Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.10 no.1 Meyerton 2013

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Followership in contemporary organisations: a South African perspective

N Singh; S Bodhanya

University of KwaZulu-Natal

ABSTRACT

When a problem is experienced in an organisation, the leader or manager is often the person to refer to in the first instance. However, the constant change characteristic of contemporary organisational environments often creates complex problems that the leader cannot solve alone. Insufficient attention has been given to the dynamics of followership and those who follow the leader in the workplace. This is surprising considering that followers constitute the bulk of most organisations, and thus have immense influence in determining the welfare of contemporary organisations. This study aims to investigate the complexities of followership in contemporary organisations, by examining the factors that influence followers on an individual, organisational and environmental level. Recognition is also given to followers as powerful actors who in turn influence other individuals, the organisation itself and the environment in which the organisation is embedded. The investigation was carried out using an empirical study of the dynamics of followership in a range of contemporary organisations in South Africa including government and non-governmental organisations, parastatals, commercial firms and civil society institutions.

Key phrases: employees, followership, leadership, management, South Africa, systems thinking

1. INTRODUCTION

Autocratic leadership, charismatic leadership and transformational leadership are just some of the styles of leadership that have been marketed by business and management experts as being of critical importance in transforming inefficient and disillusioned workers into motivated, effective and exemplary followers. However, workers in an organisational setting may behave in a variety of ways, irrespective of the quality of leadership in the organisation. This has revitalised interest in the other players in the organisational chess game, namely the followers, or those who must follow the directives of the leader/s of the organisation.

While leadership and leaders are an important part of organisational life, they cannot exist without followers (Blanchard, Welbourne, Gilmore & Bullock 2009:111, Fields 2007:204, Meindl 1995:331). It is surprising therefore, that there exists such a great disparity between the volume of existing leadership and followership literature, with leadership literature far outweighing that on followership (DeChurch, Hiller, Murase, Doty & Salas 2010:1083, Gilbert & Hyde 1988:962).

The article begins with a review of the literature on the phenomenon of followership and developments in organisational studies related to followership. The evolution of the concept of followership is traced, as well as its rise to importance in the understanding of organisational life and functioning. The qualitative methodology guiding this research included the use of open-ended questionnaires directed at various types of organisations in South Africa. The findings of the study are then explored by incorporating the factors identified as influencing followers into a followership model. The implications of the overall findings for the issues of leadership and management in contemporary organisations are also explored.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Defining 'followership'

While there are countless definitions of leadership, attempting to define or find an appropriate definition of the concept of followership is a much greater challenge (Crossman & Crossman 2011:481), due significantly to the lack of studies pertaining to the phenomenon of followership itself. In an examination of sixty peer-reviewed journal articles, only ten provided a definition of followership, albeit a very brief one. This demonstrates a lack of understanding of the fundamental meaning of followership and reluctance by followership authors to posit alternative definitions.

Like leadership, there is no single definition of followership. It generally refers to the activity of individuals who are subordinate to the leader/s and who are responsible for working actively hand-in-hand with their leader or leaders to accomplish the main objectives of the organisation (Baker & Gerlowski 2007:15). Followership encompasses more than a passive surrendering to the leader, but rather a willingness to engage in the act of following the leader in order to achieve certain individual or organisational goals (Brown 2003:68). It is not simply about the isolated role of the follower, but rather it encompasses the notion of a person who acts in relation to a leader (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera & McGregor 2010:545).

2.2 Creating a balanced definition of followership

Confusion arises when attempting to create a balanced definition of followership that encapsulates both the autonomy of the follower, as well as their duty as followers to give up a degree of this autonomy in order to 'follow'. The above definitions either stress the obedience and responsibility of followers to comply with their leader/s or exaggerate the independence of the follower while overlooking the complex relationship that exists between leaders and followers. A more balanced definition of followership describes it as "a process in which subordinates recognise their responsibility to comply with the orders of leaders and take appropriate action consistent with the situation to carry out those orders to the best of their ability. In the absence of orders, they estimate the proper action required to contribute to mission performance and take that action" (Townsend & Gebhardt 1997:140).

