Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.10 no.1 Meyerton 2013

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Leadership coaching as a driver of successful organisational change in small businesses: a case study

K OrtleppI; L KinnearII; A KaradisI

IUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal

IILeadership Insight

ABSTRACT

Leadership is one of the critical determinants of an organisation's success in navigating the challenges associated with operating in turbulent times. The nature of the specific leadership approach adopted has a potentially significant impact on an organisation's ability to meet the challenges of a business landscape characterised by continuous change. Leadership coaching is a strategy gaining increasing recognition as a driver of successful organisational change within this broader context of ongoing environmental change. In particular, leadership coaching can be used as an integral part of a strategy to bring about a desired change in an organisation's culture. However, there is a need for increased evidence of the success of leadership coaching initiatives in bringing about such change, at both the individual and group levels, over a long period of time. This case study attempts to make a contribution to this evolving field by demonstrating how leadership coaching at an individual and team level can facilitate successful organisational change in a small-business context.

Key phrases: emotional intelligence, leadership coaching, organisational culture change, organisational development, small business, transformational leadership

1 INTRODUCTION

From large corporations to small businesses, organisations operate in a turbulent environment characterised by global competition, technological innovation and declining resources (Krell 2013:6; Van Tonder 2010:3). Daft (2011:8) observes that "today's world is in constant motion, and nothing seems certain anymore. Leaders are facing challenges they couldn't even imagine a few years ago." In the business environment of the twenty-first century, Daft (2011:8) emphasises that it is an illusion that if leaders just keep things running on a steady, even keel, the organisation will be successful.

Indeed, Van Tonder (2010:9) argues that it is no longer a matter of changing from one organisational state to another in the search for stability, but rather of "living with change" as a natural characteristic of how organisations function in the current business environment. Similarly, Gooding (2005:345) asserts that "successful companies [in the twenty-first century] will be those whose strategy is based on change and continuous improvement." As such, the challenge for organisations and leaders of organisations is to avoid complacency and rather develop a resilient workplace culture in which lifelong learning and change are embraced (Cooper 2005:2).

The above points apply to all organisations operating in the current macro business environment, including small businesses. In fact, it can be argued that the levels of uncertainty and turbulence are exacerbated when considering the small-business context. Nieman (2006:18) emphasises that "the ability of a small business to react to change is what gives these smaller businesses a competitive advantage over their larger, more dominant peers." Within the specific context of small businesses, a study conducted by Blackburn, Hart and Wainwright (2013: 23) showed that the presence of an owner-manager who considered themselves an "innovator" or "creator of change" increased the likelihood of the organisation's growth substantially.

However, management and organisational change experts emphasise that while it is essential for organisations to respond appropriately to this continuously changing business environment, the extent to which they are successful in this is questionable, thus highlighting the complex nature of successful change initiatives in organisations (Kotter 2007:96). In light of this observation Thomas Stewart, the editor of a special edition of the Harvard Business Review, argued in his introductory comments to an article written by John Kotter that "fundamental change is often resisted mightily by the people it most affects: those in the trenches of the business.

Thus, leading change is absolutely essential and incredibly difficult" (Stewart in Kotter 2007:96). Ridderstrale and Nordstrom (2000:33) concur, arguing that leadership is critical in the success of any organisation operating in the current turbulent business environment. More recently, authors such as Bezuidenhout and Schultz (2013:280) have once again highlighted the critical importance of the role of leaders in the successful implementation of organisational change.

However, Kets de Vries (2008:3) emphasises that studies now show that successful organisations are "not those led by one, powerful charismatic leader but are the product of distributive, collective and complementary leadership". This necessitates changes in the organisation's culture that go beyond simple training initiatives targeted at individual leaders and focuses instead on developing multiple leaders in a given situation (Ingleton 2013:220). Accordingly, interventions aimed at developing leaders at various levels, and that therefore create 'leaderful' organisations, are in the best position to "thrive in this brave new world" (Kets de Vries 2008:3). Kets de Vries (2008:4) argues further that this type of cultural transformation is not easy to accomplish, and that leadership coaching can be a catalyst for the creation of the desired cultural environment.

