Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Education as Change

versión On-line ISSN 1947-9417

versión impresa ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 no.2 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/732

ARTICLES

'Youth amplified': using critical pedagogy to stimulate learning through dialogue at a youth radio show

Adam Cooper

Human Sciences Reseach Council and Stellenbosch University Email: adcoops1980@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

In this paper I describe and analyse how critical pedagogy, an approach to teaching and learning that encourages students to reflect on their socio-political contexts, may stimulate critical consciousness and dialogue at a youth radio show. The participants, who attended four diverse Cape Town high schools and predominantly lived in poor townships, named the show Youth Amplified. Youth Amplified dialogues were catalysed by a range of materials, including documentary Alms, newspapers and academic articles, which participants engaged with prior to the show. Participants then generated questions, which contributed to the dialogues that took place live on air. Two central themes emerged from the radio shows. First, the values and discourses of elite schools were transported to Youth Amplified and presented as incontestable truths that often denigrated marginalised learners. Second, participants used 'race' as a marker of social difference to make sense of peers and South African society. I argue that critical pedagogy interventions also need to work with educators to reflect on inequalities and socio-political contexts, if such interventions are to be successful. The show illuminated that young South Africans want to speak about racialised and class-based forms of historical oppression, but that these kinds of discussions require skilled facilitation.

Keywords: Youth; critical pedagogy; dialogue; race; informal learning

AMPLIFYING SOUTH AFRICAN YOUTH ON RADIO

Introduction

This article explores how a critical pedagogy programme, namely a youth radio show in Cape Town, South Africa, promoted dialogue and developed critical consciousness amongst a diverse group of young people. Critical pedagogy is an approach to teaching and learning that encourages students to reflect on their sociopolitical contexts, catalysing transformative actions and, in turn, changing oppressive structural conditions. Critical pedagogy should be an urgent priority in South Africa, a country that has suffered from widespread human rights violations and is currently one of the most unequal societies worldwide. However, South African educational research remains fixated on explanations for South African students' poor performance in, for example, literacy and numeracy tests (see for example Bloch 2009; Fleisch 2008; Taylor, Muller & Vinjevold 2003; van der Berg 2008). While literacy and numeracy may well contribute to eradicating poverty in the long term, they are insufficient to producing a citizenry that can think critically, reflect on its shortfalls and work towards a more equitable, multi-racial society. Critical pedagogy therefore represents a complementary form of education, one that can help to develop young people who possess the skills necessary to participate in a modern knowledge economy and, simultaneously, produce self-reflexive citizens committed to attaining social justice.

The critical pedagogy youth radio show took place during 2011 and 2012 at a community radio station that was founded in 1992. The founder originally produced a 'talking newspaper': cassette tapes of the speeches of banned activists, politically charged music and revolutionary poetry. These founding influences were apparent in the radio station's ideology and practices, manifesting in left-wing radio content and personnel. Students from four diverse high schools participated in the programme. During apartheid, separate education departments existed for children classified as white, black African, coloured and Indian, with schools from the former white, black African and coloured departments represented at the radio show. School segregation was congruent with the apartheid government's other draconian segregation policies that permeated people's lives. This legislation and these oppressive practices continue to influence ideas and discourses that circulate at schools in the current period.

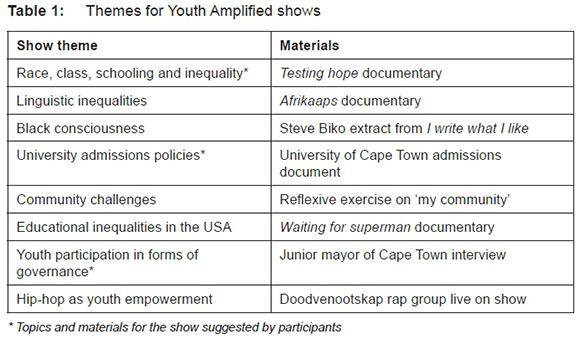

Participants named the programme Youth Amplified, indicating their desire to 'amplify' young people's ideas and opinions across the city of Cape Town. The idea for the programme, conceptualised by the station manager and a volunteer, was to use materials to stimulate discussions on education and other issues that the young people thought were important. Prior to each live show the group watched documentaries on social justice related topics, they read newspaper articles and engaged with academic texts. Materials were chosen by the participants or the facilitator - a volunteer at the radio station - and were used to generate questions that were written down by participants before the show. The themes for a sample of the live shows are presented in table 1. The materials that were engaged with highlighted social injustices and inequalities in South Africa, illustrating how Youth Amplified could be considered a form of critical pedagogy.

Critical Pedagogy

True critical pedagogy, as theorised by Paolo Freire (1970), is based on stimulating consciousness amongst oppressed peoples in order to eradicate structural oppression. Although the youth radio show did not, primarily, attempt to reduce structural oppression and disrupt relations of power, the programme contained a number of practices that were integral to Freire's philosophy. These included promoting conscientisation and dialogue. 'Conscientisation' refers to an increased awareness of economic, social and political injustices. Through conscientisation and sociopolitical development, critical pedagogy aims to invigorate students to act and assert themselves as agents, question their assumptions and develop an appreciation for history (Duncan-Andrade & Morrell 2008; Giroux 2007). This educational approach differs from the dominant schooling model, in which students are perceived as stagnant, empty vestibules into which knowledge is 'poured' or 'banked' (Camarota & Romero 2006).

As a form of critical pedagogy that avoided the 'banking' model of education, Youth Amplified attempted to galvanise active learning and develop socio-political consciousness through the form and content ofthe programme. The materials the group engaged with were designed to stimulate awareness of inequalities and injustices in South Africa. Active learning was promoted by the youth themselves facilitating and exclusively participating in the show. This kind of informal educational context may have spillover effects that positively influence young people's engagement in classrooms. In America, socio-political development among low-income youth of colour has been associated with higher academic achievement, optimism about the future, increased personal competence and greater occupational expectations and attainment (Diemer & Blustein 2006; Diemer & Hsieh 2008).