Not only do individuals fluctuate in the sense that they may demonstrate different levels of follower effectiveness and efficiency at different times, but they, along with those in leadership positions, may move back and forth between demonstrating leader behaviour and follower behaviour. For this reason, Stech (2008:47) described both leadership and followership as "states or conditions that can be occupied at various times by persons in working groups, teams or organisations". Ultimately, this explanation seeks to debunk the myth that an individual must be either a leader or a follower, because not only do they have the potential to be both leader and follower, but they may also demonstrate the characteristics of leadership or followership, irrespective of the position they occupy. This is particularly relevant to modern workplaces and organisational structures as it is common to find people who must lead others, while at the same time reporting to those who are higher than them in the organisational hierarchy (Stech 2008:46). This also points to the integrated nature of followership and leadership in the sense that they do not exist as isolated entities, but rather they are defined and exist in relation to one another (Kupers & Weibler 2008:447, Agho 2009:165).

Countries that have taken the lead in followership studies such as America and Europe are now beginning to voice their concerns over the inappropriateness of the concepts of 'followership' and 'followers' (Banutu-Gomes 2004:143, Kelley 2008:5-6, Rost 2008:56, Sronce & Arendt 2009:708, Stech 2008:44). The social connotations that have become synonymous with these concepts are that to 'follow' presupposes a lack of initiative, a certain degree of helplessness and a large degree of powerlessness. Such negative connotations also arise from the understanding of followers as referring to people who must continuously be told exactly what to do and how to do it (Banutu-Gomes 2004:143) or passive individuals who are not willing or not able to take responsibility, thus making them insignificant (Brown & Thornborrow 1996:5) and negating their sense of autonomy and intelligence. The negative perceptions surrounding the concept of followers and consequently, followership, have also contributed to an atmosphere of uneasiness and apprehension in the use of such terms. This has increased the silence and ignorance around followership and followers even further.

2.3 The recognition of 'followership' as an important organisational phenomenon

While information on followership studies can most often be found in management journals, it comes as a surprise that the earliest theories of followership emerged from the father of psychology himself, Sigmund Freud. Freud developed the famous branch of psychology known as Psychoanalysis which was based on his belief that the root cause of mental pathologies and everyday phenomena could be traced back to the unconscious (or hidden part) of the individual's mind (De Sousa 2011:210217). Through his studies in 1921, he was able to identify a psychological link between leaders and followers (Baker 2007:52).

In 1933, Mary Parker Follett first mentioned the concept of 'followers' specifically in relation to followers located in organisational and business settings. She was also the first to propose the idea of the inter-dependent nature of the leader and follower relationship and to emphasise the importance of followers in keeping organisational situations under control (Gilbert & Hyde 1988:962). Follett was the first to make explicit the tendency of leaders and society to downplay the importance of followers, and her speech was one of the earliest calls for action to address this deficiency in management thinking.

In 1955, Hollander re-emphasised the interdependent nature of followership and leadership, and posited the idea of followers who were very active in influencing organisational dynamics, thus moving away from the dominant idea of followers as passive subordinates (Baker 2007:52-53). Integral to Hollander's ideas was his belief in the dynamic nature of leadership and followership, in that a single individual may possess both tendencies, instead of being confined to the position of either leader or follower alone.

Most management literature during this time had the tendency to identify all followers as one homogenous group, thus failing to recognise the differences between individual followers. It was only in 1965, that Zaleznik began to explore the differences between the followership styles exhibited by different individuals. Using the term 'subordinates', which was the commonly accepted term for followers during the sixties, he identified four separate subordinate styles: impulsive subordinates, compulsive subordinates, masochistic subordinates and withdrawn subordinates. These four subordinate styles however, were characterized by negative or dysfunctional attributes such as the tendency of the subordinate to be withdrawn, overly controlling, rebellious, etc. (Baggaley, Carson, Haycock-Stuart & Kean 2011:508).

As the seventies dawned, the relationship and interactions between leaders and followers become an area of much interest, thus giving birth to a variety of Social Exchange theories. One of these was developed by Graen and Uhl-Bien and was known as Leader-Member Exchange or LMX. Graen and Uhl-Bien's main focus was on the interactions that occurred between leaders and their followers (or members), and how such interactions resulted in overall changes in the way in which such leaders and followers relate to each other in the workplace (Baker 2007:54). LMX also states that the dynamics of such a relationship will differ (Van Gils, Van Quaquebeke & Van Knippenberg 2010:334), based on the characteristics demonstrated by individual followers and that such relationships are not static, but often fluctuate with time and organisational circumstances (Boyd & Taylor 1998:6).

