Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.12 no.1 Meyerton 2015

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Tourists' view of the factors that gives the Kruger National Park a competitive edge

WH EngelbrechtI, *; M KrugerII; M SaaymanIII

ITREES (Tourism, Research in Economic Environs and Society), North-West University wengelbrecht@iie.ac.za

IITREES (Tourism, Research in Economic Environs and Society), North-West University martinette.kruger@nwu.ac.za

IIITREES (Tourism, Research in Economic Environs and Society), North-West University Melville.saayman@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The tourism industry is becoming more competitive by the day; in order to remain competitive, it is of paramount importance that competitive advantage factors be identified by tourism destinations such as national parks. The purpose of this research was to determine the said factors of South Africa's flagship national park: the Kruger National Park. To achieve this, a survey was conducted at this park in 2013 where 436 questionnaires were administered to overnight visitors at selected rest camps in its southern region. A factor analysis revealed five competitive advantage factors: Wildlife Experiences, Marketing and Branding, Accommodation and Retail, Visitor Management and Suprastructure and Amenities. The Kruger National Park's management can exploit these results to improve its current position as a competitive tourism destination. The competitive advantage factors that have been identified are distinctive for national parks, thereby contributing towards the body of knowledge on this topic. The competitive advantage factors could lead to an increase in product and service quality offered by the park and enhance the visitor's experience, therefore leading to increased visitor numbers to the park and higher income to have the park become more self-sufficient.

Key phrases: comparative advantage; competitive advantage, competitiveness, national parks, nature-based tourism; park management

1. INTRODUCTION

South African National Parks (SANParks) are confronted with the reality of generating their income mostly through tourism, as government funding is decreasing in real terms (Leal & Fretwell 1997:internet; Mabunda 2010:internet; Wade & Eagles 2003:196). Walls (2013:1) concurred, adding that since the 1990's funding for national parks has been on the decrease. Mabunda (2010:the internet) as well as Muhumuza and Balkwill (2013:13) made the same point in that the South African government has cut back on funding for SANParks over the years. This has led SANParks to generate its own income that results in approximately 80% being generated through tourism (Mabunda 2010:internet).

This is a major concern for SANParks, the national custodian of conservation, as greater efforts in protecting wildlife and plant species; increased marketing promotions; improvement and renovations of rest camps to meet tourist needs and expectations and the like are increasing their daily operational costs (Du Plessis, Van der Merwe & Saayman 2012:2912). Therefore, there is a need for SANParks to develop park specific attributes, products and services to increase tourist numbers and revenue, all whilst managing the Kruger National Park in a sustainable manner (Dwyer, Edwards, Mistilis, Roman & Scott 2009:63; Saayman 2009:358).

South Africa's national parks are regarded as major tourist attractions and major export earners, playing a significant role in the South African tourism industry. Adding to the problem of decreased funding is the stiff competition among nature-based tourism destinations in South Africa and globally. SANParks currently manages 22 national parks which compete with an estimated 9 000 privately-owned game farms and the 171 provincial parks and local nature reserves within South Africa (Bushell & Eagles 2007:33; Eagles 2002:133; Van der Merwe & Saayman 2008:154).

The Kruger National Park, one of the world's most renowned national parks and the third oldest national park in the world, covers a staggering 1 962 362 hectares (ha) of land, an area which is larger than Israel or Holland (Dieke 2001:99; Honey 1999:339). Situated on the north-eastern side of South Africa and bordering Mozambique and Zimbabwe, this Park is known as SANParks' flagship park, offering tourists a variety of species including: 336 tree types, 49 fish types, 34 amphibian types, 114 reptile types, 507 bird types and 147 different types of mammals (Aylward & Lutz 2003:97; Bushell & Eagles 2007:33; Van der Merwe & Saayman 2008:154). The Kruger National Park has offered a distinct, nature-based tourism experience for the past 116 years (Braack 2006:5 Loon, Herper & Shorten 2007:264; SANParks 2014:internet) with the majority of parks income earned through tourism-related activities.

The greater the improvements in service delivery and product offering are at a national park the more competitive the park may become (Hu & Wall 2005:622). Competitiveness has been researched within various disciplines, such as management, economics and marketing (Al-Masroori 2006; Chen, Chen & Lee 2011; Dwyer & Kim 2001). Based on the products/goods industries, competitiveness in the services industries is currently dominating the global economies. As a result, competitiveness within the latter industries is increasing; therefore the managements of tourism destinations should take note of this shift to remain competitive within the industry (Ritchie & Crouch 2003:18). It is necessary that tourism destination managers understand the importance of competitiveness and the ways in which it can be enhanced (Gomezelij & Michalic 2008:294).

It is suggested that a demand side analysis plays a vital role in determining the competitive advantage factors of a destination such as a national park. Due to the constant growth in the demand by tourists for natural attractions and activities, it is important that the Kruger National Park develops, identifies and implements competitive advantage factors that are distinct to the Park (Jurdana 2009:270).

Tourists travelling to the Kruger National Park are purchasing experiences and not necessarily products, because their behaviour and emotions, whilst interacting with nature, local community or personnel, determine the level of experience (Pedersen 2002:24; Ritchie & Crouch 2003:73). Therefore, the offering of a broad range of unique tourism-related products and services that is specific and exclusive to the Park, is required to satisfy the expectations and needs of tourists visiting there (Leberman & Holland 2005:22; Peake, Innes & Dyer 2009:107). It could be argued that tourists are more than willing to pay high prices in national parks if the quality of services and products is of a high standard (Buckley 2008:6; Komppula 2006:137; Kuo 2002:97).

Therefore, the aim of this research is to identify the competitive advantage factors that visitors to the Kruger National Park perceive as being important for achieving a competitive advantage position. To date, within the South African National Parks and to the best of this author's knowledge, this type of research has not yet been conducted. As it is essential for all national parks within the South African borders to remain competitive and sustainable as well as becoming independent from government funding, this research assists in that endeavour. It is anticipated that, by creating awareness of tourists' ever-changing expectations and needs when travelling to a national park, Kruger Park management can address this accordingly. The identification of competitive advantage factors offers the management an opportunity to identify distinct product and services areas where the quality of products and services can be improved.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature review investigates four areas: competitiveness; the difference between comparative and competitive advantage; competitiveness within a nature-based context as well as previous research on the topic.

2.1 Competitiveness

Porter (1985:1) who, within economics and business management, is regarded as the father of the study of competitiveness, indicated that the focus of competitiveness is clearly on the development of superior products and services which will place an organisation above its competitors (Huggins & Izushi 2011:5; Porter 2008:xv; Ritchie & Crouch 2003:2).

Armenski, Gomezelj, Djurdjev, Deri and Aleksandra (2011:19) and Grant (2008:205) explain that competitiveness occurs when two or more organisations target the same market segment, offer the same products and services, but one organisation shows a higher profit margin than that of its competitor(s).

In addition, competitiveness may be regarded as presenting superior and unique products and/or services which the competitor cannot duplicate and which attract consumers to the same destination, product or service provider year after year (Armenski et al. 2011:19; Cracolici & Njikamp 2008:336; Crouch 2010:27; Thompson & Martin 2010:785). In the instance of the national parks such as the given Park, competitiveness can only be achieved once the Park has obtained a competitive advantage and continues to maintain that advantage over its peers (Dwyer & Kim 2003:372; Middleton, Fyall & Morgan 2009:197).

