Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.18 no.2 Meyerton 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcm20125.123

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Government's impact on the venture capital market and small-medium enterprises' survival and growth in East Africa, evidence from Uganda

Ahmed I. KatoI, *; Chiloane Evelyn GerminahII

IDepartment of Applied Management, University of South Africa, South Africa. Email: ahmedkato2@gmail.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1811-6138

IIDepartment of Applied Management, University of South Africa, South Africa Email: chilooge@.unisa.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0460-6291,

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: In recent years, the government's involvement in the venture capital (VC) market has been hailed for encouraging the survival and growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) primarily in developed economies. In this paper, the impact of the government's involvement in the VC market on the survival and growth of startup entrepreneurial firms in Uganda is explored

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: A mixed-method research design to hand-collect primary data from 90 VC experts was employed. The quantitative data were evaluated using a multiple regression model and other inferential tests; the results were generated using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS

FINDINGS: This paper discloses that 63 percent of the respondents confirmed the positive impact of government's involvement in enhancing the development of early-stage firms. Considering these results, the higher percentage suggests commendable success and the growth of enterprises. This study confirms that VC financing is a precursor for the quicker growth of early-stage enterprises. The paper further discloses that Uganda's VC market is underdeveloped and without clear VC policies

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: Drawing from our findings and earlier literature works, Uganda's VC policies are still in the design stage and not well regulated when compared to Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. These countries established defined PE and VC association which provide insights in the VC market. As a result, emerging economies including Uganda ought to replicate US government VC funding model to upsurge VC investment supply into the region thereby bridging the equity financing gap which inhibits SMEs' survival and growth especially in the developing countries

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The government lacks defined tracking of VC deals and cannot offer legal support to the VC fundraising drive. On this basis, the Uganda government should make a deliberate effort to create a supportive policy to inspire foreign VC investors into the country who are experienced in nurturing SMEs growth until maturity stage

JEL CLASSIFICATION: G2: G22:28

Keywords: Government venture capital; VC co-investment; VC fund managers; Venture capital and SMEs' growth; Uganda.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, the global Venture Capital (VC) market has recognised the escalating interest of policymakers and practitioners in emerging economies. Contemporary literature reveals that in 2019 Africa reported an aggregated VC investment of US$1.34 billion matched to US$725.6 million VC funds raised in 2018 (WeeTracker, 2021). However, the annual VC investment in 2020 decreased profoundly (43%) to US$757.29 million when compared to the previous year. This was attributable to the acute impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on key investing economies (WeeTracker, 2021). Furthermore, a quick analysis of the VC markets of European Union (EU) countries reveals that from 2007 to 2019 EU governmental agencies provided €16.4 billion of VC funds to EU countries (Invest Europe, 2020; Kallay & Jaki 2020). Nonetheless, little is known about government VC funding in African countries because the contributions of their regimes to the VC industry in Africa is minimal (Deventer & Mlambo, 2008; Deloitte & SAVCA, 2009; Agyeman, 2010; Shanthi et al., 2018: Mboto et al., 2018; Kato & Tsoka, 2020; Maurizio, 2020). This paper, therefore, attempts to discover why Africa's VC market has been under-exploited; evidence from Uganda is utilised to facilitate this discovery. Despite the pitfalls observed in the VC industry in Africa, topical literature underwrites VC as the primary funding instrument for early-stage entrepreneurial firms (Baldock, 2016; Biney, 2018; Rosa et al., 2019; Thies et al., 2019; Kato & Tsoka, 2020; Gompers et al., 2020; Lerner & Nanda, 2020; Gaies et al., 2021). Besides, scholars disclose that the surpassing growth of the United States (US) VC markets can be squarely attributed to far-reaching government patronage provided directly by government VC funding (GVCF) and the enactment of supportive regulatory reforms (Gompers & Lerner, 2001; Lerner 2010; Deloitte & NVCA, Owen et al., 2019; Lerner, 2020: Gompers et al., 2020; NVCA, 2020). The aforementioned analogy can be reinforced by the success and tremendous growth of well-known techno-companies in the US such as Apple, Microsoft, Google, Netscape and Compaq, all of which had roots in VC financing in their early stages (Gompers & Lerner, 2001; Deloitte & NVCA, 2009; Owen & Mason, 2019; Jihye et al., 2020). Consequently, numerous countries have embarked on government VC policy reform to mitigate the finance gap for startup entrepreneurial ventures deprived of private venture capital (PVC) financing (Murray, 2007; Lerner, 2010; Lingelbach, 2015; Baldock, 2016; Owen & Mason, 2017; European Commission, 2017; Kallmuenzer et al., 2021).

While several developing countries are recognised for undertaking policy reforms to stimulate VC market development, occasionally they are unclear about the intervening policy approaches to implement (Lerner et al., 2016; KPMG & EAVCA, 2019). VC is a high-risk equity capital in the form of seed, startup and expansion financing and invested in companies that have already demonstrated business potential but that are not listed on public securities markets or are too underprivileged to access traditional funding sources (Gompers & Lerner, 1999; Chemmanur et al., 2014; Lerner, 2010; Kato & Tsoka, 2020). As such, increasing input from co-investment funds (CIFs) into PVC firms may offer benefits to fix the equity gap, especially in countries with VC scarcities (Baldock & Mason, 2015; Colombo et al., 2016; Kato & Germinah, 2020).

Lerner (2010) divulges the notable achievements of government regulatory policy in the VC industry; these remarkably included the Yozma Fund of Israel in 1992, New Zealand Venture Capital in 2002 and US Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) in 1980. Undoubtedly, these funding models unveil the momentous global best practices of government-sponsored VC funding (GSVCFs) as an escalator for economic development in developed economies (Owen et al., 2019).

In Uganda, which is the focus of this research, a handful of government programmes and policy reforms were established between 2015 and 2016 for easy access to VC financing by early-stage entrepreneurial firms. These involved the inauguration of annual VC international conferences, a one-stopover business centre and tax incentives to attract foreign VC investment (Uganda Investment Authority, 2016; Kato & Tsoka, 2020). Baldock (2016), Gompers et al. (2020) and Lerner, (2020) also noted that the significant increase of government VC-backed companies is clear evidence of the government's commitment to flourish VC markets. On the other hand, existing empirical research in Uganda holds limited evidence to underscore the success of government regulatory policy in encouraging VC market development when compared to countries like Singapore, Israel, New Zealand and Brazil. This study is supported by the current literature on the US GVCF model (Chemmanur et al., 2014; NVCA, 2020) and some of the best practices which demonstrated the success of government involvement in VC markets from Israel, New Zealand and China (Lerner & Nanda, 2020).

