Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Water SA

On-line version ISSN 1816-7950

Print version ISSN 0378-4738

Water SA vol.40 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

ARTICLES

Who wants to be an agent? A framework to analyse water politics and governance

Richard Meissner

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), PO Box 395, Pretoria, 0001, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to introduce a framework to analyse water politics and governance. The framework has been constructed from a social constructivist perspective. This theory places attention on the role of normative aspects like ideology, values, interests and culture in politics. This means that a theory of international relations such as neorealism, neoliberalism or structuralism would be appropriate but limiting for the analysis of water politics, in terms of the range of actors, processes and issues focused on. The framework's niche lies in that it focuses attention on non-state actors. This carries the potential to widen the understanding of the role and involvement of such actors in water politics and governance. The framework has five components: description of the geographic area or issue; the actors involved in water politics and governance; the (hydropolitical) history of the issue; the actors' power to enable change; and the type of interaction between the actors. In order to illustrate the components, examples from South and Southern Africa, and specifically the Kunene, Limpopo, Okavango and Orange River basins are used.

Keywords: Water, politics, governance, agential power, river basin, authority, ideology, economy

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this paper is to introduce a framework to analyse water politics and governance in order to highlight aspects that are lesser known within the South African water discourse and to introduce and further a critical understanding of water issues. Water politics is defined as the authoritative allocation and/or use of international and national freshwater resources. Within this authoritative allocation, the relationships between states and non-state entities, such as individuals and interest groups, play an important role (Meissner, 1998a; Turton, 2002). In other words, it is not only state entities that are involved in water politics. This is also the case with governance. Governance is defined as the result of interactive socioeconomic and political forms of governing that result in problem solving and opportunity creation (Rhodes, 1996; Kooiman, 2008; Meissner, 2013). Considering these non-state-centric definitions of water politics and governance, the framework is flexible, dynamic and progressive, in the sense that it is applicable to any situation where actors collaborate or oppose each other in an issue area. An issue area can range from the functioning of wastewater treatment works in a municipality to the politics and governance in part of a river basin. The framework, apart from being an organising tool, assists in the identification of factors that influence the interaction between actors, the manner in which they govern systems and the socio-political variables that influence their conduct. This could be a valuable addition that could enrich the development of scenarios in the management of water resources and water services, especially where institutions need to deal with complexities, particularly in finding a balance between society's and the environment's water needs (Claassen et al., 2013).

For the framework to be dynamic and progressive, it is necessary to not construct it with a specific or dominant theoretical paradigm in mind. This means that a theory drawn from international relations, such as neorealism, neoliberal-ism or structuralism, would be appropriate but limiting in terms of the range of actors, processes and issues focused on. Such theories have a predominantly exclusive focus on state actors, the organisations they create, the treaties they sign and implement as well as the political elite that lead these institutions. This seems to be the predominant theoretical foundation used to do water research at the domestic level in South Africa. With respect to advancing understanding, doing research from such a foundation is unsatisfactory; a close link exists between theory and policy/decision making and if one theoretical paradigm dominates, policy makers do not have a variety of theoretical choices to base policy decisions on (George, 1994). This means that responses to problems and the generation of opportunities could fall short of expected returns. The framework presented in this paper has been constructed from a social constructivist perspective. This theory places attention on the role of normative aspects in politics, such as ideology, values, interests and culture.

Since the framework's objectives are to analyse, explain and predict interactions around issues, its constitutive elements must encapsulate this problematique (Meissner, 2004). This is the framework's niche - it presents alternatives to decision makers in the understanding of the politics and governance of water resource management. There are of course other frameworks. Franks and Cleaver's (2007) framework focuses on non-state actors from a sociology perspective to determine the impact of water governance systems on the poor (Franks and Cleaver, 2007). Said differently, frameworks for analysis have specific purposes based on the research agenda of the researcher(s). For instance, Ostrom's (2007) framework, in part, discounts the pervasiveness of panaceas or cure-alls in decision-making. The task of Schmeier's (2012) theoretical framework is to assess the various determinants of river basin organisation effectiveness in order to improve effectiveness where deficiencies exist. Zeitoun and Warner (2006) developed a framework to analyse transboundary conflict from a structural perspective. Their framework focusses to a large extent on the power relationship between states in transboundary river basins (Zeitoun and Warner, 2006).

Puchala (1971 p. 358) points out that 'a general theory of international politics [is] an inventory of dependent and independent variables, a series of process models and a set of statements about cause and effect'. This is also the case with a framework for analysis as well as the theoretical paradigms underlying such a framework. By identifying variables and statements concerning cause and effect, patterns are discerned in the interaction between actors. Expecting linear progression from one variable to the other, especially when including nonstate entities in the analysis of water politics and governance, can introduce blind spots in the analysis and understanding of water politics and governance. The reason for this is that states are not the only actors that possess 'agential power' (Hobson, 2007); they are not the only actors that play a meaningful role in governance and politics. Individuals can also posess agential power and exercise this to initiate change (Kerkvliet, 1995; Hobson, 2000; Meissner, 2004; Rosenau, 2008; Hobson and Seabrooke, 2007). The agency people exert can even exist in societies that are considered to be so dominated by the state that people and civil society are considered unable to exercise any meaningful power over state control processes (Kerkvliet, 1995; Meissner, 2005). The framework must therefore be as comprehensive as possible, and also make provision for the inclusion of other actors such as individuals, rural communities and tribal leaders, in order to highlight interactive processes. It also needs to consider the normative dimension of interactions such as beliefs and values.

Thower' outlined by Hobson (2000). The second part is a presentation of the suggested framework for analysis. The framework is divided into five components:

• description of the geographic area or issue

• the actors involved in water politics and governance

• the (hydropolitical) history of the issue

• the actors' power capabilities to enable change

• the type of interaction between the actors.

