Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Contemporary Management

On-line version ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.19 n.1 Meyerton 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcm20123.133

ARTICLES

The Theory of Planned Behaviour as a model for understanding Entrepreneurial Intention: The moderating role of culture

Sipho MfaziI; Roger Michael ElliottII,

IDepartment of Business Management, University of Fort Hare. Email: Mfazisipho@gmail.com; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1996-0565

IIDepartment of Business Management, University of Fort Hare. Email: RElliott@ufh.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9081-9973

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: The aim of this study was to examine the moderating influence of culture on the intention to become an entrepreneur within the context of the Theory of planned behaviour

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: A survey was conducted using convenience sampling in which a sample of 316 students was selected from a South African university. The respondents were clustered (using K-means clustering) into three cultural groups, using Hofstede's cultural dimensions as criteria, after which the moderating influence of these cultural groups on the TPB was analysed using the Process macro for SPSS. Prior to this, the validity and reliability of the constructs were assessed. One of the independent variables (Perceived behavioural control) did not exhibit adequate levels of validity and was not considered in empirical analysis

FINDINGS: Personal attitude had a significant and direct influence on the dependent variable, Entrepreneurial intention. Although there was no significant relationship between Subjective norms and Entrepreneurial intention, there was a significant interaction effect by one of the cultural groups on the relationship between these two variables. This implies that Subjective norms have a greater influence on Entrepreneurial intention for members of this group than that of any of the other groups

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: Accordingly, the study does offer support for the argument that culture influences entrepreneurial behaviour. Moreover, this study confirms that the conceptualisation of contemporary culture needs to be reconsidered and that significant sub-cultures may exist within nations

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The findings suggest that mentorship programmes (or facilitating the engagement with role-models) may be effective strategies to encourage entrepreneurship as a career option for young adults

JEL CLASSIFICATION: L26, M13, Z10

Keywords: Culture; entrepreneurial intention; entrepreneurship; Moderation; Theory of Planned Behaviour.

1. INTRODUCTION

Entrepreneurial firms are able to generate innovative solutions, increase competition, fill market gaps and promote the efficient allocation of labour and capital (Urban & Ratsimanetrimanana, 2015; Ferreira et al., 2019; Palmer et al., 2021). Consequently, entrepreneurship is an important field of study within the context of developing countries (such as South Africa) because of its potential to stimulate economic development and in so doing overcome the challenges of poverty and unemployment (Littlewood & Holt, 2018; Ndofirepi & Rambe, 2018; Roy et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2018; Meyer & Meyer, 2020).

One way of understanding the drivers of entrepreneurship is the use of appropriate frameworks (Mothibi & Malebana, 2019). In this regard, the Theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) is accepted as a highly effective predictor of a wide range of behaviours (Adekiya & Ibrahim, 2016; Botha & Bignotti, 2017; Fatoki, 2019) including that of entrepreneurship (Kautonen et al., 2015; Kim-Soon et al., 2016). While the Theory of planned behaviour (and the other intention based models) focuses on individual factors, there is mounting awareness about the influence that contextual factors such as culture (Anlesinya et al., 2019; Hofstede, 1980) may have in facilitating (or hindering) levels of entrepreneurship (Alexander & Honig, 2016; Shiri et al., 2017; Palmer et al., 2019; Covin et al., 2020).

Culture (which has been described as a collective programming of the mind) is a nebulous concept that allows groups of people to be distinguished (Urban & Ratsimanetrimanana, 2015). Culture includes the values, knowledge, beliefs, morals, habits and expected behaviour that are common across people from a particular social structure (Adekiya & Ibrahim, 2016; Ebewo et al. 2017; Mwiya et al., 2017). As such, culture influences the perceptions of individual members of societies through their interpretative and cognitive processes (Vershinina et al., 2018) and may have a direct (or indirect) influence on the levels of entrepreneurship.

The impact of culture on entrepreneurial activity has been a source of conjecture for some scholars (Vershinina et al., 2018; McClelland, 1961; Schumpeter, 1934). Some (Darley & Blankson, 2020; Pecly & Ribeiro, 2020) argue that culture is the leading factor which explains differing levels of entrepreneurial activity between nations and this argument is supported by studies that have found that nations can differ significantly in productivity, inventiveness, and innovation (Irene, 2016; Liu et al., 2019). This implies that individuals might be predisposed towards entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviours depending on their society's socio-cultural structure and value systems (Vershinina et al., 2018; McClelland, 1961; Schumpeter, 1934). However, culture and entrepreneurship are both elusive, multi-dimensional phenomena making comparative research complex (Doe et al., 2016; García-Cabrera & García-Soto, 2017; Naqvi & Siddiqui, 2020; Mardisetosa et al., 2020) and this could possibly explain the equivocal nature of the results exploring this link (Laskovaia et al., 2017). This conundrum is compounded in South Africa (Mothibi & Malebana, 2019) as research considering this link within the context of developing nations (Anlesinya et al., 2019; Ebewo et al., 2017; Neira et al., 2017; Shiri et al., 2017) and in particular the African continent (Iwu et al., 2016) is inadequate.

As mentioned above, the Theory of planned behaviour is a useful framework for juxtaposing the influence of culture on entrepreneurship (Adekiya & Ibrahim, 2016; Stephan & Pathak, 2016). Consequently, the research question which this study seeks to answer is: To what extent does culture moderate the influence of the independent variables contained in the Theory of planned behaviour (Personal attitude, Subjective norms and Perceived behavioural control) on the intention to become an entrepreneur?

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature review firstly considers the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) after which the role of culture as a factor which might moderate the influence of the independent variables (Personal attitude, Subjective norms and Perceived behavioural control) on the intention to become an entrepreneur is considered. Lastly, the choice of Hofstede's (1980) dimensions (Individualism/collectivism, Power distance, Uncertainty avoidance and Masculinity/femininity) as the basis for the study is justified.

2.1 Theory of Planned Behaviour

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) is an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). The TRA is based on the premise that an individual's behaviour can be predicted by the intention to perform a particular behaviour (Ali & Abou, 2020; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The intention is influenced by Subjective norms (the extent to which a person perceives that people important to them think that the behaviour should be performed) and Personal attitude (the extent to which an individual feels positively or negatively predisposed to performing a behaviour) (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Neneh, 2020).

The TRA assumes a freedom to act without limitation whereas there are often constraints in terms of ability, time, social norms and financial resources (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Meyer, 2018; Neneh, 2020). Consequently, the TRA was extended (and named the TPB) by adding a further construct, Perceived behavioural control, to allow for situations where an individual is constrained by the perceived lack of access to opportunities and/or resources (Ajzen, 1985). The TPB has been extensively used to understand the (personal and social) antecedents to the dependent variable, Entrepreneurial intention, which for the purposes of this study is operationalised as the formation of an intention to start an entrepreneurial venture (Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018; Urban & Ratsimanetrimanana, 2015). These constructs are considered below.

2.2 Entrepreneurial intention

Behaviours such as opening up an entrepreneurial venture are volitionally controlled and can to a large extent be predicted by intentions (Johara et al., 2017; Najafabadi et al., 2016; Sadat & Lin, 2020; Strydom et al., 2021). Entrepreneurial intention is defined as a realistic aim (and plan) of an individual to start a new business (Bogatyreva et al., 2019; Fatoki, 2019) which implies that new venture formation is a deliberate and carefully planned intentional behaviour. This is the initial step in the process of unearthing and capitalising on opportunities (Shah et al., 2020) and a precursor to any entrepreneurial behaviour (Ajzen, 1985).

