Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.19 no.2 Meyerton 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcm21073.161

ARTICLES

Strategy: An understanding of strategy for business and public policy settings

Jabulani Dhlamini

Edinburgh Business School, Heriot-Watt University, United Kingdom. Email: dhlamini.iabulani@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6291-6231

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: The review aims to develop an understanding of the definition of 'strategy' to create an alignment of its use in business and public policy settings. There is no commonly accepted definition of strategy, it has widely different definitions in a range of settings, whether in business, government, sports, or civic society

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: A review of the literature was conducted from an exploratory perspective to identify academic articles and other publications that provide the most relevant content and research on strategy. The literature that was selected contained a substantive perspective on strategy, and covered any of the four different levels of strategy: grand strategy, corporate strategy, business strategy, and functional strategy

FINDINGS: The literature review shows that there are multiple definitions of strategy in relation to its use in business and public policy settings. There is also a lack of studies that position grand strategy with the three other levels of strategy

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: This review contributes to the body of knowledge by (i) providing a theoretical framework to assist organisations in business and various public policy settings to develop and define their strategies; (ii) assisting in creating an alignment in business and public policy settings in the use of the term 'strategy'; and (iii) providing a theoretical positioning of grand strategy as it relates to the other levels of strategy such as corporate strategy, business strategy, and functional strategy

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The review assists in the process of standardising the use of the term 'strategy' in business and public policy settings, as well as positioning grand strategy as it relates to the other levels of strategy such as corporate strategy, business strategy and functional strategy

JEL CLASSIFICATION: M2; O; P

Keywords: Business strategy; Corporate strategy; Functional strategy; Grand strategy; Strategy

1. INTRODUCTION

The word 'strategy' comes from the Greek word strategos, a term used to define the art of the general in the army (Ronda-Pupo & Guerras-Martin, 2012; Freedman, 2015). Strategy is used in general to explain how a set of objectives, whether short-term or long-term, will be achieved (Freedman, 2015). However, there is no general consensus on the definition of strategy or of the strategy concept with regard to its use in various settings, whether in business, government, sports, or civic society (Markides, 2004; O'Regan & Ghobadian, 2007; Ronda-Pupo & Guerras-Martin 2012; Freedman, 2015). The lack of consensus is arguably the result of the dynamic relationship between strategy and the environment, encompassing both internal and external environments (Ungerer, 2019). The internal environment is the structure, culture, and resources controlled by an organisation, whereas the external environment comprises all the elements that impact or influence an organisation that are not under its direct control, such as the regulatory environment, competitors, customers, and globalisation (Ungerer, 2019). The strategic ambition, which is defined by the mission and vision, is another consideration that is important in determining strategy. The mission statement of an organisation sets out what it does in terms of its purpose and focus areas, while the vision statement provides the aspirational long-term goal of what the organisation aims to become and to do in the future (Skrt & Antoncic, 2004; Cady et al., 2011). Another perspective to consider is the time horizon for the strategy. The dynamism and complexity associated with addressing constantly changing environmental pressures, and the long-term perspective that strategy should have, are some of the reasons it is difficult to have a standardised definition of strategy.

It is argued that there is good strategy and bad strategy. In this regard, Rumelt (2012) stated:

"A good strategy does more than urge us forward toward a goal or vision; it honestly acknowledges the challenges we face and provides an approach to overcoming them." (Ungerer et al., 2016:22)

It is further argued that a lot of organisations claim to have a strategy, but what they actually define as strategy either (i) does not clearly spell out what it is they will do to achieve their mission and vision, or (ii) describes their goals and objectives as their strategies (Markides, 2004; Vermeulen, 2017). Thus a strategy is not the elements that are necessary to define it, such as the mission, vision, goals, and objectives, or the insight gained into the business environment (Watkins, 2007; Vermeulen, 2017). Other researchers have attempted to address the definition of strategy comprehensively, given that it is a complex phenomenon (Mishra et al., 2017). In this regard, Mintzberg (1987) proposed five definitions of strategy to address the different interpretations of the concept, thus providing an understanding of strategy for a wider audience.

Both business and public policy settings develop strategies to achieve success; however, the term strategy is defined quite differently across these settings (Markides, 2004; Vermeulen, 2017; Mishra et al., 2017). Business involves the establishment and management of an enterprise to provide products and/or services, mostly for a profit or for a defined benefit (Needle & Burns, 2010). Whereas public policy settings are the various legislative and public institutions directly under the control of or working alongside government in the delivery of products and services to the wider society (Acs & Szerb, 2007). Having an aligned definition of strategy and of its use would be helpful for various stakeholders in communicating the strategy's intent and thereafter its implementation. Over and above the benefit of alignment, this would facilitate the better allocation of resources in the process of implementing the strategy.

The review also positions grand strategy along with the other levels of strategy. 'Grand strategy' was defined as a plan for a country or a regional block to achieve its set objectives in relation to prevailing geopolitics and to its desired economic benefits (Balzacq et al., 2019). Considering that grand strategy is positioned at the higher country and/or regional level, it is important to have insight into grand strategy when formulating and implementing the other levels of strategy, such as corporate strategy or business strategy. This review contributes to the body of knowledge by (i) providing a theoretical framework to assist organisations in business and various public policy settings to develop and define their strategies; (ii) assisting in creating an alignment in business and public policy settings in the use of the term strategy; and (iii) providing a theoretical positioning of grand strategy as it relates to the other levels of strategy, such as corporate strategy, business strategy, and functional strategy.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature review which sets the theoretical foundation commences by setting out the perspectives on strategy, thereafter the detail on the four levels of strategy and an analysis of definitions of strategy are presented.

2.1 Perspectives on strategy

It is argued that strategy should achieve a competitive advantage and not merely aim to achieve operational effectiveness (Porter, 1996). A competitive advantage is achieved through determining the unique activities that the organisation will pursue to reach its desired future state (Porter, 1996; Box, 2011; Sims et al., 2016). The competitive advantage realised from the chosen strategy is the net value created through (i) products/services offered to customers;

(ii) realised revenues from customers; (iii) optimised expenditure for inputs into the value chain; (iv) minimised costs associated with maintenance of the organisation; and/or (v) optimising investment in future value-creating activities such as market research, innovation, and training (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2007). The achievement of a competitive advantage is key for the survival of organisations, as it will allow them to have the edge over others in the same industry or business. This means that they would stand a better chance of building up reserves in the form of resources that they could use to grow and be sustainable in the long term.

