Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Contemporary Management

On-line version ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.19 n.1 Meyerton 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcm20138.136

ARTICLES

Causes of the low penetration rate in the South African co-operative financial institution sector: A consumer perspective

Bouba IsmailaI, ; Vangeli GamedeII; Obianuju Okeke-uzodikeIII

ICollege of Law and Management Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Email: 217076451@stu.ukzn.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6753-5873

IICollege of Law and Management Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Email: gamede@ukzn.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1531-0725

IIIFaculty of Applied Management, Durban University of Technology, South Africa. Email: uju_ebele@yahoo.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9301-7172

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: This study sought to investigate the possible reasons for the low penetration rate within the South African Co-operative financial sector, focusing on consumer knowledge and their engagement with co operative financial institutions, as well as their awareness of the entrepreneurial and innovative activity of co operative financial institutions (CFIs). The study is significant because the co-operative financial institution sector in South Africa is very small compared to other African countries, with a penetration rate of just 0.1 percent despite the important role that financial co-operatives play in poverty reduction and financial inclusion, which is recognised by governments worldwide. Surprisingly, no study has been conducted in South Africa in an attempt to find the reason behind this sector's very low penetration rate

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: The study used a quantitative design; and a structured questionnaire was used to collect data from 303 participants around the City of Tshwane. The SPSS software package was used to analyse data. The tests included descriptive statistics, Chi-square goodness-of-fit-test, binomial test, one sample t-test, and factor analysis

FINDINGS: The study found that a significant majority of the respondents did not know about CFIs or the services they offer. This may explain the low penetration rate of the industry

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: The study serves as the basis for a wider study in other regions of the country, and even internationally. It is recommended that research across the country, with a representative sample, be considered in future studies in order to generalise the findings to the entire country

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The implication of this finding is that the sector's top management needs to adapt and implement a systematic programme to try and close that knowledge and awareness gap; thereby enabling them to reach a larger number of consumers. Other stakeholders, such as government and NGOs, should also review their approach to assisting co-operatives in order to be more effective

JEL CLASSIFICATION: G21

Keywords: Co-operatives; co-operative financial institutions; corporate social responsibility strategies; marketing strategies; offensive strategies; penetration rate.

1. INTRODUCTION

The two main concepts used in this study, namely co-operatives and co-operative financial institutions, need to be defined. The Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) (2017) defines a co-operative as a distinct type of company that provides services and/or products to its members; and profits or surpluses are shared among members in relation to the amount of business each of them did with the co-operative (2017). The objective is for the members to achieve individual and collective financial emancipation. Types of co-operatives include agricultural; marketing; housing; financial services; consumer; service; crafts and burial societies; to mention just a few. They may also be classified as primary, secondary or tertiary (CIPC, 2017). To make the co-operative effective, members meet regularly to share detailed reports with each other and to elect directors from among themselves (Entrepreneur, 2009). The directors are responsible for employing managers to manage the day-to-day tasks, with the aim of serving the members' interests.

Financial co-operatives offer opportunities for financial inclusion to improve the socioeconomic profiles of a society and the participating individuals. Sauli (2020) states that CFIs provide many of the same products and services as traditional banks, but they differ in a number of ways: they do not seek to maximise profit, but rather serve their adherents, by whom they are owned. They generally have lower charges compared to commercial financial institutions, and any excess returns to the adherents as profit or investment share (Sauli, 2020). To emphasise the importance of financial co-operatives, Birchall (2013) argues that financial co-operatives are a much better alternative to commercial banks, especially at a time of financial crisis. During the 2008 financial crisis, for instance, commercial banks were reluctant to lend. However, co-operative banks and credit unions continued to serve their members and communities as they were more stable and did not need government bail outs.

Consequently, their assets, deposits and membership increased (Birchall, 2013; Roelants et al., 2012; Birchall & Hammond, 2009). This underlines the importance of this study of CFIs.

Despite the recognised importance of co-operative financial institutions (CFIs), and the opportunities they can provide to contribute to economic development in South Africa, they have faced numerous challenges, including:

• government challenges with changing regulations and legislative framework;

• market challenges such as competition, changing consumer behaviour and demand, globalisation etc.; and

• challenges in the co-operative organisational structures (Finmark Trust, 2014).

It is a fair assumption that South Africa has one of the most modern and sophisticated financial sectors in the world, using the latest information and communication technologies. However, the Bank Association South Africa (2017) states that financial inclusion remains a huge challenge facing South Africa. A large portion of the population does not benefit from the sector and "many communities in rural areas are living in poor conditions" (Van der Walt, 2008).

This article focuses on one aspect that has not been investigated before, of the many challenges that are faced by financial co-operatives in South Africa: the reasons for the low penetration of the sector which keep it very small. The study seeks to find what these could be, from the consumer point of view. Thus the objective of the study is to determine the reasons for the low penetration rate of South African CFIs by investigating the consumer awareness of CFIs' actions or strategies which may also indicate their entrepreneurial innovativeness.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Theoretical framework

Studies on co-operatives and CFIs and their contribution to financial inclusion across the world such as those of the South African Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) (2012), Peels (2013), Philip (2003), Finmark Trust (2014), Birchall (2013), the World Bank (2014), Kirsten (2006) and Hawkins (2009), report that the South African CFI sector remains small with a low penetration rate compared to other countries. These studies were the lens through which this study approached its theoretical inquiry into the reasons for the low penetration rate of the South African CFI sector.

2.1.1 Co-operatives and Co-operative Financial Institutions

According to the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA) (2015), whether the participants of co-operatives are the clients, workers or adherents, they possess the same decision-making power regarding anything the company organises, as well as a portion of the returns. The Alliance goes on to say that "as businesses driven by values, not just profit, co-operatives share internationally agreed principles and act together to build a better world through cooperation".

The South African Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) (2012) states that co-operatives, seen as a system of business, lean towards subsidising the global financial progress, when likened to other corporate systems. For example, the income of the world's biggest three hundred co-operatives surpasses US$1 trillion, equivalent to the world's 10th major economy; and co-operatives account for 25 percent of the coverage of the global marketplace and amount to 33 percent of the global dairy foods (DTI, 2012). This study focuses on co-operative financial institutions, in particular.

