Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.10 no.1 Meyerton 2013

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The influence of relationship intention on relationship length and contractual agreements

L Kruger; PG Mostert

North-West University

ABSTRACT

Within the competitive cell phone industry, long-term customer relationships can result in much needed customer retention. However, relationship marketing strategies should only be applied to customers receptive to relationship building; relationship marketing strategies should be targeted at customers with relationship intentions. This article examined relationship intention within the South African cell phone industry through a non-probability convenience sample of 605 respondents. Findings suggest that cell phone users' overall or level of relationship intentions is not associated with their relationship lengths or contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers. Consequently, cell phone network providers should be cautious to use customers' relationship lengths or contractual agreements in isolation to identify customers for relationship building. It is recommended that cell phone network providers should target customers with relationship intentions for relationship building, as these customers are the most likely customers to be retained and provide return on such an investment.

Key phrases: cell phone network providers; contractual agreement; length of relationship; relationship intention

1. INTRODUCTION

The South African information and communication technology (ITC) industry is expected to grow to an estimated R250 billion by 2020 (Van Niekerk 2012:98) partly because the country's cell phone industry is believed to be amongst the fastest growing cell phone industries of the world (Mbendi 2011 :Internet). Furthermore, the South African population is regarded as one of the highest users of cell phones on the African continent (Berger, Sinha & Pawelczyk 2012:Internet) which illustrates the cell phone industry's lucrative positioning.

The Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA), the South African communication regulator, considers promoting competition amongst cell phone network providers as a strategic objective for the fiscal years 2013-2017. The aim of promoting competition is to stimulate innovation and allow greater access to cell phone communication, which will improve the South African economy (ICASA 2012:3, 30, 32, 39). Customer retention strategies in the South African cell phone industry are thus particularly important as competition between cell phone network providers is evident (Homburg & Giering 2001:43), alternative cell phone network providers are available (Morrisson & Huppertz 2010:250), and customers perceive high degrees of similarity between different cell phone network providers, despite cell phone network providers' best efforts to differentiate themselves (Haenlein & Kaplan 2012:467).

The fact that the market to attain new cell phone customers is very small (only about 20% of the South African population 15 years and older do not own or have access to a cell phone) (Habari Media 2012:Internet; Van Niekerk 2012:101), further necessitates customer retention within the South African cell phone industry and possibilities of upward migration and cross-selling. To this end, relationship marketing can be utilised to form relationships with customers in order to retain them in this competitive industry (Coulter & Ligas 2004:489; Sheth & Parvatiyar 2002:4). While it is argued that customers do not necessarily want relationships with large service providers like cell phone network providers as there is no individual person with whom customers can form relationships (Beetles & Harris 2010:354), Kumar, Bohling and Ladda (2003:669-670) assert that certain customers want to engage in relationships with service providers, brands or channel members, because they have relationship intentions. Kumar et al. (2003:670) accordingly proposed five constructs to measure relationship intention, namely, involvement, expectations, fear of relationship loss, feedback and forgiveness.

Customers' relationship lengths (Seo, Ranganathan & Babad 2008:192) and contractual agreements (Nel & Boshoff 2012:Conference proceedings) are often used by cell phone network providers to segment customers as either relationship or transactional customers for relationship marketing purposes. It is argued that customers' relationship intentions should rather be used and therefore the purpose of this article is to determine cell phone users' relationship intentions and to determine whether such intentions influence the relationship length or contractual agreements with cell phone network providers. This article starts with a literature review followed by the problem statement directing the research and objectives formulated for the study. The methodology, results, conclusions together with limitations and recommendations for future research are subsequently presented.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Relationship marketing

Berry (1995:237) posits that maintaining existing customer relationships costs less than continuously attracting new customers. This cost-saving property of maintaining existing customers is the main motivation for relationship marketing which focuses on retaining existing customers (Sheth & Parvatiyar 2002:4). However, for a relationship between a customer and service provider to exist, both parties must perceive and anticipate clear benefits from the relationship and both parties must be able to choose whether to remain in the relationship (Gwinner, Gremler & Bitner 1998:101, 112).

Relationship marketing is applicable within the boundaries of services marketing (Beetles & Harris 2010:348, 354), provided that there is a frequent need for the service, the customer controls the selection of the service provider, and alternative service providers are available to choose from (Berry 2002:62, 69). Due to the direct contact between customers and service providers, satisfactory service might result in establishing enduring relationships between the two parties (Grönroos 2004:100).

Although customers have the propensity to act as active partners of, and form relationships with service providers (Long-Tolbert & Gammoh 2012:397; Mason & Simmons 2012:227), customers also have relational preferences influencing their decision to build relationships (Hess, Story & Danes 2011:22). Customers' relationship intentions (willingness to build relationships with service providers) (Kumar et al. 2003:669) should be considered before relationship marketing strategies are deployed (Dalziel, Harris & Laing 2011:399, 420) as it is wasteful to utilise organisational resources to build relationships with customers not desiring relationships (Tuominen 2007:182).

2.2 Relationship intention

Kumar et al. (2003:669) advocate that emotionally attached customers who trust and have a high affinity towards a particular service provider, have relationship intentions towards the particular service provider. Customers' emotional attachments foster long-term relationships with service providers (Kumar et al. 2003:667; Long-Tolbert & Gammoh 2012:391), which, in turn, result in increased customer loyalty and retention (Coulter & Ligas 2004:490). Kumar et al. (2003:670) proposed five constructs to measure customers' relationship intentions, namely, involvement, expectations, fear of relationship loss, feedback and forgiveness.

