Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.19 no.2 Meyerton 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcman1008.166

ARTICLES

A review of the determinants of tourism destination competitiveness

Tanya Rheeders

College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Email: vds.tanya@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2376-2182

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: Worldwide, the tourism sector's competitiveness is used as a measure of its performance, which is regarded as productivity, a driver of economic growth, and economic development (Webster & Ivanov, 2013; Rizzi & Graziano, 2017). Therefore, a region must focus on the tourism sector's potential to provide the region with development and growth opportunities. Various determinants could influence a tourism destination's competitiveness. It is important to note which determinants have the most significant impact on growth and development

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: An examination into the concepts of tourism destination competitiveness, the determinants, and existing models of tourism destination competitiveness will provide the most important determinants required to ensure the development and success of a tourism destination. After a literature review identifying possible determinants, a pre-test was conducted where industry and academic experts were consulted to rank the importance of various determinants in warranting the success of a destination

FINDINGS: The five highest ranking determinats in the three identified dimensions are; (i) Natural resources and strategic location, (ii) safety and security, (iii) accommodation facilities, (iv) historical and cultural resources, and (v) transportation facilities. These five determinants should be considered when a tourism destination formulate development strategies relating to a specific region

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: In order to guide the identification of well-informed strategic recommendations for relevant stakeholders, there is a need to a regional and empirical measurement of tourism destination competitiveness

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: After the development of the tourism destination competitiveness measurement instrument, stakeholders would be able to

JEL CLASSIFICATION: L83, Z32

Keywords: Determinants; Literature review; Tourism destination competitiveness, Tourism models.

1. INTRODUCTION

A tourism destination's competitiveness plays a crucial role in a country's resilience and development, argue Andrades-Caldito, Sanchez-Rivero, and Pulido-Fernandez (2013). Economic growth and development require competitiveness, especially in the current economic environment. In the study of Alves et al., (2018), he highlights that the "state-of-the-art" literature research and bibliometric techniques have not been extensively applied to the concept of competitiveness in the tourism sector on regional and business levels. As a result, there is a need to study the topic of tourism competitiveness. The fact that there is a lack of knowledge in this field of study concerning the links between economic, tourism, and social variables is highlighted by Dana et al. (2014). To gain a comprehensive understanding of a tourism destination's competitiveness, an in-depth investigation in this field is necessary (Delbari et al., 2015; Ferreira et al., 2016).

Researchers gathered insights into the physical environment that influences the attraction of potential tourists as a selected tourist destination in the last decade of the twentieth century. During this period, researchers focused on providing models that explain this relationship. In 1990, Porter was one of the first authors in competitiveness, publishing his model of competitiveness. However, this model does not apply to tourism destination competitiveness, as this model is very generic with the focus on the influences that primary production factors have on the competitiveness. In addition, Porter (1990) postulates that these factors are subjected to external and/or secondary factors such as local authorities and unanticipated events.

Thereafter, the need for a sector-specific (tourism) model of competitiveness was met by Ritchie and Crouch in 1993 and 1999 with conceptual models of tourism destination competitiveness, the latter including the workings of both the micro-and macro-environment within a tourism destination. Kim (2001) followed with the top four determinants of tourism destination competitiveness being (i) economic groups, (ii) tourism guidelines, (iii) tourism infrastructure and (iv) tourism demand. However, Kim's (2001) model lacks an effective measure of competitiveness in the interlinked tourism sector. As a result, thereof, Dwyer and Kim (2003) improved on the previous works by developing a model to include (i) inherited, created, and complementary resources, (ii) management by government and (iii) social prosperity.

The primary focus of this research is to examine the determinants that have an influences on a tourism destination competitiveness in regions, considering the discussions and reasons above. This research used a descriptive approach of research to assess regional determinants of tourist destination competitiveness. This will serve as a foundation for developing a thorough measurement instrument to determine a tourism destination's level of development or competitiveness compared to other places. This measurement instrument can be used to evaluate a specific tourist destination to ascertain which areas or determinants need to be improved for a regional tourism destination to become more competitive.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

An investigation into the determining factors known as determinants of regional competitiveness is required to improve a region's tourism competitiveness. The investigation into these drivers and models that predicts and explain tourism destination competitiveness will begin with reviewing the literature on tourism development and competitiveness. Tourism development, competitiveness, and the factors and models of tourism destination competitiveness are all theoretical issues that apply to this subject. Complexity and being interlaced are the characteristics that explain are in the tourism sector, which signifies the need for an explanation of the forms, activities and linkages found in the tourism sector to foster an understanding thereof. The importance of a literature review is noted by Hofstee (2015) by stating that theoretical discussions set out to explain the reason behind "why something is as it is and does as it does".

2.1. Conceptualising tourism

The review of available literature reveals that numerous definitions have been used to explain tourism throughout history. However, these meanings vary, based on the researcher, organisation, and time period. As a result, there is no explicit agreement on what constitutes tourism. Williams and Shaw (1988) define tourism as "a particularly arid pursuit'. To better comprehend the flow and progress of the development of a tourism definition, the definitions offered were articulated chronologically. In 1905, German scientists Guyer and Feuler published one of the first definitions of tourism (Roy & Roy, 2015). They argue that tourism is driven by people's growing need for a change of scenery, an appreciation of nature, and the expectation that they would benefit from it. Tourism is a venture that aids countries and communities in their interactions with one another, leading to advancements in trade and sector through improving communication and transportation procedures (Karalkova, 2016). As a result, this definition was the first in the evolution of tourism definitions at the turn of the nineteenth century.

In the twenty-first century, tourism definitions have evolved based on the activities and periods encountered, especially in a specific economic time period. In addition, the UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization) (2008) defined tourism as "the activities of persons travelling and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes". Three characteristics are covered in this definition. It must, first and foremost, include outside transportation (travel), second, have a reason for travelling, and third, have the maximum number of days stayed (Roy & Roy, 2015).

Because some definitions merely indicate a maximum stay period, it is possible to conclude that tourism has no minimum stay length and does not prohibit activities associated with an overnight stay. According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (2008), the tourism sector is a "cluster of production unites in several industries that produce consumable goods and services requested by visitors." Despite significant setbacks at the turn of the century, the tourist sector has grown to become one of the most critical activities, according to Lew et al. (2014). It has raised the public understanding of the global economy. According to Ketels (2016), there is no such thing as a right or inaccurate definition of tourism; rather, the definition would be less or more applicable and valuable.

2.2. Travel and tourism

In some cases, the phrases travel and tourism are used interchangeably or consecutively. While these terms are frequently confused with the same meaning, their definitions are not the same. According to significant research, tourism is defined as the activities conducted by persons (tourists) for the motives of tourism, which include travel, staying, and experiencing a specific geographical area. The term travel is defined as "a specialised activity of humans (travellers) linked to only tourist transportation (arrivals) and paid to lodge" (WTTC (World Travel and Tourism Council), 2019), omitting other activities such as food, drink, and entertainment. The action of transporting tourists between geographical locations is known as travel (UNWTO, 2008).

2.3. Tourism activities

Although tourism was first recognised in the early 1900s, it is a relatively recent study topic compared to other fields of science, achieving popularity in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The primary academic fields that correspond with tourist study, according to Jafari and Ritchie (1981), are economics, sociology, psychology, geography, and anthropology. Tourism is now a highly interconnected sector that spans economics, law, marketing, management, finance, hospitality, architecture, transportation, leisure, ecology, geography, urban and regional planning, political studies, sociology, cultural studies, anthropology, and psychology studies. This also serves as a foundation for identifying different sorts of tourism. According to Phillip, Hunter, and Blackstock (2010), to properly comprehend a phenomenon, foundational qualities must be articulated to improve knowledge.

