Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Water SA

On-line version ISSN 1816-7950

Print version ISSN 0378-4738

Water SA vol.42 n.4 Pretoria Oct. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/wsa.v42i4.10

A qualitative and quantitative analysis of historic commercial fisheries in the Free State Province in South Africa

LM BarkhuizenI, II, *; OLF WeylIII, IV; JG van AsII

IFree State Department of Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs, Private Bag X 20801, Bloemfontein, 9300, South Africa

IIDepartment of Zoology and Entomology, University of the Free State, P.O. Box 339, Bloemfontein, 9300, South Africa

IIISouth African Institute of Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB), Private Bag X 1015, Grahamstown, 6140, South Africa

IVCentre for Invasion Biology, SAIAB, Private Bag X 1015, Grahamstown, 6140, South Africa

ABSTRACT

There is a general lack of information on inland commercial fisheries in South Africa. The primary objective of this study was to provide a retrospective assessment of commercial fisheries in the Free State Province based on the assessment of catch data from fisheries operating for the period 1979-2014. Permits were issued for commercial operators on 11 dams but catch data were only available for Bloemhof, Kalkfontein, Gariep, Vaal, Erfenis, Rustfontein and Koppies Dams. A total of 9 036 t of fish were harvested over the 35-year period, equating to an average (± SE) of 282 ± 185 t∙yr-1. Catch composition differed between dams but comprised mainly of common carp Cyprinus carpio and the Labeos, Labeo capensis and Labeo umbratus. Based on an assessment of the available catch data, the only successful fisheries that were sustained for more than 10 years were on Bloemhof Dam (mean ± S.E.: 201 ± 25 t∙yr-1 since 1981) and Kalkfontein Dam, where 127 ± 30 t-yr-1 was harvested (by an operator from Bloemhof Dam). All other fisheries appear to have failed with individual enterprises lasting between 1 and 10 years and generally yielding less than 25 tyr-1 when operational. Success at Bloemhof Dam appears to have been dependent on the ability to harvest > 100 t∙yr-1 and the long-term fisheries experience of the operators.

Keywords: commercial, fisheries, catch, rates, composition, qualitative, quantitative, analysis

INTRODUCTION

There is significant political pressure to develop commercial fisheries on freshwater impoundments as vehicles for poverty eradication, employment generation and economic development in South Africa (see Britz, 2015; Britz et al., 2015). This is because inland fisheries are perceived to be poorly developed from a food security and harvesting perspective (for review see McCafferty et al., 2012). Despite periodic attempts to establish commercial fisheries, the lack of information on these initiatives and on actual harvests is a severe bottleneck to understanding the constraints to inland fisheries development (McCafferty et al., 2012). The Free State Province, unlike other provinces, has a relatively long history of approved commercial fishing on inland waters, with development attempts on 11 impoundments since 1979 (Fig. 1). According to provincial legislation of its environmental affairs department (NCO, 1969; NCR, 1983), permit conditions for commercial fisheries include prohibited species, size limit for some species, catch quotas, gear restrictions, access restrictions within protected areas, concession fees payable to government, boating regulations and the submission of catch returns. As these data have never been collated nor assessed, the primary objective of this paper was to provide a retrospective assessment of commercial fisheries in the Free State Province coupled with a retrospective assessment of the factors that resulted in successes and failures of individual enterprises. This first assessment of inland commercial fisheries in South Africa will be useful in developing guiding principles for inland fisheries development and the emerging inland fisheries policy (see Britz, 2015).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We consulted all provincial nature reserves and the permit office of the Department of Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs (DESTEA) of the Free State Province to determine whether historic catch data of commercial fisheries were available and, if so, to retrieve and digitize these data which included the total number and weight of each species landed. Permits to commercially harvest fishes had been issued for 11 dams, namely, Bloemhof, Kalkfontein, Koppies, Rustfontein, Erfenis, Gariep, Allemanskraal, Rhoodepoort, Krugersdrift, Witpan and Vaal Dams (See Fig. 1).