2.2.1 Involvement

According to Kumar et al. (2003:670), involvement can, for relationship intention purposes, be defined as customers' willingness to engage in relationship activities. Although there is a relationship appeal for customers in high-involvement services (Berry 1995:237), most services require customer involvement in the consumption process (Grönroos 1984:37). However, customers' interests, goals, attachment, motivation towards an object (Ruiz, Castro & Armario 2007:1094), and personal relevance of the object to customers (Petty, Cacioppo & Schumann 1983:143), all influence their involvement with a service provider. For this reason, some customers might be highly involved with a service, while others are hardly involved with the same service (Bloemer & De Ruyter 1999:325). Customers' involvement with service providers influences their motivation, intention and behaviour (Taylor 2007:747), which is evident when involved customers may feel uncomfortable and guilty when using similar services from another service provider (Kumar et al. 2003:670).

Involvement facilitates relationship building (Kinard & Capella 2006:365) and customer loyalty (Dagger & David 2012:461; Mascarenhas, Kesavan & Bernacchi 2004:486). Furthermore, involved customers have contact with (Scott & Vitartas 2008:54) and provide positive feedback to their service providers (Mascarenhas et al. 2004:486). The aforementioned information enables service providers to know and exceed their customers' expectations (Engeseth 2006:36-37). Moreover, highly involved customers hold more realistic expectations of their service providers (Steyn, Mostert & De Jager 2008:144).

2.2.2 Expectations

Customers' expectations are the standards of service which act as the frame of reference from which to compare perceived experiences, and are used for satisfaction judgements (Oliver 1980:460; Zeithaml, Berry & Parasuraman 1993:1) and, ultimately, behavioural intentions (Choy, Lam & Lee 2012:14). Desired service, adequate service and predicted service are three different levels of service for which expectations are formed (Zeithaml et al. 1993:10). Desired service implies that customers hold expectations concerning the level of service they want to receive from service providers, adequate service refers to expectations concerning the level of service customers are willing to accept, albeit not the desired service, and predicted service concerns expectations about the level of service customers believe is likely to occur (Zeithaml et al. 1993:6, 10).

The nature and standard of service provision, together with customer characteristics, attitudes, and preferences, form customer expectations (Mason & Simmons 2012:233). Extended service transactions (like the use of a cell phone network provider in this study) entail that customers' expectations change from the pre-purchase state to the post-purchase state with every interaction with service providers, all of which influence customers' future expectations (Dubé & Menon 2000:294). In established relationships with service providers, customers hold higher quality expectations (Price & Arnould 1999:51) due to the investment of irrecoverable resources, such as time, in the relationship (Liang & Wang 2006:120-121). Customers with higher expectations are, therefore, more likely to develop relationships with their service providers as they are concerned with and care about their service providers, all of which may contribute to fear of relationship loss (Kumar et al. 2003:670).

2.2.3 Fear of relationship loss

The benefits customers perceive from close relationships with service providers include security, a feeling of control and a sense of trust, minimised purchasing risks, and reduced costs during purchase decisions, as customers are familiar with the service provider (Grönroos 2004:99). According to Kumar et al. (2003:670), relationship intention is evident when customers fear losing the relationship with the service provider because of the risk shared with the service provider. Gwinner et al. (1998:102), Jones, Reynolds, Motherbaugh and Beatty (2007:337), and Kumar et al. (2003:670) therefore propose that switching costs, relational benefits and bonds contribute to customers' fear of relationship loss.

Firstly, switching costs are the sacrifices or penalties customers may experience in moving from one service provider to another (Jones et al. 2007:337). Switching costs may include the loss of any loyalty benefits as a result of ending the relationship (Lam, Shankar, Erramilli & Murthy 2004:295), as well as the time and effort associated with finding a new service provider and adapting to new services (Vázquez-Casielles, Suárez-Álvarez & Belén Del Río-Lanza 2009:2293). The more types of products customers buy from the same service provider, the higher the switching costs of using another service provider will be (Burnham, Frels & Mahajan 2003:119).

Secondly, benefits above and beyond the core service customers receive from long-term relationships with service providers are considered as relational benefits (Gwinner et al. 1998:102). Spake and Megehee (2010:316) add that customers will only continue relationships with service providers if the benefits of the relationships exceed the costs, thereby possibly reducing the risk customers perceive when dealing with service providers (Berry 1995:238). Gwinner et al. (1998:109-110) contend that relational benefits can be considered in terms of three categories, namely, confidence benefits (faith in the trustworthiness of the service provider, reduced perceptions of anxiety and risk, and knowing what to expect from the service provider), social benefits (customers being recognised by employees, customer familiarity with employees, and the development of friendships between customers and employees), and special treatment benefits (customers may receive a reduced price or special service).

Lastly, repetitive satisfactory interaction over time with a specific service provider causes customers to form a bond with the service provider, resulting in the likelihood of developing lasting commitment towards the service provider (Homburg, Giering & Menon 2003:44; Spake & Megehee 2010:316, 319-320). These bonds can be psychological, emotional, economic or physical (Liang & Wang 2006:123) and determine the strength of the particular relationship (Moore, Ratneshwar & Moore 2012:260). Kumar et al. (2003:670) propound that fear of losing bonds characterises customers with high relationship intentions. Service providers can use bonds with customers and their knowledge of customers (Berry 1995:238), based on feedback received from customers (Wirtz, Tambyah & Mattila 2010:380), to customise services according to customers' needs (Berry 1995:238).

2.2.4 Feedback

Customers' feedback is important as relationship marketing necessitates knowledge exchange (in the form of dialogue between customers and service providers) in order to create value (Grönroos 2004:103), and because the characteristics of services entail that customers' perceptions of service quality are necessary to identify strengths and/or weaknesses (Tontini & Silveira 2007:483). Feedback facilitates both the aforementioned processes.

