Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 n.2 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/756

ARTICLES

Using conflict mapping to foster peace-related learning and change in schools

Vaughn M. John

University of KwaZulu-Natal Email: JohnV@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

South African societies, including learners in primary and secondary schools, experience high levels of violent conflict. The lack of interventions in terms of peace education and peace building is cause for concern. Driven by an interest to build educators' capacity and agency to become agents of change in the face of growing conflict and violence, this article discusses a mapping project which gets educators to explore their schools using a participatory process and to plan appropriate interventions in response. It considers how Freirian-inspired critical reflection and dialogical learning can be used to stimulate peace education and peace building in schools.

Keywords: conflict mapping; peace education; peace action; critical reflection; dialogue

INTRODUCTION

Media reports regularly present South African schools as violent and sometimes deadly sites. National surveys convey a more comprehensive picture but raise similar alarm (Leoschut 2009; Burton & Leoschut 2013). Both sources portray a sense of teaching and learning under siege! The regularity and prevalence of violent conflict in schools mirror that of broader society (Institute for Security Studies 2014). With inadequate support and few intervention strategies, key stakeholders within the school often feel disempowered and helpless. For educators, the scale, pervasiveness and danger of such conflict can lead to desensitisation, apathy and subdued agency. How can teachers' capacity and agency to intervene within their school be increased? How can teachers be supported to become agents of change in the face of growing conflict and violence? These questions have provoked some curriculum experimentation and research, in the form of a conflict mapping project, within a peace education module at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN).

This article discusses an attempt to get educators to explore conflict, violence and injustice in their schools using a participatory mapping project and to plan appropriate interventions in response. It first describes the social and institutional contexts of the mapping projects, then sets out the different stages of the mapping project and the key pedagogical considerations underpinning each stage. In particular, it considers how Freirian-inspired critical reflection and dialogical learning can be used to stimulate educator-led peace education and peace building in schools. The article draws on data generated with school educators between 2010 and 2013. A final section of the article presents my own and participants' reflections on the mapping projects and their potential as catalysts for transformation in schools.

Postma (2014, 4), in a recent editorial reflecting the new emphasis of this journal, refers to the transformative power of educational research;

The transformative power of educational research draws the insight from Hacking (1983) that science does not simply represent reality, but it always intervenes in what it investigates - it does not leave the object of investigation intact. Research itself is a practice that changes the world it investigates and this change should also be seen in a normative way as addressing issues of equality and transformation.

In several ways the research presented in this article reflects the epistemology set out by Postma in the above quotation, in advancing a form of participatory research for educational transformation. The mapping projects at the centre of this article seek not only to move beyond simple representations of the reality of the school but to foster critical reflection and dialogue on this reality in order that actions to change such a reality become more visible and possible.

In order to understand the genesis and purpose of the conflict mapping projects, it is first necessary briefly to review the South African context in which teaching and learning takes place and which gives rise to the need for peace education and other interventions. This is followed by a brief description of the UKZN peace education course within which the mapping projects became a major pedagogical tool and catalyst for dialogue, reflection and change. The article draws on relevant literature and engages with reflections and feedback provided to students on their projects.

TEACHING AND LEARNING IN A CONTEXT OF ENDEMIC VIOLENCE CONFLICT

Conflict and crime in South Africa are characterised by extreme violence. No part of the society is untouched by this problem which has its roots in long histories of violent conquest, domination and struggle. The notion of a culture of violence today aptly conveys the persistence, extent and prevalence of violence in South Africa.

The Schools Violence Study reported alarming rates of violent conflict in schools across South Africa. This independent survey (Burton & Leoschut 2013) sampled 5939 pupils, 121 principals and 239 teachers and conveys the scale and spread of such incidents, as well as the trends when compared with results of a previous survey conducted in 2008 (Leoschut 2009). The latest survey found that 22.2% of high school pupils nationally reported being threatened with violence or having been victims of assault, robbery and/or sexual assault at their school in the preceding twelve months (Burton & Leoschut 2013). The figures show increased rates for KwaZulu-Natal with pupils assaults at 8.2 % (up from 3.7% in 2008), sexual assault at 3.9% and theft from pupils at a staggering 49.9%.

Not surprising, such trends match those of community-wide crime and violence. The latest official crime report shows that 17,068 people were murdered in the country in 2013 (a 5% increase), translating to an average of 47 people being killed each day (Institute for Security Studies 2014). South Africa has extremely high levels of gender-based violence too. A woman is killed by an intimate partner every 8 hours in South Africa (Abrahams et al. 2012). Burton (2008, 1) notes that violence makes schools 'a place where children learn fear and distrust, where they develop distorted perceptions of identity, self and worth, and where they acquire negative social capital'. Leoschut (2006, 6) likewise warns that '[c]hildren exposed to chronic community violence may begin to feel that they have no place in which they can feel safe'. When communities are this unsafe, there is additional importance in ensuring that schools become safe havens and places where children can engage in peace education and peace building.

