Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.20 no.2 Meyerton 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcman1006.214

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Institutional factors influencing post-graduate students' loyalty to their university

Tanna ColletI; Zoe PaparasII; Aaron KoopmanIII; Priya RamgovindIV,

IMarketing Department, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. Email: tanna.collet@gmail.com

IIMarketing Department, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. Email: zoepaparas@gmail.com

IIIMarketing Department, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. Email: aaron.koopman@wits.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2196-459X

IVFaculty of Commerce, The Independent Institute of Education, South Africa. Email: pramgovind@jie.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3171-7050

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: The turbulent global higher education sector poses significant marketing, branding and management challenges to institutions. In South Africa, the development of new institutions like Sol Plaatje University and the University of Mpumalanga has increased competition in the market, increasing pressure on universities to retain high-performing students in a bid to grow. This study investigates the institutional factors influencing post-graduate students' university loyalty. It examines the relationship between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, expenses and grants, facilities and physical environment, career prospects, and sports on university loyalty through the mediating role of attitude

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: Data for this quantitative study were gathered from 150 post-graduate students at the University of the Witwatersrand through a close-ended questionnaire. Data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Science 27 (SPSS), whereby various reliability and validity tests were conducted. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was then used to test the hypotheses

FINDINGS: The results obtained indicate a positive and significant relationship between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, and career prospects and attitude towards the university. A positive and significant relationship was observed between attitude towards the university and university loyalty

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: Universities should focus on enhancing their reputation and offering cutting-edge academic programmes that are considerably different from those offered by competitors. Quality and competencies of academic staff and maintaining academic excellence must be emphasised. This will encourage recruiters to seek graduates from the institution, resulting in greater career prospects for students

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: By concentrating on the university's reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, and providing qualifications that lead to good job prospects, positive student attitudes towards the university and, by extension, loyalty will be ensured. This will ensure that universities retain some of their high-performing students

JEL CLASSIFICATION: I23, M31

Keywords: Attitude; Higher Education; Loyalty; Post-graduate students; University Marketing

1. INTRODUCTION

The higher education market can be characterised as complex, as institutions are confronted with challenges like global competitiveness, mobility, impact, reputation, and relevance (Govender & Nel, 2021). Despite these challenges, universities are still recognised as key participants in stimulating economic growth and socio-economic development through their ability to conduct relevant research and provide knowledge and skills required in knowledge-based economies (Govender & Nel, 2021). However, with research funds from the government reduced partially to cater for the movement to remote teaching and learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Nordling, 2021) and the intense competition between public and private institutions, added pressure has been placed on universities to attract high-performing students (Musselin, 2018) and staff (Draisey, 2016).

Higher education marketers have traditionally relied on marketing and communication strategies, like brochures, college/university fairs, and websites. However, social media tools such as Facebook, Instagram and YouTube are being increasingly used to promote engagement and communicate the benefits of enrolling at a given institution to young, prospective students (Kumar & Raman, 2020). Nevertheless, students' loyalty to their university is dependent on the development of positive attitudes and emotions towards the institution, which is influenced by the broader university community (Vianden & Barlow, 2014). This shifts the focus to policy makers of educational institutions to find ways to increase student loyalty (Austin & Pervaiz, 2017). By knowing the antecedents of student loyalty, university management will be able to devise policies that result in student retention (Ali & Ahmed, 2018).

Research conducted by Stephenson et al. (2016) concludes that while the branding of a university is a crucial tool in attracting prospective students, other influential factors like facilities, the quality of lecturers, reputation and funding is vital for students to remain loyal to their university. Inasmuch as there is existing literature on student loyalty, the examination of institution-specific factors is considerably rare within the context of postgraduate students in a higher education institution, even more so in the South African context, warranting a need for this investigation.

The sections that follow provide an in-depth discussion of relevant literature that contribute to the researchers' holistic understanding of the constructs under investigation. In addition, the research instrument, data collection process and data analysis will be discussed. Finally, the results of the study will be depicted where relevant conclusions, managerial implications and contributions can be drawn, and areas for further research provided.

2. RESEARCH PROBLEM AND PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

Universities are competing on a national and international scale to attract an elite group of the highest-performing school leavers (Doherty, 2017). To this end, several institutions have embarked on the development of sustainable brand strategies to communicate their unique strengths (Pinar et al., 2020). Whilst brands represent the consumers' perceptions and feelings about a product and its performance, their value is often determined by their ability to ensure customer preference and loyalty - the result of which can lead to profitable customer relationships (Pinar et al., 2020).

With students having more alternatives, they need more information to make an informed decision regarding their tertiary education. Such information can include the available courses, overall academic quality, reputation, location, the institution's infrastructure, costs, career prospects and the quality of life during studies (Le et al., 2019). The aforementioned factors highlight the need for institutions to evaluate their brand internally and assess the educational experiences they provide, as characteristics not related to the core university offerings are used to assess an institution (Le et al., 2019).

Existing literature on students' choice of institution has been conducted in several parts of the world, including Canada (James-MacEachern & Yun, 2017), New Zealand (Ali & Hu, 2022), Indonesia (Kusumawati, 2019), Malaysia (Moorthy et al., 2019), the United Kingdom (Winter & Chapleo, 2015; Callender & Melis, 2022) and Ireland (Walsh & Cullinan, 2017). These studies focus on factors that attract students to a university, not necessarily the institutional influences that lead to university loyalty. Furthermore, these studies focus on school leavers or undergraduate students and not necessarily post-graduate students, who are largely different. This study responds to the knowledge gap by empirically investigating the influence of reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, expenses and grants, facilities and physical environment, career prospects, and sports on university brand loyalty through the mediating role of attitude towards the university.

The study also contributes to the literature on student choice and university brand loyalty by providing empirical evidence on the relationships between the various independent variables (reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, expenses and grants, facilities and physical environment, career prospects, and sport), and student attitude towards the university and university loyalty. The study will benefit university management by providing scientific evidence on which institutional factors result in post-graduate students having more favourable attitudes towards their university and, by extension, leading to university loyalty.

3. LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature review will discuss the influence certain variables have on post-graduate students' loyalty to their chosen university, as illustrated in the conceptual model. This research is grounded in existing literature from Chapman (1981), Spearman et al. (2016), and Erdogmus and Ergun (2016), who conducted an empirical study to understand the relationship between university performance and university brand loyalty. The current study investigates the influence that six independent variables, namely reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, expenses and grants, facilities and physical environment, career prospects (post-qualification), and sport, have on post-graduate students' loyalty to the University of the Witwatersrand, through the mediating role of students' attitude towards their university.

3.1 Higher education

The South African post-school education and training market encompasses 150 private and public higher education institutions, more than 50 Technical, Vocational Education Training (TVET) colleges, 29 Community Education and Training colleges, as well as 9 private colleges. Cumulatively, these institutions serve almost two million students (Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET), 2020). These figures are likely to increase annually to meet government plans and objectives of increasing university enrolments from 1 074 912 in 2019 to 1.5 million by 2030 (DHET, 2020).

South African students entering post-school education do so from a multitude of positions in terms of class, secondary schooling, race, and financial resources (Tewari & Ilesanmi, 2020). Despite there being active initiatives in post-apartheid South Africa, such as policy reform, transformation, and various financial aid schemes, there remain barriers to gaining access to the post-school sector and achieving success in the system (Groener, 2019). Post-apartheid, South African higher education institutions had to make a conscious effort to recalibrate their practices to redress past injustices while cultivating a competitive environment for teaching and learning (Singh, 2017). The Times Higher Education (2022) notes that South Africa's diverse, multi-faced population comprising individuals from different backgrounds, views, values and expectations requires an education system that produces global graduates that are multicultural in their competitiveness.

