Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of Contemporary Management

versión On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.10 no.1 Meyerton 2013

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Re-positioning Namibia as a cultural tourism destination to enhance its competitiveness: a tour operators' perspective

J NdlovuI; E NyakunuII

IUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal

IIPolytechnic of Namibia

ABSTRACT

Namibia is rich in mineral wealth, tourism and wildlife. Over the past years, the destination has been promoted for its wildlife, abundance of scenery and endless horizons. Nevertheless, cultural tourism has been viewed as an alternative to the main stream tourism. Studies have shown that cultural tourism has become an important product and in some cases a dominant factor in the rural economies of African destinations. The paper presents and discusses key findings derived from the study. The empirical evidence shows that the use of culture as a tourism product can complement the plethora of wildlife products currently on offer in Namibia. Results further show that most tour operators are reluctant to promote Namibia as a cultural tourism destination. The majority of tourists who visit the rural areas do so by coincidence since the rural areas are located en-route to the National Parks. Even though Namibia experiences a significant growth in tourist arrivals, less attention is currently being paid to the development of alternative forms of tourism, particularly cultural tourism, despite the growing interest of international visitors. This paper urges tour operators to create demand for cultural tourism as an alternative form of tourism.

Key phrases: attractiveness, cultural tourism, destination competitiveness, re-positioning, tour operators

1 INTRODUCTION

Tourism is the third largest contributor of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to Namibia's economy after mining and fisheries/agriculture and it is one of the largest job provider industries (MET 2009:3). In many countries, tourism has become the largest economic sector and contributes substantially towards their national economies. In Namibia, tourism is viewed as a catalyst for development, contributing to national and regional harmony (MET 2009:3; NACSO 2010:8). The country is largely rural with a diverse tangible and intangible cultural wealth. A number of major cities namely; Windhoek, Swakopmund and Walvis Bay offer fascinating tourism opportunities. Besides in-migration to the country, it is apparent that more visitors have discovered Namibia as reflected in the increase of tourist arrivals, from 777,890 (in 2005) to 984,099 (in 2010). Revenues are expected to increase from US$2.4 billion (in 2002/3) to US$11.5 billion (in 2009) and it accounts for about 81 000 jobs countrywide and this trend is likely to be sustained in the future (MET 2010:2; NTB 2011 : Internet).

Despite these modest numbers, Namibia has the potential to become one of Africa's leading tourism economies over the next decade (MTI 2008). The tourism industry in Namibia is spread throughout various regions and communities. Besides the warm climate, scenery, and national parks, there is an abundance of attractions and various types of outdoor recreational activities. Natural resource areas such as forests, rivers, and wetlands are increasingly becoming popular destinations even for "business tourists" who add such sites as side trips for vacations that primarily focus on the beach, a theme park or an urban area.

Based on its natural and cultural resources, Namibia is in a unique position to further develop and promote its tourism industry. However, lack of data pertaining to cultural tourism visitor numbers, associated demographic profiles, and behavioural issues limit the ability to conduct strategic marketing programmes in order to increase visitation to the country. Whilst the efforts of the Namibia Tourism Board (NTB) in promoting and marketing tourism in general are laudable, it should nonetheless be pointed out that the country's inability to recognize the changing demand and consumption patterns of tourists has resulted in promotion and marketing strategies focusing mainly on wildlife and adventure tourism (Ipara 2001:102). However, during the past decade there has been a resurgence of interest in indigenous cultures which has added an impetus to the tourism industry in Namibia.

2 THEORY

Cultural tourism has been defined as the art of participating in another culture, of relating to people and places which demonstrate a strong sense of their own identity (Wood 1993:11). It encompasses built patrimony, living lifestyles, ancient artefacts and modern art and culture (Timothy 2011:49). It is motivated by a desire to observe, learn about, or participate in the culture of the destination (Timothy 2011:16), experiencing cultural traditions, alluring places and local values (Richards 2001a:36). Culture can be viewed in two inter-related perspectives: the psychological perspective - what people think (i.e., attitudes, beliefs, ideas and values), and what people do (i.e., ways of life, artworks, artefacts and cultural products) (Akama 2001:13). Therefore, cultural tourism can be seen as covering both 'heritage tourism' (related to artefacts of the past) and 'art tourism' (related to contemporary cultural products) (McKercher & du Cross 2002:31; Richards 2001b: 272) which has added a new dimension to tourism demand. Tourism demand is about using tourism as a form of consumption to achieve a level of satisfaction for individuals, and involves understanding their behavior and actions and what shapes these human characteristics (Goeldner & Ritchie 2009:206). Cultural tourism demand has been defined in numerous ways, including the total number of persons who travel, or wish to travel, to use tourist facilities and services at places away from their usual place of work and residence (Reisinger, Cravens & Tell 2003:430). To this effect cultural tourism demand can assist in understanding motivation, needs and experiences as well as being a useful indicator of changing trends (Page & Connell 2006:63). More so, tourism demand is the foundation on which all tourism related business decisions ultimately rest (Witt & Song 2001:112).

