Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 n.3 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/1314

ARTICLES

Shifting the future? Teachers as agents of social change in South African secondary schools

Christina Lane Cappy

University of Wisconsin-Madison Email: cappy@wisc.edu

ABSTRACT

South Africa has risen to the forefront of educational debates that claim schooling can promote social justice and social cohesion. By drawing on Freire's (1970) theory of critical pedagogy, this paper examines how South African teachers in rural and township schools encourage students to reflect critically upon their own lives and take action to improve issues of inequality, violence, and insecurity. It argues that teachers understand their roles as agents of social change primarily as encouraging respect, morality, and racial reconciliation among learners. The ways in which the youth take up the teachers' efforts to promote change depends upon how the teachers' practices speak to the students' own life circumstances. When the youth relate to the teachers' life stories and course material, they engage in the process of moral translation. In other words, the youth rework their lessons into ideas of how they should behave as moral human beings. Yet, frequently young South Africans do not learn a morality based on a Freirean notion of social justice - a seemingly central component to the national curriculum - but instead a morality based on individualised notions of personal responsibility and hope for a better future. The paper concludes with several suggestions to improve educational practices for social justice.

Keywords: social justice; morality; critical pedagogy; South Africa; collective action; secondary education

Mrs Magwaza entered the classroom and began the first eleventh grade History class of 2014 in a direct way: 'Let's go straight to page 1'. She passed out copies of New Generation History (2012) so there was one shared textbook among three students. Despite sitting in a crowded classroom, the students listened quietly as their teacher continued. Mrs Magwaza started talking about communism and capitalism in preparation for a segment on Russian history.

'I'm trying to show the characteristics of capitalism, so we can learn the characteristics of communism. Most of the capitalists ended up being so rich that the workers, or proletariat, were exploited. How were they exploited?'. A male student explained that they are exploited because they get low wages. 'Yes - workers ended up poor because they earned low wages. By the way, what is capitalism?'. A female student read a definition from her book, then the teacher discussed the characteristics of capitalism.

'That means communism was there to address the inequality in the country...In communism the workers control the means of production...Here in South Africa we are using capitalism together with communism. Education and justice are in the hands of states, but other things are capitalism. Some countries adopt only one economic system, but other countries they adopt two. In communism all are equal with wealth. Is this the same way here in South Africa?'.

Mrs Magwaza reiterated these points in Zulu so that all of the students understood. Another male student responded that this is not the case in South Africa because some factories are not under control of the state. She agreed and then gave an example of how there are South African workers in gold mines, but the gold goes to the US and then it becomes American Swiss gold chains and watches. South Africans do not benefit, she asserted.

She continued, 'But you can change that, you. You can take back the American Swiss and make it African Swiss...If you are working for the government you can't have your own business...But you can have people who are richer in South Africa because they own their companies and businesses and farms, and people are exploited by them'.

In a context of high levels of inequality and racism, South African education has been publicly tasked with promoting social justice, democracy, and social cohesion. While curricula and textbooks were re-written after apartheid to reflect the values of the new country, teachers play an oft-underappreciated role in fostering social change. As the excerpt above illustrates, this task is not lost upon many. Teachers like Mrs Magwaza recognise their central role as influential educators of the next generation of South African citizens. Through pedagogical practices that encourage reflection on students' environments, teachers may promote social transformation and help develop respect for others.

This paper draws on Freire's (1997 [1970]) theory of critical pedagogy to examine how South African teachers in low-income schools encourage students to reflect critically upon their own lives and take action to improve issues of inequality, violence, and insecurity. I ask the following questions: (a) how do teachers understand the role of education in creating social change, (b) how do their understandings shape their instructional efforts, and (c) how do students take up teachers' efforts to promote social change?

Based on fifteen months of ethnographic research in three rural and township schools in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, I argue that teachers understand their roles as agents of social change primarily as encouraging respect, morality, and racial reconciliation among learners. The ways in which the youth take up teachers' efforts to promote change depends upon how teachers' practices speak to students' own life circumstances. When the youth relate to teachers' life stories and course material, they engage in the process of moral translation. In other words, the youth rework their lessons into ideas of how they should behave as moral human beings. Yet, more often than not, young South Africans do not learn a morality based on a Freirean notion of social justice - a seemingly central component to the national curriculum - but instead a morality based on individualised notions of personal responsibility and hope for a better future.

This paper offers two contributions to debates on education for social change. First, it demonstrates that while some teachers agree with the South African curricula that education should foster social change, their understandings do not translate into encouragement of collective action. And second, by examining how the youth in rural and township schools engage in processes of moral translation, it illuminates the challenges and potential of education to foster social transformation within unequal contexts globally. By drawing on findings from this case study, this paper offers several suggestions to improve educational practices for social justice.

TEACHING TOWARD TRANSFORMATION: FREIREAN CRITICAL PEDAGOGY

Scholars have long recognised that education is not politically neutral. Social reproductionist theorists have highlighted how schooling can reproduce racial and economic inequalities (Bourdieu & Passeron 1977; Bowles & Gintis 1976; Foucault 1991 [1977]; Willis 1981 [1977]). They have demonstrated that despite a liberal discourse that proclaims education is based on meritocracy and can lead to social mobility, it has the converse effect in practice. Yet, other scholars have demonstrated education's emancipatory potential and ability to produce critically engaged human beings (Apple 2010; Bush & Saltarelli 2000; Cole & Murphy 2010; Dewey 1916; Freire 1997 [1970]; Giroux 2005; Greaney 2006). While critical and cautionary of the ways in which schooling can support oppressive power structures, these scholars argue that education can also transform society to create a more socially just world.

Brazilian educator and theorist Paulo Freire recognised this dual potential of education. In his seminal work, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), he argued that although education often serves to maintain oppressive social orders, education may also be used to liberate people and transform society. Freire held that a person's vocation is to create humanisation (1970, 25) - to live a fulfilled life based on equality and responsibility to those around them. Drawing on Beldo's (2014) definition of morality as an 'unconditional ought', I argue that Freire's philosophy holds a moral imperative that education must create a better world. Freire's philosophy does merely suggest that education could be transformative, but demands that education foster transformation. He supported critical conscientisation through education, wherein people reflect upon their social situation so they may envision both individual and collective actions that can be pursued to improve their humanity and the humanity of those around them.