2 PURPOSE AND METHODOLOGY OF THE STUDY

Leadership coaching is fast becoming a recognised practice for leadership development and is emerging as a strategy to be used in facilitating successful organisational change. The industry of leadership coaching has emerged largely to help people through the transition to a new paradigm of leadership most suited to leading organisations in continuously changing environments (Daft 2011:25). However, there is little empirical research on the success of coaching initiatives in bringing about change, at both the individual and group levels, over a long period of time (Fillery-Travis & Lane 2010:62).

The purpose of this article is to report on the design, implementation and review of the effectiveness of an intervention aimed at developing the leadership capacity within a small business undergoing significant change. In this way, the study seeks to contribute to the fields of contemporary management generally, and leadership coaching more specifically, by demonstrating how leadership coaching at an individual and team level can facilitate successful change in organisational culture within a small-business context.

A case study approach is adopted in order to outline the components comprising this practice-led study (i.e. a study that was initiated by the authors in their capacity as organisational development practitioners in direct response to a client's specific needs). By its nature, case-study research is descriptive and can provide a rich, multi-faceted body of information about particular situations (Lindegger 2007:461). According to Lindegger (2007:461), case studies have the advantage of "allowing new ideas and hypotheses to emerge from careful and detailed observation". However, it is acknowledged that causal links in case-study research are difficult to test and generalisations cannot be made from single case studies (Malhotra 2007:82).

This case study focuses on the particular context of Polydynamix (a pseudonym used for the purpose of this paper), a small, family-run organisation that is evolving into one characterised by a stronger emphasis on entrepreneurial activities leading towards increased profitability and growth. The intervention focused on in this case study entailed the application of organisational and leadership development principles and practices to the unique context of the host organisation (Polydynamix).

Evaluation of the intervention was done through the analysis of qualitative and quantitative data collected through interviews and 360-degree questionnaires respectively. Interviews were conducted with the 10 managers involved in the leadership coaching three months after the intervention had been completed. A 360-degree questionnaire was designed by the authors and tailored to the specific areas focused on in the intervention. These questionnaires were completed at the start of the intervention and again three months after the intervention was completed. The responses collected in Time 1 and Time 2 were analysed and compared using simple frequencies.

Given that this paper presents a practice-driven descriptive case study, the material is presented in the following order: background to the organisation; the leadership coaching process including the leadership paradigm underpinning this process; outcomes of the leadership coaching process; and concluding remarks that include implications for managers and recommendations for future research. In this way, the theoretical principles informing the intervention are interwoven with their practical application.

3 BACKGROUND TO THE ORGANISATION

According to the seminal work of Greiner (1998:60), in the birth stage of an organisation the founders of the organisation are usually technically or entrepreneurially orientated, and place little emphasis on traditional management activities. In the birth stage of a small, entrepreneurial, family-run organisation, the owner, who is often a paternal figurehead, personifies the organisation's business identity.

In the context of a small, family-run organisation, employee engagement is generated from close intimate relationships with the founding leadership, informal and personal communication between staff and leaders, employee involvement in the entrepreneurial activities which gave rise to the growth of the organisation, and an acute sensitivity to marketplace feedback and customer demands (Greiner 1998:61). Employee engagement is a key ingredient of organisational success and can be defined as "an individual's involvement with, satisfaction with, and enthusiasm for, the work s/he does" (Robbins, Judge, Odendaal & Roodt 2009:76). A study by Joubert and Roodt (2011:96) showed that leadership has a direct relationship with employee engagement levels in organisations.

A classic transition for entrepreneurial organisations is to second-generation leadership, where parents entrust the leadership of the organisation they established to the next generation (Maas 2008:185). A range of complex dynamics emerges with this transition. In particular, when a small, family-run, owner-led organisation transitions to a larger, more professionally managed enterprise striving for growth and increased profitability, changes in the nature of leadership occur as part of the organisational growth cycle (Greiner 1998:56; Maas 2008:186). These principles apply to Polydynamix, the organisation that forms the focus of this case study.