2.3 Personal attitude

Attitudes reflect the extent to which an individual has an unfavourable or favourable evaluation of an anticipated behaviour (Shah et al., 2020). As such, Personal attitude is determined by the beliefs about the outcomes and consequences (extrinsic or intrinsic) associated with the behaviour (Ajzen, 1991; Alexander & Honig, 2016) and is indirectly influenced by social norms (such as culture) (Liu et al., 2019). This implies that a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship will strengthen an individual's intention to open an entrepreneurial enterprise (Kautonen et al., 2015; Roy et al., 2017; Sadat & Lin, 2020) even if the possible behaviour might be remote, as is the case with that of university students (Bo, 2017).

Consequently, it is hypothesised that:

H1: Personal attitude will have significant influence on Entrepreneurial intention

2.3.1 Subjective norms

Social pressure can influence the extent to which an individual forms an intention to behave in a certain manner. In terms of the TPB, Subjective norms comprise two components: normative beliefs, (the perception about family and friends' expectations) and motivation (the need to comply with what people expect) (Ajzen, 1991; Fatoki, 2019). As such it has been argued that Subjective norms reflect the perceptions that an individual has about the values contained in their immediate environment which may include the cultural values of their group (Ajzen, 1991; Sadat & Lin, 2020). Consequently Subjective norms can have a direct influence on the formation of an entrepreneurial intention (Alexander & Honig, 2016; Debarliev et al., 2015). Therefore, it is hypothesised that:

H2: Subjective norms will have significant influence on Entrepreneurial intention

2.3.2 Perceived behavioural control

Perceived behavioural control refers to the individual's perceptions about their ability to perform a particular behaviour (Malebana & Swanepoel, 2015) and is an exogenous variable which influences both intention and behaviour (Kautonen et al., 2015; Shiri et al., 2017). While the nature of Perceived behavioural control may differ depending on the context, for the purposes of this study Perceived behavioural control is understood as the extent of an individual's faith in their ability to leverage human, social and financial resources necessary to start an entrepreneurial enterprise (Botha & Bignotti, 2017) and as such is the perceived difficulty or ease of starting a business (Ajzen, 1991; Alexander & Honig, 2016; Shiri et al., 2017; Urban & Ratsimanetrimanana, 2015).

Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Perceived behavioural control will have significant influence on Entrepreneurial intention

2.4 Culture

Initially culture was regarded as synonymous with nationhood (Mazanec et al., 2015; Urban & Ratsimanetrimanana, 2015; Valliere, 2017). One criticism of this approach is that it is based on the premise that nations constitute distinct cultural units (Darley & Blankson, 2020) which ignore the intracultural variations found within nations (Bogatyreva et al., 2019). Multiculturalism is a feature of contemporary nations (García-Cabrera & García-Soto, 2017) and factors such as technology, social media, immigration and globalisation have added momentum to this trend (García-Cabrera & García-Soto, 2017; Urban & Ratsimanetrimanana, 2015). This phenomenon has led not only to different sub-cultures co-existing within the same (legal) nation (Beugelsdijk & Welzel, 2018) but also across several different countries (Al-Alaw & Alkhodari, 2016; Beugelsdijk et al., 2017; de Mooij & Beniflah, 2017; Zhou & Kwon, 2020).

In order to understand national culture a number of different cultural theories and measures were developed (Douglas, 1973; Hofstede, 1980; Hall, 1990; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961; Schwartz, 1992; Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, 1997). Although there is some overlap in terms of the dimensions proposed by the different theories (Eringa et al., 2015), the seminal study in terms of the study of culture is that of Hofstede (1980) in which he originally proposed four dimensions (Power distance, Individualism/collectivism, Masculinity/femininity and Uncertainty avoidance) and subsequently Zhou & Kwon (2020) added a number of other dimensions (for example Long-term/short-term orientation and Indulgence/restraint) However, these have been criticised on the basis that they are culturally biased, redundant (in that some of the aspects are already captured in the original four dimensions), and lacking empirical support (Qelikkolm, et al., 2019). Hofstede's (1980) original dimensions have also been criticised as being outdated and their relevance questioned in terms of the understanding of contemporary culture (Ladhari et al., 2015; Straub et al., 2020). Notwithstanding their limitations, Hofstede's (1980) dimensions have been used as the basis for most cultural studies (Calza et al., 2020) relating to entrepreneurship (Zhou & Kwon, 2020). These dimensions are considered below.

2.4.1 Power distance

Power distance, for the purposes of this study, refers to the way that power is distributed in societies, and the extent to which the less powerful accept that power is distributed unequally (Hofstede, 1980). As with all of Hofstede's dimensions, this construct is conceived as a continuum, with high levels of Power distance indicating the acceptance that power is distributed unequally and vice versa. African cultures, argue Nyambegera et al. (2016), are characterised by high levels of Power distance which are typically associated with experience and age. However, the perception that status, age or gender (Naqvi & Siddiqui, 2020) endow individuals with an inherent wisdom or knowledge may impact on the extent to which the young people believe that they are capable of starting a business (Alexander & Honig, 2016). As such, people from cultures that are characterised by high levels of Power distance may not be positively predisposed to engaging in the "creative destruction" (Schumpeter, 1934) which often characterises the entrepreneurial process. This may explain why studies (García-Cabrera & García-Soto, 2017; Valliere, 2017; Vershinina et al., 2018) have found a negative correlation between high levels of Power distance and entrepreneurial intention.

2.4.2 Individualism-collectivism

The concept of Individualism-collectivism in this study is conceived as a continuum with collectivism (with its emphasis on group values and social cooperation) on the one end and individualism (which emphasises values such as the uniqueness of the individual, independence and self-sufficiency) on the other (Hofstede, 1980). This dimension relates to the extent to which individuals identify themselves separately or as part of the group's social context or, put differently, the relative importance of an individual's interest versus that of the group (Valliere, 2017). Typically, African culture is perceived as being dominantly collectivistic because Africans identify themselves within the context of a group, extended family or a clan rather than as a "standalone" individual (Nyambegera et al., 2016).

Individualistic cultures empower entrepreneurs by encouraging the traits of self-confidence, initiative and risk taking. As such, societies that have a culture that promotes individualism are tolerant of the independent vision that is necessary for initiating and sustaining a new business venture (Stephan & Pathak, 2016). Paradoxically, while individualism is important to initiate a new business venture, a collectivist approach is needed to muster resources and coordinate stakeholders which is also a critical factor in the formation of a new enterprise (Ebewo et al., 2017; Mothibi & Malebana, 2019).

2.4.3 Masculinity/femininity

This dimension (Hofstede, 1980) is defined as the extent to which a society values the traditional male values of ambition and achievement over values (typically associated with females) such as nurturing and interpersonal harmony (Beugelsdijk et al., 2017). Masculine value dominated societies tend to promote the significance of material possessions and money while cultures with a significant feminine emphasis embrace the values of social relevance, the welfare of others and quality of life (Beugelsdijk & Welzel, 2018). In addition, societies in which there is a strong masculine emphasis value independence and assertiveness (Zhou & Kwon, 2020) and social gender roles are more distinct than in feminine societies (Adekiya & Ibrahim, 2016). Some (Urban & Ratsimanetrimanana, 2015; Hofstede, 1980; Irene, 2016) argue that people from masculine dominated societies are socialised to be independent, strong and ambitious, attributes typically associated with entrepreneurial behaviour. As such, it would be expected that masculine dominant societies would be more entrepreneurial (García-Cabrera & García-Soto, 2017; Nyambegera et al., 2016; Valliere, 2017) although there are findings to the contrary (Lounsbury et al., 2019; Trevino, 2020).

