Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 n.3 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/1516

ARTICLES

Teacher governance reforms and social cohesion in South Africa: from intention to reality

Thomas SalmonI; Yusuf SayedII, III

ICape Peninsula University of Technology Email: tomsalmon@yahoo.com

IIUniversity of Sussex. Email: Y.Sayed@sussex.ac.uk

IIICentre for International Teacher Education (CITE) Email: sayedy@cput.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The governance of teachers during apartheid in South Africa was characterised by high levels of disparity in teacher distribution and in conditions of labour. In the postapartheid context policies and interventions that govern teachers are critical, and teachers can be seen to be placed in a central role as actors whose distribution, employment, recruitment and deployment can serve to redress the past, promote equity and build trust for social cohesion. In this context, this paper examines several teacher governance mechanisms and interventions, namely the post provisioning norm and standards (PPNs), the Funza Lushaka Bursary Programme (FLBP), and the South African Council of Educators. The analysis suggests that undifferentiated policy frameworks for teacher governance result in measures that weakly account for differing contextual realities and persistent inequality. Additionally, the emphasis on technocratic measures of accountability in teacher governance interventions constrains teachers' agency to promote peace and social cohesion.

Keywords: teacher governance; trust, accountability; social cohesion; education; teachers; post provisioning norms and standards (PPNs); Funza Lushaka Bursary Programme (FLBP); South African Council of Educators (SACE); Codes of Conduct

INTRODUCTION

In South Africa colonial rule and apartheid policies splintered social identities along racial and ethnic lines, and were accompanied by economic disparities and inequalities along race and class divides. The political shift in post-apartheid South Africa from authoritarian to democratic rule was constituted to respond to this legacy through a commitment to representative and participatory democracy, accountability, transparency and public involvement. Education policies since 1994 have sought to give effect to the Constitution which 'requires education to be transformed and democratised in accordance with...human rights' (DBE 2015). Core to the transformation agenda have been shifts in the institutions that produced such inequities, including education institutions such as schools. At the same time, the state has sought to develop a progressive education agenda for teachers and learners that enables the development and sustainability of a non-racial, democratic society - the 'rainbow nation'.

Despite important gains that have been made, over 22 years later this ideal continues to be significantly challenged and in many ways remains elusive. For example, the 2015 South African Reconciliation Barometer (Hofineyr & Govender 2015) found that 67.3% of South Africans have little to no trust in people of a different race group and 61.4% felt that race relations in the country had stayed the same or worsened since 1994. Similarly, Struwig, Roberts and Derek Davids (2011) in developing a 'Social Cohesion Barometer' for South Africa in 2011 warned that race, class, ethnic and regional divides 'simmer beneath the national surface and may re-erupt' if 'economic, political or demographic stresses worsen'. This post-Arab Spring admonition was swiftly followed by the killing of miners in Marikana and 'Clean Sweep' campaigns to remove traders and hawkers from the streets in Pretoria and Johannesburg (Cox 2012). These actions, alongside the persistence of racially offensive and derogatory comments by individuals, as well as xenophobic attacks since 2008 (Baranov 2015), all tend to throw into sharp relief the fragility of attempts to effect social cohesion in post-apartheid South Africa. In short, these events highlight critical disjunctures between the post-apartheid state's policy discourse on social cohesion and the question of how the terms of membership in the political community of the 'new' nation are constituted (Barolsky 2013). Within education the legacy of a racialised apartheid past has taken on new inflections in the post-apartheid order as teachers, parents and learners cross racial boundaries, with the black middle class migrating to wealthier previously white schools. As such class and race are interlinked in how processes of inequality are reproduced, fundamentally eroding the incentives for cross-class and cross-race coalitions that have the potential to galvanise social cohesion. The entanglement of class and race in post-apartheid South Africa has thus sometimes exacerbated inequity and fractured the possibility of relations of common belonging and trust.

Within this context, teachers in South Africa are increasingly being positioned and responded to as mediators across the country's existing divides, as actors whose recruitment, training, employment, and deployment are seen as key processes towards redressing the past and promoting equity as fundamental to social cohesion.

This paper takes as its starting point these latter concerns. More specifically, it explores how existing national policy frameworks and associated interventions around teacher deployment, recruitment and trust appear to effect social cohesion and social justice within education. It is particularly concerned with how teachers are rendered accountable to professional bodies, to their employers and to the communities they serve in different ways. It then considers whether these processes are able to strengthen social cohesion across the fragmented realities of the schooling system in ways that empower teachers. Social cohesion in this paper is understood as social justice, which as articulated by Fraser (1998), requires attending to systemic processes of redistribution, recognition and representation. This stance requires that teacher governance interventions, such as those focused on in this paper, facilitate the (re)distribution of teachers in order to ensure equitable access to quality education for all accompanied by efforts to build teacher trust. Moreover, such interventions must also seek to build trust, particularly between teachers, employers and diverse communities in order to mitigate how group norms around performance, trust and the allocation of resources continue to reflect historically and geographically determined patterns of inequality. As such, the interventions discussed and reviewed in this paper are seen as key leverage mechanisms for promoting redistribution and fostering trust, noting however, that purely redistributional policies are 'necessary but not sufficient conditions' for guaranteeing social inclusion (Labonte 2004).