The fit of the combination of activities or initiatives pursued by an organisation is important to avoid the various activities or initiatives affecting each other negatively, to the detriment of achieving the desired competitive advantage (Porter, 1996). The requirement to have fit - a better integration of the activities or initiatives, taking the available resources or capabilities into consideration - brings about the need for organisations to make choices about which activities or initiatives to pursue (Whittington, 2001; Jarzabkowski & Balogun, 2009). The pressure to increase organisational performance could result in functional or departmental silo-driven choices that could affect the fit of activities or initiatives, thus compromising the achievement of the desired competitive advantage. Put another way, the choice of activities or initiatives, over and above being aligned to the strategy, should be based on the activities or initiatives that result in the organisation realising the most benefit from the combined set of activities or initiatives.

It has been stated that a good strategy has three core components: (i) a diagnosis that clearly shows stakeholders what is going on by identifying the challenges, obstacles, and opportunities; (ii) a guiding policy to coordinate and focus the efforts of the organisation; and (iii) a set of coherent actions to implement the guiding policy (Rumelt, 2012). It has also been posited that strategy is set within three parameters: (i) who the targeted customers will be; (ii) what products or services the organisation will offer its chosen customers; and (iii) how it will go about delivering the chosen products and services (Markides, 2004). The outcome of a strategy being either good or bad, depends in the end on whether the proposed strategic plans will enable the achievement of the desired future state or a sustainable competitive advantage (Rumelt, 2012). The view that good strategy comprises three core components (Rumelt, 2012) or three parameters (Markides, 2004) supports the argument presented by Porter (1996) that there should be a fit of the combined activities or initiatives that are chosen. In a paper by Phillips (2011), it is posited that strategy is about the 'what' and 'why', and then the 'how' and 'when', all within the context of the organisation - that is, the internal and external environments, the now and the desired future (Phillips, 2011). Although Phillips (2011) views strategy as being the 'what' and 'why', this view is the same as that of other researchers who believe that strategy is the 'how with strategic intent'.

2.1.1 Types of strategy

Strategy can either be planned or emergent (Mintzberg, 1994; Fletcher & Harris, 2002; Pretorius & Maritz, 2011; Neugebauer et al., 2016; Ungerer et al., 2016). The planning approach follows a structured process in its formulation of strategy, usually at predefined periods, while with the emergent approach, strategy emerges from the day-to-day processes or organisational initiatives, and is formed over time rather than at predefined periods (Mintzberg, 1994; Whittington, 2001; Fletcher & Harris, 2002; Pretorius & Maritz, 2011; Neugebauer et al., 2016). The planned approach is associated with benefits such as achieving a competitive advantage and the desired organisational performance that arises as a result of the formal process of strategic planning (Glaister & Falshaw, 1999; Thompson et al., 2012; Ungerer, 2019).

It has also been posited that most realised strategies are an outcome of the combined influence of planned strategy and emergent strategy (Figure 1). This approach is termed 'planned emergent' (Mintzberg & Waters, 1985; Wolf & Floyd, 2017). The planned strategies that would mostly have been developed by senior management are likely to be changed or slightly adjusted as a result of the influence of middle managers, who are mostly the drivers of the emergent strategy approach; as a result, the strategy formulation approach in the end is neither solely planned nor solely emergent - hence 'planned emergent' (Neugebauer et al., 2016; Wolf & Floyd, 2017).

The planned strategy is also influenced by the strategic learnings gained from the strategy process. Strategic learning is the insight gained from the experience and feedback following the implementation and execution of the strategy, which results in realised strategies and unrealised strategies (Mintzberg & Waters, 1985).

Whittington (2001) stated that the planned approach can be viewed as the classical and/or systematic approach, with the emergent approach being seen as the evolutionary and/or processual approach (Mishra et al., 2017). The classical and evolutionary approaches are focused on maximising profit, whereas the systematic and processual approaches are focused on following predetermined processes or conforming to the norm (Whittington, 2001). This is illustrated in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2, the goal of business is largely to maximise profit; however, this perspective could be interpreted for all other forms of organisations as the achievement of their desired goals and objectives.

Another view of the planned emergence approach is that it is a process of formulating strategy through an infusion of input and influence in strategy formulation from the bottom up and from the top down (Grant, 2003; Redlbacher, 2020). The bottom-up input is provided by the business unit managers, while the top-down input into strategy formulation will come from more senior corporate executives who provide strategic direction in the form of mission and vision statements and/or strategic initiatives (Grant, 2003). In essence, there is wider input from the organisation's staff in formulating strategy by following a planned emergence approach (Redlbacher, 2020). The view that a realised strategy is the result of the concept of planned emergence is plausible. Though senior management usually develop the planned strategies, these are still subject to the influence of middle management during the strategy's implementation and execution phases. This is because middle management is closer and more directly exposed to day-to-day environmental influences, and thus will likely respond by changing the strategy in the light of those influences or pressures.

The process that is commonly associated with the planned approach is strategic planning, which is the process of setting an organisation's mission, vision, and strategy (O'Regan & Ghobadian, 2007; Jarzabkowski & Balogun, 2009). It has also been argued that strategic planning is an organisation's road map, enabling it to understand (i) where it is now, (ii) how it got to its present state, (iii) where it wants to be in the future, and (iv) how it intends to get to its future state (Alkhafaji & Nelson, 2013).

2.2 Levels of strategy

There are four different levels of strategy: the regional and/or country level, multi-business or diversified organisations, single structure organisations, and organisational departments/ divisions or functions. The different levels of strategy are interlinked and, to a large extent, are dependent on each other (Hofmann, 2010). The four levels of strategy are illustrated in Figure 3 and are described in more detail in the sub-sections that follow.

2.2.1 Grand strategy

A grand strategy is a plan for a country or regional block to achieve its set objectives in relation to the prevailing geopolitics and the desired economic benefit (Balzacq et al., 2019). It was defined by Feaver (2009) as a collection of plans and policies to achieve a country's national interests. He further stated:

Grand strategy blends the disciplines of history (what happened and why?), political science (what underlying patterns and causal mechanisms are at work?), public policy (how well did it work and how could it be done better?), and economics (how are national resources produced and protected?) (Feaver, 2009).