Customers can provide either positive or negative feedback to service providers, with both types of feedback being useful for service providers. Positive feedback, for instance in the form of compliments, is used for identifying strengths to further reinforce service provision, while negative feedback (complaints), is necessary to improve service provision (Wirtz et al. 2010:380). Involved customers concerned with their service provider (Kumar et al. 2003:670) will provide feedback for both service improvement (Wirtz et al. 2010:380) and altruistic purposes (McCullough, Worthington & Rachal 1997:322). Altruism motivates customers to provide feedback when transgressions occur, in order to prevent other customers from experiencing the same dissatisfactory services (Chelminski & Coulter 2011:362).

2.2.5 Forgiveness

Tsarenko and Tojib (2011:387) and Zourrig, Chebat and Toffoli (2009:406) view forgiveness as a cognitive, affective and motivational response to a transgression such as a service failure. Forgiveness can be conceptualised as a coping strategy when transgressions occur (Tsarenko & Tojib 2011:381, 387).

Forgiveness influences the relationship between parties (Tsarenko & Tojib 2011:381, 387) because forgiveness facilitates behaviour in restoring the relationship with an offending relationship partner, as opposed to terminating the relationship (Chung & Beverland 2006:98). Customers ascribing more value to the relationship than to unfulfilled expectations by forgiving transgressions, reveal relationship intention (Kumar et al. 2003:670).

2.3 Relationship length and contractual agreements within the cell phone industry

Cell phone network providers often consider customers' relationship lengths (Seo et al. 2008:192) and contractual agreements (Nel & Boshoff 2012:Conference proceedings) to distinguish between relationship and transactional customers.

2.3.1 Relationship length

A number of relationship marketing scholars argue that the perceived trust in, involvement with, and attachment to the service provider, increase as the length of customers' relationships with their service providers increase (Grayson & Ambler 1999:139; Seo et al. 2008:192; Verhoef, Franses & Hoekstra 2002:211). However, contradictory to this view, it is counter-argued that the length of relationships customers have with their service providers does not influence the type of relationships or emotional attachments customers choose to have with their service providers (Coulter & Ligas 2004:484; Homburg et al. 2003:52; Kumar et al. 2003:669-670, 673). There is thus inconclusive evidence in literature regarding what the influence of relationship length is on customers' relationships with service providers. For this reason, it is also important to investigate the extent to which customers' relationship intentions influence their relationship length with cell phone network providers.

2.3.2 Contractual agreement

Customers pursue relationships either because they choose to, or because they are forced to, for example, through a contract (Kumar et al. 2003:670). Although the prepaid option (not necessitating a credit check) of cell phone services in South Africa accelerated the adoption of cell phone services (Gillwald 2005:477), cell phone network providers in South Africa also offer customers contracts for a certain length of time (usually 24 months) with penalties for ending the contract early (O'Sullivan, Edmond & Ter Hofstede 2002:127; Seo et al. 2008:184). However, research suggests that customers locked into relationships with their cell phone network providers through contracts consider the value-offering of their cell phone network providers as more important than the brand or the relationship with their cell phone network providers (Nel & Boshoff 2012:Conference proceedings). Considering that customers with contracts are more concerned with the value they receive than relationships with their cell phone network providers, it is also important to examine whether customers' relationship intentions affect their choice to enter into a contract with a cell phone network provider.

3. PROBLEM STATEMENT AND RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

Within the South African cell phone industry, where more than 80% of the potential market already owns or has access to a cell phone (Habari Media 2012:Internet; Van Niekerk 2012:101), and competition will increase (ICASA 2012:3, 30, 32, 39), cell phone network providers should consider better relationships with customers as a strategy to retain their customers (Coulter & Ligas 2004:489; Sheth & Parvatiyar 2002:4), and, consequently, create a sustained competitive advantage. Relationships with customers result in increased sales, market share and profits (Jena, Guin & Dash 2011:23). However, all customers will not desire relationships with their service providers. (Dalziel et al. 2011:399, 420). It is therefore essential to target those customers with relationship intentions for relationship building (Kumar et al. 2003:669) instead of only considering customers' relationship lengths (Seo et al. 2008:192) and contractual agreements (Nel & Boshoff 2012:Internet) to categorise customers as either relationship or transactional customers for relationship marketing purposes.

Previous research on relationship intention in the South African context, focussed on scale development (Kruger & Mostert 2012:45) and documenting variation in relationship intention responses across different industries (Mostert 2012:32). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate cell phone users' relationship intentions and to determine whether their relationship intentions influence relationship length or contractual agreements with cell phone network providers. The following objectives have been formulated:

• Determine the reliability and validity of the relationship intentions measure to establish cell phone users' relationship intentions;

• Determine the influence of cell phone users' relationship intentions on the length with their cell phone network providers; and

• Determine the influence of cell phone users' relationship intentions on the contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers.

4. METHODOLOGY

4.1 Sample and measuring instrument

The study population encompassed individuals 18 years or older, residing in Gauteng, who have used the services of any cell phone network provider for at least three years. The last criterion was added as experienced and inexperienced customers could have different expectations of service provision because they have different levels of familiarity with the service (Zeithaml et al. 1993:3). Non-probability convenience sampling aided the descriptive research design in this study. Personal in-home interviews were conducted by trained fieldworkers using interviewer-administered questionnaires.