2.4. Tourism development theories

2.4.1. The Butler's tourism area life cycle

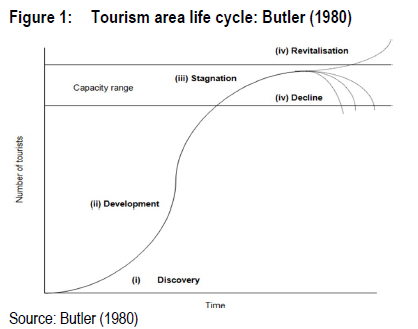

Butler's TALC (tourism area life cycle) model is the departing point for other research and studies which aim to predict and explain the relationship between the tourism sector and economic activities. This model evolved from the product existence cycle model, which believes that a tourism "area" will circulate through various stages (McKercher & Wong, 2020). The TALC model explains the evolution of a tourism location destination. Butler (1980) states that the stages through which a tourism area from beginning to the end is explained by an S-curve is signified in Figure 1.

The TALC takes into account the manner wherein a tourism destination is (i) birthed and discovered, (ii) growing or developing, (iii) attaining maturity, stagnation and (iv) reached a restart or revitalisation stages. Butler (1980) therefore have confidence that the number of travellers that first visit a tourism area (vacation spot) can be noticeably small in the beginning. However, with advertisement and marketing initiatives as well as improved facilities will result in a boom in vacationer arrivals- tourism development or competitiveness. As the capacity of a tourism destination declines, the number of arrivals is required to decrease. The limitation incapacity could be depended on environmental, physical, and social aspects. The decrease in capacity and the increase in popularity of other tourism area will lead to the decline of the tourism area. Rizzi and Graziano (2017) said that an area's capital and critical structures and infrastructures are the primary influence in defining the success of a tourism area. According to Kusumah and Nurazizah (2016), this principle is outdated and no longer correctly explains a TALC. The limitation incapacity could be depended on environmental, physical, and social aspects. The decrease in capacity and the elevation in popularity of other tourism area will direct to the deterioration of the tourism area.

2.4.2. Tourism-led growth hypothesis

The tourism-led growth hypothesis was first introduced in the early 2000s by both authors Balaguer and Cantavella-Jorda (2002). Nevertheless, interest in the relationship between economic progress and the tourism sector development stemmed from the export-growth hypothesis. The export-growth hypothesis explained that economic growth would occur when labour and capital are utilised on the outcome of export pursuits (Mitra, 2019). This theory can also apply to the tourism sector. Balsalobre-Lorente et al. (2020) state that the TLGH explain that developments in the tourism sector would lead to the progress of a region's economy. Brida et al. (2016) also postulate that the linkage between the tourism sector and economic growth in the long and short-run could be tested by the TLGH through Granger causality. The Granger causality tests whether or not a statistical series can explain another series' changes. Lin et al. (2019) indicated that the hypothesis explained the unidirectional connection between these two ideas. This provided a requirement for a test of the economy's influence on the tourism sector. The economy-driven tourism growth hypothesis was introduced in the case of economic growth and the tourism sector. Aratuo, et al. (2019) defined the economy-driven tourism growth likelihood as the situation where the growth in a country's economy would lead to the development of its tourism sector. A third likelihood would be that a bidirectional linkage does exist between tourism development and economic growth. A fourth likelihood is that there is no relation exists between economic growth and tourism development.

2.5. The effects of various determinants on tourism destination competitiveness

2.5.1. Natural, cultural, and historical resources

Natural resources may provide a significant advantage to a tourism destination. Those without natural resources may have difficulty competing with those who do. Ritchie and Crouch (1993) developed a model to explain tourism destination competitiveness, one of the first models. Appropriate use of resources and effective management make it possible for natural and cultural resources to increase the level of competitiveness of a tourism destination (Lo et al., 2017). The development of tourism destinations can be improved when the natural resources, visual appeal, and marketing are successfully coordinated (Crouch & Ritchie, 1999; Poon, 1993; Yoon et al., 2001). According to Andrades and Dimanche (2017), a tourist destination is more likely to succeed in encouraging tourism spending when they are known for beautiful sceneries and interesting sites. A study by Csapó et al. (2016) found that in three of the four regions investigated, the essential determinants leading to the development of a tourism destination were the quality and prevalence of tourism attractions.

Crouch and Ritchie (1999) believed that tourism development could be greatly enhanced by strengthening regional and local traditions. By Crouch and Ritchie's beliefs, Dwyer, and Kim (2003) postulate that cultural and historical resources are likewise important as the most popular determinants, natural resources to driver the competitiveness of destinations. The study by Stetic et al. (2014) provided results that a large quantity of historical and cultural resources is the second most significant determinant of a thriving tourism destination, with a significance value of 4.29 out of five.

2.5.2. Entrepreneurship

Jaafar et al. (2015) argued that the tourism sector could be a good start for a small business due to the minimal start-up capital required. The positive consequence of tourism development is the creation of employment opportunities (Crouch & Ritchie, 1999). However, quality labour is needed to ensure that tourism destinations progress successfully. Jaafar et al. (2015) explored the limits and elements of small tourism businesses that have a negative effect on these businesses. The following three determinants are listed in order the utmost limiting element, one being rarely limiting and five extremely limiting, namely (i) fluctuations in climate and season with 3.68 out of five, (ii) unavailability of trends and opportunity knowledge in tourism in second at 3.42 out of five and (iii) lack of marketing abilities with a rating of 3.39 out of five.

2.5.3. Tourism destination location

The location of a tourist destination is an essential factor in the destination selection process for tourists. Csapó et al. (2016) stated that the concept of the strategic location of a tourism destination has an important influence on its success. iatu et al. (2018) state that the success of a tourism destination will be affected by the locality of tourism destinations to heritage sites and other activities and facilities. A World Heritage site of tourism facilities will positively influence tourism development if the tourism sector is nearby.

2.5.4. Infrastructure facilities

The successful management of infrastructure that facilitates tourism activities (Jovanovic & Ivana, 2016) contributes to creating opportunities for economic diversification (Adeleke et al., 2008). In the study of Csapô et al. (2016), the effectiveness of structures and infrastructure contributed to improving the images of a tourism destination. These attractions are enhanced due to the five evaluation factors: authenticity, uniqueness, marketing, appearance, and attendance. Dwyer and Kim (2003) state that infrastructure includes accommodation, catering, attraction sites, entertainment, and transportation services.

The quality and accessibility of health and education facilities are essential to the progress of a tourism destination and its total success. The World Economic Forum identified health and hygiene as determinants contributing to the success of a tourism destination. Education facilities, more especially tertiary education, are required to improve a tourism destination's economy (Naidoo, 2016). Hanefeld et al. (2016) examined Thailand's medical tourism, which has since the early 2000s, been recognised as one of the most popular medical tourism destinations. The study showed that 167 000 visitors travelled to Thailand for medical tourism assistance, most low to medium-income countries, since 2010. The income and consumption produced from this medical tourism activity have positively influenced the development of the tourism sector in a destination.

According to Charles and Zegarra (2014), the group named infrastructures include four components that should be noted for their influence on the success of a tourism destination being communication, transportation, road, and energy systems. Buhalis and Amaranggana (2013) state that the ICT (information and communication technology) sector could provide the tourism sector with competent processes to aid tourism businesses in their general day-to-day responsibilities. Tussyadiah and Pesonen (2016) postulate that social systems online facilitate the use of resources and infrastructure.