The South African post-school education sector is experiencing a significant increase in the number of registered students year after year, with a growing number of students expressing the need to "go to university" to "get a degree" (Viljoen, 2018:1). The drive of students entering the post-school education sector can be associated with their motivation to learn, levels of prior achievement, goals, interests, abilities, and subject matter choice (Tj0nneland, 2017). However, there are additional challenges that South African students face, given that the South African higher education sector has historically been plagued with challenges associated with access, equity, and infrastructure (Mlachila & Moeletsi, 2019). Despite policies allowing for widening access to participation, there is still a significant number of students that drop out as a result of finances, social circumstances, health, poor qualification choice and maladjustment (Groener, 2019). It is evident that the South African post-school sector is dynamic, multifaceted, and vast in its ability to address historic social challenges and the current needs of students entering the sector.

Various factors influence a potential student when choosing a graduate school, which culminates in assessing information and qualification characteristics as well as determining if these align with the personal needs and requirements of the student. The factors impacting a student's choice will vary based on age, experience, personal obligations, professional requirements, as well as financial constraints (Moorthy et al., 2019). Therefore, graduates are faced with legacy challenges present in the South African post-school environment, as well as compounding challenges associated with post-graduate studies. Some of these challenges are attributed to the availability of financial aid and resource allocation, which has greatly influenced enrolment patterns, in turn impacting the ability of an institution to manage the quantity and quality of post-graduate students (Mlachila & Moeletsi, 2019).

Furthermore, with the development of new learning alternatives and growing internationalisation comes increased levels of competition, adding more importance to understanding the behaviour and university choice of graduates (Toledo & Martinez, 2020). Amidst these changes in the South African higher education environment and the various challenges faced by institutions (some exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic), universities not only focus on attracting new students but retaining existing students and graduates (Abreu Pederzini, 2016; Toledo & Martinez, 2020; Centre for Global Higher Education, 2022).

3.2 Post-graduate students

There is consensus that higher education provides graduates with a route towards higher-paid jobs in the private and public sectors. However, universities face major challenges in providing access to the poor and reducing high dropout rates (Tjonneland, 2017). These challenges are linked to the wider economic and social problems facing South Africa (Tj0nneland, 2017) and will affect a student's success and continuation of tertiary education (Toledo & Martinez, 2020). Garcia and Sosa-Fey (2020) indicate that post-graduate students come from various backgrounds and place significant importance on their educational experience. The study conducted by Rehman et al. (2020) concluded that the quality and effectiveness of teaching and learning strategies and approaches are underlying factors in retaining post-graduate students. This viewpoint is supported by Setiawan et al. (2020), who highlight the importance of academic factors on student retention.

While there is consensus on the importance of academic factors in retaining students, there is evidence to suggest a lack of diversity amongst post-graduate students in South Africa. While the University of the Witwatersrand's 2020/2021 Facts and Figures report indicates racial diversity in the institution, with 60.63 percent of the 40 669 registered students being black African, 14.80 percent being white, 11.33 percent being Indian, 3.92 percent being coloured, 0.34 percent being Chinese, and 8.96 percent being international students (University of the Witwatersrand, 2022), The Mail and Guardian (2015), states that these statistics are largely different at a post-graduate level with more than half of South Africa's post-graduate students being white. Tjonneland (2017) positions that white males, in particular, are the dominant demographic group amongst postgraduate students. These statistics are indicative of demographic differences between postgraduate and undergraduate students, in addition to their personas and academic skills.

Post-graduate students are recognised as creators of knowledge who are motivated to engage in deeper, more critical learning through the process of asking relevant questions, seeking answers, and evaluating findings (Garcia & Sosa-Fey, 2020). Furthermore, smaller class sizes, as is the case with post-graduate courses, result in students being more active participants in the learning process, demonstrating higher levels of self-motivation and taking responsibility for their own learning experience (Williamson & Paulsen-Becejac, 2018) and, in doing so, are more likely to benefit from learning management systems (LMSs) which encourage interaction and reflection beyond the traditional classroom (Washington, 2019). In comparison, undergraduate students, whose academic skills are still developing, are described as consumers of knowledge (i.e., information gatherers) (Garcia & Sosa-Fey, 2020). The structure of their courses, the assessment methods used, and the expectations placed on undergraduate students differ, too (MANCOSA, 2019).

Despite the differences between post-graduate and undergraduate students, universities are striving to reduce student erosion as it affects the institution's reputation and finances and has adverse effects on communities and the workforce (Setiawan et al., 2020). Student retention and loyalty can be attributed to a host of reasons, and universities are encouraged to adopt a customer-centric approach by focusing on institutional factors that lead to loyalty.

3.3 University loyalty

Mulyono et al. (2020) indicate a correlation between loyalty and student satisfaction, where a positive relationship between these variables is an indication that students are satisfied with the qualification experience and quality of university facilities. The University of the Witwatersrand students are renowned for their innovative and creative skills, which serve as retention characteristics. This is evidenced by the institution, in that it projects that by 2025 post-graduate students will account for 45 percent of the student body (University of the Witwatersrand, 2022). This figure is dependent on the university's ability to retain its highest-performing students.

Brand loyalty fosters the continuation of the consumer lifecycle, consumer advocacy and positive word of mouth (Erdogmus & Ergun, 2016). As a result, universities are increasingly utilising branding as a means of establishing and creating a position in the market, increasing rankings, enhancing the career prospects of their graduates, as well as increasing the number of student applicants. Therefore, it is critical for a university to initiate effective ways to identify, attract, retain and foster robust relationships with students to create university loyalty (Erdogmus & Ergun, 2016).

3.4 Theoretical framework

A student's socioeconomic status (SES), attitudes, and various behaviours are critical when identifying an appropriate institution. Chapman's (1981) study includes the SES model, which indicates a positive relationship between educational aspirations and expectations of higher education institutions. While the influence of family and peers cannot be discounted and plays a vital role in the choice of institution, a study of six private higher education institutions (PHEIs) in Zimbabwe by Garwe (2014) reveals that access and opportunity, promotional information and marketing, and reference or influence by others were the factors that students considered when deciding on a PHEI. Chapman's model also emphasises the value of the graduate, which is seen in the ranking of the university (Chapman, 1981). The value of the SES model is relevant to this study, as it analyses social and economic factors and college characteristics that influence students' choice of university, such as financial costs (expenses) and academic programmes.

Spearman et al. (2016) highlight that universities in the Middle East/United Arab Emirates (UAE) place a significant emphasis on recruitment, which is evidenced by large investments to promote academic programmes and university culture. The UAE, similar to South Africa, has seen an increase in the number of universities, and, as a result, students have a range of options to choose from. The study conducted by the aforementioned authors surveyed 541 Dubai University students and found that reputation (good and bad), word of mouth, and the university's presence on social media platforms like Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook were critical deciding factors for students (Spearman et al., 2016). This study is relevant since it proves the importance of university reputation in the student's choice of institution.

3.4.1 Research model by Erdogmus and Ergun (2016)

The research model by Erdogmus and Ergun (2016) focuses on performance-related factors (i.e., teaching staff, qualification variety, graduate career prospects, student compatibility, the general environment, physical environment and education) since these factors can be controlled by the firm (i.e., the university). The purpose of the model is to explain the influence of university performance (i.e., teaching staff, qualification variety, graduate career prospects, student compatibility, the general environment, the physical environment and education) on the attitude and then brand loyalty of students. The model proposes attitude as a mediating variable between university performance and brand loyalty based on Ajzen and Fishbein (1977), who indicate that attitude precedes loyalty, as explained by the theory of reasoned action. Figure 1 illustrates the research model of Erdogmus and Ergun (2016).

3.5 Conceptual model and hypothesis testing

The following section provides an in-depth discussion of how the various hypotheses were developed by critically evaluating these relationships in prior studies. In addition, these variables have been guided by the models and theories described above.