Closed-ended questions were used throughout the questionnaire and where scale items were used, a 5-point unlabelled Likert scale was used with two extremes, where 1 = no, definitely not, and 5 = yes, definitely. The questionnaire started with a preamble explaining respondents' rights and the purpose of the study, followed by screening questions. Furthermore, the questionnaire included three sections for the purpose of this article. The first section captured classification and patronage information concerning respondents' cell phone network providers. The second section measured relationship intention by means of the scale as proposed by Kruger and Mostert (2012:45). This scale is considered to be reliable and valid to measure relationship intention towards service providers within the South African context (Mostert 2012:Inaugural address). The last section was devoted to obtaining respondents' demographic details. A pilot study of the questionnaire to test the relevancy of the questionnaire and identify any vital problems in the questionnaire design (Zikmund & Babin 2010:61-62), was done with 27 respondents resembling the study population.

4.2 Data analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 21) and the SAS statistical program (Version 9.3) were used for statistical processing. SPSS was used to capture and clean data by rectifying key-punching errors and discarding poor quality or incomplete questionnaires. A total of 605 usable questionnaires were obtained. The following analyses were done:

• Frequencies for all demographic and patronage habit variables were calculated.

• Descriptive statistics were calculated for all the constructs under study.

• The study used a confidence level of 95% and a subsequent significance level of 0.05.

• Overall mean scores were calculated for each construct. Chi-square tests for independence were performed to determine whether there were significant associations between the constructs of the study. Furthermore, t-tests were performed to determine whether a statistically significant difference exists between the means of two groups and one-way Anovas were performed to determine whether statistically significant differences exist between the means of more than two groups.

• As statistical significance does not indicate the strength of the significance, effect sizes were also determined. When examining the effect sizes of the Chi-square test of independence, Cramer's V was used to determine the effect size. For the 3x4 table (relationship intention levels x relationship length), Cramer's V is considered to be small at 0.07, medium at 0.21 and large at 0.35 (Pallant 2010:220). For the 3x2 table (relationship intention levels x contractual agreement), Cramer's V is considered to be small at 0.01, medium at 0.30 and large at 0.50 (Pallant 2010:220). When examining the effect sizes of the Anovas and t-tests, d-values of Cohen to determine practical significance by means of effect size were used. The d-values are considered to be small at 0.2, medium at 0.5 and strong and practically significant at 0.8 or larger (Cohen 1988:25-26). According to Cohen (1988:20), medium effect sizes have ample practical effect, as differences between respondent groups can already be noticed with the naked eye. For this reason, medium and large effect sizes were regarded as practically significant when interpreting results. All d-values were rounded off to 1 decimal.

5. RESULTS

5.1 Respondent profile and cell phone patronage habits

Just more than half of the 605 respondents who participated in this study were female (53.7%). The majority of respondents were Black Africans (33.5%) or Whites (28.3%), and fewer Asians/Indians (21.2%) and Coloureds (17.0%) participated in this study. Furthermore, 43% of the respondents used Vodacom as their cell phone network provider and just over half of the respondents had a contract with their cell phone network provider (52.2%). The majority of respondents had used their cell phone network provider for more than 5 years but less than 10 years (35.2%) or more than 3 years but less than 5 years (29.2%), and had spent between R101 and R250 per month on cell phone expenses (36.2%).

5.2 Reliability

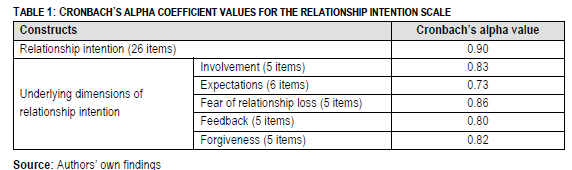

The internal consistency reliability of the relationship intention scale was assessed through Cronbach's alpha coefficient values, where coefficient values of 0.7 and higher are considered reliable (Pallant 2010:6). Table 1 presents the Cronbach's alpha coefficient values for the total relationship intention scale, as well as the five underlying dimensions of relationship intention (further discussed in section 5.3).

It can be observed from Table 1 that the measure of relationship intention is reliable to measure the relationship intentions of adults residing in Gauteng towards their cell phone network providers.

5.3 Construct validity

To determine the underlying dimensions of constructs and to demonstrate construct validity, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed (Bagozzi 1994:342-344). Concerning the relationship intention scale, the measure of sampling adequacy (from here on referred to as MSA) was 0.90 and the eigenvalue indicated that five factors, explaining 58% of the variance, as proposed by Kumar et al. (2003:670), should be retained. Communalities varied between 0.34 and 0.73. The five factors were labelled as involvement, expectations, fear of relationship loss, feedback and forgiveness as proposed by Kumar et al. (2003:670). From this analysis it can be concluded that the measure of relationship intention is valid to measure the relationship intentions of adults residing in Gauteng towards their cell phone network providers.

5.4 Levels of relationship intention

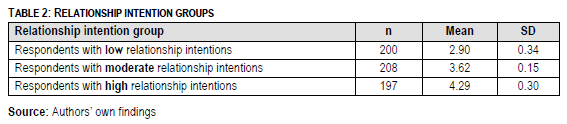

Respondents were categorised into three almost equally sized groups, using the 33.3 and 66.6 percentiles as cut-off points on their overall mean score for relationship intention. Thus, the cut-off points of means for categorising the relationship intention groups were 3.34615 and 3.88462. Table 2 presents the frequencies and standard deviations (SD) for the three relationship intention groups determined from the aforementioned categorisation. Due to the fact that ties occurred in the continuous data, the number of respondents per group differed.

From Table 2 it can be deduced that 200 respondents were categorised as having low relationship intentions (mean=2.90), 208 respondents as having moderate relationship intentions (mean=3.62), and 197 respondents as having high relationship intentions (mean=4.29).

