Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.10 no.1 Meyerton 2013

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Investigating perceived justice in South African health care

CF de MeyerI; DJ PetzerII; G SvenssonIII; S SvariIV

IUniversity of Johannesburg

IINorth-West University

IIIOslo School of Management, University of Johannesburg

IVOslo School of Management

ABSTRACT

The health care industry plays an important role in the life of consumers since it impacts their personal well-being and those close to them. This industry involves ample customer contact resulting in service encounters that are often negative. The health care industry in South Africa is typified by large disparities between the public and private healthcare sectors. As in other industries, customer satisfaction, loyalty and consequently long-term survival of health care businesses are also influenced by customers experiencing a sense of perceived justice following a negative service encounter.

This study uncovers the perceived justice experienced by patients in both public and private health care sectors in reaction to negative service encounters. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted and the three underlying dimensions of the perceived justice concept as theorised by other authors were uncovered. Respondents perceive significant differences between these dimensions. Furthermore, public health care patients perceive significantly lower levels of procedural and distributive justice than private health care patients. The study did not uncover any differences in relation to perceived justice among respondents based on demographic characteristics. Based on the results, marketers are able to design strategies to recover from service failures and increase the perceived justice patients experience.

Key phrases: health care industry, negative service encounter, perceived justice, service failure

1. INTRODUCTION

The concept of justice following a negative service encounter has been researched in many different settings within the field of marketing. Schoefer and Diamantopoulos (2008:91-103) investigated justice within the field of complaint behaviour, while others such as DeWitt, Nguyen and Marshall (2008:269-281); Maxham and Netemeyer (2003:46-62) and Sindhav, Holland, Rodie, Addidam and Pol (2006:323-335) examined the concept of justice from a customer satisfaction and loyalty perspective. It is evident, irrespective of the area within marketing, that customers' perceived justice following a negative service encounter can influence customer satisfaction, loyalty and ultimately the success of the business (Kuo & Wu 2011:127; Schoefer, 2010:52).

Although studies on justice have been conducted in a multitude of settings, the influence of this concept within a health care setting has not been researched. The South African health care industry provides a suitable backdrop to conduct the study due to the high levels of service failures experienced by both private and public health care patients (de Jager & du Plooy 2011:103), high involvement levels of patients within health care (Perrott 2011:58), and the higher levels of accountability of health care providers pertaining to service recovery (Piligrimiené & Bučiūniené 2011:1304).

This paper provides an overview of the South African health care industry, followed by an exposition of the concept of perceived justice. The research objectives, methodology and results are subsequently presented. Finally the conclusions, recommendations and limitations of the study are proposed.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 The health care industry of South Africa

Within the health care industry in South Africa, both private and public health care sectors are major players. Extant literature provides evidence of major disparities between the two sectors. The private health care sector in South Africa serves approximately 20% of the South African population (7 million people) and spends $7 billion per year to serve private health care patients (Pharmaceutical Executive 2006:8). The South African private health care sector is rated by the World Health Organisation as the fourth best in the world and the sector is dominated by three businesses holding 80% of the market share operating 200 private hospitals (Economic Intelligence Unit 2011:9; Pharmaceutical Executive 2006:9).

In contrast, the South African public health care sector of South Africa spends $5.4 billion to serve 80% of the population (nearly 38 million people), it operates 400 hospitals and is rated amongst the worst in the world (Economic Intelligence Unit 2011:6; Pharmaceutical Executive 2006:8). The public health care sector is furthermore characterised by poor levels of services delivery, mainly because it is under-resourced, with outdated equipment and personnel shortages (de Jager & du Plooy 2011:103; Economic Intelligence Unit 2011:5; Finweek 2007:64; Pharmaceutical Executive 2006:8; Yaacob, Zakaria, Salamat, Salmi, Hasan, Razak & Rahim 2011:636). Yaacob et al. (2011:636) mention that the majority of patients in South Africa do not have a choice between the two sectors (private and public health care), since they cannot afford the services of the private health care sector. Despite this, health care is still seen as a critical purchase consumers make as their choices influence their physical and mental well-being over time. In most instances, health care providers are results oriented and do not focus on providing quality services, leading to higher levels of negative service encounters (Suki, Lian & Suki 2011:42).

