Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 n.2 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/913

ARTICLES

It matters who you are: Indigenous knowledge research and researchers

Moyra KeaneI; Constance KhupeII; Blessings MuzaIII

IUniversity of the Witwatersrand Email: Moyra.Keane@wits.ac.za

IIUniversity of the Witwatersrand Email: Constance.Khupe@wits.ac.za

IIIUniversity of the Witwatersrand Email: blessingsmuza@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

It is common for researchers in Indigenous Knowledge (IK) in science education research to draw on aspects of the scientific paradigm from their science training. The consequent research seeks to be objective. This paradigm is not necessarily appropriate for IK research. While there have been calls for IK-aligned methodologies (Chilisa 2012; Keane 2008; Smith 1999) there are few examples of how this may be approached in Southern Africa. Drawing on the centrality of story and relationship in IK, we illustrate how the researcher's life experience shapes the research purpose, design and credibility. In refocusing research into IK, the relationship between research and the researcher needs greater acknowledgement. We present here story examples from three IK-science education studies.

Keywords: Indigenous methodology; life narratives; participatory research; science education; indigenous research

INTRODUCTION

'A story contains multiple meanings that can be discussed, questioned and reinterpreted.' (Brooks in Tredway & Generett 2015)

There are national and international policy drives for the inclusion of indigenous knowledge into the science curriculum. Following on from this has been extensive research into which knowledge to include, how to include it, as well as papers and books on indigenous knowledge paradigms and arguments supporting its inclusion into western education systems (Aikenhead & Elliott 2010; Keane 2006; Khupe 2014; Ogunniyi 2007a; 2007b). The motivation for this research thrust centres on redress, equity, inclusion and relevance for indigenous students. Although most of the studies are qualitative, they tend, in South Africa especially, to follow a conventional academic format with underpinning scientific modes of knowledge validation, including contractual ethics, an objectivity stance and a distancing of the researcher. While aiming for the championing of 'Other', for the inclusion of the marginalised, and for breaking the apartheid legacy which included social and intellectual separation, the researcher is ironically usually setting himself or herself apart.

In this paper we show how we entered into the research through positioning ourselves alongside research participants - a significant aspect of IK research (Lowan 2012). We present stories of our life experiences to illustrate how these shaped the purpose, design, researcher roles and relationships with communities, and the outcomes of our studies. We report on the often obscure role researchers' life experiences and their view of reality have in research processes. We consider such a position crucial especially for science education, where the neutrality and objectivity as stressed in the science disciplines is often influential and at odds with participative indigenous knowledge research (Smith 1999). We present these case studies from larger IK research projects in the genre of story which allows for multiple realities and the interweaving of complex meanings.

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE RESEARCH METHODOLOGY IN SOUTH AFRICA

Indigenous knowledge here refers to the understandings and skills developed by communities and passed from generation to generation over long periods of time. This does not imply that it is not dynamic; it is modified in response to community change. IK is embedded in a worldview which Cobern (1996, 585) describes as 'non-rational presuppositions on which conceptions of reality are grounded'. Stories may point to an underlying worldview from which the researcher sets out.

Research into IK is often motivated by the recognition of its neglected and threatened status. Research projects aiming for redress, and arguing for the inclusion of multiple worldviews and traditional wisdom still (predominantly) as mentioned, follow a western scientific perspective, using established forms to publish the knowledge, using the academic stance as the centre and the writer as the knowledge holder - lauded by name yet depersonalised as a human being (usually the opposite of the situation of the 'research subjects' who have their thoughts, words, histories and actions analysed, yet remain 'anonymous' - and uncredited for their contribution to the knowledge). As Freire critiques: 'the more you put gloves on our hands in order to avoid contamination with reality, the better a scientist you are' (Shor & Freire 1987, 13). We argue that IK research has not gone far enough in crossing these barriers between 'self' and 'other'. While much is written about the need for the inclusion of participants' voices and also for 'dialogue between Western and Indigenous.. .knowledge systems' (Drouin-Gagne 2014, 59) - the position of the researcher is usually absent.

Researchers are themselves central to the social research process because they create (or co-create) the research design and give meaning to situations and the data with which they work (Lapadat & Lindsay 1999). The choice of beginning with the researcher links to an epistemological choice (Richardson 2000). This is of course particularly applicable to Participatory Action Research (Malcolm, Gopal, Keane & Kyle 2009; Creswell 2007) where the research is embedded in a relational ontology (Datta, Khyang, Khyang, Kheyang, Khang & Chapola 2014) which fits well with the African ontological concept of Ubuntu - often presented as 'I am because we are'. In essence, this is a key motivation for including personal stories.

ALIGNING RESEARCH WITH WORLDVIEW

Different researchers conceptualise and craft research in different ways according to (among others) interests, power relations, and cultural biases. From this perspective, knowledge is not seen as an absolute truth, but a making of meaning in a particular setting and set of relationships. Carter, Lapum, Lavallee and Martin (2014, 362), in writing about research storytelling, argue that 'researchers need to begin with their own story as they seek to understand the stories of others'. While our projects are not about reflexive storytelling, the principle is applicable here as we recognise our own position before attempting to understand one another. Furthermore, what Jewkes argues for regarding autoethnography and emotion in doing prison research may be applied to IK research. We need to question the 'privileging of a methodological orientation.that downplays the researcher's.cultural experience and biography' (Jewkes 2011, 63). The researcher is appropriately part of the research process and in relationship with research participants. There exists a mutual influence of the researcher and research process and we concur with Patton (2002) that acknowledging this relationship enhances the credibility of our studies. The researcher's self-awareness and self-disclosure contribute to the authenticity of the research. Supressing this would be a culpable omission.