In his presentation of the International Labour Organisation's (ILO) report on the influence of financial co-operatives, Peels (2013) summarised their characteristics, highlighting the difference between investor-owned banks and CFIs. He reported that their essential foundations are proprietorship, governance and the welfare of CFIs (Peels, 2013). Clients own the co-operative - everyone with one member-share. The financial co-operative is not just the property of the present group of participants; it also belongs to future associates. Association is not movable: participants manage the financial co-operative and they are fully party to the administration of the institution (Peels, 2013). Members are the core recipients of the benefits since the bank's aim is to assist them, and not to maximise profit. According to these characteristics and operating principles, the aim of financial co-operatives should be the growth and development of their member-owners, as opposed to profit maximisation for shareholders, as is the case in investor-owned banks. This is an attempt to address the elusive issue of financial inclusion for financial co-operative members in particular, and society in general.

2.1.2 Financial inclusion

The Bank Association South Africa (2017) argues that "financial inclusion remains a huge challenge facing South Africa, with 12 million people, or 23.5 percent of the population, considered as financially excluded, and 9 percent informally served". In addition, the World Bank (2014) reports that 67 percent of the population in South Africa does not put money aside, even though most adults accept that saving is vital. Furthermore, among people who save, just 22 percent do it through standard networks.

Most of the studies on financial inclusion mentioned earlier (Philip, 2003; Finmark Trust, 2014; Birchall, 2013; DTI, 2012; The World Bank, 2014; Kirsten, 2006; Hawkins 2009) focus mainly on the access to financial services (often from commercial banks): having a bank account, doing transactions, borrowing, and so on. The launch of the Mzansi account in October 2004, aiming to extend financial services to small wage earners and others existing without the conventional financial services, created 1.5 million new bank accounts by May 2006 (Kirsten, 2006). However, it appears that many of these accounts are dormant with few, or no, transactions. By the end of 2008, it was estimated that "six million Mzansi Accounts had been opened, of which only 3.5 million were active" (The World Bank, 2014).

Financial co-operatives are believed to have the power to help people to achieve their financial emancipation and independence, which could be key to poverty eradication and community development. Low-income consumers need financial products that meet their needs and should be offered these at lower and more affordable costs. These consumers need to be educated and protected by government regulatory bodies, as well as by CFIs themselves.

2.1.3 International best practices

Co-operative financial institutions have had many successes internationally over the years. A few examples include those in Spain, Germany, Italy, Bangladesh, North America and Kenya. A study by the DTI of the successful models adopted by Italy, Canada, Spain, India, Kenya and Bangladesh, shows that, in each case, the state has taken a leading role in the development of the co-operative sector (DTI, 2012). However, the main responsibility to make the sector a success remains that of the co-operatives themselves. In Lithuania, Jaseviciene et al. (2014) found that effective advertising can help credit unions to attract new members and to choose certain strategies in order to create a credit union's public image. In North America, one of the key success factors (diversification) of a Canadian credit union is 'delivery channels', which focuses on enhancing the existing channels and developing new channels, such as wireless access and grocery store branches, so that the consumers can transact easily in any way they wish to (Schoemaker et al., 2002). In today's business world, many organisations have adopted corporate social responsibility activities to gain a better share of the market. In this regard, McWilliams et al. (2006) argue that CSR activities have been conceived to infuse social qualities or characteristics into goods and manufacturing methods, adopting changing human resource management practices, and pushing for the goals of community organisations. Differentiation is another strategy companies use to attract customers in this ever-changing market environment. For instance, Australia's first customer-owned bank, Bankmecu, appeals to young people through its e-statements, interactive mobile app, conversations on social media and its visual-centred, user-friendly branding (WOCCU, 2015). On the other hand, Mushonga et al. (2018) found that one of the factors inhibiting CFIs' performance was their inability to retain talent through competitive market salaries, leading to poor performance and lack of interest from the public.

The case of Kenya is more relevant for South Africa. The Kenyan co-operative and CFI sector appear to be the best African example of success. The country has a well-developed co-operative financial sector with many successes. With more than $2.133 billion US in assets and a savings collection of approximately $1.76 billion US, the SACCO society in Kenya accounts for a considerable share (about 20%) of the nation's savings (Gogo & Oluoch, 2017). Wanyama (2009) reports that the Kenyan Co-operative Bank is the fourth largest bank in the country. Key success factors of co-operatives in general include an enabling legislative environment; an independent ministry that drives the promotion of cooperatives with a substantial budget; strong partnerships between government and the cooperative movement; the provision of education and training for members through the Cooperatives College that was established in 1952; the provision of financial support for cooperatives through SACCOs and the National Co-operatives Bank of Kenya; a conflict resolution system; and decentralised implementation (DTI, 2012).

The Kenyan SACCO sub-sector comprises both deposit-taking (FOSA operating SACCOs) and non-deposit-taking SACCOs. At the end of December 2019, the number of registered deposit-taking SACCOs in Kenya was 163 (Kamau, 2020).

The WOCCU 2018 statistical report placed the Kenyan CFI sector as number one in Africa, with close to 8 million members and a 28.4 percent penetration rate; more than 5 billion US dollars in saving and shares; over 6 billion US dollars in loans; and just over 8 billion US dollars in assets (WOCCU, 2018).

SACCOs in Kenya are diversified, and that allows a good spread of the risk across different types of union members, industry sectors and geographical areas, such as Kenya Bus Services SACCO, Kenya Planters Co-operative Society and Kenya Creameries Cooperative (Wangui, 2010). Kenyan SACCOs have diversification strategies that broaden the credit risk in order to avoid a concentration of credit risk troubles. They also practise credit enhancement, where a SACCO strengthens its credit by buying credit security in the form of collaterals from financial guarantors, or through credit derivative products (Wangui, 2010). Findings from a study by Olando et al., (2012) indicated that the growth of Kenyan SACCOs' wealth relied on loan management, institutional strengths, and innovative services.

Kinyua et al. (2015) identified specific strategies that are applied to manage stakeholders' interests in Kenyan SACCOs, which have greatly contributed to their overall success. These strategies are briefly discussed below:

• Defensive strategies

Defensive strategies are management tools that can be used to counter an attack from a potential competitor (Kinyua et al., 2015).

