Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 n.3 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/1482

ARTICLES

Supporting teachers in becoming agents of social cohesion: professional development in post-apartheid South Africa

Rada Jancic MogliacciI; Joyce RaanhuisII; Colleen HowellIII

ICape Peninsula University of Technology Email: rada.mogliacci@gmail.com

IICape Peninsula University of Technology Email: joyce.raanhuis@live.nl

IIICape Peninsula University of Technology Email: chowell25365@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Policy and research have been advocating the importance of teachers in achieving equity and teachers are called to act as agents of social justice. This issue remains central to the development of a post-apartheid South Africa, where a need for reconciliation and healing still dominates the society. Such a landscape requires adequate support through transformative professional development. In this paper we analyse the design of the intervention 'Teaching Respect for All' that aims to empower teachers in South Africa to act as agents of social justice. Based on the literature review, content analysis of the intervention's manual and resource book, and interviews with stakeholders we explore if the intervention outline can support teachers in becoming agents of social cohesion. The qualitative content analysis of the data unearthed four aspects of the intervention: the what, the how, the why, and the so what. We argue that while the intervention enables an alteration of teaching practice, altering teachers' beliefs is a long-lasting and more challenging task. We conclude the paper with recommendations for transformative professional development programmes and the value of such for socially just education in South Africa.

Keywords: teacher change; CPD; social cohesion; Teaching Respect for All; intervention analysis

INTRODUCTION

A number of policy frameworks, both within South Africa and internationally, as well as research studies have emphasised the importance of teachers in contributing to the creation of education for all (Bajaj 2011; Buckler 2015; Korthagen 2004; OECD 2005; UNESCO 2014a). More specifically, teachers are recognised as key to addressing those inequalities which undermine this imperative, such as racial, cultural, and linguistic, to name a few, and thus to act as agents of change in the development of more equitable and just educational systems - that is, as agents of social cohesion. To do this they are expected to adopt transformative pedagogical practices that support a social justice agenda and actively to promote such an agenda through their work.

The concerns of social cohesion remain central to the building of a post-apartheid education system in South Africa, a country that is still struggling with redressing the inequalities of the past and building a new society through reconciliation and healing (Badat & Sayed 2014; Christie 2016). For the education system this must contiunue to involve challenging the pervasive and divisive legacies of the past and overcoming the decades of conflict which characterised it (Christie 2016; Weber 2008). The change that is required is significant and complex, prompting teachers to adopt various coping strategies in deal with it (Le Roux 2011).

Certainly, there is evidence within the education policy framework post 1994 of recognising the role of the education system in the promotion of social cohesion and, in particular, noting the importance of teachers in this respect. Important here is the Manifesto on Values, Education & Democracy, developed and published by the Department of Education in 2001 (DoE 2001a). This policy directly addresses social cohesion concerns by setting out ten fundamental values to be taught as part of the curriculum.1 Teachers are expected to demonstrate the values they uphold and to recognise their responsibility by setting examples as role models (DoE 2001a, 4). In addition, the National Policy Framework for Teacher Education (NPFTED) emphasises that schools must respond directly to social inequalities by helping children to acquire appropriate knowledge, skills and values (DoE 2006, 7). Most recently, the country's National Development Plan 2030 (NDP) emphasises the significant role of the education system in building an inclusive society by 'providing equal opportunities and helping all South Africans to realise their full potential, in particular those previously disadvantaged by apartheid policies, namely black people, women and people with disabilities' (NPC 2012, 296).

Some recognition is given in the policy framework that teachers require particular levels and kinds of support to give effect to their role as agents of social cohesion. Continuing Professional Development (CPD) is recognised as a key mechanism to facilitate such support, together with a range of other imperatives which it is expected to fulfil (DoE 2007).

In order to help teachers to meet these expectations, their continuing professional development is one of the priority policy goals (DBE 2015). Bertram (2014), however, argues that the South African policy on teacher development (DBE & DHET 2011) is not context-sensitive, and has a rather linear system for identifying teachers' needs. This suggests that it is up to professional development programmes to address these aspects if they are to contribute to teacher change (Bertram 2014). With this context in mind and being cognisant of the fact that the translation of these policy intentions into practice has been fraught with many challenges, this paper explores how one non-governmental organisation has responded to the challenge of building the capacity of teachers to be agents of social cohesion through CPD.

The CPD initiative explored in this paper is called 'Teaching Respect for All' (TRA) and forms part of a range of social cohesion interventions in South Africa undertaken by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR). This initiative has its roots in a joint UNESCO project launched in 2012 between the United States and Brazil called 'Teaching Respect for All'. The project was piloted in various countries with the intention of overcoming discrimination in and through education with a key focus on supporting teachers to be agents of social justice (UNESCO 2014b; Kirchschlaeger et al. 2013). Although South Africa was not one of the targeted pilot countries, the IJR took the initiative in collaboration with the Department of Basic Education (DBE) and provincial education departments to design a similar programme for the South African context. The key focus of the intervention has been the design and implementation of a workshop programme for teachers aimed at building their capacity to be agents of social cohesion.

This paper aims to critically explore the IJR programme through a consideration of its design and approach, reflecting on its ability to contribute effectively to developing teachers' agency in the pursuit of social justice in South Africa.