Throughout the paper, I will use examples from South and Southern Africa to illustrate some of the arguments in order to indicate what can be gained from the framework.

AGENTIAL POWER

Power is one of the most fundamental ideas in political inquiry (Rothgeb, 1993). Strange (1996 p. 12, 13) remarks that 'politics is a common activity; it is not confined to politicians and their officials.' The individual, sometimes belonging to a group, sometimes acting on his or her own accord, can also be the bearer of political power alongside bureaucrats and politicians. Despite this, can it be taken for granted that all actors have power in all situations? Who has more power and who has less in a given situation? This question is addressed in John M. Hobson's The State and International Relations. He bases his study on a formulation of different types of 'agential power' and how they relate to state and non-state entities (Hobson and Seabrooke, 2007).

Hobson's (2000) description and classification of 'agential power' are useful because they indicate how 'agential power' relates to the relationships between actors. Hobson (2000 p. 5-10) divides 'agential power' into two main categories: 'domestic agential power' and 'international agential power'. While Hobson mostly focuses on agential state power, this framework explores Hobson's definition with the assumption that agential power is in the hands of various other types of actors and not only the state. I will put his definitions differently, so that they will incorporate both state and non-state actors, but still capture the essence of agential power. I will, nonetheless, retain the distinction between domestic and international 'agential power'.

When an actor has domestic agential power it has the ability to develop domestic or foreign policy and shape the domestic realm, free of domestic social-structural requirements or the interests of other actors (Hobson 2000). International agential power concerns the ability of an actor to make foreign policy and shape the international realm, free of international structural requirements or the interests of other international actors (Hobson, 2000). Agential power gives actors agency to influence their environment and each other (Hobson and Seabrooke, 2007). In a broad sense, these definitions are similar to the idea of autonomy (Hobson, 2000 p. 5). Autonomy is a situation where an actor has sovereignty over its actions, when it is self-governed or self-determined (Reath, 1998). 'A very autonomous [actor], if there is such an entity, invariably acts as it chooses to act, and does not act when it prefers not to do so' (Nordlinger, 1981 p. 8). Autonomy varies over time and concerning specific policy issues. Put simply, the autonomy of an actor infers that an entity can act without interference from other actors.

For some analysts, a clear trade-off always exists between the amount of power held by non-state entities and that of the state; the one always has more power than the other (e.g. Earle et al., 2010). Following Hobson (2000), a 'structurationist' approach is applied in this framework, which encompasses a comprehensive 'both/and' understanding. The logic behind this approach rests on the premise that strong states and strong societies can exist at the same time and a more levelled playing field exists. There are no clear trade-offs of power capabilities between actors. Said differently, it is not always clear that what the one gains, the other loses. The way this logic can be imagined is to assume that actors possess 'embedded autonomy' or 'governed interdependence', which can also be referred to as 'reflexive agential power' (Hobson, 2000: 227). 'Reflexive agential power' hints at the 'ability of [an actor] to embed itself in a broad array of social forces...', that is class and normative structures. Hobson's idea of 'reflexive agential power' is that as an actor becomes more reflexive, its governing capacity grows, because it is less isolated from society and other actors. If, for instance, the state succeeds in broadening its network of collaboration with a comprehensive range of social forces and state and non-state structures, it increases its power. This is one way to indicate where the link between politics and governance lies with governance being the result of interactive socio-economic and political forms of governing (Rhodes, 1994) that result in problem solving and opportunity creation (Kooiman, 2008).

FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS

A number of components of the framework for analysis can be identified: delimitation and description of the geographic area; the actors involved in water politics and governance; the (hydropolitical) history of the river basin or issue area; the actors' power capabilities to enable change; and the type of interaction between the actors. These five components are sufficient in encapsulating the politics and governance of resource management. The intention of the framework is not to be the final word, so to speak, on the matter. This means that it can be further developed in future by other researchers that can mix and match these five components with other components. In addition, with these components in hand, a researcher would be able to get a nuanced sense of the factors having a bearing on actor relationships, as well as the relationship between human agents and the natural environment (Meissner, 2004), which should not be ignored in analyses of this nature.

The geographic area

The geographic area of the river basin, sub-basin or quaternary (i.e. smaller units of analysis) is used as the point of departure for the framework since important sources of water and other resources for society and the natural environment are located here. This is especially true for countries in semi-arid or arid regions such as South Africa. A quaternary catchment is the lowest and most detailed level of operational catchment in South Africa for general planning purposes (Midgley et al., 1994). The Department of Water Affairs (DWA) has delineated South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho, into 22 primary catchments. These have, in turn, been divided into secondary, tertiary and, finally, 1 949 quaternary catchments, interlinked and hydrologically cascading, ith an average surface area of 650 km2 (maximum 18 146 km2 and minimum 48 km2) (Schulze, 2006).

The geographical demarcation can highlight the river's unique characteristics. This distinctiveness indicates the purposes the river is used for such as the benefits derived from it (Sadoff and Gray, 2000). The geographical demarcation of river basins, sub-basins and quaternaries also provides an indicator of possible intervening variables tha impact on water scarcities or abundances. These variables include the climatological and hydrological characteristics of a system (Elhance, 1999). The biophysical environment can therefore be seen as an 'entity' that determines the politics and governance of the resources (Meissner, 2003) and can create opportunities to solve problems.