• Offensive strategies

According to Fahri and Yannopoulos (2011), firms engage in offensive marketing strategies to improve their own competitive position by taking market share away from rivals. Offensive strategies may consist of direct and indirect attacks or moving into new markets to avoid current competitors. Smakalova (2012) emphasises that offensive strategies should be adopted if a stakeholder group has relatively high co-operative potential and relatively low competitive threat.

• Hold strategies

Hold strategies involve keeping position or programmes, and monitoring stakeholder factions for anything that may change in their point of view (Kinyua et al., 2015).

• Swing strategies

This applies to groups of stakeholders with high co-operative and high threatening abilities, with whom firms should collaborate to maximise their positive-influencing abilities and to minimise threatening abilities (Kinyua et al., 2015).

• Corporate social responsibility strategies

McWilliams et al. (2006) define corporate social responsibility (CSR) as situations where the firm goes beyond "compliance and engages in actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law". According to Kinyua (2016), CSR activities have been found to contribute to a better society, thus improving Kenyan SACCOs' image and contributing to their success.

• Use of technology and partnerships

Africa is the world's fastest growing mobile subscriber market and 70 percent of its population is under 35 years of age. Like many young adults worldwide, they are tech-savvy consumers seeking digital, convenient financial services that bring value to their lives (WOCCU, 2015). In Kenya, based on a World Council Developed Network that connects credit unions to the Safaricom's M-PESA platform (online mobile money), members are not only able to use M-PESA's standard payment services, but can also integrate their regular credit union accounts with the mobile interface (WOCCU, 2015).

2.1.4 Implication for South African CFIs

Can some of these successful models be adopted by the CFI sector in South Africa, resulting in a successful financial co-operative sector aimed at achieving decent living conditions, financial independence and, indeed, economic development for its communities? The answer may be yes. However, Satgar (2007) warns that "in practice the line between enabling support and autonomously developed co-operatives has to be constantly monitored such that, on the one hand, the bureaucracy does not capture these institutions and, on the other, the co-operatives themselves do not become dependent on state support". This paper argues that all should start with the people, or consumer education and proper marketing, and CFIs' engagement with communities, so that they can learn about CFIs, and the products or services and benefits they offer.

3. RESEARCH METHODS AND DESIGNS

This study's design and data collection method were determined by the need to gather enough data in order to investigate consumer knowledge about CFIs and their activities or strategies, involving marketing, education, partnerships, corporate social responsibilities, offensive strategies and differentiations. A quantitative research design was deemed appropriate to investigate these activities. This required an empirical study with data that was collected from participants through questionnaires.

3.1 Sample and sampling technique

The study population was the City of Tshwane - ordinary citizens from all walks of life. According to the population count based on the survey of 2016 (Statistics South Africa, 2018), the City of Tshwane has a population of approximately 3.275 million. The usual goal of survey research is to collect data representative of a population (Bartlett et al., 2001). Therefore, a simple random sampling method (probability sampling) was used for sampling.

This study used Cochran's formulae, as explained by Bartlett et al. (2001). Bartlett et al. (2001) suggest two formulae for calculating sample size: one for categorical data; and one for continuous data where categorical data do not play a primary role.

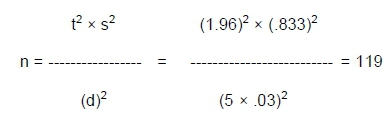

For continuous data, using an alpha level of .05 and a level of acceptable error of 3 percent (.03), Cochrane's sample size formula is shown (Bartlett et al., 2001):

where t = value for selected alpha level;

where s = estimate of standard deviation in the population; and

where d = acceptable margin of error for mean being estimated.

In total, 303 participants were surveyed between December 2019 and March 2020, which is in line with this sampling formula.

3.2 Data collection

Questionnaires were used to collect data for the study. According to Kuada (2012:107), "a questionnaire is the most predictable data collection tool used in surveys". Questionnaires were administered personally by the researcher to collect primary data from participants, in the streets and shopping centres of the City of Tshwane where ordinary citizens may be found. Bowling (2005) argues that the least burdensome method is the personal, face-to-face survey as this only requires the respondent to speak the same language in which the questions are asked, and to have basic verbal and listening skills. In some cases, willing participants, who did not have time to fill in the questionnaire right away, either collected a copy and returned it a few days later after completion, or requested a copy via email and sent the questionnaire back after completing it. The questionnaire included questions to measure consumer knowledge of, and engagement with co-operative financial institutions as well as consumer knowledge regarding actions taken by co-operative financial institutions. The six actions considered were marketing, offensive strategies, education, partnerships, corporate social responsibility and differentiation. Several questions were set for each action, and were inspired by other studies across the world such as those of Smakalova (2012), Kinyua et al. (2015), Fahri and Yannopoulos (2011), McWilliams et al. (2006).

3.3 Data analysis

Data were captured from the questionnaires in a spreadsheet, and then checked and cleaned. The tests that were used in the analysis were descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations; the chi-square goodness-of-fit-test; the binomial test; the one sample t-test; and factor analysis. For all questions with a five-point Likert agreement response scale, the one-sample t-test was applied to test for significant agreement/disagreement. In the same way, questions measured on a five-point semantic awareness scale were analysed to determine significant awareness or lack thereof. Questions with multiple response categories from which to choose were analysed using the chi-square goodness-of-fit test to identify which response option(s) were selected with significant frequency. The binomial test was applied to test if a significant proportion selected either of a possible two response options. Factor analysis was used to determine the overall construct validity of the model variables as applied to this set of data, and Cronbach's alpha was used to confirm the reliability of these composite measurements.

4. RESEARCH FINDINGS

The analysis started with the demographics of respondents. The results show that there was a higher percentage of male respondents (55.4%) compared to female respondents (44.6%). This may be due to the male gender of the researcher, as one would imagine that males would be more comfortable when approached in a public area by a male, than a female would be. It is also noted that most respondents were aged between 21 and 50 (86.2%). This may be explained by the fact that these age groups are the most active in the population and are more likely to be found in the streets and shopping centres. More than half of the respondents were formally employed (52.8%). The reason for this could be that this group understands better what research means, as many might have had to do some sort of research project during their studies, or as part of their work.

