Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.19 no.1 Meyerton 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcm20141.147

Drivers of and barriers to green manufacturing in South Africa

Suné Du PlooyI; Kobus NeethlingII; Andries NelIII; Jacobus Daniel NelIV,*

IDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: u04462892@tuks.co.za; ORCID: https://orcid.orq/0000-0003-1295-7793

IIDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: kobus.neethling@tuks.co.za; ORCID: https://orcid.orq/0000-0003-1339-7126

IIIDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: u16031025@tuks.co.za; ORCID: https://orcid.orq/0000-0003-1155-5709

IVDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Email: danie.nel@up.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.orq/0000-0003-3061-3564

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: Green supply chain management (GSCM) integrates environmental thinking into supply chain management (SCM) processes. From a manufacturing firm's perspective, GSCM includes inbound GSCM, green manufacturing (GM) and outbound GSCM. Gm optimisation depends on integrating and optimising the 'green' processes upstream, within and downstream of the manufacturing firm. Previous research highlights the internal and external drivers firms use to implement GM practices, but also cautions against specific barriers that may hinder GM implementation. The purpose of the study was to examine internal and external drivers of and barriers to GM from a South African perspective

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: A generic qualitative research design was used to collect data using semi-structured interviews with managers and/or owners from eight manufacturing firms. Four participants from multinational corporations (MNCs), and four participants from small or medium-sized enterprises (SME) were interviewed

FINDINGS: The most prominent internal drivers of GM were a socio-cultural responsibility to be green, top management commitment, an economic benefit that may be gained and a positive corporate image resulting from GM practices. Customers and suppliers were the biggest external drivers, while financial constraints and technology were the biggest barriers. MNCs had more drivers of and barriers to GM implementation than SMEs did

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: Due to the varying nature of products, industries and countries, a generic list of drivers and barriers cannot be compiled for all firms. Therefore, firms need to be acutely aware of these characteristics to identify relevant GM drivers and barriers

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: Top management should create a corporate culture to drive their GM practices from within the firm. They should emphasise their socio-cultural responsibility and the economic benefits of GM. In addition, managers should collaborate more with supply chain partners and be aware of other relevant external drivers. Financial constraints and technological barriers need to be overcome

JEL CLASSIFICATION: N67; O14; Q56

Keywords: External green manufacturing drivers; Green manufacturing; Green manufacturing barriers; Green supply chain management Internal green manufacturing drivers.

1. INTRODUCTION

In its most basic form, a supply chain is a part of interconnected firms providing goods and services to end customers (Tsironis & Matthopoulos, 2015). Supply chain management (SCM) thus involves the integration and coordination of processes across the entire supply chain to meet and satisfy the needs of its end customers (Green et al., 2012). Environmental concerns have increased the internal and external pressures on firms to implement sustainable (or 'green') SCM practices across the entire supply chain (Vijayvargy et al., 2017), hence the concept of green supply chain management (GSCM). There are many definitions for GSCM (Dubey et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018), but for this article, GSCM can be explained as the integration of SCM with environmentally friendly practices (Srivastava, 2007; Nteta & Mushonga, 2021). Therefore, GSCM needs to be implemented within different processes such as purchasing, manufacturing, operations, warehousing, logistics and reverse logistics (Srivastava, 2007; Green et al., 2012; Hsu et al., 2013; Younis & Sundarakani, 2019). GSCM has thus become an important topic within SCM. It inherently addresses the impact of SCM practices on the environment (Gurtu et al., 2015). From this, it is evident that GSCM spans the entire supply chain and that green manufacturing (GM) is part and parcel of GSCM.

Recently, global manufacturers have also felt these pressures to implement GSCM and remain competitive within their industry (Garg et al., 2015; Shokri & Li, 2020). Factors contributing to these pressures include growing economies (and thus increased total demand for products), continuous environmental changes and the scarcity of energy and other resources to meet the increased demand (Shrivastava & Shrivastava, 2017; Shokri & Li, 2020). Therefore, GM practices include energy conservation, using greener materials and products, reducing waste, controlling emissions and protecting the planet (Chuang & Yang, 2014). Hence, manufacturing firms are continuously searching for opportunities to integrate environmentally friendly products and processes. They aim to reduce their environmental footprint while improving their competitive advantage (Rao & Holt, 2005; Chuang & Yang, 2014; Shokri & Li, 2020).

Various internal and external drivers enable firms to adopt GSCM and GM practices (Walker etal., 2008; Wu et al., 2011; Adebanjo etal., 2016). Internal drivers are identified as extensive factors within a firm influencing the supply chain, while external drivers are various stakeholders who are external to the firm but involved in its supply chain (Walker & Jones, 2012). Therefore, firms need to identify these internal and external drivers in order to implement them successfully (Malviya & Kant, 2017).

Internal GSCM drivers include, among others, top management support and having a corporate culture with a strategic intent to be green. Some firms are also driven by a socio-cultural responsibility. Another important internal driver is the economic benefit that may be achieved by implementing GSCM practices (Walker et al., 2008; Green et al., 2012; Walker & Jones, 2012; Hsu et al., 2013; Vijayvargy et al., 2017). External GSCM drivers involve various external sources and their role to drive firms to adopt green practices. These drivers include customers, suppliers and other stakeholders such as the government, general public and non-profit organisations (Vachon & Klassen, 2006; Green et al., 2012; Hsu et al., 2013; Younis & Sundarakani, 2019; Nteta & Mushonga, 2021). However, despite these drivers and their potential benefits, there are several barriers to implementing GSCM. To mention a few, GSCM appears to be timely and costly; it also seems to provide uncertain returns and may involve complex supply chain relationships. In addition, a lack of commitment to implementing GSCM or a lack of knowledge about GSCM practices may also be significant barriers to GM implementation (Green et al., 2012; Walker & Jones, 2012; Hsu et al., 2013; Vijayvargy et al., 2017; Nteta & Mushonga, 2021).

Recently, much research has been conducted to analyse the benefits of and barriers to implementing GM (Mittal & Sangwan, 2014; Malviya & Kant, 2017). Yet, the majority of the research was not done in developing countries, or the research that was done in developing countries, including South Africa, was limited in scope and nature (Hsu et al., 2013; Adebanjo et al., 2016; Niemann et al., 2016; Mamabolo et al., 2017). In fact, Hsu et al. (2013) suggest that further research should be conducted on GSCM drivers and barriers in developing countries such as South Africa. The manufacturing sector is undoubtedly important in developing countries, as it contributes to the economy by working closely with other sectors such as agricultural, mining, transport, retail and financial (Seth et al., 2018; Nteta & Mushonga, 2021). In addition, it seems as if GSCM implementation also has been lacking in developing economies (Tumpa et al., 2019). It would be interesting to see if this is also the case in South Africa.

Although some research has been done from a Southern African perspective, a literature gap exists in published studies on the drivers of and barriers to implementing GSCM practices from a South African manufacturing perspective. The purpose of this article is thus to report on some of the drivers of and barriers to GSCM implementation - specifically GM within the South African manufacturing industry. The study was guided by the following research questions:

• What are the internal drivers driving the implementation of GM practices in South Africa?

• What are the external drivers driving the implementation of GM practices in South Africa?

• What barriers are impeding the implementation of GM practices in South Africa?