As highlighted in the statement by Feaver (2009), the disciplines that influence the development of grand strategies are history, political science, public policy, and economics. Political science is the study of knowledge related to the state, government, and the respective political systems, whereas politics is concerned with the governance of the state and the political power/influence associated with this capability (Nicholson, 1977). Public policies are principles or guidelines, both written and unwritten, that relate to the law, regulatory requirements, and trade preferences set by public officials/institutions or governments (Hassel, 2015). Economics is the study of the well-being of a nation, which is primarily developed by enabling a better standard of living for a nation's citizens, measured by analysing the gross domestic product (GDP) of the nation (Datta, 2011). At a high level, the GDP of a nation is measured by looking at the net result of the total goods and services it produces, and the total imports it receives (Datta, 2011; Karagiannis & Madjd-Sadjadi, 2012). When directed through the development and adoption of appropriate economic strategies, this will deliver the desired economic results. Economic strategy is a developmental plan for a nation to achieve long-term objectives for job creation, growth, monetary and fiscal stability, a manageable balance of payments, and promoting trade (Karagiannis & Madjd-Sadjadi, 2012). A grand strategy can thus be deduced from all the various public policy settings (political science, public policy, and economics) of a nation/country or regional block to the extent that they influence the overall state of the nation/country or regional block.

A historical perspective on a country can be gained by understanding the political strategies, public policies, and economic strategies that it has previously adopted, and assessing their performance or effectiveness. Popescu (2017) argued that a successful grand strategy can be seen through the achievement of a country's desired foreign policy. Foreign policy can be viewed as country-specific goals and objectives, as it relates to how the country wants to position itself against other countries (Popescu, 2017).

With globalisation, the need for countries worldwide to develop grand strategies is important; and this very important practice is no longer the realm of the big economies such as the United States of America, China, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, or Russia (Fagerberg et al., 2007). Grand strategy, outside of its current practice, was once associated with warfare, and thus was closely aligned to the military, which originated the term 'strategy' (Freedman, 2015).

Because globalisation is a reality of the 21st century world we live in, it is important for every country or regional block to have objectives for positioning itself against other competing forces in the world. The factors that influence how a country or regional block performs or is positioned are no longer limited to factors under its control within its borders only, but are based on factors that can influence it and also those it can influence beyond its borders (Balzacq et al., 2019). In this regard, to enable a business to formulate practical strategies, those strategies need to take cognisance of the country's grand strategy. This is even more the case if the grand strategy is going to influence the business' operating environment through its impact on the political environment, public policy, and economics. Thus, to give businesses an opportunity to develop appropriate strategies and to thrive in this globalised world, there has to be an alignment between corporate strategies and the grand strategies of the country or regional block in which the businesses operate.

To put the competitive advantage of nations/countries into perspective in relation to the competitive advantage of organisations, Porter (1990) defines the competitive advantage of nations as the availability of four factors: (i) factor conditions, which is about the availability of the necessary resources and skills for competitive advantage in an industry; (ii) demand conditions; (iii) related and supporting industries; and (iv) a firm's strategy, structure, and rivalry. Generally, competitive advantage is achieved through industrial innovation and improvements related to the effective use of the nation's key factors of production, which include land (natural resources under the control of the nation), labour, capital, and infrastructure (Huggins & Izushi, 2015). A paper by Delgado et al., (2012) argues that there are determinants that influence the competitiveness of a nation. The determinants are classified in two ways: as (i) micro-economic competitiveness, which is determined by the social infrastructure, political institutions, and monetary and fiscal policies; or as (ii) macro-economic competitiveness, which is determined by the quality of the national business environment and by the sophistication of companies' operations and their respective strategies (Delgado et al., 2012). The outcome of the two factors determines how a nation is competitively positioned against other nations. The competitiveness of a nation is ultimately determined by the level of its global investment attractiveness - in essence, how attractive it is for investors to channel capital to the nation because there is a significant gap between the cost of production and the nation's output - its GDP (Delgado et al., 2012). Thus, the better a nation is at influencing and directing how the two dimensions (micro- and macro-economics) are developed, the better will be the outcome of providing a good national environment and higher standard of living for its citizens, revealed in higher income levels, job creation, and increased productivity (GDP).

2.2.2 Corporate strategy

Corporate strategy determines what businesses to pursue and how they are managed (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2007; Pidun, 2019; Feldman, 2020). This is essentially influenced by the corporate ambition that would have been determined by the mission and vision of the organisation. In this regard, corporate strategy involves the process of selecting a portfolio of businesses to own and manage (Porter, 1989; Bowman & Helfat, 2001). In some instances the businesses are not necessarily registered stand-alone entities, but are separately identifiable divisions in one corporate entity. Porter (1989) posits that four concepts are associated with corporate strategy: (i) portfolio management - a core capability in managing multiple businesses; (ii) restructuring - an ability to identify businesses that are not well run or that are performing poorly, and to turn them around to be profitable or more profitable; (iii) transfer of skills - to support the core functions of the businesses under its control; and (iv) shared activities - this results in lower costs through economies of scale and opportunities for operational efficiency. Thus, any corporate strategy should aim to follow one or more of these concepts to derive value, as the concepts are not mutually exclusive. Strategy at this level assesses the business models of the various businesses under its control or in which it has interests, to ensure that, together, the portfolio of businesses provides the best combined value to the corporate entity.

One of the frameworks that organisations can use to determine which businesses or divisions to dispose of, keep, or acquire as part of their portfolio is the BCG matrix, which was introduced by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG). The BCG matrix has four quadrants: (i) question marks represent business units with a low market share in a high-growth market; (ii) dogs represent business units with a low market share in a shrinking market; (iii) stars represent business units that have a high growth potential but have a low market share; and (iv) cash cows represent business units with a high market share in a market that is mature but that is possibly not growing or is not growing at previous rates (Mohajan, 2017). However, the principle of having fit in the combination of businesses in the portfolio is important, and has to be taken into consideration in deciding which businesses to have an interest in, as it can affect shareholder value (Feldman, 2020).

The BCG matrix can also be used to manage the corporate portfolio to achieve the intended outcomes in combination with other frameworks, such as the framework for corporate strategy posited by Feldman (2020) that covers (i) intra-organisational actions that coordinate resources within a firm's boundaries; (ii) inter-organisational actions that coordinate relationships across a firm's boundaries; and (iii) extra-organisational actions that decide which businesses belong inside or outside of a firm's boundaries.

An approach that is commonly used to identify value in a portfolio of businesses or divisions involves identifying business synergies; and these can be linked to two concepts introduced by Porter (1989): (i) the transfer of skills, and (ii) shared activities. Business synergies are the available opportunities that can be explored to derive value through economies of scale (Pidun, 2019). Thus where synergies are identified, the associated services are usually delivered by a centralised corporate division or head office as a shared service to the portfolio of businesses or divisions. Such services include finance, procurement, human resources, and information technology support. Through a function such as finance, the head office or corporate centre can have an overall view of the performance of each business; and that enables it to redeploy or allocate capital across the portfolio of businesses. In essence, corporate strategy is concerned with achieving corporate advantage, which is the positive value derived from the selection of businesses that make up the portfolio (Porter, 1989; Bowman & Helfat, 2001; Pidun, 2019).

