Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Education as Change

versión On-line ISSN 1947-9417

versión impresa ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 no.1 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/556

Linking classroom and community: A theoretical alignment of service learning and a human-centered design methodology in contemporary communication design education

Anneli BowieI; Fatima CassimII

IUniversity of Pretoria. Email: annelibowie@gmail.com

IIUniversity of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

The current emphasis on social responsibility and community collaboration within higher education has led to an increased drive to include service learning in the curriculum. With its emphasis on mutually beneficial collaborations, service learning can be meaningful for both students and the community, but is challenging to manage successfully. From a design education perspective, it is interesting to note that contemporary design practice emphasises a similar approach known as a human-centered design, where users are considered and included throughout the design process. In considering both service learning and human-centered design as foundations for design pedagogy, various philosophical and methodological similarities are evident. The paper explores the relationship between a service learning community engagement approach and a human-centered design approach in contemporary communication design education. To this end, each approach is considered individually after which a joint frame of reference is presented. Butin's service learning typology, namely the four Rs - respect, reciprocity, relevance and reflection - serves as a point of departure for the joint frame of reference. Lastly, the potential value and relevance of a combined understanding of service learning and human-centered design is considered.

Keywords: design education, human-centered design, service learning, curricular community engagement, experiential learning

INTRODUCTION

From a global perspective, there is currently an increased emphasis on social responsibility as well as the role of community engagement within higher education. More specifically, the focus is placed on curricular and research-related community engagement where community engagement activities are formally integrated into the curricula of undergraduate and postgraduate programmes. The aim of these activities is to establish a mutually beneficial and respectful collaboration in the teaching, learning and scholarship of educators, students and external partners such as schools, community service agencies and organisations, to name a few.

When mutually beneficial collaborations take place, such activities are referred to as service learning. Robert Bringle and Julie Hatcher (1996:222) define the activity of service learning 'as a course-based, credit bearing educational experience in which students participate in an organised service activity that meets identified community goals and reflect on the service activity in such a way as to gain further understanding of the course content, broader appreciation of the discipline, and an enhanced sense of civic responsibility'. Furthermore, according to Anne Colby, Thomas Ehrlich, Elizabeth Beaumont, Jennifer Rosner and Jason Stephens (2000:xxix), service learning considers the development of the student as an accountable and engaged participant in society.

Owing to the pedagogic foundation of service learning, it needs to be adapted for use by different disciplines as part of disciplinary specific curricula. For purposes of this article, service learning is considered for use within the discipline of communication design. Drawing on the abovementioned focus of service learning, it is worth noting that contemporary communication design practice shares a similar viewpoint about collaboration and social responsibility. In order to deliver more responsible and sustainable design products, contemporary design practice is increasingly focused on what is known as human-centered design approaches, where the user is considered and ideally included throughout the design process. A greater understanding of users and their context is reached through an iterative design process, which includes user research, co-creation, prototyping, continuous reflection (in-action and on-action) and critical evaluation of outcomes.

Human-centered design is not a new concept but has evolved over time to indicate a shifting emphasis from a focus merely on desiging products, to designing for, and with, the people who use those products. In this way, end-users are given a face and are not just seen as a homogeneous entity. A human-centered approach therefore emphasises relevance, sustainability and accountability throughout the process and aims to create products that 'make life better' (Frascara 2002:39). Here the word 'product' does not only denote tangible products but extends to intangible outcomes such as experiences as well.

Design students need to be made aware of their roles and responsibilities within the design industry and broader society, not only in terms of commercial enterprise, but also social enterprise. This stance of design as a social enterprise is supported by current trends in design discourse, which include themes such as design for social change (Shea 2012) and design for development (Oosterlaken 2009). In order to prepare communication design students to realise their widespread potential and contribution to social innovation, educators need to include experiential learning opportunities in the curriculum to instil and foster civic and social values such as responsibility, accountability as well as empathy.

Considering higher education in general and more specifically design education outlined above, the aim of the article is to theoretically align a service learning community engagement approach and a human-centered design approach. Each approach is defined and considered individually by means of a literature review before a joint frame of reference is presented. Dan Butin's (2003) service learning typology, namely the four Rs - respect, reciprocity, relevance and reflection - serves as a point of departure for the joint frame of reference between the two approaches. This comparison is done in order to explore the value of new methodologies for experiential learning within the context of design education. Reference is made to students' reflections on a design project to illustrate some of the theoretical concepts and to show the link between theory and practice.

This research is of particular significance to communication design educators at tertiary institutions in South Africa and abroad since they have the responsibility of putting theory into appropriate and meaningful teaching practice. To this end, the research aims not only to inform pedagogy but also to act as a springboard for additional research to advance the body of knowledge on community engagement within design.

SERVICE LEARNING

As noted in the introduction, community engagement, and more specifically service learning, is increasingly found on the agenda of higher education institutions as a core value, both nationally and internationally, and is a practice that draws on the knowledge base of the scholarship of engagement. Frances O'Brien (2009:30) acknowledges that the scholarship of engagement is a concept that was advocated by Ernest Boyer, 'who expanded the (Western) traditional notion of scholarship as purely research - the discovery of knowledge - to include the teaching, integration and application of knowledge'. More specifically, Boyer (1996:20) positions the scholarship of engagement as an activity that connects the resources of a university with pressing social, civic and ethical problems with a larger purpose in order to create 'a special climate in which the academic and civic cultures communicate more continuously and more creatively with each other'.

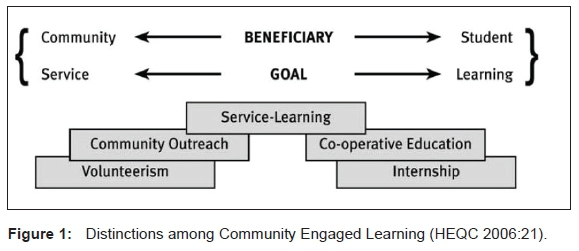

Within this context of engagement, there are various forms of service programmes that are adopted by teachers and students. Drawing on Andrew Furco's continuum (Figure 1), the South African Higher Education Quality Committee (HEQC) differentiates between these forms of service programmes by considering their position on the continuum in terms of two variables: 'the primary beneficiaries of the service (i.e., community or student); and the primary goal of the service (i.e., community service or student learning)' (HEQC 2006:21).

