Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 n.3 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/1361

ARTICLES

Teacher governance factors and social cohesion: insights from Pakistan

Anjum HalaiI; Naureen DurraniII

IAga Khan University Email: anjum.halai@aku.edu

IIUniversity of Sussex Email: n.durrani@sussex.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

This paper explores teacher governance factors, particularly recruitment and deployment of teachers, in relation to inequalities and social cohesion. Pakistan introduced major reforms in education in the post 9/11 context of escalating conflict. These include a merit and needs-based policy on teacher recruitment to eliminate corruption in recruitment and improve equity on the basis of gender, language, ethnicity, religion, and special needs. A 4Rs framework of redistribution, recognition, representation and reconciliation was employed to analyse data gathered from: interviews with teacher educators, policy makers and development partners, and focus group discussions with and questionnaires completed by pre- and in-service teachers. The study concluded that teacher recruitment was driven by concerns of quality with weakly implemented largely quantitative measures of inclusion. Socio-politically grounded measures would be required for a diverse teaching force. Alongside, policies and procedures for the transfer of teachers would need to be streamlined so that teachers deployed to schools in marginalised areas serve there for a specified period of time.

Keywords: teacher recruitment; teacher deployment; social cohesion; conflict

INTRODUCTION

The global education policy agenda recognises the centrality of teachers to achieving all the goals listed on the Education 2030 agenda, but acknowledges that a shortage and an unequal distribution of professionally qualified teachers exacerbate equity gaps in education (UNESCO 2015). Furthermore, it views adequately recruited and remunerated, motivated and professionally qualified teachers a pre-condition to the provision of quality education and calls upon governments to deploy teachers where they are needed most. However, in contexts affected by conflict and tension between different social groups, quality education must play a role in social cohesion through strategies such as building trust in schools and between social groups, respect for diversity and the inclusion of those marginalised from participation in the profession (e.g. women, religious/ethnic minorities). The recruitment and deployment of teachers in such contexts would have to ensure that there is variety and diversity in the teaching force and that qualified teachers are redistributed to schools in remote rural communities or areas affected by conflict.

Research reported in this paper examined how teacher governance supported education for social cohesion and peacebuilding in the conflict-affected setting of Pakistan. It was guided by the question: How do interventions in teacher recruitment and deployment attempt to ensure that teachers, including those marginalised on the basis of gender, special needs, ethnicity and religion, are recruited and deployed to remote, rural and conflict-affected contexts? The paper draws from a larger project that looked at the role of education and social cohesion to inform policy and practice within three areas: the integration of social cohesion into education policy, the role of teachers in fostering social cohesion and youth agency for social cohesion and transformation.

The following section looks at the drivers of conflict in the socio-political context of Pakistan. A brief overview of the education system in the country follows. The next section locates the study within current literature on teacher governance and provides a description of the analytic framework employed. After a description of the study, the presentation of results follows. The final section offers conclusions and makes recommendations for policy and practice.

SOCIO-POLITICAL CONTEXT AND CONFLICT DRIVERS IN PAKISTAN

Pakistan currently ranks 14th on the global ranking of fragile states1 with factors including religion, ethnicity, gender and poverty contributing to inequalities and a fragile social fabric within the country (Durrani et al. 2017).

An overwhelming majority (96%) of Pakistan's population is Muslim. The country's small religious minority citizens (4%) include Christians (largest group), Hindus (mostly settled in the border districts of Sindh) and the Ahmadi community who consider themselves Muslims but were declared non-Muslims by the state in 1974 (Government of Pakistan 1998). In 1979, the Zia regime introduced the process of Islamisation from a very narrow perspective thereby undermining the vision of Pakistan as a Muslim majority state, with equal rights and opportunities for religious minorities. This period politicised Islam to gain ideological consensus, and engendered a politics on the basis of gender, ethnic and religious difference (Durrani 2008).

Besides the ideological cleavages resulting from the politicisation of Islam, marginalisation on the basis of ethnic and linguistic grouping also fuelled conflict. Pakistan is ethnically and linguistically plural comprising five major ethnic groups, with language considered an important marker of ethnicity. According to the 1998 census, Punjabis constitute 55%, Pakhtuns 15%, Sindhis 14%, Mohajirs28% (these speak Urdu natively, the national language in Pakistan), Balochs 4% and others 4% (Government of Pakistan 1998). Punjab is arguably the most developed province while Sindh and Balochistan include some of the most poverty stricken regions in the country. With 53% of Pakistan's population concentrated in Punjab, a high representation of the Punjabi ethnic group in Pakistan military, civil bureaucracy and political structures, Punjab dominates the social, economic and political landscape in Pakistan. This has caused resentment among the smaller provinces and ethnic minorities (Cohen 2005).

Gender inequity is a significant issue in a society where religious thought and practice is used as a mechanism for the construction of gender, particularly the 'proper' Muslim woman (Durrani 2008). Although the Constitution of Pakistan grants equal rights to men and women, profound gender inequalities exist with respect to human development and access to services, economic opportunities, political participation and decision-making.

In addition to the divisions in the social groups as described above, Pakistan has been affected by conflict and violence due to armed-conflict and enduring rivalry with its neighbour India and the on going US-led 'War on Terror' in Afghanistan since the events of 9/11.