2.2.3 Business strategy

A business strategy applies to single stand-alone businesses or separate identifiable business units. Thus, a business strategy is how an organisation or business unit competes in a specific market (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2007; Pidun, 2019). In essence, a business strategy is concerned with achieving a competitive advantage (Pidun, 2019). To achieve a competitive advantage, as prescribed by Porter (1996), the unique activities can be determined using a number of methods; but the two most common methods are (i) the resources-based view, and (ii) the five competitive forces model.

The resources-based view approaches strategic planning from the perspective of progressively leveraging the available organisational resources to achieve a competitive advantage (Sims et al., 2016; Majama & Magang, 2017). The resources of the organisation are either the capabilities and competencies it owns or those that are under its control (Sims et al., 2016). Sims et al., (2016) also argue that, throughout their life cycles, organisations adjust or renew their resource pools by acquiring and disposing of resources in response to environmental changes. However, this should be aligned to their mission and vision statements. Capabilities are the processes that organisations have and follow to convert the various inputs in their value chains into the desired outputs (Sims et al., 2016). Competencies, on the other hand, are the unique skills they possess to perform tasks - skills that an organisation would have gained from the organisation's overall experiences over the years, and through the experience of its staff members and other contracted service providers (Sims et al., 2016). It is through a set of core competencies that organisations can achieve a competitive advantage (Sims et al., 2016).

To assess an industry in order to gain insight into developing the appropriate business strategy to achieve a competitive advantage, Porter (1980) introduced the five competitive forces model, consisting of: (i) rivalry among competitors; (ii) threats of new entrants; (iii) threats of substitute commodities; (iv) customers' bargaining power; and (v) suppliers' bargaining power (Chimucheka, 2013). The ability of the organisation to respond or adapt to all five forces will determine its overall performance, growth, and sustainability (Chimucheka, 2013). An understanding of the industry's competitive forces will allow organisations to position their products or services more appropriately and to make the necessary adjustments to their business strategies to remain sustainable, and so achieve a competitive advantage.

Business strategy, as compared with corporate strategy, is also supposed to have a long-term focus. To compare business strategy better against corporate strategy: a business strategy is foundational to achieving a corporate strategy, since the individual businesses in a portfolio of businesses (which would have been determined by the corporate strategy) are each supposed to deliver on their goals and objectives and so contribute to the overall achievement of the corporate strategy. This is the case when a business is part of a corporate entity with multiple businesses.

2.2.4 Functional strategy

A functional strategy is the plans and choices set by divisions or departments within an organisation, such as finance, marketing, human resources (HR), information technology (IT), facilities management (FM), procurement, and research and development, to achieve the respective functions' goals and objectives in support of the delivery of the business strategy (Connor, 2001; Caglar et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2014). Functional strategy is also known as 'operational strategy'. Operational or functional strategies are normally focused on the short term; thus their planning time horizon ranges from about a year to two years. They are geared to enabling the formulation and implementation of a suitable functional operating model. An operating model brings together the required resources, such as people, processes, technology, and infrastructure, to operationalise the business model to deliver or achieve the business strategy (Caglar et al., 2013).

In defining 'strategy', Porter (1996) posited that it is not about achieving operational efficiency. However, when determining a functional strategy, achieving operational efficiency is the desired outcome, as it will ensure that resources are optimally allocated and used in the short term to achieve the overall business strategy. Functional strategy, being focused on the short term, adopts a position that is contrary to the perspective that all strategy in business should be long-term. However, this can be countered on the basis that functional strategy is not developed in isolation from business strategy, since the supporting functional divisions and/or departments operate as part of the overall business and/or organisational structure. Even in the business environment, this view supports the position that there is no universally approved use of the term 'strategy' (Markides, 2004; Freedman, 2015).

It has been argued that, for functional strategy to be positioned to deliver on the longer-term mission, it should have the following elements: (i) establishing priorities that are aligned to the overall business strategy; (ii) having an operating model that is aligned to deliver value in line with the set priorities; and (iii) appropriately allocating resources to enable the desired operating model (Caglar et al., 2013). Functional strategy is thus also seen as the process of implementing business strategy, since it involves the development and enabling of activities that lead to the realisation of business strategy goals and objectives (Connor, 2001; Caglar et al., 2013).

2.3 Definitions of strategy

Based on Mintzberg's (1987) definition of strategy, it was suggested that there are five definitions of strategy - that a strategy can be seen as a plan, a ploy, a pattern, a position, or a perspective. Thus, it is important to consider some of their interrelationships (Cherp et al., 2007). Cherp et al., (2007:626) state that Mintzberg's (1987) five definitions of strategy are as follows:

(1) "A plan - a consciously intended course of action, a set of rules to deal with the situation;

(2) A ploy - a scheme intended to outmaneuver opponents and strengthen useful alliances;

(3) A pattern - in a stream of actions, consistency in behaviour (whether or not intended); here strategies result from actions, not designs;

(4) A position - locating an organization in its environment; its 'ecological niche', or, in military terms, literally a position on a battlefield;

(5) A perspective - an ingrained way of perceiving the world; 'strategy in this respect is to the organization what personality is to the individual'."

Although Mintzberg (1987) states that there are five definitions of strategy, ideally they should not be read independently of each other, as the five definitions project or present a more comprehensive view of strategy when they are read together. As a complex phenomenon, strategy is best defined by taking the aspects of all five of Mintzberg's (1987) definitions, since this will likely address different interpretations of strategy, thus providing a wider audience with an understanding of the term.

Strategy is commonly defined as an action plan or how an organisation moves from its current state to a desired future state (Skrt & Antoncic, 2004; Box, 2011; Grundy, 2012). It is important to note that a well-planned strategy cannot be determined outside of the context of the mission, vision, capabilities, and environment of the organisation, as these elements are foundational to its existence. To achieve the vision, the organisation needs to understand its environment; it also needs a set of capabilities in the form of people, processes, technology, and infrastructure. Thus, a well-planned strategy needs to take into consideration the mission, vision, capabilities, and environment of the organisation.

Strategy from an economic, political, and societal perspective was defined by Lawrence Freedman as the 'art of creating power' (Dixit, 2014). This can be interpreted as the process of using one's influence and resources to achieve a desired outcome. This definition is more suited to defining a nation/country's and/or regional block's grand strategy. A similar definition was posited by Ungerer et al., (2016:21) as:

"how an organisation wants to move forward and how it wants to advance the interests of stakeholders."