3 MOTIVATION FOR CULTURAL TOURISM

Tourism demand is a comprehensive outline of what motivates tourists to travel, where they travel to, and how often they travel (Lubbe 2003:109). Thus, a consideration of demand in relation to tourism can assist managers and destination marketers in understanding tourists' motivation, choices, needs, preferences and experiences (Slabbert & Viviers 2012:68), as well as being a useful indicator of changing trends (Page & Connell 2006:63). Hall and Page (1999:321) agree that an understanding of tourism demand is a starting point for the analysis of why tourism develops, who patronizes specific destinations and what appeals to different tourism generating regions. Travel motivation happens when the individual decides that a travel experience will satisfy a specific need or needs (Lubbe 2003:109). It is also at this point that the individual becomes a potential tourist and he or she begins to evaluate various destinations for holiday opportunities to quench this quest.

4 COMPETITIVENESS AS A TOOL TO REPOSITION A DESTINATION

Competitiveness is a key word for any destination manager/marketer. There is little written about the competitiveness of tourism destinations (Buhalis n.d: Internet). The concept of destination competitiveness is relative and multi-dimensional in that it should be consistent with international economics and business literature (Dwyer, Forsyth & Rao 2002:4). Subjective variables such as culture, heritage and quality of life top the list in any destination competitiveness frameworks (Dwyer et al. 2002:5; Heath 2002:124; Ritchie & Crouch 2003:258).

Competitiveness is linked to perceived quality of attractions that are better than those of other destinations (McKercher & du Cross 2002:208). Such perceptions concern, in particular, those aspects of the tourism experience that are professed by travelers to be of superior value considering the place's characteristics (Avraham & Ketter 2008:193). To achieve a competitive advantage, a destination should ensure that its overall appeal and the tourist experience offered are superior to that of competitors and cannot be easily imitated.

This can be achieved through effective positioning which identifies strong attributes that are perceived as important by visitors (Ibrahim & Gill 2005: Internet). However, once a destination attains a competitive advantage, it becomes subject to erosion by the actions of a competitor who can either imitate or introduce further innovation (Dwyer et al., 2002:6). For competitive advantage to be sustainable over time there should be barriers to imitation, also called isolating mechanisms, such as the use of copyrights, the complexity of product offering or the overall experience within a destination of which culture is a unique example (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Resource-based_view:Citing_Wikipedia). If the isolating mechanisms are strong, the competitive advantage survives for longer.

A destination could imitate the strategies of another destination, usually a competitor, in order to erode the other destination's competitive advantage. According to Grant (1991:115), certain conditions have to exist for imitation to take place. The imitating destination should identify with that which the rival possesses as a competitive advantage. Having identified that the competitor has a competitive advantage as evidenced by its above-average profitability, the imitating destination should believe that it could achieve a similar advantage by investing in innovation.

5 REPOSITION A DESTINATION THROUGH CULTURAL TOURISM

Tourism destinations worldwide are faced with the challenge of repositioning themselves through image alteration or reclassification of the tourism product in their current positioning strategy (Tkaczynski, Hastings & Beaumont 2006: Internet). Research or the informed acquisition of strategic knowledge and information is an increasingly important activity pursued by government tourism organisations (Weaver & Lawton 2006:400).

Studies conducted by Dugulan, Balaure, Popescu and Veghes (2010:744) have shown that cultural heritage does not appear as a supporting pillar for travel and tourism competitiveness in many countries particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. This is not necessarily due to lack of such resources but rather due to insufficient or ineffective promotion.