Polydynamix is a South African reprographics organisation that was founded by the owner in the late 1980s and has become a prominent player in the packaging and printing sector of this industry over the past two decades. At the time of the leadership coaching intervention the organisation employed 63 people and offered a wide range of services that included designing, proofing and producing flexographic printing plates for printing on a variety of surfaces.

The founder-owner of Polydynamix retired and the leadership of the organisation was transferred to the founder's son, who took on the role of managing director (MD) at a critical growth point in the organisation's life cycle. Building on the solid foundations laid by the founder-owner, the new MD identified opportunities to grow the organisation in different directions. This marked a new phase of expansion and acquisition, including the introduction of innovative technology to add to the organisation's traditional service offering. With the expanded focus and the new leadership, a different leadership style was an inevitable result of the transition.

The second-generation leadership understood that with this growth it was no longer possible to rely on a single person for the entire organisation's leadership. Leadership needed to be shared and new management practices needed to be employed, resulting in a shift in the traditional methods of employee engagement. Personal relationships with the founding leader could no longer be relied on as the primary channel of communication, or to ensure employee motivation and commitment. The expansion of management responsibilities to other members of staff, and the MD's taking on a more strategic and less operationally involved role, necessitated new ways of engaging with employees to meet the new challenges and opportunities facing the organisation. At the same time, the motivation, commitment and customer focus that had been key to the success of Polydynamix in its infancy had to be retained.

4 LEADERSHIP COACHING AND ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE

To enable the transition to a new phase of the life cycle of Polydynamix as an organisation, and to enhance employee engagement through new forms of shared leadership, a process involving leadership coaching and changes in the organisational culture was initiated by the MD. The services of the authors of this paper, who have experience in organisational change, team development and leadership coaching, were contracted to design and facilitate the change initiative over a year-long period. The process involved the formation and coaching of a leadership team, both at a group and individual level.

The objective of the initiative was to create greater responsibility, accountability and capacity for leadership amongst a team of managers who had formerly supervised the organisation's activities under the direct leadership of the owner-founder. The coaching of the individual leaders and leadership team was connected to the broader organisational transformation goal of creating a leadership culture that retained elements of the organisation's entrepreneurial success while building professional leadership capability to deal with the complexities of a growing enterprise in a technologically advancing industry.

4.1 Leadership coaching

Leadership coaching can be described as a personalised, one-on-one process aimed at helping the managers/leaders achieve specified results for their employer and personal growth for themselves (Biswas-Diener 2010:5; Schwarz & Davidson 2009:80). Palmer and Whybrow (2010:2) explore numerous definitions and forms of coaching, and emphasise that leadership coaching is a facilitated process of unlocking a person's potential to maximise their own performance as well as that of their team members. Kets de Vries (2008: 4) describes leadership coaching as an intervention that is carried out strategically with individuals and/or teams to direct people towards a specific, mutually determined goal.

Furthermore, the focus of leadership coaching within the context of an organisation striving to reinvent itself, as was the case with Polydynamix, places considerable emphasis on principles and behavioural strategies linked to 'transformational leadership' an approach to leadership originally developed by Bass (1990). According to Odetunde (2013:5324) transformational leaders tap into followers' motives and seek to engage them to move beyond their self- interests for the benefit of the group and the organisation. Transformational leadership has its roots in behaviours and attitudes inherent in the concept of "the leader as servant" (Van Rensburg 2010:70).

According to Daft (2011:156), "servant leadership is leadership upside down. Servant leaders transcend self-interest to serve the needs of others, help others grow and develop, and provide opportunity for others to gain materially and emotionally." Transformational leadership has been found to have a positive direct impact on innovation, growth and profitability (Matzler, Schwarz, Deutinger & Harms 2008: 147) as well as employee engagement (Bezuidenhout & Schultz 2013: 294). Kouzes and Posner's (2007) description of exemplary leadership relates to the conceptualisation of leadership as transformative, and refers specifically to the context of organisational change. For them, exemplary leaders:

• Model the way - by setting the example by aligning their personal actions with shared organisational values;

• Inspire a shared vision - by enlisting others in a common vision by appealing to shared aspirations;

• Challenge the process - by constantly searching for opportunities to change, improve, and learn from mistakes;

• Enable others to act - by fostering collaboration by building trust, sharing power and promoting co-operative goals; and

• Encourage the heart - by recognising and appreciating individual contributions and celebrating progress in line with the shared vision.

