Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Contemporary Management

On-line version ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.18 n.2 Meyerton 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.35683/jcm21026.119

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Effects of entrepreneurial orientation and external business environment on entrepreneurial intentions of STEM students in Nigeria

O JegedeI, *; C NieuwenhuizenII

IDHET-NRF South African Research Chair in Entrepreneurship Education, University of Johannesburg, South Africa Email: oluseyej@uj.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1972-1516

IIDHET-NRF South African Research Chair in Entrepreneurship Education, University of Johannesburg, South Africa Email: cecilen@uj.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4925-3212

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY: This study investigates the effects of entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurship education, and external business environment on entrepreneurial intention of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) students attending a federal university in southwestern Nigeria. This inquiry was conducted by exploring the one hundred and fifty students selected from six relevant faculties in the university

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: The main research instrument was a set questionnaire designed to elicit entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurship infrastructure, and entrepreneurial intention. Descriptive and inferential statistics (partial regression) were used to determine the relationship between entrepreneurial intention and the other variables

FINDINGS: The findings identified that while entrepreneurship orientation and entrepreneurship education are more closely associated with entrepreneurship intentions, and entrepreneurship education was the most important driver of entrepreneurship intentions among STEM students. The study also established that the entrepreneurial ecosystem of the STEM students is somewhat weak thus having little of no influence on driving entrepreneurial interest among the STEM students

RECOMMENDATIONS/VALUE: The study thus concludes that theoretical knowledge from business schools, combined with practical knowledge from incubators, workshops, laboratories, and technology transfer offices, are necessary for stimulating entrepreneurship intentions among the STEM students

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: It was established in the study taking entrepreneurship modules or degrees such as MBA at the university and spontaneous exposure to entrepreneurship education have a lot of influence on the build-up of entrepreneurial interest among STEM students. It also established that effective entrepreneurial learning can also occur through science parks, incubators, workshops, laboratories, and technology transfer offices. Thus, Universities need to encourage and support STEM students by exposing them harnessing the different channels of entrepreneurial learning

JEL CLASSIFICATION: O33

Keywords: Entrepreneurial intention; Entrepreneurial orientation; Entrepreneurship education; Entrepreneurship infrastructure; STEM students.

1. INTRODUCTION

Are entrepreneurs born or made? This question has been trending in recent scholarly work. Though many research studies have attempted to answer this question, none has categorically said if entrepreneurs are born or made. The popular belief used to be that entrepreneurs are born with natural abilities (Blume-Kohout, 2016; Forbes, 2017; Erhardt & Haenni, 2018). However, with the proliferation of business schools and entrepreneurship education modules at different levels within knowledge institutions, the fact has become apparent that entrepreneurs can be made (through training).

The idea is that all entrepreneurs need some degree of support from their environment. Entrepreneurs also need to be trained at various stages of their development (Nieuwenhuizen, 2016; Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2016; Kirkley, 2017; Neck & Corbett, 2018). Entrepreneurship education programmes are developed to induce students to become entrepreneurs (Kakouris & Georgiadis, 2016; Ramchander, 2019). Entrepreneurship education and training can be through formal means, i.e., a student learning from an instructor by enrolling for an entrepreneurship module or attending an entrepreneurship training course (Martin et al., 2013). An informal means of education could be acquired due to spill-over effects from a colleague, partner, and/or associate with entrepreneurial experience (Lerner & Malmendier, 2013).

The university context also plays a vital role in student entrepreneurship (Bergmann et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2017; Israr & Saleem, 2018). The importance of research support facilities and infrastructure for entrepreneurship cannot be overemphasized (Guerrero et al., 2018; Colombo & Piva, 2020; da Cruz et al., 2021). An entrepreneurial ecosystem controls the landscape and value of entrepreneurship activities by influencing the channels and latent benefits accompanying identifying business prospects and pursuing the same (Wright et al., 2017). An entrepreneurial ecosystem for students has many dimensions. It includes entrepreneurship courses, incubators, accelerators, grants, and business plan competitions (Wright et al., 2017; Breznitz & Zhang, 2019; Nicholls-Nixon et al., 2020). The provision of this system has a significant influence on the success of the student's entrepreneurial venture.

Some studies have also touched on the importance of the innate characteristics of the entrepreneur (Antonioli et al., 2016; Tsai et al., 2016;). Some of these have identified that just as there are external factors that determine entrepreneurship-related activities among students, internal factors (such as entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial capability) influence a student's choice for embracing entrepreneurship (Antonioli et al. 2016). In addition to entrepreneurship education and the provision of infrastructure for entrepreneurship, the individual's level of self-motivation in the face of challenges is a vital factor in escalating the student's entrepreneurship interest.

Discussions on what motivates entrepreneurship among students have not been fully exhausted in literature. The factors identified in the literature to date mostly revolve around different internal and external factors to the entrepreneur. The internal factors identified in the literature include background characteristics of the student, entrepreneurship orientation, entrepreneurship capability, while external factors found in the literature include exposure to entrepreneurship education and appropriate infrastructural support (Nieuwenhuizen, 2016; RezaeiZadeh et al., 2017; Syam et al., 2018; Yi & Duval-Couetil, 2018; Ferreira et al., 2019;). The present study posits that either internal or external factors or some internal and external factors can influence entrepreneurial interest in entrepreneurs. Hence, the present study thus explores the effects of background characteristics, entrepreneurial orientation (an innate factor), and external business environment (an external factor) on STEM students' decision to become entrepreneurs. Thus, the research sought out to answer the following questions:

• What can background characteristics significantly influence the entrepreneurial intentions of STEM students in Nigeria?

• What entrepreneurial orientation can significantly influence the entrepreneurial intentions of STEM students in Nigeria?

• What external business environment can significantly influence the entrepreneurial intentions of STEM students in Nigeria?

• What is the most significant driver of entrepreneurial intentions among STEM students in Nigeria?

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: The following section is the literature review focusing on entrepreneurial intention, entrepreneurial orientation, external business environment, and drivers of entrepreneurial intentions. Section three presents the methodology (research design, instruments and validation, data collection data analysis, and interpretation) used in the study. The empirical analysis, results, and discussion were reported in section four. While the conclusion and implication of the study were reported in sections five and six, respectively.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature review section discusses concepts relating to motivation for entrepreneurial intention, entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurship education, and entrepreneurship infrastructure, based upon the various perspectives presented in the literature.