Determining cultural tourists' visitation trends, identification of key market segments and their expenditure, activity patterns, perceptions of visitor satisfaction and effectiveness of prior and current promotional campaigns should be based on market research. To understand tourists' motivation and behaviour, destination marketers should analyse the elements that influence visitation in order to achieve visitation goals (Pearce 2005:162; Enright & Newton 2005:341), hence this can help in repositioning a destination for competitiveness (Cooper, Fletcher, Fyall, Gilbert & Wanhill 2005:5).

Understanding the tourist pre-purchase information search can help in the design of effective marketing strategies getting across the right message, in the right place and at the right time to the tourists (Lubbe 2003:37). This implies using a certain criteria for identifying cultural tourists' behavioural characteristics, expenditure patterns and needs which is fundamental in market segmentation.

6 MATERIALS AND METHODS

While the perspectives of the international visitors and particularly those of tourists from the developed countries have been the 'benchmark' for assessing a destination's appeal, in most developing countries, domestic tourists' perspectives can be argued to be an inclusive perspective, noting that support of the local industry by the locals can realize improved quality in products and services, maintenance of occupancy levels and ultimately the confidence of international visitors (Ndivo, Waudo & Waswa 2012:2).

This study sought to determine tour operators' perspectives regarding cultural tourism in Namibia. The study measured issues such as the major products being marketed, local community awareness of the significance of cultural tourism, the state of cultural resources and the overall growth of cultural tourism. From the list mentioned above, a questionnaire was prepared comprising both open-ended and closed questions. On open ended questions, respondents were asked to add some important cultural elements worth preserving which were omitted on the Likert list but helped in discussing the subject. Closed questions were in the form of a Likert scale (1= strongly disagree and 5= strongly agree) where respondents were asked to rate the statement regarding cultural tourism products.

The survey consisted of a total number of 500 e-mail questionnaire attachments sent to tourism and travel operators drawn from the list of tourism business directory in Namibia. Participants were randomly selected. A 22% return rate was achieved which was deemed satisfactory considering the data collection method used. The constraint that the survey encountered was that respondents were reminded three times. In the first instance, 12% responses were received, on the second time, 6% and finally, 4% were received. Since the aim of the study was to symphony the views of respondents regarding re-positioning Namibia as a cultural tourism destination in order to enhance its competitiveness, simple tabulations were made showing the views of respondents.

The method was deemed suitable as it enables the description of data. The decision to use cultural heritage as a key component was reached based on the destination's unique untapped cultural and heritage resources. A survey of ten major tour operators' website was conducted. The snap survey sought to review the products, representation of culture through graphics and images being promoted by tour operators. The results were then used to make inferences regarding cultural tourism in Namibia and its implications to destination marketing.

7 RESULTS

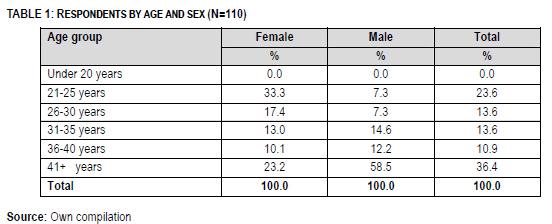

Based on the empirical survey, the following results are presented. Table 1 summarises the demographic description of the respondents. The respondents were categorised according to age and sex. The table seeks to understand the largest percentage of respondents based on the aforementioned variables.

Table 1 shows the distribution of respondents by age and sex and it can be observed that about 36% of the total respondents were aged 41 years and above of which 58.5% were males. A total of 23.6% of the respondents were aged 21-25 years of which 33.3% were females. The results show that the majority of people working as tour consultants were females and young and those who were 41 years and above were probably in management positions as shown in Table 2 below.

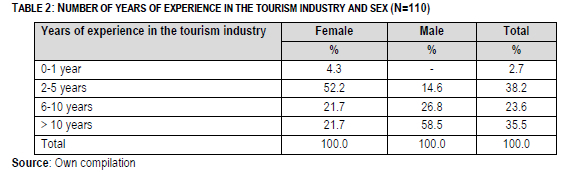

The survey shows that 38.2% of the respondents had 2-5 years of experience followed by 35.5% who had 10 years and above. A total of 23.6% had 6-10 years of experience. The results show that there was a balance on the responses since most of the respondents had more than 2 years working experience.