3.5.1 Reputation and academic programmes and attitude towards the university

The reputation of an institution, as dictated by word of mouth, reviews and rankings, plays a critical role when selecting a university for undergraduate and post-graduate studies (Stephenson et al., 2016). The academic spread an institution offers is equally critical as a variety of programme offerings will attract a larger number of students (Munisamy et al., 2013). A higher education institution must uphold its reputation as well as the quality of qualifications offered to ensure that students remain loyal and that the institution remains competitive in the ever-changing higher educational landscape (Munisamy et al., 2013; Chandra et al., 2018). Rudhumbu et al. (2017) found that the academic programmes offered, the image and reputation of the institution, and the quality of educational facilities all influence students' choice of university in Botswana. Saif et al. (2016) state that students place a significant value on the reputation of a higher education institution and that it is the most influential factor when choosing a higher education institution. This sentiment is echoed by Simiyu et al. (2019), who recognise that the reputation of an academic institution is pivotal for a university in attracting potential students. A study conducted by Matherly (2011), as cited by Simiyu et al. (2019), found a significant and positive relationship between reputation and students' attitudes towards enrolling in a post-graduate qualification at a university. Therefore, the following hypothesis is presented:

H1: There is a positive relationship between reputation and academic programmes, and students' attitude towards their university.

3.5.2 Quality and competencies of academic staff and attitude towards the university

The lecturers, support staff and quality of higher education at universities are key components in providing a satisfactory and uncomplicated learning environment (Rapanta et al., 2020). The study undertaken by Wiese et al. (2009) found that the top three choice factors of students were the quality of teaching, prospective job opportunities, and campus security and safety. Setiawan et al. (2020) highlight that the quality of the academic staff at a university is one of the keys deciding factors that potential students look for. The onus is on the university to ensure the quality and competencies of academics, as this will determine the extent of student satisfaction and, ultimately, loyalty (Sabbah Khan & Yildiz, 2020). This is corroborated by Erdogmus and Ergun (2016), who state that teaching staff has a positive effect on students' attitudes towards the university. Consequently, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H2: There is a positive relationship between the quality and competencies of academic staff and students' attitudes towards their university.

3.5.3 Expenses and grants and attitude towards the university

With annual increases in the cost of tertiary education, several students, particularly those in lower-income households, seek assistance through independent bursaries, private donors and the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS). Tertiary education costs are not only limited to tuition costs but include living expenses, textbooks and other academic-related costs (stationery, data/airtime) (Naidoo & McKay, 2018). Therefore, when a higher education institution is deemed too expensive or does not have grant facilities for students to leverage, it decreases the number of students that can afford to go to that institution, which, in turn, impacts university loyalty (Deye, 2022). This factor is especially relevant to the context of the study at hand, given that The University of the Witwatersrand is in a third-world country with lower economic capability and outlook. Conversely, for students from high-income households, the perspective is that the expenses associated with an institution directly correlate with the quality of education provided by the institution. Mngomezulu et al. (2017) argue that institutional scholarships are a strong predictor of student persistence, i.e., continued enrolment in the institution. But, for this behaviour to be realised, a positive attitude and a conducive home life are required, especially for poorer South African higher education students that are dependent upon institutional scholarships. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is presented:

H3: There is a positive relationship between expenses and grants and students' attitudes towards their university.

3.5.4 Facilities and Physical Environment and Attitude towards the University

A university with a pleasant look, well-maintained facilities and established infrastructure is considered more desirable to prospective students (Redondo et al., 2021). Facilities and the physical environment within which students interact for social, cultural, sporting, and academic forums is a key variable in influencing students' attitudes toward an institution which, in turn, can influence loyalty (Boyd, 2022). A study conducted by Erdogmus and Ergun (2016) suggests that as the physical environment of the university improves, it will result in students spending more time on campus. In addition, the study provides empirical evidence to suggest a significant and positive relationship between physical evidence and attitude towards the university. The following hypothesis is thus presented:

H4: There is a positive relationship between the facilities and physical environment, and students' attitude towards their university.

3.5.5 Career prospects and attitude towards the university

Prospective students would favour institutions that have graduates that are quickly absorbed by the labour market (Wildschut et al., 2019). When an institution has a higher rate of employment as a result of university rankings and its reputation, it is viewed favourably by students and tends to create an increased tendency towards loyalty (Bano & Vasantha, 2019). A quantitative study undertaken in South Africa reveals that 406 first-year students placed a moderate level of importance on employment opportunities (van Zyl et al., 2018). However, a similar study undertaken by Gaspar and Soares (2021:30) in Angola found that "intellectual and personal development desire, acquisition of professional skills and opportunity to prosper in a professional level and find a good job" were the top three factors influencing student choice in HEI. Erdogmus and Ergun (2016) highlight that graduate prospects also impact students' attitudes towards their department/faculty. Furthermore, high graduate career prospects cultivated a sense of community among students. The study, therefore, proposes the following hypothesis:

H5: There is a positive relationship between career prospects and attitude towards their university.

3.5.6 Sports and extra-curricular activities and attitude towards the university

Universities are encouraged to offer a wide range of sports and extra-curricular activities for students to engage in as a means of enticing more students and ensuring enhanced student satisfaction and loyalty (Setiawan et al., 2020). Participation in physical activity is important for an individual's health (Zubiaur et al., 2021). However, once students enter university, their lifestyle changes, and their physical activity reduces. Winstone et al. (2020) highlight the positives of students engaging in sporting activities, like increased fitness levels and strength, improved well-being, stress reduction and decreased alcohol consumption. While for many, sport is a minor factor in university choice. However, Bolotin et al. (2017) acknowledge that the presence of a sports complex is important to students, especially those who seek to improve their physical and mental health. This is supported by Lin et al. (2017), who emphasise that sport influences university revenue, reputation and the number of student applications. Research by Dhir et al. (2021) postulates that behaviour is the outcome of attitude. Therefore, before applications are received, students would have a positive attitude towards the university. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is presented:

H6: There is a positive relationship between sports and students' attitudes towards their university.

3.5.7 Attitude towards the university and university loyalty

Student loyalty in a university context refers to students' willingness to enrol in further programmes, recommend and spread positive word-of-mouth and adopt supporting attitudes (Kaushal & Ali, 2020). To a large extent, the degree of loyalty is dependent on the connection that is established between the student and the university, which manifests itself through the student's attitude and subsequent behaviours (Snijders et al., 2020). While attitude towards a brand or university is regarded as one's assessment or evaluation of the institution (Yodpram & Intalar, 2020), Erdogmus and Ergun (2016) and Snijders et al. (2020) postulate that attitude towards the university has a significant positive contribution to university loyalty. The following hypothesis is thus presented:

H7: There is a positive relationship between students' attitudes towards the university and university loyalty

4. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY

This article reports on a descriptive study which comprises the development of a conceptual model for investigation. This study is underpinned by a positivism research philosophy and a deductive research approach using a quantitative research methodology. Associated with the deductive research approach and commonly used in business research (Saunders et al., 2019), a survey method was incorporated through which a self-administered questionnaire was deployed since it could be administered quickly and simply (Dalati & Marx Gomez, 2018).

When investigating the institutional factors that influence post-graduate students' attitudes towards their university and the subsequent impact of attitude on university loyalty, a cross-sectional time horizon was used to allow for the various individuals' data to be collected at the same time without influencing responses. Thus, the sampling design outlines how data was collected, how measurement items and scale instruments were used, the use of the instrument, and data analysis (Du Plooy-Cilliers et al., 2021).

4.1 Sample design

Convenience sampling, as a non-probability method, was used to target post-graduate students at the University of the Witwatersrand. The target population for this study was post-graduate students returning to or exiting the University of the Witwatersrand, who are 18 years and older, and who are South African nationals. In total, 150 post-graduate students made up the sample size. Using a-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models, Soper (2022) recommended a minimum sample size of 177, given an anticipated effect of 0.3, a desired statistical power of 0.8, and taking into account 8 latent variables and 38 observed variables with a 5 percent probability level. Therefore, the sample size of 150 obtained is not far from the recommended sample size. Obtaining a larger sample size was deemed difficult, given that data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the data collected has been rich enough to empirically prove the strength of various relationships.

4.2 Ethical consideration

The self-administered questionnaires were designed and administered with consideration and respect to avoid confusion, maladministration, or offence to respondents. Participation in the study was voluntary, with no benefits being gained by the participants. Participants remained anonymous and were allowed to withdraw at any time. All data and personal information collected were stored on a password-protected computer. Prior to data being gathered, ethical clearance was obtained from the School of Business Sciences' Ethics Committee at the University of the Witwatersrand (Protocol Number: CBUSE1828).

