Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of Contemporary Management

versión On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.20 no.1 Meyerton 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcm1038.204

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Brand identity-image fit in professional services in South Africa: Is brand co-creation a panacea?

Kuhle Mkanyiseli ZwakalaI, *; Pieter SteenkampII

IMarketing Department, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa. Email: Zwakalak@cput.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8948-5125

IIMarketing Department, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa. Email: SteenkampPi@cput.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9575-1039

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: Brand identity and image research in the services sectors are underdeveloped. This study examines the constructs through the lens of service-dominant factors. Their synchronisation is particularly crucial in services as brand identity clarification serves as a point of difference. This study examined brand identity-image (in)congruence in the South African banking sector. Furthermore, as conceptual ambiguities and overlaps in current brand management approaches hinder the development of the corpus, we consolidate the schools of thought within a coherent framework

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: An interpretivist exploratory qualitative research design was adopted. In-depth interviews were conducted with marketing executives who were instrumental in brand strategy formulation to extrapolate banks' brand identities. To infer brand image for comparative purposes, in-depth interviews were conducted with banks' clients in the law firm sector

FINDINGS: The study presents evidence of brand identity-image incongruence in South African banks. We submit a new framework that may be a panacea to fragmented bank brand identities

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: This study provides new insights into extant brand identity theories through reconfiguring overlapping brand management schools

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The study attempts to minimise the apparent brand management science-practice/industry gap specifically on brand identity and image constructs. We suggest an agile approach to how professional services can build coherent brands

JEL CLASSIFICATION: G21; M14; M31

Keywords: Banks; Brand co-creation; Brand identity; Brand image; Services.

1. INTRODUCTION

Brands are unique assets to firms. They offer both functional and emotional benefits to customers and promote strong customer-brand relationships (Sander et al., 2021). Thus, brands are widely considered valuable assets for firms (Boisvert & Ashill, 2022). Moreover, brands play a significant factor in consumers' product evaluation and purchase decisions because they enable consumers to differentiate and identify quality differences (Alvarado-Karste & Guzman, 2020; Woo & Kim, 2022). Brand differentiation is created through unique features such as brand elements (names, logos, slogans) (Keller & Swaminathan, 2020). These elements primarily contribute to building brand identity, brand knowledge and brand perceptions (Qiao & Griffin, 2022).

Even though there is no consensual account of how brands and branding should be conceptualised, Kamboj et al. (2018) distinguish between brands and branding insofar as the former reflects views that reside in consumers' minds while the latter is seen as a firm-based practice and a process. Brand identity and brand image schools emanate from this background (Zwakala & Steenkamp, 2021a). Iyer et al. (2021) concur that the brand management process primarily addresses the development of a brand's core identity. Furthermore, this process seeks to align external factors to internal operations to enhance short-and long-term brand objectives.

Ghodeswar (2008) and Kapferer (2012) posit that a fundamental element of brand building is developing and communicating what a brand stands for. Expressing a brand's identity may yield sustained competitive advantage. However, brand identity is multifaceted due to subjective and often divergent brand-building theories and approaches. Some academics and practitioners are guided by identity, which adopts brand orientation and internal stakeholder bias as the premise of brand building, whereas others are driven by image, which recognises market orientation and external stakeholder bias (Ries & Trout, 2001; Urde & Greyser, 2016). According to Kapferer (2012), brand image is derived from consumers decoding a brand's identity, extracting meaning and interpreting brand elements, and this yields brand awareness, perceptions and reputation (Liu et al., 2020).

Moreover, building a coherent brand identity is a topical subject in extant brand literature; this can be achieved when brand identity is congruent with its brand image (Black & Veloutsou 2017; Satini et al., 2018). Aligning the two domains (image and identity) is a strategic imperative, particularly in professional services sectors where brand experience may be the only means to demonstrate a brand's truth and identity (Schmeltz & Kjeldsen, 2018).

The current study explored brand identity-image fit between South Africa's dominant bank brands and their business clients in the law firm sector. Specifically, we focus on brand identity constituent dimensions that are ubiquitous in this school, namely visual identity; personality; culture and values; differentiation; positioning; self-image/self-concept; reflection; and relationship (Kapferer, 2012). The findings reveal that clients misconstrue certain brand identity dimensions such as personality, culture and values. Of interest is how banks' self-image/self-concept and reflection were found inapplicable from an identity viewpoint. This raises the question of whether brand co-creation is a panacea to attaining brand identity-image fit in services (Lu et al., 2022). Guzel et al. (2021) argue that customers' inputs are inherently embodied in services' customer value creation, as they (customers) co-create services. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: we review the extant literature on brand identity, brand image, and the concept of fit or congruence, whereafter, the research gap is identified. Services branding is then elucidated, followed by the adopted research methodology, findings, and theoretical and managerial implications.

1.1 Brand identity

Brand identity is a complex and multifaceted construct that has been studied by several scholars (Aaker, 1996; De Chernatony, 2007; Balmer, 2012; Coleman, De Chernatony & Christodoulides, 2011; Kapferer, 2012; Keller, 2013; Urde, 2016; Abratt & Mingione, 2017; Burmann et al., 2017; Beverland, 2018; Schmidt & Redler, 2018). Brand identity is formed by unique company characteristics, which form a central and integrative function within a firm's broader brand strategy. Through these distinctive features, firms transmit their identity and values through communication (Melewar et al., 2017). Brand identity is crafted by firms for differentiation and identification purposes in a manner that is consistent with their values and relevant to their stakeholders (Alvarado-Kartste & Guzman, 2020). Brand differentiation is a critical construct in distinguishing a brand's identity from those of competitors, as brand identity distinctiveness can become a driver of consumer-brand identity congruence (Confente & Kucharska, 2021). Furthermore, Hem and Supphellen (2022) posit that brand differentiation yields brand preference, loyalty and market value. Similarly, McManus et al. (2022) hold that maintaining a differentiated brand identity yields a consistent brand meaning, brand association and loyalty. Therefore, core values are central in brand identity construction and often stem from a brand's origin.

Chung and Byrom (2021) concur that brand identity formulation is multipronged, based on what they term three principal elements, namely strategic, sensory and organisational identity. Strategic identity is the initial phase of brand building to clarify a brand's vision, mission, values, and intent. Sensory identity incorporates visual elements (colour, logo, symbol) and auditory elements jingles/sounds/music that reinforce a brand (Keller & Swaminathan, 2020). Moreover, the authors postulate that organisational identity is developed through behaviour and social interaction among members of an organisation (Iglesias et al., 2020; Zwakala & Steenkamp, 2021a). Additionally, the link between brand identity and strategy is significant as it illustrates a firm's culture and values. Even though identity constituent dimensions such as ethos and values are abstract, they demonstrate a brand's distinctiveness through company visual cues (Melewar et al., 2017). Visual identity cues communicate specific aspects of a brand's identity system, and their primary purpose is to ensure the brand is identifiable (Buil et al., 2017). Visual identity dimensions should collectively arouse a positive reaction across all stakeholders in all brand touchpoints, meaning there should be cohesiveness between all these elements due to their reciprocal effect (Erjansola et al., 2021).

Additionally, a brand's history and heritage are central to brand identity construction and often stem from a brand's origin. Through brand symbols, product legacy, and consumption, ritual brand heritage can be operationalised. Therefore, depicting or operationalising brand heritage through visual elements can enhance the explication of the constructs (Keller & Swaminathan, 2022; Butcher & Pecot, 2022). Moreover, Rindell and Santos (2021) argue that trust, authenticity and affinity underpin brand heritage. Hence heritage is a critical dimension of brand identity formulation.

Relationships established through a brand's value propositions and delivery are critical to brand identity formulation (Sharma et al., 2022). In fact, long-term relationships characterise professional services. The relationship dimension is two-pronged, stemming from the firms and their customers. On the one hand, firms competing in highly competitive markets such as professional services markets must build identity-based customer relationships (Itani, 2021). On the other hand, customer-brand identification is a psychological state where consumers feel a sense of resonance and belonging to a brand, a sense of oneness they have with a brand characterised by intense loyalty (Keller & Swaminathan, 2020; Yoshida et al., 2021).