The destination competitiveness framework developed by Ritchie and Crouch (2003:66-76) shifted the focus to a service-delivery oriented industry by identifying six tourist-related determinants, which include qualifying determinants, destinations' management, core resources and attractions as well as supporting factors and resources (Chen et al. 2011:249; Go & Govers 2000:82; Gomezelij & Michalic 2008:299).

Manzanec, Wöber and Zins (2007:46) as well as Ritchie and Crouch (2003:2) define a competitive tourist destination as a destination that has the ability to increase tourist expenditure, increase tourist numbers through a satisfactorily memorable experience, increase profitability, ensure that both environment and cultural conservation takes place and, most importantly, ensure the sustainability of the destination for future generations. Since the introduction of competitiveness to the field of tourism, research on the topic has emerged which includes the work of Asch and Wolf (2001); Buhalis (2000); Chen et al. (2011:249); Crouch and Ritchie (1994); Du Plessis (2002); Dwyer and Kim (2001); Dwyer, Livaic and Mellor (2003); Go and Groves (2000); Hassan (2000); Kozak (2001); Mihalic (2000) as well as Ritchie and Crouch (2003).

Competitiveness can be achieved when the competitive advantage factors and comparative factors of the destination have been identified and incorporated into its development and improvement (Ritchie & Crouch 2003:25). Gomezelij and Michalic (2008:294) elaborated on this, indicating that the competitive advantage factors should be implemented in conjunction with the tourism resources and management strategies that are supported by the relevant stakeholders.

Such factors could include aspects that address the attractiveness of a destination, availability of supporting infra- and supra- structures and possibilities of future development that might increase the profitability of the destination, ensuring its sustainability for future generations (Porter 1985:1; 2008:4). There is, however, a difference between competitive advantage and comparative advantage that needs to be taken into consideration.

2.2 Comparative advantage versus competitive advantage

The basic competitive advantage factors, such as natural and artificial resources, exercise a major influence on demand conditions such as market type, seasonality, brand awareness and the preferences of the consumers (Navickas & Malakauskaite 2009:38). Therefore, with the focus on national parks, tourists travelling to a national park seek an all-inclusive destination experience, which includes accommodation and catering, transportation, attractions and entertainment, most of which is offered by the majority of national parks (Page & Connell 2014:23; Ritchie & Crouch 2003:19; Van Wyk 2011:366).

In this regard, Ritchie and Crouch (2003:23) point out that competitive advantage is an organisation's ability to make use of the available comparative factors in such a way that the destination remains sustainable and profitable for the long-term. It is, therefore, important for organisations to compare products and services to determine whether or not the organisation still has a competitive advantage (Grant 2008:367).

Comparative advantage factors can be regarded as resources and factors that cannot be charged by any endogenous factor in the correspondent country's economic system (Hong 2008:54). Typical comparative factors include human resources, physical resources, knowledge resources, capital resources, infrastructure and tourism supra-structure, historical and cultural resources and the size of the economy as well as the growth and depletion of those resources which tourists would use when travelling to a destination (Mihalic 2000:77; Ritchie & Crouch 2003:20-22).

In the case of this specific Park under discussion, these factors might be used to sustain tourist numbers to obtain a competitive advantage as a tourism destination. However, a comparative advantage concerns the availability of natural resources at the destination. Thus, as national parks are established for the protection of biodiversity and natural heritage in a sustainable manner, comparative advantage is relevant (SANParks 2014:internet), if the Kruger National Park combines its products and services with the aim of becoming more competitive.

The implementation of these competitive advantage factors within the various divisions of the Parks is crucial to the success of achieving competitiveness. This would involve considering factors such as cost effectiveness, technology improvements, consumer satisfaction, effective marketing, distribution and consumer management (Thompson & Martin 2010:212).

2.3 Competitiveness within a nature-based and national park context

Competitiveness can only be realised once competitive advantage factors have been identified that can be managed in order to achieve a competitive market position within a particular sector or industry (Ambastha & Momaya 2004:45; Hong 2008:4). Competitiveness revolves around the prospective tourists' needs and wants and not necessarily around the further development of products or services that are already on offer (Middleton et al. 2009:197).

National park managers have to identify competitive advantage factors that are distinct and unique to each national park, which in turn would satisfy the expectations and needs of tourists. Whereas comparative advantage factors lead to the destination obtaining a competitive advantage, it is therefore vital that park management make clear distinctions between competitive and comparative factors (Dwyer & Kim 2003:372). In the case of park management neglecting these resources, this will have an impact on the competitive advantage of the park itself (Shirazi & Som 2011:77).

The competitiveness of a tourism destination, such as the Kruger National Park, is measured against the performance of multiple park functions. Therefore, the focus should be based on the three pillars of park management: general, ecotourism, and conservation management (Saayman 2009: 358; Scott & Lodge 1985:6). The focus of each pillar is linked to and based on the park's main policy of protecting and conserving the natural and cultural heritage of the Park. Chen et al. (2011:260) indicate that a tourism destination's specific, unique characteristics and attributes play the most important part in the development of a competitive advantage.

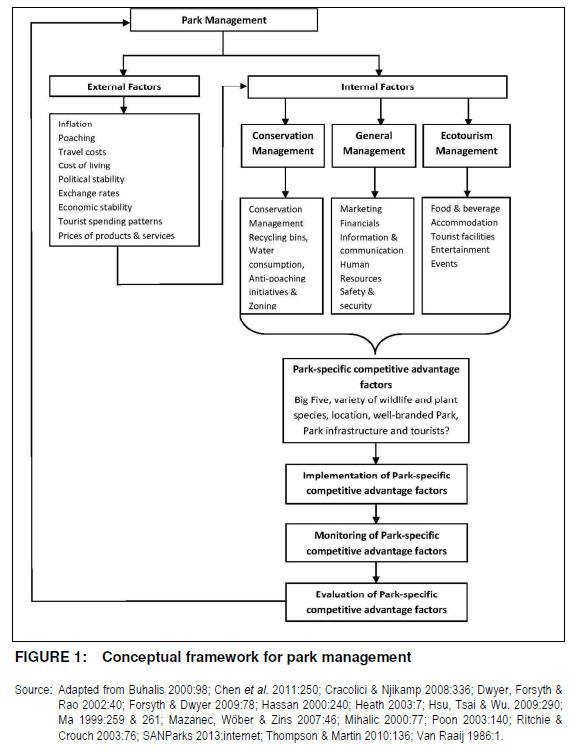

Figure 1 provides an overview of park management that consists of internal and external factors that should be implemented, monitored and evaluated.

Internal factors refer to aspects that park management can control. On the other hand, external factors include all aspects over which park management has no control. Both these factors affect the competitive advantage of the park (Hsu, Tsai & Wu 2009:290; Ritchie & Crouch 2003:68; SANParks 2014:internet; Van Raaij 1986:1). Nonetheless, park management should consider the external factors and incorporate them into the management function in order to develop the entire park as a competitive destination based on the changing demands of tourists (Hsu et al. 2009:290; Kotler, Haider & Rein 1993:623). If aspects such as reputation, information, intelligence, vision, financial assets, well-trained and skilled personnel are implemented, these may have a positive effect on the park's internal performance (Buhalis 2000:99; Mihalic 2000:77; Poon 2003:140).