2.4.4 Uncertainty avoidance

Uncertainty avoidance is defined by Hofstede (1980) as the extent to which individuals in a society are tolerant of uncertainty or ambiguity (Hofstede, 1980). Societies characterised by high levels of Uncertainty avoidance will be uncomfortable confronting unknown, novel or surprising situations (Neira et al., 2017). This dimension is important in entrepreneurship studies because of the theoretical link between the tolerance of uncertainty and risk taking (Beugelsdijk et al., 2017; Laskovaia et al., 2017; Valliere, 2017) which implies that individuals with a low Uncertainty avoidance will show a greater propensity to start up new businesses (Calza et al., 2020). Although the link between the ability to cope with uncertainty and entrepreneurial activity has empirical support (Naqvi & Siddiqui, 2020; Canestrino Cwiklicki, Magliocca & Pawelek, 2020), there are findings to the contrary (Lee & Kelly, 2019; Mutiara et al., 2019).

2.5 Culture and the Theory of planned behaviour

In general, international studies have found that entrepreneurial activity will be promoted by cultures that are high in individualism, low in power distance, low in uncertainty avoidance and high in masculinity (Adekiya & Ibrahim, 2016; Valliere, 2017; Urban & Ratsimanetrimanana, 2015). These links between Hofstede's (1980) cultural values and entrepreneurship have largely been mirrored in South Africa where high levels of individualism have been associated with entrepreneurial intentions (Naqvi & Siddiqui, 2020). There are however opposing views which claim that moderate levels of individualism (as opposed to collectivism) will lead to greater levels of entrepreneurial activity (Bogatyreva et al., 2019; Iwu et al., 2016; Vershinina et al., 2018). The cultural values that have been identified as limiting entrepreneurial behaviour in sub-Saharan Africa are excessive collectivism and high power distance (Mothibi & Malebana, 2019). However, individuals who are collectivists or socially-oriented tend to pay more attention to social pressure (Subjective norms) when compared to those individuals who value individualism (Iwu et al., 2016; Pecly & Ribeiro, 2020). As such it is argued collectivism has the ability to positively moderate the relationship between Subjective norms and intention to open a business. The influence is stronger (weaker) under conditions of high (low) collectivism (Adekiya & Ibrahim, 2016; Alexander & Honig, 2016).

It is apparent from the paragraph above that many of the studies consider the cultural dimensions independently and this is one of the major quandaries in the study of culture, (Irene, 2016; Mutiara et al., 2019; Shiri et al., 2017; Valliere, 2017; Williams & McGuire, 2010). The difficulty with this approach (selectively picking certain dimensions) is that it could lead to omitted variable bias and endogeneity. Similarly, it is argued that, because culture can be conceptualised as a system of common values (Calza et al., 2020), all the components (dimensions) should be included in the analysis to get a realistic view (Celikkol et al., 2019) of how culture will affect the level of entrepreneurship (Alexander & Honig, 2016).

As cultural values change, so do individuals' perceptions of risk taking behaviour such as the formation of a new enterprise. This has resulted in calls to re-examine Hofstede's constructs within the context of contemporary values and behaviour (Ladhari et al., 2015) and in so doing overcome the lack of dynamism in Hofstede's conceptualisation of culture (Eringa et al., 2015; Ladhari et al., 2015; Signorini et al., 2009). This study attempts to answer the call (Eringa et al., 2015) to reimagine the measurement of culture. As such this study will cluster respondents together on the basis of the scores of all of Hofstede's (1980) dimensions, not just one of them. This will allow those who show similar patterns of cultural adherence to be grouped together.

This is consistent with the approach that cultural adherence and social learning (Richter et al., 2016) can predict entrepreneurial behaviour.

As such, the main aim of the study is to investigate the extent to which grouping individuals on the basis of all of Hofstede's (1980) dimensions will moderate the Theory of planned behaviour.

Consequently, the following hypothesis is formed:

H4:Membership of a cultural group will moderate the relationship between Entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents (Personal attitude, Subjective norms and Perceived behavioural control).

This implies that there are three sub-hypotheses:

H4.1Membership of a cultural group will moderate the relationship between Personal attitude and Entrepreneurial intention.

H4.2Membership of a cultural group will moderate the relationship between Subjective norms and Entrepreneurial intention.

H4.3Membership of a cultural group will moderate the relationship between Perceived behavioural control and Entrepreneurial intention.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This section will cover the research design and the sample.

3.1 Research design

Initially sampling adequacy was assessed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity tests. The initial step of the data analysis process was an assessment of the research instrument's discriminant validity and reliability. Discriminant validity was assessed using exploratory factor analysis and the reliability of the instrument was assessed by calculating the Cronbach's alpha coefficient for all the factors.

The K-means technique of cluster analysis, using the cultural dimensions of Hofstede (1980), was used to group the respondents on the basis of the similarity of their cultural values. This is a centroid based approach (as opposed to a hierarchical method) which uses a centroid to define the clusters and objects that are placed in the cluster with the centroid closest to the objects (Lorentz et al., 2016).

The moderation effect was assessed using the SPSS Process macro (Version 3.4) developed by Hayes (2018). This regression based approach can be used for estimating both direct and indirect effects and as such it can be used to test hypotheses relating to both the direct and contingent effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable (Hayes, 2018). There are a number of statistical techniques that can be used in order to test conditional indirect effects such as Baron and Kenny's (1986) traditional multistep method (Cameron Cockrell & Stone, 2010; Zhang et al., 2009) and Sobel's (1982) test (Litzky et al., 2009; Yunis et al., 2017). However, these approaches assume a normal distribution of the underlying effect, and because the sampling distribution of indirect effects is often skewed, this underlying assumption is often violated. By contrast Process does not assume a normal distribution and overcomes this dilemma by using bootstrapping (Hayes, 2009).

3.2 Sample

The respondents were selected from the student body of the University of Fort Hare using the mall intercept method and, of the 361 respondents who completed the questionnaire, 50.1 percent were males and 49.9 percent females. Most of the students were undergraduates (47.6%) with the balance being postgraduate students. The background of students was proportionately distributed with most of the students coming from rural areas (34.9%), followed by those who grew up in peri-urban areas (34.3%) and with 30.7 percent emanating from urban areas.

The focus on students is justified by the finding that young individuals' studying at tertiary educational institutions have a higher propensity to start a business when compared to their counterparts (Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018; Roy et al., 2017). This may be because a decision about a career path for most students is inevitable and, while starting a business may well be an option, those already employed may be less inclined to change career (Irene, 2016).

4. EMPIRICAL RESULTS

Firstly, the validity and reliability of the instruments used to measure the constructs making up TPB and Hofstede's (1980) cultural dimensions were considered and thereafter the respondents were clustered into cultural groups. The results of the moderation analysis were then considered.

4.1 Validity and reliability

Initially exploratory factor analysis was conducted (IBM-SPSS: Version 25) in respect of the constructs making up the TPB (Personal attitude, Subjective norms, Perceived behavioural control and Entrepreneurial intention) and the cultural dimensions of Individualism/collectivism, Masculinity/femininity, Power distance, Uncertainty avoidance. The principal axis factoring method was specified as the method of extraction and Promax with Kaiser normalisation was used to allow for inter-correlation between the factors, and the reliability of the constructs was assessed using Cronbach's alpha.

4.2 Measurement

Initially the validity and reliability of the variables making up the TPB (Table 1) are considered and thereafter Hofstede's (1980) cultural dimensions (Table 2).