2.2 Perceived justice following a negative service encounter

According to Del Rio-Lanza, Vazquez-Casielles and Diaz-Martin (2008:775), for any service provider to recover from negative incidents during the service encounter, service recovery strategies need to be implemented. These recovery strategies could move a consumer from a place of dissatisfaction to one of satisfaction and loyalty. As part of these recovery strategies, service providers need to consider how consumers perceive the level of justice they experience to recovery from the failure. Chebat and Slusarczyk (2005:664) add that consumers complain after experiencing a negative service encounter due to the injustice they perceive due to the low levels of service experienced.

Kuo and Wu (2011:128) indicate that perceived justice involves both an emotional and behavioural aspect and evolved from justice theory which is based in equity theory. According to Chebat and Slusarczyk (2005:665), perceived justice refers to "an evaluative judgment about the appropriateness of a person's treatment by others". From previous studies conducted on perceived justice in different settings (for example B2B, retail and services), various dimensions of perceived justice can be identified. McCollough, Berry and Yadav (2000:121-137) as well as Mattila and Patterson (2004:336-346) identified two dimensions namely, distributive and interactional. Other researchers have identified four dimensions namely distributive, interactional, procedural and informational (Colquitt 2001:386-400), while Sindhav et al. (2006:323-335) identified distributive, interactional, procedural and interpersonal dimensions.

Although different dimensions have been identified, the majority of studies identify three dimensions namely distributive, interactional and procedural interaction (DeWitt et al. 2008:269-281 ; Iyer & Muncy 2008:21 -32; Kim & Smith 2005:162-180; Maxham & Netemeyer 2003:46-62; McCole 2004:345-354; McColl-Kenedy & Sparks 2003:251-267; Schoefer & Diamantopoulos 2008:91-103; Schoefer & Ennew 2008:261-270; Voorhees & Brady 2005:192-204). As the majority of studies on the topic identified three dimensions (distributive, procedural and interactional), these dimensions are the focus of this study.

2.3 The underlying dimensions of perceived justice

According to Del Rio-Lanza et al. (2008:776), distributive justice refers to providing tangible elements (e.g. refunds, discounts) to consumers in order to compensate for service failures. Schoefer (2010:56) adds that distributive justice also includes the perceived outcome of the service failure and complaint. These authors state that high levels of negative emotions are experienced by consumers when they perceive the distributive justice as being low.

Chebat and Slusarczyk (2005:665) describe procedural justice as the ways in which the service provider deals with the service failure (e.g. timing, adaptability to consumer needs). Consumers see procedural justice as necessary as they expect service providers to bring about recovery from any service failure (Del Rio-Lanza et al. 2008:776). Kuo and Wu (2011:129) add that procedural justice includes whether consumers can express their opinions and the ease of being able to make a complaint about the service failure.

Interactional justice, as defined by Dayan, Hassan Al-Tamimi and Lo Eldadji (2008:322), refers to consumers' perceptions regarding the fairness of the treatment in the interaction between themselves and service provider employees (e.g. empathy, courtesy and effort to solve the problem).

From previous studies, Del Rio-Lanza et al. (2008:776) suggest that the importance of each dimension is related to the situation under investigation. Chebat and Slusarczyk (2005:670) suggest that interactional justice is predominant in the service environment. Pizzutti and Fernandes (2006:15) identified that from a satisfaction perspective, only interactional and distributive justice are important. Dayan et al. (2008:328) identified interactional and distributive justice as most important in terms of loyalty. Kuo and Wu (2011:134) identified that only distributive justice influenced post-purchase intentions. Furthermore, Chebat and Slusarczyk (2005:671) and Schoefer (2010:61) explain that the demographics of consumers (e.g. age, education, gender) influence the level of emotions experienced during a service failure, and therefore also their perceptions of the level of justice experienced during the recovery process.

