Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Education as Change

On-line version ISSN 1947-9417

Print version ISSN 1682-3206

Educ. as change vol.20 n.1 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/558

ARTICLES

'We are history in the making and we are walking together to change things for the better': Exploring the flows and ripples of learning in a mentoring programme for indigenous young people

Sarah O'SheaI; Samantha McMahonII; Amy PriestlyIII; Gawaian Bodkin-AndrewsIV; Valerie HarwoodII

IUniversity of Wollongong Email: saraho@uow.edu.au

IIUniversity of Wollongong

IIIAustralian Indigenous Mentoring Experience

IVMacquarie University

ABSTRACT

This article explores the unique mentoring model that the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience (AIME) has established to assist Australian Indigenous young people succeed educationally. AIME can be described as a structured educational mentoring programme, which recruits university students to mentor Indigenous high school students. The success of the programme is unequivocal, with the AIME Indigenous mentees completing high school and the transition to further education and employment at higher rates than their non-AIME Indigenous counterparts. This article reports on a study that sought to deeply explore the particular approach to mentoring that AIME adopts. The study drew upon interviews, observations and surveys with AIME staff, mentees and mentors, and the focus in this article is on the surveys completed by the university mentors involved in the programme. Overall, there seems to be a discernible mutual reciprocity inherent in the learning outcomes of this mentoring programme; the mentors are learning along with the mentees. The article seeks to consider how AIME mentors reflect upon their learning in this programme and also how this pedagogic potential has been facilitated.

Keywords: indigenous education, mentoring, indigenous young people, pedagogic flows, youth and learning

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, the Australian university population has grown significantly. One indicator of this growth over time is found in national studies of students' commencement rates. In the decade between 1994 and 2004, the total number of commencing university students in Australia grew by 36 per cent. The most recent statistics from the Commonwealth of Australia Department of Industry (2014) reflects this trend; the total number of students commencing university students increased by 4 per cent to 509 766 in 2012 compared with the same period in 2011.

The Australian university student population is now not only larger but also more highly diverse than ever. Yet, the increasing numbers and diversity of university students do not necessarily equate to more equity of access. Examining entry statistics reveals how comparable levels of access have not been possible for all student cohorts and certain sections of the community continue to be under-represented in higher education (James 2008). The Review of Australian Higher Education, led by Denise Bradley (Bradley, Noonan, Nugent & Scales 2008), identifies that students from remote areas, Indigenous students, and those from low-socio-economic (LSES) backgrounds remain the most 'under represented' in the higher education sector (Bradley et al. 2008:10). While research has indicated that once low SES students enter university, their success rates are similar to their high SES colleagues, this is not the case for Indigenous students (James 2008).

This finding by James (2008) is of considerable concern as an increased quality of education has often been cited as one of the most critical tools for combating a wide range of inequities (e.g., health, socio-economic status, employment) Indigenous Australians have endured (Bodkin-Andrews & Carlson 2013). Critically, researchers need to acknowledge the negative legacy that both colonisation and the resulting educational practices have had upon the cultural, family, and personal wellbeing of Indigenous Australians. The long history of racist educational policies, programmes, and attitudes within Australia have not only alienated Indigenous Australians, but also sought to erase their very identities and epistemologies (Beresford 2012; Bodkin-Andrews & Carlson 2013).

Indigenous people remain the most educationally disadvantaged in Australia, as this cohort does not have parity of educational access and participation. While the retention of Indigenous school students (7-12 years) has increased across the decade, from 32.1 per cent in 1998 to 47.2 per cent in 2010, such impressive increases are not apparent in either the TAFE or university sector (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision (SCRGSP) 2011). According to Devlin (2009), while there are higher proportions of Indigenous students attaining school completion, levels of tertiary education participation remain consistently low. The number of Indigenous students who leave university prematurely is almost double that of non-Indigenous students and hovers between 35-39 per cent (ACER 2010). Examining these departure statistics powerfully highlights the significance of Indigenous student attrition. Each year in the 2001-2006 period, approximately 4 000 Indigenous students commenced university but only 1 000-1 200 succeeded in completing a degree during the same period (ACER 2010).

The reasons Indigenous students depart the tertiary sector are manifold, including lower levels of educational readiness and limited financial resources, but James (2008) cautions against an oversimplification of the reasons for attrition. Distance is one key inhibiting factor for Indigenous students from remote and rural areas, as attending university requires mobility or movement. Holt (2008) points out that 'mobility' is an ontological absolute for rural young people contemplating on-campus university attendance. This is an embodied move that not only necessitates geographical shifts but also shifts in identity and community connection, some of which may be difficult or complex to achieve. The complex nature of decision-making around university attendance for Indigenous students is echoed by Anderson, Bunda, and Walter (2008:2) who argue that attending university for this cohort is 'not simply a matter of deciding "yes" or "no" ... such choices are socially patterned' . Equally, for those students who may be the first in their community or family to attend university, the challenges associated with this transition are increased as students may find themselves expected to 'navigate' the culture of this tertiary experience in isolation as educational pioneers (Harrell & Forney 2003:155). Many of the obstacles encountered by Indigenous students remain largely invisible, but these and other cultural and personal considerations all play a powerful role in decisions about attending and persisting at university.

Patterns of educational disadvantage within the tertiary sector are gradually beginning to shift; the Commonwealth of Australia Department of Industry (2014) is now reporting an increase in Indigenous student numbers across most broad fields of university education, although students who self-identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander still only comprise 1 per cent of all enrolments in 2012. Despite reported improvements, this arguably remains a significant under-representation considering that the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 3 per cent of the total Australian Population (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2013). It should also be noted that more recent, and successive Australian governments have emphasised the need for redressing the long-term inequities in education between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, yet scholarly criticism suggests that these macro policy agendas have been too strongly embedded within discourses of disadvantage and deficit (Altman, Biddle & Hunter 2009; Irabinna-Rigney 2011). Put simply, it may be argued that overarching policy approaches have ignored a growing body of research articulating positive programmes encouraging Indigenous student successes across all levels of education (Ainsworth & McRae 2009; Bodkin-Andrews Harwood, McMahon & Preistley 2013; Sarra 2011; Yeung, Craven, Wilson, Ali & Li 2013). What is notable about such research is the overarching emphasis on cultural respect, integration, and inclusion that is relevant to the diverse Indigenous communities they have been situated within.

Such research has often been led by Indigenous scholars who have revealed that within academia, there is a strong and positive knowledge base that can be tied to a greater understanding and application of Indigenous ways of being and knowing (e.g., Martin 2008; Moreton-Robinson 2013; Tuhiwai Smith 2012). It must be repeatedly emphasised that Indigenous knowledge systems in Australia have both been continually developing and evolving over a near immeasurable number of generations (Fredericks 2013; Walter & Andersen 2013). For this reason, it is critical that all researchers seeking to understand Indigenous education recognise, respect, and incorporate findings emerging from Indigenous Research Methodological standpoints (Foley 2003; Moreton-Robinson 2013).