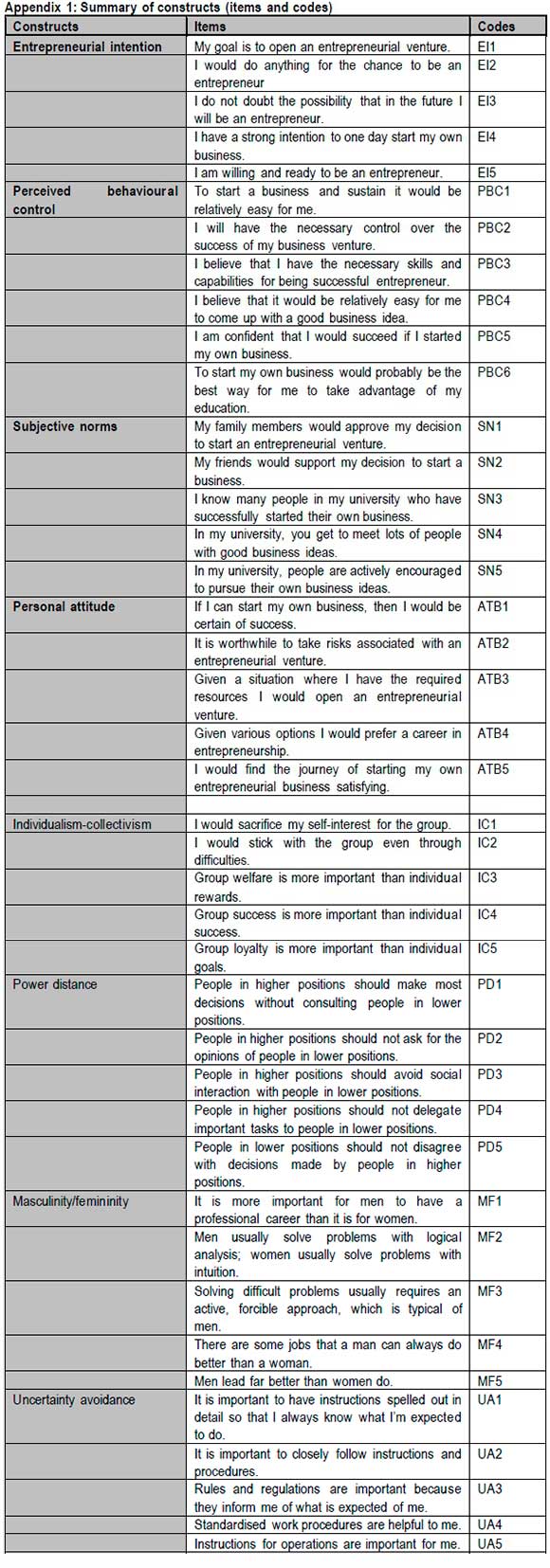

4.2.1 Theory of planned behaviour

Table 1 provides a summary of the measures associated with the assessment of the validity and reliability for the constructs making up the TPB. None of the items hypothesised to measure Perceived behavioural control loaded to any meaningful extent on any of the factors and as such this construct was not included in any further analysis. With regard to the balance of the items (the items associated with the item codes are presented in Appendix 1), the factor loadings were all above 0.8 (with the exception of ATB2, which recorded a score of 0.765), and all of the total Cronbach alpha coefficients were above 0.9 with both the composite reliability (CR) above 0.7. These constructs achieved convergent validity because their average variance extracted (AVE) surpassed the 0.5 level. This implies that the remaining constructs in the TPB were both valid and reliable.

In terms of the operationalisation of the constructs, all were based on the literature, but were adapted to accommodate the sample. Entrepreneurial intention (Mothibi & Malebana, 2019; Sadat & Lin, 2020) for the purposes of this study was defined as the intention to start a business venture or become an entrepreneur. Subjective norms (Bo, 2017; Johara et al., 2017; Mwiya et al., 2017) was operationalised to mean the extent to which peers and university structures actively encourage entrepreneurial behaviour. Personal attitude was operationalised to mean the degree to which an individual is comfortable with taking risks and believes that it will be a feasible and rewarding option to start a successful entrepreneurial venture. This operationalisation implies an element of self-efficacy and largely conforms to the conceptualisation contained in the literature (Alexander & Honig, 2016; Shiri et al., 2017).

Table 2 reflects the items purporting to measure the cultural values, all of which loaded on the factors as expected. There was acceptable validity with all factor loadings above 0.75, with both the CR and AVE yielding values that were greater than 0.7 and 0.5 and all of the Cronbach alpha coefficient totals were above 0.9 which suggest good validity and reliability.

In the current study, Individualism-collectivism was operationalised as the extent to which a person embraces their groups' interest over that of the individual. As such, this scale is regarded as a continuum, with a high score signalling high levels of collectivism and conversely a low score indicating high levels of individualism (Anlesinya et al., 2019; Neira et al., 2017; Nyambegera et al., 2016; Shiri et al., 2017; Valliere, 2017). In the study, Power distance was operationalised to mean the extent to which an individual accepts the idea of power being distributed unequally and that, in business, people in high positions are superior to those in lower positions (Shiri et al., 2017). By contrast, the extent to which men are perceived as better problem solvers and leaders than women and genders having distinct roles in the workplace is how Masculinity/femininity was operationalised in this study (Valliere, 2017). Lastly, Uncertainty avoidance was operationalised in this study to mean the extent to which an individual feels either comfortable (or less comfortable) with ambiguity or uncertainty and their preference for an environment that is characterised by formal structures and rules (Neira et al., 2017).

4.3 Reformulation of the hypotheses

As mentioned above, the construct Perceived behavioural control did not load to any meaningful extent on any factor. Consequently, H3 was no longer relevant and deleted and H4 renamed H3 (and amended) to read:

H3:Membership of a cultural group will moderate the relationship between Entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents (Personal attitude and Subjective norms).

Together with the two sub-hypotheses:

H3.1Membership of a cultural group will moderate the relationship between Personal attitude and Entrepreneurial intention.

H3.2Membership of a cultural group will moderate the relationship between Subjective norms and Entrepreneurial intention.

4.4 Cluster analysis

K-means cluster analysis requires that scores must be standardised to Z values (Lorentz et al., 2016) and the best fitting solution clustered the respondents into three groups. The Z values for the respective dimensions in each group are reflected in Table 3 and these results are reflected graphically in Figure 1.

Group 1, comprising 145 respondents, is characterised by high levels of Power distance compared to other groups. As with all the other cultural dimensions considered in this study, the construct of Individualism/collectivism is a continuum, which means that high scores will reflect high levels of collectivism (and low levels of individualism). As such, Group 1 has high levels of collectivism relative to other groups and is characterised by positive (but moderate) levels of collectivism whereas Group 2 and Group 3 have moderately individualistic values.

A similar pattern is followed with the Masculine/feminine dimension where Group 1 is moderately high compared to Group 2 (comprising 153 respondents). This suggests that the respondents in Group 1 are more accepting of traditional gender roles than the individuals comprising the other two groups. In respect of Power distance there is also a distinct difference between Group 1 and Group 2 with Group 1 exhibiting high positive levels as opposed to Group 2 that has a moderately negative score. Group 3 has moderate and positive levels of this dimension. The differential between Group 1 and Group 2 is the widest in respect of Power distance. This implies that individuals in Group 1 accept that power is distributed unequally and there is a hierarchy in economic roles, which is similar to the views of Group 3.

Group 2 is characterised by high levels of Uncertainty avoidance (Z value = .363) relative to the other groups, with Group 3 having an extremely low level of Uncertainty avoidance (Z value = -1.96) and Group 1 (Z value = .466) having a moderate level. High levels of Uncertainty avoidance have been associated with a need for structure and clarity. This suggests that members of Group 2 prefer structure and direction more than members of the other groups who are more comfortable with ambiguity and a lack of certainty.