3. PROBLEM INVESTIGATED AND RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The South African health care industry is characterised by poor service levels and consequently patients experience many negative service encounters in this industry (de Jager & du Plooy 2011:103). There is also a large disparity in service levels between the private and public health care sectors in South Africa with private health care ranked among the best in the world and public healthcare ranked among the worst in the world (Economic Intelligence Unit 2011:4; Pharmaceutical Executive 2006:8). According to Suki et al. (2011:42), this disparity in service levels in the private and public health care sectors requires more research.

It is furthermore evident from the literature that customers need to experience a sense of perceived justice following a negative service encounter in order to recover from the incident (Del Rio-Lanza et al. 2008:780). A number of dimensions of perceived justice have been identified previously, namely distributive, procedural and interactional justice, but the importance of these three dimensions is dependent on the situation and field where the study is conducted (Chebat & Slusarczyk 2005:665; Dayan et al. 2008:322; Del Rio-Lanza et al. 2008:776). The literature also indicates that consumer demographics could play a role in the importance of each justice dimension (e.g. Chebat & Slusarczyk 2005:671 ; Schoefer 2010:61).

Taking the abovementioned factors into consideration, the primary objective of this paper is to investigate the perceived justice patients experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector (in both the private and public health care sectors).

The following secondary objectives have been formulated for this study:

• Develop a demographic profile of respondents who experienced a negative experience in the South African health care sector and who took part in the study.

• Uncover the underlying dimensions of perceived justice as experienced by patients in the South African health care sector following a negative service encounter.

• Determine whether patients who experienced a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector differ significantly in their perceptions with regard to the underlying dimensions of perceived justice they experienced following the negative service encounter.

• Determine whether private and public health care patients differ significantly with regard to the perceived justice they experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector.

• Determine whether patients differ significantly, based upon demographic characteristics such as age, gender, highest level of education and employment status, with regard to the perceived justice they experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector.

The following alternative hypotheses are set for the study:

H1a: Patients who experienced a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector differ significantly with regard to their perceptions of the underlying dimensions of perceived justice.

H2a: Private and public health care patients differ significantly with regard to the perceived justice they experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector.

H3a: Patients differ significantly, based upon demographic characteristics such as age, gender, highest level of education and employment status, with regard to the perceived justice they experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector.

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

In order to achieve the objectives of this study, the researchers followed a descriptive research design that is quantitative in nature. The target population of the study included all individuals who have experienced a negative service encounter in the health care sector in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. A non-probability sampling technique in the form of convenience sampling was used to select respondents from the target population. The researchers made use of trained fieldworkers to (1) identify prospective respondents, (2) screen these respondents for eligibility, and (3) request them to complete the self-administered questionnaire. Upon completion respondents were required to return the questionnaire to the fieldworkers.

The self-administered questionnaire contained a number of sections including a preamble that explained the purpose of the research to the prospective respondent. The preamble also provided instructions to the prospective respondents on how to complete the questionnaire and included a screening question to ensure that only those who had experienced a negative service encounter in the South African health care industry took part in the study.

The first section of the questionnaire included 13 items measuring the construct 'perceived justice' in response to the negative service encounter experienced in the South African health care sector. Respondents were required to indicate their level of agreement with the 13 items on a Likert- type scale where 1 represents "totally disagree' and 7 represents 'totally agree'. The 13 items measuring perceived justice were adapted from previous studies including the works of DeWitt et al. (2008:269-281), Iyer and Muncy (2008:21-32), Kim and Smith (2005:162-180), Maxham and Netemeyer (2003:46-62), McCole (2004:345-354), McColl-Kenedy and Sparks (2003:251-267), Schoefer and Diamantopoulos (2008:91-103), Schoefer and Ennew (2008:261-270) and Voorhees and Brady (2005:192-204). The questionnaire also contained a section determining the demographic profile of respondents. A total of 289 usable questionnaires were retained for data analysis.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 20 was used for capturing, editing, cleaning and analysing the data. Frequencies were calculated to present a demographic profile of respondents. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to uncover the underlying dimensions of perceived justice. Since the results for each of the 13 items were normally distributed and the sample size is sufficiently large, parametric tests were used to test the hypotheses formulated for the study. Paired samples t-tests and independent sample t-tests were used to test the hypotheses of the study. The researchers relied on a significance level of 0.05 to indicate statistical significant differences between the means of groups.