2.4 Moving away from a preoccupation with leadership

The next great shift in understanding followership emerged in the nineties from Meindl who believed that the main reason why followership was unheard of and followers neglected was due to the world's preoccupation with leaders and leadership (Hurwitz & Hurwitz 2009:200), thus his work was referred to as The Romance of Leadership (Meindl 1995:330). This, he believed, had blinded people to the crucial importance of followers and their role within groups and organisations. He also asserted that followers react more significantly to their personal constructions or ideas of their leader and leadership, than to the actual qualities and personalities of the leader themselves. Therefore, Meindl moved away from the common tendency to explain leadership by focusing on the leader alone, as he believed that 'leadership' emanated from the collective mental constructions of followers, thus giving further credence to the idea of followers as being central to organisational dynamics.

The nineties also saw the emergence of people deeply concerned with making followership an everyday concept like Kelley, for example, whose 1988 article in The Harvard Business Review entitled In Praise of Followers and his book The Power of Followership made it unquestionably clear that Followership and consequently followers were his primary concern. He developed a model of followership by identifying five follower styles: Conformist followers, Passive followers, Pragmatist followers, Alienated followers and Exemplary followers; based on the levels of thinking and action exhibited by such followers (Bjugstad, Thach, Thompson & Morris 2006:309-310). Since Kelley saw the act of following the leader as a conscious decision made by the individual (Townsend & Gebhardt 1997:136), he believed that exemplary followers attached an immense sense of pride and dignity to their follower roles (Kellerman 2008:80). Therefore, the main aim of his followership studies was to discover ways in which to foster an exemplary behaviour style in all followers.

This was also an attempt to uncover particular traits of followers at a time when most management literature exemplified the characteristics and traits of leaders. Kelley aimed at drawing attention to followers as individuals capable of thinking and acting for themselves, in that it was ultimately up to them to decide whether or not to follow the leader (Townsend & Gebhardt 1997:138) and the amount of commitment that they would invest in their follower roles, if any at all. His model of follower styles marked a significant evolution from Zaleznik's dysfunctional follower styles in presenting a more positive view of the traits exhibited by such followers. In this way, he paved the way for further research and studies on the positive aspects of followership and the potential of followers to possess qualities originally attributed only to those in leadership positions

Along with Kelley, it was Chaleff that recognised the importance of followers and followership in his book, The Courageous Follower: Standing up to and for Our Leaders. His studies stemmed from his confusion as to how followers could be so unquestioning and apathetic in the performance of inhumane acts such as those that occurred during the Holocaust. He realised that most people were at a loss as how to develop healthier ways of following, beyond passively obeying their leader (Chaleff 1995, 2003, 2008:67). This began his journey to discover principles that followers could use to guide their actions and interactions with their leaders (and the world), to prevent such inhumanity from occurring again. Thus, Chaleff aimed at developing 'courageous followers' who would have the capacity to turn away from the negative influence of destructive and self-serving leaders (Gunn 1996:3-4).

Kellerman's recent book, Followership: how followers are creating change and changing leaders, has added to the recent surge in literature on followership. The title emphasises Kellerman's belief in the importance of followers in bringing about change and influencing leaders and leadership in all contexts, not just the organisation. However, an important contribution she has made is to draw attention to the unfixed nature of leadership and followership roles. She also produced her own followership model by grouping followers according to the level of engagement they demonstrate, thus identifying followers as Isolates, Bystanders, Participants, Activists and Diehards (Kellerman 2008:84-93). Her book was written for both leaders and followers because she believed that most people occupy both roles simultaneously and because she asserts that every single person is a follower first (as they must follow their elders to survive as children and they must obey a leader/s, before they can become leaders themselves). She was also instrumental in recognising the relationship between 'bad followership' and 'bad leadership' as contributing to and reinforcing each other.

It is due to the work of the above scholars that followership has slowly begun to take its place alongside the importance of leadership as being pivotal in the explanation and understanding of organisational dynamics. Thus, the focus of this study was to explore the factors that motivate and impede followers in the performance of their workplace duties and roles and in their relationship with the leader/s of the particular organisation.

3. METHODOLOGY

The methodology of the research process was aimed at exploring the phenomenon of followership among organisational followers in South Africa. This was regarded as an important pursuit as the dynamics of followership had never before been explored among South African workers due to the ignorance surrounding the importance of followers in the leader-follower relationship in organisational settings. The relationship of followers to their leaders is of prime importance, especially in organisations, as the leader cannot operate or manage an entire organisation alone and must therefore depend on his/her followers to assist him/her in this regard. Thus, the dynamics of followership in an organisation can exert an even greater influence on the organisation than the leader alone.