In many indigenous cultures there is not the same emphasis on 'knowledge' as a noun, an object or abstracted product. Knowledge is rather expressed as a 'way of being', 'a way of knowing', 'a way of living in nature' (Aikenhead 2002) and 'a way of belonging' (Khupe 2014). The notion of knowledge as a commodity, a thing discrete and apart from ourselves, each other and our wisdom of living in the moment assumes a particular view of knowledge that does not exist in an indigenous worldview. From this perspective, the researcher has a place in the research, and obscuring or overlooking this distorts our knowing. The researcher interprets events and creates texts, consciously or unconsciously imprinting themselves upon them. The researcher is not removed from the research process, place, context, and co-researchers; the researcher is herself part of, as well as able to learn from, the research community.

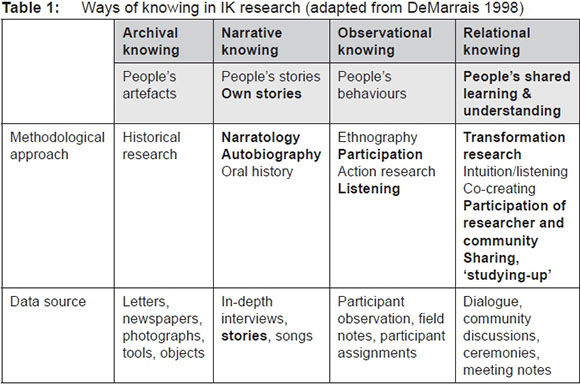

DeMarrais (1998) presents a useful framework of Ways of Knowing in Qualitative Research that we have adapted and extended to illustrate the role of the researcher in indigenous knowledge research (Table 1):

The aspects emphasised in Table 1 may be seen in the story threads that follow. Researcher stories contribute to shared learning and transformation. The aspects of knowing include: narrative knowing through own stories; observational knowing through the participation of the researcher and the community and listening; relational knowing through the transformation of researcher as well as community, and through recognising and seeking 'studying-up' in learning from elders. These aspects feature in our three autobiographies and our research projects. A number of concepts highlighted in various types of qualitative research apply here: intellectual autobiography, and the relationship of autobiography and research (LeCompte 1998; Herzog 1998). The feature of studying-up discussed by Gamradt (1998) in anthropological research is a practice of IK research when working with elders, iziNduna (Headmen), amaKhosi (Chiefs) - although not sufficiently mentioned in the literature in South Africa; perhaps an oversight in recognising the actual power hierarchies in indigenous communities.

POSITIONING OURSELVES IN OUR IK RESEARCH THROUGH OUR OWN STORY

Story writing is a selective and censored endeavour. How does one construct a narrative that is coherent and meaningful and not close down the possibilities for other versions of the story? We need to acknowledge the conundrum of capturing or even writing about intangible heritage (a synonym here for IK) and one way of doing this is to point to it in our relationships with a community. The story is infused with the spirit of the writer, mirroring the consort of physical and spiritual in an African worldview (Mbiti 1969; Oladipo 2002). Some insight into the worldview of the researcher is perhaps a more honest declaration of a 'lens' than the adopted 'theoretical framework' of conventional research requirements. As researchers we declare the origins of our perspectives and expect that these will be at least partially transformed through the participatory research process. We anticipate that we will become 'more human' in the humanity of others and recover some of the connection across our severed thinking, that we will open up more wonder, rather than arriving at certainties and answers - that we will be more able to be open-minded with what is unknown. In this approach we find resonance with Freire's 'critical consciousness' (1970) and the inseparability of action and theory. Research typically presents 'the Other' (Coombes, Johnson & Howitt 2014) but exempts the researchers from being revealed as objects of analysis.

A qualitative researcher either consciously or unconsciously takes up a position (Lumsden 2012). In IK research, a non-neutral stance needs to be acknowledged since the knowledge-discovery process is influenced by sociocultural experiences and histories that continually shape thinking (Mutua & Swadener 2004). In evolving indigenous methodologies there is a need to challenge the distanced perspective of the anonymous, detached researcher who holds the power along with the scientific academy. The intention of the story is to give readers the agency to decide the meaning - even with positionality statements, as presented here.

There is a relationship between researcher life-experiences and the research process. Our personal stories (or position statements) illustrate how life experiences influenced our research curiosities, interests and intentions and how we engaged with participants in collaborative relationships. The position statements introduce three distinct research projects but provide insight into the research rationale and quality of the process. In the following sections the authors tell a story of who they are so that the tacit knowing we bring to our research provides an example of how Indigenous Knowledge research includes the one who comes to know through participation in community.

CONSTANCE

[This research project sought to identify the IK and worldview in a remote rural community in South Africa with the intention of seeking aspects of knowledge that may be infused into the school science curricula.]

I am a Zimbabwean woman. I grew up in the reserves of Masvingo Province. I spent my primary school years 'oscillating' between family members' homes. I used to see my mother only during school holidays, when my uncle would carry me on his shoulders for a distance that well exceeded 20 kilometres. My school Geography course did not consider the human being as a form of transport.

I was never viewed as an outsider in my relatives' homes. My culture has no cousins, aunts and uncles. We have brothers, sisters, older and younger mothers and fathers. The 'extended' family, in its modern western sense, did not exist. Everyone was part of our large family. Neighbours who were not direct relatives always had their families traced through totems and marriages until they became related to everyone else. So all villagers were one large family where individuals were expected to work for the common good.

My experience of school was that it was markedly different from home. We memorised English rhymes and stories happily, although we did not understand them. The elders seemed to be aware of the lack of a contextual relevance in our education and they always reminded us to maintain unhu (Shona for ubuntu), that is, the traditional cultural norms, values, beliefs, expectations and actions. Ubuntu means 'I am a person through other people' - we are interconnected. I suppose the disjunction between school and home forced me and my friends to learn at an early age to live differently in our home and school worlds. We would, for instance, stand up (as a sign of respect) and greet the teacher or any other elders when they came into the classroom; and sat down or knelt when the same person visited us at home. My family's fears of my alienation from our cultural values might have intensified during my years in boarding school when I was at home for only three months in a year.