However, as Novelli et al. (2016) argue, within post-conflict contexts in particular interventions can fail to support social cohesion and social justice goals, and may establish weak conditions for teacher governance that can leave teachers themselves operating within a system that works against their efforts. Teachers for example may experience fragmented recruitment and management approaches, high teacher attrition and low pay, 'localised' deployment in remote areas, recruitment and promotion based on patronage networks and high levels of teacher turnover and low levels of retention. The authors suggest that governance interventions should be able to mitigate the deepening of existing inequities that run along entrenched geographic, ethnic, and socio-economic lines. Teacher governance interventions are thus, in the context of this paper, framed as crucial to building trust and effecting equity at a systemic level in education, which in turn is essential to ensuring that teachers are empowered as agents of social cohesion. As such teacher deployment and recruitment processes should ensure that there is an equitable distribution of teachers across all schools and for example address inequities in the conditions of employment faced by teachers. Teacher governance interventions should therefore factor in measures designed to establish equity and equitable relations in this way in order to contribute to (re)building relations of trust.

In the South African context, teacher trust is also impacted by how the legacy of apartheid has shaped teachers' roles. Relations of trust within the teaching profession in South Africa reflect divides between unionist and professional activities within and between different unions in the process of collective bargaining (Kerchner & Caufman 1995). In effect a divide surfaces between teachers acting as 'workers' and 'professionals' as a powerful legacy of the struggle against the apartheid education system and government, a point also illustrated by Heystek and Lethoko (2001) in their account of how senior leaders such as black principals came to be perceived as apartheid government collaborators rather than as professionals.

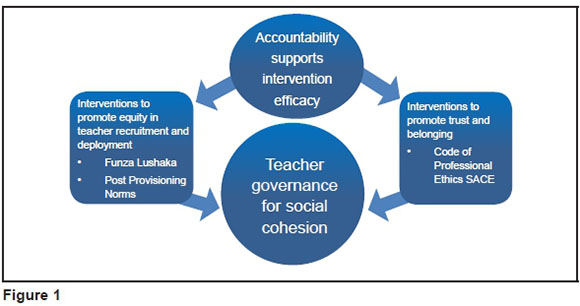

Within this background, this paper examines selected teacher governance interventions currently in place in South Africa. It conceives of these interventions as encompassing those that foreground equity and those that promote trust for belonging, such as the SACE's Code of Professional Ethics. Key to all these interventions is accountability as interventions to promote equity and build trust rest on groups and individuals acting accountably towards each other and to the intended aims of the policies. The approach of this paper in studying these teacher governance interventions is captured in the heuristic framework shown in the figure below:

The framework above conceives of post provisioning norms and Funza Lushaka interventions principally as equity interventions in that they seek to mitigate and erode inequities. They thereby enhance the possibility for creating social cohesion and cohesive communities in which members agree to act in common ways in relation to certain social norms (Boytsun, Deloof & Matthyssens 2011). SACE's Code of Professional Ethics examined in this paper is conceived of as a measure to build relations of trust and belonging of teachers to each other, to government, to schools, and to communities and learners, thereby acting as a key lever for effecting social cohesion. Within this framework the paper argues that while there is no direct link between accountability and social cohesion through teacher governance, effective forms of accountability to and for equity measures and trust efforts such as the Code of Professional Ethics are key for realising social cohesion aims in teacher governance policy.

The paper begins with a brief discussion of the methodology followed by a discussion of three teacher governance interventions. These are the post provisioning norms and standards (PPNs) that guide the deployment of teachers across the system, the Funza Lushaka Bursary Programme (FLBP) of national government that seeks to incentivise the entry of students into teacher education programmes, and the framework for professional ethics and conduct presently in place through the South African Council of Educators (SACE) as the regulatory body for the teaching profession. The paper then reflects on these interventions and considers how they address (or do not) existing patterns of inequality and enhance (or do not) the exercise of teacher agency, and configure relations of trust as a way of building social cohesion. The paper concludes by considering these interventions in a context of education policy reforms which have since the ending of apartheid sought to redress inequities as a way of building social cohesion.

METHODOLOGY

This paper is based on a country report on the role of education and peacebuilding in South Africa and is a research output from the Research Consortium on Education and Peacebuilding, and a DFID-ESRC Pathway to Poverty Alleviation Research Project.1Research for this report was conducted by the University of Sussex, in collaboration with a local partner from the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT) in South Africa (see Sayed et al. 2015). The research sought to examine how teacher government interventions to promote equity and trust can serve to build social cohesion. The research on which this paper draws is based on an extensive document review before and after the field research. The document review included national development plans, relevant policies, national education sector plans, education sector reform plans, curricula, as well as other (academic) research and studies. This was augmented by 25 interviews with government officials, education planners, teacher education providers, teaching professionals, student teachers, local and international NGOs, and local communities about the three teacher governance policies and programmes noted above.

EQUITY AND TRUST FOR SOCIAL COHESION THROUGH SPECIFIC TEACHER GOVERNANCE INTERVENTIONS

The three teacher governance interventions noted above are now discussed and explored in relation to their ability to promote equity and build trust for social cohesion in the education system.

Post provisioning norms and standards

In South Africa the deployment of educators is realised using a centralised mechanism, a formula-driven post-provisioning model (PPM) that allocates educators, as human capital, to public schools based on learner enrolment numbers. In addition to allocating teaching staff, the PPM also allocates School Management Team (SMT) staff to each school. The outcome of the PPM formula is called the post provisioning norms (PPN).