Competitive advantage factors could also be determined by the identification of risks as this forms part of the managerial function. Risk identification could increase the competitive advantage of the park (Shaw, Saayman & Saayman 2012:191).

The implementation, constant monitoring and evaluation of the competitive advantage factors will consequently contribute to the successful positioning of the park to gain a competitive advantage over its peers (Ritchie & Crouch 2003:166; Thompson & Martin 2010:197; Wood 2004:151). Therefore, the attraction and natural resources are considered fundamental characteristics of the park that influence its competitive advantage (Chen et al. 2011:249).

Unfortunately, to date very little research has been performed on competitiveness within nature-based tourism destinations such as national parks, or ways in which a competitive advantage can be obtained for these destinations. Attention is drawn to this lack of research through the discussion on literature in the next section.

2.4 Previous research regarding competitiveness within a nature-based context

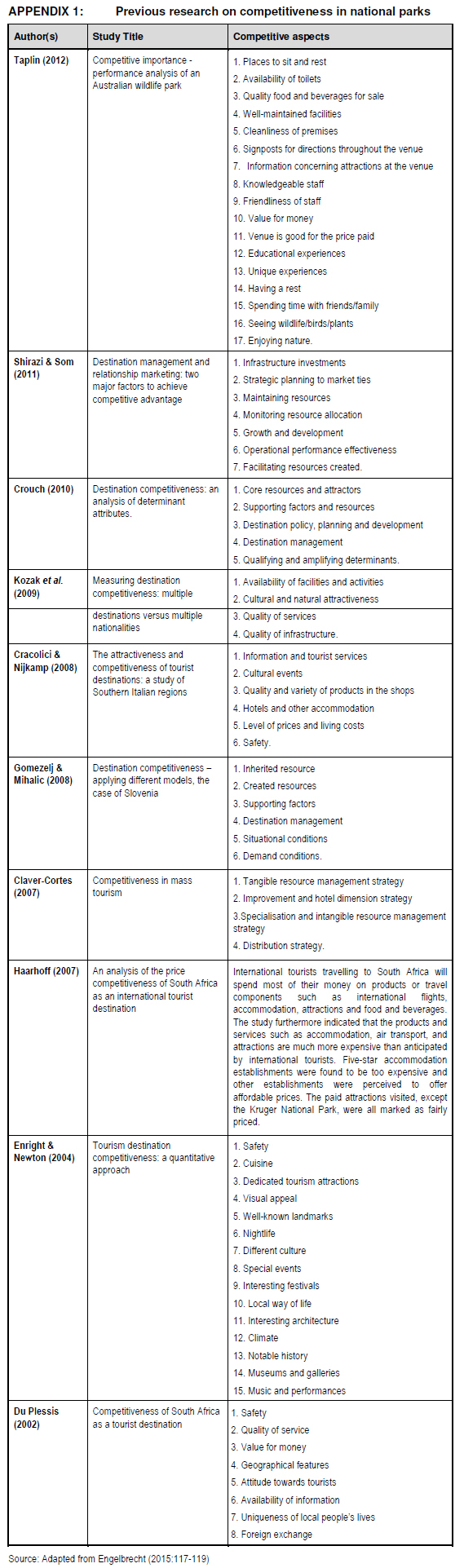

Appendix 1 summarises previous research into competitiveness of tourism destinations. However, those studies that focus on nature-based tourism destinations, such as national parks, are extremely limited in number.

Appendix 1 indicates the numerous significant competitive factors required for a destination to obtain a competitive advantage and include issues of safety, destination management, information and supporting infrastructure. Cracolici and Nijkamp (2008); Du Plessis (2002) as well as Enright and Newton (2004), identify safety as an overlapping competitive factor, showcasing the importance of tourist safety at tourism destinations. Crouch (2010); Enright and Newton (2004); Gomezelj and Mihalic (2008); Kozak Baloglu and Bahar (2009); Shirazi and Som (2011) as well as Taplin (2012) also identify supporting infrastructure or the availability of infrastructure as a very important factor.

In the South African context, Du Plessis (2002) provided eight factors (which do not include wildlife or natural scenery) that influence the competitiveness of South Africa as a tourist destination (Appendix 1). Additionally, Haarhoff (2007) indicated that international tourists perceive the pricing of attractions (with the exception of the Kruger National Park and accommodation which excludes five-star establishments) as competitive pricing structures which position South Africa as a competitive market for international tourists.

It is, however, clear that no previous research had been conducted on national parks showcasing the competitive advantage factors regarded as important by tourists for these nature-based tourism destinations. A destination has a specific set of competitive factors, all of which are determined by internal and external variables, which might also be the case for national parks such as the Kruger National Park. Although some of these factors may be distinct in terms of a particular destination, some might overlap, indicating that certain competitive advantage factors are generic.

3. METHOD OF RESEARCH

The method of research used is discussed under the following headings: (i) the questionnaire; (ii) sampling method and survey; (iii) statistical analysis and results.

3.1 The questionnaire

A questionnaire was designed for this study based on research by authors such as Crouch (2010); Kozak et al. (2009); Scholtz, Kruger and Saayman (2013:2); Shirazi and Som (2011); and Taplin (2012). The questionnaire was divided into the following sections:

Section A: The questions captured the respondents' demographic and behavioural information such as age, home language, gender, income, province and country of residence, number of people in travelling group and when the decision was made to visit the park.

Section B: The questions typically concerned the reasons for travelling; previous park visits, favourite holiday destination and whether the tourist would return to the Kruger National Park.

Section C: Captured the competitive advantage factors for the Kruger National Park where 31 items were measured on a five-point Likert-scale of importance with 1 = not at all important; 2 = slightly important; 3 = important; 4 = very important and 5 = extremely important. Aspects such as Park-specific attributes, a variety of products and services, conservation methods, greener management, service delivery, quality products and management were addressed.

3.2 Sampling method and survey

A quantitative research approach was followed and a probability sampling method was applied where all overnight tourists within the rest camps of the Kruger National Park were selected as participants for the survey. Only overnight visitors who were classified as tourists were asked to complete the questionnaire.

For the purpose of this study, a tourist is defined as a person who travels to a destination that provides economic input to the local area other than where the person resides and works. Furthermore, a tourist is someone who travels voluntarily to destinations or attractions away from his/her normal home for longer than 24 hours and for less than a year (Keyser 2009:62; Page & Connell 2014:10; Saayman 2013:5). Thus, for the purpose of this study further references to visitors or respondents in this study denote tourists.

The survey was conducted at four rest camps in the Kruger National Park. Field workers were employed to distribute the questionnaires to the overnight respondents within the rest camps of Skukuza, Olifants, Lower Sabie and Berg-and-Dal. The four rest camps were identified by the Park management as having high occupancy levels as well as being the largest rest camps in the Park. Furthermore, previous research in this Park was conducted within these rest camps. The survey was undertaken at night between 18:00 and 20:00 in the rest camps when all visitors were either at their chalets or tents. Before each distribution session, the fieldworkers were briefed on the purpose and importance of the research as well as how to approach and explain the questionnaire to the respondents.

