Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.19 no.1 Meyerton 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcm21028.137

ARTICLES

Modelling the effects of gross value added, foreign direct investment, labour productivity and producer price index on manufacturing employment

Thomas HabanabakizeI,; Precious MncayiII

IEconomics, North-West University, South Africa. Email: 26767007@nwu.ac.za; ORCID: 0000-0002-0909-7019

IIEconomics, North-West University, South Africa. Email: precious.mncayi@nwu.ac.za; ORCID: 0000-0001-5375-0911

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: The manufacturing sector plays a crucial role in various countries' economies, especially in developing countries. However, due technology growth and the emerging services sector, the possibilities and abilities of the manufacturing sector to influence economic and employment growth are becoming minimal. Therefore, job creation or destruction within this sector depends on both endogenous and exogenous factors. This study aims to investigate the effect of gross value added, foreign direct investment, labour productivity and producer price index on manufacturing employment.

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: To achieve the main objective of the study, authors applied the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL), ECM and Toda-Yamamoto causality approaches to quantitative quarterly data from 1995 to 2020.

FINDINGS: The study's findings suggest that both gross value added and producer price index stimulate job growth, while growth in labour productivity and foreign direct investment impede job growth in the manufacturing sector

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: Based on these findings, the study recommends that policymakers and economic stakeholders should implement strategies such as trade openness, as well as currency stabilisation and reduction in corporate taxes to enhance both investment and production. Additionally, government should impose limitations on the FDI level and encourage domestic investment and producer price index to stimulate employment in the manufacturing sector.

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The implications from this research study indicate that, during this era of the fourth industrial revolution and technology at work, high productivity and foreign direct investment may reduce labour demand rather than create job opportunities within the manufacturing sector

JEL CLASSIFICATION: D24, E24, L60, R15

Keywords: Employment; Manufacturing; Producer price index; Productivity; South Africa

1. INTRODUCTION

The declining share of manufacturing employment as a proportion of aggregate employment has been regarded as a cause for concern for policymakers and economists in emerging market economies and developing countries; South Africa is not excluded (Lawrence, 2018; International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2021; KPMG International (2020). These concerns arise from many long-held beliefs about the sector's importance in an economy. Firstly, according to Herman (2016), the manufacturing sector is one of the sectors contributing to a country's growth. Secondly, the sector assumes an essential part in evolving and developing economies into modern ones through the various spill-over effects, and forward and backward linkages with other economic sectors (Ciarli & Di Maio, 2013; Aldaba, 2014). As posited by Tregenna (2008), in most instances, the manufacturing sector is more likely to demand more goods and services produced by other sectors, than other sectors (e.g. services) demanding more of what is produced by the manufacturing sector itself. Thirdly, economic theory recognises this role and regards the sector's labour-intensive nature as contributory to sustainable economic growth through the generation of productive employment (Loto, 2012; Behun et al., 2018). This point is supported by Anyanwu (2017), who argues that the export-driven nature of the sector progressively increases the value of commodities before they are sold, boosting revenues and increasing input average revenues. These unique contributions by the sector therefore regard manufacturing as a catalyst to economic growth and development (Jeon, 2008).

Despite the importance of the sector, almost everywhere in the world, the manufacturing sector has been displaced by the services sector, whose contribution to growth and employment has increased substantially in the last decade (IMF, 2018). This has been fuelled by the sector's sensitivity to internal and external factors, which have resulted in massive cyclical fluctuations (Behun et al., 2018). As seen during the Covid-19 pandemic, most manufacturers became significantly affected by forced shutdowns, which not only reduced production, but also employment levels (Deloitte, 2021). In South Africa, manufacturing sector output and employment have been on a continual decline and even though the sector has shown to be on a rebound, there is evidentiary support that the sector is not creating employment, even though job losses have been slowing down (Stoddard, 2021). Therefore, Pachura (2017) strongly believes that cyclical sectors need to be constantly observed since any undesirable deviations in these sectors will naturally worsen economic recessions, which may be impeding economic progress.

The focus on manufacturing in this article is defended by the key role that is seen by policymakers in South Africa for the manufacturing sector in achieving a more dynamic economy, and the need to accomplish more rapid economic growth to deal with the country's challenge of unemployment and poverty (Edwards & Jenkins, 2015). This article shows how South Africa's manufacturing sector can be improved and ultimately result in positive employment levels. This is very important, especially since South Africa suffers from chronic unemployment levels for which there is a belief that an improved and growing manufacturing sector will create employment in other sectors through its backward and forward linkages. The rest of the paper is categorised as follows: the next section will provide a brief overview of the manufacturing sector in South Africa. This is followed by a look at the theoretical perspective of the manufacturing sector's employment in the economy, including empirical findings on the topic. Section 3 will highlight the methodological processes followed in the study. The results and findings are discussed in section 4. The conclusion and recommendations are discussed in section 5.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Overview of South Africa's economy and its manufacturing sector

Since the beginning of democracy in 1994, South Africa has not been able to make substantial gains from the economic transition that came about. The country has been in a vicious cycle of subdued growth, which has resulted in significantly small changes in poverty levels with worsening income inequality and unemployment. In addition, the ongoing skills gap has only meant that the majority of unskilled labour is trapped in the informal sector or completely without employment. According to Asmal et al., (2020), the South African economy has been portrayed by a dissolving primary sector and a stale manufacturing sector, a pattern that has been worrying, while the services sector has made substantial contributions in terms of gross domestic product and employment, highlighting the sector's long undermined importance. Manufacturing is being replaced by services, particularly financial and business services, in both value and employment shares (Robbins & Velia, 2016).