DEVELOPING TEACHERS' CAPACITY TO BECOME AGENTS OF SOCIAL COHESION THROUGH CPD

This paper asserts that CPD provides an especially important mechanism for building the capacity of teachers to act as agents of social cohesion and that this requires complex processes of teacher change. This starts from the premise that, given the nature of the history and the perversion of education by the apartheid system, building the capacity for teachers in South Africa to act as agents of social cohesion within their classrooms and schools must involve teacher change. Moreover, while the initial teacher education system (ITE) of the post-apartheid system must find new ways of equipping teachers in their formative training to deal with the complexities of our society, the depth of what is required also necessitates the provision of on-going CPD that specifically seeks to facilitate teacher change towards a social justice agenda. While there may be little argument with this assumption, it is not always clear what we mean by teacher change and thus what the characteristics of CPD interventions that seek to bring about teacher change should be. In this section, we briefly explore the concept of teacher change and consider what would make CPD interventions effective in bringing about such change.

Teacher change

Teachers change throughout their teaching career (Fullan 2007; Ketelaar et al. 2013). The change is induced when teachers gather new experiences that inform their knowledge, skills, pedagogical practice and thinking, or when new policies and reforms are introduced as part of broader processes of educational change (Fullan 2007). A number of scholars have written about issues of teacher change (Richardson 1994a; Le Roux 2011; Guskey 2002) and although there is a variety of understandings, what we understand the term 'teacher change' to mean, in this study, is the alteration in knowledge and skills, pedagogical practices, and beliefs and attitudes of teachers.

Another aspect that is discussed in relation to teacher change is what factors may influence successful change. Most studies recognise that changing practices or beliefs is always very challenging (Avalos 2011; Timperley, Wilson, Barrar & Fung 2007). Pang and Park (2003) argue that for teachers to change they must be able to internalise the goals that the change seeks to bring about - in other words, the change must make sense to the teacher and their practice. Similarly, teachers must feel motivated to effect necessary changes, especially where they are required to adopt new practices and beliefs (Fullan 2007; Gatt 2009). This emphasises the importance of having motivated teachers who openly seek possibilities for change or engage in activities that promote change. However, a number of writers have emphasised how important the issue of context is in the processes of teacher change.

Guskey (2002) argues that teacher change is a pathway that begins with CPD where the new knowledge and skills are acquired, and is followed by changes in teaching practice which in turn result in changes to student learning outcomes. Finally, he suggests, this change of practice that caused a positive outcome leads to changes in teachers' beliefs and attitudes. This approach implies that teacher change does not necessarily result only from a CPD intervention, but that a number of aspects affects its outcome. However, what is important about this assertion is that it suggests that a number of processes of change must take place along the pathway initiated by CPD if it is to lead to changes in teachers' beliefs and attitudes. This draws attention to how CPD interventions are designed and implemented and thus whether they are able to address each of the elements along the pathway.

Characteristics of a CPD that brings about teacher change

Timperley et al.'s (2007) study suggests that there are four aspects that must be considered for an effective CPD to be able to bring about the kind of change discussed above. The four aspects are: the context of the CPD intervention, the content of the intervention, the activities used to support teachers' learning, and the learning processes. These assertions are supported by some more recent studies, such as Cordingley et al. (2015). In their review of the professional development of teachers, time, content, sensitivity to teachers' diverse learning needs, participation in a community of practice and supportive leadership were identified as especially important for effective CPD.

Fullan (2007) argues that it is important to make a distinction between two possible approaches to implementing any intervention. The first, a prescriptive one, instructs teachers and schools on what the intervention should be and how it must be implemented. With such an approach there is very little room for interpretation and contextual-sensitivity, with limited opportunities for adjustments to the needs of individual teachers. It is something that is 'done to teachers' (du Preez & Roux 2008). On the other hand there is another perspective, one that is sensitive to situational specificities and diverse teachers' needs, allowing teachers and schools to make adjustments accordingly, and where teachers become partners in professional development (du Preez & Roux 2008; Fullan 2007). In their study on teachers in sub-Saharan Africa, Bennell and Akyeampong (2007) point out that teacher motivation is strongly influenced by both internal forces, such as their commitment to the teaching profession in their particular context, but also by various external factors that define the context in which they live and work, such as personal security (or lack thereof), the policy environment and their working conditions.

This suggests that if CPD is to bring about necessary teacher change the content of an intervention must make sense to teachers in relation to the broader policy framework in which they work and to which they are accountable. Hence, effective CPD is consistent with broader policies shaping the education system in which the teachers work (Timperley et al. 2007).

Similarly, the content should enable teachers to translate the 'theory' into their practice - it must make sense to them in their daily practice (ibid.). This assumes that CPD provides a clear connection between theory and practice with a set of methods and approaches that are user-friendly. Therefore, programmes with content that is applicable should be the basis of the CPD since it has been shown to have an effect on teacher professional learning and change in their practices.

Apart from the applicability of the knowledge, studies have shown that teachers' engagement in learning activities is another aspect of effective CPD (Timperley et al. 2007; Gatt 2009; Sedova, Sedlacek & Svaricek 2016). These studies have shown that teachers' active participation in CPD activities presents an important element that ensures the internalisation of the CPD content. Furthermore, Timperley et al. (2007) found that engagement is more relevant for a successful CPD programme that contributes to teacher change than, for example, voluntary participation and initiation of the CPD intervention.