Furthermore, for the purpose of hypotheses testing, the response categories for a number of demographic variables were collapsed to allow for comparison between the means of different groups for each of the underlying dimensions of perceived justice. The age variable was collapsed into two groups, namely those who are 49 years and younger and those who are 50 years and older. The variable measuring respondents' highest level of education was collapsed into those who have a matric or lower qualification and those who have a post -school qualification and finally, the variable measuring employment status was collapsed into those who have a full-time job and those who are not full-time employed.

5. RESULTS

This section provides insight into the demographic profile of respondents. It also presents the results of the EFA as well as the hypotheses formulated for the study.

5.1 Demographic profile of respondents

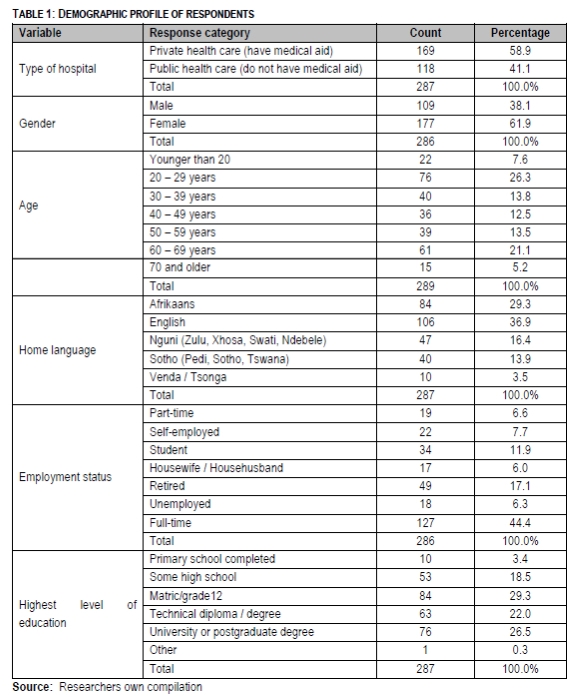

Table 1 presents a demographic profile of the 289 respondents who took part in the study. The totals in the count column vary due to missing values, but the percentage column reports the valid percentage or percentage excluding the missing values.

It is important to note that all respondents have experienced a negative service encounter at a hospital, but the results do not indicate the incidence of negative service encounters in the sector as a whole, neither in the private nor public spheres. From those experiencing the negative service encounter in the South African health care sector, 58.9% are private health care sector patients and the balance of 41.1% are public health care patients. It is furthermore evident from Table 1 that the majority of respondents who took part in the study are female 61.9%, between the ages of 20 and 29 years of age (26.3%), and are English speaking (36.9%). With regard to employment status, 44.4% are full-time employed and 29.3% indicated a matric as their highest level of education.

5.2 Perceived justice experienced following a negative service encounter

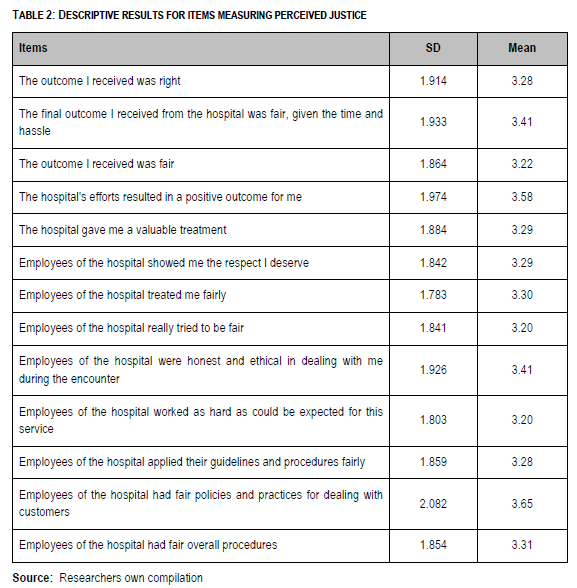

Table 2 provides an overview of the standard deviations and means realised for each of the items measuring perceived justice on a Likert- type scale where 1 represents 'totally disagree' and 7 represents 'totally agree'.