Whereas several emerging economies have made deliberate efforts to implement regulatory policy reform as a measure to nurture the growth of the VC industry and avert the financing gap of startups, appropriate GVCF for portfolio companies remains a big problem (Cumming et al., 2017; Grilli & Murtinu, 2014; Baldock & Mason, 2015; Bertoni & Tykvova, 2015; Callagher et al., 2015; Gu & Qian, 2019; Richard et al., 2019; Maurizio, 2020). On the other hand, Cumming and Johan (2016) and Lerner et al. (2016) uncover that both direct and indirect government policies have been observed to be unsuccessful and an obstacle to the growth of startup firms. It can be concluded that previous studies supporting the government's role in enhancing VC market growth in developing nations are not convincing and that the need for future empirical research is irrefutable.

As a result, this paper offers novel knowledge on the under-explored research on the government's role in nurturing the VC market and the survival and growth of SMEs in emerging nations like Uganda. Some of the best practices from a global perspective are further highlighted and existing gaps in the current literature are disclosed to assist policymakers and practitioners in designing appropriate policies that inspire the growth of the VC ecosystem. The remaining part of this paper is structured as follows: a literature review, research methodology, findings and discussions and conclusions and recommendations. The paper also identifies and summarises gaps in the literature and considers their implications for future policy

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Theoretical foundation

This paper reflects on the Institutional theory that entails a broad continuum of entrepreneurship literature, embracing formal and informal concepts. The formal concept involves the national legal framework and financial regulation while the informal model considers culture, professionalism, code of conduct and the commercial environment in which a firm operates (Scott, 1995). The major goal of institutional theory is to provide a blueprint that can guide external institutions to a firm by enforcing desirable principles and applicable behaviour within certain socially assembled norms, values and beliefs (Scott, 1995). This theoretical review is confined to the formal concept that involves the government's direct and indirect interventions in the VC landscape. In this paper, the government's direct involvement is denoted as 'government venture capital funding' (GVCF) whereas the indirect method is represented as 'government regulatory regulations' (Lerner, 2010; Baldock & North, 2015). Earlier scholars suggest that institutional theory offers direction to government legislative provision and standardised contracts intended to govern the growth of the business sector (Owen et al., 2019; Kato & Tsoka, 2020).

Topical studies suggest that the indirect approach primarily concentrates on government involvement in forming supportive regulatory frameworks where VC can flourish (Murray, 2007; Lerner, 2010; Baldock & North, 2015). By echoing the practical implications of institutional theory in directing the implementation of government regulatory policy to uphold VC, market development was envisioned.

The direct method is discussed from two standpoints: the supply side denoted as 'VC financing' and the demand side represented as 'portfolio companies with growth potential'. The government direct model is typically designed and implemented to mitigate the SMEs' equity financing gap and propel VC market development (Lerner, 2010). Several scholars have used this approach, to debate the practical implications of institutional theory, expounding on the interrelations between GVCF and PVC in escalating VC market development (Gompers & Lerner, 2001; Lerner, 2010; Baldock, 2016).

This study's review of the model is supported by Lerner's (2010) principles that advocate for upscaling the VC industry by augmenting it with GVCF. Besides, previous scholars argue that VC contracts are 'pigeon-holed' with moral hazards developing from a conflict of interest between the venture capitalists (VCs) and portfolio companies (Bruton et al., 2009; Callagher et al., 2015). For this reason, the presence of a conducive legal environment is vital to minimise any disagreement in executing signed VC contracts since enhanced legal systems entail more weight and offer investors protection from any cash flow shortcomings.

The demand side concept is associated with the entrepreneurial ecosystem which demands a sufficient number of early-stage firms with growth potential ready to absorb VC financing at an early and expansion level. Cumming et al. (2017) noted that there must be a point of equilibrium between the demand and supply of VC, otherwise GVC-funded companies are usually unsuccessful. On the contrary, some authors criticise institutional theory for its lack of capacity to fill the financing gap of SMEs with growth potential. They claim that GVC-backed firms are unlikely to be successful because they are managed by less experienced fund managers with laughable controls within the GVC-backed firms (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 1995).

In conclusion, institutional theory offers grounds for a review of existing literature underscoring the practical implications of government regulation in enhancing VC market development.

Government intervention in VC markets determines the direction of the VC industry, provided the regulatory framework is well managed. However, the theory suffers from a weakness; it assumes a situation where there is a pool of PVC to complement and boost CIF to bridge the equity gaps, but this is not always the case.

2.2 Overview of empirical studies

The exploration of empirical studies connected to the research is alienated in two divisions underpinning government's role in enhancing VC market development. First, the government's indirect approach to VC market development, indicating lessons learned and existing gaps, is discussed. Secondly, the government's direct approach to VC market development focusing on CIFs is covered.

2.2.1 Government's indirect approach to venture capital market development

In this section, the government's indirect approach to encourage the growth of the VC market through the design of a supportive regulatory policy framework is discussed. Regulations are policies and procedures implemented by the government and backed up by virtual hazards or consequences in the form of penalties repeatedly directed to business enterprises (OECD, 2012).

According to Gompers and Lerner (1999) and Metrick and Yasuda (2010), the development of the VC industry normally requires a legal framework that safeguards the interests of business entrepreneurs and VCs, as well as a government agenda to accommodate the investment uncertainties and information asymmetry to reduce transaction costs that are integral in startups. In this discussion, the best practices of government regulatory policy in encouraging VC market development with evidence-based models as well as lessons learned are brought to light.

Cumming and Atiqah (2009) studied a pre-seed fund (PSF) programme recognised by the Australian government in 2002. It was a joint partnership for pooled funding from GSVCF and PVC and steered by the state to fill the equity gap and nurture the growth of high-tech entrepreneurial companies in Australia. The study found no evidence in support of government regulations; rather, it discovered that the PSF programme caused the crowding out of PVC dealings. Moreover, out of the four PSF programmes, only one outstripped; the other three were fraught. The findings from the study of (Gompers et al., 2009; Brander et al., 2010) and Colombo et al., 2016) confirm the earlier research as they claim both direct and indirect government policies have been found unsuccessful and an obstacle to the growth of startup firms.

In Iran, Shojaei et al., (2018) examined the effect of institutional policy on VC market development. He found a positive impact from direct government involvement in the VC industry in terms of growth, on condition that the government investors were not leading partners in a VC syndicate. These results were consistent with Yongqiang (2014) who investigated the impact of government regulations in connection with the financial performance of 387 SMEs in Australia. This study engaged a comprehensive set of government policies and explored how they influenced the financial performance of small firms. The findings showed that government regulatory frameworks, measured by the present works, had a positive impact on the growth of VC markets.

Besides, this author confers that this model contests a single government reform approach and recommended aggregated policy amendments to address any gaps in the VC industry. Therefore, government's involvement in the VC industry is essential especially in increasing CIFs in the private VC firms and creating a supportive investment environment in the developing countries like Uganda.