2.1 Entrepreneurial intention

While studies on entrepreneurial intention seem to have been discussed extensively in the literature, findings from these studies show that the various contributions to the topic are not yet exhausted. From previous studies, we observed that the popular drivers of entrepreneurial intentions are: personality traits (Zhao et al., 2010), cognitive style (Siyanbola et al., 2011; Siyanbola et al., 2012; Fayolle et al., 2014; Delanoë-Gueguen & Liñán, 2019), risk preferences (Barbosa et al, 2007; Jegede & Nieuwenhuizen, 2020a), autonomy (Al-Jabari et al., 2017; Al-Jubari et al., 2019), self-fulfilment (Segal et al., 2005), the external environment (Achchuthan & Kandaiya, 2013; Meyer & Meyer, 2020) and entrepreneurial education (Mahendra et al., 2017). The variables listed above all fall in literature can be groups into three broad categories viz: background/family characteristics, innate characteristics, and external factors. Previous works have highlighted the role of external factors such as institutional ecosystems (Ibrahim & Mas'ud, 2016; Hadjimanolis, 2016), fear of failure (Tsai et al., 2016) and fraud (Allini et al., 2017) a role in the development of individuals' entrepreneurial intentions. However, despite the numerous scholarly contributions on the topic of drivers for entrepreneurial intentions, the analysis is not sufficiently comprehensive to draw wide-ranging conclusions. Many other studies have advanced the notion that the internal characteristics of the entrepreneur are likely to be the most crucial factor that spurs entrepreneurial intentions. Indeed, some scholarly works exist with the impression that entrepreneurs are born with entrepreneurial capabilities (Light, 2006; Harmsen, 2018). The present study strongly insinuates that context has a significant effect on entrepreneurial matters. Hence, it is not only innate and external factors that influence entrepreneurial intentions. Existing literature on drivers for entrepreneurial intentions originates mainly from Europe, Asia, and the United States of America. Scholarly works capturing the dynamics of entrepreneurship on the Africa continent are scanty. One of the main differences between developing and developed countries is that the informal economy dominated by entrepreneurs is extensive in developing countries. The study thus puts forward the view that it is important to understand what drives entrepreneurs. The present study also opines that it is also necessary to comprehend what drives the entrepreneurial intentions of STEM researchers in African countries. The reason for this view is because the contribution of science and technology-based entrepreneurs to economic growth and development cannot be overemphasized (Mian et al., 2016; Yunis et al., 2018; Jegede & Nieuwenhuizen, 2020b; Abodunde et al., 2020, Abodunde & Jegede, 2020).

2.2 Entrepreneurial orientation

Most of the information found in the literature indicates that entrepreneurship research is largely skewed towards environmental characteristics and entrepreneurial opportunities as being the main incentives for entrepreneurship (Shirokova et al., 2016; van der Zwan, et al., 2016; Muñoz & Cohen, 2018; Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018; Jegede & Nieuwenhuizen, 2020b). Even though this effort has significantly broadened our understanding of the dynamics of entrepreneurial intention, it disregards the importance of the human factor (internal capabilities of the entrepreneur). This study notes that the few empirical studies carried out in this area are insufficient to conclude the role of the human factor in driving entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurial orientation has long been used as an organizational-level construct. However, literature recently began to use entrepreneurial orientation as an individual entrepreneur construct and sometimes referred to it as individual entrepreneurial orientation or intrapreneurial orientation (Koe, 2016; Schachtebeck et al., 2019). According to the reviewed literature, the most used proxies for entrepreneurial orientation have been innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-taking (Koe, 2016; Núñez-Pomar et al., 2016; Linton & Kask, 2017; Al Mamun et al., 2017; Hernández-Perlines et al., 2020). These studies have revealed that successful entrepreneurs often possess characteristics such as: the need for achievement, the ability to ensure locus of control, a high self-esteem, and an innovativeness capability (Abdul-Mohsin et al., 2012). Other variables that have been used in past works to capture entrepreneurial orientation include: having self-confidence, being committed to completing tasks, having an extensive network of friends and colleagues, eagerness to use new technologies, searching for new opportunities, and being resilient (Koe, 2016; Randerson, 2016; Wales, 2016; Al Mamun et al., 2017; Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018; Hernández-Perlines et al., 2020). Hence, the present study used the variables explored in previous studies listed above.

2.3 External business environment

The external business environment of the entrepreneur can be viewed from different perspectives. Literature has identified the external business environment as the socioeconomic environment of the entrepreneur (Yaluner et al., 2019), i.e., the extent of external knowledge (including entrepreneurship education) accessible to the entrepreneur (Agbonlahor, 2016; Hoppe, 2016; Bischoff et al., 2018; Byun et al., 2018). Other pieces of literature view the entrepreneur's external business environment as the range of technical support/entrepreneurship infrastructure available to them, such as science parks (Parry, 2018; Xie et al., 2018; Audretsch & Belitski, 2019), incubators (Parry, 2018; Audretsch & Belitski, 2019), clusters (Ma & Zhou, 2017; Jegede et al., 2020a; Jegede et al., 2020b; Ogunjemilua et al., 2020), special economic zones (Ambroziak & Hartwell, 2018; Narula & Zhan, 2019), export processing zones (Sosnovskikh, 2017), free trade zones (Newman & Page, 2017; Liu et al., 2018). All these studies show that to a large extent, the external business environment influences the chances of success of a 'startup' or the entrepreneur, regardless of their innate abilities (Intra/entrepreneurial orientation). The present study, thus, also explores the external environment from a multi-dimensional view of exposure to entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship infrastructure (technical support) available to researchers in the STEM field in a federal university in southwestern Nigeria that could enable them to become successful entrepreneurs.

2.4 Theoretical framework - drivers of entrepreneurial intention

Different studies have used various frameworks to understand what drives people's entrepreneurial intentions. The theory of planned behaviour by Ajzen (1991) observed the outcome of attitudes towards entrepreneurship, personal norms, and social regulations upon entrepreneurial intentions. Other studies have employed the expectancy theory to measure the impact of perceived appeal and probability on an individual's entrepreneurial interests (Fitzsimmons & Douglas, 2011; Guerrero et al., 2008).

Another well-explored theory is social learning advanced by Bandura, (1977; 1989; 1997). The theory of social learning illustrates that self-efficacy is an essential precursor of entrepreneurial intention. Recent studies that explore the social learning theory include those of Day and Allen (2004), Hao et al. (2005), and Gu et al. (2017). Despite the volume of work that has been carried out on entrepreneurial intention, our current understanding of what drives entrepreneurial intention is far from comprehensive.