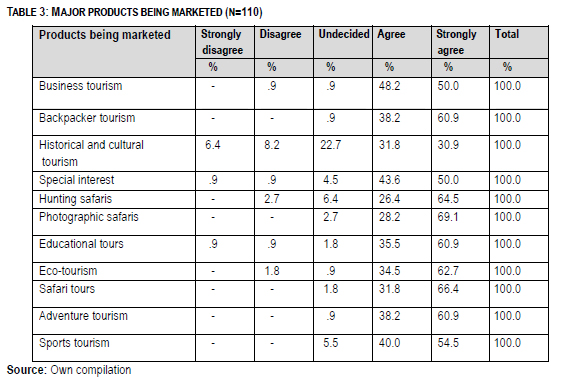

In order to reposition Namibia as a cultural tourism destination, respondents were asked to identify the most important products being marketed. The responses were tabulated as indicated in Table 3.

The table above shows that tour operators tend to promote the following products namely; photographic safaris (69.1%), safari tours (66%), hunting safaris (64.5%), eco-tourism (62.7%), educational tours (60.9%), adventure tourism (60.9%), and sports (54.5%). Some of the products being promoted include special interest (50%), business tourism (50%) and historical and cultural tourism (30.9%). The results show that cultural tourism is not marketed as a unique product but as part of a product line (package). Whilst Namibia has vast cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible heritage, the results show that there are no tour operators specialising in this niche product.

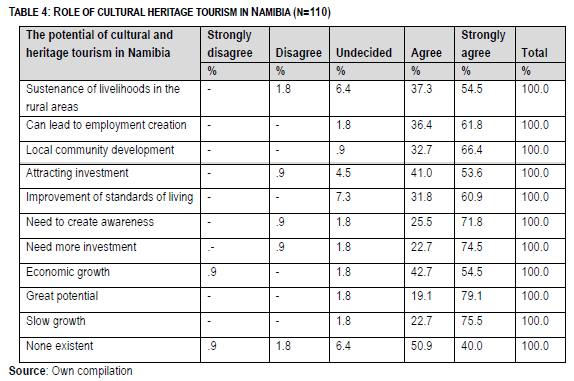

To determine the potential role of cultural tourism in the Namibian economy, respondents were asked to rate a set of statements concerning the potential of cultural heritage tourism in Namibia. The responses obtained are indicated in Table 4.

The results indicate that Namibia has great potential (79.1%) for cultural tourism, 75.5% of the respondents felt that cultural tourism has a slow growth which is supported by 74.5% who said cultural tourism needs more investment. Since there is evidence that this product needs more investment, there is need to create awareness (71.8%) on the significance of cultural tourism. If cultural tourism is promoted, it can lead to local community development (66.4%), employment creation (61.8%), improved standards of living (60.9%) and sustenance of livelihoods (54.5%).

Generally, the world over tourism can lead to economic growth (54.5%). Respondents were of the opinion that since more investment is needed; stakeholders need to develop ways of attracting investment (53.6%) into this area. Only 40% of the respondents felt that cultural tourism was none existent. To ensure viability of this product, respondents were of the opinion that there is need to develop interpretation services or tell compelling stories of the past and document these in order to attract cultural tourists.

However, in some cases, the evidence shows that cultural tourism was viewed as providing real and authentic life experiences to tourists in communal areas. Furthermore, some respondents felt that, if it is properly planned it can yield more benefits to the locals through the sale of hand-made crafts from local materials as souvenirs.

8 TOUR OPERATOR'S PERCEPTIONS OF CULTURAL TOURISM

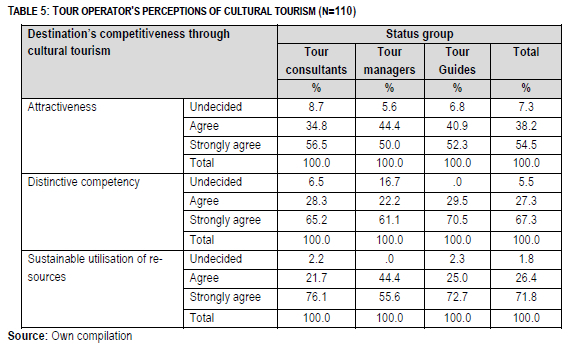

Some tour operators commented that they were not sure of any incidences that have transpired as an outcome of cultural tourism impact; however some positive outcomes were noted where tourists visit cultural heritage sites in Namibia, make documentaries of tribal lives and take pictures of cultural artefacts. Some tour operators were not sure as to what measures of control are there and some were not even aware of the cultural heritage policy. Table 5 shows the perceptions of tour operators regarding cultural tourism.