Similarly, Adongo (2012) investigated 645 private equity firms from 50 African countries from 2002 to 2010 to establish how the environmental legal framework impacts on VC and private equity (PE) backed firms. The results uncovered that if government policies are well planned and executed, they may assist to enhance early-stage VC financing. This author further observed that early-stage firms recorded dwindling financing in their last stage of business expansion. However, Owen and Mason (2017) uncovered that stand-alone GVCF in isolation of PVC financing may not kindle innovation and progress in the VC industry. Few studies of this nature have been conducted about government regulatory policy and VC market development in Africa.

From a different standpoint, Brander et al. (2015) alluded to the fact that GVCF is only important for VC-backed companies that have reached the maturity stage to exit and as long as the PVC firms are ready to syndicate and offer a large percentage of the deal. Although some scholars have offered evidence accentuating the benefits of government regulations in boosting VC markets (Lerner, 2010; Baldock & North, 2015; Tykvova, 2017; Kato & Tsoka, 2020; Jihye et al., 2020), other researchers have reached conflicting conclusions (Kallay & Jika, 2020). This paper aims to deliver insight into how government regulatory policy impacts the development of VC markets in emerging economies and is centred on Uganda as the case study.

2.2.2 Government's direct involvement in venture capital markets development

In this section, topical literature is discussed and analysed. Examples of what has worked well in developed economies are accentuated and supported with empirical evidence, existing gaps are disclosed and a suggestion for future research is offered.

Baldock (2016) examined the effectiveness of GSVCF in the United Kingdom. The impact thereof was measured in terms of its sustainability, economic freedom and crowding out. The findings disclosed the positive impact of GVCF on the growth of the VC-backed companies in terms of growth, turnover, employment creation and bridging funding gaps for early-stage firms. However, the author noted that inadequate follow-up of GVC-funded companies was the reason for the failure of GVC programmes. Conversely, Cumming and Johan (2009) confirmed that GVC-funded firms perform poorly in terms of getting them up to the level of initial public offerings (IPOs).

In a similar argument, the studies of Cumming et al. (2017) and Munari and Toschi (2015) disclosed the increased failure of government-led funded companies, emanating from being controlled by inexperienced government investors and companies not able to yield the expected return on equity (ROE). Furthermore, Bertoni and Tykvova (2015) exposed that "VCs are more interested in their fund performance than their portfolio companies". They might be hesitant to embrace CIFs because of the fear of weakening their equity investment with GSVCF which may compel them to grandstand the SMEs prematurely to recover ROE early and exit. Most of the studies on GVCF were done in developed economies and future research in the emerging economies of Africa, in particular, would contribute new knowledge to the extant literature.

Cumming and Macintosh (2006) and Murray et al. (2012) concluded that GVCF is manifested with a conflict of interest that may hamper the evolution of early startup firms due to the rivalry amongst GVC fund managers and PVC companies funding parallel corporate sectors. Subsequently, this activity culminates into GVCF' crowding out' existing PVC undertakings. The Canadian PVC market fell victim to crowding out ignited by GVCF which accordingly hampered its outward growth (Brander et al., 2009). As a result, it is judicious that GVC-backed companies syndicate to have access to all funding rounds and to allow them to proceed to the final stage of IPOs.

However, Baldock and Mason (2015) disclosed that the success of any GSVCF programmes is dependent on the selection of private fund managers and specific national policies. On the contrary, Murray et al. (2012) disclosed that GVCF cannot support companies up to exit level due to unsatisfactory funding limitations on deals. The mixed extrapolations from the different authors are the motivation for this study which seeks to shed more light on the current trend of VC market development in Uganda.

Kallay and Jika (2020) investigated the impact of state intervention on the quality of VC portfolios in Hungary. They discovered that the portfolio companies do not demonstrate a substantial increase in total business worth and declined in the later years of the programme as public funding was enlarged. From this, it can be inferred that the size and superiority of the VC market regulates the proficient capacity and nature of government intervention

Matisone and Natalja (2020) uncovered that government intervention was found to enhance the growth of the self-sustainable VC market in Latvia. Evidence showed that 294 VC investments were publicly supported by hybrid VC funds. Nevertheless, Latvian VC fund managers were not yet capable of raising private funds and encountered difficulties in attracting the necessary level of private capital for publicly supported hybrid VC funds. This confirms the conclusions of Baldock and North, (2015) who argued that public policies aimed at creating healthy and supporting conditions for VC activity are necessary in addition to public financial support for VC funds.

While Cumming and Macintosh (2006) provided their outcry about conflict of interest hampering the evolution of an early startup, Bertoni and Tykvova (2015) and Cumming et al. (2017) observed that GVCF did not encourage innovation and sales turnover tends to decrease with government presence in VC markets. They further uncovered that GVCF is often characterised by the bureaucratic controls of funded companies with less experienced fund managers and poor performing portfolio companies matched with PVC-backed firms. Nevertheless, GVC concepts ignore that VC firms maintain large budgets of pooled funds from their international development partners, investment clubs and universities, to mention a few. Thus, less interest may be exhibited in GVCF.

Interestingly, the study of Owen and Mason (2017) presents appealing results, emphasising that the GVCF approach became obsolete a couple of years ago and was replaced by hybrid GVC that involves government CIFs alongside PVC firms. These results confirm that GVCF may not yield good results unless VC firms agree to CIFs to spur the growth of early-stage firms.

In summary, numerous countries have accepted the GVCF paradigm to stimulate VC market development and SMEs survival and growth as a measure to create job opportunities and economic growth. The Yozma Fund in Israel in 1992 demonstrates the success of government regulatory policy and could be emulated with similar emerging economies to design functional policies to enrich PVC markets.

3. METHODOLOGY

In the previous section, a comprehensive theoretical and academic review of related literature was performed. This section shows the research methods and research design used in the data collection. The study employed a mixed-method approach, integrating both quantitative and qualitative paradigms. This approach was chosen because it provided the researcher with an in-depth understanding of the research problem (Creswell, 2003). Institutional theory was used to provide an insight into the theoretical implications of government regulatory policy as a background for the direct and indirect involvement of government in VC market development.

3.1 Research hypothesis

The following research hypotheses offered direction to the study and enabled the measurement of the impact of government's role in nurturing the development of VC markets and SMEs' survival and growth:

• H1: Government regulatory policies positively impact the development of the VC market and SMEs' survival and growth in Uganda.

• H2: Hybrid VC financing influences the performance of SMEs in Uganda in terms of sales turnover, profitability and an increase in ROE.

3.2 Questionnaire and data collection

The main source of data was the Uganda Investment Authority (UIA) database because it contains the national Business and Information Technology registry data bank with a website and directory for SMEs (Uganda Investment Authority, 2016). More data was collected from the profiles of VC firms and online databases, such as Digest Africa, PitchBook and WeeTracker.