As one type of community engagement, service learning sits in the centre of Furco's continuum. This implies that there is a balance between the intended beneficiary of the service and the goal of learning. A number of authors, including Furco (2011) and Dwight Giles and Janet Eyler (1994), attribute the definition of service learning to Robert Sigmon, who claimed that it is service learning when both, those who are providing the service and the recipients of the service, learn from the engagement with each other. Hence, service learning can be defined as 'an experiential education approach that is premised on "reciprocal learning"' (Sigmon, in Furco 2011:71).

However, there is still some confusion with regards to terminology. Butin (2003:1676) recognises the multitude of definitions of service learning by referring to the many descriptions used when trying to define service learning activities, namely: 'academic service learning, community-based service learning, [and] field-based community service'. From a South African perspective, Lesley Le Grange (2007:3) lends a critical view to the discourse by stating that service learning 'continues to be the subject of debate and deliberation'. Butin (2003), however, sees merit in this deliberation of definitions because he believes that the different conceptions allow for flexibility in the enactment of service learning across different disciplines. The fluidity of definitions for service learning speaks to the idea that service learning should be adopted as an approach or a mind-set. Therefore, although service learning may be interdisciplinary in its practice, it is inextricably bound to the application of disciplinary specific skills to familiarise students with course content; the definition of service learning by Bringle and Hatcher (1996), provided in the introduction, supports this viewpoint.

Despite the lack of a single definition, experiential education as a theoretical and pedagogical foundation for service learning is a recurring premise in service learning literature (Giles & Eyler 1994; Saltmarsh 1996; HEQC 2006; Le Grange 2007). Furthermore, there is also the recognition that service learning has its roots in the educational pedagogy of constructivism, which is consistent with experiential education's stance that knowledge is gained through personal experience (HEQC 2006:14). John Dewey, a pragmatic philosopher and one of the key twentieth century thinkers, emphasised the importance of hands-on learning and although he did not use the term 'service learning', his insight and his philosophy of experiential education have subsequently informed and contributed extensively to the pedagogy of service learning (HEQC 2006:15).

Dewey's succinct analysis of American education in his seminal book, Education and experience (1938), introduced his philosophy of experience. His philosophy is premised on the idea that learning scenarios and educational experiences are necessary for students so that they do not operate in silos, far removed from the real world. Furthermore, he argued for an education that had the potential for social and ultimately, political transformation. To this end he supported the idea of a democratic community through face-to-face interaction in education contexts. Dewey's (1938) sentiments about face-to-face interaction also extend to the interaction between the educator and the student. He believed that there should not be a top-down hierarchy between the teacher and the student and that there should be mutual respect and participation between the two. These tenets of experiential learning as proposed by Dewey have been instrumental to the discourse of service learning and are further considered in the joint frame of reference.

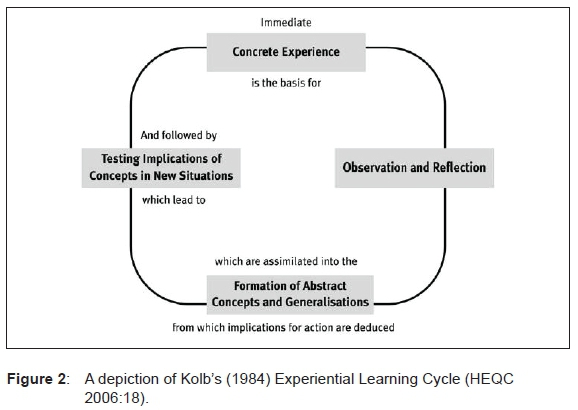

David Kolb (1984), also influenced by the work of Dewey, explored the learning styles and processes of experiential learning and developed his own model, namely the experiential learning cycle (Figure 2). This cycle 'explores the cyclical patterns of all learning' (HEQC 2006:17) and comprises four stages, including experience, reflection, conceptualisation and action. The four stages are closely linked to the following criteria for service learning programmes at a tertiary education level (HEQC 2006:25):

- Relevant and meaningful service with the community

- Enhanced academic learning

- Purposeful civic learning

- Structured opportunities for reflection.

The abovementioned criteria for service learning form a particular conceptual framework for service learning as pedagogy and also as a form of inquiry. The framework is informed theoretically by Dewey and is evident in the literature on service learning by authors such as Giles and Eyler (1994) as well as by Saltmarsh (1996). Their research is carried out as a means of 'advancing a body of knowledge and as a guide for pedagogical practice' of service learning (Giles & Eyler 1994:77). Accordingly, Giles and Eyler (1994) argue that theory drives the research agenda for service learning. Although focusing on the theoretical foundations of service learning (Le Grange 2007), as well as service learning in practice within the context of higher education (Butin 2006) have been criticised, the aim of this article is not to critique the theory and practice of service learning per se, but rather to present the nature of service learning in order to facilitate the subsequent comparison with a human-centered design methodology.

HUMAN-CENTERED DESIGN

Design is inherently connected to human concerns and has been advocated as such by seminal design theorists Richard Buchanan and Jorge Frascara. Buchanan (2001b:9) defines design as the 'human power of conceiving, planning, and making products that serve human beings in the accomplishment of their individual and collective purposes'. Similarly, Frascara (2002:37) sees design as a 'problem-oriented, interdisciplinary activity' that deals with complex interrelationships between people and their products. According to Buchanan (2001b:14), an increased awareness of how products influence human experience, as well as how products mediate interactions between people and their social and natural environments, has led to a shift towards what is known as human-centered design. Frascara (2002:33) also calls for a greater understanding of the complexities of 'people-centered design', where the focus of the design activity is on people instead of solely on products. This viewpoint shifts the contemporary understanding of design away from the modernist adage that form merely follows function. This view is further supported by Klaus Krippendorff (2005:13) who explains how design in the post-industrial society has shifted from being product-or production-centered to being a human-centered activity. More recently, Sabine Junginger (2012:171) has provided the following comprehensive summary of the principles of human-centered design, which serves as a working definition for purposes of this paper:

A human-centered design approach fully embraces the social, political, ecological and economical context in which individual interactions take place. Furthermore, human-centered design pays attention to the ways in which any product or service enables, encourages or discourages, even disables, a person to engage with other people, objects, services and environments. A focus of human-centered design is therefore on the human relationships people and groups of people have or may have.

