Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Water SA

versión On-line ISSN 1816-7950

versión impresa ISSN 0378-4738

Water SA vol.43 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/wsa.v43i1.05

'Irrigation by night' in the Eastern Cape, South Africa

Bram van der HorstI; Paul HebinckII, III, *

IWageningen University, Department of Water Resource Management Group, Droevendaalsesteeg 3A, 6708 PB Wageningen, The Netherlands

IIUniversity of Fort Hare, Ring Road, Alice, 5700, South Africa

IIIWageningen University, Department of Sociology of Development and Change, Hollandseweg 1,6706 KN, Wageningen, The Netherlands

ABSTRACT

This paper addresses water-related issues in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Irrigation development and providing water for human consumption have been key factors in the country's rural development planning, notably during the postapartheid era when the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) and Water Services Act and Free Basic Water of 1997 became effective. By exploring the use of water in rural villages in the central Eastern Cape, the paper addresses the conceptual and practical limitations of the provisioning of water for human consumption and irrigation, in particular, and how this is being handled by various implementing agencies. The paper draws attention to the importance of 'irrigation by night' which refers to unplanned and 'unlawful' water-use practices. People in villages 'unlawfully' re-appropriate piped water for irrigation purposes to produce food and generate some income. The paper proposes a shift away from the rigid conceptualisations that currently form the backbone of planning to instead adopt a multiple-use system (MUS) approach which is more in tune with local practices currently observed in rural villages of South Africa.

INTRODUCTION

This paper explores the dynamics of the use of water at village level in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. It pays specific attention to 'irrigation by night' which refers to widespread small-scale, informal irrigation practices that cannot be easily observed and yet which are subjected to rules and modalities that control the use of water. Consequently, water meant exclusively for human consumption is also widely used for watering crops in home gardens and occasionally for cattle. Denison et al. (2015 p. ix) conclude that the use of water for productive use dominates current household water-consumption patterns. There are laws and governance structures in place in South Africa to prevent such use of water. Despite these, 'irrigation by night' is a common practice. The aim of this paper is to understand why this is so. Exploring and explaining such practices requires situating 'irrigation by night' in a broader historical and contemporary context of development interventions in the domain of land and water. The central question addressed in this paper is what lessons can be learned from past and present interventions in the field of water and land in South Africa, and the Eastern Cape in particular.

The reference to the notion 'irrigation by night' should not be confused with night irrigation to achieve improved irrigation efficiency to conserve water (less evaporation at night), and to prevent water-supply shortages during daytime irrigation peaks; typically tail-end users resort to night irrigation when top-end users are active during the day. We use 'irrigation by night' specifically to depict the practice of people tapping water meant for human consumption at times when the regulatory institutions are not functional or absent. We adapted the notion 'irrigation by night' from the work of Robert Chambers (1986, 2013). Chambers refers to the informal, invisible operations in irrigation systems in the night: 'It is common place that the night is the time for illicit appropriation of water' (Chambers, 1986 p. 54). The metaphor 'night' translates into situations where institutions, similar to those explored in this paper, have become dysfunctional.

The paper begins by contextualising 'irrigation by night' in the past and present policy frameworks of South Africa. This serves to problematise and conceptualise the central question of the paper. The following section is a condensed description of the importance of water for home garden production for food security in the Eastern Cape. The emerging dynamics cannot be understood without an analysis of a range of rural policy interventions before, during and after apartheid, either directly or indirectly, targeting land and water use. Land settlement planning of the late 1800s, betterment schemes, homeland policies, programmes to supply potable water and, more recently, water harvesting programmes all have to be taken into account in order to understand the broader policy dimensions that pertain to water and land. All these interventions have left their trace in the villages of the Eastern Cape. This forms the background to the next section, which focuses on the use of water for productive purposes in rural villages in the central Eastern Cape.

Orientation and central argument

This paper addresses 'irrigation by night' from different but related angles. Considering and exploring the continuities of past legal and development planning policy frameworks into the present allows for a detailed examination of the use of water, the issues that emerge from such usage, and what lessons can be learned. One of the key lessons this paper communicates is that most, but not all, interventions do not endure; this concerns both past and present policy interventions. The rules and regulations accompanying the interventions often create confusion and misunderstanding, and the institutions to enforce these rules and regulations are or have become dysfunctional over time.

The legal angle brings to the fore the fact that post-apartheid new water laws have been enacted and related strategies designed and implemented to address issues of distribution and access to land and water. The use and supply of water is subject to changes at the level of water laws that are part and parcel of post-apartheid land and agrarian reform policies actively seeking to address the inequalities of apartheid. Following the provisions for treated (e.g. chlorinated) water in the Water Services Act (RSA, 1997) and Free Basic Water policy of 1997, 'irrigation by night' is considered unlawful. The 1997 Water Services Act made domestic water a public good, which means that individuals have the right to free water for domestic purposes (Stein, 2005). The Free Basic Water (FBW) target volume is 6 000 L per month per homestead (WAF, 2007; DWA, 2013). However, since the monitoring of the volume of water used in homestead gardens is difficult given the lack of technical and institutional capacity to do so, the Water Services Authorities (WSAs), to whom the supply of water is decentralised, adopted the regulation that no home garden watering from the piped domestic supply is allowed at all - even if the homestead uses less than the FBW amount that the Water Act of 1997 and RDP (1994) prescribes. After all, the WSAs supply treated water at substantial costs. Budgets and the capacity of the system are stretched when this water is also used for non-household purposes. To prevent this 'unlawful' use of water, water-providing infrastructure is accompanied by a set of rules and regulations and committees are installed to prevent water usage that is not in line with the rules and regulations. Despite these regulatory devices 'irrigation by night' is ubiquitous.