The present study builds on the body of knowledge known as the motivation theory (Bandura & McClelland, 1977; McClelland, 1985,1988; Smith et al., 1992). McClelland's human motivation theory, developed in 1961, states that every person has one of three main driving motivators: the need for achievement, affiliation, and/or power. These motivators are not inherent; we develop them through our culture and life experiences. McClelland points out that regardless of age, sex, race, or culture, everyone possesses and is driven by at least one of these needs. McClelland proposes that the specific needs of individuals are acquired and shaped over time through their experiences. Thus, motivation theorists contend that humans with different needs are motivated differently (Davis et al., 1992; Kasser & Ryan, 1996; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006; Gillespie et al., 2016).

Academic studies have found that the students' background characteristics also influence their choice for entrepreneurship (Gurel et al., 2010; Yildirim et al., 2016; Farrukh et al., 2017; Torres et al., 2017; Israr & Saleem, 2018; Jakubiak, 2020). The present study thus develops an overarching framework to determine the effect of entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurship support facilities, and background characteristics on the entrepreneurial intentions of STEM students, using those attending a Nigerian university as a case study.

3. METHODOLOGY

The methodology section presents the study design, the data collection process, the research instrument used and how data was analysed.

3.1 Research design, instruments and validation

This study relied on the design and administration of a questionnaire developed from relevant theoretical framework sections discussed in the literature review. The questionnaire was pre-tested at the co-author's university in South Africa before administering it to the main survey in Nigeria through a pilot study. Feedback from the pilot study showed that the questionnaire was satisfactory except for a few minor changes, which were implemented before the formal data collection.

3.2 Data collection

As mentioned previously, the survey was conducted at a federal university in southwestern Nigeria. The main research instrument was the questionnaire specifically premeditated to elicit information from students drawn from six faculties (Agriculture, Built Environment, Engineering, Medical Sciences, Pharmacy, and Science) relevant to the study. The sampling technique involved the purposive selection of the highest-ranking university in Nigeria in terms of research outputs (publications and patents) and, secondly, both final year undergraduates and postgraduate Diploma, Master and PhD students. A total of 150 accurately completed questionnaires were analysed.

3.3 Data analysis and interpretation

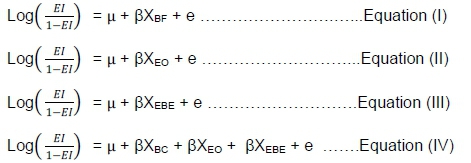

The completed questionnaires were coded and entered into a spreadsheet. The coded data were analysed using SPSS 26.0 in response to the study objectives. Partial Logistic Regression was conducted to test the impact of each explanatory variable: background factors (Eqn I), entrepreneurial orientation (Eqn II), external business environment (Eqn III) on the outcome variable (entrepreneurial intention of the STEM students).

EI = Probability of the student developing entrepreneurial intentions

1 - EI = Probability of the student NOT developing entrepreneurial intentions

μ = Constant variable (intercept) - null hypothesis

Xbf = Explanatory variable (background factors)

Xeo = Explanatory variable (entrepreneurial orientation)

Xebe = Explanatory variable (external business environment)

e = Error term

3.4 Characteristics of the binary logistic regression model

The model used in this present study ensured that:

• there is no multicollinearity among the explanatory variables,

• the appropriate sample size is used for accurate predictions,

• the explanatory variables are linearly associated with the log of odds,

• the dependent variable is binary,

• the observations to be independent of each other.

4. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

This section presents the interpretation of the data collected and analysed. It presented the results under the following sub-headings: background characteristics of the STEM students, entrepreneurial intention of the students, entrepreneurial orientation of the STEM students and internal business environment of the STM students. It also discussed the effects of entrepreneurial orientation, external business environment and background characteristics on the entrepreneurial intention of the STEM students.

4.1 Background characteristics of the STEM students

In line with the literature, the number of male students in the STEM field was approximately double that of their female counterparts (Table 1) because males in developing countries dominate this field. It is not very clear if this underlying factor is gender-based or merely coincidental. The low enrolment of females in the STEM faculties can be attributed to several factors. STEM studies have traditionally been viewed as more appropriate for men than women (Maltese & Tai, 2011; Starobin et al., 2016). Most STEM students fall within the age range of 21 to 40 years and below 20 years (Table 1). These age groups represent the most intellectually productive periods during which the students experiment with life.

4.2 Entrepreneurial intentions of the STEM students

The entrepreneurial intentions of the STEM students were captured using different variables. These variables included: 'starting a business after graduation, 'intention to protect an invention from academic research, intended to commercialize research outputs,' and 'intention to start up a business from academic research. While these four variables may truly serve as a measure of the entrepreneurial intention of the STEM students, the study posits that the variable 'Do you intend to start up a business from your research?' was probably the most effective indicator to measure the intrapreneurial intentions of the students. Based upon Table 2, it was found that the majority of the STEM students have entrepreneurial intentions. For instance, seven out of every ten showed their desire for either starting a business after graduation, planning to start up a business from their research, have intentions of protecting their research inventions and/or commercializing their research output.

4.3 Entrepreneurial orientation motivating the entrepreneurial intentions of the STEM students

Table 3 reflects the entrepreneurial orientation of the students. On average, the students agree that having self-confidence, being committed to completing a task, liking their personal decisions, being inclined towards using new technologies, having a propensity for searching for new opportunities, and being creative represent their greatest attributes in terms of entrepreneurial orientation. Other advantages that they seem to have been managerial abilities, being proactive and having extensive networks of friends and colleagues, exploring new opportunities, being resilient and predispositioned towards exploring uncertain environments, as can be seen in Table 3.

4.4 External business environment motivating entrepreneurial intentions of the STEM students

The external business environment is viewed in two broad categories: exposure to entrepreneurship education and availability of entrepreneurship infrastructure.

4.4.1 Exposure to entrepreneurship education

Table 4 shows that the STEM students have poor exposure to entrepreneurship education and training. The reviewed literature tells us that exposure to entrepreneurship education is closely associated with entrepreneurship intention (Gerba, 2012; Hattab, 2014; Fayolle & Gailly, 2015; Rauch & Hulsink, 2015; Walter & Block, 2016; Jegede & Nieuwenhuizen, 2020a). While Oosterbeek et al. (2010) found that entrepreneurial training had no significant effect on students' entrepreneurial intentions, the study by Gerba (2012) indicated that students who had undergone entrepreneurship education leaned towards having more excellent entrepreneurial intentions than those who had not. Table 4 further discloses that less than half of the STEM students have been formally exposed to entrepreneurship education, either by taking a module on entrepreneurship at university or attending any seminar/workshops on entrepreneurship inside or outside the university. In like manner, less than half of the STEM students have been informally exposed to entrepreneurship education. The 40 percent who were informally exposed to this type of education had done so unintentionally, either because they are members of families that run businesses or live with a partner or friend who operates a business.