2.5.5. Authorities and government organisations

Meyer and Meyer (2015) state that regional authorities are responsible for securing the development of citizens' growth. Previously, regional governments and authorities had a limited obligation to ensure the achievement of a tourism destination. However, recently, regional governments and authorities have recognised their obligation to actively aid destinations in tourism development. Government's commitment to tourism development, According to Kubickova and Hengyun (2017), first, regional governments are essential to guarantee tourism sector development. Secondly, regional governments and authorities cannot succeed in intervening in the tourism sector and could dissuade tourism development through unwarranted controls. Chen et al. (2016) postulate that regional governments and authorities have lately been taking a serious note of the significance of the tourism sector.

2.5.6. Security and safety

Commonly, a traveler should uncover the safety of and how secure they will be during their travels before visiting a tourism destination. Safety and security are based on various factors, but the most significant is physical safety. Bulatovic and Rajovic (2015) studied the components that impacts the competitiveness of businesses in north-eastern Montenegro from July 2012 to August 2013. The results designate that safety and security are ordered the fourth most significant factor influencing tourism destination competitiveness in the category "qualifying and amplifying" determinants with a significance value of 3.43 out of five. Wars, xenophobia, murders, and vicious crimes amplify the hesitance of tourists (especially international tourists) to visit a tourism destination. If travelers perceive a tourism destination as dangerous, which is one of the main prerequisites, it will decrease the number of entries and directly affect consumption.

2.6. Models of tourism destination competitiveness

Characterised by growing development, the tourism sector is becoming essential for the success of a nation as the sector acts as a principal economic sector (Webster & Ivanov, 2014; Karalkova, 2016; Idrus, 2020). Competitiveness is one of the primary objectives that a nation, especially those with poor development levels, would desire to accomplish as this will amend their current unfortunate economic position (Herciu, 2013). Being an interlinked sector, a tourism destination's development is impacted by its competitiveness (Karalkova, 2016). Consequently, tourism destination competitiveness can also be a gauge of its functioning as a tourism destination. Thus, it was valuable to examine the competitiveness of a tourism destination as it could provide helpful information concerning the state of tourism within a region.

2.6.1. Crouch and Ritchie (1999)

After the Richie and Crouch (1993) model, Crouch and Ritchie (1999) developed an upgraded model portraying the competitiveness of a tourism destination. The necessity for an augmented model is related to the critique that the previous model lacks. This model aims to examine the competitiveness of a tourism destination. The models was developed by Crouch and Ritchie in 1999, the authors directed a qualitative study using open-ended questionnaire questions. The conceptual representation of Crouch and Ritchie's (1999) model examining the connection between tourism and quality of life and the concept of tourism destinations' competitiveness's importance is shown in Figure 2.

According to Crouch and Ritchie (1999), the following views represent the conceptual model of a competitive tourism destination.

• Qualifying determinants or situational conditions are the components whose goal is to recognise the degree, restrictions, and potential of a tourism destination's competitiveness. Three factors that influence destination competitiveness within the category of qualifying determinants include (i) the location, influencing the potential of a destination to successfully attract visitors. The location cannot be altered; however, a destination's distance (location) to other important destinations, as other markets and destinations develop nearby. Destinations are dependent on the competition and complementing essence to another destination; (ii) the safety and security given by a tourism destination are pivotal components as tourists are highly concerned in the frequency of crimes, devastating natural incidents and medical facilities. Thus, one should consider the overall safety and security of tourists. Expenditure is a significant deciding factor in the tourism sector. Therefore, the price of tourism-related goods and services within a tourism destination is important for encouraging tourist arrivals. The cost includes transport, accommodation, cost of living and the exchange rate.

• Destination policy, planning, and development include systems that ensure a tourism destination reaches development. For a tourism destination to reach successful development, policies should be developed and effectively executed in addition to plan methods to create tourism destination competitiveness. The responsibility for the development of the tourism destination should be clearly stated; however, it should be a combination of community members and government authorities.

• Destination management is essential for a destination to be adequately managed by concentrating on the primary resources and attractors, improving the condition of supporting factors and resources and regulating the qualifying determinants. Management of a tourism destination takes place through (i) promoting, (ii) service, (iii) information and (iv) resource stewardship.

• Core resources and attractors are the primary resources of a tourism destination that draw tourists in and are explained as the core resources and attractors. Moreover, these factors are the main thinking behind attracting tourist arrivals, bringing about tourism expenditure and development of tourism. The primary resources are: (i) physiography, (ii) culture and history, (iii) market ties, (iv) range of activities, (v) special events and (vi) tourism superstructure. Dwyer and Kim (2003) postulate that the general appeal that a destination offers tourists is one of the most crucial components that influence success.

• Supporting factors and resources: In addition to core resources, the supporting resources of a tourism destination are there to aid the core resources in attracting visitors and, as such, competitiveness. It offers a foundation upon which the tourism sector could be built, consisting of transport, water, sanitation, communication networks and facilities related to community services provided by a financial organisation, capital and human resources. Companies and entrepreneurship provide a means by which a destination could strive for improved competitiveness, and it is crucial to note how accessible the tourism destination is, for it has a bearing on its success.

• The competitive microenvironment includes the tourism participants, destination, and

markets making up the tourism destination. The tourism participants include travel agents, facilities, and other tourism suppliers. The direct environment forms the tourism sector, which must adapt to compete profitably.

• Global, macro-environment: External international factors have an impact the tourism sector and should therefore be considered when constructing possible development strategies. As the global environment brings about additional factors into the mix, it could present complications, deterrents, and issues that a tourism destination must adapt to and overcome. On the other hand, these factors could provide exciting opportunities and possibilities for market research.

2.6.2. Dwyer and Kim (2003)

Following Ritchie and Crouch's (1993) and Crouch and Ritchie (1999) and models, Dwyer and Kim (2003) also developed an integrated model explaining the concepts of tourism destination competitiveness. According to Vojinovic and Zivkovic (2018), Dwyer and Kim (2003) developed this model as they critiqued Crouch and Ritchie's work to not? examine the demand only including the supply viewpoint. Dwyer and Kim (2003) supported this model, including the "main elements of competitiveness". Dwyer and Kim (2003) made a case for the requirement for another model as previously developed models are not "satisfactory" due to a lack of comprehensiveness. This model comprises the different elements on a national and company level that determines competitiveness. Dwyer and Kim's (2003) model of tourism destination competitiveness is embodied in Figure 3.

• Within the category "resources", (i) endowed resources could be defined as the resources that naturally accompany a tourism destination. That consists of the scenery, climate, historical and cultural resources; and (ii) the man-made resources can be classified as infrastructure, activities and events hosted by the tourism destination, where "supporting resources" can be found including market system s, infrastructure, service provided and the attainability of the tourism destination.

• Situational conditions originate from the external or macro-environment. It encompasses the social, political, economic, institutional, demographic, ecological and cultural aspects that establish the matter in which a business and destination conduct business. Crouch and Ritchie's (1999) qualifying and amplifying category are in accordance with Dwyer and Kim's (2003) model.

• According to Crouch and Ritchie (1999), destination management is the component that help manage a tourism destination to attract resources and factors. Actions relating to destination management, including marketing, planning, and development of components. This category relates to that of Crouch and Ritchie. However, destination management by Dwyer and Kim (2003) distinguishes between public and private sector management.

• In the category "demand conditions", three additional components could influence the development of a tourism destination. These components are; (i) the consciousness of the destination for tourism participants can be produced through marketing activities, (ii) the observation that an existing or potential tourist can have a specific destination influences consumer behaviour, and (iii) the preferences that a tourist has in terms of destination requirements have an impact on the possibility of a visit.