In South Africa, forms of critical pedagogy have generally emerged organically out of social and political struggles. In the 1980s, township schools became sites of political contestation and education became a space in which people fought for an alternative kind of society (Christie 1998). 'People's education' emerged as a movement, in opposition to the government's Christian National education paradigm (McKay & Romm 1992). These actions could be considered forms of critical pedagogy in action, using educational sites for societal transformation. Similar activities and sentiments have motivated recent educational movements in South Africa, such as the activities of the NGO Equal Education.

Youth Amplified did not involve young people trying to alleviate social problems through grassroots campaigns, research or a political movement. However, it did attempt to develop youth agency and voice, in a public forum. Moreover, the radical nature of the programme manifested in the kinds of public dialogues that emerged and were disseminated through live broadcasts that could be heard across a 50km radius of the city of Cape Town. Dialogues addressed inequality as it manifested in South Africa's political, educational and historical landscapes. The youth were held up as legitimate actors in socio-political dialogues, encouraging those participating, and their peers and teachers listening, to reflect on different perspectives and contribute to the discussions. Dialogue was therefore central to this form of critical pedagogy and to stimulating critical consciousness.

Learning through dialogue

Although young South Africans say they would like to participate in dialogues, few report regularly partaking in these kinds of interactions (Bray, Gooskins, Kahn, Moses & Seekings 2010; Ramphele 2002; Soudien 2007). Many students feel that teachers do not make sufficient space for question time and that teachers feel threatened by questions, inhibiting dialogue (Bray et al. 2010). This lack of dialogue may be linked to historical factors. During apartheid, poor schools were regularly the sites of conflict, as students, educators and school leadership fought over lines of authority, and political violence was often planned and carried out at schools (Christie 1998). The colonial heritage of many historically whites only schools produced strict authoritarian cultures. Youth Amplified provided educators and students with examples of educational dialogues, which they listened to live on air, illuminating an alternative to typically hierarchical, authoritative classroom interactions.

A dialogue, in this context, is a particular kind of conversation. It contains a range of unsynthesised opinions held together simultaneously, encouraging participants to compare and assess different perspectives and to develop their own positions (Wegerif 2011). Dialogic learning consists of groups of people sharing ideas, assessing their own perspectives and co-constructing forms of knowledge (Barnes 2008; Howe 2010; Wegerif 2011). Through being confronted with different ideas, people question their assumptions and opinions, enhancing critical consciousness. Dialogical forms of learning involve inter-subjective processes in which people collectively make meaning and learn from each other. People use language, concepts and ideas to engage with the perspectives of others and co-construct forms of knowledge in the process (Alexander 2008).

Dialogic learning is enhanced by internally persuasive discourse, rather than authoritative discourse (Bakhtin 1981). Bakhtin used the term 'discourse' to describe how sets of utterances interact, whether they 'invite a response', or if, alternatively, they present themselves as 'finished products'. Authoritative discourse demands acknowledgement and may be thought of as the unquestionable 'word of the father'. It manifests in 'tradition', the 'official line' or in the acknowledged truths of, for example, religion or science (Bakhtin 1981, 342-346).

On the other hand, internally persuasive discourse is pivotal for dialogic learning. It involves play, catalyses new and different words in a person's conceptual repertoire and is productive and imaginative (Bakhtin 1981). Through internally persuasive discourse a person learns to appropriate concepts and utterances introduced by others, incorporating them into their own repertoires through a process known as 'double-voicedness' (Bakhtin 1986). The words that are appropriated are always partly theirs and partly somebody else's, demonstrating the interactional nature of this form of learning. Internally persuasive words are therefore experimented with and moderately changed in orientation, as people envisage how these words, ideas and discourses might be used in their own formulations, through double-voicedness (Cooper 2013).

Internally persuasive discourse invites a range of perspectives, which is the most important factor for catalysing learning in classroom situations where young people work together towards a common goal (Howe 2010). Classroom dialogue programmes encourage students to take turns speaking, to listen to others, ask questions and give reasons for their opinions (Dawes, Mercer & Wegerif 2004; Mercer & Littleton 2007). A youth radio show is, potentially, an excellent informal learning context in which to research dialogic learning. The format of a talk radio show naturally contains many of the principles that are implemented in classroom-based dialogue programmes. Participants are forced to listen to one another, as interrupting others leads to the audience not being able to hear the discussion. Youth Amplified was hosted by one of the students, making the setting an unintimidating youth-led learning place. The hostess (one of the participants) initiated dialogues by asking questions that were generated by the entire group prior to the show. Questions force youth to reflect on and amend their perspectives and to try to find answers by using their own words to correspond to other people's ideas.

Youth Amplified therefore provided a fertile context in which to investigate how and whether forms of dialogic learning functioned in an out of school site. More generally, the radio show was used to research how dialogue and critical consciousness were promoted/hindered in an informal educational setting. The central research question was: How are dialogue and critical consciousness promoted and/or hindered by a group of young radio show participants? The purpose of researching the radio show was to observe whether an out of school space, one without the presence of teachers and which used a curriculum that directly confronted social justice related issues, could generate vigorous dialogue and lead to forms of learning. The show therefore constituted a case study of a form of critical pedagogy, in an out of school setting.

METHODS

Youth Amplified as a case study

A case study is a research method that seeks to provide information about a specific phenomenon, like an activity or group (Stake 2005). Youth Amplified was an intrinsic case study, chosen for its intrinsic value as an informal educational setting that produced dialogue amongst youth (Suryani 2013). The radio show was studied for exploratory and descriptive purposes, shedding light on an example of a critical pedagogy intervention, rather than to explain generalisable learning processes that apply across contexts (McCutcheon & Meredith 1993). The show was therefore used to build new theory regarding a radio show as an educational site.