Freire's advocacy of education to further humanisation corresponds with contemporary arguments of the need for education to foster social change through development of 'peacebuilding and social cohesion'. As Sayed and Novelli (2016, 14) highlight, some may think that calls for peacebuilding and cohesion entail having respect for difference and how the 'other' thinks, yet they suggest these terms require the confrontation of historic inequities and drivers of conflict. The 'strong' perspective of teaching for social cohesion entails not only fostering feelings of trust and inclusion, but also addressing structural inequalities (Sayed & Novelli 2016, 35). Social justice is therefore central to this framework, just as it is in Freire's argument that education should encourage reflection and change unequal social structures. Throughout this paper, rather than situate my analysis using strict definitions of contested terms like social cohesion, I examine how teachers employed themes inherent in these concepts when discussing their role as educators to promote change - for instance, how they viewed their jobs as fostering a shared identity, trust, and/or structural equality.

In addition to presenting a framework for the purposes of education, Freire advocated several pedagogical techniques to foster critical consciousness and collective action. He was highly critical of what he termed 'banking education', wherein teachers are seen as depositing knowledge and skills into students. Through banking, students are presented as 'objects' in the world to be integrated into society and structures of oppression, rather than subjects who can transform their world (1970, 53-5). Freire instead encouraged dialogue and problem-posing as pedagogical techniques to foster social change. While dialogue sets teachers and students on equal footing, problem-posing engages people to recognise their social 'situation' that may be hindering their humanity, and then discover possibilities for change. These processes of reflection and action directed at transforming social structures occur simultaneously. Inherent in Freire's emphasis on pedagogical practices is an understanding that teachers are in a unique position to act as agents of change to further efforts of social justice.

Many scholars have explored the dimensions that enable or constrain teachers' agency to affect social change (Bartlett 2005; Bush & Saltarelli 2000; Horner et al. 2015; Priestley, Biesta & Robinson 2013; Sayed & Novelli 2016). Like education more broadly, scholars have noted that teachers may act as agents of social equality and justice, or as agents of conflict (Sayed & Novelli 2016, 36). They can promote inclusiveness among pupils, or encourage social divisions based on ethnic, religious, racial or gender differences, among others. Moreover, as Priestley et al. (2013) detail, teachers adopt goals that may be long-term oriented like promoting social justice, or short-term goals such as maintaining a normal classroom state. Their future orientations shape the strategies they adopt in the classroom. And finally, teacher agency - be it to promote equality, conflict, or class order - is conditioned in different ways according to their social, political, economic and cultural contexts (Priestley, Biesta & Robinson 2013; Sayed Novelli 2016). Teacher agency may be constrained or facilitated by their environment, including class size, violence, low wages, educational curricula, political adgendas, and exclusion or inclusion from decision-making concerning educational policies. These historical and contemporary structures restrict or enable certain options available for teachers to enact their agency.

While Freire has inspired educational reforms around the world, he has also been criticised for universalist thinking that ignores variations of different socio-historical contexts, as well as issues of race and gender (Coben 1998). These critiques point to Freire's inspirational goals rather than clear directives, and the challenges of applying his overarching methodology of conscientisation. However, many scholars have built upon his notions of dialogue and problem-posing to examine a broad range of social inequities and possibilities for change in unequal contexts.

In South Africa, critical pedagogy has inspired a range of educational interventions, community-based research projects, and debates (Balwanz & Hlatshwayo 2015; Davis & Steyn 2012; Jackson 1997; Pillay 2014; Thomas 2009; Singh & Francis 2010). These studies have evaluated the use of critical pedagogy to address inequities of race (Davis & Steyn 2012), xenophobia (Singh & Francis 2010), and class (Balwanz & Hlatshwayo 2015). They point to the possibilities of using pedagogies that draw on collaboration, critical reflection, and problem-posing to foster social justice in unequal societies. Yet, while case studies have examined the merits and limitations of critical pedagogies in South Africa, many remain centred on higher education (Davis & Steyn 2012; Pillay 2014; Singh & Francis 2010). Educators and researchers in institutions of higher education have many more resources and opportunities in their educational environments than educators from low-income schools. Because teacher agency is conditioned by context, teachers' ability to enact positive transformation may be very different in disadvantaged schools.

Below I examine South Africa's historical and educational context that frames teachers' understandings of their role as agents of change, as well as their ability to foster social change. I use Freire's theory of critical pedagogy - and ultimate goal of education to improve humanity - as a backdrop against which to understand how teachers enact their agency. Through ethnographic fieldwork in historically black and low-income schools in the country, this research sheds light on contemporary practices and possibilities of teachers to act as agents of positive transformation.

FROM SEPARATENESS TO SOCIAL JUSTICE: THE HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN SOUTH AFRICA

The South African government's assertions that education should contribute to reconciliation and social justice must be understood against the backdrop of the country's turbulent and divisive past. Under apartheid South Africa, rather than promote equality, education functioned to differentiate people according to race. All people were labeled as white, black, coloured, or Indian and were required to attend racially segregated schools. Resources were allocated unequally, with white schools receiving the greatest resources and black schools the fewest. This differential allocation of resources provided white students with an education that could lead them to higher paying jobs, whereas black students' education perpetuated their lower economic status (Fiske & Ladd 2004).

Not only did apartheid education prepare black students with a manual education and service-work skills for white-designated areas, but curriculum content served to justify this unequal social order. Specific courses, such as History, taught Afrikaner volk nationalism, which presented whites as superior and blacks as inferior (Engelbrecht 2006). Rather than learn critical citizenship, non-white students were encouraged to submit to their subservient position as part of a natural social order. Apartheid educational ideology and practice further supported autocratic relations in schools, whereby order and discipline trumped democratic practices of schooling (Hunt 2011).

Despite government attempts to use schooling to maintain such an unequal social structure, many students and educators during apartheid sought to use education to transform society. For instance, Naidoo (2015) traces how Freirean-inspired radical pedagogy was used by the South African Students Organisation (SASO) and the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) in the 1960s and 70s. SASO emphasised the role of self-reflection through education; they wanted black students to think for themselves and recognise their role as citizens (Naidoo 2015, 117). Although Naidoo further highlights how the Freirean emphasis on critical reflection fell in tension with student movements that pushed forward a specific political agenda to end apartheid, her research demonstrates how critical reflection and action may exert positive transformations in society - and ultimately social justice.