One of the strongest themes to emerge from Indigenous Research Methodologies is that the often cited inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians must not be considered as due to the deficit-orientated 'Aboriginal problem', but rather that the inequities must be more carefully understood by moving beyond culturally incomplete Western-based epistemologies (Carlson 2013; Walter & Andersen 2013). Effective educational research and reform must be driven within a foundation drawn from Indigenous perspectives and practices that respect the dynamic and unique relations Indigenous Australians hold with their culture, community, country, traditions and learnings (Martin 2008; Trudgett 2013).

The focus of this paper is on an Indigenous Australian-led programme designed to combat the repeatedly cited unacceptable levels of educational participation outcomes for Indigenous Australian students. The Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience (AIME) is an educational mentoring programme designed to improve high school completion rates of Australian Indigenous students and transition 100 per cent of their Year 12 students into university, further education, or employment. AIME has experienced great success for its mentees (details are outlined in the next section) and has subsequently grown 'exponentially'. In 2005, its first year of operation, the programme comprised 25 mentors from University of Sydney pairing up with 25 mentees (Indigenous high school students from one local high school). Eight years later, in 2013, 1 066 university students, at 14 universities and 23 campuses across the five states of Australia (see Table 2), mentored 2 789 mentees (AIME, 2014a) in school years eight to twelve, and AIME's current goal is to be reaching 6 000 students and 2000 mentors nationally by 2016 (AIME 2014b:para. 2).

Mentoring literature has identified the benefits of participating in these programmes for the mentees, particularly those from disadvantaged groups. These benefits include: increasing self-esteem, self-confidence and self-efficacy; decreasing stress; increasing satisfaction and retention due to mentor encouragement (where not provided at home); developing skills; decreasing absenteeism; and increasing grades (in secondary school) (Calton 2010; Rogers 2009; Stolberg 2011). The benefits to mentors are largely defined in terms of tangible rewards such as receiving credit for volunteer mentoring on performance reviews; the acquisition of employability skills such as leadership and some personal benefits, such as increased self-esteem and the good feelings associated with helping others (Owens 2006; Zeind et al. 2005). This article builds on this literature to consider the knowledge growth for the mentors involved in this programme and how this impacted their perceptions and worldview.

In the AIME programme there is a significant departure from the predominant view that methodical matching of mentees and mentors is important to successful mentoring relationships. For example, a number of studies have underscored the importance of attention to gender, ethnicity and common interests in matching mentor with mentee (Brown & Hanson 2003; Valeau 1999; Zeind et al. 2005). Contrary to this type of approach, in terms of the predominant view of a necessary parity of 'ethnicity', AIME mentees and mentors are largely from different cultural heritages. While all the AIME mentees are young Indigenous high school students, the university student mentors are predominantly non-Indigenous. This is perhaps to be expected given the low rates of participation by Indigenous Australians in university education (described above). Nationally, in the 2013 cohort, 90.5 per cent of mentors were non-Indigenous. This is reflected in the mentor survey, where 91.5 per cent of the participants identified as non-Indigenous with mentors being derived from all disciplines across each university site. Further detailed mentor and mentee demographics are available from the AIME Annual Report (AIME 2014a).

Drawing on data generated from surveys conducted with AIME mentors, this article will explore the particularities of the AIME approach to mentoring and how this has impacted all parties. We argue that the AIME mentoring model moves away from 'expert mentor/inexpert mentee' relationship and creates a pedagogic flow that enables reciprocal learning and growth. The following sections explore how AIME has evolved and the particular approach to mentoring that has been developed before presenting the results from a survey conducted with 178 mentors after completion of the programme in 2013.

EXPLORING AIME'S MENTORING MODEL

The AIME programme has a twofold focus of social support using mentors as role models and academic support via tutors squads, where mentors volunteer to assist with homework and school tasks. Mentoring is voluntary with university students recruited from a range of disciplines and programmes, at all stages of their university studies (they range from first year undergraduate to post-graduate students). Although AIME recruits some mature-aged students as mentors, the mentors are predominantly school leavers and young people under the age of 25.

AIME was established by a group of university students. The founder, Jack Manning Bancroft, is one of the youngest CEOs in Australia and the organisation is characterised by a young and energetic spirit. AIME has drawn extensively upon social media and have caught the public imagination with fundraisers such as 'National Hoodie Day' and 'Strut the Streets' (in swimwear). In addition to a growing Australian national presence, AIME has developed a very structured approach to mentoring as outlined in the next section.

The AIME framework

AIME initially used a 1:1 mentoring structure in their Core Program, where Indigenous high school students would visit a university campus for up to 21 one-hour mentoring sessions throughout the school year. Although five Core Programs were in operation in 2013, (during the time of data collection), AIME's most common mode of programme delivery is the Outreach Program. AIME operated 34 outreach programmes across Australia in 2013. In this programme, the mentor to mentee ratio is closer to 1:3. The shift to the outreach model was to facilitate AIME's goal for reaching as many Indigenous high school students as possible as well as offering an alternate mode of delivery.

The Outreach Program delivers the same content as the Core Program, however, to address issues of geography and travel times, day-long sessions are offered throughout the school year to replace the weekly hour long sessions. This means that schools further afield, up to two hours away, are able to participate as they can take their students to the university campus for each of the programme days.

We know AIME works ...

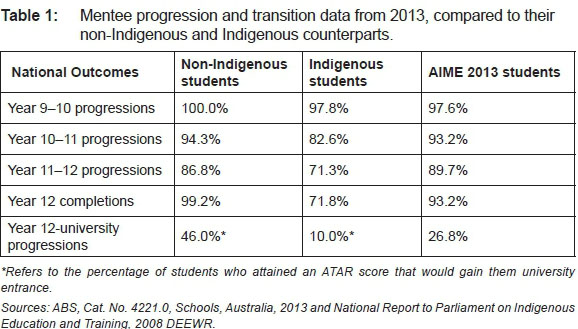

The impact of the AIME Program has been measured year on year within the organisation with grade progressions and Year 12 completions statistics published in their Annual Reports. AIME has reported four consecutive years of school progression and completion results that are significantly higher than the national Indigenous statistics. In 2013, the Year 11-12 progression rate for AIME students was 89.7 per cent, which was significantly higher than the national Indigenous average of 71.3 per cent and also higher than the national non-Indigenous rate of 86.8 per cent. Table 1 indicates the rate of progression across school years, the percentages of students who complete the final year of high school (Year 12) as well as those students who achieve a final score that would make them eligible for university.