Emotional intelligence is a key ingredient of transformational leadership (Yitshaki 2012:358). The development of the manager's emotional intelligence forms a key aspect of the coaching process when viewing leadership from the above perspective. Emotional intelligence can be defined as "the ability to manage ourselves and our relationships effectively" (Goleman 2000:80). It typically entails developing a leader's self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills (Goleman 1998:94). Leadership coaching within this context is therefore about "helping the people who are being coached to reach a fuller potential - a point at which they not only know themselves better, but also feel comfortable with who and what they are" (Kets de Vries 2008:4).In addition, according to Millar (2012:14) it is through emotional intelligence that leaders learn to manage relationships, build creative teams and motivate others, all of which contribute to enhanced employee engagement.

4.2 The change process

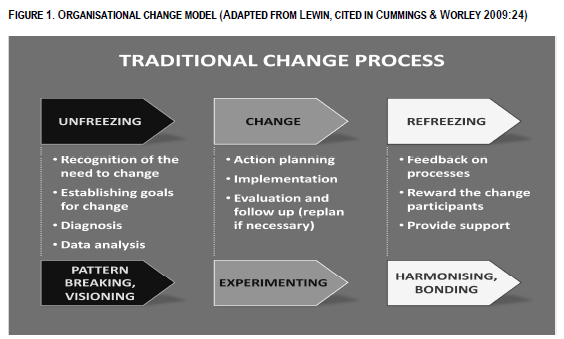

In the design and execution of the change process at Polydynamix, the authors followed the general change principles outlined in the models of Lewin (cited in Cummings & Worley 2009:564) and Kotter (2007:99), as depicted in Figure 1.

The change process outlined in Figure 1 informed the process followed in the specific intervention designed and implemented in this case. It is acknowledged that Lewin's model is not without limitations yet the underlying principles in the model form the foundation for many of the more advanced models of organisational change and still have relevance today (Van Tonder 2010: 207). Van Tonder (2010:207) goes so far as to state "While this change model represents an exceedingly reductionist concept of change, it is nonetheless a valid (although primitive) account of the most fundamental change dynamic."

Furthermore other recent organisational change initiatives have used Lewin's model as a foundation on which to base the design of the change intervention (Hashim 2013: 691). As such, in this current case study, Lewin's model, together with that of Kotter (2007:99), were used by the authors in the design phase of the organisational change intervention.

However, in practice, the change process is not a simple linear one, as organisations are complex, dynamic systems (Roodt & Van Tonder; 2008:44). In order to engage with the complexity inherent in the dynamic organisational context, the change initiative included regular feedback and review points in its execution.

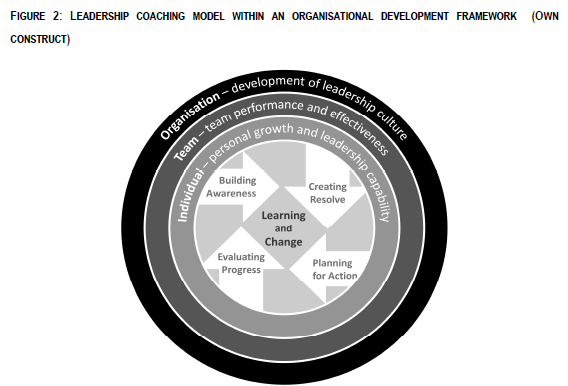

Describing the process broadly, the change initiative aimed at intervening at the individual leadership level (through leadership coaching) as well as intervening at the team level (through team coaching). By targeting interventions at these two levels, the process aimed to bring about a comprehensive change in the broader organisational culture of Polydynamix. This multi-layered approach is depicted in Figure 2.

A description of the relevant components of the model depicted in Figure 2 follows, and in this way the process adopted by the authors is explained.