4.1 Consumer knowledge and engagement with CFIs

Respondents were asked to select one from a possible five options that indicated their level of awareness and knowledge of saving and credit co-operatives like village banks, credit unions or SACCOs. Results from a chi-square goodness-of-fit test show that a significant 164 (54.1%) had never heard of saving and credit co-operatives, p<.0005. A further 62 (20.5 %) respondents who had heard about them did not know what they are about. This means that almost 75 percent of the respondents did not know what they are about. This is not surprising, given that the literature had already indicated the very low penetration rate of the CFI sector in South Africa (WOCCU, 2018; Mushonga et al., 2018). The point is that people need to know about something to show interest in it.

The second and third questions that consumers were asked were to assess their knowledge of, and engagement with, CFIs: whether they were a member of any saving co-operatives; and if they had a savings plan with any saving co-operative. The results from a binomial test show that a significant 97 percent of respondents were not members of CFIs, p<.0005; and a significant 96 percent did not have a saving plan with any CFI, p<.0005. These findings again reflect that the financial co-operative sector in South Africa is very small with a low penetration rate (.01%), as mentioned earlier. Looking at the City of Tshwane, itself: according to Statistics South Africa (2018), its population, based on the latest survey of 2016, was estimated at around 3 275 000. There are four financial co-operatives based around the city, with a total membership of about 2056, based on the 2018 and 2019 updated lists (Table 1). This means that the percentage of CFI membership, compared to the city's population, is about 0.063 percent. This reflects the low percentage of CFI members who participated in this study. On the other hand, if most people do not know about them, one would not expect many to have any saving plans with them.

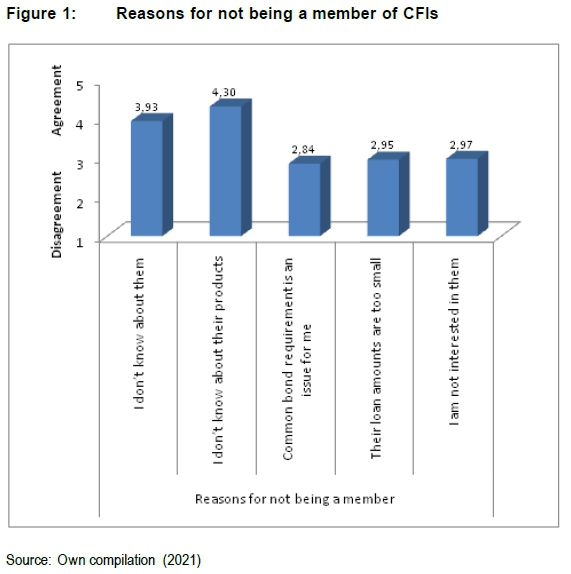

Other questions were directed only to participants who were not members of any CFI. They were asked to rate their agreement (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree) with items regarding reasons why they were not members. The average agreement with each statement is shown in Figure 1.

Results from a one-sample t-test reveal significant agreement that respondents did not know about CFIs, M=3.93, p<.0005; and that they did not know about CFIs' products, M=4.30, p<.0005. There was also significant disagreement that that the common bond requirement was an issue for respondents, M=2.84, p=.004. There was neither agreement nor disagreement with the other two items among the five possible reasons. The fact that most respondents agreed that they did not know about CFIs or their products explains the previous results - that most respondents were not members; and nor did they have accounts with them. Anstead (2008:8) argued that "gaining new members requires a two-step sale. First, people need to become aware of what credit unions are, and their eligibility to join. Only then can they be attracted by a specific credit union. In addition, the fact that disagreement with common bond is an issue for participants makes sense; as most people would want to engage financially with others that they know and trust.

Another set of questions was directed only to participants who were members of a CFI. They were asked to rate their agreement (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree) with items regarding reasons why they were members. Results from a one-sample t-test show that there was significant agreement among respondents who were members, or who had accounts, that they were attracted by the competitive prices of the products, M=3.91, p=002; and the fast speed of CFI services, M=3.90, p=.001. There was also a significant disagreement with the statement that they became members to win gifts in promotions, M=2.10, p=.004.

No prior study had been conducted on the reasons for the CFI sector in South Africa being very small, or for the low penetration rate. Nonetheless, many studies have looked at some of these items. A study by Auka and Mwangi (2013:61) found that "74 percent of the respondents were attracted to other financial institutions due to the quick service they received". Mushonga et al. (2018:262) found that, among other things, competitive pricing of loans by CFIs has a "positive economic impact as members' well-being improves". There was neither agreement nor disagreement with the other four items among the six possible reasons. Because the sample was so small, the results were confirmed using a non-parametric equivalent test - the Wilcoxon signed ranks test. No difference in the results was found.

More questions were asked to respondents who were members or who had accounts, as well as those who knew about CFIs, irrespective of whether they were members or had an account, regarding the products offered by CFIs to members or non-members. Seventy-seven respondents fell in these categories. Results from a binomial test show that a significant proportion of those who answered the questions said 'yes' to only four products on offer by CFIs: loans; savings accounts; investment accounts; and funeral plans. A very small number of participants responded to these questions. This may suggest that, even among the 25 percent (77) who said they knew about CFIs or were members, few knew whether CFIs offer these products. The fact that CFIs do not offer many products (according to the few respondents to the questions) may be due to them being small for the most part, with limited resources. Nevertheless, that also may be a reason for their low membership, as consumers would look for more product offerings, such as those they can get with commercial banks, albeit at a higher cost. Grameen Bank II of Bangladesh responded to member needs with more flexible products to encourage them to remain with the bank rather than leaving (Grameen Bank, 2018). Mushonga et al. (2018) findings echo this, as their respondents ranked highly the CFIs' ability to diversify financial services to meet member needs. The products offered and their awareness by members are shown in Table 1.

All participants were asked about their level of awareness of the benefits offered by financial co-operatives. The results from a chi-square goodness-of-fit test indicate that a significant number of respondents (210, 69.3%) did not know if there were benefits or not (to being a CFI member or having an account with them). This result should not be alarming as, once again, most respondents did not know about CFIs, making it understandable that they would not know what they might offer.