Collectively, the statistics indicate that over 81 per cent of non-Indigenous students progress through to Year 12 compared with 41 per cent of Indigenous students but, for those affiliated with AIME, this progression increases to 76 per cent. The positive impact of AIME is repeated when Year 9-university progression rates are considered with 37.4 per cent of non-Indigenous students achieving a university entrance score, compared with 4.1 per cent of Indigenous students, again this figure increases to 20.4 per cent of those students involved in the AIME programme (AIME 2014a).

In order to better understand both the effects of AIME participation and the possible long-term repercussions on the lives of participants, the organisation commissioned two key independent research projects. An evaluation into the effectiveness of the AIME Program and the associated mentee outcomes (Harwood et al. 2013) was completed and published in March 2013. On the basis of findings from survey, observation, document review, and interview data, Harwood et al. (2013) found that the AIME Program (and particularly the AIME outreach model) positively impacted mentees. Particularly, the evaluation reports that AIME's outreach model of delivery positively impacted mentees' (i) strength and resilience; (ii) pride in being Indigenous; (iii) making strong connections with Indigenous peers, role models and culture; (iv) aspirations and engagement for finishing school; (v) aspirations for continuing further study; and, (vi) school retention and progression rates (Harwood et al. 2013).

In addition, a pilot quantitative study by Bodkin-Andrews et al. (2013) found that Indigenous students participating in AIME were significantly more likely to aspire to complete high school (1.87 times more likely) and attend university (1.30 times more likely). In addition, not only did the AIME students have a higher sense of school self-concept and school enjoyment when compared with the non-participating students, but their stronger sense of school self-concept was found to have a higher level of predictive power over Year 12 and university aspirations (this was over and above the effects of the students' gender, age, home educational resources, and whether their parents went to university). These findings led the researchers to conclude that AIME actively promotes a more meaningful sense of confidence in education for Indigenous students. The programme also succeeds in building levels of confidence among participants, as well as understandings of self and others within a culturally appropriate environment. The ways in which such development manifests for mentors are the main thrust of this paper.

The strengths of AIME's outcomes were also backed up by an economic evaluation conducted by KPMG, which was completed and published in December 2013. Working on the economic premise that higher levels of education result in higher paid positions of employment, KPMG (2013:3) found that: 'An AIME student that completes a university degree can be expected to earn up to $332,000 more over their lifetime compared to an Indigenous student that does not complete high school.' Moreover, KPMG (2013:4) calculated that AIME generates impressive benefits for the Australian economy, 'for each $1 spent, $7 in benefits is generated for the economy'. Both of these evaluations reported AIME's outstanding success in their related fields of enquiry.

Nested in this mentoring programme that has successful outcomes for both its mentees and the Australian economy are strong indications of significant benefits for mentors. Benefits of mentoring, particularly the mentors' 'learning' in this context, are significant but, thus far, remained undertheorised. This article begins to address this gap in the mentoring research.

The AIME mentoring model

The AIME approach to mentoring deviates from more traditional mentoring programmes in a range of ways. AIME grew from the grass-roots level, was founded by young people and is Indigenous led. At the time of its inception, there was minimal available research on best practice for mentoring Australian Indigenous high school students, however, there was a need to raise school attendance and completions levels.

Mentoring is not a new concept for Indigenous Australians. Within this cultural context, there has always been an emphasis on connecting young people with significant others such as the cultural tradition of guidance and the sharing of wisdom through Elders (Walker 1993). With this in mind, the AIME Program fits well with Indigenous teaching and learning styles. For example, AIME is not only focused on ensuring the academic success or employability of the mentee. In line with Indigenous ways of learning and teaching, it is seen as an opportunity to share personal stories, past experiences, life lessons and traditional cultural teachings. The AIME Program contests the current deficit in educational outcomes by providing Indigenous high school students with a culturally appropriate mentorship programme with curricular activities designed especially with Indigenous perspectives in mind. The curriculum has been specifically designed for Indigenous Australian high school students by Indigenous AIME staff. All the AIME presenters who facilitate the sessions are Indigenous role models and the mentors are mostly non-Indigenous university students (76 Indigenous Mentors in the cohort of 1 070 in 2013).

AIME recruits mentors from the various university sites that the programme currently operates and in 2014 to date, the programme has recruited 1 390 mentors, a figure that will continue to grow. Of these, most were female (n=1 019) and from all fields of university study but predominantly studying at an undergraduate level (n=1 266). Recruitment is conducted via lecture presentations, college visits, o-week stalls, social media, and also by word of mouth. Potential mentors are invited to apply online and through this application provide details of why they wish to participate in the programme as well as explain what makes a good AIME mentor and why they should be selected. All applications are assessed by the AIME organisation and potential applicants are then contacted by phone for a further short interview. If deemed suitable for the programme, mentors are then required to complete two online training sessions on Australian Indigenous history and child protection and policy, respectively. This online training is complemented by on-campus training sessions that include topics such as cultural identity, mentoring techniques and also, details about the programme and associated responsibilities. However, training and learning about the programme and mentoring is an ongoing endeavour throughout participation, AIME mentors both engage in pre- and post-debriefing sessions, where they are encouraged to reflect upon their experiences during the day, their anxieties or concerns as well as provide feedback on what they consider is working or not. AIME's organisational culture can be likened to what Cameron and Quinn (2011) term a 'clan culture, hence becoming an AIME mentor is not simply about attending sessions with mentees but instead through a range of social networking strategies and also, the AIME hoodies and caps, the organisation seeks to develop a collectivity based on shared goals, values and beliefs. This collectivity is further embedded within the training, which operates 'like an extended family. Leaders are thought of as mentors and perhaps even as parent figures .... Commitment is high. The organization emphasizes the long-term benefit of individual development, with high cohesion and morale being important' (Cameron & Quinn 2011:48).

or not. AIME's organisational culture can be likened to what Cameron and Quinn (2011) term a 'clan culture, hence becoming an AIME mentor is not simply about attending sessions with mentees but instead through a range of social networking strategies and also, the AIME hoodies and caps, the organisation seeks to develop a collectivity based on shared goals, values and beliefs. This collectivity is further embedded within the training, which operates 'like an extended family. Leaders are thought of as mentors and perhaps even as parent figures .... Commitment is high. The organization emphasizes the long-term benefit of individual development, with high cohesion and morale being important' (Cameron & Quinn 2011:48).

While the survey data reported in this article did not explicitly gather data on mentors' motivations for joining AIME, in previous research (O'Shea, Harwood & Kervin 2011) mentors identified how involvement in the AIME programme provided gain in personal/professional qualities, including leadership, coaching and personal confidence. However, one of the most cited reasons for participating in the programme related to a desire on the part of the individual to engage or connect with community. This not only included local Indigenous communities but also the university community participating in the AIME programme perceived as a means to meet other students from across discipline areas and fields (O'Shea, Harwood, Kervin & Humphry 2013).