4.2.1 Building awareness

The initial diagnosis of the organisational culture was conducted with a team of 10 potential leaders who were selected from a staff of 63, and who were to play a key role in taking the organisation forward. They were engaged in discussions on key aspects that needed to shift for the organisation to continue to sustain itself and grow. The diagnostic phase indicated not only that Polydynamix could no longer rely on a single person to lead, but also that due to the employees' personal affiliation with the founding leader, the new leader was regarded with a certain amount of distrust. Based on the information gathered, a process was designed to facilitate the change, and more effective employee engagement with leadership became a necessary outcome of the process.

The overall aim of the process was to ensure that leadership was developed at a variety of levels in the organisation, so that members of the leadership team at Polydynamix developed the following skills and attitudes:

• A greater awareness of their leadership style and its impact on the people they lead.

• The ability to modify their style in interacting with others to create more effective results.

• The ability to inspire and motivate the teams they lead effectively.

• A knowledge of best-practice principles related to leadership and management.

• A commitment to a common direction and the ability to communicate that direction to the people they lead.

The first phase of the process focused on developing a shared leadership culture. This was done at both an individual and team level.

Self-awareness at an individual level was raised by conducting psychological assessments, 360-degree feedback and reflecting on life experiences with a professional leadership coach in a number of one-on-one sessions.

Team awareness was raised at a team level by sharing assessments in facilitated workshops in order to understand the team dynamics. Team feedback was given to identify team strengths and developmental gaps. The individual and team processes ran in parallel so that alignment was created between organisational culture, team effectiveness and individual leadership development.

The leadership-coaching initiative was based on a process-oriented approach to coaching. As explained by Cummings and Worley (2009:253) process consultation was first introduced by Schein (1987). Process consultation encourages clients to gain greater insight into what is going on around them (in terms of both interpersonal and intrapersonal dynamics as related to their leadership roles) and to utilise this insight to improve the situation to meet their personal, team and organisational goals (Cummings & Worley 2009:156; Schein 1987:9).

Process consultation emphasises the active involvement in the ongoing diagnosis of a situation as well as in the design and implementation of problem-solving approaches to achieve their desired goal (Cummings & Worley 2009:254). The principles postulated by Schein are reinforced and integrated into the more recent works of others in the field of coaching and organisation development (e.g. Cummings & Worley 2009; Roodt & Van Tonder 2008; Schwarz & Davidson 2009; Van Tonder 2010).

Inherent in this approach is the inclusion of the organisation's leadership in co-designing and championing the process (Cummings & Worley 2009:254). In the current intervention, the fact that the management team members were encouraged to offer input into the design of various aspects of the process, such as the 360-degree feedback questionnaire, ensured their support and engagement. Equally, continuous feedback on trends emerging from the individual coaching and team workshops stimulated continuous learning and change in line with the transforming leadership culture.

4.2.2 Creating resolve and planning for action

The team workshops and individual coaching sessions encouraged a sense of leadership resolve, as the team committed to a shared vision and set of values for Polydynamix, and the individuals committed to working on a number of critical developmental areas. Institutionalising the new leadership culture was achieved through implementing action plans.

Individual leadership development plans identified action strategies, time frames and evaluation methods, while team strategies expanded to involve improving or implementing new organisational systems and processes. Strategic goals, aligned to the organisation's vision and values, were identified for the leadership direction at Polydynamix. Roles and responsibilities were defined to empower leaders to operate within their area of responsibility, to identify communication channels and to highlight the nature of the co-operation needed between roles.

Based on an emerging need, these leader/managers were also trained in the necessary skills to manage the performance of their teams.

4.2.3 Evaluating progress

Evaluation of the leadership coaching initiative was ongoing throughout the process, with regular informal feedback discussions between the organisational leadership and consultants. Furthermore, a more formal evaluation was conducted 12 months after completion of the initial intervention by an external party (i.e. someone not involved in the design and execution of the intervention) to ensure a lack of bias.

The evaluation aimed at establishing the success of the transformation of the leadership culture at Polydynamix as well as providing impetus for continued embedding of new leadership behaviours. Qualitative data were gathered through a series of interviews conducted by the independent data gatherer, who interviewed the senior leadership and newly constituted management team.