I remember very little of my primary school science save for a 7th grade lesson on jerrymunglums. I remember that a jerrymunglum was said to be a type of spider. The lesson came back to my mind as I was writing my doctoral research proposal and I was determined to find out more on the internet. I was surprised to learn that a jerrymunglum is commonly referred to as a hunting spider or a wind spider, because of its swift movement (Punzo 1998). In my home language a jerrymunglum is called dzvatsvatsva, a name that also relates to speed. I then realised that I had known jerrymunglums since I was a toddler, but I had known them by a different name, from a different language. Had my teacher used Shona language to mediate our learning, I would have known what we were learning about that day. Perhaps I would have understood more of that lesson and I would probably have been more interested, and perhaps I would have remembered more. I do not blame my teacher at all, because he probably did not know the 'jerrymunglums' of the textbook - he probably only knew real life jerrymunglums!

My secondary education was in a Roman Catholic boarding school. The school was part of a mission station made up of a primary school and a high school, a hospital and premises for priests and nuns. Although the mission was in the middle of a village, several strands of barbed wire kept it untainted from village influence. The whole settlement was semi-urban: electricity and tap water, jacaranda tree-lined streets, flower gardens and a variety of sporting facilities. Even the diet was different from what we had at home. In addition, we all operated on a strict schedule. Bells rang to wake us up and send us to bed, to go to class and to go for meals, and even to pray. The four years in boarding school symbolically initiated my movement away from home, away from the 'alarm' of the rooster or other early morning birds, away from telling time by the sun, the moon and the stars. As a child I had sung along to the refrains that were part of grandmother's many folk tales. Home is where the spoken word painted pictures, created and passed on histories and preserved language. At home, a person who made reed baskets was more knowledgeable than the one who could explain how to make a basket. It was at home that I learnt to balance a clay water pot on my head, to weave grass wristlets, and to arrange and tie up a bundle of firewood for carrying homeward from the forest. At home the world was the classroom.

Much of the knowledge I had acquired at home was neither required nor useful at school, and school knowledge was also not useful for practical life in our villages. No wonder that sending a child to school then was an act of faith on the part of the parents who did, and a sign of folly in the eyes of those who did not. Many of my peers did not go through primary school. My family persisted in keeping me in school in spite of much admonishing by relatives and neighbours. It was only many years later, when the influence of urban life began to be felt in the villages that school became important to more people. School became a multi-purpose key that opened doors out of the village into the cities for a 'better life'.

I trained as a teacher, after four years of secondary school. I taught at a school in a growth point. 'Growth point' is a Zimbabwean term for rural business centres that were upgraded to urban status as a way of promoting decentralisation of social and administrative services to rural areas. Growth points were therefore a kind of intersection of urban and rural life. There I experienced 'cultural confusion'. Simple things like greetings became major decision-making issues. For instance, should I greet all people that I meet in the streets in keeping with unhu/ubuntu or should I just pass and mind my own business, the urban/western style?

When I was growing up elders used to make generally accurate short-term predictions of the weather. They knew from wind directions when it was likely to rain and with what intensity, and when drizzle conditions were likely to be experienced. They could tell from very distant lighting flashes if it would rain. The repeated passing of such comments on the weather and other natural phenomena gradually helped to develop our expertise as children in making weather predictions. Room for this unwritten knowledge has not been found in school science. I regret not only my school years when this knowledge was not used as a foundation on which to build new knowledge, but my years as a teacher too, when I did not assist the students to deal with differences between their home and school knowledge. It is from this background that I sought to discover how Indigenous Knowledge (IK) could be included in school science. The two are underpinned by different worldviews (Aikenhead 1996), and finding ways of bringing them together in the science classroom could result in more effective learning for indigenous students. For me, exposure to both worldviews has not been damaging, but has been a springboard from which I have been able to reach new heights.

MOYRA

[This participatory research project engaged a rural community and their local schools (in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa) in exploring what 'relevant science education' would look like.]

It is customary in African culture not to start talking before introducing yourself. The custom goes deeper than this. This is how I found out: I wanted to invite the Inkosi (Chief) to our science festival in Chibini, a remote rural area of KwaZulu-Natal near Ixopo. We had designed a formal invitation. 'No! You can't just send an invitation - just like that,' the school principal, Mr Mkhize, remonstrated.

What to do? As often happened, I needed guidance. Mr Mkhize and I sought the intervention of the Induna (Headman). This required going deep into the valley to his homestead. It is bad form to call out so we stood in the sun on the dusty path and simply waited. After a long wait the Induna came walking down the path. We greeted him, and discussed the purpose of our visit. Following lengthy discussions he took us to the Nkosi's kraal (homestead). We drove the only road: pot-holed, long and winding into the heart of the valley. This time, on approaching the kraal, my two companions called out loudly - salutations, praise songs and greetings. Eventually a young woman opened the gate and led us to the traditional round and grass-thatched hut. We stepped into the cool dimness and sat silently. In some way we were being presented to the ancestors. Only then did we continue to the main house to wait for the Nkosi. Although we removed shoes, we were not expected to follow the old tradition of full prostrations. When the Nkosi entered I sat silently as the Induna introduced us at length: who we were, family names, place of origin, and finally why we were there. (Without the meeting of the ancestors and giving my family connections, no research project would have been possible.)

My name is Moyra. I work at a university in Johannesburg where I studied for an MSc and PhD in science education. It is also the university I dropped out of when I was 17, finding the whole huge institution too overwhelming, and being quite unable to overcome my inward-turning shyness, to lay aside my existential conflicts and anti-establishment convictions. I then soon married and moved to KwaZulu-Natal -eventually re-entering formal education 10 years later. After qualifying as a teacher I worked with students and then teachers, teaching science and in the holidays taking diverse groups of students away into the wilderness on leadership courses.