The post provisioning norms were established as the outcome of a political settlement post 1994 to find a defensible allocation mechanism to rebalance the skewed patterns of educator distribution under apartheid, while also reducing the high government expenditure on educator salaries. Known initially as the 'National Norm', it was subsequently formulated as the 'Post Provisioning Norm' in 1998 (ELRC 1998).

As such the PPN are an example of a policy post 1994 that has since become a regulatory framework, serving as a rational distribution mechanism for all posts to schools, while also ensuring that these posts are affordable to the state. Two key principles inform the latter imperative:

• Available posts should be 'distributed among schools, proportionally to their number of weighted learners';

• A 'weighting' is applied to particular learner numbers to compensate for subjects and/or grades that require greater concessions than others, as well as the overall size of the school in terms of learner numbers.

In 2002 some changes were made to the PPN that introduced a redress factor into the framework. This was intended to enable provinces to use 5% of the available posts for poverty redress. In 2008 the norms were revised again to more directly entrench a pro-poor approach to post provisioning and drew on the existing school quintile system to do this. Thus this model was refined over time to ensure a sharper equity targeting of post provisioning.

Several challenges have emerged as the norms, including their more recent revisions, have been put into practice especially as a governance mechanism aimed at addressing equity concerns and thus enhancing social cohesion. First, despite the alterations made, Prew et al. (2015) have suggested that unlike the Amended National Norms and Standards for School Funding (ANNSSF) (DoE 2006), the PPN model does not sufficiently and explicitly articulate the use of post provisioning to pursue the goals of equity, access and redress. For example, the model initially assigned more weight in areas that benefited ex-Model C ex-white schools, favouring dual-medium schools and allocating extra weighting for learners taking subjects such as music and drama - subjects usually provided in more privileged schools. Moreover, Goodlife (2012) notes that the PPNs do not take into account the distribution of qualified educators and fail to provide for and promote the needs of a diverse curriculum, especially within rural areas. Similarly, she suggests that they also fail to factor in the reality that some public schools are more easily able to raise funds, through school fees for example, enabling them to employ additional educators.

A further limitation of the existing PPN model is that it relies on the capacity of the Provincial Education Departments (PEDs) to manage the burden of administration and implementation. The process of moving posts and educators around is a highly complex process and has proved to be destabilising for curriculum delivery and creates severe management challenges in certain provinces with significant variation in application (Prew et al. 2015). For example, the PPN redress factor described above appears only to be applied in the Western Cape (Gustafsson 2016), and research commissioned by UNICEF (DBE 2015c, 6) also showed that at the time of the research at least four different versions of the PPN were in use across the provinces. The report argues that this means that there may be 'a significant risk that a province may implement an incorrect version of the Policy' (DBE 2015c, 7). Similarly, Gustafsson (2016) shows that while in Gauteng and the Western Cape the application of the model shows less discrepancy in practice, and the Northern Cape, Mpumalanga and Free State manage this with some discrepancies, the Eastern Cape stands out as particularly problematic in this regard with around 6.3% of all public educators considered 'misplaced'. His study also suggests that only three provinces (Free State, Northern Cape and Western Cape) were distributing educators in a pro-poor manner, in accordance with the norms. In Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal, he shows that fewer educators have been employed in poorer schools, in effect undermining the intent of the post provisioning policy in terms of shifting persistent post-apartheid legacies of inequality between regions.

A third concern that has been raised relates to the challenges that appear to exist at the schooling level around the application of the PPNs. Thwala (2014) shows that schools find that bureaucratic red tape often leads to delays in the appointment of teachers, leaving them without staff at the beginning of the year. Often more privileged ex-Model C schools however, are effectively able to bypass these delays by appointing a teacher via the School Governing Body (SGB) and then later recommending them to be appointed as state-paid teachers. Thwala (2014) also shows that in contrast, poorer schools have no choice but to recruit teachers from the redeployment list of excess teachers or from the placement list of bursary beneficiaries as prescribed by the model (that is, those teachers who were the recipients of the Funza Lushaka Bursary).

However, the concerns articulated above regarding recruitment in respect to the PPNs also highlight more systemic problems, about barriers to recruitment for example. In South Africa, Pattillo (2012) and Qukula (2015) both show how factors such as incentives for cadre deployment and nepotism may result in processes of recruitment whereby teachers collectively headhunt for candidates that show a 'fit' with the ethos of the school, or where poorer schools may resort to 'fitting' the curriculum around the teachers that they are given rather than the curriculum.

In summary, within this context the PPN as a general model of post provisioning with a weak focus on equity has arguably had minimal impact to date on patterns of teacher redistribution in South Africa. Central to why this is the case is that it does not impede the highest qualified and best paid educators from gravitating disproportionately towards the former Model C schools and thus the most well-resourced environments. It therefore has not explicitly sought to eliminate privilege in terms of access to subject choices, resources that improve teaching and learning and qualified subject teachers -all features of the more privileged schools. Moreover, while the focus of the PPN model has been on regulating fixed learner-teacher ratios, it has been weaker in dealing with mismatches between schools and provinces in terms of the provision of subject advisors, a critical resource for supporting teachers. Thus, the PPN appears to have been unable significantly to shift inequalities in teacher deployment that run along geographical and historical lines. As a mechanism, it appears that it has been unable to create the conditions to rebuild the kind of trust around teacher deployment, particularly between national government and the provinces, as well as teacher unions for example within the Eastern Cape, that are necessary to rebuild an equitable and effective education system. A government official noted in this respect that efforts at intergovernmental levels to foster stronger accountability and trust often tend to fall back instead upon procedural solutions, saying that:

when you don't have the mutual respect in the intergovernmental working together for the greater good of the country constitutional perspective on matters, then national resorts to; 'let's give them norms and standards'. So how norms and standards may help is in the blunt instrument business of forcing them to allocate money to something, otherwise you can have one of the NGOs like Equal Education that is taking you to court, but even that really, the Eastern Cape has being taken to court many times and they just ignore the court order. So we've got a problem now but yet our solution is still the same old, same old, let's give more, more stuff, not, let's go down there and ask people, why don't you do this.