Furthermore, quantitative data were gathered through another 360-degree feedback questionnaire on leadership behaviours, which allowed for a comparison of results before and after the initiative. The increase in sales figures and profitability at Polydynamix over the intervention period was viewed as only one possible indicator of success, but could not be attributed directly to the results of the initiative, since a range of variables influence this measure.

5 RESULTS OF THE INITIATIVE

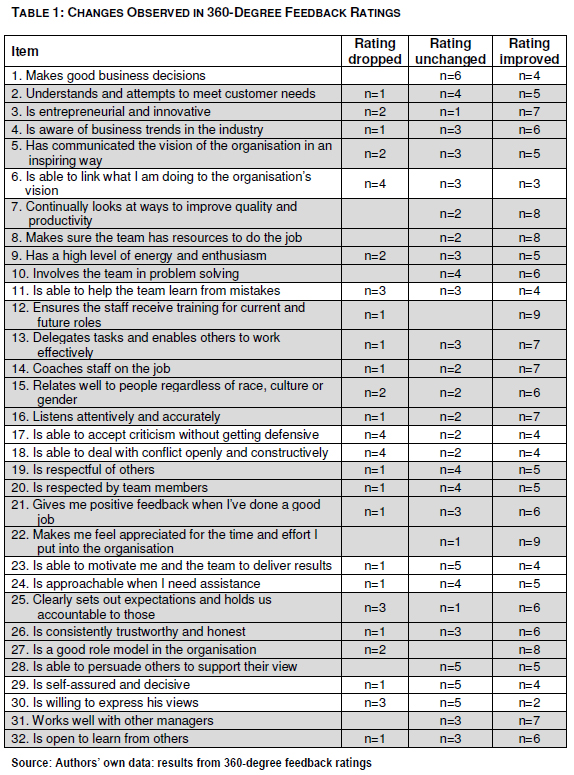

Table 1 outlines the changes recorded in the second round of 360-degree feedback. Each of the items is listed together with the incidence of the number of cases in which the ratings between Time 1 and Time 2 dropped, remained the same or improved. The highlighted items indicate where five or more participants indicated a positive change in that particular area.

The qualitative data gathered through independent interviews showed that the newly formed management team at Polydynamix benefited as a team in the following significant ways:

• Getting the whole team involved in where the organisation was going.

• Improving teamwork between and within business units.

• Being able to discuss issues and problems openly.

• Learning about other people on the team.

• Deepening the understanding and appreciation of individual team members' differing responses to shared challenges.

From the interviews it was found that individual coaching provided the following key benefits to individuals:

• Improved self-awareness and awareness of others.

• A deeper appreciation of personal roles played in influencing the team dynamics.

• An understanding of what it takes to be an effective leader.

• Improved skills in people management.

• An increased ability to speak out in public and handle confrontation constructively.

• Personal growth, which in certain individuals extended to their roles outside of the workplace.

These findings indicate that the initiative succeeded in meeting, and even exceeding, the initial objectives of the leadership coaching process. The MD summarised this as follows: "My objectives were to form a management team structure, to have guys be accountable and responsible, aligned and operating together, so I think all of these objectives have been met and more."

The qualitative interviews also examined the sustainability of the change in leadership culture. Most respondents acknowledged that they apply what they have learnt every day, with some indicating that while they try to implement what they have learnt, they find it difficult due to the pressure of their role.

Constant feedback, individual commitment and reinforcement from the MD and the performance-management systems were seen to be critical factors that would need to continue in order to sustain the change in leadership behaviours.

As is the nature of organisational development, further team and individual needs were identified through the evaluation, and the process was extended and adapted in response to the emerging needs. In particular, the 360-degree feedback indicated the need for more focused attention on areas such as the managers' conflict-resolution skills and their performance-management skills. This led to training initiatives in these areas being introduced as well as the introduction of a performance-management system tailored to the unique needs of the organisation.