The statistical data was collected from 90 key respondents, namely entrepreneurs/own managers, VC-backed and non-VC-backed firms, government authorities and SME associations, from a population of n=300 SMEs by using a Likert scale survey questionnaire. From the 90 questionnaires distributed, 68 respondents returned adequately completed questionnaires, producing a response rate of 76 percent, suitable for data analysis.

Besides statistical data, qualitative data was collected from 16 out of 30 organised face-to-face interviews with key informant experts believed to have diverse knowledge about the study. This method allowed respondents to provide detailed information to ensure clarity on the research problem that the survey questionnaire might not have been able to elucidate.

3.2.1 Data analysis

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics and inferences produced from Excel and SPSS to compute the mean and standard deviation scores. Several inferential tests, including multiple regression analysis, Pearson correlation and analysis of variance (ANOVA), were conducted. In performing the tests, government regulatory policy, measured by government regulations and VC financing, was the predictor variable. The dependent variable was market development measured with proxies comprising annual sales, market expansion, profitability and ROE.

The multiple regression model equation was adopted to illustrate how the independent variable (government regulations and CIFs) influences the dependent variable (the growth of the VC industry and the survival and growth of SMEs). These were measured as sales, ROE and market expansion.

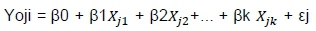

The Multiple Linear Regression model is illustrated as:

Y is the firm's performance (sales turnover, ROE and market expansion).

ß0 is the y-intercept wherein the value of y when Xj1, Xj2.....Xjkare equal to 0.

ß1 and ß2 are the regression coefficients that represent the change in y relative to a one-unit change inXj1,Xj2.....Xjk, respectively.

ßk is the slope coefficient for each independent variable.

X1= venture capital finance as one of the independent variable.

X2= co-investment funds as the second independent variable.

X3= government regulations as the third independent variable.

ej is the model's random error (residual) term.

The predictor variables are specified as a j and k matrix, where j is the number of observations, while k is the number of predictor variables. Each column of X denotes one independent variable and each row represents one observation, while y is the response for the corresponding row of X.

The VC-backed and non-VC-backed companies were binary variables that were allocated 1 to indicate they received VC financing and 0 if they did not receive VC financing.

The primary qualitative data was collected from open-ended survey questionnaires, face-to-face interviews, videos, audited accounts, narrative reports and the researcher's observations. The analysis of data was done using ATLAS.ti to assess the responses from the face-to-face interviews. This triangulation method which aggregates the in-depth interviews with secondary data offers a considerable understanding of the research problem (Creswell, 2003). The researcher conducted 16 face to face interviews with VC experts out of the 30 earlier targeted samples. The study found 16 interviews sufficient by relying on the saturation concepts. In support of the concept of saturation, Lowe et al., (2018) argue that saturation is a level at which the interviewer continues to get similar results not different from the earlier responses, implying that ideally there is no new data other than a replication of already collected data.

In light of this, the interviews attained a point of saturation at the 16th interviewee, because the respondents were producing similar results to earlier gathered data. Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill, (2009) argue that, when the point of saturation is attained, the results are a true representation of the sample. We conducted semi-structured interviews which enabled easy clarification of the ambiguous statements, allowed amplification of the qualitative results, and produced a more in-depth empirical account of the impact of government's involvement on VC market development with SMEs survival and growth.

3.2.2 Reliability and validity

The questionnaire was tested for reliability using the Alpha Cronbach's coefficient with a 95 percent significant confidence level and a 5 percent margin of error. The results showed a 98.4 percent confidence level for the survey questionnaire and a margin of error of 1.6 percent - much lower than the estimated 5 percent. This approach was also used by Biney (2018). The statistical tests relied on the two-sided tests represented as a 0.05 level of significance.

3.2.3 Ethical considerations

The study received approval from the Research Ethical Clearance Committee of the University of South Africa, College of Economic and Management Sciences in August 2019. Prior approval from the UIA and USSIA for access to their databases was also received. Prior consent from all the respondents was obtained. The respondents were informed that their participation in the research was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw from the study without any consequences. The respondents were also informed that the research instruments used for collecting data would be in the researcher's custody for not more than five years and their access to any third parties would be restricted; the research instruments would subsequently be destroyed permanently to discontinue future access and usage.

4. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

This section presents the data analysis and findings of the field survey. It is structured into two parts: the statistical data analysis and the main responses from face-to-face interviews.

4.1 Statistical analyses and findings

This section presents the statistical tests conducted to evaluate the hypotheses of the study, including descriptive statistics for mean and standard deviation scores, ANOVA, Pearson correlation coefficient and multiple regression. The data analysis and discussion of results were structured to address the research hypotheses, H1 and H2.

The first research hypothesis is the following:

• H1: Government regulatory policies positively impact the development of the VC market and SMEs' survival and growth in Uganda.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics performed for the analysis of annual sales, government regulations and regulatory framework. The rationale was to identify responses of the participants in terms of either agree or disagree to assist in further inferential tests.

Table 2 indicates a mean score of 3.3 and an SD of 0.9079 for regulatory policy framework and a mean score of 2.6 and an SD of 1.37 for government regulations. Results for the two variables show below the 3.5 benchmark thus denoting disagreement.

Generally, 68 percent (46 out of 68) of respondents disputed that the Uganda government regulatory framework does not support the growth of SMEs leading to increased fall out from business. These results imply that there is strong evidence to conclude that government regulatory policy encourages the growth of VC-funded firms. These findings were consistent with the studies of Adongo (2012), Bertoni and Tykova (2015) and Baldock (2016).

Besides, results showed a mean score of 3.8 and an SD of 0.87836 for direct involvement of VC, while about 63 percent of the respondents agreed that the involvement of VC in running early-stage firms contributed to the profitability growth of the portfolio companies preceding VC financing. Finally, when the respondents were asked if co-investments contributed to the annual sales growth of SMEs, the mean score for annual sales was 3.7 rounded to 4. These results demonstrate the positive impact of government regulatory policy on VC market development in general.

Further tests - regression and ANOVA analysis - were conducted to confirm the results since the mean scores alone may not be sufficient to arrive at a dependable conclusion. In Table 3, the results of the ANOVA test to determine the significance level of VC financing are presented.

Table 3 shows the ANOVA test results F-value is (4, 63) = 4.093 and p < 0.005. When p < 0.005; a strong significance level is indicated. The results indicate a significant level of 0.005. Government regulatory policy positively impacts the development of the VC market.

The presence of VCs in the management of SMEs is equally significant, VCs should always take the lead as autonomous limited partners to uphold the growth of SMEs and government should play the role of filling the financing gap.

These findings confirm the previous studies of Lerner (2010), Adongo (2012); Chemmanur et al., (2014); Bertoni and Tykvova (2015) and Baldock (2016). These authors conducted similar research and the results were supportive of government regulatory policy encouraging the development of the VC market. Conversely, our findings reveals that government CIFs in Uganda is very small and restricted to only one limited partner managing nine VC-funded SMEs.