Exploratory analyses revealed that the quality of catch data varied between localities. For some impoundments monthly and actual disaggregated catch data were available in hard copy, while for others these data were available only as collated tables in internal reports. In some cases a lack of administration control and management resulted in incomplete datasets, despite reported attempts to develop fisheries. As a result of the variability in the quality of data, only catch data that had been reviewed by DESTEA reserve personnel were used for the assessment of catch and species composition. To complement permit and catch data, interviews were conducted with key informants. These included former and current reserve managers, as well as permit holders at Bloemhof and Gariep Dams.

RESULTS

Available data and permit conditions

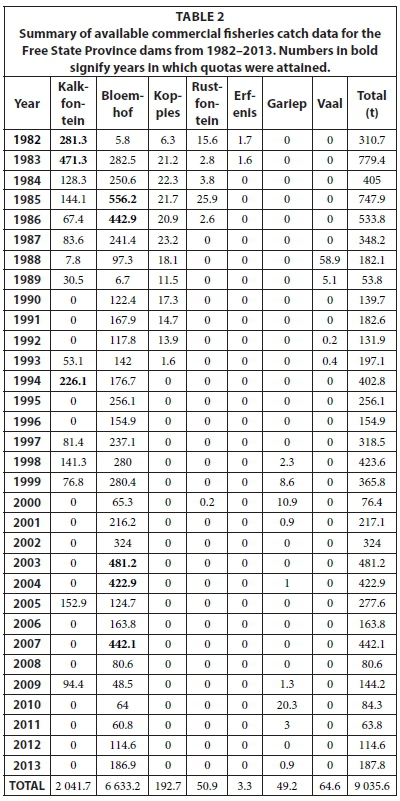

Of the 11 impoundments for which permits were issued, data on harvest were available for 7 impoundments. These were Bloemhof, Kalkfontein, Gariep, Vaal, Erfenis, Rustfontein and Koppies Dams (see Table 1).

All commercial fishing operations were managed and controlled based on permit conditions. These permit conditions included:

• Annual quotas ranging between 10 and 200 t∙yr-1 depending on operation and a concession fee based on catch volume payable to government.

• Immediate release of largemouth yellowfish Labeobarbus kimberleyensis and smallmouth yellowfish Labeobarbus aeneus. These two species are deemed protected species in the Free State Province and were never allowed to be caught and if killed had to be reported.

• Allowable gear, which from 1979 until 2005 included long lines, boat-based electro-fishers, gill nets with stretched mesh size of 100 mm and larger; seine nets with stretched mesh size of 50 mm and larger. Since 2005, only seine nets with a stretched mesh size of 50 mm and larger were allowed.

• Rules regarding entrance and access to fishing grounds within protected areas.

• Adherence to national legislation with regards to use of small vessels on inland waters according to the South African Maritime Safety Authority (SAMSA).

• The permit conditions stipulated that daily and monthly summaries had to be captured on prescribed record forms and submitted to reserve offices.

Harvest

A total of 9 036 t of fish were harvested over the 35-year period, equating to an average (±S.E.) of 282 ± 185 t∙yr-1. Catch composition differed between dams (see Table 1). At Bloemhof, Vaal and Gariep Dams catches comprised mainly of common carp Cyprinus carpio (> 53%), while in the other impoundments the Labeos, Orange River mudfish Labeo capensis and moggel Labeo umbratus, dominated (> 66%) catch assemblages. Based on an assessment of the available catch data, the only successful fisheries that were sustained for more than 10 years were on Bloemhof Dam (mean ± S.E.: 201 ± 25 t∙yr-1 since 1981) and Kalkfontein Dam, where 127 ± 30 t∙yr-1 was harvested (by an operator from Bloemhof Dam). All other fisheries appear to have failed with individual enterprises lasting between 1 and 10 years and generally yielding less than 25 t∙yr-1 when operational (see Table 2).