Brand-self connection is a cognitive and emotional relationship between the brand and the customer's self. Customers can seek association with a brand as it may symbolise a significant instrumental value to achieve personal goals like self-image, and reflection based on brand association (Li et al., 2021; Torres et al., 2021). Robbanee et al. (2022) suggest that the self-image or self-concept construct is multi-dimensional and is constituted by actual self (a person's real personality), ideal self (an idealised version of a person, whom they would like to be), and social self or reflection (how a person would like to be perceived by others in society based on brand association) (Kapferer, 2012; Saenger et al., 2020).

Moreover, brand personality is also a critical brand identity constituent construct, and its fundamental basis is endowing brands with human characteristics which may be consistent with those of customers (Aaker, 1997; Burmann et al., 2017; Tarabashkina et al., 2021). Consequently, identity-based brand building is two-pronged, based on (i) "the self is the hero"; or (ii) "the brand is the hero". In the former perspective, consumers develop self-brands or own identities to project themselves to others. The latter viewpoint suggests that consumers use extant brand identities to anthropomorphise brands in order to foster a fit between the self and the brand (Kara et al., 2020; Zwakala & Steenkamp, 2021a). Another foundational construct in the brand identity school is brand positioning, which is essentially designing a firm's offering in such a manner that it occupies a distinct place in the minds of consumers. The construct has little to do with the product's functional or tangible attributes, as the purpose is to build brands from within firms and/or solicit positive brand reputation (Ries & Trout, 2001; Lee et al., 2018:453). Services brands rely on brand positioning to communicate the value proposition and credibility (Lee et al., 2018; Endo et al., 2019). Therefore, brand positioning aims to formulate an integrated communication strategy that aligns consumer brand perceptions and image with the actual brand identity (Sihvonen, 2019).

1.2 Brand image

Brand image is derived from consumers decoding a brand's identity (Kapferer, 2012). Thus, a causal correlation exists between the two domains. Brand image is a process of synergistic decoding of brand elements and extracting brand meaning from consumers. Brand image formulation is constituted by consumers' subjective perceptions coupled with external social stimuli (Liu et al., 2020; Teng et al., 2021), meaning that brand image is constructed by consumers' cognitive and emotive evaluations of brands (Sultan & Wong, 2019; Amaro et al., 2021). Brand image is also formed by interpreting elements such as brand tradition, visual cues, servicescape and customers associated with that brand (Yun et al., 2020). So, central to the brand image school are clients' perspectives in understanding and developing brands. Therefore, the brand image should be conceptualised by understanding its core antecedents and consequences. For instance, important brand identity dimensions such as brand authenticity and brand promise are strong brand image inputs. On the other hand, brand awareness and, ultimately, brand reputations are consequences of brand image (Rodrigues et al., 2021; Islam & Hussain, 2022).

Huaman-Ramirez and Merunka (2021) postulate that brand image is conceptualised through two sub-dimensions, namely functional and sensory/visual images. The former refers to a brand's capacity for utilitarian performance. Therefore, service efficiency and effectiveness reflect a brand's functional image linked to rational perceptions that fulfil utilitarian considerations; whereas sensory image corresponds to features that engage the consumers' senses, and this can be gauged during or post-brand experience (Keller, 2013). In the context of professional services, service experience and servicescape are critical in building a positive brand image (Li et al., 2021). Even though consumers' perceptions of services brands may vary depending on the complexity and nature of a particular services sector, services brands share inherent characteristics such as perishability; hence attempts must be made to attain a strategic fit between a brand's identity and its image, as this directly influences service performance and experience (Momen et al., 2020). This stance is corroborated by Bakri et al. (2020), who state that crafting a desirable brand image is more crucial in services sectors compared to goods sectors, given the nature of services and their characteristics. Furthermore, in services sectors, brand image defines the service to clients, creates points of difference and serves as an assurance of quality. Alvarado-Kartste and Guzman (2020) and Chung and Byrom (2021) suggest that in order to create brand identity-image fit, services firms need to initially build a coherent brand identity internally, and consistently communicate it through different channels and brand touchpoints.

1.3 Theory of fit

The roots of alignment as a concept can be traced from strategic management theory, and it is widely applied in human resource management practices (Srivastava & Thomas, 2010). Fit illustrates the consistency between a firm's internal and external elements (L'Ecuyer & Raymond, 2017). Fit is also conceptualised as the overall perceived relatedness and compatibility between a firm and its audiences (Deng et al., 2022). To detect fit, it is important to evaluate schemas between internal and external audiences (Eklund & Helmefalk, 2022). Although congruence can be either purposeful or causal, the ultimate consequence is organisational coherence (Chorn, 1991; Quiros, 2009). The conceptual congruence framework forwarded by Zwakala and Steenkamp (2021a) is purposeful as it delineates modalities to attain synergistic brand identity and brand image in the services sectors. However, congruence is not a permanent phenomenon as it is determined by space, context and time (Eklund & Helmefalk, 2022). Hence, they argue that the framework can also serve as a diagnostic apparatus to scrutinise brand identity-image fit over time and in different contexts (also see Mingione, 2015).

In brand management contexts, the fit between internal brand elements such as visual identity and external construal determines brand identity coherence and consequently influences brand performance (Burmann et al., 2017). The importance of brand fit is also noted by Cullinan et al. (2021), who posit that brand managers should pay attention to the coherence between internal and external brand constituencies, and this may be achieved when brands deliver on their promises. Moreover, given firms' dependence on external stakeholders due to the inseparability effect, brand alignment has become a strategic imperative, particularly in the services sectors (Su & Kunkel, 2019; Pranjal & Sarkar, 2020).

1.4 Branding services

Comparatively, there is less research on branding in the services industry versus pure goods branding. This paucity can be attributed to the familiarity between brand names and goods compared to the lesser familiarity between brand names and services (Zwakala & Steenkamp, 2021b). The theoretical underpinning of the service-dominant logic suggests that a service is an action carried out by a firm to create stakeholder value, as opposed to simply viewing a service as a firm's output. This means that customer value creation is interactional and experiential, whereby services are a co-created process between a firm and its customers. The service value creation process is thus two-pronged, as value is co-created by both the firm and the customer (Kumar et al., 2017; Lipkin & Heinonen, 2022). The integration of people/actors, process, and servicescape conceptualises service value co-creation and experience. Due to the collaborative nature of service value creation, all role players should be fully aware of each other's intentions and capabilities (Dehling et al., 2022).

A study conducted by Kuuru and Narvanen (2022) on employee embodiment of the service environment suggests that due to joint encounters and interactivity during service provision, a human and emotional connection between the service provider and customer is imperative, even in digitised services. Randle and Zainuddin (2022) also found that emotional value is essential, particularly in human services, coupled with other value dimensions such as functional and social value. The human touch in professional services may yield a competitive advantage as consumers generally make their service brand choices based on criteria such as service uniqueness and attentiveness (Indounas & Arvaniti, 2015). Competent and well-qualified service employees give psychological assurance to customers and enhance the value proposition, particularly in services sectors such as medical, legal and financial services (Endo et al., 2019).

Customer orientation characterises financial services brands and is often demonstrated through employees' responsiveness, reliability and empathy in addressing clients' needs (Lozza et al., 2022). A pleasant bank brand service experience shapes long-term client-brand relationships, and the consequence may be client brand attachment (Keller & Swaminathan, 2020). Even though Levy (2022) posits that bank brands can achieve an emotional connection with clients through digital platforms, the 'here-and-now' service requirement effect remains a constraint on digital platforms coupled with the inability to predict clients' behaviour.