4.3 Measurement instrument

Standardised questionnaires were used to collect information about participants. Questionnaires were preferred as they provided the researchers with control over the phrasing of questions. The questionnaire links were administered electronically via the researchers' emails to participants at the University of the Witwatersrand. The researchers used Google Forms to capture the data from respondents. Although the questionnaire link was sent to all full-time and part-time students at the University of the Witwatersrand, the study is only applicable to the 16 624 registered post-graduate students. The data gathered from 150 completed questionnaires was then analysed. The electronic administering of the questionnaire was guided by COVID-19 health restrictions, which limited face-to-face contact and is partially responsible for the low response rate (under 1%).

A predictor variable is a variable that can be controlled or manipulated by the researcher to directly impact a dependent variable (Cramer & Howitt, 2004). This study analysed the relationship between six independent/predictor variables, namely 1) reputation and academic programmes, 2) quality and competencies of academic staff, 3) expenses and grants, 4) facilities and physical environment, 5) career prospects, and 6) sport, on students' attitude towards the university, and by extension, university loyalty, through a five-point Likert-scale, which ranged from (1) - strongly disagree to (5) - strongly agree. The scale items were adjusted from previous literature to fit the current study and are shown in Appendix 1. The structure of the questionnaire is as follows:

• Section A: General Information

• Section B: Reputation and Academic Programmes

• Section C: Quality and Competences of Academic Staff

• Section D: Expenses and Grants

• Section E: Facilities and Physical Environment

• Section F: Career Prospects

• Section G: Sport

• Section H: Attitude towards the University

• Section I: University Loyalty

5. DATA ANALYSIS

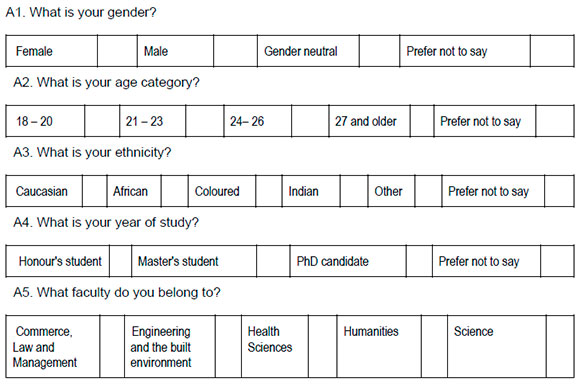

The demographic profile of respondents, variable statistics of constructs, and measurement instruments will be discussed and analysed in this section. The demographic profile of the 150 respondents observes and describes the gender, age, ethnicity, year of study and faculty of each post-graduate respondent. The descriptive statistics results are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1 illustrates that 60 percent of the respondents were female while 34 percent were male, and a collective 6 percent either identified as gender neutral or preferred not to specify their gender. In total, 40.7 percent of respondents were 27 years and older, which is expected with post-graduate students, followed by the age group 18 - 20 years old making up 4 percent, 21-23 years old making up 28 percent, and the age group 24-26 years old making up 24.7 percent of the respondents. While postgraduates are typically above the age of 20, there are instances where students exit secondary education between the ages of 15 to 17. Hence there are students that enter postgraduate education before the age of 20. Most of the respondents are of African ethnicity (46.7%), followed by Caucasian (32.7%), Coloured (9.3%) and Indian (8.7%). In total, 2.7 percent of the respondents preferred not to state their ethnic origin. Master's students made up 38.7 percent of respondents, with 38 percent being registered Honours students, 19.3 percent being PhD candidates, and the remaining 4 percent preferring not to disclose their year of study. Most respondents in this study are Commerce, Law and Management students (41.3%). This is followed by Health Science students (21.3%), Humanities students (15.3%), Engineering and the Built Environment students (12%), and Science students (10%).

This section illustrates the reliability and validity analyses of the eight constructs in this study.

5.1 Factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were performed to confirm the proposed structure of factors, Reputation and academic programmes, Quality and competencies of academic staff, Expenses and grants, Facilities and physical environment, Career prospects, Sport, Attitude towards the university, and University Loyalty. The results of these analyses are shown in Table 2.

According to Hair et al. (2014), the following guidelines indicate appropriate model fit for CFA analyses, a CMIN/df ratio less than 5, a CFI value greater than 0.92, an SRMR value of 0.08 or less, and an RMSEA value of 0.07 or less. A combination of three model fit indices reflecting values within these guidelines is deemed sufficient to indicate appropriate model fit. Reviewing the model fit indices, it can be seen that the factors indicate appropriate model fit. In addition to an appropriate mode fit, significant parameters are necessary to indicate construct validity. All factors included in this study demonstrate construct validity. In addition to construct validity, convergent and discriminant validity of the scales is required.

In order to assess convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) values were analysed (Steinkühler, 2010; Larwin & Harvey, 2012). The AVE is defined as the total value of variance in the observed variables that are represented by the latent construct (Malhotra et al., 2017). An AVE value of 0.4 can be accepted, provided the CR is higher than 0.6 (all CR values in this study are greater than 0.7) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Lam, 2012). The lowest value in this study is for the reputation and academic programmes construct, which equates to 0.41, and the highest value is for the sports construct, which is equal to 0.83. This range of values is deemed acceptable.

Discriminant validity is a type of construct validity that evaluates the extent to which a measure does not correlate with other constructs, which it is supposed to be distinct (Malhotra et al., 2017). To assess discriminant validity, the positive square root of AVE is compared to the inter-construct correlations and should be greater than the highest correlation with any of the other constructs. As seen in Table 3, discriminant validity is established for all constructs except reputation and academic programmes, which had one higher correlation. However, the positive square root AVE was 0.002 less than the highest correlation, and therefore, it was retained within the study.

A variety of methods are used to calculate internal reliability, but Cronbach's alpha is most frequently used among business researchers (Saunders et al., 2019). An acceptable Cronbach's alpha value should be equal to or exceed 0.7 (Bonett & Wright, 2014). A Cronbach's alpha value of 0.6 is permissible but questionable. Any value below 0.5 is not acceptable and is therefore unreliable (Trizano-Hermosilla & Alvarado, 2016). Table 4 indicates that all Cronbach alpha values are greater than 0.7, confirming internal consistency or reliability. An additional method used to determine internal reliability is composite reliability (CR). CR is defined as the total amount of true score variation in relation to the total score variance (Malhotra et al., 2017). As can be seen in Table 4, all values are in excess of the recommended cut-off of 0.7, proving that the scales are reliable.

5.2 Hypothesis testing through SEM

Mediation effects are studied in order to assess the processes that trigger the relationship between the dependent and independent constructs (MacKinnon et al., 2000; Pallant, 2013). In order to demonstrate mediation, four separate models are required. For a mediation model, it is required to demonstrate whether adding the mediating variable results in the relationship between the independent constructs and the dependent construct becoming insignificant. Thus, the following relationships between a) the independent constructs and mediating construct need to be significant, b) the mediating construct and dependent construct need to be significant, and c) the independent constructs and the dependent construct needs to be significant (Figure 2). The final model includes the independent, mediating, and dependent constructs, and to demonstrate full mediation, the relationship between the independent constructs and dependent constructs should now be insignificant.

The first set of relationships tested were the relationships between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, expenses and grants, facilities and physical environment, career prospects, and sport, with mediating construct, attitude towards the university. When tested, the pathways between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff and career prospects, with attitude towards the university significant (B = 0.491, p < 0.01, B = 0.407, p < 0.01 and B = 0.285, p < 0.01, respectively). However, the pathways between expenses and grants, facilities and physical environment and sports with attitude towards the university were insignificant (p = 0.829, p = 0.884 and p = 0.29, respectively). This indicated that only reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, and career prospects were found to be statistically significant predictors of attitude towards the university. A significant covariance was found between reputation and academic programmes and the quality and competencies of academic staff (MI = 58.938) and was included in the model.

The results for the model containing the significant predictors indicated an adequate model fit, as seen in Table 6.