The article aims to contribute by analysing GSCM practices within the South African context and how it applies to the manufacturing industry. The article tries to establish why firms are driven to implement GM practices. The article also looks at some barriers experienced by manufacturing firms from within the South African context and why these firms may seem reluctant to implement GM practices.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 A brief overview of manufacturing in South Africa

The manufacturing industry in South Africa plays a crucial part in the country's economy. However, it has recently experienced numerous challenges in achieving year on year growth. In December 2019, the manufacturing industry contributed about 14 percent to South Africa's gross domestic product, which is much lower than the 20 percent contributed in 1994 (Kassen, 2020). Numerous reasons can be attributed to the decline in the contribution made by the manufacturing industry. One reason may be that there has been a reduction in fixed capital stock in the manufacturing sector (StatsSA, 2020). Another reason is the under-utilisation of production capacities in some industries, resulting from a decrease in the demand for finished goods manufactured in South Africa and an increase in imported goods from foreign countries. Other factors that contributed to this under-utilisation were a lack of raw materials and skilled labour and an insufficient supply of electricity, which has hampered productivity in the manufacturing sector. Moreover, the emphasis of South African exports has moved from exporting manufactured goods to exporting raw materials and commodities (SAMI, 2020). From a macro-environmental perspective, South Africa has also experienced a decline in its economy and negative growth for three consecutive quarters preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, which also left a devastating impact on the economy. Despite this, the manufacturing sector continues to play a significant role in the South African economy. From a government perspective, increased emphasis has been placed on the manufacturing sector to be more environmentally friendly amidst increasing threats such as global warming (IDC, 2009; Malan et aí., 2011; Sibanda, 2019; SAMI, 2020; SARB, 2020; DFFE, 2021).

2.2 Theoretical foundation

From the introduction, it is evident that GM forms an integral part of GSCM. An analysis of several literature reviews on GSCM was done by, among others, Dhull and Narwal (2016), Tseng et aí. (2018), Vijayvargy et aí. (2017) and Herrmann et aí. (2021). Tseng et aí. (2018) reviewed literature in GSCM from 1998 to 2017 and conclude that there were numerous and widely defined GSCM practices, and drivers of and barriers to GSCM implementation across the entire supply chain. This was corroborated by Vijayvargy et aí. (2017) and Herrmann et aí. (2021). For the purposes of this research, GSCM practices were categorised as inbound GSCM practices linked to upstream suppliers, GM practices at the manufacturing firm and outbound GSCM practices linked to downstream customers. This categorisation also aligns with research done by Rao and Holt (2005). Therefore, the theoretical foundation of this study is based on the research conducted by these authors and is illustrated in Figure 1. The components of this theoretical foundation will be elaborated on as the article proceeds. Vijayvargy et al. (2017) state that research has established there is increased performance when GSCM practices are implemented across the supply chain (even though the cost-benefit trade-offs with GSCM implementation continue to be debated).

The theoretical foundation of the paper is thus built on two main pillars. Firstly, the practices of GSCM will be clarified by analysing GM practices, inbound GSCM practices and outbound GSCM practices. These inbound and outbound GSCM practices are important as they support GM initiatives (Mafini & Muposhi, 2017). Secondly, the internal and external drivers of and barriers to GM will be demarcated as they apply to the different GSCM practices.

When the researchers conducted a literature review to determine the drivers of and barriers to GSCM, it became evident that different drivers and barriers exist in different countries and across different industries. This is highlighted in an analysis done by Vijayvargy et al. (2017), who reported on studies in GSCM in different countries. It is corroborated by other studies (Walker & Jones, 2012; Nteta & Mushonga, 2021). Zhu and Sarkis (2006) found different main drivers of GSCM implementation in China and the United States of America (USA). For example, some of the inbound GSCM practices include green purchasing and suppliers' involvement in environmental practices. These practices were emphasised more in the USA and much less in China. Firms in the USA also emphasised investment recovery more than firms in China. Chinese firms were emphasising internal drivers, such as the eco-design of products and top management's commitment towards implementing GSCM practices, more than external drivers (Zhu & Sarkis, 2006). Seth et al. (2018) looked at the role of firm size and GSCM implementation in India. Although some of the same drivers were mentioned when compared to other studies, the drivers were not equally important and also varied when small or medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and larger firms were compared. For example, financial incentives/ assistance from government and top management commitment were the most important drivers for SMEs. On the other hand, the two most important drivers for large firms were top management commitment and pressures resulting from government, competition, communities and other supply chain needs (Seth et al., 2018). Similar findings are also corroborated by Walker and Jones (2012), who conducted a study in the United Kingdom and categorised the drivers and barriers into main categories. During their data collection, the authors observed that all the main drivers and barriers were mentioned by the different firms, but not all the firms mentioned all the drivers and barriers. They found that there was a wide variety of drivers and barriers across the different firms. This finding is in line with the other findings mentioned above.

The same conclusion was drawn from a study conducted in Bangladesh by Tumpa et al. (2019). Moreover, the number of drivers and barriers varied a lot across different studies. For example, Dhull and Narwal (2016) identified 41 drivers and 27 barriers, while Dube and Gawande (2016) identified only 14 barriers and Zhu et al. (2005) identified only 13 drivers. Malviya and Kant (2017) identified 35 drivers while Tumpa et al. (2019) identified 15 barriers. Thus, it seems that there is a wide discrepancy as to how many drivers and barriers exist.

However, upon further investigation, it was found that studies conducted by Dube and Gawande (2016), Walker and Jones (2012) and Zhu etal. (2005) (and several others) grouped some of the drivers and barriers under main categories, which explains why they identified less drivers and barriers. This approach was also used by Mvubu and Naude (2016), Niemann et al. (2016) and Nteta and Mashonga (2021), who conducted studies in South Africa and Mozambique. The literature review conducted for this study also focused on categorising the drivers of and barriers to GM implementation under main overarching categories.

2.3 Green supply chain management

Manufacturing firms are pressured to review their production processes to be more sustainable in the light of increased ecological issues such as the rapid depletion of resources, increased pollution levels, global warming and a decrease in ecological diversity (Walker et al., 2008; Cankaya & Sezen, 2018; Strydom et al., 2020). Therefore, firms need to be more sustainable or green across their supply chains. Thus, a green supply chain includes activities that aim to minimise environmental impacts across the entire supply chain. It then logically follows that GSCM integrates environmental thinking into SCM (Younis & Sundarakani, 2019).

GSCM practices promote internal efficiency and synergy through GM to the firm as well as to external firms both upstream and downstream of the firm (Rao & Holt, 2005). GSCM thus needs to consider not only upstream (or inbound) sourcing processes but also downstream (or outbound) transportation and distribution activities, and reverse logistics activities, to mention a few (Sundarakani et al., 2010; Younis & Sundarakani, 2019). These processes are confirmed by several authors who conducted research on GSCM (Rao & Holt, 2005; Wu et al., 2011; Vijayvargy et al., 2017; Tseng et al. 2018; Assumpção et al., 2019; Herrmann et al., 2021). The GSCM practices that form part of the focus of this article are illustrated in Figure 2.

It is also well documented that firms can benefit in multiple performance areas when implementing GSCM. These areas include a reduction in operational costs, an enhanced corporate image, increased customer satisfaction and the creation of more market opportunities (Diabat et al., 2013; Younis & Sundarakani, 2019). GSCM practices have served as an incentive for many firms to increase revenue and product innovation (Bogue, 2014).

2.3.1 Green manufacturing

Manufacturing plays a critical role in a firm's overall implementation of GSCM initiatives (Bogue, 2014; Cankaya & Sezen, 2018). When viewed from a manufacturing perspective, GM entails the integration of environmental thinking into SCM activities such as product design and manufacturing processes (Rao & Holt, 2005; Assumpção et al., 2019; Herrmann et al., 2021). GM thus entails specifically manufacturing products by using processes that minimise negative impacts on the environment. GM processes conserve energy and natural resources, are safe for employees, communities and consumers and are economically sound (Bogue, 2014; Niemann et al., 2016; Howard, 2019). GM practices aim to enhance various manufacturing techniques of firms to decrease levels of waste, thus reducing the cost of production (Ghazilla et al., 2015; Barzegar et al., 2018). Some of these initiatives include the prevention of pollution, thus enhancing cleaner production across the supply chain (for example, at the source and during the manufacturing process and distribution). Other initiatives include implementing green product designs that entail reducing waste and maximising the reuse and recycling of materials where possible (Rao & Holt, 2005; Nunes & Bennett, 2010). GM is thus interlinked with numerous green initiatives upstream and downstream of the manufacturer. GM will increase in the future due to an increase in demand for products to be produced sustainably (Bogue, 2014).

