Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.10 no.1 Meyerton 2013

RESEARCH ARTICLES

An analysis of procurement best practices in the University of South Africa

W Dlamini; IM Ambe

Department of Business Management, UNISA

ABSTRACT

In modern economies, efficient procurement practices play a strategic role both in the private and public sectors. Amid the current recession, the application of procurement best practices turns out to be even more relevant. This is because procurement best practices ensure the reduction of wasteful activities, streamline operations and create value chains for sustainable competitive advantage. However, despite numerous commendations on the benefits associated with the adoption of the procurement best practices, most organisations still find the implementation and continuous sustainability a challenge. Hence, the purpose of this article was to determine the level at which the University of South Africa (UNISA) has progressed with the application of procurement best practices. A conceptual analytical approach was employed with the aid of a checklist. The article revealed that UNISA has progressed to a proactive stage with regard to the application of procurement best practices. The article further brought to light the challenges impeding the advancement to the best practices. Based on the findings, it was recommended that the senior management in UNISA should take conscious efforts of addressing the identified challenges in order to gain a competitive advantage.

Key phrases: best practices; procurement; public higher education institutions; University of South Africa

1 INTRODUCTION

Procurement is the largest expense accrual function in any organisation (Emiliani 2010:118). Thus it is worthwhile that organisations conduct their procurement according to the best practices to save costs, minimise waste and streamline operations in order to gain a competitive advantage (Comm & Mathaisel 2005:230). Traditionally, purchasing has been referred to as a non-strategic function, often subordinated to finance in the public or service sectors and therefore considered as a non-value adding task (Baily, Farmer, Crocker, Jessop, & Jones 2008:5). Burt, Petcavage and Pinkerton (2010:9) asserted that, even though purchasing was viewed as a non-strategic function, it was accountable for a vast portion of the cost that organisations incurred, and purchased material accounted for most quality problems experienced.

Over the years the procurement function slowly gained recognition as organisations realised that the reactive ways did not always give the organisation a competitive advantage in turbulent markets (Bernardes & Zsidisin 2008:209). Various researchers have examined the evolutionary models of procurement (Burt et al. 2010:6; Nelson, Moody & Stegner 2005:28; Reck & Long 1988:3). These researchers unequivocally agree with the notion that procurement transformation taps the full potential of yielding prospects for the organisation. However, despite numerous citations by procurement researchers on the benefits associated with the adoption of the procurement best practices most organisations still find implementation and continuous sustainability a challenge (Rudzki, Smock, Katzorke & Stewart 2006:4). Even the few organisations that have employed procurement best practices sometimes do not conserve the practice and thus the practice is not sustained (Nelson et al. 2005:8).

Therefore, the purpose of this article was to analyse the employment of procurement best practices in the University of South Africa. The article began by reviewing procurement best practices, mapping the evolution of purchasing management from being a tactical function to supply management. Then a brief disposition of procurement in public higher education (HE) institutions presented. Thereafter procurement best practices in UNISA was expounded, research methodology discussed and the analysis recapitulated.

2 REVIEW OF PROCUREMENT BEST PRACTICES

Kraljic (1983:109) proclaimed thirty years ago that purchasing should become supply management. Since then, various authors with diverse backgrounds have tried to work out the development path (Lysons & Farrington 2006:4; Van Weele, 2010:8). In the process different terminologies have been formulated by researchers from different countries such as Baily et al. (2008:5); Burt and Doyle (1993:5); Lysons and Farrington (2006:1); Monczka, Handfield, Guinipero, Patterson and Waters (2010:71); and Sanches-Rodriguez (2009:161).