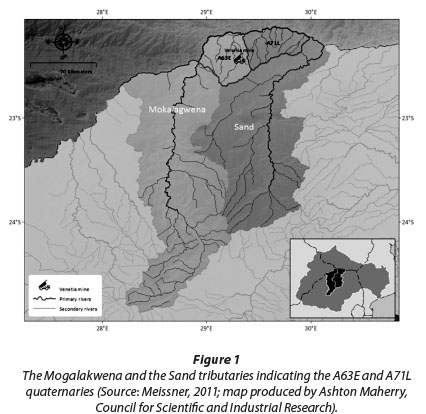

The geographical delimitation of sub-basins and quaternaries is included since the river basin would appear to no longer be the most appropriate unit of analysis; quaternary analyses can yield just as much information about water politics than if one were to research the entire river basin. For instance, in Quaternaries A63E and A71L in the South African portion of the Limpopo River basin (see the map below), the political interactions among actors are of such a nature that it is comparable to a larger geographical area (Meissner, 2011); that is if the focus of analysis include non-state actors, because as the number of actors increases, so too does the system's degree of complexity. It is, furthermore, important to look at sub-basins and quaternaries for a number of reasons:

• to understand complexities

• to reveal more issues and processes in the geographic area in question than would be readily visible when analysing the entire river basin

• to free the analyst from the constraints of geographical determinism and an explicit state-centric and top-down focus

•ironically, to enlarge the research space and reveal the presence of a more nuanced water politics and governance.

Actors

As indicated earlier, the demarcation of a geographic area gives an indication of the actors involved in the politics and governance of water resource management. These include sovereign states that share an international river basin, as well as other actors active within the basin including non-state entities such as interest groups, farmers, traditional leaders and multinational corporations. These actors are identified and classified according to three spheres of involvement: the actors in the core, semi-periphery and outer-periphery (see Fig. 2) (Meissner, 1998a) of the geographic or issue area.

Three sets of actors play a role in politics and governance. The first set comprises those actors who share the system or are directly involved in the issue. These can be riparian states but also communities living in, or interest groups active in, the river basin. The second set is made up of those actors within the region who are external to the area in question (but who are not outside the country wherein the basin or quaternary is located). These actors can either be other states or non-state entities, including individuals. The third set consists of those actors who are external to the area or system and operating within the international or global environment.

The actors can interact in a complex interdependent manner with each other when managing water resources (Meissner, 1998). For instance, interest groups can form an alliance amongst themselves to collaborate on or oppose a policy or they can unite with states to implement the policy. In the early 1990s, Botswana planned the implementation of the Southern Okavango Integrated Water Development Plan (SOIWDP). The plan was, however, shelved after the government was criticised by local and international interest groups, among them Greenpeace, for planning to implement the plan in the Okavango Delta (Neme, 1997, Meissner, 1998b; Heyns, 2003; Warner and Meissner, 2008). What should be noted though is that it is possible for interest groups and states to influence each other reciprocally, especially in cases where reflexive agential power is the order of the day. The influencing of the policy process does not always originate from civil society. If this is taken into consideration, the borders between the concentric rings not only start to blur but becomes misshapen as reciprocal influencing endeavours shape the actors in the different realms.

The (hydropolitical) history

A description of the (hydropolitical) history of the area or issue serves a number of purposes. It indicates which sets or types of actors are the most dominant in the system during certain periods, based on the nature and extent of the relationship between the actors over time. The (hydropolitical) history provides information about some of the interceding variables, such as a changed political environment, climate variability and the entry of aspirant stakeholders that have or could have a bearing on the system's performance. The history lastly connotes when and under which circumstances actors initiate influence during the policy process (Meissner, 2004). It should be noted that there is no prescribed time frame the researcher should use. The period to be considered depends on the researcher's research agenda.

This is vividly illustrated by the start of irrigation schemes on the Orange River in the latter part of the 19th Century. It is thought that the Dutch Reformed Church initiated the first irrigation system at Kakamas in 1883. Under the guidance of Reverend Christian Schröder an irrigation furrow was completed on 2 May 1885 and the missionary station was able to irrigate its gardens from the Orange River (Macdonald, 1913; Green, 1948; Hopkins, 1978, Turton et al., 2004; Van Vuuren, 2012). According to Legassick (1996: 371-372) 'In organising [the Upington canal's construction], Schroeder. ..took [his] lead from Abraham September, who had first led water from the Orange river'. It would appear that the Kakamas works were constructed after the Upington irrigation canal. According to the Standard Encyclopaedia of South Africa (1975 cited in Legassick, 1996 p. 372) 'Upington owes its prosperity mainly to agriculture and the development of irrigation along the Orange River. Here, at Upington, Schroeder as missionary among families of mixed European and other descent designed the first irrigation canal of the lower Orange River, a scheme so successfully applied at Kakamas in later years'. Legassick's (1996) research does not only indicate that previous historians were incorrect, but incorrect in a profound manner. Abraham September, as a non-white landowner and farmer, was most likely responsible for the first irrigation works on the Orange. What's more, an institution, the Dutch Reformed Church, took its cue from September indicating that the individual was the initial change-enabling agent.

AGENTIAL POWER DETERMINANTS

Because the exercise of 'agential power' is issue, time and situation related, different forms and sources of power concerning a policy issue or action will be used by actors. Stern (2000 p. 143-144) is of the opinion that, '[t]he problem with 'power' is that it has so many different connotations that no single and agreed meaning to suit all contexts and occasions is possible'. In this sense, power can indicate a relationship between actors on the international stage as well as other levels such as the domestic and quaternary. It is within this conceptualisation of power, as a relationship between actors, that the concept 'agential power' becomes relevant since 'agential power' is exercised in relationships and structures (Hobson, 2000; Meissner, 2004; Hobson and Seabrooke, 2007).

This framework employs Mann's (1993a) power determinants: ideological, economic and political power. These sources of power are able to bring about change or influence the policy implementation efforts of actors and will indicate how actors think about issues, and their motivations for policy implementation. Mann (1993a) believes that power sources or determinants can be autonomous. For instance, ideological power can be in the hands of non-state entities or individuals that possess little or no political power. Similarly, the political power of an actor does not mean that it will be endowed with ideological power. Mann (1993a) furthermore notes that in a specific societal context at a certain time more than one source of power might be manipulated by an entity. To reiterate, not all sources of power are ever in the hands of one actor or group of actors at the same time. The reason for this is that societies are interdependent and consist of various complex systems. In short, networks of power reach across geographical space and time, therefore preventing a single actor (individually or collectivity) from possessing all power sources at once (Haralambos and Holborn, 2000: 634).