2.3.2 Inbound green supply chain management

It is clear that GM is intricately linked with upstream and inbound processes, such as green purchasing and suppliers' involvement in GSCM, which are two overarching themes discussed in the literature (Rao & Holt, 2005). If upstream suppliers do not implement GSCM and do not supply green materials, manufacturing firms will find it difficult to optimise GM practices. Green purchasing entails the integration of environmental concerns into the manufacturing firm's procurement processes and policies, which in turn specify the suppliers' responsibilities in terms of green practices (Rao & Holt, 2005; Vijayvargy et al., 2017). Supplier environmental involvement can be examined from two viewpoints: cooperating and collaborating with suppliers to be green and supplier mentoring (or supplier development), which includes mentoring programmes to help suppliers improve processes such as reducing emissions, monitoring their waste streams, setting up environmental programmes and supporting them with conservation of natural resources (Rao & Holt, 2005; Assumpção et al., 2019).

2.3.3 Outbound green supply chain management

For the purposes of this article, green outbound processes include engaging in initiatives such as implementing green packaging and marketing, implementing green distribution and managing reverse logistics (even though it can be argued that reverse logistics stretches across the supply chain). It aims to reduce waste by recycling and reusing materials, among other methods (Rao & Holt, 2005; Hsu et al., 2013; Cankaya & Sezen, 2018; Shokri & Li, 2020). From this, it can be derived that three of the main focus areas in the green outbound supply chain are green packaging, green distribution and reverse logistics (see Figure 2).

Briefly, green packaging is an initiative to reduce the direct effect of packaging on the environment (Chuang & Yang, 2014). Green distribution elements and activities include, among others, the analysis of environmentally friendly transportation infrastructures and types, and network conditions. It also includes analysing aspects such as distances travelled, fuel sources used (including quantities consumed) and the amount of carbon dioxide emissions with the aim of being more environmentally friendly (Rao & Holt, 2005; Cankaya & Sezen, 2018). Reverse logistics entails recovering discarded products, materials (including packaging materials) or equipment from downstream customers to decide how they could be reused, recycled (which may include being remanufactured) or disposed of to improve the firm's environmental performance (Rao & Holt, 2005; Hsu et al., 2013). GM's role in GSCM can only be optimised if these downstream (or outbound) activities also have a green focus.

2.4 Drivers of green manufacturing

GM drivers can be defined as the motivating factors behind firms' decisions to implement GSCM practices. Drivers can be either voluntary or mandatory (Govindan, 2015). To successfully implement GM drivers, firms need to focus on these drivers (Seth et al., 2018).

2.4.1 Internal drivers

An environmental sustainability strategy aims to improve a firm's competitive position within the market and requires commitment from all managerial levels to ensure the successful implementation and integration of the strategy (Rao & Holt, 2005; Green et al., 2012). It thus follows that GSCM and GM should be driven by the firm's top management and corporate culture. Another internal driver is when a firm has a clear GSCM strategy. With a strong strategic intent to implement GSCM practices, a firm can be driven to improve its internal processes and overall conditions to be greener and improve its ISO 14001 standards. Top management and corporate culture may also impact the extent to which employees are innovative and motivated to enhance GSCM practices (Hillary, 2004; Ghazilla et al., 2015).

GSCM practices and a green brand strategy may enhance a firm's image, which in turn may lead to a competitive advantage and increased sales. Firms can advertise that their products and services are green (Dhull & Narwal, 2016). A potential economic (or financial) benefit is thus also most certainly an internal driver, from not only an increased sales perspective but also a cost reduction perspective as the implementation of GSCM practices aims to reduce waste and cut costs by, for example, using less energy, water and other resources in the production process. The cost and liability of harmful material disposal are also reduced. An economic (or financial) benefit can also be gained when the economic conditions in a country are favourable and consumer spending is high (Rao & Holt, 2005; Zhu, 2013; Niemann et al., 2016; Barzegar et al., 2018; Thaib, 2020; Nteta & Mushonga, 2021). Another key internal driver is a firm's socio-cultural responsibility in which it feels obligated to implement GSCM practices to align with social expectations and norms (Walker et al., 2008; Green et al., 2012; Walker & Jones, 2012; Hsu et al., 2013). The main categories of key internal drivers of GM are illustrated in Table 1.

2.4.2 External drivers

From a manufacturing perspective, key external drivers of GM involve collaboration from various external parties such as suppliers (regarding, for example, raw material inputs) or customers to adopt GSCM practices. Customers have started raising questions regarding the products they consume and the associated environmental impact those products have during their product life cycle (Govindan, 2015; Thaib, 2020). The risk of customer criticism is also reduced if firms implement GM practices (Dhull & Narwal, 2016). Government incentives, regulations and penalties can also be external drivers of GM implementation. Direct and indirect competitors can also drive firms to implement GSCM practices, as they need to keep up with the innovative offerings of their competitors to remain competitive (Vachon & Klassen, 2006; Green et al., 2012; Hsu et al., 2013; Younis & Sundarakani, 2019). External drivers can also be other stakeholders such as the general public, non-profit organisations and even the media. The society or non-government organisations (NGOs) may request firms to provide environmentally friendly products and keep the environment clean (Dhull & Narwal, 2016). Technology can also be a driver of GM. New technologies can enable production with less pollution and waste and can be more efficient (Seth et al., 2018). Table 2 illustrates the key external driver categories of GM.

2.5 Barriers to green manufacturing

Barriers are described as hurdles that a firm must overcome to implement GSCM successfully (Dube & Gawande, 2016). These barriers require successful identification to help with the transition phase of incorporating GM practices (Zhu et al., 2005).

Financial constraints and the time needed before any return on investment (ROI) are two of the main barriers to GSCM implementation (Govindan et al., 2014; Dube & Gawande, 2016). Many firms are reluctant to take on significant initial investment costs, including new machinery and processes, and hiring and training new employees. These initial investments will most probably result in manufacturing downtime, which in turn impacts the firm's profit and market share - especially over the short-term (Dwyer, 2007; Niemann et al., 2016). Another contributing factor is the uncertainty surrounding technological innovations and changes. Managers are reluctant to invest in new technologies and struggle to justify investments in these technologies as the benefits have not yet been established for certain (Sangwan, 2011).

A lack of skills and/or knowledge about GM initiatives can be another internal barrier. Training is required to enhance knowledge and skills, and this may take time. From this, it can be derived that a lack of top management commitment can impede the entire implementation of GSCM practices. A committed top management promotes employee empowerment and involvement and creates a culture where GSCM practices will be prominent (Niemann et al., 2016).

Commitment from supply chain partners is the first external barrier identified and entails the commitment of key stakeholders throughout the entire supply chain (Govindan et al., 2014). Suppliers' commitment to a green supply chain cannot be overlooked and is a focal point in achieving a holistic end-to-end green supply chain. A lack of environmentally conscious suppliers can be a barrier for firms that want to engage in green practices (Wolf & Seuring, 2010). Suppliers may also be apprehensive about supplying green materials for reasons such as the complexity of implementing GSCM practices and not being knowledgeable about GSCM practices (Dhull & Narwal, 2016). Another reason behind lagging supplier commitment can be the lack of information sharing on the benefits of mutual commitment and incentive programmes to motivate green practice implementation (Massoud et al., 2010).