In Table 4, the government regulatory policy on VC financing and VC's direct involvement variables were regressed. This was aimed at measuring the statistical correction between VC financing and government regulatory policy.

The results in Table 4 indicate R = 0.454 and R2 = 0.206. The total variability of 20.6 percent of VC financing is explained by changes in government regulations, VC's direct involvement, environmental factors and the regulatory framework. Drawing from the results above, the government entered into a partnership with PVC limited partners and contributed through the government's VC structures to fill the financing gap in early-stage firms avoided by PVC firms. The 20.6 percent increase in VC financing may have been a government VC contribution to the PVC firms to fill the financing gap. These results confirm that government policies play a pivotal role in boosting VC market development. These results are consistent with the findings of Cumming et al., (2017) Owen and Manson (2017) and Owen and Mason (2019).

The second research hypothesis is the following:

• H2: Hybrid VC financing influences the performance of SMEs in Uganda in terms of sales turnover, profitability and an increase in ROE

Several authors have used sales turnover and profitability parameters to measure the financial performance of a firm (Blackburn et al., 2013) in measuring the impact of VC financing, market expansion, profitability and ROE were considered as dependent variables. Correlation coefficient tests to determine the relationship between VC financing (independent variable) and market expansion, profitability and ROE were conducted. Table 5 shows the correlation coefficient tests.

Table 5 shows the correlation coefficient results run with market expansion at 0.000, profitability at 0.000 and ROE at 0.008, respectively. The correlation is significant when ** p < 0.01 *p < 0.05. All the results are below p < 0.01. This suggests that there is a strong positive correlation between VC financing and profitability, market share and ROE. These findings disclose that VC investment in funded companies enhances the growth in market expansion of the portfolio companies in terms of exports and internalisation, increased profits from a large market share and eventually high ROE for shareholders. The increase in VC investment in the funded companies with good ROE is an indicator of growing VC markets since the ultimate goal of VC is the maximisation of ROE.

A multiple regression test to ascertain the statistical relationship between profitability and VC finance was also performed. Profitability was chosen because it is the most used proxy in a firm's measuring of performance.

Table 6 indicates the hypothesis results obtained from the tests. A regression analysis was ran and the results indicate R = 0.435 and R2 = 0.189. The results suggest 18.9 percent of the total variability in profitability is explained by changes in VC financing in VC-backed firms. There is, therefore, strong evidence to suggest that the VC-backed companies had their profitability increased by 18.9 percent after receipt of VC financing.

Gompers et al., (2020) uncovered VC markets that flourished in developed economies, received government support through government CIFs in the PVC firms and, thereby, inspired foreign inward investments. These results conform to the studies of Lerner (2010), Baldock and North, (2015) and Colombo et al. (2016).

4.2 Face-to-face interview data analysis

The face-to-face interviews were conducted with business experts with a wealth of knowledge on VC markets and regulatory policy frameworks and included PVC firms, portfolio company managers/owners, government agencies and SME associations. Attempts to engage international development finance institutions (DFIs) to ensure all VC market key players were included in the survey were futile due to unexpectedly delayed responses; international DFIs were hence eliminated from the study.

Sixteen face-to-face in-depth structured interviews with business-oriented experts selected from the Kampala CBD and the Jinja, Mukono and Wakiso districts were executed. These districts were chosen because they hold a high concentration of SMEs and make high revenue contributions to the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA) (Uganda Revenue Authority, 2018).

The structured interviews lasted for over 45 minutes and were recorded and transcribed. Efforts to follow up with interviewees on issues that needed clarity were made. This method was chosen because it offered the opportunity to get a deeper insight into the impact of regulatory policy on the development of the VC market in Uganda.

The findings of these in-depth, face-to-face structured interviews are presented in the following sections. The analysis of the main interview responses is segmented according to the study objectives.

4.2.1 Impact of government regulatory policy on the VC market in Uganda.

Almost all of the respondents were positive about the influence of government regulatory policies on the development of the VC market landscape. One of the government respondents alluded to the fact that the Uganda government has made efforts to improve the policy framework. The respondent emphasised: "In 2015, the government enacted the national SME policy that gives a national definition of SMEs. It was reported that all government interventions in the entrepreneurship sector are based on this definition to help the venture capitalists fund SMEs with growth potential."

A functional regulatory policy needs to comprise tax incentives, tax breaks for investors and fund managers for the development of the VC market. From this perspective, the Uganda government ratified the content law policy to benefit companies producing 80 percent of their products for export. They benefit from five years of tax relief, thus enhancing productivity and increasing local exports to regional markets.

One of the fund managers concluded: "Government's direct involvement in the VC market would only help if the policies in which the SMEs are trained are well constructed. By doing so, that would assist to shape the VC ecosystem. However, the government of Uganda is just developing its VC industry framework." Correspondingly, one of the respondents stated: "Government has created a one-stop centre where SMEs can easily access all services in terms of new ventures, licence renewals, registration and the acquisition ofURA tax identification numbers (TINs)."The 'one-stop centre' comprises all key government agencies, namely the UIA, Uganda Registration Services Bureau (URSB) and Uganda Revenue Authority (URA), domiciled at Twed Towers in Kampala. This government approach has assisted to enhance the business processes concerning the registration of new companies, registration for TINs, issue of business permits and any other related business services. Furthermore, there was confirmation of VC regulation under the supervision of the Capital Markets Authority (CMA).

Despite the regulation of the VC industry under CPA, our findings revealed that the CMA mainly handles mature companies listed on the Uganda stock exchange market. Such an environment may not effectively support the growth of the VC market because the existing regulations are not conspicuous.

Furthermore, the Uganda government developed a national private sector development plan to create a favourable working environment for SMEs; for example, the UIA offered 10,000 workspaces in Namanve Industrial Park to SMEs interested in growing. Besides, the government has taken the initiative to create both local and international business markets, especially for the top 100 SMEs through business linkages, transnational corporations and technological transfers. More notably, the UIA introduced annual PE/VC conferences that bring together SMEs, DFIs, financial advisers, universities and VC firms for networking and understanding the importance of VC for SME growth. These findings point to the positive performance of the regulatory policy in encouraging VC development. However, fundamental issues of regulating VC contracts and protecting portfolio companies from exploitation by foreign VC firms were not supported.

Notwithstanding the government's regulatory policy benefit to the business fraternity, SMEs operate on a small scale without getting to IPOs or trade. One of the respondents stated: "In Uganda, it is not easy to exit a company because taxes, such as corporate tax and dividends, are high." This assertion confirms why no VC-backed firms have ever been offered for IPOs or trade sale. Our follow-up question on this matter exposed that SMEs in Uganda are mainly family-owned and there is less interest to list on the Uganda stock exchange market. One of the respondents stated: "I do not have any interest to get listed on the stock exchange market because you lose the direction of your company."