Surprisingly, the terms purchasing, procurement and supply management are used interchangeably by some researchers (Monczka et al. 2010:11), while other authors make a distinction between the terms (Burt et al. 2010:6). Progressively, the change in the viewpoints of purchasing has introduced concepts of strategic sourcing and best practices, which encompass value for money, business process re-engineering, continuous improvement and efficiency (Hugo, Badenhorst-Weiss, Van Biljon & Van Rooyen 2006:52). To date the ambiguity of procurement jargon has not been resolved. Hence the brief description of terminology follows:

• Purchasing is the systemic process of acquiring supplier's goods and services within the organisation (involves learning the need, locating and selecting a supplier, negotiating price and other pertinent terms, and following up to ensure delivery) in order to provide the user with the right quantity at the right time (Monczka et al. 2010:10).

• Burt et al. (2010:6) defined procurement as a conciliator stage between purchasing and supply management, as a result of the growth and broader scope of purchasing. This article adopts Burt, Petcavage and Pinkerton's trend.

• Supply management is the identification, acquisition, access, positioning and management of resources and related capabilities that the organisation needs or potentially needs in the attainment of its strategic objectives (Stolle 2008:16).

• Hugo and Badenhorst-Weiss (2011:60) defined strategic sourcing as a process whereby commodities (material and services) and suppliers are analysed and relationships are formed and managed according to best practices and appropriate strategies in support of the long-term organisational goals.

• Supply chain management is concerned with the coordinated flow of funds, information, materials and services from origin through suppliers into and through the organisation and ultimately to the consumer, in such a manner that value added is maximised and cost is minimised (Baily et al. 2008:66).

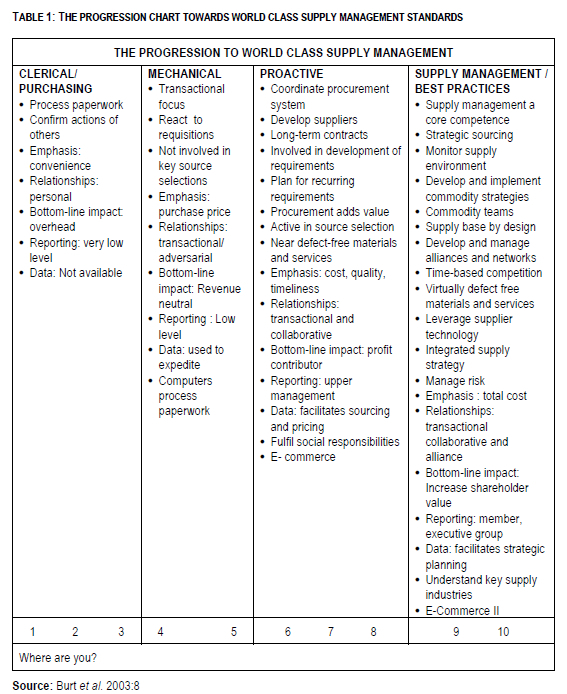

In this article, procurement best practices is described as a supply management philosophy that encompass a set of well established, common practices employed by leading organisations when conducting their procurement. The aim is to consistently and continuously improve spend and supplier base optimisation, thereby increasing return on investment and sustaining the bottom line and growth in the long term. Table 1 shows the progression towards world class supply standards through the application of procurement best practices.

As indicated in Table 1, for organisations to be competitive and sustainable in the long term, they need to adopt procurement best practices (level 9 and 10 in the supply management framework).

3 PROCUREMENT BEST PRACTICES IN HIGHER EDUCATION (HE)

This section of the article presents a review of procurement practices in public HE institutions as well as in the University of South Africa.

3.1 Procurement practices in public HE institutions in South Africa

HE institutions in South Africa are regarded as autonomous institutions in terms of Department of Education White Paper 3 of July 1997 (Bailey, Cloete and Pillay (2011:28). The institutions have to comply with the principles of co-operative governance (Cloete & Bunting 2000:12). Since public institutions are substantially supported by public funds, they play a crucial role in the social and economical developmental needs of the country, through adhering to the legislative and policy structures (McCruden 2007:247). As a result, public HE institutions are indirectly inclined to conduct their purchasing according to the public procurement policies. Most of the acts and regulations of public procurement in South Africa are embedded in Constitution of 1996, section 217, to serves as a framework for the implementation of policies (Bolton 2010:102).