Based on the above rationale, the objectives of the research were to:

• Identify the factors that motivate South African followers in their followership roles and duties.

• Identify what South Africans deem most important to their experience and enactment of followership in their respective organisations.

• Determine if, and how, these followership dynamics are influenced by South African contextual factors.

The study was guided by a qualitative approach to the research. The main aim of qualitative research is to explore and understand the innermost thoughts and behaviour of those under study (Pugsley 2010:332). It was deemed appropriate for this study as the main aim of the research was to delve into, explore and understand each of the respondents' personal conceptualisations of followership, as well as the manner in which they experienced and enacted their followership roles and duties based on such conceptualisations.

Qualitative questionnaires were distributed to a sample of a hundred and twenty possible respondents to determine the motivations and dynamics of followership among South African workers. The goal was to acquire at least forty questionnaires, thus resulting in the distribution of more questionnaires than was needed as recognition was given to the fact that not all respondents would answer the questionnaires. The questionnaires were administered to respondents from diverse organisational contexts in South Africa including: Government and non-governmental organisations, parastatals, commercial firms and civil society institutions. The desire to utilise just forty questionnaires was based on the scope of the study, as well as the researcher's estimation as to the amount of time required to analyse and write up the data findings, so as to be viable with regard to the time available to the researcher and dissertation word constraints.

Individuals comprising the sample were either selected (included) or not selected (excluded) on the basis of certain criteria. In terms of age delimitations, people older than 20 years and younger than 70 years were selected in order to provide representation for most age groups. Those younger than 20 years of age were not included, as it was necessary for participants to have at least a few years of work experience at the time of participating in the research. No restrictions were placed in terms of gender of the participants, with both females and males represented in the research. This was extended to race as well in the sense that all race groups were given the opportunity to participate.

3.1 Selection of the sample

This research utilised non-probability sampling, which differs from probability sampling, in that the researcher selects particular individuals on the basis of certain criteria, to participate in the research and thus, comprise the sample. Therefore, participants are not randomly selected as in probability sampling. Since the researcher selects participants based on his/her own personal preferences, non-probability sampling will have a greater degree of researcher bias. This is because the selected population will not have the correct proportions because all individuals comprising such a population do not have an equal chance of being represented, since specific individuals are selected by the researcher (Lunsford & Lunsford 1995:109).

However, non-probability sampling was chosen as a method of participant selection, as it enabled the researcher to acquire a sample that was articulate, knowledgeable and willing to assist in the research. The questionnaires were then sent to this initial sample population either by email or by physically handing it to the respondents. The initial sample were then requested to distribute the questionnaires to any others that were interested in answering the questionnaire, thus resulting in a form of sampling known as snowball sampling (Lunsford & Lunsford 1995:110).

3.2 Data analysis

Once the data was collected in the form of completed questionnaires, it was analysed using a process known as content analysis. Content analysis is "a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns." (Hsieh & Shannon 2005:1278). According to Kassarjian (1977:10-11), content analysis is particularly suited to research in which there is a lack of relevant data for the researcher, where the opinions and voice of the subjects are of central importance to the research and where the research produces a sufficiently large amount of data for analysis. Thus, content analysis was seen as a suitable tool for the analysis of the research data as the existing information on followership was limited, the voice and opinions of such followers was the central element of the research and a large amount of data was collected due to the sample size and the use of open-ended questions and lengthy questionnaires.

The analysis process began by noticing re-occurring ideas across the entire range of responses within the questionnaires. This was possible as the questionnaire consisted of open-ended questions which are questions that require answers that are more descriptive in nature than simple yes or no answers typical of close-ended questions. These recurring ideas were then assigned particular keywords that encapsulated the essence of the idea in a very succinct manner. Once all the data in the questionnaires had been given keywords (coded), it was possible to view all the codes together, thus facilitating the organisation of such codes into themes. A 'theme' refers to a patterned response (Sandelowski & Barroso 2003:912-913) which indicates to the researcher, the main issues emerging from the raw data. Such themes were then organized according to similarity and refined to capture the essence of the keywords from which they were derived, thus forming the basis of the discussion below.

4. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

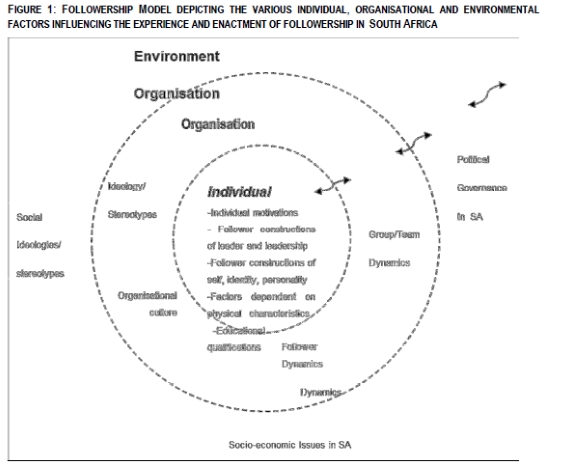

A variety of factors were identified as exerting an influence on followers in South Africa. Such influences were identified as stemming from the individual followers, as well as the organisational and environmental contexts in which they were embedded. Since all of these factors were inter-related in the sense that they influence one another, they were incorporated into the model in Figure 1.

Based on the number of individual, organisational and environmental factors identified as influencing followership, it is important then to conceive of the follower as a whole person, embedded in an organisation and in an external world that influences who they are, how they think, how they act, how they perceive themselves, how they perceive their roles and duties and everything else relating to how they live and experience the world of which they are a part. Following this logic, it would be easy to see how followership cannot be viewed as an isolated phenomenon dependent on the characteristics of the individual follower alone. To do so would reveal only one layer or dynamic of the followership experience, while ignoring the organisational and environmental factors that surely impact upon it as well. This has contributed to the development of a Followership Model from a systems perspective (above) to present a more holistic understanding of the dynamics that contribute to the experience and enactment of followership.

Systems thinking is an approach to understanding the world that arose in the 1950's in the form of General Systems Theory, and which has today spawned a variety of theories and practical approaches, all incorporating the essence of systems thinking (Chapman 2004:34). Systems thinking is based on the recognition of the whole as comprised of multiple parts whose interactions influence the behaviour of the whole (Johnson 1997:8-11). The emphasis is not on each of these systems alone, but rather on how they interact and influence each other within a cohesive whole.

Viewing the South African followership experience through a systems thinking framework seems more apt than attempting to focus on individual aspects of followership in isolation from the others, because it is the interaction of all individual, organisational and environmental factors collectively that contributes to the unique experience that is the South African followership experience. Followership therefore is the outcome of a complex array of interactions between three systems: that of the individual, organisation and the environment.

As can be seen from the diagram (Figure 1), the individual follower is embedded within an organisational system, which is then embedded in an environmental system. The dashed line around each system (or circle) is meant to indicate the openness of each system to the influence of the other systems. Therefore, the individual follower is subject to influences from the organisation in which they work, which in turn is subject to the influence of the larger context (or environment) in which the organisational system (and thus, the follower) is embedded. In this way, environmental or contextual influences are able to impact not only on the organisation, but also on those working in such organisations as well. Thus, each system is not closed off to the other systems, but rather they function in interaction with one another resulting in feedbacks and 'feedforths'. Thus, for example, it is possible for the work environment (organisational factor), to influence the follower's sense of wellbeing (individual factor), but is also possible for the followers' sense of collective wellbeing to influence the state of the work environment. This goes back to the essence of systems thinking by drawing on the idea of systems as capable of influencing, and being influenced by, other systems in dynamic, non-linear ways. This dynamic and non-linear influence is represented in the diagram by the following symbol:

In addition, the outer-most system labelled 'environment' contains the above symbol radiating outwards from it. This is meant to show the existence of influences on followership that come from beyond the South African context. This pertains to international trends and phenomena that impact on South African followership and organisational life. Each of these systems shall be explained below.

4.1 The individual system

The innermost system is labelled as 'individual follower' and thus, represents factors related to the follower as a separate being or individual. Against the backdrop of the emergent data, this can be understood as the factors arising from the individuals themselves which play a role in their experience and enactment of followership. In the findings from the data such factors could be summarised as follows:

• Individual motivations: the factors motivating the individual follower to follow the leader and perform their respective roles and duties in the organisation.

• Follower constructions of leader and leadership: which includes the mental processes by which the follower perceives and interprets the notion of leadership, as well as how they perceive and interpret the behavior and attitude of those who lead them.

• Follower constructions of self, identity and personality: are factors relating to the mental processes by which the individual follower perceives, interprets and develops their sense of self and identity; as well as the influence on their personality, and the influence of their personality on this process of self and identity formation.

• Educational qualifications: refers to the level of education of the follower and their qualifications with regard to their positions in the workplace.