The financial services sector market in South Africa has been revolutionised in recent years due to the entrance of new competitors in the form of digital (virtual) bank brands - Discovery Bank, Bank Zero and TymeBank (Nel & Boshoff, 2021). The sector is well-developed and is regulated by the South African Reserve Bank (SARB). A global financial intelligence rating agency, The Banker, declared Standard Bank as the biggest bank in South Africa by Tier 1 capital in 2021, followed by First National Bank, ABSA, Nedbank and Investec, respectively, in the same category. These top 5 banks have withstood Covid-19 pandemic pressures as they remain stable and globally competitive (BusinessTech, 2021a). SARB's 2021 Prudential Authority Annual Report (as reported by BusinessTech, 2021b) states that collectively, ABSA, First National Bank, Investec, Nedbank, and Standard Bank hold over 90 percent of asset market share valued at approximately R5.8 trillion. The same report states that there are 31 bank entities in South Africa - 18 local banks and 13 local branches of foreign banks, and 4 additional mutual banks. As can be seen, despite the considerable number of bank brands, the sector is characterised by an oligopolistic market structure due to the dominance of a small number of banks. Moreover, a global brand valuer rating agency, BrandFinance, declared Standard Bank to be Africa's most valuable bank brand in 2022, valued at $1.583 billion, followed by First National Bank at number two with a brand value of $1.581 billion. ABSA ($1.437 billion), Nedbank ($1.018 billion), Investec ($992 million), and Capitec Bank ($625 million) are also among the leading bank brands in Africa (BrandFinance, 2022).

The South African banking sector faces reputational challenges emanating from service failures (Lappeman et al., 2021). Building reputable brands in a fiercely competitive South African banking sector is crucial, and we argue that this can be achieved through aligning brand identity and image. According to Lappeman et al. (2021); and Roberts-Lombard and Petzer (2021), brand preference in the sector is largely influenced by customers' perceptions of customer value. A major challenge in services branding is minimising the gap between consumer perceptions of the brand and the company's brand identity (Pinar et al., 2016). In this study, we investigate brand identity-image (in)congruency through exploring the fit of critical brand identity constituent dimensions with leading banks' business clients.

2. RESEARCH GAP

Academic research is underdeveloped in explicating brand identity-image multidimensionality in services sectors (Eklund & Helmefalk, 2022). Mingione (2015) postulates that extant brand identity theory underestimates complex sectors characterised by diverse contexts. Against this backdrop, the research gap identified in the current study is twofold. Firstly, it is not known whether brand identity is congruent with brand image in the South African banking sector. This study investigates this gap by exploring (in)congruence of brand identity constituent dimensions that are ubiquitous in this school, namely brand visual identity; personality; culture and values; differentiation; self-image/self-concept; reflection; and relationship (Kapferer, 2012; Roy & Banerjee 2014; Linsner et al., 2020). This research gap is substantive and consequential.

Secondly, extant schools in brand management are fragmented, and this may cause deficiencies in brand management practice and construct explication. This fragmentation can be attributed to myriad factors, including theoretical contributions over the years that are divergent in approach (Balmer, 2013; Veloutsou & Guzman, 2017; Schmidt & Redler, 2018). Primarily, the fragmentation of schools and conceptual ambiguities are caused by the existence of two divergent approaches in brand building, namely the inside-out brand orientation and the outside-in market/externally based approach (Hem & Supphellen, 2022). Allies of the former believe that brands are built within firms and communicated to receptive consumers. In the latter approach, it is believed that brands are built through a cognitive construction of external stakeholders' perceptions (Urde & Koch, 2014; Muhonen et al., 2017), whereas 'relationalists' propose a common ground where brand building is seen as an ongoing dynamic process comprising both internal and external voices (Schmidt & Redler, 2018; Ind & Schmidt, 2019). Against this background, the current study sought to provide a synthesis of the fragmented and overlapping schools of brand management through a framework that can guide brand managers in building coherent service brands.

3. METHODOLOGY

The determination of the most appropriate research methodology to uncover an inquiry is dictated to by the research problem at hand (Babin & Zikmund, 2016). Due to the paucity of academic research on brand identity and brand image, particularly in South African professional services, this study adopted methodological precepts of an interpretivist exploratory qualitative approach (Malhotra et al., 2017). Phase one of the study entailed extrapolating banks' brand identities for comparative purposes, and this was achieved through applying brand visual identity; brand personality; brand culture and values; brand differentiation; self-image/self-concept; reflection; and relationship in the study's context (de Chernatony, 2007; Kapferer, 2012). Therefore, individual in-depth interviews were conducted with selected banks' marketing executives who are experts responsible for brand identity construction (Cooper & Schindler, 2006). Moreover, through content analysis (Malhotra et al., 2017), we conducted a dialectical literature review of extant brand management approaches where the fragmentation of schools was detected (Heding et al., 2016, also noted by Balmer, 2013; Schmidt & Redler, 2018). Consequently, the study sought to achieve two fundamental research objectives.

RO1: To explore whether brand identity was congruent with the brand image in South African banks.

RO2: To forward an encompassing framework that consolidates the fragmented and overlapping schools of brand management.

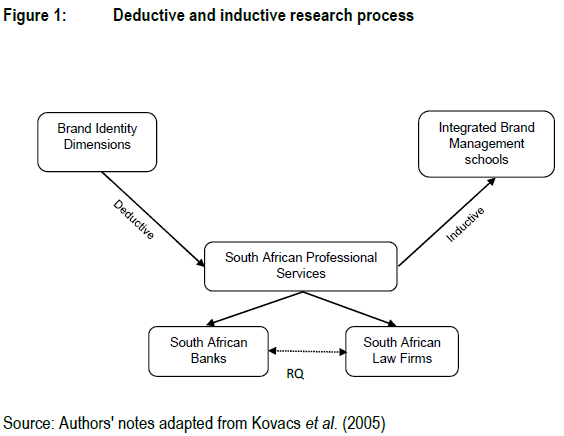

Figure 1 outlines the research process that was followed to achieve the study's objectives.

This study applied central brand identity dimensions in South African professional services. The initial research discourse was deductive. The first phase of the study deduced banks' brand identities to compare with business clients' image in the law firm sector. The findings of this empirical research process, coupled with the reconfiguration of the schools of brand management, resulted in the construction of a new framework, the Integrated Brand Management Schools' framework (IBMS); consequently, the research discourse and reasoning transformed into inductive (Hyde, 2000; Clow & James, 2014; Woiceshyn & Daellenbach, 2018).

3.1 Sample description

The study's primary context for brand distillation was the South African banking sector. As noted above BrandFinance rated Standard Bank, First National Bank, ABSA Bank, Nedbank, and Investec as the biggest bank brands in South Africa by brand value (BrandFinance, 2022). Concordantly, these brands collectively hold over 90 percent of the asset market share in the sector (BusinessTech, 2021b). Against this backdrop, the current study targeted these brands for an empirical exploration of brand identity-image fit. Our research approach is not concerned with the statistical generalisability of the findings but with naturalistic generalisability (Seidman, 2006; Bailey, 2007). However, the study sample suggests that both can be claimed due to the market dominance of the sample.

In-depth interviews were conducted with marketing executives responsible for brand identity formulation to extrapolate banks' brand identities. Consequently, eight marketing executives were interviewed (Bank A n=2; Bank B n=2; Bank C n=1; Bank D n=1; Bank E n=2). In certain banks, one marketing executive met the criterion and, in some cases, two executives (Feinberg et al., 2013). This sample selection was also guided by marketing research literature, Malhotra et al. (2017) suggest that in qualitative evolutionary studies, personal interviews with industry experts should be considered. Therefore, the sample inclusion criteria and technique were judgemental and non-probability sampling (Bryman et al., 2014). Consistency of research findings [(in)applicability] of brand identity dimensions] was evident after six bank marketing executives were interviewed, and saturation became apparent at eight interviews of rich data. Retrospective analysis indicated that this process was also consistent with the literature. In qualitative studies conducted in homogeneous contexts, saturation may occur after six interviews and become evident after twelve interviews (Boddy, 2016).

3.2 Data collection

The interviews were audio recorded and later transcribed to textual format for analysis purposes. The interviewer utilised an interview guide to conduct the interviews, and each question was linked to at least one of the brand identity dimensions under exploration. Themes were therefore predetermined in accordance with the brand identity dimensions under investigation for confirmation (Park & Park, 2017; Esfehani & Walters, 2018). A computerassisted qualitative data analysis program, ATLAS.ti, was used to code the data. The credibility of empirical studies is established by an audit trail, and research must clearly document all research activities and decisions (Creswell & Miller, 2000). ATLAS.ti also served this purpose in the current study.