I am an English-speaking city dweller, mother, researcher, and second-child from a nuclear family. My name bears witness to my long-lost Irish ancestry. My father was an extreme atheist and communist who moved from a strong humanitarian approach to life to being bitterly disappointed with - I think - everything. In our family both my mother and father worked, but my mother also came home to cook and darn socks and could certainly never offer an opinion that contradicted my father. My father was a reporter and reading was a primary activity at home; but I was the first in any direction in the family to go to university. I suppose I had an unremarkable and fairly isolated childhood. I visited a church for the first time when I was about 25 years old. I went to my first funeral when I was in my 40s. I travelled overseas for the first time when I got divorced after 20 years of marriage.

I have never carried water on my head nor been a pupil at a rural school. I cannot trace my family back for generations. I do not have many mothers and fathers and brothers and sisters. There is no particular place and landscape that I can call 'home'.

Does it matter who I am? This is how I realised it does. At an early research meeting with the community at the school, a staff member from a neighbouring property arrived to 'make an announcement'. Without a greeting and without introducing himself he said: 'Your goats are coming on to our property and eating the flowers. If this happens again the goats will be locked up and you will pay a fine to get them back'. By now I was used to introductions, opening prayers, greetings. I heard myself thinking: 'Who is this?' (even though I knew). How does the meaning of his words change if he is a landowner, herd-boy, lunatic? It would have been helpful to know which of those he was!

At one point a principal asked if I'd ever stayed in a rural village before. I was told it was time I spoke isiZulu. Other mothers asked me about my son. Teachers who were studying asked me about my studies. A village hitch-hiker drew me into a long discussion on theology. Personal characteristics shape, limit and open up experiences.

The word 'Ixopo' derives from the onomatopoeic description of the cow's hoof pulling out of the thick wet fertile mud. In the Ixopo valley I love the space, rolling hills, wild river places, pretty goats, open fires, slow pace and vast open sky. I would not love being cold, hungry, beaten at school and having least say as a girl. I would not enjoy chorus-style teaching that leads nowhere. However, I know that my life experiences have been limited, that I have much to learn and unlearn. I have, in exploring indigenous knowledge, the privilege of reconsidering: What matters? What other ways are there of understanding the world? What does this teach me about myself?

BLESSINGS

[This research aimed to probe African students' and teachers' knowledge of traditional medicinal plants, and their potential interest in including this knowledge in an urban, multi-ethnic science classroom in a township school in Johannesburg.]

In spite of growing up in post-independence Zimbabwe, my life was still a challenge; this was not anticipated prior to independence. My interest in IK research was ignited by the dilemmas that I faced as I grew up. The 'clash' between the traditional rural lifestyle and the western urban lifestyle was part of my life from as early as my primary school days. My family, like most in Zimbabwe, has a mixed lifestyle that embraces both traditional and western worldviews.

My mother was a subsistence farmer and was based in the rural areas of Mhondoro, Zimbabwe and my father worked in Harare. I went to primary school in a township but every school holiday we were taken to the rural areas to assist my mother tend the maize fields and herd cattle. The visits to the rural areas were always sad experiences for me as I detested the strenuous chores in the fields. This may have led me to have a negative attitude towards anything traditional. I preferred the urban way of life where one would just go to the shops to buy milk instead of having to wake up early in the morning to milk the cows before the calves suckled their mothers. I remember being ridiculed by my peers from the rural area because I could not whistle or milk the cows. This further enhanced my negative attitude to the traditional way of life. At school in the township I would be ridiculed for the numerous scars from razor blade cuts (nyora) that I got from my grandfather supposedly for identity and physical strength (mangoromera). Mangoromera was meant for me to be a brave fighter but I don't recall engaging in any fights. Why then did I have to endure the pain of the razor blade? These nyora marks are still visible on parts of my body though I am not embarrassed about them now. The reason could be that having grown up I no longer have peers who ridicule me.

Having been introduced to the Christian faith where some traditional practices were not tolerated, the dilemma continued. It was always embarrassing to be associated with traditional practices when amongst fellow Christians; just as much as it was embarrassing to be associated with Christianity when amongst traditionalists. Amongst traditionalists a Christian was seen as someone who denounced their own culture in favour of the 'white' man's culture. I really did not want to be seen as one, but at the same time I felt more comfortable attending church than traditional ceremonies. I had a desire to learn about the traditional practices, but because of the Christian teachings and the fear of going to hell, I avoided them.

Later on in life the 'clashes' were resuscitated. After the birth of my first child, my wife, who has a strong rural background, insisted on some traditional muthi (medicines) to treat nhova (fontanel). I was in a dilemma as I had little faith in the practice. For the sake of the baby I gave in, although I had to go to the doctor just to be sure the baby would be fine. The muthi was a black powder which was burnt like incense and the child would inhale the smoke covered by a blanket until they urinated. The passing of urine was a sign of healing. I am not sure to this day whether it worked. Cultural 'boundaries' are a lived experience and crossing them is an everyday challenge. Exposure to these different worldviews shaped my current attitudes which are more sympathetic to the traditional knowledge systems, hence my interest in researching how I can assist learners to cross the cultural borders more smoothly than I did.

As a teacher I have worked in Zimbabwe, Botswana and currently in South Africa. In all three countries, the use of traditional medicinal plants to cure ailments is common practice. In South Africa, however, it seems more widespread, especially in townships where muthi shops and traditional healers, identified by their regalia, are commonplace. This means knowledge about traditional medicines is hugely significant. My interest in traditional medicines was increased further when I stayed with a traditional healer in 2009. His passion for his calling and his willingness to be consulted about his trade made me develop a serious interest in researching how he developed his knowledge. I could not help but notice that he was the opposite of the traditional healers I had been exposed to in Zimbabwe whom I perceived to be scary. Those traditional healers never charged a fee for their services but one would be obliged to return to 'thank' the healer if cured of their sickness. They were scary to me because I associated them with witchcraft and magic.