4.5 Moderation

The data was tested for violation of the assumptions associated with multiple regression as well as the use of the Hayes process macro (singularity, multicollinearity, normality, linearity and homoscedasticity) and there were no major violations. We then followed the approach of Cohen et al. (2003), and mean-centred the independent variables before utilising the Process macro.

Hayes' (2018) Process macro (version 3.4) automatically codes categorical variables so it was not necessary to manually dummy code the categorical variable (as is usually the case in regression type analyses). However, a reference group approach was still necessary and in this study the moderating influence of membership of Group 1 and Group 2 was done relative to Group 3. This technique also allows the entry of primary independent variable under study as well as any other covariates to consider their relationship with the dependent variable. Accordingly, in this analysis two different models were considered, firstly Personal attitude was entered as the primary independent variable, with Subjective norms as the covariate and thereafter vice versa, with Subjective norms as the primary independent variable and Personal attitude as the covariate. This is consistent with the recommendations of Sadat and Lin (2020) who suggested that it is sometimes useful to probe an interaction twice by changing the roles of the variables.

4.6 Personal attitude

The effect of Personal attitude on the dependent variable was significant with b= 1.138, t(354) = -14.069, p<0.001, in other words, a significant predictor of Entrepreneurial intention. Subjective norms (the covariate) had no significant influence on the dependent variable with b= 0.05, t(354) = 1.56, p>0.05 (0.119) as is reflected in Table 4. Consequently, we can accept hypothesis H1 that Personal attitude will have significant influence on Entrepreneurial intention.

In respect of the main effect of the moderating variables (Cultural groups) we can conclude that membership of Group 1 is not a significant factor in terms of influencing Entrepreneurial intention with the scores for Group 1 recorded as b = 0.254, t(354)= -0.734, p> 0.05 (0.463).

We can therefore conclude that whether or not an individual is a member of either Group 1 or Group 3 will have no significant difference on their respective level of Entrepreneurial intention. Similarly, there is no significant difference between Group 1 and Group 3 with regard to the extent of their Entrepreneurial intention with b= 0.06, t(354) = 0.172, p> 0.05 (0.864).

In respect of the moderating effect of the cultural groups, both the interaction of Group 1 and Group 3 by way of Personal attitude (Interaction - Group 1*Group 3) with scores of b = -0.061, t(354)= 0.670, p> 0.05 (0.503) and Group 2 and Group 3 by way of Personal attitude (Interaction - Group 2*Group 3) with b = 0.03, t(354)= 0.319, p> 0.05 (0.750) and the interaction is not significant. Therefore, we cannot draw the inference that culture has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between Personal attitude and Entrepreneurial intention and therefore cannot accept H3.1 (Membership of a cultural group will moderate the relationship between Personal attitude and Entrepreneurial intention).

4.7 Subjective norms

In this analysis, reflected in Table 5, Subjective norms was entered as the primary independent variable with Personal attitude as the covariate. The results were consistent with the previous results, reflected in Table 4, which reported that the effect of Personal attitude on the dependent variable is significant b= 1.172, t(354)= -36.882, p< 0.001 (0.000). In other words, it is a significant predictor of Entrepreneurial intention, whereas the main effect of Subjective norms (as reflected in Table 5) is not significant with b= -0.106, t(354)= -1.304, p> 0.05 (0.193). This implies that we cannot accept hypothesis H2as the results do not support the hypothesis that Subjective norms will have significant influence on Entrepreneurial intention.

Consistent with the analysis done above (in respect of Personal attitude) with regard to the main effect of the moderating variables (Cultural groups), we can conclude that the main effect of Group 1 is not significant with b = 0.398, t(354)= -1.15, p> 0.05 (0.251). Similarly, the main effect of Group 2 is not significant with b = 0.155, t(354) = 0.451, p> 0.05 (0.652). As such we can conclude that membership of either Group 1 or Group 2 (when compared to Group 3) will not have a significant influence on Entrepreneurial intention.

In respect of the interaction between Group 2 and Group 3 by way of Subjective norms (Interaction - Group 1*Group 3), this relationship is positive and approaching significance does not satisfy the criteria of the p value being below 0.05 with b = 0.169, t(354)= -1.804, p> 0.05 (0.072). However, in respect of the relationship between Group 1 and Group 3 (Interaction -Group 1*Group 3) by way of Subjective norms, the relationship is both significant and positive with b = 0.202, t(354)= -2.15, p< 0.05 (0.032). Therefore we can accept H32: Membership of a cultural group will moderate the relationship between Subjective norms and Entrepreneurial intention.

The main (original) objective of this study, as articulated in Section 1.3.2, was to assess the extent to which culture will moderate the TPB. This was subsequently amended (and renumbered from H4 to H3), when Perceived behaviour control did not load on any factors in the factor analysis. The (amended) hypothesis read as follows: H3: Culture will moderate the Theory of planned behaviour. The two sub-hypotheses (H3.1: Culture will moderate the extent to which Personal attitude influences Entrepreneurial intention and H3.2: Culture will moderate the extent to which Subjective norms influences Entrepreneurial intention), were used to assess the main hypothesis as were the results reflected in Table 5.25 as read with Table 5.23.

It is obvious from the above that it is difficult to appreciate the nature and extent of the moderation effect, based on the arithmetic results alone. Consequently, to visualise the interaction, simple slope graphs were used.

Table 6 reflects the relationship for each group between Subjective norms and Entrepreneurial intention, which is graphed in Figure 5.2. As such, membership of either Group 3, with b = -0.11, t = (354) = -1.30, p > 0.05 (0.19) or Group 2, b = 0.06, t = (354) = 1.34, p > 0.05 (0.18) will not have significant influence on the relationship between Subjective norms and Entrepreneurial intention. In contrast, membership of Group 1, with b = 0.1, t = (354) = 2.03, p < 0.05 (0.04), will have a significant (albeit small) influence on the relationship between Subjective norms and Entrepreneurial intention. This implies that if respondents are a member of Group 1, then Subjective norms predict an increase in Entrepreneurial intention by 0.10 points. So the extent of Subjective norms matters more to members of Group 1 than Group 2 and Group 3 in terms of predicting the formation of an Entrepreneurial intention.

The graphical depiction of the results contained in Table 6 is reflected in Figure 2 above. The slope for Group 1 is steeper than Group 2, which would suggest that a particular increase in Subjective norms will result in a greater increase in Entrepreneurial intention than for the line reflecting the relationship between Personal attitude and Entrepreneurial intention. This supports the argument made above that Subjective norms has a greater influence on Entrepreneurial intention for members of Group 1 than on any of the other two groups.

5. DISCUSSION

The objective of the study was to consider the influence of culture on the intention to become an entrepreneur within the context of the Theory of planned behaviour. However, the study was somewhat constrained when one of the independent variables contained in the model (Perceived behavioural control) did not exhibit adequate levels of validity and reliability and was eliminated. This implied that the study was limited to investigating the moderating effect of culture on the relationship between the remaining independent variables (Personal attitude and Subjective norms) and the dependent variable (Entrepreneurial intention).

In order to overcome obsolete conceptualisations of culture, we used Hofstede's (1980) cultural dimensions along with K-means cluster analysis to understand the structure of the sample's cultural characteristics. Three interpretable groups emerged from this analysis, each with a unique combination of Hofstede's (1980) cultural dimensions. This result offers broad support for our argument that culture is a complex concept in contemporary societies (Darley & Blankson, 2020; Neira et al., 2017; Vershinina et al., 2018) which cannot be adequately analysed using rudimentary units of analysis (such as nations) (de Mooij & Beniflah, 2017; Beugelsdijk & Welzel, 2018; Zhou & Kwon, 2020). As such, our implicit goal to assess the extent to which alternative methodologies might be applicable to appreciate the nature of contemporary culture was achieved.