More questions were asked to respondents who were members, had accounts, or knew about CFIs (irrespective of being members or having an account), to assess their knowledge of the benefits that CFI products offer. The results from a binomial show that only three products had a significant number of respondents (who were members, knew about CFIs, or had accounts) saying 'yes' to knowing about or receiving them: 13 for good interest rates; 9 for low charges on saving accounts or purchases; and 7 for low interest on loans. Again, the very small number of participants who responded to these questions suggests that, even among the participants who said they knew about CFIs or were members, most did not actually know whether CFIs offered these benefits. The result may also suggest that there are many products that are not offered by CFIs, compared to those that are offered by mainstream financial institutions. The question is whether the CFIs are too small, and with very limited resources, to be able to afford to offer these services? Or are they not informed or innovative enough to know about products that are in demand and/or offered by the competition? Either way, how may this be detrimental to their growth?

Only respondents who were members, or had accounts, were asked to rate the speed of CFI services. The results show that about two third of the respondents rated CFI services as 'fast'. The results from a chi-square test demonstrate that a significant majority in this group of respondents (66,7%), rated the speed at CFIs as 'fast'. This is in line with these respondents' answers about the reasons why they were members, where the majority of them said the speed of the service was one of the reasons why they were members. Auka and Mwangi (2013) state that 61 percent of their SACCO members' respondents were attracted by other financial institutions because of the quality of service (which includes the speed of service).

4.2 Consumer awareness of CFIs' actions or strategies that indicate their entrepreneurial innovativeness

Part of the purpose of the study was to also investigate consumer awareness of CFIs' entrepreneurial and innovative activity. This activity was classified into six categories: marketing; offensive strategies; education; partnerships; corporate social responsibility; and differentiation.

4.2.1 Consumer awareness of CFI marketing activity

To investigate respondents' knowledge of CFI marketing activity, they were asked to rate their agreement (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree) with items regarding those actions or strategies. Results from a one-sample t-test in which the average agreement was tested against the central score of '3', reveal that there was significant disagreement with statements regarding respondents' awareness of any these strategies and actions. This should be expected, as most respondents did not know about CFIs, or the services they offer.

4.2.2 Consumer awareness of CFIs' offensive strategies

To test their knowledge of offensive strategies, respondents were asked to rate their agreement (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree) with items regarding these strategies. Results from a one-sample t-test show that there is significant disagreement that respondents are aware of any these strategies. Again, this is not surprising due to the fact that most participants lack knowledge about them.

4.2.3 Job offers by CFIs to members or account holders

Respondents who were either members of, or had accounts with, CFIs were asked whether they had ever been offered and/or taken a job at a CFI. Results from a binomial test show that a significant 83.3 percent had never been offered a job, p=.039. This question was also intended to test whether CFIs are using job offers as an offensive strategy to attract more membership. One would assume that members or account holders who have been offered a job might be more willing to spread the word about financial co-operatives, which would result in more people knowing about them and perhaps becoming members. Mushonga et al. (2018:263) found that one of the factors inhibiting CFI performance is their inability to retain talent through competitive market salaries. However, responses from participants do not seem to show that CFI are using job offers to members as part of their strategy to increase their membership base or performance.

4.2.4 Consumer awareness of CFIs' educational strategies

To test their knowledge of these strategies, respondents were asked to rate their agreement (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree) with items regarding these strategies. Results from a one-sample t-test show that there was significant disagreement, indicating that respondents are not aware of any these actions. This was also expected, as most of the participants lacked knowledge about CFIs.

4.2.5 Consumer awareness of CFIs' partnerships

To investigate these strategies, respondents were asked to rate their agreement (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree) with items regarding these actions or strategies. Results from a one-sample t-test indicate that there is significant disagreement that respondents are aware of any these actions. Again, this is not surprising, as most of the participants lacked knowledge about CFIs.

4.2.6 Consumer awareness of CFIs' corporate social responsibility activity

To assess this knowledge, respondents were asked to rate their agreement (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree) with items regarding this activity. Results from a one-sample t-test reveal that there was significant disagreement that respondents were aware of any of this activity. This is again in line with the fact that most participants lack knowledge about CFIs.

4.2.7 Consumer knowledge of CFIs' differentiation strategies

To investigate their knowledge/awareness of CFIs' differentiation strategies, respondents were asked to rate their awareness (from 1 = not at all aware, to 5 = extremely aware) about items concerning CFI differentiation strategies. A one-sample t-test, in which the average awareness score was tested against the central score of '3', was used to determine if there is significant awareness, or lack thereof, of each strategy. Results show that respondents were not aware of new products being introduced; new branches opening up; the diversity of products offered; or the ability to get a loan without collateral. This is also in line with the fact that most participants lacked knowledge about CFIs.

Factor analysis with Promax rotation was applied to explore the structure of the data. Items measured on a five-point Likert scale pertaining to the organisational strategies were included in the initial analysis. These included C10.1 - 10.8 (marketing); D11.1 - 11.4 (offensive strategies); E13.1 - 13.3 (education); F14.1 - 14.3 (partnerships); G15.1 - 15.5 (social responsibility); and H16.1 - 16.5 (differentiation). The factor loading results are shown in table 2.

During the analysis, items H16.2 and H16.4 were dropped because they cross-loaded onto multiple factors. In addition, item C10.8 was dropped because it did not load adequately onto any factor. Three factors were extracted and rotation converged in six iterations and are shown in Table 3.

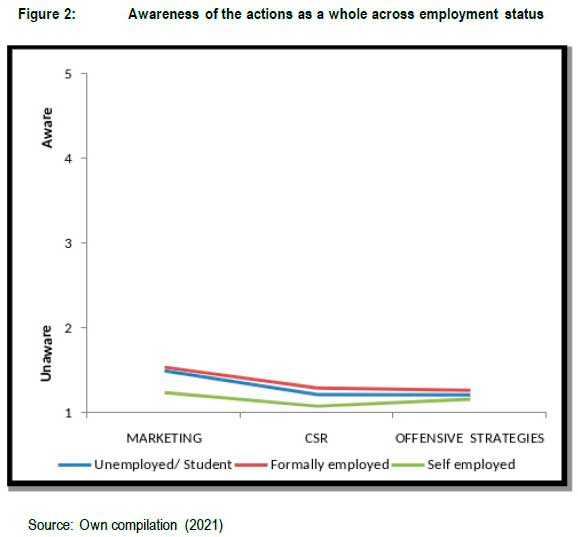

A Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) value of .902 indicates that a successful and reliable extraction process has taken place. In addition, significant results from a Bartlett's test indicate that the correlations between items are not too low for successful extraction to occur. The three factors account for 62.20 percent of the variation in the data. Cronbach's alpha was used to test the reliability of each factor, yielding the results: for Factor 1 (marketing), a=.915; for Factor 2 (CSR), a=.907; for Factor 3 (offensive strategies), a=.892. All three Cronbach alpha values are greater than the .7 minimum acceptable as mentioned earlier, confirming the reliability of each factor as a composite measurement. A one-sample t-test was performed on these composite measurements to test for significant awareness, or lack thereof, of the CFIs' actions, as represented by the three composite measurements. The results of the average awareness of the marketing, CSR, and offensive strategies are shown in Table 4.