In my MSc studies I grappled with the dilemma of how to include IK in science teaching. These dilemmas and the desire to acquire a wider perspective about IK influenced my research questions. I had a deep personal interest in the research. I wanted to find out about the knowledge that teachers and learners have concerning traditional medicinal plants as well as their attitudes towards the integration of that knowledge into the Natural Sciences curriculum. My experiences had shaped my attitudes towards anything traditional. As a result, I believe that teacher attitudes influence the extent to which the IK and science integration policy is implemented in schools. Our attitudes towards teaching and research are a function of what we believe in (who we are) and what we know. My study allowed me to acknowledge the tensions and contradictions that are sometimes glossed over in science education research.

REFLECTION AND DISCUSSION

''Story telling is what makes us different from cattle. When you see two people together you think: Ah, there is a story there!' (Achebe 2003)

Our research studies had different aims and were carried out in different contexts, and at different times. Constance explored IK and worldview for use in school science together with a rural community in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) from 2009-2013. Moyra sought to understand what relevant science meant for a rural community, in a different area of KZN, from 2002-2006. Blessings's study (2012-2013) is set in an urban context. He sought to understand learners' and teachers' knowledge about medicinal plants and their attitudes towards the integration of that knowledge into the science curriculum. The uniting aspects of these research studies is the deep personal interest and the desire to be socially responsive to issues affecting communities -an interest that was stirred by lived experiences. The researchers had to overcome several barriers in order to achieve their individual, and research, objectives. The barriers include language, religious beliefs, community expectations, personal and academic agendas, and the need to harmonise the power imbalances between researcher and participant voices.

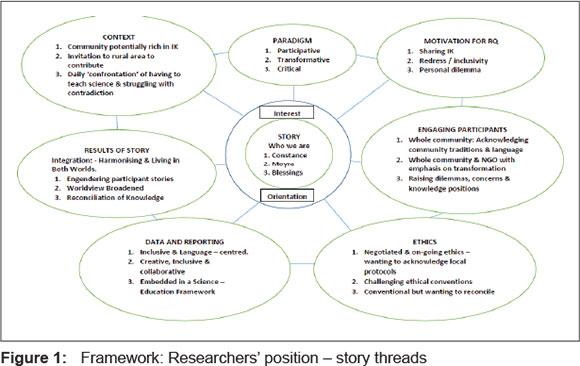

Our personal stories shaped our research in the ways shown in Figure 1. Here we summarise how key elements, all interconnected, are centred on our personal stories.

1. Constance: My interest and choice to do the study in a rural community was influenced by my rural upbringing. The perspectives of rural communities are often overlooked in both education and research, hence the choice of using participative methodology. I understood the community participants not as mere providers of data, but fellow human beings who could contribute to both education and research. The participative framework allowed for the expression of ubuntu in researcher-community relationships, allowing for sharing of power, responsibility and ownership during the study. It was necessary to engage the whole community: Elders, teachers and students, communicating in the local language for respectful representation. Communicating in isiZulu enhanced participation, resulting not only in rich data, but also in community emancipation - students, teachers and elders making suggestions on what the science curriculum for their context could look like.

As an outsider to the community, I needed cultural guidance (Vakalahi & Taiapa 2013). I realised how limited university ethical contracts were as I learnt local protocols from my cultural guides. Although I compiled the report for this study, the language, stories and perspectives of the community will always be present.

2. Moyra: My interest in both worldview and in contributing to a new democratic South Africa meant that I started out from a transformative paradigm. I also started out as an English speaking university lecturer of European decent in a Zulu-speaking rural community. Everyone knew education could not go on in the same old way as it had under apartheid. As a science teacher and researcher I asked 'What is relevant science for your school curriculum / for your community?' The reply was (basically) 'We are hungry'. I realised I was (maybe mistakenly) assuming my own research questions were relevant. As the research project progressed I teamed up with a farming NGO so that community needs could be explored alongside the research -which became more inclusive. It must be acknowledged that I struggled with my own inclusion: not speaking isiZulu, sometimes being viewed with suspicion and being challenged. The research project did manage to engage participants from the whole community - but to varying and sometimes contested degrees: the Nkosi, iziNduna, two school principals, students, parents, education department advisors, community researchers, and elders. Transformation required inclusion, openness and the negotiation of new ways of being together. Ethics was sometimes dealt with through story (drawing on precedents from the TRC1); university ethics was challenged as participants found the notion of anonymity insulting. The data collection I described as 'collaborative data creation' as the community and I found relevant science topics together and tried to find meaning in the data together. The findings were presented by the science teacher and myself at an education conference, as well as to the community at a science festival, a drama, and finally in a pictorial research-story booklet in isiZulu. The central opening up of story provided a research thread that had the potential of making sense to all.

3. Blessings: My story is situated in a critical stance. From my research paradigm, to questions, engaging participants, ethics, data, reports, results and context, I held a critical focus into the integration of indigenous knowledge and western science curriculum. Such integration would inevitably be hampered by the seemingly incoherent nature of the knowledge systems, similar to the incoherence between traditional and Christian worldviews that I experienced during my growing up. My research focused on my pedagogical needs to understand some of these challenges from a science education research perspective. As a science educator, my personal dilemmas and those observed in my learners convinced me of the need to inquire into the nature of my learners' possible concerns around any conflict between scientific understanding and traditional beliefs. I envisaged that this would facilitate a harmonious co-existence of different knowledge systems and smooth 'cultural border crossing' for the learners, and how as a teacher I could be a 'cultural guide' between cultural knowledge and school science knowledge (Aikenhead 1996).