Although the terms 'human-centered design' and 'user-centered design' are often used interchangeably, various theorists such as Buchanan (2001a), Bruce Hanington (2003), Junginger (2012) and Krippendorff (2005) identify distinctions between the terms. Krippendorff (2005:59), for instance, finds the phrase 'user-centered design' problematic since it oversimplifies the user as a 'statistical artifact' that needs to be targeted, often at the expense of others who may also be influenced by the production or use of the design product. Junginger (2012:172) also argues that human-centered design relates to a broader responsibility connected not only to the individual but also to relationships and collective experiences, acknowledging for example that certain products may be meaningful to some while being detrimental to society or the environment. As a result, both individual and collective experiences are considered in human-centered approaches.

Furthermore, the term 'human-centered design' clarifies and humanises the understanding of the practice, beyond that of usability and user testing to include a vast range of 'softer' human concerns that need to be addressed such as 'product desirability, pleasurable interactions, and emotional resonance' (Hanington 2003:10). Frascara (2002:39) also considers the broader range of human needs that moves beyond mere product efficiency and recognises three areas of design practice: 'design that works to make life possible, design that works to make life easier, and design that works to make life better'. This last objective, 'to make life better' is particularly complex as it focuses on promoting sensual and intellectual enjoyment, mature feelings, higher consciousness as well as cultural sensitivity (Frascara 2002, 39). Design activities from this perspective are thus aimed at improving the overall quality of life. Similarly, Buchanan (2001a:37) provides a holistic understanding of human-centered design practice as that which aims to 'support and strengthen the dignity of human beings as they act out their lives in varied social, economic, political and cultural circumstances'.

In order to produce products that are highly usable, meaningful, ethical and ultimately sustainable, designers need to acquire an in-depth understanding of users and larger communities. Human-centered design thus emphasises research as an 'integrated process that includes active consultation with people (users) through various means of primary research during all phases of design development' (Hanington 2010:18). Newer approaches to human-centered design research specifically encourage the active participation of users and communities throughout the design process. Elizabeth Sanders (2002:6) describes this shift towards participatory design approaches, also referred to as 'post-design'. This shift indicates a blurring of boundaries between designer and researcher and the user becomes an integral member in the design team (Sanders 2002:2). Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers (2008) describe co-design as an important shift in design practice, where the creative collaboration between designers and other people not trained in design leads to more appropriate solutions. Sanders (2002) acknowledges the different extents to which end-users are part of the design process; nonetheless, they should be consciously considered and consulted in order to make more appropriate and also ethical design decisions.

Human-centered design thus indicates a shift away from the designer as 'lone genius or authority' towards a practice where the designer collaborates with users and other stakeholders (Krippendorff2005:36). This realisation that designers cannot simply impose their solutions onto others indicates an increased level of respect and sensitivity towards those who will be affected by design products. Consequently, the main aim of human-centered design is to create more relevant and sustainable products through socially, politically and environmentally responsible approaches.

This changing emphasis in design practice has implications for design education as well. A new generation of designers need to be educated in a way in which values such as responsibility and sustainability become integral to their ways of design thinking and practice.

At the Design Education Forum of Southern Africa (DEFSA) conference in 2000, Buchanan (2000) argued that principles of human-centered design need to be built into a new framework for design practice, design education and design research in South Africa. The vast amount of social, political and environmental problems faced in contemporary South African society needs to be addressed by upcoming young designers and in order for them to do so, they will need to acquire a 'broader humanistic point of view' that will help them understand the complexities surrounding these problems (Buchanan 2001b:38). Buchanan's call for human-centered design, although over a decade ago, continues to have urgency because there are increasing social, political and environmental problems that need to be addressed. It is this social and historical backdrop of South Africa that motivated the recent introduction of the Critical Citizenship module at Stellenbosch University within the Visual Communication Design curriculum (Constandius & Rosochacki 2012). Pedagogic undertakings such as these are significant insofar as they aim to change the cultural and historical attitudes and perceptions of students as well as narrow the divide between the academic environment and society at large. Within this practice-based context, a dedicated theoretical model, such as the proposed joint frame of reference for service learning and human-centered design, may prove useful.

LINKING CLASSROOM AND COMMUNITY

Contemporary research and/or practice that focus on the link between service learning and human-centered design have recently surfaced at the EPICS Engineering Program at Purdue University, where 'multidisciplinary teams of students partner with local community organisations to identify, design, build, and deliver solutions' to meet the community needs (Zoltowski, Oakes & Chenoweth 2010). Carla Zoltowski, William Oakes and Steve Chenoweth (2010) explain how service learning, as increasingly part of tertiary curricula, may offer 'synergistic opportunities to create a human-centered design experience'. They acknowledge that teaching human-centered design within the undergraduate curriculum proves challenging because students are required to work directly with users (Zoltowski et al. 2010). However, despite Zoltowski et al. (2010) realising the benefits and challenges of 'teaching human-centered design within a service learning context', they do not explicitly explore or analyse the underlying similarities in both these methodologies. To this end, the following discussion aims to address the similarities between the two methodologies from a design education perspective. There has been an emergence on literature on service learning within the disciplines of architecture and urban planning (Angotti, Doble & Horrigan 2012) for example, but there is a general scarcity of information pertaining to communication design. As such, the vantage point in this paper is communication design education and, more specifically, theory is illustrated in relation to a particular Design for Development project.