EDUCATION IN PAKISTAN - A BRIEF OVERVIEW

In Pakistan, education is recognised as a significant investment in human development. Article 25-A in the constitution notes that 'TheState shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of five to sixteen years in such manner as may be determined by law' (NEMIS-AEPAM 2015, 3). Pakistan is a signatory to global policies on universal primary education such as Education for All.3 A combined effect of the global and national policies on the universalisation of primary education and a massive population growth has seen a rapid expansion of the school education system in the country.

The government school system, comprising primary, middle, high or secondary schools, is the main provider of school education. Nonetheless, the share of the private sector is rapidly increasing. Pakistan takes explicit account of gender in provision of schooling, with schools for girls with female teachers and boys' schools with male teachers. Gender is a key marker of marginalisation with respect to educational access, participation and outcomes. The gender gaps with respect to education are related to both demand and supply issues. From the demand side, empirical evidence suggests a promale bias in parental decisions to enrol and how much to spend on children's education (Aslam & Kingdon 2008). On the supply-side, the number of schools and teachers are two important policy measures to reduce gender disparities. While overall the number of female teachers is higher (57%) there is variation across the public and the private sector. In the public sector, at all levels of schooling there are far more male teachers as compared to female teachers (Durrani et al. 2017). There is regional variation too. Punjab, Sindh and Islamabad, the capital city, have a higher proportion of females. The regions with lower proportion of female teachers - FATA (28%), Balochistan (37%) and KP (42%) - are also the ones with wide gender gaps in educational participation rates (NEMIS-AEPAM 2015).

Sindh, where the study was conducted, also had huge gender disparities within the system. 'The majority of teachers in primary and middle schools are male...girls: schools account for only 16% schools in the province. Although there are also a large number of mixed schools, the average ratio of girls in girls-only schools is 75% as compared to 25% in mixed schools and 14 per cent in boys' schools' (GoS 2014a, 109). Elsewhere, Ali (2011, 46) maintains that in Sindh 'at middle school level in rural areas the male teachers are almost 3.5 times more than female teachers, while in urban areas the number of female teachers is almost double [the number of] male teachers'.

This demonstrates the importance of establishing separate facilities for girls and recruiting female teachers in redistributing access for girls, as 53% of girls aged 5-16 are currently out of school (Alif Ailaan 2014).

Teacher education

The rapid expansion of the school system intensified the need for qualified teachers. An overview of education policies since 1947 reflects a tension in the increasing demand for teachers and the quality of teacher preparation so that the implementation of all measures of quality remained weak (Durrani et al. 2017). In recognition of the weak teacher education provision, reforms were introduced including a two-year Associate Degree leading to a four-year B.Ed. (Hons), enhanced entry qualification and an increase in teachers' salaries (HEC 2010).

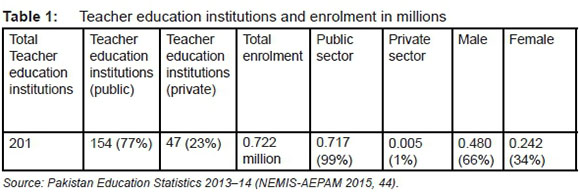

The provision of teacher education has been the purview of provincial governments with oversight from the federal ministry. Provinces have a fairly centralised organisational structure with a network of colleges of education and university-based departments of education to prepare teachers for schools (MoE 2009a). Table 1 shows the number of teacher education institutions and enrolments.

The information above shows 23% private institutions with only 1% of the enrolment and 99% enrolment in the public sector. An implication of this imbalance in distribution would be over-crowded public sector institutions. However, the situation on the ground was confusing because the public sector institutions were also under-enrolled. Coleman (2010, 32) holds that 'Many of these (teacher education) institutions have very small numbers of students, as few as 130 or even 75. One explanation for this is apparently that people wishing to obtain a B.Ed. certificate which qualifies them to teach can obtain one - for a fee - from a "mushroom institution"'. Participants in this study confirmed that enrolment was very low in teacher colleges and partly put it to the private institutions where according to them enrolment rules were lax and partly to the misperceptions about the status of the two-year Associate Degree in Education (ADE).

Private sector can do whatever they feel right, all rules and regulations are for Public sector... The students say that, 'instead of doing ADE why don't we do graduation'? Although ADE is equal to graduation, people don't understand that.

A systematic profiling and analysis of enrolment data in teacher education institutions would be essential to understand issues of access and distribution.

Beyond access the prevailing National Education Policy 2009 notes several policy actions for issues of quality and equity through redistribution measures in teacher recruitment and deployment:

• Government shall take steps to ensure that teacher recruitment, professional development, promotions and postings are based on merit alone.

• Teacher allocation plans, likewise, shall be based on school needs and qualifications of teachers. Over the next two years, Governments shall develop a rationalised and need-based school allocation of teachers, which should be reviewed and modified annually.

• Incentives shall be given to teachers in rural or other hard areas, at least to compensate for loss in salary through reduction of various allowances given for urban but not for rural postings.

• Maximum age limit shall be waived off for recruitment of female teachers. (MoE 2009b, 43)

The rules of recruitment at the provincial level included statutory clauses to support the inclusion of women, minorities and handicapped applicants: a) For female applicants a 3-year special age relaxation in the maximum age of recruitment; b) A 2% statutory quota of the total allocated posts in each category is to be reserved for disabled persons in each district; c) 5% of the total number of advertised posts in each category of educators are to be fixed for minorities (non-Muslims) (GoB 2014; GoP 2014; GoKP 2014; GoS 2012). The policy recommendations and related rules are aimed at distributive justice through enabling a better representation of teachers from marginalised social groups. Issues arising in teacher recruitment and deployment as a result of these policy provisions are discussed in the sections on results.