Tour operators strongly agreed that cultural tourism can increase the attractiveness of Namibia as a destination (54%). A total of 67.3% strongly agreed that this product can be used as a distinct competitive advantage. Tour operators acknowledged that cultural tourism can result in sustainable utilisation of resources (71.8%), since it can help people to develop a sense of pride in their culture. Tour operators were of the opinion that culture is viewed by some locals as being backwards, especially the youth. However, some tour operators were concerned that the growth of cultural tourism can result in tourists mythologising local cultures, which can eventually cause deterioration on the quality of experience through commodification of culture. Tour operators were also concerned about mass cultural tourism which has a potential to impact negatively on the destination should this product be promoted robustly. Some tour operators warned that even though cultural tourism has the potential to yield positive benefits, it needs to be managed properly so that positive impacts could be realised.

A substantial percentage of the respondents (35%) agreed to a certain extent that local communities are involved in cultural tourism planning in their area since planning is a broad process which starts from national to local levels (30% of the respondents agreed and 20% greatly agreed). The results show that more consultations and involvement of locals is needed for cultural tourism to succeed. It seems as if cultural tourism developers only consult with government on key issues and that locals participate passively at grassroots level.

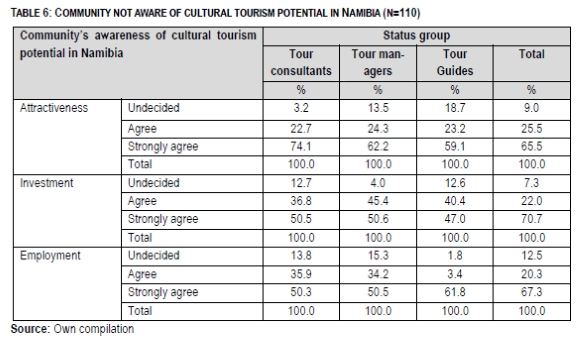

To support the evidence presented above, respondents indicated that locals do not play a pivotal role in the cultural tourism implementation (40%) process. Tour operators suggested that if local people are being used as attractions, national cultural tourism strategies should be put in place to create community's awareness of tourism potential in Namibia. The involvement of local people in marketing and promotion of cultural products could improve the product offering as, indicated in Table 6.

The evidence suggests that most communities are not aware of the value of cultural tourism in Namibia. Whilst tourists come from all over the world to visit Namibia, the community is ignorant of the contribution of culture to destination attractiveness (65.5%). Even though tour operators were of the opinion that some community projects are well managed and the community is largely involved, some communities were not aware of the amount of investment in cultural tourism (70.7%) in their locales. This being the case, tour operators suggest that communities should be more involved in all projects in their areas, especially if the project has the potential to help the community directly. However, some community members raised concerns about foreign life style influences, sympathy and the feeling of pity by visitors in their communities. Respondents could not link employment (67.3%) to cultural tourism; concerns were raised with regard to the loss of authentic tradition which has been compounded by the introduction of a living museum concept. Generally, respondents indicated that there is a significant upkeep of cultural heritage sites in Namibia. Furthermore, respondents indicated that the Living Museums are part of Namibia Community-Based Tourism Association (NACOBTA) strategies to revive cultural tourism but most of the cultural tourism activities are not controlled at all or if controlled, it is not enough.

9 DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Cultural tourism is premised on local people's rich and diverse material and non-material resources. The results show that in Namibia, cultures have been negated or poorly developed, promoted and marketed to meet the diverse and changing consumption tastes and patterns of cultural tourists. As a result, few communities appreciate the anticipated benefits of cultural tourism projects which may not be immediate and sometimes take a long time before the results can start showing (Richards 2007:72). Contrary to the concerns raised by tour operators that cultural tourism could result in loss of authentic tradition, instead cultural tourism can be used as a community modifier. By documenting community lifestyles and rich traditions, local people/communities can begin to have a sense of belonging concerning their renewed source of community pride and overcome their prejudices. Cultural tourism should be compatible with tour operators' schedules and should offer reliable, regular show times and a guaranteed experience. Sometimes overseas tour operators reinforce existing stereotypes and inaccurate images of indigenous African communities (Akama 2001:14) through brochures, graphics and other promotional materials; in that case dissatisfaction can result if there is a gap between tourists' perception and their expectation. The bigger the gap, the more dissatisfied the tourists become. Even though tour operators in Namibia follow designated tourism routes, the evidence shows that there are no tour operators specialising in cultural tourism as a core product. To most, cultural tourism is an additional activity on their traditional routes which are not expanding benefits to communities. The fundamental principle of cultural tourism is that local people must retain ownership of their culture and have power in decision making with regards to the elements they wish to portray and with which they want to conceal (Richards 2007:73), which is not the case in Namibia.