The case study method promotes collecting rich data in an authentic setting, illuminating lived experience as it occurs in a social context. The live radio shows, which were used as the primary source of data, provided insight into genuine interactions between young people, in comparison to reported information that generally emerges from individual interviews. Case studies can be conducted without predetermined goals and hypotheses, allowing the researcher flexibility in developing a theory of the phenomenon being studied (Stake 2005). This method therefore seeks to document a deep understanding of a particular group or context, without necessarily aiming to make universal generalisations.

Participants

Four diverse schools with different histories, norms, values and linguistic practices participated in Youth Amplified. The schools involved shaped the interactions between students. One group of Youth Amplified participants attended a working-class, Afrikaans medium school formerly reserved for coloured1 children. Others came from a school formerly reserved for black African, isiXhosa speaking students. A third group attended the Cape Institute of Excellence (CIE)2. The Western Cape Education Department established the CIE in 2004 to enhance the academic development of gifted learners reared in the townships. The final participating school was a former Model C school3, which I will call Barry Hertzog High. This school was chosen because the radio station did not want the show to become a programme for poor and marginalised youth. In this paper I use the term 'elite' schools to describe the former Model C school and the Cape Institute of Excellence, because these institutions charged fees that were at least 15 times greater than the fees at the other two schools. Many of the learners at the CIE were supported with bursaries from a range of sources, including NGOs, the state and private donors.

The radio station requested that the school principals select participants. Approximately five to seven students from each school attended the show, with equal numbers of young men and women participating. All of the young people were in Grades 10-12 at their respective schools. Participants were never asked to classify themselves in terms of racial identifications. However, only one student identified herself as white, with most of the other participants describing themselves as black or coloured at some point in the programme. Schools were therefore involved in selecting participants, in liaising with the students and radio station staff regarding logistics and in helping to ensure that participants were transported to and from the radio station.

Data collection

The bulk of the data was collected through live radio shows and individual interviews with the participants, both of which were transcribed in full. During the 12-month period of research, 13 live shows took place. In terms of individual interviews, the author interviewed each of the regular participants (15 in all) at least once. Interviews lasted for between one and two hours and were recorded and transcribed in full. The interviews were semi-structured; the researcher followed an interview schedule, however, questions were asked and lines of conversation pursued which deviated from the interview schedule, but which were relevant to the research question (Kvale 1996). Almost all of the data described in the findings section is taken from live radio shows, as the focus of this paper is on dialogue and it was live on air, rather than in individual interviews, that most of the dialogue ensued between participants. Individual interviews provided a private space in which learners could voice their concerns about the programme and their peers, adding another level of insight to the dialogues that took place.

The morning preparation sessions were observed and also formed part of collected data. Typically, participants would be due to arrive at the radio station at nine o'clock in the morning. The fact that some of the young people had to travel for up to an hour, using public transportation, meant that the sessions usually began at around 10am. Logistical complications involved in learners from vastly different residential areas travelling to and from the show proved to be a serious problem for Youth Amplified and one that would need to be seriously thought through if this method was to be replicated. Once at the radio station, preparation for the show would begin with the group either watching a documentary, reading an article or preparing to interview a guest live on air. After watching or reading the materials participants were given time to write down five to ten questions each. The group would then share questions and discuss which questions were 'good' and which were not.

Prior to the show each participant would be armed with two or three good questions, which the hostess noted. Members of the group then proceeded with other tasks. Some individuals were responsible for music for the show, while others updated the Facebook page. Prior to the first show interested individuals auditioned for the role of host/hostess and a young woman from the former Model C school was chosen for the role by employees of the radio station, who assessed that this individual had the necessary competencies to hold the show together. The fact that this individual hosted the show may well have impacted on the findings; her role enabled the predominance of the institutional culture of the former Model C school at Youth Amplified. This has been taken into account in the analysis.

Research ethics

All of the participants and their parents signed informed consent forms prior to the young people participating in the programme. Through the informed consent document, and in the form of discussions, it was communicated to the young people that they could withdraw from the programme at any stage. Before the show commenced, and at regular intervals during the show, the facilitator initiated discussions in which the group reflected on the fact that the show was being broadcast to the public. During these discussions participants were encouraged to think about the fact that their inputs would be heard by others, including school teachers, parents and the wider public. The facilitator was experienced in working with young people and was alert to discussions and situations in which the youth may have exposed themselves, or become embroiled in conflict. This research project was approved by the Stellenbosch University ethics committee.

Data analysis

Individual interviews and live radio shows were transcribed in full. A thematic analysis was performed on the transcripts. Thematic analysis helped to identify and describe recurring codes or patterns in the data (Braun & Clarke 2006). Themes were generated deductively from the research question and from theory on dialogic learning and critical pedagogy. The analysis illuminated how different themes functioned in the data, how they related to one another and helped to address the specific research question regarding how dialogue and critical consciousness were promoted/hindered in an informal educational setting.

The observational data and field notes were then coded, pinpointing recurring themes. The coded transcripts were then triangulated with the other data sources. So, for example, if a theme was observed in live Youth Amplified shows, as well as in individual interviews and aspects of this theme were noticed and recorded in observations, it was identified as a prominent theme. Triangulation uses a range of different sources in order to clarify the meaning - and verify the importance - of concepts, opinions or actions displayed by participants (Stake 2005). It also helps to avoid misinterpretation. Triangulation was used in order to enhance the reliability of the Youth Amplified case study, adding rigour, which contributed to improving the 'quality of the craftsmanship' (Kvale 1995, 26).

My positionality as a white, middle-class, male, South African researcher, who attended a former Model C school, may well have influenced the themes that I have identified as pertinent ones. The crude and often matter of fact ways in which the young people spoke about race stood out for me, but seemed completely natural to many of the young participants. Similarly, being a product of a South African former Model C school, one that I have become increasingly critical of in hindsight, probably influenced my perceptions of the participants' schools. I have tried to remain cognisant of my positionality at all stages of the research, reflecting on how it shaped my decisions regarding methodology and how it influenced my interpretations of the findings.