2.6.3. Truong et al. (2018)

Truong et al. (2018) meant to (i) generate a standardised method of recognising the traditional capabilities of supply vs demand viewpoints of tourism destinations and (ii) examine and discover the connection among the global and nationwide determinants or "attributes" and the contentedness of tourists. This examination additionally contributed to the present studies through the following. Firstly, theoretically, it expands the understanding of tourism destinations' distinctiveness. The article suggests an identification scale that assists tourism destinations in differentiating themselves from others. It looks at the distinctive factors giving information on how these factors influence the satisfaction of a visitor. Therefore, tourism destination's managers could utilise this to recognize and highlight the specific factors to formulate marketing approaches better. The study of Truong et al. (2018) entails the qualitative and quantitative study technique to investigate the destination distinctiveness of the Central Highlands, Dalat, Vietnam. The reasoning behind selecting this methodology is to generate more dependable results than the usual method of consulting expert opinions. According to Truong et al. (2018), a tourist destination in the mountains were previously known as a good tourism destination that would content the needs of a tourists.

3. METHODOLOGY AND RESEARCH DESIGN

This study aims to conduct literature and empirical reviews of the determinants of regional tourism destination competitiveness. In doing so, the determinants and models were analysed, and an empirical study was completed. The research paradigm on which this study is based on an interpretive approach as it sets out to discover and understand the workings of tourism destination competitiveness by identifying the determinants thereof. The study followed a mixed method approach.

3.1. Identification of the determinants

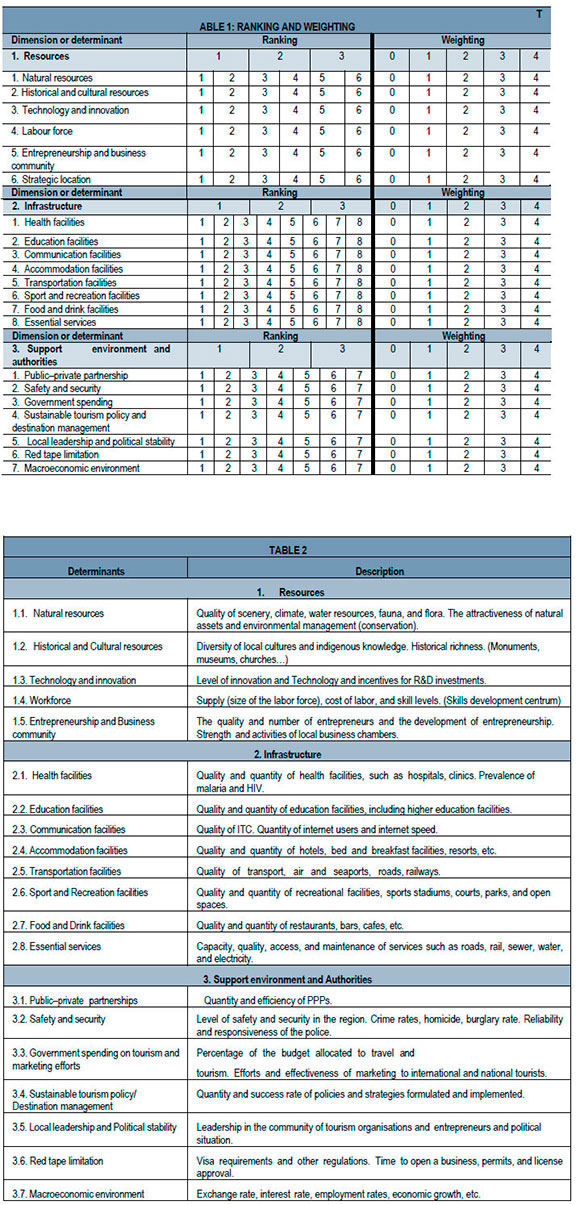

The determinants identified were categorised into three groups in terms of their relevance.

The groups are (1) resources, (2) infrastructure, and (3) support environment and authorities.

3.2. Pre-testing survey

Following the identification of the determinants through a review of the available literature, which was important to determine the importance of each selected determinant. The goal of the pre-testing was to finalise the determinant selection by identifying the determinants that have the highest significance on tourism destination competitiveness. The rationale behind the pre-testing was to collect knowledge of subject-matter and sector experts to gather information on the importance and priority of the various selected determinants. This was essential to differentiate between relevant, important and the redundant and unnecessary determinants that could have been mentioned in the literature review, but do not agree with reality in the tourism sector in the current times.

National and international sector and subject experts conducted the pre-testing. For each determinant and dimension of tourism destination competitiveness or development, these experts were asked to give the importance weight value and a priority value. During pretesting, additional inputs were requested regarding the choice of relevant determinants. The subject and sector experts need to give the priority and importance weighting of each dimension and determinant because not all determinants or dimensions of tourism destination competitiveness hold equal weight in determining destination competitiveness. Microsoft Excel was used to facilitate simple calculations using formulas. Hashim et al. (2019) propose a method for analysing data by pre-testing them with expert opinions.

3.3. Sample frame, size and method

Participants in the pre-test included subject and sector experts from the fields of economic development and tourism and the tourism sector. According to Hinton et al. (2014), a participant is recognized as an individual who is involved in a study as a "subject'. They are located nationally (South Africa) and internationally. Most of the participants are active participants in education and research in tourism and/or economics studies. The reason for the use of these participants is that they are perceived to have in-depth knowledge of the workings of tourism and connected industries. They had a background in the functioning of the economy. They could provide an insight into the important criteria for competitiveness in the region and the tourism sector as individual factors. Integrating and redefining these criteria created the measuring instrument. Therefore, both categories provided appropriate feedback and inputs to weigh the significance and importance of these dimensions and individual criteria. There were 37 individuals selected as respondents based on their knowledge of tourism and economics. The sample method and quantity depend on research experts in economics and tourism. Therefore, the objective sampling method was chosen because it required the use of subject-specific subject and sector experts.

3.4. Data collection and analysis

Data were collected using correspondence, and subjects were contacted by email. The response rate to the pre-test was 31 out of 37 respondents, resulting in a response rate of 83.78 per cent. This is an adequate response rate from the total of 37 respondents. The data were analysed by calculating the average value of each determinant and group. Quality values for ratings and weights, as well as qualitative feedback on changes that may be required to improve the measuring instrument, were received.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: DETERMINANTS OF TOURISM DEVELOPMENT

4.1. Determinants of tourism development identified

The tourism sector provides a region with various possibilities for recreation and relaxation (Chen et al., 2016; Ohe et al., 2017). Especially on a regional scale, it is important to identify the factors that determine a tourism destination's development. Advancing the determinant or factor of a destination on a regional level proves easier than improving the entire destination's competitiveness without recognising the areas that require development (based on the determinants). In addition, Qu et al. (2011) believe that the only factors within a tourism destination should be highlighted when formulating plans for its development.

4.2. Priority results of groups and determinants of tourism destination competitiveness

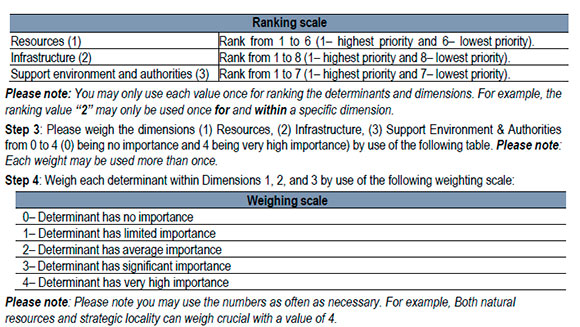

The distinction between the importance of each of the identified determinants of tourism destination competitiveness was requested from the participants. The instructions given to the participants to rank each determinant in terms of their importance to achieving tourism destination competitiveness were given as follows:

• Determinants in group (1) Resources- Rank from 1 to 6 (1- highest priority and 6- lowest priority)

• Determinants in group (2) Infrastructure- Rank 1 to 8 (1- highest priority and 8- lowest priority)

• Determinants in group (3) Support Environment and Authorities- Rank 1 to 7 (1- highest priority and 7- lowest priority).