It is evident from Table 2 that most items are below the mid-point of the scale except 'Employees of the hospital had fair policies and practices for dealing with customers' (mean = 3.65) and 'The hospital's efforts resulted in a positive outcome for me' (mean = 3.58). The items respondents agreed with the least include 'Employees of the hospital really tried to be fair' (mean = 3.20) and 'Employees of the hospital worked as hard as could be expected for this service' (mean = 3.20).

In line with the second objective to uncover the underlying dimensions of perceived justice as experienced by patients in the South African health care sector following a negative service encounter, an EFA was conducted of the 13 items used to measure the perceived justice construct in this study.

The researchers first had to assess the suitability of the data for the execution of an EFA. Eiselen, Uys and Potgieter (2010:105) firstly suggest a sample size equal to ten times the number of respondents for each item included in the factor analysis as ideal. Since 13 items have been included in the factor analysis, a sample size of 130 or more respondents would have been ideal. The study, however, involved 287 respondents, which exceeds the suggested minimum number of respondents, making an EFA possible from this perspective. Secondly, the researchers calculated the Bartlett's test of sphericity p-value and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) value. The Bartlett's test of sphericity value indicates the extent to which all 13 items are correlated with one another, and the KMO value indicates whether sufficient correlations exist between pairs of items. The Bartlett's test of sphericity p-value should be equal or less than 0.05 and the KMO greater than 0.6 to continue with the factor analysis (Eiselen et al. 2010:107). A Bartlett's test of sphericity p-value of 0.000 was realised and a KMO value of 0.921 was realised. Based on these findings the researchers could proceed with the EFA.

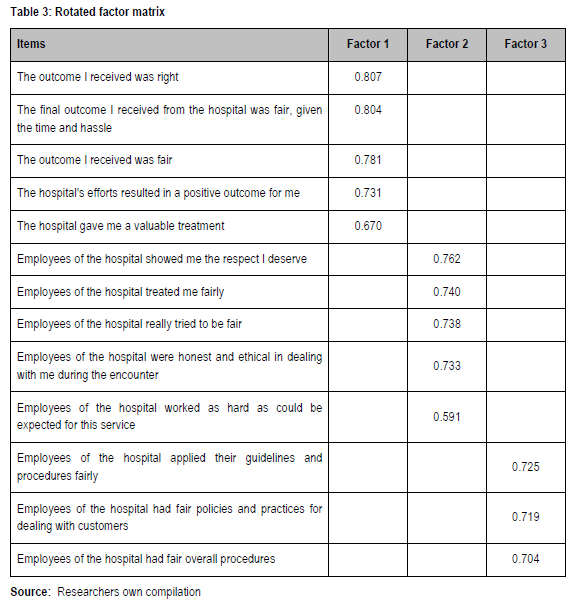

Since the items were measured on an unlabelled seven-point Likert- type scale, the resultant data is continuous in nature, allowing the researchers to use the Maximum Likelihood method to extract the underlying factors (Eiselen et al. 2010:105). The orthogonal rotation Varimax was furthermore used as method of rotation and an eigenvalue of 1 or more was used to determine the 'ideal' number of factors (Eiselen et al. 2010:108). The EFA uncovered three factors (dimensions) underlying the perceived justice construct. The three factors explain 78.996% of the variance. Table 3 provides an exposition of the results.

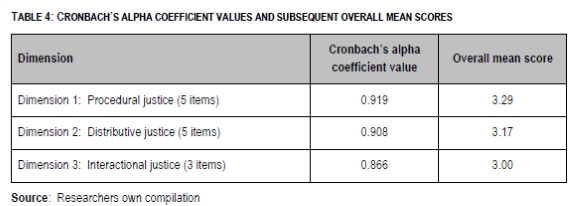

Based upon the rotated factor matrix presented in Table 3, the three underlying factors (dimensions) that were uncovered with the EFA were subsequently labelled in line with how these dimensions were labelled in previous studies. The researchers labelled the first dimension 'Procedural justice', the second dimension 'Distributive justice' and the third dimension 'Interactional justice'. It was furthermore necessary to determine the reliability or internal consistency of the scales measuring the items included in each of the three dimensions in order to ensure that all the items grouped as part of a factor indeed measure the 'underlying attribute' (Pallant 2010:95). A Cronbach's coefficient alpha value was calculated for each dimension for this purpose. According to Pallant (2010:95), a Cronbach's coefficient alpha value closer to 1 indicates greater reliability, while a cut-off value of 0.7 is suggested.