Some of the legislative structures that guide the procurement policies of public HE institutions are the Public Finance Management Act 1 of 1999 (PFMA); the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act 5 of 2000 (PPPFA); the General Procurement Guidelines; the Policy to Guide Uniformity in Procurement Reform Processes in Government; the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act 53 of 2003 (BBBEEA); the National Small Business Act 102 of 1996; Codes of Good Practice as published on 9 February 2007; the Promotion of Access to Information Act 2 of 2000; the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act 12 of 2004); and the Insolvency Act no. 8 of 1936, as amended and the Confidentiality Procurement Process.

According to Arrowsmith and Kunzlik (2009:9) public procurement is "the process whereby government bodies purchase from the market the goods, works and services that they need". In this sector, large amounts are spent on goods and services because of its gigantic size (Baily et al. 2008:58). Hence, HE institutions as the custodian of knowledge need to engage in procurement best practices for proper management of public funds. By so doing, public HE institutions contribute to the improvement of social and economic sphere of a country's quality of life. According to Thornhill and Van Dijk (2010:95), theory and practice must complement each other in addressing values, culture, social and political issues. Also, Cousins, Lawson and Squire (2006:775) content that there is still a considerable gap between the vast theory of procurement best practices and its application. This gap is also prevalent in HE institutions and the gap may impede the progress towards the implementation of procurement best practices.

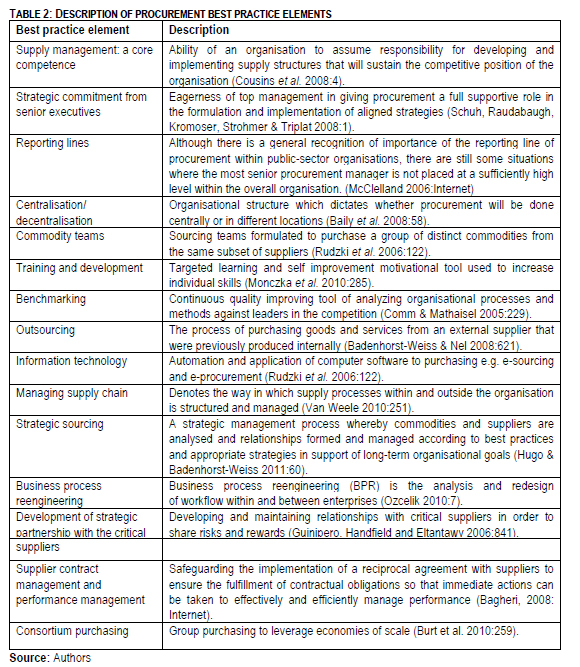

Furthermore, Comm and Mathaisel (2008:188) are of the opinion that, even though HE is regulated as public institutions, they could adopt procurement best practices similar to those of the private sector to gain competitive advantage. This means that HE institutions should equally esteem the significant value that the private sector management has adopted (Lenkowsky 2005: Internet). Based on the review presented above, Table 2 proposes procurement best practices that could be applicable to public HE institutions.

3.2 Procurement practices in the University of South Africa

UNISA is one of the mega comprehensive Open Distance Learning (ODL) institutions in South Africa. Procurement in this institution is entrenched in the Constitution of South Africa (Section 217 of 1996). The procurement policy of UNISA is built on the values of honesty, fairness, integrity, accomplished in a transparent, efficient and cost-effective manner (UNISA 2009:4). Responsibility centre managers are accountable for the prudent use of the university's resources in compliance with policies, procedures and applicable legislation. The first objective of UNISA is to promote the proficient supply of goods and services through the promotion and application of procurement best practices.

The procurement process is supported by the principle of a centralised organisational structure. All procurement of goods and services must be channeled through the Procurement Directorate by means of a duly authorised requisition form or a contract. This excludes purchases from occasional suppliers, which are channeled through the petty cash system. With reference to ethical standards and conflicts of interests; all procurement transactions and interactions with suppliers, including supplier selection and evaluation, are subject to the provisions outlined in UNISA's Code of Ethics and other Irregularities Policy (UNISA 2009:5).