There was a strong and significant relationship between Personal attitude and Entrepreneurial intention. This finding confirms previous studies which argue that the more positively predisposed that an individual is towards an entrepreneurial career, the more likely it is that they will become an entrepreneur (Roy et al., 2017). This attitude is largely informed by the potential financial benefits and personal satisfaction associated with an entrepreneurial career (Ajzen, 1991; Alexander & Honig, 2016; Kautonen et al., 2015) and confirms the earlier finding in respect of university students by Mwiya et al. (2017). There was, however, no significant interaction effect of culture (conceptualised in this study as membership of a cultural group) on the relationship between Personal attitude and Entrepreneurial intention and as such this study does not offer any support for the argument that social norms may have an indirect influence on this relationship (Liu et al., 2019).

No significant relationship was found between Subjective norms and Entrepreneurial intention and, as such, no conclusions can be drawn about this hypothesised relationship. However, support was offered for the moderating effect that culture might have in respect of the relationship between Subjective norms and Entrepreneurial intention. Specifically for the individuals comprising Group 1, with moderate to high levels of Collectivism, who were more accepting of traditional gender roles, (high levels of Masculine/feminine), who accepted that power is distributed unequally (high levels of Power distance) and who had a preference for standard rules over a laissez-faire approach to business (high levels of Uncertainty avoidance), Subjective norms was an important element in the formation of an Entrepreneurial intention. This implies that for members of Group 1 a particular increase in Subjective norms will result in a greater increase in Entrepreneurial intention than for other groups.

Most of the earlier studies considered the cultural dimensions independently (Bogatyreva et al., 2019; Irene, 2016; Mwiya et al., 2017; Shiri et al., 2017; Valliere, 2017) rather than acknowledging that individuals have diverse levels of the different cultural dimensions (which may offset one another). This makes comparisons difficult (Celikkol et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the high collectivism scores in Group 1 are consistent with the findings in Pecly and Ribeiro (2020) and Iwu et al. (2016) who found that individuals with a collectivist orientation tend to pay more attention to social pressure (Subjective norms) when compared to those individuals who value individualism (Calza et al., 2020; Alexander & Honig, 2016).

This finding could have important implications for how authorities encourage entrepreneurship. Typically the approach has been to educate tertiary students about the rewards associated with starting and growing an enterprise. This approach is certainly supported by the significant positive relationship found between Personal attitude and Entrepreneurial intention. However, the finding that for some members of the student body social norms may be an important factor in the formation of an entrepreneurial intention may suggest a more nuanced approach to encourage university students to become self-employed. Specifically, it is suggested that implementing a programme of mentorship or allowing students to engage with role-models may be effective for students who find the views of others important in making career decisions.

Entrepreneurial activity has largely been associated with cultures that are high in individualism, low in power distance, low in uncertainty avoidance and high in masculinity (Doe et al., 2016; Neira et al., 2017; Valliere, 2017), which is inconsistent with the characteristics found in Group 1. These links between Hofstede's (1980) cultural values and entrepreneurship have largely been mirrored in South Africa where high levels of individualism have been associated with entrepreneurial intention (Mardisetosa et al., 2020; Naqvi & Siddiqui, 2020). There are, however, opposing views that claim that moderate levels of individualism (as opposed to collectivism) will lead to greater levels of entrepreneurial activity (Bogatyreva et al., 2019; Iwu et al., 2016; Vershinina et al., 2018). However, no significant direct relationship was found between membership of the cultural groups and the extent of Entrepreneurial intention so we cannot draw any conclusions in this regard.

6. LIMITATIONS AND CONTRIBUTIONS

The findings of this study do not extend to identifying which combinations of cultural dimensions might have a positive influence on Entrepreneurial intention and this is an area for future research. The study does, however, answer the call to re-examine Hofstede's constructs within the context of contemporary values and behaviour (Ladhari et al., 2015) and the results broadly support the proposal that Hofstede's (1980) dimensions can be adapted to reflect 21st century culture and in so doing overcome the criticism of a lack of dynamism in Hofstede's conceptualisation of culture (Signorini et al., 2009). However, it is conceded that Hofstede's (1980) dimensions are not the only measures of culture and this study should be replicated using other conceptualisations of culture.

In addition, what can be considered a unique contribution of the study is its use of standardised measures for the components of the intention-based model. However, even though the items used in this study had been used in previous studies, the items measuring Perceived behavioural control did not load as expected. This implies that the validity of this scale should be reconsidered in order to improve its validity.

There are, of course, some limitations of the study, the main one being the use of students as the population. In addition, a non-probability sampling technique was used which suggests that the findings of the study cannot be generalised to the whole population of university students in South Africa. Future studies should follow a random sampling approach to allow researchers to make generalisable findings about this important cohort of future entrepreneurs. Another limitation which is worth noting is the assumption, contained in all intention based models, relating to the link between intention and action (Ajzen, 1991; Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018; Kautonen et al., 2015; Najafabadi et al., 2016). Future studies should consider following a longitudinal approach to track the extent to which South African tertiary students who indicate an intention to become an entrepreneur during their university careers actually become self-employed.

REFERENCES

Adekiya, A.A. & Ibrahim, F. 2016. Entrepreneurship intention among students. The antecedent role of culture and entrepreneurship training and development. International Journal of Management Education, 14(2):116-132. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2016.03.001]. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. 1985. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior. Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 11-39. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-64269746-32]. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. 1991. The Theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50:179-211. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T]. [ Links ]

Al-Alawi, A.I. & Alkhodari, H.J. 2016. Cross-cultural differences in managing businesses: Applying Hofstede's cultural analysis in Germany, Canada, South Korea and Morocco. International Business Management, 95: 40855-40861. [ Links ]

Alexander, I.K. & Honig, B. 2016. Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Cultural Perspective. Africa Journal of Management, 2(3):235-257. [https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2016.1206801 ]. [ Links ]

Ali, M.S.Y. & Abou, E.A.E. 2020. Determinants of entrepreneurial intention among Sudanese university students. Management Science Letters, 10:2849-2860. [https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.4.023]. [ Links ]

Anlesinya, A., Adepoju, O.A. & Richter, U.H. 2019. Cultural orientation, perceived support and participation of female students in formal entrepreneurship in the sub-Saharan economy of Ghana. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 11(3):299-322. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-01-2019-0018]. [ Links ]

Barba-Sánchez, V. & Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. 2018. Entrepreneurial intention among engineering students: The role of entrepreneurship education. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 24(1):53-61. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2017.04.001 ]. [ Links ]

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6): 1173-1182. [https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173]. [ Links ]

Beugelsdijk, S., Kostova, T. & Roth, K. 2017. An overview of Hofstede-inspired country-level culture research in international business since 2006. Journal of International Business Studies, 48:30-47. [https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-016-0038-8]. [ Links ]

Beugelsdijk, S. & Welzel, C. 2018. Dimensions and dynamics of national culture: Synthesizing Hofstede with Inglehart. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(10):1469-1505. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118798505]. [ Links ]

Bo, Z. 2017. Research on cultivation scheme based on TPB of entrepreneurial talents in Chinese local application-oriented universities. Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 13(8):5629-5636. [https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.01016a]. [ Links ]

Bogatyreva, K., Edelman, L.F., Manolova, T.S., Osiyevskyy, O. & Shirokova, G. 2019. When do entrepreneurial intentions lead to actions? The role of national culture. Journal of Business Research, 96:309-321. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.034]. [ Links ]

Botha, M. & Bignotti, A. 2017. Exploring moderators in the relationship between cognitive adaptability and entrepreneurial intention: Findings from South Africa. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13:1069-1095. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0437-8]. [ Links ]