Be that as it may, the critical contribution of manufacturing cannot be overlooked as the sector has helped in spurring the growth in other sectors such as the transport and services sectors (Mkhize, 2019). The manufacturing sector is regarded as a very pivotal industry, particularly in the growth and development of a country. With South Africa being plagued by the triple challenges of unemployment (by any measure), inequality and poverty, the manufacturing industry is often regarded as one of the strongest drivers of sustainable growth and development (Bhorat & Rooney, 2017). The sector has the potential to transform productivity and induce rapid economic growth (Cilliers, 2018). However, the sector's contribution to the economy with regard to GDP growth and employment has been on a continual decline for decades now, indicative of the sector becoming progressively less competitive (Williams et alv 2014). The sector has decreased by more than 10 percent to 13 percent in 2020 from 26 percent in 1994 (Parker, 2020). The fall in the demand for steel, locally and globally, escalating costs of energy and the sector's unpredictable supply patterns affected by power outages (load shedding), increasing transportation costs, constant labour strikes, a weak rand, which raises imports of finished goods, have been regarded as some of the reasons for the sector's declining performance (Liedtke, 2021; Stats SA, 2021). Figure 1 reveals that between 2014 and the first quarter of 2020, the sector's contribution to GDP was less than 1 percent.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the sector recovered between the second and third quarters of 2020, recording a 10.8 percent and 16.2 percent contribution, respectively. Aspects such as the easing of lockdown restrictions, improved production in food, beverages and motor vehicles supported this increased contribution (Stats SA, 2020; Liedtke, 2021). Be that as it may, there are still concerns about the sector's level of activity, which remains well below that of recent years. For instance, at the end of the fourth quarter of 2020, annual manufacturing production had declined by approximately 11 percent, which is attributed to the declining demand for steel as well as Covid-19-linked production halts (Stats SA, 2021). Likewise, the sector's post-apartheid contribution to employment has worsened. Non-agricultural employment registered decreasing rates, which have been linked to many factors, including the country's inevitable move to capital intensive methods of production (Mkhize, 2019). Bhorat and Rooney (2017) attribute the negative performance to the country's growing skills shortage and the increased competition from south-east Asian manufacturers. Nordas (1995) and Parker (2020) point out that significant input costs and poor infrastructure have been viewed as the biggest obstacle to the sector's growth in South Africa. At the same time, the ongoing shortage of electricity, including reduced demand for steel, has resulted in the sector's output shrinkages and a lack of competitiveness (Stats SA, 2021), which becomes a drain on resources (Nordas, 1995). The subsequent section elucidates on the theoretical aspects and empirical findings relating to manufacturing employment.

2.2 Theoretical literature on manufacturing employment

As seen in previous sections, the demand for labour in the manufacturing sectors of both advanced and developing economies has declined substantially (Malik, 2019). Over and above cyclical factors, the prospects of employment creation in the manufacturing sector are limited by numerous distinctive factors, one being the phenomenon of growing import competition from Asia in many countries since the early 2000s (Charles et al., 2018; Levinson, 2019). If one considers South Africa, for instance, the reintroduction of the country to global trade following the end of the apartheid regime resulted in many changes in terms of sectoral composition of GDP (Mkhize, 2019). Even though some may argue that market liberalisation brought about the much needed growth in the country, in the same vein, they also exposed the domestic markets to increased foreign competition. In the United States, Autor et al. (2013) found a significant increase in Chinese imports to the U.S. relative to import quantities from other trading partners; this increase was observed in terms of levels and growth rates. This shows that even though globalisation has brought about many benefits, including product diversification to the domestic consumer, it has likewise brought about negative economic repercussions that will prove to be difficult to reverse, especially as the world prepares for the fourth industrial revolution.

What further fuels this difficulty is the acknowledgement by economic theory of the importance of technological accumulation within the manufacturing sector as an important driver of economic growth (Mellet, 2012). Many firms have as a result adopted production techniques that use less labour in favour of technology and other inputs. According to Charles et al. (2018), this is one of the potential explanations for manufacturing's deteriorating labour demand, which has, in turn, resulted in reduced manufacturing employment. Malik (2019) argues that foreign firms tend to use relatively advanced technologies, requiring skilled workers or fewer workers to produce in host countries, which may bring about a reduction in demand for labour in these countries. This may be especially true in developing countries where a large share of the labour force is unskilled, which is the case in South Africa. Unlike the neoclassical theory, the modern school of thought that relates to the new growth theory contends that despite the fact that technological development raises productivity, standards of living are most likely to linger behind if there are no inducements set up to advance inventiveness, innovation and the accumulation of knowledge, which are linked to human capital (Romer, 1989).

Be that as it may, investment spending still plays a critical role towards employment creation and economic growth (Mohr & Associates, 2015). Investments by foreign firms specifically could have implications for the host country. According to Girma (2005), an imperative purpose, among other things, for drawing in foreign direct investments (FDI) is the deduction that foreign multinationals create employment, either straightforwardly through their own employment growth plans or through spill-over effects, which are most likely to result in positive growth prospects in other economic sectors through greater benefits such as technological transfer. Furthermore, given that a growing share of workers in non-industrial countries are profoundly focused on farming and informal sectors, it is believed that employment generated through FDI could transfer workers from the primary and informal sector to more modern sectors such as manufacturing and services (Lipsey et al., 2010). The increased employment could, according to Wong and Tang (2010) and Jenkins (2006), manifest only if FDI inflows complement domestic investment and are more focused in labour-intensive sectors. In addition to the abovementioned factors, declining manufacturing value-added has been pointed out as one of the factors that has an impact on employment in the manufacturing sector. It can therefore be reasoned that increasing value-added production would bring about improvements in the industrial sector through increased output (United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), 2015). According to Jamaliah (2016), value-added production could significantly influence employment, because the value-added production is able to cause increased demand for the goods and services sector, thereby pushing the amount of labour absorbed. Conversely, the OECD (2010) adds that high value-added manufacturing investment does not directly result in massive creation of employment, predominantly because a steel plant may employ a few workers instead of more due to enormous advantages in technology. If the manufacturing value-added per capita is strongly employment driven, then the demand for labour will rise. The United Nations (2020) reports that between 2000 and 2018, less-developed countries experienced an increased share of manufacturing in employment from 3.3 to 9.1 percent, which was brought about by increased valued-added manufacturing that was employment focused. Consequently, value-added manufacturing that is attained through capital intensive methods of production is detrimental to the employment creation of labour.