Strategy has also been defined in these ways:

"The long-term direction of an organization." (Johnson et al., 2014:3)

"A plan of action designed to achieve a long-term or overall aim." (Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2018)

"It is about getting more out of a situation than the starting balance of power would suggest. It is the art of creating power." (Freedman, 2015:xii)

Ackermann and Eden (2011:5) view strategy as

"agreeing priorities and then implementing those priorities towards the realisation of organisational purpose."

The definition of strategy that has been cited as one of the most comprehensive is the one by Chandler (1990:13):

"the determination of the basic long-term goals of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals."

The Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary defines strategy as:

"a detailed plan for achieving success in situations such as war, politics, business, industry, or sport, or the skill of planning for such situations" (Cambridge Dictionary, 2008:1550).

Another definition of strategy, that of Grundy (2012), is how an organisation gets from where it is now to where it wants to be in the future with a real competitive advantage. He also argues that there are five elements to this definition. The first three are: (i) knowing where you are now, (ii) knowing where you want to be, and (iii) knowing how you will get there; while the remaining two are that (iv) the 'how' is based on competitive advantage, and (v) the 'how' is real and not just in one's head (Grundy, 2012).

The three definitions of strategy presented by Chandler (1990), Ackermann and Eden (2011), and Johnson et al., (2014) align with the view that strategy is an action plan, or how an organisation moves from its current state to a desired future state (Skrt & Antoncic, 2004; Box, 2011; Grundy, 2012). This perspective - that strategy is an 'action plan', or 'how' an organisation moves from its current state to a desired future state - is simple and is probably easier for most organisations to understand, thus creating a common understanding of strategy. Table 1 summarises and highlights most of the strategy definitions that have been cited in this section.

At a high level, strategy can be viewed as a way of linking an organisation to its environment (Ronda-Pupo & Guerras-Martin, 2012). Another view of strategy is to see it as the choices that are made relating to the activities or initiatives an organisation chooses to pursue, established as either a corporate strategy or a business strategy (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2007; Favaro, 2015). This distinction between the different levels of strategy - specifically as it relates to corporate strategy and business strategy - is necessary, since the two are usually used interchangeably (Favaro, 2015). Business strategy is how an organisation or business unit competes in a specific market, whereas corporate strategy determines what businesses to pursue and how they are managed (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2007; Pidun, 2019).

3. METHODOLOGY

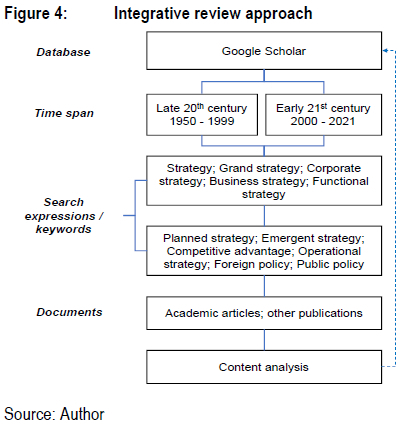

A review of the existing literature on strategy in general, and on any of the four different levels of strategy - 'grand strategy', 'corporate strategy', 'business strategy', and 'functional strategy' - was conducted from an exploratory perspective to identify academic articles and other publications that provide the most relevant content and research on strategy. This review followed an integrative or critical review approach with the aim of assessing, critiquing, and synthesising the literature on strategy and the four strategy levels to enable the development of new theoretical frameworks and perspectives (Snyder, 2019). However, business research is still fragmented and interdisciplinary; thus, a more structured literature review is relevant as a methodology, as this could accelerate the assessment of collective evidence in business research and close the existing knowledge gaps (Snyder, 2019). The literature review approach that was followed enabled the selection of literature that contained a substantive perspective on strategy and that covered any of the four different levels of strategy identified above. The integrative review approach (see Figure 4) was to undertake a manual filtering of articles, which involved identifying, appraising, and synthesising all relevant articles/publications (Centobelli et al., 2020). This process began with selecting filtered papers from Google Scholar, using a keywords analysis based on strategy in general and on the four different levels of strategy; thus all articles with any of these four strategy levels were selected and filtered further, based on a content analysis of each of the papers, looking at the relevance and depth of their content on the study subject. As an exploratory review, the Google Scholar database was used because of its wider reach of articles and publications, which includes academic articles, theses, books, conference papers, and other non-academic articles (Falagas et al., 2008; Orduna Malea et al., 2017). The citation of the articles/publications was also considered in the selection process, as this is an important factor in determining the level of the recognition, impact, and/or influence of the selected articles/publications by other researchers or authors (Archambault & Gagné, 2004).

A total of 65 academic journal articles and other forms of publications were selected that had content to support the review of the four levels of strategy, strategy in general, and the strategy definitions. In 10 instances, a selected article/publication had content that was recognised as being in more than one of the four levels of strategy, strategy in general, and/or the strategy definitions. Thus, those articles/publications were counted in the respective strategy level/category in which they provide influence or relevant content. Table 2 highlights the statistics that have been briefly described in this section.

Though a relatively higher number of papers were published and selected under the general subject of strategy as well as on the definition of strategy, not as many papers were published that were selected specifically on corporate strategy, business strategy, and functional strategy. There were many citations for business strategy and functional strategy because of the article by Porter (1996), 'What is strategy?', which had a very high number of citations -in excess of 16,000. A large number of the papers selected for this review were published early in the 21st century period, while very few were selected from the late 20th century period. Of the four levels of strategy, grand strategy had the highest number of papers selected (12); however, the total number of citations of these papers was the lowest, possibly as a result of this level of strategy being in its infancy from a definition perspective, compared with the other levels of strategy that have been discussed and defined for longer.

4. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to develop an understanding of the definition of strategy to align its use in business and public policy settings, and to connect grand strategy to the other levels of strategy. To achieve this aim, the four levels of strategy (Figure 3) were defined; and it was shown how they relate to each other. The review also indicated that the different levels of strategy are interlinked and depend on one another (Hofmann, 2010).