Brand identity data was then analysed to distil banks' brand identities. The second phase of the study distilled banks' brand image from their business clients in the law firm sector in South Africa. Similarly, in the first phase, eight financial managers of law firms who were instrumental in deciding on the firms' bank brand preference were interviewed to deduce banks' brand image. The selected law firms are clients of the banks concerned; moreover, given the dearth of branding research in South African professional service, the law firm sector was a major inclusion criterion. Essentially, two separate but interrelated interview guides were constructed to achieve the study's primary objective. The brand image interview guide was also formulated using the same brand identity constituent dimensions; however, the questions were image-based. For instance, a bank would be asked to describe its brand personality from an identity viewpoint, whereas a client would be asked to describe their bank as a person from an image perspective. A comparison of the findings was used to determine (in)congruency (Aaker, 1997). The following section presents the results and discussion.

3.3 Research findings and discussion

In line with the study's agreed-upon ethical basis, banks' names were concealed. Thus, the five banks are reported as Bank A, B, C, D, and E. The application of brand identity dimensions to each bank is presented in direct quotations as elucidated by banks' marketing executives. Similarly, the construal of brand identity dimensions (image) is presented in direct quotations as explicated by law firm account managers to gauge (in)congruence. ATLAS.ti citations are referenced as follows: 2.3 We are the biggest bank brand in Africa (408:765). This indicates that the quotation comes from the second participant in a particular bank brand or law firm client, and the quotation is the third to be coded from the interview transcript. The quotation starts at character 408 and ends at 765 in the specific transcript. Visual identity findings are presented first.

3.3.1 Visual identity

Bank A: 1:33... So I think a lot of our brand distinctiveness comes through in how we show up quite physically and that can be in digital channels or physical channels. (14462:14922).

Client: 1:2 I think the colours are quite a big indicator when it comes to the top banks and obviously red being bank A (1007:1116).

Bank B: 2:1... what makes our brand stand out is our symbol. It's very iconic and recognisable. I think our symbol is definitely our strongest visual (506:891).

Client: 1:1 Their payoff-line, 'How can we help you?', they are always available we can contact them anytime (659:752).

Bank C: 1:1 The zebra is the first one that is recalled by most of our clients. Clients and nonclients will recognise the zebra. It makes us stand apart (366:739).

Client: 1:1 So visually, everyone knows the zebra image (581:650).

Bank D: 1:25 Our green, it stands out, it means so many things. Green is nurturing, it's earthy, it's speaks to life and what-not but on the other side it speaks to affluence and aristocracy (12406:12677).

Client: 1:1 The green, I guess, the green bank, the colours and the N of bank D (683:751).

Bank E: 2:2 ...our colour palettes and our primary colour, which is blue. It's the electric blue we use largely but there is a range of blues that we use. ..(1095:1527).

Client: 2:2 ...blue I think they've taken enough abuse about their tag line and I do think moving forward is a nice piece but initially, when it rolled out that moving forward sign (1556:1739).

Keller and Swaminathan (2020) posit that collectively brand elements (colours, logos, slogans) formulate brand identity and are triggered in consumers' minds when a brand is distinct (Chevalier & Mazzalovo, 2008). Concordantly, Buil et al. (2017) and Erjansola (2021) postulate that colours, logos, and font are key visual identity elements that make brands identifiable and distinguishable. As can be seen in the findings presented above, visual identity was applicable in all bank brands. Moreover, from an imaging viewpoint, clients could recall and link their banks' visual identity elements. It can therefore be concluded that banks' visual identity is aligned with clients' deductions.

3.1.2 Brand personality

Bank A: 1:6 I think it is an innately optimistic individual who believes in the potential and possibility of this continent and its people (2386:2585).

Client: 1:51 don't think any. I can't think of how I would describe them, no, nothing comes to mind (1851:1941).

Bank B: 2:5 As a friend. Someone who would help you in everyday life (1889:1956).

Client: 1:3 Oh, that a difficult one, I'm not sure, I wouldn't assign a personality to them (1100:1179).

Bank C: 1:6 Innovative, ambitious, distinctive, fast-moving, warm, human, friendly, engaging, people matter... (2916:3100).

Client: 1:9 Efficiency.... There's no frills and fuss, it's what you see is what you get (1554:1649).

Bank D: 1:6 I would describe the brand as both knowledgeable and clear in how it helps people to see, to treat money differently... (1954:2592).

Client: 1:8 If I had to put a gender, I'd definitely say male, white male, white Afrikaans male but friendly not like those like Afrikaans males, friendly Afrikaans, white male, old, that's how I describe it as a person (2211:2416).

Bank E: 1:11 ...we are smart, we're astute, we're ambitious, we're courageous, we're in touch with what's going on in the world around us ... (5260:6385).

Client: 2:5 Solid, reliable, sufficient breadth, so they've got breadth knowledge of the continent. Engaging, willing to partner with you in terms of your initiatives across the region, yes (3269:3458).

Coined by Aaker (1997), brand personality is an important brand identity constituent dimension. The fundamental basis of the construct is endowing brands with human traits. It is a well-accepted phenomenon in brand literature that consumers purchase brands for various reasons, including brand association, to communicate their own identities (Burmann et al., 2017; Tarabashkina et al., 2021). Based on the brand personality findings presented above, it is evident that brand personality is applicable to bank brands. However, there is a clear incongruence between what banks purport as their brand personalities compared to clients' construal.

The purpose of the data presented above is to demonstrate how the study's conclusions were derived. Figure 2 depicts the study's holistic findings. To present a mind map of the findings, we borrowed from the theory of alignment in mechatronics. Dimensional identity-image fit is depicted by the thrust line (dotted line) coinciding with the centre line (straight line), whereas the thrust angle (the gap between thrust and centre line) depicts dimensional misalignment (Bailey et al., 1986; Noble et al., 2016).

3.1.3 Brand values and culture

Alvarado and Guzman (2020) postulate that a brand's identity and purpose should be crafted in a manner that is consistent with its values and culture. Core brand values and culture are central to brand identity construction, and they often emanate from brand developers and origin (Randle & Zainuddin, 2022). The study found culture and values dimensions applicable in the banking sector. However, no alignment was found between banks' accounts of their values and culture versus their clients' construal. Hence Figure 2 shows a thrust angle between brand values and culture and clients' image. The quotations below are clients' account of their banks' values and culture.

Bank A client; 2:4 ... their values are building, especially now that Barclays left. They have to build now from scratch basically (2068:2542).

Bank B client: 2:3 No, I don't know (3306:3328).

Bank D client 2:71 think the culture seems to be aware of what they don't do well, wanting to do it better.

(4368:4456).

Bank E clients 1:61 think their culture is quite relaxed and I'm talking from an outsider, but I believe their culture is inclusive and I say that because it's not for business continuity perspective, it's not just one person that they send us (2663:2888).

3.1.4 Relationship

A relationship defines services sectors as services are essentially relationships (Kapferer, 2012). Professional services are concerned with creating and sustaining long-term relationships with clients for long-term profit purposes. On the other hand, clients may seek long-term relationships with brands for association purposes where they find resonance with such brands (Keller & Swaminathan, 2020; Sharma et al., 2022). The centre line and thrust line coincide in Figure 2. This depicts fit in the relationship dimension; hence it can be concluded that banks' account of the relationship dimension is consistent with that of their business clients. See some of the quotations that support these conclusions:

Bank A; 1:21... We're looking for people who want to be on a journey with us, to help us cocreate that future (8150:8443).

Client: 1:9 ... We're at a point where we have a very good bond with specific individuals that have been with, banking with us or working with us for quite some time (3821:3980).

Bank B: 2:111 would like to think we're best friends (4362:4403).

Client: 1:6 Our relationship is very good, I would say it's a solid relationship (2201:2271).