Ideological power

An ideology is an action-orientated set of ideas that are the foundation for political activities or action (Heywood, 1997). The source of ideological power lies, firstly, in the human need to discover meaning in life, to allot norms and values, and to partake in aesthetic and ritual exercises. The control over an ideology that links meanings, values, norms, aesthetics and rituals conveys general social power (Mann, 1993a). Ideological power is diffused and develops an actor or organisation's inherent morale (Mann, 1993a). An ideology therefore acts as a medium that instructs entities on the moral stance they should take regarding certain actions. Ideology has a bearing on an actor's identity which in turn informs its policy actions.

Ideologies, in combination with doctrines, create the intellectual frame of reference through which decision makers perceive reality. A doctrine is part of an ideology, and, because of this, ideologies can rationalise and justify the choice of policy preferences. Furthermore, ideologies are legitimating emblems, by which a group or an individual sanctifies its activities (Holzner, 1972; Holsti, 1995). Ideologies demarcate interpretations of reality and values that serves as the claims for power and the activities of actors (Holzner, 1972). As such, ideology and political power are interrelated; realities construct ideologies and, in turn, influence the means, actors and circumstances through which policies are formulated.

Every actor within the system has an ideology that corresponds with its power base, success, economic level, internal structure and identity (Ennaji, 1999). In addition, discourses play an important role because they describe expressions of policy actions or influence that are seen as asymmetrical power relations in a system (Thompson, 1987). A discourse is the manner in which people converse about something or an action (Grint and Woolgar, 1992; Potter and Wetherell, 1994; Jägerskog, 2003). Discourse is an area where various relations of power between participants in a debate, over a certain issue, are enacted (Ennaji, 1999 p. 152). Korten (1990 p. 124) says that non-state entities and social movements are not motivated to act because of their budgets or organisational structure, but rather by ideas, or more precisely by a vision of a better world and future for people. Budgets and structures are resources to achieve an end. Vision finds expression within the discourse utilised by the actor.

An ideology-free discourse does not exist (Ennaji, 1999). Power, ideology and discourse are interrelated aspects within the debates between actors. For instance, interest groups started to voice their opposition towards the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) in the mid-1990s (Meissner, 2000). The moment they became involved, the discourse changed. No longer were water resource management projects like the LHWP predominantly viewed as benevolent and good in providing water to society. Interest groups started to question the viability of the LHWP and its benefits to both Lesotho and South Africa in general and the Lesotho communities that would be affected by the Project, in particular. The interest groups, ranging from churches to environmental interest groups, even advocated for water demand management to be implemented in South Africa's economic heartland, Gauteng, where most of the water from the Project would be used. This meant that citizens in both countries, as part of these groups and organisations, empowered themselves with alternative discourses, whereas in the past they unquestioningly accepted the knowledge forwarded by the governments, project planners and managers. This change in attitude towards the LHWP was therefore discursive (Meissner, 2004; Jacobs, 2012) with its source in the ideological stances of the interest groups and churches, representing the interests of the environment and the local communities and a vision of a 'better world' for the affected communities in Lesotho after they had been relocated.

How can the researcher ascertain influence through a specific ideology? He or she should consider the social-historical circumstances of collaborating and opposing actors, how they produce discourses and the nature thereof concerning a certain issue. Discourses are produced, distributed, and received by people who are located in particular social-historical circumstances. These conditions are characterised by certain institutional arrangements. In the words of one observer '[t]he study of ideology must be based on the social-historical analysis of the conditions within which forms of discourse are produced and received, conditions which include the relations of domination which meaning serves to sustain' (Thompson, 1987 p. 525). The researcher could also look at how actors articulate future visions or what they are striving for, in other words, their purpose for existing. Determining the ideological 'make-up' of an actor will be a primary diagnosis from which the researcher can do a more thorough analysis. Other sources of power, like economic and political power, will assist in 'painting' a fuller picture and it is here where budgets and structures, referred to above, start to play a meaningful role.

Economic power

Economic power originates from the necessity to abstract, transmute, disburse, and use natural resources (Mann, 1993a). Water is needed in every economic activity, for electricity generation, the production of food, manufacturing, and at the household level. Water is a natural resource with economic as well as environmental utility. This is enshrined in the Dublin Principles. The first principle states that, '[f]resh water is a finite and vulnerable resource, essential to sustain life, development and the environment.' The fourth principle regards the economic value of water: '[w]ater has an economic value in all its competing uses and should be recognised as an economic good' (GWP, 2003).

Because of water's status as an economic resource, it must be mobilised before it can be used in factories and homes, at least in the majority of societies. Infrastructure must be provided to move water from point A to B, and the water must be in a form that is suitable for different uses. Drinking water must be of a high quality, and this entails the cleansing of water by some means of purification. Whether it is a large dam or a new water network for a city, these infrastructural projects carry a cost. On top of these expenditures are the costs to establish a bureaucracy to facilitate and oversee the management of water resources. Such institutions are usually government departments. Examples are South Africa's Department of Water Affairs or parastatal and private water companies such as Rand Water and the Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority (TCTA). A resource, usually of a financial, technical and political character, is needed to mobilise another resource (Meissner, 2004), not to mention the required human resources.