4.2.2 Influence of hybrid VC financing on SMEs performance in Uganda

There was consensus from all respondents endorsing VC financing for improving annual sales revenue preceding receipt of VC funds. These results match with the statistical findings reported in the earlier section. The VC-funded companies realised 30 percent sales revenue growth after the receipt of VC funding. A large portion of VC financing directed to the agribusiness and manufacturing sectors was also observed. One of the interrogated fund managers disclosed: "Venture capital financing has a high social impact in agriculture because Uganda is gifted by nature with two seasons annually and 78 percent of the population is involved in the agriculture sector." Given that the ultimate goal of the VCs is to maximise ROE, they often search for high growth potential startup firms in anticipation of high returns at the exit stage.

The findings from the interviews revealed that VC-funded companies recognised an increase of 30 percent in annual profits. These results are consistent with the statistical results. However, some respondents shared their fear that VC firms were taking a higher share of ROE (about 20%) while portfolio companies had the least share.

Many respondents hailed government efforts to provide tax incentives to SMEs; good performance in terms of volume of local exports and compliance with the tax laws were demonstrated. There was evidence that 2 percent of SMEs had benefited from the content law policy and others benefited from zero-rated products and VAT claims. Several respondents confirmed an increase in their annual profits to have been attributable to the direct involvement of VC.

Alongside VC financing, fund managers secure seats on the boards of funded companies and render technical guidance and give direction on the performance of these companies. That said, one of the respondents noted: "The best financing in business is your profits. The higher the profitability of your business, the higher the business growth." In light of the above, while creating supportive government regulations is extremely valuable, the vital role of fund managers in the management of VC-funded companies, specifically GSVC companies, should not be overlooked.

All in all, respondents attested that VC financing positively influenced the growth of SMEs. A high number of respondents exposed VC as the most viable source of funding for startup firms to address the problem of lack of finance which affects business growth. Government supportive policies, together with tax incentives and tax breaks for new ventures, have become an emerging issue for the development of VC markets. Conversely, some respondents had little knowledge about government tax incentives.

Attention-grabbing results emanated from one of the business angels who lamented that there were no incentives: "Everything is business as usual. There is no deliberate effort by the government to boost VC market development." These results confirm the limited literature available to business entrepreneurs and practitioners about GSVCF. Therefore, the government should make efforts to train SMEs and increase awareness of GSVCF to key players in the VC market.

Drawing from the findings above, Uganda's VC landscape is still small, fragmented and underdeveloped. CIF to the large SME sector remains miniscule and SMEs have limited access to alternative financing. Only one government CIF in Pearl Capital Partners (PCP) Uganda with pooled funds from the National Security Fund, a government body, EU and Gatsby was discovered (PCP Uganda, 2019). Surprisingly, our findings uncover that the government contributed the least VC amount to the CIF. Therefore, it is difficult to square results to the government alone since the international development partners made the highest share contribution.

Although government has made attempts to enhance the VC market expansion, CIFs in Uganda is still insignificant as compared to Kenya, Nigeria and Nigeria. As such, Uganda's VC market has not been systematically exhausted owing to the paucity of empirical works to support the proficiency GVC in enhancing SME growth, and in addition, further understanding of this topic is needed as entrepreneurs are not aware of the existence and benefits of GVCF in Uganda.

5. CONCLUSION

This paper explores the impact of government's involvement in the VC market on small-medium enterprises' survival and growth in East Africa, with evidence from Uganda. This paper confirms that VC financing is a precursor for the quicker growth of early-stage enterprises. This was recognised from Uganda government's intervention to create supportive regulatory policies and its attempts to increase VC supply into the PVC firms. Whereas GVCF in Uganda is still unpopular, National Social Security Fund (NSSF) CIF into PCP Uganda (2019), has revealed fabulous performance of the VC-backed firms and uphold of entrepreneurship sector development in the country. Although the results support government regulatory policy, Uganda's VC landscape is still small, fragmented and underdeveloped. Government co-investment in the large SME sector remains limited and, with a lack of access to financing sources, SME growth is impeded. Further research in this field involving a large sample of both PE and VC financing is desirable to contribute to the existing literature.

Drawing from our findings and earlier literature works, it is important for emerging economies like Uganda to respond to nearly essential VC gaps that are not always correctly resolved by the contemporary VC supply (Deventer & Mlambo, 2008; Agyeman, 2010; Shanthi et al., 2018). Precisely, Uganda's VC policies are still in the design stage and not well regulated when compared to Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. These countries in question established PE & VC association which provide insights in the VC market.

This study further unlocks numerous opportunities for future research since it was limited to government VC policy for early-stage entrepreneurial ventures. Despite the major goal of VCs to invest in early-stage companies and exit in 10 years, portfolio managers claim that trade sale or IPOs are associated with high costs and potential loss of control of businesses hence SMEs in Uganda hold less interest in opting for IPOs. The results of this study may also be prone to bias due to the endogeneity factor because VC financing and government regulatory policy are interdependent variables. This study was limited to the supply side of VC financing; little attention was directed to the demand side. The willingness of entrepreneurs to accept VC financing affects VC growth if they choose not to welcome the fund manager. For the VC industry to flourish there must be sufficient early-stage firms with growth potential to absorb patient capital. Finally, generic government regulations applied to regulate the VC industry without any clear-cut financial regulations were observed. For this reason, UIA is unable to keep track of VC deals and legally provide support for VC fundraising. This problem is not only in Uganda but also in several developing countries that have not legalised the VC capital financial instrument (Metrick & Yasuda, 2010) and this creates the risk of exploitation by foreign VC fund managers to SMEs.

Intrinsically, government's intervention to increase CIFs into PVC firms may offer benefits to fix the equity gap, especially in countries with VC scarcities (Baldock & Mason, 2015; Colombo et al., 2016). Additionally, emerging economies in the Sub Saharan Africa ought to replicate the success of the US venture capital market, for instance, to increase VC supply through government CIFs into the private VC firms and create a supportive environment to inspire the foreign VC investors (Baldock & North, 2015; Info-Dev/World Bank, 2016; Karsai, 2018).

As a result, this paper offers novel knowledge on the under-explored research on the government's role in nurturing the VC market and the survival and growth of SMEs in emerging nations like Uganda. Some of the best practices from a global perspective are further highlighted and existing gaps in the current literature are disclosed to assist policymakers and practitioners in designing appropriate policies that inspire the growth of the VC ecosystem.