New technological and operational innovations remain unknown (or may not be available) to the firm's management for long periods (Mathiyazhagan et al., 2013). When firms are in a position to access new technologies, they may still have concerns about the timing of (and the time required) for implementation. In addition, there may be a reluctance to change and adopt GM initiatives. This reluctance may stem from a lack of skills, an unwillingness to change and even a fear of losing jobs (Mathiyazhagan et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2014). Government policies and regulations or a lack of support can also be barriers to GSCM implementation (Mittal & Sangwan, 2014; Dube & Gawande, 2016). Countries with strong policies and regulations can lead to firms struggling due to a lack of infrastructure or the high cost of monitoring compliance (Rutherfoord et al., 2000). Another barrier may be the absence of buy-in from other key stakeholders and the general public (Sangwan, 2011). There may also be a lack of demand for green products due to several reasons, including low consumer spending, a lack of awareness of the benefits of green products and also customers' preference to buy cheaper non-green products (Dhull & Narwal, 2016; Tumpa et al., 2019). A summary of the main barrier categories to GM implementation is provided in Table 3.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1 Research design

A generic qualitative research design was used to collect data using semi-structured interviews. The purpose of this qualitative research was to investigate how internal and external drivers drive the implementation of GM within South African manufacturing firms and the barriers the firms encounter in the implementation process.

3.2 Sampling

One participant from each of eight purposefully selected manufacturing firms was recruited to participate in this research study. All the participants were in the private sector and based in various locations throughout South Africa. Industries with different focus areas were purposefully selected. The participants were either the owner of (or a production manager at) an SME or a senior manager at a multinational corporation (MNC), as shown in Table 4. For the purpose of this article, an MNC is defined as a corporation that has business dealings in more than one country. SMEs can be defined in several ways. However, manufacturing SMEs are referred to here in a South African context where they have an annual turnover of between R10 million and R170 million and have between 10 and 250 employees (De Wet, 2019). Four participants were from MNCs, and the other four were from SMEs. Due to the COVID-19 restrictions, an adapted purposeful sampling method was used.

3.3 Data collection

The interviews were conducted online in a semi-structured format with open-ended questions to allow participants to reflect on their opinions and experiences and provide the researchers with a better understanding. Eight interviews were conducted using cloud platforms for video and audio conferencing due to the COVID-19 social distancing regulations imposed in 2020. A discussion guide was compiled from the literature review to guide the interview process. The questions focused on GSCM initiatives being implemented and covered five broad categories: internal and external drivers of GM, barriers to GM, inbound GSCM practices, GM practices and outbound GSCM practices. To ensure consistency and trustworthiness in general, some definitions were read to the participants (e.g. GSCM, inbound processes, GM, and outbound processes). The main questions are included in Appendix A. Probing questions were used to delve deeper in participants' responses. The discussion guide was pre-tested to test its validity and intent. Initial contact was made with all the participants by email, telephone and other social media platforms, during which the interview time and date were scheduled. An overview of the research was provided to each participant. The interviews lasted between 36 and 90 minutes and were recorded and transcribed within three days after the interview. All transcriptions were cross-referenced and verified to ensure data accuracy and integrity.

3.4 Data analysis

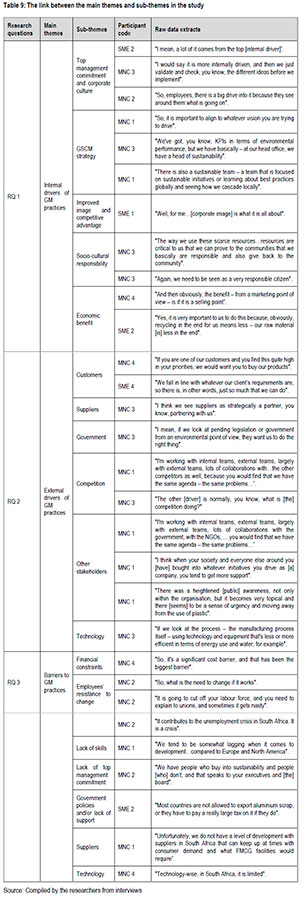

A thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. In this manner, data commonalities were identified throughout the transcriptions to group single codes into themes, linking directly with the research questions. A specific coding process was designed using ATLAS.ti software to allow for simplicity and uniformity in data coding and analyses. A more detailed overview of all the main themes, sub-themes and their connecting quotations from the interviews can be found in Table 9 (refer to Appendix B).

3.5 Trustworthiness

Throughout the study, steps were taken to preserve the trustworthiness and integrity of the data. Credibility was ensured by interviewing senior managers at MNCs and owners of (or production managers at) SMEs. By interviewing participants in these positions, the credibility of the findings was enhanced. Furthermore, more than one researcher interpreted the data, which resulted in similar codes and themes and contributed to the credibility and dependability of data interpretation. The discussion guide used in this research was inspired by previous research conducted in both developed and developing countries. This increased the data's dependability (or consistency) because similar studies have previously been conducted and were successful. Furthermore, the research objectives were stated very clearly and also communicated clearly to the participants.

To ensure conformability, the research reflects the opinions of the participants and not the researchers (Shenton, 2004). As already mentioned, the interviews were recorded to ensure all the information was obtained and available for further analysis. Using ATLAS.ti, all the codes, themes and sub-themes could be derived from what the participants said, thus ensuring that the findings conform to what the participants actually said. Transferability revolves around how the study can be replicated in a different situation. Transferability was ensured by collecting detailed information on the participant's role in the firm and the industries in which each firm operates. By using this information, researchers can use the data in different situations with similar characteristics. The research methodology is illustrated in Figure 3.

4. RESEARCH FINDINGS

4.1 Key internal drivers of green manufacturing

The first research question driving the focus of this article was: What are the internal drivers driving the implementation of GM practices in South Africa? Table 5 provides a summary of all the key internal drivers of GM mentioned by the research participants.

From Table 5, it is clear that six participants indicated that top management commitment and corporate culture was a strong internal driver. All four MNCs indicated this. A firm's top management commitment and corporate culture drive improved GSCM practice implementation (Ghazilla et aí., 2015). It was interesting to note that participants emphasised the role of top management's commitment and that corporate culture was driven from top management downwards through the firm. This drive from top management included the following:

• The development of teams or committees (to drive more GSCM efforts such as implementing green packaging);

• Emphasising cost reductions resulting from GSCM practices;

• Frequent communication with employees in the form of webinars, email content, training and education; and

• Implementing sustainability performance metrics and reports.

Half of the participants had a strategic intent to implement GSCM practices. What was interesting was that all these participants were MNCs. MNC 1 had a clear vision and sustainability plan, which included 17 goals set by the United Nations. The firm has a set strategy to reach targets aligned with these 17 sustainability goals. MNC 2 mentioned that sustainability was one of their four pillars of environmental stewardship. An example of a goal they pursue is to make use of solar energy to power their factories. MNCs 3 and 4 each had a global strategy in place to drive the implementation of GSCM practices. Each of the four MNCs had a head of sustainability who evaluates and monitors each plant's performance in implementing GSCM practices. However, not one SME had a strategic policy in place to drive their GSCM implementation.

Five of the eight participants acknowledged that corporate image drives GSCM implementation. This finding aligns with what Thaib (2020) suggests, namely that GSCM delivers an improved corporate image and thus customer perception. Although an improved corporate image was not the main driver, MNC 1 mentioned that brands linked to GSCM practices were doing better in the market. MNC 3 emphasised the importance of brand awareness and added that improving a brand's environmental image and reputation will increase customer support, allowing the brand to be successful in the market. One SME mentioned that corporate image was at the core of their business.

Socio-cultural responsibility has a twofold implication. Firstly, environmental conservation is the 'right' thing to do. It is good to refrain from damaging the environment. Secondly, it is a firm's responsibility to support the surrounding community (Hsu et al., 2013). All eight participants highlighted a socio-cultural responsibility to implement GSCM practices for environmental conservation and sustainable resource provision. All eight participants acknowledged a moral obligation as an internal driver of current and future GSCM practices. MNC 1 indicated that firms are forced to speed up their green initiatives to use natural resources responsibly. MNC 3 mentioned that it was driven to conserve natural resources and especially reduce the amount of water used in the manufacturing process. This drive was either within the firm or to assist upstream suppliers (for example, farmers) with products that reduce water usage and ensure the sustainability of their manufacturing activities.