Cameron Cockrell, R. & Stone, D.N. 2010. Industry culture influences pseudo-knowledge sharing: a multiple mediation analysis. Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(6):841-857. [https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271011084899]. [ Links ]

Canestrino, R., Cwiklicki, M., Magliocca, P. & Pawelek, B. 2020. Understanding social entrepreneurship: A cultural perspective in business research. Journal of Business Research, 110:132-143. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.006]. [ Links ]

Calza, F., Cannavale, C. & Nadali, I.Z. 2020. How do cultural values influence entrepreneurial behavior of nations? A behavioral reasoning approach. International Business Review, 29 (5). [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101725]. [ Links ]

Celikkolm, M., Kitapgi, H. & Doven. G. 2019. Culture's impact on entrepreneurship and interaction effect of economic development level: An 81-country study. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 20:777-797. [Doi: 10.3846/jbem.2019.10180]. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2019.10180]. [ Links ]

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S.G. & Aiken, L.S. 2003. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for behavioural sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ:Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Covin, J.G., Rigtering, J.C., Hughes, M., Kraus, S., Cheng, C.F., & Bouncken, R.B. 2020. Individual and team entrepreneurial orientation: Scale development and configurations for success. Journal of Business Research, 112:1-12. [ Links ]

Darley, W.K. & Blankson. C. 2020. Sub-saharan African cultural belief system and entrepreneurial activities: A Ghanaian perspective. Africa Journal of Management, 6(2):67-84. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2020.1753485]. [ Links ]

Debarliev, S., Janeska-Iliev, A., Bozhinovska, T. & Ilieva, V. 2015. Antecedents of entrepreneurial intention: Evidence from Republic of Macedonia. Business and Economic Horizons, 11(3):143-161. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2015.11]. [ Links ]

de Mooij, M. & Beniflah, J. 2017. Measuring cross-cultural differences of ethnic groups within nations: Convergence or divergence of cultural values? The Case of the United States. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 29(1):2-10. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2016.1227758]. [ Links ]

Doe, F., Arkorful, H.K. & Agyemang, C.B. 2016. Culture, societal expectation and entrepreneurial intentions: A study among small and medium scale operators in Ghana. Research Journal of Economics & Business Studies, 5(5):41-51. [ Links ]

Douglas, M. 1973. Natural symbols: Explorations in cosmology. London: Barrie & Rockliff: [ Links ]

Ebewo. P.E., Shambare, R. & Rugimbana, R. 2017. Entrepreneurial intentions of Tshwane University of Technology, arts and design students. African Journal of Business Management, 11(9):175-182. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM2017.8253]. [ Links ]

Eringa, K., Caudron. L.N., Rieck, K., Xie, F. & Gerharbt, T. 2015. How relevant are Hofstede's dimensions for inter-cultural studies? A replication of Hofstede's research among current international business students. Research in Hospitality Management, 5(2):187-198. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/22243534.2015.11828344]. [ Links ]

Fatoki, O. 2019. Sustainability orientation and sustainable entrepreneurial intentions of university students in South Africa. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 7(2):990-999. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2019.7.2(14)]. [ Links ]

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Pennsylvania: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Ferreira, J.J., Fernandes, C.I., & Kraus, S. 2019. Entrepreneurship research: mapping intellectual structures and research trends. Review of Managerial Science, 13(1):181-205. [ Links ]

García-Cabrera, A.M. & García-Soto, G. 2017. Cultural differences and entrepreneurial behaviour: An i ntra-country cross-cultural analysis in Cape Verde. Entrepreneurial & Regional Development, 20(5):451-483. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620801912608]. [ Links ]

Hall, E.T. 1990. Understanding cultural differences. Yarmouth: Intercultural Press: [ Links ]

Hayes, A.F. 2009. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4):408-420. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360]. [ Links ]

Hayes, A.F. 2018. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs. 85:1:4-40. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100]. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. 1980. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Beverly Hills:Sage. [ Links ]

Irene, B.N.O. 2016. Women entrepreneurs: A cross-cultural study of the impact of the commitment competency on the success of female-owned SMMEs in South Africa. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research, 27(2):70-83. [ Links ]

Iwu, C.G., Ezeuduji I.O., Eresia-Eke, C. & Tengeh, R. 2016. The entrepreneurial intention of university students: The case of a University of Technology in South Africa. Acta Universitatis Danubius: OEconomica, 12(1):164-181. [ Links ]

Johara, F., Yahya, S.B. & Tehseen, S. 2017. Determinants of future entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intention. Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal, 9(4):80-95. [ Links ]

Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M. & Fink. M. 2015. Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 39(3):655-674. [https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12056]. [ Links ]

Kim-Soon, N., Ahmad, A.R. & Ibrahim, N.N. 2016. Theory of planned behavior: Entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurship career intention at a public university. Journal of Entrepreneurship: Research & Practice:1-14. [ Links ]

Kluckhohn, F.R. & Strodtbeck F.L. 1961. Variations in value orientations. New York: Row, Peterson and Company. [ Links ]

Ladhari, R., Souiden, N. & ChoI Y.H. 2015. Culture change and globalization: The unresolved debate between cross-national and cross-cultural classifications. Australasian Marketing Journal , 23(3):235-245. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2015.06.003]. [ Links ]

Laskovaia, A., Shirokova, G. & Morris, M.H. 2017. National culture, effectuation, and new venture performance: Global evidence from student entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics. Small Business Economics, 49(3):687-709. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9852-z]. [ Links ]

Lee, B. & Kelly, L. 2019. Cultural leadership ideals and social entrepreneurship: An international study. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 10(1):108-128. [https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1541005]. [ Links ]

Littlewood, D. & Holt, D. 2018. Social entrepreneurship in South Africa: Exploring the influence of environment. Business & Society, 57(3):525-561. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650315613293]. [ Links ]

Litzky, B., Winkel, D., Hance, J. & Howell, R. 2020. Entrepreneurial intentions: personal and cultural variations. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 27(7):1029-1047. [ https://doi.org/10.1108/JS BED-07-2019-0241]. [ Links ]

Liu, J., Pacho F,T. & Xuhui, W. 2018. The influence of culture in entrepreneurs' opportunity exploitation decision in Tanzania. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 11(1). [https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-02-2017-0014]. [ Links ]

Liu, X., Lin, C., Zhao, G. & Zhao, D. 2019. Research on the effects of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on collage students' entrepreneruial intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10:1-9. [https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00869]. [ Links ]

Lorentz, H., Hilmola, O.P., Malmsten, J. & Sri, J.S. 2016. Cluster analysis application for understanding SME manufacturing strategies. Expert Systems with Applications, 66:176-188. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2016.09.016]. [ Links ]

Lounsbury, M., Cornelissen, J., Granqvist, N. & Grodal, S. 2019. Culture, innovation and entrepreneurship. Innovation: Organization & Management, 21(1):1-12. [https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2018.1537716]. [ Links ]

Malebana, M.J. & Swanepoel, E. 2015. Gender differences in entrepreneurial intention in the rural provinces of South Africa. Journal of Contemporary Management, 12(1):615-637. [https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2016.1259990]. [ Links ]

Mardisetosa. B., Khusaini, K. & Gumelar, W.A. 2020. Personality, gender, culture and entrepreneurial intentions of undergraduate student: Binary logistic regression. Jurnal Pendidikan Ekonomi & Bisnis, 8(2):127-142. [https://doi.org/10.21009/JPEB.008.2.5]. [ Links ]

Mazanec, J.A., Crotts, J., Gursoy, D. & Lu, L. 2015. Homogeneity versus heterogeneity of cultural values : An item-response theoretical approach applying Hofstede' s cultural dimensions in a single nation. Tourism Management, 48(C):299-304. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.11.011]. [ Links ]