FINDINGS

Introduction

I identified two main themes, 'school institutional culture' and 'race talk', from the data. These themes shaped dialogic learning and critical consciousness development at Youth Amplified. I first describe 'school institutional culture' and 'race talk' and then look at how these themes shaped dialogues.

'Like we're taught at our school, your success depends on your own hard work': School institutional culture

Participants represented their schools at the radio show, announcing the schools that they attended at the start of the programme. They were expected to behave in a manner that was deemed to be congruent with their respective schools' rules, codes of conduct and cultures, all of which impacted on dialogues. Students from the CIE described their school as an institution that promoted a culture of intense academic competition:

Greg: Everyone wants to be in the top 10 so the competitive drive pushes you and it actually makes more clever people.

Jake: The typical example with me, the first time I met Greg I greeted him but when I heard he wrote that essay and (when) he achieved...I changed my view on him. And I respected him.

Phumla: At school, I'm always in my own room studying. We all have to do hard work. To compete that's part of my dream. At school there's a lot of competition, we eat competition, we need competition.

Greg: and that's what competition is, it's a great motivation, a great motivation. (excerpt from a live show)

Student identity, respectability and academic achievement were enmeshed at this school, as learners' sense of self was formed and fuelled within a culture of competitive intellectualism. Prestige and admiration from peers was publically produced by regularly announcing the learners with the most excellent academic results, which formed an integral component of the school's culture.

Phumla said that the learners 'eat' and 'need' competition, indicating the all-encompassing nature of this culture, one that apparently nourished students. These learners generated a sense of identity by exerting academic superiority over others. The CIE encouraged students to attain excellent results, but it did not necessarily prepare them for dialogic forms of learning that favoured cooperation rather than competition.

The CIE's institutional culture and values displayed similarities with those of the current South African state. The CIE is a mathematics and science focus school, demonstrating common priorities with the South African state, which has named mathematics and science as key to economic development (Makholwa 2014). In the following quotation Themba expressed attitudes towards science and associated careers, opinions endorsed by his school's values:

Themba: If the majority aren't taught in language which they understand, how then are they supposed to excel? We need scientists, we need engineers and if you say something in a language they don't understand, you can't test them.

'Excelling' was understood as attaining good grades in Science and Mathematics, skills that may lead to careers like engineering that were perceived to benefit the South African state. The mechanism for judging whether excellence had been attained was testing. The state projects forms of its ideal citizenry through its schools (Soudien 2012). The CIE, a recently established, 'custom-made' school, demonstrated elements of the new South African state's 'ideal-type' of young South African. This was observed through an individualistic culture of competition that was assumed to benefit the individuals and the group, valuing forms of scientific knowledge and mathematics and constantly requiring individuals to account for their knowledge acquisition through regular tests. CIE learners transported these school values, culture and discourses to Youth Amplified.

The attitudes of students that attended the former Model C school resonated with some aspects of the CIE:

John (reading a Facebook message posted by a Barry Hertzog educator during the show): Mrs Small says 'history shows excellent examples of youth from poor environments succeeding and achieving. Take a moment to find the motivation and develop whole happy youth. Baby steps create change!'

And:

Mikaela: You can't go and miss a whole lot of classes and be successful. You have to put in the extra mile, like we are taught at our school, your success depends on your own work and effort and that's your responsibility.

Barry Hertzog learners also exuded a discourse of individualism and a belief that success was based on individual choice, perseverance and hard work. Educators and students perceived success as linked to individuals' hard work ethic and determination. However, in terms of subtle differences between the CIE and Barry Hertzog High, the latter's culture, values and norms appeared to be more congruent with its British colonial heritage:

John: .. .which is absurd to me coming from a school where uniform is of essence.

Bernadette: it's most important.

John: even though it is might be seen what has uniform got to do with you passing a test, it's about being part of a professional environment and when you feel like you're part of a school then you are there to learn and there to educate, then obviously that's when education and knowledge flourishes.

At Barry Hertzog, education, knowledge acquisition, personal appearance and schooling were linked to a form of conducting and presenting oneself that was based on a specific notion of respectability and conformity. Education and knowledge were associated with forms of behaviour and specific traditions that originated in the colonial period. As will become clear, these ideas and values functioned as unquestionable, authoritative truths that were difficult for participants to interrogate and question.

Race talk at Youth Amplified

'Race' stood out for me as a prominent theme at the radio show. It was a marker of social difference that participants used to make sense of peers and South African society. One participant from the former black African school remarked after watching the documentary Testing hope, a film which explored inequalities in the South African education system:

Phumi: We got to see how different the schools from different races are, black and white and all that.

The confusing phrase 'schools from different races' demonstrates how the youth racialised schools, making it almost seem natural that a school would 'have a race'. Learners from the two less well-resourced schools tended to assume that 'white schools' were inhabited exclusively by 'white children'. Shortly after the Barry Hertzog learners joined the group, one participant said that he was going to sit with the 'white children', despite only one of the five Barry Hertzog learners later classifying herself as white. The school that these learners attended, their language and style, in the form of clothing and sense of humour, were interpreted in racial terms. Participants therefore made assumptions about race that were often not questioned or interrogated dialogically. In response the facilitator questioned these kinds of comments and challenged participants' assumptions. He also organised a live show to interrogate the meaning of 'race and inequality'.

On other occasions participants used 'race talk' to question social hierarchies and inequalities:

Mo: The only reason the so called white children have jobs is that they don't have problems. They can only focus on their books. Not worry about food. School fees is paid. You just have to do the work. If everyone in South Africa have to pay the same money, from the doctor to the man in the street, everybody's life would have been nice and civilized. (individual interview)

Here race was linked to material inequalities and the distribution of resources. 'Race talk' therefore presented a fertile theme for exploring socio-political contexts in ways that were relevant to these young people. At the same time, specific ideas linked to race were often presented as common-sense truths. For example, a colonial discourse pertaining to 'civilisation' was utilised unreflexively above. What it means to be 'civilised' and why this is an ideal worth striving for were left unquestioned. The notion of 'standards', a concept that was bound up in racialised colonial discourses, was often used in a taken for granted manner, something which is apparent in the next section.