3.1.5 Self-image/self-concept and reflection.

The study found self-image and reflection inapplicable from an identity viewpoint. According to Kapferer (2012), self-image is the picture consumers have of themselves based on brand association. Self-concept is customer-based, which is inherently situated outside the control of the firm. The construct is based on consumers' idealised version of themselves based on brand consumption (Saenger et al., 2020; Grimm & Wagner, 2021). Even though Kapferer (2012) situates the self-image dimension in the picture of the receiver in the Brand Identity Prism, the dimension is positioned as a brand identity construct. Similarly, reflection or social self is customer-based, as it refers to how consumers would like to be perceived by the public based on brand association (Kapferer, 2012; Saenger et al., 2020). Against this backdrop, we argue that it is implausible to build a brand's identity with what appear to be brand image elements. As can be seen in Figure 2, this study does not recognise self-image and reflection as brand identity dimensions. Therefore, from an identity perspective, banks' marketing executives can only depict an idealised or imagined client self-image and reflection.

The data presented above, and the related discussion, addressed the study's first objective. Primarily, the study sought to explore banks' brand identity-image in(congruence) with their business clients. This data provides evidence of a brand identity-image misfit in the sector. Even though brand identity-image misalignment may be attributed to a myriad of factors, the current research studied specific brand identity dimensions. In the following section, we submit theoretical postulations on probable antecedents to brand identity misalignment and subsequently submit a framework that may be a panacea to building aligned services brands.

4. THEORETICAL AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

Brand identity-image incongruence in South African professional services can be attributed to two factors. Firstly, the absence of an alignment framework: the congruence framework submitted by Zwakala and Steenkamp (2021a) remains conceptual due to a lack of empirical testing and practical application. Secondly, extant brand management approaches are fragmented and somewhat divergent. Consequently, brand managers lack a blueprint to build coherent service brand identities (Siano et al., 2022). The current study seeks to address this lacuna, its second research objective.

4.1 Theoretical implications

The field of brand management has revolutionised over the years (Ind, 1997; & Guzman, 2017). Schmidt and Redler (2018) attribute the fragmentation in the field to this revolution coupled with growing interest in corresponding brand management schools. The premise of the schools' contestation and what appears to be divergent points of departure is whether the brand-building process should initially begin inside or outside an organisation (Urder, 1999; Urde & Koch, 2014; Muhonen et al., 2017). However, some scholars (Ind & Schmidt, 2020) see a common ground between the inside-out and outside-in approaches. They argue that brand management may be an ongoing dynamic process co-created between brands and outside stakeholders.

Against this background, the current paper consolidates the various schools into one integrated school of brand management (Figure 3). This framework postulates that brand identity, brand image and brand co-creation are the primary schools of brand management. We submit that all other purported 'independent' schools are sub-dimensions of these primary schools. Schmidt and Redler (2018:191) foresaw that it was the nature of research that points of criticism and reduction of complexity were inevitable in the schools. Figure 3 below consolidates the schools of brand management into a framework that can be operationalised by practitioners.

Extant brand management literature presents 17 schools of brand management, namely the economic, identity, consumer-based, personality, relationships, experiential, community, cultural, co-creative, image, behavioural, strategy, philosophical, marketing, omni-brand, performance, and corporate brand schools (Balmer, 2013; Heding et al., 2016; Beverland, 2018; Schmidt & Redler, 2018). Below we theorise why these schools are sub-dimensions in the three primary schools depicted in Figure 3.

• Strategic brand identity school: The premise of the brand identity school is that brands are initially built within the confines of an organisation. Brand identity comprises unique organisational features such as visual elements for identification and differentiation purposes (Keller & Swaminathan, 20202). It is crafted in a manner that is consistent with the organisational culture and values system and integrative to a broader brand strategy (Melewar et al., 2017; Alvarado-Kartste & Guzman, 2020). Concordantly, the strategy school argues that alignment between brand and business strategy is fundamental to foster a brand-oriented culture, as the two have reciprocal effects (Abratt & Mingione, 2017; Schmidt & Redler, 2018). Similarly, the philosophical school (which advocates for brand building as an organisational mindset) is also inherent in brand identity, as brand building is accepted as an organisational ethos (Balmer, 2013).

Furthermore, the economic school views brand meaning as emanating from an investment in the marketing mix (7Ps). This approach too is internally/identity driven based on marketing strategy and issues such as product development and resource allocation (Aaker, 1996; Beverland, 2018; Heding et al., 2016; Goi, 2009). Similarly, the performance school encompass overall organisational performance based on brand and financial performance. Brand performance is based on equity attainment, while financial performance is based on financial objectives versus market share (Sultan & Wong, 2019; Keller & Swaminathan, 2020). Organisations, too, are brands; according to Balmer (2013) and Urde (2016), corporate brand investment is channelled towards building the organisation as a brand rather than individual product brands (Sarasvuou, 2021). Bridson and Evans (2004), also quoted by Balmer (2013), allude to the omni-brand school, which relates to an organisation's brands and products in their entirety. Modern literature refers to brand architecture which outlines boundaries and relationships across a firm's products (Keller, 2015; 2018; Leijerholt et al., 2018)

Moreover, brand personality is a pervasive dimension in brand identity models (brand identity planning model (Aaker, 1996), components of brand identity (de Chernatony, 2007), and Brand Identity Prism (Kapferer, 2012). Its theoretical foundation is endowing brands with human traits; therefore, the construct is crafted within firms (Burmann et al., 2017; Tarabashkina et al., 2021). Similarly, brand culture is central to brand identity construction, and it often emanates from a brand's developers and origin. Alvarado and Guzman (2020) posit that a brand's identity and purpose should be crafted in a manner that is consistent with organisational values and culture. Even though brand sub-cultures may be developed by brand communities, the initial culture construction is inherently internal to firms (Randle & Zainuddin, 2022). Lastly, at the heart of building brand identity is fostering strong positive relationships among internal staff and between staff and all stakeholders (Terglav et al., 2016; Tuskej & Podnar, 2018).

• Consumer-based brand image school: There is no consensus on the roots of brand image in extant literature. On the one hand, brand image is understood as a consumer's brand identity interpretation (Kapferer, 2012). On the other hand, brand image is theorised as an independent approach based on positioning (Ries & Trout, 2001). Nonetheless, a consistent position of the brand image school is that the consumer's perspective is central to understanding and developing brands (Urde & Koch, 2014; Muhonen et al., 2017). The behavioural school adopts a similar approach. According to Balmer (2013) and Schmidt and Redler (2018), the basis of the behavioural school is the external stakeholders' construction of brand association through the systematic use of brand communication channels. Synonymously, the consumer-based school argues that brands exist in the minds of consumers and are created through a cognitive process (Heding et al., 2016; Beverland, 2018). The customer-based brand equity thesis is based on this premise, and the community school is articulated at the resonance stage of the CBBE pyramid, where the customer-brand relationship is solidified (Keller & Swaminathan, 2020).

• Brand co-creation: Recent developments in branding theory suggest a paradigm shift towards a more agile approach in brand building through brand co-creation (Schmeltz & Kjeldsen, 2018; Ind & Schmidt, 2019). Contrary to firm-based, 'prescriptive' brand-building approaches, the agile school appreciates the interaction between employees and consumers, particularly in services sectors, where the consumer is a co-creator of value (Saleem & Iglesias, 2016). Brand co-creation affords external stakeholders the platform to interact with one another and to express or adjust their individual brand identity to align with that of the actual services brand (Black & Veloutsou, 2017; Iglesias et al., 2020; Iglesias & Ind, 2020). The dialogue between employees and consumers determines the service experience and value creation. Service experience is a critical brand performance indicator which is derived from the coordination between a firm, its employees, and its customers (Polegato & Bjerke, 2019). Therefore, the co-creation school is inherent to the services sectors. The marketing of services is characterised by three interlinking entities: firms, employees, and customers (Anderson & Smith, 2017). Collectively, they co-create service brands through an interactive and negotiated process. Therefore, the roots and essence of services brand identity-image fit are determined by the three audiences through collective service provision and experience, which occur simultaneously (Itani et al., 2022; Zeithaml et al., 2006). Servicescape is particularly important in professional services as it makes the service process 'tangible' (Ding & Keh, 2017:848-849). Our retrospective analysis of the methodological and practical precepts of services provision suggests that it is indeed inconceivable that service brand identities can be created without the full participation of consumers (Hoang et al., 2018). Consequently, we submit Figure 3 as a guiding framework to service brand managers to build coherent brand identities.

