Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.10 no.1 Meyerton 2013

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Towards gaining a competitive advantage: the relationship between burnout, job satisfaction, social support and mindfulness

H Abdool Karrim IsmailI; N CoetzeeII; P Du ToitII; EC RudolphIII; YT JoubertIII

IUniversity of Johannesburg

IIUniversity of Pretoria

IIIUniversity of South Africa

ABSTRACT

The prevalence of burnout has increased in the past 30 years. A review of the literature suggested that burnout could be prevented through the application of interpersonal as well as intrapersonal strategies. Interpersonal strategies consist of employees having access to social support systems and human resources management's ability that may have a positive influence on job satisfaction. Intrapersonal strategies take the form of training individuals to become mindful, thus being aware of their physical as well as psychological states. Little research has been conducted on the successfulness of such strategies and the need was identified to explore the relationship between burnout, job satisfaction, social support and mindfulness among employees in a South African corporate organisation. The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between burnout, job satisfaction, social support and mindfulness within a South African corporate organisation. The study was a quantitative study and a correlational research design was used. Systematic random sampling was used to compile the sample. The sample consisted of 209 employees working in a financial corporate environment in Johannesburg. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed for burnout, job satisfaction, social support and mindfulness. Moderate to strong inverse correlations were discovered among the constructs under investigation. Thereafter, a multiple regression analysis was deemed necessary to determine which of the independent variables (mindfulness, job satisfaction and social support) contributed significantly to explaining the variance in burnout scores. All the constructs (job satisfaction, mindfulness and social support) appear to be significant predictors of burnout. Job satisfaction displayed the highest beta value whilst mindfulness scored the second highest beta value in the multiple regression analysis.

Key phrases: burnout, job satisfaction, mindfulness, social support

1 INTRODUCTION

In a study conducted on burnout, Abdool Karrim Ismail (2010:1-3) noted that the prevalence of burnout had increased over the past 30 years. Pruessner, Hellhammer and Kirschbaum (1999:197) believed burnout is the result of exposure to chronic stress in the workplace. Maslach (1982:3) described burnout as "a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and reduced personal accomplishment" that occur among employees. Although burnout was mostly investigated among individuals employed in the social services (Abdool Karrim Ismail 2010:12; Wright, Banas, Bessarabova & Bernard 2010: 375), Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli (2001:499) found that it can occur in any workplace setting. It is against this background that South African research on burnout from 1996 until 2009 focused on the following professions: police services, education in secondary and higher institutions, the nursing profession, medical practitioners, hospice workers, the hospitality industry, social worker and the clergy (Abdool Karrim Ismail 2010:1).

Burnout has been associated with impaired job performance, employee turnover, high absenteeism and poor health such as anxiety, headaches, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbances, irritability, marital difficulties, exhaustion and so forth (Griffin et al. 2010:239; Spickard, Gabbe & Christensen, 2002:1447; Wright et al. 2010:375). In addition, it also decreases employees' willingness to provide quality services within the workplace (Kara, Uysal, Sirgy & Lee 2013:11).

Because it is expected of modern day organisations to support their employees and to ensure a safe and healthy working environment, human resources management is facing the challenge to implement strategies that will prevent or counter the effects of burnout (Grobler, Warnich, Carrell, Elbert & Hatfield 2002:466). When reviewing the literature on burnout, two constructs constantly emerge as factors that could prevent burnout from occurring. These are social support and job satisfaction (Abdool Karrim Ismail 2010:84-112; Demerouti et al. 2001:501; Griffin et al. 2010:239; Kinman, Wray & Strange 2011: 844-846; Wright et al. 2010:375). Because these constructs focus on factors situated in the immediate, personal environment of the employee, it could be labelled as 'interpersonal strategies'.