The next set of relationships tested were the relationships between attitudes towards the university, with a dependent construct, university loyalty. When tested, the pathway between attitude towards the university, with university loyalty was found to be significant (B = 0.876, p < 0.01). This indicated that attitude towards the university is a significant predictor of university loyalty.

The results for the model containing the significant predictors indicated a good model fit as seen in Table 8.

Next, the relationships between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, expenses and grants, facilities and physical environment, career prospects, and sport, with dependent construct, university loyalty, are tested. When tested, the pathways between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff and career prospects, with university loyalty were found to be significant (B = 0.463, p = 0.002, B = 0.364, p < 0.001 and B = 0.203, p = 0.002, respectively). However, the pathways between expenses and grants, facilities and physical environment and sports with university loyalty were insignificant (p = 0.218, p = 0.624 and p = 0.128, respectively).

This indicated that only reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, and career prospects were found to be statistically significant predictors of university loyalty. Therefore, based on these results, the final mediation model that was tested is illustrated in Figure 3. A significant covariance was found between reputation and academic programmes and quality and competencies of academic staff (MI = 58.809) and was included in the model. The results for the model containing the significant predictors indicated a good model fit, as seen in Table 10.

When the full mediation model was tested, the pathways between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, and career prospects with university loyalty were found to be statistically insignificant (p = 0.649, p = 0.984, and p = 0.655, respectively). The pathways between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, and career prospects with attitude towards the university were found to be statistically significant (p = 0.059, p = 0.013, and p < 0.001, respectively). The pathway between attitude towards the university and university loyalty was found to still be significant (p < 0.001). These results demonstrate that attitude towards the university fully mediates the relationship between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, and career prospects with university loyalty.

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results from this study prove the existence of a significant relationship between reputation and academic programmes, the quality and competencies of academic staff, career prospects, and attitude towards the university. Furthermore, there is empirical support for the relationship between attitude towards the university and university loyalty. In addition, the results demonstrate that attitude towards the university fully mediates the relationship between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff, and career prospects with university loyalty. The relationship between the quality and competencies of academic staff and student attitudes towards the university is supported by Erdogmus and Ergun (2016). Moreover, the findings between attitude towards the university and university loyalty are also confirmed by Erdogmus and Ergun (2016).

The relationship between career prospects and reputation and academic programmes and students' attitudes towards their university are supported by Bano and Vasantha (2019), who found significant relationships between good job prospects and the reputation of the institution with university selection.

The insignificant influence of facilities and physical environment on students' attitudes towards their university could be attributed to the COVID-19 restrictions that limited students' physical attendance and enjoyment and appreciation of the university's campus. Therefore, this finding could be circumstantial.

6. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

The findings of this study can benefit university management. Based on the findings, career prospects, the quality and competencies of academic staff, and the university's reputation and academic programmes significantly influence students' attitudes towards the university.

By concentrating on the university's reputation and academic programmes, the quality and competencies of academic staff and providing qualifications that lead to good job prospects and attract the interest of recruiters, university managers can ensure positive student attitudes towards the university and, by extension, university loyalty. This would entail university management adopting relevant strategies and implementing the necessary policies to ensure a more rigorous evaluation of curricula and producing programmes that are cutting-edge and provide a stepping-stone for students to succeed in the 4th Industrial Revolution (IR). In addition, management needs to ensure that the most qualified staff are hired and their skills further enhanced by implementing suitable staff development initiatives where research and teaching skills are enriched. Moreover, many post-graduate students enrol as it leads to better pay and more rewarding corporate jobs. Universities that maintain high levels of industry engagement and can guarantee student internships and vacation work are often perceived more favourably. Therefore, universities that can focus on this will be closer to retaining some of their highest-performing students, which will provide considerable financial benefits to the institution.

Whilst sport was not found to significantly influence the attitude of post-graduate students, it is suggested that the institution continue to invest in various sporting codes as it provides an opportunity for students to improve their health and well-being and establish friendships with other students. In addition, sport provides balance to a student's life, assisting in the achievement of academic and career goals.

Based on the significant relationship between student attitude towards the university and university loyalty, management is encouraged to improve student attitude as it leads to university loyalty. This can be done in various ways, including providing a customer-centric service that focuses on students' overall university experience.

7. LIMITATIONS

The current study has some limitations. The research was conducted on a sample of 150 postgraduate students at the University of the Witwatersrand. A larger sample size, perhaps in excess of three hundred, would provide more dependable results for university management and other decision-makers. Furthermore, the study was limited to the University of the Witwatersrand. Other traditional universities in South Africa were excluded from the study due to budgetary and time constraints. The inclusion of different institutions would make the results more generalisable to all universities in South Africa. The study also did not check the common bias method. This implies that any partiality caused by measurement instruments is unknown. An online survey was the only method adopted for collecting data. This limited the researchers from performing adequate quality control in the answering of questionnaires.

8. CONCLUSION

From the results of this study, it is evident that reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff and career prospects have a positive and significant relationship with attitude towards the university. However, facilities and physical environment, expenses and grants, and sports were found to have an insignificant relationship with attitude. However, when testing mediation, it was found that attitude towards the university fully mediates the relationship between reputation and academic programmes, quality and competencies of academic staff and career prospects, and university loyalty. Perhaps the relationship between facilities and the physical environment of the institution and attitude has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, during which lockdown regulations subjected many students to off-campus and online teaching and learning, making this factor insignificant. It is also clear that sport has an insignificant relationship with attitude towards the university. This indicates that post-graduate students are influenced by the academics of an institution and not its sporting activities and prowess. In addition, the attitude towards the university was also found to influence university loyalty in a positive and significant way. This implies that the University of the Witwatersrand can build postgraduate student loyalty by ensuring students have a positive attitude towards the institution.

REFERENCES

Abreu Pederzini, G. 2016. What is strategy in universities during turbulent times? Journal of the Southwest Doctoral Training Centre, 1(2):14-20. [ Links ]

Agrey, L. & Lampadan, N. 2014. Determinant factors contributing to student choice in selecting a university. Journal of Education and Human Development, 3(2):391-404. [https://doi.org/10.15640/jehd]. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M. 1977. Attitude-behavior relations: a theoretical analysis and review of empirical research, Psychological Bulletin, 84(5):888-918. [https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888]. [ Links ]

Ali, M. & Ahmed, M. 2018. Determinants of students' loyalty to university: aservice-based approach. SSRN Electronic Journal. 1-23. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3261753]. [ Links ]

Ali, Z. S. & Hu, Y. 2022. Online information and communication through wechat and Chinese students' decisions for studying in New Zealand, Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 12(4):1-22. [https://doi.org/10.30935/ojcmt/12468]. [ Links ]

Austin, A.J. & Pervaiz, S. 2017. The relation between "student loyalty" and "student satisfaction": a case of college/intermediate students at Forman Christian College. European Scientific Journal, 13(3):100-117. [ Links ]

Bano, Y. & Vasantha, S. 2019. Influence of university reputation on employability. International Journal of Science & Technology Research, 8(1):2061-2064. [ Links ]

Bolotin, A. E. Piskun, O. E. & Pogodin, S. N. 2017. Special features of sports management for university students with regard to their value-motivational orientation. Theory and Practice of Physical Culture, 3:51-53. [ Links ]

Bonett, D. & Wright, T. 2014. Cronbach's alpha reliability: interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1):3-15. [https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1960]. [ Links ]

Boyd, F. 2022. Between the library and lectures: how can nature be integrated into university infrastructure to improve students' mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 13:1-14. [https://doi.org/doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.865422]. [ Links ]

Callender, C. & Melis, G. 2022. The Privilege of choice: how prospective college students' financial concerns influence their choice of higher education institution and subject of study in England. The Journal of Higher Education, 93:477-501. [https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2021.1996169]. [ Links ]

Centre for Global Higher Education. 2022. World higher education in a more unstable environment. [Internet: https://www.researchcghe.org/news/2018-10-31-world-higher-education-in-a-more-unstable-environment; downloaded on 8 March 2022]. [ Links ]

Chandra, T. Ng, M.M. Chandra, S. & Priyono, i. 2018. The effect of service quality on student satisfaction and student loyalty: an empirical study. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 9(3):109-131. [ Links ]