5.5 Relationship intention and relationship length

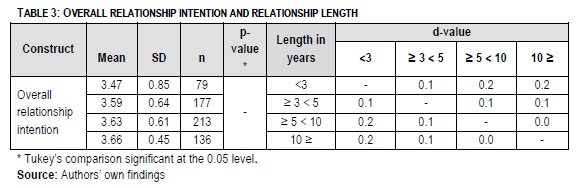

To determine whether differences existed between respondents' relationship lengths with their cell phone network providers with regard to their overall relationship intentions, an Anova was performed. Table 3 portrays the descriptive statistics for respondents' overall relationship intentions, as well as Tukey's comparisons (statistically significant at the 0.05 level) and d-values (effect sizes) when comparing respondents' length with their cell phone network providers with regard to their overall relationship intentions.

Table 3 indicates that there were neither statistically nor practically significant differences relating to respondents' relationship lengths with their cell phone network providers and their overall relationship intentions. It can therefore be concluded that respondents' overall relationship intentions do not differ based on their relationship length with cell phone network providers.

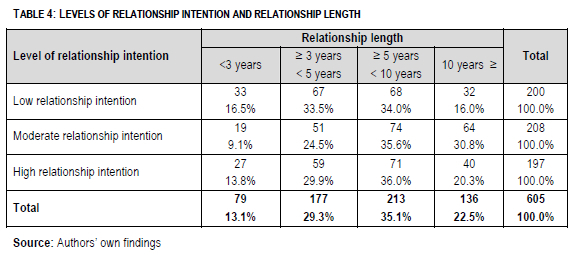

The results of a cross-tabulation between respondents' levels of relationship intention and relationship length with their cell phone network providers are shown in Table 4.

From the cross-tabulation in Table 4, it can be observed that about one third of respondents with low relationship intentions (34%), respondents with moderate relationship intentions (35.6%), and respondents with high relationship intentions (36%) have a relationship length equal or longer than 5 years, but less than 10 years with their cell phone network providers.

To determine whether respondents' levels of relationship intention were associated with their relationship lengths with their cell phone network providers, a Chi-square test for independence was performed. The test realised a significance level of p=0.007, indicating a statistically significant association between respondents' levels of relationship intention and their relationship length. The effect size is, however small (w=0.121), and therefore not of practical significance. It can therefore be concluded that there is no association between respondents' levels of relationship intention and their relationship lengths with their cell phone network providers.

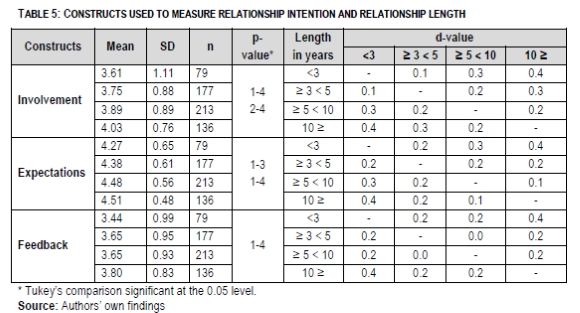

To determine whether differences existed for respondents' relationship lengths with their cell phone network providers with regard to the five constructs used to measure relationship intention, Anovas were performed. Table 5 depicts the Anovas for which statistical significant differences between the means of respondents' relationship lengths with their cell phone network providers with regard to involvement, expectations, and feedback, existed.

As shown in Table 5, statistical significant differences relating to respondents' relationship lengths and involvement, expectations and feedback were found. However, the effect sizes between relationship length and involvement, expectations and feedback were small and therefore not of practical significance. It can therefore be concluded that respondents' view of the five constructs used to measure relationship intention do not differ with regard to their relationship lengths with their cell phone network providers.

5.6 Relationship intention and contractual agreements

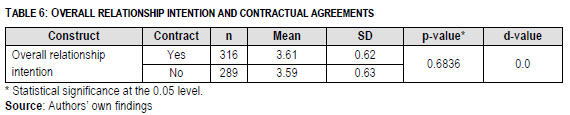

A t-test was performed to determine if a difference existed between the means of respondents with and without contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers with regard to their overall relationship intentions. Table 6 presents the descriptive statistics for respondents' overall relationship intentions as well as statistical significance at the 0.05 level and d-value (effect size) when comparing the means of respondents with and without contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers.

Table 6 indicates that there was neither a statistically nor practically significant difference relating to the presence or absence of contractual agreements with respondents' cell phone network providers and their overall relationship intentions. It can therefore be concluded that respondents' overall relationship intentions do not differ based on whether respondents have contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers.

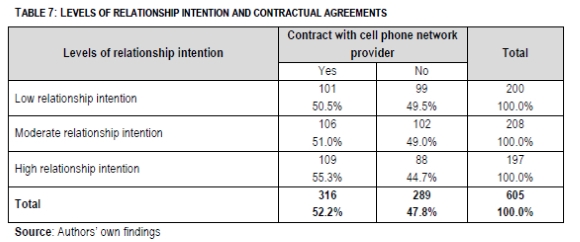

The results of a cross-tabulation between respondents' levels of relationship intention and contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers are shown in Table 7.

Table 7 indicates that half of the respondents with low relationship intentions (50.5%), respondents with moderate relationship intentions (51.0%), and respondents with high relationship intentions (55.3%) have contracts with their cell phone network providers. To determine whether respondents' levels of relationship intention were associated with the presence or absence of a contractual agreement with their cell phone network providers, a Chi-square test for independence was performed. The test realised a significance level of p=0.568 indicating no statistically significant association between respondents' levels of relationship intention and their contractual agreements. It can therefore be concluded that respondents' levels of relationship intention are not associated with whether they have contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers.