TEACHER RECRUITMENT AND DEPLOYMENT: EQUITY AND QUALITY DILEMMAS

The recruitment and deployment of teachers is not simply a matter of teacher quality; it is also a concern of social justice in education provision, particularly the equitable distribution of teachers. Ironically, schools where teachers are most needed are often the ones that teachers actively avoid, such as schools in remote, rural, poor, conflictand violence-affected, and ethnic minority areas (UNESCO 2014). Across the Global South, the adequate deployment of teachers, particularly female teachers, in remote and rural schools is a challenge (Horner et al. 2015). A shortage in teacher supply or uneven deployment result in high pupil to teacher ratios (PTR) with consequences for the quality of pupils' participation (Cooper & Alvarado 2006). Additionally, it hugely impacts on teachers' working conditions, and adds to their workload, often requiring them to teach simultaneously two or more grades. For example, a greater prevalence of multigrade teaching in rural public schools in Pakistan (43% primary; 10% middle) compared to urban areas (14% primary; 5% middle) has been reported (ITA 2015).

Diversity in the teaching cadre reflecting a mix of gender, linguistic, ethnic, religious or other diversity in society contributes beneficially to the education of all students (Howard 2010). Teachers with the same gender as the pupils are associated with higher student learning outcomes (Muralidharan 2012). In the case of highly gender-segregated societies like Pakistan, female teachers increase the chance of girls' participation in schooling (Aslam & Kingdon 2011). Similarly, in multilingual societies where pupils come from different home language backgrounds teachers' language backgrounds are a significant factor in deployment (Pinnock 2009). An in-depth review on teachers and social cohesion maintains that the 'role of a representative teaching body in recognizing diversity is particularly important in post-conflict contexts where inequality in educational representation, access and outcomes is a potential catalyst for conflict' (Horner et al. 2015, 45).

To ensure diversity in representation in teacher recruitment and deployment, several strategies are employed by policy makers. An incentive in the form of 'hardship allowance' is a well-known strategy to recruit teachers, especially women from remote rural communities. For example, in Gambia a policy to attract qualified teachers to schools in rural areas provided a salary premium, known as a hardship allowance, to primary school teachers who work in the poorest and most remotely located regions of the country. Findings suggest that while the hardship allowance was successful in recruiting qualified teachers to rural areas, in the most remotely located schools its impact was rather limited (Pugatch & Schroeder 2014). Furthermore, there was no evidence that the allowance succeeded in raising the share of female teachers in remote schools. The study goes on to recommend that rather than 'spreading existing qualified teachers more evenly' greater gains can be made 'if the policy succeeds in attracting more qualified teachers to the system' (ibid, 22). Similarly, cash or salary incentives are also offered to attract teachers in specific subject areas such as Science and Mathematics or to schools in difficult locations (Cooper & Alvarado 2006; Loeb & Myung 2010). Non-monetary incentives include offering teachers working in marginalised areas the opportunity to advance more rapidly through the promotion system compared to teachers in wealthier areas (Luschei & Chudgar 2015).

The strategy of allocating reserved quotas is employed to redress the imbalance in access to education and opportunity. For example, in India quotas are reserved for the Dalit community to enter higher education (Ovichegan 2015). However, Ovichegan (ibid) insightfully concludes that while quotas do increase the Dalit students' access to opportunity they do not address deep-rooted issues of social justice related to identity, social class, gender and caste. Furthermore, Amutabi (2003, 135) maintains that quotas are contentious in Kenya's education system and have 'promoted regionalism as it encourages localized approaches to problems'.

To conclude, a teaching force that reflects the diversity in the community would require that enrolments in teacher education programmes also reflect the composition of the wider community. This presents educational policy-makers a challenge especially in resolving the tensions in quality and equity through redistributive and other measures.

The 4Rs framework

The discussion so far suggests that teacher recruitment does not simply concern selecting the best-qualified human resource on the basis of an esoteric criteria; recruitment and deployment to promote social cohesion and peace must take into account social justice issues within the broader socio-political context. Social cohesion refers to 'the quality of coexistence between the multiple groups that operate within a society...along the dimensions of mutual respect and trust, shared values and social participation, life satisfaction and happiness as well as structural equity and social justice' (UNICEF n.d.). From this perspective, social cohesion is a strong element of peacebuilding because it can help avoid conflict through building an inclusive and just society

The role of education in peacebuilding could be understood through Fraser's framework of the three dimensions of social justice, i.e. redistribution, which aims at addressing inequalities (largely economic) through opening access to opportunity and resources; recognition, which entails respecting difference and diversity in the social systems; and representation, which aims to encourage participation (Fraser 2001).

Redistribution is not just concerned with increased access to resources and opportunities for economic progress but is integrally linked to the recognition and representation of groups marginalised in society for example on the basis of language, religion, gender or other forms of exclusion. These are inherently political processes that entail the questioning of hierarchies and assumptions in the social structure that contribute to exclusion and division in society. Usually this framework is employed by policy-makers to support large-scale redistribution of benefits of education across the socioeconomic divide.