Three MNCs and two SMEs mentioned an economic benefit that could be gained from implementing GM practices. MNC 1 acknowledged that the sales of brands linked to GSCM practices were increasing. MNC 3 also said that sales would increase if they manufactured green products. MNC 4 stated that they received more support and resources from their headquarters if they implemented GSCM practices. MNC 3 and MNC 4 were also using recycled materials to reduce their input costs and thus increase their profits. The interesting exception from an MNC perspective was the comments made by MNC 2. MNC 2 was following a low-cost strategy and their profit margins were small due to the nature of their products.

MNC 2 argued that due to the high implementation costs of GM, they would not gain an economic benefit from implementing GM at this stage. SME 1 gained an economic benefit from implementing GM practices because its downstream customers (farmers) could reduce their input costs, such as water usage, when using green products produced by SME 1. SME 2 used recycling effectively to reduce their raw material costs.

4.2 Key external drivers of green manufacturing

The second research question asked: What are the external drivers driving the implementation of GM practices in South Africa? Table 6 summarises the key external drivers of GM that were mentioned by the research participants.

Table 6 shows that all the MNCs indicated that customer pressures or requests were among the top external drivers for firms to adopt GSCM practices. Customers influenced their product designs, raw materials the MNCs used, production processes and waste management practices. SME 4 stated that due to the contractual nature of its business, it was dependent on what its customers wanted, hence the question mark in Table 6. If its customer wanted green products, SME 4 had an external drive to adhere to their request. However, if the customers did not require green products, there was no pressure or drive to implement GM practices.

SMEs 1, 2 and 3 indicated that they were driven more from a socio-cultural responsibility motive to ensure that their customers receive sustainable products through GSCM practices (for example, by reducing waste in their supply chains) rather than customers exerting pressure on them to implement GM practices. This highlights that the MNCs were more sensitive to customer pressures (and differentiating themselves through GSCM practices) than the SMEs.

All four MNCs mentioned that they had strategic partnerships with their suppliers - MNCs 1 and 3, especially, collaborated with their suppliers in, for example, mentorship programmes, supplier development and green purchasing. Suppliers were also compelled to submit reports concerning their GSCM practices. MNC 3 was also involved in research and development with their suppliers to try and reduce their environmental footprint by introducing innovative technologies in waste management. MNC 4 collaborated with their suppliers to design more environmentally friendly packaging. However, three of the SMEs had very little supplier involvement, and due to the size and nature of their businesses, they saw no further need to develop their supplier relationships. Therefore, when sourcing green materials from suppliers, SMEs did so to comply with certain regulations and not because they were driven to do so by their suppliers.

Three MNCs specifically mentioned the government as an external driver to implement GM practices. In contrast, three SMEs mentioned minimal governmental regulations and intervention concerning their GSCM practices. The SMEs mentioned that they aimed to reduce the usage of, for example, water and electricity and comply with audits. However, these regulations were not so severe as to drive them to implement GSCM practices or aggressively improve their green footprint.

The role that the government played as an external driver of the implementation of GSCM practices varied between industries and included regulations, levies, taxes and fines in terms of water sanitation, carbon emissions, dumping waste, pollution levels and the use of materials that were not environmentally friendly. With these legislations in place, firms are forced to be proactive to avoid paying levies or taxes and being fined, which would cut profits. However, MNC 1 mentioned that the government would contribute (and collaborate with firms) to solve humanitarian and environmental issues in the MNCs' local communities or provinces. It was mentioned by MNC 3 that the government would empower firms to 'do the right thing' and comply with legislation. Logically, MNCs have a larger environmental footprint and thus more potential to harm the environment. Therefore, it can be concluded quite logically that MNCs were monitored more closely than SMEs.

Competitors play a huge role in GSCM implementation, as manufacturers are keenly aware of what competitors implement to achieve GSCM. Three MNCs used competitive benchmarks to compare their green efforts against those of their competition. SMEs did not compare their GSCM practices to those of their competition but competed on aspects such as price and quality.

Three participants (two MNCs and one SME) mentioned the general public as an external driver. The two MNCs mentioned that the general public pressured them to, for example, reduce their carbon emission rates and lower their electricity usage and, specifically, their waste. The two MNCs also stated that NGOs play a role - not from an operational perspective, but rather as part of a community outreach programme - in the MNCs implementing green practices. The SME stated that it experienced pressure from its neighbouring community to reduce air pollution.

Four participants indicated technology as an external driver of GM implementation. Three of the four MNCs invested heavily in technologies to, for example, improve the eco-design of their products and reduce resources required or used during their manufacturing processes. One MNC emphasised time constraints and the importance of setting realistic return on investment (ROI) goals. One SME mentioned introducing equipment to reduce their overall air pollution and improve their overall business efficiencies.

4.3 Barriers to green manufacturing practices

The last research question focused on the barriers that impede the implementation of GM practices in South Africa. These barriers are listed in Table 7.

The main barrier impeding the implementation of GSCM practices was financial. All eight participants acknowledged that finances played a critical role in their inability to implement GSCM practices as they would like to. GM technologies often require significant financial investments. MNCs 2 and 4 highlighted the high costs of procuring green materials. On a positive note, MNC 1 mentioned that the cost of implementing GSCM practices was decreasing due to, among others, collaborative relationships with suppliers.

Closely linked to finances as a barrier was technology. Despite technology being considered a driver, it was also seen as a barrier to GSCM implementation. This highlights that drivers can also be barriers to GSCM implementation (and vice versa). MNC 2 used the following example to highlight technology as a barrier: MNC 2 was investigating the option of using electric vehicles for their logistics department; however, the technology and infrastructure in South Africa currently cannot support this initiative. In fact, technology as a barrier to implementing GSCM practices was corroborated by all four MNCs who, between them, mentioned that the implementation of technological solutions is an extremely costly and timely process. One MNC emphasised time constraints as a significant concern for technology implementation. Two participants mentioned that these technologies might exist in developed countries, but it would be too costly to import them into South Africa at this stage. A specific example mentioned was that if green packaging or technologies are available, then it takes time to reach South Africa, which delays deliveries to the end customer. The ripple effect on aspects such as inventory turns and cash-to-cash cycle times is obvious.

The state of the South African economy at the time of this article is not favourable to implementing expensive technological initiatives. In addition, labour markets and unions also pressure firms to avoid retrenchments. As a result, technologies such as robotics are often viewed as a threat, as they may eventually replace current employees. MNCs 1 and 2 mentioned that they must be aware of their employees' negative perceptions and resistance to implementing new technologies as part of their GSCM initiatives, as a negative perception could easily spill over into actions sabotaging the implementation of new technologies.

One large MNC mentioned that a lack of top management support was one of their biggest barriers to a full drive towards GSCM implementation. Ironically, this same MNC also mentioned top management support and corporate culture as an internal driver. The reason for this seeming discrepancy is found in the size of the MNC. Some members of the firm's top management favoured implementing GSCM practices, but other members - who were not convinced that implementing GSCM practices would ultimately lead to increased profits - were opposed. This internal conflict is a barrier to GSCM implementation.

The government (or government of a foreign country) can also be a barrier. For example, MNC 4 mentioned that it was impacted by the governmental restrictions laid down during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, MNC 1 stated that it had to pay increased taxes and its exports were restricted due to a dispute between the South African government and another government.

Three participants (MNCs 1 and 4 and SME 2) mentioned that suppliers were a barrier to implementing GSCM. The reason given was universal: there were not always enough suppliers who could support their green initiatives. MNC 1 and SME 2 were involved in supplier development programmes to address these issues, and MNC 4 mentioned that it wanted to be involved in supplier development programmes to educate their suppliers in the field of green practices. Two other participants (MNC 2 and MNC 3) mentioned that their firms had strategic partnerships with their suppliers and proactively worked towards common GSCM goals. These suppliers were not mentioned as barriers, which leads to potentially important conclusions.