T-tests were performed to determine if differences between the means of respondents with and without contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers existed with regard to the five constructs used to measure relationship intention. A statistical significant difference was found between respondents with a contract and respondents without a contract with their cell phone network providers concerning forgiveness. However, the effect size between respondents with a contract with their cell phone network providers and respondents without a contract for forgiveness was small and therefore not of practical significance. It can therefore be concluded that respondents' view of the five constructs used to measure relationship intention do not differ with regard to whether they have a contractual agreement with their cell phone network providers.

6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Due to increased competition within the South African cell phone industry (ICASA 2012:3, 39), long-term relationships with customers (established through relationship marketing efforts) can result in customer retention (Coulter & Ligas 2004:489; Sheth & Parvatiyar 2002:4), providing a sustainable competitive advantage to cell phone network providers. For this reason, cell phone network providers may consider customers' relationship lengths (Seo et al. 2008:192) or contractual agreements (Nel & Boshoff 2012:Internet) to identify customers for relationship building. However, only customers with relationship intentions will be receptive to relationship marketing efforts (Kumar et al. 2003:669). Examining cell phone users' relationship intentions towards their cell phone network providers to identify customers for relationship building and retention is thus important. This study examined relationship intention as well as the influence of relationship intention on relationship length and contractual agreements within in the South African cell phone industry. Results indicated that the measure of relationship intention was reliable and valid to measure the relationship intentions of respondents residing in Gauteng towards their cell phone network providers.

Results furthermore indicated that: respondents' overall relationship intentions do not influence relationship length with cell phone network providers; respondents' levels of relationship intention are not associated with relationship length with cell phone network providers; and respondents' view of the five constructs used to measure relationship intention do not differ with regard to their relationship length with cell phone network providers. For this reason, respondents' relationship length with their cell phone network providers should not be used in isolation as an indicator of their relationship intentions towards their cell phone network providers. Rather, as proposed by Kumar et al. (2003:673), the value of relationship intention lies in the lifetime value of customers with high relationship intentions, which increases the profitability of these customers for service providers for the duration of their relationships. Relationship marketing efforts based on the length of customers' relationships with their cell phone network providers, will thus not necessarily generate high return on investment, as forces other than customers' relationship intention, like switching costs (Jones et al. 2007:337), can influence the length of customers' relationships with their cell phone network providers. It is therefore recommended that cell phone network providers should rather identify customers with relationship intentions for relationship marketing purposes.

Furthermore, respondents' overall relationship intentions do not influence whether respondents have contractual agreements with cell phone network providers. There is no association between respondents' levels of relationship intention and whether they have contractual agreements with cell phone network providers, and respondents' view of the five constructs used to measure relationship intention do not differ with regard to whether respondents have contractual agreements with cell phone network providers. These findings support the notion that increased competition in the cell phone industry renders cell phone network providers' use of contracts to retain customers less effective, and focusing on enhanced customer relationships will be more profitable (Seo et al. 2008:194). Contractual agreements will only lock customers into relationships with cell phone network providers for the duration of the contract, and as soon as the contract expires, customers without relationship intentions towards their cell phone network providers may churn and switch to another cell phone network provider. It is recommended that cell phone network providers should not use customers' contractual agreements to identify customers for relationship building, but should rather identify customers with relationship intentions for relationship marketing purposes.

In summary, this study attributes the reason for some customers to stay in relationships with cell phone network providers to customers' relationship intentions and not relationship length or contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers. Therefore, South African cell phone network providers can retain customers within the competitive cell phone industry through relationship marketing strategies targeted at relationship intention customers.

7. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Generalising the findings of this study is limited to those respondents living in Gauteng who participated in this study. Furthermore, as 80% of urban and 94% of rural South African cell phone users do not have contractual agreements with their cell phone network providers (World Wide Worx, 2012:Internet), the almost equal divide between respondents concerning contractual agreements is another limitation of the study which should be addressed in future research. As non-probability convenience sampling was used, future research with a different methodological approach, including probability sampling and longitudinal data, is advised.

Furthermore, this study did not examine the antecedents of relationship intention. In future, the antecedents of relationship intention, namely firm equity, brand equity and channel equity as proposed by Kumar et al. (2003:671-672), and other possible antecedents like personality, social class and attitude towards cell phone network providers, should be investigated to determine if cell phone network providers can increase customers' relationship intentions, or whether relationship intention is an inherent customer characteristic that cannot be influenced by service providers' efforts. Also, customers may be interested in building relationships with service providers in one situation, while not in other situations (Grönroos 2004:110). Some customers may for example have strong emotional attachments to their healthcare, financial services, hair care and automotive repair service providers (Coulter & Ligas 2004:489). Future research could examine whether these emotional attachments take form in terms of relationship intention by replicating the study in other service contexts. The influence of demographic variables such as age and gender on relationship intention can also be investigated to give a more coherent picture of customers with relationship intentions.