Another factor that affects the creation of manufacturing employment is price instability, which is one of the factors that could result in substantial macroeconomic effects (Szymanska, 2011; Lado, 2015). In particular, rising input costs may directly impact the rate of manufacturing employment creation. When producers experience rises in input prices, as seen by the rising producer price index (PPI), they are likely to lower their demand for labour, which, if increased, could add to the already rising producer costs (Khan et al., 2018).

Turning to labour productivity, from a wide point of view, increasing productivity could be a major source of economic growth, leading to increased demand for labour (Mahmood, 2006). The impact of productivity growth is in-between, either positive or negative, at the micro-level. In general, higher productivity, which implies higher efficiency levels, infers that the same level of output can be produced with less labour, thereby diminishing the demand for labour (Fourie & Burger, 2011). On the one hand, higher productivity leads to price reductions, which raise the demand for the product, increasing the demand for labour (Mahmood, 2006). Gall (1999) argues that even though high productivity growth within the short run may reduce employment, in the long run it will have a positive impact on the demand for labour.

2.3 Empirical literature on the performance of manufacturing employment

This section highlights findings of studies conducted on the performance of employment in the manufacturing sector. A study that investigated the impact of the manufacturing industry on the economic cycle of European Union countries found that changes in a country's development status have an impact on the employment, compensation of workers and the number of hours worked in the manufacturing sector (Behun et al., 2018). Based on the analysis, employment in the manufacturing sector, wages and salaries as well as the number of hours worked were reported to be strongly linked to the cyclical development of the economy; that is, they increased during upswings and declined during downswings.

Williams et al. (2014) reported a strong and positive correlation between technological advancement and direct employment creation in the manufacturing sector, although there seems to be a slightly negative correlation between process innovation and direct jobs. In addition, they found that the proportion of indirect jobs to direct manufacturing jobs increases dramatically as manufacturing becomes more high-tech and advanced due to forward and backward (extensive supply chains) linkages and a sophisticated manufacturing service sector.

Mkhize (2019), who analysed the sectoral employment intensity of growth in South Africa using cointegration estimation techniques, found a long-run relationship between employment and growth in the manufacturing sector. What these findings imply is that the observed growth performance in the sector has been driven by increased labour productivity and not increased employment, which confirms the presence of a growing use of capital-intensive methods of production. The study concluded that sectoral growth alone cannot ensure considerable employment growth within the sector, but synchronous initiatives that are labour market driven may be necessary to promote employment growth.

Levinson (2019) reported that a strong growth in manufacturing is likely to have a modest impact on overall employment creation, particularly for workers with lower levels of education. In a study that analysed manufacturing employment in the US, Pierce and Schott (2016) found a sharp decline in employment within the US manufacturing sub-sectors, which was linked to the increased import penetration by Chinese firms. They also observed that increased entry by US importers and foreign-owned Chinese exporters results in more capital-intensive production at the cost of labour.

In terms of FDIs, Feenstra and Hanson (1995) found that FDI inflows increased the relative demand for skilled labour in Mexican manufacturing. In 2019, it was found that FDI inflows in the US aided in reinforcing the domestic manufacturing sector, increasing employment and the economic improvements that go with it (International Trade Administration, 2019). In a study that investigated FDI and employment in Singapore's manufacturing and services sector through the use of cointegration methods of analysis, Wong and Tang (2010) found strong indications of short-run causation that runs from FDI inflows to manufacturing employment and, in turn, employment linkages that run from manufacturing to services, which supports the view that the manufacturing sector through forward and backward linkages has positive spillovers on other sectors.

There was also a unidirectional causation that runs from employment in manufacturing and services to FDI inflows in the long run, implying over and above other factors, an expansion of the skilled workforce in these sectors is instrumental in drawing FDI inflows into the country, thereby opening up a channel for imperative sources of innovation and better international business networks. Different from the US and Singapore, FDI was found not to have any significant impact on domestic demand for labour in Indian manufacturing industries (Malik, 2019).

In a study that looked at the impact of Chinese import dispersion in the South African manufacturing sector, Edwards and Jenkins (2015) found that increased imports from China caused South African manufacturing output to be 5 percent lower in 2010 than it otherwise would have been. The projected decline in aggregate employment in manufacturing as a result of trade with China is larger - at an estimated 8 per cent since the deteriorations in output were focused on labour-intensive sub-sectors and also because the intensification in imports raised up labour productivity within those sub-sectors.