Novelli, Lopez Cardozo and Smith (2015, 10) build on Fraser (2001) and argue, 'For conflict-affected and post-conflict contexts, there is a need for processes of reconciliation, so that historic and present tensions, grievances and injustices are dealt with to build a more sustainable peaceful society'. Reconciliation or dealing with injustices in education would include a representative teaching body, ensuring that there are a representative number of positive role models for girls, boys, children with disabilities and from groups historically excluded for socio-cultural and political reasons (Horner et al. 2015). Novelli, Lopez Cardozo and Smith (2015) claim that the 4Rs framework of redistribution, recognition, representation and reconciliation allows for an exploration of the transformations necessary for sustainable peace in conflict-affected societies and the role of education within it. This paper employs the 4Rs analytical framework while recognising that in practice the four analytic categories interconnect and overlap.

THE STUDY

The study was carried out in Sindh, the second most populous province. With 91% of its estimated 42.4 million population being Muslim, Sindh has the highest proportion of religious-minorities in Pakistan (GoS 2014a). It includes areas with sharp socioeconomic disparities and with inequities in education provision and outcomes. Moreover, the ethnic and language mix is also an issue for social cohesion because around 60% of the population living in Sindh is Sindhi, followed by 21% Urdu-language speakers.

In rural areas, the vast majority of the population (over 92 %) is Sindhi, whereas in urban areas the ethnic makeup is far more diverse: Urdu-language speakers represent the largest demographic group in urban areas at 41.5%, compared to only 25% Sindhi speakers (GoS 2014a). Karachi, the capital city of Sindh, reflects key conflict-drivers in terms of ethnic, political and sectarian violence and both Karachi and interior Sindh exhibit structural violence.

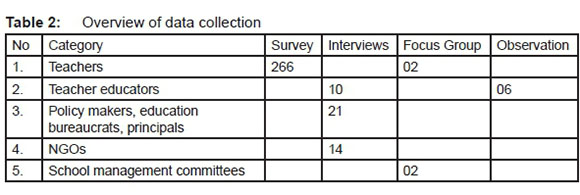

Data collection included multiple methods as shown in the overview table below.

The survey was completed by 266 respondents, of whom 35% were pre- and 65% were in-service teachers, 48% were males and 52% females and 98% were Muslim while 2% were non-Muslim. The survey comprised structured and open questions on issues of social cohesion and the role of (teacher) education, gender and urban-rural equity in education, language issues, and peace. This paper draws on the sections of the survey related to issues of equity (gender and urban-rural divide), social cohesion and peace. Interviews with stakeholders as listed in Table 2 were also part of the data informing this paper.

RESULTS

Merit and needs-based recruitment: Issues for equity

Teacher recruitment and deployment in Pakistan has been plagued with nepotism and interference from the politically and socially powerful with vested interests lobbying for their candidates to be selected and deployed in a region or school of their preference (Bari et al. 2013). Consequently, there was lack of transparency in recruitment and inadequately prepared teachers were recruited. Senior officials in the Education and Literacy Department of the Government of Sindh (ELD-GoS) shared similar concerns about the recruitment process:

Our recruitment system is also faulty; if a teacher is appointed in proper way then he/she will deliver better, but if a teacher is appointed on source4 then they will not perform well, they will come to school only to kill the time.

Teacher must be appointed on merit, they should have the ability and capability as a teacher. Political influence should not be taken into account so that they (teachers) sit at home and take salaries, this should not happen.

To address these issues, a 'Merit and Needs Based' procedure for recruitment was introduced in Sindh that includes the following steps: a), To identify and meet the local needs the district recruitment committees would drive the process in consultation with the provincial authorities in the ELD-GoS; b) Besides other criteria, applicants would have to pass a test administered by an external company, the National Testing System (NTS); c) The final merit list of successful candidates would be approved by the Education and Literacy Department in consultation with the World Bank (a partner in this reform). For transparency, the final merit list would be publicly displayed and then taken forward by the district recruitment committees for onwards processing (GoS 2012 8-10).

The impact of the above transparency measures in a context where meritocracy was routinely violated and political corruption was rife was understandably welcomed by teachers:

...people don't get jobs on merit basis, I think we are the lucky ones who got it on merit basis, otherwise you can get the job by paying some amount, the seats (posts) are sold.

Likewise, a policy-maker responsible for the regulation of private education institutions indicated that experienced and competent teachers from elite private schools had been recruited into the public sector due to enhanced transparency mechanisms and increases in teachers' salaries. While this would add to the pool of quality teachers, given the socio-economic background and urban location of these teachers, the entry of these teachers into the workforce was unlikely to have any significant positive impact on the redistribution of quality teachers in remote and disadvantaged communities.

With the emphasis on 'merit based recruitment', the special quotas - 5% for religious minorities and 2% for disabled persons - in GoS (2012) were no longer mentioned in the recruitment rules (GoS 2014b), raising doubts about the status of these special quotas in the recruitment process. Senior representatives of the ELD-GoS emphasised merit as follows:

When recruitment is done, it is done purely on merit.. .initially there was policy of 1% quota for special persons, now that quota is 2%. And in the recent past some minorities were also demanding their quota. Until and unless quota is included in the recruitment rules that thing (rules of recruitment) remains the same (for all).

They (religious minority) come on merit basis. There is no need of quota because they already come on merit basis... The main thing is that the teacher recruitment is done on merit, whoever comes will come on merit; we have stopped using quota.

There is no specification for Muslims or non-Muslims, if they qualify whether they are Hindu, Christian, Mohajir or Sindhi, they will be recruited. This criterion is given by the World Bank, and the government is bound by it. If they don't follow this rule then they will not get the funds.

If we see the recent appointments of teachers, these people are appointed by the Education Department... the NTS was asked to conduct the test, it is independent, as per the test result many qualified, highly qualified people have entered the teaching profession.