5. CONCLUSION

5.1 General conclusions

The article aimed to report on some of the internal and external drivers that enable GSCM, specifically from a GM perspective within the South African manufacturing industry. The study was guided by three research questions - and to guide the conclusions that have been drawn, the researchers have provided a summary of the findings in Table 8.

The first research question focused on the internal drivers driving the implementation of GM practices in South Africa. A clear distinction could be made in terms of internal drivers for MNCs and SMEs, and it was evident that MNCs had more internal drivers (refer to Table 8). The research found that socio-cultural responsibility was the strongest internal driver of GSCM implementation. However, top management support and a corporate culture embracing GSCM was also a strong internal driver. The fact that GSCM practices preserve or enhance a firm's corporate image was also mentioned as a strong internal driver, and five participants mentioned that an economic benefit could be gained by implementing GSCM practices. This benefit could stem from either increased sales or reduced costs, or both. Only MNCs had a GSCM strategy in place.

The second research question focused on the external drivers that assist manufacturers in implementing GM practices. The main external drivers were suppliers, customers and technology. Supplier commitments to GSCM practices, the government and competition were strong external drivers for MNCs to implement GSCM practices. Although MNCs and SMEs alike had internal drivers driving them towards implementing GM practices (albeit that MNCs had more), the same could not be said for external drivers. MNCs (specifically those in the FMCG industry) had many more external drivers than SMEs driving them towards implementing GM practices (refer to Table 8). While MNCs had internal and external drivers, SMEs mostly had internal drivers.

The third research question focused on barriers that hinder the implementation of GM practices. It was also evident here that MNCs had more barriers to implementing GM practices. The main barriers mentioned were financial and technological. Technology could hinder GSCM implementation because of its large investments and uncertainties pertaining to its results and when the technologies would be replaced with newer ones. Some participants also mentioned that the government and suppliers could also be barriers.

Top management support to implement GSCM practices was also mentioned as a barrier by the largest MNC. From this statement, it could be concluded that very large firms may struggle to obtain buy-in from everybody in top management and that there may be more diverse viewpoints concerning GSCM practices, as seemed to be the case with MNC 2.

In conclusion, MNCs had more internal and external drivers of - but also more barriers to -GSCM practices. These findings align with what Younis and Sundarakani (2019) and Agan (2013) found: larger firms are in a more favourable position to implement GSCM practices, while smaller SMEs are often more concerned with surviving in competitive markets.

Upon closer analysis, another interesting conclusion could be drawn: the nature of the product or industry determines which drivers and barriers will be present when adopting GM practices (or not). For example, MNC 2 made it very clear that their first priority was to cut costs because they were competing in a market with low margins. The internal drive to implement GM practices was thus less for them than for the other MNCs. On the other hand, SME 1 was heavily involved in designing green products, thus their internal drive to be green (refer to Table 8). Lastly, SME 4 made it clear that they were flexible and guided by what their customers wanted. Therefore, they did not truly have an internal drive to be green except for the socio-cultural responsibility they felt.

Even though some interesting comparisons could be made, comparing these findings with those of research conducted in other countries was difficult and challenging. Numerous studies have found different drivers and barriers across different industries and countries (Walker & Jones, 2012; Niemann et al., 2016; Vijayvargy et al., 2017; Nteta & Mushonga, 2021). This made a comparison between countries very difficult. However, it did allow the researchers to come to a profound conclusion: the nature of a firm's products, the industry in which it operates and even the country where it is operational all have certain drivers and barriers. These drivers and barriers are not the same for all products and industries. Firms must be aware of this and identify the relevant drivers and barriers that apply to them.

5.2 Manaqerial implications

Several managerial implications were derived from the research. The findings clearly show that for MNCs, internal and external drivers played a role in GM implementation, but fewer barriers were observed. It must be noted, however, that the main barriers were significant and might have played a role in other barriers not being mentioned. From an MNC perspective, it can thus be recommended that manufacturers who want to strive to implement GSCM practices should identify and use internal and external GM drivers that are relevant to their products and the industries in which they operate. The socio-cultural responsibility drive can be used by top management to commit to and develop a corporate culture aimed at addressing GM practices. This can be done in conjunction with the development of strategic policies to further drive GSCM implementation. The benefits of an improved corporate image as seen by internal and external parties, which includes customers, must be emphasised and promoted. Firms should inform all relevant stakeholders across the supply chain of these benefits. A positive corporate image may be proactively enhanced by collaborating with other external supply chain partners implementing GSCM practices. Manufacturers can collaborate with suppliers to optimise upstream GSCM practices while also using their competitors as benchmarks. From a more macro-environmental perspective, it can be suggested that MNCs need to be aware of governmental incentives and/or regulations and also technological developments. It is recommended that MNCs be ready to seize opportunities that may arise as new technologies develop and become more accessible in terms of infrastructure and reduced financial commitments. Other opportunities, such as a favourable economy, may also help to overcome financial constraints.

From an SME perspective, it is recommended that emphasis must be placed on socio-cultural responsibility so that all firms in a supply chain, including SMEs, feel a moral obligation to implement GSCM practices. It is suggested that although there are substantial financial and technological barriers, SMEs can aim to implement more achievable GM practices, including reducing waste, recycling and reusing materials. GM initiatives should thus initially be driven from within the SME. SMEs had a much smaller focus on external drivers; however, it is recommended that incentives be provided to, for example, suppliers and supplier development programmes be suggested to get them more involved in GSCM practices.

5.3 Limitations of the study

The limitations of the study are threefold. The first limitation is that although meaningful data were obtained from the eight participants, which pointed findings to a specific direction, it cannot confidently be claimed that complete data saturation was obtained. Therefore, further research needs to be conducted to establish key findings and possible managerial implications. A second limitation resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions placed on researchers, which led to them not meeting face-to-face with the participants. This resulted in the researchers not being able to pick up on possible cues given by the participants during the interviews or probe to the extent they may have wanted to. The third limitation was mentioned earlier: due to the nature of the products, the industries in which firms operate and the countries in which they are operational, it is difficult to compare the drivers of and barriers to GM implementation between countries. Future research may focus on constituting a framework that can identify all relevant drivers and barriers from within a specific firm's context. The last recommendation for future research is to include some form of ranking between the drivers and barriers to determine which drivers (and barriers) are more significant within a specific industry or country.

REFERENCES

Adebanjo, D., Teh, P.L. & Ahmed, P.K. 2016. The impact of external pressure and sustainable management practices on manufacturing performance and environmental outcomes. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 36(9):995-1013. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-11-2014-0543]. [ Links ]

Agan, Y. 2013. Drivers of environmental processes and their impact on performance: a study of Turkish SMEs. Journal of Cleaner Production, 51:23-33. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.043]. [ Links ]

Assumpção, J.J., Campos, L.M.S., Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B., Jabbour, C.J.C. & Vazquez-Brust, D.A. 2019. Green supply chain practices: a comprehensive and theoretically multidimensional framework for categorization. Production, 29, e20190047. [https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6513.20190047] [ Links ]

Barzegar, M., Ehtesham, R.R. & Niknamfar, A.H. 2018. Analyzing the drivers of green manufacturing using an analytic network process method: a case study. International Journal of Research in Industrial Engineering, 7(1):61-83. [https://doi/10.22105/riej.2018.108563.1031]. [ Links ]

Bogue, R. 2014. Sustainable manufacturing: a critical discipline for the twenty-first century. Assembly Automation, 34(3):117-122. [https://doi.org/10.1108/AA-01-2014-012]. [ Links ]

Cankaya, S.Y. & Sezen, B. 2018. Effects of green supply chain management practices on sustainability performance. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 30(1):98-121. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-03-2018-0099]. [ Links ]

Chuang, S.P. & Yang, C.L. 2014. Key success factors when implementing a green-manufacturing system. Production Planning & Control, 25(11):923-937. [https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2013.780314]. [ Links ]