The same study emphasised further that teachers also need time to engage with and reflect on the new ideas, approaches and methods that they have been exposed to, suggesting that interventions that take place over extended periods of time and involve on-going processes for reflection and repetition if necessary make for effective CPD (Gatt 2009; Sedova, Sedlacek & Svaricek 2016). It is through such guided reflection that inherent tensions which emerge when new knowledge, practices and beliefs are introduced can be managed and grappled with and new understandings negotiated (Fazio 2009; Gatt 2009; Sedova, Sedlacek & Svaricek 2016; Husu, Toom & Patrikainen 2008). Therefore, the term guided reflection here refers to an organised activity where teachers' reflection is unfolded 'as part of the social interchange that exists among teachers' (Husu, Toom & Patrikainen 2008, 40) .

Finally, teachers always work and live in a specific context and this context is always framed by a particular set of contemporary forces shaping their experience at that particular 'time'. However, they also bring into this time-bound space what they have acquired from their education and previous experiences - these will always be important to how they respond to new changes that are required of them. Some writers have therefore argued for the importance of confronting teachers' temporal dislocation (Jancic Mogliacci 2015; Le Roux 2011). The term 'temporal dislocation' assumes teachers' embeddedness in the time and the system that shapes their personal and professional understandings. Opportunities for teachers to confront these deeply embedded practices and beliefs open a space for change. This is especially relevant for the South African context. Teachers in South Africa have spent the last two decades trying to break away from the apartheid past and struggle on an on-going basis with issues of reconciliation, woundedness and prejudice, to name just a few (Weldon 2010).

Therefore, what is especially important in the South African context is that such CPD interventions create the necessary space where existing, problematic discourses, often informed by our past, can be challenged in a supportive and respectful environment -where teachers are enabled to challenge their past in order to enact socially just practices (Weldon 2010).

In summary, from the writers captured above, CPD that enables effective teacher change is flexible and sensitive to situational specificities (in all their richness and variety), enables time for teachers to engage with and process new ideas, provides content that is applicable to and makes sense within the context, both inside and outside the classroom, is responsive to teachers'diverse needs, and is designed around activities that facilitate the negotiation of new understandings, challenge problematic discourses and involve teachers in active processes of learning. This study will use these eight identified categories to explore the potential of one specific intervention to support teachers to act as agents of social cohesion.

THE IJR TEACHING RESPECT FOR ALL INTERVENTION

TRA is an intervention launched in 2012 by UNESCO with the aim to tackle discrimination in and through education in several countries. In cooperation with the Department of Basic Education and provincial education departments IJR has redesigned the TRA workshops, with four goals in mind: (1) To determine what forms of discrimination and disrespect educators are experiencing at schools across the country; (2) To determine what methods they are using to address these; (3) To share the UNESCO Toolkit with the participants, in order to assist with dealing with these sensitive issues; and (4) To develop a resource with South African case studies of how educators are dealing with discrimination and inclusion.

Workshop scenario

Since 2012, IJR has given workshops to over 500 educators in every province (Robertson, Arendse & Henkeman 2015). Workshops took up 3-4 hours, during which participants shared stories, experiences and examples of good practice. The workshop consists of four parts: 1) An action learning cycle for situational analysis and reflection; 2) Sharing and documenting of personal stories of discrimination and disrespect; 3) Personal development: dealing with perceptions and how they could lead to conflict; and 4) Highlights of UNESCO's Teaching Respect for All.

During the first part of the workshop, exercises are used in order to explain the value of the action-learning tool. The tool intends to encourage critical thinking and to stimulate insight into matters. Thus, the exercises could be used in classrooms to let learners critically reflect on experiences of bullying, discrimination or respect which they have witnessed or in which they have participated (IJR 2015, 47).

In the second part of the workshop, participants share best practice stories on how they effectively dealt with issues of disrespect, discrimination, racism, xenophobia or sexism. Teachers are asked to select a story that resonates in classrooms across the country, which is then collaboratively further refined and documented before being shared with the rest of the participants.

During the third part of the workshop, a presentation is given on perceptions, resilience or the impact of Bantu education (Robertson, Arendse & Henkeman 2015, 7). Exercises are used to make participants aware of their perceptions and how to deal with perceptions in a positive way. The 'Ladder of Inference' is used in order to explain the reflective process, whereby one observes, makes assumptions, draws conclusions on beliefs and takes actions based on these beliefs (IJR 2015, 48-49). In the last part of the workshop the UNESCO Respect for All Toolkit is shared.2

RESEARCH DESIGN

This study is designed as what Yin (2009) calls an exploratory study, with the aim of examining the potential of the intervention TRA to support teachers in becoming agents of social cohesion. This approach is particularly suited for exploring interventions that do not have a single set of outcomes, which was the case with the TRA intervention. A case in this instance is defined as 'a phenomenon of some sort occurring in a bounded context' (Miles & Huberman 1994, 25). Apart from answering a 'what' question, the case study design enables researchers to answer 'why' and 'how' questions (Stake 2008). The analysis of this case is based on multiple sources.