It should be noted that the values of the dimensions are not the average values of the determinants, but the average values of the specific dimensions given by the dimensions out of three. Table 1 gives the average priority values of the dimensions and determinates gathered from the pre-testing phase by sector and subject experts.

4.1.1. Priority of the groups of tourism destination competitiveness

The average priority score for the resource dimension is 1.74 out of three. The infrastructure dimension has the lowest priority, with an average of 1.17 for the three dimensions. The average priority for the funding environment and authorities is 2.55 out of 3. Therefore, the priority of the dimensions was 1-Infrastructure, 2-Resources, 3-Support Environment and authorities. Jovanovic and Ivana (2016) noted that tourism infrastructure is the basis of tourism development. Strategies can be developed by use of the priority values as a benchmark for goal setting and strategy development. The support environment and authorities were given the lowest priority of the three aspects. This ranking encourages community members and local tourism-related companies to participate in the agenda.

4.1.2. Priority of the determinants of tourism destination competitiveness

For the resources group, the determinants, namely natural resources, and strategic location, have an average priority score of 1.81 out of the four determinants. Historical and cultural resources have an average of 3.42 priorities among the four determinants of the resource dimension. A study by Stetic et al. (2014) reached similar conclusions, pointing to a cultural and historical wealth importance score of 4.26 out of five. For Technology, innovation, and communication, the average priority of the four determinants is given a value of 3.81. Entrepreneurship, business community and workforce are given a 4.33 value for the average priority between the four determinants. As such, the priority value of the determinants in the resources dimension is ranked as the following; 1- natural resources and strategic location, 2- entrepreneurship, the business community and workforce, 3- historical and cultural resources and 4- Technology, innovation and communication. The natural resources and strategic location have a significant influence on tourism competitiveness. Therefore, natural resources and strategic location are the most crucial in the resources dimension.

The model of Ritchie and Crouch (1993) come to an agreement with this in stating that resources are one of the four most important determinants that encourage tourism destination competitiveness. Lo et al. (2017) also believe that natural resources are very important as natural and cultural resources attract more tourists to their destinations. Entrepreneurship, the business community, and the workforce are the second priority in resources. Jaafar et al. (2015) state that entrepreneurship is a significant benefit of the tourism sector because it is easy to start a business and does not require a large amount of capital to open a tourism-related start-up.

A group infrastructure with an average priority value of 1.71 gave the following value to the factor of dimension. Health and educational institutions were evaluated by the average priority value of 5.17 from the six decision factors in the dimension infrastructure. On average, 3.16, accommodation is done. Transport system 3.58 was given as an average priority. Low priority 5.74 was awarded to sports and recreation facilities. The focus on gastronomy was rated at an average of 4.32. Stetic et al. (2014) It was found that restaurants are given an important score of 2.97 out of 5 because they make an important contribution to the success of tourist destinations. The basic services of tourist destinations have an average priority of 3.97 out of the six determinants in terms of infrastructure. Therefore, the determinant priority values in the infrastructure dimension are 1-Accommodation, 2-Transportation, 3-Basic Services, 4-Catering, 5-Health and Education, 6-Sports and Recreational Facilities and. The accommodation is not surprising if the property is the most important of the tourist goal priority. Excellent accommodation is required to promote one-night sightseeing. If tourists spend the night at the tourist goal, they will encourage more about goods and services in tourist destinations.

In the environment and authorities' group, the average priority value was 2.55, and the determinants of the dimension were given the following values: The average priority score for public-private partnerships is 5.35. The safety priority of tourist destinations was rated as 2. Government spending and efforts on tourism and marketing efforts and sustainable tourism policies, and destination management are the second-lowest precedents for tourism destinations' competitiveness, with an average priority score of 4. In a related study, Jaafar et al. (2015) examine the limiting effects of certain factors on the competitiveness of tourist destinations. The results show that the lack of marketing skills is very restrictive to tourism destination competitiveness, with a value of 3.42 out of five. This indicates that proper marketing efforts will have a positive impact on the competitiveness of a tourism destination. According to Das and Dirienzo (2010), there is a high positive association of 0.78 between tourism destination competitiveness and the decrease in corruption levels. Indicating that the reduction in corruption could lead to an improvement in the competitiveness of a tourism destination. Local leadership and political stability have 3.77 as the average priority-the average priority value of 3.70 due to the determinant rep tape. The macro-economic environment of a tourism destination, as a determinant, was given an overall average value of 4.58 put of the entire six determinants in the infrastructure dimension. Therefore, the priority value of the determinants in the support environment and authorities' dimension are; 1- safety and security, 2- red tape, 3- local leadership and political stability, 4- government spending and efforts and 5- private-public partnerships 6- macro-economic environment. This study identified crucial determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in the top 5 in Table 2.

The pre-testing identified the ten most important determinants according to their priority and importance in assisting tourism destination competitiveness. The following determinates in no order are:

The use of accommodation facilities takes the role of the visitor's purpose because of the visit to a tourist destination. Thus, it can be the identifying component or delivered component in influencing the visit or stay of a visitor to a visitor's vacation spot. According to Yeh (2020), the information available about a tourism destination's accommodation facilities plays a crucial role in the selection method. Online systems have established precious for accommodation centres to utilise. Dolnicar (2018) recommends peer-to-peer lodging systems which encompass a whole lot of lodging centres in addition to several capacity purchasers. An example of this is Airbnb which permits individuals to rent accommodation that they own to vacationers. A tourism vacation spot ought to collect a suitable variety of accommodation centres that might be excessively first-rate to make precise competition.

Entrepreneurship, the business community, and the workforce. Yeh (2020) states that businesses related to the tourism sector should share information about their services. Dissemination of information about activities in the tourist destination is also important for these businesses. Businesses and related stakeholders should work together to enhance the development of the tourist destination, such as the development of new tourism activities through the cultivation of entrepreneurs (Dimitrov et al., 2019) who need to identify the needs of potential tourists. Developing a good business community helps increase investment opportunities (Tien et al., 2019). Kryukova and Ketagurova (2020) will financially support businesses to encourage business development incentives through tax breaks or tax holidays. Funds earned from tax breaks can be reinvested in business development.

Essential Services are the necessary offerings to make sure the progress of a tourist destination, such as the right water and power services to ensure the pleasure of no longer most effective system participants but also travellers (Tien et al., 2019) waste disposal and transportation facilities. Zones ought to ensure the capability to provide offerings now not most effective to system contributors but additionally to ability travellers. Exceeding the capability of a region might also result in the termination of services guiding unhappy community contributors and travellers. Providing these basic offerings is very vital for agencies, and they require vital offerings to run their operations efficaciously. Basic services to be supplied using local government consist of waste disposal, uninterrupted delivery of electricity and water, and infrastructure protection.

Food and drink catering facilities: The number of high-quality catering facilities is crucial for the success of a tourist destination. Therefore, having a variety of food and beverage facilities such as bars, cafes, restaurants, and takeaways will be beneficial in attracting a variety of tourists.

Historical and cultural resources can be utilised to meet the needs of tourists (Tien et al., 2019). If a tourist destination has not yet been used as a cultural or historical resource attraction, it should contemplate recognising possible attraction activities. However, it must be acknowledged that not all tourist destinations have historical and cultural resources. It is important to develop knowledge of these resources in a tourist destination with historical and cultural resources. Facilities inclusive of monuments, museums, churches, and houses of historical figures should be protected for their historical or cultural value.