Declaration of interest is another principle used within the UNISA procurement system. With this principle, UNISA ensures that any person involved in the purchasing, public and closed tender or supplier evaluation process must complete and sign the applicable declaration of interest form. Suppliers or their employees may not in any way participate or influence the specifications or standards set for goods and services to be purchased. Furthermore, confidentiality and accuracy of information are incorporated to ensure that the procurement process is respected by all stakeholders. Specific details of suppliers' bids must not be divulged, unless it is in accordance with the Promotion of Access to Information Act 2 of 2000, and then only through the Department of Legal Services (UNISA 2009:5).

All members of the Procurement Directorate and all committee members serving on procurement-related committees or attending procurement-related meetings must sign the confidentiality procurement process form. UNISA employees may not accept any gift, hospitality or other inducement that may or be seen to influence them in their decision-making responsibilities (UNISA 2009:5).

4 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND ANALYSIS

The article was based on a case study, particularly within the Procurement Department of UNISA. The university was chosen because it is one of the mega comprehensive ODL institutions found in South Africa. Therefore it encompasses elements that prevail in all three types of universities in South Africa (traditional, technologically oriented and vocationally oriented). The article was conducted in order to examine procurement best practices in UNISA. Universities are the hub of research and learning that impart knowledge and new skills to communities, industries and government sectors. It is therefore sensible to analyse whether UNISA manages its procurement according to best practices.

Existing literature was used as a baseline for extracting procurement best practices and factors presumed to be directly related to world class standards that influence universities and specifically UNISA. A checklist was formulated and the procurement policy of UNISA was used as a foundation to examine UNISA's procurement activities. Then the results of the analysis were used to determine the level to which UNISA has progressed with the application of the world class practices as outlined in Table 1.

5 ANALYSIS OF PROCUREMENT BEST PRACTICES IN UNISA

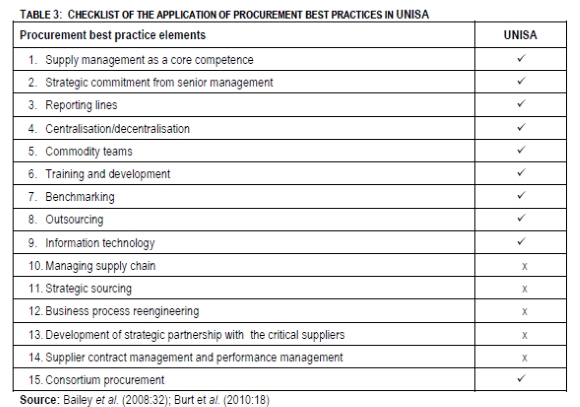

In this section of the article, procurement practices in UNISA were analysed based on the procurement best practices developed from literature (Table 2). The procurement best practices were used to determine the level at which the university has progressed with regards to the application of procurement best practices. It is important to note that UNISA's procurement practices are governed by its procurement policy. Handfield, Monczka, Giunipero and Patterson (2009:87) defined policy as the senior management directive's set of purposes, principles and rules of action that guide an organisation. It is for this reason that UNISA's policy was exploited. Based on the evaluation of UNISA's procurement policy in relation to the procurement best practices identified in Table 2). Table 3 presents the checklist of the application of procurement best practices in UNISA.

Table 3 highlights that out of 15 procurement best practices elements presented in the checklist; UNISA has adopted 10 of the best practices. The fifteen elements presented in Table 3 are analysed below:

1. Supply management as a core competence: Supply management can be a powerful competitive weapon, if the organisations adopt it as a core competency. Yet research suggests that the necessary alignment is often lacking (Monczka & Petersen 2012:Internet). However, in the recent years, the university has seen major strategic transformations in the management of the Procurement Department, such as the strategic commitment of senior management, changing of the reporting lines of the Procurement Department from the finance department to the Pro Vice-Chancellor and the use of iProcurement.