The above confirms that recruitment emphasised merit largely seen in terms of performance in the NTS that could be understood on the basis of historical concerns about teachers' inadequate subject knowledge and the impact of this on students' learning (Iqbal 2007). The second quote states that the minorities do not need 'quotas' because they already make it on merit. This claim was difficult to establish because existing data (e.g. NEMIS AEPAM 2015) do not provide information on teachers disaggregated by religion. In the third quote, the reference to the World Bank alludes to the fact that the Bank played a significant role in driving the reform in teacher governance and also raises questions about the extent to which these measures were grounded in the local socio-political context.

Reserved quotas in recruitment, even if they were operational, raise other questions about its effectiveness. For example, Singal's (2015) study on the education of children with disabilities in India and Pakistan found that the participation, progression and completion rates of children with disabilities were extremely low. This would mean that very few among the disabled persons would meet the high entry criteria for teaching as recommended in the policy (MoE 2009b). What additional measures besides the 2% quota would be taken to ensure that the disabled candidates were represented and recognised in the teaching profession remained a question.

Likewise, in the context of an increasingly polarised society divided along the lines of religion, would a quantitative allocation of 5% achieve the desired result of mitigating inequities on the basis of religion? Social cohesion and peacebuilding would require redressing exclusion by taking specific actions for reconciliation that go beyond the allocation of quotas and other direct measures. In education these measures could include curricula, pedagogic processes and teachers' agency to promote social cohesion and address historical injustice (Horner et al. 2015).

Gender equity in teacher recruitment

In response to a question about the experience of gender violence in and around teacher education institutions, an overwhelming majority (94%) denied having any such experience. This may mean that such violence does not take place in Sindh/Pakistan or that people find it difficult to acknowledge and report it. However, female teachers did note the socio-cultural barrier to girls' participation in education and its implications for social harmony:

Girls get married early because of which they cannot get educated; many parents cannot afford the school fee because of all these issues and because of illiteracy people do not live harmoniously in society.

I can work in a manner that leads towards granting permission of education to girls by this society. This is a society that does not allow girls to go for studies.

Teacher educators expressed an understanding of their role in supporting women who had entered the programme:

Girls are treated with care, their parents and siblings come with them [girls] because most of the girls come from other districts, and distance is very long...We want that female students must get good environment in our institution.

Principals, who might be expected to play a role in supporting female recruitment, largely believed that gender parity in access was tantamount to gender equity in the teaching profession.

I think that gender is not an issue, it is just exaggerated. Allah has made man and woman, and He has given a different potential to both of them...When I am sitting here both male and female are equal for me. (Principal [female] Teacher College)

So, the main purpose is education, for that purpose we have separated classes of males and females, which makes them [parents] happy and they enroll their daughters here. I don't like segregation but according to context I have to do it. (Principal [male] Teacher College)

The above shows that the principals viewed gender equity as realised once males and females have access to education, even if they perceive that there is a difference in the potential of males and females.

Beyond access, gender equity is a complex sociological notion, with concomitant understandings of roles and responsibilities defined along the lines of gender. Statistics could mask issues and gaps in the provision of qualified teachers in remote rural or otherwise marginalised areas, especially the availability of female teachers in girls' schools, and particularly in subjects like Physics and Mathematics.

The lack of potential female teachers, especially in Science and Mathematics at the higher levels of education which government schools require, is a policy challenge. Given the very low status of female education in remote rural locations, and the restriction on female mobility in Pakistan, unless rural communities develop a pool of educated women from which to recruit teachers, schools in rural communities will continue to have difficulties with recruiting and retaining female teachers (Halai 2011).

The incentive in the Education Policy 2009 of 'age relaxation' for women was good in so far as there were women applicants who met the merit criteria. It remained unclear how the prevailing recruitment policy and procedures in Sindh took into account the issue of proportionally fewer numbers of educated females available to enter the profession. Strong affirmative action would be required to increase girls' and women's participation in and completion of post-secondary education to increase the pool of potential applicants to the teaching profession. For example, this could include introducing gender sensitive pedagogies and teaching methods grounded in the socio-cultural context (Horner at al 2015).

The above complexities were also reflected in respondents' answers to survey questions related to teacher governance. Only 6% of student-teachers and 4% of teachers within the sample had some teaching experience in a rural context. When asked if they would accept a rural posting, 38% of student-teachers and 47.4% of teachers did not even answer the question. Of those who did, around 64% of student-teachers and 59% of teachers appeared willing to teach in a rural school, suggesting that a substantial proportion would avoid a rural deployment. Across both categories of respondents a greater proportion of male (59% student-teachers and 64% teachers) compared to female respondents (41% student-teachers and 36% teachers) expressed willingness to accept a rural posting.

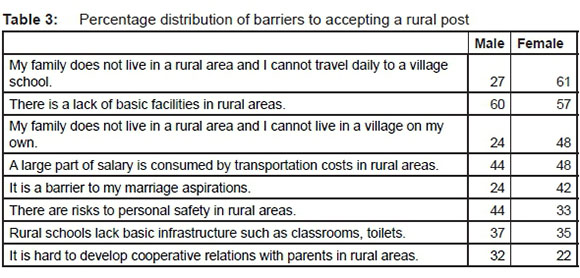

To better understand teachers' attitudes towards a rural posting, respondents were asked to select from a range of statements related to obstacles to accepting a rural post. The eight frequently selected barriers were the same for male and female respondents, but variation in frequency existed on the basis of gender (see Table 3).