School institutional culture and race talk shaped dialogues at Youth Amplified

The two themes introduced above were integral to Youth Amplified dialogues and to shaping the young people's critical consciousness. Two examples are now described. The first is taken from a live discussion after participants viewed the documentary Testing hope, which explored inequalities in South African schooling:

Ariel: you can be light of complexion and people say 'she's not actually coloured cause look how she looks', so there's actually different standards of coloureds. I come from Strandfontein and if I step into Hanover Park people will say 'no she's not coloured' but I actually am because of my background.It's just the way you look after yourself.

Kelly (hostess): Mo what makes a person a coloured?

Mo: coloured, it's funful people.

Kelly: funfilled how?

Mo: like to make jokes, have fun, make a smile, even if there's no food in the house, there's a smile on your face cause we colourful people.

(approximately one minute later)

Themba: I spoke about apartheid and it's 17 years after that, why are we still looking at people in terms of colour, why aren't we all human?

Group: Mmm

Tracey: I think apartheid had a big role in this cause they made coloureds, so called coloureds and so called blacks feel inferior, they made us feel small as Letho said, they treated us that way, inferior, ja apartheid is gone we have democracy and everything and still you walking in the street, the so called white people, the so called more richer, more advanced people look down on us cause we were classed as coloureds and blacks, which I think is wrong, why say it's a free country, why say it's a coloured nation, free world, when we still get treated the way apartheid used to treat us?

Kelly: So we gonna bring it back to the reason we all here, how does this apply to education? Is this a democracy and how does that affect us as the youth?

Tracey: Coming back to what Themba and Ariel said, ja, people feel inferior and that's why I said so called whites and so called blacks and so called coloureds, we didn't class ourselves as whites and blacks and coloureds, we were called those by other people. I wasn't even alive when apartheid was there but still I'm suffering, we as the new generation we should find a way of changing it.

(approximately one minute later)

Themba: I don't let the colour of my skin define me, it plays a role in opportunities. At CIE the coloureds and blacks click together and we're all children of the CIE, we write the same papers, same teachers, marking criteria the same nothing different. But that's just to a certain individual. I think we should keep the racial classification thing for a government or a university to channel money to people previously disadvantaged. Cause look at the reality, people in Nyanga are suffering, coloured people are suffering they're not getting the same opportunities as the white people. So it's right to classify, but in terms of you yourself it doesn't make it right to classify. Am I making any sense?

(Data previously presented in Cooper 2013)

Participants asserted three different notions of coloured identity. Ariel contradictorily dismissed that she considered herself superior to families in a working-class neighbourhood, while stating that there are 'different standards of coloureds'. These 'standards' were, in her view, related to the fact that some people, like herself, 'take care of themselves'. Ariel described interactions with people from a working-class neighbourhood, Hanover Park, one that is similar to the area where Mo lived -exchanges in which she felt judged for apparently attempting to attain an illegitimate, elevated status. Ariel utilised a discourse of 'standards', one that circulated at her school in relation to perceptions of the quality of education, behaviour of students and the kinds of learners that were welcome at the school. Here Ariel used 'standards' to speak about race, which functioned to inhibit dialogue, as it was insulting to working-class coloured students to be informed that 'different standards of coloureds' exist. Mo reverted to the caricatured stereotype of coloured as carefree and humorous, describing coloured people as 'funfilled and colourful'. This strategy was a form of conflict aversion; he did not want to argue or be exposed as inferior, especially live on air, in English.

By contrast, Tracey disentangled race-based self-classification from imposed forms of racial categorisation. She linked race to history, in the form of apartheid, and through the repetitive use of the term 'so called' differentiated between labelling as a way of socially constructing different groups and racial identity as an internalised, subjective process (Cooper 2013). Double-voicedness was apparent in Tracey's speech, as she used 'so called' to demonstrate that she had thought about this form of labelling and incorporated it into her own perspective. The words 'so called' demonstrated different voices informing Tracey's thinking, illuminating how she had understood race as historically contingent.

Through conceptual engagement and personal reflection, Tracey placed herself in a historical perspective, deconstructed the process of racial classification and was critical of her society. Her internal dialogue was apparent in the range of terms she used and with which she struggled to make sense of her thoughts. The dialogic learning process was therefore observed through double-voicedness, as some students assimilated concepts and ideas from others, incorporating them into their own repertoires.

Another indication that dialogic learning occurred was evident on the three occasions when participants named peers' contributions, indicating that they had heard these opinions, pondered their relevance and considered integrating them with their own opinions. However, there was an even more unambiguous indicator that dialogic learning occurred in the interaction between Themba and Tracey. Dialogic learning is demonstrated through a change of position, as a person considers other perspectives and then amends their original position. Themba, a CIE student, originally stated that it had been 17 years since the demise of apartheid and that people continue to think in racial terms, when they should perceive each other simply as 'human'. Tracey's position on racial construction catalysed him to modify his argument. This culminated in a more nuanced stance on the difference between using historical categories for redress in policy decisions, versus individual racial classification at schools. In light of other perspectives, Themba developed his position to form a more complex, context-specific set of opinions. Together Tracey and Themba were able to exchange ideas, build upon one another's perspectives and co-construct knowledge. In the earlier, defensive interaction between Ariel and Mo, neither young person engaged with the perspective of the other, as they simply proceeded with their own line of thought.