4.4.2 Availability of entrepreneurship infrastructure

According to reviewed literature, the technical support available from government, industry, and academia to startups and entrepreneurs is known as the entrepreneurial ecosystem. One of the best definitions of the entrepreneurial ecosystem is given by Stam (2015:1765) as "a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship" and by Roundy et al. (2017:99) as "communities of agents, social structures, institutions and cultural values that produce entrepreneurial activity." From Table 5, it is evident that the necessary infrastructural support for entrepreneurship is grossly inadequate. For instance, only 8.8 percent of the STEM students have bursaries or scholarships to support their research. Only one out of every five has access to research facilities such as laboratories or workshops. Only one out of every ten has access to an incubator to support their research. While only one out of every twenty has access to and/or connections or collaboration with industry. Jegede and Nieuwenhuizen (2020b) posited that entrepreneurship infrastructure available to researchers and students in Nigerian universities needs to be assessed and strengthened. Their study found that the support facilities available to university staff and students were not operating optimally because they were underfunded, coupled with an erratic supply of electricity to those facilities.

4.5 Effects of background characteristics, entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial infrastructure on entrepreneurial intentions of the STEM students

Partial regression was used to test the impact of the explanatory variables on the outcome variable. From Table 6, the students' background characteristics, entrepreneurial orientation and external business environment of the STEM students were regressed against the students' intentions to start up a business from their research.

In Equation I, none of the variables capturing background factors (gender, age, and educational qualifications) significantly impact entrepreneurial intentions. Despite the insignificant influence of background characteristics of the STEM students on their entrepreneurial intentions, gender tends to show a positive relationship with this variable, i.e., being male is associated with being entrepreneurial. This is because the odds ratio of the variable "gender" is above 1 (Table 6). An odd ratio of 1.59 associated with gender connotes that as the gender of the students' changes from female to male, they become 1.59 times (or 159 percent) likely to develop entrepreneurial intention. With an odds ratio of less than 1, age and educational qualifications were negatively associated with entrepreneurial intention, indicating that the older the students are, they become 0.57 times (or 57 percent) likely to develop entrepreneurial intention. The same applies for their level of education. The higher the degrees they have, they become 0.91 times (or 91 percent) likely to develop entrepreneurial intention. The Nagelkerke R Square value of 0.033 implies that the explanatory variables (age, gender, and educational qualifications) only accounted for around 3.3 percent of the variance in their entrepreneurial intentions.

In equation II, explanatory variables representing entrepreneurial orientation were regressed against the students' intention to start up a business from their research. Almost all the variables of entrepreneurial orientation have positive relationships with entrepreneurial intention among the STEM students. Of all the twelves variables, only the variable "I like to search for new opportunities" has a significant impact on entrepreneurial intention. This finding implies that with a unit increase in the students' search for new opportunities, they are 2.5 times more likely to develop entrepreneurial intention. Equation II with a Nagelkerke R Square value of 0.224, suggests that the variables representing entrepreneurial orientation explains only 22.4 percent of the variance in the entrepreneurial intentions of the STEM students.

In equation III, the explanatory variables representing the external business environment (access to entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship infrastructure) were regressed against the students' intention to start up a business from their research. The variables used to capture the external business environment (access to entrepreneurship education and support for entrepreneurship) mostly positively correlate with entrepreneurial intention. However, only the variable "Have you participated in any entrepreneurship training" seems to significantly influence their entrepreneurial intentions. The regression result shows that once the STEM students have participated in entrepreneurship training, they become 2.7 times more likely to develop their intention to start up a business from their research. The Nagelkerke R Square value of 0.11, implies that the explanatory variables (access to entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship infrastructure) explain only 11 percent of the variance in entrepreneurial intention (intention of students to start up a business from their research).

Equation IV shows the regression outcome of the combined explanatory variables on entrepreneurial intention. Gender shows a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention, i.e., being male was positively associated with being interested in starting a business from their research among the students. Also, the external business environment of the STEM students seems to have a more significant influence on entrepreneurial intention than entrepreneurial orientation. Six out of the seven variables capturing external business environment (exposure to entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship infrastructure) have positive relationships with entrepreneurial intentions, while only six out of twelve variables explaining entrepreneurial orientation have positive relationships with entrepreneurial intention. More specifically, only the variable "Have you participated in any entrepreneurship training" has a significant positive impact on the entrepreneurial intentions of the STEM students when all the explanatory variables are combined. This finding indicates that when the students are exposed to entrepreneurial training (workshops, seminars, short courses, etc.), they become 6.5 times more likely to develop an interest in starting a business from their research. According to Equation IV, the background characteristics, entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial education, and entrepreneurial infrastructure explain only 48.4 percent of the variance in the dependent variable (entrepreneurial intention). For equations 1 to 4, the Hosmer and Lemeshow Test conducted on all four equations shows a probability value greater than 0.05. This figure indicates that all four equations were good models and that there was no misspecification in the model's predictive capacity.

5. CONCLUSION

This study has advanced the importance of entrepreneurship training for STEM students. The findings of the study showed that entrepreneurship training has a transformative effect on STEM researchers. Entrepreneurship training helps STEM students develop the necessary entrepreneurial orientation to enable them to become entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship training focuses on developing real-life skills that will help STEM students to become creative and entrepreneurial in their careers. Generally, the content of entrepreneurial training includes learning how to collaborate to achieve one's goal, how to carry out advocacy effectively and efficiently, how to unravel real-life multifaceted problems that do not have a conclusive answer, and how to use inquisitiveness and imagination to find an innovative approach to solving life's complex problems. When the STEM students are exposed to these possibilities, they will begin to develop an orientation towards entrepreneurship, and many will most likely dare to become entrepreneurs. Indeed, the findings of the study indicate that entrepreneurs are developed through training.

The present study also exposed the importance of entrepreneurship infrastructure (incubators, central technical workshops & laboratories, and technology transfer offices) to encourage and strengthen entrepreneurship intention among STEM students. Though not operating optimally in the chosen Nigerian university, these facilities serve as practical teaching sources that complement entrepreneurship training (from Business Schools) from which the STEM students acquire their commercial knowledge and practical skills. The simultaneous exposure of the STEM students to theoretical knowledge and practical knowledge creates an environment in which students can help each other combine their research outputs, special skills, and capabilities into starting a new business.

6. IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY

This section discusses the implications of the study under three categories: policymaking, practice, and theory.

6.1 Implications for policymaking

Entrepreneurship education equips students with crucial life skills that will help them navigate the uncertain future. During entrepreneurship training, students acquire skills for identifying and solving problems, teamwork, and learning to accept failure as a part of the growth process. They also learn to collaborate to achieve their goals creatively. Entrepreneurship education entails training students to use new knowledge and skills to solve problems and create wealth. Hence, entrepreneurship education should become a compulsory module for STEM students. Furthermore, these students should be encouraged to have an entrepreneurial focus when deciding on their final year thesis topic. Universities must also encourage and support STEM students by assisting them to take their research outputs forward to protect and commercialize their inventions.

6.2 Implications for STEM students

Globally entrepreneurship is becoming increasingly important in universities' missions. Business schools and entrepreneurship modules are no longer the only channels for learning entrepreneurship in university settings. Effective entrepreneurial learning can also occur through science parks, incubators, workshops, laboratories, and technology transfer offices. Relevant academic literature has associated technology transfer and academic spin-offs from science parks, university technology transfer offices, and incubators with job creation, wealth creation, and local economic growth. STEM students must be encouraged to take advantage of the entrepreneurship facilities available to them while studying and conducting their subject-specific research at their universities.

6.3 Implications for scholars

The study showed that the informal channel of entrepreneurship education was the most important driver of entrepreneurship education among researchers in the STEM field. The non-formal channel involves undergoing such a form of entrepreneurship training like seminars, workshops, conferences, etc. The formal channel, taking entrepreneurship modules or degrees such as MBA at the university, also had a positive relationship with entrepreneurship intentions among the STEM students. The study has shown that these two channels have more impact on informal entrepreneurship education (spontaneous exposure to entrepreneurship education) in the buildup of entrepreneurial interest among STEM students. Indeed, the present study adds to the body of literature that posits that entrepreneurs are made (via necessary training).

7. LIMITATIONS AND DIRECTION FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The sample was conducted on one hundred and fifty students in Science and Engineering Faculties in one university in one country. While the study has provided beneficial information on what drives entrepreneurial intentions, further studies need to be conducted in more than one university and in more than one country to confirm or rebuff the trend recorded in the present study.

REFERENCES

Abdul-Mohsin, A. M., Abdul-Halim, H., & Ahmad, N. H. 2012. Delving into the Issues of Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation and Market Orientation among the SMEs-A Conceptual Paper. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, (65):731-736. [Internet: https://cyberleninka.org/article/n/962007, download on 28 October 2021]. [ Links ]

Abodunde, O.O., Jegede, O.O. & Oyebisi, T.O. 2020. A Longitudinal Assessment of Nigeria's Research Output for Evidence-Based Science Policy Development. International Journal of Big Data Management, 1(2):135-141. [https://doi:10.1504/IJBDM.2020.10030653]. [ Links ]

Abodunde, O.O.& Jegede, O.O. 2020. R&D Productivity for Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy Development in Nigeria: a Scientometric Analysis of Academic Literature. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 12 (7):787 - 795. [https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2020.1718364]. [ Links ]

Achchuthan, S. & Kandaiya, S. 2013. Entrepreneurial intention among undergraduates: review of literature. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(5):172-186 [Internet: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/EJBM/article/view/4566, downloaded on 17 January 2021]. [ Links ]

Agbonlahor, A.A. 2016. Challenges of entrepreneurial education in Nigerian universities: towards a repositioning for impact. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 6(1):208-208. [https://doi.org/10.5901/jesr.2016.v6n1p208]. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. 1991. Theories of cognitive self-regulation the theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2):179-211. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T]. [ Links ]

Al-Jabari, I., Hassan, A. & Hashim, J. 2017. The role of autonomy as a predictor of entrepreneurial intention among university students in Yemen. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 30(3): 325340. [https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2017.081950]. [ Links ]

Al-Jubari, I., Hassan, A. & Liñán, F. 2019. Entrepreneurial intention among university students in Malaysia: integrating self-determination theory and the theory of planned behavior. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(4):1323-1342. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-018-0529-0]. [ Links ]

Allini, A., Ferri, L., Maffei, M. & Zampella, A. 2017. The effect of perceived corruption on entrepreneurial intention: evidence from Italy. International Business Research, 10(6):75-86. [https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v10n6p75]. [ Links ]

Al Mamun, A., Kumar, N., Ibrahim, M.D. & Bin, M.N.H. 2017. Validating the measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Economics & Sociology, 10(4):51-66. [https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2017/10-4/5]. [ Links ]

Ambroziak, A.A. & Hartwell, C.A. 2018. The impact of investments in special economic zones on regional development: the case of Poland. Regional Studies, 52(10):1322-1331. [https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1395005]. [ Links ]

Antonioli, D., Nicolli, F., Ramaciotti, L. & Rizzo, U. 2016. The effect of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations on academics' entrepreneurial intention. Administrative Sciences, 6(4):15 - 27. [https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci6040015]. [ Links ]

Audretsch, D.B. & Belitski, M. 2019. Science parks and business incubation in the United Kingdom: Evidence from university spin-offs and staff startups. In Amoroso,S., Link, A.N.& Wright, M. (eds). Science and technology parks and regional economic development. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30963-37]. [ Links ]

Bandura, A. 1977. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2):191 -215. [https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191]. [ Links ]

Bandura, A. 1989. Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9):1175-1184. [https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175]. [ Links ]

Bandura, A. 1997. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York :W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co. [ Links ]

Bandura, A. & McClelland, D.C. 1977. Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Barba-Sánchez, V. & Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. 2018. Entrepreneurial intention among engineering students: The role of entrepreneurship education. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 24(1):53-61. [https://doi.org/10.1016/uedeen.2017.04.001]. [ Links ]

Barbosa, S.D., Gerhardt, M.W. & Kickul, J.R. 2007. The role of cognitive style and risk preference on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 13(4):86-104. [https://doi.org/10.1177/10717919070130041001]. [ Links ]

Bergmann, H., Hundt, C. & Sternberg, R. 2016 What makes student entrepreneurs? On the relevance (and irrelevance) of the university and the regional context for student startups. Small Business Economics, 47(1):53-76. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9700-6]. [ Links ]

Bischoff, K., Volkmann, C.K., & Audretsch, D.B. 2018. Stakeholder collaboration in entrepreneurship education: An analysis of the entrepreneurial ecosystems of European higher educational institutions. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(1):20-46. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9581-0]. [ Links ]

