Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.10 no.1 Meyerton 2013

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Transformational leadership and employee engagement in the mining industry

A BezuidenhoutI; C SchultzII

IUniversity of South Africa

IITshwane University of Technology

ABSTRACT

In the South African mining industry, employee relations are highly complex and often characterised by violence and unrest. The purpose of this article is to determine if there is a relationship between transformational leadership and employee engagement at a mine in the North West Province. The methodology included a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design. The main findings were that a transformational leadership style and employee engagement are related to one another and should be considered holistically. The unique contribution of this research lies in the fact that it provides insight into the complex relationships between leaders and ordinary employees at the mine. The research considered both sides of the problem, namely from the point of view of the leaders as well as that of the ordinary employees who might be experiencing various degrees of engagement with their jobs. Recommendations for future management interventions include that leaders pay individual attention to followers, provide balanced feedback and provide opportunities for growth and development.

Key phrases: Employee relations, engagement, management interventions, mining industry, transformational leadership

1 INTRODUCTION

The death of 34 striking mineworkers and two members of the police force at a mine in the North West Province in August 2012 was a tragic experience. According to Ramphele (2012:1), this incident was a clear example of a monumental leadership failure in South Africa. It is against this backdrop of continuous labour unrest, industrial action and increasing pressure to remain globally competitive, that the importance of effective leadership and engagement is contemplated.

This article describes the results of an organisational change project that was undertaken at a leading gold mining company in the North West province of South Africa. The aim of the project was to improve the work engagement of their employees, through transformational leadership. Although the organisational change intervention falls beyond the scope of this article, it is important to note that the purpose of the intervention was to address the poor labour relations and labour unrest that the mine experienced during 2011 and 2012.

McLean (in Ya-Hui Lien, Hung & McLean 2007:9) describes organisational change as a process or activity, founded in the behavioural sciences. Over the long term, it has the potential to develop enhanced knowledge, expertise, productivity, satisfaction and interpersonal relationships, for the individual, group, organisation, community, nation, or ultimately the whole of humanity. Many authors, including Groenewald and Ashfield (2008:56), Hughes (2010:138) and Stander and Rothman (2010:8) reported on the importance of effective leadership in the successful implementation of organisational change.

Kotter (1996:63) one of the most influential writers on leadership, believes that the importance of leadership lies in the way that effective leaders view the future, align people with that vision and inspire them to make it happen. The historical development of leadership theories can be traced back to the trait theories, behavioural theories (Clegg, Kornberger & Pitis 2008:132) and the advent of contingency theories in the 1960s. Later developments included the path-goal theory, transformational leadership and visionary leadership (Palmer, Dunford & Akin 2009:249). The current research project specifically focused on the manifestation of transformational leadership within the mine and the way transformational leadership facilitated the engagement of the employees at their jobs.

Joubert and Roodt (2011:96) report that leadership has a direct relationship with employee engagement in organisations. With reference to organisational development, Clegg, Kornberger and Pitis (2008:140) are of the opinion that transformational leaders are the 'ideal people' to have during major organisational change, because they inspire employees to work towards achieving the organisation's vision. Transformational leadership includes affective and charismatic elements of leadership that resonate with workers who experience a need to be inspired and empowered in uncertain and volatile times (Hughes 2010:139).

Progressive organisations, including the mining industry, where competition is tough, expect their leaders to influence employees in such a way that they start to share common goals, attitudes and values and work towards the achievement of the organisation's vision and mission (Bartram & Casimir 2007:12). Consequently, the question arose as to how the leadership at the mine could use transformational leadership in order to improve employee engagement. It is against this background of continuous labour unrest, demonstrations, violence and the tragic loss of lives that this article describes explores the phenomena of transformational leadership and employee engagement.

Although previous studies have investigated leadership styles in general, the contribution of this article lies in its perspective on the combination of a transformational leadership style and the engagement of the employees to address problematic employee relations holistically. The investigation being reported here focused on the relationship between the leadership style and the work engagement of the ordinary employees at the plant. An effort was made to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complexity of human relations at the mine.