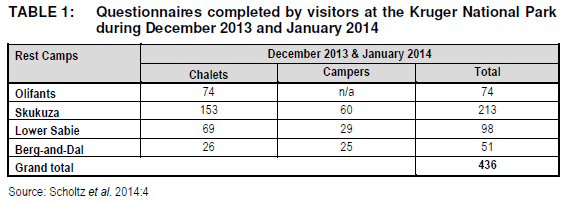

Table 1 records the number of questionnaires administered at each rest camp. A total of 500 questionnaires were distributed in the various camps between the 27 December 2013 and 4 January 2014, of which 436 obtained were included in further analysis.

The Olifants' rest camp does not have camping facilities; therefore, only respondents from chalets completed the questionnaire. Only one questionnaire was handed out per travelling group, which had an impact on the sampling size of the population. The total population was divided by the average group travel size, which was 3.8 people per travel group and resulted in a total of 305 584 tourists travelling to the particular rest camps in the Kruger National Park during the year 2013/2014 (Scholtz et al. 2014:14).

In order to determine the correct sample size for the Kruger National Park, the following formula, designed by Krejcie and Morgan (1970:607), was used:

s = X2NP(1 - P) 4 d2(N - 1) + X2P(1 - P)

In this formula, s indicated the required sample. The desired confidence level (3,841) was represented by X2 in the table value of a chi-square test for one degree of freedom. The population size was represented by N, with P being the population proportion (.50), while d indicated the degree of accuracy, which in fact indicated the confidence level at a proportion of (.05). Krejcie and Morgan (1970:607) indicated that if a population of 1 000 000 was used, the required sample size would be calculated at 384 questionnaires. According to the formula designed by Krejcie and Morgan (1970:607), a population (N) of 305 584 tourists to the Kruger National Park, with a 95% confidence level and 5% sampling error [d is expressed as (0.05)], resulted in a sample of 436 completed questionnaires needing to be collected. The number of completed questionnaires, therefore, encompassed the required number of questionnaires, according to the requirement of Krejcie and Morgan (1970).

4. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

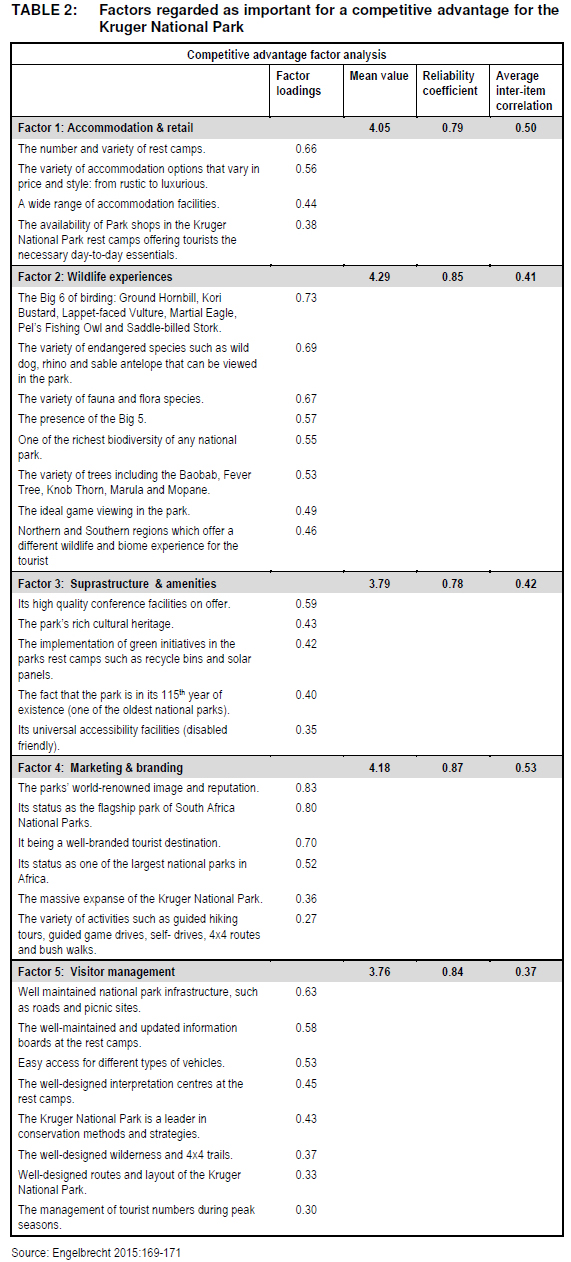

Since this research has to date not been previously undertaken in the South African national parks, an exploratory approach was followed. The pattern matrix of the principal axis factor analysis, using an Oblimin rotation with Kaiser Normalisation, identified five competitive advantage factors that were grouped together based on similar characteristics.

All factors had comparatively high reliability coefficients, ranging between 0.78 (the lowest) and 0.87 (the highest) (Brace, Kemp & Snelgar 2013:382; Malhotra 2007:285; Zikmund, Babin, Carr & Griffin 2010:305-306). The average inter-item correlation proved that there was internal consistency between the factors, with their values ranging from 0.37 to 0.53.

The majority of the variables loaded higher than 0.3 in the factor analysis, revealing a reasonably high correlation between the factors and their component items. The eigenvalues of each factor must be greater than 1.0 to be retained and used in the data discussion. An eigenvalue is defined as the amount of variance associated with the factor (Malhotra 2007:617; Zikmund et al. 2010:594). The sampling acceptability was measured with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of 0.95. This ensured that the patterns of correlation were relatively compact and yielded distinct and reliable factors (Field 2013:684-685). The factors were all tested against Barlett's test of sphericity, meaning that if a factor had a loading that was p < 0.001 it has a statistical significance which in turn supports Pallant's (2007:197) factorability of the correlation matrix.

Table 2 indicates the variables and mean values of factors that have been identified as being competitive advantage factors for the Kruger National Park.

The factor scores were calculated as the average of all items contributing to a particular factor in order to be interpreted on the original 5-point Likert scale of measurement (1 = totally disagree, 2 = do not agree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = totally agree). The identified factors are discussed in more detail in Table 2.

4.1 Factor 1: Accommodation and retail

The number and variety of rest camps, the variety of accommodation options, a wide range of accommodation and the availability of Park shops in the rest camps are all items categorised under Factor 1 and therefore labelled Accommodation and retail. Accommodation and retail was considered to be the third most important factor contributing towards a competitive advantage for the Kruger National Park. This factor obtained a mean value of 4.05, a reliability coefficient of 0.79 and an average inter-item correlation of 0.50.

4.2 Factor 2: Wildlife experiences

Wildlife experience was considered to be the most important factor contributing towards the Kruger National Park establishing a competitive advantage. This factor consists of variables such as the Big 5; the Big 6 birds; number of endangered species; variety of fauna and flora; one of the richest biodiversities of any national park as well as the ideal game viewing in the Park. The mean value was 4.29, with a reliability coefficient of 0.85 and an inter-item correlation of 0.41.