4.2 Managerial implication

The study's managerial contributions in professional services sectors are two-fold. Firstly, the findings present disparities between South African banks' brand identity constituent dimensions and how the dimension is interpreted and misconstrued by clients. For instance, banks' brand personalities were found incongruent with clients' construal. Fundamentally, brand personality endows brands with humanlike traits. Brand personality characteristics such as competence, credibility, and trustworthiness should permeate professional services sectors such as financial services and law firm sectors (Burmann et al., 2017). When aligned, services brand personality and customer interpretation can yield long-term customer-brand relationships and resonance. Secondly, this study found banks' brand culture and values to be misunderstood by their clients in the law firm sector. Brand culture and values are critical dimensions in building coherent services brand identities, and their clear communication is crucial. These findings may be useful to managers to rethink their design of brand identity elements such as brand culture and values. Even though, in certain instances, brand culture and values emanate from brand developers and their geographic origins, brands can encounter cultural backlash, especially in foreign markets (Beverland, 2018). Therefore, the misfit between banks' brand personalities and brand culture and values are useful findings for banks' brand managers to rethink and apply a collaborative and agile approach in their brand strategy formulation. Against this backdrop, we submit that brand managers should consider co-creating brand identity with all stakeholders to build coherent professional services brands. Consequently, this study suggests a new comprehensive framework that may serve as an apparatus to guide professional services brand managers in building coherent services brand identities through brand co-creation.

5. CONCLUSION

The brand management corpus is largely fragmented due to growing interests in corresponding and divergent brand management schools. Primarily, the contestation is between the inside-out and outside-in brand-building approaches. The former approach adopts brand orientation and internal stakeholder bias as the premise of brand building. Whereas the outside-in approach adopts consumer-centrism as an ethos. On the other hand, some scholars (Ind & Schmidt, 2020) see a common ground between the two divergent approaches, the co-creative agile approach. This school holds that brand building is a dynamic process negotiated and co-created between brands and outside stakeholders.

Through brand identity and brand image lens, we empirically explored the approach/s applied in South African banks. The findings revealed disparities between banks' brand identities and their image as construed by clients in the law firm sector. In essence, banks adopt an inside-out approach with little or no consideration of outside stakeholders. These are peculiar research findings considering that services are inherently negotiated and co-created between firms and consumers due to inherent characteristics such as inseparability. Therefore, it is inconceivable that service brands can adopt a one-dimensional prescriptive brand-building approach. Against this backdrop, we submit a brand co-creation framework that may serve as a blueprint for building coherent South African professional services brands.

REFERENCES

Aaker, D. 1996. Building strong brands. London: Simon and Schuster. [ Links ]

Aaker, J.L. 1997. Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3):347-356. [https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379703400304]. [ Links ]

Abratt, R. & Mingione, M. 2017. Corporate identity, strategy and change. Journal of Brand Management, 24(2):129-139. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-017-0026-8]. [ Links ]

Alvarado-Karste, D. & Guzman, F. 2020. The effect of brand identity-cognitive style fit and social influence on consumer-based brand equity. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 29(7):971-984. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2019-2419]. [ Links ]

Amaro, S., Barroco, C. & Antunes, J. 2021. Exploring the antecedents and outcomes of destination brand love. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 30(3):433-448. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2487]. [ Links ]

Anderson, S. & Smith, J. 2017. An empirical examination of the services triangle. Journal of Services Marketing, 31(3):236-246. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-12-2015-0369]. [ Links ]

Babin, B. & Zikmund, W. 2016. Exploring marketing research. 11th ed. Boston: Cengage. [ Links ]

Bailey, C.A. 2007. A guide to qualitative field research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press. [https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412983204]. [ Links ]

Bailey, M.P., Brooks, R.G., Frank, J.R., Johnson, J.J.J. & Maholm, M.B. 1986. Apparatus for determining the relationship of vehicle thrust line and body centerline for use in wheel alignment. United Stated Patents: 4,615,618. [ Links ]

Bakri, M., Krisjanous, J. & Richard, J.E. 2020. Decoding service brand image through user-generated images. Journal of Services Marketing, 34(4):429-442. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-11-2018-0341]. [ Links ]

Balmer, J.M.T. 2012. Strategic corporate brand alignment. European Journal of Marketing, 46(7/8):1064-1092. [https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561211230205]. [ Links ]

Balmer, J.M.T. 2013. Corporate brand orientation: what is it? what of it? Journal of Brand Management, 20(9):723-741. [https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2013.15]. [ Links ]

Beverland. M. 2018. Brand management: co-creating meaningful brands. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Black, I. & Veloutsou, V. 2017. Working consumers: co-creation of brand identity, consumer and community identity. Journal of Business Research, 70:416-429. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.07.012]. [ Links ]

Boddy, C.R. 2016. Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 19(4):426-432. [https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053]. [ Links ]

Boisvert, J. & Ashill, N.J. 2022. The impact of gender on the evaluation of vertical line extensions of luxury brands: a cross-national study. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(3):484-495. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-09-2020-3119]. [ Links ]

BrandFinance2022. Standard Bank is crowned Africa's most valuable banking brand. [Internet: https://brandfinance.com/press-releases/standard-bank-is-crowned-africas-most-valuable-banking-brand; downloaded on 22 May 2022]. [ Links ]

Bridson, K. & Evans, J. 2004. The secret to a fashion advantage is brand orientation. International Journal of Retail Distribution Management, 32(8):403-411. [https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550410546223]. [ Links ]

Bryman, A., Bell, E., Hirschsohn, P., Do Santos, P., Du Toit, J., Masenge, A., Aardt, I. & Wagner, C. 2014. Research methodology: business and management context. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Buil, I., Catalán, S. & Martínez, E. 2016. The importance of corporate brand identity in business management: An application to the UK banking sector. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(1):3-12. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2014.11.001]. [ Links ]

Burmann, C., Riley, N.M., Halaszovich, T. & Schade, M. 2017. Identity-based brand management: fundamental strategy- implementation-control. Wiesbaden: Springer. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-13561-4]. [ Links ]

BusinessTech. 2021a. These are South Africa's biggest banks in 2021. [Internet: https://businesstech.co.za/news/banking/502541/these-are-south-africas-biggest-banks-in-2021/; downloaded on 22 May 2022]. [ Links ]

BusinessTec. 2021b. How South Africa's 5 biggest banks continue to dominate. [Internet: https://businesstech.co.za/news/banking/506740/how-south-africas-5-biggest-banks-continue-to-dominate/; downloaded on 22 May 2022]. [ Links ]

Butcher, J. & Pecot, F. 2022. Visually communicating brand heritage on social media: champagne on Instagram. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(4):654-670. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2021-3334]. [ Links ]

Chevalier, M. & Mazzalovo, G. 2008. Luxury brand management: a world of privilege. 4th ed. Singapore: Wiley. [ Links ]

Chorn, N.H. 1991. The alignment theory: creating strategic fit. Management Decision, 29(1):20-24. [https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000000066]. [ Links ]

Chung, S.Y.S. &Byrom, J. 2021. Co-creating consistent brand identity with employees in the hotel industry. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 30(1):74-89. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2544]. [ Links ]

Clow, K.E. & James, K.E. 2014. Essentials of marketing research: putting research into practice. London: Sage. [https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384726]. [ Links ]

Coleman, D.A., De Chernatony, L. & Christodoulides, G. 2011. B2B service brand identity: scale development and validation. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(7):1063-1071. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.09.010]. [ Links ]

Confente, I. & Kucharska, W. 2021. Company versus consumer performance: does brand community identification foster brand loyalty and the consumer's personal brand? Journal of Brand Management, 28:8-31. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00208-4]. [ Links ]

Cooper, D. & Schindler, P.S. 2006. Marketing research. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. & Miller, D.L. 2000. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3):124-130. [https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip39032]. [ Links ]

Cullinan, J.A., Abratt, R. & Mingione, M. 2021. Challenges of corporate brand building and management in a state-owned enterprise. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 30(2):293-305. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2522]. [ Links ]