An intense dialogue occurred after watching Afrikaaps, a documentary based on the possibility of introducing informal, Cape Flats Afrikaans as a medium of instruction at schools. Learners from the working-class Afrikaans school primarily used Afrikaaps outside of their school, unlike the Barry Hertzog learners and the CIE students, who used this vernacular sporadically. Students from the fourth school spoke isiXhosa at home. Racial identities and school institutional culture were again core components of this heated debate:

Greg: You people in support of Afrikaaps, take you, you do Afrikaans at school right, that's your medium of. .so you say that you understand Afrikaaps and that at school you do Afrikaans and so that's a problem for you cause you have to come and do your subjects in that language, so you sitting with a problem. So here's the solution then, eradicate Afrikaaps, do the formal Afrikaans as it should be, then you won't have a problem at school.

ALL TALK AT ONCE

Tracey: Why don't the teachers come down to my level? Greg: No, it's not supposed to be like that.

Tracey: Why don't teachers come, okay they don't even have to come to my level, why don't they just find a slight way of changing how they explain things?

Greg: That's the problem, you want to lower the standards, the standard has been set and now we want to lower it, it's wrong.

Tracey: Slow and steady wins the race.

Greg: Slow and steady might win the race but with this education system we're in now is it time to be slow and steady?

Tracey: The thing is we are being taught, we have to learn to get to those standards. So they have to come to our standards to bring us up.

Greg: Afrikaans is the formal language, it's the legal language, it has its own set of grammar and everything of how it should be spoken, now suddenly you want to come and say 'no it's a bit too difficult, I understand it better let's make it that way'.

Tracey: It's not that we want the language itself to change, but if the teacher finds a easier way of explaining, then we might learn the language better don't you think? Take Maths for instance, your Maths teacher always finds some way for the slower child to catch up. So why can't your language teacher do that? What's so wrong with that? How can we get to that level if we don't really understand?

Greg: So you saying the teacher should use some of your language in between?

Tracey: .. .and then give us the real meaning afterwards. Don't you think?

Greg: but then that's just gonna, that's just gonna.. .prolong things. You can, you just need to start reading.baby Afrikaans.

(A short while later)

Mo: My History teacher says you coloureds are nothing. I ask him now what are you, you also a coloured, then he say ja. I'm just standing up for my rights.. .He think he something better. You a coloured you running away in your heart you're actually a coloured. A coloured's a funful person, likes to make jokes.

Greg: well if I'm not a.then am I not a coloured? I'm a very very serious person.

Themba: I think Greg has spent far too much time at school that has forced him to abandon his colouredness.

Greg stated that students who conversed in Afrikaaps needed to elevate their linguistic abilities or 'raise their standards' and become fluent in formal Afrikaans. He believed that students who spoke local varieties of Afrikaans should learn and speak standard Afrikaans at school. He implied that hard work, perseverance and confidence were the only barriers to individual success, using phrases such as 'winning the race' and 'not prolonging things'. These concepts corroborated the prominent values of competition, success and individualism of the CIE. Once Greg introduced this discourse of 'standards', others complied with the normative meaning of these 'standards', only contesting the manner in which their own 'standards' could be raised. Students did not interrogate the criteria for 'high standards', instead, they debated whether the school system and educators should accommodate these students and their apparently 'sub-standard' linguistic capital.

Tracey argued that students could effectively raise their standards with educators' support, encouraging teachers to 'descend' to the students' level. When Tracey referred to the 'real meaning', she implied that the language which she used was not real, insinuating that it was inauthentic and invalid.

Students were insulted by Greg's reference to the inferiority of their language. Some participants retaliated, stating that he had abandoned his race. Mo's reference to his History teacher was allegorically directed at Greg, who was accused of behaving in an illegitimate manner, based on his perspective on Afrikaaps and his educational aspirations. Instead of critiquing the composition of these supposed standards, some participants personally attacked Greg. After the Afrikaaps discussion Greg sheepishly approached the facilitator, saying that he 'was not trying to be something which he is not'. The Afrikaaps dialogue led to Greg feeling illegitimate and unwelcome at Youth Amplified and he withdrew from further participation.

DISCUSSION

Critical consciousness development and robust dialogue at Youth Amplified were influenced by the norms, values and discourses of participating schools, as well as the radio station, which shaped the materials and the hostess that were chosen for the show. The powerful school institutional cultures of the two elite schools supported authoritative, colonial and apartheid era ideas that denigrated marginalised youth and perpetuated values of competition and individualism. These ideas that circulated at the elite schools were presented by students as authoritative or uncontestable truths regarding success, justice and learning, militating against critical consciousness development and dialogues that contained a range of contrasting opinions.

Authoritative ideas from the elite schools often crystallised around the notion of 'standards'. Research shows that the need to 'maintain standards' is propagated by a new multi-racial class coalition that has formed at former Model C schools in the democratic period, functioning to exclude marginalised families and maintain high levels of inequality (Soudien 2012). This newly formed power block disseminates notions of 'good schooling, quality and the maintenance of standards' (Dolby 2002; Soudien 2012). At these schools the discourse of 'standards' often manifests in relation to sport, for example rugby, and dress codes. Wearing school uniforms 'properly' supposedly demonstrates respectability and that 'standards are being upheld' (Dolby 2002). In her research Dolby (2002) linked these 'standards' to representations of whiteness and Europe, as school leadership, in her research site, sought to distance itself from associations with Africa.

The discourse of 'standards' is often used by middle-class parents to set school fee policies that exclude low-income children. It also demonstrates that the ideals and practices to which school communities are committed are far stronger at former white schools in South Africa (Soudien 2007). At Youth Amplified, the institutional cultures of the former black African and coloured Afrikaans schools were largely absent; prominent discourses and values that operated at those schools were rarely transported to the radio show and reproduced by participants. One of the consequences of the values and discourses of the elite institutions dominating the Youth Amplified radio show was that dialogue and critical thinking were inhibited, as the group was coerced to accept colonial and apartheid era ideas pertaining to, for example, 'standards'. While it may be considered a weakness of the method to make inferences about these schools' institutional cultures without collecting data at the schools themselves, other research at similar Model C schools has confirmed the existence of colonial era discourses related to 'standards' (see for example Dolby 2002 and Soudien 2012).