Blume-Kohout, M.E. 2016. Why are some foreign-born workers more entrepreneurial than others? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(6):1327-1353. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-015-9438-3]. [ Links ]

Breznitz, S.M. & Zhang, Q. 2019. Fostering the growth of student startups from university accelerators: an entrepreneurial ecosystem perspective. Industrial and Corporate Change, 28(4): 855-873. [https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtz033]. [ Links ]

Byun, C.G., Sung, C.S., Park, J.Y. & Choi, D.S. 2018. A study on the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education programs in higher education institutions: A case study of Korean graduate programs. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market and Complexity, 4(3):26-42. [https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4030026]. [ Links ]

Colombo, M. G. & Piva, E. 2020. Startups launched by recent STEM university graduates: The impact of university education on entrepreneurial entry. Research Policy, 49(6):103993. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.103993]. [ Links ]

Da Cruz, M.D.F.P., Ferreira, J.J. & Kraus, S., 2021. Entrepreneurial orientation at higher education institutions: State-of-the-art and future directions. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(2):100502. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100502]. [ Links ]

Davis F.D., Bagozzi, RP & Warshaw P.R. 1992. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22(14):1111-1132. [https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb00945.x]. [ Links ]

Day, R. & Allen, T.D. 2004. The relationship between career motivation and self-efficacy with protégé career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1):72-91. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00036-8]. [ Links ]

Delanoë-Gueguen, S. & Liñán, F. 2019. A longitudinal analysis of the influence of career motivations on entrepreneurial intention and action. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration, 36(4):527-543. [https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1515]. [ Links ]

Erhardt, K. & Haenni, S. 2018. Born to be an entrepreneur? How cultural origin affects entrepreneurship. University of Zurich, Department of Economics, Working Paper, (309). [https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3300087]. [ Links ]

Farrukh, M., Khan, A.A., Khan, M.S., Ramzani, S R. & Soladoye, B.S.A. 2017. Entrepreneurial intentions: the role of family factors, personality traits, and self-efficacy. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development. 13(4):303-317. [https://doi.org/10.1108/WJEMSD-03-2017-0018]. [ Links ]

Fayolle, A. & Gailly, B. 2015. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1):75-93. [https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12065]. [ Links ]

Fayolle, A., Liñán, F. & Moriano, J.A. 2014. Beyond entrepreneurial intentions: values and motivations in entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(4):679-689. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0306-7]. [ Links ]

Ferreira, J.J., Fernandes, C.I. & Kraus, S. 2019. Entrepreneurship research: mapping intellectual structures and research trends. Review of Managerial Science, 13(1):181-205. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0242-3]. [ Links ]

Fitzsimmons, J.R. & Douglas, E.J. 2011. Interaction between feasibility and desirability in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4):431-440. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.01.001]. [ Links ]

Forbes, D.P. 2017. "Born, Not Made" and Other Beliefs About Entrepreneurial Ability. In The Wiley Handbook of Entrepreneurship (pp. 273-391). Minnesota, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118970812.ch13]. [ Links ]

Gerba, D.T. 2012. Impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students in Ethiopia. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 3(2):277-301. [https://doi.org/10.1108/20400701211265036]. [ Links ]

Gillespie, E.A., Noble, S.M. &am, S.K. 2016. Extrinsic versus intrinsic approaches to managing a multi-brand salesforce: when and how do they work?. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(6): 707-725. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0473-x]. [ Links ]

Gu, J., Hu, L., Wu, J. & Lado, A.A. 2017. Risk propensity, self-regulation, and entrepreneurial intention: empirical evidence from China. Current Psychology, 37(3):648-660. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9547-7]. [ Links ]

Guerrero, M., Rialp, J. & Urbano, D. 2008. The impact of desirability and feasibility on entrepreneurial intentions: a structural equation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(1):35-50. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-006-0032-x]. [ Links ]

Guerrero, M., Urbano, D., Cunningham, J.A. & Gajón, E. 2018. Determinants of Graduates' Start-Ups Creation across a Multi-Campus Entrepreneurial University: The Case of Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(1):150-178. [https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12366]. [ Links ]

Gurel, E., Altinay, L. & Daniele, R. 2010. Tourism students' entrepreneurial intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3):646-669. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.12.003]. [ Links ]

Hadjimanolis, A. 2016. Perceptions of the institutional environment and entrepreneurial intentions in a small peripheral country. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 28(1):20-35. [https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2016.075680]. [ Links ]

Hao, Z., Scott, E.S. & Gerald, E.H. 2005. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6):1265-1272. [https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1265]. [ Links ]

Harmsen, H.W. 2018. New business partner search, find and selection in small high-tech companies: an entrepreneur and managers' perspective (Master's thesis, University of Twente). [ Links ]

Hattab, H.W. 2014. Impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Egypt. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 23(1):18-31. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0971355713513346]. [ Links ]

Hernández-Perlines, F., Ibarra Cisneros, M.A., Ribeiro-Soriano, D. & Mogorrón-Guerrero, H. 2020. Innovativeness as a determinant of entrepreneurial orientation: analysis of the hotel sector. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 33(1):2305-2321. [https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1696696]. [ Links ]

Hoppe, M. 2016. Policy and entrepreneurship education. Small Business Economics, 46(1):13-29. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9676-7]. [ Links ]

Ibrahim, N. & Mas'ud, A. 2016. Moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation on the relationship between entrepreneurial skills, environmental factors and entrepreneurial intention: A PLS approach. Management Science Letters, 6(3):225-236. [https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2016.1.005]. [ Links ]

Israr, M. & Saleem, M. 2018. Entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Italy. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8(1):1-20. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0107-5]. [ Links ]

Jakubiak, M. 2020. Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intentions in Relation to Students of Management. Expanding Horizons: Business, Management and Technology for Better Society, 371-371. [Internet: https://ideas.repec.org/h/tkp/mklp20/371.html, downloaded on 5 January 2021]. [ Links ]

Jegede, O.O. & Nieuwenhuizen, C. 2020a. Factors Influencing Business Start-Ups Based on Academic Research. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(S1): 1-22. [Internet: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/Factors-Influencing-Business-1528-2651-23-S1-657.pdf, downloaded on 17 December 2020]. [ Links ]

Jegede, O.O & Nieuwenhuizen, C. 2020b. Assessing the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem of Science, Technology Engineering and Mathematics Researchers in Nigeria. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25 (1): 119. [Internet: https://www.abacademies.org/abstract/assessing-the-entrepreneurial-ecosystem-of-science-technology-engineering-and-mathematics-stem-researchers-in-nigeria-9997.html, downloaded on 22 January 2021]. [ Links ]