The natural resources and strategic location of a tourist destination is unchangeable and have a significant impact on the success of the destination. The location should provide tourism activities, markets, and resources, viz. logically, a tourism destination could not move. Although, according to Nur et al. (2019), enhancements in tourism destinations could improve its ability. Tien et al. (2019) state that tourism destinations could add value to natural resources. The prevalence of natural resources is not something that could be created but should be maintained and protected.

Regional leadership and political stability. Heslinga et al. (2020) believe that stakeholders determine the direction in which a tourist destination develops. The leadership of a community in a region must have clear objectives to work with. Their objectives are to create a socio-economic environment in which all can function peacefully and focus on the development of the tourism sector. Tien et al. (2019) says the safety and security of a tourism destination are necessary to have an ordered and stable tourism destination. Law enforcement bodies should be reliable and responsive in the case of emergencies and when crimes occur. Therefore, law enforcement and local communities should be working together in developing and implementing strategies to provide aid successfully. According to Ushakov et al. (2018), the safety and security within a tourism destination are a "cornerstone" of creating a tourism destination's image. Suppose a tourism vacation spot is looked at as if it would be risky. In that case, it would result in a decline in tourism arrivals which immediately lowers tourism spending utilised to spend money on tourism improvement projects.

Transportation facilities are an essential function in achieving a successful tourism destination as it is the linkage between tourists and the selected destination. Transportation facilities, "roads, railways, air or seaports", should be designed to ensure the comfort of visitors. An extensive range of transportation possibilities must also be made available to tourists. With the fourth industrial revolution starting, Technology, innovation, and communication played a crucial part in the workings of a region. Smart tourism destinations use Technology to their advantage in tourism destination development. It could be a valuable tool to market to potential tourists. According to Chang (2017), mobile marketing is one of the most crucial resources in this day and age as lots of tourists make use of mobile devices in search of potential tourism destinations. Tourism destinations should strive to produce new, innovative ideas to attract visitation.

4.1.1 Adjustment and refinement of the measurement instrument

The following were the recommendations and comments provided by the respondents (industry and subject experts):

• Questionnaires should be available online and not only in Microsoft Word. This protects respondents' identity and simplifies completing the questionnaires.

• Reduce of the number of determinants to ensure easy questionnaire completion by respondents. Therefore, the two determinants, "government spending on tourism and marketing efforts" and "sustainable tourism policies and destination management", were combined as "government spending and efforts".

• In addition, "health and education facilities" were also combined.

• Communication facilities were added under the dimension "resources' with "technology and innovation".

• Relocating the determinant "strategic location" as a factor for the determinant "natural resources' as it is more appropriate.

• As a result, the measurement instrument had 16 determinants within the three dimensions explaining tourism destination competitiveness.

• It should be recognised that the success of a tourism destination is dependent on the demand or needs of a tourist. For example, a tourist could be interested in a secluded and remote area. As such, the strategic location of a tourism destination would be positive if the tourism destination is opposed to a tourism destination that is in the "hustle and bustle" of a region.

5. CONTRIBUTION OF THE STUDY AND FUTURE STUDY

The competitiveness of a tourism destination can be evaluated through either conceptual and/or empirical evidence, the latter being less used. Most models used to measure this are based on the conceptual works of Richie and Crouch (1999) and Dwyer and Kim (2003). Not enough attention has been given to an empirical measure on a specifically a regional level. The primary goal of this study (identifying the determinants of tourism destination competitiveness) therefore provides important evidence that could be used to create an empirical measurement instrument of tourism destination competitiveness on a regional level. In addition to the limited studies conducted on the possibility of an empirical measure, another rationale for identifying determinants on an empirical is due to the simplicity of its understanding and analysis, which enables well-informed strategic recommendations. In tourism research, studies usually concentrate on the manager's viewpoint. However, this study considers the viewpoint of various tourism network participants, namely (i) community members/ tourists, (ii) tourism-related businesses and (iii) government tourism organisations. After considering the determinants of the competitiveness of a tourist destination, a measurement instrument can be developed to analyse the performance and competitiveness, and development of a tourism destination. With this tool, the performance of a tourism destination can be analysed and compared.

6. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

The development of a tourism destination competitiveness measurement will enable organisations and tourism-related businesses to effectively manage a tourism destination. The tourism destination competitiveness model will provide stakeholders with information into the strengths, weaknesses, the available opportunities to expansion and possible threats thereto. Before decisions can be made by the stakeholders, they require information on the status quo of the environment in order to for the strategies and changes to be effective. Therefore, the tourism destination competitiveness measurement will be a helpful tool to establish which of the tourism relevant elements or factors need attention or will be an asset.

7. CONCLUSION

This literature review investigated the determinants and models of tourism destination competitiveness by looking at the tourism development and competitiveness literature. According to Csapó et al. (2016), the best way to improve a tourism destination is to improve local or regional aspects. Many determinants of a destination's competitiveness are derived from the complexity of its tourism offering. As a result, different studies have been conducted to determine how determinants affect the competitiveness of tourism destinations. This is accomplished by investigating and providing empirical evidence of the effect and extent of a specific determinant on tourism destination competitiveness. Tourism development in underdeveloped regions can have major benefits for a country or region, say Adeleke et al. (2008). There is usually a rich diversity of culture and scenery in underdeveloped, lagging, and underperforming regions. (Adeleke et al., 2008; Zvyagintseva et al., 2020). By developing tourism facilities in these regions, the development and progress of these regions could be facilitated, resulting in increased job creation and income (Adeleke et al., 2008). It is also likely to attract tourists, increasing tourism expenditures. The region within tourism destinations that are neglected, or lagging can offer the opportunity for an improved tourism destination (Csapó et al., 2016) if attention is paid to enhancing the relevant aspects. Csapó et al. (2016) maintain that tourism organisations and authorities disregard lagging areas in a tourism destination by focussing on already developed areas.

REFERENCES

Adeleke, B.O., Omitola, A.A. & Olukole, O.T. 2008. Impacts of Xenophobia attacks on tourism. IFE Psychologia: An International Journal, 16(2):136-147. [https://doi.org/10.4314/ifep.v16i3.23782]. [ Links ]

Alves, M.H.D., dos Santos Silva, K.W., Correa, J.S., Texeira, O.M. & de Sousa Junior, P.M. 2018. Levantamento comparativo de propriedades químicas do solo com diferentes culturas em Santa Isabel do Pará, Pará. Cadernos de Agroecologia, 13(2):7-7. [ Links ]

Andrades-Caldito, L., Sánchez-Rivero, M. & Pulido-Fernández, J.I. 2013. Differentiating competitiveness through tourism image assessment: an application to Andalusia (Spain). Journal of Travel Research, 52(1):68-81. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512451135]. [ Links ]

Andrades, L. & Dimanche, F. 2017. Destination competitiveness and tourism development in Russia: Issues and challenges. Tourism Management, 62:360-376. [https://doi.org/10.1016/Ltourman.2017.05.008]. [ Links ]

Aratuo, D.N., Etienne, X.L., Gebremedhin, T. & Fryson, D.M. 2019. Revisiting the tourism, economic growth nexus: evidence from the United States. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(9):3779-3798. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2018-0627]. [ Links ]

Balaguer, J. & Cantavella-Jorda, M. 2002. Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: the Spanish case. Applied economics, 34(7):877-884. [https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840110058923]. [ Links ]

Balsalobre-Lorente, D., Driha, O.M., Bekun, F.V. & Adedoyin, F.F. 2020. The asymmetric impact of air transport on economic growth in Spain: fresh evidence from the tourism-led growth hypothesis. Current Issues in Tourism, 1-17. [https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1720624]. [ Links ]