Chapman, D. 1981. A Model of Student College Choice. The Journal of Higher Education, 52(5):490-505. [https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1981.11778120]. [ Links ]

Cramer, D. & Howitt, D. 2004. The sage dictionary of statistics: a practical resource for students in social sciences. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

Cubillo, J.M. Sanchez, J. & Cerviho, J. 2006. International students' decision-making process. International Journal of Educational Management, 20(2):101-115. [https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540610646091]. [ Links ]

Dalati, S. & Marx Gómez, J. 2018. Surveys and questionnaires. In Marx Gómez, J., Mouselli, S. (eds) modernizing the academic teaching and research environment. 1st ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 175186. [ Links ]

Deye, S. 2022. Today's college student and the rising costs of higher education. [Internet: https://www.ncsl.org/research/education/today-s-college-student-and-the-rising-costs-of-higher-education.aspx; downloaded on 25 October 2022]. [ Links ]

DHET. 2020. Strategic Plan 2020 - 2025. [Internet: http://www.dhet.gov.za/SiteAssets/DHET%20Strategic%20Plan%202020.pdf; downloaded on 17 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Dhir, A. Sadiq, M. Talwar, S. Sakashita, M. & Kaur, P. 2021. Why do retail consumers buy green apparel? A knowledge-attitude-behaviour-context perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59:102398. [https://doi.org/10.1016/Uretconser.2020.102398]. [ Links ]

Doherty. F. 2017. Seven strategies universities should embrace to attract postgraduate students. [Internet: https://groupgti.com/insights/7-strategies-universities-should-embrace-attract-postgraduate-students; downloaded on 25 October 2022]. [ Links ]

Draisey, T. 2016. Factors Influencing College Choice: a study of enrollment decisions at a regional comprehensive university. Major Themes in Economics, 18(1):1-18. [ Links ]

Du Plooy-Cilliers, F. Davis, C. & Bezuidenhout, R. 2021. Research matters. 2nd ed. Cape Town: Juta & co LTD. [ Links ]

Erdogmus., I. & Ergun. 2016. Understanding university brand loyalty: the mediating role of attitudes towards the department and university. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 229:141-150. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.123]. [ Links ]

Fajcíková, A. & Urbancová, H. 2019. Factors influencing students' motivation to seek higher education-a case study at a State University in the Czech Republic. Sustainability, 11(17):4699. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su11174699]. [ Links ]

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1):39-50. [https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104]. [ Links ]

Garcia, S. & Sosa-Fey, J. 2020. Knowledge Management: what are the challenges for achieving organisational success? International Journal of Business & Public Administration, 17(2): 15-28. [ Links ]

Garwe, E. C. 2014. Investigating student preference for Private Higher Education. [Internet: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272511061_Investigating_students'_preference_for_Private_Higher_Education; downloaded on 05 May 2022]. [ Links ]

Gaspar, A.M.d.C.e.S. & Soares, J.M.A.C. 2021. Factors influencing the choice of higher education institutions in Angola. International Journal of Educational Administration and Policy Studies, 13(1):23-39. [https://doi.org/10.5897/ijeaps2020.0680]. [ Links ]

Groener, Z. 2019. Access and barriers to post-school education and success for disadvantaged black adults in South Africa: rethinking equity and social justice. Journal of Vocational, Adult and Continuing Education and Training, 2(1):54-73. [https://doi.org/10.14426/jovacet.v2i1.32]. [ Links ]

Govender, K.K. & Nel, E. 2021. Ranking of universities in the United Arab Emirates: exploring a web-based technique. South African Journal of Higher Education, 35(4):58-77. [https://doi.org/10.20853/35-4-4104]. [ Links ]

Hair, J.F. Jr. Sarstedt, M. Hopkins, L. & Kuppelwieser, V. G. 2014. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2):106-121. [https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128]. [ Links ]

Imenda, S.N. Kongolo, M. & Grewal, A.S. 2004. Factors underlying technikon and university enrolment trends in South Africa. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 32(2):195-215. [https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143204041884]. [ Links ]

Jafari, P. & Aliesmaili, A. 2013. Factors influencing the selection of a university by high school students. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 3(1):696-703. [ Links ]

James-MacEachern, M. & Yun, D. 2017. Exploring factors influencing international students' decision to choose a higher education institution: a comparison between Chinese and other students. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(3):343-363. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-11-2015-0158]. [ Links ]

Kaushal, V. & d Ali, N. 2020. University reputation, brand attachment and brand personality as antecedents of student loyalty: a study in higher education context. Corporate Reputation Review, 23(4):254-266. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-019-00084-y]. [ Links ]

Kumar, V. & Raman, R. 2020. Social Media by Indian Universities-does it convince or confuse international students in university choice? International Journal of Higher Education, 9(5):167-180. [https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n5p167]. [ Links ]

Kusumawati, A. 2019. Impact of digital marketing on student decision-making process of higher education institution: a case of Indonesia. Journal of e-Learning and Higher Education, 2019:1-11. [https://doi.org/10.5171/2019.267057]. [ Links ]

Lam, L.W. 2012. Impact of competitiveness on salespeople's commitment and performance. Journal of Business Research, 65(9):1328-1334. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.026]. [ Links ]

Larwin, K. & Harvey, M. 2012. A demonstration of a systematic item-reduction approach using structural equation modeling. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 17(1):8. [ Links ]

Le, T.D. Dobele, A.R. & Robinson, L, J. 2019. Information sought by prospective students from social media electronic word-of-mouth during the university choice process, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 41:18-34. [https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1538595]. [ Links ]

Lin, J. Paulson, L. Romsa, B. Walker, H. J. & Romsa, K. 2017. Analysis of factors influencing the college choice decisions of ncaa division ii elite track and field athletes. International Journal of Sport and Physical Education, 3(2):22-31. [https://doi.org./10.20431/2454-6380.0302005]. [ Links ]

MacKinnon, D.P. Krull, J.L. & Lockwood, C.M. 2000. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1:173-181. [https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026595011371]. [ Links ]

Mail & Guardian. 2015. The students. [Internet: https://mg.co.za/article/2015-05-14-uct-and-transformation-the-students/; downloaded on 01 April 2022]. [ Links ]

Malhotra, N. Nunan, D. & Birks, D. 2017. Marketing research: an applied approach. 5th ed. Harlow, England: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

MANCOSA. 2019. The Difference Between Undergraduate & Postgraduate. [Internet: https://www.mancosa.co.za/blog/the-difference-between-undergraduate-postgraduate/; downloaded on 24 October 2022]. [ Links ]

Matherly, L.L. 2011. A causal model predicting student intention to enrol moderated by university image: using strategic management to create competitive advantage in higher education. International Journal of Management in Education, 6(1-2):38-55. [https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMIE.2012.044000]. [ Links ]

Mlachila, M.M. & Moeletsi, T. 2019. Struggling to make the grade: a review of the causes and consequences of the weak outcomes of South Africa's education system. (47):1-61. [https://doi.org/10.5089/9781498301374.001]. [ Links ]

Mngomezulu, S. Dhunpath, R. & Munro, N. 2017. Does financial assistance undermine academic success? Experiences of "at risk" students in a South African university. Journal of Education, 68, 131-148. [ Links ]

Moorthy, K. Johanthan, S. Hung, C.C. Han, K.C. Zheng, N.Z. Cheng, W.Y. & Yuan, W.H. 2019. Factors affecting students' choice of higher education institution: a Malaysian perspective. World Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 1(2):59-74. [https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.119.2019.12.59.74]. [ Links ]

Mulyono, H. Hadian, A. Purba, N. & Pramono, R. 2020. Effect of service quality toward student satisfaction and loyalty in higher education. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(10):929- 938. [https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no10.929]. [ Links ]

Munisamy, S. Jaafar, N. & Nagaraj, S. 2013. Does reputation matter? Case study of undergraduate choice at a premier university. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 3(23): 451-462. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0120-y]. [ Links ]