In an attempt to develop students' understanding of human-centered design and provide them with a civic and an accordingly 'broader humanistic point of view', as advocated by Buchanan (2001b:38), Design for Development projects are regularly included in the Information Design curriculum at the University of Pretoria's Visual Arts Department. In their fourth year of study, students are required to complete a service learning module and this specific project is traditionally aligned with ideals pertaining to design for development and human-centered design. In March 2012 the final year Information Design students participated in a Design for Development project at a local correctional facility. The project required students to identify specific needs within the correctional facility context and to conceptualise innovative design solutions that are aligned with the overall goals of the South African Department of Correctional Services.

As part of the project, students visited the correctional facility on four occasions and interacted directly with the offenders in focus group settings. Throughout their research process, students identified needs related to issues in health care, education, and skills development, among others. During the latter sessions students had the opportunity to test prototypes of their design ideas and gain feedback from the user community. Students also interviewed wardens and social workers to help them identify relevant needs and challenges within the correctional facility. As a short, three-week project, students were able to conceptualise, develop and, in a few cases, test prototypes.

Throughout the project students were required to reflect on their experiences, by means of writing two reflection essays - one prior to the first focus group session and the other after project completion - and also by documenting the project in log books. Students were asked to reflect on their concept development and design process as well as their role in affecting social change, both within the specific project setting and the larger context of their environment and profession.

The inclusion of the reflection essays and log book requirements served multiple purposes. Firstly, as recommended in service learning literature, reflection encourages critical thought and helps to embed knowledge gained throughout the educational experience. Yates (1999:21), for example, affirms that '[a] number of service researchers have recommended essay reflections as a way of accentuating the influence of service experience'. From the educators' perspective, the essays were useful in gauging whether students found the community engagement project meaningful and whether similar projects should be included in the curriculum in future. Lastly, the reflection essays also contain valuable insight on the students' perspectives of service learning and human-centered design projects in the curriculum. Excerpts from these Design for Development project reflection essays are referred to in the following joint frame of reference, in order to illustrate the theoretical links between service learning and human-centered design approaches.

A joint frame of reference

From the respective discussions of service learning and human-centered design above, it is evident that an emphasis on community engagement and collaboration is a shared attitude in both methodologies. Furthermore, similar philosophies, regarding responsibility and accountability in practice, are also found in both approaches. These similarities therefore provide a point of departure to compare the two approaches in more depth. For purposes of the article, Butin's (2003) simple, yet inclusive, typology of service learning, namely the four Rs - respect, reciprocity, relevance and reflection - is adopted as a joint frame of reference for the subsequent discussion. This choice is not to impose a limit on the objective of this study but rather to serve as an entry point for further consideration of the similarities between service learning and human-centered design methodologies. Each of the four Rs is first briefly defined and then related to service learning and human-centered design, respectively.

Respect

Respect can be regarded as a cornerstone of service learning as it relates to an increased value of community and also promotes civic and, more significantly, democratic ideals. Accordingly, respect relates not only to political ideals but to actions and conduct in accordance with good morals and ethics. It is a characteristic that is articulated consistently in writing about service learning as well as human-centered design in terms of the need for respect of circumstances, views and ways of life of the various project participants. The immediate and direct engagement that is required in service learning involves student participation in a community. Such active civic participation calls for social responsibility in the identification of pressing needs as well as an attitude ofjustice in the provision of a service to address those needs (Saltmarsh 1996:17).

Dewey was of the belief that education, by its very nature, is a social process and that 'education involves socially interconnected action for a particular social end' (in Saltmarsh 1996:16). The interconnected action comprises 'face-to-face' association with the community and this in turn lends itself to an education and practice of cultural democracy. According to Dewey, the development of one's sense of self is dependent on engagement with other people. Saltmarsh (1996:16) also notes that Dewey spoke of a 'community of interests' where the common good is given priority over self-interest. Within an African context, it is worth mentioning that this position is in keeping with the humanist philosophy of Ubuntu; summarised well by the familiar idiom: I am because we are. Students are therefore challenged to pay careful attention to cultural diversity as well as to respect differences in power, privilege and prejudice when working with a community (Academic Service-Learning 2009).

As mentioned previously, human-centered design is also rooted in principles of human dignity and human rights (Buchanan 2001a:37). In order to reinforce human dignity and rights at all times, designers need to employ sensitive and ethical methods throughout their process. Krippendorff (2005:60) describes that respect in a human-centered design process is 'granted by attentive listening and acknowledging what people say, not necessarily complying with what they want, but giving fair consideration to their views and interests'. In this regard, one student explicitly expressed the importance of respect as follows:

The main point I took away after completing this project is the fact that even though we were designing for people who have made mistakes in their lives, does not mean that they deserve less from us. The final deliverables of my project could work within a variety of different contexts and this is because I went in with the notion that I was not designing for prisoners, but I was designing for people. I believe this is a very important lesson to keep with you when involving one's self in community engagement projects. By treating the people you are investigating as one of your own, by showing them respect and by giving them a real chance to express themselves openly, you will really get a sense of what it is they are going through, and this will truly help when it comes time to come up with solutions to help them.

Open communication and dialogue are thus necessary in building mutual trust and respect. Frascara (2002:34) also argues that 'unidirectional communication is unethical and inefficient' and that ethical communication design should incorporate dialogue, partnership and negotiation with communities of use. If approached correctly, research activities within community settings can be incredibly valuable since immersion and direct engagement forge 'a sense of empathy between designer and user' (Hanington 2003:17). This empathy in turn potentially leads to an increased sense of civic responsibility and an increased understanding and urgency in assisting communities through the production of truly meaningful products. One student recalls a conversation with one of the offenders, which had a remarkable impact on the design process:

The simple act of sharing his dream humanised him; he was no longer just a prisoner, he was a person - a connection was made .... I believe this is why community engagement and intervention is so important as it helps us understand that community and sympathise with them; it helps us see things from their perspective, which enables us to design for that community.