Advanced inequality and deprivation in South Africa must also be seen as part of the systemic and structural violence. Clearly, despite its relatively peaceful and much-celebrated transition from apartheid to democracy, South Africa is by no means a peaceful country. One indicator of this is its continual low rank on the Global Peace Index, a broad-based measure of peace. In 2015, SA was ranked 136th out of 162 countries on this index (Institute for Economics and Peace 2015). There is no universally accepted definition of peace and much research exists on how it has been variably understood (Galtung 1969; Sandy & Perkins 2002). For the purposes of this article, an expanded conception of peace, as conveyed in the concepts of positive peace (Galtung 1969) and just peace (Lederach 2005) is adopted. This is an understanding of peace that entails more than the absence of violence and war, one where the basic needs of all people are met and there is a respectful and sustainable coexistence between all people and life forms. Critically, this is a form of peace that is inextricably tied to justice. Peace education then, is a wide range of educational interventions and actions, in both formal and non-formal contexts, which seek to build such a just and positive peace. Freirian-inspired education, using critical reflection and dialogical learning to foster greater freedom from oppression, justice and humanisation, is also premised on ideas of positive, just and sustainable peace. Freire (1970, 18) warned that under oppressive conditions a culture of silence breeds 'the absence of doubt' which imprisons the mind to such an extent that people fail to see and question their oppression and dispossession. The mapping project explored in this article stimulates critical reflection and dialogical learning that can counter silence and 'the absence of doubt' regarding oppression and injustice in schools.

While survey data is important for a sense of the extent of the problems and trends over time, in-depth understandings of the nature, underlying causes, and consequences of school-based conflict are also required. Exploring educators' experiences and understandings of school-based conflict, violence and injustice, as discussed in this article, addresses this need. Such in-depth research complements survey findings and can aid the development of intervention strategies. When teachers and learners, as key stakeholders, participate in generating contextualised understandings of conflict, violence and injustice, more locally-appropriate interventions can be planned. This article discusses a process and pedagogy for doing this.

In a context of such violent conflict, the dearth of interventions in terms of peace education, peace action and peace building more generally, is both surprising and tragic. The Department of Education has inadequate plans and capacity to intervene and offers little direction and support to schools. Unlike many countries, South Africa does not include peace education within its formal curricula. Furthermore, while school safety policies may exits, these are very often not implemented (Xaba 2006). A small number of NGOs offer some intervention programmes but without any meaningful reach and regularity (John 2013).

The above brief review illustrates the context of crisis in South Africa where violence is endemic, destabilising schools and society and the source ofmuch physical and emotional harm to learners and educators, and society in general. Equally clear is the inability of schools to cope, the lack of peace education and inadequacy of suitable interventions. For educators to intervene, they need to be exposed to peace education and peace action curricula and programmes, together with simple data gathering techniques, conflict analysis skills and to be supported in critical reflection and dialogic learning. Zikode (2011, vii) reminds us of the important lesson drawn from Frantz Fanon that 'we have to keep thinking and discussing even in the middle of a crisis'. This article discusses a mapping project which aimed to get educators thinking and discussing in the midst of crises in their schools.

CONFLICT MAPPING IN A MASTER'S-LEVEL PEACE EDUCATION COURSE

The master's programme in Social Justice Education at UKZN has since 2008 included a course called Peace Education and Conflict Resolution. This article draws on experiences of three cohorts who participated in this course between 2010 and 2013. The students in the programme were predominantly school educators and principals. The course aimed to introduce these students to an aspect of social justice education broadly referred to as Peace Education.

A key objective of the course was to introduce students to peace literature, theory and practices as a way of enabling them to introduce peace education in their schools and to consider peace action and peace-related research as possible routes to intervening in their schools. It thus carried a dual focus on theory and practice throughout. Students were introduced to the work of peace theorists such as Johan Galtung, Betty Reardon, Ian Harris, Gene Sharpe, Wangari Maathai, the work of several local conflict and peace researchers such as Collins (2013), Leoschut (2009; 2006), Xaba (2006), and Burton (2008) and to practical peace programmes and interventions such as that of the Alternatives to Violence Project (2002) and Peace Clubs (Mennonite Central Committee 2012). Using a variety of methods and participatory pedagogy the course attempted to get students to think deeply and critically about conflict, violence and injustice in schools and society, and to consider what interventions were possible. It engages with broader conceptions of violence beyond physical violence (and war) to consider structural violence such as poverty and patriarchy, where the agents or perpetrators are less visible and are part of systems and structures in society (Galtung 1969). The mapping projects discussed in this article therefore maintain a distinction between conflict and violence. It furthermore includes a separate category of injustice to sensitise educators to the broader concept of social justice, for example when school environments do not cater for disabled persons or when teachers' facilities at a school are better than those provided for learners. The notion of justice also allows for critical consideration of how dominant cultures and educational systems determine what is taught, how it is taught and for what purposes. Theorists like Freire (1970) and Kelly (1986) remind us of the dangers of school systems and curricula that alienate learners and foster authoritarianism because of their ideologies of expert teachers, certainty of knowledge and the one right answer. In response to the question of why schools cannot protect young people from violence but rather perpetuate violence, Harber and Sakade (2009, 172) note that 'the overwhelming evidence is that the dominant or hegemonic model [of schooling] globally, with some exceptions, is authoritarian rather than democratic'. Furthermore, in South Africa, there are complex relationships between poverty and education. We are more likely to consider how poverty negatively affects education. However, Spaull (2015, 34) also shows how the 'poor quality of education that learners receive helps drive an intergenerational cycle of poverty where children inherit the social standing of their parents or caregivers, irrespective of their own abilities or effort'. This is an aspect of injustice that is important for educators to consider as it could challenge them more directly in terms of how they may be implicated in cycles of poor education and poverty.

Despite these efforts to combine theory and practice and to get students to apply what they had gathered from the literature and class sessions to their specific contexts, the initial summative assessments revealed that students struggled to contextualise and apply what they had learnt. Despite the assessment tasks inviting students to refer to 'preliminary research you have conducted', very few based their papers on such research. This challenge led to the design of a new assessment task which would address the above concerns. The idea of getting students to carry out small-scale research and analysis which would detect real issues of conflict and violence gave birth to the conflict mapping project.