'Irrigation by night' is also significant when looked at from the perspective of development planning, its modalities, and experiences with past and present state interventions in the domain of land and water. Common to planning in South Africa, and Africa more broadly, is that it ignores local practices and gives priority to expert knowledge and advice, frequently rendering unrealistic plans that are rooted in limited and rigid conceptualisations of water and its everyday uses. A major emerging policy issue is a great discrepancy between policy objectives and implementation, and between planning and the emerging everyday realities in villages. Poor (irrigation) planning was already acknowledged by the Tomlinson Commission (1955 p. 121): 'the chief reason for the lack of interest in irrigation in the Transkei and Ciskei, must be sought in the fact that the schemes were not properly planned.' James Scott (1998) explains this phenomenon in his ground-breaking study, Seeing Like a State, with reference to the life-worlds of the experts and their technocratic, rigid ways of linking theory to practice. In this context, experts consist of the consultants, advisors, NGOs and academics that operate in the field of 'development. Their knowledge and expertise is very significant and penetrates the villages in the form of government-funded projects and programmes (Hebinck et al., 2011; Minkley, 2012). The need to achieve food security materialises into projects such as water-harvesting projects (Monde et al., 2012; Minkley, 2012) and the Siyazondla Homestead Food Production Programme (Siyazondla) (De Klerk, 2013; Fay, 2013) and the Massive Food Production Programme (Mayibi, 2013). Such programmes and projects, however, generally do not endure beyond the 4- to 5-year project cycle of funding.

Typically, the technocratic approaches that underlie these projects disregard the social dimensions of rural life (Fairhead and Leach, 2005). Development is seen as taking place within restricted parameters of what is considered proper irrigation and use of water. The use of land and water is measured as homogeneous whereas diversity is the norm. The water practices that do not fit the narrow definitions are overlooked and often deemed irrelevant. Planning for water and irrigation henceforth takes place with limited to no inputs from the perceived beneficiaries, whose experiences are not considered relevant (Long, 2001). Experts, moreover, tend to ignore that a majority of rural people derive income in cash and kind from a multitude of sources; agriculture only contributes marginally (Hebinck and Lent, 2007; Hebinck and Van Averbeke, 2013). This development pattern is inconsistent with the NPC stance that 'agriculture is the primary economic activity in rural areas' (NPC, 2011 p. 219), a position that ignores what happens in villages, but which supports the government and NGO managers' narrative for the increased need for knowledge transfer and training. The result is an exclusive focus on management, efficiency and the use of technology to modernise the agricultural sector, increase production and initiate efficient water use practices. Technology and modernisation are seen as central pillars to achieving the country's goals to uplift the poorest of the poor, ensure food security and provide employment. This poignantly makes clear that 'irrigation by night' becomes even more significant at a time when many of the smallholder irrigations schemes in the former homelands 'Ciskei' and 'Transkei' have become dysfunctional. This is quite in contrast to those in the former White commercial farming areas (Van Averbeke et al., 2011). Small-scale irrigation in the former homelands is, however, very significant for relieving the state of food poverty and insecurity in the Eastern Cape (Van Averbeke and Denison, 2013; Cousins, 2013; Denison et al., 2015).

We argue in this paper that the views and experiences of the users of land and water, and their water and land use practices, are extremely relevant and worthwhile to take into account in policy initiatives and interventions to expand, improve and strengthen irrigation potential and food production. Hence we propose that 'irrigation by night' is a significant practice that contributes to food security. This fits neatly with the 'multiple use system' (MUS) approach adopted by The International Water Management Institute (IWMI) (Pant et al., 2006; Penning-De Vries and Ruaysoongnern, 2010). MUS significantly builds on the idea that water is a basic necessity. It is important to emphasise, though, that we do not argue against externally designed interventions as such. Instead we draw attention to the fact that local actors unpack interventions in their own way, re-assembling and integrating aspects of these interventions into their own practices (Hebinck, 2013).

METHODOLOGY

The data for the analysis of 'irrigation by night' practices is drawn from a longitudinal research project that began in 1995 in the villages of Guquka and Koloni situated in the central Eastern Cape in South Africa. The paper makes use of data from village-wide surveys, held in 1995 and repeated in 2010, to capture the dynamics of rural livelihoods (Hebinck and Lent, 2007; Hebinck and Van Averbeke, 2013). The surveys respectively covered 93% and 67% of all inhabited homesteads in Guquka and 82% and 76% in Koloni. Those homesteads that were not regularly inhabited (e.g. only once a month or once a year) or deserted were excluded from data collection. Data were also drawn from recurrent field visits, observations and numerous interviews with villagers. Case studies of fields and homesteads combined with field observations for more than 20 years allowed for the development of an in-depth understanding of land and water use. The combined data sources provide detailed insight into the use and governance of water as well as the relative importance of 'irrigation by night'; this helped us to unravel the social dynamics of land and water issues and social relationships between villagers and project implementers. The longitudinal set-up of the study allows for capturing variations of peoples' land and water husbandry practices at different times. In addition, the analysis was calibrated with insights from literature sources about land and water issues in South Africa and the Eastern Cape, as well as from policy documents from DWAF (national Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, later renamed Department of Water Affairs (DWA) and currently the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS)) and many technical reports published by the Water Research Commission.