Abdool Karrim Ismail (2010:49) and Lindfors (2012:309), however, contended that, in order for interpersonal strategies to be successful in countering burnout, employees should also be taught how to become more aware of the interaction between their internal physical and psychological states when experiencing job satisfaction and social support. These authors have noted that employees' awareness of the existence of such strategies should be meaningful in order to prevent burnout from occurring. One way of achieving awareness is by enhancing employees' mindfulness (Bond & Bruce, 2000:156-163). Since mindfulness relates to a process that will happen within the employee, it is labelled as an 'intrapersonal strategy'.

For the purposes of the present study it is thus suggested that, in addition to interpersonal strategies, intrapersonal strategies should be employed to prevent and/or counter the effects of burnout. Since there is a need in South Africa to recommend interpersonal and intrapersonal strategies to prevent burnout, the primary aim of the study was to determine if relationships exist between burnout, mindfulness, job satisfaction and social support.

In addition to this primary aim, three objectives were set. The first objective was to establish, in the event that relationships exist between burnout, mindfulness, job satisfaction and social support, the strength and direction of such relationships. The second objective was to determine which of the constructs (mindfulness, job satisfaction and social support) contributed the most to the prevention of burnout. The third objective was related to the instruments used in the current study. Since all these instruments were standardized for use in the international domain, the third objective was to determine their reliability within the South African context before any data analyses were performed.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Mindfulness

Mindfulness was developed 2 500 years ago by the Buddhists and is defined as "moment-to-moment awareness" (Kabat-Zinn 2008:66). It is a tradition that is meant to help people to live and accept each moment of their lives (even the painful ones) as fully as possible in a non-judgemental way (Brown & Ryan 2003:22; Kabat-Zinn 1994: 4). Mindfulness is used mainly within a positive psychological paradigm. Burnout influences employees in such a way that they are unable to function in their jobs (Vallen 1993:55) and result in great losses in terms of productiveness, absenteeism and employee turnover each year for organisations. Mindfulness is a form of meditation that is used to develop good acumen (judgment). It is furthermore linked to emotional intelligence with the intention to self-regulate attention and awareness (Lawson 2011:1).

Mindfulness within the organisation could thus be used to make employees more aware, or to help them focus on, the positive aspects (e.g. job satisfaction and social support) in their working environment. This would result in positive appraisal that, in turn, would counter or minimize the effects of burnout. Research conducted by Gerzina and Porfeli (2012:313) on patients indicated that mindfulness is a significant predictor of burnout.

The application of mindfulness in the workplace has also been proven to be a persuasive tool for helping employees deal with anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorders (Bodhi 2011:19). Mindfulness reduces workplace tension. Employees who practice mindfulness are able to communicate more clearly and show more appropriate reactions during stressful situations (Gerzina & Porfeli 2012:313). They are also able to handle workplace conflict and are able to think 'out of the box' (Bodhi 2011:19). Mindfulness helps a business to offer a higher standard of customer services because the employees are equipped with skills to respond more appropriately to possible challenges (Alexander 2010:1). According to Williams, Ciarrochi and Deane (2010: 281), employees can be educated about mindfulness and it can therefore be taught.

2.2 Job satisfaction

Werther and Davis (1999:501) define job satisfaction as the amount of favourableness or unfavourableness with which an employee views his/her job. Job satisfaction thus refers to employees' opinion about their job and encompasses their positive or negative feelings towards the working environment. Job satisfaction causes employees to feel more engaged in the workplace (Robbins & Coulter 2005:374). Salanova, Libano, Llorens and Schaufeli (2013:9) reported that engaged employees have more positive experiences in the work place, are more committed towards the organisation and view job demands in a positive manner.

Employees experiencing burnout, however, will not display commitment to their organisation. This could result in either a high turnover or high rates of absenteeism which presents a problem since a successful organisation is dependent on its employees (Wright & Bonett 2007: 142). Although Grobler, Wärnich, Carrell, Elbert and Hatfield (2002:104) have stated that no workplace could overcome an employee's lack of willingness or interest, Kara et al. (2013:16) found that organisations do have the ability to improve job satisfaction and hence decrease absenteeism. Satisfied employees are reported to be committed workers and this is helpful for effectual operations and organisational output (Robbins & Coulter 2005:370).