Grand strategy was defined as a plan for a country or a regional block to achieve its set objectives in relation to the prevailing geopolitics and its desired economic benefit (Balzacq et al., 2019). The review showed that grand strategy has been practised for a long time; however, it has not been commonly defined for the various public policy settings in which it is used or that contribute to its formulation. Thus, it has not been holistically positioned against the other levels of strategy. However, this paper has positioned grand strategy with the other strategy levels, as shown in Figure 3. The literature review also showed that grand strategy is most often positioned as relating to foreign policy; thus, it mostly adopts an external perspective -that of communicating how a nation is positioned against other countries - and does not focus on how the country's foreign policy stance influences its internal aspects. The understanding and consideration of grand strategy as it relates to the other levels of strategy is important for policy-makers, business executives, consultants, and society at large. From a policy-maker's perspective, it is important to set policies with a view to how they will be implemented, to consider the fit of the combination of policies that are adopted, and also to consider how they impact business and society, since the collective position of these policies determines the grand strategy of the respective region or country. The GDP of a country is the most common, and somewhat standardised, measure of performance in order to compare performance across countries and also to project their respective citizens' levels of prosperity (Datta, 2011). While it is not a perfect measure, it is the most widely used, and so it can also be used to assess the level of success of the respective grand strategies that regions or countries adopt.

Corporate strategy has been defined as a process of determining what businesses to pursue and how they are managed (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2007; Pidun, 2019; Feldman, 2020), whereas business strategy is applicable to single stand-alone businesses or separate identifiable business units. Thus, business strategy is how an organisation or business unit competes in a specific market (Bowman & Ambrosini, 2007; Pidun, 2019), while corporate strategy is influenced by the corporate ambition that would have been determined through the mission and vision of the organisation. In determining which businesses to pursue, it is important for the organisation to be aware of the grand strategies of the region and/or country from which it operates or in which it intends to operate, as these would influence the achievement of the corporate strategies it has adopted. Business strategy is primarily concerned with the achievement of a competitive advantage (Pidun, 2019). Business strategy, just like corporate strategy, is also supposed to have a long-term focus. To position business strategy better in relation to corporate strategy: the business strategy is foundational to achieving the corporate strategy. This is because the individual businesses in a portfolio of businesses (which would have been determined by the corporate strategy) are each supposed to deliver on their goals and objectives in order to contribute to the overall achievement of the corporate strategy. The literature review showed that both corporate strategy and business strategy are very mature in their definitions and adoption in business.

Functional strategy was defined as the plans and choices set by divisions or departments within an organisation, such as finance, marketing, human resources (HR), information technology (IT), facilities management (FM), procurement, and research and development, to achieve the respective functions' goals and objectives in support of the delivery of the business strategy (Connor, 2001; Caglar et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2014). Functional strategy is also commonly known as 'operational strategy'. Operational or functional strategies are normally focused on the short term; thus their planning time horizon ranges from about a year to two years. An interesting perspective, following the review, is that only a limited academic literature defines functional strategy.

From a grand strategy perspective, developing countries would benefit from having well-defined grand strategies (Balzacq et al., 2019) in order to achieve the highest level of competitiveness and to ensure that their national interests are well-defined as they interact and trade with other nations (Delgado et al., 2012). This would also enable the communication of their national interests to key stakeholders, and align the nation's interests with the corporate strategies developed by organisations that operate within their borders or by those intending to do business or operate within their borders.

Both business and public policy settings develop strategies to achieve success; however, the term 'strategy' is defined quite differently across these settings (Markides, 2004; Vermeulen, 2017; Mishra et al., 2017). Having an aligned definition of strategy and of its use would be helpful for various stakeholders in communicating the strategy's intent and thereafter its implementation. Over and above the benefit of alignment, this would facilitate the better allocation of resources in the process of implementing the strategy. A strategy model to assist practitioners in the formulation of their strategies is presented in Figure 5.

A review of key strategy definitions was presented and analysed, as shown in Table 1. In the context of this review, on the basis of Figure 5, strategy is ultimately about how an organisation moves from its current position to a desired future position within the confines of its mission, vision, capabilities, and environment (Skrt & Antoncic, 2004; Phillips, 2011; Box, 2011; Grundy, 2012). And the 'how' is informed by the choices it makes about (i) who the customers are and (ii) what products and services to offer. The choices that determine the preferred strategy have to be those that enable the organisation to achieve the most benefit from the combination of strategic options available to it, taking into consideration the fit of the combination of chosen options (Porter, 1996; Whittington, 2001; Jarzabkowski & Balogun, 2009). This view of strategy would be suitable for all organisations, institutions, and/or countries, since it is simple to understand and would enable them to consider their desired future, taking into account the key aspects of their organisations or institutions, such as their mission, vision, capabilities, and environment. The 'how' cannot be determined if the desired future state has not been set; and the future state needs to be set within the confines of the mission, which states the organisation's purpose, or what the country intends to achieve for its citizens. The environment has to be taken into account in determining both the desired future state and the 'how', as it can influence the achievement of both factors.

For an institution in a public policy setting, which will likely have a separation between the customer and the recipient of the products or services, a different question can be posed:

Who are we meant to serve? rather than 'Who are the customers? - or the questions can be asked in combination. An understanding of the environment is a key outcome of any strategy development process, as it allows organisations and/or countries to understand their competitive landscape and the factors to consider in order to achieve their goals and objectives (Ungerer, 2019). Whereas the mission, vision, and capabilities will guide the organisations and/or countries in what they can and cannot do.

5. CONCLUSION

Having developed a theoretical model to define strategy in the light of a review of the literature, this study (i) provides a theoretical framework to assist organisations in business and various public policy settings to develop and define their strategies; (ii) assists in creating an alignment in business and public policy settings in the use of the term 'strategy'; and (iii) provides a theoretical positioning of grand strategy as it relates to the other levels of strategy: corporate strategy, business strategy, and functional strategy.

In the context of this review, strategy has been defined as how an organisation moves from its current position to a desired future position within the confines of its mission, vision, capabilities, and environment (Skrt & Antoncic, 2004; Box, 2011; Phillips, 2011; Grundy, 2012); and the 'how' is informed by the choices made about (i) who the customers are and/or who you are meant to serve; and (ii) what products and services to offer. The choices that determine the preferred strategy have to be those that enable the organisation to achieve the most benefit from the combination of strategic options available to it, taking into consideration the fit of the combination of chosen options (Porter, 1996; Whittington, 2001; Jarzabkowski & Balogun, 2009). Grand strategy was defined as a plan for a country or a regional block to achieve its set objectives in relation to the prevailing geopolitics and its desired economic benefit (Balzacq et al., 2019). It was also shown that it is important to consider grand strategy when formulating and implementing corporate strategy and business strategy.

The main limitation faced in conducting this review was using Google Scholar as the sole database for sourcing articles. Expanding the number of databases might have enabled the identification and selection of a much wider set of articles for consideration in this review. Further research in this focus area is needed, especially in providing a common and widely accepted definition of strategy, as well as positioning grand strategy and finding out how it impacts corporate strategy and business strategy. Further research to elaborate on functional strategy is also necessary, as only a limited number of academic studies comprehensively define functional-level strategy.