A useful distinction here is first-order and second-order resources. A first-order resource is the basic primary resource and it is usually in its natural form. It can become either sparser or more abundant over time relative to population growth and climate variability. A second-order resource is the resource needed to transform the primary resource. Second-order resources also have an added dimension in that they also involve institutional arrangements to oversee the management of first-order resources. For instance, financial and technical (second order) resources are needed to build a hydro-electric power plant to use water (first order resource) for the production of electricity. This is usually done under the auspices of a government department (institutional arrangements) (Turton and Ohlsson, 1999; Meissner, 2004). Under this component the researcher needs to address a couple of questions. Does an actor have the financial resources to implement an infrastructural programme? How do non-state actors go about changing aspects in the economy of a society that will have a positive or negative bearing on the resource system? For instance, how much does a corporation invest in its water stewardship programme or interaction with other stakeholders in safeguarding an aquatic system? What are the financial costs of suspending the policy action or adding more components so that it complies with the wishes of other actors?

Political power

Mann's (1993b) idea of power as despotic and infrastructural power is instructive when investigating political power. I am using Mann's (1993b) categorisation since it is in line with Hobson's (2000) notion of 'reflexive agential power'. Despotic power refers to the 'range of actions that the elite is empowered to undertake without routine, institutionalised negotiations with civil society groups' (Mann, 1988 p. 5 cited in Hobson, 2000). It is argued that states with despotic power are weak because they are unable to reach the entire society and, to a certain extent, exist in isolation. Many modern states do not have high levels of despotic power; at the same time they have high levels of infrastructural power. The latter provides them with the means to rule more directly and effectively than ancient or medieval state entities that relied on the nobility (Hobson, 2000) as a power base.

Infrastructural power is 'the capacity of the state to actually penetrate civil society and to implement logistically political decisions throughout the realm' (Mann, 1988 p. 5; Mann, 1993a: 55 cited in Hobson, 2000). Infrastructural power can alternatively also be defined as power through or with, rather than power seen as contra or above civil society. States can possess an elevated governing capacity to such an extent that it is capable of extending its governing capacity into society to realise its policies (Hobson, 2000 p. 198, 199). Said differently, civil society is used as a conductor through which state policies can be realised. Civil society, in partnership with the state, helps to facilitate the formulation and implementation of policies. This is also the case for the relations between non-state actors engaging each other over a policy, especially in situations or contexts with minimal or no governmental presence.

The analyst should consider the regulatory mechanisms encouraging civil society to operate freely as well as those instruments that instil a respect for human rights. These instruments form the foundation for a civil society to operate freely, which is a critical element for the realisation of infrastructural power. If an actor does not respect the existence of another, it is highly unlikely that that actor will extend its governing capacity into the realm of the second actor. It is not enough to ascertain the existence of such mechanisms, how they manifest in society is also of importance and here the interaction between actors become important. What is also of significance in this regard is to investigate instances where partnerships between actors exist. The nature and extent of collaboration and/or contestation can give a first impression of such a relationship. What is important to consider here is that collaboration is not always the be-all and end-all or desirable end result. Through contestation actors can also create opportunities for solving problems.

When Namibia decided to construct the Epupa Dam, on the Kunene River (shared by Angola and Namibia), in the mid-1990s, the government initiated a feasibility study. The OvaHimba were stakeholders to be affected by the construction of the dam since they rely to a large extent on the river as a source of water and grazing for their cattle. Even so, and according the OvaHimba, the government did not appoint a credible liaison body to facilitate communication between them and the government. The responsibility eventually fell on a team from the University of Namibia to discuss compensation issues with the OvaHimba. However, the OvaHimba already had contact with the Legal Assistance Centre (LAC), a human rights interest group based in Windhoek and had established a 'relationship of trust' with the LAC. Instead of talking to the OvaHimba chief, Hikunimue Kapika, directly, the University team apparently by-passed Kapika and approached one of his councillors. The OvaHimba saw this as an effort to undermine the Himba traditional leadership (Stott et al., 2000). This resulted in a breakdown of communication between the feasibility study team and the OvaHimba. The consortium funding the study noted that this shortcoming can be laid before the door of the Angolan and Namibian governments since it was their responsibility to facilitate the community consultation process (Maletsky, 1998: The Namibian, 18 December 1998). There was therefore no regular consultation with the OvaHimba during the feasibility study phase (Meissner, 2004) and instead of getting buy-in from the OvaHimba; authorities got the cold shoulder for the project. Here despotic power was more prevalent than infrastructural power.

In summary, systems are primarily structured by enmeshed ideological, economic and political power. These sources of power do not subsist in a pure form. 'Actual power organisations mix them, as they are necessary to social existence and to each other' (Mann, 1993a p. 9). Said differently, the power sources exist in any type of organisation and are needed by such organisations to achieve their goals. Moreover, actors in governance systems sustain each other, but also use the sources of power available to them to undermine one another to further their interests and demands or collaborate on matters of mutual interest.

Nonetheless, the power sources determine the capabilities that actors have in a governance system. What should also be considered is the nature of interaction, or relationships, among actors (as noted above when discussing infrastructural power). This is significant because the power capabilities of an actor can be less important when the interaction among the actors is not considered. How actors respond to each other should also be taken into account when analysing their interactive behaviour. 'It can even be argued that, with respect to any situation, issue, or problem, boredom is bound to set in if analysis does not turn soon from capabilities to relationships' (Rosenau, 1990 p. 184). The following section says a bit more about what the researcher has to look for when analysing actor relations.

Interaction between the actors

Within a system, a number of actors can interact with one another in a variety of ways. In competitive situations, the accomplishment of objectives by one actor clashes with the fulfilment of goals by other actors. The concluding action that can develop can vary from the breakdown in communication to outright physical violence (e.g. war). Complementary actions between the actors facilitate or promote cooperation. This usually manifests in cooperative agreements, pacts, memoranda of understanding, memoranda of agreement and gentlemen's agreements. A mixture of both cooperative and competitive interactions between the actors is also possible. In such a situation, actors pursue a multiplicity of goals. Some aims are incompatible and can lead to competition or contestation, while others are in accord and are sought and attained through complementary endeavours (Puchala, 1971) with varying shades of grey in between.