A UNICEF commissioned evaluation of the PPNs (DBE 2015c) recommends that the system move away from an 'educator focus' to a 'school focus'. It is suggested that the Department of Education should consider targeting incentives to encourage highly qualified and motivated teachers to choose to teach high value subjects at poor rural schools in remote districts, rather than lower valued subjects offered at rich peri-urban schools in the same district. Whether this recommendation will be accepted and whether it is likely to shift the existing, deeply embedded inequalities remains to be seen.

Funza Lushaka Bursary Programme

The Funza Lushaka Bursary Programme (FLBP) is a multi-year, service-linked bursary scheme of the national government that was originally implemented in 2007 to raise the number of newly qualified teachers entering schools to meet the teacher needs of marginalised schools, particularly in poor and rural areas, by offering full-cost bursaries to eligible students who enrol in specific Initial Teacher Education (ITE) programmes. The stated purpose of the programme is to ensure that the basic education sector responds adequately to the need for high quality teachers in nationally-defined priority areas (DBE 2015a). As such, it has the potential to improve the equitable distribution of teachers across the system. Further, students are incentivised to study teaching in areas in scarce skills because the bursary ensures them employment once they qualify, and the state is then able to deploy these graduates into these required subject areas. As a government official emphasised:

Remember, we cannot fund every child who wants to become a teacher, but we can try and provide that impetus, that stimulus to keep the interest in teaching alive because somebody will consider teaching because there is this bursary available.

Van Broekhuizen (2015) suggests that while the FLBP and other service-linked funding mechanisms may be designed to remedy existing gaps in teacher supply, these goals may be restricted by other factors that impact on teacher supply and demand in South Africa. He points out that there is a constant mismatch between the kinds of schools that newly qualified teachers want to work at, and where they are most needed, which are the most marginalised schools.

One of the consistent challenges for the programme is ensuring the representation and recognition of diversity as well as the redistribution of teachers. As one government official puts it in regards to raising the profile of educators through the teaching of African languages, as a crucial lever to building social cohesion in South Africa, which requires greater coordination to support incentives for different language groups:

Unless we come to that point, your incentive will always be short term because the broader paradigm out there still supports English as the medium of doing business and as the medium in which you will publish. So when you look at incentives for language groups, it goes down right into how a teacher is being prepared in that university and how they are being prepared to teach in a diverse language environment and it goes down into what literature they are being exposed to.

Thus, policies to promote African languages to build social cohesion struggle to overcome these structural inequities in society at large.

Despite the redistributive intentions of the programme, an ongoing challenge is the reluctance on the part of principals to accept the newly qualified bursary recipients. Principals in a study undertaken by Thwala (2014) stated that they would not take bursary holders and would prefer more experienced teachers for subjects like Grade 12 Mathematics. In fact, they may opt for foreign teachers who are perceived to be of a higher quality, thus choosing to disregard policy despite being instructed to prioritise the placement of bursary holders. A government official interviewed captured this challenge in the following way:

I think it's real concerns about capacity and financial resources at a provincial level to be able to deliver on this. Schools also, they don't, on the way we do the deployment, you know, some schools feel that we're imposing students on them into their schools, they could have chosen, selected other teachers, now we're imposing Funza Lushaka graduates onto them, so there's some resistance, their school governing bodies, definitely have that, and it's a real sentiment.

This distortion suggests that school level actors tend to see the policy in different ways and have limited trust in the policy as a way of incentivising equity when balanced against their own needs. As such, accountability to centrally directed interventions is subverted as actors do not have equal levels of trust in them. In reaction to actions of local actors who are seen to breach trust by not complying with policy requirements, the national department imposes more centralised measures to effect compliance. Thus, in 2014 the DBE took steps to strengthen the Funza Lushaka Programme through contractual agreements, removing the period within which Provincial Education Departments (PEDs) must offer an appointment, binding bursary holders to teaching in their subject specialisations and stipulating the province where a bursary holder will be placed upon graduation. Additionally, a range of measures to improve coordination, also with an implementation protocol, have sought to broaden the roles and responsibilities of PEDs (DBE 2015b). These measures speak to how trust is engendered in the education system and point to distrust between local and central actors.

FLBP in effect acts as a kind of mediated compromise between a range of imperatives. It is an incentive for broad-based teacher training to raise the profile of teaching, a targeted incentive for teachers to choose to work in rural areas and an incentive for teacher training to address skill-shortages in the economy (maths and science) -sometimes these priorities do not always fit comfortably together. For example, one of the difficulties facing the FLBP as a measure to redistribute teachers is that it eventually faces the challenge of being a top-down intervention that places little trust in local actors. A system of teacher governance in which there is mutual trust between national and local actors and in which there is local level support is key to effecting equity and is thus a cornerstone of social justice. As one government official put it:

The complexities around Funza Lushaka, for example, might be that a province would say that you've got these national priorities but we want to focus on these priorities and then we have to negotiate around it, it makes it a bit more difficult, or you want to place your Funza Lushaka bursary holders in this way, but we want to do it in this way and then you can negotiate around it and in those processes, sometimes, service delivery is the one that, and then social cohesion probably, that suffers. For example, we want provinces to be actively involved with recruitment, but if they don't make the human resource capacity available, and also the accountability mechanisms that goes around it, then the approaches will be half hearted and you will not have the quality that you aspired for at the beginning.