De Chernatony, L. 2007. From brand vision to brand evaluation: the strategic process of growing and strengthening brands. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier. [https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080459660]. [ Links ]

Dehling, S., Edvardsson, B. & Tronvoll, B. 2022. How do actors coordinate for value creation? A signalling and screening perspective on resource integration. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(9):18-26. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-02-2020-0068]. [ Links ]

Deng, N., Jiang, X. & Fan, X. 2022. How social media's cause-related marketing activity enhances consumer citizenship behaviour: the mediating role of community identification. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(1):38-60. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-01-2020-0014]. [ Links ]

Ding, Y. & Keh, H.T. 2017. Consumer reliance on intangible versus tangible attributes in service evaluation: the role of construal level. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(6):848-865. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0527-8]. [ Links ]

Eklund, A.A. & Helmefalk, M. 2022. Congruency or incongruency: a theoretical framework and opportunities for future research avenues. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(4):606-624. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-03-2020-2795]. [ Links ]

Endo, A.C.B., de Farias, L.A. & Coelho, P.S. 2019. Services branding from the perspective of higher education administrators. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 37(4):401-416. [https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-06-2018-0237]. [ Links ]

Erjansola, A., Lipponen, J., Vehkalahti, K., Aula, H. & Pirttila-Backman. H. 2021. From the brand logo to brand association and the corporate identity: visual and identity-based logo association in a university merger. Journal of Brand Management, 28(3):241-253. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00223-5]. [ Links ]

Esfehani, M.H. & Walters, T. 2018. Lost in translation? cross-language thematic analysis in tourism and hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(11):3158-3174. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2017-0701]. [ Links ]

Feinberg, M.F., Kinnear, T.C. & Taylor, J.R. 2013. Modern marketing research: concepts, methods, and cases. 7th ed. New York: Cengage. [ Links ]

Ghodeswar, B. M. 2008. Building brand identity in competitive markets: a conceptual model. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 17(1):4-12. [https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420810856468]. [ Links ]

Goi, C.L. 2009. A review of marketing mix: 4Ps or more? International Journal of Marketing Studies, 1(1):1-15. [https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v1n1p2]. [ Links ]

Grimm, M.S. & Wagner, R. 2021. Intra-brand image confusion: effects of assortment width on brand image perception. Journal of Brand Management, 28(4):446-463. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00225-3]. [ Links ]

Guzel, M., Sezen, B. & Alniacik, U. 2021. Drivers and consequences of customer participation into value co-creation: a field experiment. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 30(7):1047-1061. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-04-2020-2847]. [ Links ]

Heding, T., Knudtzen, C.F. & Bjerre, M. 2016. Brand Management: research, theory and practice. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315752792]. [ Links ]

Hem, A.F. & Supphellen, M. 2022. Developing and testing a typology of brand benefit differentiation. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(2):238-251. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2019-2412]. [ Links ]

Hoang, H.T., Hill, S.R., Lu, V.N. & Freeman, S. 2018. Drivers of service climate: an emerging market perspective. Journal of Service Marketing, 32(4):476-492. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-06-2017-0208]. [ Links ]

Huaman-Ramirez, R. & Merunka, D. 2021. Celebrity CEO's credibility, image of their brands and consumer materialism. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 38(6):638-651. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-08-2020-4026]. [ Links ]

Hyde, K. F. 2000. Recognising deductive processes in qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 3(2):82-89. [https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750010322089]. [ Links ]

Iglesias, O. & Ind, N. 2020. Towards a theory of conscientious corporate brand co-creation: the next key challenge in brand management. Journal of Brand Management, 27:710-720. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00205-7]. [ Links ]

Iglesias, O., Landgraf, P., Ind, N., Markovic, S. & Koporcic, N. 2020. Corporate brand identity co-creation in Business-to-business contexts. Industrial Marketing Management, 85:32-43. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.09.008]. [ Links ]

Ind, N. 1997. The corporate brand. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230375888]. [ Links ]

Ind, N. & Schmidt, H.J. 2019. Co-creating brands: brand management from a co-creative perspective. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Indounas, K. & Arvanti, A. 2015. Success factors of new health-care services. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 24(7):693-705. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-04-2014-0541]. [ Links ]

Islam, T. & Hussain, M. 2022. How consumer uncertainty intervenes country of origin image and consumer purchase intention? The moderating role of brand image. International Journal of Emerging Markets, [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-08-2021-1194]. [ Links ]

Itani, O.S. 2021. "Us" to co-create value and hate "them": examining the interplay of consumer-brand identification, peer identification, value co-creation among consumers, competitor brand hate and individualism. European Journal of Marketing, 55(4):1023-1066. [https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-06-2019-0469]. [ Links ]

Itani, O.S., Chonko, L. & Agnihotri, R. 2022. Salesperson moral identity and value co-creation. European Journal of Marketing, 56(2):500-531. [https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-06-2020-0431]. [ Links ]

Iyer, P., Davari, A., Srivastava, S. & Paswan, A.K. 2021. Market orientation, brand management processes and brand performance. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 30(2):197-214. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2019-2530]. [ Links ]

Kamboj, S., Sarmah, B., Gupta, S. & Dwivedi, Y. 2018. Examining branding co-creation in brand communities on social media: Applying the paradigm of stimulus-organism-response. International Journal of Information Management, 39:169-185. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.12.001]. [ Links ]

Kapferer, J.N. 2012. The new strategic brand management: advanced insights & strategic thinking. 5th ed. London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

Kara, S., Gunasti, K.. , William, T. & Ross, W.T. 2020. My brand identity lies in the brand name: personified suggestive brand names. Journal of Brand Management, 27(27):607-621. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00201-x]. [ Links ]

Keller, K.L. 2013. Strategic brand management. London: Pearson. [ Links ]

Keller, K.L. 2015. Designing and implementing brand architecture strategies. Journal of Brand Management, 21(9):702-715. [https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2014.38]. [ Links ]

Keller, K.L. & Swaminathan, V. 2020. Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. 5th ed. Harlow: Pearson. [ Links ]

Keller, K.L. 2018. Brand. In Augier, M. & Teece, D.J. (eds), The Palgrave Encyclopaedia of Strategic Management. Hanover: Macmillan, pp. 123-127. [ Links ]

Kovacs, G., Spens, K.M. & van Hoek, R. 2005. Abductive reasoning in logistics research. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 35(2):132-144. [https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030510590318]. [ Links ]

Kumar, V., Rajan, B., Gupta, S. & Pozza, I.D. 2017. Customer engagement in services. Journal of Brand Management, 47:138-160. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0565-2]. [ Links ]

Kuuru, T. & Narvanen, E. 2022. Talking bodies-and embodiment approach to service employees' work. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(3):313-325. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-02-2020-0060]. [ Links ]

L'Ecuyer, F. & Raymond, L. 2017. Aligning the e-HRN and strategic HRM capabilities of manufacturing SMSs: a 'Gestalts' perspective. In Bondarouk, T., Ruël, H. & Parry, E (eds). Electronic HRM in the smart era. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, p. 353. [https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78714-315-920161006]. [ Links ]

Lappeman, J., Clark, R., Evans, J. & Sierra-Rubia, L. 2021. The effect of NWOM firestorms on South African retail banking. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(3):455-477. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-07-2020-0403]. [ Links ]

Lee, J.L., Kim, Y. & Won, J. 2018. Sports brand positioning: positioning congruence and consumer perceptions towards brands. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorships, 19(4):450-471. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-03-2017-0018]. [ Links ]

Leijerholt, U., Chapleo, C. & O'Sullivan, H. 2018. A brand within a brand: an integrated understanding of internal brand management and brand architecture in the public sector. Journal of Brand Management, 26:277-290. [ Links ]

Levy, S. 2022. Brand banks attachment to loyalty in digital banking services: mediated by psychological engagement with services platforms and moderated by platform types. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(4):679-700. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2021-0383]. [ Links ]

Li, Y., Zhang, C., Shelby, L. & Huan, T. 2021. Customers' self-image congruity and brand preference: a moderated mediation model of self-brand connection and self-motivation. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(5):797-807. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-07-2020-2998]. [ Links ]