The research involved potentially sensitive issues. With this in mind, during my engagements with the learners, I found it imperative to inculcate a culture of tolerance amongst the learners in line with ubuntu, and with my own story. I therefore included discussions and debates as data collection techniques. It was also important for me to preside and guide these discussions in order for harmony to prevail. My methodology was therefore influenced, to some extent, by my personal story. It was enlightening to observe how the learners respected and appreciated the viewpoints of others (shaped by their own stories), a sign that a harmonisation of epistemologies was indeed not impossible to achieve.

SYNTHESIS FROM OUR STORY APPROACH

In reflecting on our projects together we draw on the work of Heather Fraser (2004), identifying themes that describe what each of us brought to the study context.

Constance brought into her study the experience of a rural upbringing where language and relationships were primary. Schooling expanded her understanding of the world, making her aware that there is no one 'way of being' in the world. Her research questions were exploratory and her methodology collaborative - allowing for the status of participant in the research field.

Moyra came from a western background, and learned that there may be new ways to approach science education. For example, in asking students to take photographs of 'science in their lives' an array of local objects, aspects of nature and, importantly, people featured in the photographs. In categorising the subjects of the photos, two critical aspects were left out by the researcher and only emerged in discussion with students: beauty and deep interconnection were themes that they saw. These two features of 'science', we noted, are often omitted from science textbooks. On the other hand, an 'outsider' perspective turned out to be useful in recognising what 'was' and seeing aspects of knowledge that community members overlooked as being too familiar. An example here was the community-centred perspective: children did not draw their own dwellings but drew the whole village when asked to draw their houses. None of the community researchers noticed this as a theme. By the end of the project the community expressed appreciation for the validation of local knowledge and the opportunity for all to work together towards the education of the youth.

For Blessings, growing up facing dilemmas posed by competing knowledge and religious systems gradually provoked him into developing a willingness to understand how both work, and being able to be more at ease with ambiguities -both personal and professional.

Such an account of our brief life stories, and the incorporation of them into the research project, is also an approach used by Shawn Wilson, who claims that it is more appropriate in such research to take on the role of a storyteller rather than researcher: 'it is important for storytellers to impart their own life and experience into the telling' (Wilson 2008, 32). This is also in keeping with the centrality of relationships in indigenous research. There is an increasing expectation that the indigenous knowledge researcher's position be explicit (e.g. Mertens, Cram & Chilisa 2013; Mutua & Swadener 2004). Battiste (2008) too acknowledges the need to include the researcher's position as she outlines the ethical responsibilities of the researcher. When the researcher positions herself or himself through story, this gives the reader and research community a shared understanding of the researcher's motivation and perspectives. While most of the attempts at positioning by non-indigenous researchers are apologetic (see for example Mackinlay & Barney 2014) and may imply that no human being can share in the knowledge of the 'other' - a White researcher cannot understand an indigenous context or worldview - the plain exclusion implied in such a statement is perhaps justifiably overlooked in the attempt to redress and compensate for research that has perpetrated unjust and colonising positions. However, such a position is in itself endorsing a form of 'othering'. Stories help us to bridge awkward divides and to talk about who we are and where we come from, as illustrated in Archibald's (2008) story-work with elders in First Nation communities in British Columbia.

'The central task of a personal narrative is the creation of coherence: our lives need to make sense, to have their various elements in a reasonable relationship with one another' (Clark 2001, 87). Equally, our research needs to make sense beyond the academic discourse article; researchers and participants have relationships that need coherence and mutual understanding. This too is helped through the telling of our stories through which we illustrate what DeMarrais's (1998) notions of narrative knowing and relational knowing (Table 1) could look like in IK-science education research.

Our understanding that there is more than one way of knowing and being in the world drew us away from researcher-centred methodologies, to a choice of frameworks that allowed for the voices of indigenous peoples to be heard, as advocated by Chilisa (2012), Odora-Hoppers (2002; 2010), and Smith (1999). The use of story continued through the research processes, providing space for all voices. This reduces levels of misrepresentation and misinterpretation of participating communities (Louis 2007). Constance's experience of social relationships grounded by ubuntu influenced her choice of ubuntu as a research framework, and enabled a deep connection to the research participants (Khupe 2014). Moyra's use of story enabled her to explore new frameworks, methodologies and reporting formats (Keane 2006; 2008). Under the guidance of 'cultural consultants' (Vakalahi & Taiapa 2013), Constance and Moyra learnt the protocols relating to working with traditional leaders, and the interconnectedness of the social and the spiritual. Blessings's awareness of his own personal journey, in many ways parallel to the journey science education in South Africa is embarking on, gives authenticity to the lived experiences and dilemmas of teachers (Muza 2014). Therefore, none of us wanted a neutral relationship with our research; first because that would not be honest, and second because it would not be consistent with indigenous methodologies, and with participatory designs. We were all prepared to adopt 'new ways of seeing' (Kendall 2011, 1719 quoted in Coombes, Johnson & Howitt 2014, 3).

What we have written in our stories are parts of what we are conscious of. There may be less obvious elements of our experiences and knowledge that shaped our studies of which we are less conscious. There may be other versions of the same story (Haarhoff 1998). In reflecting on traditions and connections that have shaped us, we also open up the forward-looking aspect of IK so as not 'to lock Indigenous peoples into pre-modern development' and confinements of place (Coombes, Johnson & Howitt 2014, 2). IK is a living, evolving and shared way of being that travels with us and with our stories.

DOES IT MATTER WHO WE ARE?

'I am because of you' - yes indeed. Knowledge is closely connected to the knower (Marton & Fai 1999), and in indigenous communities, knowledge is a way of being together in the world. For this reason, we have chosen to share some of our stories in our research projects - as we have done in writing up our own research reports. We have argued for and demonstrated transformative science education research that acknowledges researcher positionality and vulnerability (Krumer-Nevo & Sidi 2012), and how that acknowledgement steered our different research projects and our relationships within a participatory and indigenous methodology. We concur with Aikenhead (2008) - an IK pioneer researcher - that objectivity may be the opiate of the academic.