Data set

The data for this study comes from three different sources:

• Part 3 of UNESCO's 'Teaching respect for all: an implementation guide', hereafter called 'the guide' (UNESCO 2014b, 123-173). Overall, this guide serves as initial material that informs the local implementation of the intervention while Part 3 specifically deals with the instructions for teachers and educators on how to implement 'Teaching respect for all' in the classroom and school activities.

This part consists of seven 'tools' or sections that support teachers or educators in creating child-friendly schools and classrooms through a whole school approach. The sections covered self-reflection, methods of dealing with difficult topics related to discrimination, clarifying the types, motives and forms of discrimination, involving parents and community, key plans, and an overview of teacher training and professional development.

• Workshop scenario description as provided in the teacher resource book 'Classrooms of hope', hereafter called 'the resource' (IJR 2015), prepared by the local providers of the intervention at the Institute for Cohesion and Reconciliation in South Africa. This resource book has a twofold purpose: it provides information about the implementation of the intervention, and it also presents selected case studies gathered from the teachers who participated in these workshops.

• Three interviews with the local providers. Two were collected in 2015 and one in 2016.3

The versatile nature of the data ensured validity through the triangulation of data sources (Denzin 1978 cited in Miles & Huberman 1994).

Data analysis

We applied a qualitative content analysis in order to explore possibilities of teacher change through the transformative CPD intervention 'Teaching respect for all'. This method is empirically grounded and exploratory, enabling researchers to describe systematically the meaning of qualitative data (Mayring 2000; Schreier 2014).

One of the key features of qualitative content analysis is that it reduces the amount of analysed material, focusing our attention on selected aspects of meaning. For the purpose of this study, the content analysis of the data was based on the deductive application of a priori categories that were identified in the literature review and that characterise the effective CPD interventions that bring about teacher change. The data segments (aspects of the meaning) were coded to fall into one of the following categories: (1) situational specificities, (2) time for teachers to engage with the new ideas, (3) applicable content, (4) content aligned with diverse teachers' needs, (5) content aligned with policy and practice, (6) negotiating and discussing understandings, (7) challenging problematic discourses, and (8) engaging teachers in learning activities.

Content analysis is a flexible method where segmentation can be data-driven as well. Therefore, during the analysis process, one more category emerged that was not based on the theory-based categories - the category of outreach. Although the reviewed literature did not elicit this aspect of the CPD, the outreach component of this intervention holds a prominent place and was therefore included in the discussion of the findings.

FINDINGS

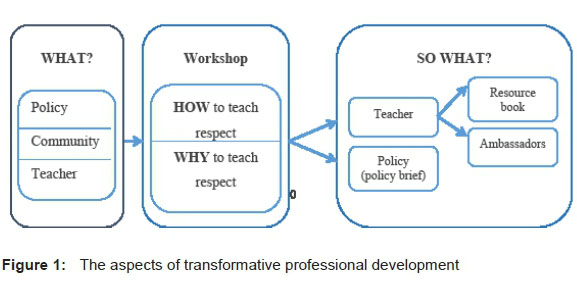

The analysis of the data unearthed four aspects of the intervention that are important to the concerns of this paper: 'the what' - showing how the intervention design is based on the situational appreciation of teachers; 'the how' - providing teachers with the tools that empower them in becoming agents of social cohesion; 'the why' - creating a space for guided reflection of teachers where they can engage in re-examining their perceptions about socially just education; and 'the so what' - translating the programme into a meaningful change process that goes beyond the once-off workshop effect (Figure 1).

'THE WHAT' - BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN POLICY AND PRACTICE THROUGH SITUATIONAL APPRECIATION

The literature review identified that for an effective CPD of teachers, it is necessary to take into account the contextual specificities of teachers' work. The content analysis of the data showed that situational appreciation in TRA intervention is manifested on three levels: policy, local community, and teacher level.

Policy level

The TRA guide states that it does not intend to impose upon any existing policy or curricular framework but to be integrated into the existing one. It promotes a whole-school approach to advocating human rights in schools and classrooms similar to the South African policy on school evaluation (DoE 2001b). The guide states the following:

The whole school approach recognizes that prejudice reduction cannot result from individual efforts, but must be mainstreamed throughout each setting - it must be incorporated into every policy, activity and interaction that takes place in the school. (UNESCO 2014b, 129)

In addition, one of the recommendations in the guide includes: aligning mission, policies, and practices with respect; focusing on cultural diversity as a human right; expanding the curriculum for inclusion; using a systematic approach; integrating prejudice reduction; curriculum adaptation for diverse learners; effectively using multigrade classrooms; using helpful textbooks; training teachers on how to teach respect for all; teaching controversial topics; and using teachable moments (UNESCO 2014b, 138).

Even though these are declarative recommendations, the guide provides further indicators on how to establish a whole-school approach, for example including disciplinary policies, pupil support services, formal and informal curricula, etc.