Through the use of path analysis, production added value was found to have a positive significant effect on employment absorption in the West Kalimantan province, Indonesia (Jamaliah, 2016). Dew-Becker and Gordon (2012) reported a strong and negative association between the growth of labour productivity and employment per capita across the EU-15. In other words, increased productivity resulted in reduced demand for labour. Similar findings are also observed by Junankar (2013). Mahmood (2006) could not establish any correlation between labour productivity growth and employment among Australian manufacturing small and medium and micro-enterprises. The following section discusses the methodological processes that were followed in the study.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1 Sample and data description

The empirical analysis of this study was based on time series data of 100 quarterly observations from the first quarter of 1995 to the second quarter of 2020. This sample period corresponds to the introduction of economic structural changes following the country's (South Africa) democratisation in 1994. The variables included in the study are employment, labour productivity, foreign direct investment (FDI), producer price index (PPI) and manufacturing output or gross value added (GVA). All these variables were sourced from the South African Reserve Bank (SARB, 2020). The measurement and abbreviations are summarised in Table 1.

3.2 Model specification

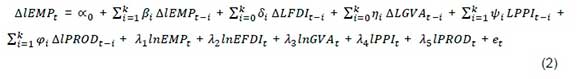

The autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model was selected to assess both the long-run and short-run effects of foreign direct investment, manufacturing gross value added, producer price index and labour productivity on employment levels in the South African manufacturing sector. Following the variables recorded in Table 1, the subsequent function was formulated:

Where EMP is employment, FDI is foreign direct investment, GVA is gross value added, PPI is a producer price index and PROD is labour productivity. To achieve the primary objective of the study, which is to determine the effect of foreign direct investment, gross value added, producer price index and labour productivity on employment in the manufacturing sector, the authors applied the ARDL model proposed by Pesaran and Shin (1998) and revised by Pesaran et al. (2001). This model was selected based on three of its main advantages. Firstly, this model can be applied to variables that are integrated of I(0), or a combination of the two [I(0) and Secondly, it produces accurate results even when applied to a small sample of data (Pesaran et al., 2001). Lastly, it gives unbiased t-values and long-run results irrespective of the presence of indigenous regressors in the model (Harris & Sollis, 2003). To test the effects of independent variables on dependent variables, building Equation 1, the following model was estimated:

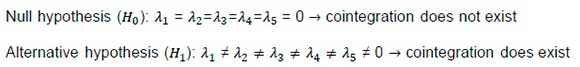

Where LEMP is the log of employment, LFDI is the log of foreign direct investment, LGVA is the log of gross value added, LPPI is the log of the producer price index and LPROD is the log of labour productivity. βi, δi, ni, Ψi and φtare the short-run coefficients to be estimated, while λ1 to λ5are long-run coefficients to be estimated and t denotes a specific period. Additionally, oc0and etrefer to the intercept and error term correspondingly. Following the model established in Equation 2, cointegration among variables was tested based on the subsequent hypothesis.

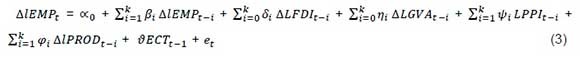

Through Wald's F-statistics, the ARDL bound test was performed. This test aimed to compare the value of the computed F-statistics to the critical bond values from the Pesaran et al. (2001) tables. The outcome from the bound test has three possible outcomes. The first is that if the computed F-statistics are greater than the upper bound critical value, then cointegration exists between variables. The second possibility is to find the computed F-statistics below the lower bound critical values, meaning the absence of cointegration. The last possible possibility is that the computed F-statistics are greater than the lower bound critical value, yet smaller than the upper bound critical value. In this case, unless further information is provided, the results are inconclusive. If the first scenario prevails, where the null hypothesis suggesting the absence of cointegration is rejected, the estimation of the error correction model (ECM) is required. Since this study's Wald test results indicated a cointegration between foreign direct investments, gross value added, producer price index, labour productivity and employment in the manufacturing sector, the ECM was derived from Equation 2 and formulated as follows:

Where ECTt-1is the error correction with its coefficient # that assists in measuring the speed of adjustment towards long-run equilibrium.

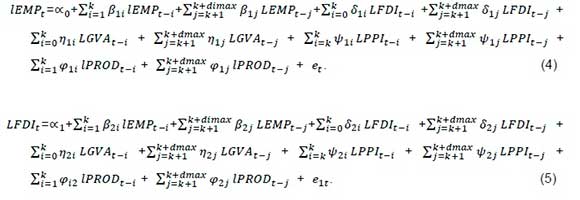

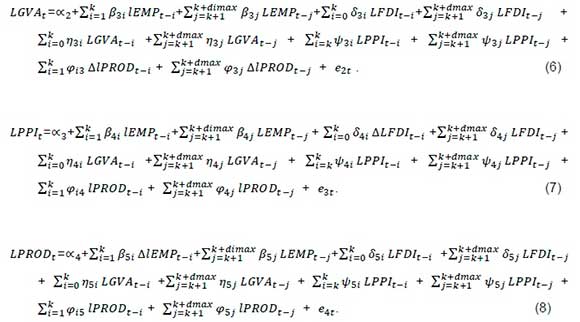

Since the literature (Bhattacharya et al., 2011) argues that a causation relationship exists between labour productivity and employment in the manufacturing sector, the causality analysis appeared important to the current study. Additionally, if two or more variables are cointegrated, there should be a causal relationship between them. Therefore, in case the ARDL model has established the presence of long-run relationships among variables, the causality analysis is then crucial. The application of the traditional Granger causality suggested by Granger (1969) undertakes variables that are integrated of the same order. In case this approach is applied to variables of a different order of integration, the invalid result is more likely to be produced (Toda & Yamamoto, 1995). To overcome that issue of obtaining spurious regression, Toda and Yamamoto (1995) suggested another Granger causality approach applicable to variables with different orders of integration. With this approach (ARDL), the probability and risks of obtaining inappropriate results, owing to sample size and order of integration, are minimised (Mavrotas & Kelly, 2001). The estimated Toda-Yamamoto (T-Y) equations for this study are the following:

Where dmax represents the maximum order of integration for the underpinned variable. In this T-Y approach, the modified Wald (MWALD) test was applied to the unrestricted regression to test both the null hypothesis and its alternative. The test is intended to assess the null hypothesis, suggesting that coefficients of the lagged values of each explanatory variable (within each of equations 4 to 8) are equal to zero. The rejection of the null hypothesis indicates the presence of causal relationships among variables and a failure to reject the null hypothesis indicates the absence of Granger causality. To ensure that findings from ARDL and T-Y models meet the basic econometric assumptions, the diagnostic tests for autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity, and normality and parameter stability are performed before the results' discussion.

4. REGRESSION ANALYSIS, RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Unit root and stationarity tests results

The unit root is one of the critical steps of econometric analyses. To ensure that the selected model is appropriate to the study's underlined variables, this process was performed through the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin test statistic (KPSS) tests. The ADF test examines the null hypothesis suggesting that a variable has unit root against the alternative hypothesis, stipulating that the variable has no unit root or rather is stationary. Contrary to ADF, the KPSS test is used to examine the null hypothesis suggesting that a variable is stationary against the alternative hypothesis, suggesting that the variable is not stationary. Table 2 exhibits the results from both ADF and KPSS tests.

The results from the ADF and KPSS tests are conflicting. While the ADF results suggest that all variables, except for LFDI, become stationary at first difference, the KPSS results suggest that three variables (LEMP, LFDI, LPPI) are stationary at levels and the remaining two variables (LGVA, LPROD) become stationary at first differences. The common ground of these two tests is that the underlying variables for the study are a mixture of I(0) and I(2). Since there is no variable that is integrated of second order [I(2)], the ARDL model is the appropriate model to analyse the relationship among variables. Given that the order of integration of the study variables and appropriate model is known, the next step is the assessment of long-run relationships through the bound test for cointegration.

4.2 Cointegration and long-run analysis

The existence of long-run relationships was analysed using the bound test for cointegration. Using the Akaike information criterion, the ARDL (1, 0, 1, 3, 2) was selected as the best model for analysis. This model was estimated with intercept without trends. The results from the bound test for cointegration are represented in Table 3. As shown in the table, the value of computed F-statistics is greater than the upper bound critical value at the 0.01 level of significance. This result suggests the rejection of the null hypothesis of no cointegration. In other words, a long-run relationship exists between foreign direct investment, gross value added, producer price index, labour productivity and employment in the South African manufacturing sector.

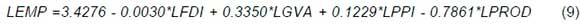

The presence of cointegration between the dependent and independent variables suggests the analysis of the long-run coefficients. Equation 9 displays the coefficient and the long-run coefficients.

The long-run coefficients displayed in Equation 9 indicate that out of four explanatory variables, two (foreign direct investment and labour productivity) have a negative effect on manufacturing employment, while the remaining two (gross value added or output and producer price index) have a positive impact on employment within the South African manufacturing sector. In the long run, a one percent increase in foreign direct investment causes employment to decrease by 0.0030 percent, while a one percent increase in labour productivity causes the manufacturing employment to decline by 0.7861. Contrary to the aforementioned explanatory variables (foreign direct investment and labour productivity), the results in Equation 9 indicated that when the manufacturing output increases by one per cent, the labour demand or employment increases by 0.3350 percent. Additionally, a one percent increase in producer price index leads to an increase of 0.1229 in employment level. Regarding the effect of explanatory variables on manufacturing employment, the gross value added has the highest positive impact on manufacturing employment, while the foreign direct investment has the smallest negative impact on employment levels. These findings support other studies' findings (Cantore et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2017; Ziva, 2017; Woltjer et al., 2021), whose results revealed a significant long-run impact of foreign direct investment, gross value added or output, producer price index and labour productivity on manufacturing employment.

4.3 Brief discussion of long-run results

The negative relationship between foreign direct investment and employment in the manufacturing sector implies that foreign investors, with the aim of improving production and sales, employ more capital and technology. This causes a reduction in labour demand and, consequently, contributes to higher rates of unemployment in South Africa. Some other studies, such as Umit and Alkan (2016), and Pierce and Schott (2016) found similar results, suggesting an inverse relationship between foreign direct investment and employment levels. In other words, high FDI inflows are associated with capital intensive production at the expense of labour demand. In line with FDI, this study found that an increase in labour productivity causes a decline in employment levels. This is because, in this era of improved technology, one worker is able to produce what should be produced by two or more workers. As workers are familiarised with technology, the productivity increases and consequently labour demand decreases. This adverse relationship between employment and labour productivity was also highlighted in the study of Junankar (2013). Contrary to the negative impact of labour productivity and FDI, gross value added and producer price index positively influence employment in manufacturing sector. Value-added production influences employment because the value added is considered as a share of economic growth. Increasing value added leads to economic improvement and the latter is known to be one of key factors that stimulates and generates employment. A strong economy is associated with improved demand for goods and services in the manufacturing sector, thereby pushing the amount of labour demanded. A positive association between the manufacturing value added and employment was also reported by Jamaliah (2016) and the United Nations (2020).