Following the end of apartheid in 1994, the new South African government publicly embraced the transformative potential of education in policy discourse. Whereas education under apartheid promulgated racial exclusion, the new government has promoted education as a means to redress past inequalities and promote values of the new democracy. One of many influential publications, the Manifesto on Values, Education, and Democracy (2001) detailed the values that South African education should uphold, including: democracy, social justice, equality, non-racism, non-sexism, Ubuntu (human dignity), an open society, accountability (responsibility), the rule of law, and reconciliation. The manifesto continues to be a foundational framework for educators in South Africa today with words and images of these values speckling the walls of teachers' offices.

South African educational policy documents stress some subjects as promoting key values (including social justice) more than others. For instance, the national curriculum framework, called the National Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), highlights how History for grades 10-12 should support democracy by:

Upholding the values of the South African Constitution and helping people to understand those values; reflecting the perspectives of a broad social spectrum so that race, class, gender and the voices of ordinary people are represented; encouraging civic responsibility and responsible leadership, including raising current social and environmental concerns; promoting human rights and peace by challenging prejudices that involve race, class, gender, ethnicity and xenophobia; and preparing young people for local, regional, national, continental and global responsibility. (DBE 2011, 8)

The language used above reveals several components also found in critical pedagogy -namely, that education should encourage students to reflect on social issues so that they may become responsible citizens and leaders that uphold the value of human rights.

Yet, while educational institutions and specific courses are now expected to promote equality and human rights, South Africa's contemporary education system is bifurcated - consisting of high performing former white and private schools on one side, and poor quality former black schools on the other. During the transition from apartheid, former white schools opened their doors to pupils of all races, while semi-privatising, charging school fees, and accepting learners on the basis of exams determined by individual school governing bodies (Motala 2008). Consequently, they have continued to exclude the most underprivileged learners despite becoming multi-racial institutions. Through school fees former white schools have hired additional and better-trained teachers, while most former black schools remain racially segregated and continue to face high student to teacher ratios with under-qualified staff. This situation is exacerbated in rural areas, where employment in local schools is viewed as a last resort for newly trained teachers (Bantwini 2010). Moreover, students and staff in non-white schools are often faced with violence, either from community members or corporal punishment (Davids & Waghid 2016). These factors of violence and overcrowded classrooms serve to constrain teachers' agency in former black school to enact their professional goals. Although contemporary pro-poor policies direct more state funds to schools in poor, typically all-black neighborhoods, learners in former white schools continue to outperform their peers in former non-white schools (Sayed & Motala 2012). As a result, young people that pass through South Africa's education system will experience dramatically different life trajectories, raising important questions about how teachers and young people understand the role of education in fostering social transformation.

METHODS AND FIELD SITES

As part of a larger project to examine how the youth learn values and morality through schooling, I analysed how teachers recognise and act upon their role as agents of social change through fifteen months of ethnographic research in three schools in KwaZulu-Natal. The schools were selected due to their varied levels of urbanisation (rural, peri-urban, urban), mid-range matric pass rates (40-80%) when compared to the national average, as well as their historical denotation as black or African schools. Rather than strive to draw comprehensive comparisons across these field sites, my goal in selecting these sites was to develop a fuller understanding of how teachers and the youth in the most common schools in the country learn values and ideas of how they might transform their environments. By drawing on data across schools I was better able to examine pedagogical techniques that could foster social change.

These historically black, and still all-black, schools face challenges of poverty, insecurity, and violence on a daily basis. The rural school, Ikwezi High School1, lacked running water and educational resources, including textbooks and computers. Most of the students were living with distant relatives who were primarily supported by government social grants. Students at the peri-urban school, Entabeni Secondary School, often lived with one wage-earning family member, and the community was fraught with gang violence. Teachers and students alike lived in fear of the violence, which made teaching and learning at times inconceivable. Siyabonga High School, an urban school near Durban, boasted the greatest resources among these schools, including a computer lab and science lab, yet still had to navigate challenges of violence, drugs, poverty, and abuse from the surrounding community. Investigating the possibilities and limitations of how educational processes may help create critical citizens who transform society is of vital importance in communities where change is not just an abstract ideal, but an imperative for people to live fulfilling lives.

In each site, I conducted participant observations, classroom observations, focus groups, and interviews with teachers and students in order to understand how people learn values and actions for social change. I observed Grade 11 English, History, and Life Orientation (LO) classes, focusing particularly on how teachers encouraged shared values through selection of course material and teaching methods, and how students responded to their efforts. During these subject periods, I would sit on the benches with students and take handwritten notes of class exercises. I also attended school activities including morning assemblies, cultural activities, matric balls, debate team events, and football matches, as these extracurricular activities can be as important as classroom practice in fostering social cohesion.

All interviews and focus groups were conducted after at least six weeks of classroom observation in order to limit the influence of my research topic on teaching practices, allow me to ask contextually specific questions, and develop rapport with teachers and students. Interviews and focus groups were ongoing while I conducted an additional two months of classroom observations. Teacher interviews aimed to uncover how teachers understand the role of education to create social justice and cohesion, as well as the challenges they encounter in their everyday practice. These semi-structured interviews further allowed teachers to communicate topics of interest to them.

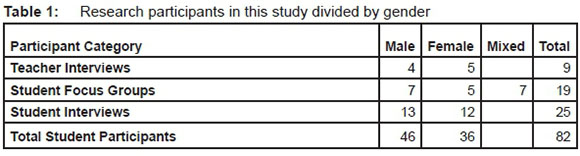

Student interviews and focus groups centred on how participants experience interactions with members of their community and values they learn in school. For instance, I asked students to reflect on specific class exercises to examine how they felt they learned values described in policies (democracy, non-racism, social justice) and other values that learners raised (respect, obedience, generational divisions). Each focus group met from one to three times, depending on student interest, with follow-up sessions aimed at clarifying ambiguities and expanding on initial themes. Student interviews were conducted after a student had participated in a focus group. In these open-ended interviews I simply asked students to tell me about their lives, which resulted in a wealth of information on students' everyday life experiences, hopes, dreams, and challenges that they sought to overcome. See Table 1 below for the number of male and female teacher interviews, as well as student focus groups and interviews conducted for this study. All interviews were conducted in English and Zulu, and recorded with participant permission. They were later transcribed and coded for prominent themes. These in-depth methods allowed me to see not only what teachers assert as their role in education for peace, but how they act upon their beliefs within the constraints of their environments.