From the above discussion it is evident that job satisfaction is not only a significant predictor for turnover (Wright & Bonett 2007), but it is also negatively correlated with burnout (Griffin et al. 2010: 248; Kinman et al. 2011: 848; Meeusen, Van Dam, Brown-Mahoney, Van Zundert & Knape 2010:616-621 ; Platsidou & loannis 2008: 61-76). Griffin et al. (2010: 249), who conducted a study amongst correctional staff, noted that happy employees are more satisfied with their jobs and that these feelings of happiness serve as a buffer against burnout.

2.3 Social support

One of the factors that strengthen an employee's overall wellness is social support (Kinman et al. 2011: 845). Social support indicates the amount of support an employee perceives he/she is receiving from family/friends, spouse, supervisor and other employees. Social support can thus be perceived as an employees' belief that he/she is valued, loved and cared for. Consequently, social support is an involving perception towards helping relationships of varying strength and quality which include resources such as emotional empathy, tangible assistance or communication of information (Viswesvaran, Sanchez & Fisher 1999:315).

Social support in the workplace can be defined as the degree to which employees perceive that their wellness is valued by their supervisors and the broader organisation in which they are rooted, together with their perception that these resources will provide help to support their wellness (Ford, Heinen & Langkamer 2007:58). Workplace social support could therefore be conceptualised as emanating from various sources such as supervisors and colleagues. According to McGuire and McLaren (2009), support from a colleague or supervisor will positively affect the employee's wellbeing and will increase his/her commitment - which will increase the employee's performance. Social support is thus a critical resource in the workplace which might result in an employee experiencing demanding roles more positively (Kossek, Pichler, Bodner & Hammer 2011:290).

Kinman et al. (2011:847-853) conducted a study on teachers in the United Kingdom and measured the levels of social support from different sources. Two noteworthy results were obtained. First of all it was determined that social support protected the teachers from developing burnout. Secondly, it was established that social support and job satisfaction were related to some extent in terms of emotional labour (Kinman et al. 2011:847-853). This confirms Young's (2004:302) notion, namely, that social support minimizes stress by acting as a buffer in the stressor-strain relationship experienced in the workplace. When stress is minimized in the workplace, employees tend to experience greater job satisfaction and enhanced feelings of accomplishment which, in turn, prevent the occurrence of burnout (Kinman et al. 2011:847-853).

2.4 The prevalence of burnout

A recent study in the Netherlands has shown that 4% of the total working population is showing serious symptoms of burnout and should seek professional help (Luitjelaar, Verbraak, Van den Bunt, Keijsers & Arns 2010:208). According to Luijtelaar et al. (2010:208), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-IV3) does not provide for the diagnosis of burnout, namely, the long-lasting and medically mysterious fatigue.

The key dimensions, characteristics or primary symptoms of burnout levels are (Abdool Karrim Ismail 2010:12; Bakker, Demerouti & Verbeke 2004:84): (1) exhaustion that is a result of prolonged exposure to specific working conditions (or stressors) and (2) disengagement in terms of which an employee distances him or herself from work and develops negative attitudes towards work. Because of its simplicity, this definition of burnout could be perceived as misleading. According to Griffin, Hogan, Lambert, Tucker-Gail and Baker (2010:239), as well as Wright et al. (2010:375), burnout should rather be perceived as a multidimensional construct describing employees' experiences of physical and psychological exhaustion, depersonalisation, frustration and reduced sense of personal accomplishment. As a result of its complexity, the effects of burnout will be detrimental to the competitive advantage any organisation is striving for (Griffin et al. 2010: 239; Wright et al. 2010: 375).

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1 Research approach

This research study took the form of a correlational research design. Descriptive statistics in the form of means, standard deviations, minimum and maximum scores were computed for the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale and the Overall Job Satisfaction and Social Support Scales (Grobler, Joubert, Rudolph & Hajee-Osman 2012:330). Cronbach's alphas were computed for each of these scales to determine how reliable they were in the context of the present study.