Water and the importance of home gardens

In contrast to the fallow state of the arable fields - once allotted to people to cultivate crops - homestead gardens are actively and relatively intensely cultivated with a range of crops. The shift from arable farming to homestead gardens is a common feature of agriculture in the former homelands of Ciskei and Transkei in the Eastern Cape (Murata and Denison, 2015). This trend was set in motion in the 1930s in the Ciskei and some 30 years later in the Transkei and is well documented by Andrew and Fox (2004), Hebinck and Monde (2007), De Wet (2011), Hebinck and Van Averbeke (2013) and Shackleton et al. (2013). Data gathered by Hebinck and Monde (2007 p. 183) for Guquka depicts that in the 2003/04 season only 25% of a total of 41 arable allotments were cultivated. In 2010 this was reduced to 7% (Hebinck and Van Averbeke, 2013). In the summer of 2014, when one would expect fields to be cultivated, it was found that none of the arable fields were being cultivated (personal observation, January, 2014). In 2015 we observed one cultivated field. The gradual shift from cropping arable fields to home gardens can be explained by multiple factors that in turn interact with one another. The shift in labour migration from 4- to 5-month contracts to fulltime contracts, the gradual but steadily growing importance of social grants and remittances, and land tenure relations, combined with an aging population, are all factors contributing to agricultural activities having become less and less important (Hebinck and Monde, 2007; Hebinck and Van Averbeke, 2013; Manyevere et al., 2014). In addition, most people's livelihoods hinge on multiple activities rather than on agriculture alone (see Table 1).

Food purchase has become the predominant source of daily food procurement (D'Haese and Van Huylenbroeck, 2005; Hebinck and Monde, 2007). Income generated through crop and livestock production has decreased in Guquka from 6.7% to 6.1 % and in Koloni from 12.1% to 8.2%. By contrast, the relative importance of grants, pensions and, to a lesser extent, remittances remains relatively stable. Similar contributions of agriculture to rural livelihoods are reported in Van Averbeke and Mohammed (2007), Aliber and Hall (2010), De Wet (2011) and Denison et al. (2015).

Table 2 shows the extent to which people purchase food outside the village in supermarkets in Alice, King William's Town or Middledrift. Other than in a few exceptional cases, respectively 13 and 8, people rely on a mixture of purchasing food externally and producing food (vegetables, maize, meat, poultry) locally. Nevertheless, the use of land, labour and water for food production is not insignificant and forms an important part of the food security picture in villages like Guquka in the Eastern Cape and beyond. Food farming is a crucial element in food supply and supplements food purchases in significant but varying ways. Home gardens are primarily aimed at feeding the family. They are not chiefly commercial ventures although there are exceptions, to which we will return later.

Water is used for both human and productive purposes. Water is generally used for drinking, cooking, washing and bathing but also for crops and brewing beer for ceremonial purposes. The most common source of water is the communal water tap. These taps are the product of post-apartheid RDP programmes (RDP, 1994). Guquka has had communal water tap stands since 1994. These were constructed according to the RDP requirements that tap stands should be situated less than 200 m walk away from the homestead. Rainwater tanks sometimes provide an additional supply. A few small dams and the Tyume River provide other sources of untreated water but they are too far from the homesteads - in most cases a 45 min walk - to be a preferred option. In some cases, usually in winter, villagers resort to purchasing treated water from vendors (Monde and Aliber, 2007 p. 30).

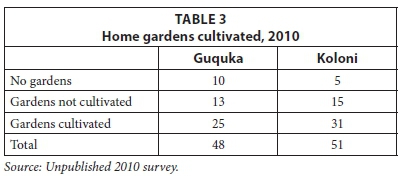

The home gardens are expected to be fed by rainwater only. There are not many active attempts to divert water from the roads and rainwater tanks ('Jojo's') to water the gardens. The construction and use of ponds at the residential site to store water for watering crops, identified by Denison and Wotshela (2012) as one of the indigenous water-harvesting practices, is in Guquka limited to one homestead only (Mr Pazi, see below). The use of water from these dams is, however, limited to providing drinking water for cattle that roam the villages. Occasionally one sees a youngster filling a bucket of water for watering homegarden crops. Table 3 signals the degree to which home gardens are cultivated or not. With about half of the gardens in use, the demand for water is relatively high and so is the use of water taps for irrigation.

The consumption of water is generally low and well below the RDP target of 25 L per capita per day (Monde and Aliber, 2007 p. 28) which is less than recommended by FAO (ibid p. 28). Denison et al. (2015 p. ix) recently calculated 'a median water use of 18 L per capita per day, and 2 786 L per household per month (and this includes water for livestock and crop watering)' for selected areas in the Eastern Cape. This, they show, 'is less than half of the FBW-provision requirement of 6 000 L per month per household. Of the individuals surveyed (n = 180 persons), 71% are using less than Government targets of 25 L per day, and 38% are using less than 12 L per day (including water for livestock and crop watering), showing a situation of serious water deprivation. When supply is limited and pressure is low, competition for water for human consumption and gardens increases. If maintenance and expansion of drinking water facilities is ignored and investments reduced, the competition may increase and may have negative food security-related consequences.