Mokgolo, Mokgolo and Modiba (2012:8-9) also recommended that future research on transformational leadership in South Africa should study the relationship between transformational leadership and constructs such as organisational citizenship behaviour and commitment. As engagement is a construct that falls within the same positive organisational behaviour paradigm, this article will address an already identified need within the South African business research literature. Therefore it is postulated that the objectives of management at the mine will be better served if transformational leadership and employee engagement is not viewed in isolation, but as interdependent.

Against this background, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H1: Transformational leadership and employee engagement is significantly related to one another in a mine in the North West Province of South Africa.

The aim of this article was to investigate the possibility of using a transformational leadership style in order to improve the experience of work engagement of the employees at this site. The issue is thus addressed from the perspective of both the leader as well as the follower. The research methodology consists of a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design. The article includes a literature overview of transformational leadership and work engagement. The research method is briefly discussed, empirical results are given and discussed, conclusions are drawn and recommendations provided.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

An overview of the most prominent literature on the research constructs is provided.

2.1 Transformational leadership

Transformational leadership has developed from seminal research by Bass (1990:21; Gibson, Ivancevich, Donnely & Konopaske 2012:357). Bass (1990:21) identified five factors, namely charisma, individual attention, intellectual stimulation, contingent reward and management by exception that describe transformational leaders. Kotter (1995:61) postulated that organisational change is a multistep process, which could never succeed without strong, high-quality, transformational leadership. He consequently conceptualised an eight-stage process for leading major change in organisations. The eight stages are establishing a sense of urgency, creating coalitions, developing a vision and strategy, communicating the vision, empowerment, generating short-term wins, consolidation and anchoring changes in the organisational culture.

Transformational leadership includes affective and charismatic elements of leadership that resonate with workers who experience a need to be inspired and empowered in uncertain and volatile times (Hughes 2010:139). Where transactional leaders focus on established goals by clarifying task requirements, a transformational leader goes beyond the task. Gibson et al. (2012:356) explain that transformational leaders have the ability to inspire and motivate followers to achieve results greater than originally planned by re-inventing the entire philosophy, system and culture of the organisation.

Groenewald and Ashfield (2008:56) found that transformational leadership reduces the effects of uncertainty and change and effectively guides employees to attain their occupational goals. Transformational leaders inspire their followers to transcend their own self-interests for the good of the organisation, and tend to have a profound affection for their followers. Furthermore, these leaders create a work environment in which both organisational and individual needs are acknowledged and where productivity is emphasised, while the leaders remain sensitive towards ordinary employees' work experience (Marquis & Huston 2008:422).

Transformational leadership emphasises the affective and interpersonal elements of leadership, necessary to succeed in volatile and uncertain times (Bass 1990:21). Transformational leaders have the ability to align individual work goals and the organisation's strategic goals. Hence, while employees are inspired to achieve personal work goals, they are creating organisational momentum towards achieving strategic goals. Transformational leadership is conceptualised as a process of engaging with subordinates, creating a common understanding and raising the level of motivation of both the leader and the follower. For the purpose of this article charisma, individual attention, intellectual stimulation, contingent reward, management by exception, effective communication, development and work climate are accepted as evidence of transformational leadership (Gibson et al. 2012:358).

2.2 Work engagement

The concept employee work engagement originated from a positive organisational behaviour paradigm in the late 1990s, but is not an easy concept to define (Ghafoor, Qureshi, Khan & Hijazi 2011:7395; Macey & Schneider 2008:6). Havenga, Stanz and Visagie (2011:8806) explain that the confusion stems from the great deal of interest in the concept, as well as the fact that most of what was written was written by consulting firms whose scholarly credentials are not always transparent. In general, engagement can be regarded as the combination of a positive psychological contract and the willingness to offer discretionary behaviour by the employee (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development 2009:16).

The following comprehensive definition enjoys widespread support in the literature (Schaufeli & Bakker 2004:4),

...work engagement is a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind, characterised by three dimensions, namely vigour, dedication and absorption. Rather than a momentary state of mind, engagement refers to a more persistent and pervasive affective-cognitive state, that is not focused on any particular object, event, individual or behaviour.

Gallup (2006:Internet) describes engaged employees as employees who are 100% psychologically committed, who enjoy the challenge of their daily work, who feel their talents are used and who are always looking for innovative ways of achieving their objectives. Maslach and Leiter (1997:12) describe work engagement as being characterised by energy, involvement and efficacy, which are considered the direct opposites of the three burnout dimensions, namely exhaustion, cynicism and reduced professional efficacy. These authors believe that a focus on work engagement builds more effective organisations. Dibben, Klerck and Wood (2011:193) refer to the three different levels at which engagement is manifested, namely emotional engagement, cognitive engagement and physical engagement.