MULTI-STEP CONFLICT MAPPING

Developed and refined over different cohorts, the mapping project eventually took the following form:

-

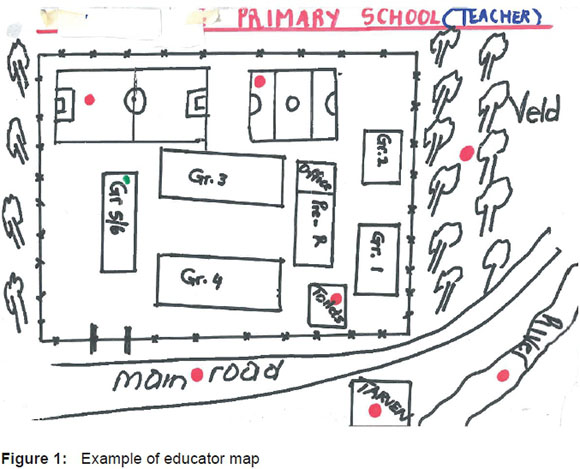

Step 1 Educator map of school environment. Students were asked to draw a map of their school and to identify places on the map that were sites of conflict, violence or injustice. In class students put the maps up on the wall and presented them to class, leading to discussions on conflict, violence and injustice in KZN schools.

-

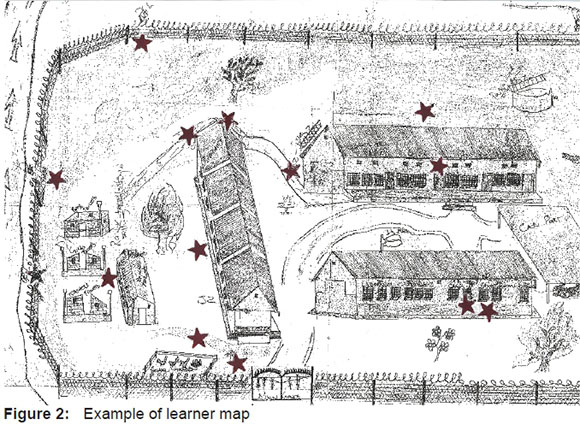

Step 2 Learner map of school environment. Students were then asked to use a suitable lesson in their schools to get their learners to draw maps identifying conflict, violence and injustice in their schools. To allow for an analysis of the gendered nature of such experiences and perspectives, learners were required to create maps in groups of males and females separately. Such map-drawing was followed by discussions in school where each group would present their map and identify and discuss sites of conflict and violence. The teachers were then asked to bring these maps and a summary of the post-mapping discussions to our class for further discussion.

-

Step 3 Comparisons of maps and critical reflections. Students were asked to reflect on and discuss the differences and similarities between the maps in terms of gender dynamics. Likewise, they were asked to reflect on and discuss the differences and similarities between learner maps and the educator map. This step of the task prompted deeper critical reflections and comparisons. Students were asked to consider how socialisation, oppression and different aspects of their identity such as gender, age, context, religion, culture etcetera shape their understanding of conflict, violence and injustice.

-

Step 4 Planning an intervention. Students were asked to select a key example of conflict, violence or injustice identified by their learners and to plan an intervention related to this problem in their school. The intervention allowed options for peace education and peace action. Detailed guidelines on different aspects of the interventions and for engagement with the literature were provided as follows:

If you are proposing some peace education you should discuss:

What is peace education?

What peace issues are addressed by the curriculum? Justify your choice in terms of the conflict mapping exercises. You must refer to mapping research you have conducted in your school and to research literature.

What methodological and pedagogical approaches would you recommend?

How would the curriculum relate to the broader school curriculum?

Provide a sample of a detailed lesson plan which would exemplify the above choices. Draw on relevant literature and go beyond literature provided in class.

If you are proposing some peace action you should discuss:

The chosen problem currently affecting your school (or community). You must refer to preliminary research you have conducted and to research literature.

Plan a programme of peace action which you believe could be a worthwhile intervention to address the problem.

With reference to Sharp's (2003) list of peace actions, indicate which of these amongst others you would include in your plan and why.

Provide a detailed table that lists the peace activities, sequence of events, people involved and desired outcomes for each activity. Justify your choices with reference to your preliminary research. Discuss the learning that such peace action could generate for all participants involved.

-

Step 5 Presentation of seminar and maps in class. Students were asked to put all of the above into a seminar paper and to present this to the class during the final session. This mini-conference allowed for dialogue, joint critical reflection and critique, and learning and teaching each other, as discussed further below.

-

Step 6 Submission of final seminar paper. Students were allowed to revise their seminar papers based on the feedback received from the presentation and to submit a final paper for assessment. This final submission also allowed for further feedback and suggestions and encouragement for implementation of intervention plans.

METHODOLOGY

Given the wealth of data generated by the mapping projects and the rich experiences it generated, a research study on the mapping projects was designed. The study of these conflict maps, related processes and experiences, entitled 'Exploring educators' understandings of conflict, violence and injustice and how they may intervene', was granted ethical clearance from UKZN (Protocol No HSS/1004/013). It was guided by the following research questions:

1. What do educator-constructed maps of their schools and surrounding environments reveal about their understandings of conflict, violence and injustice?

2. How do educator-led discussions with their learners about perceptions of the school and surrounding environments shape new and revised understandings about conflict, violence and injustice?