Land- and water-related interventions

Various governments, colonial, apartheid and post-apartheid alike, intervened in many ways in the rural areas of the Eastern Cape. Various interventions and programmes have been planned and implemented over the past 150 years. A major theme running through these interventions, notably in the sphere of water and other services, is that they do not always endure, and impact fades away after some time. The only exception seems to be the piped water system, and the social grants programmes. The latter will not be discussed in this paper (see Lund, 2007; Gutara and Tanga, 2014).

Pre-1994 - land allocations and betterment

Prior to betterment planning in the 1930 to 1960s, the colonial government made a distinction between land allocated for crops, between 3 and 4 morgen (2.5 to 3.4 ha) in size, and land intended for residential purposes (building lots which included some space for home gardens). The remaining land was designated as 'commonage. The rights to land were fixed by the so-called quit-rent arrangements. The land was subsequently allocated to heads of homesteads by the chief.

The Tomlinson Commission Report published in 1955 reflected and formally acknowledged the view that emerged during the 1940s and 1950s that improving the natural environment in areas designated as 'native reserves' and the organisation of the use of natural resources was an urgent priority (De Wet, 1989). Betterment planning came to Guquka in the early 1960s. During betterment, two smaller dams and a slightly bigger dam were constructed to retain water for cattle and crops and, as a secondary objective, for human consumption. Betterment is largely known for its social and physical reorganisation of villages. However, there is less reference to betterment as bringing and expanding education facilities (schools) and water infrastructure.

Post-1994 - potable water supply system water harvesting

In the framework of post-apartheid policies and RDP policies, new and additional services were provided to rural villages like Guquka. A windmill was built to pump groundwater to a stand-pipe positioned in the centre of the village, providing access to clean and safe water. The windmill is defunct now due to lack of maintenance. Temporary employment was provided to some of the unemployed residents through the Working for Water Programme of the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (Van Averbeke and Bennett, 2007). At a later stage, communal water taps were constructed. In some homesteads, yard taps were installed. The water was exclusively intended for human consumption. The water is pumped from the Binfield Park Dam some 10-15 km away and, after treatment, provided to people free of charge. Municipalities are mandated to provide 25 L of potable water per person per day, a maximum distance of 200 m from a dwelling, and with a flow rate of not less than 10 L a minute, or 6 000 L of free potable water supplied by a formal connection per month (in the case of yard or house connections) (RDP, 1994; DWAF, 2007; DWA, 2013).

In Guquka a committee was installed, in conjunction with the piped water system, to regulate the water usage. However, this committee is now dysfunctional and water usage is not regulated by the committee. This dysfunctionality has been present ever since the committees were installed, in the early years after 1994 when villages like Guquka were in turmoil. For instance, records were destroyed and chiefs were replaced by Residential Committees who became responsible for many affairs in the village (Van Averbeke and Bennett, 2007). This confusion about roles and responsibilities regarding water still persists. Most people in Guquka, when asked, were not aware of FBW and related initiatives. During a visit in November 2015 one of us was approached by villagers complaining that the water pressure was low. They had not been able to tap any water for weeks. They clearly indicated that they had no idea to whom they should turn to remedy the situation. For the Sirhosheni village that is part of the same district municipality as Guquka this is, however, very clear. Sirhosheni was in 2013 and 2014 incorporated in a regional water supply scheme to provide water services at an RDP level of supply of 25 L per person per day. The Amathole District Municipality provides the water services to Sirhosheni (Denison et al., 2015 p. 138). They stipulate that 'agricultural use of (treated) water is not permitted by the Water Services Provider (Amathole District Municipality).

New laws and regulations are written at the national level. It is, however, within the lower/local levels of government that, in varying ways, new laws and regulations are communicated and implemented. Such changes in policy take time to trickle down to the lower level of government. The implementation of the MUS approach exemplifies this, as according to the Department of Water Affairs (2013), the integration of a MUS approach is yet to be adopted and implemented. The opportunities that the new policies offer, but also the restrictions and regulations of water use in terms of purpose and quantity are clearly written up in the new policy documents. The FBW-committed target volume of 6 000 L per homestead per month does not always specify clearly that this volume can only be used for domestic purposes. Denison et al (2015) reported similar problems and processes in Mbekweni. Villagers, including the committee members, use water for any purpose. The amount of water collected and used in this way is difficult to measure due to the absence of water meters and a monitoring system. This explains why WSAs adopted a rational plan: a blanket ban on watering gardens using hose connections, despite a reality where people typically use less than the FBW target volume (see also Denison, et al. 2015). The persistent problem unfolding here is that policies are paved with good intentions but are not well communicated to villages, hampering in turn the much-debated service delivery problem in the country (Aliber and Hall, 2010, 2012).

A more recent small-scale water-related project is the rainwater harvesting (RWH) project in Guquka implemented by the Agricultural Research Council and the University of Fort Hare. The RWH project's objective was 'creating a sustainable livelihood through farming' (Monde and Aliber, 2007 p. 32 ff; and see also Minkley, 2012). The underlying assumption of this and other RWH projects is that people are inclined toward intensifying their agricultural activities and to providing more labour, money and other scarce resources to practice water harvesting. Whether this is realistic given the degree and extent of de-agrarianisation (see Table 1 and 3) and the persistent culture of purchasing food (see Table 2), remains a question. Findings from our longitudinal research engagement for over 20 years in Guquka and Koloni (Hebinck and Lent, 2007; Hebinck and Van Averbeke, 2013) warrant such caution. Denison et al. (2015) are more positive in their assessment of the interest in agriculture in the Eastern Cape.