About the study

The study reported in this article grew from a research partnership between AIME and the University of Wollongong that was established in 2010. The main objective of this partnership has been to explore how AIME engages and supports Indigenous young people to complete their high school education and also consider further learning as a viable option. Particularly, there is a mutual desire to rigorously theorise, using empirical material, the AIME model of mentoring. This is because, although it is a very successful mentoring programme, insofar as it positively impacts the Indigenous mentees' rates of school completion and transition to university, further education and employment, it does not neatly map against existing mentoring and coaching models. The research reported here is nested within this research partnership. This part of the research was funded by Commonwealth of Australia Department of Industry and took place immediately following the 2013 AIME mentoring programme.

The focus survey for this paper is the AIME post-programme mentor survey. In 2013, 178 AIME mentors completed this survey online via Survey Monkey. In total 171 respondents indicated consent for AIME to share their responses with UOW researchers and after removing surveys that were incomplete, a total of 129 surveys were analysed for this article. The 129 survey respondents comprised 118 non-Indigenous and 11 Indigenous university mentors. These mentors were from 13 different university sites across Australia. A breakdown of number of mentor respondents by state and university is offered at Table 2.

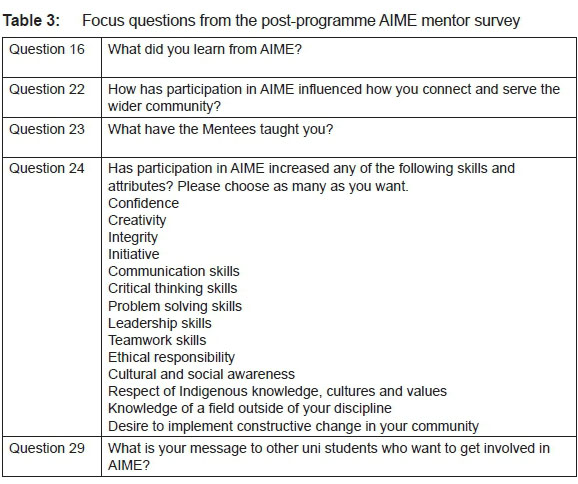

The survey included a total of 31 question items that explored various facets of the programme and the mentors' perceptions of participating. The analysis of survey data presented here focuses on five key questions from the survey. These five questions were targeted because, considered together, they generated a rich picture on the mentors' self-reported learning from their AIME experience. None of the remaining 26 questions spoke to this theme, rather they comprised seven AIME quality control feedback questions; six questions measuring interest in and garnering ideas for developing AIME as an accredited university subject; five demographic questions; four closed questions regarding ranking personal skills (e.g. communication skills); four questions pertaining to different issues of consent for participation in the research project. The five survey questions that informed this article regarding the mentors learning in AIME are outlined in Table 3.

Data from the surveys was imported into NVivo 10 and the qualitative comments were inductively themed. Axial coding was then conducted to provide insight into how responses related to the mentors' cultural backgrounds, gender and mentoring experience. In addition, frequency counts were conducted on the closed items to generate descriptive statistics.

The impacts of AIME mentoring on the mentors

Our findings reveal that exceptional mentor learning is occurring in the AIME programme, with analysis indicating that mentor learning occurs in three key ways. Firstly, their learning is described to be of exceptional scale. Here the case is made that the mentors are often learning 'more' than the mentees. Secondly, the mentors' learning is characterised as exceptional due to the importance of its content. Much of the mentors' learning centred on developing knowledge and appreciation of Indigenous Australian culture, a growing awareness of social injustices experienced by Indigenous Australians and a move away from prior knowledge characterised by racist stereotypes. Thirdly, what is both surprising and exceptional, are the mentors' reports of how this new knowledge is being applied to benefit the wider community, via both the changed nature and capacity of their volunteer work and their proactive attempts to remedy racism in their professional and personal lives.

'Mentoring as learning' in the AIME Program

That mentors benefit and learn from mentoring is not a new idea (Beltman & Schaeben 2012), but the argument that mentoring can be construed primarily as a culturally enriching learning activity, on the other hand, is largely unexplored and undertheorised. In the 2013 post-programme mentor survey, respondents indicated how their learning was largely about Indigenous culture.

An initial indicator of this step-down from position of 'mentor as teacher' is the mentors' awareness that they mentor at AIME programmes within a relationship characterised by reciprocal learning with the mentee. For example, one respondent explained: 'You get to know these young people and they are as much your mentors as you are theirs' (Q291 non-Indigenous mentor); while another describes mentoring as 'a worthwhile experience. You will learn just as much from the students, as they will learn from you' (Q29, non-Indigenous mentor).

While the above quotations recognise the reciprocity of pedagogic flows as central to the mentoring relationship in AIME, what is striking is that the mentors typically positioned themselves as learning 'as much' as, if not 'more than', the mentees. Indeed, the survey data demonstrated that the mentors frequently equated mentoring with learning and being taught:

You learn more experiencing the program first hand than you would having a uni lecturer tell you (Q29 non-Indigenous mentor).

[Y]ou will learn greater respect for what the Aboriginal community is achieving under its own initiative. And you will benefit greatly by enjoying the privilege of being included in the Aboriginal community for a day, absorbing the beautiful culture with its wit, playfulness, passion for survival and brotherly/sisterly welcome (Q29 non-Indigenous mentor).

Do it. We can't learn enough about Indigenous Australians and their culture and how to work more positively together (Q29 non-Indigenous mentor).

They [the mentees] most definitely have taught me a lot (Q23 Indigenous mentor).

These and other quotations establish that a great amount of 'learning' is happening for the AIME mentors but it is important to consider what is being learnt. In educational contexts, learning is typically construed and deconstructed in relation to syllabi and graduate quality statements as skills and knowledge (and sometimes 'values'). In recognising this, the AIME survey quantified some possible learning outcomes for mentors in terms of skills and attributes. Question 24 of the survey was a multi-response question: 'Has participation in AIME increased any of the following skills or attributes?'2

Table 4 points to multiple learning outcomes for mentors. What is striking about this data is the coherence of 'learning' from this cohort (over 80% of the mentors reported learning the first and second ranked outcomes). The coherence is striking given that the learning of mentors is not usually the focus of mentoring programmes. While there is a component of explicit teaching from AIME for the mentors in the form of ongoing mentor training, there has been little recognition in mentoring literature of the reciprocal learning relationships that are indicated by these survey responses.