Both service learning and human-centered design focus on collaborative or participatory approaches as this shows a greater level of respect in allowing users to express their own needs and desires, instead of making assumptions about them. This view is substantiated by Stephen Percy, Nancy Zimpher and Mary Brukardt (2006:x) who believe that 'successful partnerships should be: of the people...by the people ... and for the people'. A similar sentiment was echoed by another student:

I think I learned patience when working with an unstable community, to not just come with my questionnaire and logbook, but to engage in casual conversations. I absorbed much more by talking with the inmates than talking to them.

From the authors' experience of community engagement projects, it should be noted that although the above principle of participation outlines an ideal service learning approach, in reality, deeper understanding and sensitivity do not always come automatically to students and/or community members. Participants are likely to fail in some regards, and perhaps even offend certain partners they work with. Nonetheless, increased exposure to such complex situations is perhaps necessary to make students and community members aware of any biases or prejudices they may need to resolve. Service learning opportunities can therefore provide a valuable opportunity and experience to nurture and hone civic engagement skills for greater respect.

Reciprocity

The identification of respectful collaboration and engagement above naturally leads to the characteristic of reciprocity. The word reciprocity refers to the mutual benefit of all those who are participating in an engagement or activity (Butin 2003:1677). Reciprocity in a service learning context means that mutual benefit is gained by both the students and the selected community. In the service learning context, communities are therefore regarded as active partners and not as recipients (HEQC 2006:24). Dewey also maintained that for a service to be most successful, it needs to be a mutually beneficial and reciprocal relationship with the identified community. Therefore, the attitude with which the service should be approached should be one of justice and not of charity. In addition, a service relationship is one 'defined by opportunity, choice, social responsibility, and social need' (Saltmarsh 1996:17). It is therefore essential for student actions to address pressing social needs and instil a sense of responsibility in the participants in an empathetic rather than a pitiful manner.

However, the issue of real reciprocity, where both students and community benefit equally is extremely challenging. From the Design for Development project, it became apparent that students were acutely aware of this challenge as well. Many students expressed their concern in their reflection essays about whether their project prototypes would ever be implemented and some students felt guilty about 'using' the community as research subjects without being able to guarantee a mutually beneficial outcome. The following quote highlights this viewpoint:

The fact that the project was set in a real environment made the project more interesting and more inspiring but I also feel somewhat guilty of exploiting the offenders and I hope that something materialises from the project.

Despite the question of product implementation and the resulting benefit of the engagement, there was a clear indication of the intrinsic value of the community engagement among the students. One student articulates this point in an encouraging way:

One never understands the value you add to other's lives. This is exactly how I felt after this project. I was constantly concerned if we're really going to add true value to these inmates' lives. Are we going to lighten these problems or solve them? But after completion, I realised that our participation, our presence and visits were more than enough for them. Although we couldn't solve huge issues we could inspire and motivate and lighten smaller underlying problems.

It is, of course, important to acknowledge that students' perceptions cannot suffice as a reflection of the community's experience of benefit. True reciprocity requires that all parties express an experience of value. Therefore, both parties would need to be consulted to fully investigate the value of service learning projects. Carol Mitchell and Hilton Humphries (2007) question the common lack of evidence of community benefit (or lack of community voice) in service learning research. Accordingly, their research indicates that more participatory approaches should be used when engaging with communities. As such, they also advocate a justice-oriented approach to service learning. In the same vein, in any design endeavour, there are multiple stakeholders and participants. For example, both the designer and client receive benefit through financial or other incentives, while the consumer benefits from the use of the product. However, Krippendorff (2005:29) explains that technology-centered design focuses mostly on factors important to the designer and client, even though products are usually consumed and used by larger communities. In contrast, human-centered design considers the benefit to the user or community in greater depth. This becomes extremely relevant in contemporary design education settings where students need to not only develop their design, research and problem solving skills but also increase their accountability, to contribute meaningfully to the communities they engage with.

The acceptance of communities as partners is a condition that allows for reciprocity in both service learning and human-centered design approaches. Nonetheless, to reiterate, reciprocity in both contexts is ideal and a fair exchange is actually one of the biggest challenges identified in practice (Butin 2006; Drentell & Lasky 2010). Project timelines connected to curricular goals are often too limited to facilitate the longer-term investment needed to bring about real community benefit. Furthermore, the perception of benefit is also very difficult to measure, since it would be based on the opinions provided by stakeholders with vastly different expectations to begin with. This is, however, a challenge that must be consciously addressed, in order to be true to service learning and human-centered design principles.

Relevance

Relevance can be regarded as the pertinence of engagement (Butin 2003:1677). This highlights the fact that for service learning to be successful, the engagement or service provision needs to be relevant and meaningful to all the participants, including the students, the learning institution and the community. When service learning is implemented correctly, the aims of the engagement are usually developed within the context of the community. Hence, service learning calls for 'the institutional reorientation of the school/college/university in its relation to the community' (Saltmarsh 1996:15). This, in turn, helps to ensure relevance of the engagement (Butin 2003:1677; Saltmarsh 1996:15).

According to the HEQC (2006:25), the service rendered needs to be 'relevant in improving the quality oflife for the community, as well as achieving module outcomes' (Bringle & Hatcher 1996:222). These ideas resonate with Dewey's philosophy that both education and service play a mediating role in society, whereby the intention is to break down the barriers between different groups of people (distinguished by different circumstances and privileges) and to ensure that each person is 'occupied in something which makes the lives of others better worth living' (Dewey, in Saltmarsh 1996:19). In this regard, the idea of relevance extends to the pairing of the community and their needs with the needs of the students being trained in a specific discipline. These viewpoints also speak to the notion of reciprocity; hence, it must be acknowledged that even though the four Rs are discussed individually in this paper, they are interdependent.