2. Strategic commitment from senior executive: Handfield et al. (2009:89) stress that the policy alone, no matter how concise and precise it may be, will not be influential in urging organisations to develop towards the strategic level if there is no senior management commitment. Therefore, the issue is critical in UNISA because senior management is involved in the procurement charter as it was established as the first objective of the UNISA procurement policy (UNISA 2009:4). The notion serves as a good basis because procurement policies convey a worthy value in directing principles and procedures of applications towards world-class standards.

3. Reporting lines: The Procurement Department was subordinate to the Finance department at UNISA and therefore procurement could not contribute effectively at strategic level. Consequently decision making on procurement best practices was hindered until recently when the reporting lines changed. At this present moment the Procurement Department reports to the Pro Vice-Chancellor, which places procurement at the highest strategic position. In so doing, procurement's contribution to the overall goals of the university is strengthened.

4. Centralisation/decentralisation: UNISA's procurement policy states that the UNISA's structure is centralised, and the procurement function is responsible for 90% of expenditure by the university. This is a positive factor for fostering procurement best practices (Stolle 2008:5). Though procurement may be conducted by regions and departments, payment of invoices is effected on the main campus. In addition, purchases from occasional suppliers are channeled through the petty cash system. Therefore, a hybrid of centralised and decentralised is noticeable as not all procurement spend are effected from the procurement department.

5. Commodity teams: Proactive organisations employ commodity teams to make strategic decisions concerning suppliers. The teams comprise of expertise from different functional areas, such as among others, finance, marketing and quality assurance. The use of these teams creates synergy within the organisation and also with the external partners. Boateng (2010:Internet) indicates that the practice has not been adopted in the whole African continent. In UNISA the tender committee is made out of different specialist who establishes the collaborative culture.

6. Training and development: Procurement staff at UNISA receives general training. To be employed in the UNISA procurement department; senior management positions require a professional formal qualification and sound experience while junior staff members are required to have completed a minimum qualification of at least Matric and or a certificate programme in procurement. UNISA subsidises studies for all its employees and offer internships, which is a commendable effort of promoting the employment of procurement best practices.

7. Benchmarking: Benchmarking is extensively used as a continuous quality improvement tool (Comm & Mathaisel 2005:229). Although UNISA continually strives to benchmark with other organisations that have advanced with the application of procurement best practices, the impact seems to be minimal because UNISA still lags with the application of procurement best practices. The expectation is high as the university has access to the recent trends and practices since research is conducted within the university and tuition is offered on the subject (Purchasing and supply chain management).

8. Outsourcing: Outsourcing provides low cost but flexible services to the organisation (Lau 2007:20). The non-core functions in UNISA are outsourced, such as cleaning, safety, garden and external auditing; which translate to time and cost saving.

9. Information technology: UNISA uses technology such as the Oracle system, email and internet for faster and cheaper access to information. However, more technological advancements can be effected to improve efficiency by adopting automated systems such as P-Cards, reverse auctions and Procure-to-Pay processes.

10. Managing supply chain: Hugo et al. (2011:4) affirm that supply chain management encompasses integration and coordination. In this aspect UNISA could also do more. The procurement department display little integration of processes and operations with the academic departments, other departments within the university and the partnership with the suppliers. According to Comm and Mathaisel (2008:187), the supply chains of many HE institutions are also looking after their own interests and disregard the overall efficiency of the total supply chain which could lower costs.

11. Strategic sourcing: This is a strategic management process whereby commodities and suppliers are analysed and relationships formed and managed according to best practices and appropriate strategies in support of long-term organisational goals (Hugo et al. 2011:60). By using strategic sourcing, UNISA could become a competitive differentiator through employing a multistage process to understand supply markets, determine internal needs, identify qualified suppliers, structure the right type of relationship and negotiate and implement the right procurement strategy.