Water harvesting in Guquka entailed the promotion of in-field water harvesting combined with roof water collection. In this way, it aimed to make water available by harvesting rainwater for a wide range of uses, including drinking, agriculture and cleaning. Both individual and collective community gardens were constructed. 15 ha of fenced land, and water stored in a stock dam, were made available for the community garden. The garden seems to have been placed in the hands of a couple of members of the rainwater harvesting project. It was planted once, according to informants from Guquka (Van der Horst, 2013). With no clarity about who was in charge of the garden or who actually owned it, it was soon allowed to go fallow.

Project members, 25 in total, were taught to use the in-field rainwater harvesting (RWH) technique, lay out home gardens, space crops and raise seedlings. It is important to point out that there are many RWH techniques that can be applied to gardens. In this case the promoted RWH techniques were restricted and the project promoted only one technique. They were shown how to construct ridges to catch water from open areas in the garden itself. This was facilitated by lower plant densities (roughly skipping 1 or 2 rows of conventional spacing). The crop production approach was characterised by extensive plant densities, mono-cropping (no mixed plantings, etc.), considerable soil exposure and RWH in the garden beds. The project also included seed distribution, workshops, competitions and the provision of a 5 000 L 'JoJo' tank for roof runoff collection. This was deemed sufficient for a garden of only 30 m2 in the 4-month low-rainfall period at Guquka. In effect this meant that gardening activities ceased in the dry season.

As of January 2014, Ms Magatyeni was the only member of the original rainwater harvesting project still practising rainwater harvesting techniques in her home garden. Everyone else had discontinued water harvesting practices and most of their home gardens clearly lacked maintenance. This could be explained partly by the fact that the credit supply that supported the purchase and use of fertilizers and new seeds was discontinued at the end of the 4-year project cycle. Interest to participate faded after the project terminated. The initial assumption that people had an interest in finding ways to harvest water in order to intensify home gardening now appears unrealistic in a context in which piped and treated water is supplied free of charge; it is an affordable and relatively easy option for home garden intensification. From a systems perspective, it is clear that one of the parts in the system, the credit supply and support services, were finite, which led to the cessation of system functions. Next to credit or fertilizers, other key inputs needed to make the system work -knowledge, experience, markets and more broadly an interest in farming - are clearly absent. The project failed to create an enduring effect.

Contemporary water and land use realities

We provide a few profiles of some active gardeners to show how people use water targeted for human consumption for gardening. The aim is to demonstrate that home gardening is important for villagers rather than to provide technical information about garden size and land use intensity. This account also gives a picture of how the remnants of past betterment interventions have been reassembled and mixed over time with the more recent interventions in the domain of water for crops and people. 'Irrigation by night' emerges as a significant practice and source of water for the gardens. Water harvesting, as an introduced practice, we argue hardly endured in Guquka:

The inappropriate choice of RWH technology would have contributed to the failure of the system - among other socio-institutional-technology factors. The choice of the 'infield' technique, which is by design an extensive technique (33% of surface area is used as collection surface) and which is best suited to field-scale cropping, was probably not the best choice for intensive gardening that is typically practiced in confined spaces. Combined intensive RWH practices such as trench-beds, run-on collection from roads/ditches, mulching coupled with supplementary irrigation from JoJo-tanks and ponds may have been a more appropriate RWH approach for this context" (Denison, 2015).

Nombasa Dibela is a middle-aged woman who lives in Guquka with her adolescent brother-in-law. The rest of her family, including her husband, live in Cape Town. Her husband, a taxi driver, and one of her sons, a postman, send home remittances on a regular basis. She keeps pigs and chickens around the house and has reserved a piece of land for the cultivation of crops. She also has an additional residential unit, which is not in use for residential purposes but instead is used for the cultivation of crops. These crops include maize, cabbages, onions, potatoes and swiss chard (commonly referred to as spinach).

Nombasa's family also owns an arable allotment but they have not cultivated it for some time. Her agricultural mainstay is her home garden. She sells some of her surplus to other people living in Guquka. She also owns a pickup truck, which gives her the option of selling produce in Alice. To produce a surplus she has to irrigate from the time the seedlings are planted out. She uses the communal standpipe system, leading water to her residential plot from it by means of a private connection in which she invested herself. This saves her the effort of carrying water in buckets from the standpipe, about 100 m up the hill from her house. She waters the seedlings with a hosepipe that she bought from a building wholesaler in Alice.

Mr Pazi is known as a good gardener and has been known to us ever since we started our longitudinal study in 1995 (Hebinck and Lent, 2007). Living in Guquka since 1960, Mr Pazi is 78 years old and still looks very strong. His garden is a productive one with an interesting design. It contains a water reservoir, with a capacity of 5.0 m3. The garden is neatly subdivided into small, more-or-less level plots, and along the edges of the garden he has planted a range of fruit trees including oranges, plums, peaches and prickly pear. Each tree is surrounded by a small ridge creating an impoundment to hold irrigation water. He also grows crops such as maize, cabbages and potatoes. Whenever his vegetables and trees suffer from water stress, Mr Pazi uses a hosepipe to siphon water from the reservoir to the plots and trees. This has enabled him to grow vegetables and fruit intensively. In 1998, he dug a second water harvesting reservoir above his garden and outside his residential plot. In case of heavy rainfall such a system could reach capacity and subsequently overflow. To stop this there is a drainage system throughout the home garden, but also directly from the reservoirs. He situated it so that it would collect runoff from the road running past his residential plot. From this new, unlined reservoir he siphoned water to the reservoir on his plot. When it became clear that the new reservoir significantly reduced the need for carrying water, Mr Pazi successfully requested permission from the Residents Association of Guquka to widen his residential plot.