De Wet, P. 2019. The definitions of micro, small, and medium business have just been radically overhauled: here's how. [Internet: https://www.businessinsider.co.za/micro-small-and-medium-business-definaition-update-by-sector-2019-3; downloaded on 12 November 2021]. [ Links ]

Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment. 2021. About green economy. [Internet: https://www.dffe.gov.za/projectsprogrammes/greeneconomy/about#; downloaded on 12 November 2021]. [ Links ]

DFFE see Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment. [ Links ]

Dhull, S. & Narwal, M.S. 2016. Drivers and barriers in green supply chain management adaptation: a state-of-art review. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 4:61-76. [https://doi:10.5267/j.uscm.2015.7.003]. [ Links ]

Diabat, A., Khodaverdi, R. & Olfat, L. 2013. An exploration of green supply chain practices and performances in an automotive industry. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 68(1):949-961. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-013-4955-4] [ Links ]

Dube, A.S. & Gawande, R.R. 2016. Analysis of green supply chain barriers using integrated ISM-fuzzy MICMAC approach. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 23(6):1558-1578. [https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-06-2015-0057]. [ Links ]

Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A. & Papadopoulos, T. 2017. Green supply chain management: theoretical framework and further research directions. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 24(1):184-218. [https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-01-2016-0011]. [ Links ]

Dwyer, J. 2007. Unsustainable measures. Manufacturing Engineer, 86(6):14. [https://doi.org/10.1049/me:20070600]. [ Links ]

Garg, A., Lam, J.S.L. & Gao, L. 2015. Energy conservation in manufacturing operations: modelling the milling process by a new complexity-based evolutionary approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 108:34-45. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/i.jclepro.2015.06.0431. [ Links ]

Ghazilla, R.A.R., Sakundarini, N., Abdul-Rashid, S.H., Ayub, N.S., Olugu, E.U. & Musa, S.N. 2015. Drivers and barriers analysis for green manufacturing practices in Malaysian SME's: a preliminary findings. Procedia CIRP, 26:658-663. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2015.02.085]. [ Links ]

Govindan, K. 2015. Analyzing the drivers of green manufacturing with fuzzy approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 96:182-193. [https://doi.org/10.1016/uclepro.2014.02.054l [ Links ]

Govindan, K., Kaliyan, M., Kannan, D. & Haq, A.N. 2014. Barriers analysis for green supply chain management implementation in Indian industries using analytic hierarchy process. International Journal of Production Economics, 147:555-568. [https://doi.org/10.1016/uipe.2013.08.011. [ Links ]

Green, K.W., Zelbst, P.J., Meacham, J. & Bhadauria, V.S. 2012. Green supply chain management practices: impact on performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17(3):290-305. [https://doi.org/10.1108/135985412112271261. [ Links ]

Gurtu, A., Searcy, C. & Jaber, M.Y. 2015. An analysis of keywords used in the literature on green supply chain management. Management Research Review, 38(2):166-194. [https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-06-2013-01571. [ Links ]

Herrmann, F.F., Barbosa-Povoa, A.P., Butturi, M.A., Marinelli, S. & Sellitto, M.A. 2021. Green supply chain management: conceptual framework and models for analysis. Sustainability, 13,8127. [https://doi.org/10.3390/su131581271. [ Links ]

Hillary, R. 2004. Environmental management systems and the smaller enterprise. Journal of Cleaner Production, 12(6):561-569. [https://doi.org/10.1016/i.iclepro.2003.08.006l [ Links ]

Howard, M.C. 2019. Sustainable manufacturing initiative: a true public-private dialogue. [Internet: https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/45010349.pdf; downloaded on 1 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Hsu, C.C., Tan, K.C., Zailani, S.H.M. & Jayaraman, V. 2013. Supply chain drivers that foster the development of green initiatives in an emerging economy. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 33(6):656-688. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-10-2011-04011. [ Links ]

IDC see Industrial Development Corporation. [ Links ]

Industrial Development Corporation. 2009. Trends in South African manufacturing production, employment and trade. [Internet: https://www.idc.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Manufacturing-Trends-4th-Quarter-2009.pdf; downloaded on 25 May 20201. [ Links ]

Kassen, J. 2020. SA manufacturing sector sees its 7th month of growth declines. [Internet: https://ewn.co.za/2020/02/12/sa-manufacturing-sector-sees-its-7th-month-of-growth-declines; downloaded on 25 May 20201. [ Links ]

Kumar, V., Jabarzadeh, Y., Jeihouni, P. & Garza-Reyes, J. 2014. Learning orientation and innovation performance: the mediating role of operations strategy and supply chain. Supply Chain Management, (in press):57-82. [Internet: https://www-emerald-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/insight/content/doi/10.1108/SCM-05-2019-0209/full/html; downloaded on 10 April 20201. [ Links ]

Mafini, C. & Muposhi, A. 2017. The impact of green supply chain management in small to medium enterprises: cross-sectional evidence. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 11(0), a270. [https://doi.org/10.4102/jtscm.v11i0.270] [ Links ]

Malan, J., Steenkamp, E.A., Rossouw, R. & Viviers, W. 2011. Analysis of export and employment opportunities for the South African manufacturing industry. [Internet: http://www.tips.org.za/files/analysis_of_export_opportunities_for_sa_manufacturing-malan_steenkamp_rossouw_viviers.pdf; downloaded on 31 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Malviya, R.K. & Kant, R. 2017. Modeling the enablers of green supply chain management: an integrated ISM -fuzzy MICMAC approach. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 24(2):536-568. [https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-08-2015-00821. [ Links ]

Mamabolo, M.A., Kerrin, M. & Kele, T. 2017. Entrepreneurship management skills requirements in an emerging economy: a South African outlook. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 9(1):1-10. [https://doi.org/10.4102/saJesbm.v9i1.1111. [ Links ]

Massoud, M.A., Al-Abady, A., Jurdi, M. & Nuwayhid, I. 2010. The challenges of sustainable access to safe drinking water in rural areas of developing countries: case of Zawtar El-Charkieh, Southern Lebanon. Journal of Environmental Health, 72(10):24-31. [Internet: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26329050; downloaded on 13 October 2021]. [ Links ]

Mathiyazhagan, K., Govindan, K., NoorulHaq, A. & Geng, Y. 2013. An ISM approach for the barrier analysis in implementing green supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 47:283-297. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.10.0421. [ Links ]

Mittal, V.K. & Sangwan, K.S. 2014. Fuzzy TOPSIS method for ranking barriers to environmentally conscious manufacturing implementation: government, industry and expert perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Technology and Management, 17(1):57-82. [https://doi.org/10.1504/IJETM.2014.0594661. [ Links ]

Mvubu, M. & Naude, M.J. 2016. Green supply chain management constraints in the South African fast-moving consumer goods industry: a case study. Journal of contemporary management, 13:271-297. [ Links ]

Niemann, W., Kotze, T. & Adamo, F. 2016. Drivers and barriers of green supply chain management implementation in the Mozambican manufacturing industry. Journal of Contemporary Management, 13:977-1013. [ Links ]

Nteta, A. & Mushonga, J. 2021. Drivers and barriers to green supply chain management in the South African cement industry. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 15(0), a571. [https://doi.org/10.4102/jtscm.v15i0.5711 [ Links ]

Nunes, B. & Bennett, D. 2010. Green operations initiatives in the automotive industry: an environmental reports analysis and benchmarking study. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 17(3):396-420. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/146357710110493621. [ Links ]

Rao, P. & Holt, D. 2005. Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 25(9):898-916. [https://doi.org/10.1108/014435705106139561. [ Links ]

Rutherfoord, R., Blackburn, R.A. & Spence, L.J. 2000. Environmental management and the small firm: an international comparison. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 6(6):310-325. [https://doi.org/10.1108/135525500103627501. [ Links ]