Incentives recommended by the respondents for mitigating the above barriers included the provision of transport, accommodation, essential facilities/infrastructure in schools and the community and assurances of safety and security. Some respondents also recommended protection from landlords' interference. In sum, inclusion in terms of the education of women and other marginalised groups would not be meaningful if the process did not reconcile socio-cultural and structural barriers through recognition and representation as envisaged within the 4Rs framework.

Teacher deployment and transfer

An effective system of teacher deployment is important because uneven deployment could lead to issues of social justice such as high PTR, or a lack of teachers in girls' schools especially in remote areas. Senior government officers in ELD-GoS confirmed that teacher deployment was an issue but made contradictory statements about whether or not the teachers' home-district was taken into account:

In far-flung areas, we have the challenge of teachers' appointment, especially in case of female teachers. If we get a local teacher, that is our good luck but it's not necessary.When we advertise in the newspapers, and the committee selects, it does not see whether a person belongs to that area or not. Also it is not binding on the Department that the person from an area should be posted to that area.

The policy of the Education Department is to accommodate local people...But in case there are no local people, then people from the surrounding districts are posted there... How can a female teacher go and come to the school... in a village, which is located in a very far flung area with no hostel for teachers?

The above suggests that deployment was an issue, especially the deployment of female teachers to far-flung areas. Consequently, as soon as teachers were appointed to a school that was not of their preference, they applied to be transferred to another school. Bari et al. (2013, 108) report, albeit from Punjab, that 'In effect these teachers are absent from the school as they spend their energy and time in negotiating the bureaucratic process of getting their appointment transferred to other more "attractive schools"'. Indeed the Senior Minister for Education in Sindh acknowledged the issue of teachers seeking transfers soon after their appointment:

He asked teachers for making up their mind to serve for three years at the first place of posting and advised them not to indulge in applying any influence for transfer. ('More teachers to be recruited', 2015)

The minister was presumably referring to a policy of teachers not being transferred for at least three years when first appointed to a post. When asked, a senior government officer agreed that steps were being taken to ensure that the procedures for the transfer of teachers were streamlined so that at least for primary school teachers the decisions about transfers could be taken at the level of Union Council (sub-district administrative unit). However, it was not possible to verify these measures because there was no teacher education-specific database to support evidence-based planning initiatives for teacher recruitment, teacher education and teacher deployment. As GoS (2014a, 82) confirms 'the overall lack of data contributes to the existing malpractices within the system (e.g. transfer of teachers based on political grounds instead of data-based or needs-based)'.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

To conclude, several policies and procedures were introduced to ensure transparency, meritocracy and inclusion in teacher recruitment and deployment. However, the emphasis on merit-based recruitment was at the forefront so that efforts towards better representation and recognition of the marginalised appeared to be compromised. It can also be concluded that measures of inclusion through a redistribution of access were largely quantitative (e.g. special quotas) and weakly implemented, if at all. Socio-culturally grounded measures for the reconciliation of historical or prevalent injustices did not appear to be introduced.

The conclusions above raise issues and concerns that are relevant beyond the case of Pakistan and have a wider significance for the global efforts regarding education for peacebuilding. For example, dilemmas are widely noted in quality and equity in recruitment and deployment in a diverse society fraught with 'horizontal inequalities', such as those on the basis of ethnicity, language, religion, gender or special needs. On the one hand, a teaching force representing societal diversity would provide the opportunity of opening spaces for reconciliation of historic injustices and bringing communities together through positive role modelling of the marginalised groups (Horner et al. 2015). Diversity is often achieved through direct measures of inclusion such as reserved quotas and cash incentives to quantitatively increase the participation of those left out. There is convincing evidence that these measures do increase recruitment and retention of teachers, especially in areas of hardship.

On the other hand, direct measures of inclusion of marginalised groups need to recognise and represent these very groups as entities and this is inherently a political process because it could mean emphasising group differences. Measures aimed at increasing minority representation through teacher quotas risk the reification of identities and ignore the 'productive role that members of privileged groups must play to support marginalised groups' (Keddie 2012, 275). Likewise, Stewart (2010, 7) holds that direct approaches such as quotas for the allocation of jobs or the distribution of assets 'risk increasing the salience of identity difference and antagonising those who do not benefit from the policy initiative'. He goes on to propose other approaches, such as general policies that aim to diminish the salience of group boundaries by, for instance, promoting national identity and shared activities across groups.

The deployment of teachers thus poses a dilemma in relation to peacebuilding because measures of inclusion could inadvertently erode diversity and affirm separatist thinking. Within the 4Rs framework, enabling recognition and representation poses a dilemma of essentialising differences. For example, Amutabi (2003) provides convincing evidence that quotas for students diminished diversity in the schools and promoted strong regionalism and tribalism. Through their extensive work on the role of education in peacebuilding, Novelli and Smith (2011) maintain that there is a surge of interest in the transformatory role of education in conflict-affected countries, but there are debates about the role of education in relation to other social sectors beyond education and about the need for interventions of a contextually embedded nature as opposed to the standard outside-in approaches to education reform.