McClelland, D.C. 1961 The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand. [ Links ]

Meyer N. 2018. South African female entrepreneurs' intention to remain in business. (Doctoral thesis). Potchefstroom, South Africa: North-West University. [ Links ]

Meyer, D.F. & Meyer, N. 2020. The relationships between entrepreneurial factors and economic growth and development: The case of selected European countries. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 21(2):268-284. [https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2020.21.2.19]. [ Links ]

Mothibi, M.H. & Malebana, M.J. 2019. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners in Mamelodi, South Africa. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 25(2):1-14. [ Links ]

Mutiara, M.R., Primiana, I., Joeliaty, J. & Cahyandito, M.F. 2019. Exploring cultural orientation on the entrepreneur competencies in the globalization era. Business: Theory and Practice, 20:379-390. [https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2019.36]. [ Links ]

Mwiya. B., Wang. Y., Shikaputo, C., Kaulungombe, B. & Kayekesi, M. 2017. Predicting the entrepreneurial intentions of university students: Applying the theory of planned behaviour in Zambia, Africa. Open Journal of Business and Management, 5:592-610. [https://doi.org/10.4236/oJbm.2017.54051]. [ Links ]

NajafabadI, M.O., Zamani, M. & Mirdamadi, M. 2016. Designing a model for entrepreneurial intentions of agricultural students. Journal of Education for Business, 91(6):338-346. [https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2016.1218318]. [ Links ]

Naqvi, S.D.H. & Siddiqui, D.A. 2020. Personal entrepreneurial attributes and intentions to start business: The moderating role of culture. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 10(1):33-69. [https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v10i1.15817]. [ Links ]

Ndofirepi, T.M. & Rambe, P. 2018. A qualitative approach to the entrepreneurial education and intentions nexus: A case of Zimbabwean polytechnic students. Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 10(1):1-14. [https://doi.org/10.4102/sajesbm.v10i1.81]. [ Links ]

Neira, I., Calvo, N. & Portela, M. 2017. Entrepreneur: Do social capital and culture matter? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13:665-683. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0418-3]. [ Links ]

Neneh, B.N. 2020. Entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention: The role of social support and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Studies in Higher Education. [https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1770716]. [ Links ]

Nyambegera, S.M, Kamoche, K. & Siebers, L. 2016. Integrating Chinese and African culture into human resource management practise to enhence employee job satisfaction. Journal of Language, Technology & Entrepreneurship in Africa, 7(2):118-139. [ Links ]

Palmer, C., Niemand, T., Stöckmann, C., Kraus, S., & Kailer, N. 2019. The interplay of entrepreneurial orientation and psychological traits in explaining firm performance. Journal of Business Research, 94:183-194. [ Links ]

Palmer, C., Fasbender, U., Kraus, S., Birkner, S., & Kailer, N. 2021. A chip off the old block? The role of dominance and parental entrepreneurship for entrepreneurial intention. Review of Managerial Science, 15(2):287-307. [ Links ]

Pecly, P.H.D. & Ribeiro, P.C.C. 2020. Entrepreneurship in the BRICS and cultural dimensions. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, 17(2):1-18. [https://doi.org/10.14488/BJOPM.2020.013]. [ Links ]

Richter, N.F., Hauff, S., Schlaegel, C., Gudergan, S., Ringle, C.M. & Gunkel, M. 2016. Using cultural archetypes in cross-cultural management studies. Journal of International Management, 22(1):63-83. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2015.09.001]. [ Links ]

Roy, R., Akhtar, F. & Das, N. 2017. Entrepreneurial intention among science & technology students in India: Extending the theory of planned behavior. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(4):1013-1041. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0434-y]. [ Links ]

Sadat, A.M. & Lin, M.L. 2020. Examining the student entrepreneurship intention using TPB approach with gender as moderation variable. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 13(6):193-207. [ Links ]

Schumpeter, J.A. 1934. The theory of economic development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S.H. 1992. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and emperical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25:1-65. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-260K08)60281-6]. [ Links ]

Shah, I.A., Amjed, S. & Jaboob, S. (2020). The moderating role of entrepreneurship education in shaping entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Economic Structures, 9(19):1-15. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-020-00195-4]. [ Links ]

Shiri, N., Shinnar, R.S., Mirakzadeh A.A., & Zarafshani, K. 2017. Cultural values and entrepreneurial intentions among agriculture students in Iran. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(2):1-23. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s 11365-017-0444-9]. [ Links ]

Signorini, P., Wiesmes, R. & Murphy, R. 2009. Developing alternative framework for exploring intercultural learning: A critique of Hoftede's cultural differences model. Teaching in Higher Education, 14(3):253-264. [https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510902898825]. [ Links ]

Sobel, M.E. 1982. Asymptotic confidence interval for indirect effects in structural equation models, in S. Leinhardt (ed.). Sociological methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Associatiation, pp. 290-312. [https://doi.org/10.2307/270723]. [ Links ]

Stephan, U. & Pathak, S. 2016. Beyond cultural values? Cultural leadership ideals and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(5):505-523. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.07.003]. [ Links ]

Straub, P., Greven, A. & Brettel, M. 2020. Determining the influence of national culture: Insight into entrepreneurs' collective identity and effectuation. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(12). [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00645-2]. [ Links ]

Strydom, C., Meyer, N. & Synodinos, C. 2021. South African generation y students' intention toward ecopreneurship. Acta Commercii, 21(1):1-12. [https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v21i1.910]. [ Links ]

Trevifio, L.C. 2020. Culture and university entrepreneurship. Journal of Evolutionary Studies in Business. 5(1):265-283. [https://doi.org/10.1344/jesb2020.1.j074]. [ Links ]

Trompenaars, F. & Hampden-Turner, C. 1997. Riding the waves of culture. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Urban, B. & Ratsimanetrimanana F.A. 2015. Culture and entrepreneurial intentions of Madagascan ethnic groups. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 7(2):86-114. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-01-2015-0008]. [ Links ]

Valliere, D. 2017. Belief patterns of entrepreneurship: Exploring cross-cultural logics. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(2):245-266. [https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2015-02971. [ Links ]

Vershinina, N., Woldesenbet, B.K. & Murithi, W. 2018. How does national culture enable or constrain entrepreneurship? Exploring the role of Harambee in Kenya. Journal of Small Businesses and Enterprise Development, 25(4):687-704. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-03-2017-0143]. [ Links ]

Williams, I.K. & McGuire, S.J. 2010. Economic creativity and innovation implimentation: The entreprepreneurial drivers of growth? Evidence from 63 countries. Small Business Economics, 34(4):391-412. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9145-7]. [ Links ]

Yunis, M., El-Kassar, A.-N. & Tarhini, A. 2017. Impact of ICT-based innovations on organizational performance: The role of corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 30(1):122-141. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-01-2016-0040]. [ Links ]

Zhang, Z., Zyphur, M.J., Narayanan, J., Arvey, R.D., Chaturvedi, S., Avolio, B.J., Lichtenstein, P. and Larsson, G. 2009. The genetic basis of entrepreneurship: Effects of gender and personality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 110(2): 93-107. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.07.002]. [ Links ]

Zhou, Y. & Kwon, J.W. 2020. Overview of Hofstede-inspired research over the past 40 years: The network diversity perspective. SAGE Open: 1-17. [https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020947425]. [ Links ]

Zhu F., Hsu, D.K., Burmeister-Lamp, K. & Fan, S.X. 2018. An investigation of entrepreneurs' venture persistence decision: The contingency effect of psychological ownership and adversity. Applied Psychology, 67(1):136-170. [https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12106]. [ Links ]

* corresponding author