Learning about Indigenous culture

Analysis of the qualitative data demonstrates that the scope, depth and impact of the mentor learning move it beyond 'incidental'. As described above, this article seeks to better understand the top three types of mentors' learning (as per Table 4). We analysed the qualitative responses to consider what it means for mentors to report increased 'cultural and social awareness', 'respect of Indigenous knowledge, cultures and values', and 'desire to mplement constructive change in one's community'.

Overwhelmingly, throughout the survey responses, the most frequently discussed 'learning' from mentoring was identified as gaining new understandings of and appreciation for Australian Indigenous cultures, history and peoples. Interestingly, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous mentors reported this increase in knowledge and understanding:

[I learned] [h]ow to work in a culturally sensitive manner and the importance of learning and understanding the true history of Australia (Q16 non-Indigenous mentor).

I learned more about myself, which was surprising. I expected this experience to be of benefit to the kids but I found that there is so much more to learn about myself and my own culture (Q16 Indigenous mentor).

Of note here is the fact that learning about Indigenous culture and history was not only fuelled by the curiosity of the 'other' (i.e., from the non-Indigenous mentors). Apart from the creation of new understandings regarding Indigenous culture and history, there was extensive comment on the AIME Program's capacity to transform existing knowledge of Indigenous Australia. This finding is particularly encouraging as numerous Indigenous scholars have highlighted the need to break down preexisting Eurocentric representations of Indigenous Australians, and to be more receptive to the unique histories and cultures of Indigenous Australians, not only within educational and learning initiatives (Price 2013; Yunkaporta & Kirby 2011), but across a diversity of disciplines (Dudgeon & Kelly 2014; Walter & Andersen 2013).

Participating in the AIME Program also impacted mentors' learning by effectively supplanting their existing understandings of Indigenous culture and people with new knowledge. Particularly, the mentors 'unlearned' racist knowledge and stereotypes of Indigenous persons. Overall this type of learning for mentors in the AIME Program was neatly summarised by one Indigenous mentor in her message to future mentors, who explained how participating in AIME 'really breaks down some of the misconceptions that people have about Indigenous culture' (Q29).

For the non-Indigenous mentors, this deconstruction of misconceptions was variously evidenced in the survey data. Typically, this was presented as an increased awareness of social justice issues and empathy for the difficulties faced by young Indigenous Australians:

Being more aware of the hardships faced by Indigenous kids and wanting to change people's attitudes and empower these guys to be proud Indigenous superstars in their community (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

I guess I just see two sides of the story now, and have more awareness of how people are treated (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

What didn't I learn? The one thing that sticks out the most for me was discovering just how amazing the AIME kids were, and there [sic] aspirations to achieve more (Q16 non-Indigenous mentor).

Occasionally, mentors explicitly recounted an overt turnaround from understanding Indigenous Australians through the lens of racist stereotyping:

That not all Aboriginal people follow the no job, drinking stereotype (Q23 non-Indigenous mentor).

It opens your mind and blows past all the preconceived, media driven notions you have of The First Peoples (Q29 non-Indigenous mentor).

It really opened my eyes! I never considered myself a racist person but I was shocked at how little I knew about the wonderful cultures of the ATSI3 [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander] people ... it was a humbling experience (Q22 non-Indigenous student).

While such accounts of eye and mind opening learning are incredibly powerful, they were reasonably rare (n=12). More often mentors expressed their unlearning of negative and racist stereotypes as discernable shifts to non-judgement of Indigenous persons:

The AIME experience reminded me to respect all people, all ages, all backgrounds. And also reminded me to connect by listening well and not judging (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

It makes me more conscious about my actions and the way I behave in relation to other cultures (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

One aspect of moving away from 'judgement' towards non-judgemental understandings of Indigenous cultures and peoples related to revising perceptions of 'Aboriginalism' (Mackinlay & Barney 2008). This is the name for the process of othering Indigenous Australians based on essentialist stereotypes of what makes a 'real' Aboriginal (lives in the bush, plays didgeridoo, does traditional dancing, etc.). That is, there was a collection of statements that demonstrated an abandonment of understanding of Indigenous people in terms of stereotypes informed by skin colour, social class and living environment. This collection of statements can be analysed across aesthetic and temporal axes.

This shift from knowledge resting in perceptions of the 'other' to knowledge grounded in diversity of Indigenous people's experiences was evidenced in un/ learning stereotypes that all Indigenous people are defined by skin colour. Some mentors demonstrated an abandonment of racialised stereotyping based upon preconceived notions of 'racial types'4. Such comments were derived largely from non-Indigenous mentors and indicated the pervasiveness of this type of stereotyping across non-Indigenous communities:

It's pretty stupid and ignorant of me but while I intellectually knew I hadn't really internalised the fact that not all Aboriginal Australians had darker skin, "looked a certain way". If I hadn't been told they were Aboriginal I would never have guessed. And a better understanding of how being Indigenous informs their identity (Q16 non-Indigenous mentor).

That being Indigenous isn't how you look but how you identify (Q23 non-Indigenous mentor).

These quotations explicitly refer to an unlearning of the misconception that all Indigenous Australians are 'dark-skinned'. New understandings of the diverse appearances of Indigenous Australians were discernible in this data. For example, six non-Indigenous mentors described what they had learned from AIME by quoting the adage, 'never judge a book by its cover'. The importance of these findings is reflected in the writings of numerous Indigenous researchers and scholars who have pointed to the stress emerging from a pervasive contemporary public resistance that Indigenous Australians have been forced to endure when attempting to embrace their sense of identity (Carlson 2013; Nakata 2012; New South Wales Aboriginal Education Consultative Group (NSW AECG) 2011).

The 'unlearning' of stereotypical assumptions was also evidenced in mentors' comments regarding contemporary Indigenous culture, which indicated how mentors' understandings had shifted from historically based understandings of 'Aboriginals'. For instance, one mentor described not having a conception of the urbanity of Indigenous Australians prior to involvement in AIME:

I am able to work with Indigenous Australians in metropolitan Melbourne without travelling to an Indigenous community (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

Fredericks (2013) has shown that urban Indigenous Australians are too often, and mistakenly, perceived as not being authentic, however, this author points out that both urban and metropolitan locations are closely tied to many Indigenous Australians' connection to country and culture. Indeed, it can be argued that most Australian urban environments contain strong symbols of Indigenous sovereignty through artworks, signage, murals and active cultural community organisations and practices. Promisingly within this study, many of the comments in this vein spoke to developing a new appreciation of the diversity of the contemporary (as opposed to historically constructed) Indigenous culture:

[From AIME I learned about the] [d]iversity of the Aboriginal experience (Q23 non-Indigenous mentor).

It made me want to learn more about the history and the contemporary life of Aboriginal Australians (Q22 Indigenous mentor).