4.4 ECM and short-run relationships

Once the long-run relationship is established, it is important to estimate the error correction model (ECM) in order to determine the short-run dynamics. The results displayed in Table 4 indicate that the value of the error correction term (ECT) is negative and significant at the 0.01 significance level. The ECT coefficient is 0.149244, suggesting that almost 15 percent of shocks are eliminated each quarter. It will, therefore, take approximately 6.7 (1/0.149244) quarters (about a year and a half) to restore the long-run equilibrium in manufacturing employment. The short-run results in Table 4 indicate that all independent variables, except foreign direct investment, possess a short-term impact on manufacturing employment. In other words, gross value added or output, producer price index and labour productivity are statistically significant to influence the short-run dynamism of employment in the manufacturing sector. However, while both gross value added and labour productivity lead to a positive change in employment levels, the latter is negatively influenced by the short-term increase in producer price index.

4.5 Causality between foreign direct investment, gross value added, producer price index, labour productivity and manufacturing employment

The presence of long-run relationships among the underlined variables suggests the likelihood of a causal relationship between foreign direct investment, gross value added, producer price index, labour productivity and employment in the South African manufacturing sector. As highlighted in the methodology section, when analysing the causal relationship of a mixture of variables and I(2)], the Toda-Yamamoto Granger causality is the appropriate approach to use. Using information criteria for lag selection, two lags were selected for the T-Y model as expressed in Equations 4 to 8. Granger causality test results are exhibited in Table 5. Based on the results in Table 5 below, none of the independent variables are predictors or can cause the short-term changes in employment in the manufacturing sector. However, all the underlined variables have the power to cause changes in the output levels, as they are all statistically significant at the 0.01 percent level. Additionally, there exists a unidirectional causal relationship between employment, producer price index and labour productivity. These T-Y results suggest that employment in the manufacturing sector is not more sensitive towards short-run changes in foreign direct investment, gross value added, producer price index and labour productivity.

4.6 Diagnostic tests

The robustness of the study findings from both ARDL and T-Y models was assessed through different diagnostic and stability tests. Among others, the study performed heteroscedasticity, normality, serial correlation and stability tests. The null hypothesises suggest that residuals are normally distributed, are not serially correlated, are not heteroscedastic and the used models are stable. The summary of the performed tests and their results and conclusions are portrayed in Table 6. Both ARDL and T-Y models have passed the diagnostic and stability tests,

5. CONCLUSION

Employment growth remains an important economic indicator as it is one of the major sources of income for households (in terms of salaries and wages) and national income (in terms of tax). This elucidates how all economic stakeholders should work together regarding employment in job creation. However, despite its role in the country's economic growth, the South African manufacturing sector is experiencing a serious challenge in terms of job growth. As job growth within the manufacturing sector depends on other micro- and macroeconomic variables, this study used the ARDL and Toda-Yamamoto Granger causality models to determine the effect of foreign direct investment, manufacturing output, producer price index and labour productivity on employment growth in the South African manufacturing sector. It is imperative for the country to embrace and adopt advanced manufacturing approaches alongside conventional manufacturing methods for economic growth, employment and international competitiveness (Williams et al., 2014).

The study's findings established a long-run relationship between the aforementioned economic variables. It was found that, in the long run, the increment of both foreign direct investment and labour productivity leads to job losses in the manufacturing sector, while growth in both gross value-added or output and producer price index enhances job creation or employment growth within the South African manufacturing sector.

The short-run findings indicated that manufacturing employment is mainly affected by positive growth in output. The rest of the variables negatively impact on manufacturing employment. The Granger causality result revealed that although employment from the manufacturing sector can cause both labour productivity and the output growth, none of the independent variables Granger cause employment. Based on these findings, it important to recommend that policymakers should strive to create a favourable environment that enhances manufacturing output and producer price index as they positively impact on employment growth in both the long- and short run. Further studies could analyse what causes the foreign direct investment to have a negative impact on South African manufacturing employment.

6. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATION AND STUDY CONTRIBUTION

This study's findings contribute to both theoretical and empirical literature, as well as policy implications. In terms of theoretical literature, the study contributes to the discussion on manufacturing employment and its responsiveness to some macroeconomic variables such as labour productivity, foreign direct investment and the gross value added (output). The study highlighted the importance of the manufacturing sector for the South African economy, especially in terms of job creation. The study also discussed issues that are faced with the aforementioned sector.

From an empirical point of view, the study provided the effect of gross value added, foreign direct investment, labour productivity and producer price index on manufacturing employment and how the latter responds to changes in the explanatory variables. Although foreign direct investment is generally considered as one of factors that may improve the manufacturing sector and thereby create more jobs, the study's findings indicated that it is not the case in the South African manufacturing sector. Therefore, with the intention of creating more and sustainable jobs in the South African manufacturing sector, policymakers and economic authorities should limit the level of the FDI and encourage domestic investment and producer price index. Additionally, they should implement strategies such as trade openness, currency stabilisation and reduction in corporate taxes.

Irrespective of sound findings, the core limitation of this study was the use of a low number of independent variables, while manufacturing employment can be influenced by various factors, which include technology, openness and demand pattern fluctuations. Further studies should consider the effect of some other factors such as technology growth, exchange rate volatility and country openness.