Black alienation and exclusion from the main stream tourism in the past has meant that most blacks have lacked control over the way in which their diverse cultures have been portrayed (Akama 2001:15). Based on this notion, the cultural tourism strategy in Namibia should be questioned since the benefits are based on showcasing indigenous/marginalised communities as part of the cultural tourism strategy, which is different from the developed world. Currently, most Namibian nationals do not participate in cultural tourism, which has become a challenge in shaping this niche tourism activity.

Studies have shown that there is a struggle that has emerged between market viability, authenticity and representation which have resulted in commercial screening and packaging utility (Ramchander 2004:4). In pursuant of cultural heritage resources, these studies have shown that culture and history represent the primary touristic attractiveness of a destination which is the product of 'human' rather than 'natural' processes (Crouch, 2007:2). The evidence gained from the empirical findings suggests that what is being marketed and promoted are pseudo-events that are reflective of neither past nor present realities (Ramchander 2004:4).

Commercialisation of non-material forms of culture has been a major concern and the marketing of culture appears to be the most prevalent issue in developing countries (Richards 2007:75). Considering that the Namibian government has adopted tourism as a strategy for economic growth, poverty alleviation and employment creation, cultural tourism must not be used as a development option alone to base a rural economy on but should be used as a means to complement local economies that are already thriving (Sillignakis 2008).

The recognition of the role of cultural tourism in creating and reinforcing people's identity has, in recent years, played a significant role in the growing interest in diverse aspects of tourism, especially in the developed world. However, in Namibia, cultural tourism should lead to increased public appreciation of environmental issues and problems thereof by deriving strategies that recognise threats and focus on managing potential impacts in an attempt to strive for long-term viability (Page & Connell 2006:185). To be able to reposition a destination for cultural tourism prospects, it is essential to conduct basic market research about the status quo of cultural tourism, the activities undertaken by tourists during excursions and the overall perception of communities regarding cultural tourism. This will then inform destination markers on how they can re-position Namibia as destination competitively. The adoption of a "low volume-high returns model" demonstrates the need to target cultural tourists who are considered to be well informed, educated about cultural values and appreciate both social and economic impacts of their presence on the locale.

Global studies on cultural tourism indicate that many destinations are now actively emerging by developing their tangible and intangible cultural assets as a means of improving their comparative and competitive advantages on the marketplace. Beside, most destinations have created locale distinctiveness in the face of globalization. Nevertheless, tourism and culture have been viewed as major drivers of a destination's attractiveness which is a key component of competitiveness. To achieve competitiveness through cultural tourism, the government of Namibia has to initiate policy interventions to guide the adoption of cultural tourism as a distinct competitive advantage for the destination.

10 CONCLUSION

Tourism and culture have become buzz-words in today's destination competitiveness literature linked to their role in destination's attractiveness. The study has shown that the promotion of culture in all its forms is likely to feature strongly in tourism products and the promotion of emerging destinations such as Namibia, even those that have conventionally depended on their natural assets (sand, sun and sea) in the past for their attractiveness. Although cultural tourism has been studied in detail, this paper has revealed that most studies have failed to address the concept of destination attractiveness through culture and its use thereof for competitive positioning, especially in the African context.

This study revealed that Namibia has diverse cultural heritage resources, but most tourists who visit the destination are not culture enthusiasts and currently, cultural tourism is used as an additional activity by tour operators. As such, there is a need to develop tangible and intangible cultural assets creatively (e.g. selling "atmosphere", cultural events and or gastronomy, museums and monuments). The study argues that cultural tourism needs to be re-defined, re-packaged and marketed vigorously in order to lure a unique cultural tourism market segment.