Translating this into the local realities required the providers to address a variety of aspects and to include all the stakeholders in the process. An IRJ staff member reflected on this process, stating that:

We worked with directorates of social justice and early childhood development (last one didn't last long due to retirement). So a whole year they tried to get a memorandum of understanding with SC department, trying to get them to meetings etc. (Interview 2)

Local community level

The UNESCO manual offers universal guidelines but it also directs the attention of local stakeholders to address local needs through a series of reflections. For example, one of the interviewees stated:

They [UNESCO] wanted our perspective, what's happening in our schools and the project deals with discrimination, violence, intolerance and disrespect in schools and so what we wanted to do when we initially met with the department was to compare what do you have, what are you currently doing in schools and what can we as an organisation bring to that process. (Interview 2)

Furthermore, the intervention providers acknowledge the different approaches that are necessary in different provinces of South Africa. For that purpose, in one of the interviews, an IJR staff member explains how teachers have different CPD needs due to dealing with different situations in different communities. The member gave an example of a province with a large number of 'child-headed' homes. In such areas, teachers have a challenging task of working with children who have a role as adults in their home and community, but are expected to take on the role of a child when they are in the school (Interview 3). Understanding these wider socio-economic characteristics of the area sensitises the providers to design the intervention in a way that will provide meaningful support to teachers.

Teacher level

The commitment to designing the workshop so that it is sensitive to situational differences of teachers and schools emerged through the interview analysis as well as the analysis of the intervention material. This appreciation was manifested not in the anecdotal approach to developing the workshops, but in a systematic path of gathering information from teachers. One of the interviewees recalled: 'We went to schools in every province, asked what type of discrimination they dealt with and what support they need to help dealing with this' (Interview 3).

Addressing all three aspects of situational appreciation provided the potential to bridge the gap between the policy-demands that require teachers to act as agents of social cohesion and its practical implementation in the classroom. Whether this potential will be realised depends on the capacity of the intervention to maintain this contextual balance between policy, school and teacher level.

'THE HOW' - TOOLS THAT EMPOWER TEACHERS TO BECOME AGENTS OF SOCIAL COHESION

The TRA intervention is designed with the goal to teach teachers how to confront the prejudices of their pupils and how to teach respect and human rights (Robertson, Arendse & Henkeman 2015).

The resource (IJR 2015, 5) shows that the level of confidence teachers expressed in dealing with teaching respect increased in comparison to the state 'before'. This reflects teachers' perception of their own competences to deal with the issues of respect and reconciliation. Competences are an important part of teacher agency and agentic teachers have capacities for transforming their pedagogical practices that contribute to inclusive classrooms with equal participation of all students (Pantic 2015). These capacities have potential to be improved through the explicit teaching methods that teachers are provided in order to tackle some of the aspects of social cohesion and inclusive education in their classrooms. These methods are part of the first section of the workshop where teachers experience the pedagogical approach they are expected to apply, as can be seen in the following example:

The questions are intended to encourage critical reflection. Only a few from each level should be asked. It is also intended to stimulate insight into matters in order to encourage better decisionmaking later on. This is a useful tool when you want to encourage learners to critically reflect on experiences of bullying, discrimination or disrespect they have witnessed or participated in. Of course, it is just as useful for us as educators in our professional development. (IJR 2015, 47)

The twofold purpose of the intervention activities - to learn about the new tools in teaching by applying them in learning - presents a possible way of enabling an effective learning environment for teachers. Learning by doing helps teachers internalise new pedagogical approaches and teaching methods.

Another important aspect that contributes to the effectiveness of the CPD is giving voice to teachers to actively take part in shaping the workshop. The design logic of the intervention relies on teachers' personal experiences and stories. It is their personal experiences that provided material for the resource book as well. This kind of approach enables the active participation of teachers in the CPD intervention. Active involvement in learning has been proved to play an important role in the effectiveness of the intervention, even if teachers' initial participation was not voluntary (Timperley et al. 2007).

'THE WHY' - CREATING A SPACE FOR GUIDED REFLECTION OF TEACHERS

One of the declared aims of the intervention is to support teachers in confronting their own prejudices and understanding how their own perceptions influence the social cohesion agenda. This is done by critically discussing teachers' cases that are shared in the workshop and the resource book (IJR 2015). However, these reflections also provide an important insight into many aspects of teachers' understandings that could perhaps be challenged. For example, the adjectives used to describe a good pupil are 'humble' (IJR 2015, 23), 'obedient' (IJR 2015, 27), etc., and in the description of the studies, pupils' voice and agency were often overlooked.

Therefore, the aspect of challenging perceptions and discussing understandings is an essential part of the intervention. One of the interviewees stated:

Without the teachers we won't obviously, we won't reach those learners so they are fundamental, they are crucial, they are the people that are going to retrain. I think they need a retraining and they need a reconditioning of their mind-sets and they need to deal with things like wounds. They need to be reconciled within themselves also to different, other ways of thinking about the other. (Interview 2)

Teacher reflection implies a careful interpretation and exploration of one's own understandings and perceptions (Husu, Toom & Patrikainen 2008). The aim of the intervention is to tackle the perceptions of teachers about teaching respect. It relies on the assumption that teachers are reflective practitioners. Therefore, the third and the fourth parts of the workshop scenario are based on guiding teachers' reflection regarding the issues of 'otherness' and prejudices.