In Frascara's (2002:35) view, human-centered design also ensures greater relevance in that it aims to rise above fads and fashions to 'penetrate all dimensions of life with a view to improving it'. Thus, Frascara (2002:34) calls for greater accountability, relevance and sustainability in contemporary design practice. The idea of design for the sake of self-expression is thus no longer considered relevant, as it does not look towards the user's needs and desires. One student clearly expressed an understanding of this:

Although we, as designers, know that we design for our clients and not for ourselves, our personal opinions and tastes always find a way to break through our concept development stages and they become represented in our designs in some or other way. For the first time however, my likes and dislikes fell away completely and gave way to those of the consumer.

Buchanan (2000) also asserts that from a human-centered design perspective, it is essential for design products to be appropriate to the situation of use. Buchanan (2001b:14) defines propriety as 'the proper mixture of emphasis on what is useful, usable, and desirable in a product'. To this end, Buchanan encourages the practice of rigorous research throughout the design process in order to ensure that design outcomes are relevant and meaningful. In keeping with the theory, it was therefore encouraging to note how one student commented in particular on how the project facilitated the development of research skills:

The value of this project to us as designers can be seen the way our process skills were challenged and developed. I think that, most of the time, we tend to not take the research part of the process seriously enough. Not only that but we also tend to consider Internet research as the primary source for idea generation and needs identification. We tend to take for granted that groundwork is already done by someone else and sitting on the Internet for us to use. This project definitely showed us the value in primary research and personal engagement with the targeted community.

Following from this, it is evident that service learning and human-centered design value appropriateness as a measure of relevance; they are both inclined towards human and environmental needs created by and/or resulting from human action. Charles Owen (2007:21) also identifies appropriateness as a measure of design. He asserts that most design solutions are contingent and interdependent on the context in which they operate and therefore, unlike science, right/wrong cannot be used as measures since they are absolute and do not lend themselves to the complex nature of design.

By highlighting the importance of truly relevant outcomes, both service learning and human-centered design approaches emphasise the value of interdisciplinary collaboration. Within contemporary communication design, in addition to working more closely with end users in the design process, designing relevant products also requires the input of experts in other disciplines, especially from the social sciences. Designers therefore need to realise the limitations of their own knowledge and work in collaboration with other key players to ensure that they employ best practice methods. These viewpoints from professional practice therefore support collaborative experiences, such as service learning, at a tertiary education level.

Reflection

As advocated by Dewey (1938), the purpose of the link between education and experience is to learn from action. Reflective enquiry is necessary to move learning 'beyond conditioning, [and] beyond the classroom' (Saltmarsh 1996:18), and to maintain the link between thought and action. Moon (1999:4) indicates that the word reflection denotes a form of mental processing and the act goes beyond mere experience to provide context and meaning for the experience, resulting in the creation of new knowledge (Butin 2003:1677). Since learning is essentially about transformation within the context of education, reflection is a valuable tool for students who are involved in service learning. One of the core characteristics of reflection is the generation of own knowledge (insight) directly tuned to practice. Another important characteristic of reflective enquiry is 'to make the connection between intent and result of conduct' (Saltmarsh 1996:18). Reflection, as a mandatory requirement of service learning, is therefore a means of transforming experience into knowledge about the module content, a more holistic understanding and appreciation of the respective field of study as well as improved personal values and social responsibility (Bringle & Hatcher 1996; Giles & Eyler 1994). In addition, reflection has the potential to influence the application of knowledge in further action and thereby have a longer-lasting and sustainable impact with a view towards creating a 'just democratic community' (Saltmarsh 1996:18). As a result, educators must ensure that there are structured opportunities to reflect during service learning projects.

Similarly, from a human-centered design perspective, the act of reflection is integral to practice. Human-centered design draws on Donald Schön's (1983) concept of the reflective practitioner and advocates that the design process is iterative in nature. Bryan Lawson (2006:299) notes that there are essentially two interpretations of reflection: reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Reflection-in-action is carried out during the teaching/learning process and reflection-on-action is done after the engagement has been completed. Reflection-in-action is meant to enhance the design process and the subsequent outcome and reflection-on-action is a means of embedding knowledge and considering the broader implications of design practice.

Continual evaluation and reflection feed back into the design cycle in order to ensure the creation of more effective products. For example, Hanington (2010:21) explains how research in human-centered design is conducted throughout the design process, in the exploratory, generative and evaluative phases. Prototype testing, as a form of reflection-in-action, is a valuable method of generating feedback that can be incorporated into another iteration of the design process, providing continuous improvement and higher levels of assurance that solutions will be appropriate and effective. It is owing to this iterative design process that Jorge Frascara and Dietmar Winkler (2008:11) prefer to use the term 'response' instead of 'solution', since they believe that design problems can be reduced but never fully solved. The preference for the word 'response' when discussing a design solution is in keeping with Herbert Simon's (1969) concept of 'satisficing', a term which refers to finding appropriate solutions as opposed to absolute ones. This more modest approach acknowledges that better responses may be achieved 'when more information becomes available, or when a more intelligent designer meets the problem' (Frascara & Winkler 2008:11). This belief therefore substantiates the need for reflection-on-action in order to advance design knowledge.

Consequently, in order for any service learning or human-centered design experiences to be meaningful and have value, embedded knowledge needs to be arrived at and this is facilitated through the practice of reflection. Zoltowski et al. (2010) support this viewpoint when they argue that students' collaboration with users is only valuable alongside reflective activities, which leads students to 'see how important knowledge of the users is and how it creates better designs'. The importance of understanding the end-user in a design process as well as the change in attitude towards a specific community through engagement is a prominent theme that emerged from the students' reflections. For example, the following reflection by a student highlights personal growth and a marked improvement in the student's attitude towards people he or she would otherwise not have engaged with:

My assumptions and beliefs has definitely changed, before I went to visit prison, I was very judgemental about prisoners, and didn't feel sorry for them at all, my view was that if they ruined someone's life, they deserve prison forever. But after the visits, I found myself feeling sorry for a murderer, seeing that he is also just a person who made a mistake.