Commercial fisheries

Key informant interviews confirmed that most attempts at developing formal fisheries failed soon after their initiation (e.g. at Erfenis, Rustfontein and Vaal Dams). Interview data with the previous reserve manager at Koppies Dam, where a fishery operated for 12 years (1981-1993), revealed that this fishery closed down as it was no longer financially viable (Joubert, 2014).

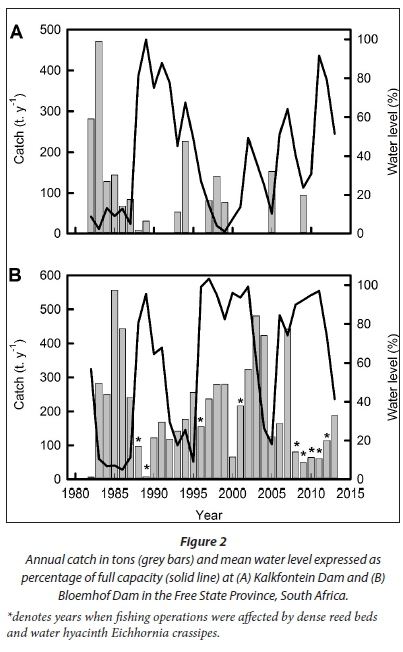

The success of the two operators at Bloemhof Dam appears to have been dependent on the ability to harvest > 100 t∙yr-1, and long-term fisheries experience. One of the operators (Master Fishing) had been in operation since the initiation of commercial fisheries on Darlington Dam in the Eastern Cape in the early 1970s from where he moved to Kalkfontein Dam (Bok, 2014) and subsequently to Bloemhof Dam after failed attempts to develop fisheries at Krugersdrift and Vaal Dams. This enterprise also supplemented catches by making opportunistic use of periodically available resources during low water levels at Kalkfontein Dam.

Comparison of catch and quota data for Bloemhof Dam operators demonstrates that the 200 t-yr-1 quota was almost never attained. Key informant interviews with the proprietors of these enterprises revealed that this was the result of constraints to their ability to process, store and sell their catch, as well as due to operational issues. For example, one operator who produced sun-dried salted fish which was exported via Cape Town to central Africa, reported erratic demand as a constraint. For the second operator, who mainly sold fresh and frozen fish, harvests were limited by refrigeration capacity and local demand for freshwater fish.

Both fisheries experienced major challenges to their operations as a result of water-level fluctuations (see Fig. 2) and invasive weeds. When the water levels at Bloemhof Dam were above 80%, seine netting was hampered by inundated terrestrial plants that colonised the exposed littoral zones during low water level. At full supply level, dense reed beds within the areas zoned for commercial fishing were flooded, making access to the water extremely difficult. Finally, the invasion and rapid spread of water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes posed further problems for the fisheries and restricted operations and affected catches in 1988, 1989, 1996, 2001 and 2008-2012 (Fig. 2).

Information on the number of people employed by the different commercial fisheries was scant. It could, however, be determined that no permanent jobs were ever created. Inspections at the two fisheries at Bloemhof Dam during 2011-2013 revealed that both fisheries employed casual labour. One fishery employed 8 people who were paid minimum wage (80 ZAR∙d-1) while the other enterprise employed from 8 to 12 people who were paid a commission based on the day's catch. When operational at Kalkfontein Dam, the fishery employed between 20 and 30 people on a temporary basis, but it is not known how much they earned.

State-supported fisheries

Attempts to develop a small-scale fishery at Gariep Dam make an interesting case study. After 2 independent attempts to develop fisheries failed, government provided support to 3 fisheries projects. None operated for more than a few months in the year and the total reported harvest for all initiatives was < 49.2 t. Although failures were for a variety of reasons, unrealistic expectations of yields, inadequate management capacity and market constraints all appear to have contributed towards these failures.