It is evident from Table 4 that all three dimensions can be considered reliable (internally consistent), allowing the researchers to calculate overall mean scores for the three dimensions for the purposes of hypothesis testing. The overall mean score for each dimension is furthermore reported and ranges between 3.00 and 3.29. The overall mean scores are all below the mid-point of the scale of 3.50, indicating low levels of agreement with items measuring perceived justice in the South African health care sector.

5.3 Hypothesis testing

This section presents the results for the three alternative hypotheses formulated for the study.

5.3.1 Hypothesis 1

With regard to H1a that patients who experienced a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector differ significantly with regard to their perceptions of the underlying dimensions of perceived justice, the following findings were made:

• The results of the paired-sample t-tests conducted to uncover significant differences between the pairs of underlying dimensions of perceived justice, uncovered significant differences between one pair of dimensions. Respondents feel they experienced procedural justice (mean = 3.29) statistically significantly more than interactional justice (mean = 3.00; p-value = 0.004) following a negative service encounter. As for the other pairs of dimensions, significant differences could not be uncovered.

Hypothesis 1a that patients who experienced a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector differ significantly in their perceptions with regard to the underlying dimensions of perceived justice can therefore be accepted in respect of the fact the they perceive they received significantly more procedural justice than interactional justice following the negative service encounter.

5.3.2 Hypothesis 2

With regard to H2a that private and public health care patients differ significantly with regard to the perceived justice they experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector, the following findings were made:

• The results of the independent sample t-tests conducted to uncover significant differences with regard to the perceived justice private and public health care patients experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector uncovered significant differences between respondents with regard to perceived distributive and procedural justice. Private health care patients (mean = 3.42) feel they received significantly more distributive justice than public health care patients (mean = 2.84; p-value = 0.003) following a negative service encounter. Private health care patients (mean = 3.46) also feel they received significantly more procedural justice than public health care patients (mean = 3.04; p-value = 0.042) following a negative service encounter.

Hypothesis 2a that private and public health care patients differ significantly with regard to the perceived justice they experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector can therefore only be accepted in respect of the fact that the private health care patients perceive they received significantly more distributive and procedural justice than public health care patients following the negative service encounter.

5.3.3 Hypothesis 3

With regard to H3a that patients differ significantly, based upon demographic characteristics such as age, gender, highest level of education and employment status, with regard to the perceived justice they experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector, the following findings were made:

• The independent sample t-test conducted to uncover a significant difference with regard to the perceived justice patients experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector based upon age, did not uncover any significant differences between those who are 49 years and younger and those who are 50 years and older.

• The independent sample t-test conducted to uncover a significant difference with regard to the perceived justice patients experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector based upon gender, did not uncover any significant differences between males and females.

• The independent sample t-test conducted to uncover a significant difference with regard to the perceived justice patients experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector based upon highest level of education, did not uncover any significant differences between those who have a matric or lower qualification and those who have a post- school qualification.

• The independent sample t-test conducted to uncover a significant difference with regard to the perceived justice patients experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector based upon employment status, did not uncover any significant differences between those who are full-time employed and those who are not.

Hypothesis 3a that patients differ significantly, based upon demographic characteristics such as age, gender, highest level of education and employment status, with regard to the perceived justice they experience following a negative service encounter in the South African health care sector can therefore be rejected.

6. CONCLUSIONS, IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

It is evident from the literature review that the health care industry in South Africa is characterised by high levels of service failures within its private and public health care sectors (Suki et al. 2011:42). This is echoed by the low levels of agreement with items measuring perceived justice following a negative service encounter in this study with only two items obtaining a mean above the mid-point of the scale.