6 CONCLUSION

The success of this intervention is reflected in the following observation from the MD of Polydynamix:

This intervention has helped to build our teamwork in our organisation. In our industry, this is what separates us from our competitors. It has helped to align the thoughts of the management team with the direction of the organisation. The program has enhanced the synergy and expanded the roles and responsibilities of our staff.

The results of the change in leadership culture at Polydynamix illustrate a shift in the means of achieving employee engagement from the initial personal identification with the founder leader of the organisation, to engagement as a team with the strategic direction of the organisation, as inspired by the MD and reinforced by each person in the leadership team.

The data reveal that commitment on the part of employees to the organisation and its strategic direction is achieved through empowerment, trust, collaboration and shared leadership. Increased responsibility and accountability of the newly formed leadership team may have been the overt goal of the MD in embarking on the leadership coaching initiative, but the increased engagement of employees, through developing leadership capability, was specifically highlighted both in the team of 10 individuals who participated in the process and in the employees' feedback to them through the 360-degree process. It is well documented that employee engagement results in improved overall performance of individuals and organisations (Robbins et al. 2009:96). Indeed, Dessler, Barkhuizen, Bezuidenhout, De Braine, Du Plessis, Nel, Stanz, Schultz & Van Der Walt (2011:617) state: "The business case for employee engagement is clear - leaders and managers who inspire and engage their employees are more likely to realise the full potential of their workforce, unlocking hidden talent and maximising business performance."

Drawing on the insights from the design, implementation and evaluation of this intervention, the following specific implications are evident:

• Successful changes in organisational culture and enhanced employee engagement can be achieved by utilising leadership coaching as one of the key driving strategies.

• The effectiveness of leadership coaching is enhanced when the process and key areas to be focused on in the coaching are designed to be in alignment with the particular organisation's specific needs and challenges.

• Evidence from this case supports the strategy of connecting leadership coaching to the broader objectives of the proposed organisational change initiative as opposed to a stand-alone leadership development strategy.

• Leadership coaching facilitated at both the team and individual levels enhances alignment, sustainability and overall achievement of distributive leadership.

• Continuous feedback and leadership involvement (key principles underlying process consultation) are critical to the systemic and long-term success of a change initiative.

The value of this type of intervention as a significant resource to small businesses striving to succeed in the ever-changing business environment is thus clearly evident. However, it is recommended that further empirical evidence relating to the efficacy of coaching as a strategy for facilitating successful change at the personal, team and organisational levels is gathered through the collaboration of practitioners and researchers in this field. This empirical research needs to incorporate principles of sound research methodology, involving explicit longitudinal pre-test and post-test research design. In this way, the data gathered from the evaluation stage of an intervention such as that described in this case study, can be subjected to more robust analysis upon which firm conclusions can be even more strongly supported.

REFERENCES

BASS BM. 1990. From transactional to transformational leadership: learning to share the vision. Organisational Dynamics 13(3):26-40. [ Links ]

BEZUIDENHOUT A & SCHULTZ C. 2013. Transformational leadership and employee engagement in the mining industry. Journal of Contemporary Management 10:279-297. [ Links ]

BISWAS-DIENER R. 2010. Practicing positive psychology coaching. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Wiley. [ Links ]

BLACKBURN RA, HART M & WAINWRIGHT T. 2013. Small business performance :business, strategy and owner-manager characteristics. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 20(1):8-27. [ Links ]

CHARAN R. 2009. The coaching industry: a work in progress. Harvard Business Review 93-98, January [ Links ]

COOPER CL. 2005. Introduction. In COOPER CL (ed). Leadership and management in the 21st century: Business challenges of the future. New York: Oxford. pp. 1-18. [ Links ]

CUMMINGS TG & WORLEY CG. 2009. Organization development and change. Stamford: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

DAFT RL. 2011. Leadership. 5th ed. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

DESSLER G, BARKHUIZEN N, BEZUIDENHOUT A, DE BRAINE R, DU PLESSIS Y, NEL P, STANZ K, SCHULTZ K & VAN DER WALT H. 2011. Human resource management: global and southern African perspectives. Cape Town: Pearson. [ Links ]