• Factors dependent on physical characteristics: of the follower, including the race, gender, religious or cultural background and language of the follower.

4.2 The organisational system

The organisational system is comprised of all factors influencing, and influenced by, the individual followers in relation to particular dynamics within the organisation such as:

• Leader dynamics: which pertains to the state of leadership within a particular organisation, the type of leaders governing the organisation, the relationship between leaders and followers and the manner in which the leader perceives his/her followers

• Group and team dynamics: within the organisation, or the manner in which all the followers in an organisation communicate, collaborate, interact and collectively construct perceptions and norms of the leader, as well as of 'effective leadership' and 'effective followership'.

• Follower dynamics: within the organisation including the treatment and attitude of the leader towards followers, their level of involvement in decision making, the intensity of work demand on the followers and whether or not they are given an opportunity to support or to object to their leader/s.

• Organisational culture: or the culture pervading the workplace including the rules and regulations in the workplace, opportunities for further training and education, the level of multiculturalism and tolerance for different cultures, levels of respect for each other, the extent to which the organisational culture supports or opposes challenging the leader, etc.

• Ideology/stereotypes: collectively created or reinforced within the workplace, and often emanating from the wider social domain (or the environmental system). These could be directed at the followers or/and the leaders of the organisation and could result in discriminatory behaviour on the basis of such stereotypes or ideologies.

These factors influence the individual followers in the organisation, but the followers can also influence the dynamics within the organisation as well. In addition, the organisational system is also subject to the influence of, and influences, the environmental system in which it is embedded. The factors influencing, and influenced by, followership which arise from the organisational system will differ from organisation to organisation, thus influencing the experience and enactment of followership in those organisations in different ways.

This explains why some organisations can weather change, while others are overcome by it. This could also explain why it is so difficult to apply the recipes of success used by one organisation, to another; because such organisations can never replicate the successful organisation in every aspect due to the huge amount of complexity and uniqueness of its individual, organisational and environmental systems. This also makes defining 'best practices', in terms of the management of organisations, extremely difficult, as each organisation (as well as the followers that comprise the organisation, and the environment in which it is embedded), is unique from all others.

4.3 The environmental system

The environmental system in the diagram is depicted by the outermost circle and refers to all factors that influence the organisation, and those in it, and which emanates from outside the organisation or the context in which an organisation is embedded. Since this study was based on South African followers, the factors influencing followership and emanating from the environmental system will pertain to the South African context. Therefore, this included:

• Political governance in SA: encompassing the legacy of Apartheid, the current democratic political structure in SA, the past and present leadership, leaders and governance of SA, laws, legislations and policies emanating from such governance, and the consequences of all these factors for followership and followers in SA.

• Socio-economic issues in SA: such as poverty, crime, multiculturalism, etc. and the consequences for followership and for the organisation.

• Social ideologies/ stereotypes: in SA, but also emanating from the international arena, while being collectively accepted and reinforced by South Africans, including ideologies and stereotypes relating to gender, race, culture, religion and education that influence the dynamics of followership and leadership within the organisation specifically, and in greater society generally.

According to Senge, Lichtenstein, Kaeufer, Bradbury and Carroll (2007:51), the environment is especially important in determining the health of a business, as businesses, no matter how efficient, will not be able to fare well in unhealthy social or environmental systems. The systems Followership Model depicted earlier was also formulated on the basis of the complexity of inter-relatedness identified in the data.

Even though an attempt was made to identify distinct and separate influences on followership, this was not possible as all of the factors identified as exerting an influence on the experience and enactment of followership were somehow linked to other factors. This provided support for the construction of a model that assessed the followership experience in a holistic manner. In this regard, the systems framework was chosen for drawing all the individual, organisational and environmental factors identified from the data into one cohesive whole.

5. IMPLICATIONS FOR LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT

The issue of leadership and management emerged several times throughout the data, as a significant motivating factor for followers. This provides evidence for the inherent inter-connectedness between leadership and followership, and consequently between leaders/managers and their followers. Thus, it is important to view followership and leadership as interacting and dynamic phenomena that exist in collaboration with one another, instead of as separate, in which leadership and the role of the leader or manager takes precedence over followership, and the role of followers. This is especially important in current times in which there is still a tendency to glorify leaders at the expense of recognizing and understanding the people who choose to follow such leaders.