REFERENCES

Ackermann, F. & Eden, C. 2011. Making strategy: mapping out strategic success. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Acs, Z.J. & Szerb, L. 2007. Entrepreneurship, economic growth and public policy. Small Business Economics, 28(2):109-122. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9012-3]. [ Links ]

Alkhafaji, A. & Nelson, R.A. 2013. Strategic management: formulation, implementation, and control in a dynamic environment. New York: Routledge. [https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203862582]. [ Links ]

Archambault, É. & Gagné, É.V. 2004. The use of bibliometrics in the social sciences and humanities. Montreal: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRCC), 161-69. [Internet: http://www.science-metrix.com/pdf/SM_2004_008_SSHRC_Bibliometrics_Social_Science.pdf; downloaded on 2021-03-18]. [ Links ]

Balzacq, T., Dombrowski, P. & Reich, S. 2019. Is grand strategy a research program? a review essay. Security Studies, 28(1):58-86. [https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2018.1508631]. [ Links ]

Bowman, C. & Ambrosini, V. 2007. Firm value creation and levels of strategy. Management Decision, 45(3):360-371. [https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740710745007]. [ Links ]

Bowman, E.H. & Helfat, C.E. 2001. Does corporate strategy matter? Strategic Management Journal, 22(1):1-23. [https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200101)22:1<1::AID-SMJ143>3.0.CO;2-T]. [ Links ]

Box, T.M. 2011. Small firm strategy in turbulent times. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 10(1):115. [Internet: https://www.proquest.com/openview/8296ee636e474ef5213818d29cac066e/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=38745; downloaded on 2018-03-19]. [ Links ]

Cady, S.H., Wheeler, J.V., DeWolf, J. & Brodke, M. 2011. Mission, vision, and values: what do they say? Organization Development Journal, 29(1):63-78. [Internet: https://www.proquest.com/openview/d3b8f1af1910e2d7e9e693339926a4d1/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=36482; downloaded on 2019-12-20]. [ Links ]

Caglar, D., Kapoor, N. & Ripsam, T. 2013. The new functional agenda: how corporate functions can add value in a new strategic era. [Internet: https://www.strategyand.pwc.com/gx/en/insights/2002-2013/functional-agenda/strategyand-the-new-functional-agenda.pdf; downloaded on 2021-02-02]. [ Links ]

Cambridge Dictionary. 2008. Cambridge advanced learner's dictionary. 4th ed. Cambridge University Press [ Links ]

Centobelli, P., Cerchione, R., Chiaroni, D., Del Vecchio, P. & Urbinati, A. 2020. Designing business models in circular economy: a systematic literature review and research agenda. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(4):1734-1749. [https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2466]. [ Links ]

Chandler, A.D. 1990. Strategy and structure: chapters in the history of the industrial enterprise. Vol. 120. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Cherp, A., Watt, A. & Vinichenko, V. 2007. SEA and strategy formation theories: from three Ps to five Ps. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 27(7):624-644. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2007.05.008]. [ Links ]

Chimucheka, T. 2013. Overview and performance of the SMMEs sector in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(14):783-795. [https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n14p783]. [ Links ]

Connor, T. 2001. Product levels as an aid to functional strategy development. Strategic Change, 10(4):223-237. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.527]. [ Links ]

Datta, S. ed. 2011. Economics: making sense of the modern economy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Delgado, M., Ketels, C., Porter, M.E. & Stern, S. 2012. The determinants of national competitiveness (No. w18249). National Bureau of Economic Research. [https://doi.org/10.3386/w18249]. [ Links ]

Dixit, A. 2014. Strategy in history and (versus?) in economics: a review of Lawrence Freedman's strategy: a history. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(4):1119-1134. [https://doi.org/10.1257/iel.52.4.1119]. [ Links ]

Fagerberg, J., Srholec, M. & Knell, M. 2007. The competitiveness of nations: why some countries prosper while others fall behind. World Development, 35(10):1595-1620. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.worlddev.2007.01.0041. [ Links ]

Falagas, M.E., Pitsouni, E.I., Malietzis, G.A. & Pappas, G. 2008. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. The FASEB Journal, 22(2):338-342. [https://doi.org/10.1096/fi.07-9492LSF]. [ Links ]

Favaro, K. 2015. Defining strategy, implementation, and execution. Harvard Business Review 3. [Internet: https://hbr.org/2015/03/defining-strategy-implementation-and-execution; downloaded on 2020-03-21]. [ Links ]

Feaver, P. 2009. What is grand strategy and why do we need it. Foreign Policy, 8. [Internet: https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/04/08/what-is-grand-strategy-and-why-do-we-need-it/; downloaded on 2021-02-12] [ Links ]

Feldman, E.R. 2020. Corporate strategy: past, present, and future. Strategic Management Review, 1(1):179-206. [https://doi.org/10.1561/111.00000002]. [ Links ]

Fletcher, M. & Harris, S. 2002. Seven aspects of strategy formation: exploring the value of planning. International Small Business Journal, 20(3):297-314. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242602203004]. [ Links ]

Freedman, L. 2015. Strategy: a history. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Glaister, K.W. & Falshaw, J.R. 1999. Strategic planning: still going strong? Long Range Planning, 32(1):107-116. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(98)00131-9]. [ Links ]

Grant, R.M. 2003. Strategic planning in a turbulent environment: evidence from the oil maiors. Strategic Management Journal, 24(6):491-517. [https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.314]. [ Links ]

Grundy, T. 2012. Demystifying strategy: how to become a strategic thinker. London: Kogan Page Publishers. [ Links ]

Hassel, A. 2015. Public policy. In: Wright, J., ed., International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Elsevier. 569-575. [https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.75029-X]. [ Links ]

Hofmann, E. 2010. Linking corporate strategy and supply chain management. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 40(4):256-276. [https://doi.org/10.1108/09600031011045299]. [ Links ]

Huggins, R. & Izushi, H. 2015. The competitive advantage of nations: origins and journey. Competitiveness Review. [https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-06-2015-0044]. [ Links ]

Jarzabkowski, P. & Balogun, J. 2009. The practice and process of delivering integration through strategic planning. Journal of Management Studies, 46(8):1255-1288. [https://doi.org/10.1111/i.1467-6486.2009.00853.x]. [ Links ]

Johnson, G., Whittington, R., Scholes, K., Angwin, D. & Regner, P. 2014. Exploring strategy text & cases. London: Pearson Higher Ed. [ Links ]

Karagiannis, N., & Madid-Sadiadi, Z. 2012. A new economic strategy for the USA: a framework of alternative development notions. In Forum for Social Economics, 41 (2-3):131-165. Routledge. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s12143-011-9094-9]. [ Links ]

