in teacher policies? A framework for building a more effective teaching profession. System approach for better education results (SABER). Washington, DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

1 It was mentioned that teachers sometimes receive training that pertains to peacebuilding, social cohesion and promoting Rwandan values from the Itorero and Ingando national programmes. These however are more or less informal programmes that operate independently, although in collaboration with the Ministry of Education.