In a similar vein, Soroos (1986 p. 6) remarks that '...politics is a rich and perplexing mixture of trends and counter-trends'. What he means by this is that for any given period, conflict and confrontation can exist alongside cooperation and accommodation. The three patterns of interaction will always be discernible within the dynamics of water politics and governance (Meissner, 1998).

How are these interactive patterns manifested? Efforts to control or influence, and the exercise of power regarding goals, develop in a relational context. A spectrum of control and change-enabling techniques can be discerned within a relational context at any level of governance and politics. 'Brute force and other forms of physical coercion are found at the former extreme, scientific proof and reason at the latter' (Rosenau,

1990 p. 182). Responses to control enabling techniques can also be placed on a spectrum. These range from full agreement and compliance, at the one end, to disagreement and defiance at the other. 'Between these two extremes lie such reactions as avoidance, disputation, delay, and counter-force. Somewhere in the middle of the [spectrum] are the responses of disinterest and apathy' (Rosenau, 1990 p. 185) (see Fig. 3).

It is important to note that actors are able to use these control techniques on each other or to change circumstances. This is also true for responses to these techniques. For instance, a coalition of interest groups can use scientific proof as a control technique in their relationship with a mining company to influence the company not to implement certain policies or to engage in cooperative endeavours. The particular company in question can respond either through disagreement and defiance or full agreement and compliance. It can also produce and disseminate scientific proof on reasons why the policy or programme should go ahead. This can evoke a response from interest groups either in the form of disagreement and defiance or full agreement. Control and change-enabling techniques beget responses to control techniques and vice versa. More than one technique can be employed at once or over time, and this is when the historical context becomes important to consider. By investigating the history of the issue, researchers are able to see how the relationship has changed over time. This will give an indication of the different internal and external variables that impact on the relations and how such relationships impact on the system.

Why is it important to identify the type of interaction between actors? If the kind of interaction is known, it will be possible to determine the nature and degree of the relationship between actors. To reiterate, the nature and degree of control or deviance vary constantly and are not the same at any given moment. To be sure, by identifying the degree of control it is possible to detect the overall relationship between actors over time. In a situation where Actor A does not comply with the control and change-enabling techniques of Actor B, they will have incompatible reasons for the implementation of a policy. In addition, it will help distinguish the point of view the actor is identifying with. This will furthermore indicate how resources are managed, and whose ideas prevail. In other words, the focus should be on the interests and issues of actors, and how they convert these interests and issues into control and change-enabling techniques (Rosenau, 1990).

More than that, one of the consequences of control relations is authority. Decisions are made and implemented through authority. Relationships of authority are those '...patterns of [an entity] wherein some of its members are accorded the right to make decisions, set rules, allocate resources, and formulate policies for the rest of the members, who, in turn, comply with the decisions, rules and policies made by the authorities' (Rosenau, 1990 p. 186). Authority relations are inherent in any group where people undertake collective activities (Rosenau, 1990). Yet, it should also be mentioned that the individual, either on his or her own or part of a collective, can enter and exit authority relations. Put in another way, it is not only within groups that authority relations subsist, but also outside and between individuals not part of groups (Meissner, 2004). In this regard, complexity thinking becomes apt to understand relations (Meissner, 1998), where individuals are nodes of interaction within and outside groups considered as systems of relations.

This is illustrated by the following example. In January 1998, the Highlands Church Action Group (HCAG), a Lesotho-based interest group, released a report on a survey that was conducted in the Lesotho Highlands Water Project area. The report concluded that 75% of the Highland villagers affected by the project believed that their standard of living had decreased since the start of the project. The report also noted that 40% of the 93 households surveyed claimed their grievances and compensation claims had not been addressed. Only two households were satisfied with the compensation (The Star, 21 January 1998; Business Day, 19 March 1998; Meissner, 2004). The HCAG commented on the findings that: 'The inaction on the cases shows, at best, a lack of co-ordination and organisation within the [Lesotho Highlands Development Authority (LHDA)] bureaucracy. At worst, it demonstrates a lack of respect for affected people as well as a lack of co-operation with non-government organisations' (The Star, 21 January 1998). Even so, the South African Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF) responded to this 'scientific proof' through disagreement, counter-force and disputation. The Department noted that it was satisfied that compensation was adequately addressed by the LHDA (The Star, 21 January 1998 p. 5; Meissner, 2004 p. 259). A survey conducted by the LHDA indicated that all but 14 of 679 complaints lodged in the Phase 1A area had been settled to the satisfaction of the parties concerned (The Star, 21 January 1998; Meissner, 2004).

CONCLUSION

The purpose of the framework is to facilitate analysis of the relationships between actors, in terms of their relative agential power vis-à-vis each other, in the politics and governance of water resource management. This will assist practitioners to think about water politics and governance in a more systematic way, since the framework highlights aspects that can be considered invisible in water issues. Said differently, the framework represents a more complete way of analysing water politics and governance. The examples used throughout the paper indicate that it is not only the state and its government apparatus that holds agential power. The individual, for example Abraham September, as well as interest groups, like the HCAG and communities such as the OvaHimba, can also have a change-enabling influence on water resource management. This does not mean that if these groups agential power is high, the state's agential power must be low. The 'structurationist' approach employed by Hobson (2000) notes that strong states and non-state entities can exist alongside each other and share the same geographical area. If actors choose to become reflexive, their agency might increase substantially. Also of importance is that the geographical demarcation at the start of an analysis does not necessarily have to be at basin level; it can also be at sub-basin and even the quaternary level.