I felt that my status as a white female in racially charged environments at times created barriers between myself and students and staff. When I first arrived at each site, students were more likely to address me as 'umlungu' [white person], but after a few weeks they transitioned to calling me by my first name. Over time I learned that many students thought that I was two to three years older than themselves, which in the case of the older students was true. Because many of them had siblings my age, and due to my proclaimed status as a student (albeit graduate student), most youth regarded me as an older peer mentor rather than a teacher. Many teachers likewise treated me as a 'student-teacher', offering me details of their teaching experience with less fear of repercussions from their superiors. In addition, my identity as an American allowed me to distance myself from historical and racial issues in South Africa, while my use of Zulu and the fact that I was living in the communities surrounding the schools (often with teachers) enabled me to develop a positive rapport with students and staff.

TEACHING FOR SOCIAL CHANGE? TEACHERS' PERSPECTIVES

I think respect is one of the important values that our learners should have... Maybe I'm doing like a poem, a poem that will touch something in respect or comprehension, that will touch something in being accountable. So they are interpreting just like that. And then you go further and talk about accountability in their own lives now.

(Mrs Nkosi, English teacher at Ikwezi High School)

Many of the English, Life Orientation and History teachers perceived their role as agents of social change by teaching students how to live and behave in the world -both through curricular content and their pedagogical practices. Most of the teachers described how they believed education in general, and their instruction in particular, should shape students' individual behaviour so that they could distinguish between 'right and wrong', respect others, and encourage racial reconciliation.

Four of the nine teachers interviewed for this study asserted that they believed 'respect' was the most important value that students should learn through education. Hammett and Staeheli (2011) critically note that South African teachers tended to emphasise respect in a unidirectional, and unequal manner. I too found this trend; most teachers told students to respect (and obey) their teachers as figures of authority without highlighting their responsibilities as educators towards their students. Yet, some also explained that students should respect themselves, as well as their peers. As Mrs Nkosi, the English teacher at Ikwezi explained, '[I]f they respect themselves they will know how to respect other people. And if they are respecting they can go a long way in life'. Other teachers, like the LO teacher at Entabeni highlighted how learning to respect could 'alleviate the problem of discriminating against other ethnic groups. Because if I respect you, I tolerate your values and principles as well'. Teachers stated that they would spend a few minutes every lesson deliberately telling student that they should learn respect - a practice that I observed during classroom sessions and morning assemblies. This practice of encouraging respect reflects teachers' short-term goals of maintaining school order, as well as longer-term goals of fostering social cohesion.

This theme of respect fed into teachers' assertions that as professionals they seek to encourage racial reconciliation specifically. This idea was particularly pronounced among History teachers, who held that the content of the material they taught was vital for the future of South Africa. Mrs Magwaza highlighted how History should encourage the youth to know their past so that they can learn to 'treat each other equally...Not to go back and pay revenge' on white people. Similarly, Mr Shabalala at Siyabonga High thought History was a vital subject to encourage 'unity and good social structure'. He explained that by knowing their history the youth could learn that, 'there is no difference between me and a white person. It's just that it's a matter of color, but we're both the same'. Mr Shabalala further explained that in school students learn how to communicate with people of different races. He gave the example of different connotations of eye contact between white and black people to illustrate his point. If a person is educated, they will know that a white person looking a black person in the eye is not a sign of disrespect, but rather understanding. This same point was independently stated by Mr Dumisa, the English teacher at Siyabonga who enjoyed teaching language through historically derived short stories.

All of these excerpts above highlight how most teachers considered their ability to promote social cohesion by transforming individuals' actions. They focused on morality and behaviour, emphasising how students learn to get along with others through education. Yet only a few teachers considered the role of education in shaping social structures more broadly to encourage social justice, and rarely commented on their role as educators in fostering such structural changes.

Most often, when teachers contemplated how education leads to a more equitable society, they commented on school fees and educational access. They felt that education could help learners 'make something better in the world' and explained that the government was trying to promote equality and social justice by enabling access to education. However, many questioned the efficacy of these attempts. Mrs Nkosi explained, 'There shouldn't be...schools that are full of resources and rural schools like this which do not have all the resources. So in fact, that is what our education system is trying to close the gap between the ex-Model C schools [former white schools] and these schools in rural areas. So there should be social justice and equity'. Mrs Nkosi also recognised that she was working in a school without running water and limited educational supplies. She regularly critiqued the government for 'losing money' that was supposed to support teachers and students.

Mr Dumisa likewise felt that while the government was trying to promote 'social cohesion', this could not be achieved while such inequalities in education remained. He stated that the government was trying to improve educational access, yet differences in school fees were creating separateness in society. He clarified,

We are paying 300 rand a year here, they are paying 50,000 rand a year there, so...there will always be that tension, up until maybe...everybody in South Africa is paying one and the same fee. They are going into one and the same school, then I think social cohesion will be something that is there and people are adhering to it. So rather than seeing these two worlds in one.

Like teachers in Hammett and Staeheli's (2013) study, these teachers were critical of how impoverished schools were negatively affecting students' status as empowered citizens who could take control of their futures. Furthermore, while they critically considered how social justice and social cohesion might be fostered through education, they did not explicitly state their attempts to encourage change to an unbalanced social structure based on 'two worlds'. In fact, the only teacher who explicitly addressed her role in fostering change to make society more equitable was Mrs Magwaza. She felt that as a History teacher she could mold students into 'true leaders', and regularly directed students to their potential to transform South African social and economic structures. Yet she was the exception.

A few teachers remained disillusioned with how education could lead to social change. These teachers either shifted attention to how other subjects could encourage change, or openly admitted their intentions of coming to school were just to receive their paycheck. For example, Mrs Ngcobo, the English teacher at Entabeni, believed that her school did not contribute to a culture of learning. She asserted that, 'We [the teachers] tried a lot, but now we are fed up...I just wait for the 15th to get paid and live my life'. Within a school environment that faced challenges of extreme violence, many students felt hopeless in their abilities to transform their futures - and even afraid to attend school. Mrs Ngcobo, like many teachers, felt overwhelmed by these circumstances and fell into a state of apathy about her role as an educator. Rather than attempt to address the school and community violence, many teachers chose to refrain from striving to critically challenge these issues.