Musselin, C. 2018. New forms of competition in higher education. Socio-Economic Review, 16(3):657-683. [https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwy033]. [ Links ]

Naidoo, A. & McKay, T.J.M. 2018. Student funding and student success: a case study of a South African university. South African Journal of Higher Education, 32(5):158-172. [https://doi.org/10.20853/32-5-2565]. [ Links ]

Nordling, L. 2021. "Deep concerns" over South African university funding. Research Professional News. [Internet: https://www.researchprofessionalnews.com/rr-news-africa-south-2021-1-deep-concerns-over-south-african-university-funding/; downloaded on 20 February 2022]. [ Links ]

Pallant, J. 2011. SPSS survival manual: a step by step guide to data analysis using the SPSS program. 4th ed. Berkshire: Allen & Unwin. [ Links ]

Pinar, M. Girard, T. & Basfirinci, C. 2020. Examining the relationship between brand equity dimensions and university brand equity: an empirical study in Turkey. International Journal of Educational Management, 34(7):11191141. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-08-2019-0313]. [ Links ]

Rapanta, C. Botturi, L. Goodyear, P. Guàrdia, L. & Koole, M. 2020. Online university teaching during and after the covid-19 crisis: refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Science Education, 2:923-945. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y]. [ Links ]

Redondo R. Valor C. & Carrero I. 2021. Unravelling the relationship between well-being, sustainable consumption and nature relatedness: a study of university students. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17, 913-930. [https://doi.org/10.1007/S11482-021-09931-9]. [ Links ]

Rehman, M.A. Woyo, E. Akahome, J.E. & Sohail, M.D. 2020. The influence of course experience, satisfaction, and loyalty on students' word-of-mouth and re-enrolment intentions. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 32(2):1-19. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2020.1852469]. [ Links ]

Rudhumbu, N. Tirumalai, A. & Kumari. 2017. Factors that influence undergraduate students' choice of a university: a case of Botho University in Botswana. International Journal of Learning and Development, 7(2):27-37. [https://doi.org/10.5296/ijld.v7i2.10577]. [ Links ]

Sabbah Khan, N.U. & Yildiz, Y. 2020. Impact of intangible characteristics of universities on student satisfaction. Revista Amazonia Investiga, 9(26):105-116. [https://doi.org/10.34069/ai/2020.26.02.12]. [ Links ]

Saif, A.N.M. Nipa, N.J. & Siddique, M.A. 2016. Assessing the factors behind choosing universities for higher education: a case of Bangladesh. Global Journal of Management and Business Research: A Administration and Management, 6(11):44-52. [ Links ]

Saunders, M. Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. 2007. Research methods for business students. 4th ed. Harlow: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Soper, D.S. 2022. A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models [Software]. [Internet: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc; downloaded on: 31 October 2022]. [ Links ]

Setiawan, R. Aprillia, A. & Magdalena, N. 2020, Analysis of antecedent factors in academic achievement and student retention. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 15(1):37-47. [https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-09-2019-0043]. [ Links ]

Simiyu, G. Komen, D.J. & Bonuke, D.R. 2019. Social media, external prestige and students' attitude towards postgraduate enrollment: a conditional process analysis across levels of university reputation. SEISENSE Journal of Management, 2(5):1-19. [https://doi.org/10.33215/sjom.v2i5.186]. [ Links ]

Singh, D.K. 2017. An investigation into the factors that influence students' choice of a selected Private Higher Education Institution in South Africa. [Internet: https://ir.dut.ac.za/bitstream/10321/3280/1/SINGHDK2017.pdf; downloaded on 20 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Snijders, I. Wijnia, L. Rikers, R.M. & Loyens, S.M. 2020. Building bridges in higher education: student-faculty relationship quality, student engagement, and student loyalty. International Journal of Educational Research, 100:101538. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101538]. [ Links ]

Soutar, G.N. & Turner, J.P. 2002. Students' preferences for university: a conjoint analysis. International Journal of Educational Management, 16(1):40-45. [https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540210415523]. [ Links ]

Spearman, J. Ljepava, N. & Ghanayem, S. 2016. Factors influencing student enrolment and choice of university. Dubai, UAE: International Business Research Conference. (35th Conference of International Business Research; 30 - 31 May 2016). [ Links ]

Steinkuhler, D. 2010. Delayed project terminations in the venture capital context: an escalation of commitment perspective. 1st ed. Aachen: Josef Eul Verlag Gmbh. [ Links ]

Stephenson, A.L. Heckert, A. & Yerger, D.B. 2016. College choice and the university brand: exploring the consumer decision framework. Higher Education, 71(4):489-503. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9919-1]. [ Links ]

Sung, M. & Yang, S.U. 2008. Toward the model of university image: the influence of brand personality, external prestige, and reputation. Journal of Public Relations Research, 20(4):357-376. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10627260802153207]. [ Links ]

Tewari, D.D. & Ilesanmi, K.D. 2020. Teaching and learning interaction in South Africa's higher education: some weak links. Cogent Social Science, 6(1):1-16. [https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1740519]. [ Links ]

Times Higher Education. 2022. Learning in South Africa: the evolving education landscape. [Internet: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/hub/d2l-emea/p/learning-south-africa-evolving-education-landscape; downloaded on 13 April 2022]. [ Links ]

Toledo, D.L. & Martinez, L.T. 2020. How loyal can a graduate ever be? The influence of motivation and employment on student loyalty. Studies in Higher Education, 45(2):353-374. [https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1532987]. [ Links ]

Tjonneland, E.N. 2017. Crisis at South Africa's universities - what are the implications for future cooperation with Norway? [Internet: https://www.cmi.no/publications/6180-crisis-at-south-africas-universities-what-are-the; downloaded on 01 April 2022]. [ Links ]

Trizano-Hermosilla, I. & Alvarado, J. 2016. Best alternatives to cronbach's alpha reliability in realistic conditions: congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Frontiers in Psychology, 7:1-8. [https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00769]. [ Links ]

University of the Witwatersrand. 2022. Facts & Figures 2020/2021. [Internet: https://www.wits.ac.za/media/wits-university/about-wits/documents/WITS%20Facts%20%20Figures%202020-2021%20Revised%20Hi-Res.pdf; downloaded on 01 April 2022]. [ Links ]

van Zyl, S. Meyer, J. & Pelser, T. 2018. Factors Influencing the choice of universities of first year students at the north west university, Mafikeng Campus. Le Maurice, Mauritius International Business Conference. (12th conference of the International Business Conference; 23 - 26 Sep). [ Links ]

Veloutsou, C. Lewis, J.W. & Paton, R.A. 2004. University selection: information requirements and importance. International Journal of Educational Management, 18(3):160-171. [https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540410527158]. [ Links ]

Vianden, J. & Barlow, P.J. 2014. Showing the love: predictors of student loyalty to undergraduate institutions. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 51(1):16-29. [https://doi.org/10.1515/jsarp-2014-0002]. [ Links ]

Viljoen, D. 2018.Higher education: a vast and changing future. [Internet: https://www.fin24.com/Finweek/Featured/higher-education-a-vast-and-changing-future-landscape-20180228; downloaded on 14 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Walsh, S. & Cullinan, J. 2017. Factors Influencing Higher Education Institution Choice. Economic Insights on Higher Education Policy in Ireland, 81-108. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48553-94]. [ Links ]

Washington, G.Y. 2019. The learning management system matters in face-to-face higher education courses. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 48(2):255-275. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239519874037]. [ Links ]

Wiese, M. van Heerden, C.H. Jordaan, Y. & North, E. 2009. A marketing perspective on choice factors considered by South African first-year students in selecting a higher education institution. South African Business Review, 13(1):39 - 60. [ Links ]

Wildschut, A. Rogan, M. & Mncwango, B. 2019. Transformation, stratification and higher education: exploring the absorption into employment of public financial aid beneficiaries across the South African higher education system. Higher Education, 79:961-979. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00450-z]. [ Links ]

Williamson, S.N. & Paulsen-Becejac, L. 2018. The impact of peer learning within a group of international postgraduate students-a pilot study. Athens Journal of Education, 5(1): 7-27. [https://doi.org/10.30958/aje.5-1-1]. [ Links ]