The knowledge and understanding gained from their participation in AIME was both profound and powerful. Aside from discrediting socially embedded racial stereotypes, this learning is also significant in terms of effects on the mentors. The following section describes how mentors reflected upon these new knowledges and how they applied this understanding.

Going wider - moving to advocacy and promotion

The qualitative results of our survey offer firm support for identifying a relationship between the mentors reported 'cultural and social awareness', 'respect of Indigenous knowledge, cultures, and values', and their 'desire to implement constructive change in [their] community' (the top three learning outcomes reported by the mentees, see Table 4). However, this knowledge did not just impact the individual respondents, instead, the mentors report utilising this newfound understandings and respect for Indigenous knowledge, cultures and people to similarly educate others. The focus of this educational and advocacy work is characterised by an intention to reduce racism in their communities, become more involved in volunteer work and alter their workplaces and work practices for the benefit of the Australian Indigenous community.

Many mentors expressed a sense of needing to disseminate their learning from AIME, for the benefit of their family, friends and colleagues. For example, a number of non-Indigenous mentors revealed awareness of the racist stereotypes made about Indigenous Australians. These stereotypes retain currency in Australian society, a problem profoundly illustrated by the racist slurs made by non-Indigenous crowd members to Australian Rules Footballer, Adam Goodes (Lutz 2014). One mentor explained holding a commitment to 'educating friends and people I meet that to be Aboriginal doesn't mean that you are a person who is a criminal or doesn't do the right thing. It sometimes just means they have disadvantages and they are living life the best way they can figure out with the resources they have' (Q22). Similarly, another mentor described how participating in AIME provided skill in 'how to respond to casual racism heard in public, but now I'm more confident about politely telling someone that I've had great experiences with Aboriginal people and I appreciate them not speaking about them disrespectfully' (Q22). A number of mentors overtly described how AIME had instilled a lack of tolerance in relation to stereotypes and racism. These responses included statements such as:

I no longer turn a blind eye to racist or discriminatory comments. I have become a great advocate for this program and for Indigenous awareness in general (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

AIME has given me the voice to spread the word to other people about why the program is vitally important in changing the futures of Indigenous kids (Q22, non-Indigenous mentor).

Such perceived increases in skills for dealing with and reducing racism in the community and a 'giving of voice' to take an ethical stand on this matter are profoundly important outcomes from this participation. Indeed, the importance of this finding is highlighted in research that suggests that Indigenous Australian students who experience racism are significantly more likely to disengage from school (Bodkin-Andrews, Denson & Bansel 2013) and increase the risk of poorer performance in school exams (Bodkin-Andrews, Denson, Finger & Craven 2013). This is a somewhat invisible and unreported consequence, which also arguably has repercussions for the broader Australian community. Given the magnitude of this issue, these are clearly beneficial outcomes of participation in AIME that have potential impact for the Australian community given the numbers of university student mentors involved in AIME across Australia. This flow-on effect is identifiable via references to the mentors' increased volunteering and community involvement. In total 23 mentors reported increased participation or aspirations to participate in voluntary or community-based activity.

The knowledge derived from their involvement in AIME did not only impact upon the mentor's actions and reactions but also had broader repercussions as well. Some of the respondents made reference to the 'ripple' effect that this participation had engendered, impacting on professional and educational contexts.

My knowledge of Indigenous Australia and the difficulties that Indigenous people face in completing school ... has increased my appreciation for and the need for diversity within the workforce, which is extremely important in my role as a Senior HR Advisor (Q16 non-Indigenous mentor).

We have been working on an Indigenous employment/training program at work since my involvement with the AIME Program (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

It has been part of the motivation for me to seek employment in the Indigenous Education sector (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

Studying Primary Teaching, I have decided that after gaining 2-3 years teaching experience, I will teach in an Indigenous community (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

I want to become much more involved with the youth in my community. AIME demonstrated just how far kids can go when someone is there to support them and their achievements. After I graduate, I would also like to spend some time working with Indigenous youth in other parts of Australia (Q22 non-Indigenous mentor).

In exploring the mentors' perceptions of participating in the AIME Program, a range of unexpected and somewhat invisible outcomes have been noted. While traditional understandings of mentoring rest on the tenet that an expert with an interest in fostering success in others will 'share' their expertise to ensure the success of an individual otherwise identified as 'at risk' of failing in the focus task/capacity/role (Rogers 2009; Zeind et al. 2005), the quotations above suggest a very different dynamic. Rather than the traditional flow of mentoring whereby the mentor is cast more as the teacher and subsequent learning is attributed as an unexpected 'bonus', we contend that this programme ruptures this traditional pedagogic flow. This rupture is indicated by the importance and impact of the learning undertaken by the mentors at AIME; the mentors learning is far from trivial, it is re/defining their knowledge of Indigenous cultures and subsequently impacting how they engage with their communities and places of work. The next section will discuss both the implications of this shift and explore how a programme such as AIME can be actioned in other educational contexts.

CONCLUSIONS

The success of the AIME Program can clearly be measured both in terms of its impact on the mentees and also on the mentors who clearly articulate deep and profound effects. Significantly, the AIME approach is very much grounded in the mentors' capabilities, adopting a 'bottom-up' (collaborative and democratic) approach to engaging the mentees. This included encouraging mentors to adopt the role of learner by providing opportunity for the mentee to instruct the mentor and also, avoiding prescriptive outcomes or objectives. We have detailed the characteristics of this organic approach in another publication (O'Shea et al. 2013) but the literature in this field also underscores the importance of gender, ethnicity and common interests when matching mentors and mentees (Brown & Hanson 2003; Valeau 1999; Zeind et al. 2005). The AIME Program does not subscribe to this view and does not require gender or ethnic parity in its mentor relationships. Instead, by providing a 'culturally safe' (Harwood et al. 2013:62) space for learning, these mutually beneficial transactions are facilitated, resulting in positive outputs for all involved.