FILLERY-TRAVIS A & LANE D. 2010. Research: does coaching work? In PALMER S & WHYBROW A (eds). Handbook of coaching psychology: a guide for practitioners. New York: Routledge. pp. 57-70. [ Links ]

GOLEMAN D. 1998. What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review: 93-102, November-December: [ Links ]

GOLEMAN D. 2000. Leadership that gets results. Harvard Business Review: 78-90, March-April. [ Links ]

GOODING V. 2005. What will tomorrow's organization look like over the next couple of decades? In COOPER CL (ed). Leadership and management in the 21st century: Business challenges of the future. New York: Oxford. pp. 344-354. [ Links ]

GREINER LE. 1998. Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harvard Business Review. 55-67, May-June. [ Links ]

HASHIM M. 2013. Change management. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 3(7):685-694. [ Links ]

INGLETON T. 2013. College student leadership development: Transformational leadership as a theoretical foundation. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 3(7):219-229. [ Links ]

JOUBERT M & ROODT G. 2011. Identifying enabling management practices for employee engagement. Acta Commercii 11:88-110. [ Links ]

KETS DE VRIES M. 2008. Leadership coaching and organizational transformation: effectiveness in a world of paradoxes. [Internet: http://www.insead.edu/facultyresearch/researc/doc.cfm?did=38545; downloaded on 15 July 2013. [ Links ]]

KOTTER JP. 2007. Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review Special Edition (Best of HBR: The tests of a leader),:96-103 January. [ Links ]

KOUZES J & POSNER BZ. 2007. The leadership challenge. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

KRELL E. 2013. Exploring what it takes to lead in the 21st century. Baylor Business Review Spring:5-8. [ Links ]

LINDEGGER G. 2007. Research methods in clinical practice. In TERREBLANCHE M, DURRHEIM K & PAINTER D (eds). Research in practice. Cape Town: UCT Press. pp. 455-475. [ Links ]

MAAS G. 2008. Entering the family business. In NIEMAN G, HOUGH J & NIEUWENHUIZEN C (eds). Entrepreneurship: a South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik. pp. 181-193. [ Links ]

MALHOTRA NK. 2007. Marketing research: an applied orientation. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pearson. [ Links ]

MATZLER K, SCHWARZ E, DEUTINGER N & HARMS R. 2008. The relationship between transformational leadership, product innovation and performance in SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 21(2):139-151. [ Links ]

MILLAR M., 2012. Walking the walk. Training Journal: 12-16, November. [ Links ].

NIEMAN G. 2006. Small business management: a South African approach. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

ODETUNDE OJ. 2013. Influence of transformational and transactional leadership and leaders' sex on organisational conflict. Gender and Behaviour 11(1 ):5323-5335. [ Links ]

PALMER S & WHYBROW A. 2010. Handbook of coaching psychology: A guide for practitioners. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

RIDDERSTRALE J & NORDSTROM K. 2000. Funky business: talent makes capital dance. London: Pearson. [ Links ]

ROBBINS SP, JUDGE TA, ODENDAAL A & ROODT G. 2009. Organisational behaviour: global and South African perspectives. Cape Town: Pearson. [ Links ]

ROODT G & VAN TONDER CL. 2008. Central features: change process, values and systemic health. In VAN TONDER CL & ROODT G (eds). Organisation development: theory and practice. Pretoria: Van Schaik. pp. 39-60. [ Links ]

SCHEIN EH. 1987. Process consultation. New York: Addison Wesley. [ Links ]

SCHWARZ D & DAVIDSON A. 2009. Facilitative coaching. San Francisco: Pfeisser. [ Links ]

SCHULTZ C, STANZ K & VAN DER WALT H. 2011. Human resource management: global and South African perspectives. Cape Town: Pearson. [ Links ]

VAN RENSBURG G. 2010. The leadership challenge in Africa. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

VAN TONDER CL. 2010. Organisational change: theory and practice. Cape Town: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

YITSHAKI R. 2012. How do entrepreneurs' emotional intelligence and transformational leadership orientation impact new ventures' growth? Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 25(3):357-374. [ Links ]