Using the concept of woundedness, the IJR facilitated dialogues on the antecedents of the current lack of respect in society and the impact of it on schools. Teachers were encouraged to reflect on their own practice, and initially it was difficult for teachers to acknowledge their role in perpetuating for example the Bantu education system. Challenging these understandings through guided reflection by the intervention providers enables teachers to grasp the transformative potential of their pedagogical activities.

However, prejudices are deeply rooted, and are part of our belief systems for which we create a set of 'quazi-scientific' explanations or justifications. Identifying prejudices is a challenging task that requires repeated guided reflection (Pang & Park 2003). In addition, the research on teacher reflection-on-action has shown that professionals need to develop their ability to articulate their professional knowledge, justify actions and subjective theories (Husu, Toom & Patrikainen 2008). Reflexivity is a process rather than just a context of teachers' work and changing teachers' beliefs is a long-lasting process that requires repeated guided reflection on the practice, a 'critical friend' or an expert to support this process and time to reflect (Brodie 2013; Gatt 2009). The value of this intervention might be diminished without this continuous support in the form of creating a specifically allocated time and space for the critical reflection of teachers.

'THE SO WHAT' - WHERE TO FROM HERE

The TRA intervention does not only aim at training teachers. The providers use the opportunity of meeting teachers to gather valuable information. The data gathered during the workshops across South Africa and through the contact with teachers serves a twofold purpose: to inform the policy, and to provide support for teachers in tackling the issues of social cohesion in their everyday classroom work. From that perspective the outreach of the intervention goes beyond the once-off workshop effect.

Teachers' support to implement TRA in their everyday work is addressed with the resource book 'Classrooms of hope' on the one hand and the 'ambassadors' - trained educators that will provide assistance - on the other.

Previous studies suggest that teachers need an extended time to engage with new understandings in order for them to have an effect on teachers' practices and beliefs. Although the workshop itself is a short, once-off intervention, the resource aims at prolonging the effects of it. This materialc omprises nine case studies that were produced by South African teachers during the workshops. The book is designed in a user-friendly way, helping teachers to distinguish between the narrative of the case study and its interpretation. The authors, in addition, offer a learning section that enables teachers to generalise and translate specific situations to their own personal experience. Each case study closes with a set of questions that can possibly guide the teachers in their reflections. However, it is unclear if this resource book will find its way across the country to every teacher's classroom and if there will be sufficient support for guided reflection or self-reflection of teachers in their everyday work.

This hindrance might be addressed through the training of 'ambassadors' - teachers who were identified in the workshops and whose task it is to train other teachers. The reasoning is that:

After doing that whole process, we are now working with the department of social justice of the department, that directorate. They are elated with the project, they love the project, they see it is working and relating to social justice, so we now have a memorandum of understanding and agreement with them and over the next 3 years they want us to train master trainers in all the different provinces that will go out and train teachers on teaching respect for all. (Interview 3)

Their purpose can be to maintain the discussions among the teachers, to encourage them to use the resource book and to engage actively in challenging their own and students' perceptions.

Finally, another important and valuable aspect of the intervention's outreach is the policy brief that was created as an outcome of the intervention workshops across South Africa.

We also developed the policy brief to give the educational department some recommendations. The recommendations are from teachers themselves. The recommendations came from the workshop. (Interview 3)

This specific form of passing on teachers' voices to policy-makers is strengthening the position that local providers build in bridging the gap between policy and practice. However, it remains unclear if these voices will be translated into the policies.

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Intervention TRA has an ambitious task of addressing two aspects of inequalities and education. First, it considers the existing inequalities in the education system, offering guidelines in order to challenge the perceptions, prejudices and discriminatory practices of both teachers and students. With this, it enables education to create freedoms and opportunities for students to benefit from the educational provision in a manner that is just. Second, the intervention also aims at addressing discriminatory practices in the society through education. This aspect supports education systems in developing pupils' capabilities to exercise freedoms, and to recognise the freedoms but also the injustices in the world that surrounds them (Walker & Unterhalter 2007). Therefore, TRA aims at engaging teachers in a twofold manner: teachers are taught how to teach respect and social cohesion, but teachers also learn how to confront their own perceptions and understandings that might be harmful to pupils and to their expected role as agents of social cohesion.

The intervention logic uses the 'Ladder of Inference' that depicts human reasoning before acting. This model shows that we act based on our beliefs. Indeed, many studies have shown that human action results from our deep-rooted beliefs (Richardson 1994b; Kose & Lim 2010). However, it is questionable if this model can be applied in the situation where CPD of teachers aims at changing their beliefs, perceptions, motives and actions. Changing beliefs is a long-lasting and very demanding process. For example, previous studies have shown that reflection is rarely transformative (Husu, Toom & Patrikainen 2008), meaning that even though reflection would bring about insights, it does not necessarily mean that teachers will change their practices or their beliefs. Guskey (2002) further argues that deeply-rooted beliefs can only be changed as a consequence of a new practice that was proved successful. All these studies suggest that changing teachers' beliefs and attitudes is rarely a straightforward action and that as such, it requires cyclical, repeated 'intervention'.