Analysis of the outcomes of the fisheries project initiated in 1998 at Bethulie near Gariep Dam, to provide employment for 50 people, provides further insights. The government grant included equipment and all infrastructure (fishing gear, a boat and a building for fish processing) to the value of 216 000 ZAR. An initial quota of 50 t∙yr-1 was allocated but operationalisation of the project proved problematic resulting in strict monitoring and record keeping from January to December 2000. Despite the 50 t∙yr-1 quota only 11.2 t of fish were harvested and sold at 1.90 ZARkg-1. The total income from selling fish was 21 438 ZAR and operating expenses for this period were 9 750 ZAR, leaving a balance of 11 688 ZAR for the project beneficiaries. By the end of 2000, only 12 people remained in the project which meant each had earned 81 ZAR∙month-1. Attempts to start similar projects in Venterstad and Oviston (Eastern Cape side of Gariep Dam) also failed despite considerable investment of more than 1 million ZAR over a 10-year period.

DISCUSSION

The retrospective analysis presented here, demonstrates that attempts to develop commercial fisheries in the Free State Province have largely failed. As the average harvests per impoundment were very low (< 33 kg-ha-1∙ y-1) when compared with the mean annual yield from other fisheries in small water bodies in southern Africa (329 kg∙ha-1∙y-1) (Marshall and Maes, 1994), failure was unlikely to have been as a result of overfishing but rather as a result of a failure of fisheries to yield the desired return on investment. Those fisheries that persisted did so as small-scale commercial enterprises that were unable to fill their relatively small quotas, nor were they able to provide full-time employment. This stark reality differs dramatically from the initial optimistic yields derived from empirical approaches used to estimate potential yields in the absence of a-priori catch data (e.g. Weyl et al., 2007; Britz et al., 2015). In the absence of data, the lack of developed commercial fisheries in South African dams has been misinterpreted as a result of restrictions to physical access, a lack of developmental initiatives and a lack of an enabling policy (Britz, 2015). The current assessment, however, demonstrates that opportunities to establish commercial fisheries in the Free State Province have been available for 35 years. Despite this, only 2 small-scale enterprises were financially sustainable and their operations have been severely constrained by environmental fluctuations, invasive weeds that impede harvest efficiency, small local markets and demand and fluctuations in export market demand. As a result, the contribution of small-scale commercial fisheries to employment and economic empowerment in the Free State Province has been limited.

A lack of an established market and low value of freshwater cyprinids is demonstrated by the low level of success by individual enterprises. Particularly interesting are the attempts to develop fisheries on Gariep Dam. Here a variety of attempts to develop fisheries failed. Despite information of prior failures of commercial enterprises, provincial government supported several community projects by providing support to development consultants, fishing gear, operation and labour cost. All attempts failed completely with a total combined harvest of only 49 t by all fisheries initiatives on the dam (see Table 2).

In contrast, surveys by Ellender et al. (2009; 2010a; 2010b) demonstrated that subsistence and recreational anglers harvested 80 t∙yr-1 from Gariep Dam and that some 448 people from the towns of Venterstad, Oviston, Bethulie and Hydropark regularly harvested fish from the dam for subsistence while using artisanal gear. These subsistence anglers sold excess fish at a relatively low price (6 ZAR∙kg-1), providing not only supplementary income for fishers but also an important source of low-cost protein to the predominantly poor population within the area. As a result of the importance of subsistence angling to food security in the local community, Ellender et al. (2010a) recommended caution when developing commercial fisheries as these could compete for fish and market share with an already vulnerable sector of the population.

It is also evident that fisheries are unlikely to provide permanent employment in rural communities. This is because even the two most successful operators only used casual labour because fluctuating harvests and relatively low catch value constrained permanent employment in these small enterprises.