3. What interventions do educators propose to address incidents of conflict, violence and injustice?

This article is based on an analysis of the mapping projects generated in the Peace Education and Conflict Resolution course. The data is thus not generated specifically for the study. This design carries possible benefits and limitations. The projects are generated in a multi-step process (discussed above) over a period of three months. The projects serve the purpose of action learning within the module and are therefore discussed extensively in class. The first two steps are conducted as activities in the module and are not introduced as activities for assessment until the end of the module when they are built on as part of a project. The process, time period and discussions allow for authenticity of the data to be verified and militate against fabrication of data for purposes of assessment. Given that these are social justice and peace educators, they have an interest in and commitment to the projects as it provides a means for them to research and reflect on challenges in their environment and to explore solutions in a supported manner. These factors also contribute to research quality. The limitations of this design is that the projects are developed as a module outcome and therefore the sample of participants, institutions and geographic locations are all self-selected. The study however seeks an in-depth, qualitative understanding of a small sample for the primary purpose of exploring interventions. Generalisation is not an objective of the study.

At the time that students were working on these projects, they had no sense of my research interests. Given that their work was for assessment purposes it was decided that a request to allow their projects to be used for the purpose of this research would only be made to students after the course was fully completed and all assessment processes completed. At this stage, I contacted students from two recent cohorts to seek informed consent to use their projects for this study. Students were assured of anonymity for their school and themselves. Twenty-three students gave permission for their projects to be used in this study. This article is based on analysis of these projects only.

Furthermore, only the educators' reflections on their engagement with their pupils were included as data. I did not analyse the pupils' maps and reflections directly as I did not have informed consent for this.

CONFLICT MAPPING AS PEACE PEDAGOGY AND PEACE PRAXIS

By focusing in greater detail on the pedagogical underpinnings of the mapping project, this section employs the theoretical lens of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. The primary goals of the project - to stimulate critical reflection and dialogue in exploring conflict in schools and to imagine suitable action - aligns strongly with key concepts in Freire's educational theory. Freire placed substantial emphasis on critical reflection, dialogue, and action in creating an emancipatory education which fosters hope, humanity and change. For Freire (1970, 41):

reflection - true reflection - leads to action. On the other hand, when the situation calls for action, that action will constitute an authentic praxis only if its consequences become the object of critical reflection...Otherwise, action is pure activism.

Gadotti (1996, pxi) indicates that:

For Paulo Freire, dialogue is not just the encounter of two subjects who look for the meaning of things - knowledge - but an encounter which takes place in praxis - in action and reflection - in political engagement, in the pledge for social transformation. A dialogue that does not lead to transformative action is pure verbalism.

Freire thus brought these pedagogical elements together with his central conception of praxis, the combination of action, dialogue and reflection. The concept of praxis allowed Freire to signal the unity in making meaning of one's social reality via reflection and dialogue, and transforming one's social reality via action, thereby creating new meaning. Praxis is thus a situated knowledge-making endeavour, a form of inquiry embedded in the world. Freire (1970, 72) argued:

For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, individuals cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.

The mapping projects, in getting educators to reflect critically on conflict, violence and injustice in their schools, in reflecting on their own perceptions and constructions of such conflict in relation to learner perspectives, in interrogating their so-called 'blind spots', in engaging in dialogue with other educators in class and with myself, and in engaging in dialogue with their learners and fostering dialogue amongst their learners, and then in planning and motivating for appropriate interventions (actions) could be seen as the beginnings of a peace praxis. As will be discussed later, the limited timeframe of the course does not allow for full-scale implementation of the peace interventions and reflections on such action, in other words for full praxis. However, planning for action is a necessary first step in generating hope, agency and options.

PEACE PEDAGOGY AND LEARNING

Drawing on the pedagogical principles just discussed, this section explores the different parts of the mapping project in relation to opportunities for critical reflection, dialogue and action. Finally, it discusses the combined effect of these in terms of a peace praxis. Data from students' mapping projects is provided to support the claims made about learning and change fostered by the projects.

Educators' mapping activity

This initial part of the mapping activity has been a core feature (see example of teacher map below [Figure 1]) of the project. It was introduced to assist students to ground their explorations and reflections on real, contextualised issues in their schools. However, we soon realised further benefits from this activity. Bringing these maps to class allowed for dialogue amongst students and for collective and comparative reflections on the state of schools in KwaZulu-Natal. For example, class discussion often led to comments like, 'that must be what is happening in the urban schools but we don't see that in my school' or 'this could be a feature of high schools where the learners are older'. A further aspect of reflection and analysis was enabled by having a composite picture across different schools. This understanding was explored in relation to national surveys of school violence (Leoschut 2008; Burton & Leoschut 2013) with which students had engaged as part of their coursework preparations. For example, many educator maps identified secluded areas of the school where learners were engaging in what they called 'lovemaking' and other 'illicit' behaviour. Connections were made to the exceptionally high rate of teenage pregnancy in KZN which students had read about in their course-work readings. A further key benefit from this activity was the concrete opportunity it provided us to see and understand the specific schooling contexts of the students and to connect this lived reality to the literature and theory.

In terms of Freirian theory, educator mapping thus generated reflections that were grounded in the authentic contexts of educators' workplaces. These reflections furthermore generated dialogue amongst educators (including myself), allowing for comparative and collective reflections of KZN schools to emerge.

Learners' mapping activity

This aspect of the mapping project enhanced some of the benefits discussed above. Central to this was the broadening of dialogue about the school situation when educators engaged with their learners. Furthermore, the availability of maps drawn by girl and boy learners separately (see example in Figure 2) allowed for explorations and discussions on the gendered nature of conflict, violence and injustice.