REFERENCES

BAGOZZI RP. 1994. Structural equation models in marketing research: basic principles. In BAGOZZI RP (ed). Principles of marketing research. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Business. p. 317-385. [ Links ]

BEETLES AC & HARRIS LC. 2010. The role of intimacy in service relationships: an exploration. Journal of Services Marketing 24(5):347-358. [ Links ]

BERGER G, SINHA A & PAWELCZYK K. 2012. South African mobile generation: study on South African young people on mobiles. [Internet: www.unicef.org/southafrica/SAF_resources_mobilegeneration.pdf; downloaded on 2013-02-26. [ Links ]]

BERRY LL. 1995. Relationship marketing of services - growing interest, emerging perspectives. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23(4):236-245. [ Links ]

BERRY LL. 2002. Relationship marketing of services - perspectives from 1983 and 2000. Journal of Relationship Marketing 1(1):59-77. [ Links ]

BLOEMER J & DE RUYTER K. 1999. Customer loyalty in high and low involvement service settings: the moderating impact of positive emotions. Journal of Marketing Management 15:315-330. [ Links ]

BURNHAM TA, FRELS JK & MAHAJAN V. 2003. Consumer switching costs: a typology, antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 31 (2):109-126. [ Links ]

CHELMINSKI P & COULTER RA. 2011. An examination of consumer advocacy and complaining behavior in the context of service failure. Journal of Services Marketing 25(5):361-370. [ Links ]

CHOY JY, LAM SY & LEE TC. 2012. Service quality, customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions: review of literature and conceptual model development. International Journal of Academic Research 4(3): 11-15, May. [ Links ]

CHUNG E & BEVERLAND M. 2006. An exploration of consumer forgiveness following marketer transgressions. Advances in Consumer Research 33:98-99. [ Links ]

COHEN J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

COULTER RA & LIGAS M. 2004. A typology of customer-service relationships: the role of relational factors in classifying customers. Journal of Services Marketing 18(6):482-493. [ Links ]

DAGGER TS & DAVID ME. 2012. Uncovering the real effect of switching costs on the satisfaction-loyalty association. The critical role of involvement and relationship benefits. European Journal of Marketing 46(3/4):447-468. [ Links ]

DALZIEL N, HARRIS F & LAING A. 2011. A multidimensional typology of customer relationships: from faltering to affective. International Journal of Bank Marketing 29(5):398-432. [ Links ]

DUBÉ L & MENON K. 2000. Multiple roles of consumption emotions in post-purchase satisfaction with extended service transactions. International Journal of Service Industry Management 11(3):287-304. [ Links ]

ENGESETH S. 2006. Tap into couture and customers. Brand Strategy 200:36-37, Mar. [ Links ]

GILLWALD A. 2005. Good intentions, poor outcomes: telecommunications reform in South Africa. Telecommunications Policy 29:469-491. [ Links ]

GRAYSON K & AMBLER T. 1999. The dark side of long-term relationships in marketing services. Journal of Marketing Research 36(1):132-141, Feb. [ Links ]

GRÖNROOS C. 1984. A service quality model and its marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing 18(4):36-44. [ Links ]

GRÖNROOS C. 2004. The relationship marketing process: communication, interaction, dialogue, value. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 19(2):99-113. [ Links ]

GWINNER KP, GREMLER DD & BITNER MJ. 1998. Relational benefits in services industries: the customer's perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 26(2):101-114. [ Links ]

HABARI MEDIA. 2012. Fine-tuning your mobile marketing communications for maximum impact. [Internet: www.bizcommunity.com/Print.aspx?1=196&c=78&ct=1&ci=86758; downloaded on 2013-01-09. [ Links ]]

HAENLEIN M & KAPLAN AM. 2012. The impact of unprofitable customer abandonment on current customers' exit, voice, and loyalty intentions: and empirical analysis. Journal of Services Marketing 26(6):458-470. [ Links ]

HESS J, STORY J & DANES J. 2011. A three-stage model of consumer relationship investment. Journal of Product & Brand Management 20(1):14-26. [ Links ]

HOMBURG C & GIERING A. 2001. Personal characteristics as moderators of the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty - an empirical analysis. Psychology & Marketing 18(1):43-66. [ Links ]

HOMBURG C, GIERING A & MENON A. 2003. Relationship characteristics as moderators of the satisfaction-loyalty link: finding in a business-to-business context. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing 10(3):35-62. [ Links ]

INDEPENDENT COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY OF SOUTH AFRICA (See reference). 2012. Strategic plan for the fiscal years 2013-2017. [Internet: www.icasa.org.za/Portals/0/Regulations/Annual%20Reports/StrategicPlan13-17/SPlan1317.pdf; downloaded on 2013-03-18. [ Links ]]

JENA S, GUIN KK & DASH SB. 2011. Effect of relationship building and constraint-based factors on business buyers' relationship continuity intention. Journal of Indian Business Research 3(1):22-42. [ Links ]

JONES MA, REYNOLDS KE, MOTHERBAUGH DL & BEATTY SE. 2007. The positive and negative effects of switching costs on relational outcomes. Journal of Service Research 9(4):335-355. [ Links ]

KINARD BR & CAPELLA ML. 2006. Relationship marketing: the influence of consumer involvement on perceived service benefits. Journal of Services Marketing 20(6):359-368. [ Links ]

KRUGER L & MOSTERT PG. 2012. Young adults' relationship intentions towards their cell phone network operators. South African Journal of Business Management 43(2):41-49. [ Links ]

KUMAR V, BOHLING TR & LADDA RN. 2003. Antecedents and consequences of relationship intention: implications for transaction and relationship marketing. Industrial Marketing Management 32(8):667-676, Nov. [ Links ]

LAM SY, SHANKAR V, ERRAMILLI MK & MURTHY B. 2004. Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty and switching costs: an illustration from a business-to-business service context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 32(3):293-311, Summer. [ Links ]

LIANG CJ & WANG WH. 2006. The behavioural sequence of the financial services industry in Taiwan: service quality, relationship quality and behavioural loyalty. Service Industries Journal 26(2):119-145, Mar. [ Links ]

LONG-TOLBERT SJ & GAMMOH BS. 2012. In good and bad times: the interpersonal nature of brand love in service relationships. Journal of Services Marketing 26(6):391-402. [ Links ]

MASCARENHAS OA, KESAVAN R & BERNACCHI M. 2004. Customer value-chain involvement for co-creating customer delight. Journal of Consumer Marketing 21 (7):486-496. [ Links ]