CONCLUSION

Stories contribute to learning (Gargiulo 2006) and allow for nuanced perspectives and interpretations (Allen 2005; Blair 2006). In this paper we started from the perspective of personal stories or position statements. This approach influenced the whole research process from our interest and orientation towards the topic, the choice of paradigm, research questions, engagement, ethics, data and reporting as well as the outcomes and results of the research.

There are numerous calls in IK research to include the voices of participants (Burnette & Sanders 2014; Smith 1999; Wilson 2008; Odora-Hoppers 2002), yet we, while complying with (necessary) requirements for rigour, quality and authenticity, overlook the more subtle, warped power balances and more often step back from acknowledging our implication in the research story. In trying to aim for redress in ensuring participants' voices are heard (which is essential), we do not often consider the need for joining in the research as full participants, and making ourselves vulnerable and accountable in our stories. Carter et al. (2014, 374) illustrate in their dialogical and reflective storytelling that this methodology brings them 'closer to honest, transparent and ethical research'. In some of our research situations stories provided a healing rather than a factual 'truth' as we shared assumptions and perspectives with participants.

While much IK educational research calls for the integration of two knowledge systems (Battiste 2000; Ogunniyi 2004), we need to go beyond this and demonstrate the integration of an IK methodology; to demonstrate that the telling of stories contributes to the authenticity of the research process. This research approach has led us to exploring and enhancing narrative knowing, observational knowing and relational knowing, as well as proposing how 'story threads' run through the various aspects of the research process.

REFERENCES

Achebe, C. 2003. Ubuntu. Retrieved from http://web.cocc.edu/cagatucci/classes/hum211/achebe2.htm. (accessed 14 September 2014).

Aikenhead, G.S. 1996. Science education: Border crossing into the subculture of science. Studies in Science Education 27: 1-52. [ Links ]

Aikenhead, G.S. 2002. Cross-cultural science teaching: Rekindling traditions for Aboriginal students. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education 2(3): 287304. [ Links ]

Aikenhead, G.S. 2008. Objectivity: The opiate of the academic? Cultural Studies in Science Education 3(3): 581-585. [ Links ]

Aikenhead, G.S. and D. Elliott. 2010. An emerging decolonizing science education in Canada. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education 10(4): 321-338. [ Links ]

Allen, K. 2005. Organisational storytelling. Franchising World 37(11): 63-64. [ Links ]

Archibald, J. 2008. Indigenous storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body and spirit. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [ Links ]

Battiste, M. 2008. Research ethics for protecting indigenous knowledge and heritage: Institutional and researcher responsibilities. In Handbook of critical indigenous methodologies. Edited by N.K. Denzin, Y.S. Lincoln and L. Tuhiwai Smith, 497-509. Berkeley: CA Sage. [ Links ]

Battiste, M. 2000. Language and culture in modern society. In Reclaiming indigenous voice and vision. Edited by M. Battiste, 192-208. Vancouver: UBC Press. [ Links ]

Biakolo, E. 2002. Categories of cross-cultural cognition and the African condition. In Philosophy from Africa. 2nd edition. Edited by P.H. Coetzee and A.P.J. Roux, 9-19. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Blair, M. 2006. Renewable energy: How story can revitalize your organization. The Journal for Quality and Participation 29(1): 9-13. [ Links ]

Burnette, C.E. and S. Sanders. 2014. Trust development in research with indigenous communities in the United States. The Qualitative Report 19(44): 1-19. [ Links ]

Carter, C.N.M., J.L. Lapum, L.F. Lavallee and L.S. Martin. 2014. Explicating positionality: A journey of dialogical and reflexive storytelling. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 13: 362-367. [ Links ]

Castle, P.J. 2013. I had no time to bleed: Heroic journeys of PhD students in a South African school of education. Journal of Education 57: 103-125. [ Links ]

Chilisa, B. 2012. Indigenous research methodologies. Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

Clark, M.C. 2001. Off the beaten path: Some creative approaches to adult learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education (89): 83-92.

Cobern, W.W. 1996. Worldview theory and conceptual change in science education. Science Education 80(5): 579-610. [ Links ]

Coombes, B., J.T. Johnson, and R. Howitt. 2014. Indigenous geographies III: Methodological innovation and the unsettling of participatory research. Progress in Human Geography 38(6): 845-854. [ Links ]

Cram, F., B. Chilisa and D.M. Mertens. 2013. The journey begins. In Indigenous pathways into social research: Voices of a new generation. Edited by D.M. Mertens, F. Cram and B. Chilisa, 11-40.Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2007. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Datta, R., N.U. Khyang, H.K.P. Khyang, H.A.P Kheyang, M.C. Khyang and J. Chapola. 2014. Participatory action research and researcher's responsibilities: An experience with an indigenous community. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18(6): 581599. [ Links ]

deMarrais, K.B. 1998, ed. Inside stories: Qualitative research reflections. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [ Links ]

Drouin-Gagne, M. 2014. Western and indigenous sciences: Colonial heritage, epistemological status, and contribution of a cross-cultural dialogue. Ideas in Ecology and Evolution 7: 5661. [ Links ]

Fraser, H. 2004. Doing narrative research: Analysing personal stories line by line. Qualitative Social Work 3(2): 179-201. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Gamradt, J. 1998. 'Studying up' in educational anthropology. In Inside stories: Qualitative research reflections. Edited by K.B. deMarrais, 67-79. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [ Links ]

Gargiulo, T.L. 2006. Power of stories. Journal for Quality and Participation 29(1): 5-8. [ Links ]

Haarhoff, D. 1998. The writer's voice: A workbook for writers in Africa. Halfway House: Zebra Press. [ Links ]

Hall, M. 2010. Community engagement in South African higher education. In Community engagement in South African higher education. Council on Higher Education (CHE), 1-52. Kagisano No.6 January 2010.