The study also uncovered and labelled three underlying dimensions of perceived justice in South African health care that are in line with the dimensions of perceived justice that need to be taken into consideration during the service recovery process, namely distributive, procedural and interactional justice, according to Schoefer (2010:52-66).

The empirical results of the study also indicate that respondents who experienced a negative service encounter in the South African health care industry differ significantly in their perceptions of the dimensions of perceived justice following a negative service encounter. Respondents feel that they experienced significantly more procedural justice than interactional justice following a negative service encounter in the South African health care industry. This finding is, however, contradictory to most other research studies which found that interactional justice is predominant Chebat & Slusarczyk 2005:670; Dayan et al. 2008:328; Del Rio-Lanza et al. 2008:777, 779; Pizzutti & Fernandes, 2006:18). The finding furthermore supports those of Del Rio-Lanza et al. (2008:776) that each underlying dimension has varying levels of importance based on the situation under investigation. For the private and public health care sectors in South Africa, the finding implies that health care providers need to ensure that they respond quickly to service failures and ensure that they adapt to the situation and meet consumer needs when implementing the service recovery strategy. Additionally, this suggests that health care providers should treat customers more fairly and show empathy once a service failure occurs. As interactional justice was experienced at a lower level, employees of health care providers should ensure that policies are followed and fairly implemented.

Pertaining to the level of dimensions of perceived justice experienced by the private and public health care sector respondents, the study found private health care respondents experienced higher levels of distributive and procedural justice than public health care respondents. This finding is in line with literature that public health care sector service failure and recovery levels are lower than those of private health care (de Jager & du Plooy 2011:103). This implies that the public health care sector needs to pay more attention to their service recovery strategies. Specifically, the public health care sector needs to ensure that they increase the levels of compensation provided to patients as well as improve the timing of the service within their recovery strategies. For example, within service recovery strategies, public health care providers need to specify a time period within which service failures need to be rectified or within which complaints will be handled. Furthermore, public health care sectors need to provide an opportunity for patients to complain. This can be done through suggestion boxes at public health care facilities or having a department within the facility dealing with complaints.

The study found that no significant differences could be observed pertaining to the demographic profile (specifically age, gender, employment and educational level) of respondents and the perceived justice experienced. This is contradictory to studies by Schoefer (2010:61) and Chebat and Slusarczyk (2005:671). The findings of the study implies therefore that private and public health care sectors can develop generic recovery strategies as consumer demographics will not influence the way in which respondents perceive the justice experienced during the recovery process.

7. LIMITATIONS OF THE RESEARCH AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

This study is limited as the results cannot be generalised to the population since a non-probability convenience sampling method was used and was only conducted in one province in South Africa. The study could be expanded by researching the differences in consumers from other geographical areas pertaining to service failures and the three dimensions of justice. As negative emotions are experienced during a service failure, linking the results of this study with the negative emotions consumers experience could be beneficial and expand the understanding of the concepts. This would aid service providers in developing specific service recovery strategies. Additionally, conducting this research from a managements (health care provider) perspective would add value to the services marketing field.

REFERENCES

CHEBAT J. & SLUSARCZYK W. 2005. How emotions mediate the effects of perceived justice on loyalty in service recovery situations: an empirical study. Journal of Business Research 58(2005):664-673. [ Links ]

COLQUITT AJ. 2001. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology 86(3):386-400. [ Links ]

DAYAN M, HASSAN AL-TAMIMI HA & LO ELHADJI A. 2008. Perceived justice and customer loyalty in the retail banking sector in the UAE. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 12(4):320-330. [ Links ]

DE JAGER J & DU PLOOY T. 2011. Are public hospitals responding to tangible and reliable service-related needs of patients in the new South Africa? Journal of Management Policy and Practice 12(2):103-119. [ Links ]

DEL RIO-LANZA AB, VAZQUEZ-CASIELLES R & DIAZ-MARTIN AM. 2008. Satisfaction with service recovery: Perceived justice and emotional responses. Journal of Business Research 62(2009):775-781. [ Links ]

DEWITT T, NGUYEN DT & MARSHALL R. 2008. Exploring customer loyalty following service recovery: The mediating effects of trust and emotions. Journal of Service Research 10(3):269-281. [ Links ]