The current interest in work engagement, lead to numerous articles in the popular press, which in turn lead to some confusion among scholars. This is evident from the wide variety of definitions found in the literature. The above definitions have one aspect in common, referring to the fact that employee engagement leads to improved relationships and organisational functioning. For the purpose of this article, job satisfaction, affective engagement, cognitive engagement, behavioural engagement, discretionary effort, intention to stay, growth and perceived recognition and support are considered evidence of work engagement.

2.3 The interdependence of transformational leadership and work

engagement

Firstly, the importance of leadership in creating an enabling organisation environment is undeniable. Booysen (in Robbins, Judge, Odendaal & Roodt 2009:289) quotes Brand Pretorius, one of South Africa's most prominent business leaders, as saying that leadership is like the electricity that powers an organisation. An organisation with inspirational leadership has electricity, energy and commitment. As the pressure to remain globally competitive increases, the importance of strong leadership in the mining industry becomes even more evident.

Secondly, the relationship between employee engagement and positive organisational outcomes are evident in the following empirical findings. Companies in which 60 percent of the workforce is engaged have an average five-year return to shareholders of more than 20 percent. That compares to companies in which only 40 to 60 percent of the employees are engaged, which have average total returns to shareholders of about 6 percent (Baumruk, Gorman & Gorman 2006:25).

Thirdly, in times of uncertainty and change, the need for transformational leadership is highlighted. Groenewald and Ashfield (2008:56) found that transformational leadership reduces the effects of uncertainty and change and is effective in guiding employees towards the attainment of their job goals. Stander and Rothman (2010:8) mention that the work climate created by managers contributes directly to subordinates' feelings of self-worth and sense of self-determination.

Finally, there is a growing awareness of the importance of transformational leadership from the line manager in the shaping of human resource functions, including employee development (Boselie 2010:212). Stander and Rothman (2010:10) concur with Boselie by stating that transformational leaders develop followers' potential. The direct supervisor plays an essential role in the development of an employee with specific reference to knowledge, skills and abilities (Boselie 2012:216). Mokgolo et al. (2012:8) postulate that transformational leadership is "vital" for organisational success. The research on which this article is based, addressed this need within the South African research literature.

3 METHODOLOGY

A quantitative research design, in the form of a self-report, cross-sectional survey was used. The instrument was developed based on the literature, and it was submitted to a panel of experts to ensure face validity. It was consequently tested via a pilot study to refine it before distribution. The instrument consisted of a biographical section, a section measuring employee engagement and a section measuring transformational leadership.

The total population at this specific plant consisting of 291 workers was invited to participate. Of the 165 questionnaires that were distributed, 121 questionnaires were completed, resulting in a 73% response rate, which can be judged a representative percentage of the population.

3.1 Results

The biographical profile of the sample can be summarised as follows:

There was a good spread of respondents throughout the different age categories. Only 5% were below 25 years of age, while only 7.4% fell between 36 and 40. The remainder of the respondents were spread fairly equally among the various age categories between 18 and 65 years. It is noteworthy that the vast majority of the sample was older than 25 years. The majority of respondents (74.4%) were male, as could be expected in this environment. IsiXhosa, Sesotho, Setswana and Afrikaans were the languages that were spoken by the majority of the sample. Most of the respondents were born in the North West (44.4%), followed by the Free State (25.6%) and the Eastern Cape (12%). The largest single group of respondents (28.6%) were in possession of a Grade 12 certificate, while 34.5% had a higher qualification and 37% a lower qualification.

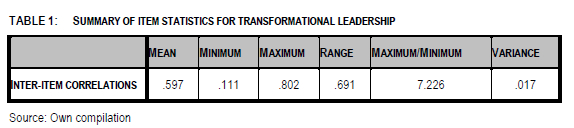

The reliability of the current study questionnaire was established through internal consistency reliability. Internal consistency reliability means that the different questions measure the same underlying dimensions (Louw & Edwards 2005:341). A Cronbach's alpha value of 0.7 is generally judged acceptable (Nunnally & Bernstein 1994:121). The Cronbach's alpha of the transformational leadership dimensions were 0,958. Inter-item correlations (as presented in Table 1) also indicated a high level of reliability.