Several recommendations arise for policy-makers in education. First, policy formulations should not be exclusively from a perspective of efficiency but should also take into account issues of social justice in education reform. A lack of attention to social justice issues in education could exacerbate 'horizontal inequalities'. Second, as Novelli Lopez Cardozo and Smith (2015) have noted, education reform is usually seen in technical terms such as improving achievement in literacy and numeracy. However, for education to play a transformative role in peacebuilding and social cohesion, it would be important to locate education reform in the political economy in order to engage with issues of economic, political and social exclusion that lead to conflict in society. Third, as Sayed and Novelli (2016) argue, the tensions between redistribution and recognition with respect to teacher governance demand multi-pronged and contextualised policy interventions. For redistributive justice, a range of policy measures would be needed to mitigate some of the barriers identified by the research participants, including hardship/transport allowance, provision of accommodation in rural areas, assurances of personal safety, as well as improving school facilities and infrastructure. Additionally, participatory approaches to policy formulation - providing a space to teachers on the ground to have a voice in the decision-making process - are necessary for representative justice. Furthermore, ensuring an adequate number of female teachers, disabled teachers, teachers from minority backgrounds and those from remote/disadvantaged areas in the workforce would entail aligning teacher education with the deployment needs of candidates and communities (Horner et al. 2015). Contextualised school-based teacher education has been found particularly effective in ensuring a supply of teachers and promoting teachers' potential to encourage social transformation in marginalised communities in rural Sindh (Jerrard 2016). Finally, given the immense challenges in striking a fine balance between the competing demands of various dimensions of social justice in teacher governance, the monitoring and evaluation of different policy options would be required in order to ground policy in evidence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Research reported in this paper was generously sponsored by UNICEF and ESRC UK. We are deeply grateful to the research participants and team members for their contributions, especially to Salima Karim Rajput for her work in data collection. The views expressed in the paper do not reflect that of the sponsors or their partners.

REFERENCES

Ali, S. 2011. Policy analysis of education in Sindh. Pakistan: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Alif Ailaan. 2014. 25 Million broken promises: The crisis of Pakistan's out-of-school children. Islamabad: Alif Ailaan. [ Links ]

Amutabi, M.N. 2003. Political interference in the running of education in post-independence Kenya: A critical retrospection. International Journal of Educational Development 23(2): 127-144. [ Links ]

Aslam, M. and G. Kingdon. 2008. Gender and household education expenditure in Pakistan. Applied Economics 40(20): 2573-2591. [ Links ]

Aslam, M. and G. Kingdon. 2011. What can teachers do to raise pupil achievement? Economics of Education Review 30(3): 559-574. [ Links ]

Bari, F., R. Raza, M. Aslam, B. Khan and N. Maqsood. 2013. An investigation into teacher recruitment and retention in Punjab. Lahore: Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives. Retrieved from: http://ideaspak.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Teacher-Recruitment-and-Retention_Final.pdf (accessed 16 October 2016). [ Links ]

Cohen, S.P. 2005. The idea of Pakistan. Lahore: Vanguard. [ Links ]

Coleman, H. 2010. Teaching and learning in Pakistan: The role of language in education. Islamabad: The British Council. [ Links ]

Cooper, J.M. and A. Alvarado. 2006. Preparation, recruitment and retention of reachers. Paris: IIEP, UNESCO. Retrieved from: http://www.unesco.org/iiep/PDF/Edpol5.pdf (accessed 2 July 2016). [ Links ]

More teachers to be recruited in Sindh, says minister. The Daily Dawn, 16 April 2015. Retrieved from: http://www.dawn.com/news/1176135/more-teachers-to-be-recruited-in-sindh-says-minister (accessed 11 October 2016).

Durrani, N. 2008. Schooling the 'other': The representation of gender and national identities in Pakistani curriculum texts. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 38(5): 595-610. [ Links ]

Durrani, N., A. Halai, L. Kadiwal, S.K. Rajput, M. Novelli and Y. Sayed. 2017. The role of education in social cohesion: Country report Pakistan. Brighton: University of Sussex. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. 2001. Social justice in the knowledge society. Invited keynote lecture at the conference on the 'Knowledge Society'. Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Berlin.

GoB. 2014. Recruitment policy 2014 for teachers and staff of SED-BPS -5-15. Quetta: Secondary Education Department, Government of Balochistan. [ Links ]

GoKP. 2014. Eligibility, criteria, elementary and secondary education department Peshawar KPK jobs 2014. Peshawar: Government of KP. Retrieved from: http://www.khyberpakhtunwa.gov.pk (accessed 26 October 2016). [ Links ]

GoP. 2014. Recruitment policy 2014 for educators. Lahore: School Education Department Government of Punjab. Retrieved from: http://schoolportal.punjab.gov.pk/pdf/Recruitment%20Policy-2014.pdf (accessed 26 June 2016). [ Links ]

GoS. 2012. Teacher recruitment policy 2012 round Ill-instructions manual for appointments process. Department of Education and Literacy, Government of Sindh. Retrieved from: http://www.sindheducation.gov.pk/Contents/Menu/TRInstructionManualRound-III.pdf (accessed 1 October 2016).

GoS. 2014a. Sindh education sector plan 2014-18. Karachi: Education and Literacy Department, Government of Sindh. Retrieved from: http://www.sindheducation.gov.pk/Contents/Menu/Final%20SESP.pdf (accessed 26 May 2016).

GoS. 2014b. Recruitment rules of various posts 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.sindheducation.gov.pk/Contents/Menu/Rules%202014.pdf (accessed 2 November 2016).

Government of Pakistan. 1998. Percentage population by religion, mother tongue, and disability 1998, Pakistan. Retrieved from: http://www.pap.org.pk/statistics/population.htm#tab1.4 (accessed 26 October 2016).