'Race' was a highly generative and contentious topic. It functioned as a master trope that signified social difference and status amongst young South Africans. Youth Amplified confirmed that 'race' does not operate in a fixed manner in the talk of young people, simply inherited and reproduced in the same form in which it existed during apartheid (Cooper 2013). Dolby's (2001) research illustrated how race, as it was understood by the apartheid state as a set of biological, cultural and historical factors, has been redefined by globalised, post-apartheid youth. The current generation of young people construct racialised identities in relation to choices, styles and tastes (Dolby 2001). Similarly, Bray et al. (2010) state that 'colour' may not refer to the hue of a person's skin, but may symbolise style and aspects of youth culture in post-apartheid South Africa.

Youth Amplified confirmed these findings on youth and race in post-apartheid South Africa. However, the show also demonstrated how students used 'race talk' to assign value to particular groups. Racial identifications do not only function to designate different styles and tastes, but they are potent political practices that can serve to exclude or denigrate groups of people. Alternatively, 'race talk' may also be used for emancipatory purposes, for example through historicising racial categories.

Pervasive race and class based inequalities, and other historically contingent power relations, meant that Youth Amplified participants needed to reflect on their perspectives, if conflict was to be avoided and educational dialogues produced. This demonstrated an interesting difference between what researchers perceive as ideal classroom dialogue (see for example Mercer 2005; Mercer & Littleton 2007; Rojas-Drummond & Mercer 2004) and what Youth Amplified highlighted as promoting dialogue in an informal educational context that dealt with social justice related issues. Dialogue can be most useful for classroom learning when young people conduct 'exploratory talk', reaching consensus, rationally, through groups pinpointing the 'best ideas'. Personal identities and other factors that may hamper the operations of 'rationalism' are therefore suspended and discouraged from playing a part in such discussions (Mercer 2005). However, when young people debate issues of intense personal and social relevance and pertinent historical power relations are at play, consensus and rationalism are often neither possible nor desirable. When young people engage with issues related to notions of social justice, different perspectives are contingent on the identities of the speakers and the historical position of particular groups. These identities and positions need to become conscious and integral components of dialogues, otherwise a range of underlying issues, related to, for example, race, class and gender, will impact, unconsciously, on the ensuing dialogues and possibly lead to conflict.

Dialogue in this situation does not simply involve the most rationally sound argument 'winning', but requires that people interpret different standpoints in relation to the social identities of the speakers. Whilst scholars that advocate for exploratory talk propose that rational debate and decision-making amongst equal parties benefit 'the common good', different groups of people have had a variety of historical experiences and have not previously had equal access to 'the common good'. Critical pedagogy as an approach to learning may therefore promote historical consciousness and social reflexivity, leading to a speech genre that is 'critical' in its orientation and not merely 'rational'.

Language use at Youth Amplified shaped interactions between participants in a number of important ways. The show took place in English, because it was the only language with which all of the learners were familiar. The use of English intimidated students from the former black African school and the coloured Afrikaans school, observed in, particularly, students from the former black African school often being silenced. While students were encouraged to speak in whatever language they were most comfortable, the use of a language other than English was rare. The issue of language is an immense challenge for critical pedagogy interventions like Youth Amplified, as language is imbued with forms of power related to race, class, gender and neighbourhood affiliations. South Africa has 11 national languages, complicating programmes that use dialogue for learning. Exploring these issues directly, in the form of live shows on the topic of Kaapse Afrikaans, helped to deal with this challenge and two learners started speaking in their mother tongue after watching the film Afrikaaps. The group bonding, over time, and individuals becoming more comfortable on air after participating in the radio show for a number of months, also helped to deal with the language issue, which remained a considerable challenge.

As the group spent time together and became more familiar with one another, participants from all of the schools gradually became more comfortable contributing to dialogues. Learners found different tasks that they could use to support the group, such as preparing music playlists and producing a Facebook page. Cooperating for the purpose of producing a show which all of the students' families, friends and teachers could listen to, functioned to promote dialogue. The use of stimulating materials and question generation prior to the live shows were also invaluable tools that aided in catalysing dialogic interactions.

CONCLUSION

As an informal learning space that used a form of critical pedagogy to stimulate dialogue and develop critical consciousness, Youth Amplified generated two pertinent insights. First, when youth represent elite South African schools in informal educational contexts, the discourses and values of these institutions are often transported with the students into new places of learning. At Youth Amplified these discourses and values inhibited dialogue and critical consciousness development. Critical pedagogy programmes therefore need to work with educators, students and possibly whole schools, if they are to achieve their objectives. Education will not succeed as a solution to structural inequalities if 'our best schools' teach their students that the poor simply need to try harder and that marginalisation is the result of a lack of individual effort. Elite schools are often least successful at respecting and promoting diversity and critically reflecting on privilege.

Second, young South Africans want to speak about racialised and class-based forms of historical oppression, a topic which the South African state, with schools as their primary form of socialisation, avoids in any meaningful form. The university protests that swept across the country in 2015 attest to this claim. These kinds of conversations require skilled facilitation that is able to encourage a diversity of opinions, whilst alerting participants, or students, to the historical contexts in which the dialogue plays out and the ways in which different groups of people have been treated by each other in the past. This kind of facilitation should also seek to illustrate that the existence of different opinions is not necessarily threatening and can be interpreted positively, as it can stimulate discussion. Rather than personally attacking an individual who makes a comment deemed to be offensive, young people like Greg could be challenged to reflect on their perspectives through others contributing conflicting views. Promoting these kinds of dialogues is difficult in a society that is obsessed with success, competition and demonstrating superiority.

Informal educational spaces, like a youth radio show, therefore hold unique potential to work with students and educators to explore important topics omitted by the school curriculum. These kinds of spaces may utilise forms of dialogue, generating insights that offer alternatives to classroom-based learning and developing citizens that are committed to struggling for social justice.