Correlational analyses were conducted to "...to establish that a relationship exists between variables and to describe the nature of the relationship" (Gravetter & Forazano 2012: 308). Thereafter, a multiple regression analysis was deemed appropriate to determine which of the independent variables (mindfulness, job satisfaction and social support) contributed significantly to explaining the variance in burnout scores (Pallant 2006:95).

3.2 Research participants

A systematic random sampling technique was used to ensure a high degree of representativeness from the target population (Gravetter & Forzano 2012:146). The organisation involved in the study is part of the banking industry. Owing to the global crisis in international banking, poor corporate governance, white-collar crime and the worldwide retrenchments of bank employees, considerable pressure is experienced within the banking environment (Willey, Mansfield & Sherman 2012:266). Furthermore, because of easy accessibility, a bank in Johannesburg (South Africa) was identified as the organisation to obtain a sampling frame from.

Within the ethical guidelines of research permission to conduct the study was obtained by approaching the relevant structures and individuals through the human resource (HR) department of the bank. Systematic random sampling was used to establish the research sample. Systematic sampling is a form of probability sampling where the researcher obtains a sample by selecting every nth participant from the target population. The human resources department provided a list containing the contact details of all its employees. The first participant was randomly selected and from there on every 14th name on the employee list was chosen for inclusion in the sample. The total number of employees within the population equalled 3577 (N = 3577). A sample size of 400 was considered to be adequate. However, only 209 of the selected participants agreed to participate in the study. Although this number was not the envisaged total, the sample size was sufficient to conduct complex statistical analyses such as multiple regression analysis (Abdool Karrim Ismail 2010:65). Each participant that agreed to participate in the study signed a consent form to confirm their voluntary participation and that they took note of their rights and privacy regarding the research. They also confirmed that the results may be used for research purposes.

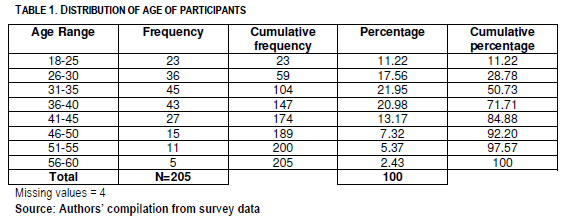

A biographical questionnaire was used to generate data related to the general information of the participants. Table 1 displays the age distribution of the participants.

Table 1 indicates that most of the participants were between the ages of 18 and 60. The largest number of participants was between the ages of 26 to 40 years. The smallest number of participants was between the ages of 56 to 60 years.

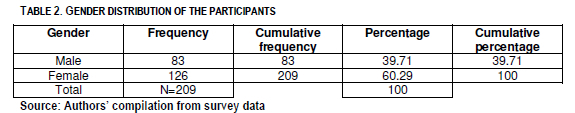

Table 2 displays the gender distribution of the participants.

From Table 2 it is clear that most of the participants were female.

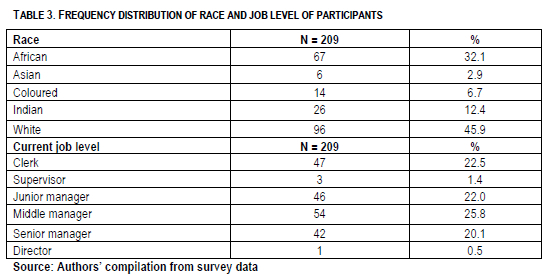

Table 3 presents the frequency distribution of the race of the participants and also shows at which job level were they situated at during the course of the study.

It is apparent from Table 3 that most of the participants were from the African and white race groups. Only six participants were from the Asian race group. The participants were equally distributed among different job levels, except on the supervisor and director levels.

3.3 Measuring instruments and research procedures

Participants were required to complete the (1) Overall Job Satisfaction scale, (2) Social Support scale, (3) Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), and (4) the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI).