Many educators found this to be a useful exercise and learning opportunity. There were clear examples of the learners' maps raising new awareness amongst educators and even provoking them. For example, there was some surprise that the principal's office and staff room were identified as sites of conflict, violence and injustice. One student, who was a principal in his school stated:

At this point I was surprised by my learners when they mentioned my office as a place that they feel unsafe when they are in.. .They pointed out that after their class or subject teachers have failed to punish them, or feel that they can't handle their behaviour, the teachers would use the principal and his office as a way of making sure that all the wrong doers are dealt with by the might force of the principal...From where I work, the orders of the male specie are regarded as superior and there are no ways one could do otherwise. Most learners would then resort to taking punishment and verbal abuse from their teachers than going to the principal's office for a long lecture that comes with difficult and strenuous activities. Violence in schools is not limited to incidents between learners; it also includes acts perpetuated against, and by educators. (Burton 2008)

Dialogue with learners revealed that corporal punishment in the principal's office, despite being officially banned by the Department of Basic Education, was still being practised and constituted a form of violence and injustice. Learners in one school also mentioned conflict when they were called to the staff room and publicly embarrassed by teachers as a form of reprimand. Further examples of new realisations and changed perspectives can be seen in the following extracts from four different educators:

The findings revealed a shocking picture of how vulnerable learners are within the school setting, a place which instead is supposed to be a safe haven for them. Most shocking was that learners implicated teachers - 'their trusted others' - and their peers as sources of some of their misery, because of the way they conducted themselves and victimised girl learners through immoral and unacceptable sexual behaviours.

Learners identified the absence of toilet doors, especially girls, who complained that their privacy is violated.. .Their concern was that a stranger might come in and sexually abuse them.. .they [doors] were taken by the community who fix them in their houses during the holidays. The culprits are known in the community but no one is prepared to point a finger at them. They have committed violence and have killed members of the community who have tried to stop them.

The shop owner is an SGB [School Governing Body] member; I didn't think that he can sell alcohol to learners during school hours. I did not know that a lot is going on in my school up until the mapping exercise.

Concerning the use of drugs in the toilets, as educators we are not aware that it is so high as students have reported. Most learners are misbehaving especially after the break. We didn't know that it is just because they have been smoking so much dagga [marijuana] during the break.

The benefits of dialogue with learners is clearly evident in the latter quotation where an educator explained that she always wondered why her 'problem students' were most disruptive after their breaks. In her presentation to our class she explained that the mapping activity with her learners identified the toilets as a site of drug use, amongst other types of forbidden activity. She mentioned that as a teacher who does not visit the learner toilets she was not aware of the extent of dagga (marijuana) use there. The learner maps and dialogue with learners helped her to better understand her classroom dynamics. Educators often described such new perspectives gained from learner mapping and dialogue as an 'eye-opener'. The term resonates strongly with the notion of seeing afresh as conveyed in the concept of conscientisation (Freire 1970).

Most common types of conflict identified in maps

Amongst the most common types of conflict, violence and injustice identified were:

-

Bullying

-

Sexual harassment/violence

-

Alcohol and drugs

-

Weapons

-

Corporal punishment

-

Violence

The regularity with which toilets were identified as a so-called 'hotspot' was alarming and led to much discussion in class about possible interventions. Referring to a map drawn by learners this educator was not only able to identify the types of violence taking place in toilets but also connected this to other research in the literature he had surveyed:

Most boys mentioned that they are being bullied, kicked and assaulted in the toilets more often by the elder boys. They also mentioned that most of their possessions are taken at this place. According to Burton & Leoschut (2013) some learners claimed that they have experienced fear in toilets.

For most girls they preferred not to go to the toilets. They see toilets as one of the most dangerous places where girl on girl violence is perpetuated. They also mentioned that toilets are a place where they encounter abusive language, a lot of gossiping, and the development of anti-social behaviour. They become victimised through the graffiti that is written on the walls.

Educators questioned the Department of Education's lack of understanding of school dynamics in terms of how toilets were planned. In many cases toilets were located at an isolated spot on the school campus, far away from the teaching and administration buildings. This created vulnerability for learners and access for drug dealers and vagrants. They also questioned the logic of having boys and girls toilets alongside each other and the need for separate toilets for younger learners to prevent bullying and extortion of money by older learners. There were also, in some instances, concerns raised about teachers' toilets. In one school a female teacher was followed by a male teacher into the toilet, located some distance away from other buildings, and sexually harassed. These discussions also led to suggestions for how the findings generated by the mapping projects could be shared with other stakeholders like the school governing body and the department.

A further issue regularly identified in the mapping by both learners and educators was sexual violence. In some instances educators and managers were identified as perpetrators:

The area marked 4 is an administrative office and the learners identified this place as a sight [sic] of violence and injustice. The occupant has intimate relationship with school girls. This comes amidst the article released by the Department of Education citing the fact that the sexual relationship between the teachers and learners constitute sexual harassment and sexual violence.

There was a strong focus on physical conflict and violence. Only one report on a lack of facilities for disabled persons was identified as a case of injustice. This is an indication of the dominance of understandings of conflict and violence as physical acts despite coursework engagement with concepts like structural and cultural violence. More emphasis on different and non-physical forms of violence is required in future offerings of the course. An area of conspicuous silence in both educator and learner maps relates to authoritarian cultures and the lack of democracy in the way the school and curriculum is organised. Such symbolic and structural violence escaped attention, pointing to the need for interventions that sensitise learners and educators to such matters.

In terms of Freirian theory, the learner mapping can clearly be seen to deepen reflections and dialogue. One also sees the emergence of what Freire described as conscientisation - when educators develop a new awareness of their work environment and how learners experience this environment. A further key outcome from this step is that the reflections become more critical and challenging of gender and other forms of power. There is a more pronounced attempt to name the 'enemy' or violation in the examples cited above irrespective of the power and status of such violators as schools governors, managers or older boys. Freire (1970) spoke of such finding a voice and naming the world as crucial in the processes of conscientisation, empowerment and becoming free of such oppression.