This discussion reveals that, like Freire, most teachers recognised the potential of education as an institution to create a better world for humanity. However, their views of how they may help create a better world differ from Freirean philosophies. Freire sought to encourage critical reflection on students' situations to foster social change that would lead to all persons' greater humanity based on equality. These teachers, in contrast, felt that the government was primarily responsible for expanding educational access so that disadvantaged, black youth would have job opportunities and learn to live peacefully in a multiracial nation. Most teachers viewed their role in promoting social change as teaching about values of the new democracy (such as respect and equality), rather than inspiring critical reflection on collective action that the youth could take to transform the world around them.

PEDAGOGICAL PRACTICES TO PROMOTE CHANGE

Teachers who recognised their role as agents of change primarily practised three pedagogical forms: narrative instruction on what students should do, use of personal stories and materials to elicit emotional responses, and encouragement of debate on social issues. The three pedagogical practices were often intertwined throughout each lesson, however by far the most common practice was narrative instruction - or telling students what to think and how to act. The opening excerpt of this paper wherein which Mrs Magwaza instructs students, 'But you can change that, you. You can take back the American Swiss and make it African Swiss', offers an example of narrative instruction. However, Mrs Magwaza's statement differs from other teachers' forms of narrative instruction in that she is telling students to influence social and economic institutions as future leaders of the country. Most teachers, in contrast, instructed students on their individual behaviour.

Ms Zuma, the LO teacher at Ikwezi, regularly told students what they should do in order to pursue their future careers. She focused primarily on individual behaviour, telling students 'You need to decide your goals'. Her statements were supplemented with notes on the board that students wrote in their notebooks. Other LO teachers engaged in similar narrative practices, yet when they covered topics of democracy and human rights - modules that consider collective action - they frequently had students copy notes without supplemental discussion. Their lessons focused on the memorisation of terms rather than how such concepts can be practised.

Other teachers, like Mrs Nkosi, told students how to act as individuals through narrative instruction and literature selection. In one class she asked students to read aloud an article on teenage pregnancy, while simultaneously instructing students on the social consequences of pregnancy. She explained, 'When you do these things [engage in sexual activities] you are with your friends, but when you fall pregnant all your friends will run away from you...The mother cannot keep friends because after school she has to look after her child'. As with Ms Zuma, she seeks to 'change' the young students by instructing them in how to live in moral ways. Yet, the way she instructed them how to live morally was through fear. Rather than empowering young people, her words seek to control them through assertions of how to live in the current world.

Moreover, Mrs Nkosi's attempts to encourage moral behaviour served to reinforce gender inequities felt by many young students. As Bhana and Mcambi (2013) highlight, girls in a Durban school experienced stigma and shame from pregnancy. The responsibility and stigma rested upon the young mothers far more than the fathers in their study, which was also the case in my field sites. Teachers were active in regulating these gender inequities, either by negatively blaming young women (and rarely young men) for 'irresponsibly' becoming pregnant to their face or during morning assemblies, or through lessons in the classroom. Although teachers in this study encouraged class participation and the pursuit of higher education from both male and female students, many teachers like Mrs Nkosi presented the 'problem' of sexuality and pregnancy as solely female responsibilities. These trends occurred with both male and female teachers. My classroom observations did not discern distinct differences between how teachers of different genders treated learners of different genders in the classroom. Yet, in many cases, rather than act as agents to encourage critical reflection on contemporary gendered inequities, teachers used their agency to uphold discriminatory gender norms.

While teachers like Mrs Nkosi sought to promote change by shaping individual behaviours, their pedagogical practice of narrative instruction actually hindered students' critical reflections on their own lives. In the words of Freire, this form of education suffered from 'narration sickness', or excessive banking (1970, 53), which may result in a 'dead zone' of critical thinking and self-reflection (Giroux 2005, 715). Students were being told how to 'fit' better into the world, rather than to reflect on their position within it, what should be changed, and how to change it. Although Lazar (2010) found that such banking methods do not necessarily preclude the development of critical citizenship in Bolivia, they do not necessarily encourage it either.

A second pedagogical method that teachers employed was the use of personal stories and literature to elicit emotional responses from students. Some teachers used their life histories as examples to help students reflect on their own lives and sway them to behave in certain ways. As Dryden-Peterson and Sieborger (2006) also found, such personal narratives have particular power in reaching an audience on a 'human level' in South Africa (401). At Entabeni, Mr Mbatha reiterated throughout his History classes how he had other dreams in life than to be a teacher, but due to the oppressive structure of apartheid he was unable to pursue these dreams. After explaining the unequal Bantu education system that was in place throughout the 1950s-80s, he stated, 'You all are so fortunate. I wanted to be a doctor. But to be a doctor you have to do Mathematics and Physical Sciences, but black people were not offered Physical Science in their schools. Certain jobs were reserved for white people only, like being a doctor, so I could not become a doctor'. While this emotional appeal encouraged students to consider historical and structural inequities in South Africa, Mr Mbatha's statement directed students to be thankful for what they have rather than to consider contemporary issues and ways to create social change. Students later reflected on his story and the opportunities that the younger generation have in comparison to the older generation. They considered how they should take advantage of their position, although they often admitted they did not think the youth were doing this.

Some teachers elicited emotional responses from students not through their personal stories, but through their selection of course material. This practice was most commonly employed by English teachers who had flexibility in the selection of literature. For example, Mrs Ngcobo at Entabeni had the students read a poem called Shantytown, by Anonymous. This poem described life in a shantytown - the dirt, the violence, the hunger - as well as the hope that one day the land would change and be filled with joy and laughter. Many students had grown up in, and were living in, areas similar to the shantytown described in the poem. While they were generally rowdy during English class, at times chatting over the teacher, they remained quiet throughout the reading of this poem. Although Mrs Ngcobo stated that she simply selected materials that students 'could relate to' rather than to encourage certain values or social change, students often reflected on how the exercises she chose taught them how to live. Mr Zuma at Siyabonga likewise selected short stories that were based around Durban, where the students lived, that highlighted South Africa's violent past, which elicited emotional responses from students during our focus groups, as well as critical reflection on social structures.