The FLBP as a key governance intervention seeks to promote a more equitable system of recruitment and deployment ensuring that teachers are in schools where they are needed most. It is intended to promote quality education and equity to build social cohesion. However, as it has been argued, the implementation of this programme faces differing approaches to the scheme at the provincial and local levels. Furthermore, attitudes and understandings of local actors about the scheme appear also to be affected by how relationships of trust and accountability are played out. As such, further research and support for new initiatives, for example such as the district-based teacher recruitment strategy2 aimed at selecting teachers who are resident in remote, rural districts, and combining the FLBP with a strong teacher mentoring model to train teachers who are committed to teach in these schools and communities are of critical importance.

Code of Professional Ethics (SACE)

The South African Council for Educators (SACE) is a regulatory body established through the South African Council for Educators Act (Act No. 31, 2000). It acts as a professional council to enhance the status of the teaching profession with a vision of excellence in education (SACE 2011, 4). It has the mandate to register and discipline teachers, and operates through codes of professional ethics and the development of disciplinary approaches. It is also responsible for regulating and managing the system of continuous professional teacher development (CPTD) in South Africa through the registration and quality assurance of CPTD providers.

A key framework in place to take forward this mandate is its Code of Professional Ethics, which states that educators are accountable to the learners, the parents, the community, their colleagues, their employer, and the council. Besides SACE's Code of Professional Ethics, the different teacher unions each have their own codes of conduct which align with that of SACE.

Through the Code of Professional Ethics SACE regulates various educator relationships with learners and their behaviour as professionals. For example, it requires that an educator refrain from any form of sexual harassment of learners. Similarly, educators are expected to 'keep abreast of educational trends and developments' and 'behave in a way that enhances the dignity and status of the teaching profession and that does not bring the profession into disrepute' (SACE 1997). It also regulates the educator's relationship with their employer, requiring that an educator 'serve his or her employer to the best of his or her ability' and must accept that 'certain responsibilities and authorities are vested in the employer through legislation' (SACE 1997).

As a body that needs to elicit trust from teachers and within the teaching profession and ensure compliance with the Code of Professional Ethics, SACE has faced several challenges. In the case of educator misconduct SACE is able to administer a caution or reprimand, or impose fines of up to one month's salary or remove a teacher from the register completely. However, at the same time, the DBE is also mandated under the Employment of Educator's Act (1998) to take disciplinary action where an educator violates the Act. Brock, Brundige, Furstenau, Holton-Basaldua, Jain and Kraemer (2014) argue that there are problems with this 'overlapping' role of SACE. They suggest that if the DBE finds an educator guilty of an alleged sexual offence but SACE does not, the educator will be dismissed but may not be struck off the teachers' register and may go on to teach at another school. They also point out that even if the educator is struck off the register, they may still be able to seek employment at a private school.

A key difficulty facing SACE is that it is burdened with broad competencies, but weak financial and organisation autonomy. Indeed the 2015 SACE annual report directly notes the shortfall in funding from the national department as a key weakness. Fundamentally, the challenge for SACE is that it operates along the principle of consensus building towards the development of its mechanisms aimed at ensuring trust. Teacher unions are strongly represented on the SACE council of 30 members with 18 representatives, and as such SACE describes itself as a 'council of the profession by the profession' (Interview with SACE representative, 2015), where the organised teaching profession holds an absolute majority. The strongest union proportionally holds the greatest sway based on membership numbers, and the chairperson of the council is also typically a senior national office bearer for the majority union. In short, as an institution SACE must work via consensus building to establish traction for its initiatives, for example by setting up bilateral agreements with unions for each of its programmes (Interview with SACE representative, 2015).

Notwithstanding these challenges, teachers accord SACE a high level of support as the body for promoting and building trust and accountability. A recent study of teacher professionalism in the Western Cape (Hoffmann, Sayed & Badroodien in press) suggests that SACE is one of the most important national bodies within the system which teachers see themselves as being accountable to, alongside the DBE and the PEDs. The study suggests that in contrast, teachers see themselves as less accountable to governance structures at the schooling level, such as their SGBs.

As an intervention to build trust, the dilemma of SACE points to consistent challenges in capacity and failures in implementation as noted above. This also points conceptually to the challenge in balancing centrally directed interventions and teacher agency to act autonomously at local levels. A clear indication of this are the codes of conduct for teachers that are simultaneously criticised for not being directive enough to administer sanctions upon teachers who transgress these codes whilst criticisms also point to the failure to give voice to teachers and their representatives (Govender & Sookrajh 2014). To this end there is a strong need for SACE to strengthen its capacity to enforce the Code of Professional Ethics and transgressions against the behaviours contained therein as a way of building trust in teachers. In this way SACE as a teacher led structure can promote accountability amongst teachers to uphold processes that build social cohesion.

DISCUSSION

From the preceding analysis there are several observations about the three governance interventions that seek to promote equity in recruitment and deployment and develop systems of trust to build social cohesion that warrant closer attention.