Comparison of maps

The introduction of comparisons of maps holds the greatest opportunity for deep and critical reflection as espoused by Freire.

In class, students were supported in exploring the similarities and differences between learner and educator maps and were able to consider why they were seeing some things and not others. Their seminar presentations in class also allowed them to gain insights from feedback given to other students and to be exposed to a range of different examples of reflections their classmates were engaging in. They were thus able to bring a much more critical lens to assumptions, socialisation and habits of thought. The following extracts from three different projects illustrate this:

In the mapping, I focused on their physical safety and forget about their emotions, the nervousness that they experience in point A.

To me it just came as a surprise when girls raised it as another spot that is patronized by learners who abuse drugs and alcohol. To me this can be identified as another blind spot because I never thought that the settlement could be used as a hideout for drug dealers.

In my view, the daily violent activities which the learners experience has became a norm in a manner that even if reported they are not seen as serious, that itself becomes a blind-spot. Blind-spots are a result of negligence and daily exposure to violence. The more people experience a particular violence; the likely that they will...treat it as a normal thing. What also perpetuates violence in our daily lives is not listening to what our young and future adults have to say. According to Burton (2008) giving our learners a voice to talk about what affects them on daily basis could be of great help.

The following comments by an educator from one school and a principal of another regarding the practice of corporal punishment in these schools shows how the lack of identification of such sites on different maps can also stimulate critical reflection:

All of us have failed to mention the administering of corporal punishment as an issue that is associated with violence. There is still a perception by teachers that administering of corporal punishment is good for maintaining discipline in the class. I strongly feel that failure to identify the classrooms is a serious gap on my mapping. The law strongly condemns the use of corporal punishment as a means of instilling discipline to learners. It views corporal punishment as another way of perpetuating the culture of violent behaviour at schools. This is another silence which I have identified on my map.

The office of the principal was also not identified in any of the maps. As a school principal I have a responsibility to ensure staff and learner safety within the school. It is surprising that at times I collude with different forms of injustice that can be detrimental to the learners. Perhaps this is done with the hope that if I turn a blind eye [reference to corporal punishment]; discipline and order will prevail. This can be associated with the fact that in my map, I did not identify the office as one area where injustice takes place. None of the learner maps have pointed to the office as an area of conflict and injustice. Learners might have feared that they will be victims of the principal if they identify the office as a spot of conflict and injustice.

The mapping projects have stimulated greater critical reflection amongst educators about their schools and about the causes of conflict, violence and injustice. Crucially, the step of comparing educator maps with learner maps is a most productive stimulus of critical self-reflection regarding one's lens for viewing the school. The opportunity to generate classroom discussion on the influence of age and status (learner versus educator), gender, rural versus urban, and culture was served well in this step of the project. However, based on the final seminar papers, I believe there is still room to sharpen such critical reflection and self-awareness.

From a Freirian perspective, the opportunity for critical self-reflection and identification of so-called 'blind spots' and 'silence' allows individuals to bring to consciousness habits of mind and internalised oppression. These are the perspectives we gain through socialisation and come to hold for so long and so deeply that we are no longer aware of their influence as a lens to the world. When educators start to engage with the difficult task of identifying what they are failing to see and speak about and interrogate why they have such limitations, very powerful learning and self-discovery takes place. We see evidence of this important work when they say things like 'All of us have failed to mention the administering of corporal punishment as an issue that is associated with violence' and 'Blind-spots are a result of negligence and daily exposure to violence. The more people experience a particular violence; the likely that they will.. .treat it as a normal thing' very acutely. These are not just declarations of limitations, but analysis of the processes that create limitations and the normalisation of violence.

Planning a peace intervention - preparing for action

The final component of the mapping activity required students to select a key aspect of conflict, violence or injustice identified in the learners' maps and to plan an appropriate intervention in response. Students could plan a response of peace education or peace action, and many opted for combined interventions. These interventions were evidence-based in the sense that students could refer to their independent research with learners, and were theoretically-grounded and literature-based in that students were required to support their analysis and plans with reference to the literature and peace education and peace action materials provided in the course. They were also encouraged to conduct independent literature and peace programme reviews and to go beyond the extensive course materials provided.

This activity was also congruent with a number of other recommendations and principles for peace interventions that students had learnt about. It reflected the key lesson of 'acting locally' and of 'context-sensitive' peace building. A common question for new peace educators is, 'where do I start in this complex and crises-filled context?'. The mapping project provides a starting point in terms of a felt need identified by learners in the immediate environment. Learners' involvement in the identification and inclusion in the planned interventions make the interventions authentic and participatory, further important peace building principles.

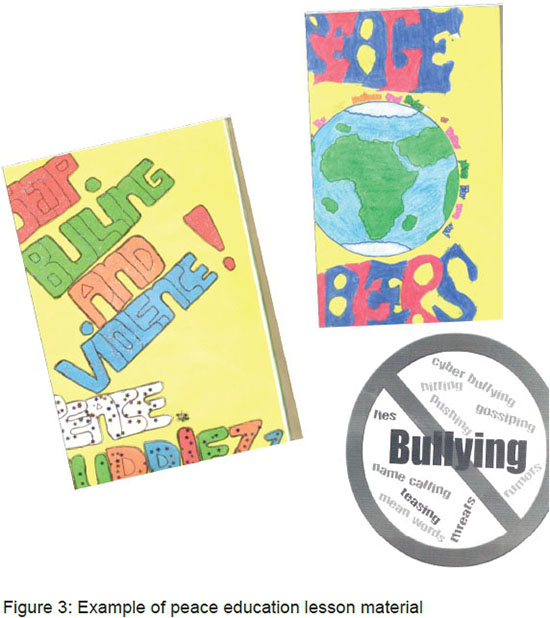

Presentations of completed mapping projects in the final class session allowed for further dialogue and peer critique, stimulating more reflections and learning. The requirement of having to engage with relevant literature throughout the project invited students into the role of peace scholarship. This is also important preparation for the dissertation research undertaken by students in the following year. Examples of planned interventions included:

-

Peace education lessons on bullying, sexual harassment etc.