The current assumption by those with the responsibility of marketing tourism in Namibia is that all tourists are interested in culture, which may not be the case. The key findings reveal that there is inadequate market research on cultural tourism and cultural tourism in its self is a "missed opportunity".

By conducting deliberate and comprehensive market research to understand tourists' needs, perceptions and motivation for visiting Namibia as a destination, particularly cultural heritage sites, Namibia can reposition itself for market leadership. Such studies should be extended to understanding local communities' needs, believes, attitudes, behaviour and expectations of cultural tourism. This paper recommends a holistic approach to cultural tourism awareness campaigns which should include tour operators and other tourism stakeholders. Finally, Destination Marketing Organisations (DMOs) should play a leading role in promoting cultural tourism to enhance Namibia's competitiveness.

References

AKAMA J. 2001. Introduction: cultural tourism in Africa in Western Kenya. In Akama & Sterry. 2001. Cultural tourism in Africa: strategies for the new millennium. Proceedings of the ATLAS Africa International Conference. Mombasa, Kenya [ Links ]

AVRAHAM E & KETTER E. 2008. Media strategies for marketing places in crisis: Improving the image of cities, countries and tourism destinations. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, [ Links ].

BUHALIS D. n.d. Marketing the competitive destination of the future Tourism Management. [Internet: http://www.wmin.ac.uk/Env/UDP/staff/buhalis.htm. Downloaded on 2013-01-28] [ Links ]

COOPER C, FLETCHER J, FYALL A, GILBERT, D, & WANHILL S. 2005. Tourism: principles and practices. 3rd ed. Oxford: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

CROUCH G I. 2007. Modeling destination competitiveness: A survey and analysis of the impact of competitiveness attributes. Gold Coast, Queensland: CRC for Sustainable Tourism. [Internet:http://www.sustainabletourismonline.com/awms/Upload/Resource/bookshop/Crouch_modelDestnComp-web.pdf Downloaded on 2013-01-28] [ Links ]

DUGULAN D, BALAURE V, POPESCU CI & VEGHES C. 2010. Cultural heritage, natural resources and competitiveness of the travel and tourism industry in Central and Eastern European Countries. Annales Universitatis Apulensis Series. Oeconomica 12(2):742-748. [ Links ]

DWYER L, FORSYTH P & RAO P. 2002. Destination price competitiveness: exchange rate changes vs inflation rates. Tourism Analysis 5(1): 1-12. [ Links ]

ENRIGHT JM & NEWTON J. 2005. Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in Asia Pacific. Comprehensiveness and Universality. Journal of Travel Research 43:339-350 [ Links ]

GOELDNER CR & RITCHIE JR. 2009. Tourism: principles, practices, philosophies. 12th ed. New Jersey: Wiley. [ Links ]

GRANT RM. 1991. The Resource-based theory of competitive advantage: implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review 33(3):114-135. [ Links ]

HALL CM & PAGE S. 1999. The Geography of tourism and recreation: environment, place and space. London: Rutledge. [ Links ]

HEATH E. 2002. Towards a Model to Enhance Destination Competitiveness: A Southern African Perspective. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 10(2):124-141. [ Links ]

IBRAHIM EEB & GILL J. 2005. A positioning strategy for a tourist destination, based on analysis of customer's perceptions and satisfactions. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 23(2):172-188. [Internet: http://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/id/eprint/4524. Downloaded on 2013-01-28] [ Links ]

IPARA H. 2001. Towards cultural tourism development around the Kakamega Forest Reserve in Western Kenya. In Akama & Sterry 2001. Cultural tourism in Africa: strategies for the new millennium. Proceedings of the ATLAS Africa International Conference. Mombasa, Kenya [ Links ]

LUBBE BA. 2003. Tourism Management in Southern Africa. Pretoria: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

MCKERCHER B & DU CROSS H. 2002. Cultural Tourism: The partnership between tourism and cultural heritage management. Binghamton: Haworth Hospitality. [ Links ]

MET see Namibia Ministry of Environment and Tourism [ Links ]

MTI see Namibia Ministry of Trade and Industry [ Links ]

NACSO see Namibia Association of CBNRM Support Organisation [ Links ]

NAMIBIA ASSOCIATION OF CBNRM SUPPORT ORGANISATION. 2004. Namibia's communal conservancies: a review of progress and challenges. Namibia Association of CBNRM Support Organisation. Windhoek: NACSO. [ Links ]