Buhalis, D., Amaranggana, A. 2013. Smart tourism destinations. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014. In: Xiang, Z., & Tuessyadiah, I., eds. Conference proceedings. Proceedings of the International Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 21-24 January 2013. Springer: Germany. pp.553-564. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03973-240]. [ Links ]

Bulatovic, L. & Rajovic, G. 2015. Business competitive of tourism destination: the case north eastern Montenegro. European Journal of Economic Studies, 11(1):23-38. [https://doi.org/10.13187/es.2015.11.23]. [ Links ]

Butler, R.W. 1980. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. Canadian geographer, 24(1):5-12. [https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x]. [ Links ]

Brida, J.G., Cortes-Jimenez, I. & Pulina, M. 2016. Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? a literature review. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(5):394-430. [https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.868414]. [ Links ]

Chang, P. 2017. The importance performance analysis of Taiwan tourism mobile marketing. Journal of Tourism Management Research, 4(1):12-16. [https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.31.2017.41.12.16]. [ Links ]

Charles, V. & Zegarra, L.F. 2014. Measuring regional competitiveness through data envelopment analysis: a Peruvian case. Expert Systems with Applications, 41 (11):5371-5381. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2014.03.003]. [ Links ]

Chen, C.M, Chen, S.H., Lee, H.T. & Tsai, T.H. 2016. Exploring destination resources and competitiveness: a comparative analysis of tourists' perceptions and satisfaction toward an island of Taiwan. Ocean and Costal Management, 119:58-67. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.09.013]. [ Links ]

Csapó, J., Habil, D., Pintér, R. & Aubert, A. 2016. Chances for tourism development and function change in the rural settlements with brown fields of Hungary. E-review of Tourism Research, 13(2):298-314. [ Links ]

Crouch, I.C. & Ritchie, J.R.B. 1999. Tourism, competitiveness and societal prosperity. Journal of Business Research, 44(3): 137-152. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00196-3]. [ Links ]

Das, J. & Dirienzo, C. 2010. Tourism competitiveness and corruption: a cross-country analysis. Tourism Economics, 16(3):477-492. [https://doi.org/10.5367/000000010792278392]. [ Links ]

Dana, L.P., Gurau, C. & Lasch, F. 2014. Entrepreneurship, tourism and regional development: a tale of two villages. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 26(3/4):357-374. [https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2014.918182]. [ Links ]

Delbari, S.A., Ng, S.I., Aziz, Y.A. & Ho, J.A. 2015. Measuring the influence and impact of competitiveness research: a web of science approach. Scientometrics, 105(2):773-788. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1731-2]. [ Links ]

Dolnicar, S. 2018. Peer-to-Peer accommodation networks: pushing the boundaries. 1st ed. Oxford: Goodfellow. [https://doi.org/10.23912/9781911396512-3454]. [ Links ]

Dimitrov, N, Petrevska, B & Terzic, A. 2019. Recommendations for tourism development of rural areas in North Macedonia. Conference proceedings. International scientific symposium: new trends in geography, October 3- 4. Republic of North Macedonia. pp. 307-316. [https://doi.org/10.37658/procgeo19307d]. [ Links ]

Dwyer, L. & Kim, C. 2003. Destination competitiveness: determinants and indicators. Current issues in tourism, 6(5):369-414. [https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500308667962]. [ Links ]

Ferreira, J.J.M., Fernandes, C.I. & Ratten, V. 2016. A co-citation bibliometric analysis of strategic management research. Scientometrics, 109(1):1-32. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2008-0]. [ Links ]

Hanefeld, J., Smith, R. & Noree, T. 2016. Medical tourism. World Scientific Handbook of Global Health Economics and Public Policy: Health System Characteristics and Performance, 3:333-350. [https://doi.org/10.1142/9789813140530_0008]. [ Links ]

Hashim, N.A., Mukhtar, M. & Safie, N. 2019. Factors affecting teachers' motivation to adopt cloud-based e- learning system in Iraqi deaf institutions: A pilot study. Conference proceedings.In 2019 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics. July 9- 10. Bandung, Indonesia. pp. 272-277. [https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEEI47359.2019.8988854]. [ Links ]

Herciu, M. 2013. Measuring international competitiveness of Romania by using Porter's diamond and revealed comparative advantage. Procedia Economics and Finance, 6:273-279. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(13)00140-8]. [ Links ]

Heslinga, J., Groote, P. & Vanclay, F. 2020. Towards resilient regions: policy recommendations for stimulating synergy between tourism and landscape. Land, 9(44):44-53. [https://doi.org/10.3390/land9020044]. [ Links ]

Hinton, P.R., McMurray, I. & Brownlow, C. 2014. SPSS explained. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315797298]. [ Links ]

Hofstee, E. 2015. Constructing a good dissertation: a practical guide to finishing masters, MBA or PhD on schedule. Johannesburg, South Africa: EPE publisers. [ Links ]

latu, C., Ibãnescu, B.C., Stoleriu, O.M. & Munteanu, A. 2018. The WHS designation: a factor of sustainable tourism growth for Romanian rural areas?, Sustainability, 10(3):626-638. [https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030626]. [ Links ]

Idrus, S.H. 2020. Impact of tourism policy implementation in the development of regional tourism strategic area: case study: Nambo Beach in Kendari City, Indonesia. Humanities and Social Science Research, 3(2):18- 24. [https://doi.org/10.30560/hssr.v3n2p18]. [ Links ]

Jaafar, M., Rasoolimannesh, S.M. & Lonik, K.A.T. 2015. Tourism growth and entrepreneurship: empirical analysis of development of rural highlands. Tourism Management Perspectives, 14:17-24. [https://doi.org/10.1016/Ltmp.2015.02.001]. [ Links ]

Jafari, J. & Ritchie, J.B. 1981. Toward a framework for tourism education: problems and prospects. Annals of tourism research, 8(1):13-34. [ Links ]

Jovanovic, S. & Ivana, I.L.I.C. 2016. Infrastructure as important determinant of tourism development in the countries of Southeast Europe. Ecoforum journal, 5(1):288-294. [ Links ]

Karalkova, Y. 2016. Rural tourism destination competitiveness: Portugal vs. Belarus. Portugal: Polytechnic Institute of Bragança. (Dissertation- Masters). [ Links ]

Ketels, C. 2016. Recent research on competitiveness and clusters: what are the implications for regional policy? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 6(2):269-284. [https://doi.org/10.1093/cires/rst008]. [ Links ]

Kubickova, M. & Hengyun, L. 2017. Tourism competitiveness, government and tourism area life cycle model: the evaluation of Costa Rica, Guatemala and Honduras. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(2):223-234. [https://doi.org/10.1002/itr.2105]. [ Links ]

Kusumah, A.H.G. & Nurazizah, G.R. 2016. Tourism destination development model: a revisit to Butler's area life cycle. Heritage, Culture and Society: Research agenda and best practices in the hospitality and tourism industry, 31. [https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315386980-6]. [ Links ]

Kryukova, E.M. & Khetagurova, V.S., 2020. Recommendations for the development of the tourism and hospitality industry in the Russian Federation: agricultural tourism. Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings, pp.279-288. [ Links ]

Lew, A.A., Hall, C.M. & Williams, A.M. 2014. The Wiley Blackwell companion to tourism. John Wiley & Sons. [https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118474648]. [ Links ]

Lin, V.S., Yang, Y. & Li, G. 2019. Where can tourism-led growth and economy-driven tourism growth occur? Journal of Travel Research, 58(5):760-773. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518773919]. [ Links ]