-

Poster-making activities by learners on different conflict issues

-

Poetry and drama

-

Peace marches with posters made by learners

As indicated earlier, many interventions combined peace education and peace action.

A key caveat in this work is that the projects ended with plans for intervention and not the actual implementation of peace education and peace action in schools. As indicated, the course timeframes determine this endpoint. However, students are encouraged to seek opportunities to implement their planned intervention and some had started to do so. While several students see the opportunity to include peace education in their Life Orientation lessons, the course encourages them to find ways to infuse peace education across the curriculum. It was clear from the final seminar papers that five of the eighteen students in the 2013 cohort had begun to implement their interventions. These students included evidence of this with their papers in the form of learner-created posters or pictures of events (see Figure 3). The following extract reveals one such implementation of plans:

The best way for the [peace] curriculum to relate to broader school curriculum is to include it to the school subjects. In my case as I teach in the Foundation Phase it means, I will be including it when I teach FAL (First Additional Language) i.e. English, HL (Home Language) i.e. IsiZulu, Mathematics and Life Skills. I tried just a short exercise with my Grade 1 class. It was a story of peace after targeting the dumping site. Because it's a Foundation Phase activity my assessment was a question and answer method. I asked learners to write few words on how they would feel if the dumping site could be changed into a play area. The response was 'singajabula' meaning happy, 'kungaba nswempu' meaning great, a slang word used by young and old to describe a beautiful thing.. .I have kept the words as a chalkboard summary in both languages. Another thing we did, we spell the words. I then told my Grade 1 class the words on the chalkboard are words normally felt or experienced by peaceful people.

A couple of students have also pursued the conflict or violence identified via the mapping exercise through their dissertation research. The following extract is from one such student's master's research proposal where she refers to her mapping project in the previous year of study:

The passion to do a study around sexual violence in schools was prompted by a mapping exercise where learners and I had to identify areas within and outside the school where learners felt unsafe and most vulnerable, so as to explore effective intervention programmes. (Mabaso 2013)

In motivating for her master's research below, this student reveals the deep and personal reflections and dialogue which the mapping project fostered, as well as the lack of dialogue unearthed by the process. She also demonstrates how such reflection and dialogue can foster action, in her case, to learn more about the problem:

The level of uneasiness, reluctance to report and discouraging comments from both learners and teachers to pursue this issue created my desire to know more about this sensitive issue [sexual violence]. Keeping quiet and being guilty of colluding with the oppressors at the expense of vulnerable learners meant I had become 'host' to my own oppression an idea which Paulo Freire (1995) warns of. These unacceptable practices had potential to divide the school, affect learners and teachers emotionally and academically and thus affect the smooth running of the school. (Mabaso 2013)

If the mapping projects can lead to greater awareness (conscientisation) of what is taking place in the school in terms of conflict, violence and injustice, to more interest in wanting to understand this situation better and in wanting to intervene by taking action, then these projects can become catalysts to peace building and a start to a local peace praxis. There are some hopeful signs of the small beginnings in this regard and much potential for more.

CONCLUSION

The mapping projects discussed in this article evolved from a desire to teach peace education in a contextualised and action-oriented manner. It furthermore offered a potent stimulus to raising awareness, critical thinking and dialogue in understanding school-based conflict, violence and injustice, and in planning interventions. Given the limited timeframes involved, it is not possible to make claims about the mapping projects creating a localised peace praxis, apart from it serving as a possible start to such a process. My reflections over several cohorts of students and feedback from students via their projects and discussions indicate that the projects clearly serve many of the teaching and learning goals of this course. The mapping projects helped to navigate students away from a decontextualised engagement with conflict, violence and injustice as reflected in the assignments of early (pre-mapping) offerings of the course. The mapping projects generated situated learning and explorations of the lived realities of the school. The expanded version of the mapping project, developed over several cohorts, served a number of goals in the course, including:

• Praxis-oriented: involving multiple stages of reflection and action

• Intervention-oriented: integrating peace theory and practice

• Fostering critical thinking and multiple forms of dialogue

• Inviting students into the role and identity of peace educator

• Positioning educators as agents of change

As a university-based peace educator, the mapping projects and their ongoing development constitute a part of my own peace praxis, where reflection, dialogue and action with my students allow me to introduce students to the theory and practice of peace education and peace action as modes of transformative learning and change. The projects have allowed me to create a more grounded or situated learning pedagogy. As a peace researcher they also provide telling accounts of the levels of conflict, violence and injustice in KZN schools and the challenges faced by teachers. They furthermore reveal interesting diversity in perspectives on the school environment and in proposed interventions. I have learnt a tremendous amount about the complexity and challenges of intervening in our schools in positive and peaceful ways. This learning shapes other community engagement work with schools.

There is room for further refinement in these projects, particularly the need to support students in deepening critical reflections on similarities and differences in maps and in probing why these exist. A new focus on what is working in the school could also bring a more positive and assets-based approach to building peaceful places of learning and teaching. With a longer engagement with students, these projects can serve as a catalyst to a peace praxis.