Jegede, O.O, Jegede, O.E. & Mustapha, M. 2020a. Informal Sector Measurement of Openness, Collaboration and Innovation in Africa: The case of Otigba Hardware Microenterprises Cluster in Africa. In: Mammo Muchie and Angathever Baskaran (eds). Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators: Lessons from Development Experience in Africa. Africa World Press, New Jersey, USA. [ Links ]

Jegede, O.O., Oluwale, B.A., Ogunjemiluia, E.M. & Ajao, B.F. 2020b. From Startup to Scale-up: Indicators showing the role of knowledge sharing in Clustered Microenterprises in Nigeria In: Mammo Muchie and Angathever Baskaran (eds). Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators: Lessons from development experience in Africa. Africa World Press,New Jersey, USA. [ Links ]

Kakouris, A., & Georgiadis, P. 2016. Analysing entrepreneurship education: a bibliometric survey pattern. Journal of global entrepreneurship research, 6(1):6-15. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0046-y]. [ Links ]

Kasser, T. & Ryan, R.M. 1996. Further examining the American dream: differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(3):280-287. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296223006]. [ Links ]

Kirkley, W.W. 2017. Cultivating entrepreneurial behaviour: entrepreneurship education in secondary schools. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship. 11(1):17-37. [https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-04-2017-018]. [ Links ]

Koe, W.L. 2016. The relationship between Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation (IEO) and entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6(1):1-11. [https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0057-8]. [ Links ]

Light, P.C. 2006. Reshaping social entrepreneurship. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 4(3):47-51. [Internet: https://wagner.nyu.edu/files/performance/ReshapingSE.pdf, downloaded on 28 October 2021]. [ Links ]

Lerner, J. & Malmendier, U. 2013. With a little help from my (random) friends: Success and failure in post-business school entrepreneurship. The Review of Financial Studies, 26(10):2411-2452. [https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hht024]. [ Links ]

Linton, G. & Kask, J. 2017. Configurations of entrepreneurial orientation and competitive strategy for high performance. Journal of Business Research, 70:168-176. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.022]. [ Links ]

Liu, W., Shi, H.B., Zhang, Z., Tsai, S.B., Zhai, Y., Chen, Q. & Wang, J. 2018. The development evaluation of economic zones in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1):56-74. [https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010056]. [ Links ]

Ma, L., & Zhou, X. 2017. The Interactive Mode of Emerging Industry Cluster and Entrepreneurial Talent Incubation: A Doule Helix Model. Management & Engineering, (28):49-57. [Internet: https://www.proquest.com/openview/5b289a300a242fcfb572ed3559d2dd04/17pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2028702. Accessed 31 January 2021]. [ Links ]

Mahendra, A.M., Djatmika, E.T. & Hermawan, A. 2017. The Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Intentions Mediated by Motivation and Attitude among Management Students, State University of Malang, Indonesia. International Education Studies, 10(9):61-69. [https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v10n9p61]. [ Links ]

Maltese, A.V., & Tai, R.H. 2011. Pipeline persistence: Examining the association of educational experiences with earned degrees in STEM among US students. Science Education, 95(5): 877-907. [https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20441]. [ Links ]

Martin, B.C., McNally, J.J., & Kay, M.J. 2013. Examining the formation of human capital in post-business school entrepreneurship. Review of Financial Studies, 26: 2411-2452. [Internet: https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/ibvent/v28y2013i2p211-224.html, downloaded on 6 January 2021]. [ Links ]

McClelland, D.C. 1985. How motives, skills, and values determine what people do. American Psychologist, 40(7): 812-831. [https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.40.7.812]. [ Links ]

McClelland, D.C. 1988. Human motivation. CUP Archive. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139878289]. [ Links ]

Meyer, D.F. & Meyer, N. 2020. The relationships between entrepreneurial factors and economic growth and development: The case of selected European countries. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 21(2):268-284. [https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2020.21.2.19]. [ Links ]

Mian, S., Lamine, W. & Fayolle, A. 2016. Technology Business Incubation: An overview of the state of knowledge. Technovation, 50: 1-12. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2016.02.005]. [ Links ]

Muñoz, P. & Cohen, B. 2018. Sustainable entrepreneurship research: Taking stock and looking ahead. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(3):300-322. [https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2000]. [ Links ]

Narula, R. & Zhan, J. 2019. Using special economic zones to facilitate development: policy implications. Transnational Corporations Journal, 26(2):1-25 [https://doi.org/10.18356/72e19b3c-en]. [ Links ]

Neck, HM & Corbett, A.C. 2018. The scholarship of teaching and learning entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 1(1):8-41. [https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127417737286]. [ Links ]

Newman, C. & Page, J.M. 2017. Industrial clusters: The case for special economic zones in Africa (No. 2017/15). WIDER Working Paper. [https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2017/239-7]. [ Links ]

Nicholls-Nixon, C.L., Valliere, D., Gedeon, S.A. & Wise, S. 2020. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and the lifecycle of university business incubators: An integrative case study. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(2):809-837. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00622-4]. [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuizen, C. 2016. Entrepreneurial intentions amongst Master of Business students in efficiency-driven economies: South Africa and Poland. Southern African Business Review, 20(1):313-335. [https://doi.org/10.25159/1998-8125/6054]. [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuizen, C., Groenewald D., Davids J., Janse van Rensburg, L. & Schachtebeck, C. 2016. Best practice in entrepreneurship education. Problems and Perspectives in Management. 14(3):528-537. [https://doi:10.21511/ppm.14(3-2).2016.09]. [ Links ]

Núñez-Pomar, J., Prado-Gascó, V., Sanz, V.A., Hervás, J.C., & Moreno, F.C. 2016. Does size matter? Entrepreneurial orientation and performance in Spanish sports firms. Journal of Business Research, 69(11): 5336-5341. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.134]. [ Links ]

Ogunjemilua E.M., Oluwale B.A., Jegede O.O., Ajao B.F. 2020. The Nexus of Knowledge Sharing and Innovations in the Informal Sector: The Case of Otigba Hardware Cluster in Nigeria. In: Larimo J., Marinov M., Marinova S., Leposky T. (eds). International Business and Emerging Economy Firms. Palgrave Studies of Internationalization in Emerging Markets. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. pp 275-299. [https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27285-29]. [ Links ]