He consumes the crops he cultivates himself, but also sells to others. Visiting Mr Pazi in early January 2014, we learned that his roadside water harvesting system has been overtaken by drawing water from the communal tap which is at the border of his residential plot. He says that the water is available and close by. In November 2015, we found him tapping water from the communal tap to fill up his reservoirs.

Ms Magatyeni is an active gardener. She is about 55 years old, married and mother of 4 children, who are employed or are looking for employment in Johannesburg, and grandmother of several grandchildren. She employs a range of different measures to improve her home garden. She was part of the Water Harvesting Project which started in 2005 and that lasted for 5 years. The water harvesting techniques, creating small ridges, were central to the project, as was the spacing of different crops, mulching and other information provided regarding home gardening. As part of the project seeds and rainwater tanks were also handed out; the latter are still in use and are connected to the roofs of the buildings on the plot. The difference noted since the intervention of the project is that: 'the methods I apply help my crops grow bigger, taste better and require less watering' (Magatyeni, 2012). Ms Magatyeni's home garden is about 20 m by 25 m and also contains some fruit trees. About a third of her garden is reserved for the cultivation of maize. The other two thirds is used for growing vegetables, such as potatoes, beetroot, tomatoes, cabbage, spinach (swiss chard), broccoli and cauliflower.

The use of the small ridges has diminished the amount of water that Ms Magatyeni requires to irrigate. However, she still irrigates, drawing water with hosepipes from the rainwater tanks that were given to her as part of the rainwater harvesting project, as well as from the communal standpipes. She and her husband tend the home garden and a pig sty and chicken coop themselves, sometimes helped by her children when they visit from Johannesburg. The produce feeds the family and is also sold to other people. Ms Magatyeni freezes bags of mixed vegetables. This allows her to use or sell her produce even when certain vegetables are out of season. When we met her again in November 2015, her garden did not look healthy. She had little time this year. Her husband passed away earlier in the year and she was preparing to travel to Grahamstown to celebrate the initiation of her grandson. Next year, she said, she will work hard to get her garden in shape.

CONCLUSIONS

These accounts of the use of water by homestead gardeners in Guquka provide evidence of a substantially different type of agriculture and irrigation from that championed by the NPC and most agricultural experts. It is small in terms of scale, often very small. The land is intensively cultivated by the family members living in the homestead. While only a handful of the 125 homesteads have intensified their home gardens, almost every homestead has access to one. This is in stark contrast to the arable allotments, which are seldom cultivated and often left fallow for years on end. New programmes and projects hoping to create a resurgence in large-scale agriculture in a village such as Guquka are akin to 'swimming against the tide. Of all the programmes and projects aimed at Guquka only one has endured: the communal standpipe system, although not in its original shape or form. Almost all intensive gardeners make use of the communal standpipe system to irrigate their home gardens even though water from the standpipes is officially reserved for domestic use. Hosepipes are officially not allowed by the WSA to be attached to the communal tap; one is also not allowed to wash at the stand-pipe. Only the use of buckets to obtain drinking water is permitted. This was made clear to the people of Guquka when the infrastructure was installed in 1994. As a safe measure to ensure this a committee was then installed to monitor water use (Van Averbeke and Bennett, 2007). The committee formally still exists but clearly is dysfunctional. From the interviews held during the many field visits it was unclear, when people in the village were asked, which government body or bodies installed the communal standpipes and more specifically which tier of government is responsible for supplying water and monitoring its use.

It is clear that the people have re-appropriated the communal water system in order to fit their own needs. 'Irrigation by night' is real and significant. The people require water for their home gardening or domestic uses but find that using buckets is a time-consuming manner of transporting water; carrying buckets back and forth is tiresome and hard work, especially for the elderly people in the village. Investing in hosepipes is a logical decision to make.

The water harvesting practices have discontinued, except for one homestead. This is a meagre outcome after 4 years of investment and training. One may argue, however, and question as Jonathan Denison does (Denison, 2015) whether the choice of water harvesting techniques was suitable for the predominant social, institutional and natural conditions in Guquka. This may have coloured the outcomes and long(er)-term impact of water harvesting. What seems to work well, however, and more importantly to endure, is the hosepipe system associated with the early RDP constructed piped water, albeit in a re-appropriated manner. Although piped water was not meant for productive consumption, it is a major resource for growing crops. A more abstract conclusion associates the use of piped water with the capacity (e.g. agency and creativity) to reassemble resources in other ways than designed. Without such an agency, food farming would have largely ceased to exist in villages like Guquka.