REFERENCES

Alexander, R. 2008. Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk. York: Dialogos. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. 1981. The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M.M. Bakhtin. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. 1986. Speech genres and other late essays. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Barnes, D. 2008. Exploratory talk for learning. In Exploring talk in school. Edited by N. Mercer and S. Hodgkinson, 1-17. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Bloch, G. 2009. The toxic mix: What's wrong with South Africa's schools and how to fix it. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Braun, V. and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77-101. [ Links ]

Bray, R., I. Gooskins, L. Kahn, S. Moses and J. Seekings. 2010. Growing up in the new South Africa: Childhood and adolescence in post-apartheid Cape Town. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Cammarota, J. and A. Romero. 2006. A critically compassionate pedagogy for Latino youth. Latino Studies 4(3): 305-312. [ Links ]

Christie, P. 1998. Schools as (dis)organisations: The 'breakdown of the culture of learning and teaching' in South African schools. Cambridge Journal of Education 28: 283-300. [ Links ]

Cooper, A. 2013. 'Youth Amplified': Space, dialogue and learning in an informal, out-of-school place. Unpublished paper presented at the 16th International Conference on Critical Thinking, Enquiry Based Learning and Philosophy with Children, 30 August-2 September 2013, University of Cape Town.

Dawes, L., N. Mercer and R. Wegerif. 2004. Thinking together: A programme of activities for developing speaking, listening and thinking skills. Birmingham: Imaginative Minds. [ Links ]

Diemer, M.A. and D.L. Blustein. 2006. Critical consciousness and career development among urban youth. Journal of Vocational Behavior 68(2): 220-232. [ Links ]

Diemer, M.A. and C. Hsieh. 2008. Sociopolitical development and vocational expectations among lower socioeconomic status adolescents of color. Career Development Quarterly 56(3): 257-267. [ Links ]

Dolby, N. 2001. Constructing race: Youth identity and popular culture in South Africa. Albany: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Dolby, N. 2002. Making white: Constructing race in a South African high school. Curriculum Inquiry 32(1): 7-29. [ Links ]

Duncan-Andrade, J. and E. Morrell. 2008. The art of critical pedagogy: Possibilities for moving from theory to practice in urban schools. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Erasmus, Z. 2001. Introduction: Re-imagining coloured identities in post-apartheid South Africa. In Coloured by history, shaped by place: New perspectives on coloured identities in Cape Town. Edited by Z. Erasmus, 13-28. Cape Town: Kwela Books. [ Links ]

Fleisch, B. 2008. Primary education in crisis: Why South African schoolchildren underachieve in reading and mathematics. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum International Publishing. [ Links ]

Giroux, H. 2007. Introduction: Democracy, education and the politics of critical pedagogy. In Critical pedagogy: Where are we now? Edited by P. McLaren and J. Kincheloe, 1-5. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Howe, C. 2010. Peer dialogue and cognitive development: A two-way relationship? In Educational dialogues: Understanding and promoting productive interaction. Edited by K. Littleton and C. Howe, 32-47. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kvale, S. 1995. The social construction of validity. Qualitative Inquiry 1(1): 19-40. [ Links ]

Kvale, S. 1996. InterViews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Makholwa, A. 2014. China to help SA improve maths, science results. BDLive, March 3. Retrieved from: http://www.bdlive.co.za/national/education/2014/03/03/china-to-help-sa-improve-maths-science-results (accessed 26 February 2014).

McKay, V. and N. Romm. 1992. People's education in theoretical perspective: Towards the development of a critical humanist approach. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

McCutcheon, D. and J. Meredith. 1993. Conducting case study research in operations management. Journal of Operations Management 11: 239-256. [ Links ]

Mercer, N. 2005. Sociocultural discourse analysis: Analysing classroom talk as a social mode of thinking. Journal of Applied Linguistics 1(2): 137-168. [ Links ]

Mercer, N. and K. Littleton. 2007. Dialogue and the development of children's thinking: A sociocultural approach. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ramphele, M. 2002. Steering by the stars: Being young in South Africa. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Rojas-Drummond, S. and N. Mercer. 2004. Scaffolding the development of effective collaboration and learning. International Journal of Educational Research 39(1): 99-111. [ Links ]

Sayed, Y. 1999. Discourses of the policy of educational decentralisation in South Africa since 1994: An examination of the South African Schools Act. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 29(2): 141-152. [ Links ]

Soudien, C. 2007. Schooling, culture and the making of youth identity in contemporary South Africa. Cape Town: David Phillip. [ Links ]

Soudien. C. 2012. Realising the dream: Unlearning the logic of race in the South African school. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Stake R. 2005. Qualitative case studies. In The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd edition. Edited by N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, 443-466. Thousand Oaks/London/New Delhi: SAGE. [ Links ]

Suryani, A. 2013. Comparing case study and ethnography as qualitative research approaches. Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi 5(1): 117-127. [ Links ]

Taylor, N., J. Muller and P. Vinjevold, 2003. Getting schools working: Research and systemic school reform in South Africa. Cape Town: Pearson South Africa. [ Links ]

Van der Berg, S. 2008. How effective are poor schools? Poverty and educational outcomes in South Africa. Studies in Educational Evaluation 34(3):145-154. [ Links ]

Wegerif, R. 2011. From dialectic to dialogic. In Theories of Learning and Studies of Instructional Practice. Edited by T. Koschmann, 201-221. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

1 I use the term 'coloured' as, following Erasmus (2001, 21): 'identities formed in the colonial encounter between colonists (Dutch and British), slaves from East and South India and from East Africa and conquered indigenous peoples, the Khoi and the San. The result has been a highly specific and recognisable cultural formation, a very particular mixture.

2 All of the names of schools and students are pseudonyms.

3 In the final years of the apartheid era, parents at white government schools were permitted to convert their governance structure to a semi-private form called Model C, and many of these schools changed their admission policies to accept children of other races. These schools could also establish school fee policies (Sayed 1999). The term continues to be used in public discourse to describe government schools formerly reserved for white children.