Results from a one sample t-test show that there was a significant lack of awareness about each of these CFI activities (p<.0005). Analysis using ANOVA and Bonferroni's post hoc test shows that, while there was a significant lack of awareness of all three of these activities, there was significantly more awareness of marketing activity than the other two, p<.0005 in each case.

ANOVA was performed to test if there were significant differences in these awareness scores across gender, age, education and employment status. No significant differences were evident across gender, age and education. However, there were significant differences across employment status; and a Welch test was deemed appropriate to analyse this. The results revealed a significant difference in awareness of marketing activity across employment status: Welch (2, 165.656) = 7.527, p=.001. In particular, the Games-Howell post hoc test revealed that the self-employed were significantly less aware of this activity than the formally employed (p=.001) or the unemployed (p=.027). There was also a significant difference in awareness of CSR activity across employment status: Welch (2, 166.767) = 8.520, p<.0005. In particular, the Games-Howell post hoc test revealed that the self-employed were significantly less aware of this activity than the formally employed (p=.001) or the unemployed (p=.028). However, there was no significant difference in awareness of offensive strategies across employment status (p=.470).

Of interest here is that the self-employed group is less aware of CFI activity than the other respondents, especially the formally employed. This could suggest that the self-employed feel more secure financially, by being their own bosses, and are not interested in looking for more opportunities to diversify their income source. On the other hand, it could be that the formally employed are more aware of what is going on in society in general.

5. DISCUSSION

The study findings on consumer knowledge of, and engagement with CFIs have shown that a significant majority of respondents did not know about them or the services they offer, and/or do not have an account with any CFI. The issue of social capital (membership) cannot be overlooked within the CFI sector as it is of the utmost importance. This is supported by the findings of Mushonga et al. (2018) that the major drivers of CFIs' performance seem to be leveraging on social capital to eliminate poverty. Their findings concluded that:

Members are motivated to pool financial resources together so that they can lend back to members profitably, in a social way, where members enjoy ownership and control of the CFI effectively and are thereby able to strengthen the community common bond for social development through improved savings culture to help fight the debt trap caused by money lenders (Mushonga et al., 2018).

The fact that the majority of respondents who are members or who have accounts (66,7%) rate the speed of services at CFIs as 'fast' may suggest that CFIs would need to maintain and improve on this feature to retain members and maybe draw more through word-of-mouth advertising. It is a fact that, in today's world, no one is willing to wait for a long time to get any service, as consumers believe that enough technology is available to do things more quickly. While fast is good, one would imagine that very fast may be appreciated more by consumers. The study findings also show that a very limited number of products and benefits are offered by South African CFIs. Studies in countries with successful co-operative financial sectors show that CFIs diversified their products and benefits as they realised it was necessary to compete with commercial banks. For instance, successful credit unions in Canada offer products like free chequing accounts (Klug, 2007). Grameen Bank II of Bangladesh responded to member needs with more and flexible products, as mentioned earlier. US credit unions reconsidered their fixed rates on debit and credit cards (for variable rates), breaking with a long tradition (Moed, 2009). Ortiz (2005:6) adds that "in a bold attempt to attract new members and keep the old ones happy, Boeing Wichita Credit Union (in the USA) has eliminated all of its ATM surcharge fees". The other important finding of the study is the fact that a significant majority of respondents were not aware of any of the activities or strategies that may demonstrate CFIs' entrepreneurial innovativeness.

A study in Kenya (with the most successful CFI sector in Africa) by Kinyua et al. (2015) found that all these actions and strategies, both individually and combined, have a positive relationship with the performance of deposit-taking SACCOs. Other studies (Boysen & Sahlberg, 2008; Corcoran & Wilson, 2010; Paredes, 2008; WOCCU, 2018; Strandberg, 2010) show that these strategies have been used by CFIs in many other countries, notably the USA, Canada, Bangladesh, Spain and Kenya, to mention just a few. These countries have the best CFI sectors in the world, as mentioned earlier in this study. What could be the implications of all of that for South African CFIs?

6. THEORETICAL, PRACTICAL AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

Many studies have been conducted on co-operatives in general, and some on co-operative financial institutions in particular (Philip, 2003; Finmark Trust, 2014; Birchall, 2013; DTI, 2012; World Bank, 2014, Peels, 2013; Kirsten, 2006; Hawkins, 2009). Most of these studies focused on the financing and/or financing challenges of co-operatives. Some of them acknowledged that the penetration rate of South African CFIs is low compared to that in other countries. However, little literature (not to say none) exists on the reasons for this low penetration rate. Considering the above, this study's contribution to the body of knowledge would be twofold:

• Theoretical: The study findings will add new theory aiming at filling this gap, by proposing the reasons for the low penetration of the South African CFI sector.

• Practical: The research instrument questions may be used as an assessment tool that will be useful for CFIs, and also possibly for other micro-credit lenders, as it will assist in measuring the effectiveness of their innovation and entrepreneurial strategies, enabling them to initiate the necessary steps and training programmes to address any problems. The study may also serve as a wake-up call to other stakeholders, such as government and NGOs, to do more to help the sector address the problem.

• Managerial implications: The study findings have shown that a significant majority of respondents did not know about CFIs or the services they offer. This means that the management of the South African CFIs have not taken enough actions to expose them to the public for the latter to be aware of them and what they offer. Therefore, for the consumer to be aware of CFIs and their service offerings and consider becoming member, their management needs to be more agile and start doing things differently. This study could be helpful to them in their endeavours to change their image and attract more members to achieve the goal of financial inclusion.

7. CONCLUSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the reasons for the low penetration rate of South African CFIs by investigating consumer awareness of their entrepreneurial and innovative strategies. The most important findings from the study are the lack of knowledge about CFIs and what they have to offer, as well as the lack of awareness of their actions/strategies by a significant majority of the respondents. This suggests that CFIs around the City of Tshwane do not implement the strategies that have been used by CFIs in other countries to grow and improve the penetration rate of their membership; nor do they adopt enough of the strategies that show they are sufficiently entrepreneurial or innovative. The question is, how important might these strategies be for SA financial co-operatives?

8. LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE STUDIES

The main limitation of the study is that residents from only one metropolitan area were considered for the survey. Therefore, the results of the study may not be generalised to the entire country. However, the study will serve as the basis for a wider study in other regions of the country, and even internationally. It is recommended that research across the country, with a representative sample, be considered by other studies in order to generalise the findings to the entire country.

REFERENCES

Anstead, M. 2008. Awareness is first step to attracting new members. Credit Union Journal 12(15):8-8, April. [Internet :http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ukzn.idm.oclc.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=bf87ee05-7331-4b08-8b95-2cea3284ddfbpercent40pdc-v-sessmgr05; downloaded on 2020-04-09]. [ Links ]

Auka, D.O. & Mwangi, J.K. 2013. Factors influencing Sacco Members to Seek Services of Other Financial Service Providers in Kenya. International Review of Management and Business Research 2(2), June. [Internet: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.682.9917&rep=rep1&type=pdf; downloaded on 2020-02-18]. [ Links ]

Bank Association South Africa. 2017. Towards a financial inclusion strategy. [I nternet:http://www.banking.org.za/what-we-do/overview/towards-a-financial-inclusion-strategy; downloaded on 2017-06-1]. [ Links ]

Bartlett, J.E., Kotrlik, J.W. & Higgins, C.C. 2001. Organizational Research: Determining Appropriate Sample Size in Survey Research. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal 19(1), Spring. [Internet: https://www.opalco.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Reading-Sample-Size1.pdf; downloaded on 201911-08]. [ Links ]

Birchall, J. 2013. Resilience in a downturn: The power of financial cooperatives. [Internet: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/edemp/empent/coop/documents/publication/wcms207768.pdf; downloaded on 2017-06-22]. [ Links ]

Birchall, J. & L Hammond, K. 2009. Resilience of the cooperative business model in times of crisis. [Internet: https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/3255/1/Resilience%20of%20the%20Cooperative%20Business%20Model%20in%20Times%20of%20Crisis.pdf; downloaded on 2017-08-20]. [ Links ]

Boysen, V. & Sahlberg, R. 2008. The key success factors of Grameen bank: a case study of strategic, Cultural and Structural Aspects. MBA Thesis. Lund University. [ Links ]

Bowling, A. 2005. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. Journal of Public Health 27(3):281-291. [https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdi031]. [ Links ]

CIPC (Companies and Intellectual Property Commission). 2017. Types of co-operatives. [Internet: :http://www.cipc.co.za/index.php/register-your-business/co-operatives/types-co-operatvies/; downloaded on 29-01-2018]. [ Links ]

Corcoran, H. & Wilson, D. 2010. The Worker Co-operative Movements in Italy, Mondragon and France: Context, Success Factors and Lessons. Canadian Worker Co-operative Federation.[Internet: http://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/paper-corcoran-wilson.pdf; downloaded on 2018-04-18]. [ Links ]

Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). 2012. Promoting an integrated co-operative sector in South Africa 2012 - 2022. [Internet: strategy.pdf; downloaded on 2017-12-18]. [ Links ]

Entrepreneur. 2009. What should I know about a Co-operative before registering one and how do I Go about it? [I nternet:http://www.entrepreneurmag.co.za/ask-entrepreneur/doing-business-in-sa-ask-entrepreneur/what-should-i-know-about-a-co-operative-before-registering-one-and-how-do-i-go-about-it/; downloaded on 2019-05-04]. [ Links ]

Fahri, K. & Yannopoulos, P. 2011. Impact of market entrant characteristics on incumbent reactions to market entry. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 19(2):171-185. [https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2011.557741 ]. [ Links ]

Finmark Trust. 2014. Understanding financial co-operatives: South Africa, Malawi and Swaziland. [Internet:http://www.finmark.org.za/wp-content/uploads/pubs/RepFinancial-Co-operatives20142.pdf; downloaded on 2015-12-15]. [ Links ]

Gogo, P.A. & Oluoch, O. 2017. Effect of Savings and credit co-operative societies' financial services on demand for credit by members: a survey of deposit taking SACCOS in Nairobi. International Journal of Social sciences and information technology 3(8):2410-2421. [Internet: https://www.ijssit.com/main/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Effect-Of-Savings-And-Credit-Co-Operative-Societies-Financial-Services-On-Demand-For-Credit-By-Members.pdf; downloaded on 2019-06-17]. [ Links ]

Grameen Bank. 2018. About us. [Internet: https://www.grameen-info.org/about-us/; downloaded on 2020-03-05. [ Links ]].

Hawkins, P.A. 2009. Measuring consumer access to financial services in South Africa. [Internet: http://www.bis.org/ifc/publ/ifcb33ac.pdf/; downloaded on 2017-10-17]. [ Links ]

International Co-Operative Alliance. 2015. What is a co-operative? [Internet: http://ica.coop/en/whats-co-op/co-operative-identity-values-principles/; downloaded on 2018-12-15. [ Links ]]

Jaseviciene, F., Kedaitis, V., & Vidzbelyte, S. 2014. "Credit unions' activity and factors determining the choice of them in Lithuania." Ekonomikano 93:117-130. [Internet: https://etalpykla.lituanistikadb.lt/object/LT-LDB-0001:J.04~2014~1447862679313/J.04~2014~1447862679313.pdf; downloaded on 2020-06-19]. [ Links ]

Kamau, N. 2020. List of Saccos in Kenya. [Internet: https://www.kenyans.co.ke/news/36418-list-all-legitimaly-registered-saccos-kenya; downloaded on 2020-02-04]. [ Links ]

Kinyua, J.M. 2016. Stakeholder Management Strategies and Financial Performance of Deposit Taking SACCOs in Kenya. Nairobi: Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (PHD thesis. [ Links ]).