4.3 Factor 3: Suprastructure and amenities

Suprastructure and amenities was rated the fourth most important competitive advantage factor and achieved a mean value of 3.79, a reliability coefficient of 0.78 and an average inter-item correlation of 0.42. Suprastructure and amenities (Factor 3) included the Park's high quality conference facilities on offer; its rich cultural heritage; the implementation of green initiatives in the Park's rest camps, such as recycle bins and solar panels at certain of the rest camps; the 115th year of existence (one of the oldest national parks); and its universal accessibility facilities (disabled friendly).

4.4 Factor 4: Marketing and branding

Marketing and branding was regarded as the second most important factor that may contribute to the Kruger National Park obtaining a competitive advantage over its peers. The Marketing and branding factor obtained a mean value of 4.18, a reliability coefficient of 0.87 and an average inter-item correlation of 0.71. This factor comprises the following aspects: the Park's world-renowned image and reputation; its status as the flagship of SANParks; a well-branded tourist destination; its status as one of the largest national parks in Africa; its massive geographical expanse and the variety of activities in the Park.

4.5 Factor 5: Visitor management

This factor is regarded as the fifth most important factor that the Kruger National Park could apply to obtain a competitive advantage. Visitor Management achieved a mean value of 3.76, a reliability coefficient of 0.84 and an average inter-item correlation of 0.37. Visitor management (Factor 5) comprises the following variables: well-maintained national park infrastructure, such as roads and picnic sites; well maintained and updated information boards at the rest camps; easy access for different types of vehicles; well-designed interpretation centres at the rest camps; its reputation as a leader in conservation methods and strategies; well-designed wilderness and 4x4 trails; well-designed routes and layout of the park.

5. FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS

The findings of this research are as follows:

5.1 Finding 1: The importance of competitive advantage

Firstly, the results confirm that the type and nature of the destination (in this case the particular national park) greatly influences which competitive advantage factors visitors regard as important. This implies that the characteristics of the destination need to be considered when addressing its competitive advantage (Crouch 2010; Hong 2008:33; Mihalic 2000:77). Therefore, the majority of products and services presented by the national park should be unique and park specific to enhance its position of competitiveness as a tourism destination.

5.2 Finding 2: Competitive advantage of national parks

Secondly, previous research conducted by Claver-Cortes Monlina-Azorin and Pereira-Moliner (2007); Cracolici and Nijkamp (2008); Du Plessis (2002); Gomezelj and Mihalic (2008); Haarhoff (2007); Kozak et al. (2009); Shirazi and Som (2011) and Taplin (2012), as indicated in Appendix 1, focused on the competitiveness of a tourism destination and was not unique to national parks, particularly those of South Africa. Therefore, it can be argued that the particular combination of competitive advantage factors found in this research has not been identified in the previous research specific to parks of this kind.

This finding can also be ascribed to the unique characteristics of the Kruger National Park and the fact that few studies in this area have been conducted in national parks. These factors can, therefore, be regarded as distinct and especially important in gaining a competitive advantage for such parks.

This finding emphasises that there is no universal set of competitive advantage factors for destinations and that each set of factors is destination specific. However, while there might be similarities among destinations' competitive advantage factors the level of importance will be destination specific. It is thus important for national parks across South Africa and globally to identify their distinct park specific attributes, products and services that could allow them to become a competitive tourism destination to increase tourist numbers and park revenue, in order to remain sustainable and self-sufficient.

5.3 Finding 3: Competitive advantage factors for the Kruger National Park

Thirdly, five competitive advantage factors were identified (in order of importance): Wildlife Experiences, Marketing and Branding, Accommodation and Retail, Visitor Management and Suprastructure and Amenities.

As discussed in the literature review, previous research indicated that factors such as Wildlife Experience are an important factor that the management of Kruger National Park should take into consideration when managing the visitor experience in the park (Engelbrecht 2011:50).

The factor Wildlife Experiences is significant to this study, as it has not yet been previously identified by any author and is specific to national parks in terms of competitive advantage factors. It is evident that these factors are similar to those in other tourism competitive advantage destination studies. However, the difference between destinations is based on the unique and specific product or service being offered, which, in the case of the Kruger National Park, is the Wildlife Experience. It is therefore evident that continuous research on the competitive advantage factors from a demand side (tourist view) is crucial in staying competitive since in the event of management not monitoring and evaluating these factors on a regular basis, this may negatively influence the park.

According to Engelbrecht (2011:52) and Erasmus (2011:77) accommodation was regarded as less important to the visitors' experience at national parks and arts festivals respectively. However, the respondents at the Kruger National Park indicated that having well-designed, quality accommodation and retail outlets available influences the competitiveness of the destination (Scholtz et al. 2014:43). It is therefore important that the Kruger National Park management upgrades accommodation and retail facilities to a standard which is acceptable and satisfies the needs and expectations of tourists travelling to the park. The offering of well-designed and maintained quality accommodation could allow this Park to obtain a competitive advantage over other privately owned lodges and national parks in Southern Africa.

While marketing and destination management are essential to determining the competitive advantage of a destination, maintenance of the Suprastructure and Amenities is very important. These form the foundation of any tourism destination and should therefore be regarded as an important managerial aspect to be covered for achieving a competitive advantage as this supports the destination's image (Ritchie & Crouch 2003:130). Park management will have to focus on the improvement of the Park's infrastructure and maintain it accordingly for the same reason.

According to Beerli and Martin (2004:623) as well as Ritchie and Crouch (2003:188-189) the way in which a tourist destination is marketed and branded, influences the level of competitiveness. The Kruger National Park should, therefore, ensure that the Marketing and Branding of the park are being managed from a strategic point of view so that a competitive advantage can be obtained. As a national park relies on tourism activities to generate income, the Visitor Management at the park should be of exceptionally high quality in servicing the tourists' expectations (Ritchie and Crouch 2003:139). Kruger National Park management should, therefore, look at ways to improve employee skills and experience through the offering of training programmes focusing on Visitor Management.

6. RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the findings, the following recommendations are made:

6.1 Recommendation 1 : Promotion of significant wildlife experiences

This research identified Wildlife Experiences as the most important competitive advantage factor for a national park such as the Kruger National Park. This furthermore emphasised the important relationship that exists between conservation and tourism within a national park setting. Wildlife Experiences is an external factor over which the said Park's management has no control. In other words, park management cannot control the wildlife in the park as the wildlife roam freely within the borders of the park. More so, with the opening of borders between the Kruger National Park and privately owned game farms, the wildlife have more access to larger habitat areas.

However, Park management can ensure that visitors' Wildlife Experiences are memorable through the optimal management of game drives; interactive activities, interpretation centres; park specific information leaflets and brochures; information boards of wildlife sightings and discussions on the Park's wildlife. As wildlife forms part of the main aims of South African National Parks, in this case, the Kruger National Park, management should ensure that the wildlife, conservation and interactions are managed accordingly since these aspects can also have an influence on the visitor experience if not controlled. The Park could increase its Wildlife Experiences by improving tourist activities and developing new activities that enhance the tourist's chances of interaction with wildlife.