The Overall Job Satisfaction scale was originally developed by Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins and Klesh (as cited by Abdool Karrim Ismail 2013:73) and form part of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (OAQ). The scale consists of three items to describe the subjective experience of worker satisfaction with a job. Responses are indicated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1= strongly agree, 2 = disagree, 3 = slightly disagree, 4 = neither agree nor disagree, 5= slightly agree, 6= agree and 7 strongly agree).

The Social Support scale was developed by Caplan, Cobb, French, Van Harrison and Pinneau (as cited by Abdool Karrim Ismail 2010:74) and consists of four items. The Social Support scale determines the support an employee perceives is available from family/friends, spouse, supervisor and other employees. Responses are indicated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (4=very much, 3 = somewhat, 2 = a little, 1 = not at all and 0 = don't have any such person).

The MAAS was developed by Broan and Ryan (as cited by Abdool Karrim Ismail 2010:79) and consists of 15-items. It is a single-factor self-report measure that assesses individual differences in the frequency of mindful states. A 6-point Likert scale is used in the MAAS (1 = almost always to 6 = almost never).

The OLBI was developed by Demerouti, Bakker, Vardakou and Kantas (as cited by Abdool Karrim Ismail 2010:79-80) and measures burnout independent of type of occupation. The OLBI consists of 16 items (8 items measure disengagement and the other 8 items measure exhaustion). A 4-point Likert scale is used in the OLBI and ranges from 1 = totally disagree to 4 = totally agree.

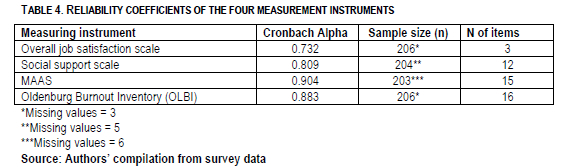

Before the commencement of the data analysis, the reliability coefficients in the form of Cronbach's alphas were calculated for each of the four scales. The results are presented in Table 4.

All the measuring instruments' reliability coefficients were high. It was concluded that each of the four instruments measured high on internal consistency and further data analyses were deemed possible.

3.4 Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis in the form of measures of central tendency and dispersion were used to obtain descriptive statistics for the four measurement instruments. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to test for relationships between burnout, mindfulness, job satisfaction and social support. It was also used to determine the strength and direction of correlations once it was established that relationships exist between the variables. A multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine which of these variables (mindfulness, job satisfaction and social support) contributed significantly to explaining the variance in burnout scores.

4 RESULTS

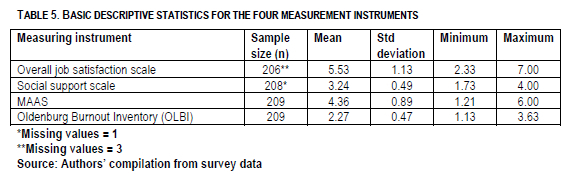

The results of the basic descriptive statistics are presented in Table 5.

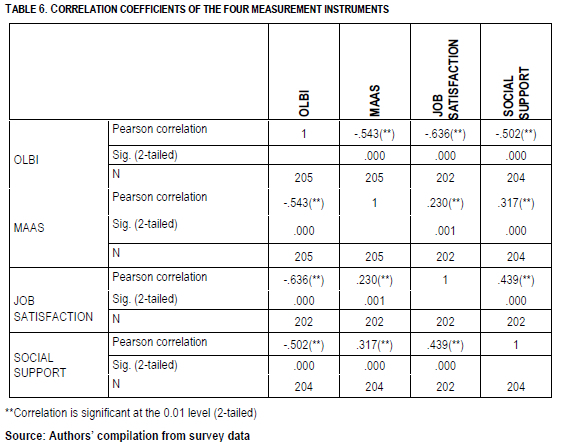

The results of the Pearson correlations are presented in Table 6.