REFERENCES

Aldaba, R.M. 2014. The Philippine manufacturing industry roadmap: agenda for new industrial policy, high productivity jobs, and inclusive growth. Philippine Institute for Development Studies, 32(14):1-80. [ Links ]

Anyanwu, J.C. 2017. Manufacturing value added development in North-Africa: analysis of key driver. Asian Development Policy Review, 5(4):281-298. [https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.107.2017.54.281.298]. [ Links ]

Asmal, Z., Bhorat, H. & Page, J. 2020. Exploring new sources of large-scale job creation: the potential role of Industries Without Smokestacks. [Internet: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ForesightAfrica2020_Chapter3_20200110.pdf; downloaded on 24 February 2021]. [ Links ]

Autor, D.H., David D. & Gordon, H.H. 2013. The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States. American Economic Review, 103(6):2121-68. [ Links ]

Behun, M., Gavurova, B., Tkacova, A. & Kotaskova, A. 2018. The impact of the manufacturing industry on the economic cycle of European Union countries. Journal of Competitiveness, 10(1):23-39. [https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2018.01.02]. [ Links ]

Bhattacharya, M., Narayan, P.K., Popp, S. & Rath, B.N. 2011. The productivity-wage and productivity-employment nexus: a panel data analysis of Indian manufacturing. Empirical Economics, 40(2):285-303. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-010-0362-y]. [ Links ]

Bhorat, H. & Rooney, C. 2017. State of manufacturing in South Africa. Development Policy Research Unit Working Paper 201702. DPRU, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Cantore, N., Clara, M., Lavopa, A., & Soare, C. 2017. Manufacturing as an engine of growth: which is the best fuel? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 42(1):56-66. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2017.04.004]. [ Links ]

Charles, K.K., Hurst, E., & Schwartz, M. 2019. The transformation of manufacturing and the decline in US employment. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 33(1):307-372. [ Links ]

Ciarli, T. & Di Maio, M. 2013. Theoretical arguments for industrialisation driven growth and economic development. University of Sussex, Science and technology policy research: Working paper series SWPS 20134/06. [https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2736806]. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J. 2018. Made in Africa: manufacturing and the fourth industrial revolution. Africa in the World Report 8. Institute for Security Studies: Pretoria. [ Links ]

Deloitte. 2021. 2021 Manufacturing industry outlook. [Internet: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/energy-and-resources/articles/manufacturing-industry-outlook.html; downloaded on 10 July 2021]. [ Links ]

Dew-Becker, I.L. & Gordon, R.J. 2012. The role of labor-market changes in the slowdown of European productivity growth. Review of Economics and Institutions, 3(2): 1-45. [ Links ]

Edwards, L. & Jenkins, R. 2015. The impact of Chinese import penetration on the South African manufacturing sector. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(4):447- 463. [https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.983912] [ Links ]

Feenstra, R.C. & Hanson, G.H. 1995. Foreign investment, outsourcing and relative wages. NBER working paper no. 5121, NBER, Cambridge, MA. [https://doi.org/10.3386/w5121]. [ Links ]

Fourie, F. CvN. & Burger, P. 2011. How to think and reason in macroeconomics. Pretoria: Juta. [ Links ]

Gall, J. 1999. Technology, employment, and the business cycle: do technology shocks explain aggregate fluctuations? American Economic Review, 89(1):249-271. [ Links ]

GIRMA, S. 2005. Safeguarding jobs? Acquisition FDI and employment dynamics in U.K. manufacturing. Review of World Economics, 141(1):165-178. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-005-0020-1]. [ Links ]

GRANGER, C.W. 1969. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 37(3):424-438. [https://doi.org/10.2307/1912791]. [ Links ]

Harris, R. & Sollis, R. 2003. Applied Time Series modelling and forecasting. Chichester: Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

Herman, E. 2016. The Importance of the Manufacturing Sector in the Romanian Economy. Procedia Technology, 22 (1):976-983. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2016.01.121]. [ Links ]

IMF. 2021. World economic outlook: managing divergent recovering. IMF, Washington DC. [ Links ]

International Trade Administration. 2019. The Intersection of Manufacturing & FDI: Job Creation. [Internet: https://blog.trade.gov/2019/10/04/the-intersection-of-manufacturing-fdi-job-creation/; downloaded on 30 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Jamaliah 2016. The effects of investment to value added production, employment absorption, productivity and employees' economic welfare in manufacturing industry sector in West Kalimantan province. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 219 (31):387-393. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.060]. [ Links ]

Jenkins, R. 2006. Globalization, FDI and employment in Viet Nam. Transnational Corporations, 15(1):115-42. [ Links ]

Jeon, Y. 2008. Manufacturing, Increasing returns and economic development in China, 1979- 2004: A Kaldorian Approach. Working paper No. 2006-08. [Internet: www.econ.utah.edu/activities/papers/2006-08.pdf; downloaded on 24 February 2021]. [ Links ]

Junankar, P.N. 2013. Is there a trade-off between employment and productivity? Discussion Paper No 7717. IZA, Bonn. [ Links ]

Khan, K., Su, C., Tao, R. & Chu, C. 2018. Is there any relationship between producer price index and consumer price index in the Czech Republic? Economic Research, 31(1):1788-18. [https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2018.14980071 [ Links ]

KPMG International. 2021. Global manufacturing outlook 2020 - covid19 special edition. [Internet: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2020/11/global-manufacturing-outlook-2020-covid-19-pecial-edition.pdfDownloaded on 10 July 2021]. [ Links ]

Lado, E.P.Z. 2015. Test of the relationship between exchange rate and inflation in South Sudan: Granger-causality approach. Economics,4(2):34-W. [https://doi.org/10.11648/j.eco.20150402.13]. [ Links ]

Lawrence, R. 2021. The future of manufacturing employment. Centre for Development Insight, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Liedtke, S. 2021. Decreased manufacturing output shows South Africa is lagging behind in its industrialization efforts. Engineering News, 9 Dec. [Internet: https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/decreased-manufacturing-output-shows-south-africa-is-lagging-behind-in-its-industrialization-efforts-2021-12-09/rep id:4136; downloaded on 14 January 2021]. [ Links ]