Kinyua, J.M., Amuhaya, M.I. & Namusonge, G.S. 2015. Stakeholder Management Strategies and Financial Performance of Deposit Taking SACCOs in Kenya. International Journal of Business and Social Science 9(1):139-158, September. [Internet: https://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol6No91September 2015/14.pdf; downloaded on 2018-01-25]. [ Links ]

Kirsten, M. 2006. Policy initiatives to expand financial outreach in South Africa. World Bank/Brookings Institute. (Conference paper; 30-31 May. [ Links ]).

Klug, W.E. 2007. A critical analysis of a credit union's strategic plan. Burnaby. Simon Fraser University. (Master's thesis. [ Links ]).

Kuada, J. 2012. Research methodology: A project guide for university students. Samfundslitteratur. E-book. [internet:https://books.google.co.za/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tuQMQydu8C&oi=fnd&pg=PA9&ots=7TW4Gr964t&sig=OH-ASf4PVRnoN5tqtFoaCC59dm8&rediresc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false; downloaded on 201911-22]. [ Links ]

Mcwilliams, A., Siegel, D.S. & Wright, P.M. 2006. Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategic Implications. Journal of Management Studies 43(1):1-19. January. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00580.x. [ Links ]].

Moed, J. 2009. CU Is Spelling Out Success. Credit Union Journal 13(35):1-26. [ Links ]

Mushonga, M. Arun, T.G. & Marwa, N.W. 2018. Drivers, inhibitors and the future of co-operative financial institutions: A Delphi study on South African perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 133:254-268. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.04.028]. [ Links ]

Olando, C.O., Jagongo, M.O. & Mbewa, A. 2012. Financial Practice as a Determinant of Growth of Savings and Credit Co-Operative Societies' Wealth (A Pointer to Overcoming Poverty Challenges in Kenya and the Region). International journal of Business and social science 3(24):204-219. [Internet: http://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol3No24SpecialIssueDecember2012/22.pdf; downloaded on 201810-24]. [ Links ]

Ortiz, L. 2005. ATM Fee Waiver Aimed at Attracting New Members. Credit Union Journal 9(28):6-6. [Internet: http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ukzn.idm.oclc.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=8&sid=bf87ee05-7331-4b08-8b95-2cea3284ddfbpercent40pdc-v-sessmgr05; downloaded on 2020-04-09]. [ Links ]

Paredes, O.C. 2008. Ecuador: Savings Mobilization in 14 Credit Unions. [Internet: https://www.woccu.org/documents/Ch 8; downloaded on 2017-03-30]. [ Links ]

Peels, R. 2013. Resilience in a downturn: The power of financial cooperatives. [Internet:https://www.globalcube.net/clients/eacb/content/medias/events/2nd_Day_with_Academics_and_Stakeholders/Presentations/Rafael Peels_ILO_13.05.2013_III.pdf; downloaded on 2016-12-16]. [ Links ]

Philip, K. 2003. Co-operatives in South Africa: Their Role in Job Creation and Poverty Reduction. [Internet:http://waqfacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Kate-Philip-KP.-102003.-Co-operatives-in-South-Africa-Their-Role-in-Job-Creation-and-Poverty-Reduction.-South-Africa.-Kate-Philip.pdf; downloaded on 2016-12-16]. [ Links ]

Roelants, B., Dovgan, D., Eum, H. & Terrasi, E. (2012).The resilience of the cooperative model. [Internet: http://www.cecop.coop/IMG/pdf/reportcecop2012enweb.pdf/; downloaded on 2018-04-09]. [ Links ]

Satgar, V. 2007. The state of the South African cooperative sector. [Internet: http://www.copac.org.za/files/Statepercent20ofpercent20Cooppercent20Sector.pdf; downloaded on 201610-15]. [ Links ]

Sauli, N. 2020. CFI start up guide. [Internet: http://www.treasury.gov.za/coopbank/CFIpercent20startpercent20uppercent20guide.pdf/; downloaded on 2020-08-20]. [ Links ]

Schoemaker, P. J. H., Hofheimer, G., Randall, D., Parayre, R. & Schuurmans, F. (2002). Key Success Factors: How to Thrive in the Future. Credit Union Executives Society. [Internet: https://www.cues.org/repository/keysuccessfactors.pdf; downloaded on 23-04-2020]. [ Links ]

Smakalova, P. 2012. Generic Stakeholder Strategy. Economics and Management 17(2): 659-663. [https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.em.17.2.2195]. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. 2018. City of Tshwane population. [Internet: http://cs2016.statssa.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Gauteng.pdf; downloaded on 2019-11-22. [ Links ]].

Strandberg, C. 2010. Credit union social responsibility: a sustainability road map policy brief. [Internet:https://filene.org/assets/pdf-reports/207StrandbergSustainabilityRoadMap.pdf; downloaded on 2017-04-01]. [ Links ]

The World Bank. 2014. Financial Inclusion: international bank for reconstruction and development. [Internet: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTGLOBALFINREPORT/Resources/8816096-1361888425203/9062080-1364927957721/GFDR-2014CompleteReport.pdf; downloaded on 2017-1220]. [ Links ]

Van Der Walt, L. 2008. Collective entrepreneurship as a means for sustainable community development: a cooperative case study in South Africa. [Internet: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/631/63111251001.pdf; downloaded on 2018-01-14]. [ Links ]

Wangui, G.M. 2010.The relationship between credit scoring practices by commercial banks and access to credit by small and medium enterprises in Kenya. Unpublished MBA project University of Nairobi. [ Links ]

Wanyama, F.O. 2009.Surviving liberalization: the cooperative movement in Kenya. Dar-salaam. (Coop AFRICA Working Paper No.10. [ Links ]).

WOCCU. 2015. International lessons for young adult membership growth. Technical guide. [Internet: https://www.woccu.org/documents/young-adult-tech-guide-hi-res; downloaded on 2020-04-16]. [ Links ]

WOCCU. 2018. Statistical report. [Internet: https://www.woccu.org/documents/2018StatisticalReport; downloaded on 2020-02-15]. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author