Tourism within national parks is based on the natural environment that determines the success of these parks as tourist destinations. This can be supported by educational wildlife tours, game drives and walks as well as information centres so that tourist awareness of the importance of nature conservation can be improved as well. Kruger National Park management should remember that the tourists' experience at the Park is primarily linked to their Wildlife Experiences and secondarily to the tourism aspects and the visitors will in most instances remember the Wildlife Experiences and interactions first, followed by their experiences of the tourism aspects. However, this is difficult to determine as the animals are not directly managed by Park officials; therefore sightings of animals cannot be guaranteed by the Park because the animals are wild and living in their own habitat.

As a result, improved efforts by park management to ensure wildlife numbers are well managed, more look-out points for wildlife viewing, updated animal movement information at rest camps and current happenings in the Park with regard to wildlife numbers and interesting facts are all ways in which tourists' Wildlife Experiences can be satisfied.

Lastly, the Kruger National Park should use the Wildlife Experience factor in its Marketing and Branding (which is also the second most important competitive advantage factor) to promote the park to tourists, showcasing the significant Wildlife Experiences that can be experienced when visiting the Park.

6.2 Recommendation 2: Marketing should be managed as an asset

Marketing (as a whole) and Branding is a vital component of general management at the Kruger National Park and was identified as the second most important competitive advantage factor. The Park's general management team must, therefore, ensure that quality promotions are being developed and positive word-of-mouth is being practised. This can all be done through determining the quality of the promotional items used in marketing campaigns and the level of service quality in the Park.

This Park should brand itself and market the Park as a brand that offers various wildlife experiences, interactive activities for all ages and an all-in-one destination with superior products and services on offer at the Park. To reinforce the Kruger National Park as a standalone brand, memorabilia and clothing should be well designed and portray the Wildlife Experience on offer.

The Park should furthermore capitalise on social media such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn and YouTube, to name a few, for marketing the Park to the younger generation. The Kruger National Park could also consider offering the younger generation a discounted offer similar to that for the over 60's tourists in order to promote the Park and draw a younger group of people. Through the implementation of a discounted offer, this Park could make itself more accessible for the younger generation. Tourists' loyalty towards the Park could be increased through the marketing of special break-always and activities for tourists travelling with children during the holiday season and vice versa in low season as well as by promoting the benefits of the Wildcard (loyalty programme). Furthermore, the Park should focus on its park specific attributes that gives it a competitive advantage and continuously evaluate and improve on these attributes.

6.3 Recommendation 3: Upgrading accommodation facilities in the Kruger National Park

Accommodation and Retail was identified as the third most important contributor to the competitiveness of the Kruger National Park. While Accommodation and Retail are primary tourism aspects, however in the case of a national park, tourists regard these as secondary aspects. The Kruger National Park could increase accommodation occupancy through an upgrade of the current chalets so that they are more modern while still reflecting the rustic natural and culturally aesthetic feel. This could be achieved by for instance, transforming chalets into becoming greener facilities through implementing solar panels for electricity generation; increasing recycling methods through awareness campaigns in chalets and by making use of recycling bins and using bio-degradable chemicals for cleaning purposes in the Park and its rest camps.

The Park's potential for usage of gas for electrical appliances such as fridges, stoves and geysers could also enhance it in becoming a greener destination and minimising expenses. The campsites could be upgraded so that each campsite has an electricity point that could be powered by solar panels for essentials, such as fridges and lights. The Park should also clearly mark the stands in the campsite, so that optimal occupancy can be managed with tourists restricted to specific areas when camping so as not to waste space. The park should ensure that camping ablution facilities are serviced and clean, as this has emerged as a problem experienced by campers at certain sites.

6.4 Recommendation 4: Improving the Kruger National Park's infrastructure

Suprastructures and Amenities was identified as the fourth most important competitive advantage factor. Kruger National Park management should ensure that the Suprastructures and Amenities within the park are suitably built and developed to minimise the possibility of negative impact on the environment. Roads (tar and gravel), especially gravel roads, should be maintained especially after heavy rains in the park.

General maintenance of all Suprastructures and Amenities, such as look-out points; picnic sites and reception offices in the park should be conducted. Regular painting, upgrading, cleaning of ablution facilities and the availability of essential products at the retail stores are important to ensure proper maintenance in this regard.

The retail stores should ensure that essential products are always available for tourists in the Park. Park managers have to ensure that the supra- and infrastructure exteriors are up to standard.

6.5 Recommendation 5: Managing the visitors expectations and experiences at the Kruger National Park

Visitor Management was identified as the fifth most important ecotourism aspect in ensuring a competitive advantage for the Kruger National Park. It is crucial that at all times the Park employees should be helpful, friendly and courteous to tourists in the Park.

Park management should ensure that employees are well-educated, skilled and knowledgeable about the Park as a whole to improve the visitor experience. This is a human resource function and proper training and development courses should be developed in collaboration with tertiary institutions and presented to the employees of the park. It remains essential that continuous research be done to determine the tourists' profile, motivations and behavioural characteristics.

Since the majority of tourists are well-educated, the implementation of interesting educational activities for adults, children and families at the rest camps, as well as when they drive themselves, could further educate tourists about nature, national parks and the importance of prioritising conservation.

This response emphasises the notion that employees should undergo continuous training and development courses to keep updated with respect to changes in the industry. Implementing a mobile device application could address the latter, enhance tourist experience and increase the Park's competitive advantage.

7. CONCLUSION

The aim of this research was to identify the competitive advantage factors as perceived by a tourist visiting the Kruger National Park, in becoming a competitive tourism destination. It is clear that the said Park's management should investigate which products and services are unique and specific to it in order to obtain a competitive advantage. However, similar research could be used to determine the competitive advantage of other national parks and privately owned game farms, based on their specific and unique attributes.

The Park-specific products and services identified in this Park should be converted into competitive advantage factors that are managed in such a manner that it increases revenue by attracting more tourists and ensuring profitable and sustainable management of the given Park.

Competitive advantage factors amongst tourism destinations, especially nature-based tourism destinations, will differ; therefore, each park should identify its own competitive advantage factors and manage these accordingly. This study affirms that the Kruger National Park's most important competitive advantage factor is that of Wildlife Experiences; therefore the Park management should focus on this as its main competitive advantage factor in marketing and promoting the destination.

Future research could focus on the standardisation of the questionnaire, and conduct similar research within other national parks across South Africa as well as Southern Africa. This would highlight the significant differences that exist between the motivational and competitive advantage factors among national parks in Africa. The focus of competitiveness among tourism destinations offering adventure activities could also be investigated as this is one of the fastest-growing sectors of the tourism industry.

Lastly, future research could be carried out through a comparison among the three biggest national parks: Kruger National Park, Kgalagadi Transfrontier National Park and the Addo Elephant National Park in South Africa or even others in Southern Africa to identify their respective competitive advantage factors.

Furthermore, future research could also be conducted in identifying the comparative factors of national parks in general and comparing these with the competitive advantage factors to determine how these two aspects could contribute to the overall competitiveness of a national park.