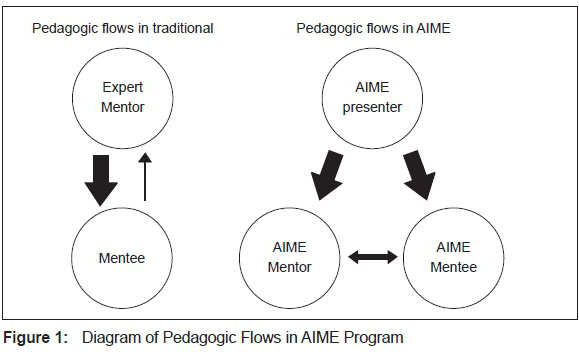

The positive flow-on effect of such knowledge creation is noteworthy. This not only included increases in personal knowledge and skills sets but also, more importantly, offered the opportunity for non-Indigenous people to develop a cultural tool-kit that promoted a 'zero tolerance' approach to racism. Arguably, such positive and demonstrable transformations can only occur when mentor/mentees do not share an ethnic background; instead both mentor and mentee are positioned as learner and leader, their relationship is one of reciprocity with dual pedagogic flows. The following figure highlights how we perceive the pedagogic flows that exist in the AIME programme and how these differ from more traditional mentoring programmes. The exchange of knowledge moves between mentees and mentors, neither is positioned as more knowledgeable or more powerful in this relationship:

This approach differs significantly from other types of 'engagement mentoring' models where mentors seek to transform 'young people's attitudes, values, behaviours and beliefs - in short, their dispositions' (Colley 2003:79). Instead, the AIME mentoring programme seeks to engender a more collaborative model, involving the mentors, the mentees, school representatives and key community members in this process. This is a model that seeks to work 'with' rather than 'on' people, a collective network that does not deny the agency or the habitus of the participants. Moving away from deficit constructions of mentee as somewhat 'lacking', the AIME programme draws upon the rich cultural heritages of participants, providing space for these to be both celebrated and foregrounded.

In closing we wish to emphasise the valuable experiences that mentoring provided for Indigenous university mentors. Such benefits can include providing links that sustain these students at university (O'Shea et al. 2013). These are not the only benefits, as AIME encourages a strong sense of collegial responsibility and leadership.

AIME made me realise how closely the younger mob are watching us. Even if we do not intend to lead, we are influencing their journeys (Q16 Indigenous mentor).

This mentor's awareness of being closely watched reveals not only the extent of their sense of responsibility, but also a strong feeling of how they, as mentors are ''influencing [the young people's] journeys'. The ripples and flows of learning reported here impacted all parties, the Indigenous mentees as well the mentors, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous - such a level of reciprocity not before reported in this field.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The question remains how might other mentoring programmes replicate this approach, and so we conclude this article with a series of recommendations, drawing upon both this empirical work and pedagogical theory. The following suggestions are designed for other programmes that may be drawing upon mentoring as a means to engage with young people and extend their educational futures.

• Develop respect and regard for all participants - this should be a mutual relationship, not one based upon power

• Build 'teaching moments' into the programme for both mentors and mentees

• Recognise that mentors who are from different ethnic, or socioeconomic backgrounds than their mentees may need support when trying to understand cultural differences in their cross-cultural mentoring relationship. AIME addresses this challenge through cultural awareness training for their mentors

• Provide regular and substantive opportunities for mentors and mentees to meet. These meetings need to be authentically framed, including opportunities for all parties to demonstrate their respective cultural and knowledge capitals.

NOTES

1 Q29 refers to 'Question 29' of the survey.

2 There is a parallel research project within the AIME Partnership Project that investigates whether mentoring with AIME enhances the university experience of the mentors. The list of attributes in Question 24 of the survey was designed to align with the university graduate attributes of universities participating in the AIME Program. To achieve this, the 'graduate qualities'/'graduate attributes' policies of each of the participating universities were read and key words in each of these documents were tracked (both for frequency and variations across universities). This data was then analysed to come up with the list in Question 24 (see Tables 3 and 4).

3 While quoting this statement from a mentor, we note that the term 'ATSI', while used in some governmental and wider public contexts, is not a preferred term for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia.

4 As explained by the Runnymede Trust (and cited on public anti-racism site, Racism No Way), terms such as 'race' 'are remnants of a belief formed in previous centuries, now discredited, that human beings can be hierarchically categorised into distinct "races" or "racial groups" on the basis of physical appearance, and that each so-called race or group has distinctive cultural, personal and intellectual capabilities' (Runnymede Trust 1993:57, cited by Racism No Way)

REFERENCES

ABS. 2013. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2011 (cat. no. 3238.0.55.001). Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats.

ACER. 2010. Doing more for learning: Enhancing engagement and outcomes. Australasian survey of student engagement. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research. [ Links ]

AIME. 2014a. 2013 Annual Report. Retrieved from http://aimementoring.com/about/reports/.

AIME. 2014b. About AIME. Retrieved from http://aimementoring.com/about/aime/.

Ainsworth, G. & McRae, D. 2009. What works. The Works Program: Improving outcomes for Indigenous students. Successful Practice. Australia: Commonwealth of Australia. [ Links ]

Altman, J. C., Biddle, N. & Hunter, B. 2009. How realistic are the prospects for 'closing the gaps' in socioeconomic outcomes for Indigenous Australians? Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, ANU. [ Links ]

Anderson, C., Bunda, T. & Walter, M. 2008. Indigenous higher education: The role of universities in releasing the potential. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 37:1-7. [ Links ]

Beltman, S. & Schaeben, M. 2012. Institution-wide peer mentoring: Benefits for mentors. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education 3(2):33-44. [ Links ]

Beresford, Q. 2012. Separate and equal: An outline of Aboriginal education. In Q. Beresford, G. Partington & G. Gower (Eds.), Reform and resistance in Aboriginal education, 85-119. Western Australia: UWA Publishing. [ Links ]

Bodkin-Andrews, G. & Carlson, B. 2013. Higher education and Aboriginal identity: Reviewing the burdens from personal to epistemological racism. In R. Craven & J. Mooney (Eds.), Diversity in Higher Education: Seeding success in Indigenous Australian higher education, Volume 14, 29-54. Bradford, UK: Emerald Group Publishing. [ Links ]

Bodkin-Andrews., Denson, N. & Bansel, P. 2013. The varying effects of academic self-concept, multiculturation and teacher discrimination as predictor of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian student academic self-sabotaging and disengagement. Australian Psychologist 48:226-237. [ Links ]

Bodkin-Andrews, G.H., Denson, N., Finger, L. & Craven, R. 2013. Identifying the Fairy Dust Effect for Indigenous Australian students: Is positive psychology truly a [Peter]Pan Theory? In R.G. Craven, G.H. Bodkin-Andrews & J. Mooney (Eds.), International advances in education: Global initiatives for equity and social justice, 183-210. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. [ Links ]

Bodkin-Andrews, G., Harwood, McMahon, S. & Priestly, A. 2013. AIM(E) for completing school and university: Analysing the strength of the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience. In R. Craven & J. Mooney (Eds.), Diversity in Higher Education: Seeding success in Indigenous Australian higher education, Volume 14, 113-134. Bradford, UK: Emerald Group Publishing. [ Links ]

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H. & Scales, B. 2008. Review of Australian Higher Education: Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.deewr.gov.au/HigherEducation/Review.aspx.