First, the discussion above presents an analysis of how teacher governance interventions such as the Code of Professional Ethics is underpinned by an approach in which change is enacted with limited teacher agency. The fractured system of teacher governance results in, as suggested in the analysis above, limitations on teachers' capacity to rebuild systemic trust and accountability in their schools. By focusing on formal and procedural forms of accountability in terms of, for example, compliance with codes of conduct, the interventions ignore the agency of teachers in negotiating trust and accountability with actors at local levels. The framing of these interventions and the shifts in greater specification and centralisation above suggest a lack of trust and belief in teacher professionalism. Teacher governance interventions are thus constrained in their capacity to recognise and support ways for teachers to exercise agency to participate in negotiating relations of trust and accountability. What surfaces is a logic of change with limited teacher agency in that the attainment of social justice goals are isolated from frameworks for participation (Sayed & Ahmed 2009). This logic of change does not recognise that teacher agency is shaped by their identities as social beings, their prior experiences (Priestley, Biesta & Robinson 2012) and the contexts in which they find themselves.

Second, the analysis suggests that whilst teacher governance interventions such as the FLBS and the PPN seek to effect equity, they are arguably often not sufficiently directive, or are characterised by transgressions undermining the basis for social cohesion. In effect it seems that while systemic interventions such as those discussed in this paper seek to delineate the procedures for regulating actions and behaviours, they are not directive enough to deliver stronger forms of accountability and trust. As a result, changes to the policies discussed in this paper and more recent policies and actions by the national government, such as the districts governance policy (DBE 2013) and the constitutional court judgment by which central government has reassumed the power to redraw zoning policies for school admissions, demonstrate that the government has opted to intervene more to regulate actions, as it has more broadly by way of performance agreements with government departments. However, this paper suggests that the accountabilities identified by teachers themselves and the accountabilities identified by the government and employers ideally should be more closely aligned through the mechanisms of teacher governance. In the absence of clear alignment, attempts to stimulate convergence by central authorities may undermine the use of collective wisdom and the agency of teachers in order for the profession to self-regulate. If accountability mechanisms are not capable of building mutual trust and ensuring the support of teachers, they may continue to operate at a distance from the teachers they try to assist and will not strongly support social cohesion. Alternative thinking about approaches to trust should move away from a focus on formal and procedural forms of teacher accountability.

Third, it is apparent that across all the policies and programmes the legacy of conflict that characterised the apartheid education system persists within institutional structures and influences how teacher governance interventions continue to operate. They operate within a context of low trust in which teacher governance interventions seek mainly to control and regulate behaviours and where top down procedures restrict or undermine relationships of mutual trust between teachers and their employers. Within SACE the regulation of teachers in their professional practice is achieved through power sharing arrangements made by representatives of the organised profession. Similarly, centrally redistributive measures to allocate resources remain tied to narrowly defensible formulas. The FLBP offers the opportunity to reallocate teachers across apartheid divides. However, it has had to make recourse to intergovernmental protocols and contractual agreements with novice teachers, in order to be more effectively operationalised at local levels where there is a lack of strong buy in. In short, the limitations of teacher governance policies to affect redress suggest a weak configuration of relationships of trust, as well as a narrow framing of redistribution and a prevalent acceptance of certain unintended consequences. A particular weakness is their failure to sufficiently engage with the legacy of Bantu education and the associated 'woundedness' of educators (Nyoka, DuPlooy & Henkeman 2014). The discussion above in relation to teacher governance shows how deeply scars may become engrained not only at a psychological level (Lee 2012) but as a 'structured wound' (Interview with IJR representative, 2015) within processes and the education system's trajectory and its struggle to address the structural conditions that perpetuate inequality in order to effect genuine reconciliation (Hamber & Kibble 1999).

Fourth, the analysis suggests that while governance reforms go some way to embed a wider variety of accountability mechanisms within teaching, they have in almost every sense tended to avoid considering the act of teaching itself as important. Tighter regulation does not prioritise the agency of teachers to do differently what they already do, or the idea that better approaches to teaching can be learned and can support change or what teachers (and others) believe about teaching, or whether it is supportive of change. As such Moller (2009) concludes that there has instead been a promulgation of standards and codified descriptions of teachers' work, which tend to operate principally as a 'regulative framework of accountability'.

Fifth, issues of trust in relation to teacher governance are embodied within notions of teacher professionalism. Trust measures founded upon a notion of endorsing organisational and managerial professionalism, to which governments tend to be drawn, stand in stark contrast to the occupational and democratic professionalism that teachers tend to favour (Gamble 2010; Hargreaves & Fullan 2012).

Finally, research (Spaull 2015) suggests that the effective implementation of teacher governance policies is principally challenged by a lack of capacity, and therefore require the kind of support that will enable them to build this capacity. Less experienced teachers it is argued, who lack support or training, may struggle to build relationships of trust with learners. Whilst true to a point, this paper argues that there are deeper flaws in the policies and that where the authority, competency and attitudes of teachers are merely held formally accountable, their autonomy to act as professionals is further eroded. Increased teacher regulation through tighter accountability procedures may not strengthen the capacities for building trust between learners and teachers, or the ethical and professional basis upon which trust within schools can be addressed.

CONCLUSION

This paper has sought to throw into sharp relief teacher governance interventions to effect equity as the basis for durable and just social cohesion. The argument made is that while the policies have sought to build trust and promote equity, they have not destabilised the relative advantage of schools that were favoured during apartheid. Actors' experiences of the different forms of policy interventions are uneven and remain marked by the legacies of past injustice and conflict. Teacher governance interventions intended to effect equity in practice appear strongly shaped by how they play out at school, provincial and national levels and across the segmented schooling system.