12. Business Process Re-engineering (BPR): During the 1990's business process re-engineering became a useful tool for restructuring processes in organisations. The plan was to eliminate waste, lower costs and increase quality of service and that information technology was the key enabler for the radical change. The tenet was that technology, people and organisational goals were not suitable. The principles favoured streamlining operations, but the tool soon faded because it lacked sustained management commitment and leadership, unrealistic scope, expectations and was met with resistance to change (Ozcelik 2010:7). Management soon replaced it with enterprise resource planning (ERP), value stream mapping and lean practices. However, UNISA still needs to look at the processes and devise mechanisms of streamlining operations in order to reduce costs.

13. Development of strategic partnership with the critical suppliers: Despite the fact that organisations are encouraged to develop long-term partnerships with suppliers and maintain relationships with critical suppliers in order to share risks and rewards, Guinipero, Handfield and Eltantawy (2006:824) warn that there are instances that require transactional relationships. However, in UNISA strategic relationships are not prevalent and mostly arm's length and collaborative relationships are visible, followed by leveraging of contracts.

14. Supplier contract management and performance management: Procurement contract management involves making sure that all the terms and conditions of the contract are adhered to by both parties (Monczka, Handfield, Guinipero and Patterson 2009:329). While, performance management refers to making sure that the performance of the supplier is constantly measured in terms of effectiveness and efficiency in order to motivate the suppliers to continuously exceed expectations (Handfield et al. 2009:708). On analysing UNISA policy, this aspect was not evident. Authorities need to take initiatives to fully apply this compliance driver.

15. Consortium purchasing: Comm and Mathaisel (2008:186) emphasised that HE institutions can leverage economies of quantity against price by collaborating purchases. UNISA is affiliated with the Purchasing University Consortium (PURCO) and effects significant savings through group procurement.

After examining the application of procurement best practices in UNISA, it became apparent that procurement policy and procedures are available and known by the procurement personnel and the whole staff complement of UNISA as they are published on the university's website. Yet, as literature acknowledges, most organisations have not fully grasped the application of procurement best practices. Even though the literature presented earlier affirms that the employment of procurement best practices ensures the reduction of wasteful activities, streamlines operations and creates value chains for sustainable competitive advantage (Nelson et al. 2005:12). UNISA's case is no exception. Therefore, UNISA's procurement practices can be classified to be in the proactive stage on the progression of world class of the supply management standards (refer to Table 1). Based on the analysis presented above, the following issues were considered to be the challenges in the application of procurement best practices in UNISA. These challenges include:

• There is a shortfall of expectations directed to the Procurement Department, which leads to lack of understanding of the benefits of the application of procurement best practices;

• Alignment between organisational, financial and procurement objectives is unclear;

• Link between private and public procurement policies and practices is thin;

• Incorporation of the most influential procurement best practices elements in the policy is to some degree limited ; and

• Technological advancement in procurement systems have just been upgraded to reap rewards but utilised comprehensively.

6 CONCLUSION

The purpose of this article was to analyse the employment of procurement best practices in UNISA. Based on a theoretical analytical approach, the article reviewed procurement best practices; procurement practices within public HE institutions as well as in UNISA. In doing this, the issues surrounding the development of terminologies of purchasing to procurement and eventually to supply management were untangled. Also, a checklist of procurement best practices was formulated from the existing literature upon which UNISA procurement practices was evaluated.

The article contends that UNISA faces challenges with respect to the adoption of procurement best practices toward world class supply management standards. The challenges includes: the university procurement focuses more on transactional relationships; it is still reactive to requisitions notwithstanding the knowledge and availability of the procurement best practices; the value system needs improvement towards total cost of ownership; shared vision; more emphasis should be placed on value for money rather than purchase price. Despite the challenges, there is a strong strategic commitment from senior management; ongoing training and development of personnel; as well as leverage on consortium procurement. Based on the analysis presented above, the university procurement practices can be said to have evolved to a proactive stage (level 3) of the supply management levels (Table 1).