SAMI see South Africa's Manufacturing Industry. [ Links ]

Sangwan, K.S. 2011. Development of a multi criteria decision model for justification of green manufacturing systems. International Journal, 5(3):285. [https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGE.2011.044239]. [ Links ]

SARB see South African Reserve Bank. [ Links ]

Seth, D., Rehman, M.A. & Shrivastava, R.L. 2018. Green manufacturing drivers and their relationships for small and medium (SME) and large industries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198:1381-1405. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.106]. [ Links ]

Shenton, A.K. 2004. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2):63-75. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201]. [ Links ]

Shokri, A. & Li, G. 2020. Green implementation of lean six sigma projects in the manufacturing sector. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 11(4):1-19. [https://doi.org/ http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJLSS-12-2018-0138]. [ Links ]

Shrivastava, S. & Shrivastava, R.L. 2017. A systematic literature review on green manufacturing concepts in cement industries. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 34(1):68-90. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-02-2014-0028]. [ Links ]

Sibanda, M. 2019. Prospects bleak for South Africa's manufacturing sector. [Internet: https://southerntimesafrica.com/site/news/prospects-bleak-for-south-africas-manufacturing-sector-2; downloaded on 25 May 2020]. [ Links ]

South Africa's Manufacturing Industry. 2020. South Africa's manufacturing industry. [Internet: https://www.southafricanmi.com/south-africas-manufacturing-industry.html; downloaded on 30 April 2020]. [ Links ]

South African Reserve Bank. 2020. Quarterly bulletin. [Internet: https://sec.report/Document/0001104659-20-044565/; downloaded on 14 October 2021]. [ Links ]

Srivastava, S. 2007. Green supply chain management: a state of the art literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 9:53-80. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00202.x]. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. 2020. Gross domestic product: first quarter 2020. [Internet: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0441/P04411stQuarter2020.pdf; downloaded on 21 October 2021]. [ Links ]

StatsSA see Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

Strydom, C., Meyer, N. & Synodinos, C. 2020. Generation y university students' intentions to become ecopreneurs in South Africa: a gender comparison. Journal of Contemporary Management, f7(Special-Edition-1):22-43. [https://doi.org/10.35683/jcm20034.74]. [ Links ]

Sundarakani, B., De Souza, R., Goh, M., Wagner, S. & Manikandan, S. 2010. Modelling carbon footprints across the supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, 128:43-50. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.01.018]. [ Links ]

Thaib D. 2020. Drivers of the green supply chain initiatives: evidence from Indonesian automotive industry. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 8(1):105-116. [http://dx.doi.org/10.5267/j.uscm.2019.8.002]. [ Links ]

Tseng, M., Islam, M.S., Karia, N., Fauzi, F.A. & Afrin, S. 2018. A literature review on green supply chain management: trends and future challenges. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 141:145-162. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.10.009]. [ Links ]

Tsironis, L.K. & Matthopoulos, P.P. 2015. Towards the identification of important strategic priorities of the supply chain network. Business Process Management Journal, 21(6):1279-1298. [https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-12-2014-0120]. [ Links ]

Tumpa, T.J., Ali, S.M., Rahman, M.H., Paul, S.K., Chowdhury, P. & Khan, S.A.R. 2019. Barriers to green supply chain management: an emerging economy context. Journal of Cleaner Production, 236, 117617. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117617]. [ Links ]

Vachon, S. & Klassen, R.D. 2006. Extending green practices across the supply chain: the impact of upstream and downstream integration. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 26(7):795-821. [https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570610672248]. [ Links ]

Vijayvargy, L., Thakkar, J. & Agarwal, G. 2017. Green supply chain management practices and performance: the role of firm-size for emerging economies. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 28(3):299-323. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-09-2016-0123]. [ Links ]

Walker, H. & Jones, N. 2012. Sustainable supply chain management across the UK private sector. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17(1):15-28. [https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541211212177]. [ Links ]

Walker, H., Di Sisto, L. & McBain, D. 2008. Drivers and barriers to environmental supply chain management practices: lessons from the public and private sectors. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 14(1):317-327. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2008.01.007]. [ Links ]

Wang, Z., Wang, Q., Zhang, S. & Zao, X. 2018. Effects of customer and cost drivers on green supply chain management practices and environmental performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 189:673-682. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.071]. [ Links ]

Wolf, C. & Seuring, S. 2010. Environmental impacts as buying criteria for third party logistical services. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 40(1/2):84-102. [https://doi.org/10.1108/09600031011020377]. [ Links ]

Wu, K.J., Tseng, M.L. & Vy, T. 2011. Evaluation the drivers of green supply chain management practices in uncertainty. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 25:384-397. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.02.049]. [ Links ]

Younis, H. & Sundarakani, B. 2019. The impact of firm size, firm age and environmental management certification on the relationship between green supply chain practices and corporate performance. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(1):319-346. [https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-11-2018-0363]. [ Links ]

Zhu, Q. 2013. Drivers and barriers of extended supply chain practices for energy saving and emission reduction among Chinese manufacturers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 40:6-12. [https://doi.org/ http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.09.017]. [ Links ]

Zhu, Q. & Sarkis, J. 2006. An inter-sectoral comparison of green supply chain management in China: drivers and practices. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(5):472-486. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.01.003]. [ Links ]

Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J. & Geng, Y. 2005. Green supply chain management in China: pressures, practices and performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 25(5):449-468. [https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570510593148]. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author

APPENDIX A

Main questions asked during the interview with participants

(Probing questions were used to delve deeper into participants' responses.)

Introductory questions

• Can you please briefly tell us what your position is in the firm and what it entails?

• How long have you been working in the firm?

• In which industry is the firm and what is your firm's main focus in the manufacturing industry?

• How many employees does this plant have?

• Does your firm belong to a Multinational Corporation (MNC) category?

Internal drivers and barriers

• Is your firm involved with green practices?

• Is management committed to implement green practices?

• What role does corporate image play in adopting/ not adopting green practices?

• Are there any internal pressures from employees to implement green initiatives?

• Are there any other internal factors that could drive or hinder the adoption of green practices?

External drivers and barriers

• Are there any external incentives or pressures to adopt GM from outside the firm?

• Are there a lot of environmental regulations in your industry?

• What role does the government/municipalities play in your firm adopting/not adopting GM practices?

• Do suppliers play a role in your firm adopting/ not adopting GM practices?

• Do competitors play a role in your firm adopting/not adopting GM practices?

• Do many of the firms in your industry adopt/consider the implementation of green practices?

• Do customers/consumers play a role in your firm adopting/not adopting GM practices?

• How do you communicate with the customers to identify their needs regarding green initiatives?

• What role do other shareholders play in your firm adopting/ not adopting GM practices?

• What role does the general public play in your firm implementing green practices?

• Does your firm implement any technology to deliver the product(s) more efficiently and environmentally friendly?

• Are there any other external factors that could drive or hinder the adoption of green practices?

Green inbound practices

• Does your firm purchase green 'materials'?

• How important is supplier sustainability and ISO certification as a selection criterion?

• Does your firm have a policy concerning the procurement of green materials from its suppliers?

• Does your firm provide design specifications to suppliers that include environmental requirements?

• Does your firm help its suppliers to become more environmentally friendly?

Green manufacturing practices

• Does your firm perform production planning to optimise workflows and reduce resources needed?

• Is your firm implementing actions to reduce energy usage, water consumption and any form of pollution?

• Has your firm designed its processes to use minimal resources and materials throughout the manufacturing process?

• Is your firm implementing re-usable or recyclable materials in its production processes?

• Are there any other factors driving or hindering green practices in your manufacturing processes?

Green outbound practices

• Is your firm involved in green outbound activities?

• Does your firm use green packaging?

• Is your firm involved with green distribution processes?

• Does your firm collect any used products or packaging from its customers?

• Does your firm recover its end-of-life products?

APPENDIX B