A key tension in teacher governance interventions in South Africa is how they seek to balance tight regulation and teacher freedom. On the one hand, a strongly unified system of institutionalised mechanisms for trust and accountability in teacher governance may allow different forces to pull against each other. On the other hand, overregulation is difficult given the divides in the education system, which still persist long after the formal ending of apartheid. Thus, the wealthier schools, wealthier provinces, and assertive SGBs tend to ignore and subvert such directives whilst the poorer schools struggle with the impact of historic and structural disadvantage. Social cohesion as such is differentially experienced by schools serving the wealthy and largely white schools which are spatially set aside from the 'other' (Sayed et al. 2015).

The challenges of realising the intended aims of teacher governance policies for social cohesion emerge out of the complexity of a reform agenda that seeks to address the pervasive influence of the legacy of apartheid on educational institutions in South Africa. What surfaces in the interventions examined here are contradictory organising processes - bureaucratic compliance and procedurally driven forms of accountability that rub against teacher agency to effect trust, belonging and participation. In this respect strengthening teacher governance interventions in practice requires balancing different sets of expectations between actors (Novelli et al. 2016). This requires forms of regulation that are based on trusting teachers and that do not simply lead to a 'teacher blame' culture (Sayed et al. 2015).

Echoing the work of Lewis and Naidoo (2007), this paper suggests that teacher governance policies in South Africa enact a technocratic conception of policy. In the face of wide disparities across the education system, interventions are underpinned by the unfounded assumption that a uniform structure will yield a uniform response to governance policies. Although teachers can and should act for social cohesion, they require focused teacher governance policies that are conceptually sound, well-structured and effectively implemented so that more dynamic and agential forms of trust and equity can be (re)constituted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT:

We would like to thank the ESRC-DFID for a research grant for the project Engaging Teachers in Peacebuilding in Postconflict Contexts: Rwanda and South Africa (PI: Yusuf Sayed). However, the views expressed in this paper reflect that of the authors and not the funders.

REFERENCES

Baranov, A. 2015. Rainbow nation goes up in smoke on Durban's streets. BDlive. Retrieved from: http://www.bdlive.co.za/opinion/2015/04/17/rainbow-nation-goes-up-in-smoke-on-durbans-streets (accessed 5 November 2016).

Barolsky, V. 2013. Interrogating social cohesion: The South African case. In Regional integration and social cohesion perspectives from the developing world. Edited by C. Moore, 12. Brussels: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Boytsun, A., M. Deloof and P. Matthyssens. 2011. Social norms, social cohesion, and corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review 19(1): 41-60. [ Links ]

Brock, R., E. Brundige, D. Furstenau, C. Holton-Basaldua, M. Jain and J. Kraemer. 2014. Sexual violence by educators in South African schools: Gaps in accountability. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand School of Law. [ Links ]

Cox, A. 2012. CBD Clean Sweep. The Star. Retrieved from: http://www.iol.co.za/the-star/cbd-clean-sweep-1394105 (accessed5 November 2016).

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2013. Policy on the organisation, roles and responsibilities of education districts. Notice 300 of 2013.

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2015a. Consolidated action plan to improve the Funza Lushaka Bursary Programme recruitment and placement. Retrieved from: pmg.org.za/files/150421Consolidated.doc (accessed 6 November 2016).

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2015b. Implementation protocol on the Funza Lushaka Bursary Programme. Retrieved from: http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/150421Implementation_Protocol.pdf (accessed 5 November 2016).

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2015c. Post provisioning norms (PPN). Powerpoint presented at the Portfolio Committee Meeting, CapeTown.

Department of Basic Education (DBE). 2015d. Action plan to 2019: Towards the realisation of schooling 2030. Pretoria: DBE. [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE). 2006. Amended national norms and standards for school funding. Government Notice no.869. Pretoria: DoE. [ Links ]

Education Labour Relations Council. 1998. Rationalisation and re-deployment of educators in the provisioning of educator posts. Resolution No.6. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. 1998. From redistribution to recognition? Dilemmas of justice in a 'post-socialist' age. In Feminism and Politics. Edited by A. Phillips, 430-60. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Gamble, J. 2010. Teacher professionalism: A literature review. Johannesburg: JET Educational Services. [ Links ]

Govender, D.S. and R. Sookrajh. 2014. 'Being hit was normal': Teachers' (un)changing perceptions of discipline and corporal punishment. South African Journal of Education 34(2): 01-17. [ Links ]

Gustafsson, M. 2016. Teacher supply and the quality of schooling in South Africa - Patterns over space and time. 03/16. Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers. Stellenbosch: University Of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Hamber, B. and S. Kibble. 1999. From truth to transformation: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. London: Catholic Institute for International Relations. Retrieved from: http://www.csvr.org.za/index.php/publications/1714-from-truth-to-transformation-the-truth-and-reconciliation-commission-in-south-africa.html (accessed 1 November 2016). [ Links ]

Hargreaves, A. and M. Fullan. 2012. Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Heystek, J. and M. Lethoko. 2001. The contribution of teacher unions in the restoration of teacher professionalism and the culture of learning and teaching. South African Journal of Education 21(4): 222-27. [ Links ]

Hofmeyr, J. and R. Govender. 2015. SA reconciliation barometer 2015 - National reconciliation, race relations, and social inclusion. Institute For Justice and Reconciliation. Retrieved from: http://www.ijr.org.za/uploads/IJR_SARB_2015_WEB_002.pdf (accessed 5 November 2016).