While the programme design relies on teachers' (self-)reflection, in the context of specific South African school-life realities, such as large classrooms and a lack of support (Robertson, Arendse & Henkeman 2015), this might pose a challenge. In addition, teachers' workload and various other demands (e.g. to upgrade their subject knowledge, assessment skills, classroom management abilities, etc.) place a further burden on teachers' time. Thought-provoking questions asked throughout the workshop and in the guide and resource book provide a useful template for guided reflection. However, it is unclear how this is to be enacted and organised in the everyday school life of teachers. Should teachers have a form of professional communities where they have an opportunity to discuss these issues? Or should it occur during their own moments of reflection-on-action? The resource in conclusion recognises that reflection is a process, stating 'teachers, as much as learners, need a safe, trusting and reflective process to become more aware and conscious of what we bring into the classrooms' (IJR 2015, 56).

The small scale of the intervention further affects its impact and sustainability. If the intervention is not systematic and wide-reaching it presents a challenge to meet its own goals of creating a more socially cohesive education system in South Africa.

The limitation of the influence is partially due to the fact that this intervention is provided by an NGO, although it was set up in cooperation with the Department for Basic Education. It is somewhat indicative that state-owned agencies, such as the Cape Teaching & Leadership Institute (CTLI)4 do not offer any course that focuses on inclusive or socially just education. The main focus of the courses provided by CTLI is on mathematics, literacy and leadership skills. Considering that there are numerous policies that set up the landscape where teachers are expected to act as agents of social cohesion, it is to be expected that there should be more systematic support of teachers in terms of their professional development needs.

This study has shown that this intervention has the potential to contribute to educational change in South Africa and building a more socially cohesive society through supporting teachers to act as agents of social cohesion. The potential to achieve this goal is through bridging the gap between policy and practice, contributing to teacher knowledge by introducing the tools that empower teachers to be agents of social cohesion, supporting teachers in becoming more reflective practitioners aware of their own biases, and ensuring that teachers have more continuous support in their everyday challenges. The recommendation of this paper is to take into account the temporal and conceptual challenges of changing professional beliefs, attitudes, and identities that ultimately contribute to changing teachers' pedagogical practices.

Acknowledgment and disclaimer

The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) for the South African Research Chair in Teacher Education towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the authors and are not to be attributed to the NRF or partners.

REFERENCES

Avalos, B. 2011. Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education 27(1): 10-20. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007 [ Links ]

Badat, S. and Y. Sayed. 2014. Post-1994 South African education: The challenge of social justice. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 652(March): 127-148. doi:10.1177/0002716213511188 [ Links ]

Bajaj, M. 2011. Teaching to transform, transforming to teach: Exploring the role of teachers in human rights education in India. Educational Research 53(2): 207-221. doi:10.1080/00131881.2011.572369 [ Links ]

Bennell, P. and K. Akyeampong. 2007. Teacher motivation in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. London: DFID. [ Links ]

Bertram, C. 2014. Shifting discourses and assumptions about teacher learning in South African teacher development policy. Southern African Review of Education 20(1): 90-108. [ Links ]

Brodie, K. 2013. The power of professional learning communities. Education as Change 17(1): 5-18. doi:10.1080/16823206.2013.773929 [ Links ]

Buckler, A. 2015. Quality teaching and the capability approach: Evaluating the work and governance of women teachers in rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Christie, P. 2016. Educational change in post-conflict contexts: Reflections on the South African experience 20 years later. Globalisation, Societies and Education 14(3): 434-46. doi:10.1080/14767724.2015.1121379 [ Links ]

Cordingley, P., S. Higgins, T. Greany, N. Buckler, D. Coles-Jordan, B. Crisp, L. Saunders and R. Coe. 2015. Developing great teaching: Lessons from the international reviews into effective professional development. London: Teacher Development Trust. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2015. Action plan to 2019. Towards the realisation of schooling 2030. Pretoria: Department of Education. Retrieved from: http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/Action%20Plan%202019.pdf?ver=2015-11-11-162424-417 (accessed 16 November 2016). [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education and Department of Higher Education and Training (DBE & DHET). 2011. Integrated strategic planning framework for teacher education and development in South Africa 2011-2025. Pretoria: Government printers. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE). 2001a. Manifesto on values, education and democracy. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE). 2001b. The national policy on whole-school evaluation. 22512. Vol. 433. Pretoria: Government Gazette. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE). 2006. The national policy framework for teacher education and development in South Africa. More teachers; better teachers. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE). 2007. The national policy framework for teacher education and development in South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

du Preez, P. and C. Roux. 2008. Participative intervention research: The development of professional programmes for in-service teachers. Education as Change 12(2): 77-90. doi:10.1080/16823200809487208 [ Links ]

Fazio, X. 2009. Teacher development using group discussion and reflection within a collaborative action research project. Reflective Practice 10(4): 529-541. [ Links ]

Fullan, M. 2007. The new meaning of educational change. 4th edition. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Gatt, I. 2009. Changing perceptions, practice and pedagogy: Challenges for and ways into teacher change. Journal of Transformative Education 7(2): 164-84. doi:10.1177/1541344609339024 [ Links ]

Guskey, T.R. 2002. Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 8(3): 381-91. doi:10.1080/135406002100000512 [ Links ]

Husu, J., A. Toom and S. Patrikainen. 2008. Guided reflection as a means to demonstrate and develop student teachers' reflective competencies. Reflective Practice 9(1): 37-51. doi:10.1080/14623940701816642 [ Links ]