Several correlations are evident in Table 6. The first correlation indicates a significantly moderate inverse correlation [r = -0.543, p<0.01] between burnout and mindfulness. Another moderate inverse correlation [r = -0.502, p<0.01] was obtained between burnout and social support. Job satisfaction, on the other hand, displayed a significantly large inverse relationship [r = -0.636, p<0.01] with burnout. Overall job satisfaction displayed a moderate correlation with social support. Finally, mindfulness obtained weak, positive correlations with both social support [r = 0.317, p<0.01] and job satisfaction [r = 0.230, p<0.01].

Preliminary analysis was conducted on the data to ensure that the assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity and homoscedasticity had not been violated. Since mindfulness, social support and job satisfaction correlated with burnout, a backward multiple regression analysis was used to establish the relative strength of these significant contributor(s) to burnout.

The three variables together explained 59.3% of the variance in burnout [F(3, 198) = 96.31, p < 0.001]. Job satisfaction was the most significant contributor to burnout in this study, recording the highest beta value [beta = -0.472, p < 0.001]. Mindfulness obtained the second highest beta value [beta = -0.379, p < 0.001] while social support scored the lowest beta value [beta = -0.175, p < 0.001].

5 DISCUSSION

The results illustrated in Table 6 indicate a significantly large inverse relationship between job satisfaction and burnout. This result confirms the observed inverse correlation between burnout and job satisfaction noted in several studies (Griffin et al. 2010:248, Kinman et al. 2011:848, Meeusen et al. 2010:616-621, Platsidou & Ioannis 2008:61-76). Job satisfaction also obtained the highest beta value when the multiple regression analysis was conducted. Job satisfaction can thus be deemed the best predictor of burnout in the current study. The finding concurs with that of Griffin et al. (2010:249) who determined that happy employees are satisfied with their jobs and that these feelings could act as a buffer against burnout. It also supports Robbins and Coulter's (2005:370) observation that satisfied employees are committed workers who would be less prone to suffer from burnout.

A moderate significant inverse correlation was obtained between burnout and mindfulness. Mindfulness furthermore was identified by the backward multiple regression analysis as the second highest predictor of burnout. These results clearly demonstrate that mindful employees are likely to be less prone to experience burnout. The current findings concur with Gerzina and Porfeli's (2012:313) findings that showed mindfulness is a significant predictor of burnout. It also confirm Bodhi's (2011:19) notion that the application of mindfulness in the workplace can significantly decrease burnout.

The results further indicated that mindfulness and job satisfaction had a significant positive correlation. Consequently, it is assumed that mindfulness could positively impact on an employee's job satisfaction. Therefore, it is presupposed that mindfulness might achieve positive thinking which in turn could result in employees being more willing to do their jobs and attaining higher levels of job satisfaction. Mindfulness also correlated significantly with social support, indicating that employees who receive social support from employers, friends and loved ones would experience more positive thinking. In the end this would result in an employer feeling valued, loved and cared for in the organisation.

Such feelings in turn would counter the occurrence of burnout. Evidence of this can be found in the observed inverse correlation between social support and burnout and the fact that social support, albeit not to the same extent as mindfulness and job support, contributed significantly towards the prevention of burnout. The present study's findings confirm the results obtained by Kinman et al. (2011:847-853) which showed that the existence of social support would protect employees from experiencing burnout. Kossek et al. (1999:315) furthermore argued that social support is a critical element in the workplace.

According to these authors the presence of social support enables employees to do their best because they realise others are there to support them should they experience any hindrances or negative emotions. Social support thus increases the favourableness of an employee's opinion regarding his/her job. The positive correlation found between social support and job satisfaction supports this argument. Further support of the argument may be found in Kinman et al.'s (2011:847-853) study that showed social support and job satisfaction were related to some extent with one another. This study was limited to one financial organisation. Therefore the data cannot be generalised. It is therefore recommended that the same study is conducted in other organisations.