REFERENCES

Adongo, J. 2012. The Impact of the Legal Environment on Venture Capital & Private Equity in Africa: Empirical Evidence. [Internet: https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/the_impact_of_the_legal_environment_on_venture_capital_and_private_equity_in_africa_empirical_evidence.pdf, downloaded on 18.04.2019]. [ Links ]

Agyeman. S. 2010. Challenges facing venture capitalists in developing economies: An empirical study about venture capital industry in Ghana. [Internet: https://umu.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:392862/FULLTEXT01.pdf, downloaded on 18.04.2019] [ Links ]

Kato. A.I. & Tsoka, G.E. 2020. Impact of venture capital financing on small- and medium-sized enterprises' performance in Uganda. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 12(1):a320. [https://doi.org/10.4102/saJesbm.v12i1.320]. [ Links ]

Baldock, R. 2016. An assessment of the impact of the UK's Enterprise capital funds. Environment and planning C: Government and Policy. 34(8):1556-1581. [https://Doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15625995]. [ Links ]

Blackburn, R.A., Hart, M. & Wainwright, T. 2013. Small business performance: business, strategy and owner-manager characteristics, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(1):8-27. [https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001311298394]. [ Links ]

Baldock, R. & North, D. 2015. The role of UK government hybrid venture capital funds in addressing the finance gap facing innovative SMEs in the post-2007 financial crisis-era'. Research Handbook on Entrepreneurial Finance; Chapter 8:125-146, Edward Elgar Publishing. [https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783478798.00014]. [ Links ]

Baldock, R. & Mason, C. 2015. Establishing a new UK finance escalator for innovative SMEs; The roles of the enterprise capital funds and Angel Co-investment fund capital. An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance. 17(1-2):59-86. [https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2015.1021025]. [ Links ]

Bertoni, F., & Tykvova, T. 2015. Does governmental venture capital spur invention and innovation? Evidence from young European biotech companies. Research Policy, 44(4):925-935. [ Links ]

Biney, C. 2018. The impact of venture capital financing on SMEs growth and development in Ghana. Business Economics Journal, (9):370. [https://doi.org/10.4172/2151-6219.1000370]. [ Links ]

Brander, J., Du, Q., & Hellman, T. 2015. The effects of government-sponsored venture capital: International evidence. Journal of Finance, 19:571-618. [ Links ]

Brander, J., Egan, E. & Hellmann, T. 2010. Government Sponsored Versus Private Venture Capital: Canadian Evidence (NBER Chapters), International Differences in Entrepreneurship, 275-320. National Bureau of Economic Research Inc. [ Links ]

Bruton, D., Ahlstrom, D. & Puky. T. 2009. Institutional differences and the development of entrepreneurial ventures: a comparison of the venture capital industries in Latin America and Asia. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(5):762-778. [ Links ]

Callagher, L.J., Smith, P. & Ruscoe, S. 2015. Government roles in venture capital development: a review of current literature. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 4(3):367-391. [https://doi.org/10.1108/JEPP-08-2014-0032]. [ Links ]

Chemmanur. J., Loutskina. E. & Xuan-Tian. 2014. Corporate Venture Capital, Value Creation, and Innovation' The Review of Financial Studies, 7(8):2434-2473 [https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhu033]. [ Links ]

Colombo, M., Cumming, D. & Vismara, S. 2016. Government venture capital fund for innovative young firms. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(1):10-24. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2003. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Cumming, D. & Johan, S. 2016. Venture's economic impact in Australia. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(1):25-59. [ Links ]

Grilli, L. & Murtinu, S. 2014. Government, venture capital and the growth of European high-tech entrepreneurial firms. Research Policy, 43(9); 1523-1543, [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.04.002] [ Links ]

Cumming, D, Grilli, L & Murtinu, S. 2017. Governmental and independent venture capital investments in Europe: A firm-level performance analysis. Journal of Corporate Finance, 2017, 42(C); 439-459 [ Links ]

Cumming, D. & Macintosh, J. 2006. Crowding Out Private Equity: Canadian Evidence. Journal of Business Venturing, 21:569-609. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.323821]. [ Links ]

Deloitte & NVCA. 2012. Global Trends in Venture Capital: How Confident Are Investors? [Internet: http://www.deloitte.com/assets/DcomUnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/Tustmt/us_tmt_2012VCSurvey_08082013.pdf, downloaded 15.09.2018]. [ Links ]

DiMaggio, P. & Powell, W. 1983. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organisational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2):147-160. [ Links ]

Deloitte & SAVCA, 2009. The calm after the storm? The South African private equity confidence survey, [internet: https://www.savca.co.za, downloaded on 15.09.2018]. [ Links ]

Deventer, B., & Mlambo, C. 2008. Factors influencing venture capitalists' project financing decisions in South Africa. South African Journal of Business Management, 40:33-41. [ Links ]

European Commission, 2017. Effectiveness of Tax Incentives for Venture Capital and Business Angels to Foster the Investment of SMEs and Start-Ups; European Commission: Brussels, Switzerland. [ Links ]

Gaies, B., Najar, D., Maalaoui, A., Kraus, S. & El Tarabishy, A., 2021. Does financial development really spur nascent entrepreneurship in Europe?-A panel data analysis. Journal of Small Business Management, 1 -48. [https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1896722]. [ Links ]

Gompers, P., Gornall, W., Kaplan, S. & Strebulaev, A. 2020. How do venture capitalists make decisions?' Journal of Financial Economics, 135:169-190. [ Links ]

Gompers, P., Kovner, N. & Lerner, J. (2009). Specialization and Success: Evidence from Venture Capital. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 18(3):817-844. [ Links ]

Gompers, P. & Lerner, J. 2001. The venture capital revolution. Journal Economic Perspective, 15(2):145-168. [https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.2.145]. [ Links ]

Gompers, P. & Lerner, J. 1999. The Venture Capital Cycle, 1st ed., the MIT Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Gu, W., & Qian, X. 2019. Does venture capital foster entrepreneurship in an emerging market? Journal of Business Research, 101:803-810. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.011]. [ Links ]

Info-Dev/World Bank. 2016. Growth Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries. A Preliminary Literature Review'. Working Paper | February, 2016, The World Bank Group, New York. [Internet: https://www.infodev.org/infodev-files/growth_entrepreneurship_in_developing_countries_-a_preliminary_literature_review_-_february_2016_-_infodev.pdf, downloaded on 15.04.2019]. [ Links ]

Jihye. J., Juhee, K., Hanei, S. & Dae-il, N. 2020. The Role of Venture Capital Investment in Startups' Sustainable Growth and Performance: Focusing on Absorptive Capacity and Venture Capitalists' Reputation. Sustainability. 12. 3447. 10.3390/su12083447. Working Paper' 1818H Street NW Washington, DC 20433. [ Links ]

Invest Europe. 2020. Investing in Europe: Private Equity Activity 2019; Invest Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [ Links ]

Karsai, J. 2018. Government venture capital in central and Eastern Europe. Venture Capital, 20:73-102. [https://doi.orh/10.1080/13691066.2018.1411040]. [ Links ]

KPMG & EAVCA. 2019. Private Equity Sector Survey of East Africa for the period 2017 to 2018, Nairobi Kenya. [ Links ]

Kallay, K. & Jaki, E. 2020. The impact of state intervention on the Hungarian venture capital market. Economic Research, 33(1):1130-1145. [https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1629979]. [ Links ]