Winstone, N. Balloo, K. Gravett, K. Jacobs, D. & Keen, H. 2020. Who stands to benefit? Wellbeing, belonging and challenges to equity in engagement in extra-curricular activities at university. Active Learning in Higher Education, 32(2):81-96. [https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787420908209]. [ Links ]

Winter, E. & Chapleo, C. 2015. An exploration of the effect of servicescape on student institution choice in UK universities. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41:187-200. [https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2015.1070400]. [ Links ]

Yodpram, S. & Intalar, N. 2020. Conceptualising eWOM, brand image, and brand attitude on consumer's willingness to pay in the low-cost airline industry in Thailand. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute Proceedings, 39(1):27. [https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019039027]. [ Links ]

Zubiaur, M. Zitouni, A. & Del Horno, S. 2021. Comparison of sports habits and attitudes in university students of physical and sports education of Mostaganem (Algeria) and physical activity and sport sciences of León (Spain). National Library for Medicine. [https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.593322]. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author

APPENDIX 1: QUESTIONNAIRE

SECTION A: GENERAL INFORMATION

This section aims to get a better understanding of your background. Please indicate your answer by placing an (X) in the appropriate box.

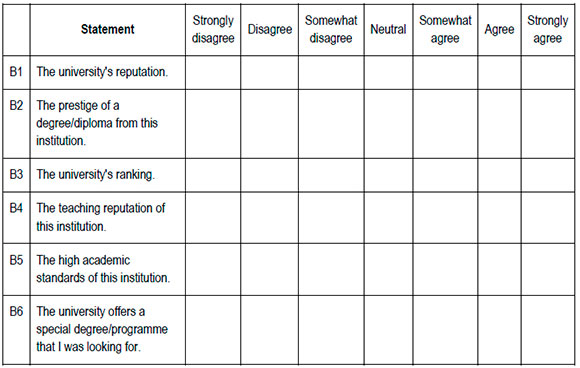

SECTION B: REPUTATION AND ACADEMIC PROGRAMMES (6)

The statements below are within the context of the University of the Witwatersrand. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement by placing a mark (x) in the most appropriate box. Adapted from: James-MacEachern & Yun (2017)

The University of the Witwatersrand is attractive because of:

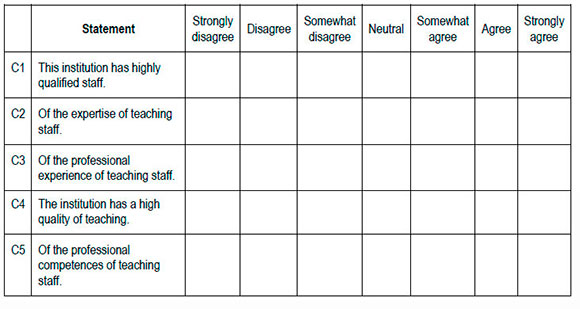

SECTION C: QUALITY AND COMPETENCES OF ACADEMIC STAFF (5)

The statements below are within the context of the University of the Witwatersrand. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement by placing a mark (x) in the most appropriate box. Adapted from: Imenda, Kongolo and Grewal (2004); Cubillo, Sanchez & Cervino 2006; Soutar & Turner (2002); Fajcikova & Urbancova (2019).

The University of the Witwatersrand is attractive because:

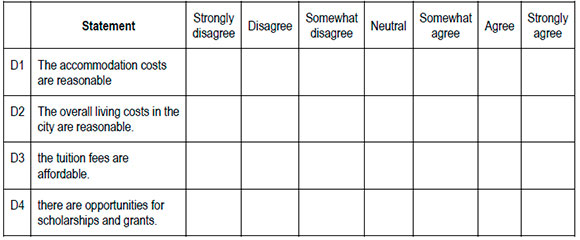

SECTION D: EXPENSES AND GRANTS (4)

The statements below are within the context of the University of the Witwatersrand. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement by placing a mark (x) in the most appropriate box. Adapted from: James-MacEachern & Yun (2017)

The University of the Witwatersrand is attractive because:

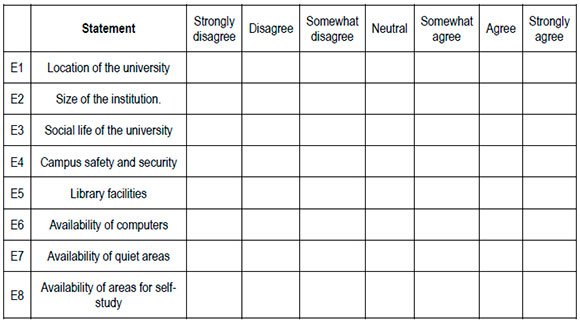

SECTION E: FACILITIES AND PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT (8)

The statements below are within the context of the University of the Witwatersrand. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement by placing a mark (x) in the most appropriate box. Adapted from: James-MacEachern & Yun (2017); Cubillo, Sanchez & Cervino (2006)

The University of the Witwatersrand is attractive because of the:

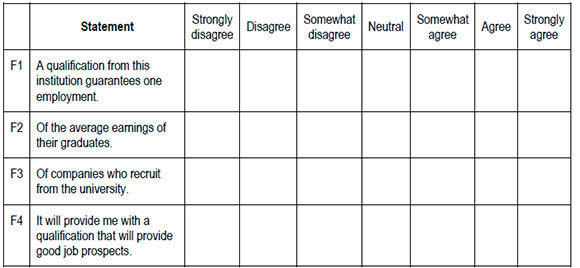

SECTION F: CAREER PROSPECTS (4)

The statements below are within the context of the University of the Witwatersrand. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement by placing a mark (x) in the most appropriate box. Adapted from: Veloutsou, Lewis & Paton (2004); Soutar & Turner (2002)

The University of the Witwatersrand is attractive because:

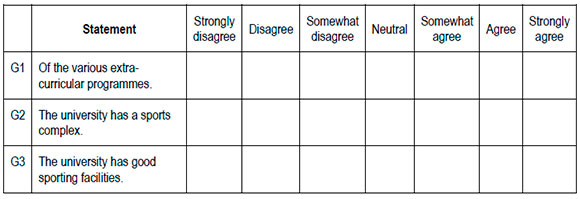

SECTION G: SPORT (3)

The statements below are within the context of the University of the Witwatersrand. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement by placing a mark (x) in the most appropriate box. Adapted from: Agrey & Lampadan (2014); Jafari & Aliesmaili (2013)

The University of the Witwatersrand is attractive because:

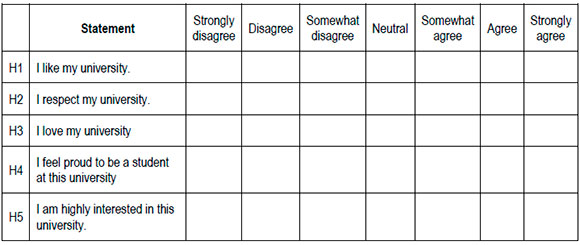

SECTION H: ATTITUDE TOWARDS THE UNIVERSITY (5)

The statements below are within the context of the University of the Witwatersrand. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement by placing a mark (x) in the most appropriate box. Adapted from: Erdogmus & Ergun (2016); Sung and Yang (2008)

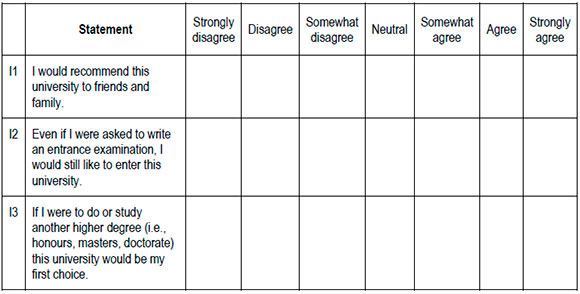

SECTION I: UNIVERSITY LOYALTY (3)

The statements below are within the context of the University of the Witwatersrand. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement by placing a mark (x) in the most appropriate box. Adapted from: Erdogmus & Ergun (2016)