6 CONCLUSION

The main aim of this research was to investigate the relationship between burnout, job satisfaction, social support and mindfulness in a South African corporate organisation. It was found in this study that burnout is negatively correlated with job satisfaction, mindfulness and social support. Positive relationships were also observed between job satisfaction, social support and mindfulness. The backwise multiple regression analysis identified job satisfaction, mindfulness and social support as significant elements in the prevention of burnout. In sum, these results suggested that organisations have to consider both interpersonal as well as intrapersonal strategies to prevent the occurrence of burnout. Although burnout might be prevalent in organisations, the amount of social support, willingness of an employee to do his/her job (job satisfaction) and ability to practice mindfulness may result in a more engaged and committed employee in the workplace that will be protected from burnout.

This study was conducted in the banking industry and can therefore not be generalised to other populations. It is suggested that employees should be positively engaged by means of a productive intervention process. Mindfulness can be a source of employer value proposition and may in the long run provide organisations with a valuable tool to manage high burnout levels of employees within the workplace. Consequently, the practical implications lie in the field of human resource development where interventions could be developed to include practices that enable employees to develop positive mindful thinking, interpersonal relations (social support), a willingness to be engaged in the workplace and a lower intention to resign from an organisation.

REFERENCES

ABDOOL KARRIM ISMAIL H. 2010. The relationship between mindfulness and burnout amongst employees in a South African corporate organisation. Mini dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree: University of Johannesburg. Johannesburg. MA (Clinical Psychology). [ Links ]

ALEXANDER R. 2010. Learn how to become a mindful leader. [Internet: www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-wise-open-mind/201001/learn-how-become-mindful-leader; downloaded on 2013/06/18]. [ Links ]

BAKKER AB, DEMEROUTI E & VERBEKE W. 2004. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management 43(1):83-104. [ Links ]

BOND FW & BRUCE D. 2000. Mediators of change in emotion-focused and problem-focused worksite stress management interventions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5:156-163. [ Links ]

BROWN KW & RYAN RM. 2003. Perils and promise in defining and measuring mindfulness: Observations from experience. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 11(3):242-248. [ Links ]

BODHI B. 2011. What does mindfulness really mean? A canonical perspective. Contemporary Buddhism 12(1):19-39. [ Links ]

DEMEROUTI E, BAKKER AB, NACHREINER F & SCHAUFELI WB. 2001. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 86(1):499-512. [ Links ]

FORD MT, HEINEN BA & LANGKAMER KL. 2007. Work and family satisfaction and conflict: a meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology 92(1): 57-80. [ Links ]

GERZINA HA & PORFELI EJ. 2012. Mindfulness as a predictor of positive reaapraisal and burnout in standardized patients. Teacgubg and Learning in Medicine: An International Journal 24(4):309-314. [ Links ]

GRAVETTER FJ & FORZANO LB. 2012. Research methods for the behavioural sciences. 4th edition. London: Sage. [ Links ]

GRIFFIN ML, HOGAN NL, LAMBERT EG, TUCKER-GAIL KA & BAKER DN. 2010. Job involvement, job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment and the burnout of correctional staff. Criminal Justice and Behavior 37(2): 239-255. [ Links ]

GROBLER A, & JOUBERT YT, RUDOLPH EC & HAJEE-OSMAN M. 2012. Utilisation of the expectation disconfirmation model: EAS rendered in the SAPS. Journal of Contemporary Management 9(12): 324-340. [ Links ]

GROBLER PA, WÄRNICH S, CARRELL MR, ELBERT MF & HATFIELD RD. 2002. Human resource management in South Africa. 2nd edition. London: Thompson. [ Links ]

KABAT-ZINN J. 2008. Full catastrophe living: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. 15th edition. London: Piatkus. [ Links ]

KARA D, UYSAL M, SIRGY MJ & LEE G. 2013. The effects of leadership style on employee well-being in hospitality. International Journal of Hospitality Management 34:9-18. [ Links ]

KINMAN G, WRAY S & STRANGE C. 2011. Emotional labour, burnout and job satisfaction in UK teachers: the role of workplace social support. An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology 31:843-856. [ Links ]