Kerchner, C.T. and K.D. Caufman. 1995. Lurching toward professionalism: The saga of teacher unionism. The Elementary School Journal 96(1): 107-22. [ Links ]

Labonte, R. 2004. Social inclusion/exclusion: Dancing the dialectic. Health Promotion International 19(1): 115-21. [ Links ]

Lee, P. 2012. How Bantu education has deepened our wounds and blocked our progress - and a way out? Retrieved from: https://kairossouthernafrica.wordpress.com/2013/11/17/how-bantu-education-has-deepened-our-wounds-and-blocked-our-progress-and-a-way-out-bishop-peter-lee/ (accessed 2 November 2016).

Lewis, S.G. and J. Naidoo. 2007. Technocratic school governance and South Africa's quest for democratic participation. In School Decentralization in the Context of Globalizing Governance. Edited by H. Duan, 133-58. Netherlands: Springer. [ Links ]

Møller, J. 2009. School leadership in an age of accountability: Tensions between managerial and professional accountability. Journal of Educational Change 10(1): 37-46. [ Links ]

Novelli, M., G. Daoust, J. Selby, O. Valiente, R. Scandurra, L.B. Deng Kuol and E. Salter. 2016. Exploring the linkages between education sector governance, inequity, conflict, and peacebuilding in South Sudan. Sudan: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Ntuli, G.M. 2012. The effects of the educator post-provisioning model in the management of public schools in iLembe District. Masters dissertation. KwaZulu-Natal: University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Nyoka, A., E. DuPlooy and S. Henkeman. 2014. Reconciliation for South Africa's education system. European Lifelong Learning Magazine. Retrieved from: http://www.elmmagazine.eu/articles/reconciliation-for-south-africa-s-education-system (accessed 4 November 2016).

Pattillo, K.M. 2012. Quiet corruption: Teachers unions and leadership in South African township schools. Honours dissertation. Wesleyan University. Retrieved from: http://wesscholar.wesleyan.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1912&context=etd_hon_theses (accessed 5 November 2016). [ Links ]

Prew, M. and F. Maringe, eds. 2015. Twenty years of education transformation in Gauteng 1994 to 2014: An independent review. Baltimore, Maryland: Project Muse. Retrieved from: https://muse.jhu.edu/books/9781920677794/ (accessed 10 November 2016). [ Links ]

Priestley, M., G. Biesta and S. Robinson. 2012. Teachers as agents of change: An exploration of the concept of teacher agency. Working Paper No. 1, Teacher Agency and Curriculum Change. University of Stirling. Retrieved from: https://www.stir.ac.uk/media/schools/education/documents/teacheragency/ What%20is%20teacher%20agency-%20final.pdf (accessed 20 October 2016).

Qukula, Q. 2015. Interference of teacher trade unions affecting quality education in SA. Retrieved from: http://www.702.co.za/articles/4679/interference-of-teacher-trade-unions-affecting-quality-education-in-sa (accessed 20 October 2016).

Sayed, Y. and R. Ahmed. 2009. Education decentralisation in South Africa: Equity and participation in the governance of schools. Paper commissioned for the EFA Global Monitoring Report 2009, Overcoming Inequality: Why Governance Matters. Retrieved from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001787/178722e.pdf (accessed 21 October 2016).

Sayed, Y., A. Badroodien, Z. McDonald, T. Salmon, L. Balie, T. De Kock and C. Garisch. 2015. Teachers and youth as agents of social cohesion in South Africa. Cape Town: Centre For International Teacher Education (CITE). [ Links ]

South African Council for Educators (SACE). 1997. The Code of Professional Ethics. Retrieved from: http://www.sace.org.za/Legal_Affairs_and_Ethics/jit_default_21.The_ Code_of_Professional_Ethics.html (accessed 3 October 2016).

South African Council of Educators (SACE). 2011. Redefining role and functions of the South African Council for Educators. Centurion: SACE. Retrieved from: http://www.sace.org.za/upload/files/The%20Role%20of%20the%20South%20Afric an%20Council%20for%20Educators.pdf (accessed 20 October 2016). [ Links ]

Spaull, N. 2015. Accountability and capacity in South African education. Education as Change 19(3): 113-42. [ Links ]

Struwig, J., B. Roberts and Y. Derek Davids. 2011. From bonds to bridges: Towards a social cohesion barometer for South Africa. HSRC. Retrieved from: http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/review/November-2011/bonds-bridges (accessed 23October 2016).

Thwala, S. 2014. Analysis of management constraints in the distribution of qualified mathematics and science teachers in a post-1994 education system of South Africa: A case study of senior secondary schools in the Mpumalanga Province. Doctoral dissertation. University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Van Broekhuizen, H. 2015. Teacher supply in South Africa: A focus on initial teacher education graduate production. WP07/201. Stellenbosch Working Paper Series, Stellenbosch University. Retrieved from: http://www.ekon.sun.ac.za/wpapers/2015/wp072015/wp-07-2015.pdf (accessed 20 October 2016).

1 The views expressed in this report do not reflect that of UNICEF, DFID and ESRC or its partners. Work for this project was funded by a grant from DFID-ESRC, Grant Number ES/L00559X/1.

2 DBE/ELMA Foundation/Save the Children South Africa programme on district-based teacher recruitment strategy