The framework is not definitive or final. Even so, it is hoped that it will spur future research endeavours to concentrate not only on the state and its governmental apparatus in water resource management, but also on the role and involvement of non-state entities and even the individual. State-centric analytical lenses only paint a partial picture and at times can be downright misleading. Much knowledge and understanding can be gained by looking into the circumstances under which non-state entities and individuals engage the state over water resource management, not only from a scientific perspective but also from a policy development and implementation point of view. It is my contention that the first step in such an enterprise would be to move away from the utilisation of state-centric theories and to endorse a programme where other critical theories that highlight the role and involvement of non-state entities are employed. What's more, it might also be prudent to analyse the linkage between politics and governance in a more nuanced manner and to broaden our understanding of this relationship. The two processes seem mutually inclusive and feed off each other. The nature and extent of this symbiosis could also assist in broadening our knowledge base in the management of natural resources. Having said that, it is also hoped that the framework would find application in other spheres of resources management and not just water resources.

REFERENCES

BUSINESS DAY (1998) Social, environmental impact of second phase of Highlands Project questioned. Business Day, 19 March 1998. [ Links ]

CLAASSEN M, FUNKE N and NIENABER S (2013) Scenarios for the South African water sector in 2025. Water SA 39 (1) 143-150. [ Links ]

EARLE A, JÄGERSKOG A and ÖJENDAL J (2010) Introduction: setting the scene for transboundary water management approaches. In: Earle A, Jägerskog A and Öjendal J (eds.) Transboundary Water Management: Principles and Practice. Earthscan, London. [ Links ]

ENNAJI M (1999) Language and ideology: Evidence from media discourse in Morocco. Social Dyn. 25 (1) 150-161. [ Links ]

FRANKS T and CLEAVER F (2007) Water governance and poverty: a framework for analysis. Prog. Dev. Stud. 7 (4) 291-306. [ Links ]

GEORGE AL (1994) The two cultures of academia and policy-making: bridging the gap. Polit. Psychol. 15 (1) 143-172. [ Links ]

GWP (GLOBAL WATER PARTNERSHIP) (2003) Dublin Statements and Principles. Global Water Partnership, The Hague. [ Links ]

GREEN LG (1948) To the River's End. Howard B. Timmins Publishing, Cape Town. [ Links ]

GRINT K and WOOLGAR S (1992) Computers, guns and roses: What's social about being shot? Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 17 (3) 336-380. [ Links ]

HEYNS P (2003) Water-resources management in Southern Africa. In: Nakayama M (ed.) International Waters in Southern Africa. United Nations University Press, Tokyo. [ Links ]

HEYWOOD A (1997) Politics. Macmillan Press, London. [ Links ]

HOBSON JM (2000) The State and International Relations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

HOBSON JM and SEABROOKE L (2007) Everyday IPE: Revealing everyday forms of change in the world economy. In: Hobson JM and Seabrooke L (eds.) Everyday Politics of the World Economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

HOLLAND JH (1995) Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity. Addison-Wesley, Reading, M.A. [ Links ]

HOLSTI KJ (1995) International Politics: A Framework for Analysis. Prentice Hall International, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J. [ Links ]

HOLZNER B (1972) Reality Construction in Society. Schenkman Publishing Company, Cambridge, M.A. [ Links ]

HOPKINS HC (1978) Kakamas - from the Wilderness an Oasis (in Afrikaans). National Book Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

JACOBS IM (2012) A community in the Orange: the development of a multi-level water governance framework in the Orange-Senqu River basin in Southern Africa. Int. Environ. Agreements: Polit. Law Econ. 12 (2) 187-210. [ Links ]

JÄGERSKOG A (2003) Why States Cooperate over Shared Water: The Water Negotiations in the Jordan River Basin. Department of Water and Environmental Studies, Linköping University, Linköping. [ Links ]

KERKVLIET BJT (1995) Village-state relations in Vietnam: The effect of everyday politics on decollectivization. J. Asian Stud. 54 (2) 396-418. [ Links ]

KOOIMAN J (2008) Exploring the concept of governability. J. Comp. Polic. Anal. 10 (2) 171-190. [ Links ]

KORTEN DC (1990) Getting to the 21st Century: Voluntary Action and the Global Agenda. Kumarian Press, West Hartford. [ Links ]

LEGASSICK M (1996) The will of Abraham and Elizabeth September: The struggle for land in Gordonia, 1898-1995. J. Afr. Hist. 37 371-418. [ Links ]

MACDONALD W (1913) The Conquest of the Desert. T.W. Laurie Ltd., London. [ Links ]

MALETSKY C (1998) Epupa study incomplete. The Namibian, 18 December 1998. URL: http://www.namibian.com.na/Netstories/Environ10-98/epupa1.html (Accessed 31 July 1999). [ Links ]

MANN M (1993a) The Sources of Social Power, Volume II: The Rise of Classes and Nation-States, 1760-1914. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

MANN M (1993b) The Sources of Social Power, Volume I: A History of Power from the Beginning to A.D. 1760. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

MIDGLEY DC, PITMAN WV and MIDDLETON BJ (1994) Surface Water Resources of South Africa 1990, User's Manual. Water Resources 1990 Joint Venture. WRC Report No. 298/1/94. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. [ Links ]

MEISSNER R (1998a) Water as a source of political conflict and cooperation: A comparative analysis of the situation in the Middle East and Southern Africa (in Afrikaans). Master's thesis, Rand Afrikaans University (RAU), Johannesburg. [ Links ]

MEISSNER R (1998b) Piping water from the Okavango River to Namibia - The role of communities and pressure groups in water politics. Global Dial. 3 (2) 5-7. [ Links ]

MEISSNER R (2000) In the spotlight... Interest groups as a role player in large water projects. SA Waterbulletin 26 (2) 24-26. [ Links ]

MEISSNER R (2003) Interaction and existing constraints in international river basins. In: Nakayama M (ed.) International Waters in Southern Africa. United Nations University Press, Tokyo. [ Links ]