Lipkin, M. & Heinonen, K. 2022. Customer ecosystems: exploring how ecosystem actors shape customer experience. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(9):1-17. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-03-2021-0080]. [ Links ]

Liu, C., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, J. 2020. The impact of self-congruity and virtual interactivity on online celebrity brand equity and fans' purchase intentions. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 29(6):783-801. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-11-2018-2106]. [ Links ]

Lozza, E., Castiglioni, C., Bonanomi, A. & Poli, A. 2022. Money as a symbol in the relationship between financial advisors and their clients: a dyadic study. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(4):613-630. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-04-2021-0124]. [ Links ]

Lu, Y., Wang, Z., Yang, D. & Kakuda, N. 2022. To be or not to be equal: the impact of pride on brands associated with dissociative out-groups. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(1):127-148. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-05-2020-2889]. [ Links ]

Malhotra, N.K., Nunan, D. & Birks, D.F. 2017. Marketing research: an applied approach. 5th ed. London: Pearson. [https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315088754]. [ Links ]

McManus, J.F., Carvalho, S.W. & Trifts, V. 2022. The role of brand personality in the formation of consumer affect and self-brand connection. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(4):551-569. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-08-2020-3039]. [ Links ]

Melewar, T.C., Foroudi, P., Gupta, S., Kitchen, P.J. & Foroudi, M. 2017. Integrating Identity, strategy and communications for trust, loyalty and commitment. European Journal of Marketing, 51(3):572-604. [https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-08-2015-0616]. [ Links ]

Mingione, M. 2015. Inquiry into corporate brand alignment: a dialectical analysis and directions for future research. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 24(5):518-536. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-05-2014-0617]. [ Links ]

Momen, M.A., Sultana, S. & Haque, A.K.M.A. 2020. Web-based marketing communication to develop brand image and brand equity of higher educational institutions: a structural equation modelling approach. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 69(3):151-169. [https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-10-2018-0088]. [ Links ]

Muhonen, T., Hirvonen, S. & Laukkanen, T. 2017. SME brand identity: its components and performance effects. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 26(1):52-67. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2016-1083]. [ Links ]

Nel, J. & Boshoff, C. 2022. Traditional-banks customers; digital-only bank resistance: evidence from South Africa. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(3):429-254. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-07-2020-0380]. [ Links ]

Noble, S.D., Van Meter, M.J. & Martin, J. 2016. Frame hanger for providing thrust angle alignment in vehicle suspension. United States Patents: 9,315,083 B2. [ Links ]

Park, S.B. & Park, K. 2017. Thematic trends in event management research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(3):848-861. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2015-0521]. [ Links ]

Pinar, M., Girard, T., Trapp, P. & Eser, Z. 2016. Services branding triangle: examining the triadic service brand promises for creating a strong brand in the banking industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 34(4):529-549. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-04-2015-0043]. [ Links ]

Polegato, R. & Bjerke, R. 2019. Looking forward: anticipation enhances service experience. Journal of Services Marketing, 33(2):148-159. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-02-2018-0064]. [ Links ]

Pranjal, P. & Sarkar, S. 2020. Corporate brand alignment in business markets: a practical perspective. Market Intelligence and Planning, 38(7):907-920. [https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-10-2019-0539]. [ Links ]

Qiao, F. & Griffin, W.G. 2022. Brand initiation strategy, package design and consumer response: what does it take to make a difference? Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(2):177-188. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-05-2019-2363]. [ Links ]

Quiros, I. 2009. Organisational alignment: a model to explain the relationships between organization relevant variables. International Journal of Organisational Analysis, 17(4):285-305. [https://doi.org/10.1108/19348830910992103]. [ Links ]

Randle, M. & Zainuddin, N. 2022. Value creation and destruction in the marketisation of human services. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(3):326-339. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-10-2019-0424]. [ Links ]

Ries, A. & Trout, J. 2001. Positioning: the battle for your mind. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Rindell, A. & Santos, F.P. 2021. What makes a corporate heritage brand authentic for consumers? a semiotic approach. Journal of Brand Management, 28:545-558. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-021-00243-9]. [ Links ]

Robbanee, F.K., Roy, R. & Spence, M.T. 2020. Factors affecting consumer engagement on online social networks: self-congruity, brand attachment, and self-extensions tendency. European Journal of Marketing, 54(6):1407-1431. [https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2018-0221]. [ Links ]

Roberts-Lombard, M. & Petzer, D.J. 2021. Relationship marketing: an S-O-R perspective emphasising the importance of trust in retail banking. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(5):725-750. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2020-0417]. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, P., Borges, A.P. & Sousa, A. 2021. Authenticity as an antecedent of brand image in a positive emotional consumer relationship: the case of craft beer brands. EuroMed Journal of Business, 17(4):634-651. [https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-03-2021-0041]. [ Links ]

Roy, D. & Banerjee, S. 2014. Identification and measurement of brand identity and image gap: a quantitative approach. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 23(3):207-219. [ Links ]

Saenger, C., Thomas, V.L. & Bock, D.E. 2020. Compensatory word of mouth as symbolic self-completion when talking about a brand can restore consumers' self-perceptions after self-threat. European Journal of Marketing, 54(4):671-690. [https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2018-0206]. [ Links ]

Saleem, F.Z. & Iglesias, O. 2016. Mapping the domain of the fragmented field of internal branding. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 25(1):43-57. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-11-2014-0751]. [ Links ]

Sander, F., Fohl, U., Walter, N. & Demmer, V. 2021. Green or social? an analysis of environmental and social sustainability advertising and its impact on brand personality, credibility and attitude. Journal of Brand Management, 28:429-445. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-021-00236-8]. [ Links ]

Sarasvuo, S. 2021. Are we one, or are we many? diversity in organisational identities versus corporate identities. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 30(6):788-805. [ Links ]

Satini, F.D.O., Ladeira. W.J., Sampaio, C.H. & Pinto, D.C. 2018. The brand experience extended model: a meta-analysis. Journal of Brand Management, 25(6):519-535. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0104-6]. [ Links ]

Schmeltz, L. & Kjeldsen, A.K. 2019. Co-creating polyphony or cacophony? A case study of a public organisation's brand co-creation process and the challenge of orchestrating multiple internal voices. Journal of Brand Management, 26:304-316. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0124-2]. [ Links ]

Schmidt, J.H. & Redler, J. 2018. How diverse is corporate brand management research? comparing schools of corporate brand management with approaches to corporate strategy. Journal Product and Brand Management, 27(2):185-202. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-05-2017-1473]. [ Links ]

Seidman, I. 2006. Interviewing as qualitative research: a guide for researchers in education and social sciences. 3rd edition. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Sharma, A., Patro, S. & Chaudhry, H. 2022. Brand identity and culture interaction in the Indian context: a grounded approach. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 19(1):31-54. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-12-2020-0361]. [ Links ]

Siano, A., Confetto, M.G., Vollero, A. & Covucci, C. 2022. Redefining brand hijacking from a non-collaborative brand co-creation perspective. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 31(1):110-126. [ Links ]

Sihvonen, J. 2019. Understanding the drivers of consumer-brand identification. Journal of Brand Management, 26(5):583-594. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-00149-z]. [ Links ]

Srivastava, R.K. & Thomas, G.M. 2010. Managing brand performance: aligning positioning, execution and experience. Journal of Brand Management, 17(7):465-471. [https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2010.11]. [ Links ]

Steenkamp, P. 2016. Towards a client-based brand equity framework for selected business-to-business services. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. (PhD thesis). [ Links ]

Su, Y. & Kunkel, T. 2019. Beyond brand fit: the influence of brand contribution on the relationship between services brand alliances and their parent brands. Journal of Services Marketing, 30(2):252-275. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-02-2018-0052]. [ Links ]

Sultan, P. & Wong, H.Y. 2019. How service quality affects university brand performance, university brand image and behavioural intention: the mediating effects of satisfaction and trust and moderating roles of gender and study mode. Journal of Brand Management, 26(3):332-347. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0131-3]. [ Links ]