In addition to embedding disciplinary-specific knowledge gained from the service learning activity, reflection on a more personal, civic level can be used meaningfully to learn from the community engagement experience. Through reflection activities, students gain a better understanding of their roles and responsibilities as designers to bring about positive change in society. One student describes this realisation as follows:

After completing this project I recognise how privileged I am to be completing a university education. Many do not have the opportunities I do and resort to drastic measures in order to survive. Looking into the future I feel that it is my duty to partake in community engagement projects whenever the opportunity arises. Society cannot continue to turn its back on the less fortunate. It is my responsibility as a university graduate to make small changes wherever I can.

Although many potential problems have been highlighted, through the act of reflection, failures can be transformed into stepping stones towards more respectful, reciprocal and relevant engagements in future.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The above discussion of the similarities between service learning and human-centered design indicates that the two methodologies share common ground (especially in bridging theory and practice) and that Butin's (2003) four Rs may serve as a suitable interface between the two. This article therefore suggests that, where relevant, the two methodologies can be combined to inform a new pedagogic approach of linking classroom and community in contemporary design education. The call for new and more engaged ways of teaching and learning are substantiated by a number of reasons, which are discussed briefly below. More pragmatically, a number of challenges are also highlighted with regard to the inclusion of service learning in the curriculum.

Dickson (2003:60), speaking from an architectural design position, recognises the need for new teaching methodologies by stating that an increasing number of educators are moving away from 'traditional teacher centric teaching methodologies that have focused on passive learning activities, and move toward skills that foster greater student centered inquiries in a more interactive setting'. In addition, his affirmation that the simulation of real world problems is central in design-based education substantiates the important role that experiential learning plays in educating designers. Owing to the blurring of boundaries between various design disciplines today, design educators also have the responsibility of preparing graduates for non-traditional design roles and contexts. For instance, human-centered design, as a methodology, is gaining increasing exposure as a result of global design companies, such as IDEO, which promote their Human-Centered Design toolkit, a free 'innovation guide for social enterprises and NGOs worldwide' (IDEO 2012). Students being trained in such methodologies within higher education may therefore increase their opportunities for work within a widening domain once they graduate.

Another advantage of taking learning outside the traditional classroom is that design students have a better opportunity of engaging in research. This view is supported by Buchanan (2004:37) who argues that 'design schools that prepare students for stylistic and formal expression address only a small part of the discipline of design'. Instead, he believes that the design curriculum should 'strive to integrate stylistic and formal expression with the ability to conduct user research, task analysis, and a variety of other technical activities suited to different branches of design'. Despite research being an important part of the designer's problem-solving skills set, Hanington (2010:20) has more recently argued that design students are rarely formally educated on research methodology. Christopher Crouch and Jane Pearce (2012) aim to address this need in their book, Doing research in design. Following from their argument that design research informs design for social change, institutionalising community engagement as a means to facilitate a better understanding and application of research skills by design students is of great importance.

Human-centered design principles can optimally only be taught and embedded through practical community engagement. Such experiential engagements fully immerse students in the complexity of human-centered design problems where there are no easy solutions. By allowing engagement with communities as part of the curriculum, service learning modules may provide a valuable platform for teaching human-centered design as well as nurturing civic competencies. William Drenttel and Julie Lasky (2010) also support the need for students to learn the necessary 'tools and training to explore and address social-design problems', and they note that it 'has been a growing mission of educators'.

As noted earlier, despite its value, human-centered design projects do, however, pose particular challenges, specifically in terms of providing equally beneficial outcomes to both students and the community (Mitchell & Humphries 2007). This concern was also raised at the Winterhouse Symposium on Design Education and Social Change held in 2010, where Jamer Hunt questioned which participants were being served foremost, the students or the target community (Drenttel & Lasky 2010). He expressed his frustration 'at the superficiality of a lot of projects that often end up making students feel better about themselves with no impact' (Hunt, in Drenttel & Lasky 2010). It is in addressing this challenge that service learning may have a significant role to play in terms of promoting and moving towards mutually beneficial engagements.

Another challenge of service learning relates to the duration of such projects. Even though service learning is curriculum-related community engagement where students receive credits for the completion of their modules, it is not a practice that dominates most curricula. As such, it is often limited and often restricted to one module per year or sometimes one module per course. The fact that service learning is limited throughout a course is not in keeping with Dewey's belief that experiential learning opportunities should be continuous and supported by previous experiences. A similar viewpoint is shared by Robert Putnam (2000) who, when speaking about building social capital, states that 'episodic service has little effect'. This stance has implications for the community participants too; they should not feel used by the students during the service learning project. Follow-ups are necessary to ensure the sustainability of the engagement because ultimately, the aim is for short-term project outcomes to affect long-term social change.

Perhaps the most difficult challenge of all is to reconcile different attitudes towards experimentation. From a design education perspective in particular, service learning with its rigid emphasis on measurable, beneficial outcomes for all stakeholders, does not allow for nurturing an experimental attitude, which is considered vital in most design curricula. The highly experimental and therefore somewhat unpredictable nature of design practice on an educational level may therefore be at odds with service learning methodology, which measures the success of the project along different criteria.

Despite some of these challenges, considering that '[e]ngagement between higher education and other societal sectors is a key theme in higher education discourse in South Africa, as it is in other countries' (O'Brien 2009:29), it is unlikely that design educators will be met with resistance for looking towards service learning to inform the implementation of more formalised human-centered design projects in their curricula. Ultimately, the aim is for the scholarship of engagement to 'direct the work of the academy toward more humane ends' (Cox 2006:123-124) and for 'humane life' to be the maximum aspiration of design practice as well as any other intellectual effort (Frascara 2002:39).

REFERENCES

Academic Service-Learning. General information (Brochure). 2009. Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

Angotti, T., Doble, C.S. & Horrigan, P (Eds.). 2012. Service-learning in design and planning: Educating at the boundaries. Oakland: New Village Press. [ Links ]

Boyer, E.L. 1996. The scholarship of engagement. Journal of Public Service and Outreach 1(1):11-20. [ Links ]

Bringle, R.G. & Hatcher, J.A. 1996. Implementing service learning in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education 67(2):221-239. [ Links ]

Buchanan, R. 2000. Human dignity and human rights: Toward a human-centered framework for design. Retrieved from http://www.defsa.org.za/request.php795 (accessed 24 May 2012).