Britz et al. (2015) concluded their report on the scoping study on the development and sustainable utilisation of inland fisheries in South Africa by noting that the value of inland fisheries does not lie with the tonnage of fish caught, but rather in the benefits it provides for the rural poor in sustaining their livelihoods. Due to the limited success of commercial fisheries in the Free State Province, it is the opinion of the authors that the development of formal commercial enterprises is unlikely to be successful. Instead, efforts should be made to better understand existing utilization and develop small-scale fisheries using technologies that are locally appropriate and affordable. While such informal uses are likely to be less popular with government than the formal 'project' approaches with clear-cut budget lines and monitorable indicators such as 'number of beneficiaries', prioritizing angling (both subsistence and recreational) could ensure the availability of these resources as food-security safety nets when needed and provide for employment in associated service industries. As subsistence fishers include some of the most vulnerable members of society (Béné et al., 2015), we agree with Ellender et al. (2010a) that subsistence and recreational angling should be prioritized with regards to an inland fisheries policy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

LMB thanks the DESTEA for support during the study on fish and inland fisheries in the Orange-Senqu River Basin. OLFW would like to thank the National Research Foundation (Grant No.77444); the DST/NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology and the Water Research Commission (WRC) solicited and funded 'baseline and scoping study on the development and sustainable use of storage dams for inland fisheries and their contribution to rural livelihoods' (WRC Project No. K5/1957/4) for support.

REFERENCES

BÉNÉ C, ARTHUR R, NORBURY H, ALLISON EH, BEVERIDGE M, BUSH S, CAMPLING L, LESCHEN W, LITTLE D, SQUIRES D and co-authors (2016) Contribution of Fisheries and Aquaculture to Food Security and Poverty Reduction: Assessing the Current Evidence. World Dev. 79 177-196. [ Links ]

BOK A (2014) Personal communication, 19 November 2014. Dr Anton Bok, Anton Bok Aquatic Consultants, 5 Young Lane, Mill Park, Port Elizabeth, 6001. [ Links ]

BRITZ PJ (2015) The history of South African inland fisheries policy with governance recommendations for the democratic era. Water SA 41 624-632. [ Links ]

BRITZ PJ, HARA MM, WEYL OLF, TAPELA BN and ROUHANI Q (2015) Scoping study on the development and sustainable utilisation of inland fisheries in South Africa. Volume 1: Scoping Report. WRC Research Report No. TT 615-1-14. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. [ Links ]

ELLENDER BR, WEYL OLF and WINKER H (2009) Who uses the fishery resources in South Africa's largest impoundment? Characterising subsistence and recreational fishing sectors on Lake Gariep. Water SA 35 677-682. [ Links ]

ELLENDER BR, WEYL OLF, WINKER H and BOOTH AJ (2010a). Quantifying the annual fish harvest from South Africa's largest freshwater reservoir. Water SA 36 45-51. [ Links ]

ELLENDER BR, WEYL OLF, WINKER H, STELZHAMMER H and TRAAS GRL (2010b) Estimating angling effort and participation in a multi-user, inland fishery in South Africa. Fish. Manage. Ecol. 17 19-27. [ Links ]

JOUBERT JJ (2014) Personal communication, 12 November 2014. Mr. Jacobus Joubert, Free State Department of Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs, Private Bag X 20801, Bloemfontein, 9300. [ Links ]

MARSHALL B and MAES M (1994) Small water bodies and their fisheries in southern Africa. CIFA Technical Paper 29. FAO, Rome. [ Links ]

MCCAFFERTY JR, ELLENDER BR, WEYL OLF and BRITZ P (2012) The use of water resources for inland fisheries in South Africa. Water SA 38 327-344. [ Links ]

NCO (Nature Conservation Ordinance) (1969) Nature Conservation Ordinance no. 8 of 1969. Orange Free State Provincial Government, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

NCR (Nature Conservation Regulations) (1983) Nature Conservation Regulations, Administrator's Notice184 of 12 August 1983. Orange Free State Provincial Government, Bloemfontein [ Links ]

WEYL OLF, POTTS W, ROUHANI Q and BRITZ P (2007) The need for an inland fisheries policy in South Africa: A case study of the North West Province. Water SA 33 (4) 497-504. [ Links ]

Received 7 April 2016

Accepted in revised form 6 September 2016

* To whom all correspondence should be addressed.