A third pedagogical method utilised by teachers to foster social change was in-class debate on social issues. Although this method was infrequently used, it resonated with students for longer after the lesson, as will be discussed below. Mr Shabalala encouraged debate more than other teachers, and acted as a moderator throughout the discussions. In contrast to Hemson's (2006) findings that South African teachers shied away from polarising material, Mr Shabalala was not hesitant to open discussion on controversial issues of race. In one History class the students continued on a segment of Afrikaner nationalism, raising and debating controversial issues. After lecturing for the first half of the class, Mr Shabalala asked students to debate whether it was fair that white people, and Afrikaners in particular, should come into the country and fight. Half of the students emphasised the view that Africa should have been for Africans and settlers had no right to come here and change the way of life, whereas others said that they (white people) discovered things we (black South Africans) didn't even know existed and made inventions so it was OK. One female student proclaimed that South Africa is a land for all who come here. Mr Shabalala at times called on students, but for the most part allowed them to discuss the issue among themselves. At the end of the lesson he emphasised, as he did in other lessons, that the point of learning history was to understand why society is the way it is and that everyone should unite as South African citizens. In other classes he reiterated this statement with pictures of young people of different races visibly enjoying themselves and getting along.

This practice of open debate allowed students to consider how certain economic and social institutions had come to be the way they are today. It allowed for critical reflection on the contemporary status of inequality. These findings support previous studies that have argued for the importance of exploring uncomfortable topics in the classroom to foster critical reflection and social change (Singh & Francis 2010; Davis & Steyn 2012). However, as Postma, Spreen and Vally (2015) noted in their examination of how education encourages social change in South Africa, these debates largely focused on racial factors and ignored class issues. Additionally, like the other pedagogical techniques, gendered experiences and inequities were absent from historical debate exercises. And finally, while this form of debate promoted reflection on certain issues of social justice, it did not ultimately translate into forms of social activism. Similar to Parker's (2006) study of the use of critical teaching methods such as the Socratic Circle, these debates encouraged students to take charge of their learning but it did not necessarily foster 'action-in-the-world'. The history of the country was contemplated and students later reflected on how they should act as individuals, but discussion of how to change social inequities was masked by the emphasis on reconciliation.

YOUTH PRACTICES OF MORAL TRANSLATION

The ways in which students responded to lessons to promote social change depended on how the classes spoke to students' own life experiences. When course material and teaching methods related to students' day-to-day lives, they would engage in the process of moral translation. In other words, students would take lessons from the classroom and translate what they had learned into ideas of how they ought to behave and live as good human beings.

Many students endured situations of poverty and insecurity, and they felt that their English and History classes addressed their circumstances far more directly than Life Orientation (LO) material. While they recognised that LO was supposed to teach about values in life, particularly equality, many students felt that the class did not teach them anything new. In contrast, many students thought that what they were learning in English and History actually addressed their lived experiences. During our focus groups students reflected on their favourite class exercises and highlighted how certain lessons - as well as pedagogical practices - connected to their own lives and shaped their views of right and wrong behaviour.

At Entabeni, a group of male students called out the English exercises that they liked the most - these exercises ranged from the Shantytown poem to a story about an apartheid era political prisoner who endured his incarceration with dignity and wit. Shabeni (20m) articulated why he liked these exercises:

It taught us something in life that the prisoner who wore glasses, he taught me something, that in life you must never give up. Even if you are in a hard situation you must believe that one day I will rise up...Like the person who wrote that poem he has a hope that one day he will get out there. And one day he will live a better life. He is a good believer.

To provide a bit of background on Shabeni's life - he had lived a life of poverty, loss and violence. He told me his life story and one of the first things that he said was, 'Ah there is a lot of violence at the school. If you are learning at Entabeni, every time you are always scared. You are always scared that they fight to you'. In addition to fear of violence at school, Shabeni lived in an unstable home environment. He explained how a few years ago he lived in a house with 21 people with his mother's family to attend a better school closer to Pietermaritzburg, but then eventually moved back here to this lower quality school because living conditions were better. He now lived with a brother and a cousin on the money his mother made as a domestic worker. In this region of South Africa, domestic workers typically made R100 (approximately $10 at the time) a day. Not only had Shabeni's father passed away, but so had his uncle who had been a strong parental figure in his life. Following his death, Shabeni became a Christian in 2010 and has been trying to find stability and hope in life through faith. He frequently spoke of that year as a turning point in his life, and how he now envisioned himself opening a small grocery store in the area to improve his quality of life.

Consequently, these powerful stories from English class about enduring hard situations and 'getting out there' spoke precisely to Shabeni's hopes and dreams. Like the prisoner who wore glasses, Shabeni saw himself as a good believer who will one day have a better life. Because exercises such as the discussion of Shantytown spoke to Shabeni's life experiences, he reworked this literature into ideas of how he should live today and in the future. His fluid transition between the use of 'you' and 'I' highlights how he interpreted his classes as instructing him on how to live as a moral being. By selecting literature that elicited emotional responses, Shabeni's teacher encouraged young people to translate coursework into moral lessons regarding how they ought to live. In the case above, Shabeni learned that he should 'have hope', 'never give up', and remain a 'good believer'.

Naidoo (21f) was a student at Siyabonga High School. She similarly articulated how an English exercise taught her values because it spoke to her life circumstances. Naidoo explained that she learned about non-racism, equality and reconciliation through a short story students read in class called 1949, by Ronnie Govender. This short story recounted the violence that broke out among Zulu and Indian populations in Durban, and one Zulu man's unsuccessful attempts to protect his Indian neighbours from the violence. She explained that although Ndumi, the Zulu man, 'was asking for peace' from the mob, in the end both he and the Indian family were killed.

Naidoo, who spoke softly and rarely throughout focus groups, talked extensively about this story because it connected with some of her life experiences. This young woman named herself 'Naidoo', a very common Indian South African surname, after her mother's former employer. Her mother worked as a domestic worker for a family with this surname, and the wife regularly made delicious Indian food for Naidoo's mother to bring to her Zulu family. Naidoo admired and cared for this Indian woman, despite living in a context where animosity continues to thrive between Indian and black South Africans. Thus, this story about interracial friendship spoke to her the most and she drew connections between this story and the moral values that it taught. Her teacher regularly selected emotionally-charged stories about South Africa's past, which led students to think about how to live as moral beings. These examples are just two among many wherein students reflected on their favourite English stories and History lessons and connected them to their own lives and how they ought to live.