Buchanan, R. 2001a. Human dignity and human rights: Thoughts on the principles of human-centered design. Design Issues 17(3):35-39. [ Links ]

Buchanan, R. 2001b. Design research and the new learning. Design Issues 17(4):3-23. [ Links ]

Buchanan, R. 2004. Human-centered design: Changing perspectives on design education in the East and West. Design Issues 20(1):30-39. [ Links ]

Butin, D.W. 2003. Of what use is it? Multiple conceptualizations of service learning within education. Teachers College Record 105(9):1674-1692. [ Links ]

Butin, D.W. 2006. The limits of service-learning in higher education. The Review of Higher Education 29(4):473-498. [ Links ]

Colby, A., Ehrlich, T., Beaumont, E., Rosner, J. & Stephens, J. 2000. Higher education and the development of civic responsibility. In T. Ehrlich (Ed.), Civic Responsibility and Higher Education, xxi-xliii. Phoenix: Oryx. [ Links ]

Constandius, E. & Rosochacki, S. 2012. See Kayamandi see yourself- social responsibility and citizenship project for visual communication design. Stellenbosch: Sun Publishers. [ Links ]

Cox, D.N. 2006. The how and why of the scholarship of engagement. In SL. Percy, NL. Zimpher & MJ. Bolton (Eds.), Creating a new kind of University. Institutionalising community-university engagement, 122-135. Massachusetts: Anker. [ Links ]

Crouch, C. & Pearce, J. 2012. Doing research in design. New York: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. 1938. Experience and education. New York: Collier Books. [ Links ]

Dickson, KA. 2003. Interdisciplinary design education through service learning. Pomona Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. Available at: http://www.csupomona.edu/~jis/2003/Dickson.pdf (accessed 8 June 2012).

Drentell, W. & Lasky, J. 2010. Winterhouse First Symposium on Design Education and Social Change: Final Report. Retrieved from http://changeobserver.designobserver.com/feature/winterhouse-first-symposium-on-designeducation-and-social-change-final-report/22578/ (accessed 8 June 2012).

Frascara, J. 2002. People-centered design: Complexities and uncertainties. In J. Frascara (Ed.), Design andthe social sciences: Making connections, 33-39. London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Frascara, J. & Winkler, D. 2008. Jorge Frascara and Dietmar Winkler on design research. Design Research Quarterly 3(3):1-13. [ Links ]

Furco, A. 2011. Service-learning: A balanced approach to experiential education. Retrieved from http://educacionglobalresearch.net/wp-content/uploads/03-Furco-1-English1.pdf (accessed 8 June 2012).

Giles, D.E. & Eyler, J. 1994. The theoretical roots of service-learning in John Dewey: Toward a theory of service learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 1(1):77-85. [ Links ]

Hanington, B. 2003. Methods in the making: A perspective on the state of human research in design. Design Issues 19(4):9-18. [ Links ]

Hanington, BM. 2010. Relevant and rigorous: Human-centered research and design education. Design Issues 26(3):18-26. [ Links ]

Higher Education Quality Committee (HEQC). 2006. Service-learning in the curriculum: A resource for higher education institutions. Pretoria: The Council on Higher Education. [ Links ]

IDEO. 2012. Human-centered design toolkit. Available at http://www.ideo.com/work/human-centered-design-toolkit/ (accessed 17 July 2012).

Junginger, S. 2012. The Chile miner rescue: A human-centered design reflection. The Design Journal 15(2):169-184. [ Links ]

Kolb, D.A. 1984. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Krippendorff, K. 2005. The semantic turn: New foundations for design. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [ Links ]

Lawson, B. 2006. How designers think. The designprocess demystified. Fourth Edition. Burlington: Architectural Press. [ Links ]

Le Grange, L. 2007. The 'theoretical foundations' of community service-learning: From taproots to rhizomes. Education as Change 11(3):3-13. [ Links ]

Mitchell, C. & Humphries, H. 2007. From notions of charity to socialjustice in service-learning: The complex experience of communities. Education as Change11(3):47-58. [ Links ]

Moon, J. 1999. Reflection in learning andprofessional development. London: RoutledgeFalmer. [ Links ]

O'Brien, F. 2009. In pursuit of African scholarship: unpacking engagement. Higher Education 58:29-39. [ Links ]

Oosterlaken, I. 2009. Design for development: A capability approach. Design Issues 25(4):91-102. [ Links ]

Owen, C. 2007. Design thinking: Notes on its nature and use. Design Research Quarterly 2(1):16-27. [ Links ]

Percy, S.L., Zimpher, N.L. & Brukardt, M.J. (Eds.). 2006. Creating a new kind of university. Institutionalising community-university engagement. Bolton, Massachusetts: Anker. [ Links ]

Putnam, R.D. 2000. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Saltmarsh, J. 1996. Education for critical citizenship: John Dewey's contribution to the pedagogy of community service learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 3(1):13-21. [ Links ]

Sanders, E. 2002. From user-centered to participatory design approaches. In J. Frascara (Ed.), Design and the social sciences: making connections, 1-8. London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Sanders, E. & Stappers, P.J. 2008. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 4(1):5-18. [ Links ]

Schön, D. 1983. The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Shea, A. 2012. Designingfor social change: Strategies for community-based graphic design. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. [ Links ]

Simon, H. 1969. The sciences of the artificial. Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Yates, M. 1999. Community service and political-moral discussions among adolescents: A Study of a mandatory school-based program in the United States. In M. Yates & J. Youniss (Eds.), Roots of civic identity international perspectives on community service and activism in youth, 16-31. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Zoltowski, C., Oakes, W. & Chenoweth, S. 2010. Teaching human-centered design with service-learning. Proceedings of the Annual American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) Conference, Louisville, USA.