Herzog, M.J.R. 1998. Teacher-researcher: A long and winding road from the public school to the university. In Inside stories: Qualitative research reflections. Edited by K.B. deMarrais, 151-160. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [ Links ]

Jewkes, Y. 2011. Autoethnography and emotion as intellectual resources: Doing prison research differently. Qualitative Inquiry 18(1): 63-75. [ Links ]

Keane, M. 2006. Understanding science curriculum and research in rural Kwa-Zulu Natal. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Keane, M. 2008. Science learning and research in a framework of ubuntu. In Democracy, human rights and social justice in education. Edited by C. Malcolm, E. Motala, S. Motala, G. Moyo, J. Pampallis and B. Thaver. Centre for Education Policy Development (CEPD): Johannesburg.

Khupe, C. 2014. Indigenous knowledge and school: Possibilities for integration. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of the Witwatersrand. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Krumer-Nevo, M. and M. Sidi. 2012. Writing against othering. Qualitative Inquiry 18(4): 299309. [ Links ]

Lapadat, J.C. and A.C. Lindsay. 1999. Transcription in research and practice: From standardization of technique to interpretive positionings. Qualitative Inquiry 5(1): 64-86. [ Links ]

LeCompte, M.D. 1998. Synonyms and sequences: The development of an intellectual autobiography. In Inside stories: Qualitative research reflections. Edited by K.B. deMarrais, 197-210. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [ Links ]

Louis, R.P. 2007. Can you hear us now? Voices from the margin: Using indigenous methodologies in geographic research. Geographical Research 45(2): 130-139. [ Links ]

Lowan, G. 2012. Expanding the conversation: Further explorations into indigenous environmental science education theory, research, and practice. Cultural Studies of Science Education 7(1): 71-81. [ Links ]

Lumsden, K. 2012. 'You are what you research': Researcher partisanship and the sociology of the 'underdog'. Qualitative Research 13(1): 3-18. [ Links ]

Mackinlay, E. and K. Barney. 2014. Unknown and unknowing possibilities: Transformative learning, social justice and decolonising pedagogy in Indigenous Australian Studies. Journal of Transformative Education 12(1): 54-73. [ Links ]

Malcolm, C., N. Gopal, M. Keane and W.C. Kyle. 2009. Transformative action research: Issues and dilemmas in working with two rural South African communities. In Researching possibilities in mathematics, science and technology education. Edited by K. Setati, R. Vithal, C. Malcolm and R. Dunphath, 193-212. New York: Nova Science Publishers. [ Links ]

Marton, F. and P.M. Fai. 1999. Two faces of variation. 8th European conference for learning and instruction, Goteborg University, Goteborg, Sweden, August.

Mbiti, J.S. 1969. African religions and philosophy. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Mertens, D.M., F. Cram and B. Chilisa, eds. 2013. Indigenous pathways into social research: Voices of a new generation. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [ Links ]

Mutua, K. and B.B. Swadener. 2004. Introduction. In Decolonising research in cross-cultural contexts: Critical personal narratives. Edited by K. Mutua and B.B. Swadener, 1-19. New York: SUNY. [ Links ]

Muza, B. 2014. South African Grade 9 teachers ' and learners' knowledge about medicinal plants and their attitudes towards its integration into the science curriculum. Unpublished MSc dissertation. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Odora-Hoppers, C.A. 2010. Emerging African perspectives on values in a globalising world. In Values, religions and education in changing societies. Edited by K. Sporre and J. Mannberg, 147-156. Dordrecht: Springer. [ Links ]

Odora-Hoppers, C.A. 2002. Indigenous knowledge and the integration of knowledge systems. In Indigenous knowledge and the integration of knowledge systems: Towards a philosophy of articulation. Edited by C.A. Odora-Hoppers, 2-22. Cape Town: New Africa Books. [ Links ]

Ogunniyi, M.B. 2007a. Teachers' stances and practical arguments regarding a science-indigenous knowledge curriculum: Part 1. International Journal of Science Education 29(8): 963-986. [ Links ]

Ogunniyi, M.B. 2007b. Teachers' stances and practical arguments regarding a science-indigenous knowledge curriculum: Part 2. International Journal of Science Education 29(10): 1189- 1207. [ Links ]

Ogunniyi, M.B. 2004. The challenge of preparing and equipping science teachers in higher education to integrate scientific and indigenous knowledge systems for learners. South African Journal ofHigher Education 18(3): 289-304. [ Links ]

Oladipo, O. 2002. Metaphysics, religion, and Yoruba traditional thought: An essay on the status of the belief in non-human agencies and powers in an African belief system. In Philosophy from Africa. 2nd edition. Edited by P.H. Coetzee and A.P.J. Roux, 200-208. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Patton, M.Q. 2002. Qualitative research and qualitative evaluation methods. 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Punzo, F. 1998. The biology of camel-spiders (arachnida, aolifugae). New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Richardson, L. 2000. Writing: A method of inquiry. In Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. 3rd edition. Edited by N.K. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, Y. Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

Shor, I. and P. Freire. 1987. A pedagogy for liberation: Dialogues on transforming education. Granby, MA: Bergin & Garvey. [ Links ]

Smith, L.T. 1999. Decolonising methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Tredway, L. and G. Generett. 2015. Story mapping: An innovative process for uncovering community assets and building shared leadership capacity. AERA Workshop notes. April 16, 2015 Chicago IL.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission. 1998. TRC Report on South Africa. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Vakalahi, H.F.O. and J.T.T. Taiapa. 2013. Getting grounded on Maori research. Journal of Intercultural Studies 34(4): 399-409 [ Links ]

Van der Post, L. 1982. Wilderness and the human spirit. In Wilderness. Edited by V. Martin, 66-75. Moray: The Findhorn Press. [ Links ]

Van der Post, L. 1978. Jung and the story of our time. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Wilson, S. 2008. Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Halifax & Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing. [ Links ]

1 The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1998)