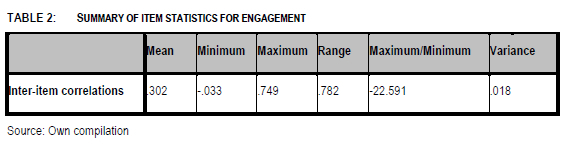

The Cronbach's alpha of the engagement dimensions was 0,881. In addition, the inter-item correlations for the engagement scale were also high, as demonstrated by the statistics in Table 2.

Based on the empirical evidence it can thus be concluded with confidence that the instrument was reliable and that it may therefore be expected to deliver the same results if used again.

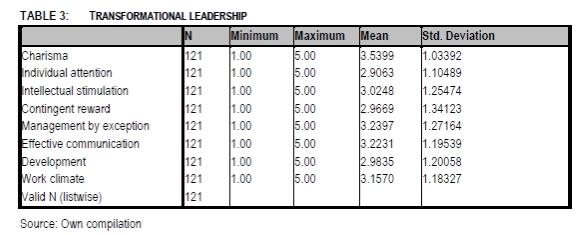

Regarding the frequencies, respondents were asked to indicate their answers on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 representing strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 uncertain, 4 agree, and 5 strongly disagree. Table 3 presents statistical scores on the eight transformational leadership dimensions measured:

From the above table, it is noteworthy that the subscales rated most positively were charisma (3.54) and management by exception (3.24). It should be noted that no mean score reached a 4 (agree). Possible areas for development at this mine were represented by the dimensions of individual attention, contingent reward and development, with the lowest score for individual attention (2.91). Table 4 presents the mean scores for the engagement dimensions.

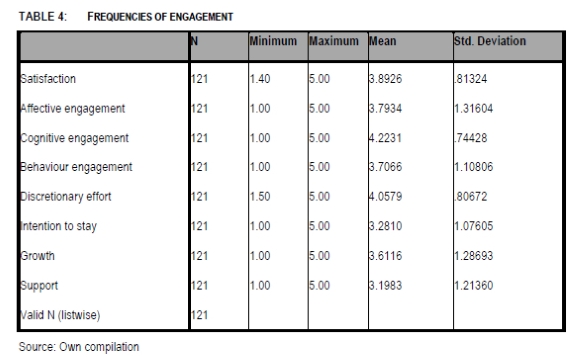

It appears that the highest mean score on the 5-point scale was obtained with regard to cognitive engagement (4.22) followed by discretionary effort (4.06) and satisfaction (3.89). The higher the mean score, the higher the level of agreement with the statements indicated. The lowest mean scores were obtained on the intention to stay (3.28) and the support (3.20) subscales. It should be noted that the mean score were fairly high overall, ranging from 3.20 to 4.22.

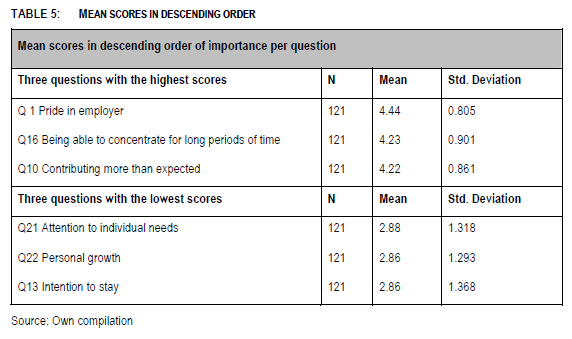

The scores on the transformational leadership scale, as well as the employee engagement scales were combined and re-arranged in descending order of means (Table 5), as this provided an overview of the most pertinent aspects at the mine, rated both positively and negatively. The three questions with the highest scores and the three questions with the lowest scores are listed in Table 5.

From the above synthesis it was deduced that in general employees were proud to work for the mine, they were able to concentrate for long periods and from their point of view, they contributed more than what was expected from them. On the negative side of the spectrum they did not perceive that their superiors paid attention to their personal needs, their need for personal growth was not met and they scored fairly low on the "intention to stay" question. This implied that they would consider alternative employment, should the opportunity arise.