The relevance of such a conclusion is that assumptions made by experts, planners and policy makers alike need to be challenged and checked. Fortunately, this has been recognized at a national level by the DWA's National Water Resource Strategy (DWA, 2013). It, however, also acknowledges the shortcomings in the current approach to food farming in settings like Guquka: a fragmented reality and where various food-farming practices can be identified. Tugela Ferry in KwaZulu-Natal and Dzindi Irrigation Scheme in Venda exhibit similar dynamics (Cousins, 2013; Van Averbeke and Mohammed, 2006), each having their own locally specific dynamics and experiences. Some people grow food for their own consumption - the traditional home gardening practice. A few others have invested time and energy and expanded operations beyond the immediate needs of their homestead. Common to these in the Eastern Cape is the centrality of the piped water system which is what remains of the RDP. This type of intensive small-scale farming suits the needs of the home gardeners. The standpipe system is a widely distributed infrastructure that provides water for the needs of people, both for consumption and productive purposes. Although not officially allowed, re-appropriation of this infrastructure is inevitable. Acknowledging this would open the doors for a MUS approach to providing people with the tools and resources to improve their livelihoods.

The land and water use practices discussed in this paper underline the importance of adopting a multiple-use water systems (MUS) approach to supply water for both domestic, food production and animal water needs. By incorporating 'irrigation by night' and taking into account the confusion about current water governance structures, MUS emerges as a more flexible approach to water use planning in the context of poverty reduction, one which resonates more closely with current water use practices in rural villages in the Eastern Cape. This paper, however, makes clear that new policy initiatives and strategies to supply water to rural villages do not translate so easily and linearly from the level of the state to village or even homestead level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge copy-editing by Michael Wessels and professional and constructive comments by Jonathan Denison, Dik Roth and two anonymous reviewers on earlier drafts of the paper.

REFERENCES

ALIBER M and HALL R (2010) Development of evidence-based policy around small-scale farming. Report commissioned by the Programme to Support Pro-Poor Policy Development, on behalf of the Presidency. HSRC, Pretoria. [ Links ]

ALIBER M and HALL R (2012) Support for smallholder farmers in South Africa: challenges of scale and strategy. Dev. South. Afr. 29 548-562. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835x.2012.715441 [ Links ]

ANDREW M and FOX R (2004) Undercultivation and intensification in the Transkei: a case study of historical changes in the use of arable land in Nompa, Shixini. Dev. South. Afr. 21 687-706. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835042000288851 [ Links ]

CHAMBERS R (1986) Canal irrigation at night. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 1 45-74. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01422978 [ Links ]

CHAMBERS R (2013) Viewpoint - Ignorance, error and myth in South Asian irrigation: Critical reflections on experience. Water Alternatives 6 154-167. [ Links ]

COUSINS B (2013) Smallholder irrigation schemes, agrarian reform and 'accumulation from above and from below in South Africa'. J. Agrar. Change 13 116-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12000 [ Links ]

DWAF (Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, South Africa) (2007) Free Basic Water, Implementation Strategy 2007 - Consolidating and maintaining. Version 4. Directorate Policy and Strategy, DWAF, Pretoria. [ Links ]

DWA (Department of Water Affairs, South Africa) (2013) National Water Resource Strategy - Water for an equitable and sustainable future. Version 2. DWA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

DE KLERK H (2013) 'Still feeding ourselves': everyday practices of the Siyazondla Homestead Food Production Programme. In: Hebinck P and Cousins B (eds) In the Shadow of Policy: Everyday Practices in South African Land and Agrarian Reform. Wits University Press, Johannesburg. 231-247. [ Links ]

DE WET C (1989) Betterment planning in a rural village in Keiskammmahoek district, Ciskei. J. South. Afr. Stud. 15 326-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057078908708203 [ Links ]

DE WET C (2011) Where are they now? Welfare, development and mar- ginalization in a former Bantustan settlement in the Eastern Cape, post 1994. In: Hebinck P and Shackleton C (eds) Reforming Land and Resource Use in South Africa: Impact on Livelihoods. Routledge, London. 294-315. [ Links ]

DENISON J and WOTSHELA L (2012) An overview of indigenous, indigenised and contemporary water harvesting and conservation practices in South Africa. Irrig. Drain. 61 7-23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.1689 [ Links ]

DENISON J (2015) Personal communication (e-mail), 22 July 2015. Jonathan Denison, former Director of Umhlaba Consulting Group, 4 Pearce Street, Berea, East London, 5201. [ Links ]

DENISON J, PERRY A and MURATA C (2015) Water resources and productive use. In: Denison J, Murata C, Conde L, Perry A, Monde N and Jacobs T (eds) Empowerment of women through water use security, land use security and knowledge generation for improved household food security and sustainable livelihoods in selected areas of the Eastern Cape. WRC Report No. 2083/15. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. [ Links ]

FAIRHEAD J and LEACH M (2005) The centrality of the social in African farming. IDS Bull. 36 86-90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2005.tb00202.x [ Links ]

FAY D (2013) Cultivators in action, Siyazondla inaction? Trends and potentials in homestead cultivation. In: Hebinck P and Cousins B (eds) In the Shadow of Policy: Everyday Practices in South Africa Land and Agrarian Reform. Wits University Press, Johannesburg. 247-263. [ Links ]

GUTURA P and TANGA P (2014) the intended consequences of the social assistance grants in South Africa. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 5 659-700. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n2p659 [ Links ]

HEBINCK P and LENT P (eds) (2007) Livelihoods and Landscapes: The people of Guquka and Koloni and their resources. Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden/Boston. [ Links ]

HEBINCK P and MONDE N (2007) Production of crops in arable fields and home gardens. In: Hebinck P and Lent P (eds) Livelihoods and Landscapes: The people of Guquka and Koloni and their Resources. Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden/Boston. 181-221. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004161696.i-394.64 [ Links ]