MEISSNER R (2004) The transnational role and involvement of interest groups in water politics: a comparative analysis of selected Southern Africa case studies. D.Phil Dissertation: University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

MEISSNER R (2005) Interest groups and the proposed Epupa Dam: Towards a theory of water politics. Politeia 24 (3) 354-369. [ Links ]

MEISSNER R (2011) The institutional context and governance system in the upper Limpopo River basin, South Africa. Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Pretoria. [ Links ]

MEISSNER R, FUNKE N, NIENABER S and NTOMBELA C (2012) The Status Quo of Research on South Africa's Water Management Institutions: What do we know and where to from here? Report No.: CSIR/NRE/ECOS/IR/2012/0012/C. Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Pretoria. [ Links ]

MEISSNER R (2013) PULSE3: A governance assessment framework and its application to selected waste water treatment works in the Greater Sekhukhune District Municipality, South Africa. Report No.: CSIR/NRE/WR/IR/2013/0038/A. Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Pretoria. [ Links ]

NEME LA (1997) The power of a few: Bureaucratic decision-making in the Okavango Delta. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 35 (1) 37-51. [ Links ]

NORDLINGER EA (1981) On the Autonomy of the Democratic State. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, M.A. [ Links ]

OSTROM E (2007) A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104 (39) 15181-15187. [ Links ]

POTTER J and WETHERELL M (1994) Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitude and Behaviour. Sage Publications, London. [ Links ]

PRANGER RJ (1988) Introduction: Ideology and power in the Middle East. In: Chelkowski PJ and Pranger RJ (eds.) Ideology and Power in the Middle East: Studies in Jonour of George Lenczowski. Duke University Press, Durham.

PUCHALA D (1971) International Politics Today. Dodd, Mead and Company, New York. [ Links ]

REATH L (1998) Autonomy, ethical. In: Craig E. (ed.) Routledge Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. Vol. 2. Routledge, London. [ Links ]

RHODES RAW (1994) The hollowing out of the state: the changing nature of the public service in Britain. Polit. Q. 65 (2) 138-151. [ Links ]

RHODES RAW (1996) The new governance: governing without government. Polit. Stud. XLIV 652-667. [ Links ]

ROSENAU JN (1990) Turbulence in World Politics: A Theory of Change and Continuity. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. [ Links ]

ROSENAU JN (2006) The Study of World Politics, Theoretical and Methodological Challenges, Volume 1. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon. [ Links ]

ROSENAU JN (2008) People Count! Networked Individuals in Global Politics. Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, Co. [ Links ]

ROTHGEB JM (1993) Defining Power: Influence and Force in the Contemporary International System. St Martin's Press, New York. [ Links ]

SADOFF C and GREY D (2002) Beyond the river: the benefits of cooperation on international rivers. Water Polic. 4 389-403. [ Links ]

SCHMEIER S (2012) Navigating cooperation beyond the absence of conflict: mapping determinants for the effectiveness of river basin organisations. Int. J. Sustainable Soc. 4 (1/2) 11-27. [ Links ]

SCHULZE RE (ed.) (2006) South African Atlas of Climatology and Agrohydrology. WRC Report No. 1489/1/06. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. [ Links ]

SOROOS MS (1986) Beyond Sovereignty: The Challenge of Global Policy. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, South Carolina. [ Links ]

STANDARD ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF SOUTHERN AFRICA (1975) Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa NASOU, Cape Town. [ Links ]

STERN G (2000) The Structure of International Society: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations. Pinter, London. [ Links ]

STOTT N, SACK K and GREEFF L (2000) Once there was a community: Southern African hearings for communities affected by large dams. Environmental Monitoring Group, Cape Town. [ Links ]

STRANGE S (1996) The Retreat of the State: The Diffusion of Power in the World Economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

THE STAR (1998) Row shrouds SA, Lesotho water project. The Star, 21 January 1998. [ Links ]

THEUNISSEN CA (1998) Administering national government. In Venter AJ (ed.) Government & Politics in the New South Africa. J.L. van Schaik, Pretoria. [ Links ]

THOMPSON JB (1987) Language and ideology: A framework for analysis. Sociol. Rev. 35 (3) 516-536. [ Links ]

TURTON AR and OHLSSON L (1999) Water scarcity and social adaptive capacity: Towards an understanding of the social dynamics of managing water scarcity in developing countries. Paper presented at the Stockholm Water Symposium, 9-12 August 1999, Stockholm. [ Links ]

TURTON (2002) Hydropolitics: The concept and its limitations. In Turton A and Henwood R (eds.) Hydropolitics in the Developing World: A Southern African Perspective. African Water Issues Research Unit, Pretoria. [ Links ]

TURTON AR, MEISSNER R, MAMPANE PM and SEREMO O (2004) A hydropolitical history of South Africa's international river basins. WRC Report No. 1220/1/04. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. [ Links ]

VAN VUUREN L (2012) In the Footsteps of Giants - Exploring the History of South Africa's Large Dams. Water Research Commission, Pretoria. [ Links ]

VIOTTI PR and KAUPPI MV (1999) International Relations Theory: Realism, Pluralism, Globalism, and Beyond. Allyn and Bacon, Boston. [ Links ]

WARNER JF and MEISSNER R (2008) The politics of security in the Okavango River basin: From civil war to saving wetlands (1975-2002) - a preliminary security impact assessment. In: Pachova NI, Nakayama M and Jansky L (eds.) International Water Security: Domestic Threats and Opportunities. United Nations University Press, Tokyo. [ Links ]

ZEITOUN M and WARNER J (2006) Hydro-hegemony - a framework for analysis of trans-boundary water conflicts. Water Polic. 8 435-460. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Richard Meissner

+27 12 841 3696 /+27 71 677 6262

e-mail: RMeissner@csir.co.za

Received 17 September 2012

Accepted in revised form 2 December 2013