3.2 Correlation between transformational leadership and engagement

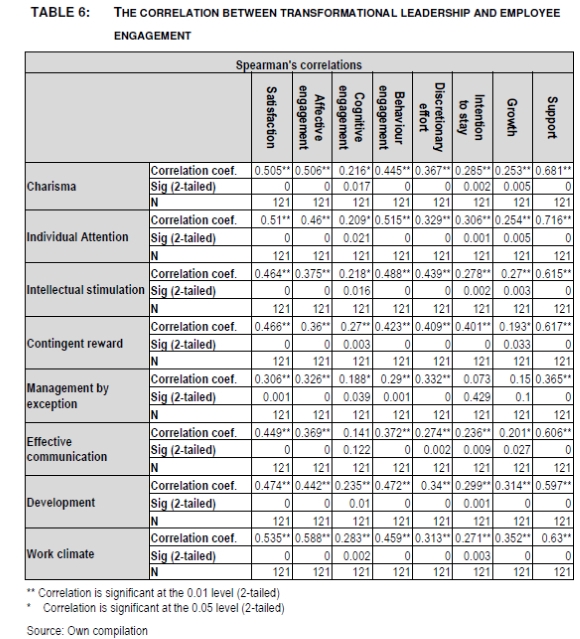

The purpose of this section is to determine if there is a statistically significant correlation between transformational leadership and engagement at this mine. A Spearman's rho was calculated between the leadership and employee engagement scales respectively. The results are reported below in Table 6.

The probability (p-value) was used to determine whether the correlation was statistically significant. Significance was indicated when the p-value was less than 0,01 (significant at a 1% level of significance) and less than 0,05 (significant at a 5% level of significance). However, due to the fact that statistical significance is influenced by sample size, practical significance in the form of effect size was also taken into account. Cohen (1993:1151) suggests that a correlation of 0.5 is large, 0.3 is moderate, and 0.1 is small. Since all correlations in the table above were statistically significant above 0.2, a judgement decision was made to focus on correlations above 0.4 in the discussion.

Based on the empirical evidence, the hypothesis was therefore accepted:

H1: Transformational leadership and employee engagement is significantly related to one another in a mine in the North West Province of South Africa.

3.3 Analysis and interpretation

From the above synthesis it was deduced that in general employees were proud to work for the mine, they were able to concentrate for long periods and felt that they contributed more than what was expected of them. Conversely, they did not perceive that their superiors paid attention to their personal needs, their needs for personal growth were not met and they scored fairly low on the "intention to stay" question (implying that they would be vulnerable to external recruitment efforts).

It is noteworthy that the transformational leadership dimensions rated most positively were charisma (3.54) and management by exception (3.24). It should be noted that no mean score reached a 4 (agree).The lowest scores, and possible areas for development were obtained with regard to individual attention (2.91), contingent rewards (2.97) and development (2.98). The highest engagement mean score was obtained with regard to cognitive engagement (4.22) followed by discretionary effort (4.06) and satisfaction (3.89). The lowest mean scores were obtained on the intention to stay (3.28) and support (3.20) subscales. It should be noted that the mean scores were fairly high overall, ranging from 3.20 to 4.22.

From Table 6, an undeniably strong relationship between all the constructs of transformational leadership and engagement emerged. It appeared that the strongest predictors of affective engagement were work climate and charisma (p=0.588 and 0.506 respectively). This implied that the charismatic transformational leaders who manage to create a work climate that enables subordinates to achieve their work goals, are expected to be highly successful in engaging employees. The empirical findings were in accordance with the findings by Babcock-Roberson and Strickland (2010: 322); Khatri, Templer and Budhwar (2012: 58) and Sandberg and Moreman (2011: 239). These authors found a similar trend that indicated a link between the charismatic dimension of transformational leadership and engagement.

Other transformational leadership dimensions that were highly predictive of engagement were the ability to pay individual attention to subordinates and to be perceived as a leader who is concerned with their development (p=0.460 and 0.442 respectively). The fact that the results indicated a low score on ability to pay individual attention at the mine, is concerning, as it will not be conducive to employee engagement at the mine. In a similar fashion, satisfaction of the ordinary employees was best predicted by work climate, individual attention (in accordance with the findings by Moss, 2009: 241) and charisma (p=0.535, 0.510 and 0.505 respectively).