KOSSEK EE, PICHLER S, BODNER T & HAMMER LB. 2011. Workplace social support and work - family conflict: a meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work-family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Personnel Psychology 64(2): 289-313. [ Links ]

LAWSON K. 2011. Demystifying mindfulness. [Internet: www.minnesotanedicicine.com; downloaded on 2012/08/03]. [ Links ]

LINDFORS P. 2012. Reducing stress and enhancing well-being at work: are we looking at the right indicators? European Journal of Anaesthesiology 29:309-310. [ Links ]

MASLACH C. 1982. Burnout: A social psychological analysis. In JW Jones (ed.) The burnout syndrome: current research, theory, investigations: 30-35. Park Ridge, IL: London House Press. [ Links ]

MCGUIRE D & MCLAREN L. 2009. The impact of physical environment on employee commitment in call centres: the mediating role of employee well-being. Team Performance Management 15(1/2): 35-48. [ Links ]

MEEUSEN V, VAN DAM K, BROWN-MAHONEY C, VAN ZUNDERT A & KNAPE H. 2010. Burnout, psychosomatic symptoms and job satisfaction among Dutch nurse anaesthetists: a survey. Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 54(5), 616-621. [ Links ]

PALANT J. 2006. SPSS survival manual: a step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS version 12. New York: Open University Press. [ Links ]

PLATSIDOU M & IOANNIS A. 2008. Burnout, job satisfaction and instructional assingment-related sources of stress in Greek special education teachers. International Journal of Disability, Development & Education 55(1):61-76. [ Links ]

PRUESSNER JC, HELLHAMMER DH & KIRSCHBAUM C. 1999. Burnout, perceived stress, and cortisol responses to awakening. Psychosomatic Medicine 61:197-204. [ Links ]

ROBBINS SP & COULTER M. 2005. Management. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education/Dorling Kindersley. [ Links ]

SALANOVA M, DEL LIBANNO, M, LLORENS, S & SCHAUFELI WB. 2013. Engaged, workahoic, burned-out or just 9-to-5? Toward a typology of employee well-being. Stress Health: 1-11. [ Links ]

SPICKARD A, GABBE S & CHRISTENSEN JF. 2002. Mid-career burnout in generalist and specialist physicians. American Medical Association 288(2):1447-1450. [ Links ]

YOUNG AM. 2004. Stress and well being in the context of mentoring processes: new perspectives and directions for future research. Research in Occupational Stress and Well-being 4:295-325. [ Links ]

VAN LUITJELAAR G, VERBRAAK M, VAN DEN BUNT M, KEIJSERS G & ARNS M. 2010. EEG findings in burnout patients. The Journal Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 22(2):208-217. [ Links ]

VALLEN GK. 1993. Organizational climate and burnout. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 34(1):54-59. [ Links ]

VISWESVARAN C, SANCHEZ JI & FISHER J. 1999. The role of social support in the process of work stress: a meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior 54: 314-334. [ Links ]

WERTHER WB & DAVIS K. 1999. Human resources & personnel management. 5th edition. London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

WILLEY SL, MANSFIELD NR & SHERMAN B. 2012. Integrating ethics across the curriculum: a pilot study to assess students' ethical reasoning, Journal of Legal Studies Education 49(2):263-296. [ Links ]

WILLIAMS V, CIARROCHI J & DEANE FP. 2010. On being mindful, emotionally aware, and more resilient: Longitudinal pilot study of police recruits. Australian Psychologist 45(4):274-282. [ Links ]

WRIGHT TA & BONETT DG. 2007. Job satisfaction and psychological well-being as non-additive predictors of workplace turnover. Journal of Management 33:141-160. [ Links ]

WRIGHT KB, BANAS JA, BESSARABOVA E & BERNARD DR. 2010. A communication competence approach to examining health care social support, stress and job burnout. Health Communication 25(4):375-282. [ Links ]