This article is in agreement with the view that most organisations have not fully understood the opportunities offered by the adoption of procurement best practices (Rudzki et al. 2006:4). Therefore senior management of UNISA involved in the procurement decision-making process are encouraged to enhance the employment of procurement best practices in UNISA. The enhancement of procurement best practices may contribute significantly to the university's competitive advantage. Therefore, the university should strive to address the identified challenges in order to implement procurement best practices effectively and efficiently.

REFERENCES

ARROWSMITH S & KUNZLIK P. 2009. Public procurement and horizontal policies in EC law: general principles. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

BADENHORST-WEISS JA & NEL JD. 2008. Outsourcing practices by the government sector in South Africa: a preliminary study. 3rd International Public Procurement Conference Proceedings, South Africa: 619-635. [ Links ]

BAGHERI N. 2008. Supplier performance management: how to start, measure & deliver. [Internet: http://www.supplyexcellence.com/blog/2008/07/22/supplier-performance-management-best-practices/#more-597 (downloaded on 2008-01-11. [ Links ]]

BAILEY T, CLOETE N & PILLAY P. 2011. Higher education institutions and economic development in Africa. Case study: South Africa and Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. [Internet: http://www.chet.org.za/files/uploads/reports/Case%20Study%20-%20SA%20and%20Nelson%20Mandela%20Metropolitan%20University.pdf; downloaded on 2012-05-24. [ Links ]]

BAILY P, FARMER D, CROCKER B, JESSOP D & JONES D. 2008. Procurement principles and management. London, Prentice Hall: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

BERNARDES ES & ZSIDISIN GA. 2008. An examination of strategic supply management benefits and performance implications. Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management. 14: 209-19. [ Links ]

BOATENG D. 2010. Government can buy more with less through strategic sourcing. [Internet: http://www.modernghana.com/news/296423/1/government-can-buy-more-with-less-through-strategi.html; downloaded on 2012-09-22. [ Links ]]

BOLTON P. 2010. The regulation of preferential procurement in state-owned enterprises. Journal of South African Law, 1: 101 - 118. [ Links ]

BURT DN, DOBLER DW & STARLING SL. 2003. World class supply management: the key to supply chain management. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

BURT DN & DOYLE MF. 1993. The American Keiretsu: a strategic weapon for global competitiveness. Irwin, Homewood, IL: Business One. [ Links ]

BURT D, PETCAVAGE S & PINKERTON R. 2010. Supply management. New York: McGraw-Hill/ Irwin. [ Links ]

CLOETE N, BAILEY T, PILLAY P, BUNTING I & MAASSEN P. 2011. Universities and economic development in Africa. Pretoria: Centre for Higher Education Transformation (CHET). [ Links ]

CLOETE N & BUNTING I. 2000. Higher education transformation: assessing performance in South Africa. Pretoria: Centre for Higher Education Transformation (CHET). [ Links ]

COMM CL & MATHAISEL DFX. 2005. An exploratory study of best lean sustainability practices in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education 13 (3): 227-240. [ Links ]

COMM CL & MATHAISEL DFX. 2008. Sustaining higher education using Wal-Mart's best supply chain management practices. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9(2): 183-189. [ Links ]

COUSINS P, LAMMING R, LAWSON B & SQUIRE B. 2008. Strategic Supply Management: principles, theories and practice. Harlow, England: Pearson. [ Links ]

COUSINS PD, LAWSON B & SQUIRE, B. 2006. An empirical taxonomy of purchasing functions. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 26(7): 775-794. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION. 1997. Education White Paper 3: A programme for the transformation of higher education. General Notice 1196 of 1997. Pretoria: Government Gazette. [ Links ]

ELLRAM LM & BIROU LM. 1995. Purchasing for bottom line impact: Improving the organization through strategic procurement. Chicago: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [ Links ]

EMILIANI ML. 2010. Historical lessons in purchasing and supplier relationship management. Journal of Management History. 16(1): 116-136. [ Links ]