With regard to the Followership Model described earlier, this inter-connected understanding of followership and leadership can be accommodated within such a model as the organisational system (in which leadership and the leader exist), is not separate or closed off from the individual system, These two systems are open to the influence of each other, thus accommodating the idea of leadership and followership as existing and adapting in response to each other (and the environment).

The study recorded a significant preference for leadership roles and duties over followership roles and duties. This reveals the perception among such followers that following is less worthy and significant than leading. The personal perceptions and interpretations with regard to what constitutes 'leadership roles and duties' played a significant role in determining whether or not they would perceive of themselves as equipped for such roles and duties, with an overwhelming number choosing the position of leader over that of a follower. However, their personal perceptions of leaders as having greater power and influence, and their subjective interpretations of the meaning and essence of 'power' and 'influence', were more influential in their assessment of themselves as future leaders. This is supported by Meindl's (1995:330) assertion that leadership is a social construction. Therefore, followers are more influenced by their personal perceptions and interpretations with regard to leadership and the traits/skills possessed by such leaders, rather than the true state of such leadership and the true traits/skills possessed by the leader (Meindl 1995:330-331).

The subjective perceptions of the followers also played a role in their interpretation of what constituted effective leadership, or the qualities of an effective leader. The characteristics of the leader have the capacity positively and negatively to affect the followership experience, according to the data. Once again, this points to the integrated and dynamic nature of the leader-follower relationship. In addition, such a relationship has evolved with changes in the social environment or environmental system in which both followers and leaders, and the organisation are embedded. Whereas, in the past dominant leaders and compliant followers were all that was needed to keep the organisation running, nowadays an entirely different leader-follower relationship is needed to deal with the rapidly changing and complex environment (Chaleff 2008:71).

6. CONCLUSION

Followers are not static entities merely following the orders of their leaders, but rather they are complex, ever-changing, intelligent beings that play an important role in the functioning of contemporary organisations. As can be seen from the proposed model, there are a wide range of factors that influence the experience and enactment of followership in South Africa. Undoubtedly, these factors also influence followers from other parts of the world as well, thus heightening the international relevance of the model. However, a study of how each of these factors influences followership behaviour locally and internationally is not only beyond the scope of this study, but sufficiently complex to warrant extensive years of research.

In addition, it is recommended that future research considers cross-country comparisons of followership dynamics so as to assess similarities and differences in the experience and enactment of organisational followers from around the world. Future research encompassing a larger sample population within South Africa may also be beneficial, especially in assessing the reliability and validity of this study. Since this study was the first in examining followership dynamics in South Africa, any additional research with a similar focus shall be of great importance in contributing to the African followership studies knowledge base.

REFERENCES

AGHO AO. 2009. Perspectives of senior-level executives on effective followership and leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organisational Studies 16(2):159-166. [ Links ]

BAGGALEY S, CARSON M, HAYCOCK-STUART E & KEAN S. 2011. Followers and the co-construction of leadership. Journal of Nursing Management 19 (1):507-516. [ Links ]

BAKER SD. 2007. Followership: the theoretical foundation of a contemporary construct. Journal of Leadership & Organisational Studies 14 (1):50-60. [ Links ]

BAKER SD & GERLOWSKI DA. 2007. Team effectiveness and leader-follower agreement: an empirical study. Journal of American Academy of Business 12 (1):15-23. [ Links ]

BANUTU-GOMES MB. 2004. Great leaders teach exemplary followership and serve as servant leaders. Journal of American Academy of Business 4 (1) 43-151. [ Links ]

BJUGSTAD K, THACH EC, THOMPSON KJ & MORRIS A. 2006. A fresh look at followership: a model for matching followership and leadership styles. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management 73 (1):304-319. [ Links ]

BLANCHARD AL, WELBOURNE J, GILMORE D & BULLOCK A. 2009. Followership styles and employee attachment to the organisation. The Psychologist-Manager Journal 12(1):111-131. [ Links ]

BOYD NG & TAYLOR RR. 1998. A developmental approach to the examination of friendship in leader-follower relationships. Leadership Quarterly 9 (1): 1 -25. [ Links ]

BROWN A 2003. The new followership: a challenge for leaders. The Futurist 36 (2): 68-69. [ Links ]

BROWN AD & THORNBORROW WT. 1996. Do organisations get the followers they deserve? Leadership & Organisation Development Journal 17 (1): 15-10. [ Links ]

CARSTEN MK, UHL-BIEN M, WEST BJ, PATERA JL & McGREGOR R. 2010. Exploring social constructions of followership: a qualitative study. The Leadership Quarterly 21(2010):543-562. [ Links ]