REFERENCES

AL-MASROORI RS. 2006. Destination competitiveness: Interrelationships between destination planning and development strategies and stakeholders' support in enhancing Oman's tourism industry). Melbourne, AU: Griffith University. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation [ Links ]

AMBASTHA A & MOMAYA KS. 2004. Competitiveness of firms: review of theory, frameworks and models. Singapore Management Review 26(1):45-61. [ Links ]

ARMENSKI T, GOMEZELJ DO, DJURDJEV B, DERI L & ALEKSANDRA D. 2011. Destination competitiveness: a challenging process for Serbia. Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography 5(1):19-33. [ Links ]

ASCH D & WOLF B. 2001. New economy: on competition: the rise of consumer? New York, NY: Palgrave. [ Links ]

AYLWARD B & LUTZ E. 2003. Nature tourism, conservation and development in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

BEERLI A & MARTIN J.D. 2004. Tourists' characteristics and the perceived image of tourist destinations: a quantitative analysis - a case study of Lanzarote, Spain. Tourism Management 25(1):623-636. [ Links ]

BRAACK LEO. 2006. Kruger National Park. 4th ed. Cape Town: New Holland. [ Links ]

BRACE N, KEMP R & SNELGAR R. 2013. SPSS for psychologists. 5th ed. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

BUCKLEY R. 2008. Tourism as a conservation tool. Management for Protection and Sustainable Development 1(1):19-25. [ Links ]

BUHALIS D. 2000. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management 21 (1):97-116. [ Links ]

BUSHELL R & EAGLES PFJ. 2007. Tourism and protected areas: benefits beyond boundaries. Wallingford, UK: CABI. [ Links ]

CHEN C, CHEN SH & LEE HT. 2011. The destination competitiveness of Kinmen's tourism industry: exploring the interrelationships between tourist perceptions, service performance, customer satisfaction and sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19(2):247-264. [ Links ]

CLAVER-CORTES E, MOLINA-AZORIN JF & PEREIRA-MOLINER J. 2007. Competitiveness in mass tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 34(3):727-745. [ Links ]

CRACOLICI MF & NIJKAMP P. 2008. The attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations: a study of Southern Italian regions. Tourism Management 30(1):336-344. [ Links ]

CROUCH G & RITCHIE J. 1994. Destination competitiveness: exploring foundations for a long-term research program. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Administrative Sciences Association of Canada. (Proceedings of the Administrative Sciences Association of Canada. 1994 Annual Conference, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Jun 25-28. pp. 79-88. [ Links ])

CROUCH GI. 2010. Destination competitiveness: an analysis of determinant attributes. Journal of Travel Research 50(1):27-45. [ Links ]

DIEKE PUC. 2001. Kenya and South Africa. In Weaver DB (eds). The encyclopedia of ecotourism. New York, NY: CABI. pp. 89-105. [ Links ]

DU PLESSIS E. 2002. Competitiveness of South Africa as a tourist destination. Potchefstroom: Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education. (MA - dissertation). [ Links ]

DU PLESSIS L, VAN DER MERWE P & SAAYMAN M. 2012. Environmental factors affecting tourists' experience in South African National Parks. African Journal of Business Management 6(8):2911-2918. [ Links ]

DWYER L & KIM C. 2003. Destination competitiveness: determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism 6(1):369-414. [ Links ]

DWYER L & KIM CW. 2001. Destination competitiveness: development of a model with application to Australia and the Republic of Korea. Australia and Korea: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Korea Tourism Research Institute, the Republic of Korea, and Department of Industry, Science, and Resources, CRC for Sustainable Tourism, Australia-Korea Foundation. Report prepared for Department of Industry Science and Resources, Australia and Korea Tourism Research Institute, Ministry of Tourism. [ Links ]

DWYER L, EDWARDS D, MISTILIS N, ROMAN C & SCOTT N. 2009. Destination and enterprise management for a tourism future. Tourism Management 30(1):63-74. [ Links ]

DWYER L, FORSYTH P & RAO P. 2002. The price competitiveness of travel and tourism: a comparison of 19 destinations. Tourism Management 21 (1):9-22. [ Links ]

DWYER L, LIVAIC Z & MELLOR R. 2003. Competitiveness of Australia as a destination. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 10(1):60-78. [ Links ]

EAGLES PFJ. 2002. Trends in park tourism: economics, finance and management. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 10(2):132-153. [ Links ]

ENGELBRECHT WH. 2011. Critical success factors for managing the visitor experience at the Kruger National Park. Potchefstroom: North-West University. (MCom-dissertation). [ Links ]

ENGELBRECHT WH. 2015. Developing a competitiveness model for South African National Parks. Potchefstroom: North-West University. (PhD-thesis). [ Links ]

ENRIGHT MJ & NEWTON J. 2004. Tourism destination competitiveness: a quantitative approach. Tourism Management 25(1):777-788. [ Links ]

ERASMUS LJJ. 2011. Key success factors in managing the visitors' experience at the Klein Karoo National Arts Festival. Potchefstroom: North-West University. (M.Com-dissertation). [ Links ]

FIELD A. 2013. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4th ed. London, UK: Sage. [ Links ]

FORSYTH P & DWYER L. 2009. Tourism price competitiveness. Travel and tourism competitiveness report 2009: World Economic Forum. [Internet: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GCR_TravelTourism_Report_2009.pdf; downloaded on 2012-03-25. [ Links ]]

GO FM & GOVERS R. 2000. Integrated quality management for tourist destinations: a European perspective on achieving competitiveness. Tourism Management 21(1):79-88. [ Links ]

GOMEZEL JDO & MIHALIC T. 2008. Destination competitiveness: applying different models, the case of Slovenia. Tourism Management 29(1):294-307. [ Links ]

GRANT RM. 2008. Contemporary strategy analysis. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell. [ Links ]

HAARHOFF R. 2007. An analysis of the price competitiveness of South Africa as an international tourist destination. Bloemfontein: Central University of Technology. (MCom-dissertation). [ Links ]

HASSAN SS. 2000. Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. Journal of Travel Research 38(3):239-245. [ Links ]

HEATH E. 2003. Towards a model to enhance destination competitiveness: a Southern African perspective. [Internet: http://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/6058/Heath_Towards%282003%29.pdf?sequence=1; downloaded on 2014-05-14. [ Links ]]

HONEY M. 1999. Ecotourism and sustainable development: who owns paradise? Washington, DC: Island Press. [ Links ]

HONG WC. 2008. Competitiveness in the tourism sector: a comprehensive approach from economic and management points. Heidelberg, DE: Physica-Verlag. [ Links ]

HSU T, TSAI Y & WU H. 2009. The preference analysis for tourist choice of destination: a case study of Taiwan. Tourism Management 30(1):288-297. [ Links ]

HU W & WALL G. 2005. Environmental management, environmental image and the competitive tourist attraction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 13(6):617-635. [ Links ]

HUGGUINS R & IZUSHI H. 2011. Competition, competitive advantage, and clusters: the ideas of Michael Porter. In Huggins R & Izushi H (eds). Competition, competitive advantage, and clusters: the ideas of Michael Porter. Oxford University Press: Oxford. pp. 1-22. [ Links ]

JURDANA DS. 2009. Specific knowledge for managing ecotourism destinations. Tourism and Hospitality Management 15(2):267-278. [ Links ]

KEYSER H. 2009. Developing tourism in South Africa: towards competitive destinations. 2nd ed. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [ Links ]