Again the low score on individual attention should be a warning sign. Other predictors of satisfaction included development (p=0.474), contingent reward (p=0.466), intellectual stimulation (p=0.464) and effective communication (p=0.449). As the development dimension was also identified as a development area at the mine, it is to be expected that the satisfaction of employees might suffer as a result of this. Moss (2009:241) specifically notes that transformational leaders should create opportunities for development and a "promotional focus" in order to cultivate engagement in followers.

No transformational leadership scales were practically significant predictors of cognitive engagement, or of the growth sub-dimension, because no correlations reached 0.3. These empirical findings could indicate that the transformational leadership style was less effective in engaging employees at a cognitive level and in creating the perception that they have the opportunity to grow and develop at this mine.

Behaviour engagement was significantly related to most of the leadership scales, in particular individual attention (p=0.515), intellectual stimulation (p=0.488), development (p=0.472), work climate (p=0.459) and charisma (p=0.445). The degree of discretionary effort was significantly related to intellectual stimulation (p=0.439) and contingent reward (p=0.409). Intention to stay showed only one correlation above 0, 4 and that was with contingent reward (p=0.401). No other leadership scales were significantly related to the intention to stay.

The score on the support subscale was strongly related to all of the leadership scales, with the exception of management by exception. Correlations were large in effect, ranging from 0.597 (development) to 0.716 (individual attention). In summary, it would appear that the engagement dimensions of satisfaction and support showed the strongest relation with all of the leadership scales (with the exception of management by exception). Affective and behaviour engagement showed a number of significant correlations with various leadership scales, while discretionary effort and intention to stay only showed one or two relationships with leadership scales. The engagement dimensions of cognitive engagement and growth did not show any meaningful relationship to leadership at this mining plant.

The success of any change process depends on the strength of the leadership of the process. Transformational leadership engages people to create, adapt and meet the demands of the anticipated future (University of Adelaide 2010). Leadership inspires and energises the change process. In short, leadership engages the hearts and minds of the workers. The implication is that the engagement of the staff at this mine is dependent on the strength of the leadership at the mine.

Although the results of this research project measured an overall high level of engagement among employees, there were development areas that should be addressed to improve the workers' experience of their jobs. Employee engagement may be enhanced by assisting employees with cognitive engagement and achieving personal growth. This can be done by explaining the link between the employees' job and the organisation's mission and the importance of the employees' ability to maintain concentration for long periods, while performing their jobs. When employees understand the alignment between their jobs and the organisation's mission it facilitates cognitive engagement on the part of the employees. Furthermore, challenging assignments create an opportunity for employees to explore their true potential and to practice the skills that they have not yet mastered. It is the role of leaders to constantly challenge the status quo and to expect a lot from their employees.

The interaction between leadership and engagement is also evident in the "growth" and "development" dimensions. In order to experience support and perceive that there are opportunities for growth and development, it is essential that the leader actively work towards creating an organisational climate that is conducive to growth and development. Globally, issues such as the identification of potential, talent management, retention of valuable staff members and succession planning are receiving increased research attention in order to remain competitive.

The empirical results indicated that transformational leadership could indeed be used as a vehicle to effectively engage employees at the mine in the North West.

5. Conclusion

The research on which this article is based, set out to prove the relationship between a transformational leadership style and employee engagement at a mine in the North West Province. The results indicated a reciprocal relationship between the two constructs with reference to this mine. This implies that, if management at the mine wants to address employee engagement, they should look holistically at the situation. Any effort to improve employee engagement has to be accompanied by an investigation into the leadership style at the organisation. If the leadership is not mature enough to enable their employees to cope with change and upheaval and to remain engaged throughout the change process, the stability and prosperity of the organisation are in jeopardy.

The literature review confirmed an increased need for transformational leadership at times of uncertainty and change and furthermore suggested a link between transformational leadership and employee engagement. As the mining industry in South Africa struggles to come to terms with an environment which is as volatile as ever, the empirical evidence in this research provided support for the existence of an interdependent relationship between employee engagement and transformational leadership. Therefore, a case is made that, in order to engage employees in the mining industry, transformational leadership is required to address the problems.