Halai, A. 2011. Equality or equity: Gender awareness issues in secondary schools in Pakistan. International Journal of Educational Development 3(1): 44-49. [ Links ]

HEC. 2010. Curriculum of education. B.Ed. 4-year Degree Programme (elementary, secondary), Associate Degree in Education, MS/M.Ed. Education-revised 2010. Islamabad: Higher Education Commission. Retrieved from: http://www.hec.gov.pk/InsideHEC/Divisions/AECA/CurriculumRevision/Documents/Education-2010.pdf (accessed 26 October 2016). [ Links ]

Horner, L., L. Kadiwal, Y. Sayed, A. Barrett, N. Durrani and M. Novelli. 2015. Literature review: The role of teachers in peacebuilding. Retrieved from: http://www.ungei.org/resources/files/The-Role-of-Teachers-in-Peacebuilding-Literature-Review-Sept15.pdf (accessed 26 October 2016).

Howard, J. 2010. The value of ethnic diversity in the teaching profession: A New Zealand case study. International Journal of Education 2(1): 1-21. [ Links ]

Iqbal, H.M. 2007. Teachers' content knowledge and pedagogical competence: Issues for teacher status in Pakistan. In Teacher status: A symposium. Edited by A. Halai, 42-65. Retrieved from: http://ecommons.aku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006&context=books (accessed 20 October 2016).

ITA. 2015. Annual status of education report ASER Pakistan 2014. Lahore: South Asian Forum for Education Development Secretariat, ITA. [ Links ]

Jerrard, J. 2016. What does 'quality' look like for post-2015 education provision in low-income countries? An exploration of stakeholders' perspectives of school benefits in village LEAP schools, rural Sindh, Pakistan. International Journal of Educational Development 46(1): 82-93. [ Links ]

Keddie, A. 2012. Schooling and social justice through the lenses of Nancy Fraser. Critical Studies in Education 53(3): 263-279. [ Links ]

Loeb, S. and J. Myung. 2010. Economic approaches to teacher recruitment and retention. In International encyclopaedia of education. Vol. 8. 3rd edition. Edited by B. McGaw, P. Peterson and E. Baker, 473-480. Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Luschei, T.F. and A. Chudgar. 2015. Evolution of policies on teacher deployment to disadvantaged areas. Background paper for EFA Global Monitoring Report 2015.

MoE 2009a. National standards for accreditation of teacher education programmes. Islamabad: National Accreditation Council for Teacher Education. Islamabad: Government of Pakistan. [ Links ]

MoE 2009b. National Education Policy. Islamabad: Government of Pakistan. Retrieved from: http://www.moe.gov.pk/ (accessed 26 October 2016). [ Links ]

Muralidharan, K. 2012. Long-term effects of teacher performance pay: Experimental evidence from India. A research report. India: Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness. Retrieved from: http://www.sree.org (accessed 26 October 2016).

NEMIS- AEPAM. 2015. Pakistan education statistics 2013-14. Islamabad: Ministry of Federal Education & Professional Training. [ Links ]

Novelli, M., M.A. Lopez Cardozo and A. Smith. 2015. A theoretical framework for analysing the contribution of education to sustainable peacebuilding: 4Rs in conflict-affected contexts. Retrieved from: http://learningforpeace.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Theoretical-Framework-Jan15.pdf (accessed 26 October 2016).

Novelli, M. and A. Smith. 2011. The role of education in peacebuilding: A synthesis report of findings from Lebanon, Nepal and Sierra Leone. New York: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Ovichegan, S. 2015. Faces of discrimination in higher education in India: Quota policy, socialjustice and the Dalits. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pinnock, H. 2009. Language and education: The missing link. How the language used in schools threatens the achievement of education for all. Berkshire: CfBT and Save the Children Alliance. [ Links ]

Pugatch, T. and E. Schroeder. 2014. Incentives for teacher relocation: Evidence from the Gambian Hardship Allowance. Economics of Education Review 41: 120-136. [ Links ]

Sayed, Y. and M. Novelli. 2016. The role of teachers in peacebuilding and social cohesion: A synthesis report of South Africa, Uganda, Pakistan and Myanmar case studies. Research Consortium Education and Peacebuilding. University of Sussex.

Singal, N. 2015. Education of children with disabilities in India and Pakistan: An analysis of developments since 2000. Background paper for GMR 2015. UNESCO. Retrieved from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002324/232424e.pdf (accessed 26 September 2016).

Stewart, F. 2010. Horizontal inequalities as a cause of conflict: A review of CRISE findings. World Development Report 2011, a background paper. Retrieved from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTWDR2011/Resources/6406082-1283882418764/WDR_Background_Paper_Stewart. pdf (accessed 26 October 2016).

UNICEF. n.d. Key peacebuilding concepts and terminology. Retrieved from: http://learningforpeace.unicef.org/cat-about/key-peacebuilding-concepts-and-terminology/ (accessed 26 October 2016).

UNESCO. 2014 Teaching and learning: Achieving quality for all. EFA Global Monitoring Report 2013-14. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

UNESCO. 2015. Education 2030 Incheon Declaration and framework for action: Towards inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning for all. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

1 Pakistan is a federation with four provinces, i.e. Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan and the federal capital Islamabad.

2 The term is used for people who migrated from India to Pakistan and their descendants.

3 http://www.unesco.org/education/efa/ed_for_all/

4 'Source' refers to political influence that some applicants exert through their links with the 'source' of power.