Brown, B.K. & Hanson S.H. 2003). Development of a student mentoring program. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 67(1/4):947-953. [ Links ]

Calton, S.E. 2010. The effects of a holistic school-based mentoring program on middle school at-risk students. Doctoral Dissertation. Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Thesis database. [ Links ]

Cameron, K. & Quinn, R. 2011. Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework (Third ed.). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Carlson, B. 2013. The 'new frontier': Emergent Indigenous identities and social media. In M. Harris, M. Nakata & B. Carlson (Eds.), The Politics of identity: Emerging Indigeneity. Sydney: UTSePress. [ Links ]

Colley, H. 2003. Engagement mentoring for socially excluded youth: Problematising an 'holistic' approach to creating employability through the transformation of habitus. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling 31(1):77-99. [ Links ]

Commonwealth of Australia Department of Industry. 2014. Statistics publications. Student 2012 full year: Selected higher education statistics publication. Retrieved from http://www.innovation.gov.au/HigherEducation/HigherEducationStatistics.

Devlin, M. 2009. Indigenous higher education student equity: Focusing on what works. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 38:1-8. [ Links ]

Dudgeon, P. & Kelly, K. 2014. Contextual factors for research on psychological therapies for Aboriginal Australians. Australian Psychologist 49(1):8-13. [ Links ]

Foley, D. 2003. Indigenous epistemology and Indigenous standpoint theory. Social Alternatives 22(1):44-52. [ Links ]

Fredericks, B. 2013. 'We don't leave our identities at the city limits': Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in urban localities. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2013(1):4-16. [ Links ]

Harrell, P.E. & Forney, W.S. 2003. Ready or not, here we come: Retaining Hispanic and first generation students in postsecondary education. Community College Journal of Research and Practice 27:147-156. [ Links ]

Harwood, V., Bodkin-Andrews, G., Clapham, K., O'Shea, S., Wright, J., Kervin, L. & McMahon, S. 2013. Evaluation of the AIME Outreach Program. University of Wollongong, Australia.

Holt, B. 2008. 'You are going to go somewhere!' The power of conferred identity status on disadvantaged students and their mobility to university. Paper presented at the Australian Association for Research in Education: Changing climates education for sustainable futures. Retrieved from http://www.aare.edu.au/conf2008/index.htm

Irabinna-Rigney, L. 2011. Indigenous education and tomorrow's classroom: Three questions, three answers. In N. Purdie, G. Milgate & H.R. Bell (Eds.), Two way teaching and learning: Toward culturally reflective and relevant education, 35-48. Melbourne: Australian Centre for Educational Research. [ Links ]

James, R. 2008. Participation and equity: A review of the participation in higher education of people from low socioeconomic backgrounds and Indigenous people. Melbourne: Centre for the Study of Higher Education. [ Links ]

KPMG. 2013. Economic evaluation of the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience program: Final report. Retrieved from www.aimementoring.com.

Lutz, T. 2014. Essendon ban supporter for racial abuse of Adam Goodes. The Guardian 20 May. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/sport/2014.

Mackinlay, E. & Barney, K. 2008. 'Move over and make room for Meeka': The representation of race, otherness and indegeneity on the Australian children's television programme Play School. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 29(2):273-288. [ Links ]

Martin, K.L. 2008. Please knock before you enter: Aboriginal regulation of outsiders and the implications for researchers. Brisbane: Post Pressed. [ Links ]

Moreton-Robinson, A. 2013. Towards an Australian Indigenous women's standpoint theory: A methodological tool. Australian Feminist Studies 28(78):331-347. [ Links ]

Nakata, M.N. 2012. Better: A Torres Strait Islander's story of the struggle for a better education. In K. Price (Ed.), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education: An introduction for the teaching profession, 1-20). Victoria: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

NSW AECG Inc. 2011. Aboriginality and identity: Perspectives, practices and policy. New South Wales: AECG. [ Links ]

O'Shea, S., Harwood, V. & Kervin, L. 2011. Imagining university: Identifying the place of university in the lives and aspirations of Indigenous school students. University of Wollongong Research Grant (URC).

O'Shea, S., Harwood, V., Kervin, L. & Humphry, N. 2013. Connection, challenge and change: The narratives of university students mentoring young Indigenous Australians, Mentoring and Tutoring: Partnerships in Learning 21(4):392-411. [ Links ]

Owens, D.M. 2006. Virtual mentoring: Online mentoring offers employees potentially better matches from a wider pool of candidates. HR Magazine 51(3):105-107. [ Links ]

Price, K. 2013. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander studies in the classroom. In K. Price (Ed.), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education: An Introduction for the Teaching Profession, 151-162. Victoria: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Rogers, R. A. 2009. 'No one helped out. It was like, "Get on with it. You're an adult now. It's up to you". You don't ... it's not like you reach 17 and suddenly you don't need any help anymore': A study into post-16 pastoral support for 'Aimhigher Students'. Pastoral Care in Education 27(2):109-118. [ Links ]

Racism No Way. 2014. Understanding racism. Retrieved from http://www.racismnoway.com.au/about-racism/understanding/glossary.html.

Runnymede Trust. 2014. Runnymede: Intelligence for a multi-ethnic Britain. Retrieved from http://www.runnymedetrust.org.

Sarra, C. (Ed.). 2011. Strong and smart: Towards a pedagogy for emancipation: Education for first peoples. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

SCRGSP. 2011. Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: Key indicators 2011: Overview. Melbourne: Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, Productivity Commission. [ Links ]

Tuhiwai-Smith, L. 2012. Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. London and New York: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Stolberg, R. 2011. Student Mentoring. Access 25(4):2. [ Links ]

Trudgett, M. 2013. Stop, collaborate and listen: A guide to seeding success for Indigenous higher degree research students. Diversity in Higher Education 14:137-155. [ Links ]

Valeau, E.J. 1999. Editor's choice mentoring: The Association of California Community. Community College Review 27(33):33-46. [ Links ]

Walker, Y. 1993. Aboriginal family issues. Family Matters 35:51-53. [ Links ]

Walter, M. & Andersen, C. 2013. Indigenous statistics: A quantitative research methodology. California: Left Coast Press. [ Links ]

Yeung, A.S., Craven, R.G., Wilson, I., Ali, J. & Li, B. 2013. Indigenous students in medical education: Seeding success in motivating doctors to serve underserved Indigenous communities. Diversity in Higher Education 14:277-300. [ Links ]

Yunkaporta, T. & Kirby, M. 2011. Yarning up Indigenous pedagogies: A dialogue about eight Aboriginal ways of learning. In N. Purdie, G. Milgate & H.R. Bell (Eds.), Two way teaching and learning: Toward culturally reflective and relevant education 205-213. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research. [ Links ]

Zeind, C. S., Zdanowicz, M., MacDonald, K., Parkhurst, C., King, C. & Wizwer, P. 2005. Mentoring for women and underrepresented minority faculty and students: Experience at two institutions of higher education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 69(5):1-5. [ Links ]