Maiama, N.S. & Magang, T. 2017. Strategic planning in small and medium enterprises (SMEs): a case study of Botswana SMEs. Journal of Management and Strategy, 8(1):74-103. [https://doi.org/10.5430/i ms.v8n1p74]. [ Links ]

Markides, C. 2004. What is strategy and how do you know if you have one? Business Strategy Review, 15(2):5-12. [https://doi.org/10.1111/i.0955-6419.2004.00306.x]. [ Links ]

Mintzberg, H. 1987. The strategy concept I: five P's for strategy. California Management Review, 30(1):11-24. [https://doi.org/10.2307/41165263]. [ Links ]

Mintzberg, H. 1994. The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harvard Business Review, 72(1):107-114. [Internet: https://hbr.org/1994/01/the-fall-and-rise-of-strategic-planning; downloaded on 2018-02-12]. [ Links ]

Mintzberg, H. & Waters, J.A. 1985. Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3):257-272. [https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250060306]. [ Links ]

Mishra, S.P., Mohanty, B., Mohanty, A.K. & Dash, M. 2017. Approaches to strategy: a taxonomic study. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, 15(4):620-630. [Internet: https://www.serialsjournals.com/abstract/70097ch49f-subratpmishra.pdf; downloaded on 201910-15]. [ Links ]

Mohajan, H. 2017. An analysis on BCG growth sharing matrix. International Journal of Business and Management Research, 2(1):1-6. [Internet: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/84237/1/mpra_paper_84237.pdf; downloaded on 2020-11-09]. [ Links ]

Needle, D. & Burns, J. 2010. Business in context: an introduction to business and its environment. Boston: SouthWestern Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Neugebauer, F., Figge, F. & Hahn, T. 2016. Planned or emergent strategy making? exploring the formation of corporate sustainability strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 25(5):323-336. [https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1875]. [ Links ]

Nicholson, P. 1977. What is politics: determining the scope of political science. Il Politico:228-249. [Internet: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43208204; downloaded on 2021-03-02]. [ Links ]

O'Regan, N. & Ghobadian, A. 2007. Formal strategic planning: annual raindance or wheel of success? Strategic Change, 16(1-2):11-22. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.777]. [ Links ]

Orduña Malea, E., Martín-Martín, A. & Delgado-López-Cózar, E. 2017. Google Scholar as a source for scholarly evaluation: a bibliographic review of database errors. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 40(4):1-33. [https://doi.org/10.3989/redc.2017.41500]. [ Links ]

Oxford English Dictionary Online. 2018. Strategy. [Internet: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/strategy; downloaded on 2018-02-27]. [ Links ]

Phillips, L.D. 2011. What is strategy? Journal of the Operational Research Society, 62(5):926-929. [https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2010.127]. [ Links ]

Pidun, U. 2019. Corporate strategy: theory and practice. Berlin: Springer. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-25426-1]. [ Links ]

Popescu, I. 2017. Emergent strategy and grand strategy: how American presidents succeed in foreign policy. Baltimore, Maryland: JHU Press. [ Links ]

Porter, M.E. 1980. Competitive strategy: techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Porter, M.E. 1989. From competitive advantage to corporate strategy. In Readings in strategic management. London: Palgrave, 234-255. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20317-8 17]. [ Links ]

Porter, M.E. 1990. The competitive advantage of nations. Harvard Business Review, 68(2):73-93. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-11336-1]. [ Links ]

Porter, M.E. 1996. What is strategy? Harvard Business Review, 74(6):61-78. [Internet: https://hbr.org/1996/11/what-is-strategy; downloaded on 2018-02-21]. [ Links ]

Pretorius, M. & Maritz, R. 2011. Strategy making: the approach matters. Journal of Business Strategy, 32(4):25-31. [https://doi.org/10.1108/02756661111150945]. [ Links ]

Redlbacher, F. 2020. Meetings as organizational strategy for planned emergence. In Managing meetings in organizations. Emerald Publishing Limited, (20):251-273. [https://doi.org/10.1108/S1534-085620200000020018]. [ Links ]

Ronda-Pupo, G.A. & Guerras-Martin, L.Á. 2012. Dynamics of the evolution of the strategy concept 1962-2008: a co-word analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 33(2):162-188. [https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.948]. [ Links ]

Rumelt, R.P. 2012. Good strategy/bad strategy: the difference and why it matters. Strategic Direction, 28(8) [https://doi.org/10.1108/sd.2012.05628haa.002]. [ Links ]

Sims, J., Powell, P. & Vidgen, R. 2016. A resource-based view of the build/buy decision: emergent and rational stepwise models of strategic planning. Strategic Change, 25(1):7-26. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2044]. [ Links ]

Skrt, B. & Antoncic, B. 2004. Strategic planning and small firm growth: an empirical examination. Managing Global Transitions, 2(2):107-122. [Internet: https://www.fm-kp.si/zalozba/ISSN/1581-6311/2107-122.pdf; downloaded on 2018-02-18]. [ Links ]

Snyder, H. 2019. Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104:333-339. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039]. [ Links ]

Thompson, C., Bounds, M. & Goldman, G. 2012. The status of strategic planning in small and medium enterprises: priority or afterthought? The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 5(1):34-53. [https://doi.org/10.4102/sajesbm.v5i1.26]. [ Links ]

Ungerer, M. 2019. Conceptualising strategy-making through a strategic architecture perspective. Management, 7(3):169-190. [https://doi.org/10.17265/2328-2185/2019.03.001]. [ Links ]

Ungerer, M., Ungerer, G. & Herholdt, J. 2016. Navigating strategic possibilities: strategy formulation and execution practices to flourish. Midrand, SA: KR Publishing. [ Links ]

Vermeulen, F. 2017. Many strategies fail because they're not actually strategies. Harvard Business Review. [Internet: https://hbr.org/2017/11/many-strategies-fail-because-theyre-not-actually-strategies; downloaded on 2021-11-09]. [ Links ]

Watkins, M. 2007. Demystifying strategy: the what, who, how, and why. Harvard Business Review, 10. [Internet: https://hbr.org/2007/09/demystifying-strategy-the-what; downloaded on 2018-02-21]. [ Links ]

Whittington, R. 2001. What is strategy and does it matter? 2nd ed. Hampshire: Cengage Learning EMEA. [ Links ]

Wolf, C. & Floyd, S.W. 2017. Strategic planning research: toward a theory-driven agenda. Journal of Management, 43(6):1754-1788. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313478185]. [ Links ]