Oosterbeek, H., Van Praag, M. & Ijsselstein, A. 2010, The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. European Economic Review, 54(3):442-454. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.08.002]. [ Links ]

Parry, M. 2018. The Future of Science Parks and Areas of Innovation: Science and Technology Parks Shaping the Future. World Technopolis Review, 7(1):44-58. [Internet: http://kpubs.org/article/articleMain.kpubs?articleANo=SGGHBZ2018v7n144; downloaded on 7 January 2021]. [ Links ]

Ramchander, M. 2019. Reconceptualising undergraduate entrepreneurship education at traditional South African universities. Acta Commercii, 19(2):1-9. [https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v19i2.644]. [ Links ]

Randerson, K. 2016. Entrepreneurial orientation: do we actually know as much as we think we do?. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 28(7-8):580-600. [https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2016.1221230]. [ Links ]

Rauch, A. & Helsinki, W. 2015. Putting entrepreneurship education where the intention to act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(2):187-204. [https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0293]. [ Links ]

RezaeiZadeh, M., Hogan, M., O'Reilly, J., Cunningham, J. & Murphy, E. 2017. Core entrepreneurial competencies and their interdependencies: Insights from a study of Irish and Iranian entrepreneurs, university students and academics. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(1):35-73. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0390-y]. [ Links ]

Roundy, P.T., Brockman, B.K. & Bradshaw, M. 2017. The resilience of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8; 99-104. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2017.08.002]. [ Links ]

Schachtebeck, C., Groenewald, D. & Nieuwenhuizen, C. 2019. Intrapreneurial orientation in small and medium-sized enterprises: An exploration at the employee level. Acta Commercii, 19(2):1-13. [https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v19i2.638]. [ Links ]

Segal, G., Borgia, D. & Schoenfeld, J. 2005. The motivation to become an entrepreneur. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. 11(1): 42-57. [https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550510580834]. [ Links ]

Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O. & Bogatyreva, K. 2016. Exploring the intention-behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. European Management Journal, 34(4):386-399. [https://doi.org/10.1016/_i.emj.2015.12.007]. [ Links ]

Siyanbola, W.O., Afolabi, O.O., Jesuleye, O.A., Egbetokun, A.A., Dada, A.D., Aderemi, H.O. & Rasaq, M.A. 2012. Determinants of entrepreneurial propensity of Nigerian undergraduates: an empirical assessment. International Journal of Business Environment, 5(1): 1-29. [https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBE.2012.044925]. [ Links ]

Siyanbola, W.O., Isola, O.O., Egbetokun, A.A. & Adelowo, C.M. 2011. R & D and the Challenge of Wealth Creation in Nigeria. Asian Research Policy, 2(1): 20-35. [Internet: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235940492_RD_and_the_Challenge_of_Wealth_Creation_in_Nigeria; downloaded on15 December 2020]. [ Links ]

Smith, C.P., Atkinson, J.W., McClelland, D.C., & Veroff, J. (Eds.). 1992. Motivation and Personality: Handbook of Thematic Content Analysis. UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Sosnovskikh, S. 2017. Industrial clusters in Russia: The development of special economic zones and industrial parks. Russian Journal of Economics, 3(2):174-199. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ruje.2017.06.004]. [ Links ]

Stam, E. 2015. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: a sympathetic critique. European Planning Studi'es,23(9): 1759-1769. [https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484]. [ Links ]

Starobin, S.S., Smith, D.J. & Santos Laanan, F. 2016. Deconstructing the transfer student capital: Intersect between cultural and social capital among female transfer students in STEM fields. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 40(12):1040-1057. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2016.1204964]. [ Links ]

Syam, A., Akib, H., Yunus, M. & Hasbiah, S. 2018. Determinants of entrepreneurship motivation for students at educational institution and education personnel in Indonesia. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 21(2):1-12. [Internet: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/determinants-of-entrepreneurship-motivation-for-students-at-educational-institution-and-education-personnel-in-indonesia-7173.html; downloaded on13 December 2020]. [ Links ]

Torres, F.C., Méndez, J.C.E., Barreto, K.S., Chavarría, A.P., Machuca, K.J. & Guerrero, J.A.O. 2017. Exploring entrepreneurial intentions in Latin American university students. International Journal of Psychological Research, 10(2):46-59. [https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.2794]. [ Links ]

Tsai, K.H., Chang, H.C. & Peng, C.Y. 2016. Extending the link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: a moderated mediation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2): 445-463. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0351-2]. [ Links ]

van der Zwan, P., Thurik, R., Verheul, I. & Hessels, J. 2016. Factors influencing the entrepreneurial engagement of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. Eurasian Business Review, 6(3):273-295. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-016-0065-1]. [ Links ]

Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W. & Deci, E.L. 2006. Intrinsic versus extrinsic goal contents in self-determination theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41(1):19-31. [https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep41014]. [ Links ]

Wales, W.J. 2016. Entrepreneurial orientation: A review and synthesis of promising research directions. International Small Business Journal, 34(1):3-15. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615613840]. [ Links ]

Walter, S.G. & Block, J.H. 2016. Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2):216-233. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.10.003]. [ Links ]

Wright, M., Siegel, D.S. & Mustar, P. 2017. An emerging ecosystem for student startups. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(4): 909-922. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9558-z]. [ Links ]

Xie, K., Song, Y., Zhang, W., Hao, J., Liu, Z. & Chen, Y. 2018. Technological entrepreneurship in science parks: A case study of Wuan Donghu High-Tech Zone. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 135:156168. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.01.021]. [ Links ]

Yaluner, E.V., Chesnova, O.A., Ivanov, S.A., Mikheeva, D.G. & Kalugina, Y.A. 2019. Entrepreneurship development: technology, structure, innovations. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering, 8(2):6020-6025. [https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.B3732.078219]. [ Links ]

Yi, S. & Duval-Council, N. 2018. What drives engineering students to be entrepreneurs? Evidence of validity for an entrepreneurial motivation scale. Journal of Engineering Education, 107(2):291-317. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20199]. [ Links ]

Yildirim, N., Çakir, Ö. & Askun, O.B. (2016). Ready to dare? A case study on the entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students in Turkey. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 229:277-288. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.138]. [ Links ]

Yunis, M., Tarhini, A. & Kassar, A. 2018. The role of ICT and innovation in enhancing organizational performance: The catalysing effect of corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 88:344-356. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.030]. [ Links ]

Zhao, H., Seibert, S.E. & Lumpkin, G.T. 2010. The relationship of personality to entrepreneurial intentions and performance: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36(2):381-404. [https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309335187]. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author