The variables that were perceived as particularly high by the respondents were the fact that they were proud to work for this employer, they felt that they had the ability to concentrate for long periods of time on their respective tasks and that they contributed more to the success of the organisation than what was expected of them. On the negative side of the continuum, the lowest scores were calculated for the attention that was paid to individual needs and the employees' perception that they had opportunities for personal growth at the mine. Alarmingly, the lowest score was calculated for employees' intention to stay, which indicated that they could consider alternative employment if an attractive offer was received. Furthermore, the empirical evidence was in favour of a strong relationship between transformational leadership and engagement. This lead to the conclusion that, in order to improve employee engagement, a transformational leadership style was imperative. It would be a futile to invest energy, time and money on the one, without considering the other.

Based on the results of this research, it is recommended that engagement be increased by encouraging leaders to use a transformational leadership style. However, many leaders may need to learn the skills necessary to lead in a transformational way. Leaders should be encouraged to clarify the link between the employee's job and the organisation's mission. When employees understand the alignment between their jobs and the organisation's mission it facilitates cognitive engagement. Furthermore, it is recommended that leaders enable employees to attend learning opportunities and give them challenging assignments to explore their potential and practice high level skills.

The empirical results highlighted the importance of giving recognition to employees when deserved and not just in the form of "managing by exception". Timely, constructive and balanced feedback is important. Discussions with subordinates should inform the level and nature of support. Leaders ought to provide contingent rewards to their employees, through negotiation, to ensure that employees receive the rewards they prefer. This implies that the transformational leader should have the ability to formulate and set well-defined goals that are clearly understood and supported by the employees. The leadership at the mine can be addressed by developing the leaders' ability to pay individual attention to their subordinates, keeping them intellectually stimulated and encouraging creativity. The formal policies at the mine should enable supervisors to empower employees to take ownership for streamlining operations and administration. In order for employees to perceive that there are opportunities for growth the leader should work towards creating an organisational climate that is conducive to growth and development.

This article described the situation at one mine in the North West Province of South Africa. This is a limitation of the current research, as generalisations cannot be made from one mine. As the research project is continuing, other mines will be included in the investigation, to enlarge the population size and to enable comparisons between the various data sets and to enable generalisations from the data to be made.

In conclusion, it could be argued that the constant pressure to be productive leave leaders in the mining industry without any time for building interpersonal relationships, or for being concerned with the engagement of their subordinates. For this reason, the results of a global study involving more than 2 000 companies in Asia, Australia, Europe and the Americas that found a strong positive relationship between engagement and financial business results (Razi 2006:66) are noteworthy. From these results it can be deduced that no leader or organisation can afford to overlook the importance of employee engagement, neither do they have the luxury to ignore the engagement of their employees.

REFERENCES

BABCOCK-ROBERSON ME & STRICKLAND OJ. 2010. The relationship between charismatic leadership, work engagement, and organisational citizenship behaviours. The Journal of Psychology, 144(3):313-326. [ Links ]

BARTRAM T & CASIMIR G. 2007. The relationship between leadership and follower in-role performance and satisfaction with the leader. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 28(1):4-19. [ Links ]

BASS BM. 1990. From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organisational Dynamics, 13(3):26-40. [ Links ]

BAUMRUK R, GORMAN JR & GORMAN RE. 2006. Why managers are crucial to increasing engagement. Identifying steps managers can take to engage their workforce. Strategic HR Review, 5(2):24-7. [ Links ]

BOSELIE P. 2010. Strategic human resource management. A balanced approach. London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

CHARTERED INSTITUTE OF PERSONNEL AND DEVELOPMENT. 2009. Employee engagement. [Internet: http://cipd.co.uk/subjects/empreltns/general/empengmt; downloaded on 2012-08-24. [ Links ]]

CLEGG S, KORNBERGER M & PITIS T. 2008. Managing and organisations: an introduction to theory and practice. Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

COHEN A. 1993. Organisational commitment and turnover: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36(5):1140-1157. [ Links ]

DIBBEN P, KLERCK G & WOOD G. 2011. Employment relations. A critical and international approach. London: CIPD. [ Links ]

GALLUP. 2006. Engaged employees inspire company innovation. Gallup Management Journal. [Internet: http://gmj.gallup.com/content/default.aspx?ci=24880&pg=1; downloaded on 2012-09-11]. [ Links ]