KOMPPULA R. 2006. Developing the quality of a tourist experience product in the case of nature-based activity services. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 6(2):136-149. [ Links ]

KOTLER P, HAIDER DH & REIN I. 1993. Marketing places: attracting investment, industry, and tourism to cities, states and nations. New York, NY: The Free Press. [ Links ]

KOZAK M. 2001. Comparative assessment of tourist satisfaction with destinations across two nationalities. Tourism Management 22(4):391-401. [ Links ]

KOZAK M, BALOGLU S & BAHAR O. 2009. Measuring destination competitiveness: multiple destinations versus multiple nationalities. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management 19(1):56-71. [ Links ]

KREJCIE RB & MORGAN DW. 1970. Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement 30(3):607-610. [ Links ]

KUO I. 2002. The effectiveness of environmental interpretation at resource-sensitive tourism destinations. International Journal of Tourism Research 4(1):87-101. [ Links ]

LEAL D & FRETWELL H. 1997. Parks in transition: a look at state parks. Property and Environment Research Centre. [Internet: http://www.perc.org/articles/parks-transition#MI; downloaded on 2015-07-15. [ Links ]]

LEBERMAN SI & HOLLAND JD. 2005. Visitor preferences in Kruger National Park, South Africa: the value of a mixed-method approach. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 25(2):21-36. [ Links ]

LOON R, HERPER I & SHORTEN P. 2007. Sabi Sabi: a model for effective ecotourism, conservation and community development. hn Bushell R & Eagles PFJ (eds). Tourism and protected areas: benefits beyond boundaries. Wallingford, UK: CABI International. The 5th INCN World Parks Congress. pp. 264 - 267. [ Links ]

MA H. 1999. Creation and pre-emption for competitive advantage. Management International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 16(5):279-286. [ Links ]

MABUNDA D. 2010. South African National Parks (SANParks) Strategic Plan 2010-13 and Budget 2010-11 Presentation. South African National Parks (SANParks) briefing on their functions, objectives, targets and challenges 2009/10-2013 and Budget 2009/10. [Internet: https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/11315/; downloaded on: 2015-07-16. [ Links ]]

MALHOTRA NK. 2007. Marketing research: an applied orientation. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

MAZANEC JA, WÖBER K & ZINS AH. 2007. Tourism destination competitiveness: from definition to explanation? Journal of Travel Research 46(3):46-86. [ Links ]

MIDDLETON VTC, FYALL A & MORGAN M. 2009. Marketing in travel and tourism. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

MIHALIC T. 2000. Environmental management of a tourist destination: a factor of tourism competitiveness. Tourism Management 21(1):65-78. [ Links ]

MUHUMUZA M & BALKWILL K. 2013. Factors affecting the success of conserving biodiversity in national parks: a review of case studies from Africa. International Journal of Biodiversity 2013(1): 1-20. [ Links ]

NAVICKAS V & MALAKAUSKAITE A. 2009. The possibilities for the identification and evaluation of tourism sector competitiveness factors. The Economic Conditions of Enterprise Functioning 1(61):37-44. [ Links ]

PAGE SJ & CONNELL J. 2014. Tourism: a modern synthesis. 4th ed. Hampshire, UK: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

PALLANT J. 2007. SPSS survival manual: a step-by-step guide to data analysis using SPSS version 15. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PEAKE S, INNES P & DYER P. 2009. Ecotourism and conservation: factors influencing effective conservation messages. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 17(1):107-127. [ Links ]

PEDERSEN A. 2002. Managing Tourism at World Heritage Sites: a Practical Manual for a World Heritage Site Manager. Paris, FR: UNESCO World Heritage Centre. [ Links ]

POON A. 2003. Competitive strategies for a 'new tourism'. In Cooper C (eds). Classic reviews in tourism. Clevedon, UK: Channel View Publications. pp. 130-142. [ Links ]

PORTER ME. 1985. Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. New York, NY: The Free Press. [ Links ]

PORTER ME. 2008. The five competitive forces that shape strategy. In Porter ME (eds). On competition: updated and expanded edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Book. pp. 3-35. [ Links ]

RITCHIE JRB & CROUCH G. 2003. The competitive destination: a sustainable tourism perspective. Wallingford, UK: CABI. [ Links ]

SAAYMAN M. 2009. Managing parks as ecotourism attractions. In Saayman M (ed). Ecotourism: getting back to basics. Potchefstroom: Institute for Tourism and Leisure Studies, North-West University. pp. 345-383. [ Links ]

SAAYMAN M. 2013. En route with tourism: an introductory text. 4th ed. Pretoria: Juta. [ Links ]

SANPARKS see SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL PARKS [ Links ]

SCHOLTZ M, DU PLESSIS E & SAAYMAN M. 2014. Understanding visitors to Kruger National Park. Potchefstroom. TREES: North-West University. (Unpublished report). [ Links ]

SCHOLTZ M, KRUGER M & SAAYMAN M. 2013. Understanding the reasons why tourists visit the Kruger National Park during a recession. Acta Commercii 13(1):1-9. [ Links ]

SCOTT BR & LODGE GC. 1985. US competitiveness in the World Economy. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

SHAW G, SAAYMAN M & SAAYMAN A. 2012. Identifying risks facing the South African tourism industry. South African Journal of Economic Management Sciences 15(2):190-206. [ Links ]

SHIRAZI SFM & SOM APM. 2011. Destination management and relationship marketing: two major factors to achieve competitive advantage. Journal of Relationship Marketing 10(1):76-87. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL PARKS. 2013. Annual report 2012/2013. 144 p. [Internet: http://www.sanparks.org; downloaded on: 2014-04-30. [ Links ]]

SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL PARKS. 2014. SANParks Official Website. [Internet: http://www.sanparks.org/parks/kruger/; downloaded on: 2014-07-09. [ Links ]]

TAPLIN RH. 2012. Competitive importance-performance analysis of an Australian wildlife park. Tourism Management 33(1):29-37. [ Links ]

THOMPSON J & MARTIN F. 2010. Strategic management: awareness & change. Hampshire, UK: South-Western Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

VAN DER MERWE P & SAAYMAN M. 2008. Travel motivations of tourists visiting Kruger National Park. African Protected Area Conservation and Science 50(1):154-159. [ Links ]

VAN RAAIJ WF. 1986. Consumer research on tourism: mental and behavioral constructs. Annals of Tourism Research 13(1):1-9. [ Links ]

VAN WYK J. 2011. Case study: Kamieskroon bed & breakfast. In Tassiopoulos D (eds). New tourism ventures: an entrepreneurial and managerial approach. 2nd ed. Claremont, Cape Town: Juta. pp. 365-381. [ Links ]

WADE DJ & EAGLES PFJ. 2003. The use of importance-performance analysis and marketing segmentation for tourism management in parks and protected areas: an application to Tanzania's National Parks. Journal of Ecotourism 2(3):196-212. [ Links ]

WOOD R. 2004. Delivering customer value generates positive business results: a position paper. Futurics 28(1/2):59-64. [ Links ]

ZIKMUND WG, BABIN BJ, CARR JC & GRIFFIN M. 2010. Business research methods. 8th ed. Mason, OH: South Western Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

* corresponding author