HEBINCK P and SMITH L (2007) A social history of Guquka and Koloni: Settlement and resources. In: Hebinck P and Lent P (eds) Livelihoods and Landscapes: The people of Guquka and Koloni and their resources. Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden/Boston. 91-121. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004161696.i-394.37 [ Links ]

HEBINCK P and VAN AVERBEKE W (2013) What constitutes the agrarian in contemporary rural African settlements of the central Eastern Cape. In: Hebinck P and Cousins B (eds) In the Shadow of Policy: Everyday Practices in South Africa Land and Agrarian Reform. Wits University Press, Johannesburg. 263-281. [ Links ]

LUND F (2007) Changing Social Policy. The Child Support Grant in South Africa, HSRC Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

MADYIBI Z (2013) The Massive Food Production Programme: does it work? In: Hebinck P and B Cousins (eds.) In the Shadow of Policy: Everyday Practices in South Africa Land and Agrarian Reform. Wits University Press, Johannesburg. 217-231. [ Links ]

MAGATYENI M (2012) Personal communication (interview), 22 October 2012, at her home in Guquka. [ Links ]

MANYEVERE A, MUCHAONYERWA P, LAKER M and MNKENI P (2014) Farmers' perspectives with regard to arable crop production and deagrarianisation: an analysis of Nkonkobe Municipality, South Africa. J. Agric. Rural Dev. Trop. Subtrop. 115 41-53. [ Links ]

MINKLEY G (2012) Rainwater harvesting, homestead food farming, social change and communities of interests in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Irrig. Drain. 61 106-118. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.1684 [ Links ]

MONDE N and ALIBER M (2007) Multiple uses of water in rural areas of Central Eastern Cape: a case of three villages in Nkonkobe Municipality, Eastern Cape. Unpublished research report for WRC Project K5/1477. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. [ Links ]

MONDE N, BOTHA J, JOSEPH L ANDERSON J DUBE S and LESOLI M (2012) Sustainable Techniques and Practices for Water Harvesting and Conservation and their Effective Application in Resource-Poor Agricultural Production. WRC Report No. 1478/1/12. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. [ Links ]

MURATA C and DENISON J (2015) Land administration institutions and implications for women in agriculture at the research sites. In: Denison J, Murata C, Conde L, Perry A, Monde N and Jacobs T (eds) Empowerment of women through water use security, land use security and knowledge generation for improved household food security and sustainable livelihoods in selected areas of the Eastern Cape. WRC Report No. 2083/15. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. [ Links ]

NATIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION, SOUTH AFRICA (2011) National Development Plan 2030. Our Future - Make it Work. National Planning Commission, The Presidency, Pretoria. [ Links ]

PANT D, GAUTAM KR, SHAKYA SD and ADHIKARI DL (2006) Multiple use schemes: Benefit to smallholders. IWMI Working Paper 114. International Water Management Institute, Colombo. [ Links ]

PEIRES J (1981) The House of Phalo: A History of the Xhosa People in the Days of their Independence. Ravan Press, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

PENNING DE VRIES F and RUAYSOONGNERN S (2010) Multiple sources of water for multiple purposes in Northeast Thailand. IWMI Working Paper 137. International Water Management Institute, Colombo. [ Links ]

RDP (Reconstruction and Development Programme, South Africa) (1994) White Paper on Reconstruction and Development Programme. Notice no. 1954 of 1994. Government Gazette, 23 November 1994. Government Printer, Cape Town. [ Links ]

RSA (Republic of South Africa) (1997) Water Services Act. Act No. 108 of 1997. Government Printer, Cape Town. [ Links ]

SCOTT J (1998) Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale University Press, New Haven. [ Links ]

SHACKLETON R, SHACKLETON C, SHACKLETON S and GAMBIZA J (2013) Deagrarianisation and forest revegetation in a biodiversity hotspot on the Wild Coast, South Africa. Plos One 8 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076939 [ Links ]

STEIN R (2005) Water law in a democratic South Africa: a country case study. Texas Law Rev. 83 (7) 2167-2184. [ Links ]

TOMLINSON COMMISSION (1955) A summary of the findings and recommendations in the Tomlinson Commission report. South African Institute of Race Relations, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

VAN AVERBEKE W and J BENNETT (2007) Local governance and institutions. In: Hebinck P and Lent P (eds.) Livelihoods and Landscapes: The People of Guquka and Koloni and their Resources: Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden/Boston. 139-165. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004161696.i-394.49 [ Links ]

VAN AVERBEKE W and MOHAMMED S (2006) Smallholder farming styles and development policy in South Africa: the case of Dzindi Irrigation Scheme. Agrekon 45 136-157. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2006.9523739 [ Links ]

VAN AVERBEKE W, DENISON J and MNKENI P (2011) Smallholder irrigation schemes in South Africa: A review of knowledge generated by the Water Research Commission. Water SA 37 (5) 797-808. https://doi.org/10.4314/wsa.v37i5.17 [ Links ]

VAN AVERBEKE W and DENISON J (2013) Smallholder irrigation schemes as an agrarian development option for the cape region. In: Hebinck P and Cousins B (eds) In the Shadow of Policy. Wits University Press, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

VAN DER HORST B (2013) People, land and water. Irrigation? A socio- technical feasibility study for an irrigation system in Guquka, South Africa. MSc thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands. [ Links ]

Received 11 January 2016

Accepted in revised form 17 November 2016

* To whom all correspondence should be addressed. e-mail: paul.Hebinck@wur.nl