Lo, M., Mohamad, A.A. Chin, C. & Ramayah, R. 2017. The impact of natural resources, cultural heritage and special events on tourism destination competitiveness: The moderating role of community support. International Journal of Business and Society, 18(4):763-774. [ Links ]

McKercher, B. & Wong, I.A. 2020. Do destinations have multiple lifecycles? Tourism Management, 83:1-5. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.tourman.2020.104232]. [ Links ]

Meyer, D. F. & Meyer, N. 2015. The role and impact of tourism on local economic development: a comparative study. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 21(1):197-214. [ Links ]

Mitra, S.K. 2019. Is tourism-led growth hypothesis still valid? International Journal of Tourism Research, 21 (5):615-624. [https://doi.org/10.1002/itr.2285]. [ Links ]

Naidoo, R. 2016. The competition fetish in higher education: varieties, animators and consequences. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37(1):1-10. [https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1116209]. [ Links ]

Nur, A.C., Akib, H., Niswaty, R., Aslinda, A. & Zaenal, H. 2019. Development partnership strategy tourism destinations integrated and infrastructure in South Sulawesi Indonesia. Conference proceedings. International conference on public organization ASIA Pacific society for public affairs. Khon Kaen Province, Thailand, 28-30 August. pp. 271-283. [https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3497230]. [ Links ]

Ohe, Y., Ikei, H., Song, C. & Miyazaki, Y. 2017. Evaluating the relaxation effects of emerging forest-therapy tourism: a multidisciplinary approach. Tourism Management, 62:322-334. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.tourman.2017.04.010]. [ Links ]

Phillip, S., Hunter, C. & Blackstock, K. 2010. A typology for defining agritourism. Tourism management, 31(6):754-758. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.tourman.2009.08.001]. [ Links ]

Qu, H., Kim, H.L., & Im, H.H. 2011. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tourism Management, 32(3):465-476. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.tourman.2010.03.014]. [ Links ]

Ritchie, J.R.B., & G.I. Crouch. 1993. Competitiveness in international tourism: a framework for understanding and analysis. In Proceedings Managing Global Transitions Competitiveness of Slovenia as a Tourist Destination 189 of the 43rd Congress of the Association Internationale d'Experts Scientifique de Tourisme on Competitiveness of Long-Haul Tourist Destinations, 23-71. St. Gallen: aiest [ Links ]

Rizzi, P. & Graziano, P. 2017. Regional perspective on global trends in tourism. Emerging Issues in Management, (3):11-26. [https://doi.org/10.4468/2017.3.02rizzi.graziano]. [ Links ]

Roy, S.C. & Roy, M. 2015. Tourism in Bangladesh: Present status and future prospects. International Journal of Management Science and Business Administration, 1(8):53-61.[ https://doi.org/10.18775/iimsba.1849-5664-5419.2014.18.1006]. [ Links ]

Stetic, S., Simicevic, D., Pavlovic, S. & Stanic, S. 2014. Business tourism competitiveness model: Competitiveness of Serbia as a business tourism destination. Quality-Access to Success Serbia, 14(5):176-194. [ Links ]

Tien, N.H., Thai, T.M., Hau, T.H., Vinh, P.T. & Long, N.V.T. 2019. Solutions for Tuyen Quang and Binh Phuoc Tourism Industry Sustainable Development. Comparative Analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing Management and Sales, 2(1):101-107. [ Links ]

Tussyadiah, I. P. & Pesonen, J. 2016. Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. Journal of Travel Research, 55(8):1022-1040. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515608505]. [ Links ]

Truong, T.L.H., Lenglet, F. & Mothe, C. 2018. Destination distinctiveness: concept, measurement, and impact on tourist satisfaction. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 8:214-231. [https://doi.org/10.1016/Lidmm.2017.04.004]. [ Links ]

UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organisation). 2008. International recommendations for tourism statistics. Madrid, Spain. [ Links ]

Ushakov, D., Ermilova, M. & Andreeva, E. 2018. Destination branding as a tool for sustainable tourism development: The Case of Bangkok, Thailand. Revista Espacios, 39(47):9-21. [ Links ]

Van der Schyff. T. 2021. The development and testing of a measurement instrument for regional tourism competitiveness facilitating economic development. North-West University: Vanderbijlpark. (PhD-Thesis). [ Links ]

Webster, C. & Ivanov, S. 2014. Transforming competitiveness into economic benefits: does tourism stimulate economic growth in more competitive destinations? Tourism Management, 40:137-140. [https://doi.org/10.1016/Ltourman.2013.06.003]. [ Links ]

Williams, A. M. & Shaw, G. 1988. Tourism and development: Introduction. A. M. Williams, A.M., & Shaw, g., eds. Tourism and Economic Development: Western European experiences. London: Belhaven Press. pp. 111. [ Links ]

WTTC (World Travel and Tourism Council). 2019b. Travel and tourism: global economic impact and trends 2019. Geneva: Switzerland. [ Links ]

Yeh, C.M. 2020. Critical accommodation information for travel opinion leader. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 11 (1):1-14. [https://doi.org/10.14807/iimp.v11i1.1021]. [ Links ]

Zvyagintseva, E.P., Episheva, O.S., Tsygankova, E.E., Azarova, O.A. & Shelygov, A.V. 2020. Functional aspects of the development of international tourism. Journal of Environmental Management & Tourism, 4(44):954-959. [https://doi.org/10.14505//iemt.11.4(44).19]. [ Links ]

ANNEXURE A: PRE-TESTING MEASUREMENT INSTRUMENT

Dear respondent,

My name is Tanya Van der Schyff, a Ph.D. student in Economics at the North-West University (Vanderbijlpark Campus), under the supervision of Prof. Danie Meyer and Associate Prof. Elsabé Keyser. My study focuses on the development of a tourism destination competitiveness measurement instrument. This instrument aims to assist in the tourism competitiveness analysis of regions, and as a result, be used to make comparisons between regions and potentially contribute to the development of regional development strategies. To construct this instrument, the most important and applicable determinants of tourism destination competitiveness need to be identified and analysed.

You have been identified as a specialist respondent in both the economics and the tourism sector research field. You are kindly requested to complete the questions below, which will take approximately 10 to 15 minutes to complete. The questionnaire contains three main dimensions of determinants, namely, (1) Resources, (2) Infrastructure, (3) Support Environment & Authorities, and includes a total of 21 determinants (also known as factors).

The following step-by-step instructions are provided to complete Table 1:

Step 1: Kindly rank from highest to lowest priority the dimensions (1) Resources, (2) Infrastructure, (3) Support Environment & Authorities from 1 to 3 (1 being the highest and most crucial ranking, 2 being an average important ranking and 3 the lowest less significant ranking).

Please note: You may only use each ranking value once. For example, Resources = "2", Infrastructure = "1" and Support Environment & Authorities = "3"

Step 2: Rank each determinant within Dimensions 1, 2, and 3 by use of the following:

The weighting values should be allocated to indicate the importance of the dimension and determinants in achieving destination competitiveness for successful tourism and regional development. Tourism destination competitiveness (TDC) can be explained as the ability of the place to optimise its attractiveness for residents and non-residents, to deliver quality, innovative, and attractive tourism services to consumers and to gain market shares in the domestic and global marketplaces, while ensuring that the available resources supporting tourism are used efficiently and in a sustainable way.

If there is any uncertainty regarding what each determinant involves, please find the description of each determinant in Table 2.

After completion of the table, please email it back to me at vds.tanya@gmail.com. I would like to thank you for allocating your valuable inputs and time to this study. Please feel free to contact Tanya if you have any inquiries or inputs.

Thank you, Tanya Readers