CHALEFF I. 1995. The courageous follower. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. [ Links ]

CHALEFF I. 2003. The courageous follower. 2nd edition. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. [ Links ]

CHALEFF I .2008. Creating new ways of following. In Riggio RE, Chaleff I & Lipman-Blumen J. eds. The art of followership: how great followers create great leaders and organisations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (Wiley Imprint). [ Links ]

CHAPMAN J. 2004. System failure: why governments must learn to think differently. 2nd edition. London: Demos. [ Links ]

CROSSMAN B & CROSSMAN J. 2011. Conceptualising followership: a review of the literature. Leadership 7(4):481-497. [ Links ]

DECHURCH LA, HILLER NJ, MURASE T, DOTY D & SALAS E. 2010. Leadership across levels: levels of leaders and their levels of impact. The Leadership Quarterly 21(1) 1069-1085. [ Links ]

DE SOUSA A. 2011. Freudian theory and consciousness: a conceptual analysis. In Singh AR & Singh SA eds. Brain, Mind and Consciousness: An International Interdisciplinary Perspective 9(1): 210-217. [ Links ]

FIELDS DL. 2007. Determinants of follower perceptions of a leader's authenticity and integrity. European Management Journal 25(3): 195-206. [ Links ]

GILBERT GR & HYDE AC. 1988. Followership and the federal worker. Public Administration Review 48(6):962-968. [ Links ]

GUNN IP 1996. Courageous followership.... letter. Nursing Management 27 (3):3-4. [ Links ]

HURWITZ M & HURWITZ S. 2009. The romance of the follower: part 1. Industrial and Commercial Training 41(4):199-206. [ Links ]

JOHNSON L. 1997. From mechanistic to social systemic thinking: a digest of a talk by Russell L Ackoff. Innovations in Management Series: 1-12. [ Links ]

KASSARJIAN HH. 1977. Content analysis in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research 4 (1): 8-18. [ Links ]

KELLEY RE. 2008. Rethinking followership.In Riggio RE, Chaleff I & Lipman-Blumen J. eds. the art of followership: how great followers create great leaders and organisations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (Wiley Imprint). [ Links ]

KELLERMAN B. 2008. Followership: how followers are creating change and changing leaders. Boston: Harvard Business. [ Links ]

KUPERS W & WEIBLER J. 2008. Inter-leadership: why and how should we think of leadership and followership integrally? Leadership 4(4):443-475. [ Links ]

LUNSFORD TR & LUNSFORD BR. 1995. The research sample. Part 1: Sampling. JPO: Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics 7 (3):105-112. [ Links ]

MEINDL JR. 1995. The Romance of leadership as a follower-centric theory: a social constructionist approach. Leadership Quarterly 6 (3):329-341. [ Links ]

PUGSLEY L. 2010. How to....get the most from qualitative research. Education for Primary Care 21(1):332-334. [ Links ]

ROST J. 2008. Followership: an outmoded concept. In Riggio RE, Chaleff I & Lipman-Blumen J. eds. The art of followership: how great followers create great leaders and organisations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (Wiley Imprint). [ Links ]

SANDELOWSKI M & BARROSO J. 2003. Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research 13 (7): 905-923. [ Links ]

SENGE PM, LICHTENSTEIN BB, KAEUFER K, BRADBURY H & CARROLL JS. 2007. Collaborating for systemic change. MIT Sloan Management Review 48 (2):43-54. [ Links ]

SRONCE R & ARENDT LA. 2009. Demonstrating the interplay of leaders and followers: an experiential exercise. Journal of Management Education 33 (1):699-723. [ Links ]

STECH EL. 2008. A new leadership-followership paradigm. In Riggio RE, Chaleff I & Lipman-Blumen J. eds. The art of followership: how great followers create great leaders and organisations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (Wiley Imprint). [ Links ]

TOWNSEND P & GEBHARDT JE. 1997. For service to work right, skilled leaders need skills in followership. Managing Service Quality 71 (3):36-140. [ Links ]

VAN GILS S, VAN QUAQUEBEKE N & VAN KNIPPENBERG D. 2010. The X-factor: On the relevance of implicit leadership and followership theories for leader-member exchange agreement. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology 19(3):333-363. [ Links ]

ZALEZNIK A. 1965. The dynamics of subordinacy. Harvard Business Review 43 (3):119-131. [ Links ]