While many students translated their English and History studies into ideas of how they should live as moral individuals, other students reworked their History lessons into a form of collective morality that highlighted generational separation. For instance, Mr Shabalala's exercises that encouraged debate on South Africa's social and economic history were regularly brought up by his learners in our focus groups. When students recalled their History lessons they articulated how older people have the 'apartheid mindset', which the younger generation does not have. They talked about how older people 'discriminate' and reflected on some personal experiences of this discrimination. For instance, Boxer (19m) explained, 'When you go somewhere, maybe in the mall or doing something else, you find an old person, maybe it's an Afrikaner or a white person say, "Eish, wow look that black person do that". You know when they have their own conversation the elders you will see there is still a lot to do'. Yet, like Mr Shabalala, students focused on how this discrimination was a remnant of the past. The 'modern' generation, or the 'ama-born frees', who were born after apartheid, did not do this. Students further reflected on how their History class taught them that they must not 'do the same thing that older people did' (Hero 18m), such as using derogatory racial terms. Thus, Mr Shabalala's emphasis on using education to help people of different races be able to communicate and be united here seems to work; however, in the process it has generated a moral divide between older and younger generations.

INDIVIDUALISED MORALITY VERSUS COLLECTIVE ACTION

By reflecting on short stories and poems, and debating the justness of historical events, the youth engaged in the process of moral translation - they reworked their class lessons into how they ought to believe and act in moral ways. The problem-posing methodology that Mr Shabalala adopted through the use of debate, as well as the more common use of teaching emotionally-charged literature, resonated well with students and encouraged them to think about how contemporary society came into existence. In this regard, it appears as though South African schools - even the underprivileged former black schools - may be addressing curricular designs to promote social justice and positive social change. However, the youth do not always engage in the process of critical reflection to inspire action, which is a goal of Freirean critical pedagogy.

While the youth embrace stories that discuss poverty and violence because these stories connect to their own experiences, they are rarely critical of the power structures that form their environment. The forms of moral behaviour the youth learn would entail friendship, respect, personal responsibility, and hoping for a better future. These are ideas rooted in individual action that remain detached from addressing social and economic inequalities and insecurity that many youth experience on a daily basis. When the youth reflected on collective morality they did so through the lens of themselves as the younger generation, rather than by reflecting on contemporary social, economic, gendered and racial inequalities and ways of improving these circumstances.

The fact that many students articulated how their lessons encouraged individual moral action is unsurprising as many teachers highlighted their role to encourage moral individual behaviours, rather than inspire the youth to act collectively to change their environments. While some teachers recognised the potential and challenges of education to further social justice, teachers did not have a clear idea of how they -as professionals - could translate their work of fostering critical reflection into action that would encourage social justice. Even teachers like Mrs Magwaza who, through narrative instruction, told students to change the economic structures of South Africa, were unable to encourage critical reflection on how this could be accomplished.

Teachers' ambiguity in identifying their ability to act as agents of change reveals some limitations of the Freirean framework. Teachers in these low-income schools at times feel crippled by their teaching environments; they are acutely aware of the fact that national curricular policies that claim to promote social justice exist in a context of severe educational inequalities. Their demands on the government to develop schools that are safe, offer equal resources and charge equal fees to further justice should not be taken lightly. Yet, in order to develop citizens who can make demands on the government through democratic practices, the educators must develop a clearer conception of the possibilities of action they can take to create a more equitable and socially just society. I suggest that teacher training programmes offer a more global perspective to highlight successful initiatives around the world to inspire critical reflection and action. Practices and initiatives from resource-poor and post-conflict societies (Apple 2010; Lazar 2010; Murphy-Graham 2012) could inspire teachers to recognise their potential roles as educators to foster social change. By learning from cross-cultural studies, teachers may identify the ways in which they can motivate the next generation of citizens to demand and create a better world. Moreover, cross-cultural studies could allow for greater reflection on gendered inequities that not only remained unexamined by teachers in this case study, but were reinforced through narrative instruction. This special issue, and this study in particular, offer an initial step in this direction. By initiating dialogue from contexts in the Global South, educators and policymakers can learn of the challenges and potential of educators to help foster positive change.

Second, while some teachers effectively encouraged critical reflection on contemporary social challenges primarily through selecting course material that elicited emotional responses, this pedagogical practice fell secondary to narrative instruction. Most teachers told students what to learn, think and remember, rather than allowing for ground-up reflection. Furthermore, as a methodological note, it was unclear if students would have reflected critically on many of their class exercises had it not been for our focus groups. By asking students to reflect on their classes in intimate group settings, this research study may have contributed to the youths' reflection and processes of moral translation. This highlights both the limitations of South African over-crowded classrooms to encourage critical reflection, as well the promise that smaller group discussion may result in pressing questions of social justice. To encourage reflection teachers should continue to select materials that will speak to students' life experiences, while also employing pedagogical practices that value student input and debate.

Finally, lessons need to go further to allow students to collectively brainstorm 'what can be done' to change the inequalities, insecurities, and violence that they - and many South Africans - experience on a daily basis. Rather than simply encourage students not to engage in violence or revenge, to get along with others, and to hope for a better future, teachers should inspire consideration into tangible methods for creating a better world. A potential arena of improvement lies in political education. Classes that addressed topics of democracy and governmental structures only focused on the memorisation of terms, rather than actions that the youth can take to address structural changes. Drawing on Freirean critical pedagogy can help address collective action to address structural inequalities. Problem-posing questions that trace recent events that have happened in these school communities could encourage collective action. For instance, at Ikwezi teachers worked with the community to make the government build a bridge over the river next to the school. Asking students how they could receive support for other works of infrastructure, job creation, or educational support could open awareness of how citizens can make demands through democratic structures. By offering students more of a voice and valuing their knowledge and agency, teachers can help moderate discussion on the ways in which the next generation of South African citizens may contribute to social change.