NAMIBIA ASSOCIATION OF CBNRM SUPPORT ORGANISATION. 2010. Namibia's communal conservancies: a review of progress and challenges in 2009. Namibia Association of CBNRM Support Organisation. Windhoek: NACSO. [ Links ]

NAMIBIA MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND TOURISM. 2009. Tourist Statistical Report. Windhoek: Directorate of Tourism. [ Links ]

NAMIBIA MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND TOURISM. 2010. Tourist Statistical Report. Windhoek: Directorate of Tourism. [ Links ]

NAMIBIA MINISTRY OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY. 2008. Namibia Trade Directory. Windhoek: Meinert. [ Links ]

NAMIBIA TOURISM BOARD. 2011. Media release On: NTB Celebrates 10 years of development and business excellence. [Internet: http://www.namibiatourism.com.na/uploadedFiles/NamibiaTourism/. Downloaded on 2013-01-28] [ Links ]

NDIVO MR, WAUDO NJ & WASWA F. 2012. Examining Kenya's tourist destinations' appeal: the perspectives of domestic tourism market. [Internet: http://omicsgroup.org/journals/2167-0269/2167-0269-1-103.pdf. Downloaded on 2013-01-28] [ Links ]

NTB see Namibia Tourism Board [ Links ]

PAGE SJ & CONNEL J. 2006. Tourism: a modern synthesis. 2nd ed. London: Thompson. [ Links ]

PEARCE LP. 2005. Tourist behavior: Themes and conceptual schemes. Ontario: Channel View. [ Links ]

RAMCHANDER P. 2004. General orientation of the study. [Internet: http://upetd.up.ac.za/thesis/available/etd-08262004130507/unrestricted/01chapter1.pdf. Downloaded on 2012-08-22] [ Links ]

REISINGER H, CRAVENS K & TELL N. 2003. Prioritizing performance measures within the balanced scorecard framework. Management International Review 43:429-438. [ Links ]

RICHARDS G. 2001(a). The development of cultural tourism in Europe. In Richards G. (ed) Cultural attractions and European tourism. Wallingford: CABI. [ Links ]

RICHARDS G. 2001(b). Satisfying the cultural tourist: challenges for the new millennium in Western Kenya. In Akama & Sterry 2002. Cultural tourism in Africa: strategies for the new millennium. Proceedings of the ATLAS Africa International Conference. Mombasa, Kenya [ Links ]

RICHARDS G. 2007. Cultural tourism: Global and local perspectives. New York: Hospitality Press. [ Links ]

RITCHIE JRB & CROUCH GI. 2003. The competitive destination: a sustainable tourism perspective. Wallingford: CABI. [ Links ]

SILLIGNAKIS EK. 2008. Rural tourism: an opportunity for sustainable development of rural areas. [Internet: www.sillignakis.com.; downloaded on 2012-09-21] [ Links ]

SLABBERT E & VIVIERS P. 2012. Push and pull factors of National parks in South Africa. Journal of Contempory Management (9):66-88. [Internet: http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/jcman/jcman_v9_a4.pd. Downloaded on 2013-01-28] [ Links ]

TIMOTHY JD. 2011. Cultural heritage and tourism: an introduction. Bristol: Channel View. [ Links ]

TKACZYNSKI A , HASTINGS K & BEAUMONT N. 2006. Factors influencing repositioning of a tourism destination. In Yunus Ali and Van Dessel M (eds.). ANZMAC 2006 Conference proceedings: advancing theory, maintaining relevance, 4-6 Dec 2006, Brisbane, Australia. Brisbane, Australia: School of Advertising, Marketing and Public Relations, Queensland University of Technology. [Internet: http://www.anzmac2006.qut.com/. Downloaded on 2013-01-28] [ Links ]

WEAVER D & LAWTON L. 2006. Tourism management . 3rd ed. Queensland: Wiley. [ Links ]

WIKIPEDIA. n.d. Resource based view. [Internet: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Resource-based_view. Downloaded on 2012-08-22] [ Links ]

WITT SF & SONG H. 2001. Forecasting future tourism flows. tourism. In: Lockwood A. & Medlik S. (eds.) Tourism and hospitality in the 21st Century. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

WOOD C. 1993. Package tourism and new tourism compared. Proceedings from the national conference on community, culture and tourism. July. Melbourne: Australia. [ Links ]