IJR. 2015. Classrooms of hope: Case studies of South African teachers nurturing respect for all. Department of Basic Education and the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

Jancic Mogliacci, R. 2015. Teachers' capability-related subjective theories in teaching and learning relations. Bielefeld: Bielefeld University. [ Links ]

Ketelaar, E., M. Koopman, P.J. Den Brok, D. Beijaard and H.P. Boshuizen. 2013. Teachers' learning experiences in relation to their ownership, sense-making and agency. Teachers and Teaching 20(3): 314-37. doi:10.1080/13540602.2013.848523 [ Links ]

Kirchschlaeger, P.G., S. Rinaldi, F. Brugger and T. Mitrovic. 2013. Teaching respect for all: Mapping of existing materials and practices in cooperation with universities and research centres. Final report. Centre of Human Rights Education (ZMRB) and University of Teacher Education Central Switzerland Lucerne (PHZ Lucerne). Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Korthagen, F.A.J. 2004. In search ofthe essence of a good teacher : Towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education 20: 77-97. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2003.10.002. [ Links ]

Kose, B.W. and E.Y. Lim. 2010. Transformative professional development: Relationship to teachers' beliefs, expertise and teaching. International Journal of Leadership in Education 13(4): 393419. doi:10.1007/s11256-010-0155-9 [ Links ]

Le Roux, A. 2011. The interface between identity and change: How in-service teachers use discursive strategies to cope with educational change. Education as Change 15(2): 303-16. doi:10.1080/16823206.2011.619142 [ Links ]

Mayring, P. 2000. Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 1(2). [ Links ]

Miles, M.B. and A.M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [ Links ]

National Planning Commission (NPC). 2012. National development plan 2030: Our future - Make it work. Retrieved from: http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/Executive%20Summary-NDP%202030%20-%20Our%20future%20-%20make%20it%20work.pdf (accessed 5 November 2016).

OECD. 2005. Teachers matter: Attracting, developing and retaining effective teachers. Education and Training Policy. Paris: OECD. [ Links ]

Pang, V.O. and C.D. Park. 2003. Examination of the self-regulation mechanism: Prejudice reduction in pre-service teachers. Action in Teacher Education 25(3): 1-12. doi:10.1080/01626620.2003.10734437 [ Links ]

Pantic, N. 2015. A model for study of teacher agency for social justice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 21(6): 759-78. [ Links ]

Richardson, V., ed. 1994a. Teacher change and the staff development process: A case in reading instruction. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Richardson, V. 1994b. The consideration of teachers' beliefs. In Teacher change and the staff development process. A case in reading instruction. Edited by V. Richardson, 90-108. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Robertson, M., L. Arendse and S. Henkeman. 2015. Lessons in respect: Building respectful schools and inclusive communities through education. The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

Schreier, M. 2014. Qualitative content analysis. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. Edited by U. Flick, 170-83. Los Angeles: SAGE Publishing. [ Links ]

Sedova, K., M. Sedlacek and R. Svaricek. 2016. Teacher professional development as a means of transforming student classroom talk. Teaching and Teacher Education 57: 14-25. [ Links ]

Stake, R.E. 2008. Qualitative case studies. In Strategies of qualitative inquiry. 3rd edition. Edited by N.K. Denzin and Y.S. Lincoln, 119-W. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Timperley, H., A. Wilson, H. Barrar and I. Fung. 2007. Teacher professional learning and development: Best evidence synthesis iteration (BES). Wellington: Ministry of Education. [ Links ]

UNESCO. 2014a. EFA Global Monitoring Report 2013/4 - Teaching and learning: Achieving quality for all. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

UNESCO. 2014b. Teaching respect for all: Implementation guide. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Walker, M. and E. Unterhalter. 2007. The capability approach: Its potential for work in education. In Amartya Sen's capability approach and social justice in education. Edited by M. Walker and E. Unterhalter, 1-18. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Weber, E. 2008. The scholarship of educational change: Concepts, contours, and contexts. In Educational change in South Africa: Reflections on local realities, practices, and reforms. Edited by E. Weber, 3-22. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Weldon, G. 2010. Post-conflict teacher development: Facing the past in South Africa. Journal of Moral Education 39(3): 353-64. doi:10.1080/03057240.2010.497615 [ Links ]

Yin, R.K. 2009. Case study research: Design and methods. 4th edition. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

1 The fundamentals are: (1) Democracy, (2) Social Justice, (3) Equity, (4) Non-Racism and Non-Sexism, (5) Ubuntu (Human Dignity), (6) An Open Society, (7) Accountability (Responsibility), (8) Respect, (9) The Rule of Law, and (10) Reconciliation ( DoE 2001, 3).

2 The Toolkit comprises a set of guidelines that help teachers in identifying their own biases, creating safe spaces for dialogue, creating an environment of equality and fairness, and creating opportunities for learners to engage with people who are different from themselves. These guidelines are now part of the Resource book (IJR 2015, 50-53).

3 These interviews were gathered as part of the project on 'The role of teachers and youth in peacebuilding and social cohesion' by the Centre for International Teacher Education.

4 http://www.wcedctli.co.za/courses (accessed 29 August 2016).