Lipsey, R. E., Sjoholm, F & Sun, J. 2010. Foreign ownership and employment growth in Indonesian manufacturing, working paper (No. w15936), National Bureau of Economic Research. [https://doi.org/10.3386/w15936]. [ Links ]

Loto, M. A. 2012. Global economic downturn and the manufacturing sector performance in the Nigerian economy (A Quarterly Empirical Analysis). Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences, 3 (1):38-45. [ Links ]

Mahmood, M. 2006. Labour productivity and employment in Australian manufacturing SMEs. International Entrepreneurship Management Journal, 24:51-62. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-006-0025-9]. [ Links ]

Malik, S.K. 2019. Foreign direct investment and employment in Indian manufacturing industries. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 62:621-637. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-019-00193-6]. [ Links ]

Mavrotas, G & Kelly, R. 2001. Old wine in new bottles: testing causality between savings and growth. The Manchester School, 69(s1):97-105. [https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9957.69.s1.6]. [ Links ]

Mkhize, N.I. 2019. The sectoral employment intensity of growth in South Africa. Southern African Business Review, 23:1-24. [https://doi.org/10.25159/1998-8125/4343]. [ Links ]

Mellet, A. 2012. A critical analysis of South African economic policy. PhD Thesis. Vanderbijlpark-NWU. [ Links ]

Mohr, P & Associates. 2015. Economics for South African Students. 5th ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Nordas, H.K. 1995. South African manufacturing industries - catching up or falling behind? Chr, Michelsen Institute Working Paper 2. CMI: Bergen, Norway. [ Links ]

OECD. 2010. How imports improve productivity and competitiveness. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. [Internet: http://www.oecd.org/trade/45293596.pdf ; downloaded on 31 January 2022]. [ Links ]

Pachura, A. 2017. Innovation and change in networked reality. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 15(2): 173- 182. [https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2017.15.2.16]. [ Links ]

Parker, D. 2020. Sector's GDP contribution not what it should be. Engineering News, 29 May. [Internet: https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/manufacturings-gdp-contribution-not-what-it-should-be-2020-05-29/repid:4136; downloaded on 02 February 2021]. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2017.07.016]. [ Links ]

Pesaran, M.H. & Shin, Y. 1998. An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. Econometric Society Monographs, 31:371-413. [https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL521633230.011]. [ Links ]

Pesaran, M.H., Shin, Y & Smith, R. 2001. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3): 289-326. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616]. [ Links ]

Pierce, J.R & Schott, P.K. 2016. The surprisingly swift decline of US manufacturing employment. American Economic Review, 106(7):1632-62. [https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20131578]. [ Links ]

Robbins, G., & Velia, M. 2016. Large & medium firms in eThekwini: constraints to growth and employment generation. Report prepared for the Programme to Support Pro-Poor Policy Development (PSPPDII), South Africa. [ Links ]

Romer, P. 1989. Capital accumulation in the theory of long-run growth. Modern Macroeconomics. R. Barro (ed.) Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

South African Reserve Bank (SARB). 2020. Historic macroeconomic information. [Internet: https://www.resbank.co.za/en/home/what-we-do/statistics/releases/online-statistical-query. downloaded on 31 January 2022]. [ Links ]

Stats Sa. 2020. Gross domestic product - third quarter. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Stats Sa. 2021. GDP: Quantifying SA's economic performance in 2020. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Stoddard, E. 2021. Absa PMI ticks up in January, but remains subdued. Business Maverick, 2 Feb. [ Links ]

Szymanska, A. 2011. Price stability and its realization; the case of the Czech Republic and Poland. AD ALTA. Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 1(2):105-109. [ Links ]

Toda, H.Y. & Yamamoto, T. 1995. Statistical inference in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated process. Journal of Econometrics, 66(1):225-250. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01616-8]. [ Links ]

Tregenna, F. 2008, The contributions of manufacturing and services to employment creation and growth in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 76(2):175-175. [https://doi.org/10.1111/U813-6982.2008.00187.x]. [ Links ]

Umit, A.O., & Alkan, H.I. 2016. The effects of foreign direct investments and economic growth on employment and female employment: a time series analysis with structural breaks for Turkey. International Journal of Business and Economic Sciences Applied Research, 9(3):43-49. [ Links ]

United Nations Industrial Development Organization. 2015. The role of technology innovation in inclusive and sustainable industrial development. Industrial Development Report. Vienna. [ Links ]

United Nations. 2020. SDG Pulse - UNCTAD takes the pulse of the SDGs. Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Williams, G., Cunningham, S. & De Beer, D. 2014. Advanced manufacturing and jobs in South Africa: an examination of perceptions and trends. Johannesburg. Paper presented at the International Conference on manufacturing-led growth for employment and equality. [ Links ]

Woltjer, G., Van Galen, M. & Logatcheva, K. 2021. Industrial Innovation, labour productivity, sales and employment. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 28(1):89-113. [https://doi.org/10.1080/13571516.2019.1695448]. [ Links ]

Wong, K.N & Tang, T.C. 2010. Foreign direct investment and employment in manufacturing and services sectors Fresh empirical evidence from Singapore. Journal of Economic Studies, 38(3):313-330. [https://doi.org/10.1108/01443581111152427]. [ Links ]

Yuan, F., Gao, J., Wang, L. & Cai, Y. 2017. Co-location of manufacturing and producer services in Nanjing, China. Cities, 63:81-91. [https://doi.org/10.1016/Lcities.2016.12.021]. [ Links ]

Ziva, R. 2017. Impact of inward and outward FDI on employment: the role of strategic asset-seeking FDI. Transnational Corporations Review, 9(1):1-15. [https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2017.1290919]. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author