GHAFOOR A, QURESHI TM, KHAN MA & HIJAZI ST. 2011. Transformational leadership, employee engagement and performance: Mediating effect of psychological ownership. African Journal of Business Management, 5(17):7391-7403. [ Links ]

GIBSON JL, IVANCEVICH JM, DONNELY JH & KONOPASKE R. 2012. Organizations. Behavior, structure, processes. Boston: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

GROENEWALD A & ASHFIELD G. 2008. When leaders are also explorers. The Star Workplace, 7 May, p. 56. [ Links ]

HAVENGA W, STANZ K & VISAGIE J. 2011. Evaluating the difference in employee engagement before and after business and cultural transformation interventions. African Journal of Business Management, 5(22):8804-8820. [ Links ]

HUGHES M. 2010. The leadership of change. In M. Hughes (Ed). Managing change: A critical perspective. London: CIPD. pp 135-149. [ Links ]

JOUBERT M & ROODT G. 2011. Identifying enabling management practices for employee engagement. Acta Commercii, 11:88-110. [ Links ]

KHATRI N, TEMPLER KJ & BUDHWAR PS. 2012: Great (transformational) leadership = charisma + vision. South Asian Journal of Global Business Research, 1 (1):38-62. [ Links ]

KOTTER J. 1995. Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, March - April: 59 - 67. [ Links ]

KOTTER JP. 1996. Leading change: Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

LOUW DA & EDWARDS DJA. 2005. Psychology: An introduction for students in Southern Africa. Second edition. Johannesburg: Heinemann. [ Links ]

MACEY WH & SCHNEIDER B. 2008. The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organisational Psychology, 1:3-30. [ Links ]

MARQUIS BL & HUSTON CJ. 2008. Leadership roles and management functions in nursing theory and application. Sixth edition. China: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [ Links ]

MASLACH C & LEITER MP. 1997. The truth about burnout. San Francisco, NJ: Wiley. [ Links ]

MOKGOLO MM, MOKGOLO P & MODIBA M. 2012. Transformational leadership in the South African public service after the April 2009 national elections. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 10(1 ):1-9. [ Links ]

MOSS S. 2009. Cultivating the regulatory focus of followers to amplify their sensitivity to transformational leadership. Journal of Leadership and Organisational Studies, 15(3):241. [ Links ]

NORTHOUSE PG. 2010. Leadership: theory and practice. Fifth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

NUNNALLY J & BERNSTEIN IH. 1994. Psychometric theory. Third edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PALMER I, DUNFORD R & AKIN G. 2009. Managing organisational change: a multiple perspectives approach. Second edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PECK R, OLSEN C & DEVORE J. 2008. Introduction to statistics and data analysis. Third edition. Belmont: Thomson. [ Links ]

RAMPHELE M. 2012. Leaders failed South Africa in Marikana. City Press: 1, 24 Aug. [ Links ]

RAZI N. 2006. Employing OD strategies in the globalisation of HR. Organisation Development Journal, 24(4):62-69. [ Links ]

ROBBINS SP & JUDGE TA. 2008.Essentials of organizational behavior. Upper Saddle River: Pearson. [ Links ]

ROBBINS SP, JUDGE TA, ODENDAAL A & ROODT G. 2009. Organisational behavior: Global and Southern African Perspectives. Cape Town: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

SANDBERG Y & MOREMAN CM. 2011. Common Threads among Different Forms of Charismatic Leadership. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(9):235-240. [ Links ]

SCHAUFELI W & BAKKER A. 2003. Utrecht work engagement scale: Preliminary Manual. Utrecht: Utrecht University. [ Links ]

STANDER MW & ROTHMAN S. 2010. The relationship between leadership, job satisfaction and organisational commitment. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 7(3):7-13. [ Links ]

UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE. 2010. Leading change, transition and transformation - a guide for university staff. Life impact. [Internet: www.techrepublic.com/.../leading-change-transition-and-transformation/1914073; downloaded on 2012-08-30. [ Links ]]

YA-HUI LIEN B, HUNG, RY & MCLEAN GN. 2007. Organizational Learning as an Organization development Intervention in Six High-Technology Firms in Taiwan: An exploratory case study. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 18(2):211-228. [ Links ]