Many of these educators found this to be an 'eye-opener' exercise and a source of reflection on their so-called 'blind spots'. These metaphors are particularly telling in the context of conflict analysis and intervention. Becoming aware of one's perspective, being exposed to other perspectives and being able to develop communal perspectives are vital processes in dealing constructively with conflict, violence and injustice. Such a collective perspective is a key ingredient for any joint intervention to succeed. Biton and Salomon (2006, 169) note that peace education 'that offer[s] ways of understanding the nature of conflict, one's role in it, the humanity of the other side, and ways of reconciliation are more likely to attain their goals'. The mapping projects allow for many of these elements to surface and are thus important processes to practical peace-building. One could also interpret such realisations of physical and cognitive blind spots as conscientisation for action, evoked by the mapping pedagogy of reflection and dialogue. These are also powerful generative metaphors in the context of a mapping project that sought to make conflict, violence and injustice more visible.

At a theoretical level, the research into the mapping project shows how Freirian-inspired peace projects can generate transformative learning, powerful self-discovery and collective understanding. The ability to create peace in the world must start from critical self-reflection and honest appraisal of one's silences, blind spots and collusion with violence and injustice. This is a crucial type of dialogue, a dialogue with oneself, which is an enactment of the idea that 'peace begins with me'. This prepares one for authentic dialogue with other people (educators and learners) and with other ideas and perspectives of the world. By engaging in dialogue about how socialisation shapes what we see and don't see we become open to other perspectives and can develop less blaming and 'othering' perspectives of violence and injustice. Changing our own actions and influencing the actions of others then become possible through new understandings of the self, others and the world. These cognitive and behavioural shifts are the foundations for building peace. Together, these ideas constitute a theory of change that ties personal transformation with social transformation.

REFERENCES

Abrahams, N., S. Mathews, R. Jewkes, L.J. Martin and C. Lombard. 2012. Every eight hours: Intimate femicide in South Africa 10 years later! South African Medical Research Council, Research Brief, August 2012. Retrieved from http://www.mrc.ac.za/policybriefs/everyeighthours.pdf (accessed 30 September 2014).

Alternatives to Violence Project 2002. AVP Manual: Basic Course. Plainfield, VT: Alternative to Violence Project. [ Links ]

Biton, Y. and G. Salomon. 2006. Peace in the eyes of Israeli and Palestinian youths: Effects of collective narratives and peace education programme. Journal of Peace Research 43(2): 167-180. [ Links ]

Burton, P. 2008. Dealing with school violence in South Africa. Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention (CJCP) Issue paper 4: 1-16. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. [ Links ]

Burton, P. and L. Leoschut. 2013. School violence in South Africa: Results of the 2012 National School Violence Study. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. [ Links ]

Collins, A. 2013 Bullies, sissies and crybabies: Dangerous common sense in educating boys for violence. Agenda 27(95): 71-83. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. Middlesex: Penguin. [ Links ]

Gadotti, M. 1996. Pedagogy of praxis. A dialectical philosophy of education. New York: SUNY Press. [ Links ]

Galtung, J. 1969. Violence, peace and peace research. Journal of Peace Research 6(3): 167-191. [ Links ]

Harber, C. and N. Sakade. 2009. Schooling for violence and peace: How does peace education differ from 'normal' schooling? Journal of Peace Education 6(2): 171-187. [ Links ]

Institute for Economics and Peace. 2015. Global Peace Index 2015: Measuring peace, its causes and its economic value. Retrieved from http://economicsandpeace.org/reports/ (accessed 24 June 2015).

Institute for Security Studies. 2014. Fact sheet: Explaining the official crime statistics for 2013/14, 19 September 2014. Retrieved from http://www.issafrica.org/uploads/ISS-crime-statistics-factsheet-2013-2014.pdf (accessed 6 October 2014).

John, V.M. 2013. Transforming power and transformative learning in peace educator development. Journal of Social Sciences 37(1): 81-91. [ Links ]

Kelly, A.V. 1986. Knowledge and curriculum planning. London: Harper and Row. [ Links ]

Lederach, J.P. 2005. The moral imagination: The art and soul of building peace. New York: Oxford. [ Links ]

Leoschut, S. 2006. The influence of family and community violence exposure on the victimisation rates of South African youth. Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention (CJCP) Issue paper 3: 1-12. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. [ Links ]

Leoschut, L. 2009. Snapshot results of the CJCP 2008 National Youth Lifestyle Study. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. [ Links ]

Mabaso, B.P. 2013. An exploration of teachers' understandings of sexual violence practices in schools. Unpublished Master of Education Research Proposal submitted to the School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Mennonite Central Committee 2012 Peace Clubs Curriculum. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/a/zambia.mcc.org/pc-materials/home/peace-club-materials. (accessed 30 September 2014).

Postma, D. 2014. Education as change: Educational practice and research for transformation. Education as Change 18(1): 3-7. [ Links ]

Sandy, L.R. and R. Perkins. 2002. The nature of peace and its implications for peace education. Online Journal of Conflict Resolution 4(2): 1-8. [ Links ]

Sharp, G. 2003. There are realistic alternatives. Boston: The Albert Einstein Institution. [ Links ]

Spaull, N. 2015. Schooling in South Africa: How low-quality education becomes a poverty trap. In South African Child Gauge 2015. Edited by A. De Lannoy, S. Swartz, L. Lake and C. Smith, 34-41. Cape Town: Children's Institute, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Xaba, M. 2006. An investigation into the basic safety and security status of schools' physical environments. SA Journal of Education 26(40): 565-580. [ Links ]

Zikode, S. 2011. Foreward. In N.C. Gibson, Fanonian practices in South Africa: From Steve Biko to Abahlali baseMjondolo, v-ix. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [ Links ]