Kallmuenzer, A., Lorenzo, D., Siller, E., Rojas, A. & Kraus, S. 2021. Antecedents of good governance of hospitality family firms. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 22(3):177-190. [ Links ]

Lerner, J., Leamon, A. & Garcia, S. 2016. Best Practices in creating a Venture capital ecosystem. [Internet: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Best-Practices-in-Creating-a-Venture-Capital-Ecosystem.pdf, downloaded on 15.04.2019]. [ Links ]

Lerner, J, 2010. The future of public efforts to boost entrepreneurship and venture capital. Small Business Economics, 35(3):255-264. [ Links ]

Lerner, J. & Nanda. R. 2020. Venture Capital's Role in Financing Innovation: What We Know and How Much We Still Need to Learn, Journal of Economic Perspective, 34(3):37-261. [ Links ]

Lerner. J. 2020. The future of public efforts to boost entrepreneurship and venture capital. Small Business Economics Journal, 35:255-264. [https://doi10.1007/s11187-010-9298-z]. [ Links ]

Lingelbach, D. 2015. Developing venture capital when institutions change Venture Capital. An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 17(4):327-363. [https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2015.1055060]. [ Links ]

Lowe H, Henry L, Müller LM, Joffe VL. Vocabulary intervention for adolescents with language disorder: a systematic review. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(2):199-217. [https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12355. Epub 2017 Nov 21. PMID: 29159971. [ Links ]

Matisone, A. & Natalja, L. 2020. The Impact of Public Interventions on Self-Sustainable Venture Capital Market Development in Latvia from the Perspective of VC Fund Managers. Journal of Open Innovation Technology Market and Complexity, 6(3):53. [https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6030053]. [ Links ]

Maurizio, C. 2020. VC Opportunities and Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa, Global Private Capital Association. New York, NY 10018 [Internet: https://www.globalprivatecapital.org/research/vc-opportunities-and-challenges-in-sub-saharan-africa, downloaded on 20.04.2020]. [ Links ]

Mboto, W., Offiong, A. & Udoka, O. 2018. Venture Capital Financing and the Growth of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Calaber Metroplis, Cross River State, Nigeria' World Journal of Innovative Research, 5(1):07-16. [ Links ]

Metrick, A. & Yasuda, A. 2010. Venture Capital and the Finance of Innovation, John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

Munari, F. & Toschi, L. 2015. Assessing the impact of public venture capital programs in the United Kingdom: Do regional characteristics matter? Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2):205-226. [ Links ]

Murray, G. 2007. Venture capital and government policy. In H. Landstrom (Ed.), Handbook of research on venture capital. Cheltenham, London: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Murray, G., Cowling, M., Liu, W. & Kalinowska, B. 2012. Government co-financed 'Hybrid' Venture Capital programs: Generalizing developed economy experience and its relevance to emerging nations, UK Kauffman International Research and Policy Roundtable, Liverpool, 11-12 March. [Internet: http://www.kauffman.org/~/media/Kauffman.org/archive/resource/2012/5/irpr_2012_murray.pdf]. [ Links ]

NVCA (National Venture Capital Association). 2020. Yearbook. [Internet:https://nvca.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NVCA-2020-Yearbook.pdf, downloaded on 23.03.2021]. [ Links ]

OECD. 2012. Measuring Regulatory Performance Evaluating the impact of regulation and regulatory policy. . Expert Paper No. 1, August 2012. [Internet: https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/2Radaelli%20web.pdf, downloaded on 15.04.2019]. [ Links ]

Owen, R. & Mason, C. 2019. Emerging trends in government venture capital policies in smaller peripheral economies: Lessons from Finland, New Zealand, and Estonia. Strategic Change, 28(1):83-93. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2248]. [ Links ]

Owen, R. & Mason, C. 2017. The role of government CIFs in the supply of entrepreneurial finance: An assessment of the early operation of the Angel co-investment fund. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 35(3):434-456. [ Links ]

Owen, R., North, D. & Mac- Bhaird, C. 2019. The role of government venture capital funds: Recent lessons from the U.K. experience'. Strategic Change. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Asia, 28(1):69-82. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2247 Accessed on 23.03.2021]. [ Links ]

PCP Uganda. 2019. Yield Uganda Investment Fund, Press Release, Pearl Capital Partner, Kampala. [Internet: http://pearlcapital.net/documents/yieldteaser.pdf]. [ Links ]

Richard, T. & Mason, C. 2019. Venture Capital 20 years on: reflections on the evolution of a field. Venture Capital, 21(1):1-34. [https://doi.org/:10.1080/13691066.2019.1562627]. [ Links ]

Rosa, M., Sukoharsono, E. & Saraswati, E. 2019. The Role of Venture Capital on Start-up Business Development in Indonesia. Journal of Accounting and Investment, 20(1):55-74 [http://doi.org/10.18196/jai.2001108]. [ Links ]

Scott, W. 1995. Institutions and Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications [ Links ]

Shanthi, D., McGinnis, P. & Schneider, S. 2018. Survey of the Kenyan Private Equity and Venture Capital Landscape, Policy Research Working Paper 8598. World Bank Group [ Links ]

Shojaei, S, Motavasseli, A. & Chitsazan, H. 2018. Institutional barriers to venture capital financing: an explorative study for the case of Iran [Internet: www.emeraldinsight.com/2053-4604.htm, downloaded on 15.04.2019]. [ Links ]

Thies, F., Huber, A., Bock, C., Benlian, A. & Kraus, S., 2019. Following the crowd-does crowdfunding affect venture capitalists' selection of entrepreneurial ventures?. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(4), 1378-1398. [https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12447]. [ Links ]

Tykvova, T. 2017. Venture Capital and Private Equity Financing: An Overview of Recent Literature and an Agenda for Future Research. Journal of Business Economics, 88(3):352-362 [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-017-0874-4] [ Links ]

Uganda Investment Authority. 2016. Second Private Equity, and Venture Capital Conference 2016, Kampala Serena, 24th-25th June 2015. [Internet: https://www.ugandainvest.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/PEVC, downloaded on 15 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Uganda Revenue Authority. 2018. Revenue Performance Report Financial Year 2017/18; 16th July 2018. [internet:https://www.ura.go.ug/resources/webuploads/GNRART/Annual%20Revenue%20Report_2017_18.pdf, downloaded on 25.09.2018]. [ Links ]

WeeTracker, 2021. Africa Venture Capital in 2020. [Internet: https://weetracker.com/2020/12/28/african-venture-capital-2020-africo-weetracker-report, downloaded on 15.04.2021]. [ Links ]

Yongqiang, L, 2014. The Impact of Regulation on The Financial Performance of Small Corporations in Australia: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach; International Academic. Conference Proceedings; New Orleans, USA' West East Institute 104. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author