REFERENCES

Apple, M.W., ed. 2010. Global crises, social justice, and education. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Balwanz, D. and M. Hlatshwayo. 2015. Re-imagining post-schooling in Sedibeng: Community-based research and critical dialogue for social change. Education as Change 19(2): 133-150. doi: 10.1080/16823206.2015.1085615. [ Links ]

Bantwini, B.D. 2010. How teachers perceive the new curriculum reform: Lessons from a school district in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development 30(1): 83-90. [ Links ]

Bartlett, L. 2005. Dialogue, knowledge, and teacher-student relations: Freirean pedagogy in theory and practice. Comparative Education Review 49(3): 344-364. [ Links ]

Beldo, L. 2014. The unconditional 'ought': A theoretical model for the anthropology of morality. Anthropological Theory 14(3): 263-279. [ Links ]

Bhana, D. and S.J. Mcambi. 2013. When schoolgirls become mothers: Reflections from a selected group of teenage girls in Durban. Perspectives in Education 31(1): 11-19. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. and J.C. Passeron. 1977. Reproduction in education, society and culture. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Bowles, S. and H. Gintis. 1976. Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Bush, K.D. and D. Saltarelli, eds. 2000. The two faces of education in ethnic conflict: Towards a peacebuilding education for children. Florence: United Nation's Children's Fund, Innocenti Research Centre. [ Links ]

Coben, D. 1998. Radical heroes: Gramsci, Freire and the politics of adult education. New York: Garland. [ Links ]

Cole, E.A. and K. Murphy. 2010. History education reform, transnational justice, and the transformation of identities. In Identities in transition: Challenges for transnational justice in divided societies. Edited by A. Paige, 334-367. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Davids, N. and Y. Waghid. 2016. Responding to violence in post-apartheid schools: On school- leadership as mutual engagement. Education as Change 20(1): 28-42. [ Links ]

Davis, D. and M. Steyn. 2012. Teaching social justice: Reframing some common pedagogical assumptions. Perspectives in Education 30(4): 29-38. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2011. Curriculum and assessment policy statement Grades 10-12: History. Retrieved from: http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/CD/NationalCurriculumStatementsandVocational/CAPS FET HISTORY GR 10-12 WeB.pdf?ver=2015-01-27-154219-397 (accessed 15 June 2016).

Department of Education (DoE). 2001. Manifesto on values, education, and democracy. Retrieved from: http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/Act84of1996.pdf (accessed 26 June 2016).

Dewey, J. 1916. Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Dryden-Peterson, S. and R. Sieborger. 2006. Teachers as memory makers: Testimony in the making of a new history in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development 26(4): 394-403. [ Links ]

Engelbrecht, A. 2006. Textbooks in South Africa from apartheid to post-apartheid: Ideological change revealed by racial stereotyping. In Promoting social cohesion through education: Case studies and tools for using textbooks and curricula. Edited by E. Roberts-Schweitzer, V. Greaney and K. Duer, 71-80. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute. [ Links ]

Fiske, E. and H. Ladd. 2004. Elusive equity: Education reform in post-apartheid South Africa. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Press. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 1991 [1977]. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Frank, F., L. Sikhakhane, R. Subramony, C.-A. Stephenson, T. Mbansini and R. Pillay. 2012. New generation history: Grade 11 learner's book. Durban: New Generation Publishers. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 1997 [1970]. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: The Continuum Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Giroux, H.A. 2005. Schooling and the struggle for public life: Democracy's promise and education's challenge. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers. [ Links ]

Greaney, V. 2006. Textbooks, respect for diversity, and social cohesion. In Promoting social cohesion through education: Case studies and tools for using textbooks and curricula. Edited by E. Roberts-Schweitzer, V. Greaney and K. Duer, 47-69. Washington, DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

Hammett, D. and L.A. Staeheli. 2013. Transition and the education of the new South African citizen. Comparative Education Review 57(2): 309-331. [ Links ]

Hammett, D. and L.A. Staeheli. 2011. Respect and responsibility: Teaching citizenship in South African high schools. International Journal of Educational Development 31(3): 269-276. [ Links ]

Hemson, C. 2006. Teacher education and the challenge of diversity in South Africa. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Horner, L., L. Kadiwal, Y. Sayed, A. Barrett, N. Durrani and M. Novelli. 2015. Literature review: The role of teachers in peacebuilding. University of Sussex: UNICEF.

Hunt, F. 2011. Schooling citizens: Policy in practice in South Africa. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 41(1): 43-58. [ Links ]

Jackson, S.M. 1997. Critical pedagogy and the public sphere: Comparative perspectives in education in South Africa and the United States. Social Dynamics 23(2): 19-56. [ Links ]

Lazar, S. 2010. Schooling and critical citizenship: Pedagogies of political agency in El Alto, Bolivia. Anthropology and Education Quarterly 41(2): 181-205. [ Links ]

Motala, S. 2008. The impact of finance equity reforms in post-apartheid schooling. In Educational change in South Africa: Reflections on local realities, practices, and reforms. Edited by E. Weber, 301-18. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Murphy-Graham, E. 2012. Opening minds, improving lives: Education and women's empowerment in Honduras. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. [ Links ]

Naidoo, L.-A. 2015. The role of radical pedagogy in the South African Students Organisation and the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa, 1968-1973. Education as Change 19(2): 112-132. [ Links ]

Parker, W.C. 2006. Public discourses in schools: Purposes, problems, possibilities. Educational Researcher 35(8): 11-18. [ Links ]

Pillay, A. 2014. Using collaborative strategies to implement critical pedagogy in an HE lecture-room: Initiating the debate. South African Journal of Higher Education 28(1): 1-9. [ Links ]

Postma, D., C.A. Spreen and S. Vally. 2015. Education for social change and critical praxis in South Africa. Education as Change 19(2): 1-8. [ Links ]

Priestley, M., G. Biesta and S. Robinson. 2013. Teachers as agents of change: Teacher agency and emerging models of curriculum. In Reinventing the curriculum: New trends in curriculum policy and practice. Edited by M. Priestley and G. Biesta, 187-206. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [ Links ]

Sayed, Y. and S. Motala. 2012. Equity and 'no fee' schools in South Africa: Challenges and prospects. Social Policy and Administration 46(6): 672-687. [ Links ]

Sayed, Y. and M. Novelli. 2016. The role of teachers in peacebuilding and social cohesion: Synthesis report on findings from Myanmar, Pakistan, South Africa and Uganda. University of Sussex: Research Consortium Education and Peacebuilding.

Singh, L. and D. Francis. 2010. Exploring responses to xenophobia: Using workshopping as critical pedagogy. South African Journal of Higher Education 24(3): 302-316. [ Links ]

Thomas, D.P. 2009. Revisiting pedagogy of the oppressed: Paulo Freire and contemporary African studies. Review of African Political Economy 36(120): 253-269. [ Links ]

Willis, P.E. 1981 [1977]. Learning to labor: How working class kids get working class jobs. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

1 All school, staff and student names used in this study are pseudonyms. Students selected their own pseudonyms. This research received ethical approval from an Internal Review Board, as well as from the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education.