GIUNIPERO L, HANDFIELD RB & ELTANTAWY R. 2006. Supply management evolution: key skill sets for the supply manager of the future. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 26(7): 822-844. [ Links ]

HANDFIELD R, MONCZKA R, GIUNIPERO LC & PATTERSON JL. 2009. Sourcing and supply chain management. 4th edition. Ontario, Canada: South-Western Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

HUGO WMJ & BADENHORST-WEISS. 2011. Supply chain management: logistics in perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

HUGO WMJ, BADENHORST-WEISS JA, VAN BILJON EHB & VAN ROOYEN DC. 2006. Purchasing and supply management. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

KRALJIC P. 1983. Purchasing must become supply management. Harvard Bus Review 61 (5): 109-117. [ Links ]

LAU AKW. 2007. Educational supply chain management: a case study. Emerald Group Publ 15(1): 15-27. [ Links ]

LENKOWSKY L. 2005. Drucker's contributions to non-profit management. [Internet: http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2005-11-17/druckers-contributions-to-nonprofit-management; downloaded on 2012-09-25. [ Links ]]

LYSONS K & FARRINGTON B. 2006. Purchasing and supply chain management. Harlow: Pearson. [ Links ]

MCCLELLAND JF. 2006. Review of public procurement in Scotland - report and recommendations. [Internet:www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2006/03/14105448/6; downloaded on 2012-04-23. [ Links ]]

MCCRUDEN C. 2007. Buying social justice: equality, government procurement, and legal change. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

MONCZKA RM, HANDFIELD RB, GUINIPERO LC & PATTERSON JL. 2009. Purchasing and supply chain management. New York: South-Western Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

MONCZKA RM, HANDFIELD RB, GUINIPERO LC, PATTERSON JL & WATERS D. 2010. Purchasing and supply chain management. New York: South-Western Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

MONCZKA RM. & PETERSEN KJ. 2012. The competitive potential of supply management. [Internet: http://www.scmr.com/images/site/SCMR_%20MayJun_2012_The_Competitive_Potential_Supply_Management_k502.pdf; downloaded on 2013-04-23. [ Links ]]

NELSON D, MOODY P & STEGNER JR. 2005. The incredible payback: Innovative sourcing solutions that deliver extraordinary results. AMACOM. New York: American Management Association. [ Links ]

OZCELIK Y. 2010. Do businessprocessreengineering projects payoff? Evidence from the United States. International Journal of Project Management, 28(1): 7-13. [ Links ]

RECK RF & LONG BG. 1988. Purchasing: a competitive weapon. Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management. 24(3): 2-8. [ Links ]

RUDZKI RA, SMOCK DA, KATZORKE M & STEWART S. 2006. Straight to the bottom line: an executive's roadmap to world class supply management. Florida: J. Ross. [ Links ]

THORNHILL C & VAN DIJK G. 2010. Public administration theory: justification for conceptualisation. Journal of Public Administration 45(1.1): 95-110. [ Links ]

SANCHEZ-RODRIGUEZ C. 2009. Effects of strategic purchasing on supplier development and performance: a structural model. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 24(3/4): 161-172. [ Links ]

SCHUH C, RAUDABAUGH JL, KROMOSER R, STROHMER MF & TRIPLAT A. 2012. The purchasing chessboard: 64 methods to reduce costs and increase value with suppliers. New York: Springer Science Business Media, LLC. [ Links ]

STOLLE MA. 2008. From purchasing to supply management: a study of the benefits and critical factors of evolution to best practice. Germany: Gabler Edition Wissenschaf. [ Links ]

UNISA. 2009. UNISA procurement policy. [internet: http://www.unisa.ac.za/contents/tenders/docs/ProcurementPolicy_editedforCorpManual_06Jul09.pdf] [ Links ]

VAN WEELE AJ. 2010. Purchasing and supply chain management. (5th edition). Hampshire, UK: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]