ECONOMIC INTELLIGENCE UNIT. 2011. Health care report South Africa. Economic Intelligence Unit Industry Report: Health Care September 2011. [ Links ]

EISELEN R, UYS T & POTGIETER T. 2010. Analysing survey data using SPSS13. 4th ed. Johannesburg: STATKON, University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

FINWEEK. 2007. Expensive but world class. Finweek 15 February:63-64. [ Links ]

IYER R & MUNCY JA. 2008. Service recovery in marketing education: It's what we do that counts. Journal of Marketing Education 30(1):21-32. [ Links ]

KIM YK & SMITH AK. 2005. Crime and punishment: Examining customers' responses to service organizations' penalties. Journal of Service Research 8(2):162-180. [ Links ]

KUO Y & WU C. 2011. Satisfaction and post-purchase intentions with service recovery of online shopping websites: Perspectives on perceived justice and emotions. International Journal of Information Management 32(2012):127-138. [ Links ]

MATTILA AS & PATTERSON PG. 2004. Service recovery and fairness perceptions in collectivist and individualist contexts. Journal of Service Research 6(4):336-346. [ Links ]

MAXHAM JG III & NETEMEYER RG. 2003. Firms reap what they sow: The effects of shared values and perceived organizational justice on customers' evaluations of complaint handling. Journal of Marketing 67(1):46-62. [ Links ]

MCCOLE P. 2004. Dealing with complaints in services. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 16(6):345-354. [ Links ]

MCCOLL-KENNEDY JR & SPARKS BA. 2003. Application of fairness theory to service failures and service recovery. Journal of Service Research 5(3):251-267. [ Links ]

MCCOLLOUGH MA, BERRY LL & YADAV MS. 2000. An empirical investigation of customer satisfaction after service failure and recovery. Journal of Service Research 3(2): 121-137. [ Links ]

PALLANT J. 2010. SPSS survival manual: a step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PERROTT BE. 2011. Health service delivery in Australia: gaps and solutions. Journal of General Management 36(6):53-66. [ Links ]

PHARMACEUTICAL EXECUTIVE. 2006. Cheaper health care insurance could trigger ethical market boom. Focus reports: South African report. March Supplement (2006):8-10. [ Links ]

PILIGRIMIENÉ Z & BUČIŪNIENÉ I. 2011. Exploring managerial and professional view to health care service quality. Economics and Management 2011 (16):1304-1315. [ Links ]

PIZZUTTI C & FERNANDES D. 2006. The moderating impact of the type of relationship on the consumers' service recovery evaluations and their consequences. Latin American Advances in Consumer Research 1(2006):15-20. [ Links ]

SCHOEFER K. 2010. Cultural moderation in the formation of recovery satisfaction judgments: A cognitive-affective perspective. Journal of Service Research 13(1):52-66. [ Links ]

SCHOEFER K & DIAMANTOPOULOS A. 2008. The role of emotions in translating perceptions of (in)justice into postcomplaint behavioral responses. Journal of Service Research 11(1): 91-103. [ Links ]

SCHOEFER K & ENNEW C. 2008. The impact of perceived justice on consumers' emotional responses to service complaint experiences. Journal of Services Marketing 19(5):261-270. [ Links ]

SINDHAV B, HOLLAND J, RODIE AR, ADDIDAM PT & POL LG. 2006. The impact of perceived fairness on satisfaction: Are airport security measures fair? Does it matter? Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice 14(4):323-335. [ Links ]

SUKI NM (NORAZAH MOHD), LIAN JC & SUKI NM (NORBAYAH MOHD). 2011. Do patients' perceptions exceed their expectations in private health care settings? International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance 24(1):42-56. [ Links ]

VOORHEES CM & BRADY MK. 2005. A service perspective on the drivers of complaint intentions. Journal of Service Research 8(2):192-204. [ Links ]

YAACOB MA, ZAKARIA Z, SALAMAT ASA, SALMI NA, HASAN NF, RAZAK R & RAHIM SNA. 2011. Patients' satisfaction towards service quality in public hospital: Malaysia perspective. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business 2(2):635-640. [ Links ]