MASON C & SIMMONS J. 2012. Are they being served? Linking consumer expectation, evaluation and commitment. Journal of Services Marketing 26(4):227-237. [ Links ]

MBENDI. 2011. Communications and infrastructure. [Internet: www.mbendi.com/land/af/sa/p0005.htm#30; downloaded on 2012-03-08. [ Links ]]

McCULLOUGH ME, WORTHINGTON EL & RACHAL KC. 1997. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73(2):321 -336. [ Links ]

MOORE ML, RATNESHWAR S & MOORE RS. 2012. Understanding loyalty bonds and their impact on relationship strength: a service frim perspective. Journal of Services Marketing 26(4):253-264. [ Links ]

MORRISSON O & HUPPERTZ JW. 2010. External equity, loyalty program membership and service recovery. Journal of Services Marketing 24(3):244-254. [ Links ]

MOSTERT PG. 2012. Understanding consumers' intentions in building long-term relationships with organisations. Potchefstroom Campus: North-West University. (Inaugural Address, 23 Feb. 2012. [ Links ])

NEL D & BOSHOFF C. 2012. Customer equity drivers predicting brand switching: a multinomial logit model. Stellenbosch: Southern African Institute for Management Scientists (SAIMS). (Date of conference: 9-11 Sept. 2012; work-in-progress presentation. [ Links ])

OLIVER RL. 1980. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research 17(4):460-469. [ Links ]

O'SULLIVAN J, EDMOND D & TER HOFSTEDE A. 2002. What's in a service? Towards accurate description of non-functional service properties. Distributed and Parallel Databases 12:117-133. [ Links ]

PALLANT J. 2010. SPSS Survival manual. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PETTY RE, CACIOPPO JT & SCHUMANN D. 1983. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: the moderating role of involvement. Journal of Consumer Research 10(2): 135-146. [ Links ]

PRICE LL & ARNOULD EJ. 1999. Commercial friendships: service provider-client relationships in context. Journal of Marketing 63(4):38-56, Oct. [ Links ]

RUIZ DM, CASTRO CB & ARMARIO EM. 2007. Explaining market heterogeneity in terms of value perceptions. Service Industries Journal 27(8):1087-1110, Dec. [ Links ]

SCOTT D & VITARTAS P. 2008. The role of involvement and attachment in satisfaction with local government services. International Journal of Public Sector Management 21 (1 ):45-57. [ Links ]

SEO D, RANGANATHAN C & BABAD Y. 2008. Two-level model of customer retention in the US mobile telecommunications service market. Telecommunications Policy 32:182-196. [ Links ]

SHETH JN & PARVATIYAR A. 2002. Evolving relationship marketing into a discipline. Journal of Relationship Marketing 1(1):3-16. [ Links ]

SPAKE DF & MEGEHEE CM. 2010. Consumer sociability and service provider expertise influence on service relationship success. Journal of Services Marketing 24(4):314-324. [ Links ]

STEYN TFJ, MOSTERT PG & DE JAGER JNW. 2008. The influence of length of relationship, gender and age on the relationship intention of short-term insurance clients: an exploratory study. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 11 (2):139-156, Jun. [ Links ]

TAYLOR SA. 2007. The addition of anticipated regret to attitudinally based, goal-directed models of information search behaviours under conditions of uncertainty and risk. British Journal of Social Psychology 46:739-768. [ Links ]

TONTINI G & SILVEIRA A. 2007. Identification of satisfaction attributes using competitive analysis of the improvement gap. International Journal of Operations and Production Management 27(5):482-500. [ Links ]

TSARENKO Y & TOJIB DR. 2011. A transactional model of forgiveness in the service failure context: a customer-driven approach. Journal of Services Marketing 25(5):381-392. [ Links ]

TUOMINEN P. 2007. Emerging metaphors in brand management: towards a relational approach. Journal of Communication Management 11 (2):182-191. [ Links ]

VAN NIEKERK L. 2012. South Africa yearbook 2011/12 - Communications. [Internet: www.gcis.gov.za/sites/www.gcis.gov.za/files/docs/resourcecentre/yearbook2011/10_Communications.pdf; downloaded on 2013-03-18. [ Links ]]

VÁZQUEZ-CASIELLES R, SUÁREZ-ÁLVAREZ L & BELÉN DEL RÍO-LANZA A. 2009. Customer satisfaction and switching barriers: effects on repurchase intentions, positive recommendations, and price tolerance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 39(10):2275-2302. [ Links ]

VERHOEF PC, FRANSES PH & HOEKSTRA JC. 2002. The effect of relational constructs on customer referrals and number of services purchased from a multiservice provider: does age of relationship matter? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30(3):202-216. [ Links ]

WORLD WIDE WORX. 2012. Mobility 2012. The mobile consumer in South African 2012. Executive summary. [Internet: www.worldwideworx.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Exec-Summary-The-Mobile-Consumer-in-SA-2012.pdf; downloaded on 2013-02-25. [ Links ]]

WIRTZ J, TAMBYAH SK & MATTILA AS. 2010. Organizational learning from customer feedback received by service employees: a social capital perspective. Journal of Service Management 21 (3):363-387. [ Links ]

ZEITHAML VA, BERRY LL & PARASURAMAN A. 1993. The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 21(1):1-12. [ Links ]

ZIKMUND WG & BABIN BJ. 2010. Exploring marketing research. 10th ed. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western. [ Links ]

ZOURRIG H, CHEBAT JC & TOFFOLI R. 2009. Exploring cultural differences in customer forgiveness behavior. Journal of Service Management 20(4):404-419. [ Links ]